Richard Conniff's Blog, page 57

January 13, 2014

Is This the Year of the Passenger Pigeon?

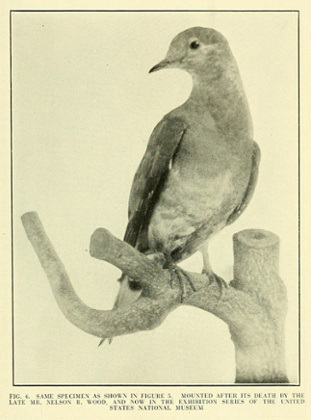

Passenger pigeon diorama (Photo:Curious Expeditions/Flickr/Creative Commons License)

A hundred years ago this September, humans achieved the impossible, catastrophically. Passenger pigeons had numbered in the billions just 54 years earlier. But senseless slaughter had now reduced the species to a sole surviving female, named Martha, in the Cincinnati Zoo, and on September 1, 1914, at 1 p.m., she died. Henry Nicholls writes about Martha today in The Guardian. He quotes a vivid eyewitness description of the passenger pigeon migration at Niagara, NY, in 1860:

“I was perfectly amazed to behold the air filled and the sun obscured by millions of pigeons, not

Martha in her final resting place

hovering about but darting onwards in a straight line with arrowy flight, in a vast mass a mile or more in breadth, and stretching before and behind as far as the eye could reach,” he wrote in The Sportsman and Naturalist in Canada.

The flock took 14 hours to pass overhead and, based on a flying speed of 60mph, King estimated that “the column … could not have been less than three hundred miles in length”.

And he describes what happened to Martha’s preserved body, on display at the National Museum of Natural

History. He also writes:

The plight of “last individuals” – think Lonesome George – is always going to move people, especially when the hand of humankind has been so heavily involved in the extinction. So it seems likely that 2014 will be the year of the passenger pigeon as people mark the centenary of Martha’s death.

In addition to Greenberg’s excellent book, which devotes a chapter to Martha and boasts a terrific appendix of passenger pigeon-related miscellany, we can also look forward to A Message to Martha by Mark Avery, former conservation director at the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Martha herself will be the star turn in a special exhibition at NMNH. Once There Were Billions: Vanished Birds of North America will run from 27 June 2014 to 14 June 2015 and tell the story of the passenger pigeon and other extinct birds, including the great auk, the Carolina parakeet and heath hen.

Check out the full article–including an unsolved biological puzzle–here.

January 11, 2014

Holy Crap! These Are Some Scary Slave Raiders

These modern slave-raiders work on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan, up around Traverse City, Michigan, and the secret of their success is traveling light and quick. They also employ chemical camouflage and have a deft way of murdering anyone that gets in their way.

European researchers discovered this astonishing behavior. They’ve named the species Temnothorax pilagens, from pilere (Latin): to pluck, plunder or pillage. The paper is just out in the open access journal ZooKeys. Here’s the press release

In contrast to the famous slave-hunting Amazon Ants whose campaigns may include up to 3000 warriors, the new slave-maker is minimalistic in expense, but most effective in result. The length of a “Pillage Ant” is only two and a half millimeters and the range of action of these slave-hunters restricts to a few square meters of forest floor. Targets of their raiding parties are societies of two related ant species living within hollow nuts or acorns. These homes are castles in the true sense of the word — characterized by thick walls and a single entrance hole of only 1 millimeter in diameter, they cannot be entered by any larger enemy ant.

An average raiding party of the Pillage Ant contains four slave-hunters only, including the scout who had discovered the target. Due to their small size the raiders easily penetrate the slave species home. A complete success of raiding is achieved by a combination of two methods: chemical camouflage and artistic rapier fencing.

The observed behavior is surprising as invasion of alien ants in an ant nest often results in fierce, usually mortal, fighting. Here, however, in several observed raids of the Pillage Ant, the attacked ants did not defend and allowed the robbers to freely carry away broods and even adult ants to integrate them into the slave workforce. The attacked ants did not show aggression and defence because the recognition of the enemy was prevented by specific neutralizing chemical components on the cuticle of the slave-hunters.

The survival of slave ant nests is an ideal solution from the perspective of slave hunters as it provides the chance for further raids during the next years. In other observed raids chemical camouflage was less effective — perhaps because the attacked ant population was strongly imprinted to a more specific blend of surface chemicals. In fact, a defence reaction was more probable if the attacked colony contained a queen that causes a strong imprinting of chemical recognition cues.

If defending, the chance of a slave ant to win a fight with a Pillage Ant is nearly zero. The attackers use their stinger in a sophisticated way, targeting it is precisely in the tiny spot where the slave ant’s neck is soft-skinned. This stinging causes immediate paralysis and quick death and may result in high rates of casualties ranging from 5% to 100% of the attacked nests’ population, whereas there are no victims among the attackers. If the Pillage Ants can conduct such successful raids with no or minimum own losses, there remains the question which factors regulate their population at a rather low level.

Do You Really Want to Pay for This Senseless Poisoning?

My latest for TakePart:

Sometimes just trying to get along with a difficult neighbor can make us prisoners in our own homes. It can lead us to do things that go against our own stated intentions and interests. That seems to be the right now for the Thunder Basin National Grassland, a 547,000-acre protected area in northeastern Wyoming.

The U.S. Forest Service, which manages the Grassland, has announced a plan to poison an estimated 16,000 prairie dogs and dramatically shrink the already limited area in which prairie dogs are tolerated. Thunder Basin officials intend to do it despite their own declared plans to improve prairie dog habitat. Their method, moreover, is likely to kill a lot of other wildlife in the affected area and, incidentally, squander taxpayer dollars for nothing.

USFS is proposing this outlandish venture under pressure from neighboring cattle ranchers and politicians, particularly Wyoming Governor Matt Mead, and to appease “a dedicated few who cling to archaic, erroneous concepts” about prairie dog biology. The quote comes from Jason A. Lillegraven, a vertebrate paleontologist who has retired from the University of Wyoming but still finds himself dealing with dinosaurs.

Just five years ago, the same Thunder Basin managers set aside 85,000 acres as one of the last refuges in the American West where prairie dogs could not be poisoned, gassed, shot for target practice, set on fire, or otherwise harassed into extinction. The thinking then was straightforward: Only two percent of the America’s prairie grasslands remain intact, and Thunder Basin represents one of the best remnants of that storied heritage. Meanwhile, black-tailed prairie dogs have lost an estimated 99 percent of their habitat.

Giving them a tiny scrap of land on which to survive seemed to make sense in part because so many other species that are emblematic of the American West depend on them: Their burrows provide homes for mountain plovers and burrowing owls, and the prairie dogs themselves are a favorite prey of golden eagles, ferruginous hawks, and swift foxes, among others. Thunder Basin has targets to increase populations of all those predators. It also ranks high up among the candidate sites for transplanting a population of endangered black-footed ferrets—and the ferrets cannot live if there aren’t enough prairie dogs for them to eat.

Nearby ranchers, on the other hand, regard prairie dogs as a menace on multiple counts and want them gone. So the new plan calls for killing any prairie dog within a quarter mile of private land.

Other prairie dog poisoning campaigns—and they are legion—have generally relied on zinc phosphide, which is fast-acting and with minimal risk of secondary poisoning to other species. But prairie dogs that survive a whiff of zinc phosphide may learn to steer clear of it.

The new plan calls instead for using the notorious anticoagulant Rozol. “Rozol makes creatures that ingest it bleed from every orifice and stagger around for the week or two or three it takes them to die, attracting predators and scavengers,” the environmental writer Ted Williams reports. “Whatever eats the anticoagulant-laced victim dies, too.”

Using Rozol requires lots of taxpayer-funded labor to monitor the area and pick up carcasses before scavengers can get to them. But in most cases the monitoring gets forgotten, says Williams. The unintended victims include “golden eagles, bald eagles, ferruginous hawks, owls, magpies, turkey vultures, badgers, swift foxes, coyotes, raccoons, red-winged blackbirds, wild turkeys, and almost certainly, ferrets.”

What’s the argument for killing prairie dogs? Ranchers sometimes cite the threat of plague—and the black death certainly sounds terrifying enough. But it typically affects fewer than 10 people each year in the United States, and if caught early, is easily treated with antibiotics. Victims tend to be wildlife biologists and hunters. In the rare cases where the victim hasn’t directly handled a sick animal, it’s generally because a free-roaming house cat has wandered into an infected prairie dog town. The way to prevent the problem isn’t by killing prairie dogs, but by dusting prairie dog towns to minimize fleas.

The larger problem is that any prairie dog town is messy, a warren of burrow holes and bare earth. That can make a rancher feel like a sloppy land manager. They tend to refer to prairie dogs as invaders, though fossil evidence is clear that prairie dogs predate cattle ranchers by quite a bit (about two million years, or longer than humans have been a species.)

The visual evidence also suggests to ranchers that the prairie dogs are eating grass that ranchers feel rightly belongs to their cattle, but the scientific evidence on competition with livestock is mixed. Pronghorn, elk, and bison actually prefer to graze in prairie dog towns, evidently because the prairie dog wastes make for vegetation that’s richer in nitrogen. And a 2013 study found that prairie dogs can make things better for livestock, too, at least when it rains. Unfortunately, they make it worse in a drought, and it’s human nature that the credit you get for making a good thing better is not nearly proportionate to the blame you get for making a bad thing worse. The West has been enduring drought conditions for more than a decade, and that makes the prairie dog a handy scapegoat for desperate ranchers.

Is that reason enough for USFS managers to reverse every carefully laid plan for the protection of wildlife in an area that has, after all, been set aside largely for wildlife and recreation?

“I have a strong sense that they do not want to do this,” says Steve Forrest, of Defenders of Wildlife. “They don’t have the budget for it, and they know in their hearts that it makes no sense.” Their own fact sheet says any gain in weight for livestock from getting rid of prairie dogs is worth less than the cost of proposed poisoning. “But when the governor of Wyoming speaks, they have to pay attention.”

The managers at Thunder Grass National Grassland declined to be interviewed for this article. They’re probably too embarrassed. But you can email district manager Tom Whitford at twhitford@fs.fed.us.

Better yet, contact Wyoming Gov. Matt Mead here, or at 307-777-7434, and also let your own representatives in Congress know what you think.

How Did Monkeys Cross the Atlantic? A Near-Miraculous Answer

The question of how species came to live where they live is one of the enduring puzzles in biology: How did a big flightless bird like the now-extinct moa find its way to New Zealand? How did monkeys cross the Atlantic from Africa? Why does an insect-eating plant on a remote plateau in Venezuela have its nearest living relative at the other end of the Earth, in Australia?

The question of how species came to live where they live is one of the enduring puzzles in biology: How did a big flightless bird like the now-extinct moa find its way to New Zealand? How did monkeys cross the Atlantic from Africa? Why does an insect-eating plant on a remote plateau in Venezuela have its nearest living relative at the other end of the Earth, in Australia?

Beginning in the 1960s, with the triumphant vindication of continental drift and plate tectonics, “vicariance” became the standard answer for evolutionary biologists. It’s what happens when a barrier—a mountain range, or an ocean, say—separates a species into two or more populations and sends them down diverging evolutionary paths. (The word comes from the Latin vicarius, meaning a thing that takes the place of something else, like a vicar standing in for a bishop.)

In this new view of geological history, all of the land masses of the modern world once huddled together in the ancient supercontinent Pangaea. As these land masses drifted apart to their present positions, they simply carried plants and animals with them—or so vicariance proponents argued.

To nonscientists, this may sound like a straightforward and not particularly controversial development in intellectual history. But in his lively new book The Monkey’s Voyage: How Improbable Journeys Shaped The History of Life, biologist Alan de Queiroz reveals just how loaded it was with anti-establishment furor.

Vicariance, together with the ideas on which it was built, were “movements heavily fueled not just by intellectual considerations, but also by this radical belligerence that at times seemed like a stratagem,” Mr. de Queiroz writes. He enlivens his tale with vivid portraits of combatants, notably the French-born eccentric Léon Croizat, who began self-publishing his massive tomes on biogeography in the 1950s, and Gary Nelson, who started out as a young rebel in the late 1960s at the American Museum of Natural History. Vicariance proponents favored a “style of argument based on equal parts shouting and sarcasm,” with the heaviest sarcasm heaped on “dispersalism,” the old, supposedly untestable idea that plants and animals arrived at their present locations more or less on their own power, through a series of chance long-distance voyages.

“Damned benighted dispersalism,” as de Querioz calls it, with tongue in cheek, dates back to Charles Darwin, who proposed that drifting icebergs may have served as a means of transport, and to early Biblical scholars, who theorized that, after Noah landed on Mt. Ararat, his menagerie dispersed around the world as cargo on ships, or by traveling from island to island, stepping-stone fashion.

To Croizat, dispersalism was “a world of make-believe and pretense” and for Nelson it was “a science of the improbable, the rare, the mysterious, and the miraculous.” Vicariance relied, by contrast, on the hard science of plate tectonics and on cladistics, a new way of organizing species into more carefully distinguished evolutionary lineages, according to shared traits.

All this gave vicariance a kind of mythic power, with the paradoxical result, as de Queiroz recounts it, of blinding true believers to the evidence that species disperse over unlikely distances even now. Among the many examples he cites, white-faced herons migrated at least 1300 miles from Australia to populate New Zealand in the 1940s, and green iguanas populated the Caribbean island of Anguilla in 1995, after a hurricane carried them 175 miles from Guadeloupe.

The new science of molecular clocks–timelines based on careful analysis of changes in DNA–argues even more powerfully that vicariance alone cannot explain why many species occur where they do, according to de Queiroz. Monkeys, for instance, originally came to South America from Africa. The vicariance argument suggests that this happened as the two continents pulled apart roughly 100 million years ago. But numerous molecular clock studies say the split between Old and New World monkeys happened just 30 to 50 million years ago. Moreover, monkeys only appear in the New World fossil record “as if out of thin air” 26 million years ago.

So how did they get there? De Queiroz makes a scientific case for the near-miraculous: Land rafts periodically calve off the continents and drift long distances with the current, he writes. When such a raft carried a few pioneering monkeys to South America 40 million years ago, the Atlantic may have been just 900 miles wide and powerful currents could have shortened the trip to as little as a week.

Molecular clocks also undercut the idea that the flightless moa, that “most iconic” example of vicariance, got to New Zealand via continental drift alone. Instead, de Querioz writes, new genetic evidence places South America’s tinamou, a bird that can fly despite being heavy-bodied, deep in the same evolutionary line, implying that the moa could have flown to New Zealand and only later become flightless. And if monkeys and moas could make such voyages, so could smaller animals and of course plants.

De Queiroz manages to keep this story both informative and highly entertaining. He’s not a polemicist, but a raconteur, a guide down the boulevard of ideas, pointing out colorful characters on route. He introduces Kary Mullis, for instance, as an LSD-sampling madman who once skiied down an icy street in Aspen with traffic speeding by on both sides, convinced that he would die only by hitting a redwood, “and there weren’t any redwoods in Aspen.” Mullis turns out to matter to the story because he developed the fundamental technology of the DNA revolution—and won the Nobel Prize for it.

De Queiroz is also perfectly willing to admit when some piece of evidence doesn’t quite measure up, but is merely the best we have to go on at the moment. “It is the business of evolutionary biologists and other historical scientists,” he writes, with disarming honesty, “to draw conclusions from obviously flawed and potential misleading information. That is simply the nature of historical evidence …”

The resulting tale of how the world was populated willy-nilly—and of our own fumbling attempts to understand it–makes for a splendid intellectual history.

This is a book review I wrote for the Wall Street Journal

January 10, 2014

This Week’s Cool Green Science Favorites

Every Friday, The Nature Conservancy’s Cool Green Science blog publishes a roundup of the week’s cool conservation and conservation science stuff .

With their permission, I’m going to pass along their finds every Friday.

Wildlife

What is the legal status of a de-extinct animal? Is it endangered and, if so, would governments work to protect wooly mammoths and dodos? Carl Zimmer explores the possibilities. (The Loom)

Forget the NFL playoffs. Richard Conniff wants a new rivalry: “My city has more wildlife than yours.” Inside the growing urban conservation movement. (Strange Behaviors)

You might be heading to the gym to shed those holiday pounds, but not ducks. They need all the calories they can get this winter. Research shows that winter food availability has dramatic effects on spring nesting success. (Ducks Unlimited)

Collaring mystery cats: New research attempts to unveil secrets of the elusive clouded leopard in Borneo. (Focusing on Wildlife)

Climate Change

Lists are a-chatter over Robert Brulle’s study of the $1B +”dark” financing of the Climate Change Counter-Movement (CCCM) — and the Guardian’s coverage of it. Forbes challenges the premise. (The Guardian)

In case you missed it over the winter holidays, the first results of the Intersectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project came out in PNAS in December. The group fingered water scarcity as the clearest and most severe climate change impact. (PNAS)

Warming could upset Antarctic food chain by shrinking habitat for Antarctic krill. (Mongabay)

You may have checked your carbon footprint, but what about nitrogen? Scilogs explains how this greenhouse gas is having an intense impact in the Alaskan Arctic. (SciLogs)

Why might some mushrooms be magic for climate change? Bryan Walsh looks at a new study showing that ecto- and ericoid mycorrhizal (EEM) fungi contain as much as 70% more carbon than soils dominated by arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi. (Time)

New Research

What does elephant poaching have to do with infant mortality rates? A lot, says a new study. (Slate)

Mosquitoes love edges–and logging, fire, and roads make more edges. Modeling the relationship between malaria and land use, researchers found that low-level selective logging (

People have often assumed that hunter-gatherers went hungry more often than agriculturists. Not so…finds a study in Biology Letters analyzing famine frequency and severity in a large, cross-cultural database. (Biology Letters)

Invasion alert. Invasivore spotlights new research on why non-native plants become successful invaders — and why climate change could make these invasions worse. (Invasivore)

Why more biodiversity = more ecosystem resilience: the definitive takeout? (Conservation Bytes)

What’s up with That?

Why are prairie dogs starting a wave? Ed Yong explains the science behind the jump-yip alert and how it is similar to human yawning. (Not Exactly Rocket Science)

Marine life is dying, but those who link die-offs to Fukushima radiation are dead wrong. Craig McClain of Deep-Sea News explains how the rumor got started and why it is false. (Deep Sea News)

What came first, the rain or the rain forest? Henry Reich (via Robert Krulwich) offers a fun, fast-paced look at the relationship between trees and climate. (NPR)

Science Communications

Think more facts should be more persuasive? Not so fast. Turns out that in many situations three reasons are better than 4…or 5…or 6. (New York Times)

Amy Harmon’s brilliant piece on one man’s frustrating quest to find the scientific truth about GMO crops and apply it to a heated debate on banning them in Hawaii. (New York Times)

What scientific questions do you get asked at parties – and what do they tell us about society? (Dynamic Ecology)

Have suggestions for next week’s Cooler? Send them to mdowns[at]tnc.org.

Opinions expressed on Cool Green Science and in any corresponding comments are the personal opinions of the original authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Nature Conservancy.

- See more at: http://blog.nature.org/science/2014/01/10/rights-of-de-extinct-animals-dark-money-magic-mushrooms-more/#sthash.Z3edzhop.dpuf

Mystery of the War Elephants Solved

This artist’s explanation was that

North African forest elephants (left) are smaller than Indian elephants (right). (Source: wildfiregames.com )

Scholars have been arguing almost forever over the “War of the Elephants,” which took place in 217 B.C. between Ptolemy IV, King of Egypt, and Antiochus III the Great, whose kingdom reached from modern-day Turkey to Pakistan.

The battle (also known as the Battle of Raphia) took place in what is now Rafah, in the southern Gaza Strip, on the border between present-day Egypt and Israel. It was the only known battle in which Asian and African elephants faced off against each other. The great mystery, until now, was why historical accounts described the African elephants as smaller and less powerful than their Asian counterparts.

That never made much sense because we know that the largest African savannah elephants are bigger on average by about a half meter and 1000 kilograms. The historical account said Ptolemy, leading the army with the African elephants, had commandeered his elephants from what is now Eritrea, on the Red Sea, home to the northernmost population of savannah elephants. Some scholars (and the unknown artist for the illustration above) argued that he had obtained African forest elephants rather than savannah elephants. Forest elephants are a closer match in size with Asian elephants, and research has recently demonstrated that they are a separate species from savannah elephants.

So did Eritrea have forest or savannah elephants?

Now a study in The Journal of Heredity proposes a DNA-based answer. Alfred Roca from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and his co-authors analyzed the DNA of the last surviving Eritrean elephants, a population of about 100 animals on the country’s southwestern border with Ethiopia.

In the battle, Antiochus had 102 Asian war elephants, and Ptolemy had 73 African war elephants. Describing what happened 70 years later, the Greek historian Polybius wrote:

A few of Ptolemy’s elephants ventured too close with those of the enemy, and now the men in the towers on the back of these beasts made a gallant fight of it, striking with their pikes at close quarters and wounding each other, while the elephants themselves fought still better, putting forth their whole strength and meeting forehead to forehead.

Ptolemy’s elephants, however, declined the combat, as is the habit of African elephants; for unable to stand the smell and the trumpeting of the [Asian] elephants, and terrified, I suppose, also by their great size and strength, they at once turn tail and take to flight before they get near them.

Over the years, there has been a lot of speculation about Polybius’s account. “Until well into the 19th century the ancient accounts were taken as fact by all modern natural historians and scientists,” says Neal Benjamin, an Illinois veterinary student who studies elephant taxonomy and ancient literature with Roca, “and that is why Asian elephants were given the name Elephas maximus. After the scramble for Africa by European nations, more specimens became available and it became clearer that African elephants were mostly larger than Asian elephants. At this point, speculation began about why the African elephants in the Polybius account might have been smaller. One scientist, Paules Deraniyagala, even suggested that they might even have been an extinct smaller subspecies.”

In fact, analysis of mitochondrial DNA from present-day Eritrean elephants reveals that they are actually savanna elephants. But what does that say about the elephants that lived there 2300 years ago, at the time of the battle?

Mitochondrial DNA tends to be better preserved than nuclear DNA and provides a window into the mating history of a species. It ” is the ideal marker because it not only tells you what’s there now, but it’s an indication of what had been there in the past because it doesn’t really get replaced even when the species changes,” says Roca . Contrary to what some scholars had theorized, mitochondrial DNA revealed no genetic ties to forest or Asian elephants. Though they are now isolated, Eritrean elephants are most closely related to other populations of East African savanna elephants.

So why did Polybius say they were outclassed by their Asian counterparts? The new study doesn’t try to answer that key question. But it’s likely that populations from a dry, sparsely vegetated region like modern Eritrea were simply smaller because of available resources. African elephants have also rarely been tamed well enough to be reliable in battle.

By the way–and I know you have been waiting desperately for the outcome–Ptolemy won anyway, and he did it the usual way, with skilled, disciplined, and determined foot soldiers.

POST SCRIPT: The researchers hope their findings will aid conservation efforts. The remaining Eritrean elephants are isolated and inbred. They require habitat restoration and monitoring. Ideally, future conservation efforts couldestablish a corridor connecting Eritrean population to other the East African savanna elephants. But that is unlikely. Short of that, deliberate introductions may be necessary to provide genetic diversity.

January 9, 2014

Fish Leaps, Takes Down Bird on The Wing

O.k., in recent months we’ve seen an eagle tackling a saiga deer, and an Australian wedge-tailed eagle carrying off a fox.

Now comes proof that, while birds may be dinosaurs once removed, even a fish will now and then take one down.

Here’s the report from Daniel Cressy at Nature:

The waters of the African lake seem calm and peaceful. A few migrant swallows flit near the surface. Suddenly, leaping from the water, a fish grabs one of the famously speedy birds straight out of the air.

“The whole action of jumping and catching the swallow in flight happens so incredibly quickly that after we first saw it, it took all of us a while to really fully comprehend what we had just seen,” says Nico Smit, director of the Unit for Environmental Sciences and Management at North-West University in Potchefstroom, South Africa.

After the images did sink in, he adds, “the first reaction was one of pure joy, because we realized that we were spectators to something really incredible and unique”.

Read the full account here.

January 8, 2014

When Did Libraries Start Committing Plagiarism?

This is an entertaining piece, published by the University of London’s Senate House Library on its web site.

The author credits me at one point, and also flatters me, and I guess she thinks that’s sufficient. Here’s the problem: She doesn’t let on–with primitive devices like the quotation mark–that I happen to have written at least the first five paragraphs, or roughly half the article, word for word. You will find the originals starting here and also here.

University of London. Sounds like a big deal. I googled it. It was founded 175 years ago and includes such eminent institutions as The London School of Economics and the genuinely heroic London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Could someone there please stop by the library and let them know the definition of plagiarism? Or am I just being fussy?

The science of smiling began on the guillotine

Posted on February 15, 2013 by Andrea Meyer Ludowisy

Image credit: Wellcome Images

In the 1840s, a Paris physician named Guillaume B.A. Duchenne was attempting to treat a patient’s facial neuralgia when he noticed that applying an electrical current caused the underlying muscle to contract sharply. As technique was too painful for experiments on living patients, Duchenne, the ever resourceful son of a French coastal buccaneer, started to work with the freshly severed heads of executed criminals and revolutionaries. To his great disappointment, these specimens did not naturally display the sort of joyful smile Duchenne would later describe as “put in play by the sweet emotions of the soul.” But by applying live electrodes to different areas of the face, he found that he could indeed make the muscles contract into recognizable facial expressions, including the smile.This story is told by Richard Conniff, a most erudite and entertaining science writer whose blog and newest publication chronicle the strange behaviours of the natural and human worlds.

Duchenne eventually moved on to living subjects, beginning with an elderly indigent whose neurological disorders apparently protected him from the pain of electrical experimentation.

And thus Duchenne demonstrated for the first time the mechanistic nature of human facial expressions. He argued that smiling, and other familiar expressions, constitute a universal language “which neither fashions nor whims can change … the same in all people, in savages and civilized nations …” This idea didn’t win wide acceptance at the time and 150 years later some still argue that culture trumps biology by pointing out that Japanese smile less because of social pressure that discourages emotional displays or by arguing that women smile more because society obliges them to pacify surly males.

However, most researchers accept that facial expressions are innate and that our facial expressions, and especially the smile, constitute a system of unconscious communication that got built into our biology long before language itself. People often equate smiling with just one emotion, happiness and thereby make it one of the most potent symbols of co-operation. But a smile can mean almost anything: biologists say the smile got its start in fear, not happiness. Darwin thought the smile was merely the first step towards laughter, the fear grin could have been a way of saying “Don’t eat me, I am harmless”. As most of us know from the work environment, the fear grin evolved from a form of appeasement into a display of friendliness and often into something far richer and more varied than that. A smile can communicate feelings as different as love or contempt, pride or submission, flirtatiousness or polite tolerance. It can be deeply comforting and reassuring or it can induce a chill of fear – Hannibal Lecter smiled when thinking of fava beans and Chianti.

A smile can keep readers in a library happy or send them into a rage. Despite the common phrase, there is no such thing as a simple smile. The human appetite for smiles makes us look for them everywhere. If something looks remotely human, we humanize it. Clifford Nass, a communication professor at Stanford University blames this tendency for one of the worst software blunders in the annals of computing which turned on the simplistic notion that everyone likes a smile. Nass blamed this on dancing raisins. In the late 1980s the California Raisin Advisory Board had a huge hit promoting its product with cartoon raisins, who smiled ebulliently and sang “I heard it through the grapevine” At about the same time, Clifford Nass talked to Bill Gates and other Microsoft executives about using animated characters as a way of making computer appear more human. And thus was born Clippy, the cartoon “Office Assistant” who appeared with rictus smile and inane assumptions when help was not needed and did not know when it was time to stop smiling.

This fascinating new publication in the Western European Languages research collection deals with the power of the smile and humour in Spanish culture. Our richest source of information about smiles is literature; at least this is the opinion of John Rutherford, the author of “The Power of the Smile”. Humour in Spanish Culture”:

The book explores the complex relationship between the smile and the laugh and traces its historical development in Spanish life and culture. The principal source for this study of the smile is literature, but it also contains the first detailed study of the earliest expressive smile in medieval sculpture, the smile worn by the prophet Daniel in the the Pórtico da Gloria of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in Spain which is reproduced on the back cover. Rutherford takes Galician irony or retranca, and the sarcasm or guasa of Madrid and Seville as characteristic forms of the smile and the laugh in literature respectively.

Rutherford concentrates on the medieval and early modern periods as he is interested in the transition between what he calls the “ancient fun – the fun of mockery” and “modern fun- the fun of understanding”. To this end, he traces the concept humour from its earliest uses in literature of the 14th century when humour referred to any fluid or moisture in the human body through to the 16th century when the term designated physical and mental qualities to the narrowing of the meaning to “any eccentric mental quality caused by an excess of any of the four bodily fluids” as described in Ben Jonson’s play of 1598 “Every Man and His Humour”: http://encore.ulrls.lon.ac.uk/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1719550

By the 18th century “humour” was being used to refer to anything in human behaviour that caused amusement. However, by the late 18th century and the early 19th century the Romantics displayed a preference for restrained amusement tinged with sadness and under this influence “humour” changed its meaning to denote the attitude which remained prevalent and influential into the 20th century. One of the first and most influential 20th century writers on humour was Sigmund Freud’s friend Theodor Lipps with his seminal work “Komik und Humor” of 1898. Freud would later begin his seminal “Jokes and their relation to the Unconscious” with a detailed consideration of Lipps’ ideas.

Rutherford makes a convincing case as to why we can learn a great deal from the “remarkable and much maligned world of the Middle Ages” when he shows how the foundations for our culture were laid during this time. He devotes his book to the examination of four canonical books, the Poema de mio Cid, Libro de buen amor, Celestina and of course, Don Quixote. Even though the books’ emphasis is on the literature of the early modern period, the book makes ample use of the ideas of a great many theorists and Rutherford leads the reader effortlessly from the early modern period to our present day. He advances a way of reading which can bring the modern reader closer to the medieval sensibility which he calls an “informed imaginative engagement with the texts” which he achieves by bringing a willingness to the subject to accept the results of this engagement even if the results challenge conventional wisdom. His approach brings the texts from the 15th to the 21st century with all their ambiguities alive.

Here’s Why It’s A Mistake to Discount China’s Ivory Crush

Ivory going into the crusher Monday morning in Guangzhou (Photo: PLAVESKI/SIPA/REX)

Among many Western environmentalists, the response to China’s public destruction of confiscated ivory (first reported here and on TakePart this past Saturday) has ranged from skepticism to derision

Here’s Joe Walston, Asia Executive Director for the Wildlife Conservation Society on why that’s misguided:

China destroyed a portion of its massive stockpile of confiscated ivory on Monday – a first for the country.

The action has left the international conservation community struggling with its own conscience. Whether to praise a monumental shift in approach to conservation by the world’s biggest consumer of the world’s wildlife or condemn the event as posture, devoid of substance and commitment? Before judging, it’s worth examining the situation in a little more detail.

It was probably no coincidence that China crushed 6.1 tonnes when, just two months earlier, the US crushed a slightly smaller amount. In the US’s case it was almost its entire stockpile, while in China’s case it is a fraction: 17 tonnes were confiscated between 2010 and 2013 alone. Which raises the obvious question, why only the six tonnes? If China was serious about destroying stocks, then why not burn it all? To some this is enough to dismiss the whole event out of hand.

But here’s the point. So much of what is written in foreign blogs and by us western conservationists fails to recognise the internal struggles in China on this issue.

The importance of the crush is not its direct impact on the market price of ivory (zero) or the safety of wild elephants in Africa tomorrow (negligible); its importance lies in it being the manifestation of a very real debate within the Chinese government on this issue.

To dismiss the event without regard for this silent but significant struggle is too big a risk to take. This crush happened in the face of considerable resistance in some quarters of the Chinese Government, while there are influential proponents of the crush who would like to see all ivory automatically destroyed after prosecution, with China agreeing not to buy future ivory from any legal sales.

The biggest fear is that crush contrarians within the Chinese government will use international criticism to prove their point: that China will just continue to be vilified whatever it does and it should therefore disregard the global movement against ivory. Similarly, government proponents of further, more influential actions against the ivory trade don’t necessarily need our support, but they would like us not to be opponents to their cause. Hence, the move needs to be welcomed if only to embolden those within the Chinese government who are pushing for more substantive action on this issue.

This is not to say we should be apologists or sycophantic supporters of half-measures. However, I for one welcome this event with a cautious but encouraging message of congratulations with hopes that China takes further steps towards shutting down this insidious trade.

January 6, 2014

Making Way for Urban Wildlife

A peregrine falcon over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in Brooklyn (Photo: MTA)

A few years ago in Baltimore County, Maryland, environmental staffers were reviewing a tree-planting proposal from a local citizens group. It called for five trees each of 13 different species, as if in an arboretum, on the grounds of an elementary school in a densely-populated neighborhood.

It seemed like a worthy plan, both for the volunteer effort and the intended environmental and beautification benefits. Then someone pointed out that there were hardly any oaks on the list, even though the 22 oak species native to the area are known to be wildlife-friendly. Local foresters, much less local wildlife, could barely recognize some of the species that were being proposed instead. As if to drive home the logical inconsistencies, both the school and the neighborhood were named after oak trees.

“Why are we doing this?” someone wondered.

That sort of epiphany has been happening a lot lately in metropolitan areas around the world, as people come to terms with both the dramatic increase in urbanized areas and the corresponding loss of wildlife. The portion of the planet characterized as urban is on track to triple from 2000 to 2030—that is, we are already almost halfway there. Meanwhile, 17 percent of the 800 or so North American bird species are in decline, and all 20 species on the Audubon Society’s list of “common birds in decline” have lost at least half their population since 1970.

Those kinds of stark numbers, repeated around the world, have made it disturbingly evident that it’s not enough for cities to plant a million trees, preach the gospel of backyard gardens, or build green roofs and smart streets. The trees, shrubs, and flowers in that ostensibly green infrastructure also need to benefit birds, butterflies, and other animals. They need to provide habitat for breeding, shelter, and food. Where possible, the habitat needs to be arranged in corridors where wildlife can safely travel.

Though it may be too soon to call it an urban wildlife movement, initiatives focused on urban biodiversity seem to be catching on. The U.S. Forest Service, which once laughed off the idea that anything urban could be wild,now supports a growing urban forest program. Urban ecology and urban wildlife programs are also proliferating on university campuses. There’s a “Nature of Cities” blog, launched in 2012. University of Virginia researchers recently announced the beginning of a Biophilic Cities Network devoted to integrating the natural world into urban life, with Singapore, Oslo, and Phoenix among the founding partners.

And in Baltimore County, officials now stipulate that canopy trees, rather than specimen, or ornamental, trees, must make up 80 percent of any planting on county land, and half of them need to be oaks. In an area where local nurseries hardly ever stocked oaks before, people sometimes balk, until the county’s natural resource manager, Don Outen, explains the logic of it: Research has shown that oaks benefit everything from caterpillars to songbirds. Even fish prosper, because the aquatic invertebrates they feed on favor oak leaves on stream bottoms. At that point, says Outen, the reaction tends to shift to, “Why haven’t we been doing this before?”

One reason is that researchers have barely begun to think about what wildlife already lives in the city, or how to encourage more of it. The importance of oaks in U.S. Mid-Atlantic states, for instance, came as news to most people in 2009, when Douglas Tallamy, a University of Delaware entomologist, published a ranking of trees and shrubs according to how many caterpillar species they harbor. (The Royal Horticultural Society has published a comparable list for Britain.) In contrast to oaks, which accommodate 537 species, says Tallamy, gingkoes, a standard street tree in many cities, host just three. “But there is this myth that a tree has to come from China to survive in cities,” he comments.

Tallamy likes to point out that a single pair of Carolina chickadees needs to bring 6,000-9,000 caterpillars to the nest to rear a clutch of a half-dozen nestlings. Black-capped chickadees probably need more. If you want the birds, he says, you need the caterpillars, and to get the caterpillars you need the right trees. “All plants are not created equal,” he says. “Natives are more likely to be beneficial than non-natives, but even among natives, there are differences.” For instance, though tulip trees are undoubtedly majestic, at 160 feet in height, they are stingy with wildlife, hosting just 21 caterpillar species.

At the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS), based at the University of California at San Barbara, researchers have begun to fill in a more detailed picture of what urban wildlife means. Because wildlife survey data often ends up in scattered locations, and recorded in different formats, they are developing a unified database, with species lists, abundance, and, in some cases, habitat types for urban wildlife in 156 global cities so far.

The preliminary evidence may be more encouraging than people tend to think, says Fresno State University ecologist Madhusudan Katti. Although pigeons, starlings, house sparrows, and barn swallows tend to turn up in cities worldwide, these four cosmopolitan species don’t necessarily indicate that urban wildlife has become entirely homogenized. Cities also capture about 20 percent of the world’s avian biodiversity, says Katti. That number may be skewed higher, he cautions, because younger cities tend to have more native birds. So it may be a transient effect. But understanding what’s happening before species start to disappear opens up the opportunity for interventions and urban design to retain them.

A new study in the journal Landscape and Urban Planning also looks at better ways of understanding urban wildlife and habitat in combination. The study uses birds as bio-indicators for other wildlife types because they are easier to count than shy, often nocturnal, mammals, and because they are more broadly familiar to the public. “They’re active during the day, they’re colorful, they sing,” says Susannah Lerman, a University of Massachusetts ornithologist and lead author of the new study. “So even if most people know nothing about wildlife, they know something about birds.”

The study proposes a marriage of i-Tree and eBird, two current methods for keeping track of the natural world. Designed by the U.S. Forest Service, i-Tree is software used by organizations around the world to record data on urban tree cover, from single trees to entire forests. Its counterpart, eBird, from Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is a checklist system enabling thousands of birders around the world to log their observations into a central database. The combination of the two enables researchers to assess not just which trees characterize a neighborhood, but how good they are as bird habitat, and which birds are using them.

To demonstrate the usefulness of this methodology, the study’s co-authors looked at 10 municipalities in the U.S. Northeast for which tree data happened to be available. They were aiming to show that the technology can work in the broadest possible range of communities. So they included municipalities from Moorestown, N.J., a Philadelphia bedroom community with a population of about 20,000, on up to New York City with 8.3 million. The ambition was to provide a quick tool for urban planners to assess how a proposed development would affect local wildlife, or which neighborhoods could benefit most from habitat improvements.

Accommodating wildlife in cities doesn’t necessarily require massive investment, says Lerman. You can bring in more birds, she says, just by breaking up endless lawns with the right kinds of shrubs, to create structure and variety. Mowing those lawns a little less often — not weekly but every two or three weeks — will increase the population of native bees and other pollinators. As for bird feeders, they don’t necessarily increase overall bird populations, but they do present one significant hazard: They can become “ecological traps,” luring birds to their deaths in a sort of cat smorgasbord. Just keeping cats indoors, says Lerman, could prevent the loss of billions of birds in the United States every year.

In Britain, adds Mark Goddard, of the University of Leeds, allotments, or community gardens, in urban areas make a major difference for pollinating insects, probably because they tend to feature fruit trees and bushes and because the weedy corners tend to be a little more insect-friendly than private gardens. Concern about dwindling pollinator species has also led to the recent proliferation of 60 wildflower meadows in British cities, modeled after the extensive meadows planted around the site of the 2012 London Olympics.

The new study by Lerman and her co-authors may also inadvertently have hit on one unlikely source of hope for urban wildlife: Civic pride and competitiveness. Their study looked at the relative wildlife-friendliness of 10 sample cities and boiled the differences down to a series of numbers indicating how well each city accommodated nine representative species. While the study scrupulously avoids an overall ranking of cities, it would be easy enough for local partisans to look at the numbers and make invidious comparisons. For instance, among the big cities, Philadelphia ranked first for biodiversity, followed by Washington, D.C. Boston lagged well behind. But it beat New York, and New York topped its Hudson River neighbor, Jersey City.

No formal “green city” competition exists in this country, at least not yet. But the “Britain in Bloom” contest, sponsored by the Royal Horticultural Society, increasingly focuses on pollinators and other environmental criteria. Along with a certain amount of municipal bombast, it manages to elicit a vast planting effort in British cities and towns year after year.

Maybe it’s a fantasy to think anything like that could happen in the United States. But just imagine: Right now, mayors do verbal jousting over meaningless contests between teams that are merely named for wildlife — Chicago Cubs versus St. Louis Cardinals, Anaheim Ducks versus San Jose Sharks, Atlanta Hawks versus Charlotte Bobcats, and so on, through an entire zoo’s worth of rivalries.

If those mayors had to go toe-to-toe over the real thing —”My city has more wildlife than yours,” “My city has more green space than yours,” “My city is a better place for bird, butterflies, and people to live”— that would be a competition worth watching.