Richard Conniff's Blog, page 60

December 23, 2013

A Snake That Ate Dinosaurs

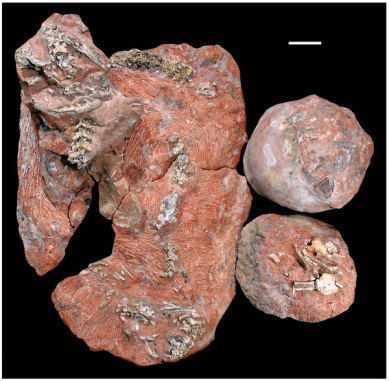

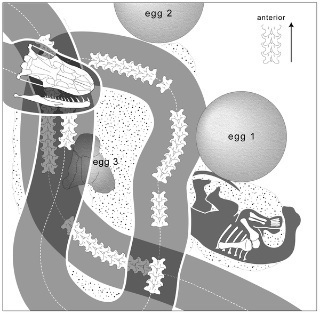

The photo of the actual fossil (on the left) is a little inscrutable for non-paleontologists. So the picture above diagrams the action.

This is a pretty exciting fossil, found near Dholi Dungri in Gujarat, western India. It’s not new, but I just happened to come across it while browsing around the web. Here’s the authors’ account from their 2010 article in PLOS Biology:

Snakes first appear in the fossil record towards the end of the dinosaur era, approximately 98 million years ago. Snake fossils from that time are fragmentary, usually consisting of parts of the backbone. Relatively complete snake fossils preserving skulls and occasionally hindlimbs are quite rare and have only been found in marine sediments in Afro-Arabia and Europe or in terrestrial sediments in South America. Early snake phylogeny remains controversial, in part because of the paucity of early fossils.

We describe a new 3.5 meter-long snake from the Late Cretaceous of western India that is preserved in an extraordinary setting—within a sauropod dinosaur nest, coiled around an egg and adjacent the remains of a ca. 0.5 meter-long hatchling.

Other snake-egg associations at the same site suggest that the new snake frequented nesting grounds and preyed on hatchling sauropods. We named this new snake Sanajeh indicus because of its provenance and its somewhat limited oral gape. Sanajeh broadens the geographical distribution of early snakes and helps resolve their phylogenetic affinities. We conclude that large body size and jaw mobility afforded some early snakes a greater diversity of prey items than previously suspected.

So was the fossil just an accidental association? Or were snakes really raiding dinosaur nests back then?

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that the snake-dinosaur association preserved at Dholi Dungri was the result of preservation of organisms “caught in the act” rather than a postmortem accumulation of independently transported elements. First, the pose of the snake with its skull resting atop a coil encircling a crushed egg is not likely to have resulted from the transport of two unassociated remains. Second, the high degree of articulation of the snake, hatchling, and crushed egg, as well as the excellent preservation of delicate cranial elements and intact, relatively undeformed eggs rule out substantial transport and are indicative of relatively rapid and deep burial.

December 21, 2013

Second Chance for Flying Fish

Pelican and the one that got away (Photo: ???)

Kingfisher and the one that didn’t, in Worcestershire, England (Photo: Peter Downing)

The Mystery of that Stonehengy Rainforest Structure? Solved

A sampling of the mystery structures on tree trunks and other surfaces (Photos: Lary Reeves & Ariel Zambelich/WIRED)

You remember seeing these bizarre silken rainforest structures reported earlier this year? Each one is a sort of tower inside a web-fenced circular corral, and the result has a sort of Stonehenge-cum-Seattle Space Needle look. But tiny.

The graduate student who first posted photos last summer had no idea what they might be, and his request for help went viral.

Now there’s an answer, from researchers in Peru’s Tambopata Reserve. Here’s part of the report from Nadia Drake at Wired:

For six days, Reeves, Torres, and Hill watched the tiny towers, all the while considering different hypotheses.

They debated whether the structures could have been made by mites (not too likely, given how small the mites are), or if the fluffy, fine silk pointed toward a spider (yes). They questioned whether the sacs were eggs at all. Maybe, Reeves suggested, they were looking at a structure called a spermatophore — a type of gift containing sperm and nutrients that some insects and spiders exchange during mating. Could these structures be the work of the huntsman spiders the team kept seeing on tree trunks? It was hard to say. Every time a hypothesis began to gain traction, another observation would swoop it and kill it.

The young spider that emerged from the tower (Photo: Jeff Cremer/PeruNature.com)

Finally, on Dec. 16 as the scientists were preparing to leave the rainforest without an answer, two of the eggs hatched and Torres saw two tiny spiderlings running around the base of the structures. “We were excited about that but still hesitant,” Torres said, noting that most of their hypotheses so far had fallen through.

But the next day, a third egg hatched and produced another small spider. “That really confirmed it for me,” Torres said. “Anything we saw crawling in there had to have come out of the structure.”

Now, even though the team is sure that they’re looking at some kind of intricate spider nursery, they’re still confused. For starters, a spider laying only one egg in a particular spot is exceptionally rare. “Traditionally, the female will lay a bunch of eggs, wrap it up very well, sit, and protect it,” Torres said. “This is kind of the opposite.”

And the amount of parental investment in the structures is immense, considering the single spiderling inside.

Then there’s the question of the spider’s identity. It could be a jumping spider – the spiderlings’ body shape resembles the Salticidae family, and they have two giant eyes, resembling a jumping spider’s adorable head. But the rest of their eyes aren’t quite in the right place.

It’s also possible the structures could be the work of a spider with a dark side. Near some of the clusters, the team saw several spiders that camouflage their nests with the corpses of their prey, such as ants and smaller spiders. Could the small spiderlings grow into these crazy corpse spiders? We’ll have to wait and see, as Torres and his colleagues continue their investigation.

My hunch is that the corral-like fencing is a defensive structure, to keep off ants or other species that might menace the young spider. On the other hand, the biggest threat probably comes from parasitic wasps, and it’s not clear how this structure would be much help against them.

And in other spider news: On top of yesterday’s report that the diabolical looking vampire squid is actually just a scavenger, now comes a study saying that spiders, those ultimate sit-and-wait predators, may actually get a quarter of their diet, like Birkentstock-wearing health food coop holisitic medicine enthusiasts, by eating pollen.

December 20, 2013

A Plague of Snakes: But They’re the Victims

Somewhere in the back of our minds, we all worry about the sort of nightmare pandemic envisioned in films like Contagion or The Hot Zone, with some horrific new disease sweeping across the continents and mowing down human victims like so much hay. But wildlife biologists worry more than most, because they’ve already seen emerging diseases devastate two major animal groups.

Now it seems to be happening yet again, while the two other wildlife pandemics are still raging unresolved: Over the past two decades, the chytrid fungus has contributed to the extinction of perhaps 100 amphibian species—including some of the most colorful, charismatic frogs in the world—with many more extinctions now being predicted. White nose syndrome, another fungal disease, first discovered in 2006, has already killed off 6 to 7 million North American bats and now threatens some species with extinction. No reliable remedy is known for either disease.

The victims of what seems to be a new epidemic are snakes, and they may prove even harder to save, because they are widely unpopular and because populations in many areas tend to be small and scattered. Wildlife biologists first noticed the new pathogen in 2006, among New Hampshire’s only surviving population of the timber rattlesnake.

The first victim turned up dead in early June, from a severe fungal infection in the mouth. Other victims displayed skin lesions around the head and, in one case, a severely swollen eye. Within a year, half the population was dead.

Similar cases have appeared since then in snakes of various species in the Eastern and Midwestern United States. But because they live in the dirt, snakes carry a variety of fungi, and separating the pathogen out from among the background fungi has proved challenging, according to David Blehert, head of diagnostic microbiology at the U.S. National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, Wisc. Then, early this year, new molecular techniques made it possible to identify the likely culprit for what’s being called “Snake Fungal Disease.” Researchers then went back and determined that the suspected pathogen was present in virtually every known case of the disease to date.

So far the disease has turned up in nine states: Illinois, Florida, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Tennessee, and Wisconsin. It has caused sickness and death in seven species: Northern water snake, eastern racer, rat snake, timber rattlesnake, massasauga, pygmy rattlesnake, and milk snake.

Federal and state officials are beginning work on a new grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to survey snake populations for presence of Snake Fungal Disease. The aim is to avoid a repeat of the mistakes made in the early 1990s with chytrid fungus in amphibians. Because of inadequate monitoring, researchers failed to recognize that pathogen until it had spread widely and caused some species to become extinct.

No one knows yet where the new pathogen came from. It’s possible it was introduced from the pet trade or another source. Blehert thinks it’s more likely to be a fungus that was already present in the population, from which a more virulent strain has emerged, or a strain that does more damage because of changing weather conditions. The outbreak in New Hampshire occurred during the state’s wettest weather in 114 years.

The impact on snakes could be severe, Blehert warns, “because many of these threatened snake populations are already heavily fragmented and isolated from one another.” Amphibians may be somewhat more resilient in the face of chytrid fungus because they live in larger populations and lay thousands of eggs. But snakes tend to have much more limited reproductive potential. Timber rattlesnakes, for instance, give birth to live young, not eggs, and the offspring don’t reach sexual maturity for nine years. If fungal deaths pile up during those nine years, a population, or a species, could easily crash.

For now, the New Hampshire rattlesnake population seems to be hanging on. But researchers there warn that the combination of habitat fragmentation, loss of genetic diversity, climate change, and now an emerging disease could send some species spiraling into an “extinction vortex.”

A Vampire’s Embarrassing Secret

Vampire squid with yellow tentacle

What do you do when you are one of the scariest looking creatures on the planet, so scary sober-minded scientists named you Vampyroteuthis infernalis, the vampire squid from hell? You kill, of course. And kill, and kill, and kill.

But now it turns out that the vampire squid does no such thing. This very entertaining article from R.R. Helm at Deep Sea News reports that they are vegetarians.

But it’s worse than that: They are actually scavengers, detritivores, the natural world’s equivalent of dumpster-divers. Here’s Helm:

Vampire squid–with cloudy blue eyes, a blood red body, and barbed arms– may be the deep sea’s most frightening creature, but according to a new study, it may also be the gentlest. It turns out, this vampire is actually a vegetarian.

The decisive clue to the vampire’s kinder nature came in the form of long, stringy tentacles. For decades scientists puzzled over the mystery of these strange appendages. Are they for mating? Defense? No one knew, until scientists observed the squid doing something altogether surprising. It turns out, vampire squid use these tentacles like fishing lines, but they’re not catching living prey, they’re catching ‘snow’. Vampire squid scoop up sinking ocean gunk, known as marine snow, with their thin yellow tentacles, and then suck it off these appendages (like licking your fingers). This gunk includes bits of algae, dead animals, poo and bacteria from the ocean above.

And while the ‘vegetarian vampire’ story may be distressingly familiar–I can guarantee the vampire squid came up with it first. The lineage that includes the vampire squid has been around since the Jurassic (as in dinosaurs), and while it’s called a squid, its family tree is so old that it’s neither a squid, nor an octopus, but something altogether different. A unique creature living gently in its dark, cold, inhospitable home. Twilight may have made millions in media sales, but it’s got nothing on this real life gentle ocean vampire.

Well, this no doubt sucks for lovers of big, scary animals. But one other quibble. Pretty sure squid can’t suck. With their mouths, I mean. That’s more a mammal thing.

Silverback Out for a Stroll

More camera trap magic: This is a silverback Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli), caught with a camera trap in Nigeria’ s Afi Mountain Wildlife Sanctuary. Cross River gorillas are the rarest of the four gorilla subspecies – numbering fewer than 300 individuals and found only in the forested, mountainous border region of Nigeria and Cameroon. (Photo: Wildlife Conservation Society/WCS)

Killer Sperm Causes Former Mate to Shrivel & Die

At last the superpower for which Rupert Murdoch secretly yearns. The rest of us are probably just going to read this and shudder.

The study described below follows on another recent roundworm study from Stanford University about “male-induced demise,” in which females suffer just from hanging around with males, and a study in fruitflies suggesting that each sex suffers from the presence of the other. Together these studies renew the debate about mating as a business of conflict or cooperation, and stir up lurking feelings about sex as life-death and heaven-hell. (Or is that just my parochial school background re-surfacing? Sister Mary of the Immoral Thoughts, Words, and Acts has a way of hanging on, sternly.)

Here’s the press release from Princeton University:

Sperm and seminal fluid causes female worms to shrivel and die after giving birth, Princeton University researchers reported this week in the journal Science. The demise of the female appears to benefit the male worm by removing her from the mating pool for other males.

The researchers found that male sperm and seminal fluid trigger pathways that cause females to dehydrate, prematurely age and die.

“Their lifespans are cut by about a third to a half,” said senior author Coleen Murphy, an associate professor of molecular biology and the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics.

The death of the female after she gives birth fits into a general framework of sperm competition that has been observed often in nature, said Murphy. “Males compete to have their genomes propagated, and this often occurs at the expense of the female.”

Shortened female lifespans following mating have been observed before for roundworms, but the study is the first to document the body shrinkage and identify the underlying biological pathways, Murphy said.

“The fact that sex essentially kills the mothers after they have produced the males’ progeny has never been reported before and is shocking to most people who hear this story for the first time, including researchers who study these worms,” Murphy said.

Over the course of seven days, females who have mated shrivel up and die, whereas females who have not mated remain healthy.

The team found that the pathways by which the male kills the female are ones that researchers think exist for the purpose of slowing down aging during times of low nutrients.

“The males are taking these pathways and running them in reverse, causing the acceleration of aging and death,” Murphy said.

The researchers discovered the effect in the Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) roundworm, which is found in soil and rotting fruit and is about the size of a piece of lint. The roundworm is commonly used in research because many of its genetic pathways are similar to those of humans.

“That these pathways can be hijacked and run in reverse in a simple organism might suggest that that could also happen in more complex organisms,” said Murphy. “So the work can help us understand male-female interactions and how they influence female longevity and reproduction.”

Normally the females of the species C. elegans have no need for males, Murphy explained, because they are hermaphrodites — their bodies contain both sperm and egg cells so they can reproduce without coming in contact with males.

“The hermaphrodites try to avoid the males — they will try to sprint away from them. The males have to hunt them down to get them to mate,” said Murphy.

Males, however, require females if they are to pass on their genes to future generations. Once inseminated, the female can give birth to hundreds of progeny, and these offspring do not require maternal care after they are born. Killing off the mother makes her unavailable to mate with other males, giving a genetic advantage to the father.

Graduate student Cheng Shi, lead author on the paper, discovered the effect unexpectedly while carrying out studies to look at the effect of aging on reproductive health. He was conducting experiments that required him to mate female and male worms.

“I saw a dramatic reduction in the size of the females,” said Shi, “so I started taking additional images and measuring the effect.” Shi began exploring how the sperm or its surrounding seminal fluid could cause the shrinkage and death.

He discovered that seminal fluid acts on a biological process that helps the worms conserve energy during times of stress. The seminal fluid acts on a transcription factor, or protein, called DAF-16 in the nucleus of cells that turns on the genes necessary to respond to stresses such as heat or low nutrients. In mated females, the factor is somehow driven out of the nucleus so it cannot activate the stress response system, causing fat loss and lifespan decrease.

Sperm acts via another mechanism to shorten longevity, Shi found. The sperm causes the shut-off of a factor called DAF-9 that activates a separate nuclear hormone stress response pathway involving another molecule called DAF-12, leading to water loss, shrinking and shortened lifespan.

The researchers found that the lethal effect occurred not only in the elegans species but also in other types of worms from the Caenorhabditis genus that are not hermaphroditic. “The fact that it is conserved in true male-female species, not just hermaphrodites, suggests that it is an important, conserved biological mechanism,” Murphy said. Although it is not yet known whether sperm and seminal fluid also kill other animals after mating, the longevity pathways involved are conserved in other organisms.

“Our results indicate that there are factors in seminal fluid and sperm that shut off these two stress-response mechanisms,” Murphy said. “It is a one-two punch, with two independent pathways that males use to kill the females.”

December 19, 2013

Strange New Brazilian Porcupine Discovered

New South American porcupine (Photo: Hugo Fernandes-Ferreira)

The big news in species discovery this week is the first new tapir species since 1865–an animal that can weigh in at 240 pounds.

But this one is quirkier. Here’s the report from a web site that snarks it up amusingly, or idiotically, depending on your point of view. The author seems to think the new species is some sort of bizarre cross between a porcupine and a monkey. It’s really just a porcupine, not a “monkey pine”:

Biologists from the Federal University of Paraíba in Brazil have discovered a new species of porcupine that – to the uninitiated – basically just looks like an amazing, pug-nosed, spiky monkey.

With a prehensile tail, these Coendou porcupines are very similar to most internet writers we know: nocturnal, solitary, prickly, and slow-moving. Found only in Central and South America, the monkey-pines live in trees, where they spend their nights collecting leaves and fruit for food. Their tail operates as a fifth hand for balance in the treetops; unfortunately, they’re incapable of jumping, and have to climb all the way down if they want to venture into a new tree.

This new species of monkey-pine is called the Coendou baturitensis, or the Baturite porcupine. According to this paper in Revista Nordestina de Biologia, “[t]he name refers to the locality of origin, a forests on a mountain range similar to the Brejos de Altitude of the Brazilian Northeast.”

Sadly, the Baturite monkey-pine probably wouldn’t make the greatest of pets, as it is still covered in sharp, tri-colored quills. Cuddle with caution.

Here’s a more detailed (and less fanciful) report from Sergio Prostak at Sci-News.com. The new species is from the Brazilian state of Ceará, right out on the easternmost tip of the country.

December 18, 2013

Elephant Poaching: The Disaster in Tanzania

Vulture droppings on a slaughtered elephant ((Photo: Udzungwa Elephant Project)

Back in October, I reported on how Tanzania had reluctantly agreed to a proper scientific count of the remaining elephant population in the Selous ecosystem. At the time, one of the conservationists involved in the survey emailed, “Lots of talk about how to manage media once the numbers come out since they’re expected to be so bad.” Now the results are out, and they are dire.

Apparently, managing the media means keeping these results as quiet as possible.

But here’s a report from National Geographic:

In Tanzania, which until recently harbored the continent’s second largest number of savanna elephants (after Botswana), the results of an aerial census of the Selous ecosystem carried out this October have just been announced—at the 9th Scientific Conference of the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI), held December 4-6 in Arusha.

The Selous ecosystem (31,040 square miles) is Africa’s largest protected area and holds East Africa’s greatest elephant population. In the early 1970s, it was estimated to exceed 100,000 elephants, but by the end of the last great ivory poaching crisis in the late 1980s, the number had fallen to about 20,000.

Following the global ivory trade ban enacted in 1989, the population recovered to about 55,000 elephants by 2007—when the current wave of killing escalated. By 2009, Selous elephants were down to about 39,000.

The latest, recently announced population estimate is 13,084. This indicates an unprecedented decline of nearly 80 percent over the last six years.

We await with trepidation imminent results from East Africa’s second largest population, Ruaha-Rungwa (13,384 square miles), also in southern Tanzania, where large numbers of fresh carcasses are reported from Rungwa Game Reserve and parts of Ruaha National Park.

If, somewhere on your bucket list, you are hoping to make a safari in Tanzania, better do it quick. Unless the government there takes dramatic action to stop the poachers, there won’t be anything left to see.

December 17, 2013

This Year’s Rhino Death Toll Edges Toward 1000

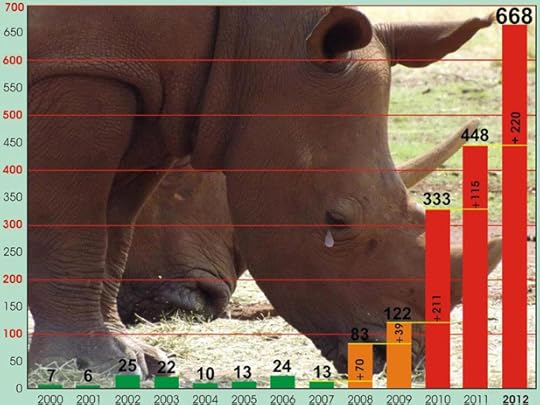

As of today, South Africa has lost 919 rhinos this year, slaughtered by poachers to supply the demand for ivory knickknacks in China, Vietnam, and Thailand. That’s not counting the rhino killings elsewhere in Africa, and in Asia.

This graphic from WESSA, The Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa, illustrates just how recently the killing has gone out of control. The WESSA web site also gives a hint of how little South Africa has done to stop it.

I’d be interested to see data on prosecutions and penalties. It puzzles me, for instance, that Dawie Groenwald and his gang, including veterinarians, big game hunters, and other wildlife professionals, were arrested in September 2010 in a rhino poaching conspiracy said to have made millions, but still have not gone to trial three years later.