Richard Conniff's Blog, page 55

February 1, 2014

Getting Ranchers to Tolerate Wolves–Before It’s Too Late

(Photo: Ken Canning / Getty Images)

My latest for Takepart:

Ever since the 1995 reintroduction of the gray wolf to Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho, ranchers in the region have loudly complained that their herds end up paying a heavy cost. Lately, as a result, they’ve taken to trapping and shooting wolves at every opportunity.

Hunters have already exterminated more than a third of the 1,600 wolves that were thought to live in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho in 2012, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service ended endangered species protection for gray wolves there. Environmentalists now worry about the danger of a new regional extinction. Ranchers and some state wildlife officials meanwhile seem to be ardently working to achieve it.

The wolves are no longer safe even within a protected federal wilderness: Just last week, facing a lawsuit by environmental groups, the State of Idaho recalled a hunter it had sent into the Frank Church-River of No Return National Wilderness Area to kill wolves there. Environmentalists claimed a small victory. But state officials said the hunter had already killed nine wolves and presumably eliminated the two wolf packs thought to inhabit the wilderness.

In this combative context, a new study in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics reports the disturbing conclusion that the ranchers are right about at least one thing: The cost.

Together with his co-authors, Joseph P. Ramler, a graduate student in economics at the University of Montana, examined detailed livestock records over 15 years for 18 ranches in western Montana. Ranchers there typically graze cattle for part of the season on their own pastures, and then, for much of the summer, turn them out onto federal forests and grasslands. Ten of the ranches had lost calves to wolf attacks, and eight hadn’t.

Calculating the loss from an attack is relatively easy, and states have programs to compensate ranchers for the direct loss. But ranchers also complain, according to Ramler and his co-authors, that “wolves decrease the average weight of calves by stressing mother cattle, increasing movement rates, or encouraging inefficient foraging behavior.” That is, the cattle have to spend a lot more time looking around for danger, and a lot less with their heads down in the grass. The study set out to determine if ranchers are simply crying wolf, “or is there evidence that wolves have indirect effects on calf weight?”

First the good news: When the study mapped both the location of cattle and the movement of wolf packs, it found that simply having wolves in the vicinity had no effect on calves. But once a herd experienced an attack, the resulting “landscape of fear” distracted everyone from the business of grazing. When it came time for ranchers to sell those calves at the end of the season, they weighed on average 22 pounds less. For the typical ranch, that translated into a loss of $6,679 per year.

So shoot the wolves, right? On the contrary. While wolves may be the most visible threat to cattle, and even the most enraging one for ranchers, the study found that they explained “only a very small proportion of the change in calf weight,” according to co-author Derek Kellenberg, an associate professor of economics at the University of Montana. Rainfall, extreme heat and cold, breed type, and above all, ranch husbandry, had the biggest effect on how well calves put on weight.

The study doesn’t make any policy recommendations. But Kellenberg points out that recovery efforts for endangered species generally succeed only if they have proper funding. Recognizing the true costs of wolf reintroduction is a way to get that funding and then use it to win the support of ranchers, so they don’t automatically reach for a gun every time they see a wolf.

But fatter compensation programs aren’t the way to get there, says Lisa Upson, executive director of Keystone Conservation, a wildlife group based in Bozeman, Mont. She argues that the ranchers themselves should be working to prevent predator attacks in the first place by managing their herds more actively.

Keeping cattle safe is basically a matter of how the rancher herds them, says Matt Barnes, a former ranch manager who now works for Keystone Conservation teaching ranchers how to do it. Instead of turning cattle loose to wander at large across thousands of acres of known predator habitat, range riders—that is, cowboys—stay with the cattle to watch over them and also move them into the best possible forage.

In “open herding,” the cattle stay relatively spread out, but the riders move them away from creek bottoms, and other areas where they tend to concentrate, and into upland forage. That strategy takes advantage of all the available grazing and avoids causing federal land managers to evict a herd because the creek is being hammered into dust. “Close herding,” on the other hand, involves keeping the cattle in a tighter group, sometimes with the help of temporary electric fences, and moving the herd around in a sort of rotational grazing system. In both systems, the idea is to “rekindle the herding instinct” and train cow-calf pairs to stay together. In predator habitat, there is strength in numbers.

Active management doesn’t work 100 percent of the time, Barnes admits, and all the available measures cost money—typically about $2,000 a month for a range rider. So the ranching community as a whole isn’t buying into it yet. “It’s not what their fathers and grandfathers did,” says Barnes.

“But the good thing is, once you figure it out, it seems to pay for itself,” and it’s not just about avoiding both the direct and indirect costs of predator attacks. Ranchers who have experimented with more active management, says Barnes, find that they can dramatically increase the number of cattle they graze—in one case by 100 percent—and the time spent grazing. It means working closely with livestock—that is, being a rancher—but with the possibility of tens of thousands of dollars of additional income at the end of the season. Getting ranchers to buy into their own future success will, however, require transitional funding for training programs.

But that funding needs to turn up soon. Otherwise, the shooting spree will go on and, soon, the only thing wolf restoration advocates will have to show for their hard work is an empty wilderness.

January 31, 2014

Break Dancing Monastic Fox for Your Weekend Delight

It’s the weekend, and I offer you this break-dancing fox imagined, in an antic moment, by some otherwise dutiful medieval manuscript illuminator. Courtesy of @emergency_fox.

Have fun out there, foxes. Nothing too crazy. Gravity always wins.

This Week’s Cool Green Science News Roundup

Here’s the latest roundup from the Nature Conservancy blog Cool Green Science:

Wildlife

The early bird becomes cat food: New research finds Central American agoutis that get up earlier are far more likely to be eaten by ocelots. Sleep in! (The Agouti Enterprise)

Texas bans the destructive and cruel practice of gassing rattlesnake dens. Finally. (Strange Behaviors) [RC: Well, not yet. But they are working on it.]

Big win for a rare trout: Paiute cutthroats are restored to 100 percent of their original range. (Ted Williams)

Snake on a plane (not): Biomechanist Jake Socha uses a 3-D printer to demonstrate how flying snakes turn their bodies into aerofoils. (Popular Science)

A new book entitled “Are Dolphins Really Smart?” argues no. But maybe the book isn’t so smart, either. (Southern Fried Science)

Conservation Tactics

Why avoided deforestation is paramount for biodiversity conservation – and why financial incentives to protect them should be knockout good. (Conservation Bytes)

Is conservation work in zoos too random? (Conservation Magazine)

Would granting animals “personhood” protect them more effectively than animal protection laws? Verlyn Klinkenborg argues the negative. (Yale Environment 360)

Are we at a turning point for corporations becoming greener in their practices? Or is this just a massive PR move? Fred Pearce takes a critical look. (Yale Environment 360)

Resolved: Ecosystem Services — for or against? (Conservation Letters)

New Research

Doing science (or science writing) outside academia can become an exercise in journal-envy. A list of open-access journals in conservation and ecology can help. (writingfornature)

How green is your roof? And is your roof greener if it’s white? A new study in the journal Energy and Buildings analyzes the most effective methods to make your roof environmentally friendly. (Conservation Magazine)

Plants conduct electricity, but could you grow a circuit? (MIT Technology Review)

We already knew that the switch from hunting/gathering to farming changed the landscape and the human way of life, but a new study showed it changed our genes too. (Science Magazine)

The world’s first magma enhanced geothermal system could bring new meaning to the words lava lamp (UCR Today)

Do protected areas attract migrants? Use appropriate boundaries and statistics to get reliable answers. (Conservation Biology)

Climate Change

Nowhere to run: Climate change is cutting off migration routes of animals like elk and bighorn sheep, threatening to undo one of our greatest conservation success stories. (NWF Reports)

Reporting on resilience: The annual report of the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) touts progress, including crop insurance for 1.1M Indian farmers. (World Bank)

Latest Snowden revelations: US spied on other countries’ negotiators during Copenhagen 2009 climate summit. (Guardian)

Latest victims of climate change: Penguins (Magellanic and Adelie). (Guardian)

Science Communications

If your goal is going viral — you know about emotion and arousal, but what about the secret handshake? (New Yorker)

Making the invisible visible: Why scientists and designers struggle to work together. (FutureEarth)

No one reads blogs. “So why bother?” you say. Yeah, well: No one reads your papers, either. (The Serial Mentor)

This & That

It’s peanut butter jellyfish time. (Deep Sea News)

In which we see another side of Andrew Revkin, and bid a fond farewell to Pete Seeger. (Andrew Revkin)

- See more at: http://blog.nature.org/science/2014/01/31/agoutis-sleep-in-flying-snakes-green-roofs-the-cooler/#sthash.K1DDRvWg.dpuf

The Super Bowl Shame of Roger Goodell

Roger Goodell together with the NFL’s major financial backer (Photo: Alex Brandon/Associated Press)

We are coming into the strange commercial clusterfuck called Super Bowl Weekend. But maybe I shouldn’t say that name out loud.

The National Football League protects its exclusive right to profit from the words S___r B__l so ardently that even communities that surround the stadium, communities that granted tax relief to make that stadium possible, cannot promote the event by name in their own towns. The State of New Jersey can barely mention the event being hosted on its soil. Comedian and Montclair resident Stephen Colbert is calling it Superb Owl Weekend.

This seems like the right occasion to remind everyone that the NFL is a $10 billion a year taxpayer-subsidized nonprofit. Keep this in mind when you are wondering why your town can’t get enough revenue to educate its children, pave its roads, or protect its environment. That money is ending up instead in the pockets of NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell and his band of fat cat colleagues.

In case you missed it, journalist Gregg Easterbrook had a great story on “How the NFL Fleeces Taxpayers” in the September Atlantic. It’s drawn from his book The King of Sports: Football’s Impact on America. I like the way he personalizes the story, by writing about Goodell as a son who has betrayed his own father’s admirable legacy.

Here’s an excerpt:

In his office at 345 Park Avenue in Manhattan, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell must smile when Texas exempts the Cowboys’ stadium from taxes, or the governor of Minnesota bows low to kiss the feet of the NFL. The National Football League is about two things: producing high-quality sports entertainment, which it does very well, and exploiting taxpayers, which it also does very well. Goodell should know—his pay, about $30 million in 2011, flows from an organization that does not pay corporate taxes.

That’s right—extremely profitable and one of the most subsidized organizations in American history, the NFL also enjoys tax-exempt status. On paper, it is the Nonprofit Football League.

This situation came into being in the 1960s, when Congress granted antitrust waivers to what were then the National Football League and the American Football League, allowing them to merge, conduct a common draft, and jointly auction television rights. The merger was good for the sport, stabilizing pro football while ensuring quality of competition. But Congress gave away the store to the NFL while getting almost nothing for the public in return.

Then Esterbrook starts to home in on Goodell:

Roger Goodell’s windfall has been justified on the grounds that the free market rewards executives whose organizations perform well, and there is no doubt that the NFL performs well as to both product quality—the games are consistently terrific—and the bottom line. But almost nothing about the league’s operations involves the free market. Taxpayers fund most stadium costs; the league itself is tax-exempt; television images made in those publicly funded stadiums are privatized, with all gains kept by the owners; and then the entire organization is walled off behind a moat of antitrust exemptions.

And then the kill:

Perhaps it is spitting into the wind to ask those who run the National Football League to show a sense of decency regarding the lucrative public trust they hold. Goodell’s taking some $30 million from an enterprise made more profitable because it hides behind its tax-exempt status does not seem materially different from, say, the Fannie Mae CEO’s taking a gigantic bonus while taxpayers were bailing out his company.

Perhaps it is spitting into the wind to expect a son to be half what his father was. Charles Goodell, a member of the House of Representatives for New York from 1959 to 1968 and then a senator until 1971, was renowned as a man of conscience—among the first members of Congress to oppose the Vietnam War, one of the first Republicans to fight for environmental protection. My initial experience with politics was knocking on doors for Charles Goodell; a brown-and-white Senator Goodell campaign button sits in my mementos case. Were Charles Goodell around today, what would he think of his son’s cupidity? Roger Goodell has become the sort of person his father once opposed—an insider who profits from his position while average people pay.

Read Esterbrook’s full article here. And as you are watching and enjoying the S—-r B–l Sunday night, ask yourself: Isn’t it time for the National Football League to get its hands out of the taxpayer’s pocket and stand, for once, on its own two feet?

January 29, 2014

The Bad News on Monarch Butterflies Just Got Worse

In 2013, the population of monarch butterflies at overwintering sites in Mexico was down by half from 2012. Today the 2014 count, from this past December, is being released, and the numbers are down by half again. Check out the chart for the steady erosion of one of North America’s iconic species. Visit the Monarchwatch blog for the full story, including the loss of an estimated 167 million acres of monarch habitat lost since 1996.

And here’s a press release from the Natural Resources Defense Council:

WASHINGTON (January 29, 2014) –Conservation experts in Mexico today announced that a record low number of monarch butterflies returned this year to their wintering grounds in the mountains of Mexico and their annual migration is at “serious risk of disappearing.” Monarchs, which migrate from Mexico across North America and back every year, have been in serious decline since the 1990s. Experts believe that the widespread use of glyphosate weed killer, sold as Round-Up, in connection with genetically engineered glyphosate-resistant corn and soybeans, may be destroying once-widespread milkweed, which monarchs rely on exclusively for reproduction. Peter Lehner, executive director of the Natural Resources Defense Council, made this statement:

“This news raises a disturbing question that can no longer be ignored: Are our actions causing the rapidly dwindling population of monarchs? We must urgently review the widespread use of glyphosate, which may be wiping out milkweed plants, essential for the Monarchs’ survival. It would be heartbreaking if we inadvertently destroyed in just a few years the millennia-old miracle of the Monarchs’ unique migration.”

Captive Breeding No Help Where Housecats Are Free to Kill

(Photo: Rob & Ann Simpson/Getty Images)

My latest, for Takepart:

In tales of the cat and the rat, society has almost always taken the side of the cat. That has largely continued to be the case in Key Largo, Fla.—with disastrous results for wildlife. The Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge there is one of Florida’s last remaining stands of hardwood hammock forest and home to two highly endangered mammal subspecies—the Key Largo wood rat and the Key Largo cotton mouse.

Right next door to the refuge is a gated community called the Ocean Reef Club, largely developed since the 1960s. Many of its wealthy residents believe they have a right not just to let their own cats roam free but also to feed and care for stray or feral cats in the area. The home owners have maintained that cats do no damage and that roaming free is simply natural for cats. Camera traps have repeatedly shown the cats climbing onto the wood rats’ nests, waiting, and leaping to the attack. Even talking about the effect of house cats on native wild rats has, however, become such an emotional issue that a new study in the journal Biological Conservation carefully avoids ever even mentioning the word “cat.”

Instead, University of Florida wildlife ecologist Robert McCleery and his coauthors focus on the elaborate efforts people have made to save the wood rat from extinction, in spite of the cats. Their results suggest that what had seemed to be the best hope for recovery—a captive breeding and release program—may offer no hope at all. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began taking wood rats from the wild in 2002, to establish the first captive breeding colony of the subspecies, at Lowry Park Zoo in Tampa. Disney’s Animal Kingdom later established a second colony. The Key Largo wood rats are about as charismatic as rats get, cinnamon colored and with big, glossy black eyes. Disney featured an educational program for children about them as part of its tourist attraction in Orlando.

But according to the new study, both programs eventually failed. The Key Largo wood rats lived far longer in captivity—three years versus an average of less than a year in the wild. So the reasonable assumption was that the population would grow faster in captivity than in the wild. That has been the case in the past for two flagship efforts to save endangered species—the California condor and the black-footed ferret. But Key Largo wood rats did not breed well in captivity, with fewer than half the females ever giving birth.

Even worse, when 41 wood rats born in captivity were released back into the wild over a two-year period, they almost immediately fell victim to cats and other predators. Captive breeding hadn’t taught them the vigilance and anti-predator behaviors they needed to survive in the wild. The captive breeding effort, which cost millions, according to one refuge manager, shut down in 2012.

For McCleery and his coauthors, the chief lesson from the experience is that it’s essential to establish beforehand whether the probable benefits of a proposed captive breeding program outweigh the immediate loss caused by removing animals from the wild. That is, does computer modeling with the best available information indicate that captive breeding has a reasonable chance of expanding the existing population? Or could it move a species closer to extinction, as seems to have happened with the Key Largo wood rat?

According to staff biologist Sandra Sneckenberger, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service hopes to use McCleery’s recommendations in the near future, as it decides whether to establish a captive breeding program in the Everglades for the Florida grasshopper sparrow, said to be the most endangered bird in the continental U.S. “Looking at both removals and releases at the same time and modeling different scenarios is a smart approach,” she said.

The other big lesson from the Key Largo wood rat experience is the one McCleery and his coauthors avoid: Even the best-planned and -funded recovery effort cannot protect any small species if people continue to feed and protect a large population of an introduced killer such as the house cat right next door. FWS has attempted to deal with the problem diplomatically. It traps cats on the refuge and delivers them to a nearby animal shelter. The shelter returns identifiable cats to their owners, neuters others for adoption, and euthanizes some unclaimed cats.

Ocean Reef Club continues to practice “trap neuter release” on its own property and claims that this has caused a “dramatic” decrease in its cat population, to 350 feral cats. But those cats just return to the wildlife refuge to kill. Once captured, many of the cats become trap-shy, making recapture difficult, according to refuge manager Jeremy Dixon. But the same animals turn up again and again on camera traps. To protect the wood rats, FWS now builds artificial nests fortified against attack. It also sends out letters to owners of recognized cats warning them that they risk fines for harassing an endangered species. So far FWS has not fined anyone, nor has it made a politically risky stand against the failed practice of “trap neuter release.”

The new study estimates that 78 to 693 Key Largo wood rats remain in the wild. Will this subspecies go extinct? It depends on whether humans, who arrived in Key Largo only recently in the grand scheme of things, decide that an animal with tens of thousands of years of evolutionary history in the habitat has a right to continue surviving there, and that Key Largo will be a better place for having it. (Among other functions, wood rats play a key role in distributing seeds around the hardwood hammock forest, speeding recovery after hurricanes or other disasters.)

But plenty of precedent says Key Largo wood rats should not count on our protection.

January 25, 2014

Dethroned? The Key to Controlling Invasive Lionfish

(Photo: Steve Rosenberg/Getty Images)

My latest for Takepart.

It probably started in the 1980s, with a few tropical fish hobbyists thinking they were doing the humane thing by dumping unwanted pets in the coastal waters of Florida. But introducing the lionfish, which is native to the Indo-Pacific, to the Atlantic Ocean has turned out to be one of the cruelest and most catastrophic tricks ever played on an ecosystem. Now, with the fate of numerous species hanging in the balance, a new paper in the journal Ecological Applications says that scientists have for the first time found a practical way to control the problem.

Lionfish are flamboyantly colorful fish, up to 18 inches in length, striped, and with long, fluttering venomous spines sticking out in all directions. That’s what makes them so attractive in a fish tank. But since their release into the Atlantic, they have spread across an area of 1.5 million square miles, from Venezuela to North Carolina, with stray sightings as far north as southern New England.

In the Caribbean, according to one researcher, it’s common to see lionfish “hovering above the reefs throughout the day and gathering in groups of up to ten or more on a single coral head.” She might just as well have said “hoovering,” because of the speed and thoroughness with which lionfish wipe out native fish populations. They typically flutter their fins to herd smaller fish into a group, and when they have cornered their prey, they pounce.

Because of their extraordinarily painful venom, lionfish have no natural predators. As with many other invasive species, eradication appears to be impossible. Lionfish can repopulate shallow reefs from deepwater populations lurking farther off the coast.

But the study suggests a cost-effective alternative. Getting rid of most—but not all—the lionfish on a given site appears to provide enough relief to allow for the rapid recovery of native species, including commercially important fish like Nassau grouper and yellowtail snapper.

Oregon State University researcher Stephanie Green and her co-authors started with a computer model to calculate a threshold for different habitat types—that is, how many lionfish a site could tolerate and still function normally. Then they tested the model in the field, at 24 coral reef sites near Eleuthera Island in the Bahamas.

The model didn’t make it easy on the field team. To get to the threshold, they had to remove 75 to 95 percent of the lionfish, with the help of nets and spears. On a typical reef site, which is about a third the size of a basketball court, it took about 60 minutes of dive time. Completely eradicating the lionfish would have taken 78 minutes, or 30 percent longer, and that is apparently the difference that makes the method practical.

The researchers then followed up at regular intervals for 18 months. On test sites where the lionfish population was below the threshold, native prey species quickly rebounded, with a 50 to 70 percent increase in total biomass. On sites where the lionfish remained above the threshold, native species decreased by about half.

As that suggests, leaving the lionfish alone is no longer an option, or rather, it’s an option that leaves some native species bound for extinction. But with limited funding for fisheries management across such a vast stretch of ocean, the question is where to apply the control method for the maximum benefit. Because marine reserves typically allow no taking of fish, they are in danger, the new study warns, of becoming “de facto reserves for lionfish.” Mangroves and shallow reefs that serve as nursery sites for young fish are also a likely priority for control measures.

The good news is that there is now a remedy for what had seemed like an unstoppable invasion. But it won’t come cheap, and it should serve as yet another reminder that owning pets comes with grave responsibilities.

Introducing alien species to any habitat can quickly lead to catastrophe, both for wildlife and for us: Not even counting invertebrates, such as Asian long-horned beetles, that are killing off great swaths of forest, invasive species now cost the American public $120 billion every year.

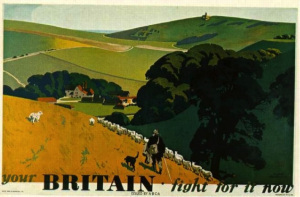

How the British Countryside Got Sheepwrecked

My latest, for The New York Times:

You don’t have to look far to see the woolly influence of sheep on our cultural lives. They turn up as symbols of peace and a vaguely remembered pastoral way of life in our poetry, our art, and in our Christmas pageants. Wolves also rank high among our cultural icons, usually in connection with the words “big” and “bad.” And yet there is now a debate under way about substituting the wolf for the sheep on the (also iconic) green hills of Britain.

The British author and environmental polemicist George Monbiot has largely instigated the anti-sheep campaign, which builds on a broader “rewilding” movement to bring native species back elsewhere in Europe. Until he recently relocated, Monbiot used to look up at the bare hills above his house in Machynlleth, Wales, and seethe inwardly at what Lord Tennyson lovingly called “the livelong bleat/Of the thick-fleeced sheep.” Because of overgrazing by sheep, he says, the deforested uplands, including a national park, looked “like the aftermath of a nuclear winter.” In any direction, there were fewer trees than when he used to work in the semi-desert regions of northern Kenya.

“I have an unhealthy obsession with sheep,” Monbiot admits, in his new book Feral, recently published in the UK and due out next year in the United States. “It occupies many of my waking hours and haunts my dreams. I hate them. “ In a chapter titled “Sheepwrecked,” he calls sheep a “white plague” and “a slow-burning ecological disaster, which has done more damage to the living systems of this country than either climate change or industrial pollution.”

The thought of all those sheep—30 million nationwide—makes Monbiot a little crazy. But to be fair, something about sheep seems to lead us all beyond the realms of logic. The sheep-nibbled landscape that Monbiot denounces as “a bowling green with contours” is beloved by the British public, who regard those ruined uplands as an eternal cultural heritage. Visitors (including this writer, otherwise a wildlife advocate) tend to feel the same when they hike the hills and imagine they are still looking out on William Blake’s “green and pleasant land.” Even British conservationists, who routinely scold other countries for letting livestock graze in their national parks, somehow fail to notice that all 15 of Britain’s national parks are overrun with sheep.

Monbiot recently attacked the Lake District, immortalized by writers from William Wordsworth to Beatrix Potter, as the worst-kept landscape in Britain, because it’s been reduced to nubble by sheep. (The Lake District Park manager shot back, a little too hastily, that “The Lake District has always been able to deliver what people want from it, from Neolithic axes to lead and slate mines.”) Monbiot also attacked children’s books for twisting vulnerable minds with idyllic ideas about sheep farming.

He detects “a kind of cultural cringe” that keeps people from criticizing sheep farming. Sheep have “become a symbol of nationhood, an emblem almost as sacred as Agnus Dei, the Lamb of God,“ he writes. Much of the nation tunes in ritually on Sunday nights to BBC television’s “CountryFile,” which Monbiot characterizes as an escapist modern counterpart to pastoral poetry. “If it were any keener on sheep,” he says, “it would be illegal.”

He detects “a kind of cultural cringe” that keeps people from criticizing sheep farming. Sheep have “become a symbol of nationhood, an emblem almost as sacred as Agnus Dei, the Lamb of God,“ he writes. Much of the nation tunes in ritually on Sunday nights to BBC television’s “CountryFile,” which Monbiot characterizes as an escapist modern counterpart to pastoral poetry. “If it were any keener on sheep,” he says, “it would be illegal.”

In response, the many friends of British sheep have not yet called for burning Monbiot at the stake. “Without our uplands, we wouldn’t have a UK sheep industry, “ Phil Bicknell, an economist for the National Farmers Union protested. “Farmgate sales of lamb are worth over £1bn to UK agriculture, while lamb exports generated £382 million in 2012.” The only wolves he wanted to hear about were his own Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club. A critic in the Guardian, where Monbiot also contributes a weekly column, linked the argument against sheep, rather unfairly, to anti-immigrant nativists, adding “sheep have been here a damn sight longer than Saxons.” (And doesn’t that name Monbiot sound suspiciously Norman?)

More soberly, Oxford geographer John Boardman says the uplands, in the Lake District and elsewhere, have already begun to recover as government policies encourage alternatives to sheep grazing. “I can see George’s point and I can see the value of some reforestation,” says Boardman. “But what he is proposing isn’t minimal or sensitive change. It’s a wholesale change, and pretty impractical in terms of public policy.”

Monbiot acknowledges the antiquity of sheep-keeping in Britain, which has played an important part in the economy for more than 1000 years. But the subjugation of the uplands by sheep, he says, really only got going in the seventeenth century, when the landlords enclosed the countryside, evicted poor farmers, and cleared away the forests from the hillsides and moorlands, particularly in Scotland. When even the National Trust opts to keep the landscape open, Monbiot writes, it is inexplicably choosing “to preserve a 17th-century cataclysm.” The sheep wouldn’t be in the uplands at all, he adds, without annual taxpayer subsidies averaging £53,000 per farm. He proposes an end to this artificial foundation for the “agricultural hegemony,” to be replaced by a more lucrative economy of walking and wildlife-based activities. He also argues for bringing wolves back to Britain, for reasons both scientific (“to reintroduce the complexity and trophic diversity in which our ecosystems are lacking”) and romantic (wolves are “inhabitants of the more passionate world against which we have locked our doors”). But he acknowledges that it would be foolish to force rewilding on the public. “If it happens, it should be done with the consent and active engagement of the people who live on and benefit from the land.”

Elsewhere in Europe, the sheep are in full bleating retreat, and the wolves are resurgent. Shepherds and small farmers are abandoning marginal land at an annual rate of roughly a million hectares, or nearly 4000 square miles, according to Wouter Helmer, co-founder of the group Rewilding Europe. That’s half a Massachusetts every year left open for the recovery of native species.

Wolves returned to Germany around 1998, and they have been spotted recently in the border areas of Belgium, The Netherlands, and Denmark. In France, where the story of Little Red Riding Hood may have originated, the sheep in a farming region two hours from Paris suffered 22 wolf attacks last year. But environmentalists say farmers would do better protesting against dogs, which they say kill 100,000 sheep annually. Wolves are now a protected species almost everywhere, other than Britain, and the European population has quadrupled since 1970s. Today an estimated 11,500 wolves roam there.

Lynx, golden jackals, European bison, moose, Alpine ibex, and even wolverines have also rebounded, according to a recent study commissioned by Rewilding Europe. Helmer says his group aims to develop ecotourism on an African safari model, with former shepherds finding new employment as guides. That may sound naïve. But Helmer sees rewilding as a realistic way to prosper as the European landscape develops along binary lines, with urbanized areas and intensive agriculture on one side and wildlife habitat with ecotourism on the other.

In northeastern Scotland, Paul Lister, a former furniture manufacturer, is already working on an ecotourism scheme to bring back wolves and bears on his Alladale Wilderness Reserve. To get ready, he has planted 800,000 native trees and reintroduced European elk, a traditional food for both wolves and bears.

He still needs government permission to keep predators even on a proposed 50,000-acre fenced landscape, and that’s a long way from getting permission to re-introduce them to the wild, on the model of Yellowstone National Park. But precedent suggests it will be a battle.

Though beavers are neither big nor bad, a recent trial program to reintroduce them to the British countryside caused furious public protest. (One writer denounced “the emotion-based obsession with furry mammals of the whiskery type.’) And late last year, when five wolves escaped from the Colchester Zoo, authorities quickly shot two of them dead. A police helicopter was deployed to hunt and kill another, and a fourth was recaptured. Prudently, the fifth wolf slunk back into its cage, defeated.

Rewilding? At least for now, Britain once again stands alone (well, alone with its 40 million sheep) against the rising European tide.

END

January 24, 2014

This Week’s Wildlife and Conservation News Roundup

Here’s what’s new this week, from The Nature Conservancy Cool Green Science blog:

New Research

Twerking saves lives: well, at least for black widow spiders. Researchers find males shake their bodies rapidly to avoid being eaten by females. (Nat Geo)

Land sparing vs. land sharing – how do we move forward from the debate? (Conservation Letters/open access)

Shaking up the old tree network: How fungi help make space for diversity in tropical forests. (PhysOrg)

E.coli offers clues to dispersal – and possibly control — of invasive species. (Eurekalert!)

Insect soup: It’s not a new meal, but a way to measure biodiversity. (Mongabay) [RC note: And for the same story, five months ago on Strange Behaviors click here.]

Nature has women troubles. After much online criticism, editors of the journal Nature apologize for printing a letter suggesting that gender imbalance is all about the quality of papers received.

And… Nature editor Henry Gee reaps his share of criticism for outing (and dis’ing) anonymous and outspoken advocate of science communication, Dr. Isis. Gee…Isis…Gee…Nature.

Climate Change

Why hasn’t framing climate change as an impending disaster worked to convince more people? New research from Tony Leiserowitz and Ed Maibach suggests the failure of climate change to have immediate disastrous consequences might have convinced fence-sitters that it won’t ever. (Collide-a-Scape)

Yet another downside to suburban living: higher household carbon footprints. UC Berkeley’s Daniel Kammen and Christopher Jones model carbon footprints for 30,000 zip codes in PNAS. (Eurekalert!)

Conservation News

Round up the usual suspects. Following a fatal shark attack, Australian politicians make plans to kill sharks. (Strange Behaviors)

Conserving the last frontier? Scientists call for protection and restoration of deep ocean ecosystems. (Nature)

Another drone application for conservation: unmanned aircraft search for rare and elusive pygmy rabbits. (Boise State Radio)

Biobullet brucellosis vaccine for bison rejected. (TreeHugger)

How to tell if a population is viable in an uncertain world. (Ecology)

Human Dimensions

Nay-sayers take that. The Gates Foundation takes on myths of global poverty. (Philanthropy News Digest)

Science Communications

Does a 1957 paper by William Shockley (yes, the eugenics William Shockley) explain which researchers will be the most productive publishers (as well as the academic superstar system)? (Dynamic Ecology)

Why should scientists talk to reporters and work with their PIOs? It gets you more conference invites, talks with policymakers, and invites to collaborate on research, says a new study. (That is, if you care about that stuff.) (SciLogs)

Jeremy Fox on why there are ecology blogs, but no ecology blogosphere (you could say the same thing for conservation). (Dynamic Ecology)

This & That

Jared Diamond’s ecocide explanation why civilization on Easter Island collapsed has itself collapsed under recent scholarship. But why hasn’t Diamond changed his mind? (Cosmos)

Space conservation? Japan sends giant electromagnetic net into space to clean-up. (New Scientist)

Turkeys inspire new early-warning technology for TNT. (UC Berkeley News)

- See more at: http://blog.nature.org/science/2014/01/24/insect-soup-deep-ocean-restoration-twerking-spiders-more/#sthash.ZJ3Jbenp.dpuf

January 22, 2014

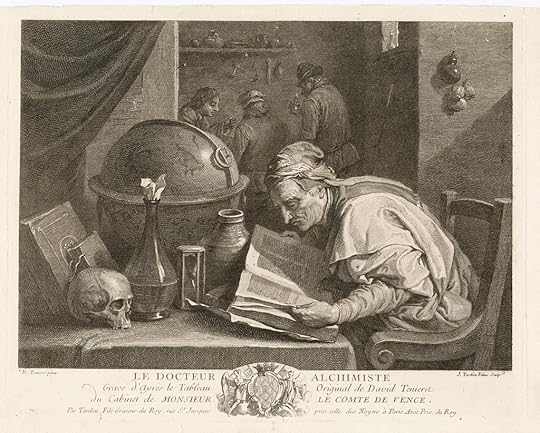

The Scientific Revolution’s Unexpected Debt To Alchemy

The wisdom of the crackpots (Illustration: Engraving after a painting by David Teniers)

My latest, for Smithsonian Magazine, where it appears in slightly different form:

The dark art of alchemy is the sort of thing you were, until recently, more likely to find in a Harry Potter novel than in one of the world’s great scientific research facilities. The alchemist’s perennial dream of transmuting base metals, or almost anything else, into gold was of course hopeless. All the attendant trappings—the strange language and the paranoid secrecy–sounded to modern scientists like fanciful nonsense.

They considered alchemy a ”pathology of thought,” and even “the greatest obstacle to the development of rational chemistry.” Those who dared merely to write about it, the historian Herbert Butterfield once warned, end up “tinctured with the kind of lunacy they set out to describe.”

But to a few revisionist scholars in the 1990s, trying to decipher the coded language of the alchemists and even replicate their experiments turned out to be a useful exercise. Trial-and-error in the lab, combined with close reading of the historical context, revealed, for instance, that a deliberately opaque instruction like “introduce to the eagle the old dragon” meant simply “mix ammonium chloride with potassium nitrate.” A “cold dragon” who “creeps in and out of the caves” was code for saltpeter (potassium nitrate), a crystalline substance found on cave walls that tastes cool on the tongue.

This painstaking process of decoding allowed researchers for the first time to attempt entire alchemical experiments. A recipe for the “Philosophical Tree,” for instance, would supposedly yield a precursor to the more celebrated and elusive “Philosopher’s Stone.” And for alchemists, the “Stone,” if they could ever attain it, would have been the elixir of life, health, wealth, and power.

One day in the mid-1990s, following a recipe for the “Philosopher’s Tree” cobbled together from obscure texts and scraps of eighteenth-century laboratory notebooks, chemist and science historian Lawrence Principe mixed mercury and gold into a buttery lump at the bottom of a flask. Then he buried the sealed flask with this “egg” in a heated sand bath, in his laboratory at Johns Hopkins University.

For several weeks, nothing happened. He varied the temperature, and the egg began to swell a little and become “partly covered with warty excrescences.” For alchemists, the ambition was to produce a golden product, and using gold to produce more gold would have seemed entirely logical, Principe explains, like using germs of wheat to grow an entire field of wheat.

One morning soon after, Principe came into the lab to discover to his “utter disbelief” that the bulb of the flask had filled, as the recipe had promised, with “a glittering and fully formed tree” of gold. (In photographs, it looks like a head of coral, or like the branching canopy of a tree minus the leaves.) For an early alchemist, Principe writes, in his recent book The Secrets of Alchemy, it would have been “vivid and unquestionable proof that he had found the ‘entrance to the place of the king,’ that is, the crucial threshold leading to the Philosophers’ Stone.”

What intrigues Principe and his fellow revisionists, though, is the tantalizing idea that the alchemists might actually have known what they were doing. Their theories, their language, and their relentless quest for gold may have been far-fetched. Yet the alchemists now seem to have performed legitimate experiments, manipulated and analyzed the material world in interesting ways, and reported genuine results. And many of the great names in the canon of modern science took note, says William Newman, a science historian at Indiana University and a leader of the revisionist movement.

Robert Boyle, one of the eighteenth-century founders of modern chemistry, “basically pillaged” the work of the German alchemist Daniel Sennert, says Newman, When Boyle’s French counterpart Antoine Lavoisier substituted a modern list of elements (oxygen, hydrogen, carbon, and others) for the ancient four elements (earth, air, fire, and water), he built on an idea that was “actually widespread in earlier alchemical sources,” Newman writes. The concept that matter was composed of several distinctive elements, in turn, inspired Sir Isaac Newton’s work on optics—notably, his demonstration that the multiple colors produced by a prism could be reconstituted into white light. (Newton even authored his own alchemical manuscript.) Francis Bacon, revered as the inventor of the experimental method, likewise drew on experimental precedents established by alchemists.

Instead of representing an intellectual dead end, alchemy has increasingly come to look like the beginning of modern science. Other scholars have at times responded to this idea with outrage. Once at an academic conference in the 1990s, a member of the audience confronted Principe “literally shaking with rage that I could defame Boyle in this way.” More recently, a reviewer criticized the revisionists for “trying to airbrush out of the record elements that seem to us less attractive” about alchemists, notably their tendency to fraud, bankruptcy, and the occult.

But younger scholars have taken up alchemy as a hot topic. The early revisionist research, says Principe, “cracked open the seal and said ‘Hey, look everybody, this is not what you thought it was,’ And it’s really taken off. It was a surprise, and people like a good historical surprise.”

In a mark of that new acceptance, the Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf, Germany, will present a show, beginning this April, on “Art and Alchemy–The Mystery of Transformation.” Along with alchemy-influenced art works from Jan Breughel the Elder to Anselm Kiefer, it will include an exhibit on Principe’s “Philosopher’s Tree” experiment.

Does this new view of alchemy make the great names in the early history of modern science seem more derivative and thus less great? “We were just talking in my class about the rhetoric of novelty,” says Principe, “and how it benefits people to say that their discoveries are completely new.” But that’s not how scientific ideas develop. “They don’t just sort of come to someone in a dream, out of nowhere. You learn what exists as a young person, and then you develop and change it gradually.”

From that perspective, the scientific revolution may have been a little less revolutionary than we imagine. Better to think of, it like changing lead to gold, as a transmutation