Richard Conniff's Blog, page 51

March 7, 2014

Carolina Chickadees Making Great Migration Northward

Are those black-capped (left) or Carolina chickadees (right) at the feeder (Illustration: http://www.sibleyguides.com)

No climate change here, boss. Those Carolina chickadees must just want to get re-named Connecticut Chickadees.

But their movement northward at seven-tenths of a mile a year could eventually get them re-named Canada chickadees instead.

Here’s the press release:

The zone of overlap between two popular, closely related backyard birds is moving northward at a rate that matches warming winter temperatures, according to a study by researchers from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Villanova University, and Cornell University. The research was published online in Current Biology on Thursday, March 6, 2014.

In a narrow strip that runs across the eastern U.S., Carolina Chickadees from the south meet and interbreed with Black-capped Chickadees from the north. The new study finds that this hybrid zone has moved northward at a rate of 0.7 mile per year over the last decade. That’s fast enough that the researchers had to add an extra study site partway through their project in order to keep up.

“A lot of the time climate change doesn’t really seem tangible,” said lead author Scott Taylor, a postdoctoral researcher at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “But here are these common little backyard birds we all grew up with, and we’re seeing them moving northward on relatively short time scales.”

In Pennsylvania, where the study was conducted, the hybrid zone is just 21 miles across on average. Hybrid chickadees have lower breeding success and survival than either of the pure species. This keeps the contact zone small and well defined, making it a convenient reference point for scientists aiming to track environmental changes.

“Hybridization is kind of a brick wall between these two species,” said Robert Curry, PhD, a professor of biology at Villanova University, who led the field component of the study. “Carolina Chickadees can’t blithely disperse north without running into black-caps and creating hybrids. That makes it possible to keep an eye on the hybrid zone and see exactly how the ranges are shifting.”

The researchers drew on field studies, genetic analyses, and crowdsourced bird sightings. First, detailed observations and banding data from sites arrayed across the hybrid zone provided a basic record of how quickly the zone moved. Next, genetic analyses revealed in unprecedented detail the degree to which hybrids shared the DNA of both parent species. And then crowdsourced data drawn from eBird, a citizen-science project run by the Cornell Lab, allowed the researchers to expand the scale of the study and match bird observations with winter temperatures.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 167 chickadees—83 collected in 2000–2002 and 84 in 2010–2012. Using next-generation genetic sequencing, they looked at more than 1,400 fragments of the birds’ genomes to see how much was Black-capped Chickadee DNA and how much was Carolina.

The site that had been in the middle of the hybrid zone at the start of the study was almost pure Carolina Chickadees by the end. The next site to the north, which Curry and his students had originally picked as a stronghold of Black-capped Chickadees, had become dominated by hybrids.

Female Carolina Chickadees seem to be leading the charge, Curry said. Field observations show that females move on average about 0.6 mile between where they’re born and where they settle down. That’s about twice as far as males and almost exactly as fast as the hybrid zone is moving.

As a final step, the researchers overlaid temperature records on a map of the overlap zone, drawn from eBird sightings of the two chickadee species. They found a very close match: the zone of overlap occurred only in areas where the average winter low temperature was between 14 and 20 degrees Fahrenheit. They also used eBird records to estimate where the overlap zone had been a decade earlier, and found the same relationship with temperature existed then, too. The only difference was that those temperatures had shifted to the north by about seven miles since 2000.

Chickadees—there are seven species in North America—are fixtures in most of the backyards of the continent. These tiny, fluffy birds with bold black-and-white faces are favorite year-round visitors to bird feeders, somehow surviving cold winters despite weighing less than half an ounce.

To the untrained eye the Carolina Chickadee of the southeastern U.S. is almost identical to the more northern Black-capped Chickadee—although the Carolina has a shorter tail, less white on its shoulders, and a song of four notes instead of two notes. Genetic research indicates the two have been distinct species for at least 2.5 million years.

“The rapidity with which these changes are happening is a big deal,” Taylor said. “If we can see it happening with chickadees, which are pretty mobile, we should think more closely about what’s happening to other species. Small mammals, insects, and definitely plants are probably feeling these same pressures—they’re just not as able to move in response.”

Journal Reference:

Scott A. Taylor, Thomas A. White, Wesley M. Hochachka, Valentina Ferretti, Robert L. Curry, Irby Lovette. Climate-Mediated Movement of an Avian Hybrid Zone. Current Biology, March 2014 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.069

March 6, 2014

Texas Gasses Its Rattlesnakes This Weekend–Maybe for the Last Time

(Photo: Greg Ward/Getty Images)

Members of the Texas State Parks and Wildlife Commission had a rare opportunity in January to commit an act of political courage. If they’d done it, hundreds of native Texans—and the creatures living around them—might have been spared a needlessly horrifying death this week.

A vote originally scheduled for the commission’s January meeting would have ended the practice of spraying gas fumes into cracks and crevices in the ground to drive rattlesnakes out of their dens. The groggy victims get tossed into bags and delivered to a rattlesnake roundup in Sweetwater, a town of 10,600 about three hours west of Fort Worth, which has made itself notorious with this practice. Because of the non-vote, the roundup will take place this Saturday and Sunday as usual.

The practice of gassing snakes, once common, is now regarded as barbaric even by the state’s other rattlesnake roundups. More than 9,000 people supported the proposed ban during the state’s yearlong round of research and public hearings. Apart from the question of cruelty, the argument against the practice is straightforward: Gasoline sprayed into the porous karst, or limestone, inevitably gets into groundwater, and that’s bad news, as the Houston Press reported, “for anyone or anything—especially out in West Texas—who, you know, likes to drink water.”

Gassing also threatens other karst wildlife. Studies have found “dramatic and obvious” effects, from “short-term impairment to death” in snakes, lizards, toads, and other vertebrates living in and around rattlesnake denning sites. The gassing also kills many karst invertebrates listed as endangered or threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, among them the Comal Springs riffle beetle, the Bone Cave harvestman, and the Government Canyon Bat Cave spider.

In the face of overwhelming support from around the state, the Parks and Wildlife Commission decided to delay the vote. “I view it as total cowardice,” one local conservationist remarked. The commissioners, who are unsalaried and serve at the pleasure of the governor, delayed the vote, the conservationist theorized, because “no one will do anything if it is going to upset anyone, anywhere,” or at least not anywhere in Texas.

The commissioners may have wanted to avoid controversy ahead of this week’s state legislative primaries. They may particularly have wanted to avoid raising a sensitive issue for Rep. Susan King, R-Abilene, who represents Sweetwater. King was the only person allowed to make a statement at the meeting at which the commission had been scheduled to vote on the gassing ban, and she delivered a rambling, disjointed, Sarah Palin–esque argument for doing nothing.

Among other things, King recalled her horror as a barefoot child seeing the grass move around her family home in Houston. “There was no wind. It was the toads,” she said, meaning Houston toads, now an endangered species. She said she was glad to see them gone (“I guess it was the pesticides, I don’t know”). Otherwise, she was all for coexisting with animals. She avoided the word “gassing” but said that “the fuming to encourage snakes to leave their habitat” has been going on for years. Any attempt to change that, she said, required complete transparency by regulatory agencies and scientific research in the field.

Awkwardly for King and her ilk, field studies dating back to 1970 have already demonstrated the destructive effects of snake gassing in Texas. On the question of transparency, King’s own track record includes a fail on “the political courage test,” a simple informational measure of candidates’ “willingness to provide citizens with their positions on key issues.” Even so, King won Tuesday’s primary with 67.5 percent of the vote (down from 100 percent in 2012).

That presumably clears the way for a vote on the gassing ban, now thought to be on the agenda for the commission’s May meeting in Austin. That will be the real “political courage test,” and there is reason to hope: The commissioners include S. Reed Morian, a member of the board of the Houston Natural History Museum; T. Dan Friedkin, a member of the advisory board of Texas A&M Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute; and Lee Marshall Bass, a billionaire supporter of the Peregrine Fund and the International Rhino Foundation.

For now, residents of West Texas have a choice of things to do this weekend. They can participate in the “world’s largest rattlesnake roundup,” starting Saturday at 9 a.m. in Sweetwater, where the idea of “fun for the entire family” will include seeing freshly decapitated snakes wriggle as the skin is ripped from their flesh. (You can also have them fried up for lunch.)

Or they can take their kids instead to the first annual Texas Rattlesnake Festival, four hours down the road in Round Rock, which aims to celebrate “the value of these amazing and beautiful animals and in which no snakes will be harmed or killed.”

It’s a good bet that Rep. King will be glad-handing the crowd at Sweetwater. You can count that as one more reason to head for Round Rock.

March 4, 2014

New Hope for Madagascar?

Diademed sifaka, found only in Madagascar, can leap 30 feet in a single bound (Photo: Cristina Mittermeier)

I recently posted here about signs of improvement in the political shambles that has passed for government in Madagascar over the past five years. My article was mainly about an emergency plan to save the island’s charismatic lemurs from extinction.

Conservation International’s Russ Mittermeier visited last month with the new president of Madagascar, Hery Rajaonarimampianina, and today he published this optimistic report.

Here’s an excerpt:

Rajaonarimampianina expressed his commitment to end the rosewood trade. He was also well aware of the importance of lemurs and other endemic species as major economic resources for the country, was very interested in ecotourism as a major potential foreign exchange earner, and clearly understood the value of Madagascar’s protected areas as essential sources of ecosystem services for human well-being. He also came across as a very clear strategist — a quality I have never seen before in Malagasy heads of state.

Several weeks ago, Rajaonarimampianina was the star at the meeting of African heads of state in Ethiopia. All of them professed their support of his administration (while also noting their dismay at having to learn how to pronounce his 19-letter name).

We in the international community need to provide as much support and positive feedback to the new president as possible. Donor agencies such as the critically important USAID have already begun discussions with him, and conservation organizations, beginning with CI, have already started to express our support. A recent article that several of us wrote for the journal Science on our 2013 Lemur Conservation Strategy also noted the importance of his new administration.

But things won’t be easy. The former president, Rajoelina, is still trying to exert control and place some of his people in the new government, and things could still go awry.

We need to make it clear to everyone in Madagascar that the world is on the president’s side, and that any efforts to reverse the results of a democratic election will not be well received. And those of us who are committed to Madagascar’s unique natural capital must ramp up our existing efforts. Then perhaps I can dust off my 2008 paper on the success story of Madagascar — and add a new chapter.

Read Mittermeier’s complete article here. And check out this selection of my past articles on this amazing nation.

Our Zoopolitan Future: Making Cities Safe for Wildlife

After a major cleanup effort, beavers have returned to the Bronx River. (Photo: Robert McGouey/Getty Images)

My latest column for Takepart, the website of the movie company Participant Media:

When conservationists worry about the prospect of a world without wildlife, they often focus on two related developments: the sprawling growth of crowded cities and suburbs, and the push to farm more land, and farm it more intensively, to feed those cities. Together, these two forces have worn the natural world down to tattered remnants.

So it may seem contradictory to suggest that cities can also be part of the solution. But conservationists, who used to focus on protecting landscapes that were pristine and full of wildlife, now often work instead to improve the margins—to make roadsides, backyards, idle fields, and working waterfronts wildlife-friendly. They argue that with a little effort, cities can provide habitat for birds, butterflies, pollinators, and other creatures great and small. According to this line of thinking, re-wilding the cities will be better not just for wildlife but for the cities. The idea is that the metropolis is a far richer place to live—more magical even—to the extent that it is also a zoopolis.

It’s a grassroots movement—or maybe, an anti-grassroots movement, with urban landowners planting habitat in place of lawns. But it’s official too. At its 2010 meeting in Nagoya, Japan, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity set targets to reduce the loss of habitat and to restore degraded natural areas. The plan includes a City Biodiversity Index, now being tested by 50 cities around the world as a tool for measuring and improving urban ecosystems.

So which cities are leading the movement to a zoopolitan future? What lessons are they learning that other cities can apply?

1. Over the past 30 years, Singapore has increased its natural cover—trees, parks, and green roofs—to almost half its land area, even while doubling its population to 5 million people. The original intent was commercial, because carefully maintained street trees and parks are signs to outside investors of a stable, prosperous community. That way of thinking is still evident, for instance, in the weirdly futuristic World’s Fair appeal of the 250-acre Gardens by the Bay project, a hugely popular park recently developed on reclaimed land.

But it’s not just self-interest: Singapore has also successfully reintroduced Oriental pied hornbills, and officials there have plans to boost populations of other species, including its critically endangered banded leaf monkey. Authorities have declared their intentions to make Singapore “a city in the garden,” and they seem to recognize that a garden is an empty stage if there are no birds or other creatures chattering in the trees.

2. In 2003, officials in Kampala, the capital of Uganda, wanted to drain the 1,300-acre Nakivubo Swamp and convert the land to industrial development and housing. Then a study pointed out that the wetlands provide essential treatment of sewage and other wastewater from the urban area. Over and above the cost of construction, operating a treatment plant to replace what the swamp was doing for free would have cost the city $2 million a year. The wetlands are now a protected area.

3. The 1.5 million Mexican free-tailed bats inhabiting the nooks and crannies of the Congress Avenue Bridge once seemed like a nuisance to planners in Austin, Texas. But a campaign by Bat Conservation International has turned the bats’ nightly emergence into a major attraction. Evenings in August, picnicking families assemble on grassy areas nearby, and tour boats jostle on the river below, waiting for the moment the bats take wing. The result is an ecotourism business worth an estimated $10 million a year. The city has taken the bats to its heart, and it now has a hockey team named the Austin Ice Bats. The Texas Highway Department, not otherwise known for progressive environmental thinking, has also recognized a good thing and is working to make other bridges in the state bat-friendly.

4. Sao Paulo is the third-largest city in the world, with 11 million people. Yet 21 percent of its land area is still covered with dense Atlantic rainforest including the Green Belt Biosphere Reserve. As a result, the city is home to cougars, capybaras, howler monkeys, and more than 430 other animal species.

5. Cape Town represents just two-tenths of a percent of South Africa’s total land area but it supports half of South Africa’s critically endangered vegetation types and 3000 plant species, many of them found nowhere else in the world. The city’s Strandfontein Sewage Works may not sound like such an appealing destination, but birders can spot a hundred species in a good morning there. The city is home to blue cranes, penguins, malachite kingfishers, and many other species. Nearby waters harbor a colony of Cape fur seals, with their attendant great white sharks.

6. My favorite case study is New York City’s Bronx River, for very personal reasons. My father grew up on the banks of the river in the 1920s, and the stories he told were all about going out on the water with his Italian immigrant grandfather to gather botanicals and to hunt. It was still a wild river then. In the magical stories my father passed down to his children and grandchildren, it was inhabited not just by a variety of wildlife, but also by a menagerie of imaginary creatures, led by a walking, talking green melon ball named The Growly.

For much of the rest of the twentieth-century, the Bronx River became a ruin of rusting bedsprings and junked cars, along with sewage and industrial pollution. But an extensive cleanup effort by the Bronx River Alliance and other groups has now restored the eight-mile-long lower river, with turtles, alewives, glass eels, great blue herons, and other species back at home there. Beavers returned in 2007—after an absence of several hundred years. City programs now focus on making the river a source of green pleasure for neighboring residents, many of them, like my great-grandfather, immigrants.

The restored river is providing habitat for wildlife—but it’s no doubt also producing new stories to entertain children, and to be passed down for generations into the future. And that makes the city a much richer and more magical place for everyone.

February 28, 2014

The Biological Warfare of Very Small Wasps

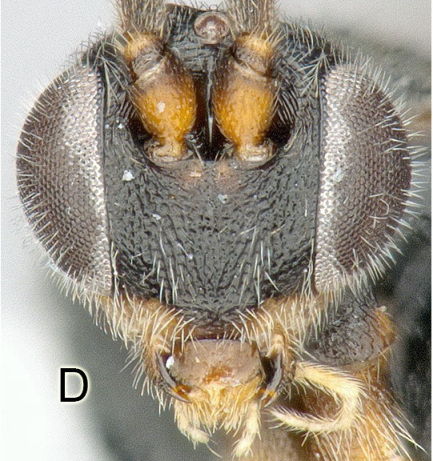

This is how a home invader looks like to a caterpillar (Photo: José L. Fernández-Triana)

My latest for Takepart, the website of the movie company Participant Media:

Earlier this year, a study came out describing a new plant species in the Andes that is the sole home of an estimated 40 or 50 kinds of insects. I thought that had a certain “wow” factor. It also seemed like a chance to write about “keystone species”—the ones on which whole ecosystems depend—and the ripple effects when such a species goes extinct.

So I asked for a comment from evolutionary ecologist Dan Janzen at the University of Pennsylvania, and he responded with characteristic pith and vinegar. “You tell me what species on the planet is not an important part of the life cycle of many tens to hundreds of other species,” he demanded. “As for so-called keystone species, that simply means a species whose removal or other kind of perturbation happens to create a set of ripples big enough for a two-meter-tall, diurnal, nearly deaf, nearly dumb, nearly odor-incompetent, nearly taste-incompetent, urban invasive species”—that would be us, Homo sapiens—“to see, or bother to see, the ripple.” I let that project slide.

But a new study out this week in the journal Zookeys gives me a better idea of what Janzen was getting at. It describes 186 new species in northwestern Costa Rica, all parasitic wasps, the largest of them about half the length of my pinkie nail, and most—at one to five millimeters—much smaller. They’re certainly too small for most people to notice and too obscure to care about—except perhaps that each is a deadly master of a macabre kind of biological warfare.

First, the background. For more than 30 years, ecologists and parataxonomists—the foot soldiers in the science of species discovery—have been methodically prowling the 1,200 square kilometers of Costa Rica’s Area de Conservación Guanacaste, picking caterpillars off vegetation. The caterpillars—500,000 of them so far—end up in individual plastic bags strung together on ropes, like Chinese lanterns, in rearing barns.

That may sound odd. But the idea—part of a long-term research project established by Janzen—is to see what emerges and thus how the Guanacaste ecosystem functions. Sometimes it’s a moth or butterfly, and the researchers have so far identified 10,000 species living in Guanacaste. But often what emerges instead are parasitic wasps, which have grown strong by eating the host caterpillar alive, from the inside out.

Caterpillar surrounded by cocoons of its parasites (Photo: Jose Fernandez Triana )

These parasites are the offspring of an adult female, who has diligently sought out a caterpillar of the right species and used her stinger to inject her victim with a virus. Each female wasp then lays her eggs on the body of her victim, says José Fernández-Triana, the lead author of the new study, and “the virus shuts down the immune system of the caterpillar to prevent it from encapsulating the eggs and killing them.”

When the wasp larvae emerge from the egg, they begin to eat the living caterpillar. In some cases, the virus will also manipulate the caterpillar’s behavior, so that when the time comes for the tiny wasp larvae to build their cocoons, the half-eaten caterpillar will actually protect them from ants or other predators.

“What we’re finding,” says Fernández-Triana, “is that 90 percent of the species of wasps are parasitizing either one species or a few species in the same genus. It’s chemical—no, biological—warfare. You’re injecting a virus that is only going to work on the one or two target caterpillar species.”

The new study represents only a fraction of the diversity at Guanacaste. It looks at just a single genus of wasps, Apanteles, which was known until recently from just three species in Costa Rica. The study brings the Apanteles total up to 205 species, including 19 described previously, as well as 186 new species.

Fernández-Triana and his coauthors combined three techniques to make their species identifications: DNA barcoding, using a small section of the mitochondrial genome, was accurate enough to detect a probable species difference 90 percent of the time. Details of body configuration, or morphology, were also essential, and Fernández-Triana had to make 49 body measurements on each of several hundred microscopic specimens. And ecological factors—particularly the kind of caterpillar species from which the wasp has emerged—helped triangulate the species diagnosis.

The study—one of many such studies out of Guanacaste—suggests the incredible diversity of species living on other species. It puts flesh on the 18th-century verse by Jonathan Swift: “So nat’ralists observe, a flea / Hath smaller fleas that on him prey; / And these have smaller fleas to bite ‘em. / And so proceeds Ad infinitum.”

But let’s get back to Janzen, a co-author of the new study, who fulminates, in Swiftian fashion, against human folly: We manage not to care, or we pretend not to notice, he says, that the “extinction, whether local or regional or total, of any species will impact the lives of a number of other species.” Humans have been doing that, he says, with “the attendant shrug of the shoulders,” since the Pleistocene. “We specialize in the elimination of species to make space (of all sorts) for us and our domesticates, and we are now busily polishing off the entire field to zero competition, with very few of ‘them’, leaving ourselves as the last competitor standing. Kind of obvious how that is going to end.”

On a less misanthropic note, the new study takes the unusual step of naming all of the new species after the parataxonomists, by first and last name, who did the grunt work of collecting and rearing them. The new names can be unwieldy—there’s an Apanteles guadaluperodriguezae and an A. hazelcambroneroae, for instance. But they serve as a reminder to the Guanacaste staff members of how much their own fate—and perhaps also ours—may be tied up in the lives of the obscure species they have discovered.

This Week’s Green News Roundup

Here’s the weekly news roundup from the Nature Conservancy’s Cool Green Science blog. (OK, it’s the second one I’ve posted this week, but that’s because I let last week’s get away from me. I apologize.)

The one near the bottom of this list, about Lady Gaga being bitten by a venomous mammal, reminds me of an old verse that arose from a geographic rivalry in the Turkish hinterlands: “A viper bit a Cappadocian’s hide/And poisoned by his blood, that instant died.”

I am hoping in this case that the biter, a slow loris, has survived:

Wildlife

Are elephants as smart and social as we like to think? (Strange Behaviors)

Get up close and personal with a water opossum and other wild critters of Nicaragua. (Mammal Watching)

Reasons to love wildebeest, as if you need an excuse. (Tetrapod Zoology)

New Research

Bears use wildlife road crossings to find mates. (LiveScience)

From the start-with-the-basics-file: USGS had to locate all the wind turbines in the US before studying their impacts. Results in downloadable report and GIS files. (USGS)

Try this at home. New tool (Global Forest Watch) allows web-based, near real-time tracking of deforestation. (ScienceInsider)

Climate Change

An ounce of prevention: The impacts of climate change on ocean ecosystems is immense, but there is hope for people who rely on fisheries if they institute sustainable practices now. (Nature Climate Change)

James Hansen launches program on Climate Science, Awareness, and Solutions at Columbia University. (ScienceInsider)

Caution! Silver bullets may ricochet. Analysis of five potential geo-engineering approaches to climate change mitigation shows minimal impact or adverse consequences under high CO2 scenarios. (Nature Communications)

Almost too good to be true: Study shows offshore wind turbines could mitigate hurricane damage and provide clean energy. (Nature Climate Change)

Nature News

The invasion has begun: Thousands of invasive quagga mussels confirmed in Lake Powell. (Salt Lake Tribune)

Maybe biocontrol can help Lake Powell: promising results using bacteria to control zebra and quagga mussels. (New York Times)

Large canals have a dark past. How would a canal across Nicaragua impact the environment and the people who live there? (Wired Science)

Conservation Tactics

If Indonesia can’t protect its orangutans, why doesn’t it just sell them to those who will? A provocative essay by former Cool Green Science contributor Erik Meijaard. (Mongabay)

Marine reserves: more — or better? Is practicing the art of the possible diluting the effect of marine protected areas? (Aquatic Conservation)

Plants engineered to produce moth pheromones provide an alternative to pesticides and artificial pheromones. (Phys.org)

Science Communications

The new openness of science publishing presents opportunities and challenges for those who write about scientific discovery, says Carl Zimmer at AAAS. (The Loom)

People don’t know what they don’t know, and the effect has a name: Dunning-Kruger. The good news: with a little negative feedback, we can learn. (Pacific Standard)

There’s communication to draw attention to an issue and there’s communication to develop relationships. They aren’t mutually exclusive, but they also aren’t the same thing. (The Science Unicorn)

Maximizing science impact through teamwork: Outcomes are better when scientists and communications experts work together. (SciDevNet)

This & That

Lady Gaga is bitten by a venomous primate, and sparks outrage over illegal loris trafficking in the process. (Mongabay)

Life hacks: PhD candidates know something about overcoming procrastination. (The Contemplative Mammoth)

- See more at: http://blog.nature.org/science/2014/02/28/elephants-and-water-opossums-and-wildebeests-oh-my/#sthash.su4XofKm.dpuf

February 27, 2014

Monarch Butterflies As Canaries in the Cornfield

This is a pretty comprehensive account of the monarch butterfly crisis, with lots of links to resource material. It’s from Lisa Feldkamp of The Nature Conservancy, and it appeared first on TNC’s Cool Green Science blog:

Everyone is talking about the record low count of monarchs at their overwintering site in Mexico, but what does the science say is happening to them and why does it matter?

Monarch butterflies have a special place in the North American imagination. They are beautiful, plentiful, and have a legendary predator-repelling capacity.

They are the state insect or butterfly of seven US states and an important ecotourism resource in Mexico, where millions of monarchs overwinter on oyamel fir trees.

With a range that covers the United States, watching monarchs was once a shared cultural experience, but that is changing fast.

No scientists are arguing that monarchs will go extinct, but numbers are dwindling at an alarming rate.

The most recent overwintering population in Mexico covered about 0.67 hectares of forest – a record low. That’s down approximately 44% from the 2012-2013 overwintering population, which was already very low (Rendon-Salinas 2014).

The record high was in 1996-1997, when the monarchs covered about 18.19 hectares of forest (Rendon-Salinas 2014).

Why are the numbers so low?

The short answer: Monarchs need two things, milkweed and very specific overwintering conditions. Both of these are at risk.

Overwintering and Oyamel Fir Trees

There are two large North American populations of monarch butterflies. The eastern population is the largest. These butterflies come from Canada and various US states, but they all (or very nearly all) gather in Mexico to overwinter, primarily in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve (MBBR).

Overwintering butterflies go into a state called diapause – it’s not exactly hibernation but they’re not fully active either.

During diapause they can preserve calories without eating, but they can’t easily fly and they require a stable temperature range to stay in this state.

If it gets too cold, these butterflies freeze, but if it gets too hot, they become active and have to search for nectar. The most devastating recorded freezing event in 2002 killed off 75% of the butterflies in the observed area and up to 90% estimated in other areas (Barve 2012, Brower 2004).

It turns out that dense forests of oyamel fir trees provide the most stable temperature for monarchs to overwinter.

Deforestation in the oyamel forests where monarchs overwinter can be a major threat to the species (Barve 2012, Brower 2012, Lopez-Garcia 2012, Vidal 2013).

Take out even a single tree and the monarchs near the open area are more likely to freeze (Brower 2011).

Increased protections and monitoring by the Mexican government and conservation organizations has all but stopped illegal logging in the MBBR (Vidal 2012), making deforestation less of a threat.

Unfortunately, the overwintering sites are still threatened by extreme weather events and climate change.

The places with the highest densities of butterflies now are predicted to have more extreme cold/wet events by 2050, making them unsuitable for the butterflies (Barve 2012, Brower 2012).

In addition, the trees that monarchs seem to favor and perhaps rely on when overwintering, the oyamel firs, are threatened by predicted warming trends in the region (Saenz-Romero 2012).

Starting from the prediction that there will be a 1.5C rise in temp by 2030 (a prediction questioned by Chip Taylor of Monarch Watch on Yale E360) a study by Saenz-Romero suggests that suitable habitat for these trees will quickly disappear in its current range until there is no suitable habitat left in 2090.

A surprising threat to monarchs from climate change has to do with the way that they navigate.

Monarchs’ decisions about which way to fly are affected by temperature. Exposure to colder than usual temperature in the fall causes monarchs that were headed south to turn around and fly north (Guerra 2013, Kyriacou 2013).

That’s right: if they hit colder temperatures, they might fly north for the winter!

It is also possible that if temperatures in their overwintering grounds were not cold enough, they would continue to fly south until they found a colder area (Guerra 2013, Kyriacou 2013).

Milkweed and Changes in Agriculture

Despite the improvements in protecting the MBBR, monarch numbers have continued to plummet.

This turned the attention of scientists to another phase of monarch life. In the spring and summer, monarchs of the eastern population spend their time in Canada and the United States, breeding and laying eggs on milkweed.

Monarch caterpillars are uniquely adapted to eating milkweed. It is likely that they need milkweed (any species of milkweed) to survive (Luna 2013).

Milkweed used to be abundant in the United States, especially in agricultural fields. That changed with the introduction of glyphosate-resistant crops. Milkweed all but disappeared from agricultural lands (Luna 2013, Pleasants 2013).

At the same time, because of increased demand for corn and soybeans in biofuels, more land has been planted with these glyphosate-resistant crops, leading to an estimated 58% decline in milkweed habitat in the Midwest (Pleasants 2013).

There is strong evidence to show that the Midwest is an important area for monarch production. Even though monarchs are typically only counted at their overwintering grounds in Mexico, stable isotope measurements can be used to tell where butterflies were hatched. The data accumulated thus far shows that most of them are from the Midwest (Flockhart 2013, Miller 2012, Pleasants 2013).

Furthermore, a study by Pleasants that estimated monarch production based on availability of milkweed (taking into account loss of agricultural habitat) revealed a positive correlation between estimated monarch production in the Midwest and the subsequent size of the overwintering population in Mexico (Pleasants 2013).

That is to say – as milkweed friendly habitat in the Midwest disappeared, the number of monarchs overwintering in Mexico dropped.

Going forward, climate change may also play a role in the suitability of monarch habitat in the US, but there are many variables that make it difficult to determine what effects it will have (Zipkin 2012).

See Richard Conniff’s excellent interview of Chip Taylor on Yale E360 for more detail on the impact of agricultural changes on butterflies.

Where are the butterflies going?

The drop in butterflies counted in the overwintering grounds is disturbing, but it does not necessarily match up to the drop in monarch butterfly numbers overall.

The butterflies could be going somewhere else.

As mentioned above, there are two major populations of monarchs in North America. They are called the eastern and western populations, but they are not genetically distinct, indicating that they continue to interbreed (Lyons 2012).

In recent years, the western population has grown.

Furthermore, some North American monarchs stay in Florida year-round or travel to the Caribbean (Flockhart 2013). In Mexico, there are some small clusters of butterflies farther east than the main overwintering population (Barve 2012).

It could be that as conditions in the MBBR have become increasingly unsuitable for overwintering, more monarchs have chosen these alternative locations.

Beyond the North American populations, there are also introduced populations of monarch butterflies in Hawaii, New Zealand, and Australia. These colonies have shown that monarch migration is highly adaptable.

Why is the overwintering phenomenon important?

Even if it is possible for butterflies to survive elsewhere, it is important to try to save the overwintering phenomenon.

Not only is it an amazing sight that we should want to preserve for its own sake and for future generations, it contributes to monarch health, to the economy, and to the preservation of pristine forests and biodiversity.

Lincoln Brower told Science Now that when butterflies stay in the same place for many generations, as they might if the overwintering phenomenon ends, they are more susceptible to the deadly Ophryocystis elektroscirrha parasite.

Ecotourism is a significant source of income for people living in and around the MBBR (Lopez-Garcia 2012, Lopez-Hoffman 2010, Vidal 2013).

Money from ecotourism is an important incentive for people to protect the forests. Without this many people in the area would have little choice but to turn to logging as a source of income (Vidal 2013).

In the United States, butterflies may be a “canary in the cornfield,” as Brower calls them in the aforementioned Science Now article. The loss of monarchs could be the first sign that the widespread planting of glyphosate-resistant crops is irrevocably disrupting food webs in the Midwest.

What can we do?

See Matt Miller’s previous Cool Green Science post for some of the most important ways that we can help keep monarch butterflies going.

Other things you can do to protect monarchs include:

* Carefully planned, controlled burning of milkweed patches can help make sure that have new growth at the times when monarchs are coming through and laying eggs (Baum 2012).

* Be careful what kind of milkweed you plant. Be sure that it is a species that grows locally. Karen Oberhauser warns Science Now that some tropical species grow year round, which encourages butterflies to stay in one place instead of migrating.

* Continue to protect the MBBR by tightening logging restrictions (Brower 2011, Navarrete 2011) and paying people there more for ecosystem services (Vidal 2013).

* Relocate oyamel firs to habitats that will be more suitable as the climate changes (Saenz-Romero).

Opinions expressed on Cool Green Science and in any corresponding comments are the personal opinions of the original authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Nature Conservancy.

References

Barve, N., A. J. Bonilla, J. Brandes, et al. 2012. Climate-change and mass mortality events in overwintering monarch butterflies. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad. 83: 817-824.

Baum, K. A. and W. V. Sharber. 2012. Fire creates host plant patches for monarch butterflies. Biology Letters. 8: 968-971.

Brower, L. P., D. R. Kust, E. Rendon-Salinas, et al. 2004. Catastrophic winter storm mortality of monarch butterflies in Mexico during January 2002. Pp. 151-166. In The Monarch Butterfly: Biology and Conservation. K. S. Oberhauser and M. J. Solensky (eds). Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

Brower, L. P., E. H. Williams, L. S. Fink, et al. 2011. Overwintering clusters of the monarch butterfly coincide with the least hazardous vertical temperatures in the oyamel forest. Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society. 65:27-46.

Brower, L. P., O. R. Taylor, E. H. Williams, et al. 2012. Decline of monarch butterflies overwintering in Mexico: is the migratory phenomenon at risk? Insect Conservation and Diversity. 5: 95-100.

Brower, L. P., O. R. Taylor, and E. H. Williams. 2012. Response to Davis: choosing relevant evidence to assess monarch population trends. Insect Conservation and Diversity. 5: 327-329.

Davis, A. K. 2012. Are migratory monarchs really declining in eastern North America? Examining evidence from two fall census programs. Insect Conservation and Diversity. 5: 101-105.

Diffendorfer, J. E., J. B. Loomis, L. Ries, et al. In Press. National valuation of monarch butterflies indicates an untapped potential for incentive-based conservation. Conservation Letters. DOI: 10.1111/conl.12065

Flockhart, D. T. T., L. I. Wassenaar, T. G. Martin, et al. 2013. Tracking multi-generational colonization of the breeding grounds by monarch butterflies in eastern North America. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 280: 20131087.

Guerra, P. A. and S. M. Reppert. 2013. Coldness triggers northward flight in remigrant monarch butterflies. Current Biology. 23:419-423.

Kyriacou, C. P. 2013. Animal behavior: monarchs catch a cold. Current Biology. 23:R235-R236.

Lopez-Garcia, J. and I. Alcantara-Ayala. 2012. Land-use change and hillslope instability in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, Central Mexico. Land Degradation & Development. 23:384-397.

Lopez-Hoffman, L., R.G. Varady, K. W. Flessa, et al. 2010. Ecosystem services across borders: a framework for transboundary conservation policy. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 8:84-91.

Luna, T. and R. K. Dumroese. 2013. Monarchs (Danaus plexippus) and milkweeds (Asclepias species): the current situation and methods for propagating milkweeds. Native Plants. 14:5-15.

Lyons, J. I., A. A. Pierce, S. M. Barribeau, et al. 2012. Lack of genetic differentiation between monarch butterflies with divergent migration destinations. Molecular Ecology. 21:3433-3444.

Miller, N. G., L. I. Wassenaar, K. A. Hobson, et al. 2012. Migratory connectivity of the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus): patterns of spring re-colonization in eastern North America. PLoS ONE. 7:e31891.

Navarrete, J-L., M. I. Ramirez, and D. R. Perez-Salicrup. 2011. Logging within protected areas: spatial evaluation of the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. Forest Ecology and Management. 262:646-654.

Pleasants, J. M. and K. S. Oberhauser. 2013. Milkweed loss in agricultural fields because of herbicide use: effect on the monarch butterfly population. Insect Conservation and Diversity. 6:135-144.

Rendon-Salinas, E. and G. Tavera-Alonso. Forest surface occupied by monarch butterfly hibernation colonies in December 2013. WWF-Mexico. 4 p.

Saenz-Romero, C., G. E. Rehfeldt, P. Duval, et al. 2012. Abies religiosa habitat prediction in climatic change scenarios and implications for monarch butterfly conservation in Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management. 275:98-106.

Vidal, O., J. Lopez-Garcia, and E. Rendon-Salinas. 2013. Trends in deforestation and forest degradation after a decade of monitoring in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in Mexico. Conservation Biology. 28:177-86.

Zipkin, E. F., L. Ries, R. Reeves, et al. 2012. Tracking climate impacts on the migratory monarch butterfly. Global Change Biology. 18:3039-3049.

- See more at: http://blog.nature.org/science/2014/02/26/cornfield-monarch-butterfly-decline-pollinators-agriculture/#sthash.EO7V79lp.dpuf

February 25, 2014

The First Great Ocean Voyagers? Hint: It Wasn’t the Polynesians

My latest for Takepart, the web site of movie company Participant Media:

My latest for Takepart, the web site of movie company Participant Media:

An old theory held that one of the earliest domesticated crops—bottle gourds, widely used for drinking vessels, food storage containers, musical instruments, and even medicine—came to the New World from Asia, either drifting across the Pacific or being carried by humans via the Bering Land Bridge. But new evidence argues that gourds made the ocean voyage on their own, not from Asia but from the coast of West Africa.

The new study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is interesting partly for what it says about the hazards of putting too much faith in narrow genetic analysis. It also fits into a much larger scientific movement arguing that plants and animals—including amphibians, monkeys, and perhaps even flightless birds—didn’t need continental drift, land bridges, or human migrations to reach their current locations. They did it, instead, more or less on their own, through a series of chance long-distance ocean voyages.

For the study, Logan Kistler of Pennsylvania State University and his coauthors looked at 36 modern samples of bottle gourds and nine ancient ones from archaeological sites around the Americas. Their results contradict a 2005 study—published in the same journal and including one of the same coauthors—that tracked the original gourds back to Asia.

Why the difference? The earlier study examined only three narrow sites on the gourd genome. Studying a larger sample of the genome revealed that “Africa is the clear source region of the bottle gourds that populated the Americas,” the study concludes, adding that the results “highlight the risk of basing conclusions on very small genetic datasets.”

Using computer models of prevailing currents, Kistler and his coauthors also calculated that sea-going gourds could have hitchhiked from West Africa to Brazil in as little as 100 days, though the average crossing would have lasted nine months. Either number fits existing evidence that bottle gourd seeds can remain viable after almost a year afloat in seawater.

According to Kistler, the first bottle gourds in the New World show up in the archaeological record about 10,000 years ago, in Florida and Mexico. Their seeds have also turned up in mastodon dung at a site in northern Florida, suggesting the critical role of now-extinct large mammals in spreading gourds around the New World.

The work on gourds fits a shift among evolutionary thinkers away from the old idea that plants and animals arrived at their present locations as passengers, carried along in comfort as shifting tectonic plates pushed continent-size land masses across the face of the planet. That idea became conventional wisdom in the 1960s and 1970s, when the scientific community finally accepted the theory of continental drift. But science is constantly overturning its own orthodoxies, and the development of increasingly precise molecular clocks—timelines based on changes in DNA—has forced scientists to seek other explanations for long-distance migrations.

For instance, monkeys also originally came to South America from Africa. But we now know it couldn’t have happened when the two continents pulled apart 100 million years ago. Molecular clock studies say Old and New World monkeys diverged from a common ancestor less than 50 million years ago, and monkeys don’t even show up in the New World fossil record until 26 million years ago.

In his new book The Monkey’s Voyage: How Improbable Voyages Shaped the History of Life, evolutionary biologist Alan de Queiroz makes the case for an alternative explanation: Even now, large land rafts periodically calve off from river banks and drift out to sea. A few hapless monkeys and other species trapped aboard could have been carried along on favorable currents—and 40 million years ago, the Atlantic Ocean may have been just 900 miles across at its narrowest point. With the most favorable winds, the voyage for the first pioneering monkeys in the New World could have taken as little as a week.

Other studies suggest that lizards and amphibians can also sometimes survive long-distance voyages. As recently as 1995, for instance, a hurricane carried green iguanas from Guadeloupe 175 miles across the Caribbean to Anguilla, which they promptly colonized. Even the massive flightless birds known as moas, now extinct, may once have been ocean travelers. The idea that their ancestors may have flown to New Zealand recently became more plausible when the tinamou, a large-bodied South American bird that can fly, turned out to be a member, along with the moa, in the otherwise flightless ratite evolutionary group.

All this suggests several useful conclusions: Science is an endless search for the truth but always subject to modification as better facts come along. Improbable chance plays a greater role in the history of life than we generally like to admit. Species of all kinds—but especially those first pioneering monkeys staring out desperately across an endless blue horizon—are far more enduring and heroic than we can even imagine.

February 21, 2014

The Weekly Green News Roundup (Giant Rodents Rule)

Here’s the weekly news roundup from the Nature Conservancy’s Cool Green Science blog:

Wildlife

Winter warrior: why the ptarmigan may be the best-adapted bird when it comes to thriving in snow. (Audubon)

Not-so-mighty-mouse: the unfortunate politics, hyperbole and myth surrounding the endangered Preble’s meadow jumping mouse. (High Country News)

Why are males and females different? How the climate 27 million years ago shaped sexual dimorphism in pinnipeds. (Science Daily)

New Research

Planet of the Rodents: Researchers predict giant rats will rule the earth when other species go extinct. (Focusing on Wildlife)

Ants join forces to float queen (and brood) to safety. Surprisingly, the young go on the bottom — not because they are more expendable, but because they are more buoyant. (PLoS ONE)

Doing conservation across geographic and political boundaries presents special challenges. A new survey zeroes in on effective approaches. (Conservation Biology)

More bad news for pollinators: The crazy diseases that are killing off honeybees are hitting bumblebees, too. (Nature)

Climate Change

Might corals swap skeleton material? Some corals may have another option as calcite skeletons succumb to ocean acidification. (Nature Communications)

High water reveals floodplain vulnerabilities. Findings inform planning to mitigate damage from climate change driven flooding. (Environmental Science and Technology)

Yes, the Atlantic current CAN shut down and turn the UK into a frozen wasteland — because it’s happened before. (Science; subscription required)

Nature News

New whistleblower site — Wildleaks — launched to report wildlife and forest crimes. (Mongabay)

Have you had your “Nature Daily Allowance“? (Conservation Magazine)

Conservation Tactics

Eat the invaders: company plans to harvest and market berries from non-native autumn olives. Their supermarket name? Lycoberries. (Invasivore)

A new use for pesky duckweed: genome suggests great potential for biofuel. (Eurekalert!)

Time-lapse video shows American chestnut with blight-resistant genes fighting off disease. (SUNY College of Environmental Science & Forestry)

When conservation focuses on human needs, is it saying “yes” to extinctions? Richard Conniff examines the debate — and Peter Kareiva responds to Conniff’s satisfaction. (Strange Behaviors)

Science Communications

Imminent ruling in FOIA suit for climate scientist Michael Mann’s e-mails unites strange bedfellows. (Yale Forum on Climate Change and the Media)

Why don’t scientists advocate more for pure-science funding? This graph might have the answer. (Roger Pielke Jr.’s Blog)

Another nail in the science-writer coffin: The Washington Post is now running press releases on science in its Health & Science section. (Journalism at MIT Tracker)

This & That

Stranger than a Carl Hiaasen novel: State of Florida joins lawsuit to fight cleanup of Chesapeake Bay. (And you are correct; the Chesapeake Bay is nowhere near Florida). (Miami Herald)

You’ve heard of rooftop gardens, but what about rooftop “meat”? In Thailand urban farmers are growing an edible cyanobacteria meat alternative (SciDevNet)

The next big thing in ecology? Soundscape analysis. (Science; subscription required)

- See more at: http://blog.nature.org/science/2014/02/21/adaptable-ptarmigan-duckweed-biofuel-chestnut-fights-back/#sthash.GgSxn4YY.dpuf

February 20, 2014

Democracy Offers A Last Chance for Lemurs

Sahamalaza’s blue-eyed black lemur (Eulemur flavifrons) in northwest Madagascar. (Photo: Nora Schwitzer)

My latest column for Takepart, the web site of movie company Participant Pictures:

Sahamalaza National Park in northwestern Madagascar is home to the strikingly beautiful blue-eyed black lemur—or to paraphrase its French name, “the lemur with the turquoise eyes.”

It’s a small, tree-dwelling creature, weighing less than four pounds, with a luxuriant tail that can be half as long as its body. It’s svelte and striking enough to appear on the cover of Vogue, and exotic enough for a music video with Lady Gaga. Yet this lemur remains almost unknown to the outside world. As a result, it is not just critically endangered, but one of the 25 most endangered primates in the world. With luck, a few thousand individuals may survive in the wild, almost all of them in three or four patches of forest in Sahamalaza National Park.

What’s happening to the blue-eyed black lemur is typical of the plight of the entire family of lemurs, 101 of the most colorful animals on the planet. According to a new study published today in Science, 94 percent of all lemur species are now threatened, and many of them are endangered or critically endangered. Their chances of survival have fallen dramatically in the five years of political and economic chaos in Madagascar since a 2009 coup installed a government widely regarded by the outside world as illegitimate.

In the immediate aftermath of that coup, thousands of illegal loggers swarmed into national parks and other protected areas, hacking down precious rosewood, palisander, and ebony trees, almost all of it for export to furniture makers in China. (See an undercover video by the Environmental Investigation Agency here. It features a $1 million canopy bed made from Madagascar rosewood and allegations of bribery at the highest levels of the Malagasy government.) Bushmeat hunting for lemurs, previously rare in Madagascar, became widespread, as the economy dropped out from under people who were already getting by on less than $2 a day.

But the new article, penned by 19 scientists in the primate specialist group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, also finds cause for hope. It proposes a $7.6 million emergency three-year plan to protect lemurs at 30 sites around Madagascar, a Texas-size island off the southeastern coast of Africa.

Like a lot of plans, it could just gather dust on a shelf. But Madagascar last month inaugurated a new democratically elected president, Hery Rajaonarimampianina. Outside observers were originally uneasy because he’d served as finance minister in the previous administration. But Rajaonarimampianina, a former accountant educated at the University of Quebec, appears to be steering his new government in a more positive direction, according to Russ Mittermeier, a co-author of the new article and president of Conservation International.

Mittermeier met at length with Rajaonarimampianina last week to discuss the emergency plan for lemurs and also to emphasize the economic significance of lemurs as “Madagascar’s salient brand” for tourism, still a mainstay of the economy. (About 250,000 tourists visit annually, down from 350,000 before the coup.) If this optimistic assessment proves accurate—and much still hangs on Rajaonarimampianina’s choice for prime minister—international aid organizations could soon release tens of millions of dollars in conservation funding on hold since the 2009 coup.

The emergency lemur plan calls for four key elements at each of the 30 proposed sites, according to Mittermeier, who chairs the IUCN primate specialist group: A park director or protected area manager “who is not corrupt;” a permanent, full-time research presence “because researchers are your best protection;” ecotourism facilities, because outside eyes also help; and the combination of a local guide association and a community conservancy program so the local people have a stake in protecting the land.

“Madagascar seems to have a political crisis every 10 years, almost on schedule,” says co-author Christoph Schwitzer, of the Bristol (UK) Zoo. “We need mechanisms that can help protect the biodiversity of the country in the absence of political institutions.”

But nothing comes easy in Madagascar, which remains one of the poorest nations on Earth. Just traveling the few hundred miles to Sahamalaza National Park from the capital city of Antananarivo takes him three days, says Schwitzer, who runs a research program in the park that’s funded by 30 European zoos. You can get there much faster by plane and speedboat via Nosy Be, Madagascar’s largest tourist resort, but it’s expensive.

The eventual ambition for Sahamalaza, says Schwitzer, is to piggyback on Nosy Be, so people who go there for the beach or to dive on the coral reefs, could also easily take a side-trip to see the blue-eyed black lemurs (and a half-dozen other lemur species). Over the past few years, Schwitzer’s group has established Sahamalaza National Park’s first tourist camp, with two solar-powered showers (arranged with considerable effort), walking trails, and a group of trained guides.

That’s the sort of effort that the new emergency plan envisions at each of the 30 sites, if it can raise the $7.6 million.

To put that amount in perspective, Dreamworks Animation has released three Madagascar animated movies since 2005 that capitalize on the charismatic appeal of lemurs. These films have so far earned about $1.9 billion worldwide. But almost none of that money has come back to Madagascar itself, and the lemur community doesn’t expect that to change any time soon.

Instead, Schwitzer says ordinary people interested in helping lemurs should donate their $5 or $25 to the organizations working at the 30 sites included in the plan. Among them: Conservation International, the Wildlife Conservation Society, the Duke Lemur Center, and the Institute for the Conservation of Tropical Environments at Stony Brook University.

In a sad but related note, news came out this week about the death from cancer of Alison Jolly. She was the pioneering primatologist who first described the importance of social networking and also discovered female dominance in ring-tailed lemurs. Then she persuaded the government of Madagascar to set aside land to protect lemurs. Her legacy of fellow primate species saved from extinction is one in which the rest of us now have the opportunity to share.