Richard Conniff's Blog, page 38

November 20, 2014

China’s New Great Wall Threatens One Quarter of World’s Shorebirds

Voyage of the Doomed: Bar-tailed Godwits roost at a key refueling spot on their northward migration. That plume is the fill that will turn this site in Yalujiang, Liaoning Province, China, into dry land. (Photo: David Melville)

Every spring, tens of thousands of plump, russet-breasted shorebirds drop down onto the wetlands of China’s Bohai Bay, ravenous after traveling 3,000 miles from Australia. This Yellow Sea stopover point is crucial for the birds, called red knots, to rest and refuel for the second leg of their journey, which will take them another 2,000 miles up to the Arctic tundra.

Unfortunately for the red knots, the intertidal flats of Bohai Bay are rapidly disappearing, cut off from the ocean by new sea walls and filled in with silt and rock, to create buildable land for development. In a society now relentlessly focused on short-term profit that seems like a wonderful bargain, and the collateral loss of vast areas of shorebird habitat merely an incidental detail. As a result, China’s seawall mileage has more than tripled over the past two decades, and now covers 60 percent of the mainland coastline. This “new Great Wall” is already longer than the celebrated Great Wall of China, according to an article published Thursday in Science, and it’s just getting bigger every year—with catastrophic consequences for wildlife and people.

“Reclamation” is what they still call it, a term dating from an era when pretty much everyone thought wetlands were useless, stinking, swampy places of no possible benefit to people. Or

as an American writer put it in 1867, they “are for all practical purposes, worthless; and the imperative necessity for their reclamation is obvious to all, and is universally conceded.”

Of course, we now know better. Wetlands are among the richest and most diverse habitats on the planet. In China alone, more than 230 species of water birds—a quarter of the global total—depend on wetlands.

Besides the red knots (Calidris canutus), that includes endangered birds like the spoon-billed sandpiper and the Nordmann’s greenshank. Breeding habitat of the threatened Saunders’ Gull “is now almost entirely restricted to one part of one nature reserve,” said David Melville, a New Zealand-based ecologist and coauthor of the Science paper.

If sea walls enclose the last remaining coastal habitat of these survivors, it will likely push them to the brink of extinction. The precedents are ominous: In South Korea, for instance, more than 120,000 great knots (Calidris tenuirostris) used to stop to feed on their long-distance migration, according to Zhijun Ma, the paper’s lead author and a professor at the Fudan University School of Life Sciences. After a seawall went in, the population dropped to fewer than 30,000 birds.

A new, improved coastline in China, minus the birds (Photo: David Melville and Ying Chen)

But when a country is struggling to become part of the developed world, why should it worry about mudflats or birds? Wetlands worldwide provide an endless wealth of ecosystem services, from flood control and carbon storage to production of aquatic life. In 2011, China’s wetlands produced 28 million tons of seafood, about 20 percent of the world’s total, and also served as the nursery for countless aquatic organisms that are the base of the food chain for offshore fisheries. Wetlands also help buffer all those new developments from storm surges. Engineers like to argue that massive sea walls can protect developments in severe storms, and in certain circumstances that may be true. But after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami killed a quarter million people, researchers found that areas that with intact mangrove wetlands had a much higher survival rate.

These benefits tend to be invisible, at least at first, but Ma and his co-authors estimate that in 2011, China’s wetlands produced $200 billion of ecosystem services, a significant chunk of the national economy. In the United States, our gradual recognition of this invisible money in the bank, and of the importance of wetlands for birds and other wildlife, has resulted in a “no net loss” of wetlands policy, and that’s helped to slow the centuries-long decline of wetlands. But in China, the immediate economics benefits of building on reclaimed wetlands continue to outweigh the long-term costs. Mayors and provincial governors are “basically judged on GDP growth,” said Melville. In the past few years the Chinese national government has begun to include measures of environmental performance alongside the economic metrics for evaluating the performance of local authorities.

But it still often looks to local officials as if they get the benefits now, while officials a generation or two down the line get stuck with any costs. So they often circumvent new regulations. For example, wetland projects over 124 acres require the approval of China’s central government. But “local governments simply divide large projects into smaller ones,” according to Ma and his co-authors. Or they quietly re-drawn the boundaries of protected coastal reserves, freeing up wetlands to be filled in and “reclaimed.” Thus the rate of destruction of coastal wetlands is actually accelerating: 148,263 acres per year—an area almost three times the size of Boston—every year through 2020.

Red knots and other migratory birds pay the immediate price. They may travel across multiple countries that have protected wetland habitat, only to see a crucial stopover point destroyed in a country with less stringent environmental laws. The stopovers on China’s coast are especially important as feeding areas on major migratory routes.

Ma and his co-authors list several possible ways to curb the rate of reclamation, including a “no net loss” policy and the creation of an agency to coordinate the numerous government bodies that now oversee wetland management.

“There is some work being done in China at the moment to draw what they’re terming ‘red lines’ around areas of ecological importance and value,” said Melville, in an email. “Hopefully, that will mean that the sites are protected in some way.”

Part of the impetus for this change is the recent global attention to the air and water quality of China (in the news again this week because of the deadly haze now afflicting Beijing). But the environmental shift is still in its early stages. It may be years before the rate of seawall construction or wetland loss starts to slow. The question is whether the red knots and spoon-billed sandpipers will still be around to see it.

November 19, 2014

Lose Forest Elephants and You Lose the Forest

A first-of-its-kind study in Thailand shows that the dramatic loss of elephants, which disperse seeds after eating vegetation, is leading to the local extinction of a dominant tree species, with likely cascading effects for other forest life.

Their work shows that loss of animal seed dispersers increases the probability of tree extinction by more than tenfold over a 100-year period.

“The entire ecosystem is at risk,” said Trevor Caughlin, a University of Florida postdoctoral student and National Science Foundation fellow. “My hope

for this study is that it will provide a boost for those trying to curb overhunting and provide incentives to stop the wildlife trade.”

Caughlin and his co-authors published their study, showing how vital these animals are to maintaining the biodiversity of tropical forests, in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The team looked specifically at seed dispersal and how elephants contribute to moving the seeds around the forest.

Elephant have long been an important spiritual, cultural and national symbol in Thailand. But their numbers have plunged from 100,000 at the beginning of the 20th century to 2,000 today. Like tigers, monkeys and civet cats, they are under attack from hunters and poachers, mostly for fabled properties of their organs, teeth and tusks.

Caughlin spent three years gathering tree data in Thailand. He looked at the growth and survival of trees that sprouted from the parent tree and grew up in crowded environs, compared with seeds that were transported and broadcasted widely across the forest by animals. The data were supplemented with a dataset from the Thai Royal Forest Department that contained more than 15 years of data on trees to create a long-term simulation run on UF’s supercomputer, HiPerGator.

The team discovered that trees that grow from seeds transported by those animals being overhunted are hardier and healthier.

“Previously, it’s been unclear what role seed dispersal plays in tree population dynamics,” Caughlin said. “A tree makes millions of seeds during its lifetime, and only one of those seeds needs to survive to replace the parent tree. On the surface, it doesn’t seem like seed dispersal would be that important for tree population. What we found with this study is that seed dispersal has an impact over the whole life of a tree.”

“This study fills a major gap in our understanding of how overhunting affects forest trees, particularly in tropical forests,” said Richard Corlett, director of the Center for Integrative Conservation at the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Gardens in Yunnan, China. “We knew hunting was bad, but we were not sure why it was bad, and therefore could not predict the long-term impacts. Now we know it is really, really bad and will get worse. The message that ‘guns kill trees too’ should help put overhunting at the top of the conservation agenda, where it deserves to be.”

November 17, 2014

Look, Look, Look! A Lesson in the Art of Seeing

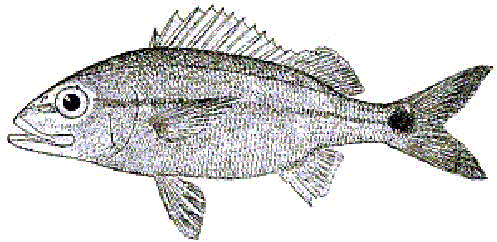

Scudder’s fish.

I’ve never been particularly fond of the nineteenth century naturalist Louis Agassiz, probably due to a time I was sitting in a library at Harvard and holding in my hands a letter he had written to his mother about his feelings on first seeing an African-American. It was so appallingly racist, so naive, so entitled to an unwarranted sense of superiority that I actually gasped out loud.

But just now, I was looking over a book called Louis Agassiz as a Teacher, and I read this brilliant and almost endearing account of his methods. Entirely beyond natural history, it is a very fine lesson in the art of seeing, and belongs in a category I should probably called “Valuable Lessons from Loathesome Men.” It was written in 1874 by Samuel H. Scudder, a young entomologist who found himself being instructed, not altogether happily, by Agassiz, a very learned student of fish:

It was more than fifteen years ago that I entered the laboratory of Professor Agassiz, and told him I had enrolled my name in the Scientific School as a student of natural history. He asked me a few questions about my object in coming, my antecedents generally, the mode in which I afterwards proposed to use the knowledge I might acquire, and, finally, whether I wished to study any special branch. To the latter I replied that, while I wished to be well grounded in all departments of zoology, I purposed to devote myself specially to insects.

‘When do you wish to begin?’ he asked.

‘Now,’ I replied.

This seemed to please him, and with an energetic ‘Very well!’ he reached from a shelf a huge jar of specimens in yellow alcohol.

‘Take this fish,’ said he, ‘and look at it; we call it a haemulon; by and by I will ask what you have seen.’

With that he left me, but in a moment returned with explicit instructions as to the care of the object entrusted to me.

‘No man is fit to be a naturalist,’ said he, ‘who does not know how to take care of specimens.’

I was to keep the fish before me in a tin tray, and occasionally

moisten the surface with alcohol from the jar, always taking care to replace the stopper tightly. Those were not the days of ground-glass stoppers and elegantly shaped exhibition jars; all the old students will recall the huge neckless glass bottles with their leaky, wax -besmeared corks, half eaten by insects, and begrimed with cellar dust. Entomology was a cleaner science than ichthyology, but the example of the Professor, who had unhesitatingly plunged to the bottom of the jar to produce the fish, was infectious; and though this alcohol had ‘a very ancient and fishlike smell,’ I really dared not show any aversion within these sacred precincts, and treated the alcohol as though it were pure water. Still I was conscious of a passing feeling of disappointment, for gazing at a fish did not commend itself to an ardent entomologist. My friends at home, too, were annoyed, when they discovered that no amount of eau-de-Cologne would drown the perfume which haunted me like a shadow.

In ten minutes I had seen all that could be seen in that fish, and started in search of the Professor–who had, however, left the Museum; and when I returned, after lingering over some of the odd animals stored in the upper apartment, my specimen was dry all over. I dashed the fluid over the fish as if to resuscitate the beast from a fainting -fit, and looked with anxiety for a return of the normal sloppy appearance. This little excitement over, nothing was to be done but to return to a steadfast gaze at my mute companion. Half an hour passed –an hour–another hour; the fish began to look loathsome. I turned it over and around; looked it in the face–ghastly, from behind, beneath, above, sideways, at a three-quarters’ view–just as ghastly. I was in despair; at an early hour I concluded that lunch was necessary; so, with infinite relief, the fish was carefully replaced in the jar, and for an hour I was free.

Agassiz

On my return, I learned that Professor Agassiz had been at the Museum, but had gone, and would not return for several hours. My fellow-students were too busy to be disturbed by continued conversation. Slowly I drew forth that hideous fish, and with a feeling of desperation again looked at it. I might not use a magnifying-glass; instruments of all kinds were interdicted. My two hands, my two eyes, and the fish: it seemed a most limited field. I pushed my finger down its throat to feel how sharp the teeth were. I began to count the scales in the different rows, until I was convinced that that was nonsense. At last a happy thought struck me –I would draw the fish; and now with surprise I began to discover new features in the creature. Just then the Professor returned.

‘That is right,’ said he; ‘a pencil is one of the best of eyes. I am glad to notice, too, that you keep your specimen wet, and your bottle corked.’

With these encouraging words, he added:

‘Well, what is it like?’

‘You have not looked very carefully; why,’ he continued more earnestly,’ you haven’t even seen one of the most conspicuous features of the animal, which is as plainly before your eyes as the fish itself; look again, look again!’ and he left me to my misery.

I was piqued; I was mortified. Still more of that wretched fish! But now I set myself to my task with a will, and discovered one new thing after another, until I saw how just the Professor’s criticism had been. The afternoon passed quickly; and when, toward its close, the Professor inquired:

‘Do you see it yet?’

‘No,’ I replied, ‘I am certain I do not, but I see how little I saw before.’

‘That is next best,’ said he, earnestly, ‘but I won’t hear you now; put away your fish and go home; perhaps you will be ready with a better answer in the morning. I will examine you before you look at the fish.’

This was disconcerting. Not only must I think of my fish all night, studying, without the object before me, what this unknown but most visible feature might be; but also, without reviewing my new discoveries, I must give an exact account of them the next day. I had a bad memory; so I walked home by Charles River in a distracted state, with my two perplexities.

The cordial greeting from the Professor the next morning was reassuring; here was a man who seemed to be quite as anxious as I that I should see for myself what he saw.

‘Do you perhaps mean,’ I asked, ‘that the fish has symmetrical sides with paired organs?’

His thoroughly pleased ‘Of course! of course!’ repaid the wakeful hours of the previous night. After he had discoursed most happily and enthusiastically–as he always did-upon the importance of this point, I ventured to ask what I should do next.

‘Oh, look at your fish!’ he said, and left me again to my own devices. In a little more than an hour he returned, and heard my new catalogue.

‘That is good, that is good!’ he repeated; ‘but that is not all; go on;’ and so for three long days he placed that fish before my eyes, forbidding me to look at anything else, or to use any artificial aid. ‘Look, look, look,’ was his repeated injunction.

This was the best entomological lesson I ever had–a lesson whose influence has extended to the details of every subsequent study; a legacy the Professor has left to me, as he has left it to many others, of inestimable value, which we could not buy, with which we cannot part.

A year afterward, some of us were amusing ourselves with chalking outlandish beasts on the Museum blackboard. We drew prancing starfishes; frogs in mortal combat; hydra-headed worms; stately crawfishes, standing on their tails, bearing aloft umbrellas; and grotesque fishes with gaping mouths and staring eyes. The Professor came in shortly after, and was as amused as any at our experiments. He looked at the fishes.

‘Haemulons, every one of them,’ he said; ‘Mr.—- drew them.’

True; and to this day, if I attempt a fish, I can draw nothing but haemulons.

The whole group of haemulons was thus brought in review; and, whether engaged upon the dissection of the internal organs, the preparation and examination of the bony frame-work, or the description of the various parts, Agassiz’s training in the method of observing facts and their orderly arrangement was ever accompanied by the urgent exhortation not to be content with them.

‘Facts are stupid things,’ he would say, ‘until brought into connection with some general law.’

At the end of eight months, it was almost with reluctance that I left these friends and turned to insects; but what I had gained by this outside experience has been of greater value than years of later investigation in my favorite groups.

NOTE: Published as ‘In the Laboratory with Agassiz,’ by Samuel H. Scudder, from Every Saturday (April 4, 1874) 16, 369-370.

November 14, 2014

Putting Mountain Lions on Treadmills is Good–if Weird–Science

(Photo: Nancy Howard, Colorado Parks & Wildlife)

In 1882, a congressman from Alabama took the House floor to rant about a recent study showing that primitive birds had reptile-like teeth. “Birds with teeth!” Hilary Herbert cried, “That’s where your hard-earned money goes, folks—on some professor’s silly birds with teeth.” As it happened, those birds were one of the great advances in our understanding of life on Earth, hinting at what we now know: Birds evolved from dinosaurs. But with a politician’s instinct for the kill, Herbert simply latched onto the headline-worthy phrase “birds with teeth” and rode it hard. A telegram from a government official soon advised the scientist, “Appropriations cut off. Please send your resignation at once.”

Not much has changed in the 132 years since then. Using a silly sounding phrase to ridicule scientific research is still a favorite device of cheap-trick politicians, and wildlife studies are an especially tempting target, as Senator Tom Coburn, a Republican from Oklahoma, recently demonstrated.

First the background: Wildlife researchers customarily use radio collars equipped with GPS to track animals and figure out where they’ve been—but those collars don’t show much about what an animal has been doing. A new collar changes that, with accelerometers to monitor the critter’s position and acceleration. That’s recently enabled scientists working with a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to study how mountain lions in California behave as they search for their prey, stalk it, and finally pounce. Before they

could try these new collars in the field, though, the researchers had to calibrate them first. That meant training captive mountain lions to walk on a treadmill. You can probably figure out how that must’ve sounded to a politician looking for a little headline bait. But hang on. The study was important enough that it was recently published in Science, one of the world’s premier scientific journals.

That wasn’t good enough for Senator Coburn. He publishes a “Wastebook” every year, a list of government expenditures that he thinks are a waste of our tax dollars. He’s basically just recycling a favorite device of the late Senator William Proxmire, a Democrat from Wisconsin, who liked to hand out the “Golden Fleece Award” to projects he viewed as wasteful. Coburn’s latest Wastebook features several NSF-funded research projects, and coming in at number four on the 100-item list is “Mountain Lions on a Treadmill.

This time, though, the researcher fought back, in an op-ed piece for the Los Angeles Times. “Our goal was to provide a new tool for wildlife conservation,” wrote Terrie M. Williams, a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “The wildlife collars we designed can be used to avoid human-animal conflicts by predicting when and where predatory animals hunt. In the process, they will help save human lives, our pets and livestock, as well as the large predatory mammals that represent the ‘top-of-the-food chain’ glue holding our ecosystems together. It is a problem that’s all too familiar in densely populated California, where human-wildlife encounters have increased.”

Let’s make that a little more clear: The study could help save taxpayers from being mauled or killed by big scary predators. (O.k., probably not Oklahoma taxpayers. So never mind.) Reducing wildlife conflict is also of course a good thing for the predators, which are part of our national heritage. But instead of being congratulated, Williams suddenly found her work being lampooned from coast-to-coast as “dubious,” “absurd,” “ridiculous,” “outlandish,” and worse.

Neither Coburn nor his staff bothered to contact Williams, or any members of her research team, to check their facts ahead of time. Heck, they probably never even bothered to read the study, or they might have seen that the treadmill training was a minor part of it. What’s more, Williams wrote, “my time involving the treadmill-walking mountain lions and their trainers was never charged to the grant.”

In the Wastebook write-up, Coburn acknowledged that “support for basic science is not itself wasteful.” So what did he find so offensive about Williams’s project, which actually went beyond basic science to show applications in real life? Here’s my guess: Coburn just liked the click bait-quality of the words “mountain lions on a treadmill.”

Applying to the National Science Foundation for biological research funding is a harrowing process. Scientists submit a pre-proposal. If they’re lucky, the NSF invites them to submit a full proposal, consisting of detailed descriptions of the intended research with exhaustively-researched citations and mountains of evidence explaining why the research is important. Getting funded to study lions, wolves, or other wildlife species is particularly difficult, according to Williams, who says proposals for single-celled organisms are up to 44 times more likely to succeed.

Cynical politicians like Coburn just mean to make the application process even more frustrating, especially for wildlife researchers. Texas Representative Lamar Smith, chair of the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee, has also piled on, recently demanding “every e-mail, letter, memorandum, record, note, text message, all peer reviews” for 11 NSF grants, including one of the grants that supported the mountain lion study.

Williams isn’t the only one worried by this anti-science witch-hunt. “Our broader concern is this,” the Association of American Universities declared in a statement released on Monday, “that NSF will be pressured to fund only ‘safe’ research that does not attract political attention…and that NSF peer reviewers will therefore reject potentially important but odd-sounding proposals.” It notes that “several projects are being investigated for no apparent reason other than the sound of their titles.”

The Republican intolerance for scientific research—on wild animals, the environment, climate change, you name it—scares me. Let me give you one quick example of what we can lose because of the tendency to “ridicule scientific research projects by caricature,” as columnist Michael Hiltzik put it earlier this week. Back in 1966, NSF funded a project that we could easily laugh off as “Scientists Go to the Park and Look at Slime.” But that study of bacteria living in geysers and thermal springs at Yellowstone National Park resulted in the discovery of Thermus aquaticus, a bacteria that yielded an enzyme called Taq. And that enzyme is an essential ingredient of every DNA study performed anywhere in the world. Without it, DNA testing for diseases, or the entire modern science of genomics, would be impossible.

Coburn’s office did not respond to a request for comment. In fairness, I want to give the last word to Senator Coburn anyway. In 2009, he declared, “I am not the smartest man in the world,” and for once he was telling the truth. Am I taking his words out of context? Maybe so, but that’s just how the Coburns of the world like to operate.

November 12, 2014

Expectant Snake Moms Crave Toxic Toads

O.K., this still does not explain the pickle-and-ice cream cravings of pregnant women. But it’s always interesting to discover that our own strange behaviors have parallels in the animal world. The very brief story comes from Science News:

O.K., this still does not explain the pickle-and-ice cream cravings of pregnant women. But it’s always interesting to discover that our own strange behaviors have parallels in the animal world. The very brief story comes from Science News:

Female tiger keelback snakes seek out toxic toads to eat when breeding, researchers report November 12 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. A taste for toxins may

arm their young, keeping them safe until they can hunt for their own defenses.

B. japonicus. Yum.

Rhabdophis tigrinus snakes, found across Asia, store chemicals from Bufo japonicus toads in special nuchal glands. These glands release the toxins when the snake is attacked. Males and nonbreeding females eat few toads, preferring tastier prey such as green tree frogs. But breeding females prefer environments populated with toads and will follow the trails of these poisonous snacks, passing the toxins on to their offspring.

November 8, 2014

It Took 2500 Humans Just 100 years to Hunt the Moa to Extinction

A new study shows that early Polynesian settlers in New Zealand needed just a century, and a maximum population of about 2500 people, to drive the huge flightless bird called the moa to extinction. This strikes me as interesting partly because environmentalists often exaggerate and romanticize the conservationist ethic of pre-European populations, a line of wishful thinking now widely discredited by evidence from around the world. If the timetable is correct, Polynesians were ravaging the environment in New Zealand–2500 people in an area the size of Colorado–at about the same time Europeans were doing so in the New World.

What’s more interesting, by inference, is the idea that it’s not just the number of people living in a place that causes extinctions. It’s how they choose to live there. That is, with the skills and weapons any human population brings to the hunt, it takes basic rules to ensure the permanent availability of major resources. Eating all the eggs of your largest bird? Bad idea.

Here’s the press release:

A new study suggests that the flightless birds named moa were completely extinct by the time New Zealand’s human population had grown to two and half thousand people at most.

The new findings, which appear in the journal Nature Communications, incorporate results of research by international teams involved in two major projects led by Professor Richard Holdaway (Palaecol Research Ltd and University of Canterbury) and Mr Chris Jacomb (University of Otago), respectively.

The researchers calculate that the Polynesians whose activities caused moa extinction in little more than a century had amongst the lowest human population densities on record. They found that during the peak period of moa hunting, there were fewer than 1500 Polynesian settlers in New Zealand, or about 1 person per 100 square kilometres, one of the lowest population densities recorded for any pre-industrial society.

They found that the human population could have reached

about 2500 by the time moa went extinct. For several decades before then moa would have been rare luxuries.

Estimates of the human population during the moa hunting period are more sensitive to how long it took to exterminate the birds through hunting and habitat destruction than to the size of the founding population.

To better define the critical period of moa hunting, the research was aimed at “book-ending” the moa hunter period with new estimates for when people started eating moa, and when there were no more moa to eat.

Starting with the latest estimate for a founding population of about 400 people (including 170-230 women), and applying population growth rates in the range achieved by past and present populations, the researchers modelled the human population size through the moa hunter period and beyond. When moa and seals were still available, the better diet enjoyed by the settlers likely fuelled higher population growth, and the analyses took this into account.

The first “book-end” — first evidence for moa hunting — was set by statistical analyses of 93 new high-precision radiocarbon dates on genetically identified moa eggshell pieces. These had been excavated from first settlement era archaeological sites in the eastern South Island, and showed that moa were still breeding nearby.

Chris Jacomb explains: “The analyses showed that the sites were all first occupied — and the people began eating moa — after the major Kaharoa eruption of Mt Tarawera of about 1314 CE.”

Ash from this eruption is an important time marker because no uncontested archaeological evidence for settlement has ever been found beneath it, Mr Jacomb says.

The other “book-end” was derived from statistical analyses of 270 high-precision radiocarbon dates on moa from non-archaeological sites. Analysis of 210 of the ages showed that moa were exterminated first in the more accessible eastern lowlands of the South Island, at the end of the 14th century, just 70-80 years after the first evidence for moa consumption.

Analysis of all 270 dates, on all South Island moa species from throughout the South Island, showed that moa survived for only about another 20 years after that.

Their total extinction most probably occurred within a decade either side of 1425 CE, barely a century after the earliest well-dated site, at Wairau Bar near Blenheim, was settled by people from tropical East Polynesia. The last known birds lived in the mountains of north-west Nelson. Professor Holdaway adds that “the results provide further support for the rapid extinction model for moa that Chris Jacomb and I published 14 years ago in [the US journal] Science.”

The researchers note that it is often suggested that people could not have caused the extinction of megafauna such as the mammoths and giant sloths of North America and the giant marsupials of Australia, because the human populations when the extinctions happened were too small.

Prof Holdaway and Mr Jacomb say that the extinction of the New Zealand terrestrial megafauna of moa, giant eagle, and giant geese, accomplished by the direct and indirect activities of a very low-density human population, shows that population size can no longer be used as an argument against human involvement in extinctions elsewhere.

Journal Reference:

Richard N. Holdaway, Morten E. Allentoft, Christopher Jacomb, Charlotte L. Oskam, Nancy R. Beavan, Michael Bunce. An extremely low-density human population exterminated New Zealand moa. Nature Communications, 2014; 5: 5436 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6436

2500 Humans Needed Just 100 years to Hunt the Moa to Extinction

A new study shows that early Polynesian settlers in New Zealand needed just a century, and a maximum population of about 2500 people, to drive the huge flightless bird called the moa to extinction. This strikes me as interesting partly because environmentalists often exaggerate and romanticize the conservationist ethic of pre-European populations, a line of wishful thinking now widely discredited by evidence from around the world. If the timetable is correct, Polynesians were ravaging the environment in New Zealand–2500 people in an area the size of Colorado–at about the same time Europeans were doing so in the New World.

What’s more interesting, by inference, is the idea that it’s not just the number of people living in a place that causes extinctions. It’s how they choose to live there. That is, with the skills and weapons any human population brings to the hunt, it takes basic rules to ensure the permanent availability of major resources. Eating all the eggs of your largest bird? Bad idea.

Here’s the press release:

A new study suggests that the flightless birds named moa were completely extinct by the time New Zealand’s human population had grown to two and half thousand people at most.

The new findings, which appear in the journal Nature Communications, incorporate results of research by international teams involved in two major projects led by Professor Richard Holdaway (Palaecol Research Ltd and University of Canterbury) and Mr Chris Jacomb (University of Otago), respectively.

The researchers calculate that the Polynesians whose activities caused moa extinction in little more than a century had amongst the lowest human population densities on record. They found that during the peak period of moa hunting, there were fewer than 1500 Polynesian settlers in New Zealand, or about 1 person per 100 square kilometres, one of the lowest population densities recorded for any pre-industrial society.

They found that the human population could have reached

about 2500 by the time moa went extinct. For several decades before then moa would have been rare luxuries.

Estimates of the human population during the moa hunting period are more sensitive to how long it took to exterminate the birds through hunting and habitat destruction than to the size of the founding population.

To better define the critical period of moa hunting, the research was aimed at “book-ending” the moa hunter period with new estimates for when people started eating moa, and when there were no more moa to eat.

Starting with the latest estimate for a founding population of about 400 people (including 170-230 women), and applying population growth rates in the range achieved by past and present populations, the researchers modelled the human population size through the moa hunter period and beyond. When moa and seals were still available, the better diet enjoyed by the settlers likely fuelled higher population growth, and the analyses took this into account.

The first “book-end” — first evidence for moa hunting — was set by statistical analyses of 93 new high-precision radiocarbon dates on genetically identified moa eggshell pieces. These had been excavated from first settlement era archaeological sites in the eastern South Island, and showed that moa were still breeding nearby.

Chris Jacomb explains: “The analyses showed that the sites were all first occupied — and the people began eating moa — after the major Kaharoa eruption of Mt Tarawera of about 1314 CE.”

Ash from this eruption is an important time marker because no uncontested archaeological evidence for settlement has ever been found beneath it, Mr Jacomb says.

The other “book-end” was derived from statistical analyses of 270 high-precision radiocarbon dates on moa from non-archaeological sites. Analysis of 210 of the ages showed that moa were exterminated first in the more accessible eastern lowlands of the South Island, at the end of the 14th century, just 70-80 years after the first evidence for moa consumption.

Analysis of all 270 dates, on all South Island moa species from throughout the South Island, showed that moa survived for only about another 20 years after that.

Their total extinction most probably occurred within a decade either side of 1425 CE, barely a century after the earliest well-dated site, at Wairau Bar near Blenheim, was settled by people from tropical East Polynesia. The last known birds lived in the mountains of north-west Nelson. Professor Holdaway adds that “the results provide further support for the rapid extinction model for moa that Chris Jacomb and I published 14 years ago in [the US journal] Science.”

The researchers note that it is often suggested that people could not have caused the extinction of megafauna such as the mammoths and giant sloths of North America and the giant marsupials of Australia, because the human populations when the extinctions happened were too small.

Prof Holdaway and Mr Jacomb say that the extinction of the New Zealand terrestrial megafauna of moa, giant eagle, and giant geese, accomplished by the direct and indirect activities of a very low-density human population, shows that population size can no longer be used as an argument against human involvement in extinctions elsewhere.

Journal Reference:

Richard N. Holdaway, Morten E. Allentoft, Christopher Jacomb, Charlotte L. Oskam, Nancy R. Beavan, Michael Bunce. An extremely low-density human population exterminated New Zealand moa. Nature Communications, 2014; 5: 5436 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6436

November 7, 2014

That Rat Poison? It’s Killing Bobcats in Your Backyard

Bobcats live all around us. (Photo: John Fowler/Flickr)

A few years ago, I was driving in a Connecticut suburb when a bobcat crossed the road in front of me. He was heftier than a house cat, or even a fox, with tufted ears, a short, “bobbed” tail, and a ballsy, street-smart attitude. He stopped in front of me as I was slowing down, and glowered, as if to say “You got a problem, pal?” When I looked suitably chastened, he turned away and strolled onward.

If ever a species was ready to find room for itself in our increasingly urbanized world, the bobcat (Lynx rufus) is it. My encounter to the contrary, bobcats are generally ghosts—solitary, nocturnal, and elusive, slipping through the dark corners of our lives. They’re relatively small, only about 15 pounds for females and 20 for males, which helps them live around us unnoticed. They thrive on the sort of small and medium-sized prey species commonly found in developed areas, including mice, rats, squirrels, and rabbits.

In his 2010 book, Urban Carnivores, Seth Riley, a wildlife ecologist with the National Park Service, called bobcats “perhaps the most adaptable cat species in the Western Hemisphere.” Riley has seen bobcats raising kittens in

suburban backyards, and he’s tracked radio-collared bobcats on the prowl through residential neighborhoods around Los Angeles. Bobcats are the most abundant wildcats in North America, with a dozen subspecies found in almost every habitat type coast-to-coast, and an estimated population as high as one million individuals.

So why worry about bobcats? The urban landscape is still a risky place, and there’s going to be a lot more of it in the bobcat’s future (and ours). The United States Forest Service estimates that urbanized land area nationwide will have more than tripled between 1990 and 2050. In Northeastern states like mine, more than 60 percent of the total land area will be urban by midcentury, up from about 35 percent in 2000.

One of the biggest urban threats to bobcats comes from our indiscriminate use of rat poison. When people illegally use poison outside their homes or businesses, the bobcats get a second-hand dose by eating the poisoned rats or squirrels. It may not kill them outright, but it seems to impair their immune systems and make them much more susceptible to mange. Riley and his colleagues saw bobcat scats in their study area drop 70 percent after one mange outbreak. Thirty of their radio-collared bobcats died, and all tested positive for the anticoagulants in rat poisons. Instead of using such poisons, Riley recommends rat-proofing buildings and relying on snap traps or rat-zappers. If you somehow feel you must use poisons, use them indoors only and avoid those with the anticoagulants bromadialone, difethialone, or diphacinone.

Roads are also a problem. Vehicle strikes on smaller secondary roads are the main cause of death for bobcats in some counties around Los Angeles. Hence bobcats tend to prefer areas with lower road densities, according to a recent study. Male bobcats in particular seem to be affected. “Once they start to bump up against the roads, they tend to have smaller home ranges,” said Sharon Poessel, a doctoral student at Utah State University and lead author of the study. In undeveloped natural areas, “we don’t see males with these small home ranges,” added Erin Boydston, a co-author with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Highways are virtually impassable. One solution, according to Riley and Poessel, is to install wildlife crossings over or under highways. Bobcats appear to make use of these crossings, and that connectivity can help maintain gene flow among otherwise isolated populations. On some secondary roads, said Riley, it may also make sense to installing fencing to prevent bobcats from entering the road and to steer them instead to a wildlife crossing. “They’ve done lots of that, especially in Europe and Canada,” he said. “They’re way ahead of us on that kind of stuff.”

Open space corridors also help: “Maintaining a reasonable amount of open space,” including some areas that are relatively large, “is going to be critical for all kinds of wildlife, especially for carnivores,” Riley said.

Ultimately, bobcats make good neighbors. Unlike raccoons, they don’t generally carry rabies. Unlike mountain lions, now also found in many urban areas around the West, they aren’t big enough to scare the wits out of you. A bobcat running across your path looks about as threatening as an oversized housecat. Bobcats also provide valuable pest control of rodent populations. Plus, “they’re super cool,” with their ear and facial tufts and their short tails, said Riley.

For bobcats as for a lot of other wildlife, that’s really all the reason anybody should need to keep them around.

November 5, 2014

Becoming Iconic. Almost by Accident

When the foldout page is closed, this image in the 1965 Time-Life book Early Man, drawn by Rudolph Zallinger, shows only six steps in human evolution. The image has been endlessly parodied.

When the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale unveiled one of the largest murals in the world, shortly after World War II, the New York Times splashed the image across six columns of type. The 110-foot-long, 16-foot-tall painting, called The Age of Reptiles, depicted roughly 300 million years of dinosaur evolution, from the Devonian through the Cretaceous periods, and, according to paleontologist Karl Waage, later the museum’s director, it “put the museum on the map.”

It also made a name for Rudolph Zallinger ’42BFA, ’71MFA, a young Russian-born graduate of the Yale School of Fine Arts, who had spent more than four years on the mural. His work won the 1949 Pulitzer Fellowship in Art, and it caught the eye of editors at Time-Life; in 1953 Life magazine published a foldout image of the entire mural. (Hence Zallinger’s image of Tyrannosaurus became an unintended inspiration for the main character in a 1954 film from Japan called Godzilla.) Zallinger continued to work on assignments for Life and Time-Life Books after that. In the course of one such assignment, he made cartoon history, almost by accident, with a visual trope that’s instantly recognizable and yet almost never attributed to him

It started with an illustration he produced for the 1965 Time-Life book Early Man. In a section headlined “The Road to Homo Sapiens,” Zallinger depicted a line of proto-apes, apes, and hominids rising from a crouch to a hunch to the tall, upright, almost erudite modern man. The full fold-out spread showed 15 individuals, starting with Pliopithecus and ending with Homo sapiens. But when folded in, a more simplified version appeared, with just six individuals. It became known as March of Progress, from a line in the text, and it went on to become one of the most famous images in the history of scientific illustration, almost as familiar as Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.

In fact, similar drawings had appeared as far back as T. H. Huxley’s 1863 book Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature. But after Zallinger, it became a meme. In the half century since Progress first appeared, versions of this drawing have turned up, among other improbable places, on the cover of a Doors album, as the emblem of the Leakey Foundation, and as an ad for Guinness—the final stage in primate evolution evidently involving an Imperial pint. Among more-recent parodies, one cartoon depicted modern man as a bloated fast food customer who evolves into an actual pig. Another, drawn by Simpsons creator Matt Groening, depicted “Neanderslob” evolving into “Homersapien.”

But serving the whim of editors at Time-Life didn’t work out so well for science. Evolution isn’t necessarily about progress, as that Homer Simpson example might suggest. In his 1989 book Wonderful Life, paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould fumed that March of Progress had become “the canonical representation of evolution—the one picture immediately grasped and viscerally understood by all.” It was a “false iconography,” he wrote. “Life is a copiously branching bush, continually pruned by the grim reaper of extinction, not a ladder of predictable progress.” According to one of Zallinger’s daughters, Lisa David, her father had also objected to the linear layout. He had drawn each figure separately, and he worried that presenting them as a continuous series misrepresented “from a scientific point of view, how this whole evolution occurred.”

In his critique, Gould added that his own books were “dedicated to debunking this picture of evolution.” But the iconography of March of Progress had by then become too powerful and pervasive to dislodge. It had already turned up on the foreign-edition covers of a book by, yes, Stephen Jay Gould.

October 31, 2014

Big Coal Dumps on Wildlife in a Biological Motherlode

(Photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images)

When most people think about a biological hotspot, a motherlode of species, the Amazon may come to mind, along with certain regions in West Africa and Southeast Asia. Hardly anybody thinks about the Appalachians. But more species of salamanders and freshwater mussels live in the streams and forests of this region, stretching from upstate New York to northern Alabama, than anywhere else in the world. Those temperate, deciduous forests are more diverse than anywhere else in the world, too, apart from those in central China.

Unfortunately, seams of coal also run through the Appalachian Mountains, often buried deep within the range. To extract it, coal companies have been literally blowing the tops off of these mountains in a practice called mountaintop removal coal mining. Not only does this method change the landscape and leave swaths of barren rock in place of forested mountainsides, but the mining companies also take the millions of tons of dynamited rock and dump them in the valleys next to the decapitated mountains. These valleys usually have streams in them, and those streams are where the salamanders, mussels, and other freshwater species of the region live. As you might imagine, these animals don’t love having chunks of mountain dumped on their habitat.

A new study confirms that salamanders, in particular, fare poorly in these streams. Researchers from the University of Kentucky visited sites where mining companies had dumped the so-called “overburden” (or “spoil”) and looked for salamanders just downstream of the dumped mountain debris, comparing the abundance of five salamander species in those streams with nearby streams that hadn’t been disrupted.

Overburdened streams averaged about half as many species of salamander, and far fewer individual salamanders, as the undisturbed streams. Across 11 streams with mountain rubble, researchers found just 97 salamanders, compared with 807 salamanders in a dozen control streams.

How do mining companies get away with it?

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 (SMCRA) requires miners to certify that these sites have undergone restoration and reclamation. The sites in this study were mined in the late 1990s and certified as “reclaimed” in 2007 by the Kentucky Department for Natural Resources. But all that really means, said Steven J. Price, a University of Kentucky professor and co-author of the paper, is that the mining companies “were able to get some primarily non-native grasses to grow on these sites,” preventing some erosion. “It’s not as if this is a highly diverse central Appalachian forest any more,” he said.

Red salamander. (Photo: Christian Oldham)

As expected, being smothered under a broken mountain also wrecked the water quality of these mountain streams. Specific conductance—a general measure of the amount of electricity-conducting particles in water—was about 30 times higher in overburdened streams, and concentrations of sulfate ions were 70 times higher. Satellite imagery also showed that these streams had only about a quarter tree cover, compared to the thickly-forested control streams.

With so many changes to the habitat, it’s hard to say for sure what exactly is causing the decline in salamanders, said Price. “The water quality issues seem to be really important,” he said. Two of the salamander species studied—the red salamander and the southern two-lined salamander—live in the forests during the non-breeding season, so deforestation would also hit them hard.

The practice of mountaintop removal began almost 40 years ago in Kentucky and West Virginia, and has since spread to Tennessee and Virginia, destroying 450,000 acres of Appalachian countryside without much serious consideration of the effects on wildlife. “The study was long overdue,” said Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity. “It makes sense that amphibians would be very sensitive to the water pollution from surface coal mining. It increases the saltiness of the water, it puts metals into the water.” Nor is it just stream-dwelling animals that suffer, she added. “In the last couple years, there’s been a ton of science coming out about health impacts of mountain top removal coal mining on human communities,” she noted, including increased rates of lung cancer and heart disease.

“I love the Appalachian Mountains,” said Curry, who grew up in a mountaintop removal area of Kentucky. “I think that they’re the most beautiful place on Earth, and as a scientist, I’m aware of how precious they are. It’s really heart-wrenching to see the land that I love being blown to bits.” She called Appalachia a “sacrifice area” to satisfy the nation’s ravenous hunger for coal. “It wouldn’t happen anywhere else in the country,” she said. But the poverty rate in some parts of the region is more than twice the national average, and the people there lack the political clout to stand up against the powerful forces behind the coal industry.

Curry detailed, with palpable frustration, the loopholes that have allowed mountaintop removal mining and the dumping of overburden on streams to continue. For instance, the Clean Water Act should protect these streams. But a 2002 regulatory change under the Bush Administration specifically exempted the dumping of mining waste. Likewise the Endangered Species Act should protect species like the hellbender, the giant salamanders that are quickly disappearing from their Appalachian habitats. But in 1996, said Curry, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service basically gave mining companies a free pass, requiring them only to meet the SMCRA reclamation requirements. “It’s a ridiculously broad document,” said Curry.

What will it take to stop mountaintop removal mining? In 2013, more than 20 members of Congress introduced the Appalachian Community Health Emergency Act, to “place a moratorium on permitting for mountaintop removal coal mining until health studies are conducted by the Department of Health and Human Services.” But a similar bill died in committee in 2012, and the bill-tracking service GovTrack.us gives this one just a 4 percent chance of passing.

A coalition of groups called iLoveMountains.org continues to fight mountaintop removal mining. , and fossil fuels generally, can be effective. But beware that divesting is complicated for the individual. Some cities and towns outside the region have also recently passed policies preventing power companies from buying coal or energy that comes from mountaintop removal. But Big Coal has well-paid lobbyists and plenty of campaign contributions to protect its privileged status. Against that kind of power, the only force strong enough to make a difference is an outcry from people everywhere that destroying a global heritage like the Appalachian Mountains is simply wrong.