Richard Conniff's Blog, page 26

December 22, 2015

Christmas 1940: My Father’s Poem

I found this poem by my father among his papers, after his death. He had a seriously bad family life then, as a 20-year-old, and everybody also knew this might be the last peacetime Christmas before the U.S. entered World War II. Read it, be thankful for what peace we have, and have a Merry Christmas:

The beeswax lit and the holly hung,

And three kings on their knees;

The ancient hymns and the carols sung,

And snow in the branchy trees.

A whistling wind on the frozen ponds,

The moon on the mantled loam;

The canes on the scented balsam’s fronds:

The wise man turns him home.

–James C.G. Conniff, 12/18/40

December 19, 2015

Bright Lights, Big Predators

Street life in Mumbai (Photo: Steve Winter)

My latest for The New York Times:

IT was tea break one afternoon this past May, in a business park in Mumbai, one of the world’s most crowded cities. The neighborhood was chockablock with new 35-story skyscrapers adorned with Greek temples on top. On the seventh-floor deck of one building, 20-something techies took turns playing foosball and studying the wooded hillside in back through a brass ship captain’s spyglass.

They were looking at a leopard, also on tea break, up a favorite tree where it goes to loaf many afternoons around 4:30. That is, it was a wild leopard living unfenced and apparently well fed in the middle of the city, on a dwindling forest patch roughly the size of Central Park between 59th and 71st Streets. When I hiked the hillside the next day, I found a massive slum just on the other side, heavy construction equipment nibbling at the far end, and a developer’s private helipad up top. And yet the leopard seemed to have mastered the art of avoiding people, going out by night to pick off dogs, cats, chickens, pigs, rats and other camp followers of human civilization.

Welcome to the future of urban living. Predators are turning up in cities everywhere, and living among us mostly without incident. Big, scary predators, at that. Wolves now live next door to Rome’s main airport, and around Hadrian’s Villa, just outside the city. A mountain lion roams the Hollywood Hills and has his own Facebook page. Coyotes have turned all of Chicago into their territory. Great white sharks, attracted by …

Click here to read the rest of the article.

December 14, 2015

Your Pretty Face is an Ecosystem

The genus name “Demodex” means “lard worm” and they live on your forehead. (Photo: All Species Wiki)

My latest for Takepart.com:

When people talk about wildlife, they’re generally thinking about wolves running through forests, or maybe squirrels skittering around the neighborhood trees. But let’s look a bit closer to home: Blink. Wildlife just took a ride on your eyelashes. If that makes you lift your eyebrows in puzzlement (or dismay), well, there’s animals in your eyebrows, too.

In fact, your face is an ecosystem of long standing for two species, which have been passed on for generations in your family. They probably climbed aboard while you were nursing at your mother’s breast. Demodex folliculorum has evolved to live in human hair follicles. Its cousin Demodex brevis ensconces itself slightly deeper in the microhabitat of your sebaceous glands.

Follicle mites, as they are commonly known, are distant relatives of spiders. They eat our dead skin cells, or maybe the oils, bacteria, and fungi on our skin, and they are, I should quickly add, utterly harmless. It’s even possible they perform some sort of housekeeping service, making us mutually beneficial: We give them habitat, they minimize zits. But no one really knows for sure. In any case, mites have co-evolved with humans and pre-humans for millions of years.

A study released Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that mites may also provide a sort of skin-deep view of our genealogy and shed new light on

the history of human migration. Bowdoin College evolutionary biologist Michael Palopoli and his co-authors sampled the follicle mites from 70 individuals, using the standard technology in the field: They scraped a bobby pin across the forehead of their test subjects. Then they analyzed the scruffy material trapped in the crook of the bobby pin.

I wasn’t part of the study but, as it happens, I once went through at least the first part of this process in the course of reporting a story about life on the human body. The researcher I was working with placed my sample onto a glass slide and examined it for a moment under his microscope. “Oh wow,” he said, causing my eyebrows to rise nervously. Then, as if congratulating me, he said, “You’ve got the best population I’ve ever seen!” And this was a guy who had spent his entire career looking at follicle mites. He showed me the evidence under the microscope. The adult mites looked like sticks of wood lying crisscross (lots of them), with stumpy little legs that wriggled and twitched. They had tiny claws and needlelike mouthparts for consuming skin cells. “Look at ’em all,” he cried, unable now to suppress his delight. “Holy moley!” He admired my forehead as if there were gold in them thar hills.

I’m just putting this out there to establish my credentials as a biodiversity expert.

The researchers in the new study took a more sophisticated approach, analyzing a short segment of DNA from each sample. (As is common in such studies, they used DNA from the mitochondria, the energy factory of the cells. In most species, it’s inherited only from the mother, and that makes it a useful tool for tracing evolutionary lineages.) The analysis revealed that different mite lineages are associated with different continents, and that these ancestral lineages tend to stay with families even generations after they move to a different continent.

The greatest diversity of mites occurred in people of African origin. That’s not surprising because most of human evolutionary history took place in Africa, and previous studies have shown that the genetic diversity of humans is also greatest there. Europeans and Asians are subsets of that diversity. But the researchers were surprised to find that African Americans with a long history in North America “have retained mites originally inherited from Africa rather than exchanging mite populations regularly with individuals of European descent.”

That suggests, first, that mites are not highly mobile, and are passed on only through intimate contact within the family. Because the ancestry of African Americans is on average 24 percent European, it also suggests that other factors may minimize the spread of mite lineages. The “skin traits” theory argues, for instance, that mites may be keyed in to differences in skin types, meaning hair follicle density and distribution, skin hydration, oiliness, or other factors.

The current study was too small to say anything definitive. But for co-author Michelle Trautwein at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, it suggests bigger studies to come. “The exciting thing, first, is the idea that we have animals living in our face. It’s just shocking for people, and it’s a reminder that we are intimately part of nature, even though we think we are distant from it. And then that we are part of this evolutionary process and that this interesting arachnid can be a storyteller, and help us recover some of our evolutionary history in ways that were unexpected.” Further studies, she suggested, might help sort out the migratory history of the people in Madagascar, just 250 miles off the east coast of Africa, but with strong genetic links to Borneo. Or they might help decipher the early history of humans in the Americas. The study of mites could also provide medical insights into the skin condition called rosacea, a reddening and swelling that has afflicted Bill Clinton and W.C. Fields, among others. It appears to be associated with certain European mite lineages.

Some people worry that even talking about the existence of mites on the face is a bad idea. They’re afraid it will cause people to suffer delusory parasitosis, the disabling paranoia that invisible insects are crawling on our bodies. But here is a better way to respond to the latest news from the world of follicle mites: You can start your day now in front of the bathroom mirror and set aside all that nonsense about fat or thin, young or old. Instead stare into the mirror and in a clear, proud voice announce, “This is an ecosystem!” Given the abundance of humans on Earth, it’s also one form of biodiversity that’s unlikely to go away any time soon.

How the World Looks to Reindeer

This is how the world looks from under the chin of a reindeer on migration in Norway. It’s from a project by the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. Here’s how they describe their work:

Taken from GPS collars equipped with wide-angle cameras, these amazing shots represent an unprecedented window into the lives of reindeer, one of the most ancient deer species in the world. Few people are aware that within the heart of Europe there still exist mass migrations as spectacular but more secretive than those in the Serengeti. Yet, reindeer

migrations represent one of the most endangered phenomena in the Northern hemisphere. Wild reindeer are extremely wary of humans, who have been harvesting them since pre-historic times using large-scale pitfall systems. Their anti-predator strategy consists of aggregating in large herds roaming across vast mountain plateau in southern Norway, and avoiding human activities. Following the industrial revolution, the development of anthropogenic infrastructures has therefore led to the fragmentation of the last remaining wild mountain reindeer population into 23 virtually isolated sub-populations, and has hampered/blocked migration routes used since pre-historic times. Due to the increase in tourism, hydropower and other human activities in mountain areas, fragmentation is rapidly ongoing.

Researchers at the Norwegian institute for Nature Research are remotely collecting data on the movements of ca 300 wild reindeer across the major populations in an attempt to better understand reindeer spatial requirements, the reasons underlying migration, quantify the impact of infrastructure, and aid the process of identifying mitigation measures and re-establishing connectivity among key sub-populations. The pictures taken from the cameras incorporated in some of these collars provide unprecedented and precious information on reproduction, feeding habits and other aspects of reindeer behavior, which would be challenging to obtain in other ways, for such secretive animals living in such a harsh environment.

Check out the slide show here.

DCIM103MEDIA

December 11, 2015

Why We Are Such Suckers for Trophy Photo Outrage

(Photo: It came from Facebook)

My weekly column for Takepart.com:

Lately, I’ve been lurking on the outskirts of a provocative Facebook conversation about hunting. Everybody involved in the debate fit the description “conservationist.” But that was about the only thing they agreed on. (And if I’d stuck around a little longer, they might have gotten ugly about that, too.) The topic of the debate was: “Why have trophy photographs become such a standard object of Internet outrage?”

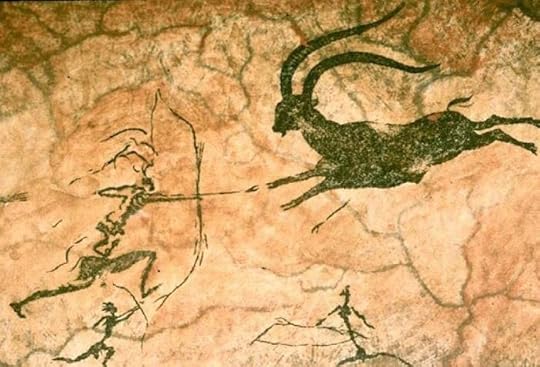

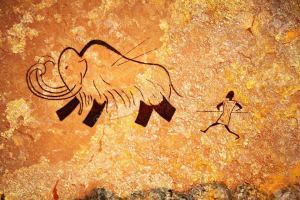

The person who started it all put that question in an intriguing context: The earliest cave paintings almost always depicted hunters pursuing trophy-quality animals—mastodons with great curved tusks and antelope with enormous antlers. The primitive people who painted them were the ancestors of us all, and we would not be here without them or the hunting by which they lived. Their paintings also represent the beginnings of art and human culture. So how can we revere those ancient trophy images and yet also feel such anger toward their modern counterparts?

The person who started it all put that question in an intriguing context: The earliest cave paintings almost always depicted hunters pursuing trophy-quality animals—mastodons with great curved tusks and antelope with enormous antlers. The primitive people who painted them were the ancestors of us all, and we would not be here without them or the hunting by which they lived. Their paintings also represent the beginnings of art and human culture. So how can we revere those ancient trophy images and yet also feel such anger toward their modern counterparts?

The two things are radically different, one writer replied. Scholars generally interpret the hunts in cave paintings as expressions of shamanic or magical links to the quarry. They also served as visual offerings, to solicit future hunting success. By contrast, the writer posted a modern photo of a trophy hippo, its mouth propped open with a stick and the hunter using its carcass as a backrest while reading a newspaper, the perfect image of contempt for his prey.

As happens in almost all such Facebook debates, a personal attack promptly followed: “Do something constructive for the wildlife and wildlands of the world,” instead of “this constant hating and stirring up of emotions.” The writer replied that he had been the driving force behind creating a 32,000-acre marine reserve. So just shut up. A third party stepped in as the voice of reason: “Reality is not binary. People are not always either ‘anti-hunting’ or ‘pro-hunting’.” It depends on context. Then she threw a punch: “Yes, primitive people hunted animals. Many primitive people also killed and ate each other.”

On the hunting side, the main argument was two-fold: “Hunting brings us closer to the realities of ecology, and puts us in touch with a foundational connection to our most remote ancestors in deep time. Even without any conservation or other advantages, it would be a worthy activity.” Hunters were also the original conservationists. One commenter claimed credit to hunters for “preserving millions of acres of wilderness and farmland.”

To me as a non-hunter, both claims seem defensible. Yes, half-wit Russian zillionaires can pop a captive-bred “canned” lion, pose for a trophy photo, and call it hunting. But serious hunters become as deeply knowledgeable as any ecologist about the animals they pursue. Big game hunters like Teddy Roosevelt were also the original conservationists. Certain hunting and fishing nonprofits like the National Wildlife Federation and the Coastal Conservation Association carry on that heritage today. The license and trophy fees hunters and fishermen pay can make a huge contribution to the cost of protecting habitat. Those fees also help win crucial support among local people for maintaining that habitat.

On the anti-trophy photo side, there were people who plainly just hated hunting and hated the taking of an individual life. But this seems to me like choosing to be a vegetarian: It’s pointless trying to impose your beliefs on other people and in any case you’ll get further by good example (and good recipes) than by trying to argue the point.

A better complaint was that hunters don’t do enough to keep out the halfwits or to prevent illegal and irresponsible behavior. Too often, they look the other way when someone they know hunts a threatened or endangered species. They tolerate hunting tournaments that are degrading for everyone involved. Organizations like Safari International also often fail to root out professional guides appearing under their auspices, even when their bad behavior is well known among other hunters.

Hunters need to make clear that conservation is their first priority and any trophy strictly secondary. Just being a hunter isn’t enough. As a group, sportsmen “tend to be politically naïve and easily manipulated by their worst enemies,” the outdoors writer and fishermen Ted Williams has written. “Because he fished and hunted and whooped it up for gun ownership, sportsmen ensured the election of George W. Bush—the most anti-fish-and-wildlife president we’ve ever had with the possible exception of Ronald Reagan, also propelled into office by sportsmen.”

But conservationists and anti-hunting activists need to be doing a lot more for wildlife, too. The thing about those trophy photos is that they do nothing other than allow us to express our outrage. Certain dubious websites even specialize in such images, as easy clickbait. The more tasteless the photo, the better we seem to like it. Expressing our contempt allows us to go away feeling morally superior and environmentally enlightened, even as we drive our gas-guzzling SUVs, live in our McMansions, eat factory-farm meat and otherwise partake in the ruination of the Earth.

So here is my advice: For the hunters, sure, take your pictures. Even smile, if you want. Then print them out the old-fashioned way, on paper. Show them to your family or to sympathetic friends. But please, please, please, skip Facebook, Twitter, or even your local hunting club website. Any place digital is likely to turn your memorable moment into a nightmare.

And for people who just want to protect wildlife? Next time you see one of those photos, look away. Skip the easy outrage. Forget about sharing the image to garner social status for your outrage. Instead, do something that actually makes a difference for wildlife, even if it just means writing a check to one of your favorite conservation groups.

One final point—and I am amazed that in the blizzard of words in the Facebook debate, no one mentioned this. Ancient hunters no doubt prized the animals they killed as precious meat for their families, and thus in some sense as trophies. But in their cave paintings, they always depicted their prey as living, bounding, beautiful creatures. That’s the vision—a world with plenty of wildlife—that all of us should be working toward.

December 4, 2015

How Deadly Power Lines Could Become Great Wildlife Habitat

(Photo: Ken Schulze/Getty Images)

In a lot of peoples’ minds, power transmission lines are the devil, and the idea that a transmission line right-of-way could function as useful wildlife habitat is the devil speaking in tongues. These corridors, an infuriated reader once told me, “have a devastating impact on the environment, kill thousands of birds, cause habitat segmentation, ruin property values, chase people from their homes, have dreadful visual impacts, and significantly reduce wildlife use per acre.”

These are no doubt all important issues to discuss, especially when wind, solar, and hydroelectric projects are increasing the demand for new power line corridors everywhere. And it’s not “thousands of birds.” A 2014 analysis estimated that 25.5 million birds now die every year in the United States from power line collisions and another 5.6 million from electrocutions. These are appalling numbers.

But the other reality is that the United States now has an estimated 9 million acres of land in existing power transmission corridors. That’s largely open space underneath the electric wires, and much of it is in regions where open space is hard to come by. In some cases, it is already becoming the best available habitat for

certain birds, butterflies, native bees, and other pollinators.

In southern New England, where I live, for instance, transmission lines may now be “critically important,” according to Robert Askins, a Connecticut College ornithologist, for brown thrashers, yellow-breasted chats (a state-endangered species), and other birds that require scrubby, relatively open landscapes. That’s partly because their old habitat—19th-century farmland and meadows—has largely vanished, giving way over the past century to suburbs and dense forests.

Likewise, Sam Droege of the United States Geological Survey’s Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland has come to consider power line corridors the best place to hunt for many native bee species. He thinks power line rights-of-way could even become a sort of quasi-public corollary to the national park system, with the added advantage of providing corridors to connect distant wildlife populations that might otherwise become isolated and inbred.

The appeal of these corridors for wildlife depends entirely on how utilities choose to manage them, and that now appears to be changing for the better. It could hardly have gotten worse: For much of the past dozen years, many utilities practiced scorched-earth management, largely because of an August 2003 incident in which power lines sagged into trees, contributing to the largest blackout in North American history.

Federal rules subsequently required utility companies to clear all large trees and other tall vegetation from their transmission corridors or face penalties up to $1 million a day. Many utility executives interpreted that as a mandate to send in the mowers at regular intervals and maintain a grassy monoculture, with spraying of herbicides often added in.

But that approach didn’t do anything to improve the environmental reputation of utilities. (Apart from those 31 million bird deaths every year, think climate change and coal-fired power plants.) It was also expensive. So some utilities gradually stopped mowing and limited herbicide use to spot-spraying on unwanted plants, almost accidentally establishing a shrubby habitat of wildflowers, sedges, ferns, and low shrubs. That’s now called Integrated Vegetation Management, and the result is incidentally ideal for many native birds, insects, and even small mammals.

In 2012, utility companies, together with The Nature Conservancy, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and other organizations, formed the Right of Way Stewardship Council to establish standards and best practices. So far seven power companies have earned accreditation from the council and now manage their power line corridors for low-growth vegetation and thus, incidentally, native wildlife.

Will this approach spread to North America’s several hundred other utilities? “What you have to do is show the utilities that they’re going to save money if they manage versus mowing,” said Rick Johnstone, a former power company land manager who is now an IVM consultant. “You get resistance not only from the contractors who do the mowing but from the foresters in the utilities, because it’s more work to manage,” he said. “I can sit in my office and say it’s time to mow. But when you get into IVM you need to look at it, you need to do the assessment and determine what’s the best practice. What’s the vegetation? What’s the density? Are you near water? And all that takes more expertise.”

Still, utilities that have tried the approach report that the savings can be substantial. In addition to what it does for wildlife, it also brings huge public relations benefits.

But what about all those birds that continue to die by collisions with power lines and by electrocution? A utility group called the Avian Power Line Interaction Committee now works to develop and promote methods to minimize both ways that power lines kill. But APLIC has been at it for a quarter century, and 30 million birds are still dying.

So here’s a bargaining chip for people resisting new power line proposals: Insist that utilities commit to employing IVM methods and bird mortality prevention devices on any new power lines. Or, wait, that’s not quite good enough. Before they move on to new projects, insist that they demonstrate good faith by making their existing power lines benefit wildlife after years of destroying it.

November 27, 2015

“Bitch.” A Poem.

Just belatedly read this in The New Yorker. It’s by Craig Raine, and so good I thought it worth sharing here. Hilarious to see idiots on Twitter denouncing Raine as a misogynist. It’s a poem about a dog, for crissakes.

This Weimaraner in spandex,

tight on the deep chest,

webbed at the tiny waist.

The drips and drabs of her dugs:

ten, a tapering wedge,

narrowed toward the back legs.

Wish I could show you the whole poem here, but click on over to The New Yorker and at least take the time to enjoy it there.

November 25, 2015

For T-Day: Save Yourself from the Digital Zombie Apocalypse

(Photo: Visions of America/UIG via Getty Images)

My latest for Takepart:

The other day I was sitting on a porch on the coast of Maine watching as a red-throated loon hunted underwater. I couldn’t see the bird beneath the surface, but the trail of bubbles it left behind let me follow the action. It shot along for a while in one direction, circled, jinked out to one side, then sent the water boiling in a tight little spot. It surfaced momentarily to gobble down its prize, a small fish, then dove again to hunt some more.

I was lucky to be in that place at that time. And even more so not to have my attention monopolized at that moment by an electronic screen. Lucky, because most of the time I am as bad about this as everybody else. My work as a writer means I often spend eight or 10 hours a day at the keyboard of a laptop. I unwind after dinner with a Netflix show and a beer. When I can’t sleep at night, I browse Facebook or Feedly on a tablet. (Yes, I know, looking at a video screen is like firecrackers for sleep. But it doesn’t stop me.) And when I get up in the morning, the first thing I do is check the time and weather on my smartphone.

The Internet doesn’t just offer endless possibilities; it offers endlessly updating possibilities. It is addictive because of the fear that if we don’t look now, we could be missing something big, something important, something viral.

All the while what we are missing is life. We are missing wildlife and the natural world too.

Even worse,

our kids are missing it. Most adults grew up in an era when the Internet wasn’t such a domineering power in our lives. We can at least vaguely remember when we used to pause to watch a flock of swallows circle or the afternoon light changing on a hillside. But for many children growing up today, digital reality is the only reality.

According to a 2004 survey, American kids then were spending about half as much time outdoors as they did 20 years previously—just 50 minutes a week. That number has almost certainly shrunk as social media have proliferated over the past decade. Arguably, kids also have less reason to go outside. The natural world isn’t there as it was in our own younger days. The earth has lost half its wildlife over the past 40 years, according to the World Wildlife Fund. Birds and butterflies that were common then have vanished, almost without our noticing. This combination of not looking, and having less to look at, means children grow up not caring about the natural world.

So what’s the fix? How do we get away from the virtual and back to what’s real? The first step, as in any addiction program, is to admit how bad the problem has become. According to a 2010 survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation, Americans from ages eight to 18 spend on average more than 7.5 hours a day on electronic devices, including TV viewing, video gaming, social media, and the Web. The numbers are bad enough for white kids and stunningly worse for African American and Hispanic kids, presumably because they tend to live in more urban areas, with fewer accessible green spaces and fewer alternative activities.

The second step is to understand as a society and as parents how bad this is for us all. The list of physical and social maladies associated with sedentary behavior—an almost inevitable corollary of time spent on electronic devices—includes increased risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease, two types of diabetes, and several cancers. For children and adolescents, the risks also include sleep problems, musculoskeletal pain, depression, poor overall psychological health, and minimal face-to-face social skills.

Hence the American Academy of Pediatrics used to recommend that parents limit screen time to less than two hours a day for children over the age of two (and none before then). But it has recently backed away from those strict guidelines, writing off the term “screen time” as “antiquated” and accepting digital reality as the new normal. A recent Australian study came to the same hapless shoulder shrug of a conclusion, as the title made explicit: “Virtually Impossible: limiting Australian children and adolescents daily screen based media use.” It’s impossible, the authors thought, because digital devices have become too embedded in our daily lives, including school and homework activities.

This is nonsense. Kids should be outside for an hour or two every day between school and dinner. That doesn’t mean parents have to drive them someplace. Unorganized playtime is fine. Give them the freedom to find their own games and make up their own rules. Teachers should make a point of giving regular homework assignments in the real world: Describe five trees where you live. Follow a squirrel for 45 minutes, and take field notes on what it’s doing. Count how many birds you can find on your street.

The rest of us need to walk away at regular intervals (and especially at dinner time) from our alluring but soul-sucking lives online. According to a Nielsen report release earlier this year, Americans over 18 average 11 hours a day on electronic media. Given that most of us are awake 16 or 17 hours a day and presumably spend part of our waking hours in school or at work, adults are not providing a great example. Think of it as an addiction because that’s exactly what your Internet suppliers have designed it to be. Facebook, Twitter, and the rest mean to keep us compulsively clicking, in the words of Nir Eyal, web consultant and author of the book Hooked: How to Build Habit-forming Products, so we end up doing so “over and over, in the same basic cycle. Forever and ever.”

Change that: Don’t answer the latest after-hours email from the office. Go outside and breathe for a bit instead. See what turns up. Maybe a red-throated loon is a lot to hope for, but a blue jay will do, or a patch of sunlight on a cloud.

Make shutting down the devices a family thing. Start this Thanksgiving weekend. If you have to watch football on the big day, make it just one game, not the Macy’s parade and then an all-you-can-eat buffet of games. Schedule a hike in a nearby park or preserve instead. Go out and throw a ball around with the kids. REI has set a terrific example by closing its doors on Black Friday, the biggest shopping day of the year, and telling its customers to “opt outside” instead.

Take that advice, and leave the smartphone behind. Then make it a regular thing, for an hour or more every day, to get up and go outside, just to be outside. You may find, after a time, that it is at least as addictive as that next click on an electronic device and far more rewarding.

November 24, 2015

Terrific Video of Siberian Tiger Cubs

This just came in from the Wildlife Conservation Society. It’s camera trap video of rarely seen Amur tigers from Russia’s Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Reserve.

Fewer than 500 of them survive in the wild. But here you can see an adult female trailed by three of her big cubs. I’m using a Twitter link here, so hoping this works:

Your 20 seconds of #catnip: @TheWCS releases super rare footage of #Russian #tiger with THREE cubs. pic.twitter.com/L5JQpdhJtg

— WCS Newsroom (@WCSNewsroom) November 24, 2015

The cats are using an overgrown forest road as a travel corridor; the same type of road patrolled by poachers with spotlights.

WCS is working in this region with Russian collaborators to close old logging roads to protect Amur tigers and their prey. The footage is a sign that these efforts may be working.

November 19, 2015

Leopard Stalks Steenbok at Kruger

Turn off the sound on this one. Too much microphone wind. Or just don’t watch if you are a Friend of Bambi.