Richard Conniff's Blog, page 33

March 14, 2015

Seven Ways to Make Your City Wildlife Friendly

(Photo: Getty Images)

A few years ago I was visiting the west Baltimore neighborhood that inspired the American television series Homicide and The Wire. It was an urban wasteland, the brick row houses largely abandoned and boarded over. Whoever used to live here had long since gone away. Then we turned a corner onto North Carrollton Avenue, and for one city block it was a miracle:�� Handsome old trees formed a green canopy over the street. The houses were occupied and well tended. Someone was selling flavored ices at a stand in the shade in the middle of the block. The trees, a local woman told me, made all the difference, shading the houses, filtering the air, and making it easier to breathe. There were birds and squirrels in the branches overhead.

That visit comes to mind because I have been thinking lately about ways to make cities more livable, for people and wildlife alike. The rapid urbanization of the Earth is the dominant movement of this century, and the sprawling, unplanned growth of cities and suburbs tends to leave behind patches of greenery only by accident���a few neglected parks, some street trees here and there, and the occasional sliver of protected land. Wildlife gets crowded out and pushed toward extinction.

Plenty of studies have already demonstrated that street trees and other green spaces tend to reduce crime, improve health, build stronger neighborhoods, encourage investment in housing stock, slow stormwater runoff and lower pollution. So let���s focus on the wildlife for now. Cities are not ideal wildlife habitat, but they are increasingly the only habitat. So what do we need to do to make room for wildlife in our increasingly urbanized world?

Plan for Green Space

Add some trees along a street, and you���ve got someplace where birds can rest or roost. Add a park at the end of that street, even a small one, and now you���ve got a spot where migrating birds can stop and eat on their way to or from their breeding grounds. Even adding just 150 square meters of green space���that���s 10 parking spaces���will bring one additional bird species into a neighborhood, according to a 2013 study by urban greening specialist Paige Warren at the University of Massachusetts���Amherst. The green space can include a community garden that benefits human residents. Bees, butterflies, and other pollinators will also show up, said Warren, ���even in very dense metropolitan areas like in Manhattan.���

Make those Green Spaces Connect

Multiple parks or gardens that are connected make for exponentially

better habitat. This is true at large scale: The Yellowstone to Yukon initiative, for example, seeks to connect protected lands so animals like grizzly bears and wolves can roam freely through this 2,000-mile-long ecosystem. But connectivity is important for green spaces at the neighborhood scale too, according to Madhusudan Katti, an ecologist at California State University, Fresno. For instance, ���canopy corridors��� created by street trees help squirrels to move safely from one park to another. Salamanders, on the other hand, may need road underpasses to get to the wetlands where they breed. For animals that can fly, like birds and bees, connectivity may be less about physical connection than the proximity of green spaces, Warren said.

The idea of building green corridors within cities is not new: Newark, New Jersey, may not be your idea of a garden spot, but Branch Brook Park winds through the heart of the city for 360 acres, and next month the largest collection of cherry blossom trees in the United States will be in flower there.

Plant for Wildlife

If you���ve got a local species you���re worried about, put in the kinds of plantings it needs to breed or feed. Monarch butterflies, for instance, require milkweed. Birds love oak trees (because they���re home to so many juicy caterpillars). If you happen to live in the Northeast, a guide published by The New York Times this week is useful: Bayberries for yellow-rumped warblers and black-eyed Susans for goldfinches are among the recommended plantings. Wherever you live, native plants are the key ingredient for native species. Avoid the exotics, especially the ones, such as barberry and purple loosestrife, that spread rapidly and wreak havoc on surrounding ecosystems. ���Cities are a nexus for introduction��� of invasive species, said Paige.

Invasive animals are also a problem, especially when pet owners do what they think is the humane thing by setting exotic species free. Burmese pythons are currently decimating the native mammal populations in the Florida Everglades.

Make Buildings Bird-Friendly

Cities can be rough for birds. In New York City alone, 90,000 birds die each year from flying into glass windowpanes that are invisible to their eyes. A 2014 paper estimated that across the United States, between 365 million and a billion birds may die from collisions with buildings each year. For ways to prevent your house from contributing to the problem, check recommendations in a report from the American Bird Conservancy. Some cities have also begun adopting bird-friendly building guidelines, as San Jose, California, did last week. A program called ���Lights Out��� has also been gaining traction in some cities. In the spring and fall, when many birds migrate, the bright lights from buildings can disorient them. Building owners in Boston, Chicago, Minneapolis, New York, and other cities have voluntarily agreed to turn off some or all lights at night. One incidental benefit: lower electric bills.

Get Educated

Outdoor cats are�� major bird killers. In many cities, one attempt to control the problem, called ���Trap-Neuter-Return,��� or TNR, has gained popularity among people who are unwilling to euthanize unwanted cats. But it doesn���t really work. If you���re a cat owner, spay or neuter your cat and keep it indoors. Work to outlaw feral cats in public parks and green spaces. They are just subsidized death squads for wildlife.

Cities also need to educate residents about how to live side by side with wildlife, because the wildlife is showing up, even uninvited. When New York City realized that it has well-established coyote populations in several city parks, the city made plans to post fliers and hand out cards listing ���Five Easy Tips for Coyote Coexistence,��� including the cardinal rule of keeping wildlife wild: Don���t feed the animals. In Bakersfield, California, the tiny San Joaquin kit fox is an endangered species, and it likes to den under sidewalks and beneath schools. The California Department of Fish and Game includes information about the foxes as part of its ���Keep Me Wild��� campaign. Among the suggestions: Pet food should stay indoors, to avoid feeding wildlife even accidentally.

Look Beyond City Limits

Even the roads connecting a city to the outside world can become wildlife habitat. By changing the timing and frequency of mowing roadside margins, some forward-thinking highway departments in Iowa, Florida, and a few other states are giving a break to ground-nesting birds, flowering plants, and pollinators. Roadside margins and even power transmission corridors can connect the fragmented habitat on the fringes of cities.

Though conservationists have tended to write off these ���wastelands,��� a new study published last month in the journal Animal Conservation found that some ground-nesting grassland birds around Chicago actually fledged more offspring when nesting near housing or other urban developments.

Take Action in Your Community

Lobby local building and zoning authorities to include wildlife-friendly provisions in their standard requirements. Last week the National Wildlife Federation named America���s Top Ten Cities for Wildlife. If your city���s not on the list (hello Boston, Chicago, and Seattle!) find out why not and what your city could be doing better.

Some cities are already asking any new development to include enough plantings and porous surfaces to handle all stormwater runoff on site. So why is Petco, Walmart, or Home Depot able to build in your community without setting aside a certain percentage of its parking area as green space?

When your city is debating how to prepare for climate change and rising sea levels, why not insist that saltmarsh buffer areas get equal consideration with seawalls? Those marshes incidentally benefit migrating shorebirds. (The seawalls only benefit contractors.)

Finally, we need an urban biodiversity index, so cities can start to benchmark their wildlife-friendliness against other cities of comparable size and begin to trade ideas for doing better. In fact, many cities worldwide are already adopting such an index pioneered by Singapore. Is there any reason this should not be coming to your neighborhood soon?

Geoffrey Giller contributed reporting for this column.

March 13, 2015

Is Your City One of the Nation’s Top 10 for Wildlife?

Mountain Lion in Griffith Park, Los Angeles (Photo: Steve Winter/National Geographic)

I’ll be writing soon about what you can do if your community doesn’t quite measure up.�� But meanwhile, here’s the top ten ranking for U.S. cities from the National Wildlife Federation:

Which American cities are going above and beyond the call of duty to protect America���s wildlife? The National Wildlife Federation is honoring the Top 10 Cities for Wildlife whose citizens have the strongest commitment to wildlife as part of our celebration of National Wildlife Week 2015.

“America���s most wildlife-friendly cities are located in every corner of our nation from sea to shining sea,” said Collin O���Mara, president and chief executive officer of the National Wildlife Federation. “The common thread between these cities is that citizens are coming together for a common purpose – to create a community where people and wildlife can thrive.”

The National Wildlife Federation ranked America���s largest cities based on three important criteria for wildlife ��� the percentage of parkland in each city, citizen action to create wildlife habitat, and school adoption of outdoor learning in wildlife gardens. The top cities are found in every region, from Seattle���s temperate rainforest to Albuquerque���s arid desert:

Austin, Texas ��� Austin is a clear-cut choice as America���s best city for wildlife, boasting the most Certified Wildlife Habitats (2,154), most Certified Wildlife Habitats per capita, and most Schoolyard Habitats (67). Famous for its Congress Avenue Bridge that���s home to 1.5 million bats, the city of Austin is certified as a Community Wildlife Habitat. Its residents not only want to Keep Austin Weird ��� they���re the best in America at keeping their city wild.

Portland, Oregon ��� The Rose City boasts America���s most Schoolyard Habitats per capita. With more than 8,200 acres of natural parkland certified salmon safe and a commitment to provide nature areas within a half-mile of every Portlandian, the dream of a wildlife-friendly city is alive in Portland.

Atlanta, Georgia ��� The City in a Forest rankshighly across the board, coming in #3 in total Schoolyard Habitats (54), #2 in Schoolyard Habitats per capita, and #2 in Certified Wildlife Habitats per capita.

Baltimore, Maryland ��� Charm City���s commitment to conservation education shines through with the second-most Eco-Schools in America (73), and a #3 ranking in Schoolyard Habitats per capita. Baltimore���s 5,700 acres of parkland include the Gwynns Falls/Leakin Park, the second-largest urban wilderness in the U.S.

Washington, District of Columbia ��� Ranked third in parkland as a percent of city area, DC���s efforts to protect and preserve parkland have helped restore America���s previously-endangered bald eagles and are now luring osprey back to the Anacostia River.

Seattle, Washington ���The Emerald City ranks third in Certified Wildlife Habitats per capita, with more than 30 municipalities and neighborhoods in the area participate in NWF���s Community Wildlife Habitat program. Seattle’s government has a robust environmental stewardship program��and a ���Green Factor��� program that reduces stormwater runoff and supports the use of native plants and trees.

Albuquerque, New Mexico ��� First in America in parkland as a percent of city area, one quarter of Albuquerque is public park land, providing a home for amazing resident and migratory wildlife like the majestic sandhill crane, Cooper���s hawks, black bears, bobcats and deer.

Indianapolis, Indiana ��� With the White River vital to both its people and wildlife, Indianapolis is home to America���s second-largest number of Certified Wildlife Habitats (932). It is also home to its own resident reality star, a peregrine falcon named KathyQ, whose live feed has entertained fans for several years.

Charlotte, North Carolina ��� Charlotte ranks third in the US in Certified Wildlife Habitats (849) and the city just achieved certification as a Community Wildlife Habitat. Known as North Carolina���s City of Trees, Charlotte���s City Council has made it a mission to have 50 percent canopy coverage by 2050.

New York City, New York ��� New York City has the most Eco-Schools in America (270), ranks fourth in parkland as a percent of city area (14 percent), and is home to an incredible 168 species of wildlife and more than five million trees. Home to year-round residents like red-tailed hawks and a tourist destination for migratory birds like black-throated blue warblers, the Big Apple is an urban wildlife haven, from Central Park to the Gateway National Recreation Area, one of America���s largest urban parks that includes the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge.

Honorable mentions: Broward County, Florida is America���s largest certified Community Wildlife Habitat and protects breeding beaches for endangered sea turtles; Los Angeles, California is home to 390 public parks, one million trees, and our favorite plucky mountain lion, P-22.

“No matter where you live in America, amazing wildlife is just outside your front door, even in big cities,��� said Patrick Fitzgerald, senior director for community wildlife with the National Wildlife Federation. ���Whether you have an enormous yard or just a corner of your school grounds that you can let go wild, everyone benefits when we make nature a welcomed part of our communities.”

National Wildlife Week is National Wildlife Federation’s longest-running education program designed around teaching and connecting kids to the awesome wonders of wildlife. Each year, we pick a theme and provide fun and informative educational materials, curriculum and activities for educators and caregivers to use with kids.��The theme of this year���s 77th Annual National Wildlife Week is “Living with Wildlife.”

Over several decades, America has achieved historic successes, conserving critical habitat, waterways and landscapes while bringing species like bald eagles, grizzly bears, and wolves back from the brink of extinction. We���re restoring bison populations and reintroducing them on western and tribal lands for the first time in a century. And thanks to the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, the air we breathe and the water we drink are cleaner than they have been in generations.

But at the same time, some of our most familiar species, from key pollinators like monarch butterflies and bees to pest-eaters like frogs and bats, are on the decline and at risk of disappearing from communities across America. The exact causes are still under investigation, with habitat loss, pesticides, and climate change all key suspects, but it���s clear that many species are reaching their tipping points.

NWF is working to reverse that trend through our Certified Wildlife Habitat program that helps people take personal action on behalf of wildlife. It engages homeowners, businesses, schools, places of worship, parks and other institutions that want to make their communities wildlife-friendly through the creation of sustainable landscapes that provide food, water, shelter and places to raise young for wildlife and require little or no pesticides, fertilizers, and excess watering. There are now nearly 200,000 certified habitats nationwide and to date, 84 communities have been recognized with Community Wildlife Habitat certification and another 50 are actively working towards certification.

The National Wildlife Federation determined our Top 10 Cities for Wildlife by analyzing the total number of NWF Certified Wildlife Habitats per capita in each city to measure citizen engagement. NWF also tallied the number of schools per capita that participate in NWF���s Schoolyard Habitat or Eco-Schools USA program. Finally, NWF looked at the percentage of parkland within a city, using data from the Trust for Public Land���s Park Score Index. Each criterion was given equal weight.

March 10, 2015

Why in Hell Are Tiger Sharks Eating Songbirds?

Cruising for Tweety Bird? (Photo: Albert Kok)

First there was the camera trap image, just last week, of deer raiding songbird nests and eating nestlings.�� Yes, Bambi does that. Feathers and all.

Now comes word that songbirds have been turning up in the stomachs of tiger sharks.�� Would somebody please tell them that this is WRONG, WRONG, WRONG?

Or maybe we’d better just get used to the idea that nature doesn’t behalf as we like to imagine. There’s a reason this column is called “Strange Behaviors.”

Here’s the report from Carol Christian at the Houston Chronicle (Parental Advisory: This article contains the word “tummies.”)

Tiger sharks are known for their voracious appetites, so researchers aren’t surprised when a big one eats something like a manatee or a sea lion.

But woodpeckers, tanagers, yellow throats, king birds, flycatchers, doves?

A University of South Alabama scientist who has been studying Gulf of Mexico tiger sharks for 10 years said he and his colleagues have been surprised at how many backyard birds end up in sharks’ tummies.

Drymon and friend

“We know for sure that they are eating a fair amount of these birds,” said Marcus Drymon, a University of South Alabama assistant professor of marine science and researcher at Dauphin Island Sea Lab, a consortium of 22 Alabama universities.

Beyond its prevalence, researchers know little about how Gulf sharks end up eating songbirds, which has led Drymon

to make a pitch for crowd-source funding on the website experiment.com. His goal is to raise $6,800 to pay for four satellite tagging devices known as SPOT tags.

These high-tech tags would help Drymon determine where tiger sharks are finding their bird meals.

His earlier research has included tagging sharks with $1 plastic tags that require recapture of the same animal — a fairly unlikely outcome — to be most useful, Drymon said.

Since 2006, Drymon has been studying juvenile tiger sharks, including contents of their stomachs. That can be determined by a technique called “gastric lavage,” in which researchers put a hose in the shark’s mouth and catch what comes out in a sieve, he said.

One particular shark about five years ago “coughed up a bunch of feathers,” Drymon said. When DNA analysis showed that the feathers came from terrestrial, or land-based, birds, it piqued the professor’s interest in how this could happen.

The university team catches sharks along the entire coast of Alabama, in water whose depth ranges from a few feet to more than a mile, he said. The area is within 10 to 15 miles of oil platforms, which raises the question of whether the birds are attracted to the oil platform lights, he said.

“This is the preliminary approach I’m taking, just to get baseline information to see if we can understand more about the interaction (of sharks and songbirds),” Drymon said Friday.

Recent public interest in sharks — not as something to be feared but as an important part of ocean ecosystems — has made crowd funding possible, he said.

“This is a new avenue for researchers and scientists to be able to involve the public in their research questions,” he said. “I think it’s going to be the way science moves forward. When the public can have a vested interet, I think it makes the process work best.”

March 6, 2015

Last Chance to See? Tanzania Still Aims for a Serengeti Highway

(Photo: Daryl Balfour/Getty Images)

As wildebeest make their yearly clockwise migration of more than 1,000 miles in the Serengeti, they face epic dangers: lionesses on the hunt, crocodiles lurking in muddy waters, and local villagers out to poach bushmeat. In spite of all this, the 1.3 million ungulates prevail, helping to contribute over a billion tourism dollars every year to Tanzania and keeping the Serengeti ecosystem humming.

For the past five years, though, the animals have been facing a new threat: a road through the park that would connect the Lake Victoria region, west of the Serengeti, with major populations to the east. Scientists and environmentalists have pointed out the risks of allowing speeding cars and fences across the biggest animal land migration on Earth���recently named one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Africa. They also fear that the highway would open the way for further poaching.

Now, a new commentary makes the case that two alternate routes skirting the park would be better socially, economically, and environmentally. The road through the park is ���the worst option of all the routes,��� said Grant Hopcraft, a wildlife researcher at the University of Glasgow and the lead author of the commentary, published last month in Conservation Biology. That route would ���connect the fewest schoolchildren to schools, the least agricultural centers to urban markets, the fewest people to hospitals,��� and do the least in terms of alleviating poverty, Hopcraft said.

Putting a road through the Serengeti would also be an ���ecological nightmare��� for the wildebeest and other wildlife that call the park home, Hopcraft said. While the wildebeest population is strong now, poaching is close to unsustainable, with up to 9 percent of the animals being taken every year. ���We���re right on the cusp,��� he said. He pointed to a 2011 paper predicting that increased access for poachers could reduce the wildebeest population by a third. ���As soon as you put roads in, you provide access to people. And that just leads to a lot more illegal activity.���

A paved road through the Serengeti would also probably lead to fences across the migration route, to prevent car collisions with wildlife, said Hopcraft. That���s what happened, for instance, when the Trans-Canada Highway bisected Canada���s Banff National Park in the 1950s. Fences on either side make the highway ���impenetrable��� for wildlife, Hopcraft said. That ���would separate the wildebeest migration from the only water source that they have in the dry season.��� The current proposal for the road calls only for a gravel upgrade of the current dirt road, and a court ruled last year forbidding Tanzania from installing a paved road within the park itself. Even so, paving would probably soon follow.

The debate about the road has been raging since 2010, when Tanzanian President Jakaya Kikwete made a campaign promise to build the road, probably in pursuit of rural votes. He earned 80 percent of the vote in some of the country���s more remote areas. Hopcraft thinks that the commitment to the road is mostly political, pushed by members of parliament representing communities around the Serengeti.

Some scientists have countered that the case against the proposed highway is overblown, especially in the face of other major threats to the Serengeti and its wildlife. Eivin R��skaft, senior author of the response to Hopcraft���s paper, noted that nearly three quarters of Tanzanians live on less than $2 a day. The road through the park is the only proposal, he argues, that would serve the needs of the Maasai and Sonja people, who live east of the park, and the Kurya agropastoralists living to the west. ���All people��� are entitled to the basic human right of improved infrastructure,��� R��skaft and his co-authors wrote.

���A road is never actually good for the environment,��� R��skaft acknowledged. But alleviating poverty can also reduce the need for people living near the park to illegally kill wildlife in order to survive. In a 2013 paper, R��skaft and his co-authors quoted placards held by villagers that read, ���We are good conservationists; but the poverty caused by poor roads is forcing us to kill the animals in order to survive.���

Other threats to the Serengeti ���are much more serious than this one road,��� R��skaft said. The Mara River, a crucial water source in the Serengeti, originates in the Mau Forest region in Kenya. Massive deforestation there is already affecting the hydrology of the river, which dried up in the Serengeti for the first time a few years ago. He argued that people should focus on climate change and continued poaching, not the road. In addition, Tanzania���s population is due to quintuple by 2100.

There are other grave threats to the park, Hopcraft agreed. But that���s all the more reason not to build the proposed road. ���We���re on a fine line, I think, so the question is, why add another threat?��� Why do so especially when alternative routes would also alleviate poverty without needlessly damaging the Serengeti.

The debate may not be settled until after this year���s elections in October. President Kikwete can���t run again, due to term limits. So the new president will have to decide whether to pursue the road through the park or choose a different route. Meanwhile, if you���ve been thinking of checking out the wildebeest migration, this might be a good time to go. It might be your last chance to see the migration in all its glory���and by supporting the tourism industry around the migration, you will be helping to remind short-sighted politicians just how important the migration is to Tanzania���s economy.

Geoffrey Giller contributed reporting for this column.

Rare Amur Tiger Family–Dad, too–Caught on Film

This remarkable footage comes from the Wildlife Conservation Society. Here’s a composite photo of the animals passing in succession by the camera trap:

And here’s the WCS press release:

NEW YORK (March 6, 2015) ���The Wildlife Conservation Society���s Russia Program, in partnership with the Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Reserve and Udegeiskaya Legenda National Park, released a camera trap slideshow of a family of Amur tigers in the wild showing an adult male with family. Shown following the ���tiger dad��� along the Russian forest is an adult female and three cubs. Scientists note this is

a first in terms of photographing this behavior, as adult male tigers are usually solitary.�� Also included was a photo composite of a series of images showing the entire family as they walked past the a camera trap over a period of two minutes.

WCS Russia Director Dr. Dale Miquelle said, ���Although WCS���s George Schaller documented sporadic familial groups of Bengal tigers as early as the 1960s, this is the first time such behavior has been photographed for Amur tigers in the wild. These photos provide a small vignette of social interactions of Amur tigers, and provide an evocative snapshot of life in the wild for these magnificent animals.���

The photos resulted from a 2014-2015 project establishing a network of camera traps across both Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Reserve and Udegeiskaya Legenda National Park (adjacent protected areas). The goal of the effort is to gain a better understanding about the number of endangered Amur tigers in the region. Although results are still being examined, the biggest surprise was a remarkable series of 21 photographs that showed the entire family of tigers passing the same camera trap (cameras activated by motion) in the span of two minutes.

Svetlana Soutyrina, a former WCS Russia employee and currently the Deputy Director for Scientific Programs at the Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Reserve, set these camera traps and conveyed her elation at the discovery: ���We have collected hundreds of photos of tigers over the years, but this is the first time we have recorded a family together.�� These images confirm that male Amur tigers do participate in family life, at least occasionally, and we were lucky enough to capture one such moment.���

The exact population size of Amur tigers is difficult to estimate. Every ten years an ambitious, range-wide survey is conducted that involves hundreds of scientists, hunters, and volunteers. The results of the most recent of these surveys, undertaken in February 2015, will be released by summer. In 2005, the last time a range-wide survey of Amur tigers was conducted, it was estimated there were 430-500 tigers estimated remaning in the wild.

The WCS Russia Program plays a critical role in monitoring tigers and their prey species in the Russian Far East and minimizing potential conflicts between tigers and human communities. WCS works to save tiger populations and their remaining habitat in nine range countries across Asia.

This program has been supported by the Liz Claiborne and Art Ortenberg Foundation, the Columbus Zoo Conservation Fund, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Rhinoceros & Tiger Conservation Fund, the AZA Tiger Species Survival Plan���s Tiger Conservation Campaign, and the US Forest Service International Programs.

March 5, 2015

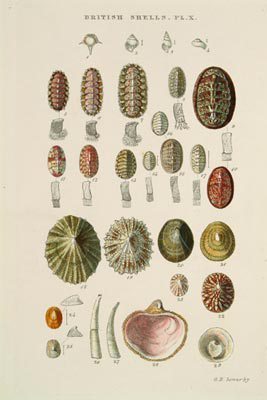

Limpet, What Strong Teeth You Have!

I saw this macrophotograph of a limpet’s incredibly gothic teeth.�� Sorry, make that goethite teeth, apparently incorporating one of the strongest materials known to man.�� Anyway, it made me think about this poem by the impudent rascal Peter Dance:

I dislike the Limpet

always have and always will

watching it needs overtime

all it does is stay quite still

I so dislike the Limpet

to kill it would be easy

perpetrating such a crime

would not make me feel queasy.

Oh I dislike the Limpet

clamped so far as I can tell

on the same old rock all day

just a sucker in a shell.

��To which Dance’s outraged fellow members of the Conchological Society of Great Britain and Ireland responded with a torrent of�� incensed replies (though in one case, including something like a recipe).�� Go, limpet lovers, go!

Meanwhile, here’s the press release on those wicked teeth. (And let’s just overlook the desperate news office writer–and the scientist!–who want to turn limpet teeth into Formula One race cars; this is a topic worthy of an entirely different kind of outraged poem.�� The press release–a triumph of biomimicry wannabes over natural history–also neglects to answer the essential question of why limpets need such strong teeth to eat algae.)�� But I digress:

Limpet teeth might be the strongest natural material known to humans, a new study has found.

Researchers from the University of Portsmouth have discovered that limpets — small aquatic snail-like creatures with conical shells — have teeth with biological structures so strong they could be copied to make

cars, boats and planes of the future.

The study examined the small-scale mechanical behaviour of teeth from limpets using atomic force microscopy, a method used to pull apart materials all the way down to the level of the atom.

Objects of love and loathing

Professor Asa Barber from the University’s School of Engineering led the study. He said: “Nature is a wonderful source of inspiration for structures that have excellent mechanical properties. All the things we observe around us, such as trees, the shells of sea creatures and the limpet teeth studied in this work, have evolved to be effective at what they do.

“Until now we thought that spider silk was the strongest biological material because of its super-strength and potential applications in everything from bullet-proof vests to computer electronics but now we have discovered that limpet teeth exhibit a strength that is potentially higher.”

Professor Barber found that the teeth contain a hard mineral known as goethite, which forms in the limpet as it grows.

He said: “Limpets need high strength teeth to rasp over rock surfaces and remove algae for feeding when the tide is in. We discovered that the fibres of goethite are just the right size to make up a resilient composite structure.

“This discovery means that the fibrous structures found in limpet teeth could be mimicked and used in high-performance engineering applications such as Formula 1 racing cars, the hulls of boats and aircraft structures.

“Engineers are always interested in making these structures stronger to improve their performance or lighter so they use less material.”

The research also discovered that limpet teeth are the same strength no matter what the size.

“Generally a big structure has lots of flaws and can break more easily than a smaller structure, which has fewer flaws and is stronger. The problem is that most structures have to be fairly big so they’re weaker than we would like. Limpet teeth break this rule as their strength is the same no matter what the size.”

The material Professor Barber tested was almost 100 times thinner than the diameter of a human hair so the techniques used to break such a sample have only just been developed.

He said: “The testing methods were important as we needed to break the limpet tooth. The whole tooth is slightly less than a millimetre long but is curved, so the strength is dependent on both the shape of the tooth and the material. We wanted to understand the material strength only so we had to cut out a smaller volume of material out of the curved tooth structure.”

Finding out about effective designs in nature and then making structures based on these designs is known as ‘bioinspiration’.

Professor Barber said: “Biology is a great source of inspiration when designing new structures but with so many biological structures to consider, it can take time to discover which may be useful.”

Journal Reference:

Asa H. Barber, Dun Lu, Nicola M. Pugno. Extreme strength observed in limpet teeth. Royal Society journal Interface, 2015 DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2014.1326

February 28, 2015

A Clownish Way to Make Outdoor Cats Less Deadly

Stare deeply into a cat���s eyes, and you���ll see the unavoidable truth: It is a sleek, stealthy, killing machine. In the United States, outdoor cats kill billions of birds, amphibians, and small mammals every year. Despite a widespread campaign by environmentalists to persuade people to keep their little killers indoors, many cat owners refuse to do so. A new product from a company called Birdsbesafe��won���t entirely fix that problem, but it will help, and two scientific studies suggest that it works. It���s the sort of collar a clown would wear, with a brightly colored frill sticking out all around, making the wearer much easier to see and avoid.

Susan Willson, a Birdsbesafe customer, was hunting around on the Internet when she found the collar. She knew how deadly cats can be. It���s not just that she���s a conservation biologist specializing in birds at St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York. She���s also the owner of two outdoor cats, and one of them, ���the Gorilla,��� is especially adept at killing birds. ���Obviously, the best thing to do is to keep your cat inside,��� Willson said. But when she tried bringing the Gorilla inside, it touched off what she describes as ���a peeing war��� with her three indoor cats.

���At that point, we couldn���t keep him in,��� she said, but euthanizing him was a ���pretty unpalatable��� option. Instead, she ordered the colorful collar, which sells for $10 to $15. It worked���or seemed to work���so well on her cat that Willson set out to conduct a proper scientific study testing whether the collars were as effective as they seemed to be.

Willson focused the study on ���the nastiest of the cats out there,��� the serial killers of the domestic feline world, rejecting from the study cats that only occasionally or never brought birds back to the house. She asked cat owners to put the victims in plastic bags and store them in their freezers. At the end of each season, Willson collected and identified all of the victims���cedar waxwings, purple finches, magnolia warblers, and other birds, as well as small mammals like shrews and even two flying squirrels.

The results, recently published in the journal Global Ecology and Conservation, were impressive: In the spring,��cats with collars killed about a twentieth the number of birds uncollared cats killed, and in the fall,��about a third as many. ���The Birdsbesafe collar is highly effective at reducing bird deaths,��� the study concluded. Did the cats feel it offended their dignity to be dressed up like Bozo the Clown? Apparently not. Most cats adjusted well to the collar���beneath the frill��it���s just a conventional breakaway cat collar���with less than a quarter continually trying to remove it or showing distress, according to their owners.

Another study, in Australia, also found that the collar reduced the number of dead birds brought home by cats, but only by about half. The collar also failed to protect small mammals, which generally lack good color vision. (That might sound like a benefit for cat owners who don���t have much use for mice or other rodents. But in Australia, introduced cats and foxes have already driven 10 percent of the continent���s native mammal species to extinction.)

Birdsbesafe founder Nancy Brennan devised the collar six years ago, after her fianc��’s cat brought home a dead ruffed grouse. Over the years, she���s tried a variety of patterns and colors and says she now has a pretty good sense of what works and what doesn���t. She also readily acknowledges the one method that works best:�� ���If everybody in the world would keep all their cats indoors, I���d be thrilled,��� said Brennan.

Staying indoors is better not just for birds but for the safety of the cats (car strikes are one of the leading causes of death for outdoor cats). It���s also better for human health, because outdoor cats are active carriers of toxoplasmosis and other debilitating diseases. (Check out this site for more information about these diseases and also for methods of allowing cats to be outdoors while also keeping them safely contained.) But Brennan said many of her customers feel that their cats are happier outside, or simply wouldn���t adjust to indoor life. ���I think of Birdsbesafe as a partial solution to a complex problem.���

Asked to comment about the collar, Grant Sizemore, who helps lead the ���Cats Indoors��� campaign for the American Bird Conservancy, replied that the conservancy ���is always in favor of reducing the impacts of outdoor cats on birds and other wildlife.��� But if the collars make cat owners feel comfortable letting their cats outside when they would otherwise keep them in, the collars could result in more predation by cats. He also pointed out that cats can have indirect impacts on birds just by prowling around outside, making birds feed their offspring less and increase their alarm calls.

Here���s the bottom line for owners of outdoor cats: The collar offers a way to do a little less environmental damage and feel less guilty as you transition, with this cat or the next one, to an indoor life. Getting to that point is the best thing you can do for wildlife, your cat, and your health.

Geoffrey Giller contributed reporting for this column.

February 27, 2015

Amphibian Pandemic Hits Madagascar

Chytrid fungus was found on Platypelis pollicaris from Ranomafana National Park.

(Photo: Miguel Vences / TU Braunschweig)

This morning brings very bad news for all of who have admired the astonishingly beautiful and varied amphibians of Madagascar: The deadly chytrid fungus, thought to be responsible for the rapid extinction of more than 100 amphibian species around the world, has arrived in the motherlode: Madagascar. I’ve written here before about attempts to encourage preventive use of a beneficial bacteria with antifungal properties that’s found in some amphibian species.�� Last I heard, the researchers who discovered that bacteria were heading off to see if they could identify a similar strain there. No word yet on how that research is progressing. Meanwhile, here’s the press release:

The chytrid fungus, which is fatal to amphibians, has been detected in Madagascar for the first time. This means that the chytridiomycosis pandemic, which has been largely responsible for the decimation of the salamander, frog and toad populations in the USA, Central America and Australia, has now reached a biodiversity hotspot. The island in the Indian Ocean is home to around 290 species of amphibians that are not found anywhere else in the world. Another 200 frog species that have not yet been classified are also thought to live on the island. Researchers from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) and TU Braunschweig, together with international colleagues, are therefore proposing an emergency plan. This includes monitoring the spread of the pathogenic fungus, building amphibian breeding stations and developing probiotic treatments, say the scientists, writing in Scientific Reports, the acclaimed open-access journal from the publishers of Nature. The entire amphibian class is currently afflicted by a global pandemic that is accelerating extinction at an alarming rate. Although habitat loss caused by human activity still constitutes the main threat to amphibian populations, habitat protection no longer provides any guarantee of amphibian survival. Infectious diseases are now threatening even seemingly secluded habitats. The most devastating of the known amphibian diseases is chytridiomycosis, which is caused by a deadly chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd). The fungus attacks the skin, which is particularly important in amphibians because they breathe through it. A large number of species have already been lost in this way — particularly in tropical Central America, where two-thirds of the colorful harlequin frog species have already been decimated across their entire area of distribution. Bd has now been identified in over 500 amphibian species, 200 of which have seen a significant decline in numbers. The pathogen is therefore classified worldwide as one of the greatest threats to biodiversity. Until now, however, a few islands like Madagascar were thought not to have been affected. The last series of tests from 2005 to 2010 found no trace of the pathogenic fungus there. However, an analysis of the latest series of tests shows that the chytrid fungus also poses a threat to amphibians in Madagascar. “This is sad news for amphibian-lovers around the world,” says Dr Dirk Schmeller of the UFZ, who was involved in analysing the samples. “Firstly, it means that an island that is home to a particularly high number of amphibian species is now at risk. Several hundred species live only on this island. And, secondly, if the pathogen has managed to reach such a secluded island, it can and will occur everywhere.” For the study that has just been published, the research team analysed samples from over 4000 amphibians from 50 locations in Madagascar taken since 2005. Samples from four species of Madagascan frog (Mantidactylus sp.) taken in 2010, and from one Mascarene frog (Ptychadena mascareniensis) taken in 2011 from the remote Makay massif tested positive for the fungus. In samples from 2013 and 2014 the pathogen was found in five different regions. Prof. Miguel Vences from TU Braunschweig says, “The chytrid fungus was found in all four families of the indigenous Madagascan frogs, which means it has the potential to infect diverse species. This is a shock!” The study also shows that the disease affects amphibians at medium to high altitudes, which ties in with observations from other parts of the world, where the effects of the amphibian epidemic have been felt primarily in the mountains. The fact that the fungus has been identified in a very remote part of the island has puzzled the researchers. There is some hope that it may prove to be a previously undiscovered, native strain of the pathogen, which may have existed in the region for some time and have gone undetected because of a lack of samples. In this case, Madagascar’s amphibians may have developed resistance to it. However, further research is needed to confirm this hypothesis before the all-clear can be given. It is also possible that the fungus was brought to the island in crustaceans or the Asian common toad (Duttaphrynus melanostictus), carried in by migratory birds or humans. “Luckily, there have not yet been any dramatic declines in amphibian populations in Madagascar,” Dirk Schmeller reports. “However, the pathogen appears to be more widespread in some places than others. Madagascar may have several strains of the pathogen, maybe even the global, hypervirulent strain. This shows how important it is to be able to isolate the pathogen and analyse it genetically, which is something we haven’t yet succeeded in doing.” At the same time, the researchers recommend continuing with the monitoring programme across the entire country to observe the spread of the disease. The scientists also suggest setting up extra breeding stations for key species, in addition to the two centres already being built, to act as arks, so that enough amphibians could be bred to recolonise the habitats in a crisis. “We are also hopeful that we may be able to suppress the growth of the Bd pathogen with the help of skin bacteria,” says Miguel Vences. “It might then be possible to use these bacteria as a kind of probiotic skin ointment in the future.” A high diversity of microbial communities in the water could also reduce the potential for infection, according to earlier investigations conducted by UFZ researchers and published in Current Biology. The outbreak of amphibian chytridiomycosis in Madagascar puts an additional seven per cent of the world’s amphibian species at risk, according to figures from the Amphibian Survival Alliance (ASA). “The decline in Madagascan amphibians is not just a concern for herpetologists and frog researchers,” says Dr Franco Andreone from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), who is one of the study authors. “It would be a great loss for the entire world.” In the coming months, the scientists therefore plan to work with the government to draw up an emergency plan to prevent this scenario. Reference:

Molly C. Bletz, Gon��alo M. Rosa, Franco Andreone, Elodie A. Courtois, Dirk S. Schmeller, Nirhy H. C. Rabibisoa, Falitiana C. E. Rabemananjara, Liliane Raharivololoniaina, Miguel Vences, Ch�� Weldon, Devin Edmonds, Christopher J. Raxworthy, Reid N. Harris, Matthew C. Fisher, Angelica Crottini. Widespread presence of the pathogenic fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in wild amphibian communities in Madagascar. Scientific Reports, 2015; 5: 8633 DOI: 10.1038/srep08633

February 21, 2015

Endangered Species Now Need Vaccines, Too

(Photo: Julie Larsen Maher ��WCS)

One reason some modern parents persist in their delusional fear of vaccines is that they���ve forgotten the appalling reality of measles and other childhood diseases. But I remember, because measles was the closest I came to dying as a child, in the last gasp of the disease before widespread availability of a vaccine. It has left me with a feverish memory of feeling as if a suffocating pink graft of skin had been stretched across my face (probably because I couldn���t open my eyes) and of being unable to do much more than lie on my back struggling to breathe. Measles killed about 500 American children a year then. I got away cheap.

But this is a column about wildlife, and about a different virus���essentially measles for carnivores���that is causing an equally miserable sickness, often leading to death, in some of the world���s rarest species. Scientists are now proposing to use vaccines to save these animals from the brink of extinction. But figuring out how to vaccinate a scarce, shy, wide-ranging predator can be even more frustrating than trying to talk sense into recklessly misinformed human parents.

As the name suggests, canine distemper virus generally spreads among domestic dogs. In the United States, anybody who takes little Maggie or Jack to the vet for mandatory rabies shots typically gets the canine distemper vaccine too. But in parts of the world with feral dog problems or poor vaccine coverage of domestic dogs, the virus can readily jump to wildlife, and the victims aren���t just members of the canine family. In the mid-1990s, for example, canine distemper roared through the Serengeti, killing more than 1,000 lions over a period of just a few months.

Vaccination may be the single critical step needed to avoid extinction from such epidemics. For instance, fewer than 500 Amur tigers���commonly known as Siberian tigers���are left in eastern Russia and the northeastern corner of China. They face poaching and habitat loss, of course. But scientists recently identified distemper as a factor in the deaths of several of these magnificent animals. The disease causes neurological symptoms, such as loss of orientation, before it kills. It can also make these normally shy cats unafraid of humans. In one case, in 2010, a tiger attacked and killed a fisherman, then relaxed by the side of a road until police shot it. ���As populations continue to decline and fragment,��� said Martin Gilbert, a carnivore health specialist with the Wildlife Conservation Society, ���we are going to see more situations where disease becomes an immediate threat.���

One of the main problems with vaccinating tigers, said Gilbert, is finding them in the first place. The most effective distemper vaccine isn���t available in oral form, so scientists can���t simply leave vaccine-laced bait for tigers to eat. A tiger wandering a 500-square-mile home range could easily miss the bait, in any case. One possible alternative would be to set up a vaccine delivery system at a tree where a tiger periodically scent marks to tell other tigers to keep off its turf. A trigger system not yet devised could then deliver a spray vaccine into the tiger���s nose. More immediately, wildlife managers could routinely administer a vaccine when they trap a tiger to put on a radio collar or when relocating an animal to minimize conflict with humans.

Safety and effectiveness are still critical issues, especially for endangered species. The live vaccine used for pet dogs is already known to be deadly for African wild dogs and red pandas. But vaccine types using a different method to generate distemper antibodies have so far proved less effective than the live vaccine.

Ethiopian wolf

Canine distemper also threatens to wipe out Ethiopian wolves, which have the dubious distinction of being among the world���s rarest canids. These reddish, fox-like wolves persist in Ethiopia���s mountainous highlands. As with wildlife species almost everywhere, the biggest long-term threat to Ethiopian wolves is habitat loss, because of the rapidly expanding human population. But feral dogs are the forerunners of human development, and they are already making distemper and rabies a more immediate threat to the continued existence of this species. In the Bale Mountains, where more than half of the total population of Ethiopian wolves lives, researchers estimated in 2010 that fewer than 300 individuals survive. Since then, 23 carcasses have turned up, and 56 individuals have gone missing, probably due to a distemper outbreak.

���You could very realistically see local extinctions��� caused by the distemper virus, especially for some of the smaller populations of wolves, according to Christopher Gordon, a researcher for the Zoological Society of London, who will soon publish research on a distemper vaccine for these wolves. The hazard of local extinctions also applies to tigers. A recent study led by Gilbert noted that more than half the world���s tigers now live in populations of 25 individuals or fewer���and that even a conservative distemper infection scenario increased by 65 percent the likelihood that such a population would go extinct. Most tigers, moreover, live in India, which has a huge feral dog population.

What can people do? Obviously, you should keep any pet on a proper vaccination schedule. You should also support programs to remove���that is, euthanize���feral dog populations, because they are a threat to both wildlife and humans.

This is an emotional subject, so here���s a quick story about the emotions on the other side of the issue.

At about the same time distemper was wiping out lions in the Serengeti, I visited with a researcher in Botswana on a long-term study of African wild dogs, a beautiful but beleaguered species, then down to about 5,000 animals. The researcher had named all the dogs in one study pack after different beers���something he wasn���t getting to drink much during field work. One day, a young male named Newkie (for Newcastle) wandered off in search of a female.

By the time he eventually returned home, his entire family had been killed off by distemper or rabies picked up from domestic dogs. Newkie spent the next few months wandering in the old Beer Pack home range, taking solace in the scent marks of his kin, which lingered like ghosts for months afterwards.

That���s a terrible fate to inflict on any animal���much worse than what happened to me with measles. But keep both experiences in mind���the loss of love ones and the trauma of disease. Then run out and get your kids vaccinated. Also bear in mind that what happens to wildlife affects their well-being, too. With ���the falloff in vaccination of children,��� said Gilbert, ���there���s a niche there for another morbillivirus,��� such as measles or distemper. Theoretically, he said, canine distemper, or another related virus, could start showing up in people.

By Richard Conniff, with reporting by Geoffrey Giller.

February 18, 2015

Why Genius in the Lab Needs Genius in the Field

Ceci n’est pas un joke.

We praise the almost mythical image of the lone genius.�� But we cannot live without other people, and it is doubtful that such lone geniuses exist even in the ivoriest of ivory towers.

Heather Tallis, a lead scientist at The Nature Conservancy, has an engaging new essay about the need for the unacknowledged but at least equal genius required to make great scholarship yield great changes in the field.�� The example she cites interests me because I have been writing here lately about how to fix the problem we face when a third of the seafood on our dinner plates is illegally caught. (See here, and here, and here.)

This is an excerpt from Tallis’s essay:

But the single-genius model is less helpful for fixing most environmental and social problems ��� the solutions to which often lie not in individual brilliance, but involve catalyzing and coordinating small innovative actions among thousands or even millions of people.

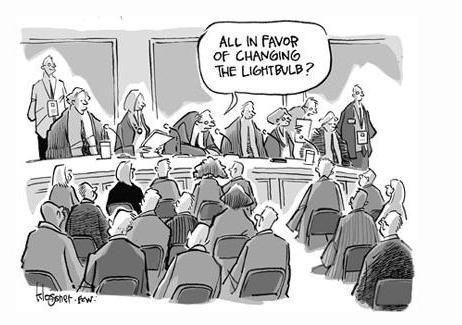

The light bulb was a great invention, but it didn���t change the world until there was a power grid providing electricity to every house. Both the bulb and the grid were brilliant inventions, but we hear a lot more about Thomas Edison (the bulb) than we do about whoever invented the grid (the person is so not-famous I can���t even figure out who it was).

Here���s an environmental example of the same situation from some of my colleagues. Fishery stock assessment and management is a classic realm of sophisticated, advanced science. Rigorous models have tens if not hundreds of parameters, and require Ph.D level scientists to run and interpret.

It���s costly, too: The collection of data on stocks to inform these assessments can run in the hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars. The best assessments use large research vessels and whole teams of university professors and government scientists. These resource-heavy requirements are part of the reason that 95% of the world���s fisheries regularly go un-assessed.

For example, Atlantis is arguably the world���s best stock assessment model, and Beth Fulton, the CSIRO scientist in Australia who developed it, is truly brilliant. The model is a masterpiece of sophistication and complexity and it has had staggering success as far as these kinds of complex models go.

But it���s been applied in 20 marine fisheries globally���.of the 15,000+ fisheries that need to be assessed.

To get all fisheries globally on stable footing, we need

an infusion of the applied kind of brilliance, too. Capacity limitations in many fisheries will mean they will crash before someone comes around who could apply a model like Atlantis to their management.

There���s a small group of scientists taking a very different approach, in another version of what I see as true brilliance. Jeremy Prince (an academic), Noah Ideching (a Pew Fellow) and Steven Victor (an NGO scientist) are starting in Palau: small, yes, but promising.

Instead of requiring complex, integrated foodweb ecosystem models and large research vessels, they are piloting a method that requires a knife, a ruler and some fishermen. You can also just walk into a fish market and use it.

The trick here is that the science builds on existing data ��� reams of it, on the life history traits of different species and size at reproductive maturity. So Prince, Ideching and Victor are relying on the brilliance of tens of point-of-light scientists who have come before and done the pure science to define how fish grow and when they become reproductively mature.

The equally brilliant and novel advance here is synthesizing that knowledge and applying it in an entirely different way that���s simple and effective.

Basically, you cut open a fish, and measure its gonads.

Doing this across a decent sample size reveals how many fish being caught are in their reproductive prime, and can help fishermen to adjust the size of the fish they are keeping to keep more baby-makers in the water.

This method is the ���grid��� for fishery stock assessment. It takes the discoveries of top-notch scientists and uses the brains of other top-notch scientists to put them in the hands of thousands of fishermen.

Now, this method is not going to get published in Nature. These scientists are unlikely to win a prize from a prestigious scientific society.

But I think they should. This is true brilliance. It���s just a different kind from that which we normally celebrate.

NGO scientists are often the first to call each other out as second-rate. And yes, crappy science happens at NGOs, but it also happens at universities. And yes, brilliant science is done at universities, but it���s also done at NGOs. We need to change the stereotypes in the natural sciences, which don���t match the facts.

Read Tallis’s complete essay here.