Richard Conniff's Blog, page 47

May 2, 2014

Me, Spiderman, and the Life-Changing Bite

To mark today’s release of yet another tired version of the Spider-Man story, here’s a slightly different version of the story I published earlier this week. I wrote this version last year while cleaning out my Dad’s house after his death. It’s being published today, like Hollywood sequels, as if on auto-pilot, because I scheduled it back then and promptly forgot about it.

You remember that scene in the “Spiderman” comic where young Peter Parker gets bitten by a radioactive spider?

By way of reminder, here’s a panel from the original comic, published in the early 1960s. (Yes, cartoonists back then thought that spiders were insects.) This was the key event that turned mild little Parker into the celebrated web-swinger.

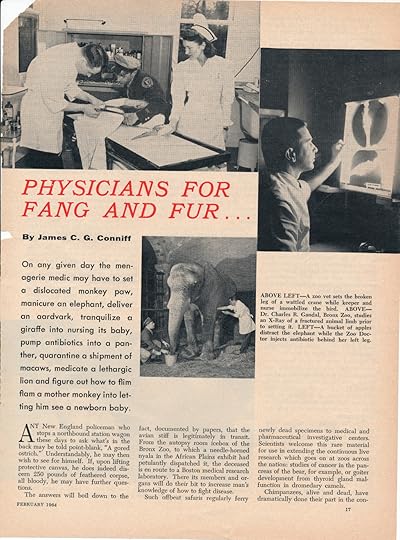

So when my father died recently, I began going through his father papers and I came across a story he wrote about zoo doctors. Late in 1963–50 years ago now–he took me to the Staten Island Zoo as part of his research, and there veterinarian Patricia O’Connor introduced me to to the year-old chimp in the picture below.

A photo of this scene appeared in the article “Physicians for Fang and Fur,” published in February 1964 in Columbia Magazine. It wasn’t my first appearance in a magazine. The Saturday Evening Post had published a poem he wrote about me as a “pink and precious” infant “tiny, elfin, fey.” But it was my first appearance as an identifiable person.

Anyway, immediately after this photo was taken that day at the State Island Zoo, the chimp bit me in the arm … and NOTHING WAS EVER THE SAME.

Patricia O’Connor, young culprit, unsuspecting victim at the Staten Island Zoo.

O.k., I didn’t exactly develop magical powers to swing through the trees or, chimpanzee-fashion, hurl shit at the heads of approaching strangers. But I became a writer about wildlife. Same thing, almost.

Until now, I had completely forgotten this episode. When interviewers asked me how I started writing about wildlife, I told them how an editor once asked me to write about New Jersey’s state bird, the salt marsh mosquito, and how I became fascinated with the incredible surgical tools in the mosquito’s proboscis.

Really, all I had to say was: Bitten, age 12, by radioactive chimpanzee.

For the record, here’s my dad’s story. He calls ungulates “cow- and deer-type animals,” and refers to several species as “monsters.” But I’m not complaining. It’s a step up from some of the other stories he was writing at about the same time, co-authored with J. Edgar Hoover.

May 1, 2014

Was Your Seafood Dinner Illegally Caught?

Check out my interview with Leonard Lopate, WNYC, on the illegal seafood being sold in your supermarket. It runs about 10 minutes. (But life is precious, so skip the first 37 seconds.)

The United States imports nearly 90 percent of its seafood, and according to a new study, nearly a third of imported seafood is caught illegally. Journalist Richard Conniff talks about illegal catches, mislabeled fish, seafood trafficking, and what is being done about the problem.

How To Survive in the Desert: Tell Clever Lies

Liar, Liar. (Photo: Tom P. Flower)

My latest for Takepart.

Once, in the southern African nation of Botswana, I watched a troop of baboons make their way blindly through an overgrown field. The tops of their heads barely cleared the tall grass, like the helmets of a military patrol walking into an ambush. They were oblivious of the presence of a cheetah cutting across at an angle to intersect them. I held my breath in anticipation. Then suddenly, a bird—a little spoilsport hornbill—put out an alarm call. Heads popped up, and the parties veered off in opposite directions.

The idea that animals listen in on the alarm calls of other species is not new. Birds, mammals, and lizards do it, and some species can even respond appropriately depending on whether another species is warning of an eagle or a snake. But a study out today in the journal Science takes this remarkable behavior a big leap forward, with an account of the astonishingly complex “tactical deception” practiced by the fork-tailed drongo.

Drongos are a common bird species across sub-Saharan Africa. They’re glossy black and about the size of an American robin. They have a reputation for being fearless and will readily run off raptors many times their size. “If they see an eagle, they zoom right up in the air at it like a surface-to-air missile and latch on to the tail,” says Tom P. Flower, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Cape Town, and lead author of the new study.

Drongos mainly prey on insects, often hawking them out of midair—for instance, around outdoor electric lights. But they are also kleptoparasites. That is, they steal food that other species have located or caught. It’s a common way of living in the natural world, and lions, hyenas, jackals, and of course vultures also do it—but none with the artfulness and audacity of the

fork-tailed drongo.

But who guards the guardians? (Photo: Tom P. Flower)

In the Kalahari Desert, a drongo will frequently travel in a mixed pack with southern pied babblers. They also associate with meerkats. These other species benefit, according to the study by Flower and his coauthors, because drongos produce honest warning signals at any hint of an approaching predator. So having a drongo perched high up on a bush nearby means the babblers and the meerkats down on the ground can spend less time being vigilant and more time feeding.

But their watchdog drongo also lies. Because he has a history of saving lives with his honest warnings, his false alarm calls also make the babblers and meerkats scatter—just long enough for the drongo to swoop in and steal their food.

You might think that this would only work for a little while. We all know from the legend of the boy who cried wolf that telling the same lie over and over just makes everyone ignore you, even if you mix it up with the occasional truth. So in addition to their own alarm calls, drongos have learned to mimic the alarm calls of no fewer than 45 other species. They borrow this spectacular repertoire mainly from other local birds and of course also from the babblers and meerkats.

Drongos are by no means the only successful vocal mimics in the animal world, nor even the only ones to use mimicry as a means of deception. Burrowing owls in the American West, for instance, imitate rattlesnakes to discourage potential predators from entering their nesting holes. But the drongos deploy their mimicry with an unparalleled degree of tactical variation. For instance, babblers predictably become just a little skeptical of drongo alarm calls, and they will resume foraging more quickly than they do after the alarm call of a different species. So the drongos produce mimicked calls 42 percent of the time, according to Flower. The babblers also get skeptical when they hear the same type of alarm call three times in a row. So when a drongo is making repeated food theft attempts on the same target, it uses a different alarm call three times out of four.

The remarkable thing is that the drongos go to all this trouble to get just 23 percent of their daily diet. But Flower points out that this is no small advantage in an environment as harsh and resource-poor as the Kalahari Desert, particularly in winter. It may seem as if the drongos have taken this game to such an inventive extreme at least partly for their own amusement. But the more likely reality is that becoming a clever thief is a matter of survival.

Infinity in the Palm of Your Hand

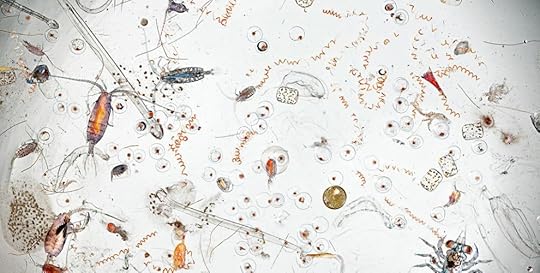

A drop of ocean water magnified 25 times. (Photo: David Liittschwager)

I just love the cartoon-like character of this photograph from David Liittschwager. (Check out his book, A World In One Cubic Meter.)

It’s the world in a single drop of ocean water, alive with crab larva, diatoms, bacteria, fish eggs, zooplankton, and worms.

It reminds me of the lines in William Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence”:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

And it also looks a bit like a Saul Steinberg drawing:

(Illustration: Saul Steinberg)

April 29, 2014

Five Ways Real Spiders Spin Webs Around Spider-Man

Wheel spider (Photo: hamariweb.com)

My latest for Takepart:

You remember that seminal scene in the “Spider-Man” story where young Peter Parker gets bitten by a radioactive spider? It is of course the event that turns mild little Parker into the celebrated web slinger. And in case you have somehow forgotten, despite endless repetitions in movies, television shows, video games, and theater, yet another version, The Amazing Spider-Man 2, will descend on unsuspecting moviegoers May 2.

It reminds me of a turning point in my own life, though I don’t normally identify much with superheroes. My father was a journalist, and one day when I was about 12, he took me along to New York City’s Staten Island Zoo. There veterinarian Patricia O’Connor introduced me to a year-old chimp, which reached out cordially, or so it seemed, to shake my hand. My father captured this endearing scene in a photo, which subsequently appeared with his article about zoo veterinarians under the headline “Physicians for Fang and Fur.”

It reminds me of a turning point in my own life, though I don’t normally identify much with superheroes. My father was a journalist, and one day when I was about 12, he took me along to New York City’s Staten Island Zoo. There veterinarian Patricia O’Connor introduced me to a year-old chimp, which reached out cordially, or so it seemed, to shake my hand. My father captured this endearing scene in a photo, which subsequently appeared with his article about zoo veterinarians under the headline “Physicians for Fang and Fur.”

Then, immediately after the photo was taken, the chimp leaned over and sank his teeth into my arm. And, need I say, NOTHING WAS EVER THE SAME.

OK, I didn’t develop a magical ability to swing through the trees or, chimpanzee fashion, hurl shit at the heads of approaching strangers. But I became a writer about wildlife. Same thing, almost.

As a result of that life-changing moment of infection, I have often tried to see the world from the point of view of the animals I am writing about. And at one point, for a National Geographic assignment about spider webs, I actually attempted to become a web slinger. I strapped on climbing gear and ropes, looking a bit like Charlotte’s Web meets Rambo. Then I set out to weave my web 15 feet above a concrete floor in the corner between two climbing walls at a YMCA. You can read the gory details in my book Swimming With Piranhas at Feeding Time: My Life Doing Dumb Stuff With Animals. But here’s the bottom line: Spiders have a magical ability to pull silk out of their butts. People don’t.

That assignment made me realize that all the bogus special effects in Spider-Man movies cannot come close to what real spiders do every day. With that in mind, here are five examples to make the latest Peter Parker weep:

1. While hanging from a trapeze line, a spider in Colombia uses its silk to make a sticky ball at the end of a thread. By mimicking the perfume of a female moth, it lures male moths into the area, where it beans them in midair with the ball, then reels them in for dinner. William Eberhard, the Universidad de Costa Rica biologist who discovered the species, recorded nine hits in 21 attempts. He named the species Mastophora dizzydeani, “in honor of one of the greatest baseball pitchers of all time, Jerome ‘Dizzy’ Dean.”

2. Europe’s water spider spends its whole life underwater, using its web to form a diving bell, which it anchors in place with a thread. The spider darts out to catch and eat anything that touches the web, mostly insect larvae and copepods. It also rises to the surface occasionally to trap air bubbles in its hair and carry them down to replenish the supply in its diving bell. For mating, the male builds a diving bell next to a female’s diving bell, then weaves a tunnel to connect the two.

3. In Mexico, a tiny web-building spider (Chrosiothes tonala) has adapted to feed on a highly unlikely prey: termites that nest underground. According to Eberhard, who first described the behavior, the spider waits on a horizontal line several inches above the ground, in an area where parties of worker and soldier termites are likely to come out onto the forest floor briefly in columns to forage. Apparently alerted by a chemical cue from the termites, the spider begins to drop to the ground as often as seven times a minute, searching for prey. Her descents are “blind,” and most are failures. If she is lucky, she lands on a column. But instead of attacking the first termite that she encounters, she attaches an anchor line to the ground and uses it to draw the horizontal line tighter and closer to the ground. Then she returns to the column of victims, biting one and tossing silk over its head like a hood. The first three or four victims pop up off the ground and hang in midair by a thread from the horizontal line. Later victims—up to 20 at a time—remain attached to the ground until the spider finally severs the anchor line and pops all of them into the air. Then, the spider casually rolls its prey in a ball and hauls off as much as 24 times her own weight in dead termites.

4. For a spider, the worst nightmare is to be attacked by a parasitic wasp. These wasps lay their eggs on the spider and inject venom that puts the spider in a coma. When wasp larvae emerge, they eat the spider alive. The peril is particularly intense for the wheel spider (Carparachne aureoflava) in southern Africa’s Namib Desert, because there’s no place to hide. So when it’s attacked, the wheel spider flips on its side and escapes by rolling down the dune at up to 44 rotations per second. (Check out the video.)

5. In Costa Rica (the remarkable Eberhard again), a spider makes a traditional orb web and then, by running a line back from the middle of the web to an anchor point, tightens it into the conical shape of a satellite dish. Some flying insects are clever enough to spot a web and back away at the last moment. But this spider simply cuts the anchor line, and the web springs forward to entangle the escaping victim.

What does all this add up to? I haven’t seen the latest Spider-Man movie, so maybe I’m just being cynical. But I’m betting that Hollywood moguls will turn out once again to have less inventiveness and artistry than your average house spider.

April 26, 2014

Idaho Steps Up Its Irrational War on Wolves

The sheriff claimed the shovel was for safety.

Something is loose in Idaho. Possibly a screw. The state’s ranchers and politicians, including the governor and the commissioner of Idaho Fish and Game, have somehow convinced themselves that they are at the mercy of roaming bands of savage sheep- and baby-snatching monsters, also known as wolves.

This notion has made Idaho anti-wolf activists so fearful and belligerent that they sound at times like New Jersey suburbanites in a gated community fretting about urban youth. Only more deadly.

Last month, Gov. C. L. “Butch” Otter signed a law creating a wolf control board with the explicit purpose of killing all but 150 of the state’s remaining 650 wolves. State officials would have preferred total extermination: “If every wolf in Idaho disappeared I wouldn’t have a problem with it,” the new fish and game commissioner declared at his confirmation hearing in January. But when the federal government, which reintroduced wolves to Idaho in 1995, agreed to turn over management of the wolf population to the state, it stipulated 150 as the rock-bottom number of wolves the state needed to maintain. Idaho has apparently chosen to honor the letter rather than the spirit of that agreement. One anti-wolf group spokesman has even proposed radio-collaring 150 wolves to ensure that the state does not fall below that minimum and “trigger the feds coming back in.”

The newly authorized slaughter follows the killing of more than 1,000 wolves in Idaho since 2009, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service first removed wolves from the endangered species list. This February alone, Idaho Fish and Game, together with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services, used helicopters to gun down 23 wolves. In December, it sent a hired gun to kill nine wolves in the federally protected Frank Church–River of No Return Wilderness Area. (The U.S. Forest Service, never a profile in political courage, pretended not to notice what was going on in an area Congress directed it to keep “untrammeled by man.”) Also that month, in the nearby town of Salmon, an Idaho hunting and gun rights group sponsored a wolf-killing derby.

“I’ve been doing wildlife work for a long time, and I’ve never seen anything like this,” said Jamie Rappoport Clark, a former director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and now president of Defenders of Wildlife. “There is a vendetta against wolves that is not only unseemly, it’s reckless,” and “bordering on a vigilante movement.” Instead of seeking to moderate it, political officials have been egging it on. “This is politics gone rogue, and in the gun sights are wolves, who don’t deserve it,” she said.

In one remarkable example of institutionalized lawlessness, Idaho County Sheriff Doug Giddings in 2011 sponsored what he called the “308 SSS Idaho County Sheriff’s Wolf Raffle.” He claimed that the abbreviation SSS stood for “Safety, Security, and Survival.” But in rancher parlance, “SSS” means “Shoot, Shovel, and Shut up”—that is, kill the wolves, bury the evidence, and never mind what the law says. To drive home the point, Giddings himself posed with a Winchester .308, a shovel, and a smile.

Since then, much of Idaho seems to have turned to shooting, shoveling, and shouting about it. The decision to abet this process with $400,000 a year in taxpayer funds comes in response to confirmed killings by Idaho wolves of 46 cattle and 413 sheep in 2013. Even taking top market rates of $900 for cattle and $150 for sheep, that adds up to just $103,350 in losses, for which the federal government now provides compensation funding. In the 25 years from 1987 to 2011, compensation paid to ranchers in Idaho for wolf losses totaled $1.4 million—less than the state now plans to spend in the first four years of its new killing program. So much for fiscal responsibility for Idaho Republicans like Gov. Otter.

The vendetta against wolves is particularly odd because wolves are vastly outnumbered in Idaho by other predators, including 30 grizzly bears, 3,000 mountain lions, 2,000 black bears, and 50,000 coyotes. The coyotes alone kill up to 10,000 sheep annually, said Suzanne Stone, a Boise resident and the wolf specialist at Defenders of Wildlife. That’s up to two dozen times as many as wolves kill. While ranchers with their .308s certainly fight back, their animosity toward these other predators doesn’t come anywhere close to the irrational hatred and spite they feel toward wolves.

Instead of exterminating wolves or paying compensation, Stone argued that it would be far cheaper to prevent killings in the first place. At the Wood River Valley Project, on 1,000 square miles of federal land in the Sawtooth Mountains, sheep grazers, government agencies, and Defenders of Wildlife collaborate to keep wolves away from livestock with non-lethal methods, including guarding dogs, sound devices, lighting, and flagging. One participant, Lava Lake Land and Livestock, boasts of “grazing a band of 1,000 sheep for a month in the immediate daily presence of a wolf pack with no losses of sheep or wolves.” Over six years, according to Stone, the program has lost just 30 sheep—about 1 percent of herds grazing there—without killing a single wolf.

Why not invest in that success? Or why not make wolves the basis for new jobs in the tourism economy, as has happened at Yellowstone National Park? Idaho’s political leadership, caught up in fairy-tale notions about wolves and a fanatic determination to oppose anything, even a native species, with the taint of the federal government on it, seems determined instead to drive this magnificent state down in a self-destructive cycle of hatred and killing.

For Idaho’s many wildlife-friendly residents, this may bring ruefully to mind a recent remark by comedian Stephen Colbert: “Idaho has just raised its speed limit to 80 miles an hour. Now you can get out of there even faster.” Instead, state residents should sign a Defenders of Wildlife petition demanding that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service begin an immediate status review of Idaho’s wolves. (So far, the nation’s premier wildlife management agency has been timidly looking in almost any other direction.) Then state residents should get to work electing a government that actually believes in their future.

April 23, 2014

A New Tool To Reverse Traumatic Memories

An Iraq war veteran with PTSD. (Photo: Lynn Johnson/National Geographic Society/Corbis)

My latest for Smithsonian magazine.

The best way to forget an alarming memory, oddly, is to remember it first. That’s why soldiers returning from war with post-traumatic stress disorder (or PTSD) often find themselves being asked by therapists to read scripts or view scenes recalling the incident that taught them the crippling fear in the first place.

Stirring up a memory makes it a little unstable, and for a window of perhaps three hours, it’s possible to modify it before it settles down again, or “reconsolidates,” in the brain. Getting patients to relive their traumatic memories over and over in safe conditions can thus help them unlearn the automatic feeling of alarm. It’s what researchers call “fear extinction” therapy—a way, almost, of reversing the past.

The trouble is that this therapy works with recent memories, but not so well with deeply entrenched long-term horrors. But a new study in mice, from the laboratory of neuroscientist Li-Huei Tsai at MIT, now promises to change that.

The scientists, who published their study in the journal Cell, taught lab mice fear by the standard technique of applying a mild electric shock, accompanied by a loud beep. Mice show fear by freezing in place, and they quickly learned to freeze simply on being put in the test box or hearing the beep. It was a “conditioned response,” like Ivan Pavlov ringing a bell to make dog’s salivate, in his pioneering experiments on learning and memory.

For the mice, fear extinction ear extinction therapy meant going back in the test box for a while, but without the shock. That was enough to unlearn the conditioned response if it was a new memory, just one day old. But if the mice had been trained 30 days earlier, the therapy didn’t work on what had by then become a long-term memory.

To change that, Tsai and lead author Johannes Gräffcombined extinction therapy with a type of drug that has recently shown promise as a way to improve thinking and memory in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other cognitive disorders. HDAC inhibitors (that is, histone deacetylase inhibitors) are compounds that alter the expression of genes. Injecting HDAC inhibitors seems temporarily to increase the ability of neurons, the basic working cells of the central nervous system, to form new connections. And those new connections are the basis of learning.

The HDAC inhibitors alone had no effect. But drugs fear extinction therapy together seemed to allow the therapy to open up and reconnect the neurons where long-term traumatic memory had until then been permanently locked away. The new learning was highly specific: Depending on how they tailored the therapy, the researchers could train the mice to ignore the entire conditioned response, or just a part—ignoring the beep, for instance, but still freezing on being put in the test box.

Getting from mice to humans is of course always a great leap, requiring extensive testing, for instance, to understand how HDAC inhibitors work: Do they modify the old memory? Or do they merely lay down a new memory trace on top of the old one, meaning the old one might spontaneously return? But the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has already approved investigative use of some HDAC inhibitors in treatment of certain cancers and inflammatory disorders. That could make it easier, Gräff speculates, to get to clinical testing in human psychiatric therapy in as little as five years.

Marie Monfils, who studies fear memory at the University of Texas at Austin, calls the new study “beautifully done,” with potential to “open up really interesting avenues for research and treatment.” That could be big news for a society alarmed by the surge in military suicides and other PTSD-related problems from more than a decade of war. For the desperate patients themselves, science now holds out hope that it will soon be possible, in effect, to rewind memory to a time before trauma stole their peace of mind.

April 22, 2014

Jamaica To Hand Over Heart of Its Largest Protected Area to Blacklisted Chinese Conglomerate

Tourism has long been the leading economic sector in Jamaica, bringing in half of all foreign revenue and supporting a quarter of all jobs. Yet government officials now risk jeopardizing that lucrative business, and Jamaica’s reputation in the international community, with a secretive deal to let a Chinese company build a mega-freighter seaport in the nation’s largest natural protected area.

The planned port would occupy the Goat Islands, in the heart of the Portland Bight Protected Area, which only last year the same government officials were petitioning UNESCO to designate a Global Biosphere Reserve. Instead, the lure of a $1.5 billion investment and a rumored 10,000 jobs has resulted in the deal with China Harbour Engineering Company, part of a conglomerate blacklisted by the World Bank under its Fraud and Corruption Sanctioning Policy.

Many details of the proposed project remain unknown, and the government has rebuffed repeated requests for information under Jamaica’s equivalent of the Freedom of Information Act. But the plan is believed to involve clear-cutting the mangrove forests on both Goat Islands, building up a level work area using dredge spoils from the surrounding waters, and constructing a coal-fired power plant to support the new infrastructure. The port, including areas currently designated as marine sanctuaries, would accommodate “post-Panamax”-size ships—up to 1,200 feet long and with a 50-foot draft—arriving via the newly expanded Panama Canal.

Landscape in the Hellshire Hills area (Photo: Robin Moore/Global Wildlife Conservation)

The new port would compromise an area known for extensive sea‐grass beds, coral reefs, wetlands, and Jamaica’s largest mangrove forests. The protected area is also home to the Jamaican iguana, a species believed extinct until its dramatic rediscovery in 1990. Since then, the international conservation community has spent millions of dollars rebuilding the iguana population in a protected forest in the Hellshire Hills, part of the reserve adjacent to the proposed port. Much of that investment hinged on the government’s promise, now apparently discarded, that the Goat Islands would become a permanent home for the iguanas, which are Jamaica’s largest vertebrate species.

“It sends a really poor message to the international conservation community—that an investment in Jamaica is not a good investment, that it can be wiped out in the blink of an eye,” said Byron Wilson, a herpetologist at the University of the West Indies. Wilson warned that a proposed causeway from the Goat

Youngsters from the head start program to rebuild population of Jamaican iguanas (Photo: Robin Moore/Global Wildlife Conservation)

Islands to the mainland, and the likely development of a community of workers, would consign the mainland iguana population to re-extinction. “Any place you put a lot of Chinese workers around the world, the wildlife suffers—it’s pretty clear.”

“Everything is for sale in Jamaica,” and not just the Goat Islands, added Rick Hudson, a herpetologist at the Fort Worth Zoo who has long collaborated on the iguana project. “They’re committed to developing every inch of the coastline for high-end hotels and resorts. There’s going to be no natural environment left.” Thus not much reason to visit Jamaica in the first place.

Jamaica’s existing port in Kingston Harbor could be expanded to handle the new traffic, Alfred Sangster, past president of Jamaica’s University of Technology, wrote earlier this week in the Jamaica Observer. The Chinese decision to reject that option “reflects a clear desire to have an enclave on the islands” where it can operate with fewer restrictions. He characterized the Chinese as the “new colonialists…in a country which has long memories of the legacies of colonialism.”

Diana McCaulay, CEO of the Jamaica Environment Trust, noted that the government has already relaxed work permit rules and created new categories of economic citizenship to accommodate the proposed project. On previous projects with Chinese contractors, she said, the majority of employees have been Chinese people. “And where they do employ Jamaican people, they don’t obey our work rules,” she said. She also worried that the secret terms of the deal may include tax or other incentives. “What is the benefit to Jamaica? That’s not clear.”

She added that China Harbour had insisted on building a coal-fired power plant, despite the inevitable contribution to climate change, because Jamaica’s electricity rates are too high. “Imagine that. We have to pay [the high rates], and they don’t.”

As one of the most indebted nations in the world, Jamaica is dependent on an International Monetary Fund financial package that stipulates paying down the nation’s debts. McCaulay attributed the deal to “desperation for what they call ‘development,’ but it’s more about winning an election in two years” for the government of Prime Minister Portia Simpson-Miller “than any benefit to Jamaica.”

“We live on a small island,” she added, “and it’s hard to believe anything universal is happening here. But it’s this whole idea that we should have more consumption. We already don’t know what to do with our wastes. We know we’re going to see sea level rise, and yet we just keep building more. We’re not stopping at all. And then you have players like China come in, who don’t care at all.”

Conservationists say the Jamaican government does not much concern itself over internal protests, but both Jamaica and China are concerned about international opinion. Jamaica’s economy depends largely on European and American tourists, and the U.S. consumer market is the ultimate destination for most ships that would be using the Goat Islands port. So signatures from outside Jamaica may carry weight on a petition asking Prime Minister Simpson-Miller to stop the proposed development.

Badger, Badger, Badger … Bat

Niumbaha superba (Photo: Bucknell University-DeeAnn Reeder)

This is a spectacular new bat from Sudan.

Here’s the story from Flora and Fauna International:

Researchers have identified a new genus of bat after discovering a rare specimen in South Sudan. With wildlife personnel under the South Sudanese Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism, Bucknell Associate Professor of Biology DeeAnn Reeder and Fauna & Flora International (FFI) Programme Officer Adrian Garside were leading a team conducting field research and pursuing conservation efforts when Reeder spotted the animal in Bangangai Game Reserve.

“My attention was immediately drawn to the bat’s strikingly beautiful and distinct pattern of spots and stripes. It was clearly a very extraordinary animal, one that I had never seen before,” recalled Reeder. “I knew the second I saw it that it was the find of a lifetime.”

After returning to the United States, Reeder determined the bat was

the same as one originally captured in nearby Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1939 and named Glauconycteris superba, but she and colleagues did not believe that it fit with other bats in the genus.

“After careful analysis, it is clear that it doesn’t belong in the genus that it’s in right now,” Reeder said. “Its cranial characters, its wing characters, its size, the ears — literally everything you look at doesn’t fit. It’s so unique that we need to create a new genus.”

Striped like a badger. (Photo: DeeAnn Reeder/Bucknell University)

In the paper, “A new genus for a rare African vespertilionid bat: insights from South Sudan” just published by the journal ZooKeys, Reeder, along with co-authors from the Smithsonian Institution and the Islamic University in Uganda, placed this bat into a new genus — Niumbaha. The word means “rare” or “unusual” in Zande, the language of the Azande people in Western Equatoria State, where the bat was captured. The bat is just the fifth specimen of its kind ever collected, and the first in South Sudan, which gained its independence in 2011.

“To me, this discovery is significant because it highlights the biological importance of South Sudan and hints that this new nation has many natural wonders yet to be discovered. South Sudan is a country with much to offer and much to protect,” said Matt Rice, FFI’s South Sudan country director.

FFI is using its extensive experience of working in conflict and post-conflict countries to assist the South Sudanese government as it re-establishes the country’s wildlife conservation sector and is also helping to rehabilitate selected protected areas through training and development of park staff and wildlife service personnel, road and infrastructure development, equipment provision, and supporting research work such as this.

The team’s research in South Sudan was made possible by a US$100,000 grant that Reeder received from the Woodtiger Fund. The private research foundation recently awarded Reeder another US$100,000 dollar grant to continue her research this May and to support FFI’s conservation programmes.

“Our discovery of this new genus of bat is an indicator of how diverse the area is and how much work remains,” Reeder added. “Understanding and conserving biodiversity is critical in many ways. Knowing what species are present in an area allows for better management. When species are lost, ecosystem-level changes ensue. I’m convinced this area is one in which we need to continue to work.”

The new genus has been described in Reeder DM, Helgen KM, Vodzak ME, Lunde DP, Ejotre I., 2013. A new genus for a rare African vespertilionid

bat: insights from South Sudan. ZooKeys, 285: 89–115. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.285.4892

How Your Supermarket Trafficks In Illegal Wildlife

My latest for Yale Environment 360:

When people talk about illegal trafficking in wildlife, the glistening merchandise laid out on crushed ice in the supermarket seafood counter — from salmon to king crab — probably isn’t the first thing that comes to mind. But 90 percent of U.S. seafood is imported, and according to a new study in the journal Marine Policy, as much as a third of that is caught illegally or without proper documentation.

The technical term is IUU fishing, for illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. But such improbable allies as Greenpeace and Republican members of the U.S. Senate now refer to it as “pirate fishing.” And it ensnares seafood companies, supermarkets, and consumers alike in a trade that is arguably as problematic as trafficking in elephant tusks, rhino horns, and tiger bones.

Among the egregious violations, according to the study: Up to 40 percent of tuna imported to the U.S. from Thailand is illegal or unreported, followed by up to 45 percent of pollock imports from China, and 70 percent of salmon imports. (Both species are likely to have been caught in Russian waters, but transshipped at sea and processed in China.) Wild-caught shrimp from Mexico, Indonesia, and Ecuador are also more likely to be illegal, and some illegal wild-caught shrimp may be disguised as farmed shrimp.

In recent months, government agencies and international maritime regulators have begun taking counter-measures to stop the illegal trade. Late last month, the European Union banned the importation of fish from Belize, Cambodia, and Guinea, alleging that those nations either sold flags of convenience — registrations having nothing to do with the location of the actual owners — or otherwise failed to cooperate in efforts to stop illegal fishing. The EU also issued “yellow card” warnings to Curaçao, Ghana, and South Korea.

The United States, which has lagged behind Europe on the illegal imports issue, also acted early this month, with the U.S. Senate approving four treaties aimed at

Crew of an illegal fishing vessel paint a new name on the hull in an effort to avoid enforcement for crimes committed under a prior name.

limiting illegal fish imports. The most important of them was the “port state measures” agreement, under which 11 coastal nations have committed to keep foreign vessels suspected of illegal fishing out of their ports. That treaty still requires approval by 14 other countries, meaning it will be several years before it takes effect.Finally, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in December approved a requirement that every fishing vessel of 100 tons or larger have an identifying number, like the vehicle identification number on a car. Freighters already have IMO numbers, which stay with them from the laying of the keel to the scrapyard. Extending that system to fishing vessels will make it harder to disguise an illegal catch by simply swapping a vessel around to different companies or different flags of convenience, says Tony Long, director of the Ending Illegal Fishing Project for the Pew Charitable Trusts. It will also close a loophole that has made it convenient to use fishing vessels in drug deals, gun running, and other criminal activities.

Long characterizes the permanent identifying number and the closing of ports to certain vessels as two of the three major steps needed to reduce the illegal trade. But the third step — creating a worldwide vessel monitoring system to track where and when vessels are fishing — will be more challenging.

Vessel monitoring systems (or VMS) already exist in some fisheries, says Long, but “global VMS would be a significant step forward.” Most ships already have Automated Information Systems, which give out critical data to nearby ships like name, course, and speed. But fishing vessels sometimes turn them off when working in illegal waters. Transshipping an illegal catch at sea to other vessels is also a common strategy, to disguise it as legal. A global system using satellites would make that sort of cheating harder to disguise.

“Now all the effort goes into chasing the bad guys,” says Long. “You spend 80 or 90 percent of your time trying to get the 10 or 20 percent who are misbehaving. We want a system where people who follow the legal standards, and haven’t transshipped at sea, can do business smoothly. It’s all about transparency.” On the other hand, if a non-complying vessel “comes in with its hold full of fish, and it gets turned away form port after port, it costs them money. It’s all about reversing the burden.”

The ultimate goal, says Long, “is to put in place a system where retailers can say what boat caught what fish and where. It’s impossible today, but it’s not impossible.” His group is now working on “traceability” with supermarket chains, including Metro Group, Whole Foods, Costco, and Trader Joe’s. He also hopes to enlist bankers and insurance companies in ensuring that the vessels they finance or insure are not engaged in pirate fishing.

In the absence of ocean-to-dinner plate accountability, the study in Marine Policy about pervasive illegality in the imported seafood market adds a new layer of confusion for seafood consumers. Numerous studies using DNA barcoding have already demonstrated that seafood being sold in the United States commonly does not come from the species on the label — with rockfish often substituted for red snapper, or mako shark for swordfish. Concern about the disappearance of cod and other once-common species has also recently led many consumers to tailor their purchases according to sustainability ratings, like the ones from the Marine Stewardship Council or the Monterey Bay Aquarium. But the Marine Policy study makes it apparent that fish varieties we thought were sustainably caught may in fact be contraband.

All this matters, of course, mainly because of the likely effect on the fisheries themselves. About 85 percent of all commercial fisheries are now being exploited up to or beyond their biological limits, according to Tony J. Pitcher, a fisheries researcher at the University of British Columbia and a co-author of the new study. Not being able to account for illegal fishing, much less stop it, makes it impossible to figure out what a sustainable legal catch should be. Beyond that, illegal fishing vessels tend to flout limitations on the type of gear, the fishing methods, or the locations where they work, often resulting in a major death toll for dolphins, turtles, sharks, and other bycatch.

For instance, small skiffs operating gill nets to catch shrimp off Mexico’s Baja Peninsula are, according to the new study, “the leading cause of death for the vaquita, a small porpoise endemic to the Gulf of California that is widely cited as the most endangered mammal in the world with a population of only around 200 individuals.”

The illegal trade can also have dire consequences for law-abiding fishermen. In 2012, for instance, the illegal harvest of king crab from Russia not only outweighed the entire catch from Alaska, but U.S. fishermen complained that it drove down their prices by 25 percent. So far in this century, that single Russian fishery has cost U.S. fishermen an estimated $560 million. Experts have put the global cost of illegal fishing at $10-$23.5 billion a year.

The heavy participation of informants in the new study in Marine Policy suggests that the fishing industry may be ready for increased transparency. “There were a surprising number of people within the industry who were uncomfortable about being involved in illegal trade,” says Pitcher. That’s partly out of concern for the future of fisheries.

“The retailers all have the same problem,” said lead author Pramod Ganapathiraju. “They say, ‘I’m getting 20,000 tons of snapper from Indonesia. I’m not sure what I’ll get five, or 10 or 20 years down the line because there are so many countries fishing there and so little control of illegal fishing. But I don’t have any alternative place to get those fish.’”

Ganapathiraju says consumers can play a major role by asking retailers to display the country of origin for the seafood they sell, and by inquiring about whether the retailer can document the legality of the catch. In the U.S., buying from domestic, or even local, suppliers is also helpful, since U.S. fisheries are managed more sustainably than in most other countries. “You know the vessel doing the catching, or it’s easily traceable. It’s more like a farmers market.”

Finally, he says, the U.S. government needs to increase its workforce for monitoring seafood imports at major ports. Seafood arriving by shipping container deserves special scrutiny, because dealers often use legal imports to disguise illegal ones in the same container. Importers and retailers will become more careful about the origin of the seafood they sell, says Ganapathiraju, as the likelihood increases that they will be caught and held liable for breaking the law, knowingly or otherwise.

In 2011, for instance, federal agents raided a leading seafood company in Seattle and seized 112 tons of king crab illegally harvested in Russia. Though it did not admit guilt, Harbor Seafood ultimately forfeited $2.75 million for its role in the transaction. In another case, the United States actually sent proprietors of a Georgia-based fishing business to jail in 2004 for illegally harvesting South African rock lobster over a 14-year-period. Last year, after a decade of appeals in that case, a U.S. judge for the first time ordered the payment of restitution to a foreign government. The culprits, who have fled the country, now face a $29 million payment to the government of South Africa.

That kind of enforcement could ultimately make the open seas seem far less open, and pirate fishing the modern-day equivalent of a hanging offense.