Richard Conniff's Blog, page 21

May 31, 2016

I’m Telling Tales About Dinosaurs & Discovery in New Haven Thursday

May 29, 2016

Animal Music Monday: “Little Red Rooster”

Sometimes I suspect that songs about animals are really songs about people, only slightly disguised.

But you will be shocked, shocked, as I am I, that some callow writer would interpret a gentle barnyard ditty like “Little Red Rooster,” made famous in 1961 by the Chicago blues singer Howlin’ Wolf, as the “most overtly phallic song since Blind Lemon Jefferson’s ‘Black Snake Moan'” in 1927.

And, wait, wait, wasn’t Blind Lemon really singing about his ophidophobic nightmare of a snake loose in the bedroom? And when he finishes with “Black snake mama done run my darlin’ home,” that’s about a strong woman coming to the rescue, right? I mean, with a broom or something?

Some British Invasion rock group later picked up “Little Red Rooster” and had a hit. But let’s go with an upbeat version from 1963 by Sam Cooke, which includes some interesting musical imitations of dogs barking and howling. (P.S. That part is really about dogs.) :

May 27, 2016

Texas Tunnels Under for Ocelots

(Photo: Francis Apesteguy/Getty Images)

by Richard Conniff, for Takepart.com:

Back in the fall of 2014, I took a whack at the Texas Department of Transportation for treating the nation’s only viable population of endangered ocelots—beautiful spotted cats about twice the size of a house cat—as fodder for roadkill. The department had flagrantly disregarded recommendations from wildlife experts on the critical need for safe road crossings, instead installing an impassable concrete barrier down the center of a busy highway bordering a national wildlife refuge.

TxDot, as it’s known, responded with a note suggesting that they were hurt, deeply hurt, by my suggestion that they were anything less than acutely sensitive to the needs of wildlife. But it would cost $1 million apiece for crossings in the area of that concrete barrier. Not that anyone was counting. They had only asked whether it was worth spending that kind of money on a species nearing extinction in this country so they could “learn and understand the historical dynamics of wildlife survival.” This was at a time when the relevant dynamic was that highway accidents were causing 40 percent of all ocelot deaths.

But occasionally good things happen, even in the unlikeliest places. So I am delighted to report that TxDot is now doing something to protect ocelots in their last remaining patch of habitat. (It may have helped that you and readers of other articles about the plight of the ocelots let your feelings be known, so thank you for that.) The state last month began installation of a dozen wildlife underpasses in and around the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge, a 98,000-acre coastal habitat near Brownsville, at the mouth of the Rio Grande.

Four of them, spaced at half-mile intervals, will help ocelots get around (or under) that concrete divider on Highway 100, which runs south of Laguna Atascosa and carries heavy vacation traffic to South Padre Island. Another eight are already being put into place on FM106, which may sound like a radio station but is actually a farm-to-market road that borders and runs through Laguna Atascosa. The work there will cost just $1 million, because the tunnels are part of an overall upgrading of the road; the retrofit on Highway 100 will cost $5 million.

The work is happening at a critical moment for the ocelots. Fewer than 100 of them survive in and around the refuge, and seven have died in road accidents since last June. “We were devastated, since almost a year had passed with no reports of ocelots hit by cars,” said Hilary Swarts, a wildlife biologist who monitors the ocelots for the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. That first death took out an adult female, a major loss because females are the limiting factor in population growth. “Males can go impregnate multiple females in a relatively short time, but females have to gestate and lactate,” said Swarts. “Basically a female, from the second she gets pregnant, you’re talking about two years before she’s ready to have another offspring.”

Each gender has its little hell. The other six highway victims were males, not surprisingly, said Swarts, “since they have such a rough time of it once the older males start to see the younger males as competition for mates and territory.” The younger males typically get pushed out of the dense, brushy habitat where they grew up and into the increasingly developed outside world with its deadly highways.

While the progress on wildlife crossings is good news, it may not be enough to protect the ocelots adequately. Three of the recent deaths took place on a road called Highway 186, about five miles north of the refuge, where wildlife crossings are under discussion but are not actually being built.

Last fall TxDot posted signs saying “Wildlife Crossing—Next Two Miles,” but it doesn’t appear to have helped: Another male died there just last month.

In addition to the new wildlife crossings, the refuge is working with neighboring landowners to establish permanent wildlife corridors for ocelots and other species in the area. Private landowners already have more of the ocelots than does the refuge itself, said Laguna Atascosa manager Boyd Blihovde. “Many times ranchers that are interested in hunting, even though they have crops or cattle on the property, will want to preserve native vegetation,” he said, including the thorn scrub vegetation that ocelots require. “My goal as a refuge manager is to help ranchers continue doing what they’re doing, owning and protecting the land, and maintaining a working ranch so they don’t feel the need to sell it off to a developers.”

Subdivisions are almost as deadly as highways for the ocelots. Blihovde said the recent settlement in the BP Deepwater Horizon case will help that cause, with new funding available for ranchers to enter into conservation easements that will keep them on the land while protecting the conservation value of the property in perpetuity.

Meanwhile, two-and-a-half cheers for TxDot for getting the highway ocelot crossings started. And three cheers for those rare sensible people among us who drive a little bit slower than they might like, not just around Laguna Atascosa but anywhere with enough room for wildlife to thrive. I was driving on the coast of Maine the other day—yes, a little over the speed limit—and I had a sick feeling when a chipmunk bolted out in front and went thump under the left rear wheel. And that was just a lousy chipmunk. You don’t want to know what it must feel like to kill an endangered ocelot.

May 22, 2016

Animal Music Monday: “Monkey Man”

I’ve always loved “Monkey Man,” from the Rolling Stones “Let It Bleed,” mostly for the great intro by Bill Wyman, on vibraphone and bass, and then for Keith Richards’ guitar. Oh, hell, I should say I also love it because I identify so strongly with the words, “I am just a monkey man.” Old childhood nickname.

What puzzles me is that the song was inspired by Italian pop artist Mario Schifano, after Mick Jagger and Keith Richards made cameo appearances in the Schifano film “Umano non Umano” (“Human not Human”), produced by Richards’ girlfriend Anita Pallenberg, in April 1969. Schifano was an interesting artist, but it’s a crap film.

See for yourself. Here’s Jagger in “Umano non Umano”:

And here are some critically insightful comments on Jagger’s performance, via YouTube:

“Jagger is acting here like he needs to pee urgently. Hard to believe the singer of this legendary incendiary song and this clown are one and the same.”

And: “Why does Mick look like he’s all dressed up to go to the prom here?”

May 20, 2016

How Natural History Museums Open Peoples’ Minds

Making new friends at the American Museum of Natural History (Photo: Jon Hicks/Corbis Documentary)

by Richard Conniff, for Takepart.com

Recently I wrote a piece about the worldwide decline of natural history museums, partly at the hands of know-nothing politicians who don’t want to hear what science has to say. It stirred up a lot of strong emotions.

His Dimness

Readers protested what they called “the closing of the American mind” and the “denaturing of humanity.” A lot of them objected especially to the decision by first-term Gov. Bruce Rauner of Illinois to shut down the Illinois State Museum after 138 years. Rauner made his millions at a private equity firm specializing in leveraged buyouts and roll-ups—that is, spinning corporate numbers while producing nothing. But it somehow made sense in his dim little mind to save $4.8 million a year in state funding for the museum, even though it meant losing $33 million in tourism revenues—and that’s not counting the value of the scientific research such museums routinely produce. (You can speak up for the Illinois State Museum in a note to Gov. Rauner. On the subject line, I suggest you write, “Fat Wallet, Dim Mind.”)

But along with the anger, readers also remembered how natural history museums had helped open their own minds. One reader wrote that “my heart still beats faster each time I approach the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco,” and a former New York City resident recalled his childhood delight in discovering the dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History: “I immersed myself in each tableau, completely captivated by the recreated reality, which connected me directly to the great natural world beyond my urban surroundings.” That seminal experience

opened the doors “to science and to love of the natural world,” enriching his life forever after, as it has done for countless other city children. (If you want to enjoy that sort of experience, you can become a member of your local natural history museum and get free access to a nationwide network of sister museums.)

Other readers recalled dazzling moments at natural museums around the world. One was overwhelmed at seeing the first fish “to crawl out of the water nearly 400 million years ago” and a foot-long dragonfly wing, both at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Another reader celebrated the extensive Darwin Centre recently added to London’s Natural History Museum, adding, “It’s hard to imagine the building of a Darwin Center in the U.S.” other than as a form of protest. Indeed, the state of Kentucky decided this year to hand $18 million in tax subsidies to a religious group called Answers in Genesis for a Noah’s Ark theme park scheduled to open in the summer. No naturalists need apply.

But my article also knocked the natural history museums, or at least the ones that have resorted to entertainment, rather than science, to boost attendance. One of the most poignant notes came from Reed Noss, a University of Central Florida biologist who has devoted his life to conservation: “As a child, my favorite place, after the woods and streams, was the Dayton Museum of Natural History in Dayton, Ohio. This museum not only displayed, but actively practiced and taught natural history in those days.” He took summer classes there in birding, fossils, the ecology of streams, reptiles and amphibians, and other subjects. Then about a decade ago, he took his family back to show them this inspirational scene from his childhood.

“We were horrified by what we found,” Noss recalled. “There was virtually no natural history on display. No truly educational exhibits. The place had been turned into a playground, with stupid games, slides, big plastic tubes to crawl through, and other nonsense.” It now calls itself the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery, maybe because the words natural history are just a little too edgy for tender Ohio minds. “Shame on you,” Noss concluded. “I shall never return.”

One thing readers neglected to mention: Natural history museums matter not just in shaping children’s minds but as centers for the kind of scientific research that shapes our understanding of the world. Most visitors don’t even realize that natural history museums, unlike most “science” museums, employ scientists behind-the-scenes to do important research with their collections.

Deinonychus

So let me tell you about my favorite specimen, an early Cretaceous dinosaur named Deinonychus, which I came to know in the course of writing my new book, House of Lost Worlds, about the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. Paleontologist John Ostrom discovered the five-inch-long claw of this creature sticking out of a Montana hillside in the summer of 1964. He spent the next few years gathering more fossils and studying them in painstaking detail. It led him to conclude that dinosaurs were not the plodding, stupid, swamp-bound evolutionary dead end they were then generally thought to be. They could be fast, agile predators, with metabolisms akin to that of modern mammals. The idea caused shrieks of horror among other paleontologists, but Ostrom prevailed, launching the modern dinosaur renaissance.

Then he began to notice similarities between the wrist bones of Deinonychus and Archaeopteryx, the “original bird” from 160 million years ago. That led Ostrom to argue that birds are living dinosaurs—the only dinosaurs to have survived the great extinction event of 66 million years ago. That idea is now accepted by almost all natural scientists, and it makes the creatures fluttering around our streets and yards infinitely more interesting.

But OK, if that’s not enough to make you see the value of natural history museums, let me also resort to entertainment: Ostrom’s Deinonychus in time became the model for the terrifying velociraptors in the Jurassic Park franchise. In real life, velociraptors were about the size of chickens, not genuinely big and scary like Deinonychus. But after doing his research with Ostrom, author Michael Crichton just decided velociraptor sounded sexier.

So, yes, natural history museums matter, in all kinds of ways—and yes, they are vanishing. I should end on another reader, who responded to my article with the words of novelist and playwright Thornton Wilder: “Every good thing stands moment by moment on the edge of danger, and must be fought for.” He concluded, “We must fight to protect these great institutions against the forces of ignorance and greed.”

END

Why, yes, yes, yes, of course you can buy my new book! How kind of you to ask! Just click here to buy from Amazon (and if you do, please also post a review), or click here to buy from your local independent bookstore, because they also need your support.

Oh, hey, one last thing. I took a closer look at Bruce Rauner’s tie (see below), and its a bunch of fishing lures. So apparently the guy has some interest in the natural world. Do you think he might sense some vague connection between the natural history science at the state museum and the fish he seems to enjoy catching?

Think again.

May 15, 2016

Animal Music Monday: “We Like the Zoo (‘Cause We’re Animals Too)”

A lot of people are turned off by zoos these days, because of that captivity thing. This song skips happily past that whole debate, and instead plays on zoos as the place where city and suburban kids often feel their first connection with the animal world. The writer is Walter Martin, bassist and organist with The Walkmen, and father of two young girls. Here he’s on his first solo album, from 2014. The singer is Matt Berninger, frontman for The Nationals.

Here’s Martin’s explanation: “‘We Like The Zoo (‘Cause We’re Animals Too)’ is my tribute to

the lost art of the novelty song. Songs like ‘Poison Ivy’ and ‘Yakety Yak’ – all those Leiber and Stoller masterpieces – are a big part of my life. I didn’t want to put my name on an album that didn’t have room for that kind of song.” Berninger adds that he likes seeing the animals at the zoo because, “I recognize something that’s inside of me.”

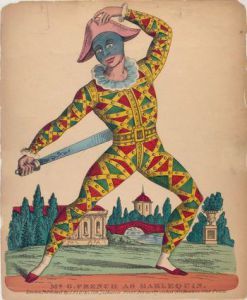

That harlequin look

Both artists appear on a Day of the Dead, a charity tribute album to the Grateful Dead, being released later this week.

By the way, the loony dancer in the video, dressed harlequin-style, is the fashion model Lily McMenamy.

May 13, 2016

A Dam Pushes A Great American Fish Toward Extinction

by Richard Conniff, for Takepart.com:

“We should be grandfathered in.” That’s how the manager of the Lower Yellowstone Project irrigation district in Montana put it. His farmers have been using a dam on the river to supply water to their fields since time immemorial—or for 112 years, anyway—and see no reason to change. But the pallid sturgeon would certainly say it should be grandfathered in too. The monster fish has depended on the river for 78 million years, roughly since Tyrannosaurus rex ruled this region.

The problem is that the farmers and their timber-and-rock dam are now killing off the sturgeon. Intake Dam is an unimpressive structure, located near Glendive, Montana, just before the Yellowstone River joins up with the Missouri River. The dam—really just a weir—stretches for 700 feet across the Yellowstone but does not even rise above the water surface in some seasons. The irrigation district has to pile on new stones each year just to make it back up enough water for its purposes.

So the Intake is easy to overlook—and allows some people to celebrate the 692-mile-long Yellowstone as “the longest undammed river” in the Lower 48. But the dam blocks off 165 miles of upstream habitat that the sturgeon would otherwise use for spawning. Because of that,

only about 125 pallid sturgeon survive in the entire Upper Missouri River region. They are magnificent fish, up to five feet long and 85 pounds, that can live for as long as a century. But these fish, the largest wild population of pallid sturgeon in the country, have not reproduced successfully in about 60 years.

Even if the sturgeon manage to get together in the absence of their old spawning grounds, their young now just drift downstream into the Missouri River, where they die in the oxygen-deprived waters of a lake backed up behind another dam, built in 1956. So the pallid sturgeon—one of eight sturgeon species in North America—has been on the endangered species list since 1990, with no sign of recovery.

The United States Army Corps of Engineers, which built the dams that are largely responsible for endangering the pallid sturgeon and many other species, is apparently determined to build yet another dam, replacing the wood-and-stone structure at Intake with concrete, at a cost of $60 million. It has proposed moving the pallid sturgeon around the new dam with a two-mile bypass, though many fishery biologists have said that would never work. When Defenders of Wildlife and the Natural Resources Defense Council filed a suit to stop the project last year, even the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks joined in with an amicus brief. A federal judge granted an injunction to delay the project, and the Army Corps is now scheduled to deliver a revised Environmental Impact Statement at the beginning of July, followed by a public comment period. Depending on that EIS and the outcome of the lawsuit, the dam project could move forward as early as next year. Or the dam could come down and give the sturgeon back their old breeding grounds before it’s too late.

“We believed we had to step in to stop this terrible project,” said Jonathan Proctor, the Rockies and Plains program director at Defenders of Wildlife. The Bureau of Reclamation, which oversees the operation of dams and irrigation programs, should “open the river and deliver the water to the farmers by alternative means,” he said. Knocking down the dam and replacing it with pumping stations could do the job, he added, while also protecting the sturgeon. Adding wind power to run the stations would avoid hitting the farmers with a big electric bill. Conservation measures would also help, as the irrigation district now loses 66 percent of the water it pulls from the river through seepage, evaporation, spillage, or otherwise.

What Proctor did not mention is that the whole project serves the needs of a relative handful of farmers, mainly growing sugar beets on 56,000 acres of otherwise arid land. And sugar beet production is dependent on another, considerably larger federal handout, a subsidy program that The Wall Street Journal recently characterized as “an egregious business welfare scheme.” Both directly and by its indirect effects on the market, that program has cost the nation an estimated $15 billion since 2008 and 120,0000 jobs since 1997. Those estimates come from the Coalition for Sugar Reform, which largely represents business interests, so we should take them with a grain of salt, not sugar. Even so, the subsidies—$300 million in 2013 alone—dwarf the pittance the federal government has spent defending the pallid sturgeon. And yet the sturgeon, not the sugar beet, is our true heritage as Americans.

But let’s set that aside. Defenders of Wildlife would prefer to just say it’s possible to have a “win-win” on the Yellowstone River, with both the farmers and the sturgeon getting the water they need. But for that to happen, our “longest undammed river” must actually be undammed. You’ll have to wait till July to comment on the Army Corps’ revised assessment, but there’s no harm in making your voice heard about this issue now, loudly and often.

Go here to send a note to the Army Corps of Engineers (choose “Executive Office” and address your note to Lt. Gen. Thomas P. Bostick) or here for the Bureau of Reclamation. Feel free to play the emotional angle: “Your children want you to let the pallid sturgeon live.” Or just get right to the point: “Intake Dam must come down.”

May 11, 2016

At Swim With Five Tons of Shark Per Acre in the Galapagos

(Photo: Enric Sala/National Geographic)

Yep, that’s how many sharks researchers found living in the northern Galapagos Islands, according to a new study in PeerJ. And of course the researchers found out by diving and swimming transects to count the fish they saw en route. Not sure this would qualify as “nice work if you can get it.”

They did the research around Darwin and Wolf Islands, in part of Ecuador’s .

The results:

Nearly 73% of the total biomass (12.4 ± 4.01 t ha−1) was accounted for by

sharks, primarily hammerheads

(Sphryna lewini—48.0%), Galapagos (Carcharhinus galapagensis— 19.4%), and blacktips (Carcharhinus limbatus—5.1%). Hammerheads occurred on 92% of transects at SE Darwin, 59% at SE Wolf, and 9% at both NW Darwin and Wolf. Gringos (Paranthias colonus) were the third most abundant species by weight, accounting for an additional 18.3% of the total biomass. They were 2.2 times more abundant by weight in 2013 (3.8 ± 4.1) compared with 2014 (1.7 ± 2.4). Gringos were 48% more abundant in the SE (3.5 ± 3.5) compared with the NW (2.4 ± 3.7) exposures.

That figure, 12.4 ± 4.01 t ha−1, works out to a little more than five tons of shark per acre. The abundance is partly a result of a unique confluence of ocean currents:

Galapagos is the only tropical archipelago in the world at the cross-roads of major current systems that bring both warm and cold waters. From the northeast, the Panama Current brings warm water; from the southeast the Peru current bring cold water; and from the west, the subsurface equatorial undercurrent (SEC) also bring cold water from the deep (Banks, 2002). The SEC collides with the Galapagos platform to the west of the Islands of Fernandina and Isabela, producing very productive upwelling systems that are the basis of a rich food web that supports cold water species in a tropical setting like the endemic Galapagos penguin (Spheniscus mendiculus) (Edgar et al., 2004). The oceanographic setting surrounding Galapagos results in a wide range of marine ecosystems and populations, that includes from tropical species like corals or reef sharks to temperate and sub-Antarctic species like the Galapagos fur seal (Arctocephalus galapagoensis) or the waived albatross (Phoebastria irrorata).

The far northern islands of Darwin and Wolf in the 138,000 km2 Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR) represent a unique ‘hotspot’ for sharks and other pelagic species (Hearn et al., 2010; Hearn et al., 2014; Acuña-Marrero et al., 2014; Ketchum et al., 2014a). Most of the studies around this area have focused on the migration of scalloped hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna lewini) and other sharks species between Darwin and Wolf and other localities in the Eastern Tropical Pacific (Hearn et al., 2010; Bessudo et al., 2011; Ketchum et al., 2014a). An ecological monitoring program has visited the islands over the past 15 years with a strong sampling focus to survey reef fishes and invertebrate communities (Edgar et al., 2011). However, no study to date has examined extensively the abundance, size, and biomass of sharks and other large predatory fishes around Darwin and Wolf. We conducted two expeditions to Darwin and Wolf in November 2013 and August 2014 to establish comprehensive abundance estimates for shark and predatory fish assemblages at Darwin and Wolf.

The researchers urged Ecuadorian officials to provide strict enforcement of their new marine reserve, at a time when overfishing has decimated stocks of sharks and other large predatory fish, now down by an estimated 90 percent worldwide.

May 9, 2016

John Oliver: How Not to Report Science

May 8, 2016

Animal Music Monday: “Piggies”

George Harrison wrote the original “Piggies” for The Beatles White Album, released on November 22, 1968. But I ran across this interesting instrumental cover from 2015 on YouTube. If the tune were not so familiar, you might mistake it for a pretty bit of folk music from the early baroque era:

I asked a musician friend to comment. He performs baroque and Renaissance music and, as it happened, had never heard the original Beatles tune. So he listened with an unbiased ear:

“This track started (and concluded, as well) as a completely convincing piece of Italian or Iberian music from the 17th century, in the spirit of Ucellini or Merula or dozens of others. Other than a few goofy chords in the bridge, there is little to give away that it is anything else. Unfortunately, it devolves in the middle section to a more diffuse “pan-Baroque” feel; just kind of a tacky pastiche. But aside from that, a pretty convincing articulation that “popular” music is kind of timeless and has been built on the same idioms and practices for centuries.”

Harrison intended the song as a harmless satire on the grubby, self-serving ways of the rich. According to Song Facts, he originally wrote one verse that was dropped from the final recording but resonates in a post-2008 world:

Everywhere there’s lots of piggies playing piggie pranks

You can see them on their trotters

At the piggy banks

Paying piggy thanks

To thee pig brother.”

The song produced one appalling response: Though it’s better known that “Helter Skelter” from the same album fueled Charles Manson’s crazed apocalyptic vision, he also read horrifying meanings into other songs from the White Album, including “Piggies.” Manson took the line “What they need’s a damn good whacking” as part of the rationalization for the Manson Family raid on the home of actress Sharon Tate on August 9, 1969, leading to the murder of Tate, then eight months pregnant, and four others. The killers used knives and forks, ostensibly to echo the lines “You can see them out for dinner/With their piggy wives/ Clutching forks and knives/ to eat their bacon.” Police found the words “pig and piggy” written on the living room wall in the victims’ blood.

Original Beatles tracks are generally not available on YouTube, for copyright reasons. But here’s something more like the original from the White Album, with apologies for the animation: