Richard Conniff's Blog, page 29

September 11, 2015

The Pygmy Hippo Edges Toward Extinction (But Zoos Can Help)

Pygmy hippo in Cote D’Ivoire

Most people have never heard of pygmy hippos, much less seen one. Until 1844, even scientists did not recognize the existence of this species—a miniaturized, snubbier-nosed (and considerably cuter) 400-pound version of the familiar 3300-pound common hippo. But pygmy hippos are now rapidly disappearing from their West African habitat—and the culprits are entirely familiar.

“Large areas of the original forest habitat, especially in Côte d’Ivoire, have been destroyed or degraded by commercial plantations of oil palm and other products, shifting cultivation, mining and logging, and hunting for bushmeat,” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The IUCN Red List categorizes the species as endangered, with roughly 3000 adult individuals estimated to survive in the wild. Their shrinking and fragmented habitat occurs in just four countries–Liberia, Cote D’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, and Guinea—all prone to political turmoil, corruption, hit-and-run commercial exploitation, and outbreaks of Ebola and other epidemic diseases. A separate subspecies that lived until recently in Nigeria is now apparently extinct.

How to keep the entire pygmy hippo species from suffering the same fate? It depends on both improved protection for their remaining habitat in the wild, and better care of the 367 pygmy hippos in zoos, according to Gabriella Flacke, a wildlife veterinarian and doctoral candidate at the University of Western Australia. But understanding how they live and what they need is extraordinarily difficult. Whereas common hippos are widely distributed, highly visible, and also among the most dangerous large animals in Africa, hardly anyone ever sees a pygmy hippo in the wild.

Flacke and friend.

Pygmy hippos are shy, solitary, and nocturnal, living mainly in forests and swamps. In 2013, Flacke worked in Cote D’Ivoire’s Tai National Park, the largest surviving tropical forest in their home range. But even her collaborators there, Ivoirian researchers who have studied the species for decades, had seen pygmy hippos only once or twice. “You make a lot of noise moving through the forest,” said Flacke, “and by the time you get where the pygmy hippo was, it’s a mile away.“

Flacke had better luck studying footprints and dung, which the pygmy hippo scatters in its wake with a rapid, propeller-like motion of its tail. In addition to the samples collected from the wild, she’s now also analyzing 3500 frozen dung samples (she calls them “hippoopsicles”) from pygmy hippos in zoos. Her ambition is to develop standard methods for remotely monitoring levels of essential hormones like cortisol, testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone. (Remote methods are essential, even in zoos, because of the “difficulty of handling a large, dangerous, and sometimes disagreeable pachyderm.”)

Given that zoos have been keeping pygmy hippos in captivity since 1912, with what seemed to be considerable success, it is remarkable how little science really knows about them. Genetic analysis only recently revealed, for instance, that pygmy and common hippos should be classed not with the suids (or pigs) but with whales and other cetaceans.

Pygmy hippo caught by camera trap (UGA pygmy hippo program/http://pygmyhippo.uga.edu)

Camera trapping in Tai National Park also revealed that pygmy hippos in the wild are far more slender and sleek than their zoo counterparts, which often weigh in at 600 pounds. Writing in the journal Der Zoologische Garten, Flacke and her co-authors argue that zoos misunderstand the dietary needs of these animals and routinely overfeed them. And that can have unexpected consequences, beyond obvious issues like arthritis and foot problems. For instance, zoos have long puzzled over why pygmy hippos routinely produce far more female than male offspring. But a skewed sex ratio may just be an evolved response to favorable feeding conditions.

Zoos also routinely house pygmy hippos in groups, though Flacke and her co-authors write that this practice has at times “resulted in severe injuries and even deaths.” Pygmy hippos are solitary by nature, and even if they sometimes get along living in communal circumstances, it may also inhibit their reproductive physiology and behavior.

In an interview, Flacke said she does not intend any of this as an attack on zoos, but as part of the continual process of improving the care they provide. “A lot of people really hate zoos, and the negative argument against zoos is that they are often like a prison.” But the proposal to simply open the cage doors is just naïve. “They say we should just put all the tigers back in India, and all the orangutans back in Sumatra. But they aren’t going to make it. They were born and raised in captivity, and they don’t have the skill to find food and avoid humans. If it’s a dangerous carnivore, it’s going to go and seek people and say, ‘Oh you’re bringing me my steak.’”

Instead, said Flacke, zoos are essential to preserving species in a rapidly changing world. Like many other natural areas, Tai National Park is under constant threat from gold miners, bushmeat hunters, loggers, and refugees from chaos in neighboring regions. The World Wildlife Fund, which helped instigate the original designation of the Tai forest as a national park in 1972, continues to provide support for park patrols and other conservation work by the Ivoirian authorities. And that work is essential, said Flacke: “If we someday run out of places to put these animals, we’ve sort of screwed ourselves.”

But zoos now sustain about 10 percent of the total pygmy hippo population, and they are essential, too. They provide what Flacke called “a safety net population” in case the species vanishes from the wild. They can also be valuable in keeping their wild counterparts healthy—potentially providing genetic diversity, for instance, to fragmented wild populations.

It’s easy and emotionally gratifying to attack zoos. The harder job is to help make them work better, and not just on behalf of pygmy hippos, but of an entire Noah’s ark of threatened species.

Moth Loves Tobacco, Booze, Good Times

This photo appears in The Guardian‘s selection “This Week in Wildlife” and the caption pretty well says it all:

Nature lovers hope to attract the huge convolvulus hawk-moth to their gardens with tobacco and alcohol. The moths like to feed on the nectar of tobacco plants and wine-soaked ropes

Photograph: Keith Baldie/PA

I think they mean Agrius convolvuli, found at all the best spots from Europe to Australia (sometimes in a state of advanced dissipation).

September 10, 2015

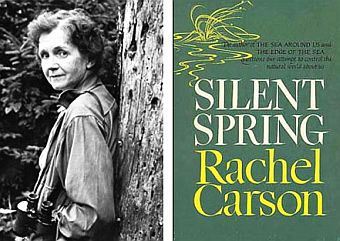

No, Rachel Carson Was Not a Mass Murderer

My latest for Yale Environment 360:

Any time a writer mentions Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring or the subsequent U.S. ban on DDT, the loonies come out of the woodwork. They blame Carson’s book for ending the use of DDT as a mosquito-killing pesticide. And because mosquitoes transmit malaria, that supposedly makes her culpable for just about every malaria death of the past half century.

The Competitive Enterprise Institute, a libertarian think tank, devotes an entire website to the notion that “Rachel was wrong,” asserting that “millions of people around the world suffer the painful and often deadly effects of malaria because one person sounded a false alarm.” Likewise former U.S. Senator Tom Coburn has declared that “millions of people, particularly children under five, died because governments bought into Carson’s junk science claims about DDT.” The novelist Michael Crichton even had one of his fictional characters assert that “Banning DDT killed more people than Hitler.” He put the death toll at 50 million.

It’s worth considering the many errors in this argument both because malaria remains an epidemic problem in much of the developing world and also because groups like the Competitive Enterprise Institute, backed by corporate interests, have latched onto DDT as a case study for undermining all environmental regulation.

It’s worth considering the many errors in this argument both because malaria remains an epidemic problem in much of the developing world and also because groups like the Competitive Enterprise Institute, backed by corporate interests, have latched onto DDT as a case study for undermining all environmental regulation.

The first thing worth remembering is that it wasn’t Rachel Carson who banned DDT. It was the very Republican Nixon Administration, in 1972. Moreover, the ban applied only in the United States, and even there it made an exception for public health uses. The ban was intended to prevent the imminent extinction of ospreys, peregrine falcons, and bald eagles, our national bird, among other species; they were vulnerable because DDT caused a fatal thinning of eggshells, which collapsed under the weight of the parent incubating them. But the ban did nothing to stop the manufacture or export of DDT. William Ruckelshaus, administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, explicitly declared that his agency would not (indeed could not) “presume to regulate the felt necessities of other countries.”

So what actually happened with DDT? And why is malaria, which seemed to be en route to eradication in the 1950s, still killing 584,000 people a year? A team of public health researchers made a systematic review in 2012, in the Malaria Journal, of where and why resurgence of malaria has occurred in countries around the world. That study made no mention of Rachel Carson, focusing instead on the fickle nature of human commitment to public health.

In the 75 cases they examined, the researchers found that mosquito and malaria control programs failed 49 percent of the time for lack of funding. And the funding mostly stopped because of complacency and poor execution, or because of wars or disasters, or because of deliberate decisions to stop the program. In India, for instance, DDT helped reduce malaria incidence from 100 million cases to 100,000 cases by 1965. Then USAID handed off funding to the government of India, which failed to follow through adequately, causing malaria incidence to surge to six million cases in 1976.

“In several cases,” the researchers found, “donors appear to have reallocated funding specifically because successful reductions in malaria burden had occurred.” It was the same kind of complacency that’s common today among misinformed American parents who refuse to vaccinate their kids—and then watch children die from underrated diseases like measles or whooping cough. Even the World Health Organization (WHO) got it wrong, deciding in the late 1950s to cut funding and reduce staff for its anti-malaria program in Swaziland because malaria no longer seemed like much of a problem. Epidemics soon followed.

People also lost trust in DDT for a much more fundamental reason, though, as journalist Aaron Swartz put it, it’s “not one conservatives are particularly fond of: evolution.” Mosquitoes can produce multiple generations over the course of a year. Any pesticide will wipe out the vulnerable ones — and the ones that happen to be resistant because of some quirk in their biology or behavior rapidly take their place and proliferate. Thus DDT was already becoming ineffective in the early 1950s, so much so that in 1960, two years before Carson’s book, The New York Times headlined an article “Malaria Battle in Doubt; Warning Voiced That Carrier of Disease Could Outwit World’s Scientific Skills.”

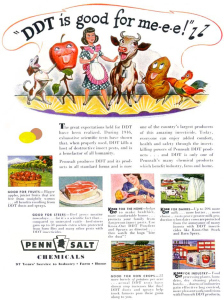

If conservatives genuinely wanted to get at the reasons malaria eradication failed, they should be targeting the government agencies and pesticide manufacturers (among them Monsanto and Ciba, now part of BASF) who destroyed the effectiveness of DDT by promoting its massive overuse. Incredibly, the United States used 80 million pounds of DDT in 1959, much of it sprayed in a dense fog across forests and farm fields. All Rachel Carson did was to raise legitimate questions about the environmental and health dangers of this completely untested DDT abuse.

If conservatives genuinely wanted to get at the reasons malaria eradication failed, they should be targeting the government agencies and pesticide manufacturers (among them Monsanto and Ciba, now part of BASF) who destroyed the effectiveness of DDT by promoting its massive overuse. Incredibly, the United States used 80 million pounds of DDT in 1959, much of it sprayed in a dense fog across forests and farm fields. All Rachel Carson did was to raise legitimate questions about the environmental and health dangers of this completely untested DDT abuse.

The war against malaria still goes on today, employing a rotation among a battery of different pesticides to hold off resistance. But all the current pesticides have problems of cost, effectiveness, or safety. Despite the assertion that Rachel Carson killed it off, DDT continues to be used in many countries, generally to spray on the interior walls of houses. (Even then, the protocol is to use DDT only after the mosquitoes have developed resistance to mosquito netting infused with pyrethroid pesticides, a more effective treatment.)

Despite the argument that Carson killed U.S. funding, our tax dollars still support this use of DDT through blanket grants that allow foreign nations to use any pesticide approved by the World Health Organization. But DDT is finally on the way out (a Chinese company is the only remaining manufacturer), and anti-malaria programs now live in the hope that an effective vaccine, a miracle drug, or new pesticides will consign the whole debate to history.

One final point: Carson’s critics like to assert that she exaggerated or even lied about the human health hazards of DDT. They argue, as a Crichton character declared, that it was “so safe you could eat it.” You will not, however, find Carson’s critics actually eating DDT to make their case. That’s apparently for people in the developing world, who ingest it when it flakes off their walls or ceilings. Babies ingest the accumulated load of DDT when they nurse at their mothers’ breasts. And yet studies increasingly link exposure to DDT to high blood pressure, Alzheimer’s disease, reproductive disorders, and a variety of other conditions, even two or three generations after exposure.

This increasingly leaves anti-malaria workers in the awkward position of “putting DDT in the mouths of babies through the mother’s milk,” said Graham White, a British specialist in tropical diseases and pesticides. They continue to rely on DDT because it may be the only way to prevent children from dying now. But they do so in the knowledge that it may seriously compromise their lives forever after.

Rachel Carson foresaw these hazards more than 50 years ago, at a time when no one else gave much thought to the environmental consequences of our miracle products, said Clive Shiff, a lifelong specialist in malaria and other tropical diseases at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. No one then thought much about bioaccumulation of chemicals, and no one imagined the idea of multigenerational epigenetic effects. Moreover, Shiff noted, she spoke out though all the powers of government, business, and science were lined up against her. “Rachel Carson was legitimately heroic,” he added. “You can say that loudly.”

The bottom line, sadly, is that Rachel was right.

September 6, 2015

Killing Dinner with Your Own Hands

I’ve only done it with fish and lobster, but according to today’s New York Times, killing your own dinner is now a foodist movement. Here’s the lead of the story by Kate Murphy:

COULD you look through a rifle’s scope into the long-lashed eyes of an elk and pull the trigger if it would be the only meat you ate for the year? Would your conscience be more or less troubled if instead you slit the necks of animals you planned to eat after they were nurtured like adored pets on an idyllic farm?

Does the thought of doing either send you to the grocery store or farmers’ market, where neat packages conceal the violence committed on your behalf? Or do you forswear meat altogether?

While the morality of our meals is not a new debate, the polemics have reached a shrill intensity lately as a growing number of people, in an effort to raise their culinary consciousness, have committed to eating only meat they kill themselves. They are unapologetic, although not necessarily unflinching, about the blood on their hands. And they are the latest dietary tribe in our increasingly Balkanized food culture where people align with those who consume as they do and question the emotional, spiritual and intellectual capacities of those who don’t.

Read the whole article here. But I particularly like this bit. It is so gratifying to have deep thinkers to sort out the moral implications of what we eat:

Nor can you treat all meat eaters as savages, said Mr. Sarnecki, who writes and teaches on food ethics. “It might not be morally problematic to eat lobsters because they likely don’t conceptualize the world at all, whereas you might feel differently if the animal were a mammal that probably has a higher level of consciousness,” he said, duly noting, “I draw the line at lobsters because they are delicious.”

Killing Dinner with you Own Hands

I’ve only done it with fish and lobster, but according to today’s New York Times, killing your own dinner is now a foodist movement. Here’s the lead of the story by Kate Murphy:

COULD you look through a rifle’s scope into the long-lashed eyes of an elk and pull the trigger if it would be the only meat you ate for the year? Would your conscience be more or less troubled if instead you slit the necks of animals you planned to eat after they were nurtured like adored pets on an idyllic farm?

Does the thought of doing either send you to the grocery store or farmers’ market, where neat packages conceal the violence committed on your behalf? Or do you forswear meat altogether?

While the morality of our meals is not a new debate, the polemics have reached a shrill intensity lately as a growing number of people, in an effort to raise their culinary consciousness, have committed to eating only meat they kill themselves. They are unapologetic, although not necessarily unflinching, about the blood on their hands. And they are the latest dietary tribe in our increasingly Balkanized food culture where people align with those who consume as they do and question the emotional, spiritual and intellectual capacities of those who don’t.

Read the whole article here. But I particularly like this bit. It is so gratifying to have deep thinkers to sort out the moral implications of what we eat:

Nor can you treat all meat eaters as savages, said Mr. Sarnecki, who writes and teaches on food ethics. “It might not be morally problematic to eat lobsters because they likely don’t conceptualize the world at all, whereas you might feel differently if the animal were a mammal that probably has a higher level of consciousness,” he said, duly noting, “I draw the line at lobsters because they are delicious.”

September 4, 2015

Do We Really Need “Hypoallergenic Parks”?

Granada, Spain. (Photo:Patricia Hamilton/Getty Images )

“Hypoallergenic parks: Coming soon?” That was the headline on the press release, and the specter of sanitized nature made me mutter “Oh, crap.” So I downloaded the study. It’s being published in the Journal of Environmental Quality, and it made me wonder, for the first time in my life, whether we might be taking this whole damned environmental quality thing a bridge too far.

Let’s stipulate that we have already paved under much of the natural world to suit human needs, especially in and around cities, and further, that we often manipulate what’s left to our own purposes, and finally, that these changes almost always work to the detriment of the birds, butterflies, and other animals that once depended on these habitats. Is the logical conclusion that we now also need a war on trees that happen to cause hay fever?

The study, by a team of Spanish researchers, looked at trees in Granada, a city widely admired for its abundance of handsomely-planted boulevards, parks, gardens, and other green spaces. But because of its Mediterranean climate and long growing season, Granada is also a hay fever hotspot, with almost 30 percent of residents saying they are allergic to pollen.

The researchers found that a third of the city’s trees rated high or very high for allergenicity—the potential to elicit allergic reactions. Ranking near the top of the list were oaks, olive trees, and the tall cypresses that have deep cultural roots in the city’s rich Arab past. The seasonal sneeze-inducing potential of different neighborhoods varied from “breathe easy” in Zaidín Park, where the last vestiges of greenery seem to consist mainly of grass, on up to “your head will explode” in Bosque de Gomérez, a forest on the outskirts of the city.

It sounded like a prescription for clear-cutting, possibly by an army of hay fever-suffering vigilantes sneezing loud enough to drown out the roar of their chainsaws. So I tried the study on a couple of U.S. specialists in urban forests to see if they agreed. “As a sufferer of seasonal allergies to oak pollen,” Paige Warren of the University of Massachusetts wrote back, “I have to say I sympathize with the authors’ concern over allergens and human health.”

But there are tradeoffs, she added, and navigating these tradeoffs means asking questions like: “How much does reducing allergen exposure from tree pollen benefit human health relative to: other kinds of allergens (like ragweed), and other air quality issues (like fine particulates and other pollution)?” It should also never be just about us—so how much does the mix of tree species in city plantings matter to biodiversity—those birds and butterflies?

Douglas W. Tallamy agreed. He’s a University of Delaware entomologist and author of Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife With Native Plants. He also once published a list ranking U.S. woody plant species by their wildlife value, with oaks at the top because they provide habitat for 557 species of caterpillar, a favorite bird food.

“If you are going to rank trees for urban use (and I am all for that),” Tallamy replied, “don’t just use one criterion: rank them for all of their ecosystem services. Oaks are best for biodiversity. They are best for carbon sequestration. They are best for watershed management. Do we really want to throw all of that out because they are allergenic for three weeks of the year?”

Tallamy also noticed something intriguing about the new study’s list of sneeze-inducing trees: Many of them are not native to the region. Chinese arborvitae comes, no surprise, from East Asia. The Port Orford cedar is native to Oregon and California.

Paloma Cariñanos, a botanist at the University of Granada and lead author of the new study, noted that the list of nonnative problem trees also includes Casuarina, eucalyptus, ginkgo, and ailanthus (all commonly planted in U.S. cities, too). But she pointed out that the allergy season in Granada can run for six months, not three weeks, and is likely to become a bigger health issue worldwide because of the warming climate.

The study does not envision wholesale tree removal, she said. But if all trees along a road are of the same species, and it’s a problem species, “We propose to modify this design by replacing one of every three trees with a tree of another species.” That would preserve some of the existing habitat for wildlife, and might even increase biodiversity by adding a different kind of habitat. The plan would also replace trees that die, using a database categorizing 7,000 species by their biological, morphological, ecological, landscaping, and allergenic characteristics.

That is, it’s a tradeoff. The only problem with the study is that it doesn’t state this balance of considerations loudly enough. And that’s a problem because hay fever sufferers caught up in their misery are liable to take away the wrong message. It’s also a case of a press release writer gone amuck, this time from the American Society of Agronomy. That term “hypoallergenic parks” never turns up in Cariñanos’s study.

The bottom line is that we need to protect urban tree cover, which is declining at a rate of four million trees a year in the United States. And the rage for “million tree” planting campaigns is not by itself the answer. We need scientists to think carefully about the mix of trees being planted and include wildlife prominently in their consideration of pros and cons.

Finally, if your community still thinks planting gingkos, eucalyptus, and other introduced species is a smart idea, you need to step up and sneeze in the face of local officials. Make it loud, sloppy one.

The birds and butterflies (and hay fever sufferers) are counting on you.

September 3, 2015

Survivalist Art Show on Wings

Yes, she/he is winking at your coyly. (New species Automeris amanda. Saturnidae)

A new geometrid moth

Xylophanes amadis

Oospila albicoma matura

Here’s the press release from the Wildlife Conservation Society:

WCS has released a stunning gallery of images of some of the moths uncovered by the groundbreaking Bolivian scientific expedition, Identidad Madidi. A staggering 10,000 species of moths may live in Madidi National Park – considered the most biodiverse protected area on the planet. The moths were found in the montane savannas and gallery forests of the Apolo region.

The expedition’s entomologist, Fernando Guerra Serrudo, Associate Researcher of the Bolivian Faunal Collection and the Institute of Ecology, said of Madidi’s moths: “Moths are often very beautiful and present a diversity of shapes and patterns. In Bolivia, several species are known locally as ‘taparaku’ and feared because of the belief that when they are found in a house they indicate that someone in that home will die. In most cases the adults of these species do not feed and have very poorly developed mandibles. The whole purpose of their life is to reproduce.”

Identidad Madidi is a multi-institutional effort to describe still unknown species and to showcase the wonders of Bolivia’s extraordinary natural heritage at home and abroad. The expedition officially began on June 5th, 2015 and will eventually visit 14 sites lasting for 18 months as a team of Bolivian scientists works to expand existing knowledge on Madidi’s birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and fish along an altitudinal pathway descending more than 5,000 meters (more than 16,000 feet) from the mountains of the high Andes into the tropical Amazonian forests and grasslands of northern Bolivia.

The first leg of the expedition, which concluded last month, uncovered a new frog, three probable new catfish, and a new lizard. The expedition currently underway is exploring three sites in the High Andes of Madidi, specifically within the Puina valley between 3,750 meters and 5,250 meters above sea level in Yungas paramo grasslands, Polylepis forests and high mountain puna vegetation.

Participating institutions in Identidad Madidi include the Ministry of the Environment and Water, the Bolivian National Park Service, the Vice Ministry of Science and Technology, Madidi National Park, the Bolivian Biodiversity Network, WCS, the Institute of Ecology, Bolivian National Herbarium, Bolivian Faunal Collection and Armonia with funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and WCS.

You can follow the expedition online at www.identidadmadidi.org, #IDMadidi.”

August 23, 2015

The Birds of Summer

(Photo: Roger Phillips/Idaho Statesman, via Associated Press)

My latest for The New York Times:

THE other morning, as I sat on the porch having my coffee, an osprey came plummeting down toward me out of a smoky, overcast sky, with a fish caught in his talons. He was screeching, “See, see, seeeee!” over and over. I suppose there must have been another osprey in the neighborhood. The males can be shameless at showing off their catch, but it’s mainly for other birds, not me.

“Stick around and eat,” I cried up at him. “Plenty of room, water views. Excellent neighbors.” He went winging away instead to some other, more osprey-perfect place, leaving me muttering, “Fussy bastards,” into my coffee cup.

I am a frustrated landlord. A few years ago, local volunteers put up an osprey nesting platform — basically half a sheet of plywood atop a 10-foot-high post — in the small salt marsh behind my house. In the three breeding seasons since then, young ospreys have flirted with the platform, and even piled up sticks there, the tentative beginnings of long-term residence. One time, a male and female perched together there, sizing each other up and apparently arguing about whether this might be their dream house. But they did not spend the night. Hence I suffer from empty nest syndrome of a very literal sort.

Not all that long ago, the ambition of having ospreys nesting in the backyard would have been ridiculous. There simply weren’t any. Around the mouth of the Connecticut River, where I live, only a single nest survived in the early 1970s, producing a total of just two chicks — down from a previously stable population of 200 active osprey nests. From New York to Boston, a population of more than 800 nests tumbled down to double digits, with devastating declines also taking place elsewhere on both coasts, and on other continents.

Researchers set up a death watch in the Connecticut River estuary. But they also worked with other scientists to identify the immediate cause of this decline — eggshells so thin they collapsed under the weight of the parent trying to incubate them. When conclusive evidence showed that the culprit was the pesticide DDT, activists sued, and in 1972 the Environmental Protection Agency imposed a nationwide ban.

A Lazarus story followed. Ospreys not only came back from the dead, but their reproduction also began to surge in 1976 and continues to do so. You can now find ospreys almost anywhere along United States coastal waterways and in the Mississippi River valley, nesting on channel markers, docks, bridges, water towers and even amusement-park lampposts. They arrive with the spring and stay till Labor Day, and you need only wade past the crowd of their admirers to see them. Ospreys have become everybody’s favorite birds of summer.

It is easy to see why this might be so: Ospreys are big and fiercely beautiful, show up in highly visible locations, and engage in spectacular behaviors. They are also site- and mate-faithful, or at least faithful enough for us to imagine they are monogamous. So people get to know their local couple, and wait for the male to return first from his South American retreat, with the female arriving from her separate wintering grounds soon after. And then the osprey drama of hatching, rearing and fledging their young unfolds, just when we happen to be on vacation and with the leisure to watch.

An osprey on the hunt circles over open water, hovers with a characteristic fluttering, decides this isn’t quite the spot, circles and hovers some more, and finally plunges feet-first into the water. It may struggle to become airborne again, with a fish up to 14 inches long mortally pierced between its talons. The bird then heads back to the nest with its unwilling passenger slung underneath. The fish travels headforemost, silvery and slim, and often with what the poet Mary Oliver called “a scrim of red rubies on its flashing sides.”

Ospreys are wild, and yet we garden them. Artificial platforms, introduced in the 1960s, are now everywhere, in marshes and waterways, providing stable nesting sites, protection from climbing predators like raccoons, and a reassuring distance from the trees where nest-raiding great horned owls lurk. On Cape Cod, a bird-loving retired lawyer named Donald Henderson noticed a neighbor repeatedly evicting a pair of ospreys from atop his chimney. So he brought in a backhoe to install a telephone pole with a platform on top. The ospreys were circling for a landing literally as the construction crew backed away from their work. Now he files annual reports up to 28 pages long on doings at the nest (“Female very insistent — screamed and screamed — if male did not keep the fish coming regularly.”)

On Great Island, at the mouth of the Connecticut River, there are now 28 platforms, and when I visited recently with the longtime osprey advocate Paul Spitzer, he said ospreys everywhere had responded enthusiastically to the platforms by moving en masse off the mainland and out onto the water. The traffic overhead reminded me of a wartime air base, with ospreys winging in from all directions with their cargo (those fish) and back out again for more.

Maybe the platforms partly explain our inordinate love for ospreys, because they give us the gratifying sense of doing something to save them. Or maybe the platforms just provide a theatrical stage for us to follow the drama of their lives. In any case, the futures of their species and ours are now thoroughly intertwined.

For myself, I also love ospreys because they give me a chance to remind the Republicans who generally own seaside real estate (and covet ospreys) that these birds are a living instance of how well government regulation can work. We saved ospreys not just through laws regulating pesticides and protecting migratory birds, but also through the Clean Water Act of 1972, which turned the Connecticut River, and many others, from an open cesspool to a precious natural and recreational resource. A regional decision that minimizes the catch in Long Island Sound for menhaden–a forage fish popular with ospreys but being fished to oblivion elsewhere–has also helped.

But let’s not talk politics. The summer is running away from us, and the fledglings are now out of the nest and slowly mastering their parents’ art of fishing. Go down to the water and watch. They are the best show of this and many future summers.

August 21, 2015

Slowing Africa’s Population Boom to Save People and Wildlife Both

Lagos, Nigeria. (Photo: George Esiri/Reuters)

Ask any serious conservationist to name the most pressing issues today for African wildlife, and right at the top of the list, you’ll almost certainly hear about the wholesale killing of wildlife for the bushmeat trade, or the slaughter of 33,000 elephants a year to make ivory trinkets.

But the truth is that these are symptoms. And if they sound hard to fix, take a look at the much larger underlying problem, the one nobody wants to talk about: Human populations in some of most revered habitats on Earth—notably including Kenya and Tanzania—are on track to quadruple or even quintuple in this century. Nigeria, already almost ungovernable with 160 million people in an area the size of France, will grow to just under a billion people over the next 85 years.

Across sub-Saharan Africa, according to the latest United Nations forecast, the population will rise from 960 million today to almost four billion by 2100. Population density will match that of modern China. That’s bad news for human populations and but catastrophic for wildlife.

So what can we do to slow that rate of growth? How do we reduce the likelihood of an Africa with not much room for people—and none for wildlife? The answers come down to four basic steps, and they aren’t necessarily the ones you might expect.

The first step, said Adrian Raftery, a University of Washington population expert who contributed to the UN forecasts, is to persuade governments and societies about the good news of the “demographic dividend.” It’s stunningly simple: One of the fastest ways to improve a national economy is to encourage a rapid drop in the birthrate. That translates almost immediately into fewer dependents for the working age population—meaning families and societies don’t have to spend as much on school fees, clothes, healthcare, and other childrearing expenses.

But this dividend also pays off long-term if a country takes some of that freed-up wealth and uses it to invest in infrastructure for further education. That’s because it’s easier to build a prosperous economy on a more educated upcoming generation. It’s also easier to build better security for a family, said Raftery: “One reason people have six kids is so there will be someone to support them in their old age. But if you have four kids, and two of them get white-collar jobs, you are going to be more secure than with six field workers.”

The demographic dividend is already paying off for Ireland, Thailand, India, and Brazil, among other nations, and it’s starting to be talked about among African academics and bureaucrats. “The important component they’re not talking about so much is that massive investments in education is necessary,” said Raftery. “You have to invest in people, they have to be prepared to have jobs, and the jobs have to be available.”

Second, improving educational opportunities for girls leads to lower fertility short-term. That’s because having more of their kids go to school and stay there longer, said Raftery, “re-orients” the thinking of their parents. “Instead of trying to have more children, they begin to invest more in the children they have.” Long term, those better-educated girls grow up to get better jobs, and see wider opportunities for themselves beyond raising six kids. They are also better prepared to find and use family planning information. And yet in Nigeria today, more than a quarter of all girls do not even complete elementary school.

Some African nations have begun to invest more heavily in education, said Raftery. But because their populations are growing so fast, they can wind up “paying more to stand still.” UNICEF, CARE, and Let Girls Lead all have programs aimed at educating girls in sub-Saharan Africa—and accept donations.

Third, contraceptives and family planning programs need to be more widely available. “Something like a quarter of women in sub-Saharan Africa who are in a relationship–and don’t want to have more children–are not choosing contraception,” said Raftery, “partly because of difficulty of access, and also because of concerns about health and about side-effects, or sometimes because their partner might not agree.”

So why isn’t better family planning access at the top of the population to-do list? The fertility rate in sub-Saharan Africa now is about five children per woman, said Raftery. But the desired fertility rate is only slightly lower at 4.5. Getting down to the replacement rate of 2.3 births per woman requires something much bigger than contraception–the profound shift in expectations that comes only with better education and wider opportunities. Even so, donations can help. The International Planned Parenthood Federation is one group working to reach the 220 million women in the developing world “want contraception but can’t get it.”

The fourth step is probably the hardest one: We need to consume less of almost everything. For starters, everybody should know by now that bringing ivory trinkets home from your trip to Hong Kong makes you complicit in the slaughter of elephants. (And yet, U.S. travelers are still a major market for ivory.) Beyond that, we need to take fewer trips, burn less fuel, waste less food, live in smaller houses, and focus more on the people, places, and experiences close to home. The world cannot afford the grandiose “American way of life” even now. But if we make it a model for the coming world of 11 billion people—all of them desperately hoping to become upwardly mobile–it will be the death of wildlife everywhere, and ultimately of us, too.

.

August 14, 2015

CSI (and a Poison Pill) for Cats that Kill

One of Australia’s 15 million feral cats at work on a native marsupial, the phascogale

Domestic cats have become notorious in recent years as one of the most destructive invasive species on the planet, now threatening dozens of bird and mammal species with extinction. (That’s on top of the 30 or so species they have already eradicated.) When conservationists are trying to restore a threatened species to its old habitats, a single murderous cat can be enough to destroy the entire project.

Now frustrated scientists in Australia are proposing to apply criminal forensics and even a poison pill to identify and eliminate problem cats—and possibly spare other cats that are innocent of the killing. In a new study in the journal Biological Conservation, they call these experimental techniques “predator profiling.”

A team of researchers led by ecologist Katherine Moseby at the University of Adelaide looked at restoration attempts for what they call “challenging species.” That generally means mammals that are big enough, toothy enough, or just plain mean enough that you might not think the average outdoor cat would pose a threat. Many of these species—the western quoll, the burrowing bettong, the rufous hare-wallaby—are largely unfamiliar outside Australia, and that’s the point. They are endemic species found nowhere else in the world and an essential part of Australia’s natural heritage. Cats, introduced to Australia about 200 years ago, aren’t—and they have proved capable of killing native animals weighing as much as 12 pounds.

The cats have become a nightmare for restoration biologists. In one reintroduction attempt, 13 of 31 rufous hare-wallabies quickly vanished, and feral cats seemed to be the culprit. The researchers trapped and

A bettong

euthanized a single 11.2-pound cat, and the killing stopped. The same thing happened in a brush-tailed bettong reintroduction, with the radio collars of 14 animals—a fifth of the total—giving out the “dead” signal one by one over a period of four months. Eliminating a single 12.6-pound cat ended the problem.

For their study, Moseby and her colleagues looked at an attempt to reintroduce 41 western quolls—a predatory marsupial once common throughout Australia—into Flinders Ranges National Park. They retrieved the 11 animals that died and, among other forensic techniques, took swabs of the saliva on the radio collar and on the carcass for matching with samples from captured cats. In one typical case, a professional shooter killed a large male cat near a quoll kill site, and not only was its DNA identical to that found on the dead quoll, but its teeth matched the bite marks on the victim, and it had quoll fur in its stomach.

The problem for challenging species reintroductions, said Moseby in an interview, is that certain cats—generally large males—learn to deal with the challenges and then specialize in that prey, coming back again and again. Ducks aren’t exactly challenging, but swimming usually is for cats. Yet in one notorious case, a cat was shot while swimming out to gray teal nests—and it had gray teal in its stomach. It was a serial killer. Moseby likened the proposed response to the way society generally deals with other “problem predators”: The conventional practice is not to eliminate all tigers or polar bears, say, but to target only individuals that have become a menace to humans.

In the case of cats, attempting to eradicate the entire free-roaming population isn’t generally practical, except on small islands. It can be more efficient, said Moseby, to identify and eliminate just the problem felines. Or, because DNA and other forensic techniques are still relatively expensive, it may require eliminating the type of cats, those large males that are prone to causing problems for challenging prey. That can mean setting large box traps or using auditory signals to target those cats. “We’re trying to show that not all cats are created equal,” said Moseby. “Only a proportion of the animals are doing the damage.”

But aren’t some cat owners going to interpret that to mean their cat is innocent and should be free to roam outdoors? “I can see that there’s a potential for that,” she acknowledged. “But we’re only talking about challenging species—prey species that are larger, more aggressive, and have defensive mechanisms. Whereas for things like native lizards or native mice, they might be vulnerable to any cat.” That’s why Australia recently launched a “war on cats,” with a plan to cull 2 million feral cats over the next five years. Environment Minister Greg Hunt described the program as an attempt to “halt and reverse the threats to our magnificent endemic species.” (In New Zealand, where cats have also devastated endemic species, an economist has proposed a ban on all domestic cats.)

But cats are unlikely to go away anytime soon. So Moseby is working on one initiative to make native species more cat-savvy. Researchers now have 450 burrowing bettongs, small marsupials, in a nine-square-mile fenced paddock with two cats. The aim is to fast-track evolution and over a few generations breed up populations that can survive even with cats in the area. “We don’t want to be building fences forever and excluding these animals [the cats] completely,” she said. That just encourages prey animals to become more naive about predators.

Another more radical initiative in the works at the University of Adelaide would automatically target and kill problem cats at the scene of the crime: Researchers are developing “toxic microchips,” said Moseby, that could turn a prey animal into “a toxic Trojan horse.” The chip, implanted in an animal’s skin, would not harm the carrier. It uses a local plant toxin to which indigenous species have adapted but introduced species haven’t. The chip is designed to break open during the shredding and rending of a predator attack and thus poison the killer—specifically a cat or other introduced species.

That may sound like cruel and unusual punishment to cat lovers. But if their cats are really as innocent as they like to say, they won’t encounter the problem in the first place.