Richard Conniff's Blog, page 17

August 31, 2016

Sorry, Wildlife Farming Isn’t Going to End the Poaching Crisis

Asian civet at a wildlife farm in Bali (Photo: Paula Bronstein /Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Yale Environment 360

More than a decade ago, looking to slow the decimation of wildlife populations for the bushmeat trade, researchers in West Africa sought to establish an alternative protein supply. Brush-tailed porcupine was one of the most popular and high-priced meats, in rural and urban areas alike. Why not farm it? It turned out that the porcupines are generally solitary, and when put together, they tended to fight and didn’t have sex. In any case, moms produce only one offspring per birth, hardly a recipe for commercial success.

Wildlife farming is like that — a tantalizing idea that is always fraught with challenges and often seriously flawed. And yet it is also growing both as a marketplace reality and in its appeal to a broad array of legitimate stakeholders as a potentially sustainable alternative to the helter-skelter exploitation of wild resources everywhere.

Food security consultants are promoting wildlife farming as a way to boost rural incomes and supply protein to a hungry world. So are public health experts who view properly managed captive breeding as a way to prevent emerging diseases in wildlife from spilling over into the human population. Even Sea World has gotten into the act, promoting captive breeding through its Rising Tide nonprofit as a way to reduce the devastating harvest of fish from coral reefs for the aquarium hobbyist trade.

Conservationists have increasingly joined the debate over wildlife farming, with a view to … read the full story here.

August 26, 2016

The War on Rhinos? It’s an Investment Bubble

Carved rhino horn offered at a 2011 Christie’s auction in Hong Kong (Photo: Xinhua/Song Zhenping)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

Since the start of the current war on rhinos, in 2006, journalists and wildlife trafficking experts alike have treated the trade as a product of Asia’s new-found wealth combined with old-style traditional medicine: Rich buyers pay astounding sums for rhino horn in the belief that it will cure cancer or a host of other ills.

This reporting often comes with an undertone of bafflement or even thinly veiled condescension. Buyers, mainly in China and Vietnam, appear to be so naive that they ignore the total absence of scientific support for the medicinal value of rhino horn and put their faith instead in a substance that is the biochemical equivalent of a fingernail.

But a new paper in the journal Biological Conservation raises a startling alternative theory. Rhinos are dying by the hundreds for what may be in essence

an investment bubble, like tulips in 17th-century Holland or real estate in 1920s Florida.

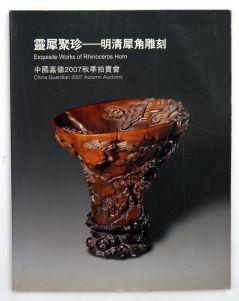

A 2007 rhino horn auction catalogue

It’s part of a trend over the past decade in China, according to Yufang Gao and his coauthors, of treating art and antiquities as a place for investors “to store value, to hedge inflation, and to diversify portfolio allocation.” Rhino horn assets typically take the form of cups, bowls, hairpins, thumb rings, and other ornamental items.

“Rhino horn pieces are portrayed in the Chinese media,” Gao and his coauthors write, “as an excellent investment opportunity whose value is tied more to the rarity of the raw materials rather than the artistic nature of the item. The aggressive media attention has played a significant role in the growth of the art market.” Press reporting about outlier items—those sold for astronomically high prices—“drives the perception that collecting rhino horn is highly profitable and influences black market prices.”

The study looks at articles from more than 300 Chinese newspapers between 2000 and 2014 and reveals that 75 percent focus on investment and collectible value versus just 29 percent focused on medicinal uses. It’s the opposite in the Western press, where the focus is on medicinal uses 84 percent of the time. Gao attributed this gap mainly to the language barrier and the tendency among Western journalists and conservationists to make little use of Chinese newspaper reporting. Chinese reporters also tend not to contribute to the international press.

The study hints that the rhino horn bubble has at least stopped expanding: Chinese press reporting on the investment value of rhino horn peaked in 2011. The following year, China’s government, under pressure from international governments, ended public auctions of rhino horn, ivory, and some other wildlife products. Press reporting on rhino horn collectibles plummeted, and the trade relocated to the internet and the black market. The price increase in rhino horn since then, when adjusted for the inflation rate in China, has not made it a particularly good investment even in purely financial terms, said Gao in an interview.

The killing of rhinos in South Africa, where most of the poaching occurs, declined slightly last year, for the first time in eight years. But the bubble has not burst: “We have been informed by various sources,” Gao and his coauthors write, “that the rhino horn market is ‘You Jia Wu Shi,’ which literally means ‘the price remains high but there is no turnover.’ Collectors, investors, and speculators are holding onto their collections, refusing to sell at a low price and waiting for the policy to change.”

They have some faint reason to hope. Earlier this year South Africa ended its ban on the rhino horn trade within its own borders, and Swaziland, a landlocked nation abutting South Africa, proposed to end the international ban on the rhino horn trade. The debate on that proposal will take place next month when the 180-odd member nations of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species meet in Johannesburg. Most observers say, however, that the proposal has almost no chance of winning approval.

Gao, born in Fujian province and now a doctoral student at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, urged rhino conservationists to pay attention to the investment and collectibles market. Investment involves “a very different group of stakeholders—museums, art galleries, art dealers, and collectors,” he said. “They have not been involved in the campaign” against poaching, and the same articles that tout the investment value of rhino horn never talk about the environmental consequences of the trade. “Conservationists should try to target these people and involve them in saving the rhinos,” he said.

One sure way to reach them: Demonstrate, with the support of the Chinese government, that the air is belatedly seeping out of this investment bubble, just as it did for tulips in 17th-century Holland and real estate in 1920s Florida.

Rhino horn “is really not a good investment,” said Gao.

August 21, 2016

Animal Music Monday: “Wondering Where the Lions Are”

Given the rapid disappearance of lions from entire regions of Africa, this song seems appropriate, though mostly for its title.

Singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn has said he was inspired by reading Charles Williams’s fantasy novel The Place of the Lion, which I suspect is about lions the way C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is about lions, and in that one the Aslan the lion is Jesus Christ’s avatar.

Anyway, here’s a stanza from Cockburn’s song:

I had another dream about lions at the door

They weren’t half as frightening as they were before

But I’m thinking about eternity

Some kind of ecstasy got a hold on me.

So I’m thinking Cockburn got high and wrote this because he was feeling fine. Fair enough. And I hope your dreams about lions at the door are also sweet ones.

August 19, 2016

China Drops the Hammer on Tortoise Smugglers

A radiated tortoise in Madagascar (Photo: Insights/Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

Get caught smuggling illegal wildlife in most countries in the world, and you can expect a slap on the wrist. A very gentle slap at that. “Somebody could take an AK-47 and just shoot up a pod of pilot whales,” one frustrated investigator recently complained. “That’s the same as a traffic offense.” It’s why wildlife crime has become a $10 billion-a-year industry: It’s safer than robbing the bank. It’s more lucrative than selling drugs.

So it should be big news that China, the leading market for wildlife trafficking worldwide, has just handed out jail sentences ranging from 21 months to 11 years to seven defendants caught smuggling hundreds of Madagascar’s critically endangered radiated tortoises. “This sentencing sends a strong message to illegal wildlife dealers that the punishment for these activities will fit the severity of the crime,” said Brian D. Horne, a Wildlife Conservation Society herpetologist who provided expertise to the prosecution.

The sentencing is the result of an investigation that began with the 2015 arrest of an airport security worker at Guangzhou Baiyun Airport toting two backpacks containing 316 juvenile tortoises. The animals had come in on a flight from Madagascar, as part of the baggage of Chinese immigrant workers there. The animals were wrapped in tinfoil, a precaution to avoid x-ray detection during transit via commercial airlines.

The airport worker, who had access to the baggage area, agreed to cooperate with investigators, leading to the dismantling of the criminal ring. Investigators also seized a second shipment containing another 160 radiated tortoises. The plan was to deliver the animals to an apartment in Guangzhou being used as a breeding facility, in an attempt to produce tortoises in captivity for the pet trade. The entire scheme was built, incidentally, on a faulty premise: While females can produce up to three egg clutches per year, of one to five eggs per clutch, they do not reach sexual maturity for 15 to 20 years, making commercial production impractical. So some of the animals were also being offered for sale via the internet.

Radiated tortoises are one of the most beautiful tortoise species in the world, noted for the yellow lines fanning out from the center of each of the plates on their domed shells. They can grow to 16 inches in length, and weigh up to 35 pounds, and they are also remarkably long-lived. One given to the King of Tonga, supposedly by Capt. James Cook in 1777, survived until 1965.

Radiated tortoises are one of the most beautiful tortoise species in the world, noted for the yellow lines fanning out from the center of each of the plates on their domed shells. They can grow to 16 inches in length, and weigh up to 35 pounds, and they are also remarkably long-lived. One given to the King of Tonga, supposedly by Capt. James Cook in 1777, survived until 1965.

Nobody knows how many of the tortoises survive in the wild, but they are endangered primarily by the rapid loss of habitat to slash-and-burn agriculture, livestock ranching, charcoal burning, and illegal logging. People also seek them for food and the lucrative pet trade, which is particular popular in southern China. You can also buy radiated tortoises in the United States, at prices around $3000 for a six-inch animal, and more than $6000 for an adult. They are ostensibly from captive-bred stock, though keeping them is forbidden by law in many states.

The hefty sentences handed out in the Guangzhou case, including an eleven-year jail term for the leader of the criminal ring, reflect an increasing effort by the Chinese government to treat wildlife crime more seriously. Lishu Li, China wildlife trade program manager for the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) said that over the past ten years she has observed a growing public awareness about the threat to wildlife. “The lifestyle is gradually changing. The education level is increasing. People in urban areas are watching nature documentaries. People are more willing to travel now. High level politicians in recent years have also put a lot of emphasis on what they call eco-stabilization.”

But demand for wildlife products remains high, and higher education and income level also means buyers tend to focus on more exotic, and often endangered, species. In the aftermath of news reports about sentencing in the radiated tortoise case, WCS made an informal survey and detected what Li said was a new note of panicky concern among sellers. But it will take many more such stiff jail sentences, handed out in case after case, to make the message stick.

The nearly 500 juvenile tortoise seized in this investigation went to a local rescue center. But returning them to their habitat in Madagascar is fraught with difficulties, including the danger of bringing back disease. “That’s why we want to stop the trade before it gets started,” said Li. “Once the tortoise is taken away from its native habitat, the misery story begins.”

END

Huge Tarantula Grabs Naked Danish Model

In the September issue of National Geographic, I write about how the fur industry has made a big comeback from the name-calling and blood-spattering of the 1990s. One way they’ve done it is by appealing to fashion designers, who tend to like things that are more sensational, even bizarre, than practical. This may be the weirdest: It’s a promo item I spotted in Denmark.

And in case you are wondering,no, that isn’t a real tarantula.

They don’t get that big, honest, and this one is made of mink.

A Toothy Answer to The Problem of Feral Pigs

August 15, 2016

How The Fur Trade Made Its Big Comeback

Models prepare to show fur coats and hats by Simonetta Ravizza.

by Richard Conniff/National Geographic

It was frozen-toe, mid-February, north-country cold, under a cloudless sky, sun glinting off fresh snow. We were tromping out onto a wetland frozen nine inches deep. It felt like how the fur trade began, someplace long ago, far away.

Bill Mackowski, in his 60th year of trapping, mostly around northern Maine, pointed out some alder branches sticking through the ice. Beavers start collecting poplar after the first cold snap, he explained, then pile on inedible alder to weigh down the poplar below the ice, where they eat it throughout the winter. He hacked through the ice with a metal pole, then passed it to me to try. “Feel how hard the bottom is on the run?” Beaten down by beaver traffic, he said.

Nailing the skin out to dry. (Photo: Richard Conniff)

Breaking through the ice in another spot, Mackowski said, “Did you hear those air bubbles?” He widened the hole and began hauling up until a peculiar steel device broke the murky surface. It was a trap, snapped tight around the neck of an enormous beaver. Those air bubbles, a moment locked in ice, were its final breath.

“That’s what we call a superblanket,” said Mackowski. “That’s a nice beaver.” The pelt would bring no more than $25, he calculated, but all the way home he wore the satisfaction of a thousand generations of successful hunters and trappers. Still glorying in the day and in his own deep reading of the landscape, he recalled what another winter visitor once told him: “If people could get past killing the beaver, they would pay to come out here like this.”

In truth, getting past the killing doesn’t seem like much of an issue anymore. Top models who once posed for ads with slogans like “We’d rather go naked than wear fur” have gone on to model fur. Fashion designers who were “afraid to touch it” 15 or 20 years ago have also “gotten past that taboo,” said Dan Mullen, a mink farmer in Nova Scotia. Many in the fur trade now readily acknowledge that activists who protested so loudly had a point: Farmers were not providing a decent standard of care for their animals. But they add that the trade has changed, though activists dispute this. In any case, many people now seem to regard wearing fur as a matter of individual choice. In some cities you are more likely to be glowered at for texting while walking.

Fur farms dominate the trade, and production has more than

doubled since the 1990s, to about a hundred million skins last year, mostly mink and some fox. Trappers typically add millions of wild beaver, coyote, raccoon, muskrat, and other skins. That’s besides untold millions of cattle, lambs, rabbits, ostriches, crocodiles, alligators, and caimans harvested for food as well as skins.

But you hardly need the numbers. Just look around. Once the resolutely conventional winter-fashion choice of Park Avenue matrons and country club partygoers, fur has gone hip-hop and Generation Z. It turns up now in all seasons and on throw pillows, purses, high heels, key chains, sweatshirts, scarves, furniture, and lampshades. There are camouflage-pattern fur coats, tie-dyed fur coats, and fur coats in an optical illusion M. C. Escher box pattern. There’s even a fur pom-pom that’s a Karl Lagerfeld Mini-Me, created by the designer in his own image and dubbed Karlito.

So how has fur made such a comeback from the intense social ostracism of the 1990s? Or for that matter, from the notoriety of the 1960s, when the cartoon character Cruella de Vil hankered after the fur of Dalmatian puppies, and the real-life trade was threatening the survival of leopards, ocelots, and other species in the wild? …. to read the full story in the September National Geographic, click here.

August 13, 2016

Christmas in August: Give to These Wildlife Groups Now

One cause worth your donation (Photo: Craig Taylor/Panthera)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

Most writers wait until the Christmas season to put together their recommendations for charitable giving. But the trouble with that timing ought to be obvious: In December, most people are broke or about to be broke. They’re also a little crazy. In August, on the other hand, life is fat and slow, and there’s time to think about our own lives and what we can do to make the world a better place. With that in mind, I’m going to offer a few recommendations for giving, with my usual focus on wildlife.

First, though, let’s talk about two candidates for this year’s charitable giving purgatory: The World Wildlife Fund is in many ways a great organization, but it has a long history of paying too much attention to marketing. That tendency showed up this year when a WWF vice president put out an announcement, widely reported in the press, that tiger populations were on the increase for the first time in a century. Too bad it was totally bogus. Sorry, but the folks at the top need to put wildlife conservation first and fund-raising somewhere down the list. Hoping to see you next year.

My other newcomer in purgatory is Ducks Unlimited. I’ve recommended it in the past for its single-minded focus on increasing populations of wildfowl. But, hey, save your money. Late last year, DU fired a staffer who had the nerve to take on a prominent donor. Media muckety-muck Jim Kennedy, chairman of Cox Enterprises, was trying to block public access to the Ruby River, which runs through his Montana ranch. But defending public access is one of the core beliefs at DU, and Don Thomas, a longtime contributor to Ducks Unlimited magazine, called out Kennedy for his hypocrisy. DU promptly fired Thomas while praising Kennedy as “a dedicated DU volunteer.”

Where should you send your money instead? Let’s start with

the Wildlife Conservation Society and Panthera, because these groups are led by scientists and have a strong focus on putting scientists and conservationists in the field.

WCS is the parent organization of the Bronx Zoo. Last month I published an article about the racist who founded the organization in the 19th century. But a lot of great organizations have racist pasts, and the next time I interviewed a WCS scientist after the article appeared, he volunteered that dealing openly with that history is the only way to move forward. WCS is anything but racist now. Its staffers come from all ethnicities and seem to be doing important work everywhere—whether it’s selling carbon credits to protect Cambodia’s Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctuary, developing new solutions for human-wildlife conflict in India, or raising the alarm about the sharp decline of white-naped cranes in eastern Mongolia, just to cite a few examples from the past month. (You can check out the Charity Navigator report on WCS here and donate to WCS here.)

Panthera, which focuses on cat conservation, joined with WCS scientists early this year in telling the discouraging truth about threatened tiger populations. Panthera also did most of the difficult legwork of documenting the rapid disappearance of lions across much of Africa. Instead of empty outrage about the shooting of Cecil in Zimbabwe, Panthera (together with WildAid) outlined practical steps for channeling that outrage into real progress for lions. Panthera still hasn’t turned up on Charity Navigator. (Come on, @charitynav!) But take my word for it: This organization is worthy of your donation.

So is the Environmental Defense Fund. OK, it’s not strictly concerned with wildlife. The thing about EDF is that it dares to think originally and excels at enlisting unexpected partners in the cause. It was EDF, for instance, that got President George H.W. Bush to back cap-and-trade as an immensely effective solution to the acid rain crisis in the 1990s. And just this June it played a key role in winning overwhelming bipartisan(!) support for a major reform of federal regulations on toxic substances. EDF is also the driving force behind Catch Shares, a rights-based initiative that seems to be saving fish stocks and fishing jobs at the same time. (Here’s Charity Navigator on EDF, and here’s where to donate.)

Finally, I like two smaller groups, the Environmental Investigation Agency and Defenders of Wildlife. EIA does long-term undercover investigations of illegal trafficking in wildlife, timber, and other products. One of those investigations culminated this year when Lumber Liquidators paid the largest fine ever under the Lacey Act for illegally harvesting timber from the last remaining habitat of the Siberian tiger. Also this year, EIA exposed an Austrian company for harvesting Europe’s last virgin forests, in Romania. You can donate to support future investigations here.

Defenders of Wildlife takes on wildlife issues that are often unpopular in the American West. Wolves in Idaho, for instance. Right now, it is defending the pallid sturgeon from extinction at the hands of a sugar beet boondoggle in Montana. As Defenders puts it on its donation page, “America’s wild animals are counting on you.”

That’s all I have room for right now. But here’s one other thought: The usual end-of-year focus on charitable giving implies that it is a once-a-year thing. It’s also often linked to the idea that if you give now, you will reap a potential tax benefit in April. But lump sum donations have a way of feeling painful or just a little too difficult to manage this month. Instead, divide your annual giving by 12, and have the donation automatically charged to your credit card every month.

You’ll sleep better, budget-wise, and also because you’ll be making a difference every day.

August 7, 2016

Animal Music Monday: Rock Lobster

I’m spending a little time in Maine, so this seems like a natural. Sort of unnaturally natural, that is. The most animal-oriented lyric goes off the deep end, literally:

Here comes a stingray

There goes a manta-ray

In walked a jelly fish

There goes a dog-fish

Chased by a cat-fish

In flew a sea robin

Watch out for that piranha

There goes a narwhal

Here comes a bikini whale!

The B-52s released the song in April 1978, and it became their biggest hit ever. And the infectious looney-toon silliness of the song inspired John Lennon to come out of retirement and back into the studio: On hearing it “I said to meself ‘It’s time to get out the old axe,'” Lennon said. The result was “Double Fantasy,” released a few weeks before he was murdered in December, 1980.

Sorry. Downer. Here’s the song:

August 5, 2016

A Miracle Drug Saves People But Buggers The Environment

Ivermectin is bad news for dung beetles. (Photo: George Grall/’National Geographic’/Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

See if you can spot the pattern here: Widespread reliance on the herbicide Roundup has pushed the monarch butterfly to the brink of extinction. Neonicotinoid pesticides stand accused of knocking down populations of honeybees and other pollinating insects. The veterinary drug diclofenac has killed off 99.9 percent of the vultures in India. Now it looks as though ivermectin, long hailed as a miracle drug, may be doing the same thing to dung beetles everywhere.

Yep, it’s definitely a pattern: Companies find some alleged wonder product and move it to market as quickly as possible, with a tight focus on profits and no regard (or responsibility) whatever for the inadvertent side effects.

The dung beetle story has gotten relatively little attention, perhaps because people have the idea that these funny little feces eaters exist only in Africa and only to help clear the landscape of gargantuan elephant droppings. There are 5,000 dung beetle species, and they do their humble work on every continent except Antarctica. And if you think dung beetles don’t matter pretty much everywhere, try imagining a world neck-deep in

cattle manure.

Let’s concede up front that as part of the human medical tool kit, ivermectin is one of the great miracle drugs of our time. It kills parasites and has thus saved hundreds of millions of people from the horribly devastating effects of both river blindness and elephantiasis. The scientists who developed the drug in the 1970s last year shared the Nobel Prize for their work.

Ivermectin is, however, also one of the world’s most popular veterinary drugs, for a host of parasitic afflictions. That’s a problem because livestock grazing eats up about a quarter of the world’s ice-free land, and the livestock excrete all but a fraction of the ivermectin intact back into the environment, where it continues its killing ways.

A study early this year linked ivermectin use to the decline of seven dung beetle species in Spain and Portugal. Now the journal Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry has put dung beetles on the cover and devoted the bulk of the magazine to the ivermectin problem.

The most important of the studies looks at ivermectin use in four countries and suggests ways to minimize those inadvertent side effects. “As expected, the overall number and diversity of dung beetles, dung flies, and parasitoid wasps decreased as the ivermectin concentration increased,” said coauthor Wolf Blanckenhorn, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Zurich.

Earthworms and springtails living in the ground underneath the cowpats appeared to be unaffected. These other species were sufficiently insulated from the ivermectin, or sufficiently resistant to it, to compensate for the loss of dung beetles, so the dung degraded more or less normally. Nature is like that. It has redundancies and backup systems, also known as biodiversity.

It’s worth noting that the previous study in Spain and Portugal was not nearly so sanguine. Those researchers reported that routine use of ivermectin in cattle not only impaired the dung beetles but also caused an extra 312 pounds of dung to accumulate per acre per year. That’s bad news even for cattle farmers, who cannot graze their cattle on fields smothered in dung. It’s bad news for the environment too. Stripping away backup systems is simply reckless, whether you are talking about nature or engineering. Sooner or later, everything goes kerflooey.

The study by Blanckenhorn and his coauthors field-tested a method for identifying the effects of ivermectin on a range of dung-eating species. The aim is to give government regulatory bodies—and progressive farmers—a tool to determine when it’s safe to use ivermectin and what minimal dose can treat the livestock without disrupting the natural environment. Now government agencies need to decide whether to require “this more conclusive yet more complex test,” said Blanckenhorn. Taking a census of the dung-eating population in a field could soon become easier because of DNA bar coding, which uses rudimentary genetic sequencing to quickly identify the species present in a sample.

Meanwhile, farmers might want to think twice about their dependence on ivermectin or the host of other drugs being pushed on them by heedless pharmaceutical companies. And the rest of us? We have one more reason to continue reducing the amount of meat in our diets.