Richard Conniff's Blog, page 61

December 16, 2013

What Goes Wrong When We Feed the Animals

One time in Panama, I was having dinner on the patio at a restaurant when the diners at a nearby table started to get rowdy. They were American soldiers, in uniform, and clearly drunk. The object of their delight was a large frog, which one of them was clutching in the meaty grip of his left hand. With his right hand, he was easing beer down the frog’s throat, eliciting waves of laughter from his pals.

One time in Panama, I was having dinner on the patio at a restaurant when the diners at a nearby table started to get rowdy. They were American soldiers, in uniform, and clearly drunk. The object of their delight was a large frog, which one of them was clutching in the meaty grip of his left hand. With his right hand, he was easing beer down the frog’s throat, eliciting waves of laughter from his pals.

I finished my dinner without appetite and slunk out, embarrassed by my species and a little ashamed not to have stuck up for the frog. He was having a very bad, almost certainly terminal, night. And I didn’t want to join him.

Feeding the animals seems to be one of our universal impulses, whether we do it maliciously, like those soldiers, or in the misguided belief that we are doing them a favor. Either way, the animals generally suffer.

For instance: Almost 6 million people will visit the Bahamas over the coming year, most of them in the next few months. Local tour operators will convince many of them that feeding the iguanas is a good way to get close to nature. Some operators will even bill it as “ecotourism.”

The problem, says Charles Knapp, an iguana specialist at Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium, is that the Northern Bahamian rock iguana is one of the world’s most endangered lizards, with a dwindling population of just 5,000 individuals in the wild. Its habitat, on a handful of small islands, or cays, is threatened by development, introduced species, logging, the pet trade, and occasional hunting for the dinner table. Then along come the tour operators, filling boats with tourists who visit and scatter food on all but the two cays that are too difficult for a landing.

When Knapp first started studying the iguanas 20 years ago, they were skittish and rarely seen on beaches, preferring the island interior. Then, after the tour business got started about five years ago, he landed on a remote beach one day to find iguanas gathering all around him. Humans were suddenly a source of food rather than something to be feared, leaving the iguanas vulnerable “to be taken and smuggled for the pet trade or to be eaten,” Knapp says. A couple of tourists from the Midwest visiting by sailboat must have felt like 17th-century sailors picking up dodoes. They threw some on the grill, says Knapp, and posted the photos on Facebook, leading almost immediately to their arrest. The fine was nominal, and they soon went free.

Feeding causes other problems that may not be obvious to well-meaning visitors, according to a new study coauthored by Knapp in the journal Conservation Physiology. The tour operators started out feeding bread to the iguanas, then switched to grapes, after conservationists suggested they should at least try to approximate the iguanas’ normal diet of leaves, flowers, and fruits.

But the study shows that tourist-fed animals display a range of nutritional deviations from their wild counterparts, including elevated glucose and deficient potassium levels, reflecting a diet dominated by grapes. Some also have higher cholesterol levels, probably because tourists sometimes toss them meat. It’s as if they have switched overnight from the Pleistocene to the modern Western diet, with metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and perhaps even gout hovering eagerly in the wings.

The study found that bringing together the normally territorial iguanas on the same beach does not elevate their stress levels. But being in close proximity to one another means that 100 percent of the tourist-fed animals now carry internal parasites. It also makes the entire population more vulnerable to an epidemic.

The realistic solution, says Knapp, isn’t to push for a ban on the iguana-feeding tours. “We wouldn’t get anywhere with the government because the islands depend on tourism,” and the iguana tours generate jobs and revenue. “And we wouldn’t be able to enforce it because many of the islands where the iguanas live are too remote.”

But if government officials see the iguana population as a valuable resource, he says, they will act to ensure its continued survival. That could mean getting tour operators to switch to the sort of nutritionally balanced food pellets zoos use for their lizard populations. It should also mean keeping some of the islands free from feeding tours, so there is at least a baseline for what a natural iguana population should look like.

Meanwhile, for tourists everywhere, the answer is pretty simple: Don’t feed the animals. Whatever the tour operator says, and whether the animals are iguanas, stingrays, sharks, dolphins, or any of dozens of other animals willing to grovel for a handout, call this thought to mind: The damage may take a little longer to show up, but you will be doing much the same thing as the soldiers in Panama pouring beer down a frog’s throat.

The Passing of a Great Editor

Don Moser, the editor of Smithsonian Magazine from 1980 to 2001, died Thursday at the age of 81.

Don Moser, the editor of Smithsonian Magazine from 1980 to 2001, died Thursday at the age of 81.

A lot of editors these days think a writer should jump through hoops for an assignment. Don trusted me to write what interested me, in the belief that it would also interest his readers.

In the mid-1990s, I was writing a lot of insect stories, and he once protested to Jim Doherty, my editor: “Can’t you get him to write about something bigger than a breadbox?” (More recently, the editor of a general interest magazine told me that writing about ANY kind of wildlife is uninteresting and “not cool.”) But Don made the assignment. It won the National Magazine and led to my book Spineless Wonders.

Don Moser was a prince.

Here’s a piece senior editor Jack Wylie wrote when Don retired from the magazine:

Don Moser is putting down his pencil and picking up a fly rod. After taking over from the founding editor, Edward K. Thompson, in 1980, Don ran the magazine in the independent tradition of H. L. Mencken at the American Mercury and Harold Ross at the New Yorker: his subjective judgment, and his alone, determined what would run. No committees, no voting. Judging by the results—two million subscribers, a National Magazine Award and a stack of other prizes—it was a formula for success.

Before coming to Smithsonian, Don acquired the kind of wide-ranging experience a good magazine editor needs. He attended Heidelberg College for two years and then had to drop out for financial reasons. While waiting to be drafted, he worked for the U.S. Forest Service as a fire lookout in northern Idaho. He describes his military career as two years of “pushing a pencil at Fort Benning.” He then attended Ohio University on the G.I. Bill. On summer vacations he worked as a seasonal ranger in Olympic and Grand Teton National Parks. “My greatest achievement during those ranger days was saving a drowning moose,” he says.

Even greater achievements were soon to come. After graduating from Ohio University, Don got a fellowship to study writing at Stanford with novelist Wallace Stegner. He showed Stegner his senior honors project from Ohio, a book about Olympic National Park that he’d written and used his own photographs to illustrate. The Sierra Club had just published a big Ansel Adams book and was looking for a new project. Stegner told David Brower, the Sierra Club’s first executive director, “I’ve got this student named Don Moser who has something you should publish.” The Peninsula came out in 1962.

A Fulbright Scholarship took Don to the University of Sydney in Australia. Home again, he was hired by the old Life magazine as a military affairs reporter. At that magazine, he saw the extremes life has to offer. He became West Coast bureau chief in Los Angeles, covering Hollywood, the Good Friday earthquake in Alaska and the Watts riot. He then went on to Hong Kong as Far East bureau chief, spending much of his time in Saigon during the Vietnam War. Some of his writing from the war zone appears in Reporting Vietnam: American Journalism 1959-1969, published by the Library of America. In one of those pieces, he describes spending time with eight village leaders, marked for death by the Vietcong. All but one (who thought it safer to move from place to place) spent their nights huddled in the railroad station, the only concrete building in the village. Not long after Don was there, most of the men were indeed killed.

During a recent interview, Don’s wife, Penny, said: “And don’t forget he was almost killed twice.” Don responded with a dismissive wave of his hand: “Oh, I was scared stiff a few times, but so was everyone else.”

When Life folded, he turned to freelance writing. His assignments for this magazine included pieces on the Army Corps of Engineers and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. He wrote four of his five books during those years, including Central American Jungles; China, Burma, India and Snake River Country. He came in out of the cold in 1977 to become an executive editor at Smithsonian. Within a few years, Ed Thompson retired and Don became the new editor.

The man has passionate interests. He is an expert birder. He uses an eight-inch telescope to search for what are known as “deep-sky” objects—galaxies, nebulas and star clusters. He fishes for trout in Idaho and bonefish in Belize, releasing every one he catches. For years, he and Penny took in dogs that were seriously ill or seriously injured. Right now they live with three yappy terriers. One of them, Harvey, is so disabled that Don pulls him around the neighborhood in a red wagon.

As editor, Don Moser pushed for higher-quality writing, better storytelling, writers who know how to “let the camera run.” In choosing what ideas to commission, the aim always was to surprise the readers: present them with a story they had seen nowhere else and were unlikely to see in the future. His take on the quality of the material published in Smithsonian occupied a spectrum that ran from “terrific” down to “this won’t embarrass us.”

Don loved his job. “At Smithsonian, you get to cover everything from Motown to Mars,” he said. “You have terrific writers and photographers to work with. And you have wonderful readers, who tend to think of themselves as part of the family, which indeed they are. They encourage us, they correct us when we’re wrong and they never fail to give us advice. Of the thousands of letters to the editor that I’ve read over the years—and I’ve read them all—one stands out for its pithiness. It reads, in its entirety, ‘Dear Editor: Support the law of gravity.’”

He was unflappable. Late in the process of closing an issue, you could walk into his office and tell him that the full-page picture opening an article could not be used for some reason just discovered. There’d be no histrionics, no calling for someone’s head. Instead, he’d say calmly, in a conversational tone, “OK, let’s see what we can use instead.”

All was not sweetness and light, of course. The staff dreaded what we called the “fish eye” (or what one former copy chief dubbed the “hairy eyeball”). An editor would be in Don’s office explaining an idea for what he or she considered a terrific story. Don would simply stare at the editor, expressionless, until he or she would start stumbling over words and finally say, “No, huh?” There was another Moser response I dreaded even more, perhaps because I experienced it so often. Don would silently look over a writer’s story proposal and then say: “This is really interesting. And this is all I want to know about it.”

Sometimes, though, even the fish eye would soften into approval. Years ago I was invited to accompany a group of scientists on an expedition to study a total solar eclipse. We would be in a jet, racing with the moon’s shadow over the Indian Ocean. Don wanted to know if any discoveries were likely. I said no. Was this eclipse any different from any other? No. Still more questions, and more negative answers. It was clear I was not going anywhere. I turned to leave the room, and only then did Don say: “You better go.”

Now he’s going. The Don Moser era is over. It has been a privilege and a pleasure to work for this rare and gentle man. We’ll miss him more than words can say.

December 14, 2013

Cape Buffalo Fear: Lion Takes Flight

Of all the animals in the African bush, cape buffalo are the most frightening. Well, o.k., getting between a panicky hippo and the water is up there, too. Or being too close to the water when a crocodile makes its lunge. Or, yeah, yeah, when a black mamba stands up and repeatedly bites before you can say, “What’s that?”

But Cape Buffalo seem to be everywhere, and they have a special malevolence I find unnerving. I think this lion probably feels the same way. (But also see the comments on my previous posting about this particular fear of mine.)

December 13, 2013

Is There Room on the Farm for Wildlife?

It’s been a long, strange ride for the organic food movement over the last two decades, as it has moved from the health food co-op fringe into the Walmart mainstream. About one percent of all farmland—91 million acres worldwide—is now dedicated to organic methods, and that number is rapidly increasing. But organic farming has also attracted skepticism on a variety of counts, including disputed health claims, lower productivity, and a misleading image. Big Food companies like Cargill, Kellogg, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Perdue, and Campbell Soup have all piled into the organic market. That means Big Food now has a USDA-certified counterpart in Big Organic.

Now a new study from Britain suggests that organic farms may not be all that great for wildlife, either. The press release from the University of Southampton puts it this way: “Threatened farmland birds are likely to survive the winter better on conventional farms with specially designed wildlife habitats than on organic farms without.” To which you may say, “Well, duh.” But a lot of us automatically assume that going organic by itself is the best thing we can do not just for our health, but for the natural world. Chaffinches, skylarks, yellowhammers and lapwings all showed up in greater numbers than on the organic farms, according to the study by Dominic Harrison, then a graduate student in environmental science.

That kind of improvement could be a big deal, because agricultural intensification—meaning farms with more tractors, more herbicides, and planted fields running right up to the sides of roads—has caused farmland bird populations to crash in much of the developed world. British farm bird populations are down by half just over the past 40 years. Some researchers have called it the “Second Silent Spring,” echoing Rachel Carson’s 1962 description of a Silent Spring caused by the overuse of pesticides.

“But this time is probably worse,” says Harrison, who’s now a self-employed environmental consultant, “because it’s not an on-off switch that you can fix overnight. Before, with the pesticides, you could just stop using those chemicals. But with agricultural intensification, you can’t just flip that switch. It’s just too much of a change for farmers” and for the food supply.

The key difference that makes the conventional farms better, according to Harrison, is an innovative, market-driven scheme called “Conservation Grade.” Like organic farming in the early days, it’s a niche program with only 101 British farms and 100,000 acres under contract. The key stipulation to which farmers agree is that they will set aside 10 percent of their land for wildlife, and follow a detailed protocol for pollen and nectar habitat, bird food crops, and other habitat types. Otherwise, the farms are free to use certain fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides (no to organophosphate, but yes, at least for now, to the controversial neonicotinoid insecticides implicated by some research in the decline of bees and other pollinator species.) For their trouble, Conservation Grade-certified farmers sell their crops at a premium through food companies that license the “Conservation Grade” or “Fair to Nature” label.

Some caveats: This approach to “nature friendly farming” is largely the work of what is technically another Big Food company. Jordans, the main backer of Conservation Grade, ranks fourth in the British cereal market, just behind Kelloggs. But Conservation Grade has gone through almost 20 years of testing, and a previous study has shown a 41 percent increase in bird abundance over three years compared with conventional farms.

So what makes Conservation Grade better for birds than organic farms? It’s mainly that being organic does not require that dedicated 10 percent of land in wildlife habitat. Where previous studies have shown that organic farms increase bird numbers, says Harrison, it’s been an incidental result of having hedgerows and trees “rather than the specific prescriptions and theology of the organic farming.” That is, there’s nothing inherently wrong with organic farming. It’s just that it doesn’t do anything specific for wildlife, and on organic farms that behave like big businesses, they are likely to do even less.

American farmers have what may sound like a counterpart to the Conservation Grade scheme—and on a much larger scale. The U.S. Department of Agriculture pays farmers to set aside about 30 million acres of land nationwide under its “Conservation Reserve Program.” But that program has been shrinking in recent years, with many farmers lured away by higher corn prices. Congress is also expected to reduce the amount of eligible land to just 25 million acres. The Conservation Reserve Program also does not focus exclusively on wildlife, and it does not give farmers any bragging points, or any marketplace premium, when it comes time to sell the crop.

That sounds like something worth changing. People want to hear birds singing in their parks and in their yards, and they are noticing that the silence has been getting a little ominous. The bottom line on Harrison’s study of Conservation Grade seems to be that, if you can persuade farmers to make large-scale habitat improvements, you’ll get large-scale wildlife results.

But one way or another, whether through our taxes or at the supermarket, the rest of us are going to have to pay the farmers to do that.

December 10, 2013

Radio: An Ivory Trade Story from Small-Town New England

This is an interview I just did with NPR’s Colin McEnroe, about what China can learn about the ivory trade from small town Connecticut. It’s based on previous pieces I have written here and for TakePart.

It runs 10 minutes, starting at 38:00 http://wnpr.org/post/tuesday-tumble-eddie-perez-rent-trumbull-snowy-owls-tarmacs-ivory-trade-ct … …

December 9, 2013

The Squirrels in Our Parks Are A Rewilding Success Story

An urban comeback story (Photo: http://easterngraysquirrel.deviantart.com/)

There’s hardly any more common wildlife in cities east of the Mississippi River than the gray squirrel, racing like greased smoke through the tree branches, or foraging, fat and wily, beneath every bird feeder. Watching them can at times induce laugh-out-loud delight—or push us to the brink of madness. (For laughter and madness both, check out any number of videos of failed “squirrel-proof” bird feeders.) On balance, I think most people would agree that city life without squirrels would be a far duller thing.

Until relatively recently, though, a life without squirrels was normal in most American cities. The spectacle of a squirrel in the city was so unusual for much of the 19th century, according to an article just published in the Journal of American History, that when a pet squirrel got loose near New York’s city hall in 1856, hundreds of people gathered to watch—and ridicule—the hapless attempts to recapture it. Squirrels were known not as city dwellers but as shy inhabitants of thick forests and as occasional agricultural pests.

Etienne Benson’s account of how that changed comes at a useful time. Today’s nascent urban wildlife movement is trying to figure out how to bring more birds, butterflies, and other species into the city—and beyond that, how to keep any wildlife alive in an increasingly urbanized world. So how did the squirrel become part of our daily lives even as other species, such as the passenger pigeon and the ivory-billed woodpecker, were being driven to extinction?

“In order to end up with squirrels in the middle of cities,” writes Benson, a University of Pennsylvania historian, “you had to transform the urban landscape by planting trees and building parks and changing the way that people behave. People had to stop shooting squirrels and start feeding them.”

Early settlers had exterminated the gray squirrels, sometimes encouraged by bounties. But a few wildlife lovers reintroduced them, first in Philadelphia’s Franklin Square in 1847 and then later in Boston and New Haven, Conn. Supporters provided nest boxes and food, with the idea that wildlife in the city would turn public squares into “truly delightful resorts” and bring pleasure “to the increasing multitudes.”

That effort petered out. But in the decades after the Civil War, the landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted pioneered the urban park movement. He designed landscape-scale parks that threaded through cities, along parkways and waterways, and out into rural areas. (Among his creations: Central Park in Manhattan, Prospect Parks in Brooklyn and Newark, N.J., and a ring of parks around Milwaukee, Wis.)

That movement was about the importance of having things of beauty in the heart of the city, says Benson. “But it was also part of a much broader ideology that says that nature in the city is essential to maintaining people’s health and sanity, and to providing leisure opportunities for workers who cannot travel outside the city.”

Deliberate reintroductions of squirrels and the chance for different populations to connect on these new greenways helped the squirrels hang on this time. Squirrels soon adapted to the new habitat, learning to nest in attics when possible (inducing more home-owner madness) and to use telephone and electric wires as highways safe from city cats.

For squirrel advocates, the idea wasn’t just to benefit the animals but also to change people’s attitudes toward wildlife. The popular nature writer Ernest Thompson Seton urged the introduction of “missionary squirrels” in cities around the nation to cure boys of their cruel tendency to abuse animals. “Everyone who feeds squirrels will become their friend, and this means that before many months the young community will have been turned into squirrel protectors,” wrote Seton.

The 19th-century squirrel movement had its drawbacks. The same urge to enliven city habitats caused some supporters to introduce gray squirrels in British parks, where they drove out the native red squirrels. (The “American tree rat” is still the source of considerable anti-American resentment there.) In this country, the paternalistic program of feeding squirrels, for our own amusement more than for their benefit, sometimes turned them into beggars and pests. In some cities, protecting squirrels also became an occasion for ethnic prejudice, with hunting for the dinner pot by Italian immigrants singled out as a particular threat to squirrels.

As it happens, my own great-grandfather, Bartolomeo Badaracco, was a hunter in the northern Bronx when a prominent wildlife advocate there was denouncing the threat from “stray dogs, cats, poachers, and other vermin.” The squirrel proponents were among the most powerful men in the country, and they didn’t stop at categorizing Italians as vermin. They also planned the route of the new Bronx River Parkway with the deliberate intent of displacing Italian communities. Bart Badaracco lost his house on the river as a result.

For me, one useful lesson from the squirrel story is the need to not lapse into the same hateful thinking when talking about people who still hunt bushmeat or graze livestock in national parks abroad. (Hateful thinking doesn’t change anything, by the way. My great-grandfather simply built a new house across the street—and kept hunting.) The larger lesson, though, is that wildlife restorations can work, even in crowded cities with seemingly intractable environmental problems.

People reacted to the appearance of squirrels in the city, says Benson, with the same giddy excitement and delight that marked the recent reappearance of peregrine falcons and red-tailed hawks amid Manhattan’s skyscrapers. (One red-tail now lives on a window ledge above Fifth Avenue. Pale Male is a New York hero, and if hawks can make it there, well, you know the song.) Moreover, we can repeat that experience with a thousand—even ten thousand—other species.

If the idea of re-wilding the city seems like too big a challenge, or the daily work to get there becomes too discouraging, just glance out the window at the squirrels skittering round your own backyard. That’s the kind of difference a few determined people can make.

December 8, 2013

River Thames: From Fermenting Sewer to Porpoise Playground

One of five porpoises spotted in London on Friday (Photo Marine 2 Patrol Boat)

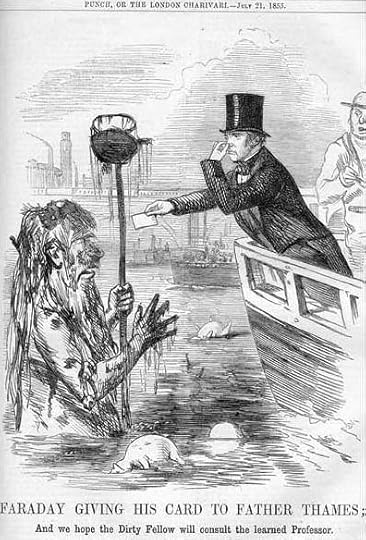

The Thames in London has been a dead river since at least the 1850s, when the chemist and physicist Michael Faraday described it as a “fermenting sewer,” from which the “feculence rose up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface.” But the modern effort to clean it up got started in the 1960s, and like a lot of environmental efforts from that era, it has paid off.

The Thames is not only far more pleasant these days for people who live around it, but this past Friday those people were treated to the spectacle of five harbor porpoises gamboling through the middle of central London. Here’s an account from The Guardian:

A pod of five harbour porpoise has been sighted in the River Thames.

At around 9.30am, the Marine Policing Unit was alerted to the sighting of a dolphin near Tower Bridge. They reported no further sightings until 10.40am, when they confirmed their boat Marine 2 was “following a pod of about five harbour porpoises in the Lambeth area of the river.”

Stephen Mowat, a marine conservationist for ZSL [the Zoological Society of London] said it was uncommon to see so many so far up the Thames.

“With the condition of the Thames improving we are getting more and more sightings of marine mammals such as porpoise and seals,” he said.

Mowat said one of the reasons that the porpoise may be so far up the river was because of the storm surge.“They follow prey fish up the river so with the high tides to get more fish further up the Thames. Because central London is a more heavily populated area more sightings will be reported.”

He said it would not pose a threat to the porpoise that the Thames barrier was closed. “They should be fine, they can find their way up river and go back down again. As soon as they’ve had their fill of fish they will find their way back out.”

Faraday would be pleased. Here’s a cartoon that appeared after he wrote a letter in July 1855 describing the filth of the Thames then. Note that the only animals in the river were carcasses:

December 7, 2013

Becoming a Mom at 62

Wisdom and mate: one more time to the nest

As a human, even the thought of becoming a dad at that age fills me with terror. But it’s different for a Laysan albatross named Wisdom and her mate. Here’s the news account (and some opinion) from US Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Region’s Amanda Fortin:

They say you are only as old as you feel and it seems that Wisdom, the world’s oldest banded bird, isn’t feeling her 62 years. More impressive than the age of this now famous Laysan albatross is that she is a new mom. Wisdom and her mate were spotted on November 28 by a Fish and Wildlife Service biologist building up the nest around a new egg and preparing for the first incubation shift.

This isn’t the first time these two have readied their nest. Laysan albatrosses mate for life and Wisdom has raised between 30 to 35 chicks since being banded in 1956 at an estimated age of 5. Laying only one egg per year, a breeding albatross will spend a tiring 365 days incubating and raising a chick. Most albatross parents then take the following year off (and who could blame them?) but not Wisdom.

Nesting consecutively since 2008, Wisdom’s continued contribution to the fragile albatross population is remarkable and important. Her health and dedication have led to the birth of other healthy offspring which will help recover albatross populations on Laysan and other islands.

Albatross, particularly as chicks, face many threats. Chicks can’t fly away from invasive predators like rats or escape weather-related risks like flooding and hot spells. If they make it to adulthood, they face different threats. Manmade problems like marine debris and pollution are dangers faced by all albatross. Although the population of Laysan albatross has strengthened to roughly 2.5 million, 19 out of the 22 species of albatross are threatened or endangered.

Mainstream naysayers and conventional “wisdom” may say it is too late for us to make a difference for these birds. It is easy to believe that the changing climate and spread of pollution are too immense for the efforts of one person to be felt. Maybe this long-living avian mom is here to offer a new kind of “wisdom” by teaching us the power of one.

Imagine if we all took a cue from Wisdom and used our seemingly small steps to combat climate change or contribute to conservation? What begins as a single idea can hatch, and fledge into stronger, more numerous acts that take flight and make a dramatic difference. This spirited albatross has inspired and amused people around the globe for decades. Hopefully, she has shared some Wisdom too.

A Laysan albatross on the wing off Kilauea Lighthouse on Kauai, Hawaii (Photo: Dick Daniels)

When a Python Has You Over For Dinner

Your date for dinner?

Let’s say you’ve just been swallowed headfirst by a 15-foot-long Burmese python. The good news: Your worries are over. They’ve been over ever since those awkward getting-acquainted minutes when the snake was hanging on to you with its backward-raked fangs while squeezing the teeny-weeniest last bit of life from your lungs. Now you’re just a very large piece of meat, somewhat tenderized.

The snake, on the other hand, is revving up like a mothballed factory suddenly called back into full production. Over the next few hours, its heart will race up to 50 or 55 beats a minute, from 15 beats a minute during the sluggish month or so it has been lying around waiting for dinner to turn up. The amount of blood pushed out by each beat will increase five-fold. Heart, liver, kidneys, and small intestine will double in size, or more, to tackle the work at hand.

The 40-fold surge in the python’s metabolism is essential to digest the huge lump in its gut over the next five or six days, and it can’t stop until it’s done, says Stephen Secor, co-author on a study, published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, about how the python’s extraordinary digestive powers work. It’s a study that could have far-reaching implications for our understanding of how organs work and for the treatment of diseases like diabetes and heart failure.

But back to the original scenario, in which you become lunch. You probably saw the photograph that recently went viral of the python that had supposedly gobbled down a sleeping drunk beside a liquor store in India? A hoax, says Secor, who is a snake physiologist at the University of Alabama. The species in the photo lives in Indonesia, not India, and that huge mass of food swelling its gut was a deer, not a person.The truth is that even very big snakes almost never eat adult humans, says Secor. Though a child may occasionally make this unfortunate trip, the span of adult shoulders is generally just a little more than even the largest snakes can swallow.

Loafing around after dinner

But the python’s ability to perform digestive magic is nonetheless real. “They mostly eat smaller mammals and birds, says Secor. “But porcupines, pangolins—things you think ‘That’s a really tough meal’—they still eat ‘em.” The Burmese pythons that have invaded the Everglades will even take on alligators, he adds, “and they can digest them as easily as they digest a rat.”

Among the new study’s other results, Secor and his co-authors found that the arrival of a meal in the gut elicits “a rapid and massive” response from the snake’s digestive tract. Thousands of genes light up and go to work. One of Secor’s previous studies showed that even the number and variety of bacterial species in the gut seems to double from what’s present in a resting gut.

The new python paper, and another study published at the same time about the king cobra’s extraordinarily toxic venom, are the first ever to sequence a complete snake genome. The authors of the two studies collaborated, lining up parts of both snake genomes against each other and against the genomes of other vertebrates, to figure out how each snake acquired its extreme abilities.

The basic shift away from other vertebrates, and particularly from lizards, to “what makes a snake a snake, especially a snake that eats big things,” probably took place 100 to 150 million years ago, according to Todd Castoe, lead author on the python study and a biologist at The University of Texas at Arlington. Then, beginning 100 million years ago, a dramatic series of adaptations involving more than 500 genes rapidly changed python and cobra into their distinct forms.

Current thinking says big differences like this generally develop as a product of gene expression. That is, changes in when particular genes get turned on or off can produce major differences in form and function. But the snake studies call that idea into question. Both studies found far more extensive changes, involving not just the timing of gene expression, but the structure of the genome itself and also the proteins it produces. It was a major and rapid evolutionary reorganization.

Does that mean snakes will have the evolutionary nimbleness to adapt to rapid changes in the modern world? Not necessarily, Harvard evolutionary biologist Scott Edwards commented this week in New Scientist magazine. Even the rapid changes described in the two studies accumulated over millions of years. Whether snakes are “labile enough to resist all the challenges of habitat loss and climate change is unclear. It’s a different timescale.”

Secor believes, however, that the python study will help medical researchers understand the biochemistry of how organs function. That could eventually lead to treatments, he says, for heart disease, ulcers, intestinal malabsorption, Crohn’s disease, diabetes, and other conditions.

Experiments have already shown, for instance, that blood plasma from a fasting python has no effect on organ function in mammal species. But substitute blood plasma from a python that is revved up to digest its prey, and you can get human pancreas cells to increase insulin output by more than 20-fold.

With diabetes now afflicting about 285 million people worldwide—and rapidly rising—the python could turn out, against all odds, to be a lifesaver.

December 5, 2013

Bird Schools Fox on Dinosaur Ancestry

Not long ago, I posted pictures of an eagle taking on a Saiga deer. This time it’s an Australian wedge tailed eagle carrying off a fox. These birds also have a reputation for attacking hang-gliders and paragliders.

Check out the legs on this female taking off from nest:

(Photo: http://www.flagstaffotos.com.au/ )

It kind of makes me think of Rodan, “the giant monster of the sky,” in the 1956 science fiction movie. Rodan was a flying dinosaur that could destroy everything in its path with beak, talon, or sonic boom.

Or, uh, wait, I’m a wildlife writer. What I mean to say is, “Gee, what a beautiful bird.”