Richard Conniff's Blog, page 32

March 29, 2015

The Best Hope for Ethiopia’s Wildlife Is From the Barrel of a Gun

Ethiopia’s mountain nyala. (Photo: Gabrielle and Michel Therin-Weise/Getty Images)

Over the past quarter century, Ethiopia has lost 90 percent of its elephants. Of its other large mammals, at least six species���the black rhinoceros, the African wild ass, the Ethiopian wolf, the mountain nyala, the Walia ibex, and the Gr��vy���s zebra���are slinking toward oblivion. Could trophy hunting be one way to turn this grim decline around? That is, could killing endangered animals help to save them? That���s what a new study, published earlier this month in the journal Conservation Biology,��suggests.

Let���s acknowledge up front that big game hunting, especially in Africa, arouses strong emotions. When Melissa Bachman, host of a hunting show on cable television, grinned for the camera a few years ago beside a lion she had just killed, the photo didn���t just go viral: It also garnered nearly 500,000 signatures on a petition to ban her from South Africa. When Namibia auctioned off the right to shoot a trophy black rhino last year, the winning bidder harvested a boatload of death threats.

But for many African countries, big game hunts generate millions of dollars in revenue every year, both from trophy fees and from the money hunters spend on their multi-week trips. ���Hunters spend 10 to 25 times more than

regular tourists,��� Alexander Songorwa, director of wildlife for the Tanzanian Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, wrote in a 2013 New York Times op-ed.

He was arguing against a proposal that the United States Fish and Wildlife Service list the lion as an endangered species, which would have effectively ended trophy hunting. ���The millions of dollars that hunters spend to go on safari here each year,��� he said, ���help finance the game reserves, wildlife management areas and conservation efforts in our rapidly growing country.���

Trophy hunting revenue in Ethiopia amounts to only about $1 million to $2 million a year, nothing like the cash generated in South Africa, Namibia, Tanzania, and other countries. Even so, that revenue ���plays a substantial role in rural economies��� near Ethiopia���s 40 or so controlled hunting areas, according to the new study, and that can lead to greater protection of wildlife areas.

When some of that revenue gets properly distributed to provide jobs, schools, water wells, and other community benefits, it gives people an incentive to leave wild areas more or less intact. Otherwise, land is rapidly being swallowed up for agriculture and other human needs. The new study suggests that big game hunters are not only aware of the close connection between protecting wildlife habitat and supporting local communities but also willing to pay thousands of dollars extra to strengthen that connection.

For the study, Anke Fischer, of the James Hutton Institute in Scotland, and her coauthors surveyed 224 big game hunters, most of them with experience hunting in Africa. The goal was to understand what they value in a hunting area and what might encourage them to come to Ethiopia. The survey calculated these attitudes in terms of what it called WTP: ���willingness to pay.��� The hunters said, on average, that they would pay up to $3,900 more if they could be assured that 10 percent of their total hunting fees would go to local communities���and $2,000 less if that share ended up with the central government. Hunting in areas where domestic livestock was also grazing reduced the value of the trip by $2,000 on average.�� The potential to see lots of wildlife, including non���target species, caused a spike in WTP.

���Many prospective hunters were worried about the future of wildlife in Ethiopia,��� the study concluded, ���and would like trophy hunting to further conservation aims.��� Fischer, who is not a hunter, said she was struck by the ���passion for wildlife conservation��� shown by the hunters in their comments and responses. ���Ethiopia is a strikingly beautiful country with great potential but dwindling wildlife resources,��� one hunter remarked.

Can attitudes expressed in a survey make any real difference on the ground? Consider, for instance, the mountain nyala, an antelope with huge, elegantly curving horns and double white stripes on its face. The Ethiopian government issues up to 40 permits a year to kill these endangered animals, which are found nowhere else in the world. The trophy fee is $15,000 per animal. A photo of a trophy hunter posing beside the corpse of such an animal is an easy target for environmental outrage.

But the major threat to survival of the mountain nyala comes from habitat loss due to agriculture and livestock overgrazing, more than from hunting, said Nils Bunnefeld, a conservation scientist at Scotland���s University of Stirling, who has studied the nyala but was not involved in the recent research. ���If these pressures on the population can be removed,��� by increased protection of controlled hunting areas, for example, ���the population can increase,��� he said, allowing for the sustainable hunting of some nyala. But it���s essential to monitor wildlife populations to ensure that hunting quotas are set at the correct levels.

Sharing revenue fairly also matters, said Fischer. ���Any land that you can���t use for agriculture, because it���s being used for hunting, is land that doesn���t benefit the local population at that moment,��� she said. The only way to reduce resentment and ensure acceptance of that set-aside is for the local community to get a share of hunting revenue, and for that share to be distributed in ways that make a visible difference to people���s lives.

The unspoken driver in this dynamic is human population growth. Ethiopia now has 97 million people, up from 89 million in 2011. The national government has recognized that it cannot sustain that growth rate, and new programs have dramatically increased contraceptive use. Meanwhile, the only hope for protecting wildlife is to make it valuable to this growing human community. You may not like trophy hunting, but it is the fastest way to accomplish that. As one hunter put it in his survey response, developing and properly managing the hunting industry now ���represents the best and perhaps last chance for Ethiopian wildlife.���

March 26, 2015

Finding 30 New Species in Los Angeles Backyards

A team of researchers in Los Angeles has just described 30 new species discovered during a three-month study in ordinary backyards.�� Emily Hartop, who did much of the biological grunt work, has written a nice description of the project, and what it means:

A team of researchers in Los Angeles has just described 30 new species discovered during a three-month study in ordinary backyards.�� Emily Hartop, who did much of the biological grunt work, has written a nice description of the project, and what it means:

When I came to work at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, I had no idea exactly what was in store for me. The NHM had recently initiated a massive study to search for biodiversity, or the variety of life forms in a particular area. This study wasn���t taking place in some lush tropical jungle, though; in fact, far from it. This fabulous study was (and is) taking place in the backyards of Los Angeles. I got hired to be part of the entomological team for this urban project called BioSCAN (Biodiversity Science: City and Nature) and before I knew it, I was describing 30 new species of flies collected right here in the City of Angels.

Before I explain how this all happened, let���s pause and say that again: 30 new species of flies were described from urban Los Angeles in 2015. Let���s expand: these flies were caught in three months of sampling and are all in the same genus. What does this mean for us? It means that even in the very areas where we live and work,

our biodiversity is critically understudied. It means that in your own backyard, or community park, live species that we do not even know exist. It means that all of those invisible ecosystem processes that occur all around us are being conducted, in part, by creatures we know nothing of. It means BioSCAN is off to a good start, but we have a lot of work to do.

BeginningsMy boss, NHM Curator of Entomology Dr.��Brian Brown, has spent years working on an amazing group of flies called phorids. When I started in January 2014, I knew next to nothing about phorids; I knew they were small flies that did some cool things (like decapitating ants and killing bees and eating cadavers in coffins) and that was about it. When I came in to volunteer my time prior to my official start date, Brian sat me down with some samples from Costa Rican rice paddies and asked me to pull out all the phorids for further study. I only vaguely knew what a phorid even looked like, so I had a steep learning curve that first day. Soon, though, I could recognize a phorid as easily as picking out an orange in a bunch of apples

Check out Hartop’s full account, plus a video, here.

March 23, 2015

Thank Maggots for the Ecological Succession Idea

The big idea that there is a more or less predictable succession of species in the history of any ecosystem generally gets credited to Henry C. Cowles at the University of Chicago, with a nod to Henry Thoreau.

But the two Henrys can now take a backseat to a forensic entomologist–the sort of character otherwise familiar from the various CSI shows–working at the beginning of the nineteenth century in France.�� Here’s the press release, from Cowles’s own University of Chicago (oh, the ingratitude):

For generations, students have been taught the concept of “ecological succession” with examples from the plant world, such as the progression over time of plant species that establish and grow following a forest fire. Indeed, succession is arguably plant ecology’s most enduring scientific contribution, and its origins with early 20th-century plant ecologists have been uncontested. Yet, this common narrative may actually be false. As posited in an article published in the March 2015 issue of The Quarterly Review of Biology, two decades before plant scientists explored the concept, it was forensic examiners who discovered ecological succession.

According to Jean-Philippe Michaud, Kenneth Schoenly, and Ga��tan Moreau, the first formal definition and testable mechanism of ecological succession originated in the late 1800s with Pierre M��gnin, a French veterinarian and entomologist who, while assisting medical examiners to develop methodology for estimating time-since-death of the deceased, recognized

the predictability of carrion-arthropod succession and its use in forensic analysis. By comparison, studies generally cited by modern ecology textbooks as the earliest examples of succession were published in the early 1900s.

Michaud and colleagues found no evidence that plant and carrion ecologists were initially aware of each other’s contributions. Instead, they describe the case as an example of multiple independent discovery, similar to how Darwin and Wallace each developed the theory of evolution by natural selection independent of one another. “[G]iven their disparity in subject matter, training, and institutional structures,” the authors assert, “these two groups were unaware of each other’s publications.”

Despite marked differences between the two disciplines, however, plant ecology and carrion ecology accumulated strikingly similar parallel histories and contributions. Both groups used succession-related concepts to refute the theory of spontaneous generation, for example, and both offered a qualitative framework of the mechanisms involved. As well, both placed high importance on typological concepts (e.g., “seres” in plant ecology and “squads” and decay stages in carrion ecology) and the roles of site and climate in shaping successional outcomes.

Although side-by-side examinations of the histories of carrion ecology and plant ecology, especially under a lens of succession, reveal the clear paradigm shifts that formed each discipline and emphasize the different objectives and cultures that kept them apart, Michaud and colleagues believe these comparisons can ultimately serve to benefit each field. “By comparing the contributions of plant and carrion ecologists, we hope to stimulate future crossover research that leads to a general theory of ecological succession.”

Journal Reference:

Jean-Philippe Michaud, Kenneth G. Schoenly, Ga��tan Moreau. Rewriting ecological succession history: did carrion ecologists get there first? The Quarterly Review of Biology, 2015; 90 (1): 45 DOI: 10.1086/679763

March 22, 2015

A Wildlife Where’s Waldo

Texas conservationist John Karges picked up a piece of lumber lying on the ground at Las Estrellas Preserve, a Nature Conservancy Property in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas.�� Then he took this picture and immediately put the plank back down.�� He now calls that plank “the Waldo Board,” because it set him off on a search for species taking shelter beneath it. So far he’s found “three Texas banded geckos, three Great Plains narrow-mouthed toads, one centipede, at least one beetle larva,” and probably other stuff since he posted this seven hours ago.

Texas conservationist John Karges picked up a piece of lumber lying on the ground at Las Estrellas Preserve, a Nature Conservancy Property in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas.�� Then he took this picture and immediately put the plank back down.�� He now calls that plank “the Waldo Board,” because it set him off on a search for species taking shelter beneath it. So far he’s found “three Texas banded geckos, three Great Plains narrow-mouthed toads, one centipede, at least one beetle larva,” and probably other stuff since he posted this seven hours ago.

I still can’t find the damned centipede.�� You give it a try.�� Hints after the break.�� I first noticed the toads by the shape of the hind legs of the largest one. Then that soft bluish-gray�� color led me to the others.�� I also had to download the picture and enlarge it to see much of anything.

March 21, 2015

A Plan to Mine Coal in the Birthplace of Rhino Conservation

(Photo: Richard Conniff)

My latest for Takepart:

A few years ago, I was reporting a story about South Africa���s war on rhinos. I suppose you could call it “Vietnam���s war” or “Asia���s war,” since that���s where most of the rhino horn ends up, to supply a bogus medicinal trade. But let���s face it: South Africa���s own political and financial elite tolerate the poaching of more than 1,000 rhinos in the nation every year, probably because they profit from it.

In any case, the obvious place to start my reporting was the birthplace of rhino conservation: Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, in the coastal state of Kwazulu-Natal. This is where an earlier generation of South Africans saved the white rhino from certain extinction, carefully breeding the species back from just 20 animals in the world at the end of the 19th century to a population of 20,000 today.

In 1895, they also designated Hluhluwe-iMfolozi (pronounced ���shluh-shloo-ee���) Africa���s first nature preserve.

This should be a great national heritage, and also a source of cultural pride: The broad river valleys and rolling highlands of Hluhluwe-iMfolozi were once the favorite hunting ground of Shaka, the storied Zulu warrior king. The park is home not just to white rhinos but also to critically endangered black rhinos, as well as elephants, lions, leopards, buffalo, and 340 species of birds.

But now Ibutho Coal, a little-known mining company rumored to have important political connections, wants to build an open-pit coal mine a few hundred feet from the edge of the park. You would think rejecting this proposal would be an open-and-shut case���and if it was happening anywhere but South Africa, it probably would.

While the mine would be outside the protected area, it would be close enough to wreak hydrological havoc on the park, according to Roger Porter, an ecologist with Global Environmental Trust, which is running a campaign to stop the mine. Extracting anywhere from 37 million to 318 million tons of anthracite from the proposed 56-square-mile concession���an area half again as big as Manhattan���could cause the local water table to drop, Porter said. The soil would dry out, and ���that would affect the vegetation, and therefore the food supply of animals.���

Local groundwater could also end up contaminated by the mine, affecting the water supply for people living downstream.

In any case, said Kirsten Youens, a lawyer for Global Environmental Trust, ���there is really no viable source for water��� for the mine���s operations.

Ibutho Coal has suggested damming one of the tributaries to the Umfolozi River, ���which is completely insane,��� said Youens. The Umfolozi River is already water-stressed and ran dry in last year���s drought.

The mine would likely bring other problems as well. Coal dust contaminated with heavy metals would�� land on vegetation, making it less appealing to herbivorous animals and reducing the ability of the plants to photosynthesize. The coal dust could also hurt aquatic biodiversity in the park, according to Porter.

While the use of drones in Hluhluwe-iMfolozi has stopped rhino poaching over the past six months, the proposed mine could vastly increase the poaching threat. Low-paid mining workers in new settlements almost inevitably turn to poaching to supplement their diet.

And there would be blasting, ���24-7, night and day,��� said Porter, that could disrupt the low-pitch ���infrasound��� language with which elephants communicate. Rhinos also depend on their excellent hearing, not least because their eyesight is lousy.

For visitors, it���s also hard to enjoy a wilderness if it sounds like a war zone.

On top of the issues within the park, people currently live where Ibutho Coal wants to mine. They would have to be relocated, along with schools, clinics, and other infrastructure in their villages.

The mine proposal has already been rejected once, last September. In a letter, the South African Department of Economic Development, Tourism, and Environmental Affairs reprimanded Ibutho Coal for failing to engage directly with people living in the area. It also voiced concerns over the size of the buffer zone between the park and the mine.

But the fight is far from over: Earlier this month, Ibutho Coal submitted a revised application.

The suspicion reported last year is that larger corporate interests are backing the proposal while staying in the shadows. In the local Fuleni community, people suspect that government officials, all the way up to the family of President Jacob Zuma, will benefit from the project. But so far, these rumors are unsubstantiated, and Ibutho declined TakePart���s request for an interview.

To help cover the legal costs of fighting the proposed mine, Global Environmental Trust has launched a Kickstarter-style crowdfunding campaign.

Here���s a glimpse of what���s at stake:

During that trip I took to Hluhluwe-iMfolozi, I hiked out into the bush with a wildlife researcher. We climbed a tree to watch a couple of black rhinos resting in the distance. Then a horn tip and two ears rose above the seed heads of the grass and swung in our direction like a periscope: One of them had heard us.

Rhinos are curious animals, so she ambled over to investigate. Her flanks were more blue than gray, glistening with patches of dark mud, and she was visibly pregnant. She stopped when she was about eight feet from our perch, eyeing us sideways, curious but also skittish. Her nostrils quivered and the folds of flesh above them seemed to arch like eyebrows, inquiringly. I held my breath. Then suddenly her head pitched up as she caught our alien scent. She turned and ran off, huffing like a steam engine.

That���s the natural and cultural heritage South Africa should be fighting to protect. Stay tuned to see if short-term profits will prevail instead.

Geoffrey Giller contributed reporting to this column.

March 19, 2015

How Outdoor Cats Mess Up Our Minds

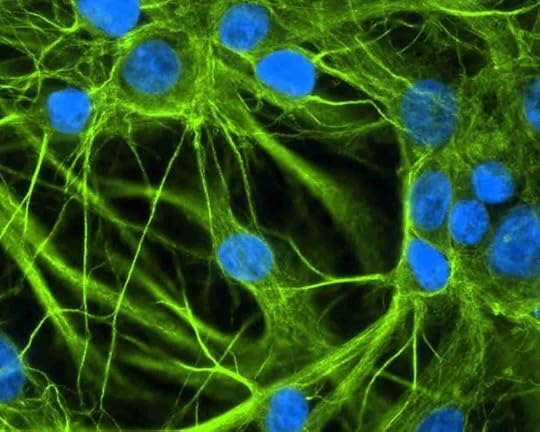

Toxoplasmosis from outdoor cats makes major changes in the brain’s most common and critical cells, called astrocytes.

(Image: Indiana University School of Medicine)

Neuroscientists are coming closer to understanding how cat-borne Toxoplasmosis messes with the brains of mice, men, and women.

With apologies, the press release could be a lot more clear in describing a new study showing how this parasite affects the brain.�� But I’m on another deadline, and want to post this now because it’s important for pet-owners to get the message: We endanger ourselves when we allow our pet cats to wander outdoors:

Rodents infected with a common parasite lose their fear of cats, resulting in easy meals for the felines. Now Indiana University School of Medicine researchers have identified a new way the parasite may modify brain cells, possibly helping explain changes in the behavior of mice — and humans.

The parasite is Toxoplasma gondii, which has infected an estimated one in four Americans and even larger numbers worldwide. Not long after infecting a human, Toxoplasma parasites encounter the body’s immune response and retreat to a latent state, enveloped in hardy cysts that the body cannot remove.

Before entering that inactive state, however, the parasites

appear to make significant changes in some of the brain’s most common, and critical cells, the researchers said. The team, lead by William Sullivan, Ph.D., professor of pharmacology and toxicology and of microbiology and immunology, reported two sets of related findings about those cells, called astrocytes, March 18 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Astrocytes are found throughout the brain and are involved in a variety of important brain structures and activities. Dr. Sullivan and his team evaluated the proteins in astrocyte cells and found 529 sites on 324 proteins where compounds called acetyl groups are added to proteins, creating a map called an “acetylome,” much like a map of all the genes in a particular species is known as its “genome.” In addition, 277 sites on 186 of the proteins had not been reported in previous studies of other types of cells. This process of acetylation can alter the function, location or other aspects of those proteins in the cells, providing new insight into how these cells operate in the brain.

Having created the first acetylome for astrocytes, the researchers then found a significant number of proteins that were acetylated differently in brain tissue infected with Toxoplasma parasites.

“We don’t know the impacts of these changes yet, but these discoveries could be particularly significant in understanding how the parasites persist in the brain and how this ‘rewiring’ could affect behavior in both rodents and humans,” Dr. Sullivan said.

In a separate article in the March 2015 issue of Scientific American Mind, Dr. Sullivan and IU School of Medicine colleague Gustavo Arrizabalaga, Ph.D, professor of pharmacology and toxicology and of microbiology and immunology, describe research by others dating back to the 1980s showing that rodents infected with Toxoplasma behave differently, including not only being unafraid of cat odors, but actually attracted to them. In effect, research suggests, Toxoplasma modifies the host rodents’ brains so that the animals will be eaten and the parasites can make their way to the cat intestinal system — the only place where Toxoplasma can sexually reproduce.

Intriguingly — and much more speculatively, Drs. Arrizabalaga and Sullivan warn — some research has suggested that Toxoplasma infection could alter human behavior, and that changes could vary by gender. One study found that infected men tend to be introverted, suspicious and rebellious, while infected women tended to be extraverted, trusting and obedient. Others have suggested an association with schizophrenia.

“The studies in humans have been relatively small and are correlative. In contrast, the behavioral changes seen in mice infected with Toxoplasma are much better characterized, although we still don’t know the mechanisms the parasite employs to alter host behavior,” Dr. Sullivan said. “But our analysis of the astrocyte acetylome changes could move us toward better understanding of Toxoplasma’s actions and the implications for behavioral impacts.”

Initial Toxoplasma infection generally causes symptoms similar to the flu, while the latent form of infection has little physical impact on healthy people. However, the parasites can become active again and cause tissue damage in people with compromised immune systems, such as patients receiving chemotherapy or infected with HIV.

In addition, if a woman’s initial infection with Toxoplasma occurs while she is pregnant, miscarriage or birth defects can result.

Humans can become infected if they don’t wash carefully after collecting cat litter containing Toxoplasma. Gardens and other areas frequented by wild and feral cats can become reservoirs for Toxoplasma, so experts recommend using gloves and masks when working in such areas. Unwashed vegetables and undercooked meats can also lead to Toxoplasma infection.

.

Journal Reference:

Anne Bouchut, Aarti R. Chawla, Victoria Jeffers, Andy Hudmon, William J. Sullivan Jr. Proteome-Wide Lysine Acetylation in Cortical Astrocytes and Alterations That Occur during Infection with Brain Parasite Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS One, March 18, 2015 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117966

March 15, 2015

How Science Education Came to America–The Patriarch Part 1

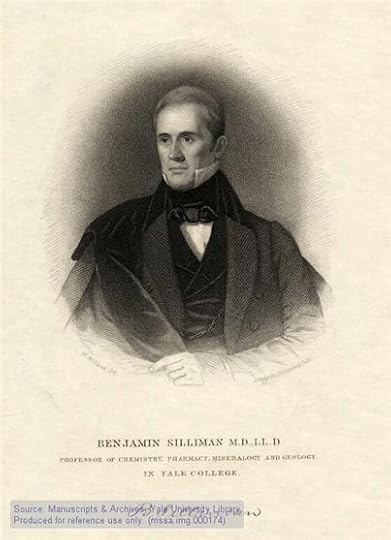

Benjamin Silliman Sr.

Undergraduates at Yale are associated with a single residential college for their entire four years, and when I was a student, my college was named Silliman College.�� It was my home.�� I was, yes, a Sillimander.�� But the name Silliman was just a name to me, another one of those obscurely eminent names from Yale’s past.��

For the past year, though, I have been working on a new book (working title: House of Lost Worlds) about how the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History changed our world. And in the course of my research, I learned that Silliman–Benjamin Silliman Sr.–was a far more important figure in American history, and the history of American science, than I had imagined.�� Here’s the story:

On October 26, 1802, a 23-year-old Yale-educated lawyer boarded a stagecoach in New Haven for the long, dusty, motion sickness���inducing trip to Philadelphia. Under his arm, he carried a wooden candle box full of mineral specimens to be properly identified.

They were remnants of a higgledy-piggledy museum of curiosities Yale had maintained for a time but then largely misplaced, not altogether regrettably. The original collection had included a 50-pound set of moose antlers, a nine-foot-long wooden chain carved from a stick by a blind man, and a two-headed calf. It also included miscellaneous unlabeled mineral specimens. The candle box in which Benjamin Silliman carried these specimens to Philadelphia would enter Yale legend as the beginning of proper scientific collecting at Yale. More than that, it was the beginning of the collections that would later become the Peabody Museum of Natural History, and the beginning of Yale���s rise from a college to a university.

The polymath Thomas Jefferson was in the White House, yet for most Americans then, science was still a foreign enterprise, somewhat nervously regarded. There were signs of growing interest in this strange idea of knowing the world not just by faith but by experiments, expeditions, and observation. But many considered it a threat to their religion and to the idea of a classical education.

Timothy Dwight IV, then president of Yale, had seen that it was time for the college to branch out from its primary function as a training ground for Congregational ministers. He wanted to add a faculty position in chemistry and natural history. But Dwight was a pastor and an adamant defender of the Congregational Church in Connecticut, and he was cautious. He said he could find no American who was qualified for the job, and he feared that ���a foreigner, with his peculiar habits and prejudices, would not feel and act in unison with us��� however able he might be in point of science.���

Instead, Dwight had turned in 1801 to Silliman, a recent Yale graduate and family friend, who was known to be devout. So devout, in truth, that he could describe Yale contentedly as ���a little temple,��� where ���prayer and praise seem to be the delight of the greater part of the students.��� Silliman admitted to being ���startled and almost oppressed��� by Dwight���s job offer. He knew nothing about science. It was a spectacularly inauspicious start.

Dwight argued his way around Silliman���s concerns. He pointed out that there were already plenty of lawyers, but as a scientist ���the field will be all your own.��� He also advised Silliman not to pursue a job possibility he had been considering in Georgia, because of the morally repugnant association with slavery. Silliman had become adamantly opposed at Yale to ���the sin and shame of slavery,��� but his Fairfield County family was neck deep in the Connecticut practice of slaveholding. Dwight cleverly made the Georgia job sound like a kind of falling back.

Thus Silliman soon found himself en route to Philadelphia to take a crash course in chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, which had the nation���s first school of medicine. Dwight, it turned out, had chosen wisely. Silliman was certainly devout. But after another year studying and attending lectures in London and Edinburgh, he was also a knowledgeable and enthusiastic teacher of chemistry, and later of mineralogy and geology. He came back to lecture brilliantly at Yale, and these lectures were the beginning of science education in America, that is, of science for its own sake, not merely as an adjunct to medicine.

Continue reading at “The Teacher, Preacher, and P.R. Man of Early Science.”

The Teacher, Preacher, P.R. Man of Science–The Patriarch Part 2

Continued from “How Science Education Came to America”:

His Eminence

Benjamin Silliman would become a great name. He was ���the Patriarch��� of American science, according to Louis Agassiz, the Swiss biologist who would take up the mantle of science education at Harvard in 1847. But Silliman would do so without making any great discoveries, without introducing any bold new concepts or systems, and without ever fitting the stereotype of the scientist as solitary brooding genius. On the contrary. What American science needed then was ���an organizer, a promoter, a teacher, a preacher, a public relations man, a communicator and coordinator, and an exemplar of professionalism,��� science historian Robert Bruce has written. ���Silliman was all of these.���

He was a charismatic figure, with a clear and forceful way of speaking and an impressive, even aristocratic physical presence���tall and lean, ���erect as a general on parade and with a general���s expression of great power,��� as a former student recalled, with a high brow, deep-set eyes, a thin straight nose, and slightly pursed lips���altogether inspiring confidence and even belief in his listeners.

Silliman made it his mission to develop science and science education at Yale, and later nationwide. For this, he also possessed the ineffable trait that Bruce describes as ���effectiveness in procuring facilities and supplies.��� It wasn���t just that he had a keen eye for new material to embellish the Yale collection; he was also adroit at wheedling funds out of the Yale Corporation to pay for these acquisitions. Much of this effort went in support of mineralogy, a topic early Americans found far more tantalizing than we generally do today. For them, it afforded ���a pleasant subject for scientific research,��� according to an 1816 account, and also tended ���to increase individual wealth��� and ���to improve and multiply arts and manufactures and thus promote the public good.���

Mineralogy attracted some colorful personalities. Silliman handed over $1,000, a huge sum then, for one mineral collection, notwithstanding that it had been put together with profits from the most notorious quack medical invention of that era, Elisha Perkins���s ���Metallic Tractors.��� Silliman���s brother, a lawyer in Newport, arranged the purchase of a mineral collection brought from England by a doctor who then had the misfortune to die in a duel over his ���too great familiarity��� with the wife of a South Carolina plantation owner.

One coveted acquisition eluded Silliman, at least at first. In the darkness before dawn on December 14, 1807, a ���globe of fire,��� seemingly half the size of the full moon, blazed across the skies of western Connecticut. Darkened rooms went bright as day. Farmers started up from their chores, or sat upright in bed in terror, as if the Judgment Day had come. As locals later described it to Silliman, three ���loud and distinct reports,��� like cannon shots, burst over the town of Weston, followed by ���a continued rumbling, like that of a cannon-ball rolling over a floor.��� It was a meteorite, estimated by Silliman to be at least 300 feet in diameter before it broke apart and rained down in pieces.

Silliman and a faculty friend, ecclesiastical historian James L. Kingsley ���99, arrived on the scene a few days later to gather eyewitness accounts and obtain a few fragments by purchase (the weeping and teeth-gnashing among local farmers having given way to gleeful profiteering). A detailed report by the two professors, including Silliman���s chemical analysis, concluded that the meteorite had come from outer space. Their account was soon being read aloud before learned societies in Philadelphia, London, and Paris. President Thomas Jefferson was skeptical, supposedly remarking, ���I would more easily believe that two Yankee professors would lie than that stones would fall from heaven.��� He had reason to mistrust Yale and Connecticut, both then bastions of anti-Jeffersonian Federalism, but the quote was probably apocryphal. The skepticism, on the other hand, was genuine. In a later letter, Jefferson wondered pointedly how the meteorite ���got into the clouds from whence it is supposed to have fallen.���

Like much of the educated world then, Jefferson was still struggling with the dogma-shattering idea, introduced just a dozen years earlier by the French comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier, that species created by God could become extinct. As a passionate advocate of scientific discovery and president of the nation���s first great scientific organization, the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, Jefferson had authorized funds to excavate the bones of a mastodon���the very species that alerted Cuvier to the possibility of extinction. And yet he also ardently pursued the hope that these mammoth creatures still lived in the unknown American West. Jefferson must have been equally torn now by the idea that the Earth God had made for man could be randomly bombarded from the heavens. (Though if it must be so, why not Connecticut?) These doubts were characteristic of a nation and a time in which ancient cultural and religious beliefs were constantly crashing up against new facts. That is, it was a nation struggling to come to terms with science.

Continue reading at “Spreading the Word About Science” …

Spreading the Word About Science–The Patriarch Part 3

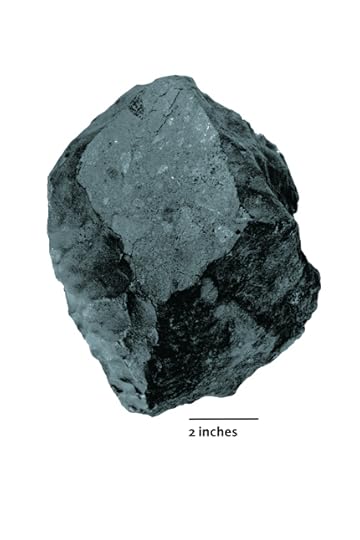

The Weston meteorite.

Continued from “The Teacher, Preacher, PR Man of Science”:

In the course of their research, Silliman and Kingsley had spent several hours searching fruitlessly for one unusually large stone that had landed in the town of Trumbull (Silliman���s birthplace, as it happened). When it finally turned up, after they���d gone back to New Haven, it weighed 36.5 pounds���and the lucky farmer who found it thought it was worth $500.

An amateur mineral enthusiast, Colonel George Gibbs (the rank was honorific), placed the high bid. He was the heir to a Newport shipping fortune, which he seems to have had no great interest in preserving. Among other acquisitions, he had recently purchased and brought home the extensive mineral collection of a Russian count, and another collection accumulated over 40 years by a great patron of science in France.

Even before the meteorite episode, Silliman���s brother in Newport had tipped him off about Gibbs. Silliman and Gibbs soon met, became friends, and spent time geologizing together around New England. In 1810, when he was considering a suitable place to display his mineral ���cabinet,��� Gibbs made inquiries at institutions from Boston to Washington, without quite finding what he was hoping for. Finally, he stopped in to visit Silliman in New Haven and announced, ���I will open it here in Yale College, if you will fit up rooms for its reception.��� Yale promptly did so, on the second floor of what is now Connecticut Hall. And thus, among many other treasures, the 36.5-pound Weston meteorite came to Yale.

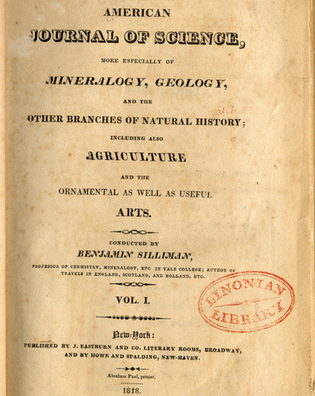

Gibbs also provided one other critical boost not just to Yale but to American science at large. Late in 1817, he bumped into Silliman by chance one day aboard the steamboat Fulton, on the ten-hour run between New York and New Haven. A mineralogist who had sporadically published a journal for that discipline was in failing health, and Gibbs urged Silliman to take up the challenge of producing a more broadly focused scientific journal. The following year, having sought and received his predecessor���s blessing, Silliman launched the American Journal of Science. It soon became t he nation���s premier scientific periodical, often referred to simply as ���Silliman���s Journal.���

he nation���s premier scientific periodical, often referred to simply as ���Silliman���s Journal.���

The rapidly growing Yale mineral collection���in truth, still largely the Gibbs collection���meanwhile began to attract important visitors to New Haven. The collection moved, in 1820, to a space upstairs from the new college dining hall, a prominent building in the heart of the campus later known simply as the ���Cabinet Building.��� For Silliman and Yale, things seemed to be progressing smoothly. But in 1825, Gibbs suddenly announced that he needed to sell. Given his friend���s spending habits, Silliman should have been ready. But he was startled, especially because the price Gibbs named for the mineral collection, $20,000, represented two-thirds of Yale���s annual income. Silliman was soon out raising funds by pamphlet, public meeting, and door-to-door in New Haven and New York. Yale���s new president, Jeremiah Day ���95, also knocked on doors, determined not to lose the collection that, as Silliman put it, had been for ���so long our pride and ornament.��� In the end, they raised half the asking price, and Gibbs graciously accepted a note for the balance.

The collection became the basis around which a community of scholars���scientists, as they were just beginning to be known���began to gather at Yale. Silliman built on the prestige of the collection to help Yale found a science school (later the Sheffield Scientific School); the first college art gallery, largely by arrangement with his wife���s uncle, the artist John Trumbull; and the medical school. All this helped nudge Yale well along the path from a college into a university. Among those who turned their attention to Yale as a result was an amateur mineralogist still at prep school, O. C. Marsh ���60, who carefully noted in his journal a quotation from Silliman on the art of acquisition: ���Never part with a good mineral until you have a better.��� Marsh would later study under Silliman and in time help found the Peabody Museum to house the mineral collection properly. He would also use the museum to make Yale the great center of paleontological discovery in the nineteenth century, going into the American West to bring back the sort of monstrous creatures���Brontosaurus, Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, Triceratops���that would have delighted Jefferson, except that they were thoroughly extinct.

Another Silliman student, Daniel Coit Gilman, would become the college librarian and an important figure in the rise of Yale���s Sheffield Scientific School. He would move on to become the first president of Johns Hopkins University and later of the Carnegie Institution, both with a focus on fostering scientific research. Still another student of Silliman���s, Amos Eaton, would help found what is now the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and pioneer the practice of applying the scientific method ���to the common purposes of life.���

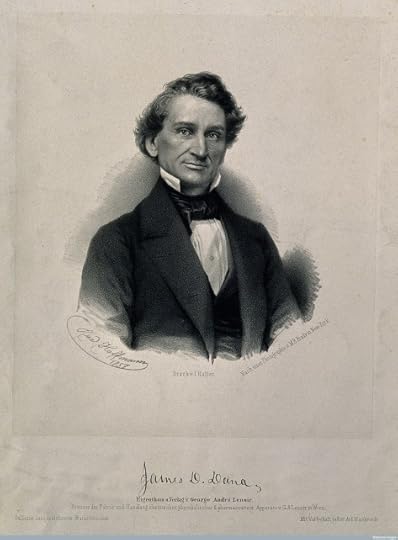

Silliman accomplished so much in part by nepotism. By the time he retired in 1853, he had established a family dynasty in science. Daniel Coit Gilman was distant kin: his brother had married a Silliman daughter. George J. Brush, a mineralogist and later director of the Sheffield Scientific School, had married Harriet Silliman Trumbull, a Silliman cousin. The faculty also included Silliman���s son Benjamin Jr., a chemist who would play a key role in launching the Age of Petroleum, and Silliman���s former student and son-in-law James Dwight Dana ���33, who was both a zoologist and a celebrated geologist. Dana���s son Edward S. Dana ���70, ���76PhD, would also eventually join the faculty. What mattered, beyond the nepotism, was that Silliman had made it seem perfectly reasonable for Yale, the former Congregational seminary, to employ eight faculty members in science versus just five for theology.

Read the conclusion of this article at “Science and the Rise of the American University“

Science & The Rise of the American University–The Patriarch Conclusion

James Dwight Dana, 1857

Continued from “Spreading the Word about Science”:

The line dividing science and theology was, however, still practically nonexistent, and in this somewhat delicate context, James Dwight Dana was undoubtedly the most important of Silliman���s disciples. He was both a deeply religious man and the greatest American geologist of the nineteenth century, and much as Silliman had done for Timothy Dwight, he made it possible to expand the role of science without seeming overly threatening to religion or the humanities. Dana also explicitly took up Silliman���s mission of using the sciences to build Yale into a university.

In 1856, Dana gave a speech to Yale alumni lamenting those ���who still look with distrustful eyes on science.��� They seem, he said, ���to see a monster swelling up before them which they cannot define, and hope may yet fade away as a dissolving mist.��� That specter was twofold: the shadow cast by geology on the Genesis account of the Earth���s history, and the idea of evolution, which was already in the air. (Among other developments, a former student of Silliman���s named Thomas Staughton Savage, a missionary, had recently brought home from Africa the bones of an unknown primate with a disturbing resemblance to humans���the gorilla.) But Dana was deeply committed to a biblical view of creation, and he assured his listeners of the evidence provided by geology ���that God���s hand, omnipotent and bearing a profusion of bounties, has again and again been outstretched over the earth; that no senseless development principle evolved the beasts of the field out of monads������that is, unicellular organisms������and men out of monkeys, but that all can alike claim parentage in the Infinite Author.��� (Silliman shared this belief. In one of his last lectures he had declared, ���Young men, those people may think as they please but for my part I shall never believe or teach that I am descended from a tadpole!���)

Having dismissed the evolutionary bugaboo, Dana went on to argue for the expansion of scientific study on the Yale campus, with new laboratories, lecture halls, and above all a museum, ���a spacious one.��� This museum, Dana said, ���should lecture to the eye, and thoroughly in all the sections represented, so that no one could walk through the halls without profit. It should be a place where the public passing in and out, should gather something of the spirit, and much of the knowledge, of the institution.���

Then rising to his conclusion, he called on the alumni to help build ���the first university in the leading nation of the globe.��� Why not have here, in this land of genial influences, beneath these noble elms��� why not have here, THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY,���where nature���s laws shall be taught in all their fullness, and intellectual culture reach its highest limit!���

By coincidence���or perhaps Dana would say ���miraculously������the means of making the first part of this vision a reality arrived in New Haven just days after Dana���s speech. On August 3, 1856, the aspiring freshman O. C. Marsh took the exam for admission to Yale. By good fortune for all, he aced it. Ten years later, with money from his uncle George Peabody, a leading merchant banker, Marsh and Dana together would found the Peabody Museum.

The second part of the vision, creation of a great American university, would take a little longer. Though some people in the humanities continued to regard it with suspicion, the Sheffield Scientific School was able to expand its faculty and become a greater presence on campus. The New Haven railroad magnate Joseph E. Sheffield had not attended Yale, but no doubt in part because his son-in-law John Addison Porter ���42 taught chemistry there, he provided continuing support for the school that was now named for him. Yale was also one of the first schools to take advantage of the Morrill Act of 1862, a national land-grant program promoting technical and scientific education.

Yale would not officially call itself a university until 1887, after another Timothy Dwight, Class of 1849 and the grandson of the Timothy Dwight who had hired Silliman, became its president. Even as late as 1885, the Nation could still describe Yale as ���an institution practically governed by a few clergymen of a single denomination in a single state.��� But the change was well under way. By the early 1860s, with the Peabody and Sheffield gifts adding to the Morrill Act money, Yale scientists knew it. Mineralogist George J. Brush was exultant: ���You can form no idea how every one seems [to] have waked up to the fact that Yale is to be a great university.���

Dana agreed: ���The time of her renaissance has come!!���