Richard Conniff's Blog, page 63

November 20, 2013

Protecting Wildlife: Open Gates or Shoot-to-Kill?

(Photo: Daniel Munoz/Reuters)

With the last of the wild elephants, rhinos, and tigers in immediate danger of being wiped off the face of the planet, it’s tempting to think that parks and other protected areas should adopt a shoot-to-kill policy toward poachers. This is, however, a dangerous idea—on a par with, say, using drone warfare to win peace in Pakistan.

What I’ve instead seen in my travels suggests that you obtain better results, and they last longer, when you make neighboring communities partners in parks and other protected areas, so they have a sense of ownership. If local communities know that they will profit year after year from the wildlife and natural habitat around them, social pressure tends to shut down the criminals who kill for a quick buck.

Just last month, for instance, the journal Ecosphere published a study about the area around Chitwan National Park in Nepal’s Himalayan foothills. Beginning in 1996, the park created a 75,000 hectare buffer zone beyond its borders, with a bottom-up, non-exclusionary management plan devised by neighboring communities. Locals can no longer graze livestock in the buffer zone, but they get to decide how to divvy up firewood, fodder, and other resources there.

The new study used camera traps and satellite imagery to analyze the effects, and it turned out that the buffer zone is now doing better than the park itself. Its forest has suffered less damage, and it’s also home to more tigers. The explanation is that top-down exclusionary management policies within the formal park borders have turned the park into government land, and thus fair game. So the growing human population continues to venture there for whatever resources they can carry out. But local ownership makes the buffer zone “ours.” People call in wildlife authorities if they spot intruders and they complain loudly if they sense unfair or imprudent management practices. Overall, the tiger population in the Chitwan District has increased from 91 in 2009 to 125 today, even as traditionally managed parks in neighboring India continue to lose tigers to poaching.

That’s the logic of community management that I find so appealing, particularly as an alternative to the developing militarization of parks. The tendency to militarization turned up just last week, for instance, in a Reuters story. In South Africa’s Madikwe Game Reserve, it reported, “New infantry-style tactics of concealment and ambush by armed park rangers are credited with turning the tide in the war against poachers.”

As it happens, Madikwe was once just the kind of community-focused protected area I had in mind. When I first visited in the 1990s, it was a bold experiment just beginning to get off the ground. The organizers were taking 290 square miles of derelict ranchland—that’s an area roughly as big as Salt Lake City—and turning it back into a wildlife habitat for the specific purpose of bringing tourist revenue into South Africa’s Northwest Province. Since then, 30 lodges—two of them owned by local communities—have sprung up in and around the park to meet the demand from tourists. Neighboring communities provide staff at all the lodges, and they share in the revenues.

Even so, Madikwe lost 18 rhinos to poachers last year and another nine in the first three months of this year. Maybe that shouldn’t be too surprising, since South Africa is the epicenter of the war on rhinos. I was, however, surprised. Apart from the benefits of community involvement, Madikwe is also protected by a 10-foot-high, 110-mile-long fence that’s built with steel-reinforcing cable and a 7,000-volt electric wire. And yet the only thing that seems to have deterred the poachers is providing the rangers there with proper weapons and training.

A former British special forces soldier, brought in by a South African foundation, put the rangers through a kind of boot camp. The reserve’s rangers, many of whom literally had no boots, got them, as well as other essential law enforcement equipment. “People are still saying this isn’t a low-level war,” said Declan Hofmeyr, the operations manager at Madikwe. “It’s not, it’s a full-out war. “

I get his point: This year’s death toll for rhinos in South Africa is on track to exceed 900 animals, up from 668 last year—and up from almost nothing just six years ago. The current madness is entirely a product of Asian economic prosperity, and of the eagerness of rich suckers in China and Vietnam who are willing to fork over huge sums of money for bogus folk medicine. Hofmeyr also has the numbers to back up his argument: Not a single rhino has been killed at Madikwe since the properly trained and equipped rangers went to work on April 2. The good news is that there haven’t been any poachers killed either.

So what’s the bottom line?

Deterrence counts. But that doesn’t mean shoot-to kill militarization. It means routine law enforcement, properly funded and trained, from field patrols, to courthouse, to prison. Community management of wildlife—or co-management with park authorities—is also essential. It has worked not just in Nepal, but also in South Africa’s neighboring country, Namibia, where community conservancies control 40 percent of the land area—and where poaching of rhinos is almost nonexistent.

You need to be serious, though, about both the deterrence and the community involvement. If Madwike wasn’t even bothering to supply boots, much less weapons, to its ranger staff, that suggests something deeply wrong with the sharing of resources. Park rangers everywhere need to carry something better than a big stick, to paraphrase Teddy Roosevelt. But parks also need to speak softly, spread the wealth around, and win friends.

The people living outside the gate should not be the enemy.

Hello, China? This One Needs No Translation

It’s a recording of the sound of elephants being shot and killed in Gabon, to turn their tusks into ivory knickknacks that are the blood status symbols of China’s newly rich:

Here’s the press release from the Wildlife Conservation Society:

NEW YORK (November 20, 2013) — The Wildlife Conservation Society released a powerful video today that features shocking audio of an elephant being shot and killed by ivory poachers in Central Africa. The video is part of WCS’s 96 Elephants campaign – named for the number of elephants gunned down by poachers every day.

The low-frequency recording, taken in Gabon in Central Africa, was made by scientists from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Elephant Listening Project studying low frequency communication of elephants using remote devices left in the field then retrieved and analyzed months later. Gabon’s National Parks Agency (ANPN) is a partner on the project.

The 60-second video opens on a black screen with text that fades up: This is the sound of an elephant fleeing an armed poacher as it is shot repeatedly in the forests of Central Africa. As the audio begins, a running counter appears: How long can you listen? The black backdrop slowly fades to the image of a fallen elephant. Text fades up while the counter keeps running: 35,000 elephants were killed in Africa in 2012. That’s 96 elephants killed everyday. You can make it stop. 96elephants.org

WCS’s 96 Elephants campaign amplifies and supports the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) commitment to save Africa’s elephants announced in September. The WCS campaign focuses on: securing effective U.S. moratorium laws; bolstering elephant protection with additional funding; and educating the public about the link between ivory consumption and the elephant poaching crisis.

Throughout Africa, elephant numbers have plummeted by 76 percent since 1980 due largely to the demand of elephant ivory with an estimated 35,000 slaughtered by poachers in 2012 alone.

Pretty Picture, Pretty Season

At Bluestone State Park in West Virginia (Photo: Carolyn Manney)

Posting this photo for no better reason than beauty. I like the richness of the season and the photograph, which was taken by my niece Carolyn Manney on a visit last month to Bluestone State Park in West Virginia.

November 16, 2013

The Bizarre Food Grizzlies Use to Fatten Up for Winter

(Photo: Karen Bleier/AFP/Getty Images)

My latest for TakePart:

Right about now, the grizzlies of Yellowstone National Park are starting to think about hibernation. This week or next, as food becomes scarce, they’ll head up into the mountains and hunker down in dens under rocks and trees. They’ll cut their metabolic rate in half, drop their heart rate down to about 18 beats a minute, and take a breath only once every 45 seconds. And they’ll stay like that until springtime.

Many of the park’s bears will be getting by for the winter largely on the energy built up from gorging on moths. That’s right: The largest and most ferocious predator in North America eats fluttery little army cutworm moths (Euxoa auxiliaris).

A grizzly researcher first discovered this strange behavior in 1952. But nobody paid much attention until the mid-1980s, when a radio-collared grizzly bear wandered up to the steep rocky slopes, and researchers started to wonder just what it was doing there.

A couple of amateur naturalists were at the time spending half of every year in the field watching grizzly bears, and they did the first real study of moth-eating behavior. I met Steve and Marilyn French back then and spent some time wandering with them in grizzly habitat, as they studied how grizzlies adapted to every possible food source in their environment, including the moths.

Those kinds of details mattered then because grizzlies had been listed as a threatened species. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service delisted them in 2007, under pressure from politicians in Wyoming. But a federal judge reinstated protection two years later, and grizzly diet was a critical factor. He noted that the bears depended on nuts from whitebark pine trees, a species that had sharply declined because of tree-killing beetles. Environmental groups are now suing to block the continued FWS effort to delist the species, which could happen as soon as next year. Fewer than 1,000 individual grizzlies survive in the lower 48 states, down from 50,000 in the 19th century.

In the course of their research, Steve and Marilyn French documented how some bears depend on the spawning run of cutthroat trout. That’s another food source that has now almost disappeared, because of illegal introductions of lake trout, which not only eat cutthroats but do their spawning on the lake bottom—meaning no run for the grizzly bears.

The Frenches also documented the quirky nuances of grizzly bear foraging. In springtime, when the weather is wet, for instance, earthworms bunch up for unknown reasons under the park’s tufted hair grass. “And then the bears come and flip over the grass, and thp-thp-thp, it’s like spaghetti,” Steve told me.

Later, in the heat of summer, the couple followed at a distance as the bears climbed up into the mountains. There they watched them paw up rocks and flip them one by one downslope. The logic of this behavior mystified them at first. When they realized that the bears were feeding so enthusiastically on–of all possible foods–moths, they didn’t quite believe it.

To farmers across the Great Plains, army cutworm moths are an agricultural pest. The larvae emerge from the ground in farm fields from Wyoming to Kansas and proceed to cut down young plants for food (hence the name “cutworm”). Sugar beets, small grains, and alfalfa are prominent among their victims. Farmers retaliate with pesticides. If the larvae manage to survive, they mature into dusty little moths with a two-inch wingspan. The moths migrate in June, and the ones from Wyoming and Montana end up in the steep rocky slopes high in the Absaroka Mountains, on the eastern end of Yellowstone.

It ought to be a sweet life for the moths: Until mid-September they get to forage by night on nectar from the profuse blossoms of alpine flowers. Then they hunker down by day in dense congregations beneath the rocks. In the process they boost their fat stores from 13 to 83 percent of their body weight, to get ready for winter.

All that fat is just too tempting for grizzlies, because they also need to bulk up then, at a rate of about 20,000 calories a day. Researchers following in the Frenches’ footsteps have since learned that Yellowstone grizzlies can eat 40,000 moths a day.

In this fashion, according to one biologist, a grizzly “can consume half its yearly calories in 30 days.” Then the bears hole up for the long winter to sleep off the feast.

With luck, federal protection will hold, and they won’t wake up next spring to a different and far deadlier world.

November 14, 2013

Video Camera Trap Magic

Why Asia is Eating Wildlife to Extinction

As my previous blog item on the ivory crush suggests, the real trick to stop poaching of wildlife is to reach the customers, the end users, and help them see that their status symbols are in fact a mark of shame, and their folk medicines (like ours) prone to fraud and superstition.

Sonny Le

In this article, Sonny Le tries to get across just that message in his own family. Le is an immigrant from Vietnam who is now a communications instructor at San Francisco State University. This is his account of his first trip home since 1991.

My weeks-old youngest brother’s fever was not responding to conventional medicine. So my mother decided to use what she believed had worked for her four older children. She ground the tiger tooth in a small stone mortar, added a couple of teaspoons of water, then spoon-fed my brother the milky-white liquid.

He died the next day. In a fit of rage, my father took the tiger tooth and threw it into the river a few meters from our back door.

Tiger teeth and claws sold as amulets and charms to ward off evil spirits

Photo: Wild Asia

The tiger tooth was a family heirloom, given to my parents by my relatively rich saw mill-owning maternal grandparents in the Mekong Delta town of Rạch Giá as a wedding present. I wore this very tiger tooth around my neck the first two years of my life. It was believed to not only possess medicinal properties, but also the power to ward off ‘evil spirits,’ from which I needed protection as the first-born son.

According to legend, tigers once roamed the forested swamps of the Mekong Delta region and the tooth came from one of those tigers whose spirits now lorded over the underworld. In reality, that ‘tiger’ tooth could have come from a water buffalo, a wild boar, or even a big dog. No one ever asked why or how those tigers were killed, or if they ever existed.

Egrets in Tràm Chim National Park, Vietnam Mekong Delta

When we moved to a rural village outside Rạch Giá, we discovered a few pairs of migrating white egrets had built nests in a cluster of melaleuca trees (cây tràm) on our land. Everyday my brother and I couldn’t wait to check on the nests. We would snatch the eggs as soon as they were laid. We even managed to shoot down a few birds with a slingshot. After a few years we noticed the egrets no longer came back, but didn’t understand why.

We were poor farmers whose diets consisted mostly of vegetables and fish. We raised chickens and pigs, but they were investments, our savings. The bird eggs and the occasional birds, snakes and turtles, even field rats, were a real treat. When we caught fish, we caught and ate everything, big and small. During the flooding season, the most-prized fish were the baby ones: no bones. The most sought-after baby fish were the snakehead.

To make a meal consisting of baby snakeheads, our family would essentially wipe out four or five broods of future snakeheads, the salmon of the Mekong Delta.

We also ate many things for novelty’s sake, for their rarity. Importantly, we didn’t understand how NOT taking the egrets’ eggs or catching the baby snakeheads would be beneficial to us. We thought if we didn’t, someone else would.The concept of wildlife protection or nature conservation was not part of the culture. The terms were not even common words.

After nearly 11 years in the U.S., I went back to Vietnam for the first time in 1992 to find my family much better off, no longer subsisting off the land. Not long after my arrival, my father put word out among the vendors at the local wet market that he was looking for exotic fare, i.e. turtles, snakes, birds and prized big fish.

He was quite disappointed when I told him all I wanted was steamed water spinach and cá rô kho tộ (anabas or climbing gourami cooked in a clay pot) for dinner. I wanted to taste the simplest meals that I remembered growing up with. My family didn’t quite understand why a man coming back from a rich country would want to eat nothing but peasant fare.

They eventually gave up trying to understand me and I on explaining to them that comfort foods were not necessarily expensive or exotic.

Wherever I went on that first visit, everybody wanted to feed me the ‘best’ food, which invariably included wild-caught snakes, turtles, and birds, among others. The notion that wildlife is worth more in the wild than on the plate was not easily understood because many did not see themselves directly, or even indirectly, responsible for the catching or killing of such wildlife. They simply saw themselves as consumers, rationalizing that if they hadn’t purchased the snakes, birds or turtles, others would.

I reminisced with my brother about our childhood and when I explained to him my theory of why those birds didn’t come back to our melaleuca trees, he had a hard time believing it, but I could sense his feeling of guilt. I felt bad for telling him what we, as kids, may have unwittingly done.

Many of my relatives today, including those of the younger generation, relish the opportunity to lavish themselves with potions, elixirs and wild game that once only the rich could afford. They do have an inkling that the potions and elixirs may not possess anything magical, but believing it wouldn’t hurt to try them anyway. However, they won’t feel nostalgic, or be willing to break the law for exotic animals if and when they’re no longer sold in the market. For them, it has everything to do with the novelty, with a break from the everyday’s Vietnamese three-course meal now that they can afford it. No more no less.

It may take time for conservation education to take hold, to become part of the cultural mindset, and even longer for existing laws to be enforced without being corrupted. Sadly, time already ran out on Vietnam’s last Javan rhino and elephant recently and many other species endemic to Vietnam and neighboring Southeast Asian countries are now on endangered list.

The insatiable appetite of Vietnam’s newly-rich for the exotic has not only put their natural heritage at risk, but also endangered animals a continent away in Africa. A shocking 587 South African rhinos, and another 35 in Kenya, have been killed to date in 2013 for their horns, most of which are believed to have been smuggled into Vietnam where a set of horns from a single rhino can fetch up to $1 million.

Just imagine: on the average, two rhinos are now killed each day because of a rumor that their horns, which are made of keratin just like your and my finger and toe nails, had cured cancer.

November 12, 2013

Why The Ivory Crush Won’t Save Elephants

Tusks in Hong Kong: (Photo: Bobby Yip/Reuters)

Later this week, at a facility outside Denver, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will take almost six tons of contraband ivory, the final remains of several thousand elephants, and crush them down to worthless dust. It will be in part a ritual gesture of protest, though there’s not much poetry in an industrial rock crusher.

I have some reservations about the plan, which I’ll get to in a minute. But the logic of the ivory crush is straightforward: These are end times for elephants in the wild. Poachers are now killing 35,000 of them a year—that’s 96 a day, or one every 15 minutes. Their tusks end up carved into ivory status symbols for Asia’s nouveaux riches. At the current rate, conservationists predict that African elephants could be extinct in the wild within 12 years. The forest elephants of West Africa are especially imperiled, having already suffered a 62 percent decline over the past decade.

“Destroying this ivory,” says FWS on its web site, “tells criminals who engage in poaching and trafficking that the United States will take all available measures to disrupt and prosecute those who prey on and profit from the deaths of these magnificent animals.”

The FWS action also sends a message to other nations not to seek blood money by selling their own confiscated ivory. Stockpiles in Zambia, Mozambique, and the Philippines have all experienced shrinkage, generally “as corrupt officials are paid to leak stuff out of them,” Elizabeth Bennett of the Wildlife Conservation Society told me. Seventy percent of what’s sold in China as legal ivory is in fact illegal in origin, she added.

So why do I have reservations about the ivory crush?

Partly it’s that we’ve all been here before. The ivory crush aims to recapture the electric effect of Kenya’s 1989 decision to turn 12 tons of contraband ivory tusks into a raging funeral pyre. The whole world took notice then, and it quickly resulted in an international ban on trade in African ivory. But that kind of grand gesture only works the first time around.

When Gabon tried something similar in 2012 and the Philippines did it early this year, hardly anyone noticed. (No one burns ivory any more, by the way, because the flames leave most of the tusk intact. Hence the switch to crushing.) The only way to achieve the Kenya effect again would be to up the ante. To suggest a wildly unlikely example, if New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art decided to toss the Byzantine Ivories into the crusher by way of protest, the world would undoubtedly take note.

The other problem with the ivory crush is that Kenya’s gesture only managed to slow the poaching. Nor did the resulting ban on trade in 1989 completely stop it. Africa had 600,000 elephants in 1989. It has fewer than 470,000 today. ”To stop the poacher, the trader must also be stopped and to stop the trader, the final buyer must be convinced not to buy ivory,” Kenya’s then-President Daniel arap Moi declared the day he set the ivory aflame. And he had a point: The problem with gestures like the ivory crush is that they focus on the supply side. They may gratify the righteous outrage of elephant lovers everywhere, but the real challenge is to stop the demand for ivory. The dramatic rise in poaching over the past few years closely tracks the enormous expansion of wealth in China and other “tiger” economies of Asia.

How do we get to those end users?

“There are lots of ideas out there, none of them yet proven,” Elizabeth Bennett told me. “We’re working through social media in China, trying to get people to like elephants and recognize what the ivory trade does to them.” Yao Ming, the former National Basketball Association player who is China’s most famous athlete, has made public service announcements on behalf of elephants, and the conservation group Save the Elephants brought Chinese superstar Li Bingbing to Kenya to see the effects of poaching up close, and spread the message back home. The aim is to stigmatize the craving for ivory objects.

It is important work, and may eventually produce results. The children or grandchildren of the people who are now pushing Africa’s elephants toward extinction will no doubt someday wake up to the tragedy of what their forebears have done. Those precious and beautifully-carved ivory knickknacks may in time survive not as symbols of a family’s status, but as a mark of its shame.

Or maybe some unpredictable shift in taste will end the killing of elephants. Maybe owning a David Hockney silkscreen, or a Zhang Xiaogang (he’s China’s most celebrated contemporary artist)—or even just a new iPhone—will displace ivory as a leading status symbol. But at the present rate of killing, it will almost certainly come too late for the elephants.

In that context, the ivory crush risks becoming just another media event. What we need to get real change now is rapid and decisive legal action. That means tightening up the incredibly lax and loophole-prone business of controlling trade in ivory. It means imposing real economic and political penalties on countries that are culprits in the trade.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) belatedly started that process at its meeting last March, when it threatened sanctions against eight problem countries unless they come up with a plan of action to end illegal trade in ivory. (The countries are Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda on the supply side, Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines in transit, and China and Thailand as the customers.)

It also stipulated that countries must complete an audited inventory of ivory stockpiles by next July. And that should give you an idea just how slow and timid the effort to end the war on elephants has been up to now. That deadline–to achieve the most rudimentary kind of accounting baseline for contraband ivory—will come almost exactly 25 years since Kenya set its stockpile of ivory up in flames.

November 9, 2013

Space Flight and The Peril of Boiling Blood

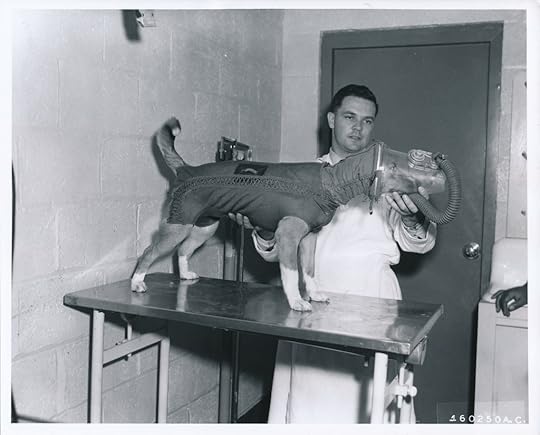

Here are a could more photos from my Dad’s files for a 1958 story about the U.S. manned space flight program. There were clearly a lot of worrisome possibilities in going into space, including the danger of rapid depressurization. So the preliminary testing–and the press demonstrations–were elaborate. This was a visual of what happens when the blood boils:

Loss of pressure = boiling blood

This is my dad’s proposed caption:

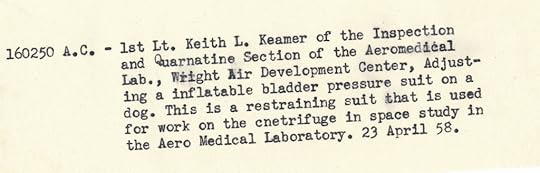

You go first. One way to minimize the risk for human pilots was to try it on monkeys first:

Space monkey

tktkt

The Heartbreaking Fate of Pangolins

Pangolin in rehab (Photo: Sukree Sukplang/Reuters)

My latest for TakePart:

Pangolins are among the oddest and least-familiar animals on Earth. They’re mammals, but they’re armor-plated. Their chief defensive posture is to tuck their heads under their tails and roll up, like a basketball crossed with an artichoke. (It works: Even lions generally can’t get a grip.) They have tongues that are not only coated with a sticky, fly paper-like substance but can also extend up to 16 inches to probe into nests and snag ants for dinner. They’re shy, nocturnal and live either high up trees or deep underground.

Lisa Hywood has lately discovered just how charismatic these obscure creatures can be. At the Tikki Hywood Trust, her rescue center in Zimbabwe, one of her current guests, named Chaminuka, recognizes Hywood and makes a soft chuffing noise when she comes home. Then he stands up to hold her hand and greet her, she tells me. (Bit of a snob, though: He doesn’t deign to recognize her assistants.) Hywood finds working with pangolins even more emotionally powerful than working with elephants.

False hope for medicine

It’s also more urgent: Pangolins, she says, are “the new rhinos,” with illegal trade now raging across Asia and Africa. They are routinely served up as a status symbol on the dinner plates of the nouveaux riches in China and Vietnam. Their scales are ground up, like rhino horn, into traditional medicines. Pangolin scales, like rhino horn, are made from keratin and about as medicinally useful as eating fingernail clippings. When poachers get caught with live pangolins, Hywood rehabilitates the animals for reintroduction to the wild.

But a lot of pangolins aren’t that lucky. By one estimate, poachers have killed and taken to market as many as 182,000 pangolins since 2011. And the trade seems only to be growing bigger. In northeastern India early this week, for instance, authorities nabbed a smuggler with 550 pounds of pangolin scales. Something like that happens almost every week. Many more shipments make it through.

There is little prospect that this trade will stop, short of extinction for the eight pangolin species. Two of the four species in Asia are currently listed as endangered and likely to be moved soon to critically endangered status. As pangolins have vanished from much of Asia, demand has shifted to Africa, which also has four species. The price for a single animal there can now run as high as $7,000, according to Darren Pietersen, who tracks radio-tagged pangolins for his doctoral research at the University of Pretoria.

In a handful of trouble

Hunters use dogs to locate arboreal pangolins or set snares outside the burrows of ground-dwelling species. That rolled-up defensive posture, which works so well against lions, just makes it easier for human hunters to pick them up and bag them, says Dan Challender, cochair of the Pangolin Specialist Group of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. His research has taken him to a restaurant in Vietnam where, by chance, he witnessed a pangolin being presented live to a diner, then killed to be eaten. At such restaurants, stewed pangolin fetus is a special treat.

The trade is already illegal in many countries, and it is also banned by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. But enforcement is minimal, and even poachers seized with tons of smuggled animals often get away with a wrist slap. Authorities sometimes dispose of these shipments by auction, cashing in on the illegal market.

It could be worse than what’s happening to elephants and rhinos.

Zoos at least know how to breed those species in captivity, says Hywood. But so far, no one has managed to captive-breed any of the eight pangolin species. That means that if Chaminuka and his ilk go extinct in the wild before scientists can figure that out, these curious creatures will be gone forever.

November 8, 2013

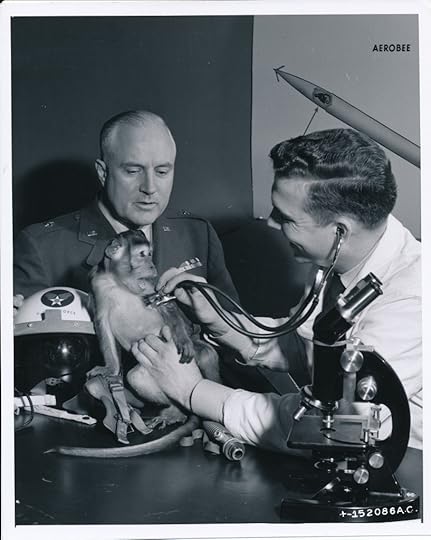

Bubbles the Space Cat and the Test Dummy Dog

I’m going to venture a little far afield today, though still decidedly within the realm of “strange behaviors.”

These are more photos I pulled out of my Dad’s files for a story he wrote about space travel in the late 1950s. I’ll do the animal photos first. Will follow with some photos of human space program folk later, or tomorrow, as I get the chance.

Since space monkeys hog all the attention, let’s start with a cat and a dog.

I’m posting the captions from the U.S. Air Force below each photo. I get the impression the cat probably did not have finally approval over use of the word “merrily” in this one:

On the other hand, this unnamed dog gives off a decided “Put me in, coach” aura of readiness for launch.

Is this where the Mercury 7 learned that stoic, straight-ahead gaze of imperturbability?

More to come.