Richard Conniff's Blog, page 37

December 9, 2014

Ranchers Kill Wolves & It Just Makes Their Livestock Losses Worse

Well, we always knew there was an irrational, even sociopathological element in the war against wolves. Now a careful study of 25 years of data from Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho reveals that it disrupts the hierarchy of wolf packs and actually increases the rate of attacks on wildlife.

Here’s the press release:

Washington State University researchers have found that it is counter-productive to kill wolves to keep them from preying on livestock. Shooting and trapping lead to more dead sheep and cattle the following year, not fewer.

Writing in the journal PLOS ONE, wildlife biologist Rob Wielgus and data analyst Kaylie Peebles say that, for each wolf killed, the odds of more livestock depredations increase significantly. The trend continues until 25 percent of the wolves in an area are killed. Ranchers and wildlife managers then see a “standing wave of livestock depredations,” said Wielgus.

That rate of wolf mortality is also “unsustainable and cannot be carried out indefinitely if federal relisting of wolves is to be avoided,” they note.

The gray wolf was federally listed as endangered in 1974. During much of its recovery in the

Wildlife biologist Rob Wielgus (Photo: Kay Morris)

northern Rocky Mountains, government predator control efforts have been used to keep wolves from attacking sheep and livestock. With wolves delisted in 2012, sport hunting has also been used. But until now, the effectiveness of lethal control has been what Wielgus and Peebles call a “widely accepted, but untested, hypothesis.”

Their study is the largest of its kind, analyzing 25 years of lethal control data from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services Interagency Annual Wolf Reports in Montana, Wyoming and Idaho. The researchers found that killing one wolf increases the odds of depredations 4 percent for sheep and 5 to 6 percent for cattle. If 20 wolves are killed, livestock deaths double.Work reported in PLOS ONE last year by Peebles, Wielgus and other WSU colleagues found that lethal controls of cougars also backfire, disrupting their populations so much that younger, less disciplined cougars attack more livestock.

Still, Wielgus did not expect to see the same result with wolves.

“I had no idea what the results were going to be, positive or negative,” he said. “I said, ‘Let’s take a look at it and see what happened.’ I was surprised that there was a big effect.”

Wielgus said wolf killings likely disrupt

the social cohesion of the pack. While an intact breeding pair will keep young offspring from mating, disruption can set sexually mature wolves free to breed, leading to an increase in breeding pairs. As they have pups, they become bound to one place and can’t hunt deer and elk as freely. Occasionally, they turn to livestock.

Under Washington state’s wolf management plan, wolves will be a protected species until there are 15 breeding pairs for three years. Depredations and lethal controls, legal and otherwise, are one of the biggest hurdles to that happening.

Wolves from the Huckleberry Pack killed more than 30 sheep in Stevens County, Wash., this summer, prompting state wildlife officials to authorize killing up to four wolves. An aerial gunner ended up killing the pack’s alpha female. A second alpha female, from the Teanaway pack near Ellensburg, Wash., was illegally shot and killed in October.

That left three breeding pairs in the state.

As it is, said Wielgus, a small percentage of livestock deaths are from wolves. According to the management plan, they account for between .1 percent and .6 percent of all livestock deaths—a minor threat compared to other predators, disease, accidents and the dangers of calving.

In an ongoing study of non-lethal wolf control, Wielgus’s Large Carnivore Conservation Lab last summer monitored 300 radio-tagged sheep and cattle in eastern Washington wolf country. None were killed by wolves.

Still, there will be some depredations, he said. He encourages more non-lethal interventions like guard dogs, “range riders” on horseback, flags, spotlights and “risk maps” that discourage grazing animals in hard-to-protect, wolf-rich areas.

“The only way you’re going to completely eliminate livestock depredations is to get rid of all the wolves,” Wielgus said, “and society has told us that that’s not going to happen.”

December 7, 2014

How An Attorney General Sold Out to Corporate Paymasters

Scott Pruitt, Attorney General and Corporate Shill (Not in that Order)

Everybody in the United States should be reading and talking about Eric Lipton’s terrific story in today’s New York Times. It’s about how American democracy is being sold out by government officials who are supposed to be protecting the interests of the people but instead sell their services to the highest corporate bidder. It’s a deeply serious story, but, honestly I also really love the part where the lobbyist tells the Attorney General of the State of Oklahoma, one Scott Pruitt, to bark. And, of course, Mr. Pruitt barks.

Woof, woof. I am laughing as we slide rapidly down to government of the corporation, by the corporation, and for the corporation. Here’s an excerpt:

[Oil industry lobbyist Andrew P.] Miller made it his job to promote Mr. Pruitt nationally, both as a spokesman for the Rule of Law campaign and as the president of the Republican Attorneys General Association.

“I regard the general as the A.G. best suited to take this lead on this question of federalism,” Mr. Miller wrote to Mr. Pruitt’s chief of staff in April 2012. “The touchstone of this initiative would be to organize the states to resist federal ‘overreach’ whenever it occurs.”

To Mr. Miller, having Mr. Pruitt as an advocate fit a broader strategy. He wanted state attorneys general to band together the way they did when they challenged the health care law in 2010. In that effort, they hired a major national corporate law firm, Baker Hostetler, to argue the case, with much of the bill being paid through donations from executives at corporations that oppose the law.

In his initial appeal to Mr. Pruitt, Mr. Miller insisted that his approach was not “client driven.” But he soon began to name individual clients — TransCanada and Pebble Mine in Alaska — that he wanted to include in the effort. The E.P.A. has held up the Pebble Mine project, which could potentially yield 80 billion pounds of copper, after concluding it would “threaten one of the world’s most productive salmon fisheries.”

“This strike force ought to take the form of a national state litigation team to challenge the E.P.A.’s overreach,” Mr. Miller said in an email to Mr. Pruitt’s office. “Like the Dalmatian at the proverbial firehouse,

it could move out smartly when the alarm sounded.”

A Call to ArmsMr. Miller’s pitch to Mr. Pruitt became a reality early last year at the historic Skirvin Hilton Hotel in Oklahoma City, where he brought together an extraordinary assembly of energy industry power brokers and attorneys general from nine states for what he called the Summit on Federalism and the Future of Fossil Fuels.

The meeting took place in the shadow of office towers that dominate Oklahoma City’s skyline and are home to Continental Resources, a leader in the nation’s fastest-growing oil field, the Bakken formation of North Dakota, as well as Devon Energy, which drilled 1,275 new wells last year.

More liberal attorneys general, such as Douglas F. Gansler, Democrat of Maryland, did not participate.

“Indeed, General Gansler would in all likelihood try to hijack your summit,” Mr. Miller wrote to Mr. Pruitt in an email. “At best you would be left to preside over a debate, rather than a call to arms.”

Read the rest of this said tale here, and you will come away understanding why we can’t clean up our air, protect salmon, slow global warming, or otherwise make this a decent country for anyone but the one percent to live.

December 5, 2014

Climate Change Now: “Ticks Cover their Bodies Like Shingles on a Roof”

They call them “ghost moose.” These pale beasts have lately come to haunt forests across the northern United States. But they aren’t at all like the revered Kermode bears of Canada, which owe their cream coloring to genetics or, as some First Nations believe, to supernatural powers. Ghost moose are white because of winter ticks. More precisely, they are white because climate change makes them vulnerable to winter ticks. That may sound crazy at first. For most of us, climate change can seem like an abstraction, with consequences that we may not have to face till some vague time decades or centuries in the future. But the spectacle of a moose with thousands upon thousands of engorged winter ticks clinging to its body has a way of making it seem painfully here and now.

They call them “ghost moose.” These pale beasts have lately come to haunt forests across the northern United States. But they aren’t at all like the revered Kermode bears of Canada, which owe their cream coloring to genetics or, as some First Nations believe, to supernatural powers. Ghost moose are white because of winter ticks. More precisely, they are white because climate change makes them vulnerable to winter ticks. That may sound crazy at first. For most of us, climate change can seem like an abstraction, with consequences that we may not have to face till some vague time decades or centuries in the future. But the spectacle of a moose with thousands upon thousands of engorged winter ticks clinging to its body has a way of making it seem painfully here and now.

“The ticks cover their bodies like shingles on a roof,” said Kristine Rines, a wildlife biologist and leader of the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department’s Moose Project. “Fat, ugly shingles with little creepy wavy legs.”

What’s climate change got to do with it? In the past, winter ticks (Dermacentor albipictus) were mostly found on white-tailed deer, which live in slightly warmer climes farther south. These ticks typically lay their eggs in the spring, and the young develop during the summer. By fall, clusters of tick larvae are waiting in the undergrowth, and when a deer brushes against them, the young ticks latch on. But the deer are used to it. They groom the ticks off themselves while they’re still young and easy to dislodge.

Not so for moose. They have no history with this horrific nuisance and don’t seem to make any attempt to groom the off the immature ticks from October until February. By then, it’s too late: the adult ticks are too appallingly numerous to do much about it. The moose only get relief in April, when the ticks generally drop off to renew their reproductive cycle, laying eggs for the next generation.

(Photo: Daniel Berna)

In the past, any winter tick that happened to fall off a moose would find itself dropped onto snow-covered ground, where it would freeze or make for a highly visible snack for passing birds. But with shorter, warmer winters, it’s now normal for snow to melt by April in Vermont and New Hampshire. That lets winter ticks survive and reproduce there, as well as in other states along the southern part of the moose’s range, including Montana, Idaho, and Minnesota.

Even more ticks pile onto the moose the following winter. In their efforts to dislodge these pests, the moose rub so aggressively at their dark brown outer guard hairs that they break them off close to the root, leaving only the whitish stubs behind. Moose with especially bad infestations—as many as 50,000 ticks—may remove 80 percent or more of their outer hair layer, giving them their ghostlike appearance. The moose often can’t survive the cold without their winter coats. Or they die from anemia caused by the loss of so much blood. (Female ticks swell to the size of small grapes when fully engorged). Thanks in part to winter ticks, moose populations in many states are now declining,

Does that matter? Moose numbers have fluctuated wildly over the past few hundred years. They had practically vanished from New Hampshire and Vermont by the 1890s, because of hunting and conversion of forests to farmland. Then in the 20th century, forests reclaimed farm fields in northern New England, and moose populations rebounded so successfully that fatal traffic accidents became commonplace. The moose also made themselves unwelcome by knocking down livestock fencing and demolishing maple syrup tubing as they moved through the forests.

Moose hunting resumed for a while, to bring populations down to manageable densities. But New Hampshire and Vermont have lately begun to cut the number of moose hunting permits they issue, because ticks are now killing so many moose. That represents a significant loss of income for fish and game departments, which depend on permit fees to fund their conservation work, and also to local economies that benefit from hunting.

New Hampshire’s Kristine Rines doesn’t expect winter ticks to threaten the long-term survival of moose in her state. As moose densities decline, so will mortality from winter ticks. But climate change is also bringing other threats to the northern forests, including brainworm from deer extending their range northward into moose habitat. Moose infected with this parasite become disoriented, often turning repeatedly in circles before they eventually become paralyzed and die. That has caused “dramatic moose reduction, if not extinction, in several areas in North America,” she said, including parts of Minnesota, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick.

To Rines, the solution is relatively clear, if not easy to achieve. “We have to wrap our arms around climate change,” she said. People tell her that there’s nothing to be done about it—or worse, that it’s just a myth, and “It makes me want to retire,” she said, with a bitter laugh.

But Rines knows that there is plenty that people and governments can do to address climate change. She also knows that it’s not just the moose that are at risk: The purple finch—New Hampshire’s state bird—has been shifting its range northward, out of the state. The threatened Bicknell’s thrush depends on high-elevation spruce fir forests, common in New Hampshire but also threatened by the changing climate. Sugar maple sap has already begun losing its sweetness, and some researchers believe sugar maples could disappear from New England altogether.

So think of those ghost moose as a harbinger, even the ghost of Christmas yet to come. A few inches of sea level rise, or a couple of degrees change in average temperature may not seem like much. But when we think of a lone moose stripped bare in the winter forest, or circling in confused agony, and when we envision a New Hampshire with no moose at all, or a Vermont without sugar maples, then maybe each of us can dimly begin to hear the Jacob Marley’s chains we all drag behind us. What we are facing is a future in which we have lost not just our regional identities, but also our souls.

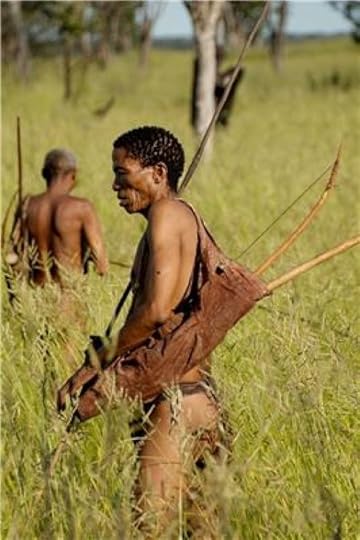

Proud of Your Ancestry? Namibia’s Khoisan Have You Beat

One of the great experiences of my life was to travel with Khoisan hunters as they tracked wildlife in northwestern Namibia. They didn’t dress all that differently from other Namibians. (That traditional half-naked look in the photograph is something they seem to do now mainly at the behest of photographers.) But, lord, they were different: For me, it was like being illiterate among scholars who had devoted their lives (and hearts and souls) to studying the subtle nuances of the footprint.

One of the great experiences of my life was to travel with Khoisan hunters as they tracked wildlife in northwestern Namibia. They didn’t dress all that differently from other Namibians. (That traditional half-naked look in the photograph is something they seem to do now mainly at the behest of photographers.) But, lord, they were different: For me, it was like being illiterate among scholars who had devoted their lives (and hearts and souls) to studying the subtle nuances of the footprint.

I remember one night when an African wild cat had come into the camp and stolen the precious organ meat from a kill, which the Khoisan had hung up a tree for safekeeping. When they discovered their loss in the morning, the two hunters simply followed the trail back to the cat’s lair, and re-claimed their meat. But, sorry, let me get to the point.

A new genetic study has revealed just how different, and ancient, the Khosan lineage really is. And yet they were the majority of the human species just 20,000 years ago, meaning their evolution was our evolution. Here’s an excerpt from the press release:

Through advanced computation analysis, a team from Nanyang Technological University (NTU Singapore) and Penn State University found that these Southern African Khoisan tribespeople are genetically distinct not only from Europeans and Asians, but also from all other Africans.

The team also found that there are individuals of the Khoisan population whose ancestors did not interbreed with any of the other ethnic groups for the last 150,000 years and that Khoisan was the majority group of living humans for most of that time until about 20,000 years ago.

Their findings mean it is now possible to use genetic sequencing to reveal the ancestral lineage of any ethnic group even up to 200,000 years ago, if non-admixed individuals are found, like in the case of the Khoisan. This will show when in history there have been important genetic changes to an ancestral lineage due to

intermarriages or geographical migrations that may have occurred over the centuries.

“Khoisan hunter/gatherers in Southern Africa have always perceived themselves as the oldest people,” said Prof. Stephan Christoph Schuster, an NTU scientist at the Singapore Centre on Environmental Life Sciences Engineering (SCELSE) and a former Penn State University professor.

“Our study proves that they truly belong to one of mankind’s most ancient lineages, and these high quality genome sequences obtained from the tribesmen will help us better understand human population history, especially the understudied branch of mankind such as the Khoisan.

“The new data gathered will also enable scientists to better understand how the human genome has evolved and hopefully lead to more effective treatment options for certain genetic diseases and illnesses.”

Of the five tribesmen who were the oldest members of the Ju/’hoansi tribe and other tribes living in protected areas of northwest Namibia, two individuals were found to have a genome which had not admixed with other ethnic groups.

The Ju/’hoansi tribe was made famous in the 80s and 90s by the box-office hit movie series “The Gods Must Be Crazy.” The main character of the series was a hunter/gatherer tribesman, played by Nǃxau, a bushman.

The research paper’s first author, Dr Hie Lim Kim, a SCELSE senior research fellow, said “it was very surprising that this group apparently did not intermarry with non-Khoisan neighbours for thousands of years.” This is because the Khoisan peoples and the rest of modern humanity shared their most recent common ancestor around 150,000 years ago.

The current Khoisan culture and tradition, where marriage occurs either among Khoisan groups or results in female members leaving their tribes after marrying non-Khoisan men, appears to be long-standing.

“A key finding from this study is that even today after 150,000 years, single non-admixed individuals or descendants of those who did not interbreed with separate populations can be identified within the Ju/’hoansi population, which means there might be more of such unique individuals in other parts of the world,” added Dr Kim.

December 3, 2014

Travel Hell? Whales Stuck in Middle East for 70,000 Years

A whale named Spitfire (Photot: © Tobias Friedrich)

As I read this, these humpbacks extended their range into the Arabian Sea 70,000 years ago, and then got bottled up there by some temporary glacial barrier, or long-term thermal barrier. Even if they could travel elsewhere now, they don’t and their numbers are down to just 100 individuals. It may be that they stick to the Arabian Sea because, as a result of their lengthy isolation, their reproductive cycle got out of whack with the rest of the humpback world.

Or maybe–could it be–they just like it there?

Here’s the press release:

Scientists from WCS (Wildlife Conservation Society), the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), the Environment Society of Oman, and other organizations have made a fascinating discovery in the northern Indian Ocean: humpback whales inhabiting the Arabian Sea are the most genetically distinct humpback whales in the world and may be the most isolated whale population on earth. The results suggest they have remained separate from other humpback whale populations for perhaps 70,000 years, extremely unusual in a species famed for long distance migrations.

(Photo credit: Darryl MacDonald)

Known for its haunting songs and acrobatics, the humpback whale holds the record for the world’s longest mammal migration; individuals have been tracked over a distance of more than 9,000 kilometers between polar feeding areas and tropical breeding areas.

“The epic seasonal migrations of humpbacks elsewhere are well known, so this small, non-migratory population presents a wonderful and intriguing enigma,” said WCS researcher and study co-author Tim Collins. “They also beg many questions: how and why did the population originate, how does it persist, and how do their behaviors differ from other humpback whales?”

The study appears in the online journal PLOS ONE. The authors include: Cristina Pomilla of the Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics at the American Museum of Natural History; Ana R. Amaral of the Universidade de Lisboa; Tim Collins of WCS; Gianna Minton of WWF-Gabon; Ken Findlay of the University of Pretoria; Matthew Leslie of AMNH and WCS; Louisa Ponnampalam of the University of Malaysia; Robert Baldwin of the Environment Society of Oman; and Howard Rosenbaum, Director of the Ocean Giants Program at WCS.

Previous studies on humpback whales, including several published by WCS, have revealed a great deal of population structure among humpback whales of the Northern Hemisphere and many areas of the Southern Hemisphere, particularly on breeding grounds. At the ocean basin scale, scientists are gaining an understanding of humpback whale gene flow, including in the Southern Indian Ocean. The dynamics and movements of animals in the Arabian Sea, however, are poorly understood.

“We have invested lots of energy working to clarify the population structure of several large whale species around the world,” said Dr. Howard Rosenbaum, Director of WCS’s Ocean Giants Program and senior author on the study. “The levels of genetic differences for Arabian Sea humpback whales are particularly striking; they are the world’s most distinct population of humpback whales and might even shed some light on the environmental factors that shape cetacean populations.”

To assess the origins of the Arabian Sea humpback whale population, the research team examined nuclear and mitochondrial DNA extracted from tissue samples that were collected as biopsies from 47 individual whales. The data were then compared to existing data sets from humpback whales in both the Southern Hemisphere and the North Pacific. All of the sampling was conducted in the Sultanate of Oman, a known hotspot for the animals. “We couldn’t have conducted this study without the magnificent support of the Sultanate of Oman, and particularly our partnership with the Environment Society of Oman,” said Collins

The authors have speculated that the 70,000-year separation might be linked to various glacial episodes in the late Pleistocene Epoch and associated shifts in the strength of the Indian Monsoon. The separation is likely reinforced by breeding cycles that are asynchronous; humpback whales in the Arabian Sea breed on a Northern Hemisphere schedule, whereas the closest whale populations in the Western Indian Ocean (below the equator) breed during a different season. The population’s known range includes Yemen, Oman, the UAE, Iran, Pakistan and India, and possibly the Maldives and Sri Lanka.

Other lines of evidence support the genetic data, including an absence of photo-identified individuals from the Arabian Sea appearing with whales in theWestern Indian Ocean (and vice versa). Arabian humpbacks also have far fewer barnacle scars than Southern Hemisphere whales, and a total absence of cookie-cutter shark bites (such bites are common on humpbacks found south of the equator). Future work will explore the possible causal mechanisms for the population’s isolation.

The genetic study also revealed a comparatively low level of genetic diversity when compared to other humpback populations, as well as the signatures of both distant and recent genetic bottlenecks, events caused by population declines. The most recent bottleneck may be due to illegal whaling; during two very short periods in 1965 and 1966 Soviet whalers killed 242 humpback whales in the Arabian Sea (39 of the captured females were also pregnant), a potentially devastating loss for a small population. Today, the major and most urgent concern for this population is lethal entanglement in fishing gear and ship strikes. “This latest study strengthens the evidence that we have an urgent conservation priority to attend to, not just in Oman, but with partners across range states,” said HH Sayyida Tania Al Said of the Environment Society of Oman. “We are working with stakeholders in Oman to advocate for the importance of conservation of this species and its consideration in development plans. We are also seeking to work with international partners to improve conservation of marine mammals in the wider Arabian Sea, including participation in a regional humpback whale conservation initiative.”

“The Arabian Sea humpback whales are the world’s most isolated population of this species and definitely the most endangered,” added Rosenbaum. “The known and growing risks to this unique population include ship strikes and fishing net entanglement, threats that could be devastating for this diminished population; we need to see increased regional efforts to provide better protection for these whales.”

The current best estimate of population size for Arabian Sea humpbacks is fewer than 100 individuals although this is based solely on the work conducted in Oman. The status of the population is reviewed annually by the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission. The authors of the study recommend that the population be uplisted from “Endangered” to “Critically Endangered” on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species.

Manhattan Is Actually Run by Ants (Also Maggots)

You heartless and cynical New Yorkers probably thought rats and pigeons did all the garbage removal from your streets. But it turns out you also owe a great big “thank you”–plus a smiley face and an exclamation point–to ants.

Also other insect forms.

I am just so disappointed that the authors of this study, who came from North Carolina to find the maggots in the Big Apple, did not include any photos with this press release (UPDATE: One of the co-authors, Matt Shipman, just sent photos, posted below):

In the city that never sleeps, it’s easy to overlook the insects underfoot. But that doesn’t mean they’re not working hard. A new study from North Carolina State University shows that insects and other arthropods play a significant role in disposing of garbage on the streets of Manhattan.

“We calculate that the arthropods on medians down the Broadway/West St. corridor alone could consume more than 2,100 pounds of discarded junk food, the equivalent of 60,000 hot dogs, every year — assuming they take a break in the winter,” says Dr. Elsa Youngsteadt, a research associate at NC State and lead author of a paper on the work.

“This isn’t just a silly fact,”

Youngsteadt explains. “This highlights a very real service that these arthropods provide. They effectively dispose of our trash for us.”

The researchers were in the midst of a long-term study of urban insects when Hurricane Sandy struck NYC in 2012. In spring 2013, they expanded their study to look at whether Sandy had affected the behavior of these insect populations.

The research team sampled arthropods — such as insects and millipedes — in street medians and parks in Manhattan to measure the biodiversity at those sites. The researchers also wanted to see how much garbage those arthropods consumed and whether they consumed more in some places than in others. One hypothesis was that in areas with more biodiversity, insects would consume more garbage.

Who knew a Broadway median could look this good? (Answer: The ants)

To see how much the arthropods ate, the researchers put out carefully measured amounts of junk food — potato chips, cookies and hot dogs — at sites in street medians and city parks. Researchers placed two sets of food at each site. One set was placed in a cage, so only arthropods could reach the food; the second set was placed in the open, where other animals could also eat it. After 24 hours, the scientists collected the food to see how much was eaten.

The researchers found that Hurricane Sandy had no measurable impact on food consumption by arthropod populations in New York, which was somewhat surprising since many of the study sites had been flooded with brackish water.

The bigger surprise was that arthropod populations in medians ate two to three times more junk food than those in parks — even though there was less biodiversity in the medians.

“We think this is because one of the most common species in the medians was the pavement ant (Tetramorium species), which is a particularly efficient forager in urban environments,” Youngsteadt says.

In addition, by comparing food consumption inside and outside of the sample cages, the researchers showed that other animals — such as rats and pigeons — were also eating the junk food.

“This means that ants and rats are competing to eat human garbage, and whatever the ants eat isn’t available for the rats,” Youngsteadt explains. “The ants aren’t just helping to clean up our cities, but to limit populations of rats and other pests.”

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by North Carolina State University. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

Journal Reference:

Elsa Youngsteadt, Ryanna C. Henderson, Amy M. Savage, Andrew F. Ernst, Robert R. Dunn and Steven D. Frank. Habitat and species identity, not diversity, predict the extent of refuse consumption by urban arthropods. Global Change Biology, December 2014 DOI: 10.1111/gcb.12791

Birds May Carry New Diseases to a Warming North

Glaucous gulls and polar bears on the carcass of a dead whale may be sharing more than a meal (Photo: USGS)

We’ve all heard about insects moving northward and bringing dengue fever, chikungunya virus, and other diseases with them. But the threat from birds, particularly to other wildlife species, hadn’t occurred to me before. Here’s a press release about a disconcerting new study in F:

When wild birds are a big part of your diet, opening a freshly shot bird to find worms squirming around under the skin is a disconcerting sight. That was exactly what Victoria Kotongan saw in October, 2012, when she set to cleaning two of four spruce grouse (Falcipennis canadensis) she had taken near her home in Unalakleet, on the northwest coast of Alaska. The next day, she shot four grouse and all four harbored the long, white worms. In two birds, the worms appeared to be emerging from the meat.

Kotongan, worried about the health of the grouse and the potential risk to her community, reported the parasites to the Local Environmental Observer Network, which arranged to have the frozen bird carcasses sent to a lab for testing. Lab results identified the worms as

the nematode Splendidofilaria pectoralis, a thinly described parasite previously observed in blue grouse (Dendragapus obscurus pallidus) in interior British Columbia, Canada. The nematode had not been seen before so far north and west. Though S. pectoralis is unlikely to be dangerous to people, other emerging diseases in northern regions are not so innocuous.

Animals are changing their seasonal movements and feeding patterns to cope with the changing climate, bringing into close contact species that rarely met in the past. Nowhere is this more apparent than the polar latitudes, where warming has been fastest and most dramatic. Red foxes are spreading north into arctic fox territory. Hunger is driving polar bears ashore as sea ice shrinks. Many arctic birds undertake long migratory journeys and have the mobility to fly far beyond their historical ranges, or extend their stay in attractive feeding or nesting sites.

With close contact comes a risk of infection with the exotic parasites and microorganisms carried by new neighbors, and so disease is finding new territory as well. Clement conditions extend the lifecycles of disease carrying insects, and disease-causing organisms. Migratory birds can take infectious agents for rides over great distances. In November 2013, Alaska Native residents of St. Lawrence Island, in the Bering Sea, alerted wildlife managers to the deaths of hundreds of crested auklets, thick-billed murres, northern fulmars and other seabirds, caused by an outbreak of highly contagious avian cholera (Pasteurella multocida).

“It’s the first time avian cholera has shown up in Alaska,” said Caroline Van Hemert, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Anchorage, Alaska. “St. Lawrence Island is usually iced in by November, but last year we had a warm fall and winter in Alaska. We don’t know for sure that open water, climate, and high-densities of birds contributed to the outbreak, but it coincided with unusual environmental conditions.”

Circumstantial evidence collected by researchers and local observers is pointing toward a surge of infectious disease in the northern latitudes, but scanty baseline data makes interpretation of current trends uncertain. Van Hemert and colleagues review the state of our knowledge of emerging disease in northern birds and effects on wildlife and human health, discussing strategies for cooperative programs to fill in information gaps in the December issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

Story Source:The above story is based on materials provided by Ecological Society of America. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

Journal Reference:

Caroline Van Hemert, John M Pearce, Colleen M Handel. Wildlife health in a rapidly changing North: focus on avian disease. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2014; 12 (10): 548 DOI: 10.1890/130291

December 2, 2014

Are Namibia’s Rhinos Now Under Siege?

Early this year in The New York Times, I wrote an op-ed in praise of Namibia’s work in restoring populations of endangered black rhinos and, more important, in avoiding the poaching nightmare taking place next door in South Africa (on track to lose 1100 rhinos this year). Here’s part of that piece:

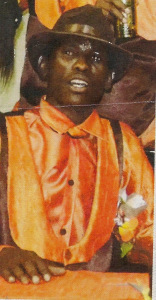

Daniel Alfeus //Hawaxab– aka Boxer

Namibia is just about the only place on earth to have gotten conservation right for rhinos and, incidentally, a lot of other wildlife. Over the past 20 years, it has methodically repopulated one area after another as its rhino population has steadily increased. As a result, it is now home to 1,750 of the roughly 5,000 black rhinos surviving in the wild … In neighboring South Africa, government officials stood by haplessly as poachers slaughtered almost a thousand rhinos last year alone. Namibia lost just two.

But a new report says the poaching situation there has dramatically worsened. Here’s how the story begins, from Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism:

The air over Sesfontein this time of year is usually a peculiar metallic hue, tinged by the talcum-fine dust whipped by the harsh desert wind blowing from the Skeleton Coast, 250 kilometres away to the west.

But today, the white heat seemed bleaker than ever, and another metallic taste stirred in the air: that of blood, redolent of greed and betrayal, of witchcraft and a strange death by anthrax. Boxer was dead.

As the oldest and most experienced tracker of the three-man Save the Rhino Trust’s (SRT) Damara-speaking team, Daniel Alfeus //Hawaxab – aka Boxer – was by all accounts an exemplary employee. At age 37, he had spent his entire adult life looking out for the world’s last free-roaming black rhinos of the Kunene region.

His knowledge of the rugged mountains and deep valleys, watered by secret fountains where the last free black rhinos live, played a major role in the recovery of their numbers after the 1980s slaughter during the South African occupation that left fewer than 20 animals alive. Their numbers now are officially kept secret to deter poachers – but the secrecy also serves to obscure the true state of affairs.

For 20 years, after the last reported case at Mbkondja in 1993, there had been no rhino poaching, as the SRT’s tactics of constantly patrolling the rhino ranges kept the poachers at bay. But on Christmas Day 2012,

the first of 14 carcasses found so far started turning up in the field, at the Kommagorras fountain near Mbkondja.

Mbkondja – a Herero word meaning “struggle” – is a scattered communal farming settlement, roughly halfway between Palmwag and Khowarib, and is where the SRT keeps camels used for foot patrols into the mountains.

Boxer was on the scene quickly and identified a former soldier-turned-cattle herder named Tjihuure Tjiuamba as the most likely suspect. He and two community game guards interrogated him – Boxer was a man known to talk with his hands when necessary, hence his nickname – and Tjiuamba soon pointed out where he had hidden the horns.

He also deposed a sworn affidavit a few weeks later to the police’s Protected Resources Unit, in which he implicated his employer, Efraim Mwanyangapo, as offering him R30 000 for rhino horn and supplying him with two .303 bullets for a rifle he then stole from a man named Jakotwa, he stated.

Jakotwa, a Himba farmer who also kept cattle at Mbkondja, independently confirmed this version. But he has moved away now – there were bad things at Mbkondja he did not want to discuss.

Tjiumba later withdrew his statement in court, claiming it was made under duress. Boxer’s actions, however, provided the legal ground for what has been the only successful prosecution so far, 24 black rhinos later.

So it was strange that no one in the SRT made any effort to get Boxer to the hospital in Opuwo as he lay dying in Sesfontein’s clinic, and that most of colleagues, including all SRT’s management, did not attend his funeral in Sesfontein.

Boxer died alone, in agony. And that had everyone spooked.

Read the rest of the story from Oxpeckers here.

November 27, 2014

It’s The Last Chance for The World’s Most Endangered Marine Mammal

(Richard Ellis/Getty)

One thing for which we should give profound thanks this year is the success of environmental action at stopping or slowing the killing of many endangered marine mammals. As a result, populations of humpback whales, bowhead whales, gray whales, and other species are now rebuilding. But this Thanksgiving, one of the world’s 78 cetacean species still faces its do-or-die moment.

The vaquita, a small porpoise found only in the Gulf of California, is the world’s most endangered marine mammal. Fewer than 100 exist in the wild. Without drastic and immediate action, this species will almost certainly go the way of the Chinese river dolphin, or baiji—declared extinct after a 2006 survey of the Yangtze River turned up zero dolphins. It was the only cetacean humans are known to have snuffed out: a global moment of infamy, not just for China, but for us all. In a final effort not to share that shame, Mexico is expected to announce this week a last desperate effort to save the vaquita.

The vaquita (Phocoena sinus) is a strange and elusive creature, only discovered by scientists in 1958. It grows to a length of four feet, has a blunt, balloon-like face, and lives by feeding on fish and crustaceans in the shallow waters of the Gulf. People almost never see them alive. Vaquita sightings occur

almost exclusively when fishermen pull them up entangled and drowned in the gillnets they use to catch shrimp, mostly for the American market, or to catch the endangered totoaba fish, illegally, for the Chinese market. Sightings are likely to get a lot more rare by 2018. Without major change, according to a report released this summer by the Mexico-based International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA), that’s when the last of the vaquitas will die.

Scientists have been tracking the vaquita’s declining numbers since 1990, and timely action back then could have made a difference. In 1991, the International Whaling Commission recommended a series of protective measures, including a ban on totoaba fishing, education of fishers, and development of alternative fishing methods.

“If those recommendations had been followed, there is little doubt that the vaquita’s situation would now have been largely resolved,” the CIRVA report concluded. In 2005, the Mexican government belatedly established a 500-square-mile Vaquita Refuge Area in the Gulf. It also undertook a $30 million effort to buy out fishing permits, pay fishermen not to fish within the Vaquita Refuge, and replace the deadly gillnets with “vaquita-safe” fishing gear. The efforts appeared to work, up to a point: The annual rate of decline in the population eased down from 10 percent to less than 5 percent. But in the last three years that rate has shot up again to more than 18 percent per year. With only about 100 vaquitas left, each percentage point represents one more porpoise killed—and one giant step closer to extinction.

The sudden increase is mostly due to illegal fishing for totoaba, said Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho, coordinator of marine mammal research and conservation at Mexico’s National Institute of Ecology and Climate Change. Just as the killing of vaquitas finally began to slow down, he said, “suddenly, we had this explosion of illegal totoaba fishing.”

Fishermen harvest the swim bladders from the critically endangered totoaba because buyers in China prize them as delicacies and as folk medicine for fertility, circulation and skin conditions. They can sell for thousands of dollars each on the black market. To catch them, fishermen used the same gillnets that are so deadly and effective at ensnaring vaquitas. For impoverished fishermen, the money is irresistible. “Imagine you threw millions of dollars from a building in New York City,” said Rojas-Bracho. Even if it was against the law to stop, most people would get out of their cars and grab the cash—and who could blame them?

Unfortunately, trying to enforce the ban on totoaba fishing has proved beyond the powers of the Mexican government. The Gulf is a big piece of water for understaffed and underpaid conservation agencies to protect. Because it’s illegal, totoaba fishing also takes place mostly under cover of darkness. In addition, powerful drug cartels are reportedly profiting from the lucrative totoaba trade. As is so often the case in Mexico, that can make the rule of law more a theory than a fact.

Media outlets are now reporting that the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources will make an announcement about the fate of the vaquita on Nov. 27. Government outlets have not yet confirmed this. But now is the time to act, said Zak Smith, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council. He called for a total exclusion of gillnetting from a large portion of the Gulf. “You can’t talk about ‘vaquita friendly’ fishing any more, because there can’t be any. It has to all end,” Smith said.

The CIRVA report released this summer by a committee headed by Rojas-Bracho put it simply: “CIRVA strongly recommends that the government of Mexico enact emergency regulations establishing a gillnet exclusion zone covering the full range of the vaquita—not simply the existing Refuge—starting in September 2014.” It also recommended increased enforcement, efforts to reduce the trade in totoaba swim bladders, and a program to provide an alternative living to communities that now depend on legal gillnet fishing.

Will the government finally get serious about the vaquita? “Even if we get a great plan,” Smith said, “will it be backed up by adequate enforcement?” The alternative is to allow the vaquita to follow the Chinese river dolphin into oblivion.

It may not seem like there’s much the rest of us can do for the vaquita this Thanksgiving, other than pray. But the organization ¡Viva Vaquita urges you to sign its petition on Change.org. Writing to the Ministry of Natural Resources, the Mexican president, and even to the United Nations might also help. The likely extinction of the vaquita is also one more reason to stop buying shrimp, or other fish caught with gillnets.

Finally, it’s worth stepping back to ask why so much of the illegal trafficking in wildlife—and the threat of extinction in the wild to elephants, rhinos, pangolins, tigers, musk deer, Himalayan black bears, and so many other species—leads back time and again to China. When you start your holiday shopping this year and see that “Made in China” label on almost every product, ask yourself: Is this really a country that you want your money to support?

November 26, 2014

Feds Limit Mindless Wolf Killing Contest in Idaho

(Photo: Matthew J. Lee/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

I reported earlier this year on the anti-wolf lunacy in Idaho. Now a federal agency has taken half the land off the table for a planned wolf-killing derby scheduled for January.

Now all we can do is hope the wolves find their way to safe land–and that the hunters, who have minimal regard for the law, don’t follow them there. Here’s the report from Associated Press:

BOISE, Idaho (AP) — Environmental groups have won the latest battle in their effort to halt a wolf- and coyote-shooting derby in Idaho, but a pro-hunting group says the contest with cash prizes for whoever kills the most predators will go on as planned early next year.

The U.S. Bureau of Land Management, facing two federal lawsuits from conservation groups, canceled a permit late Tuesday issued to derby organizer Idaho for Wildlife on Nov. 13.

The agency didn’t mention the lawsuits in a statement but said

modifications to derby rules made by the pro-hunting group after receiving the permit left it unclear if the permit could still apply without another round of analysis.

“We were expecting a fight, so it’s nice to see the BLM had a change of heart,” said Laura King, an attorney for the Western Environmental Law Center. “This is some of the wildest land in America. It is a safe haven for an iconic species that is just getting its foothold in the West.”

Steve Alder of Idaho for Wildlife said BLM officials caved in to environmental groups.

“Somebody in (Washington), D.C., twisted that I was trying to change the application so they could blame us,” he said. “They’re trying to blame somebody else because they couldn’t take the heat.”

Alder said the derby still would be held in January on private ranches in the Salmon area and on U.S. Forest Service land, which doesn’t require a permit, according to a federal judge’s ruling last year. But losing the 3.1 million acres of BLM land cuts the area for the derby in half.

The contest includes a $1,000 prize each for whoever kills the most wolves and coyotes.

Joe Kraayenbrink, the BLM’s district manager in Idaho Falls who signed the decision revoking the permit, didn’t return a call from The Associated Press on Wednesday.

The two lawsuits filed by seven environmental groups contended that the agency violated environmental laws.

King said the Western Environmental Law Center is not withdrawing its lawsuit because it’s not clear if the BLM would conduct the needed environmental analysis should Idaho for Wildlife apply for another permit.

The center is representing WildEarth Guardians, Cascadia Wildlands and the Boulder-White Clouds Council in the lawsuit that also seeks to halt the derby on Forest Service land. The groups contend environmental laws require the agency to do an environmental analysis and issue a permit.

King said a court date hasn’t been set but she expected one before the derby scheduled for Jan. 2-4.

Four other environmental groups — Defenders of Wildlife, the Center for Biological Diversity, Western Watersheds Project and Project Coyote — are also suing the BLM, contending the permit opposes the federal government’s wolf-reintroduction efforts.

Amy Atwood, an attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, said the lawsuit would continue because of ambiguity in the BLM’s statement. “We think this is a serious, precedent-setting case,” she said.

Alder, the derby organizer, predicted that the permit’s loss could drive more hunters to shoot the predators on BLM lands anyway, though any coyotes or wolves killed there wouldn’t be eligible for prize money.

“I think you’re going to see more hunters out,” he said. “This isn’t going to save one coyote from being shot, I can guarantee that.”

The event last year drew 230 people, about 100 of them hunters, who killed 21 coyotes but no wolves.