Richard Conniff's Blog, page 15

November 23, 2016

As Coal Use Drops, So Does Mercury in Tuna. Will Trump Un-Do That?

(Photo: Yusuke Kawasaki/Flickr).

by Richard Conniff/Scientific American

Levels of highly toxic mercury contamination in Atlantic bluefin tuna are rapidly declining, according to a new study. That trend does not affect recommended limits on consumption of canned tuna, which comes mainly from other tuna species. Nor does it reflect trends in other ocean basins. But it does represent a major break in the long-standing, scary connection between tuna and mercury, a source of public concern since 1970, when a chemistry professor in New York City found excess levels of mercury in a can of tuna and spurred a nationwide recall. Tuna consumption continues to be the source of about 40 percent of the mercury contamination in the American diet. And mercury exposure from all sources remains an important issue, because it causes cognitive impairment in an estimated 300,000 to 600,000 babies born in this country each year.

The new study, published online on November 10 by Environmental Science & Technology, links the decline directly to reduced mercury emissions in North America. Most of that reduction has occurred because of the marketplace shift by power plants and industry away from coal, the major source of mercury emissions. Pollution control requirements imposed by the federal government have also cut mercury emissions.

Progress on both counts could, however, reverse, with President-elect Donald Trump promising

a comeback for the U.S. coal industry, in part by clearing away such regulations.

For the new study, a team of a half-dozen researchers analyzed tissue samples from nearly 1,300 Atlantic bluefin tuna taken by commercial fisheries, mostly in the Gulf of Maine, between 2004 and 2012. They found that levels of mercury concentration dropped by more than 2 percent per year, for a total decline of 19 percent over just nine years.

Although the researchers were aware of the decline in the amount of mercury entering the atmosphere over North America, it came as a surprise when this improvement also showed up in the flesh, says study co-author Nicholas Fisher, a marine biogeochemist at Stony Brook University. Atlantic bluefin tuna are big, fast-moving predators at the top of the food chain and live on average 15 to 30 years. Those traits make them perfectly suited to accumulating mercury and other environmental contaminants. “We could as easily have expected it to take a century” for the fish to show signs of recovery, Fisher remarks. The contrary finding “tells me we don’t just have to ring our hands about the high level of mercury in these fish. There is something we can do about it and get pretty quick results.”

The study is also surprising because mercury is long-lived in the environment, says Noelle Eckley Selin, an atmospheric chemist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who was not involved in the study. Whereas surface waters reflect recent changes in mercury emissions, past emissions from early in the industrial era can persist for centuries in the deep ocean.

The level of mercury contamination has also decreased in Atlantic coast bluefish, according to a 2015 study. But that assessment was based on less reliable data, and in a much shorter-lived species, observes Carl Lamborg, a biogeochemist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who was not involved in either study. The bluefin tuna finding “shows that even a fishery that we would have thought had a certain amount of chemical inertia can be cleaned up if you stop putting mercury into the system,” he says. Bluefin tuna is a highly prized fish, sold mostly in Japan, where a single fish went for $118,000 at auction early this year. Both Atlantic and Pacific varieties are listed as endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species.

The new study comes as worldwide mercury emissions continue to rise, particularly in the Pacific, source of much of the tuna and other seafood consumed in the U.S. That increase of about 3.8 percent per year results largely from increased reliance on coal-fired power plants in China, India and other Asian countries.

Despite President-elect Trump’s campaign pledge to revive the coal industry in this country, economic factors, including competition from inexpensive natural gas, make a U.S. coal comeback unlikely. Even U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who for eight years blamed the Obama administration for the demise of coal, began to walk back the idea that Republican control in Washington, D.C., would make much difference: “Whether that immediately brings business back is hard to tell,” he told a Kentucky audience on November 11, “because it’s a private sector activity.”

In any case, the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), a utility-funded nonprofit, projects that mercury emissions from U.S. power plants will be about 85 percent lower in 2017 than in 2010. Planned retirements of coal-fired power plants, combined with pollution control upgrades already installed to comply with Environmental Protection Agency regulations, will drive the expected decline. Those regulations face continuing legal challenges but “you can’t ‘un-pay’ for the controls you have already put in,” says Leonard Levin, an EPRI air quality analyst.

The larger concern, Selin notes, is Trump’s plan to abandon the Obama administration’s major climate change initiatives. These initiatives include the Clean Power Plan, which would set a gradually decreasing national limit on carbon pollution from electric utilities, and the recently signed 2016 Paris agreement, in which 193 nations committed themselves to individual limits on carbon pollution. The U.S. is also party to the Minamata Convention on Mercury, a treaty designed to reduce mercury emissions worldwide that is likely to go into effect in 2017. (The name comes from Minamata, Japan, site of one of the most horrifying environmental disasters of the 20th century, with severe birth defects and other disorders resulting from mercury contamination in seafood.)

“These issues are linked,” Selin says. “More coal burning gives you more carbon dioxide and more mercury, and these are things that connect very directly with people’s health in the United States. The future of mercury emissions really depends on energy sources in Asia,” and it requires “U.S. involvement to encourage” energy production from sources other than coal. Without that global shift away from coal, all the progress on mercury so far achieved in North America ultimately could be in vain.

November 22, 2016

Climate Change Killed This Little Guy. Can Relocation Save Other Species?

A cousin of the now-extinct Bramble Cay melomys. (Photo: Luke Leung/University of Queensland)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

Australian scientists were “devastated” in 2014 when they visited the tiny island home of the Bramble Cay melomys, the Great Barrier Reef’s only endemic mammal, and found no one home. They described it as probably “the first recorded mammalian extinction due to anthropogenic climate change.”

What really hurt was that they were visiting the island on a rescue mission, to find enough individuals for a captive breeding project. The ambition was to rebuild the population and reestablish it in some more hospitable habitat. They were too late: Repeated storm surges had wiped out the plant that was the major food source for the melomys, and the last few members of the species, the product of a million years of evolution, were probably swept out to sea and drowned.

That painful example has many conservationists thinking hard about what they call “assisted colonization.” That is, they are wondering whether and how to move species to places they have never lived before—because that may be their only chance

to survive the climate change regimen of warmer temperatures, rising seas, and extreme weather events like drought, flooding, and wildfire.

One of the first such assisted colonizations happened this past August, also in Australia, where a team of researchers loaded up their vehicles with captive-bred specimens of the critically endangered western swamp tortoise and drove them three hours south. Their old home near the city of Perth in Western Australia was rapidly drying out in the face of persistent drought. Researchers had to sort through 13,000 potential sites to find one that would still feel like a swamp in the drier climate 50 years from now—and where the newcomer wouldn’t displace existing species. It’s too soon to know whether that experiment will succeed—or even whether the remaining tortoises will go extinct in their old habitat.

Yet the pressure to think about such relocations before another melomys-style extinction is everywhere in conservation. A study this year predicted that about 30 percent of all terrestrial mammals will be unable to expand their range fast enough to keep pace with climate change. Even highly mobile species like birds and butterflies lag behind the pace of change. Housing, highways, and other human developments often aggravate this “migration lag” by breaking up potential migratory routes.

Assisted colonization is, however, a fiercely debated alternative, with critics describing such efforts as “planned invasions” and a game of “ecological roulette.” They fear that relocated species may cause extinctions or a host of other unintended consequences in their new habitat, as introduced species have often done.

Most conservationists share those concerns. They’ve spent much of their careers dealing with the consequences of species invasions. Their psychology has traditionally been geared to restoring habitats, not reinventing them. Imagining how habitats might look and where species can expect to survive in some unknown future is a terrifying endeavor.

Their answer so far has been to approach the idea cautiously, with guidelines and decision trees to help sort out the questions: What can I do to keep the species going for now, and what will it take in 30 years? At what point does it make sense to attempt a translocation? What do I need to know about the ecology of the species involved? What other species does it depend on, and are they also susceptible to movement? Since it will be impossible to save all the species threatened by climate change, how do we decide which species matter enough to us or to the environment for us to undertake the enormous effort translocation will entail?

“It’s really about value judgments, but value judgments are part of any decision,” said Tracy Rout, a research fellow at the University of Queensland and a creator of one recent algorithm for translocation decision making. “We need to say what’s important, what are the things we care about. You do that even if you’re just trying to decide whether to take an umbrella to work. You’re thinking about the weather, but also how big is my umbrella? How annoying is it to carry it around? Do I have an important meeting? Do I have to walk far? Am I going to be carrying my computer and not want it to get wet? Your values are there, and you need a framework to put them in perspective.”

Not so long ago, conservation biology was about trying to put together a jigsaw puzzle—a natural habitat with all its old diversity. That was hard enough, with some of the pieces not just missing but extinct. Now it’s as all of us have kicked the jigsaw puzzle into the sky, and the trick for biologists is to put it together again while it is not just airborne but caught in the shifting winds of climate change.

Also it’s starting to rain. So did you bring your umbrella? Or, wait, maybe it will never rain again. And here is a species you care about passionately. Maybe it’s some lizardy thing, or an insect, or even a snake, but you care as if it were a big-eyed puppy at the pound with no time left and nobody else to take it home. So here are the five things you could do to make the difference between survival and oblivion. Only one of them will save the day. It’s not an emotional decision, but time is running out: Choose.

November 11, 2016

What Trump’s Triumph Means for Wildlife

As a brown bear lunges for fish, a gray wolf waits for scraps in Alaska’s Katmai National Park. (Photo: Christopher Dodds/Barcroft Media/Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

For people who worry about the nation’s (and the world’s) rapidly dwindling wildlife, the only vaguely good news about Donald Trump’s election might just be that he doesn’t care. This is a guy whose ideas about nature stop at “water hazard” and “sand trap.” Look up his public statements about animals and wildlife on votesmart.com, and the answer that bounces back is “no matching public statements found.” It’s not one of those things he has promised to ban, deport, dismantle, or just plain “schlong.”

More good news (and you may sense that I am stretching here): Trump is not likely to appoint renegade rancher and grazing-fee deadbeat Cliven Bundy to head the Bureau of Land Management. When Field and Stream magazine asked Trump early this year if he endorsed the Western movement to transfer federal lands to state control (a plank in the Republican platform), he replied: “I don’t like the idea because I want to keep the lands great, and you don’t know what the state is going to do. I mean, are they going to sell if they get into a little bit of trouble? And I don’t think it’s something that should be sold.”

This was no doubt the real estate developer in him talking, but his gut instinct against letting go of land will surely outweigh the party platform. “We have to be great stewards of this land,” Trump added. “This is magnificent land.” Asked if he would continue the long downward trend in budgets for managing public lands, Trump said he’d heard from friends and family that public lands “are not maintained the way they were by any stretch of the imagination. And we’re going to get that changed; we’re going to reverse that.”

This was apparently enough, in the immediate aftermath of Trump’s upset election, for Jamie Rappaport Clark, president of the conservation group Defenders of Wildlife, to suggest that

“we share common interests in the protection of America’s wildlife and our great systems of public lands, which provide endless opportunities for outdoor recreation, wildlife observation, and other pursuits that all Americans value.”

Meanwhile, pretty much all others active on wildlife issues were looking as if the floor had just dropped out from under them, plunging them into a pool of frenzied, ravenous Republicans. At the website for the Humane Society, where a pre-election posting warned that a Trump presidency would pose “an immense and critical threat to animals,” an apologetic notice said, “The action alert you are attempting to access is no longer active.”

They have reason to be nervous. Trump has surrounded himself with political professionals who do not think sweet thoughts about wildlife. Newt Gingrich, for instance, loves animals—but mainly in zoos rather than in inconvenient places like the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Reince Priebus, a likely choice for chief of staff, was part of a Tea Party revolution in Wisconsin that put Gov. Scott Walker in power. Just to give you a sense of what that could mean for a Trump administration, Scott handed over control of state parks and other lands to the hook-and-bullet set while shutting out biologists and conservationists. Chris Christie? Rudy Giuliani? Let’s just not talk about them.

Trump’s main advisers on wildlife appear to be his sons, Donald Jr. and Eric, and they seem to care only about hunting and fishing. Donald Jr. has publicly expressed a wish to run the Department of the Interior, though his only known qualification for the job is his family name. More likely, as he told Outdoor Life during the campaign, he will help vet the nominees for Interior, “and I will be there to make sure the people who run the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and so on know how much sportsmen do for wildlife and conservation and that, for the sake of us all, they value the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation.”

Don Jr. and Eric with trophy leopard

You may be stumbling over that Christ-like phrase “for the sake of us all.” But you should really be worrying about the “North American Model.” It’s a code phrase for managing public lands primarily for hunting and fishing and only secondarily, if at all, for nongame species—or for hiking, bird-watching, camping, or other uses. In practice it can mean eradicating wolves because hunters consider them competition for elk or moose. (Donald Jr.: “We need to reduce wolves and rebuild those herds.”) It can mean cutting back funding for songbird habitat and spending it instead on fish stocking.

Like his father, Donald Jr. has opposed selling public lands, mostly because it “may cost sportsmen and women access to the lands.” But he believes states should help govern federal lands, calling shared governance “especially critical when we pursue our idea of energy independence in America. As has been proven in several of our Western States, energy exploration can be done without adverse affects [sic] on wildlife, fisheries or grazing.” (America has come tantalizingly close to energy independence under President Obama—without moving new drilling rigs onto public lands—and there is no evidence for the broad-brush notion that energy exploration is harmless to wildlife.)

Two other major considerations to keep in mind: If Trump goes ahead with his favorite plan to build a wall on the Mexican border, it would cut off vital migratory routes and habitat for jaguars, ocelots, desert bighorn sheep, black bears, and many other species. (It might also impede the flow of fed-up Mexicans heading south.)

Likewise, trashing the Paris Agreement on climate change, as Trump has promised to do, would gain the United States nothing and risk committing the planet irrevocably to warmer temperatures, extreme weather events, and massively destructive coastal flooding. That doesn’t make sense even from a business perspective, and much less so for wildlife. The first documented extinction of a species by human-caused climate change occurred this year, when the Bramble Cay melomys succumbed to rising sea levels in its South Pacific island home. Thousands of other species also face disruption of their habitat and the likelihood of imminent extinction.

The bottom line is that a Trump administration is likely to be good for mining, drilling, logging, and the hook-and-bullet set. But for wildlife and for Americans at large? We are facing four dangerous years of self-serving gut instinct and reckless indifference to science, with the damage to be measured, as climate activist Bill McKibben put it the other day, “in geologic time.”

If you are feeling as if a Trump victory is the end of the world as we know it, you may just be right.

November 5, 2016

Hundreds of Millions of Birds Have Gone Missing

All the earth & sky no longer loud with skylark’s voice. (Photo: Arterra/UIG via Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

You might think that what happened to the passenger pigeon couldn’t happen today. We know better than to allow a species with a population in the billions to dwindle away to nothing over the course of a few decades, don’t we?

Sadly, no. In fact, it’s not just one species this time. It’s an entire world of migratory songbirds—turtledoves, skylarks, cerulean warblers, wood thrushes, yellow-breasted buntings, and many more—on flyways touching every continent.

The sort of industrial-scale hunting that wiped out the passenger pigeons a century ago is once again part of the story: For instance, a study early this year estimated that hunters and trappers, mostly in the eastern Mediterranean, are illegally taking 11 million to 36 million birds each year for food, the pet trade, and sport. Likewise, hunting of entire flocks in China has caused a 90 percent decline in populations of yellow-breasted buntings, once common across Eurasia but now more easily found on the dinner plates of the nouveaux riches.

But while the scale of this needless killing is shocking, the bigger problem for migratory birds, according to a new analysis published in the journal Science, is

less sensational but even harder to address—“land-use changes and connected habitat degradation and loss.”

Franz Bairlein, director of the Institute of Avian Research in Wilhelmshaven, Germany, set out to write his analysis for Science, he said in an interview, when he realized that the headline-making study of killings did little to explain the steep migratory songbird declines in Western Europe. Those birds travel the western flyway back and forth to West Africa, largely bypassing the areas where hunting of songbirds is a major problem. And yet when Europeans walk out the door these days, they hear or see an estimated 421 million fewer birds than in 1980.

That’s partly because the expansion and intensification of agriculture in Europe displaced natural habitat from the mid-20th century onward. And that same tradeoff is now also taking place, Bairlein said, at critical stopover points on the southern end of the flyway—particularly the Mahgreb region (primarily Morocco and Algeria), to the north of the Sahara, and again in the Sahel (Burkina Faso, southern Mali, Ivory Coast, Ghana, and others), just south of the Sahara.

“Crossing ecological obstacles like oceans or deserts, these birds have to prepare by tremendous fattening, as fuel for their flights,” said Bairlein. Natural habitat on either side of the long flight across the desert functions for birds “like our gas stations, where they have to fill up prior to and after the desert.” But both regions are “currently suffering population growth, overgrazing,” and the rapid loss of natural habitat to make room for increasingly intensive agriculture. As a result, said Bairlein, “we are discussing something like a silent spring.”

It’s much the same story for many New World migratory species, according to Mike Parr, chief conservation officer for the American Bird Conservancy. For instance, wood thrushes spend the winter in Central America, where many countries have already lost half their original forest cover. The loss of that habitat means that females making the return migration across the Gulf of Mexico may not be fit enough when they arrive in the spring to develop and lay eggs. Moreover, the deep North American forests where the birds like to nest are now highly fragmented, leaving them more vulnerable to predation by raccoons and crows.

So does this mean that our springtime, already much quieter than in the recent past, is doomed to become silent? Both scientists claim to be optimistic. Bairlein travels later this month to a workshop in Nigeria aimed at developing sustainable land use strategies. There’s some evidence, for instance, that acacia trees in the dry habitat just south of the Sahara not only benefit migratory birds, but also promote higher soil humidity and thus enable farmers who keep them intact to produce larger crop yields.

Parr also points to small changes that could be a turning point for migratory species. For instance, the forests that now cover large portions of the northeastern region of the United States tend to be about the same age and lack the varied structure many migratory birds need to thrive. But the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resource Conservation Service is now working on selective cutting of forests to introduce more varied habitat. “They’ve a very active program,” said Parr. “They don’t want to see species become endangered because that’s not good for anyone.” It is smarter, and far cheaper, to save a species before it ends up on the endangered species list.

Both scientists also point to international agreements like the Convention on Biological Diversity, which is now pressuring all 168 signatory countries to meet a 2020 goal of having at least 17 percent of their land area in national parks or other protected areas. “The required political instruments…are already in place,” Bairlein writes. “We just need to act.”

October 28, 2016

Texas Shows It’s Too Scared to Stop Folks from Gassing Wildlife

Texas rattlers have good reason to be defensive (Photo: Matt Meadows/Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart

Roughly 125 years ago, Theodore Roosevelt together with a few other pioneering thinkers introduced the idea of “fair chase” in this country. In essence, it holds that if you are going to hunt and kill animals, you should do it ethically, in a way that doesn’t dishonor the hunter, the hunted, or the environment. No canned hunts, no jacklighting, no hunting of animals that are helplessly incapacitated, no commercial slaughter of species like bison and passenger pigeons for the meat market. It was the beginning of the American conservation movement.

That piece of history came to mind as I was reading the latest news out of Texas.

Early this week, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission walked away from a proposal to ban the practice of catching rattlesnakes by spraying gasoline fumes into their dens. Collectors grab the dazed snakes as they bolt from their homes to escape the toxic fumes. You might not imagine such a practice would even exist in the 21st century, much less be a subject of heated debate. But in the small town of Sweetwater, Texas, a rattlesnake festival is the major fund-raiser for the local chapter of the Jaycees, a nationwide nonprofit ostensibly “focused on sustainable impact locally and globally.” At this year’s festival, the Jaycees bought more than 25,000 snakes caught by gassing and proceeded to chop off their heads as a form of public entertainment.

The Texas Parks and Wildlife commissioners, who describe themselves on their website as “honorable” men and women, didn’t try to defend this practice as ethical, honorable, or even sustainable. They merely indicated, by removing the ban from their agenda, that they were sick of hearing about it, after years of protest by scientists, conservationists, and much of the rest of Texas. A spokesperson cited “insufficient support from legislative oversight or the potentially regulated community” for a ban on gassing. That is, bullying by a community of 10,762 people and a few hayseed legislators was enough to get some of the most powerful people in Texas to back off.

There were plenty of reasons the commissioners should have banned gassing. First, it would have done nothing to hurt the rattlesnake festival in Sweetwater. Plenty of other communities in Texas and other states hold such festivals, catching snakes by walking around and picking them up in the traditional fashion. Maybe Sweetwater wouldn’t have been able to collect 25,000 snakes in a single year.

But that was a freak, a result of the Jaycees deciding to pay the exorbitant sum of $10 a pound for live snakes. In the past, the festival has averaged well under 10,000 snakes, and even gotten by with as few as 2,500, and still been a successful fund-raiser. This year’s over-the-top catch was a gesture, another in a long, sad catalog of know-nothings thumbing their noses at science, at the social and political establishment, and at fundamental principles of human decency.

The commissioners should also have acted because the state holds wildlife in the public trust, and its legal mandate is to maintain it based on data from scientists and wildlife managers, who universally opposed gassing.

The language of the proposed ban enumerated many of the ways pouring gasoline into the ground is bad news, especially in the porous limestone that’s common around Texas. It’s bad not just for rattlesnakes but for a host of other species living in and around their dens, including such endangered or threatened species as the Comal Springs riffle beetle, an invertebrate called the Bone Cave harvestman, and the Government Canyon Bat Cave spider.

Ultimately, though, it comes back to basic hunting ethics. “This thing with gassing is not congruent with the principles of American conservation,” said Lee Fitzgerald, a herpetologist at Texas A&M University. “We have very clear norms and principles about hunting that are all about preserving wildlife: You can’t kill deer with automatic weapons and sell every frickin’ one of them you can kill. You can’t put dynamite in a tree hole and blow up a tree to get the squirrels. You can’t hunt wildlife at night, and we even have rules about the kinds of traps you can use for furbearers. And somehow all that flies out the window when it comes to rattlesnakes.”

The chair of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission is T. Dan Friedkin, a Houston car dealer who describes himself as “an avid outdoorsman who is active in wildlife conservation initiatives in the U.S. and abroad.” He is a trustee of the Wildlife Conservation Society, a truly great organization that was founded by the same big game hunters who first preached the gospel of “fair chase.” (Send them a note via Twitter @TheWCS: “Dan Friedkin? Snake gassing? WTF?”) The vice chair of the commission is Ralph H. Duggins, a lawyer in Fort Worth, who says he is “an avid fly fisherman and hunter.” Both of them should know better than to treat gassing rattlesnakes as an acceptable way of hunting. So should all of the honorable commissioners, who have now heaped shame on themselves and the good people of Texas.

If you are a Texan who believes in protecting wildlife, take a look at where these commissioners work. Send them a note about how you feel about gassing wildlife, or just let them know why you are taking your business elsewhere. You should also lodge your protest with the national office of the U.S. Junior Chamber—the Jaycees—via Twitter @USJaycees.

What should you say? Ask the Jaycees exactly what they mean by “sustainable.” Remind them about Theodore Roosevelt and the idea of the “fair chase.” Tell them that wildlife conservation and ethical hunting practices—not gassing—are the great American patriotic traditions they need to protect. Tell themthat gassing rattlesnakes is, in a word, simply un-American.

October 22, 2016

Spider on Drugs

Just in case you missed this important video, suggested to me by David Wagner, eminent entomologist at the University of Connecticut.

It’s Time for the Fur Trade to Protect Big Cats in the Wild

The 20th century fur trade killed 182,564 Amazonian jaguars for their pelts. (Photo: Mauricio Lima/AFP/Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

Reporting last month for National Geographic magazine, I came away with a contrarian approach to the fur trade: Animal rights activists have always wanted to ban fur farming, “but banning doesn’t stop people from wearing fur,” I wrote. “It just moves production to areas where no rules apply,” notably China. A more logical approach would be to keep fur farming legal, particularly in North America and Europe, under regulatory and marketplace pressures intended to make it a model for the entire livestock industry.

Interviewing people who work in the trade, I added one other idea: They know customers increasingly seek assurance that animals are being farmed as humanely possible, and on environmentally sustainable lines. New industry initiatives like Europe’s WelFur farm inspection system explicitly aim to meet those expectations. So why not go a step further? Why not set aside a percentage of each fur coat to support conservation of fur-bearing animals in the wild? It would of course be a marketing tool. But it would also begin to compensate for the unregulated commercial exploitation of spotted cats and other species in the past. I’ll get to the industry response in a moment. First the news:

A study out this week in the journal Science Advances aims to calculate just how devastating that trade used to be. A team of researchers led by André Antunes of Brazil’s National Institute of Amazonian Research focused on the Amazonian basin from about 1904 until the commercial skin trade there effectively ended in 1969, under heavy international pressure.

For his research, Antunes spent years hunting down old cargo manifests and other scraps of commercial and port records, now squirreled away in various libraries and museums. Working with a co-author in New Zealand, he then applied a computer model to calculate harvesting trends for different species. Though Antunes describes the results as a conservative estimate, the numbers are significant—at least 23 million animals killed for the skin trade over a single human lifespan, from an area a little larger than Alaska.

Predators at the top of the food chain, by definition a scarce commodity, were prominent among the victims–182,564 jaguars and 804,080 ocelots and margay cats became fur coats during the period of the study. Other land animals fared even worse—5.4 million collared peccaries, 4.2 million red brocket deer, and 3.1 million white-lipped peccaries.

Surprisingly, given how notorious the fur trade became in the 1960s, the researchers found no evidence that commercial hunting resulted in “empty forests” in the Amazon. That’s partly because the Amazon then was still largely intact and inaccessible forest—unlike some other regions being decimated by the fur trade then. Travel was limited mainly to rivers. That put roughly 80 percent of the forest out of reach for commercial hunters, inadvertently providing a refuge for wildlife to repopulate exploited areas. “Empty rivers,” on the other hand, were common, according to the study, with hunters hammering populations of black caiman (4.4 million animals taken), capybara (1 million), giant otters (386,491), and manatees (110,504), among other species.

The twentieth century Amazonian skin trade evolved as an after effect of the rubber trade, much as wildlife often vanishes today after logging and mining operations open remote forests. A late nineteenth-century boom in rubber prices sent half a million people and a fleet of steamships into the Amazon to gather rubber. When prices collapsed in 1912, those colonists turned to the skin trade instead.

They continued to harvest animals without limit until 1967, when Brazil passed legislation to protect some overexploited species. The trade then limped along until the 1975 ratification of the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which ended international demand for hides from the Amazon.

“Surprisingly no previous studies documented the exploitation of the animals or the resilience of the ecosystem,” according to co-author Taal Levi, a wildlife ecologist at Oregon State University.

And yet it was “a massive international trade in furs and skins.”

Lack of proper historical data means that people trying to understand forest dynamics today may be making false assumptions, according to Antunes, who now works for Wildlife Conservation Society Brasil. In the 1990s, for instance, researchers attributed the depletion of white-lipped peccaries in the state of Acre to local bushmeat hunting. But “these peccary populations had already collapsed in the mid-1940s” because of the skin trade, according to the study, and still have not fully recovered. Lack of data also makes it hard for researchers to recognize ecological effects that may still be cascading through habitats because of the removal of predators, or of peccaries and other seed-dispersing animals.

So how should the fur trade respond to its bloody past, not just in the Amazon but worldwide? When I suggested that the trade should contribute to conservation, the International Fur Federation told me that it already does so.

In fact, it supports the work of a researcher I have written about here named Dan Challender, a leading figure in the fight to end the massive trade in endangered pangolins. Over the past two years, Challender told me, fur industry support for work by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) on sustainable use and trade has totaled upwards of £100,000–roughly $123,000.

But the fur trade is currently a $40 billion a year business. If it really wants to respond to its critics,it needs to be donating millions of dollars —not thousands–to conservation. It needs to take on big projects, like tiger recovery in India, or ocelot recovery in southeastern Texas. You could call that smart corporate citizenship.

Or you could look at the record of 23 million animals killed in the Amazonian skin trade and just call it reparations.

October 15, 2016

Donald Trump and Other Animals

Trump Imagines His Huge Gift (Photo: Photo: Ty Wright/Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff/New York Times

I once interviewed Donald Trump for a magazine story. The topic was rivalries, which seemed like a natural for him. But he was so bombastically short on specifics, so braggadociously vague, that in the end there was nothing to quote. I left him out of the story.

So I was surprised recently to learn, by way of an article in The New Yorker, that Mr. Trump had, in fact, quoted me in a passage from his 2004 book “Trump: Think Like a Billionaire.” I would not have imagined that I had ever written anything he would want to quote.

It’s true that I had written about him in my book, “The Natural History of the Rich: A Field Guide,” published in 2002, but there was nothing remotely flattering there, as a glance at the index seemed to confirm:

Trump, Donald

hangingflies, compared to, 16

Read the full story here.

The Dinosaur Who Taught Us How To Look At Birds

by Richard Conniff/Takepart.com

It’s a little embarrassing to admit this, as a wildlife writer, but I didn’t used to think fossils mattered all that much. I wanted to know what was happening to wildlife right now. And fossils were so very then, so 66 million years ago.The fossil that woke me from my ignorance is named Deinonychus. If that sounds like too much of a mouthful, too much like science, just bear with me for a minute: This story comes with a Jurassic Park plot twist. It also involves correcting a mistake I recently repeated in print.

The Deinonychus story began one afternoon in late August 1964, near Bridger, Montana. John Ostrom, a paleontologist at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, was standing with an assistant on the flank of a conical hill and considering sites for the following summer’s fieldwork—when the answer appeared before them in the form of a large claw eroding out of the slope just below. They soon unearthed an astonishing foot: Two of the three toes had ordinary claws. But from the innermost toe, a sharp claw, sickle shaped and 4.7 inches in length, curved murderously up and out. Ostrom gave the new species the name Deinonychus because it means “terrible claw” in Greek.

The Deinonychus story began one afternoon in late August 1964, near Bridger, Montana. John Ostrom, a paleontologist at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, was standing with an assistant on the flank of a conical hill and considering sites for the following summer’s fieldwork—when the answer appeared before them in the form of a large claw eroding out of the slope just below. They soon unearthed an astonishing foot: Two of the three toes had ordinary claws. But from the innermost toe, a sharp claw, sickle shaped and 4.7 inches in length, curved murderously up and out. Ostrom gave the new species the name Deinonychus because it means “terrible claw” in Greek.

In the public imagination then, dinosaurs were plodding, thunderous monsters, cold-blooded, swamp bound, and stupid. Even paleontologists had lost interest in these “symbols of obsolescence and hulking inefficiency,” Ostrom’s student Robert T. Bakker later wrote. “They did not appear to merit much serious study because they did not seem to go anywhere: no modern vertebrate groups were descended from them.”

Deinonychus didn’t fit the plodding stereotype. On the contrary, he wrote, this toothy, human-size monster “must have been a fleet-footed, highly predaceous, extremely agile and very active animal, sensitive to many stimuli and quick in its responses.” It wasn’t just Deinonychus. To the horror of his fellow paleontologists, Ostrom in 1969 declared “that many different kinds of ancient reptiles were characterized by mammalian or avian levels of metabolism.” It was the beginning of a radical new way of thinking about dinosaurs—and the beginning of a revolution in how we look at some of our most beloved modern wildlife

This is where I made my mistake. In my new book House of Lost Worlds—Dinosaurs, Dynasties, and the Story of Life on Earth, I wrote that Ostrom’s revisionist ideas about dinosaurs spread out from his office at the Peabody Museum to flood popular consciousness, “with countless books, endless computer-generated dinosaurs on television, and multiple iterations of Jurassic Park, the last of these directly inspired by Ostrom and Deinonychus.”

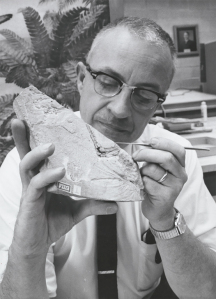

Ostrom and Archaeopteryx

An interview Ostrom gave to The New York Times in 1997 seemed to suggest that novelist Michael Crichton phoned him before writing his 1990 book Jurassic Park. During their conversation, Ostrom told The Times, Crichton ruefully admitted that he had decided not to use the name Deinonychus because Velociraptor—a related species roughly the size of a modern turkey—sounded more dramatic. Ostrom, a modest, scholarly figure, agreed that the name Deinonychus was, yes, maybe a little too Greek.

But that conversation seems to have taken place years later than I thought, when Crichton was in the middle of writing a sequel, The Lost World. Ostrom himself instigated the conversation, with letters congratulating both Crichton and director Steven Spielberg on the 1993 movie Jurassic Park.

Ostrom invited both men to come to the Peabody to see Deinonychus, “the evidence that apparently started the Jurassic Park ball rolling,” he wrote in the letters. The conversation with Crichton took place soon after. Daniel Brinkman, a paleontologist at the Peabody Museum, recently discovered that correspondence in Ostrom’s papers and just this week put out a correction. It is a small correction perhaps, but it is worth setting the record straight because Jurassic Park in all its iterations has become such a global juggernaut.

And it’s worth making the correction as a reminder of just how pervasive Ostrom’s influence was for people everywhere, including Crichton, who had not yet interviewed Ostrom but nonetheless named him not just in the acknowledgments but also in the dialogue of Jurassic Park. It’s also worth thinking about Ostrom’s influence as a reminder that some of his scholarly perceptions are, even today, a little too edgy for the Jurassic Park franchise.

That’s because Ostrom didn’t stop at the idea that dinosaurs could be agile and quick. Beginning in 1970, he also began to catalog similarities in bone structure between Deinonychus and Archaeopteryx, an early bird from 160 million years ago. He went on to publish a series of landmark papers with titles including “The Ancestry of Birds,” “The Origin of Birds,” and “Archaeopteryx and the Origin of Flight.”

As a result, we now know that all modern birds evolved from the group of bipedal theropod dinosaurs that includes Deinonychus and Velociraptor. The idea that modern birds are living dinosaurs is so commonplace that researchers now debate why they were the only dinosaurs to survive the mass extinction of 66 million years ago. Think about that next time you look at the blue jays or ravens in your backyard. They are dinosaurs. They are alive. It is Jurassic Park out there.

Ostrom also predicted that certain dinosaurs would eventually be covered with feathers. He lived to see this idea proved right by the 1996 discovery of a small theropod dinosaur from China with a mantle of short, dark, feather-like filaments on its back. Further discoveries have since changed our ideas so drastically that current conceptions of Deinonychus depict it covered with almost as many feathers as your average bald eagle.

Ostrom also predicted that certain dinosaurs would eventually be covered with feathers. He lived to see this idea proved right by the 1996 discovery of a small theropod dinosaur from China with a mantle of short, dark, feather-like filaments on its back. Further discoveries have since changed our ideas so drastically that current conceptions of Deinonychus depict it covered with almost as many feathers as your average bald eagle.

Think about that when you go see the next Jurassic Park sequel. Steven Spielberg and the rest of Hollywood have gladly followed John Ostrom in making dinosaurs fast and agile. One of these days, they are going to have to follow Ostrom again, giving up that scaly, reptilian, oh-so-1950s science fiction skin and showing us dinosaurs as every schoolchild now knows they existed—with feathers.

October 10, 2016

Dirty Donald Wants You to Believe in Clean Coal

During the course of his rambling, belligerent, bullying remarks in last night’s debate, Republican Presidential candidate Donald Trump at one point remarked, “There is a thing called clean coal.”

This is like asserting that Donald is an honest businessman, a good husband, and a true friend of African-Americans, Mexicans, and women. Anyway, It reminded me of a piece I wrote in 2008 about the origins of the shady myth of clean coal, and why there is, in fact, no such thing:

You have to hand it to the folks at R&R Partners. They’re the clever advertising agency that made its name luring legions of suckers to Las Vegas with an ad campaign built on the slogan “What happens here, stays here.” But R&R has now topped itself with its current ad campaign pairing two of the least compatible words in the English language: “Clean Coal.”

“Clean” is not a word that normally leaps to mind for a commodity some spoilsports associate with unsafe mines, mountaintop removal, acid rain, black lung, lung cancer, asthma, mercury contamination, and, of course, global warming. And yet the phrase “clean coal” now routinely turns up in political discourse, almost as if it were a reality.

The ads created by R&R tout coal as “an American resource.” In one Vegas-inflected version, Kool and the Gang sing “Ya-HOO!” as an electric wire gets plugged into a lump of coal and the narrator intones: “It’s the fuel that powers our way of life.” (“Celebrate good times, come on!”) A second ad predicts a future in which coal will generate power “with even lower emissions, including the capture and storage of CO2. It’s a big challenge, but we’ve made a commitment, a commitment to clean.”

Well, they’ve made a commitment to advertising, anyway. The campaign has been paid for by Americans for Balanced Energy Choices, which bills itself as the voice of “over 150,000 community leaders from all across the country.” Among those leaders, according to ABEC’s website, are an environmental consultant, an interior designer, and a “complimentary healer.” Other, arguably louder, voices in the group include the world’s biggest mining company (BHP Billiton), the biggest U.S. coal mining company (Peabody Energy), the biggest publicly owned U.S. electric utility (Duke Energy), and the biggest U.S. railroad (Union Pacific). ABEC — whose domain name is licensed to the Center for Energy and Economic Development, a coal-industry group — merged with CEED on April 17 to form the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity (ACCCE).

They’re bankrolling the “Clean Coal” campaign to the tune of $35 million this year alone. That’s a little less than the tobacco industry spent on a successful fight against antismoking legislation in 1998, and almost triple what health insurers paid for the “Harry and Louise” ads that helped kill health care reform in the early 1990s. In addition to the ads, the “Clean Coal” campaign has so far also sponsored two presidential election debates (where, critics noted, no questions about global warming got asked).

The urgent motive for an ad campaign this time is the possibility of federal global warming legislation. A cap-and-trade scheme for carbon dioxide emissions may come to a vote in the Senate this June. Coal is also struggling to overcome fierce resistance at the state and local level; Kansas, Florida, Idaho, and California have already effectively declared a moratorium on new coal-fired power plants. Nationwide, 59 new coal-fired power plant projects died last year (of 151 proposed), mostly because local authorities refused to grant permits or because big banks withheld financing. Both groups are alarmed about the lack of practical remedies to deal with coal’s massive CO2 emissions.

The coal industry is clearly alarmed, too, if only about its continued ability to do business as usual. In addition to the “Clean Coal” ad campaign, the industry’s main lobbying group, the National Mining Association, increased its budget by 20 percent this year, to $19.7 million. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, individual coal companies will spend an additional $7 million on lobbying. Coal industry PACs and employees also routinely donate $2-3 million per election cycle in contests for federal office. Altogether, that adds up to a substantial commitment to advertising and lobbying.

And the commitment to clean? The scale of the problem suggests that it needs to be big. Coal-fired power plants generate about 50 percent of the electricity in the United States. In 2006, they also produced 2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide — 36 percent of total U.S. emissions. For a remedy, the industry was banking on a proposed pilot plant called FutureGen, which would have used coal gasification technology to separate out the carbon dioxide, allowing it to be pumped into underground storage. But in January, the federal government canceled that project because of runaway costs. At last count, FutureGen was budgeted at $1.8 billion — with about $400 million of that coming from corporate partners over ten years. That is, the “commitment to clean” would have cost roughly as much per year as the industry is now spending on lobbying and “Clean Coal” advertising.

The business logic of this spending pattern is clear: Promoting the illusion that coal is clean, or maybe could be, helps to justify building new coal-fired power plants now. The tactic is at times transparent: In Michigan recently, a utility didn’t promise that a proposed $2 billion plant would have carbon-control technology — merely that it would set aside acreage for such technology. The proponents of a new power plant in Maine talked about capturing and storing 25 percent of the carbon dioxide emissions, but didn’t say how, and even if they figure that out, the plant would still produce two million tons of CO2 annually.

Actually making coal clean would be hugely expensive. In this country, most research focuses on coal gasification, which aims to remove CO2 and other pollutants before combustion. But only two power plants using the technology have actually been built in the United States, in Indiana and Florida, and the purpose of both was to capture sulphur and other pollutants. Neither takes the next step of capturing and storing the CO2. They also manage to be online only 60 or 70 percent of the time, versus the 90-95 percent uptime required by the power industry. In Europe, researchers prefer post-combustion carbon capture. But the steam needed to recover CO2 from the smokestack kills the efficiency of a power plant.

Since neither technology can be retrofitted, both require the construction of new coal-fired power plants. So instead of reducing emissions, they add to the problem in the near term. And the question remains of what to do with the carbon dioxide once you’ve captured it. Industry has had plenty of experience with temporary underground storage of gases — and researchers say they are confident about their ability to sequester carbon dioxide permanently in deep saline aquifers. But utilities don’t want to get stuck monitoring storage in perpetuity, or be liable if CO2 leaks back into the atmosphere. In any case, data from demonstration storage projects won’t be available for at least five years, meaning it will be 2020 before the first plants using “carbon capture and storage” get built. If predictions from global warming scientists are correct, that may be too late.

A better strategy, argues Bruce Nilles, director of the Sierra Club’s National Coal Campaign, is conservation, with a cap-and-trade system driving overall emissions down by two percent a year over the next 40 years. At the same time, he says, utilities need to increase their reliance on wind and solar power, supplemented by natural gas. Nilles thinks this may already be happening. In Colorado, Xcel Energy, which generates 59 percent of its power from coal, recently shelved a proposed 600-megawatt “clean coal” power plant; it’s now seeking to develop 800 megawatts of new wind power by 2015.

Finally, industry and environmentalists together also need to figure out a funding mechanism for research to make “clean coal” something more than an advertising slogan. (One possibility being debated in Europe: Instead of giving away cap-and-trade emissions permits to industry, auction them off, with some of the revenue going to research.) Nilles is also holding out for a “clean coal” technology that can be retrofitted on existing plants.

But nobody expects coal to give up dirty habits easily. Some coal advocates are already trotting out one dire study by M. Harvey Brenner, a retired economist from Johns Hopkins University. It takes a hypothetical example in which higher-cost alternative energy sources replace 78 percent of the electricity now produced by coal — leading to lower wages, higher unemployment, and the death of 150,000 economically distressed Americans per year. (In another scenario described by Brenner, 350,000 Americans die annually because they did not show coal the love.) Only a spoilsport would add that the study was paid for by the coal industry and that the article appeared not in a peer-reviewed journal, but in a trade magazine. Someone from ACCCE is probably already on the phone. “BURN COAL OR DIE” is a little crude as an advertising slogan. But the clever folks at R&R Partners can no doubt polish it into something that will make “Harry and Louise” want to get up and dance.