Richard Conniff's Blog, page 25

January 30, 2016

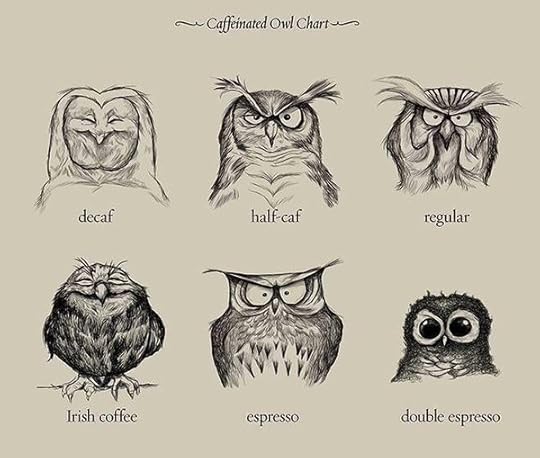

Handy New Key for Identifying Owl Species

January 29, 2016

Want More Crab and Lobster? Go Fish for Lost Gear

A boat filled with recovered crab pots. (Photo: CCRM/VIMS)

Chesapeake Bay watermen took it hard in 2008, when their blue crab industry was officially declared a commercial failure. The blue crabs are to the Chesapeake what lobsters are to Maine, not just a major contributor to the economy but also the object of a venerable waterman culture, based on crab pots in warmer weather and dredging in winter.

Faced with decline of this iconic industry, Virginia opted to shut down the winter crab harvest in its waters. Scientific studies had shown that it dredged up a disproportionately large number of reproductive females, meaning fewer crabs to catch in future years. The crabbers were skeptical, at best, when the state offered to put them back to work during the winter retrieving derelict and abandoned crab pots. Pulling up empty crab pots in winter is nobody’s idea of a good time.

But the pots weren’t empty, “and that’s the headline,” said Kirk Havens, a biologist at William & Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS). In the middle of winter, the pots were loaded with bycatch, almost all of it dead—not just crabs, but striped bass, perch, catfish, even drowned muskrats and diving ducks.

That started to get the watermen, who had previously considered lost pots irrelevant to the fishery, thinking differently. It also led to a new study in the online journal Scientific Reports arguing that a program to recover as little as 10 percent of derelict crab and lobster pots worldwide could increase crustacean landings by almost 300,000 metric tons, worth $831 million annually, in addition to the benefit to nontarget wildlife.

The idea for the program arose when Havens and co-author Donna Bilkovic, a VIMS marine ecologist, were mapping the bay bottom with the help of side-scan sonar. “We kept seeing these weird rectangular shapes,” said Havens. They turned out, on closer inspection, to be abandoned crabs pots. A lot of them. Chesapeake Bay watermen put out up to 800,000 pots every year, and routinely lose 20 percent of them to storms, boat propellers, and other causes. Because the pots are metal, they can last and continue “ghost fishing” for years afterward, with the bodies of their victims serving as a form of continual “self-baiting” for other victims.

Federal disaster-relief funding for the fishery meant a chance to see if stopping or at least reducing this bycatch could make a difference, said Havens. Beginning in 2008, the recovery program put 70 watermen to work, searching along a systematic grid for lost pots. Havens and his academics had toyed with some sort of grappling device to recover the pots. “But the watermen looked at that and said, ‘Hmm, we’ll just do something else,’” said Havens. Instead, they put bent nails through rope at one-foot intervals, and snagged a total of 34,408 derelict crab pots to the surface over six years.

Removing the traps cost $4.2 million in total. But according to the study in Scientific Reports, it resulted in a 27 percent increase in catch—roughly one extra crab in every working pot–for an economic benefit of $21.3 million over what would have happened had the abandoned pots remained in place.

“People will argue about the amount,” said Chris Moore, Virginia senior scientist for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, who was not involved in the study. But “one of the great things about this study is that it attempts to commoditize what our losses are from this derelict fishing gear. We generally talk about these kinds of programs as doing good work, but we seldom get to quantify how they contribute dollars to the economy. This study starts to put the question in cost-benefit terms.”

At the moment, the recovery program has ended in Virginia because disaster-relief funding ran out. But this study obliges Virginia to ask whether “we should start putting money toward these programs so we will reap the benefit of a greater fishery later on,” said Moore. The same question ought to be debated in other fisheries, from lobsters in Maine to crabs in Southeast India, according to Havens and his co-authors.

Both the local and global benefit estimates in the study are based on the goal of recovering 10 percent of derelict pots. But what about the 90 percent of lost pots that would remain on the bottom? Researchers at VIMS have also tested a biodegradable escape hatch suitable for any pot in current use. It costs about $1 per pot and uses PHAs, (Polyhydroxyalkanoates), a family of naturally occurring biopolyesters, which marine bacteria break down over the course of a year. After that, any crab or lobster pot still on the bottom would be harmless.

Will watermen take up the escape hatch idea? It’s too soon to say, according to Havens, but he says he is already seeing changes in attitude about derelict pots.

This past summer, “I saw a crabber with a load of derelict traps in his truck, and I asked him about it. He said, ‘Oh some of my buddies were throwing them in the water. But I’m taking them to the dump.’ That wouldn’t have happened in the past.”

The Making of a Naturalist: Bill Stanley

Bill Stanley, a mammalogist at the Field Museum, prematurely appeared on the Wall of the Dead last year, after succumbing to a heart attack, age 58, while running a trapline for rare species in Ethiopia.

Now the Field Museum has posted a nice video about the flipping of a switch that turns a kid into a naturalist. Check it out.

January 19, 2016

Walk on the Wild Side! A Tale of Wine & Sex in the Vineyard

(Photo: Timm Schamberger/AFP/Getty Images)

My latest for Takepart.com:

Some of the finest things on Earth—among them beer, bread, and wine—depend on yeast. But after more than 5000 years of reliance on its powers, and endless modern research into yeast genetics, we knew almost nothing until recently about its natural history. The many strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the fungus we call yeast, were considered entirely domesticated, the cats and dogs of fermentation.

That began to change a few years ago, when researchers in Italy discovered that yeast has a wilder side. It summers on ripening fruit, which is how we first discovered its magical ability to turn humble grapes into wine. But it overwinters, the researchers reported, in the guts of social wasps, as the wasps are hibernating through the winter, sealed within the trunks of oak trees.

With a new study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the natural history of yeast has just become even richer. If Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the common yeast we buy at the supermarket, is the household pet of brewing, Saccharomyces paradoxus is its wild cousin, the wolf running through the woods. Although geneticists recognized that some of the most successful yeasts in industrial fermentation represented crosses between the two, they didn’t know where the crossover came from.

Now Duccio Cavalieri and his co-authors at the University of Florence report that cerevisiae hears the call of the wild and mates with paradoxus within the intestines of hibernating wasps. Using yeasts with easily identifiable genetic markers, the researchers fed the two different species to wasps. Conditions in the foregut cause the yeasts to make reproductive spores, contained in a sort of sac called the ascus. Conditions in the lower intestine later break open the sac, releasing the spores. That’s where gametes of domestic and wild yeasts fuse, producing a hybrid.

Other scientists have already put the earlier research on wild yeast to work for the lofty purpose of brewing better beer. “Wild yeasts have always been considered a contaminant in brewing and you want to keep them out, because they create off-flavors,” John Sheppard, a bioprocessing specialist at North Carolina State University told National Geographic. “Actually the opposite was true. We got some really nice fruity, flowery esters that gave it a nice taste and aroma, combined with a moderate sourness.”

Cavalieri also believes that understanding the natural history of yeast could lead to better wine. He gathers some of the wasps for his studies from the grounds of Tuscany’s celebrated vineyards and suspects that the community of yeasts and social wasps “contribute to the end product in terms of taste and aroma. Without them, maybe Montepulicano and Montalcino would not be the same.”

What do the wasps get out of this arrangement? In the summer, said Cavalieri, the wasps are the lions of the ecosystem, and the vineyards are their savanna.

Wasps are of course attracted by sugar, as anyone who has discovered a yellow jacket in a can of soda may painfully remember. But they are also predators. “In particular they love eating other insects, they eat Drosophila in large amounts, they eat honeybees, they eat other wasps.”

A wasp nest hole (Photo: Carlotta De Filippo)

But during their long winter hibernation, the wasps are vulnerable. Their nests are hidden in oak tree trunks, and the tiny entrance is sealed shut with their saliva. There, “they must survive three months with the danger of cold weather and infection. We think that maybe yeast can protect them. We really do think there is some unknown interaction” for which the wasps depend on the yeast. ” This may be why wasps are powerfully attracted to the aroma of yeast, as well as to sugar.

Cavalieri argues that understanding this

natural history could change vineyard methods. One of the less romantic sides of harvesting grapes has to do with the abundance of wasps feeding on the ripe fruit. Workers routinely get stung and vineyard operators naturally reach for the nearest pesticide. “We think there is a benefit to not killing them at harvest,” said Cavalieri. “We think the wasps provide an ecosystem service, increasing the diversity of fermented products.”

Crabro wasp on ripe grapes in a Tuscan vineyard (Photo: Carlotta De Filippo)

Vineyards also typically make heavy use of fungicides against various pathogens—but at the risk of reducing the diversity of yeast in the process. Some vineyards, he said, have slowly begun to experiment with organic methods. They’re “not going complete organic, but when they start to recognize the importance of biodiversity, they start to do things in a thoughtful way. They can intervene only when they really need to and not interfere with important ecological processes.”

The hidden power of the natural world—of yeasts, and social wasps, and oak trees—can thus find its way into the glass of beer or wine that is one of the finer rewards of living on Planet Earth.

January 11, 2016

Researchers Find Deadly Salmon Virus on the Pacific Coast

A salmon feeding at the mouth of Capilano River in West Vancouver, British Columbia. (Photo: Andy Clark/Reuters)

My latest for Takepart.com:

A pathogen that is “arguably the most feared viral disease of the marine farmed salmon industry” has now turned up for the first time in farmed and wild fish in British Columbia, according to a new study in Virology Journal. The co-authors warn that the presence of the virus, called infectious salmon anemia virus (ISAV), could greatly increases the risk of devastating outbreaks for salmon fisheries from Alaska down to the Pacific Northwest.

“This is first of all a salmon virus, and a member of the influenza family and it mutates easily and rapidly,” said co-author Alexandra Morton, an independent marine biologist. “There is no place in the world where this virus has existed quietly. It has always caused a problem. It was detected in Chile in 1999, and nothing was done to contain it. They allowed it to reproduce and mutate, and in 2007 a form appeared that swept the coast and caused $2 billion in damage.”

The B.C. Salmon Farmers Association promptly responded to the new study with a fierce attack on its science. “We have great concerns about the methodology, and the ethics of the researchers involved, given their history of reporting false positives with respect to ISA,” said Jeremy Dunn, executive director. “None of the results reported in this paper have been confirmed by an outside laboratory.”

Morton called the response unhelpful. “This is a dangerous virus to the industry and to the wild salmon, and we need to deal with this in a scientific way,” she said, adding that the fish farmers had denied her group access to farmed salmon for testing. “They deny everybody access. It really inhibits the work. You have to go and get the dying fish out of these farms and test them.”

Instead, Morton and her co-authors tested more than 1,000 farmed and wild salmon from British Columbia supermarkets and found evidence of ISAV in 78. The virus also turned up in sea lice from the Discovery Islands, a region known for salmon farms, raising concern that the pathogen was introduced from open net fish farming.

The new study used PCR (polymerase chain reaction) technology, the standard technique for amplifying segments of DNA and identifying them to a particular species. But in a comment forwarded by the BC Salmon Farmers Association, Gary Marty, British Columbia’s chief fish pathologist, argued that the paper did not “provide a balanced review” of the thousands of past PCR studies on BC salmon that were negative for the virus. He also raised the “possibility of sample contamination” in the “cramped, untidy conditions” of the laboratory where the new PCR studies took place.

If there had been contamination, Morton replied, the ISAV found by the new study would have been an exact match for ISAV found elsewhere. Instead, the researchers found a mutation at a critical area sampled in PCR testing. “This is a difficult strain of ISAV to detect,” she said, “and it is easy to see how it was missed,” in past studies. Different laboratories also use different methods and they interpret the results using different standards.

But Morton said the new study had “cracked the code” for ISAV, with a methodology that passed peer review in one of the top virology journals. “We not only got detection of the virus, we got pieces of the virus, and ran them through GenBank,” the National Institutes of Health genetic database, “which is like running a fingerprint.”

Morton conjectured that resistance to the new study was based mainly on the economic value of the wild and farmed salmon industry, worth perhaps $1 billion a year in British Columbia. ISAV is a “notifiable” disease, meaning that, if the finding is confirmed, Canada would be obliged to report it to the International Organization for Animal Health in Paris. That notification would permit other countries to block imports without fear of incurring trade penalties. “If B.C. is positive for ISAV,” said Morton, “the United States and other governments will in all likelihood close theirs borders to the export of farmed salmon,” and salmon eggs.

“What needs to happen now,” she said, “is that all laboratories need to do the same test—so we don’t compare apples to oranges—and we need access to the farmed fish. So far no one has stepped up to accomplish that. It is critical that we learn from what happened to Chile. In my view, this work gives B.C. the opportunity to avoid tragic consequences.“

January 8, 2016

The Dark, Nasty Business of Ethical Shopping

My latest for Takepart.com:

Though I have written here often about illegal fishing as a leading factor in the “empty oceans” crisis, I still feel like an ignoramus every time I attempt to make an ethical purchase at my supermarket seafood counter. As a crude rule of thumb, I could just assume that everything imported is illegal. But only about a third of imported seafood actually fits that description, and supermarkets seldom bother to label their merchandise by origin, in any case.

So why not just break out my Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch guide, to help me make a sustainable choice? That’s what I tell readers to do. But I am a hypocrite: Shopping this way makes me feel like those hipster restaurant customers in “Portlandia,” fretting about whether the woodland-raised, soy-fed heritage breed chicken named Colin is really the ethically pure choice for dinner. By default I end up buying anything other than shrimp, because I know shrimp is almost always terrible for the environment. Then my wife goes and buys the shrimp anyway, and we have a fight.

Is it any wonder that consumers everywhere opt for willful ignorance? If it’s pretty and the price is right, we buy it—and try not to think about whether somebody cut down a rainforest to produce it, or dumped antibiotics into waterways, or relied on child labor, or committed any of a hundred other ethical sins. Even consumers who care about such things seldom follow through by doing the research and sorting out the information to make the ethical choice. It’s just too damned complicated.

Now it turns out, according to a new study in The Journal of Consumer Psychology, that it’s worse than simply throwing up our hands. We also ridicule people who try to do better. Even worse, that ridicule (which is half the pleasure of watching shows like “Portlandia”) also makes us less likely to behave ethically in the future.

Ohio State University consumer psychologist Rebecca Reczek and her co-authors started out considering two opposing views of human behavior. One optimistic perspective held that seeing other people behave ethically would elicit “a built-in emotional responsiveness to moral beauty” leading to what social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has called “warm or tingly feelings, positive affect, and a motivation to help others,” summed up as “elevation.” The other theory proposed that seeing ethical behavior might just lead to a lot of nasty commentary.

In the new study–Surprise!–the second, pessimistic view of human nature turned out to be more accurate. Skip the elevation, bring on the denigration!

Reczek and company asked test subjects to choose a pair of jeans based on a limited number of criteria, picking just two criteria from a list that included style, price, color (dark or regular wash), or some ethical consideration. Most consumers skipped right past the ethical consideration, as the researchers expected from their previous work on willful ignorance.

But the real point of the study came afterwards. Asked to comment on the behavior of other consumers, willfully ignorant test subjects conceded that ethical consumers might be more compassionate. But good luck with that: They were also odd, boring, and plain. Exactly why did these unsexy, fashion-blind little wackos even bother to buy jeans in the first place?

As Reczek interprets these results, “Willfully ignorant consumers put ethical shoppers down because of the threat they feel for not having done the right thing themselves. They feel bad and striking back at the ethical consumers makes them feel better.”

Beyond that, the study also found that the implied moral admonition tended to make willfully ignorant test subjects even less likely to behave ethically in the future. “They think, ‘That person’s just weird and boring and stupid and now that I’ve said that I care even less about being sustainable in the future.’”

So what should we take away from this not altogether flattering view of how we behave? How should we act when the choices we make—for instance, whether to buy that beautiful and incredibly inexpensive bed made of Vietnamese rainforest wood—are destroying wildlife habitat everywhere? And when our seafood purchases are helping to empty the oceans?

First, says Reczek, manufacturers and retailers need to step into the breach. “We know that people are not going to seek out the information about ethical considerations. So it’s not enough to put it on your web site and assume people are going to find it. It needs to be right on the shelf or on the product.” If you’re the manufacturer or the retailer of that bed, say, you need to tell people where the wood comes from and whether it was from a certified sustainable forest. “The onus is on you as the manufacturer to push that information out to the consumer.”

Consumers like me also need to overcome our fear of looking like ethical idiots and ask the questions, or at least confine our shopping to businesses that provide the answers: Where did this wood come from? How were these fish harvested? Because of social media, says Reczek, willfully ignorant consumers are now more likely to find out when a friend goes the extra mile on some ethical consideration. That means we also need to beware of this “vicious circle where you put down people who make ethical choices and then that leads you to care less and act less ethically in the future.

Finally, for people who are actually making the ethical choices and hoping to get other people to follow their good example, it may help to step off the moral high ground. Reczek has a vegan friend who blogs about it as “this very moral choice, and every time I see it, I think, ‘I know you’re trying to win people over, but you’re turning them off. They think you’re weird and it makes them hostile.”

In short, hold the sermons. (No promises here, but maybe we’ll hold the disparaging comments, too.) The road to better behavior is paved with high spirits and good recipes.

January 6, 2016

How Our Food Waste Messes With Wildlife

My latest for Yale Environment 360:

The world wastes more than $750 billion worth of food every year — 1.6 billion tons of food left in farm fields, sent to landfills, or otherwise scattered across the countryside, plus another seven million tons of fishery discards at sea. That waste has gotten a lot of attention lately, mostly in terms of human hunger.

Hardly anyone talks about what all that food waste is doing to wildlife. But a growing body of evidence suggests that our casual attitude about waste may be reshaping the way the natural world functions across much of the planet, inadvertently subsidizing some opportunistic predators and thus contributing to the decline of other species, including some that are threatened or endangered.

A new study in the journal Biological Conservation looks, for instance, at California’s Monterey Bay, where the threatened steelhead trout population has declined by 80 to 90 percent over the past century. Efforts to restore the species along the Pacific Coast have focused on major initiatives like the recent demolition of a dam that had blocked access to critical steelhead breeding grounds on the Carmel River, which empties into Monterey Bay.

But a team of co-authors led by Ann-Marie Osterback, a marine ecologist at the University of California-Santa Cruz, suspects that garbage and fishery discards might also play an underrated part in the problem. The hypothesis is that local food wastes inadvertently subsidize Western gulls in the Monterrey Bay area, and these gulls in turn prey on the juvenile steelhead trout.

The dramatic decline in steelhead numbers would normally mean that fish-eating birds around Monterey Bay would have to move down the food chain to survive. That’s what’s happened to Brandt’s cormorants and marbled murrelets, and their populations have declined as a result.

But according to Osterback, the number of gulls have doubled or quadrupled in different parts of the bay just since the 1980s — thanks to a steady diet of landfill garbage and fishery discards. Osterback and her co-authors found that each individual gull now eats less steelhead than in the past, but the combination of a greatly increased gull population and a severely reduced run of steelhead trout adds up to a dramatic rise in predation pressure. She estimates that the gulls may eat up to 30 percent of juvenile steelhead en route to the sea.

Likewise, yellow-legged gulls subsidized by food wastes in the western Mediterranean, threaten Auduoin’s gulls, European storm petrels, and other vulnerable seabirds through increased predation pressure. Off the coast of Alaska, fishery-subsidized killer whales imperil near-threatened Steller sea lions. And on the western side of the Mojave Desert, common ravens and coyotes that feed on garbage from nearby communities are jeopardizing the recovery of the threatened desert tortoise.

“Ravens scavenge when refuse or carrion are available but they are also capable hunters,” a study in Ecology found. The researchers put out 100 dummy models of juvenile desert tortoises and found that ravens attacked 29 of them over a two-month period. Other studies have linked subsidized ravens to the decline of such threatened or endangered species as marbled murrelets, California least terns, snowy plovers, San Clemente loggerhead shrikes, and sandhill cranes.

Animals have of course been picking up the food scraps we leave behind forever — or at least long enough to change the course of their evolution. That’s how certain wolves evolved into domestic dogs. But nothing in the history of the planet approaches the scale of modern food waste, in farm fields, on streets and beaches, in landfills, and strewn behind fishing boats.

This abundance of garbage is also a factor in the resurgence of brown bears (population 17,000) and wolves (population 11,000) in modern Europe. Garbage is also the main reason leopards have been able to adapt to living in and around major cities in India. They prey on other animals that scavenge from abundant garbage — dogs, pigs, goats, and rats — and they also feed directly on butchered carcasses discarded in the open.

Removing or controlling garbage is not new as a conservation tool. The U.S. National Park Service did it in the 1970s at Yellowstone National Park, closing dumps and ending the artificial feeding of bears there. But it also sparked one of the nastiest fights in the history of U.S. conservation, especially as the park service began killing or translocating “incorrigible” bears. Cut off from their familiar food sources, the grizzlies struggled and their population declined for a time. Gradually, though, the bears shifted to a more natural diet, moved away from the roads, and ultimately flourished. The Yellowstone grizzly population has roughly quadrupled since the end of artificial feeding in the 1970s, to about 700 bears in 2014.

Measures to address the garbage problem on a broader scale today will likely be at least as challenging. On the one hand, such measures can reduce populations of subsidized predators without the controversy caused by programs to kill or relocate nuisance animals. A study in France demonstrated that closing a dump led to a 49-percent decline in fertility of herring gulls, which are also opportunistic predators. Another study in the western Mediterranean found that a temporary moratorium on trawling had a dramatic impact on gull reproduction, by removing the discards that can otherwise make up as much as 73 percent of their diet.

But when the European Union was debating a ban on fishery discards in 2013, ecologists warned of “unforeseen knock-on consequences.” They pointed out that 52 percent of seabird species worldwide now scavenge fishery discards to some degree. A ban would leave some species hungry, and some might turn to eating other bird species to survive.

The EU is currently moving ahead with its ban in three phases. Now in its second year, it’s too soon to say how it is affecting seabirds. Daniel Oro, a fisheries ecologist at the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Studies on Majorca, worries about the potential effect on the critically endangered Balearic shearwater, a seabird that frequently depends on fishery discards while rearing its young. “We are going to have smaller populations of Balearic shearwaters, that’s very clear,” said Oro. “Populations suffer a period of readapting to the new system. Many individuals are going to die, as happened with bears at Yellowstone.”

But Oro also considers the cleanup essential. Before the closing of the only dump on Majorca, he said, researchers found that many of the birds there “were low-quality individuals. They had physical problems, they had lung problems, and other diseases that were not easily seen from the outside.” The dump supported birds that natural selection would have weeded out in the wild.

Cleaning up our food waste mess and shifting wildlife populations back to natural resources increases competition and ultimately “benefits higher quality individuals,” said Oro, “so that’s good news.” But, as at Yellowstone, he acknowledged, getting there will be painful.

December 31, 2015

Hope for Wildlife in the New Year

This is from Dr. Cristián Samper of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). He takes a closer focus on government action than I normally do, because I am a cynic about such things. But I’m hoping he’s right, and it’s worth a read for that reason:

Yes, wildlife across the globe faces threats from all angles, including climate change; over-hunting and over-fishing; illegal wildlife trade; and habitat destruction and degradation. But during this past year, I found a spirit of hope for wildlife.

In 2015, countries across the globe took important steps on behalf of wildlife that provided hope for their future protection. (Photo: Mileniusz Spanowicz ©WCS)

As I reflect on 2015, here are a few of the events that will have a positive impact on wildlife and wild places: Some were taken by the global community and others on a national or local level. I’ve included some of the actions where WCS is leading the way. Thankfully, this list of wildlife wins in 2015 could be even longer. So, I welcome hearing about more actions you think were great for wildlife this past year. I will be sure to Tweet those additions to show them support. [Note: You can follow Samper on Twitter @CristianSamper.]

Paris Climate Summit: The agreements in Paris at the Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was a major step forward in 2015 for wildlife and for all life on our planet. The climate accord, agreed to by 195 countries, shows a commitment by the global community to reduce the greenhouse gases warming our planet. One aspect of the accord not given a lot of attention was recognition of the urgent need to take significant actions to reduce emissions of CO2 caused by deforestation, representing around 15% of global emissions (more than all the cars, trucks, and airplanes in the world combined). This push to save intact forests is good for all life and protects wildlife habitat and

absorbs carbon dioxide through continued growth. Wildlife needs intact forests, from the tropics to the boreal regions.

One aspect of the Paris climate accord not given a lot of attention was recognition of the urgent need to take significant actions to reduce emissions of CO2 caused by deforestation. (Photo: Julie Larsen Maher ©WCS)

The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals: The United Nations General Assembly adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals in September. These will drive much of the development agenda for our planet for the next 15 years and include a wide range of actions, such as ensuring sustainable use of natural resources; taking urgent steps to end wildlife trafficking; and conserving our oceans. The goals and 169 targets in the document represent an unprecedented opportunity to safeguard globally threatened wildlife species and their habitats.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals adopted in September will drive much of the development agenda for our planet for the next 15 years. (Photo: Julie Larsen Maher ©WCS)

United Nations Resolution on Wildlife Trafficking: In July, the UN adopted a first-ever resolution that recognizes that wildlife trafficking is a transnational crime, which is threatening species, communities and local economies across the globe. The resolution calls on governments to take strong actions against this crime, including annual reporting on progress. It further recognizes links between wildlife crime and international organized crime.

In July, the UN adopted a first-ever resolution that recognizes that wildlife trafficking is a transnational crime. (Photo: Elizabeth Bennett ©WCS)

A Trade Agreement with Hope for Wildlife: In October the United States joined 11 Pacific Rim countries in signing the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), an international trade agreement that includes strong wildlife trafficking provisions within its environmental chapter. It was heartening to see in the TPP potentially strong and enforceable commitments on combating wildlife trafficking, and on implementing the provisions of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna (CITES). We look forward to working with the 12 signatory countries to implement the terms of the agreement.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), forged in October, includes strong wildlife trafficking provisions within its environmental chapter. (Photo: ©WCS Wildlife Crimes Unit)

‘One Health’ Breakthrough for Africa’s Farmers and Wildlife: The World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) provides standards for its 180 member countries related to international trade in commodities (including beef) that are a potential source of animal disease agents. In May, it updated its Terrestrial Animal Health Code. This change unlocks the potential to remove fences and restore migratory movements of wildlife across the vast southern African trans-frontier conservation areas (TFCAs), including the Kavango Zambezi TFCA spanning Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe and home to the world’s largest remaining population of elephants — approximately 250,000.

In May, the World Organization for Animal Health updated its Terrestrial Animal Health Code, restoring migratory movements of wildlife across the vast southern African trans-frontier conservation areas. (Photo: Julie Larsen Maher ©WCS)

Good News for the Oceans: Our oceans and the wildlife that call it home got a boost from new protections with the declaration of new marine protected areas. The Government of Chile announced at an oceans summit in Valparaiso the creation of a 720,000-square-kilometer marine protected area around Rapa Nui and its plan to design a network of marine protected areas in Patagonia for the purpose of safeguarding whales, dolphins, sea lions, sea birds, and other coastal biodiversity. This initiative would expand the country’s protected waters by 100,000 square kilometers (more than 38,000 square miles). Madagascar also took actions to protect ocean life by establishing three new marine parks. Located along Madagascar’s western coast in what is known as the Mozambique Channel, the new parks are home to the world’s second-most diverse coral population.

2015 saw the creation of new marine protected areas in Chile and Madagascar. (Photo: Ambroise Brenier ©WCS)

Banning Microbeads in the United States: President Obama has signed into law a ban on microbeads. The U.S. Senate and House both swiftly voted in December to ban the use of these tiny plastic particles from certain personal care products that are harming aquatic wildlife and polluting waterways. We are hopeful that in 2016 other countries will take similar action to ban microbeads, a significant threat to ocean wildlife.

In December, President Obama signed into law a bill to ban the use of plastic microbeads in personal care products. (Photo: Jeff Morey ©WCS)

An International Blitz Against Wildlife Trafficking: Anytime you can say China and the USA are taking actions together to address a problem, this surely can mean big change for the good. In September, President Xi of China and President Obama issued a joint commitment to address wildlife trafficking, including steps to halt the domestic commercial ivory trade in both countries. This builds on efforts by range countries in Africa that have called on the closing of global ivory markets. When this commitment is fully implemented in China and the US, and by other countries, it will be good news for Africa’s beleaguered and declining elephant populations. Additional action addressing ivory demand: Washington State voters passed I-1401 a ban on the trade in parts of elephants and other species. Washington joined California, New York and New Jersey, which have already enacted ivory bans. The 96 Elephants coalition of partners is fiercely working to achieve a federal ivory ban in early 2016, accompanied by the enactment of ivory and broader wildlife bans in several remaining key states, including Hawaii, the largest existing U.S. ivory market.

In May, President Xi of China and President Obama issued a joint commitment to address wildlife trafficking, including steps to halt the domestic commercial ivory trade in both countries. (Photo: Julie Larsen Maher ©WCS)

Zoos Making a Difference for Wildlife: Zoos across the world inspire millions of visitors (181 million just in North America) while simultaneously spearheading and supporting conservation initiatives across the globe. The 220-plus AZA-accredited zoos spend $160 million on conservation initiatives annually and fund more than 2,500 conservation projects some 100 countries. At WCS, we harness the power of our zoos and aquarium, along with our conservation programs, to conserve wildlife in nearly 60 nations and in all the world’s oceans. There are myriad stories from 2015 that could illustrate the contribution of our parks in saving wildlife. Here is one example: The Queens Zoo in partnership with other entities, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Roger Williams Park Zoo, reintroduced 11 zoo-born New England cottontail rabbits, back into the wild in its native range. The partners hope to have greater success next year in an effort to ensure the viability of this important species, which is classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN. New England cottontail rabbit numbers have declined as a result of habitat loss and through competition with eastern cottontails.

In 2015, The WCS Queens Zoo reintroduced 11 zoo-born New England cottontail rabbits back into the wild in their native range. (Photo: Scott Silver ©WCS)

And a Final Word from The Pope: On June 18, Pope Francis issued an encyclical on the environment. His message to 1.2 billion Roman Catholics that caring for nature is an important part of all of our lives has resonated deeply around the world, within and beyond the Catholic Church. This encyclical and other statements from the Pope have urged everyone to be aware that we have an obligation to be mindful stewards of our planet. Whether in the encyclical, when he visited Africa and spoke out against the ivory trade, during his trip to the United States, or at the end of the year when images of wildlife were projected on the Vatican, Pope Francis proved to be a strong, outspoken supporter who is inspiring individuals and governments to do the right thing for our planet and its precious wildlife.

Pope Francis has proved to be a strong and outspoken proponent for protection of our planet and its precious wildlife. (Photo: Cristián Samper ©WCS)

Those are 10 of the major actions taken this year that make me optimistic for wildlife. On a more personal level, my hope is based on something closer to home. As head of WCS, I am blessed to work with champions for wildlife within our organization and within the many governments, corporations, and other NGOs that partner with us. Knowing the tireless dedication they bring to their work every day gives me my truest sense of hope for the many diverse and magnificent species on our planet.

December 29, 2015

Among 2016 Conservation Issues: Way Too Much Testosterone

What’s ahead for wildlife in the coming year? Anybody reading the headlines would probably answer: Calamity and extinction. Elephants? Rhinos? Lions in the African bush? Pollinators here at home? None of it sounds like good news.

For the past few years, a group of scientists and others with a strong interest in the natural world have tried to look past the headlines and identify emerging conservation issues most people in the field aren’t talking about yet, but will soon. They call it “horizon scanning,” and they try to include opportunities as well as threats. The new list for 2016 is just out in the journal Trends in Ecology & Evolution, and it makes for interesting reading.

The list the group came up with inevitably includes China, but for a reason that hasn’t gotten much attention so far: The national government has now incorporated the idea of becoming an “ecological civilization” among its leading policies. If you have been hearing about the recent pollution red alert in Beijing, or about poaching and deforestation issues pretty much anywhere in the world, the words “ecological civilization” probably have you muttering, “Fat chance.” China has always been better at inventing ambitious slogans than at living up to them.

But according to one recent analysis, the new policy could mark “a real transformation of the growth model … a final break with the ‘pollute first, clean up later’ policies of the recent past.” The list of planned actions includes preservation of wetlands and “scientific development of marine resources,” as well as major water management and reforestation initiatives. The authors of the Trends article argue that change in China, if genuine, could encourage environmental reform in other nations, “particularly if these principles are promoted through China’s investments overseas.”

China is still of course bankrolling 92 coal-fired power plants in 27 nations, even as it committed itself at the recent conference in Paris to climate change reforms. The Trends authors also list among their emerging issues the increasing construction of artificial oceanic islands. That’s a reference to China’s move to assert national territorial claims in the South China Sea by “pumping sand onto live coral reefs and paving the sand with concrete,” with devastating effects on wildlife and regional fisheries. So it is probably wise to consider the likelihood of real change in China a gigantic “if.”

Fisheries turn up in several of the other upcoming issues cited by the Trends authors. On the freshwater side, pollution with estrogen is already a familiar problem: We basically piss away the ingredients in birth control pills, and the result is reproductive and other hormonal havoc for the creatures living in our waterways. But we are apparently now pissing away testosterone, too, with similar results. There’s rarely a good medical reason to take testosterone supplements–but sales in the United States have soared from $18 million in 1988 to $2.1 billion (according to IMS Health) in 2014.

On the marine fisheries side, receding sea ice threatens to open up large areas of the central Arctic Ocean to unregulated fishing. The five border nations signed a moratorium in 2015, but they need to begin negotiating legally binding rules to avoid “uncontrolled and unsustainable levels of harvest.” One other developing issue is the fishing industry’s increasing reliance on “electric pulse trawling,” which uses a jolt of electricity to flush flatfish and shrimp out of their seabed hiding places. It’s an indicator of the hazards for nontarget species that China—China!—banned the practice in 2001. But the European Union allows it, and the Trends authors worry that electric pulse trawling is growing “ahead of a full understanding of its ecological effects.”

So what’s the good news for wildlife? New technologies are making it much easier to detect illegal activities and stop them. For instance, most larger fishing vessels are now required to carry satellite-tracked automatic identification systems. That allows enforcement agencies to spot boats fishing in the wrong place or with the wrong methods. Even if they can’t get to the scene on time, they can prevent those boats from selling their illegal catch when they return to port. Passive acoustic monitoring over large areas is also becoming more practical. At sea, it’s a way detect the idiots who use explosives to stun or kill fish (and everything else) along coral reefs. On land, it’s already helping alert rangers to illegal logging in Sumatra. The Trend authors argue that improvements in how batteries store energy will allow remote devices to function far longer in the field, and artificial superintelligence will interpret the resulting data far more effectively than mere mortals. (HAL, from “2001: A Space Odyssey,” apparently has an unanticipated future as a forest ranger.)

To this list of opportunities for 2016, I would add two legal advances. The recent Paris agreement on climate change has placed huge new emphasis on the protection of forests as a tool for offsetting human actions. And in this country, the re-authorization of the Land and Water Conservation Fund, with a budget of $450 million for the New Year, means that many important habitats stand a chance of being preserved well into the future.

One final thought, for the authors of the Trends article: If you had to identify leading issues of the past year—in any field—the list would surely include the idea that developing nations and disenfranchised people should participate as equals in global decision-making. And yet, inexplicably, the group of experts preparing this list remains overwhelmingly British, even English. It includes only four scientists from outside Europe, and none from China, India, or Africa, which together represent half the people on Earth. So here’s an issue I’d put on the list for 2017: If you are going to talk about “global” anything, why not bring together a representative global group to do the talking?

December 22, 2015

Why Predators Matter

There are no doubt plenty of contenders in the category “most destructive thing humans have done to Planet Earth,” but killing off predators has to rank near the top. And it is a continuing crime against nature.

Looking just at modern times, the list of predators we have driven to extinction includes North Africa’s Atlas bear, North America’s short-faced brown bear, the Caspian tiger, the thylacine (a marsupial carnivore in Tasmania), and the Zanzibar leopard, eradicated in the 1990s because of nonsense folklore about witchcraft.

We have pushed the few remaining big predators into a sad vestige of their old territory. Leopards are now gone from 66 percent of their range in Africa and 85 percent in Eurasia. Tigers are down to just seven percent of the territory they once ruled. African lion are on the brink of extinction in the wild, with just eight percent of their former range. Gray wolves, exterminated from the entire United States except Minnesota and Alaska, have in recent decades managed to slip back into a half-dozen or so other states, but only against the most violent resistance.

Why are we so terrified of predators? We are haunted by the ghosts of our evolutionary history, much as are pronghorn deer. They evolved to outrun North American cheetahs—and still run that fast even though the cheetahs went extinct 12,000 years ago. You might imagine that humans would be smarter than that, and yet we continue to run from our entire history with predators, and that of our primate ancestors. That is, our history as dinner. We have served in that capacity for lions, leopards, tigers, crocodiles, snakes, saber-toothed cats, sharks, and an ungodly assortment of other predators. Is it any wonder that predators still make us twitch?

On top of fear, add the illusion of economic interest. Ranchers rage that predators kill their livestock. But the reality is that they hate them with an irrational intensity basically because their daddies always did. Cattle die far more often from bellyaches or bad weather. Predators ranked just seventh among causes of death in this USDA study. But it’s easier for ranchers to take out their frustrations on the predators. Economic interest has also shaped the approach taken by many state Fish and Wildlife agencies: Their budgets come largely from hunting and fishing fees. So they kill predators in the mistaken belief that it is the best way to be sure that there are plenty of elk, deer, moose, and other targets for the hunters.

This is an odd way to manage wildlife because it goes against a half-century of modern science. In fact, the recognition that predators are the essential managers of ecosystems dates back at least to Aldo Leopold, former wolf killer. In his 1945 essay “Thinking Like a Mountain,” he described mountains overrun by deer, in the absence of wolves, where he had “seen every edible bush and seedling browsed … seen every edible tree defoliated to the height of a saddlehorn” until in the end the deer themselves died from overpopulation and lack of food.

Scientific studies since then have repeatedly borne out this key insight that predators are essential to healthy ecosystems. The University of Washington’s Robert Paine first demonstrated a “trophic cascade”—that is, a cascade of effects through an entire food chain–by removing predatory starfish from a coastal habitat for a classic 1966 study. Mussels, which had previously clung to rocks high up along the tide line, advanced deep into the newly predator-free territory. A mussel monoculture soon displaced limpets, goose-necked barnacles, sea anemones, and other species, destroying the former diversity of life.

Likewise, when researchers asked why kelp forests had disappeared from the coastal waters of Alaska, the answer turned out to be overhunting of sea otters. In the absence of these predators, sea urchins proliferated and nibbled the forest down to the sea bottom. According to a follow-up study early this year, that trophic cascade may explain why the Steller’s sea cow, which grazed on kelp beds, went extinct soon after the beginning of the Pacific maritime fur trade in the eighteenth century.

Since the pioneering research on starfish and sea otters, studies have proliferated demonstrating just how destructive it can be to eradicate predators. You can see a good summary of them here.

Our emotions may tell us that predators are cruel and destructive. Certain badly misguided philosophers have even tried to turn that into an argument for extirpating all predators. But the reality is that this would disrupt ecosystems, set off a chain of extinctions and extirpations, and inflict far greater cruelty on the species inhabiting those ecosystems.

We need to learn to tolerate and even celebrate predators—even predators living in the middle of human communities. Our present mindless program of pushing them to extinction is a prescription for planetary ruin.