Richard Conniff's Blog, page 39

October 31, 2014

What Are Your Wearing for Halloween, Deer?

Vampire deer in Afghanistan, ready for romance.

And, darling, what big teeth you have!

I was thinking the folks at the Wildlife Conservation Society just put out this press release to have a little fun at Halloween. But it’s based on a new study in the October issue of the journal Oryx (also apparently feeling the Halloween spirit) and the species Moschus cupreus is apparently real, and poachers know it:

More than 60 years after its last confirmed sighting, a strange deer with vampire-like fangs still persists in the rugged forested slopes of northeast Afghanistan according to a research team led by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), which confirmed the species presence during recent surveys.

Known as the Kashmir musk deer – one of seven similar species found in Asia – the last scientific sighting in Afghanistan was believed to have been made by a Danish survey team traversing the region in 1948. The study was published in the Oct. 22nd edition of the journal Oryx. Authors include: Stephane Ostrowski and Peter Zahler of the Wildlife Conservation Society, Haqiq Rahmani of the University of Leeds, and Jan Mohammad Ali and Rita Ali of Waygal, Nuristan, Afghanistan.

The species is categorized as Endangered on the IUCN Red List due to habitat loss and poaching. Its scent glands are coveted by wildlife traffickers and are

considered more valuable by weight than gold, fetching as much as $45,000/kilo on the black market. The male’s distinct saber-like tusks are used during the rutting season to compete with other males.

The survey team recorded five sightings, including a solitary male in the same area on three occasions, one female with a juvenile, and one solitary female, which may have been the same individual without her young. All sightings were in steep rocky outcrops interspersed with alpine meadows and scattered, dense high bushes of juniper and rhododendron. According to the team, the musk deer were discrete, cryptic, difficult to spot, and could not be photographed.

The authors say that targeted conservation of the species and its habitat are needed for it to survive in Afghanistan.

Although the deteriorating security conditions in Nuristan did not allow NGOs to remain in Nuristan after 2010, the Wildlife Conservation Society maintains contact with the local people it has trained and will pursue funding to continue ecosystem research and protection in Nuristan when the situation improves.

“Musk deer are one of Afghanistan’s living treasures,” said co-author Peter Zahler, WCS Deputy Director of Asia Programs. “This rare species, along with better known wildlife such as snow leopards, are the natural heritage of this struggling nation. We hope that conditions will stabilize soon to allow WCS and local partners to better evaluate conservation needs of this species.”

This study was made possible by the generous support of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). With USAID support, WCS has been helping to build Afghanistan’s capacity for sustainably managing their natural resources at both the government and community levels, including the recent creation of the country’s first (2009) and second (2014) official protected areas – Band-e-Amir and Wakhan National Parks.

October 30, 2014

Botanist Goes Missing In Action in Vietnam

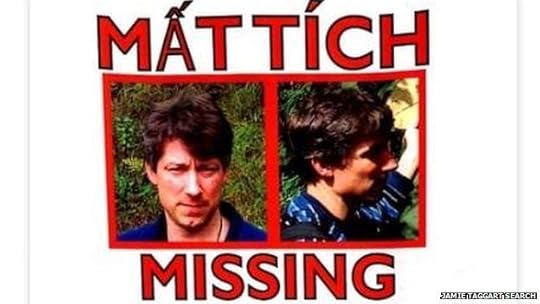

Here’s a story I’d like not to have to add to the Wall of the Dead. Please take a look, and pass on any information you may have. It’s from the BBC:

Family of missing Argyll botanist Jamie Taggart renew appeal

Posters have been distributed around the town of SapaThe father of a botanist from Argyll who went missing in Vietnam a year ago has asked anyone with any information to come forward.

Jamie Taggart, from the Linn Botanic Gardens at Cove on the Rosneath peninsula, was on a plant hunting expedition near the border with China.

Dr Jim Taggart said it would take “very freak circumstances” for his son to be found alive.

But he said “someone, somewhere must

know something” about what happened.

The 41-year-old retained fire fighter was travelling by himself, on hired motorbike taxis.

But he knew the area, having travelled there two years before he went missing.

‘Hard to disappear’

His rucksack and passport were found at his guest house in the Vietnamese town of Sapa.

Dr Taggart said it was possible eye witnesses “should not have been there”, or might not want to “get involved with local police”.

He has called for anyone with family or friends in the area to pass on any information or rumours they may have heard.

“It is very hard to disappear absolutely, completely,” he said.

But he said he had accepted it was most likely his son had slipped somewhere on a hillside and suffered fatal injuries.

People from Cove and Kilcreggan have raised thousands of pounds to fund searches for Mr Taggart.

Slowing Down the Himalayan Viagra Gold Rush

The magic stuff. (Photo: Michael S. Yamashita / National Geographic Society / Corbis)

My deep suspicion is that the rush for this “Himalayan Viagra” is a rush for fool’s gold. But this is serious business. The study notes that, “In recent incidents, in June 2014 a clash with police in Dolpo left two dead in a dispute between members of the local community and a National Park Buffer Zone Management Committee over who has the right to collect and keep fees paid by outsiders for access to yartsa gunbu grounds.”

Come on, people, it’s a fungus, and the name yartsa gunbu translates as “summer grass, winter worm.” Does that really make you imagine the peril of the infamous four-hour erection?

But I am so glad the Tibetans have figured out a way to protect the resource in the middle of this madness, and maybe there’s something here to learn for other managers of imperiled resources.

Here’s the press release:

Overwhelmed by speculators trying to cash-in on a prized medicinal fungus known as Himalayan Viagra, two isolated Tibetan communities have managed to do at the local level what world leaders often fail to do on a global scale — implement a successful system for the sustainable harvest of a precious natural resource, suggests new research from Washington University in St. Louis.

“There’s this mistaken notion that indigenous people are incapable of solving complicated problems on their own, but these communities show that people can be incredibly resourceful when it’s necessary to preserve their livelihoods,” said study co-author Geoff Childs, PhD, associate professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences.

Writing in the current issue of the journal Himalaya, Childs and Washington University anthropology graduate student Namgyal Choedup describe an innovative community resource management plan that some conservative capitalists might view as their worst regulatory nightmare.

In one remote village, for weeks in advance of the community-regulated harvest season, all able-bodied residents are required to show their faces at a mandatory roll call held four-times daily to ensure that no one is sneaking off into the nearby pastures to illegally harvest the precious fungus.

While regulations such as these might seem overly authoritarian, they’ve been welcomed by community residents desperate to get a grip on chaos associated with feverish demand for yartsa gunbu, a naturally-occurring “caterpillar fungus” prized in China for reported medical benefits. Use of the fungus as an aphrodisiac has earned it the nickname Himalayan Viagra.

October 25, 2014

Taking Fruit Bats Off the Dinner Menu to Reduce Ebola Risk

Dinner, anyone? (Photo: Reuters)

Except at Halloween, when they appeal to our sense of the ghoulish, it’s never easy to get people to care about bats. Yes, they are mammals. Yes, in the case of fruit bats, they are cute, warm-eyed mammals at that, the sort of thing that makes seals, pandas, tigers, elephants, and other “charismatic megafauna” the poster children of conservation fund-raising campaigns.

But bats are decidedly not in this category. You might just persuade people that they aren’t the bloodsucking monsters of their nightmares by reminding them that only three of the 1,250 bat species in the world are vampire bats. (Even those three mostly lick blood from open wounds, rather than sucking blood, Dracula style.) But then the story really turns ugly, because bats, and particularly fruit bats, are also the most common source of new and terrifying diseases, including SARS, Nipah and Hendra viruses, Marburg and Lassa hemorrhagic fevers, and Ebola, which turned up this week in New York City.

Epidemics of emerging disease have a way of fostering rumors and hysterical overreaction. Much as in the Middle Ages, when cats went on trial for witchcraft, wildlife often serves as a handy scapegoat. During a 2012 outbreak in Uganda, for instance, the minister of tourism, of all people, announced a plan to cull wild animals in national parks.

“We shall eliminate animals suspected to be carrying viruses of Ebola and Marburg,” Maria Mutagamba boldly declared. Never mind that tourism, based almost entirely on wildlife, is one of Uganda’s leading sources of foreign revenue. A wildlife official quietly wondered just how Mutagamba planned to accomplish her cull, given that at the very least, tens of thousands of animals inhabit these parks and do not readily line up for blood tests.

A better answer in an age of emerging diseases is not to interfere with the animals in the first place. But that often turns out to be surprisingly difficult too. For instance, a recent study in the journal EcoHealth looked at the appetite for straw-colored fruit bats as bush meat in the West African nation of Ghana. This species (Eidolon helvum) is known to carry a variety of diseases transmissible to humans, including henipaviruses, paramyxoviruses, lyssaviruses, and the big one, Ebola. Yet Ghanaians just in the southern part of the country hunt and eat about 128,000 of them every year. The species is in significant decline as a result.

The researchers found that bat hunters typically don’t use any sort of protective gear against bites or scratches, nor do they believe that they are at risk for any diseases. In some cases, when a large branch fell under the weight of its load of bats, rival hunters would fight for the catch, sometimes even lying down on top of bats to prevent others from taking them. People who ate bats commonly said they did because the meat tastes good when smoked or cooked as a kebab, or even when made into a soup with bat intestines. Bat meat also enjoys an improbable reputation as an especially healthy food (and low in cholesterol). It’s a subsistence food for some in the absence of other affordable protein sources. For others, it’s a luxury.

Ghana has managed to escape Ebola so far this year, but the alarming spread of the epidemic through five neighboring countries has the government rolling out a nationwide educational program.

That makes the new study particularly relevant, because it focused on the effectiveness of an educational program in changing people’s behavior. Such programs need to start by identifying people most likely to engage in the relevant behaviors, according to the study, and also take into account local perceptions and cultural beliefs that can affect management of an outbreak. The study tested a brief educational program that focused not just on the health risk of consuming bats but also on the environmental value of the bat population.

Bats are the primary pollinators of many tropical plants, and they disperse the seeds from fruit they eat. In Africa and Asia, that makes fruit bats “responsible for about 50 percent of the tropical rainforest there,” said Jonathan Epstein, a veterinary epidemiologist at EcoHealth Alliance, who did not participate in the study. It’s a double whammy: You can get sick to death from eating the bats, and the loss of the fruit bat population could hurt other aspects of the environment on which residents depend for their survival.

The program dramatically increased the percentage of people who believed that bats could make them sick or that bats could be environmentally beneficial. But only about 55 percent of those who hunted, butchered, or sold bats said the program was likely to change their behavior. As with cigarette smoking, unsafe sex, and a long list of other behaviors, “people can readily perceive risk and even intellectually acknowledge desire to reduce that risk,” the researchers reported, and yet not do anything about it.

While some laws limit bat hunting, the researchers also found that “essentially no one knew of the existing hunting laws in Ghana” and that “laws and fines alone are unlikely to induce change.” In the end, the study found, “there may not be a simple way to minimize the risks of zoonotic spillover from bats.”

Even if it is complex and expensive, the current epidemic makes it clear that stopping emerging diseases at the source remains the only way to prevent a pandemic here at home. What to do? When people depend on a food like bat meat for survival, said Epstein, “it’s not realistic to just take it away and not present an alternative.” A better way to minimize disease risk might be to extend the effort to instruct people in the vital importance of wearing protective gear while hunting, and of washing their hands thoroughly after preparing bats for the table.

One certain way not to protect ourselves is to cut funding to the very agencies that perform that kind of difficult training and monitoring around the world. That’s what happened as a result of the recent Republican sequester, with its indiscriminate across-the-board budget cuts. The National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, which has led the United States’ intervention in West Africa, lost $13 million from its 2013 budget as a direct result. Now it’s estimated that it will cost at least $600 million—and thousands more lives—before we can stop this epidemic.

With Ebola present in Dallas and New York, this is one of those times when investing in good government can make a life-or-death difference for us all. Keep that in mind a few weeks from now, when you cast your vote on Election Day.

October 19, 2014

Don’t Feed the Bears

Bear feeding days at Yellowstone.

Once, walking through head-high sagebrush in Yellowstone National Park, a couple of field researchers and I ran into a grizzly bear heading straight toward us, at a gallop. The bear had better things on his mind, luckily for us. It was elk calving season, and between us and him, three elk cows were racing away, pink mouths open, eyes wide with fear, trying to protect their young. They cut left, and the bear followed, moving at a rocky sprint, his loose brown flanks rippling in the sunlight, intent on hunting down his dinner.

It wasn’t maybe the safest way to see grizzlies, but for the bear it was heaven. He was visibly better off than in those long decades when the National Park Service allowed Yellowstone grizzlies to become dependent on garbage dumps and roadside tourist handouts. Since that practice abruptly ended in the 1970s, the Yellowstone bears have become wild again, learning which foods to eat in which seasons, and living by their considerable wits.

Incredibly, though, there are places in North America where the tourist-handout approach persists. In Canada’s Quebec province, travel companies bill it as “ecotourism.” They set up feeding stations on private land to provide paying guests with what they describe as a “one-of-a-kind encounter with the black bear of Quebec.” It is perhaps a reliable way to see black bears. But it borders on consumer fraud to pretend these animals are “wild.”

The feeding stations effectively domesticate the bears, changing their

behavior and feeding habits. The authors of a study in The Journal of Wildlife Management focused on a feeding station about two and a half hours north of Quebec City, in the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region. They put GPS collars on bears near the feeding station and also on bears several kilometers away, known not to frequent the feeding station. Then they started taking notes.

Bears at the feeding station did what you might expect: They sat and ate. And ate some more. On average, those bears weighed about 40 percent more than their wild-foraging counterparts. Their home ranges shrank to about a third of the size of a wild bear’s home range. They also crowded around the feeding station at a much higher density than is typical in the wild. Just about the only thing missing was a television and a couch.

The food left for the bears is often garbage by another name, consisting of scraps and frying oil. “This diet is certainly not very good for bears,” said Christian Dussault, a researcher at the Quebec Ministry for Forestry, Fauna, and Parks and an author of the paper. The increased weights of the bears may, however, mean that they’re able to breed sooner and more frequently, because females can reproduce only once they’ve achieved a certain weight. Over time, this may change the population dynamics of black bears in the area.

That’s not necessarily a good thing. A paper published this summer in Biology Letters detailed how feeding wild animals helps spread pathogens and disease through a population, by bringing more animals into closer contact than would occur in the wild. While the black bear study did not evaluate the bears’ health, Dussault said that it is possible that the fed animals could also have higher rates of disease. Moreover, the tendency of the bears to hang out within about a kilometer of the feeding station creates a potential hazard not just for them but for people in the area. Too many bears artificially attracted to one site could “result in increased human-bear conflict in the same area.”

This is the first study to quantify how bears behave around feeding sites. The data could lead to regulatory standards for the 50 or so such feeding stations in the province, Dussault said. It may also help wildlife managers or lawmakers figure out where—or whether—it would be safe to locate a new feeding station.

So what’s a family that wants to see bears—but doesn’t want to patronize feeding stations—supposed to do? Buy a good set of binoculars, park in a likely location (ask park rangers or local naturalists for a hint), and pay attention to the elk or other prey animals. They’ll point and stare or even walk straight toward an approaching predator. That’s your big clue.

It may sound easier to just feed the animals and let them come to you. But the very act of feeding a wild animal makes it less wild. You and your kids will be a lot more thrilled, and more inspired, observing one bear under natural conditions than seeing dozens of them looking for a handout.

October 16, 2014

That Transmission Line You Hate? It Could Be Pollinator Habitat

My latest for Yale Environment 360:

Nobody loves electrical power transmission lines. They typically bulldoze across the countryside like a clearcut, 150 feet wide and scores or hundreds of miles long, in a straight line that defies everything we know about nature. They’re commonly criticized for fragmenting forests and other natural habitats and for causing collisions and electrocutions for some birds. Power lines also have raised the specter, in the minds of anxious neighbors, of illnesses induced by electromagnetic fields.

So it’s a little startling to hear wildlife biologists proposing that properly managed transmission lines, and even natural gas and oil pipeline rights-of-way, could be the last best hope for many birds, pollinators, and other species that are otherwise dramatically declining.

This Lasioglossum sopinci specimen, a rare species of sand-specialist bees, was found along a power line right-of-way in Maryland’s Patuxent Wildlife Research Refuge. (Photo: Sam Droege/USGS)

The open, scrubby habitat under some transmission lines is already the best place to hunt for wild bees, says Sam Droege of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland, and that potential habitat will inevitably become more important as the United States becomes more urbanized. He thinks utility rights-of-way — currently adding up in the U.S. to about nine million acres for power transmission lines, and another 12 million for pipelines — could eventually serve as a network of conservation reserves roughly one third the area of the national park system.

Remarkably, some power companies agree. Three utilities — New York Power Authority, Arizona Public Service, and Vermont Electric Power Company — have already completed a certification program from the Right of Way Stewardship Council, a new group established to set standards for right-of-way management, with the aim of encouraging low-growth vegetation and thus, incidentally, promoting native wildlife. Three more utilities, all from Western states, are currently seeking certification.

“Whether the other few hundred will be similarly interested, we don’t know. We hope they’ll see the value,” said Jeffrey Howe, the council’s president. The gist of the program is straightforward: Federal regulations currently require power companies to keep their transmission line corridors free of large trees and other tall vegetation. Beyond that, though, there is nothing to require the common practice of routinely mowing everything down to grass, or broadcast-spraying herbicides. So instead, some utilities have shifted to spot-spraying herbicides on unwanted plants, and letting everything else grow in to form a scrubby habitat of wildflowers, sedges, ferns, and low shrubs. It’s called Integrated Vegetation Management, or IVM.

Australian utilities have already expressed interest in the program, as have pipeline companies, said Howe. The Brazilian utility CEMIG is also independently testing a similar management style at a pilot site in the Atlantic coastal forest and another in dry upland forest. Power line corridors in Europe generally run across industrialized farmland meaning utilities there have so far seen little potential to manage them as habitat.

In the United States, said Howe, traditionally risk-averse utility executives “don’t want to spend money on something until they know, first, that it’s going to be valued in the world and, second, that they’re doing the right thing.” One aim of developing the new vegetation-friendly standards now is to reassure them on both points. The standards may also “affect how things are regulated five or ten years down the road,” he said.

Even for companies that have pioneered the IVM idea, wildlife habitat wasn’t the idea. “We kind of backed into this,” said Anthony W. Johnson, III, who manages 2,500 miles of transmission corridors in New England for Northeast Utilities. “We really haven’t managed for wildlife. We manage to prevent certain vegetation from encroaching. We try to keep some things out, and in doing this, we wind up encouraging native low-growth.” Native wildlife was a happy side effect.

“The frosted elfin butterfly is a globally imperiled species, and in southern New England, most of the occurrences are under power lines,” said University of Connecticut entomologist David Wagner. Likewise, “the Karner blue butterfly is drop-dead gorgeous, and a poster child of the conservation movement, and at least in the eastern part of its range, its existence is dependent entirely on power lines.” In one IVM transmission line, Wagner recently re-discovered a wild bee species, Epeoloides pilosula, which had not been seen in the U.S. since 1960.

“The transmission lines are probably critically important for a lot of these early successional species,” said Robert Askins, a Connecticut College ornithologist. That’s partly because the heavy reforestation of New England over the past century has eliminated most other open habitat, and partly because the rights-of-way are permanent. They’re also corridors, and even networks of corridors, which means individual populations of a species can connect with one another instead of becoming genetically isolated. In studies by Askins in Connecticut, power line corridors provide habitat for now scarce birds like the brown thrasher and the yellow-breasted chat (a state endangered species).

Against all odds, IVM power line corridors are sometimes also beautiful. Kimberly N. Russell, an ecologist at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, describes one site she studied, near Lookout Point Lake in Oregon, as a sort of garden spot. “You’re surrounded by evergreen closed-canopy forest and then there’s this explosion of color, this linear streak of color, and it’s all wildflowers.”

That’s not something anyone would say about utilities’ traditional management methods. In Columbia, Maryland, for instance, Baltimore Gas & Electric (BG&E) went into an area it hadn’t been able to maintain for several wet years and cut down everything, inadvertently enraging local residents. The ensuing conversation resulted in a pilot IVM project there, and it now includes walking trails and informational signs about plants and wildlife. The company is also starting to implement IVM elsewhere in its system, said William Rees, a BG&E vegetation manager. “It’s taking a little bit of a leap of faith, but early indications are that it is cost effective, on an operational basis.” As the scrub vegetation grows in, it excludes many taller trees, he said, and somewhere between three and seven years after abandoning mowing and broadcast spraying, “costs drop dramatically.”

If it saves money (and provides public relations bonus points), why don’t more utilities manage their power lines this way? “One of the stumbling blocks they face is that they have long-term contracts with mowers,” said Russell, “and these are old school relationships. So there’s lots of pushback.” In addition, some communities are uncomfortable with herbicide use, though IVM proponents say it’s far safer and used in much smaller amounts than in the past.

Utilities also get resistance from their own foresters, said Rick Johnstone, a former power company manger who is now an IVM consultant, “because it’s more work to manage.” Conventional methods allow a forester to “sit in the office and say it’s 2014, it’s time to mow that line. But when you get into IVM, you need to look at it, you need to do the assessment, and determine what’s the best practice. What’s the vegetation growing there? What’s the density of vegetation? Are you near water? And that takes more expertise.”

Federal rules are also an impediment. Interference from trees and unpruned foliage did not cause the widespread 2003 power blackout in the U.S. Northeast, but they made it worse. Under rules that were subsequently revamped to ensure reliability of the grid, utilities that fail to control vegetation now face fines by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation of up to $1 million a day.

That’s “had a huge effect on the way some utilities manage their systems,” said John Goodrich-Mahoney of the Electric Power Research Institute. “Some utilities became more aggressive in removing all vegetation from the transmission corridor, and also clearing right to the edge of the right-of-way.” Some even worked with landowners beyond the right of way to remove trees that might potentially cause fall-ins. But “that very aggressive response is now starting to swing back to a middle ground, where companies are more comfortable having some vegetation.”

Northeast Utilities manager Anthony Johnson cautioned that conservationists need to be realistic about what power line corridors can do for wildlife. Seeding a right-of-way with milkweed for monarch butterflies, for instance, may sound like a natural, but it will work only where it already grows naturally. “It’s much easier selectively removing what you don’t want than to try to put in things that you do.”

On the other hand, when biologists came to him a few years ago and pointed out that scrub oak is an essential habitat for at least 15 regionally threatened moth and butterfly species, it wasn’t a close call. “It turns out that it has significant value to the frosted elfin butterfly,” said Johnson, a consideration that other, more traditional utility managers might not be comfortable even saying out loud.

“Now instead of spraying it, we cut it when it gets to be about eight feet in height.” Does that entail an extra cost to the power company? “Not at all,” he said. “Zero.”

October 15, 2014

Under Pressure, Texas Moves to Stop Ocelot Traffic Deaths

(Photo: Ana Cotta)

A few weeks ago, I wrote a piece for Takepart about the only U.S. population of the endangered ocelot suffering from roadkills because of poor planning on Texas State Highway 100. Among other things, I asked readers to phone or email to let the Texas Department of Transportation know how they felt about that.

Now TexDot, as it’s known, says it’s going to fix the problem. It’s not clear whether this is a smokescreen or the beginning of a genuine improvement. I’ll keep an on it to see what really happens, and whether it happens soon enough to make a difference. Meanwhile, here’s the report from ValleyCentral.com

Funding has been secured for four ocelot crossings on Highway 100 between Laguna Vista and Los Fresnos.

After four of the endangered cats were killed on the busy road and years of meetings with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) is prepared to construct four wildlife crossings beneath the roadway similar to this one on Highway 48 near the Port of Brownsville.

Regional TxDOT spokesman Octavio Saenz spoke to the Nature Report about the project.

“We secured funding for four crossings,” Saenz said. “We are still in negotiations or talks, I should say regarding the size of two of those crossings.”

With less than 50 of the rare cats estimated to remain in the wild,

biologists with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are relieved to learn that funding for the vital crossings is finally in place.

Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge Manager Boyd Blihovde supports the project.

“It’s great news for ocelots, and we are really happy that TXDOT has taken it seriously on Highway 100,” Blihovde said. “Obviously, from the top down they are taking ocelot conservation seriously and wanting to protect them, and we are glad for that.”

Some $5 million dollars has been allocated for the four crossing on Highway 100, and construction should begin next year.

“Hopefully, the summer of 2015 and we are looking to get it done as soon as possible,” Saenz said.

Blihovde said the project is very timely given the recents deaths of ocelos along the busy road to South Padre Island.

“We just hope that it happens really soon, because the longer we wait the more chances there are for ocelots to get hit on Highway 100,” Blihovde said. “You know, two ocelots were hit on Highway 100 during this previous year, and so two in one year is a lot of ocelots when we only have eleven that we are monitoring here on Laguna Atascosa.”

The only thing left now, is start moving dirt.

“The funds are available, and now it is time to get to work,” Saenz said.

With your Nature Report, I’m Richard Moore

I asked a local ocelot activist to comment and got this response:

There is some genuine good, assuming the crossings actually get built and get built in a timely manner. However, I understand there have been many empty promises from TXDOT in the past. Also, we wanted 5 crossings not 4 and short-term, more importantly, we strongly recommended that they remove the concrete barrier, or at least install metal beam guardrail fence at 150 ft. intervals. They essentially blew off this extremely crucial recommendation.

So, you’ll hear some Fish and Wildlife Service people celebrating, but the jury is still out for me. TXDOT has wasted no time patting themselves pretty hard on the back, of course.

More to come.

October 13, 2014

How Beavers Build Biodiversity

It’s not postcard pretty to human eyes. But it’s habitat to wildlife.

Even species as small and relatively uncharismatic as beavers produce dramatic changes in the environment, to the benefit of many species and the detriment of others. This press release caught my eye partly because of the debate over how reintroduction of wolves has changed Yellowstone National Park. It’s also of interest because the British, who seem t0 suffer from a profound fear of their native wildlife (wolves, bears, badgers), are currently debating reintroduction of beavers (with much “we shall fight in the fields and in the streets” rhetoric):

Felling trees, building dams and creating ponds — beavers alter the landscape in ways that are beneficial to other organisms, according to ecologist Carol Johnston of South Dakota State University.

“Beavers influence the environment at a rate far beyond what would be expected given their abundance,” said Johnston, who is now completing a National Science Foundation grant to study how beavers have affected the ecosystem at Voyageurs National Park, near International Falls, Minnesota. She’s been doing beaver research there since the 1980s.

Beavers create patchiness because they cut down big trees and make dams that flood the landscape, creating wet meadows and marshy vegetation, Johnston explained. Historical and aerial photos from 1927 and 1940 showed solid forests, meaning little evidence of beaver activity. But from the 1940s through the 1980s, the beaver population in the nearly 218,000-acre park increased steadily. By 1986, 13 percent of the landscape was impounded by beavers.

“We saw lots of ponds where before there were none,” she said. Ducks, amphibians,

moose, and upland mammals use this habitat extensively. “Having beaver on the landscape creates a lot of biodiversity.”

Beaver numbers have been decreasing since 1991, probably due to depleted food supply and increased predation.

“Aspen is the preferred food,” Johnston said. Beavers forage up to 110 yards from the pond edge, leaving behind what Johnston calls a “bathtub ring of conifers” when most of the aspen and deciduous trees have been harvested. Venturing beyond that comfort zone makes them susceptible to predators, she pointed out.

“Beavers are a preferred prey for wolves.”

October 11, 2014

Got a Favorite Beer? Thank a Fruitfly For That

When I am not thinking about wildlife, I am often thinking about beer. So it’s nice (and also sort of icky) to see these two interests come together in a study showing that fruitflies give beer its flavor. Interesting that the study comes from Belgium, home of some of the more aromatic beers. (Do beer flavors vary regionally depending on the Drosophila species?) Also not in the least surprising that the researcher got the idea for this work as a graduate student.

When I am not thinking about wildlife, I am often thinking about beer. So it’s nice (and also sort of icky) to see these two interests come together in a study showing that fruitflies give beer its flavor. Interesting that the study comes from Belgium, home of some of the more aromatic beers. (Do beer flavors vary regionally depending on the Drosophila species?) Also not in the least surprising that the researcher got the idea for this work as a graduate student.

I suppose the fruitfly-beer connection shouldn’t seem all that novel because I have often used a small dish of beer to attract and kill fruitflies around the kitchen. But the idea that the fruitflies have contributed to the taste of beer suggests I need to think about them more kindly. To butcher A.E. Housman a bit, “Malt does more than Darwin can/to justify the ways of Drosophila to man.”

I’m going to shut up now and go to the press release:

Meet the bartender

The familiar smell of beer is due in part to aroma compounds produced by common brewer’s yeast. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Cell Reports have discovered why the yeast make that smell: the scent attracts fruit flies, which repay the yeast by dispersing their cells in the environment.

Yeast lacking a single aroma gene fail to produce their characteristic odor, and they don’t attract fruit flies either.

“Two seemingly unrelated species, yeasts and flies, have developed an intricate symbiosis based on smell,” said Kevin Verstrepen of KU Leuven and VIB in Belgium. “The flies can feed on the yeasts, and the yeasts benefit from the movement of the flies.”

Verstrepen first got an idea that this might be going on about 15 years ago as a graduate student studying how

yeast cells (formally known as Saccharomyces cerevisiae) contribute to the flavor of beer and wine. He discovered that yeast cells produce several pleasing aroma compounds similar to those produced by ripening fruits. It turns out that one yeast gene in particular, called ATF1 for alcohol acetyl transferase, was responsible for the lion’s share of those volatile chemicals.

An accidental escape hinted at what those scents might be good for: “When returning to the lab after a weekend, I found that a flask with a smelly yeast culture was infested by fruit flies that had escaped from a neighboring genetics lab, whereas another flask that contained a mutant yeast strain in which the aroma gene was deleted did not contain any flies,” Verstrepen recalls.

But it wasn’t until years later, when he teamed up with fruit fly neurobiologists Emre Yaksi and Bassem Hassan, that the story finally came together.

Using a combination of molecular biology, neurobiology and behavioral tests, the researchers now show that loss of ATF1 changes the response of the fruit fly brain to a whiff of yeast. As a result, the flies are much less attracted to the mutant yeast cells, which in turn results in reduced dispersal of mutant yeast by the flies.

Together, the results uncover an intriguing aroma-based communication and mutualism between microbes and insects, the researchers say. They suspect that similar mechanisms may exist in other plant-associated microbes, including pathogens.

In fact, the research team has isolated many different yeast species from the bodies of fruit flies in nature to find that the vast majority of those yeasts produce aroma compounds. They have also isolated several strong aroma-producing yeasts from flowers.

“These preliminary results suggest that aroma production is not restricted to S. cerevisiae and may be a much more general theme in microbe-insect interactions,” the researchers write.

An App To Help Cops Spot Illegal Wildlife

(Illustration: John Gould)

One of the unintended consequences of sending the United States military abroad is to promote illegal trafficking in wildlife. Young soldiers typically want souvenirs of their foreign service, and neither military patrol officers on bases abroad nor customs agents back home can usually tell whether, say, that fur hat is made from Eurasian lynx (illegal) or Corsac fox (not wonderful, but OK).

Heidi Kretser, a social scientist from the Wildlife Conservation Society, was living in upstate New York in 2008 when nearby Fort Drum was training and mobilizing 80,000 troops a year, many with deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. She thought she could help with training programs, handouts, and a video about illegal wildlife products. But frequent turnover, especially among M.P.s, meant that it was difficult to train everyone, or make that training stick.

Later, she saw the problem firsthand in Afghanistan, where merchants coming onto military bases for weekly or monthly bazaars routinely sold fur coats from Eurasian lynx, skulls and horns of Marco Polo sheep, and even snow leopard pelts. Soldiers, contractors, and international aid workers also frequented the wildlife market known as “Chicken Street” in Kabul. Sweeps of bases by military police turned up hundreds of contraband wildlife products, and a survey back at Fort Drum found that 40 percent of soldiers had either purchased or seen other soldiers purchase wildlife products while abroad.

To help fix the problem, Kretser has produced a smartphone app called Wildlife Alert that gives law enforcement officers a mobile decision tree for figuring out whether or not a wildlife product from Afghanistan is legal. Writing in the journal Biological Conservation, Kretser and her WCS coauthors also announced the development of a similar app, called Wildlife Guardian, already being tried out by forest police and customs officers to address rampant illegal wildlife trafficking in China.

Neither app attempts to turn cops into taxonomists. The apps are merely tools, Kretzer said, “that help people

make a decision in the field, to say, ‘Yeah, I don’t want to let this by without further expert advice.’ ”

In Afghanistan, Kretzer said, the merchandise typically involves products rather than whole animals, “so you usually just have the fur, or part of the horn, or some part of the animal not diagnostic to species.” But simply being able to recognize that the fur comes from a cat, without knowing whether it’s from Prionailurus bengalensis (the leopard cat), say, is good enough, because all of the country’s nine cat species are in trouble. “Our app is set up to try to be conservative about what can go through, to avoid false negatives,” she said.

The Chinese app, on the other hand, is geared toward identifying whole animals. The decision tree for birds, for instance, asks the user to narrow down the possibilities by answering simple questions about body size, body shape (is it more like an eagle or a duck?), beak shape, claw shape, and plumage color.

In the demonstration case, police investigating birds being sold at a pet shop in Guangzhou answer those questions and narrow down the possibilities to a single species, Derby’s parakeet, a Himalayan native now protected under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species.

The Chinese app covers 457 species (versus just 75 for Afghanistan) and 15 wildlife products, with biweekly updates and backup confirmation by experts within eight hours. In Vietnam, where smartphones are less common, a similar decision-tree program, covering 152 species, is now available as a website.

The U.S. military version of the app is just going into service at bases in Afghanistan. But about 1,000 law enforcement officers have downloaded the Chinese app so far, according to Aili Kang, the director for WCS China, and 100 have logged in by name. Training has so far concentrated on Guangdong and Guangxi provinces, both known for their illegal wildlife trade. Kang said the ambition is to take the app national.

Will it lead to important arrests? Will it slow the trafficking in wildlife? For cops and customs officers trying to make sense of the alarming stampede of wildlife products they now encounter every day, having a sort of smartphone taxonomist in their pocket is at least a start.