Richard Conniff's Blog, page 43

August 19, 2014

An Elephant Story That Should Resonate for Modern China

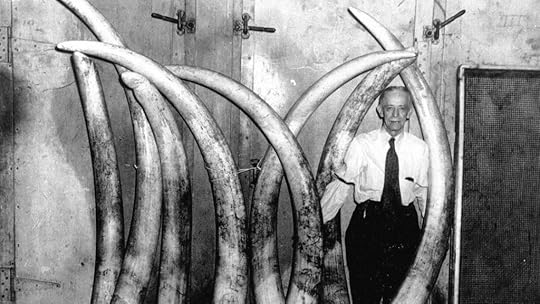

Tusks in the factory at the end of my old street in Deep River, CT

Back in 1987, when Audubon Magazine had a more ambitious and expansive view of its role in the world, a great editor there named Les Line gave me an assignment to write about a story that had turned up literally on my doorstep. At that point, I was traveling all over the world reporting stories on wildlife. So I was startled, one day at home, to discover that the town where I had bought my first house had once been the center of the ivory trade in the Western Hemisphere.

It turned out to be an especially interesting story for me, as I dug into it, because the nineteenth century founder of the ivory company at the end of my street had also been a leading abolitionist. But he had somehow never noticed that his business depended entirely on the slave trade in East Africa.

The resulting story of moral complication, “When The Music In Our Parlors Brought Death to Darkest Africa,” still resonates for me personally, and apparently also for others in the context of the modern slaughter of elephants. NPR’s “Morning Edition” nicely paraphrases that original Audubon piece (with a few minor mistakes) in today’s show. It’s only seven minutes long and worth a listen.

If you’re interested in hearing more, here’s an interview I did a while back with NPR’s Colin McEnroe, about what China can learn about the ivory trade from small town Connecticut. It runs 10 minutes, starting at 38:00: http://wnpr.org/post/tuesday-tumble-eddie-perez-rent-trumbull-snowy-owls-tarmacs-ivory-trade-ct … … And here’s a piece I published here on the same topic.

I keep meaning to publish that original Audubon piece as an e-book, and maybe one of these days I will get around to it. Will keep you posted, if so.

UPDATE:

New York (August 19, 2014) – The following statement was issued by John Calvelli, WCS Executive Vice President of Public Affairs and Director of the 96 Elephants Campaign:

“Today’s landmark study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, authored by 96 Elephants partner Save the Elephants and other groups, confirms the widespread slaughter of elephants throughout Africa driven by ivory poaching. These tragic numbers underscore

the urgency of banning the ivory trade. Recent WCS research has shown that any legal trade of ivory will only embolden organized crime syndicates to continue poaching and smuggling.

“Strong ivory bans recently passed in N.J. and N.Y. give us hope that the political will is there to pass state bans. However, the proposed federal ivory ban is under attack in Congress by the anti-ivory ban supporters. We hope that today’s news showing the loss of 100,000 elephants over the past three years will serve as a wake-up call that now is the time to ban ivory before these magnificent creatures are lost forever.

“The 96 Elephants campaign – named for the number of elephants killed each day – will continue its work through its 160 coalition partners, including 120 North American Zoos, to stop the killing, stop the trafficking and stop the demand.”

To learn more about the elephant crisis and how to help eradicate the demand for ivory, visit www.96elephants.org.

August 18, 2014

“We Kill Lions All The Time”: Inside the Anti-Predator Mindset

Whether they are trying to stop the killing of wolves in Idaho or lions in Tanzania, conservation biologists often come to a horrible moment when they realize that all their training has missed the mark. “I often think that I have three degrees in wildlife biology, and none of them is relevant to what I do on a daily basis,” says Amy J. Dickman, a senior research fellow at Oxford University. What she needs, more often than not, isn’t ecology. It’s psychology.

That thought occurred especially during two years she spent camped under a tree with two Tanzanian assistants, trying to make contact with a community of pastoral grazers, members of the Barabaig tribe. She was working on strategies to protect predators on the outskirts of Ruaha National Park. It’s Tanzania’s largest national park, as big as the state of New Jersey. It’s home to 10 percent of the world’s population of lions, the third-largest population of African wild dogs, one of East Africa’s largest populations of cheetahs, as well as leopards, spotted hyenas, and other predators. All of them face “intense human-carnivore conflict and frequent carnivore killing,” says Dickman, who works with the Ruaha Carnivore Project.

The Barabaig had the usual livestock herders’ reputation for hating predators. They were also said to be secretive and hostile to outsiders. From time to time, Dickman’s team would hear celebrations, with singing, dancing, and people imitating lion calls. When they walked closer to find out if there’d been a killing, warriors with spears

blocked the way, telling them it was just a wedding, “nothing to do with lions.” After one member of the community was seen talking with Dickman’s team, she says, he was “quite badly beaten up.”

But then the researchers set up a solar station, with the sole idea of being able to recharge their laptops, and that was the unexpected breakthrough. “The Barabaig all started showing up to recharge their cellphones,” she says, meaning they could talk to the researchers “without looking like a snitch.”

Eventually, the Barabaig agreed to take one of the Tanzanian assistants with them, “and they showed us seven carcasses of lions, all very fresh. They told us, ‘We kill lions and hyenas all the time.’ ” Over an 18-month period, “just around that one tiny village” the research team recorded 35 lion kills. Many of the lions had their right front paw cut off, which turned out to be a key to the Barabaig’s anti-predator culture.

When there is a problem lion, “lots of guys go on the hunt,” says Dickman, eventually cornering the lion. Then they choose the bravest warrior to walk up to the lion, unarmed, as bait. In turn, he has picked the best warrior to stand behind him with a spear, ready to kill the lion as it charges. Young warriors vie for both jobs, says Dickman, because they bring status in the community and the attention of women. The one with the spear gets the added privilege of cutting off the lion’s paw and wearing the middle claw as an amulet. He then goes around the village collecting livestock as a reward and as one of the only available ways of building wealth.

For Dickman, understanding the psychology of lion killing is a way to begin to prevent it. The researchers were able to interview 262 people in 19 villages around the park, for a paper just published in the journal Biological Conservation. Like livestock herders everywhere, people said they hated predators because of attacks on both livestock and humans. But beyond the attacks, says Dickman, hostility to wildlife is often rooted in “rarely considered social factors,” including “perceived disempowerment” in regard to wildlife use, “poor relationship with the park, and a lack of benefits from wildlife.” Just 2 percent of people said they received any wildlife-related income, she says.

Dickman says the “contagious conflict” idea normally applied to warfare, rebellion, and justice also applies to wildlife. So “someone else’s problems with carnivores or other species might heighten a respondent’s antagonism, even toward species that they have not directly experienced problems with.” One villager’s problem with a lion can cause another neighbor to kill cheetahs, and because the memory of an attack tends to persist, the killing can go on for years after the problem has gone away.

As a practical measure, Dickman’s group is now trying to reduce attacks by reinforcing corrals with proper fencing, a measure that has been 99 percent effective, she says, and it is also introducing guard dogs to drive off predators.If the owner of the corral pays half the cost of the improvement, he also gets access to a veterinary health program. That’s a big deal because disease kills nine times more animals than do predators. The researchers also bring herders into the park and into conversations with park staff. (“These are people who live within 30 kilometers of the park, and they’ve never been inside.”) Seeing predators in an unthreatening context—for instance, grooming their young—can also begin to subtly shift attitudes. Finally, the researchers are working to link the presence of wildlife in the community to the benefits villagers want, notably education and health care.

It’s still in a way about ecology. But Dickman has learned that if she hopes to save lions, wild dogs, cheetahs, and other threatened species, it’s really the human ecology that counts.

Cape Cod Not So Welcoming to Latest Wave of Visitors–Seals Part I

It’s a sunny morning early in June, and the scene at the Fish Pier in Chatham, Massachusetts, on the elbow of Cape Cod, is a perfect split-screen image of the Cape’s bipolar personality: On the upper deck, 40 or 50 tourists at a time line the rails, cooing and sighing every time a gray seal rises in the green water below and shows its glossy dark eyes. Meanwhile, at ground level, just below, the commercial fishermen unloading their meager catch darkly curse the seals as their worst enemy.

Someone calls down a question from the deck, and an older fisherman with battered teeth and tattooed arms answers. “This water used to be loaded with stripers,“ he begins amiably. “I used to bring my kids here at the end of the day to fish. Now the stripers are all gone. The seals ate ‘em,” he says, revving himself up. “They eat 200 or 300 pounds of fish a day.” And then the closer: “There are hundreds of seals here that we all want to kill.”

The tourists nod politely, aghast. Kill seals? It is illegal, and besides, they are too cute.

But even some tourists have lately begun to wonder just how much cuteness Cape Cod can stand. From a few dozen seals in the early 1990s, the local population of gray seals has boomed to upwards of 15,000. It represents a dramatic recovery for a species that was largely extirpated from the Cape in the nineteenth century, and it’s a triumph for the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. But to some people it also looks like way too much of a good thing.

On Cape Cod, the main “haulout,” where gray seals come ashore to rest and to reproduce, is on Monomoy, the strip of uninhabited barrier islands extending eight miles south from Chatham into Nantucket Sound. But these days there’s hardly a beach from Falmouth to Provincetown, or on the islands, where seals don’t visit, sometimes hundreds of them at a time. This booming population has brought about a sea change for both beach-going tourists and the traditional working Cape alike.

Most sensationally, great white sharks

(Photo by Shelly Negrotti)

now routinely patrol the Cape in search of seals for dinner–and they sometimes make mistakes: Early in July 2012, a novice kayaker off Nauset Beach in Orleans turned around to see the dorsal fin of a great white bearing down on him. He managed to paddle furiously to shore, tumbling into the surf just as the shark turned away. Three weeks later, a great white grabbed a swimmer off Ballston Beach in Truro. He also survived, after a frantic and bloody race to the beach. The two incidents sent a voyeuristic thrill racing across the Cape and introduced a new sense of trepidation to the simple joy of playing in the surf. They also gave the fishermen a slightly perverse cause for hope.

“You know how we’re going to get rid of the seals?” says a charter boat captain at Chatham Fish Pier that morning in June. He gestures seaward with an open-end wrench. “A shark is going to eat some fat lady from New Jersey. Then they’ll go, ‘Oh, my god, we’ve got a seal problem.’” He wonders aloud if his website should feature a picture of Captain Quint, from the movie “Jaws,” filmed just across the water on Martha’s Vineyard. “You wait,” he growls, wishfully. “This summer we’re going to see some action.” (To be continued)

The Biology of Diving–Seals Part 2

“That one there is a female,” Keith Lincoln tells the tourists on his 32-foot seal-watching boat Rip Ryder. “See her brindle coat? Come on now, sweetheart. Look at that cute little ice cream-cone face. Wait till you see one of the big males. They get ugly.” Males can weigh up to 800 pounds, about twice as much as females. Their faces are dog-like, with a dignified Roman nose bump. The species name Halichoerus grypus means “hooked-nosed sea pig.”

Lincoln, a Harwich police patrolman by night, runs Monomoy Island Ferry and Seal Cruises by day, and over the idling of twin 250-horsepower Evinrudes, he delivers a knowledgeable introduction to the strange biology—even the biochemistry—of seals. Right now he’s telling his passengers that a diving seal can stay underwater for up to 20 minutes. “How do they manage it?” he asks. Trick question. A passenger ventures that they must have enlarged lungs.

“When you dive down to 500 feet,’ says Lincoln, “the last thing you want is two big balloons full of air in your chest.” Instead, seals flood the pockets of their lungs with plasma to solidify them against the intense atmospheric pressure. They also drop their heart rate as low as 10 beats per minute. “Gray seal blood has three to five times more hemoglobin than ours,” says Lincoln, “so it can carry more oxygen out to the muscles.” The muscles likewise contain more myoglobin, so they can hold onto oxygen longer. To prolong their dive time, the seals also turn off liver, kidneys, and all other functions that are at least temporarily unnecessary. “You and me are just big F150 trucks. We motor through it,” Lincoln tells his passengers. But a diving seal is all about efficiency.

That matters, he explains, because it influences what a gray seal eats—not 200 pounds in a day, but more like 20 or 30, and not the sort of fish that would interest a commercial fisherman, but sand eels. They’re slender little fish that burrow into the bottom with only their heads exposed to feed on drifting copepods—until a seal comes along to snap them up. A study of seal scat on Cape Cod found that sand eels make up 48 percent of the local seals’ diet. Striped bass and bluefish did not show up at all, says Lincoln, because seals are not built for high-speed chases. “Eight hundred pounds and exercise is a bad thing,” he tells his passengers. “Easy livin’, that’s what it’s all about.”

New England fishermen have always believed otherwise, viewing seals as their worst, or at least their most visible, competition. From 1888 to 1962, Massachusetts and Maine together bounty-hunted up to 135,000 seals, enough to make them scarce throughout New England. Older men on the Cape can still recall the last few seals that occasionally showed up when they were boys in the 1950s. They generally shot them and handed in their noses to collect a $5 bounty.

“You can argue with me all day if you want,” says Lincoln, “but I can tell you that seals do not deplete the commercial fishery. There are no fisheries to deplete. They were killed off by our fishermen. What killed them off was technology—gill nets, and bottom trawling, and depth finders that can find a fish at a thousand feet. The fish don’t have a chance.”

Though he does not say so to his customers, Lincoln will also happily tell his neighbors that the coming of the seals to Cape Cod is a good thing economically, even for a traditional fishing community like Chatham. “There are five seal-watching companies in the area, and we each carry 5000 to 7000 people a year,” he says. It’s not just what customers pay to see the seals ($35 a person on Lincoln’s boat), but also what they spend before or after for a meal in town. He figures that adds another $1 million to the local economy.

Is There a Market for Seal Meat?–Seals Part 3

Eldridge and crew heading seaward

Plenty of fishermen, on the other hand, are prepared to argue just as stubbornly (but not so happily) about what’s been lost. At dawn on a late spring morning, Ernie Eldridge sits back on the engine housing of his 28-foot open boat, hands folded across his stomach, the right hand now and then casually reaching down to tweak his course seaward out of Chatham’s Stage Harbor. He’s 63 years old, with hanks of white hair flying out from under his cap, over sea-bleached blue eyes, weathered cheeks, and a yellowing beard. He started fishing these waters with his father at the age of 10, using a technology that dates back to the Cape’s original Wampanoag inhabitants. He is now the last weir fisherman still working on the Cape, for reasons that quickly become apparent.

Approaching the weir.

A weir is a structure set up in the balmy winds of a New England March, a mile or so offshore, by driving 125 or so hickory poles, each about 40-feet long, 10-feet deep into the sandy bottom. They form a long straight line, called the leader, and when rigged with nets, they steer fish along their length into a heart-shaped pen, and then through a narrow gate into “the bowl,” which has a net strung across the bottom. Or that is what they would do, says Eldridge, if there were more fish and fewer seals.

As the boat pulls up to the first weir, the seals poke their heads up out of the water on either side of the leader and stare curiously, almost gratefully, as if to welcome their provider. A few years ago, a graduate student did a sonar study at one of Eldridge’s weirs and recorded 290 seal crossings at the gate in a day. Now Eldridge keeps the gate fenced off and has a birdcage of nets rigged high around the perimeter, to keep seals from clambering over the top.

“But they still intercept the fish as they’re coming up the leader and they scatter them,” he says. When the sonar was in place, he could actually watch as a school of squid, his target species, moved up along the leader. Then the seals appeared and the squid spun around in the opposite direction. “They break up the whole school of fish,” he says.

Eldridge, his daughter Shannon, and two other crewmen spend 45 minutes cinching in the net on the first of four weirs. It’s heavy hand-over-hand work, made harder by several tons of brown algal crud, a byproduct of excess nitrogen from too many houses and too many fertilized lawns along the shoreline. For their trouble, they come up with a mess of inedible spider crabs, a fish skeleton stripped bare, and a solitary squid. “That’s fishing in the twenty-first century,” says Eldridge. “And that’s why we don’t have a lot of competition.” He’s thinking about switching over to mussel farming, where the seals might pose less of a problem.

##

Other, angrier fishermen just want to take matters into their own hands, if only symbolically for now: At his home on the Cape, one commercial fisherman sometimes serves canned seal meat on Ritz crackers, “like pate,” he says. He also keeps a bottle of omega three pills made from seal oil. You can buy either at the grocery in Canada’s Maritime Provinces, where harvesting seals is a venerable, if controversial, tradition. In this country, even owning such products is a federal crime. But that only makes them more appetizing.

“I don’t want an all-out slaughter of seals,” he says. What he wants is to modify the Marine Mammal Protection Act to arrive at “a better balance between seals and people.” That could mean permission to harass seals to keep them away from fishing gear, he suggests. It could mean birth control for seals. Or it might mean an annual cull: “What are the alternative uses for a dead seal? Is there a meat market, a fur market, an oil market? And it turns out there is a market for all these things. Maybe we could have a fishery that targets seals, with a quota attached to it?”

Then, in the next breath, he recalls why such a thing will almost certainly never come to pass. It’s not the law. It’s not the bipolar Cape Cod personality, half cooing, half cursing. It’s human nature. When you look at a month-old human baby, he says, “The first thing you see are the big round eyes and the bald head, and your heart melts. This is an evolved trait. It happens to you without you knowing it.” By coincidence, seals elicit the same emotional response, he says. “You see the big eyes, the bald, round head, and the cute-ish look that it gives you, and you automatically become its protector.” He feels it himself. “You can’t help but feel it. The difference is that I can identify it.” Other people, he suggests, are too caught up in their anthropomorphic notion that seals are almost human.

Recreational fishermen also generally manage to set aside any sentimental feelings, particularly because the contest with seals can seem so individual, so mano à mano. A surfcaster will pack up the car, drop the tire pressure down to 15 pounds for beach driving, wend his way out several miles to a favorite fishing spot, take his rod off the rack–and immediately a seal will pop up in the water directly in front of him. This business of floating upright and watching is called “bottling,” and sometimes 10 or 12 seals will show up and bottle together. Even if they can’t catch a striped bass or a bluefish on their own, they have become adept at stealing one off the end of a fisherman’s line.

If the fisherman moves down the beach, the seals often follow. Their great glossy eyes are widely separated, with the browline turned down anxiously at the outsides, making them look like Mr. Wimpy, or a dozen Mr. Wimpies, all meekly offering to pay the fisherman Tuesday for a striped bass today. Not so meekly, a seal will sometimes come hammering up out of the surf to snatch away a fish just as the fisherman is about to bag it.

“When people see the seal steal a fish off the line two or three times,

they don’t try a fourth time. They just stop,” says the proprietor of a local sporting goods shop. The seals form a “gray wall” in the surf, and schools of fish that used to run the beaches take the hint and move offshore. As a result, he says, the whole culture of spring and fall fishing on the beaches has gone away. Or rather, “it’s turned into rich man’s fishing. You have to buy a boat, or charter one.”

Out on Nantucket, where merely breathing can be a rich man’s sport, recreational fishermen have formed a Seal Abatement Coalition (SAC) to amend the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Peter Krogh, a courtly, high-browed figure in khaki slacks and a perfectly fitted tweed jacket, spent his career as a professor at Georgetown. He and a neighbor who is a former Citibank executive both retired to Nantucket for the beach fishing, only, as they see it, to have the seals take it away from them. “We sometimes wonder why we’re doing this,” says Krogh, about the SAC campaign. “We could just be playing golf. But if something isn’t done, the seals are going to overwhelm us and take over the island.” A lobbyist who has a house on Nantucket is pushing the cause for them on a pro bono basis in Washington, D.C.

This idea makes some other Nantucket residents seethe. “What gets me about SAC is the sense of entitlement,” says Blair Perkins, who grew up on the island and now runs Shearwater Excursions, a whale watching business. “They’re entitled to the fish and the seals aren’t. They’re recreational fishermen, and it’s interfering with their playtime. I don’t understand that at all.” The seals, he says, “need to haul out somewhere. They’re at sea sometimes for days or weeks at a time. They just want to survive as they have for thousands of years. To say that they’re interfering with my recreation is just arrogant.”

Beyond Butt Dialing: Blubber Dialing–Seals Part 4

The capture

One morning back in Chatham harbor, the fishermen watch out of the corners of their eyes as scientists and federal agencies get ready to head out on a seal research mission. It takes two hours of loading equipment, working out a plan, and explaining it to assembled reporters before the party even gets off the dock. It’s a flotilla of six little boats in a line and—to general snickering among the fishermen–they never even make it out of the harbor.

They don’t need to: There are plenty of seals to work with just 15 minutes from the dock. A little before 9 a.m., the two lead boats drop down a little below an exposed sandbar, where a hundred or so seals have hauled out. Then the boats turn and ease back up, on either side of the sandbar, with a tangle net bellying out in the water between them. As the seals scatter, other members of the team jump onto the sandbar and start hauling in the net. In short order, they have four seals ashore and start the careful business of untangling. “Nails free?” someone yells, and “I’ve got a flipper here!” Three seals quickly get released again, rejoining a vast herd now bottling nearby.

The fourth, a female, gets

The weigh-in.

shifted into a carrying net and transported by boat to a broader stretch of sand where, at 9:38, the scientists inject a sedative, weigh her in at 337 pounds, and gather around her in a sort of outpatient surgical scrum. At the head, someone extracts a tooth for aging, and at the tail someone else inserts what’s supposed to be a rectal thermometer but looks more like a colonoscopy tube as it threads endlessly inward. A guy with a computer rigged from a shoulder harness, like a beer tray at the ballpark, steps in to take a quick ultrasound image for blubber depth, then deftly steps aside to give other scientists room to take blood, skin, blubber, microbial swabs and other samples. “Got a whisker,” the guy at the head calls out. “Who needs a whisker? O.k., we’re up to 16 minutes.”

Transmitter in place

Someone is now mixing tubes of five-minute epoxy and slathering it onto the mesh fabric backing of a $5000 electronic device about the size of a point-and-shoot camera. Glued to the back of the seal’s skull, it will record her location, depth, ocean temperature, and other indicators for up to 9 months. Every time she comes ashore long enough to dry off, it will trigger the device to place a cellphone call and transfer the latest data, until finally the device drops off when she molts. The team will place similar devices on a total of nine seals over the next few days—and then analyze the data over the coming year. In a pilot test of the technology last year, a juvenile gray seal named Bronx swam 25,000 miles in the first five months, including a two-week trip out to the Georges Bank, with dives down 900 feet.

“So we can start to understand the ecology of these animals,” says Dave Johnston, a marine conservation biologist at Duke University. “Where do these animals go? How often do they travel? How many times a day do they dive and how deep? How does that overlap with ocean topography? How does it overlap with where people go?” A graduate student will work to see how seals interact with the fishing community. “Right now, we don’t know much and when people don’t know much, they’re worried and fearful. When there’s more information, we can move to understanding.”

“She’s starting to come up a little bit, guys,” one of the scientists calls out. A tag on the right and left flippers now identify her as seal 141. Someone calls out a checklist: “We got hair, we got skin, we got anal, we got whiskers.” Then everyone suddenly backs away as the waking seal lifts her baffled head. She studies the two-legged beasts all around her in puzzlement, then finally recovers enough at 10:40 to drag herself back to water and rejoin her herd.

Time to run

August 17, 2014

How it Feels When a Shark Attacks–Seals Part 5

Myers father and son, in repair.

So how will all this change Cape Cod? What will the coming of gray seals mean for the fishermen lying awake at night fretting about how to make the mortgage or pay for fuel? What will it mean for the 500,000 or so vacationers who dream of this place all winter and crowd themselves onto this spit of sand every summer to be revived for another year by nature? What will it mean for Chris Myers, who sometimes starts up out of his sleep at his home in Denver thinking about the seals and about that day in July 2012 when the shark attacked?

Myers and his 16-year-old son J.J. were swimming toward the breakers at a submerged sandbar 400 yards off Ballston Beach in Truro. He’d been swimming out to the sandbar all his life, to stand on it and throw himself forward with enough momentum to catch a wave for the long ride in.

This time, though, as they were still approaching the sandbar, something hit him, and he knew instantly that it was a shark. “The impact was incredibly shocking and painful.” It had him hard by the left leg. With his right leg he kicked furiously at its nose and mouth. “Like kicking a refrigerator. No give at all.” But then the shark let go, and after a moment it surfaced, the broad gray back three or four feet across, wheeling up in the tight little span between Myers and his son. Then the huge dorsal fin, slicing up and over. Not a movie. Real life.

Myers looked down to see if the shark had taken off his leg. “Then I realized that was a stupid thing to do,” and the two of them turned to swim toward shore, with J.J. screaming for help the whole way. Myers swam under his own power, or the power of adrenaline. He did not notice the pain again till his feet touched the beach. Then, unable to support his own weight, he crumpled onto the sand.

As people gathered around wide eyed, Myers looked down at his legs. “There was a lot of flesh and blood. I remember seeing fat and thinking, ‘Boy, these are deep cuts.’” He also felt “incredible relief. I was so elated that this had happened and that I had survived it.”

It took a few months to get back on a bicycle, and six months before he could run again. But how long before he could swim again at Ballston Beach. He was planning to head back to Cape Cod, as he has every summer for 48 years now. But it was clear that it will be a different Cape Cod for him next time.

The return of the gray seals means that it will be a different, more complicated Cape Cod even for Lisa Sette. She’s a field biologist with the Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown and looks the part, a sturdy, outdoorsy woman in her fifties, red faced, with a quick smile, in a t-shirt and a wool fishing cap. Sette likes to remind people that being bitten by a shark is even less likely than being hit by lightning. But over coffee with a fellow biologist one morning at the start of summer, she also swaps the sort of uneasy questions almost everyone on Cape Cod now sometimes asks: Is it safer to swim when there aren’t any seals around? Or is it safer with a large group of seals nearby, on the theory that sharks steer clear of crowds and tend instead to pick off loners? But having to think about those sorts of questions clearly doesn’t strike her as a bad thing.

Sometimes, lying in bed at night at her house a mile or so inland, Sette can hear the yawping and barking of the gray seals hauled out at Head of the Meadow beach in Truro. It’s a haunting sound, but also comforting for Sette, who regards the return of the seals as a restoration, not an invasion. Cape Cod has always been a special place, a little wild, a little reckless, an arm of the mainland flung 35 miles into the ocean, out among the whales and the dolphins—and now the gray seals. The sheer number of seals can seem overwhelming for people who are not used to them, she acknowledges. “When you cull a population and then stop, it will rebound,” she says, out at the beach one morning. “But everything finds its level. There are checks and balances.” Meanwhile, to witness the re-colonization in her own lifetime and to be able to walk up over these dunes and see the seals lying there, at home, is for her a kind of miracle.

Cape Cod, with all its traffic jams, and t-shirt shops, and vacation hordes, has somehow become a wilder, more natural place, a Cape Cod of predators and prey, where our own ability to make a living, or pursue a hobby, or swim in absolute safety are no longer quite so sacrosanct. It’s a Cape that can sometimes feel as if it has lost its footing and gone adrift in unknown currents.

But it may just be Cape Cod as it was always meant to be.

August 9, 2014

“Frankly, Darling, You Look Like Crap, Today”

(Photo: John Tiddy/Meetyourneighbours.net)

Say “Oh, my God, you look like shit!” and this spider is likely to answer, “Why, thank you!”

Add it to your list of species that evade potential predators by disguising themselves as bird poop.

It comes from Australia-based photographer John Tiddy , via American conservation biologist John Karges. Tiddy found this bird-dropping spider, Celaenia excavata, on a friend’s apple tree.

John says: “Being mid-winter here, there are not many leaves left on it. The spider hangs motionless during the day, relying on the bird poo look to protect it from predators. At night it descends on its web and emits a pheromone that mimics the pheromone given off by female moths. When the amorous male moth approaches, it becomes supper. Obviously a great spider to have around your fruit trees!”

August 8, 2014

Doing Dumb Things With Black Mambas

(Photo: Getty Images)

Last weekend, I left my rental car parked overnight in a remote location in northern South Africa, where I have been working on a story. When I got back to the car the following afternoon, there was a freshly shed snakeskin on the ground by the rear bumper. The biologist I was with (OK, he was a mammals guy) examined the head and ventured, “It could be a young black mamba.”

I contemplated that as I drove for the next four hours south to Pretoria. Off and on, I wondered whether the snake had sought shelter, as animals sometimes do, in the engine compartment of the car. In case you’ve somehow never heard of black mambas, they are among the deadliest snakes in the world and can grow to 15 feet in length. They generally use their considerable speed to escape rather than to attack, but they can also bite aggressively and repeatedly. Death may occur within as little as 20 minutes of the bite, which Africans refer to humorously as the “kiss of death.” I returned the car without opening the hood.

The scientists at the International Union for Conservation of Nature categorize the mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) as a species “of least concern.” But I don’t think that’s quite the right phrase. It’s not uncommon in the African bush to hear stories of black mambas turning up in the shower, or even dropping from the ceiling onto a bed. (“Hello, this is your wake-up call.”) I have a special place in my heart, or maybe it’s my amygdala, for these stories, and particularly for stories of people doing dumb things around these beautiful and generally harmless (but terrifying) creatures.

The topic came up again the other day, when I was visiting a safari lodge deep in the bush. The lodge manager told a story about a guest on her honeymoon who was terrified of insects. One night, the manager heard a horrible scream in the night and ran to the tent to find both husband and wife standing on tables, scantily clad, screaming, “Snake!”

The lodge manager, a slight woman born and raised in Europe, took a look, then pronounced it a spotted bush snake and harmless. (She looked twice, because spotted bush snakes look a lot like venomous boomslangs.) Then she picked it up in her hand and carried it gently out of the room, reassuring her guests. She was feeling quite proud of herself. It was in fact a spotted bush snake. No harm, no foul.

But it reminded her of another time when, over a period of weeks, she noticed that articles of clothing were spilling out of the cupboard in her room. “Who’s doing this?” she wondered. It wasn’t like when baboons broke into her room and randomly shredded her clothing, or like vervet monkeys stealing the toothpaste. Each time, she puzzled over it momentarily, but then went to bed without further thought. One night, though, she looked into the cupboard and saw something moving on the shelf. Her eyes adjusted to the darkness.

It was a snake. It occurred to her that it might be a black mamba. The only way she knew to identify one is that, while the skin is olive green, the inside of a mamba’s mouth is inky black. Then—and this is the stupid part, in case you’ve been waiting—the lodge manager picked up a broomstick and poked one end at the snake, which opened its mouth.

Black mamba.

It was, however, an unusually placid mamba and did not lash out at her.

The manager retreated, seeking someone better equipped to deal with the situation. When the mamba finally came out of the cupboard on the end of a snake stick, it was 1.5 meters long. That is, a mere five-footer. A puppy. Because it was an ecotourism lodge, the snake catcher and the manager proceeded to the second half of the catch-and-release process. Because they were human, they decided the release part would take place on the other side of the river.

Later, the lodge manger returned to her bed and tried to relax. But just as she was beginning to sleep, something moved on the bed by her feet. “I thought maybe it was the black mamba coming back for revenge,” she said. She peeked cautiously over the sheets. But it was just an Acacia tree rat,” she said, almost beaming.

“But a rat,” someone reminded her.

Yes, and she also gently evicted this other trespasser before going back to sleep. Then the lodge manager lifted her eyes and beamed again, as if to say that in black mamba country, and only there, a rat in your bed can be reasonably good news.

After that, we all went to the bar and had a stiff drink.

August 3, 2014

Insects Make the Perfect Food—for Cows

Global consumption of animal protein—milk, eggs, meat, and fish—is likely to rise 60 to 70 percent by mid-century. But producing food animals already eats up three-quarters of all agricultural land, and it threatens to empty the seas for fishmeal. Meanwhile, pig and poultry operations in particular have become notorious for polluting the surrounding countryside with manure.

Global consumption of animal protein—milk, eggs, meat, and fish—is likely to rise 60 to 70 percent by mid-century. But producing food animals already eats up three-quarters of all agricultural land, and it threatens to empty the seas for fishmeal. Meanwhile, pig and poultry operations in particular have become notorious for polluting the surrounding countryside with manure.

What’s the answer? Eating less meat can help, especially in meat-gorged nations like the United States, but it isn’t going to make these problems go away. Much of the increased demand will come from population growth and from greater wealth in protein-starved developing nations.

Instead, insects may be the answer. We’re not talking about direct consumption as human food, the perennial delight of horror-stricken journalists. The truth is that most people are never going to want to throw a housefly burger on the grill. But insects could just be the perfect feed for livestock.

A new article in the journal Animal Feed Science and Technology notes that insects breed literally like flies, they are highly efficient (because cold-blooded) at converting their feed into body mass, and, though it may need to be supplemented with calcium and other nutrients, that body mass is rich in the proteins and fats animals need. But the best part–questions of squeamishness aside—is that they can thrive on manure and other bio-wastes.

The article reviews the state of research on livestock use of locusts, grasshoppers, crickets, black soldier fly larvae, house fly maggots, mealworm, and silkworm meal. Each of them has is advantages and disadvantages in different habitats and species, but together they offer a battery of alternatives to conventional feed with soybean meal and fishmeal.

For instance, black soldier fly larvae—not to be confused with the blackflies that are a notorious summertime nuisance in some northern states—avoid human habitats and foods and carry no diseases. In fact, they can outcompete some other noxious insects, reducing housefly populations on pig and poultry manure by up to 100 percent. Meanwhile, they can reduce pig or poultry manure itself by 50 percent without requiring any energy input, at least in warmer climates. They can also reduce rotting fruits and vegetables, coffee bean pulp, distillers grains, fish offal, and other food wastes by up to 75 percent.Black soldier fly larvae are already commonly sold as pet food and fish bait. Studies suggest that pigs and poultry could do as well or better on a larvae-based feed as on conventional soybean and fishmeal feeds. The larvae could also be a practical alternative on fish farms, particularly where customers object to the ocean-emptying dependence on fishmeal. For some fish and for poultry, eating insects may also be a lot closer to their natural diets than conventional livestock feeds.

But is it safe to feed manure-reared larvae to animals that we eat—not just pigs and chickens but catfish, tilapia, turbot, and shrimp? Lead author Harinder Makkar of the Food and Agriculture Organization and his co-authors report that black soldier fly “larvae modify the microflora of manure, potentially reducing harmful bacteria such as Escherichia coli 0157:H7 and Salmonella enterica. It has been suggested that the larvae contain natural antibiotics.” More research will of course be needed. But the demand for animal products, together with the sharply increasing cost of conventional feeds, means that livestock producers are likely to be interested.

Meanwhile, consumers should prepare themselves to put their forks into rainbow trout fed on a diet in which half the normal fishmeal is replaced by “dried ground black soldier fly prepupae reared on dairy cattle manure enriched with 25 to 50% trout offal.”

It may make the world a better place. But it will require the marketing genius of some future Don Draper to make it sound appetizing.