Richard Conniff's Blog, page 56

January 21, 2014

Texans Say Gassing Rattlesnakes Not Really Fun For Entire Family

(Photo: Paul Sutherland/Getty Images)

UPDATE: The Parks and Wildlife Commission last night pulled the gassing issue off the agenda for tomorrow’s meeting. No reason given. The commission expects to hear the issue at its next meeting on March 27, a few weeks AFTER the Sweetwater Roundup. Meanwhile, keep your comments coming (see below).

My latest, for Takepart:

Here’s an entertaining outdoorsy idea for springtime in Texas: Fill a garden sprayer with gasoline, and go around spraying the fumes into the cracks, crevices, sinkholes, and caves where rattlesnakes make their dens. Do it early in March, when the snakes are just drowsily waking up from their winter hibernation and too helpless to defend themselves.

Then as the snakes escape to the surface to flee the noxious fumes, pick them up, toss them in a sack, and bring them to the “world’s largest rattlesnake roundup,” held on March 8 and 9 in Sweetwater, Texas. It’s billed by the Sweetwater Jaycees as “fun for the entire family” and a major fund-raising event for local civic groups.

If, on the other hand, gassing semiconscious rattlers sounds like a barbaric vestige from our own cave-dwelling days, you may want to drop in on the Jan. 23 meeting of the State Parks and Wildlife Department in Austin. Commissioners are likely to ban the use of gasoline or other noxious chemicals to dislodge wildlife (with the obvious exception that you’ll still be able to spray pesticides on wasps in the yard or on crops). Texas will thus join 29 other states that already outlaw gassing.

The vote comes at the culmination of a yearlong round of research and public hearings on rattler gassing, which state officials say kills about 40 percent of the rattlers collected (and perhaps others that remain underground). It is likely to meet vocal objection mainly from residents of Sweetwater, a town of 10,600 about three hours west of Fort Worth.

“Last time I heard, rattlesnakes were not an endangered species,” Sweetwater Mayor Greg Wortham recently thundered to a reporter from the Star-Telegram. “People in Austin don’t understand. We’ve got to protect our families, ranchers, people who work in oil fields, on wind turbine sites.” (Fatalities from rattlers or any other venomous snakes are extremely rare in the United States.) Blaming out-of-staters for the proposed ban, Wortham added, “If they love [the snakes] so much, I might just start a rattlesnake relocation program and send a box full to Massachusetts.”

In fact, much of the objection to gassing has come from other Texans. Because there are no longer enough rattlers in Sweetwater to meet the city’s roundup quota of several thousand snakes, collectors tend to work throughout the region. The gasoline they spray inevitably finds its way through the porous karst, or limestone, and into groundwater, which, as the Houston Press drily noted, is “bad news for anyone or anything—especially out in West Texas—who, you know, likes to drink water.”

Gassing is also bad news for other karst wildlife, according to a state analysis. Studies have found “dramatic and obvious” effects, from “short-term impairment to death,” in multiple species of snakes, lizards, toads, and other vertebrates living in and around the rattler denning sites. The gassing is also a threat to the many karst invertebrates listed as endangered or threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, among them the Comal Springs riffle beetle, the Bone Cave harvestman, and the Government Canyon Bat Cave spider.

The state report notes that, as those names suggest, “some are known only from single sites, making them some of the most geographically limited organisms in the world.” In theory, one overzealous collector with a can of gas could push an entire species into extinction.

The proposed gassing ban is not a referendum on the colorful Texas tradition of snake roundups. When state herpetologist Andy Gluesenkamp surveyed the eight or so active roundups, he said, organizers of all except Sweetwater’s told him they’d already abandoned gassing. Sponsors of the “World Championship Rattlesnake Races” in San Patricio, for example, “were absolutely horrified that anybody would gas snakes,” Gluesenkamp told me. “They said, ‘You can’t race ’em if you gas ’em.’ ” Like other roundups, that festival relies in part on rented snakes for many events.

At most roundups, Gluesenkamp said, the rattlesnakes are essentially the marquee item to attract people to a weekend of music, food, flea markets, and other events. That’s not to say they lack distinctive Texas flavor. Jackie Bibby, “the Texas Snake Man,” is a standard feature. He arrives in a white hearse and performs in a clear plastic bath that assistants gradually fill with rattlesnakes. His Guinness World Records include 195 snakes in the bath and, separately, 13 in his mouth. “I don’t necessarily approve of sticking a dozen snakes in your mouth,” said Gluesenkamp, “but it’s not impacting the rattler population.”

The roundup in Taylor features an event in which contestants lie in sleeping bags while assistants stuff them with rattlers. Bibby holds the records there too—109 snakes when he’s lying the usual way in the bag, and 24 lying headfirst.

Other rattlesnake events in Texas and other states have gradually moved toward public education about snakes. This year, said Gluesenkamp, a group of snake lovers is organizing an alternative event the same weekend as the gassing in Sweetwater. The Texas Rattlesnake Festival will take place in Round Rock, four hours down the road, to celebrate rattlers and other snakes.

Well before then, the vote to ban gassing will take place at a meeting at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department headquarters in Austin on Jan. 23 at 9 a.m. Gluesenkamp is optimistic about the outcome. But commissioners still need to hear public support for the proposed ban on gassing. (You can let the commissioners know how you feel, through 5 p.m. Central time on Jan. 22, at this website for public comment.)

“The need to stop this,” one worried Texas herpetologist told me, “is as obvious as the fact that evolution ceased being a theory ages ago and the earth is older than 6,000 years. So you can see what a difficult problem this could be in Texas.”

Favorite Science Headline of the Morning

(Photo: Dante B. Fenolio/Arkive.org)

Not sure the writer of this press release intended the headline to be funny, even so. I like the title of the scientific paper, too: “Strange Parental Decisions …” We’ve all made a few of those, I guess.

In this case, a rain forest frog does the equivalent of a dad on the road with his kids stopping at the diner with the most crowded parking lot.

Only it turns out the kids may be on the menu.

Frog Fathers Don’t Mind Dropping Off

Their Tadpoles in Cannibal-Infested PoolsJan. 20, 2014 — Given a choice, male dyeing poison frogs snub empty pools in favor of ones in which their tiny tadpoles have to metamorphose into frogs in the company of larger, carnivorous ones of the same species. The frog fathers only choose to deposit their developing young in unoccupied pools when others are already filled with tadpoles of a similar size as their own. These are seemingly counterintuitive decisions, given how often cannibalism involving a large tadpole eating a smaller one takes place in natural pools, writes Bibiana Rojas of the University of Jyväskylä in Finland. Her findings are published in Springer’s journal Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology.

Rojas studied a population of dyeing poison frogs (Dendrobates tinctorius) in the forests of French Guiana. In nature, these frogs lay clutches of four to five eggs. When hatched, the males carry the tadpoles to water-filled cavities in treeholes or palm bracts. Once at their rearing site, tadpoles remain unattended but also unable to leave, until their metamorphosis about two months later.

Choosing good places to deposit tadpoles generally has direct effects on fitness or the continuation of a parent’s genetic line. This is because the conditions that larvae experience affect their survival and their life history in terms of the time and size at which metamorphoses takes place.

Rojas found, if given the choice, male dyeing poison frogs prefer taking their newly hatched tadpoles to pools already occupied by larger conspecific larvae — this despite the high risk of cannibalism.

She believes that the presence of a larger conspecific tadpole is a signal to frog fathers that conditions in a specific pool are conducive to larval development. Also, parents might have little choice other than depositing their tadpoles in already occupied pools because so very few suitable ones are around.

“The presence and the size of conspecifics influence parental decision-making in the context of choosing a rearing-site for their offspring,” says Rojas. “Apparently strange parental decisions, such as depositing offspring with large cannibals, may ultimately not be that strange.

The researcher continued, “The decision is like a gamble for the frog father! Chances are that its tadpole gets eaten by a large resident in an occupied pool, but an unoccupied pool might mean, for example, that other requirements for development, such as the stable presence of water, are not met. If the father is lucky and its tadpole is not eaten, it may ultimately be safer in a stable pool than in one that could easily dry out.”

Bibiana Rojas. Strange parental decisions: fathers of the dyeing poison frog deposit their tadpoles in pools occupied by large cannibals. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 2014; DOI: 10.1007/s00265-013-1670-y

January 20, 2014

A Trophy Hunt That’s Good for Rhinos

(Illustration: Liam Barrett)

My latest, for The New York Times:

Let’s stipulate up front that there is no great sport in hunting a black rhinoceros, especially not in Namibia’s open countryside. The first morning we went out tracking in the northern desert there, we nosed around in vehicles for several hours until our guides spotted a rhino a half mile off. Then we hiked quietly up into a high valley. There, a rhino mom with two huge horns stood calmly in front of us next to her calf, as if triceratops had come back to life, at a distance of 200 yards. We shot them, relentlessly, with our cameras.

Let’s also accept, nolo contendere, that trophy hunters are “coldhearted, soulless zombies.” That’s how protesters put it following the recent $350,000 winning bid for the right to trophy hunt a black rhino in Namibia. Let’s acknowledge, finally, that we are in the middle of a horrific global war on rhinos, managed by criminal gangs and driven by a perverse consumer appetite for rhino horn in Southeast Asia.

Even so, auctioning the right to kill a black rhino in Namibia is an entirely sound idea, good for conservation and good for rhinos in particular.

Here’s why: Namibia is just about the only place on earth to have gotten conservation right for rhinos and, incidentally, a lot of other wildlife. Over the past 20 years, it has methodically repopulated one area after another as its rhino population has steadily increased. As a result, it is now home to 1,750 of the roughly 5,000 black rhinos surviving in the wild. (The worldwide population of Africa’s two rhino species, black and the more numerous white, plus three species in Asia, is about 28,000.) In neighboring South Africa, government officials stood by haplessly as poachers slaughtered almost a thousand rhinos last year alone. Namibia lost just two.

To be fair, Namibia has the advantage of being home to only 2.1 million people in an area twice the size of California — about seven per square mile, versus about 100 in South Africa. But Namibia’s success is also the product of a bold political decision in the 1990s to turn over ownership of the wildlife to communal conservancies — run not by white do-gooders, but by black ranchers and herders, some of whom had, until then, also been poachers.

The idea was to encourage villagers living side by side with wildlife to manage and profit from it by opening up their conservation lands to wealthy big-game hunters and tourists armed with cameras. The hunters come first, because the conservancies don’t need to make any investment to attract them. Tourist lodges are costly, so they tend to come later, or prove impractical in some areas. The Ministry of Environment and Tourism sets limits on all hunting, and because rhino horn is such a precious commodity, rhinos remain under strict national control.

The theory behind the conservancy idea was that tolerance for wildlife would increase and poaching would dwindle, because community ownership made the illegal killing feel like stealing from the neighbors. And it has worked. Community conservancies now control almost 20 percent of Namibia — 44 percent of the country enjoys some form of conservation protection — and wildlife numbers have soared. The mountain zebra population, for instance, has increased to 27,000 from 1,000 in 1982. Elephants, gunned down elsewhere for their ivory, have gone to 20,000, up from 15,000 in 1995. Lions, on the brink of extinction from Senegal to Kenya, are increasing in Namibia.

Under an international agreement on trade in endangered species, Namibia can sell hunting rights for as many as five black rhinos per year, though it generally stops at three. The entire trophy fee, in this case $350,000, goes into a trust fund that supports rhino conservation efforts. The fund pays, for instance, to capture rhinos and implant transmitters in their horns, as an anti-poaching measure. Trophy hunting one rhino may thus save many others from being butchered.

Many wildlife groups also support the program because Namibia manages it so carefully. It chooses which individual will be hunted, and wildlife officials go along to make sure the hunter gets the right one. (So much for the romance of the Great White Hunter.) The program targets older males past their breeding prime. They’re typically belligerent individuals that have a territorial tendency to kill females and calves.

So why the uproar this time? Namibia made the mistake of allowing the auction to take place in the United States rather than on its own turf. The outraged response started with a kind of Stephen Colbert bump in October. (“If you love something, set it free,” the comedian declared. “Then, when it has a bit of a head start, open fire.”) And it culminated last week in death threats, including one to the auction-sponsoring Dallas Safari Club promising, “For every rhino you kill, we will kill a member of the club.”

Protecting wildlife is a complicated, expensive and morally imperfect enterprise, often facing insuperable odds. The risk with trophy hunting is twofold: Commodifying an endangered species creates a gray zone in which bad behaviors can seem acceptable, and the public relations disaster this time could hurt Namibia’s entire conservation effort. But so far nothing else matches trophy hunting for paying the bills. For people outraged by this hunt, here’s a better way to deal with it: Go to Namibia. Visit the conservancies, spend your money and have one of the great wildlife experiences of your life. You will see that this country is doing grand, ambitious things for conservation. And you may come away wondering whether Americans, who struggle to live with species as treacherous as, say, the prairie dog, should really be telling Namibians how to run their wildlife.

January 18, 2014

How Tibetans Handle Thin Air

Everything’s black and white because it’s so damned hard to breathe up here. A Tibetan landscape, from a 1938 German expedition (Photo: Ernst Schäfer)

When I was trekking in the Himalayas on an assignment some years ago, I was dismayed by how nimble the locals seemed at high altitude, and how plodding I felt by comparison. But now I have an excuse: They’re EPAS1 is better than the stuff I inherited from my potato-picking lowland Irish ancestors.

This finding, published in this week’s Science, raises a lot of questions: Why aren’t Tibetans world-class marathoners? And is this genetic quirk part of the reason upland Kenyans are? What about the Bakongo people who outpaced me above 16,000 feet in Uganda’s Mountains of the Moon? Is there a genetic factor there, too. Or am I just a wuss?

Here’s the report from Cian O’Luanaigh in The Guardian.

A gene that controls red blood cell production evolved quickly to enable Tibetans to tolerate high altitudes, a study suggests. The finding could lead researchers to new genes controlling oxygen metabolism in the body.

An international team of researchers compared the DNA of 50 Tibetans with that of 40 Han Chinese and found 34 mutations that have become more common in Tibetans in the 2,750 years since the populations split. More than half of these changes are related to oxygen metabolism.

The researchers looked at specific genes responsible for high-altitude adaptation in Tibetans. “By identifying genes with mutations that are very common in Tibetans, but very rare in lowland populations we can identify genes that have been under natural selection in the Tibetan population,” said Professor Rasmus Nielsen of the University of California Berkeley, who took part in the study. “We found a list of 20 genes showing evidence for selection in Tibet – but one stood out: EPAS1.”

The gene, which codes for a protein involved in responding to falling oxygen levels and is associated with improved athletic performance in endurance athletes, seems to be the key to Tibetan adaptation to life at high altitude. A mutation in the gene that is thought to affect red blood cell production was present in only 9% of the Han population, but was found in 87% of the Tibetan population.

“It is the fastest change in the frequency of a mutation described in humans,” said Professor Nielsen.

There is 40% less oxygen in the air on the 4,000m high Tibetan plateau than at sea level.

Read the rest of the article here.

Tonight, You Sleep With The Starving Pigs

Nothing like a colorful murder with Saturday morning breakfast (ah, the bacon and eggs). Here’s the report from Claudio Lavanga at NBC News:

An Italian mobster fed a rival gangster to starving pigs — and then marveled at how the victim screamed and how the swine gorged themselves, police say.

The gruesome tale — right out the movie “Hannibal” — came to light when police released a wiretapped phone call by Simone Pepe, a member of the ‘Ndrangheta, the most powerful and violent of Italy’s four Mafias.

The caller recounts how he used an iron bar to beat Francesco Raccosta, a member of another family in the Calabrian region, and then threw him into a sty.

“It was so satisfying hearing him scream … mamma mia, he could scream!” he said, adding that there wasn’t “a thing left” after the feeding frenzy.

“People say sometimes they [the pigs] leave something,” he added.

“In the end there was nothing left…those pigs could certainly eat.”

Pepe, 24, who was allegedly trying to avenge the murder of a mob boss, was later arrested last week during a crackdown on the Mafia. Raccosta’s body hasn’t been found since he went missing last year.

Here’s how a Polish newspaper played the story, with a wonderful sense of editorial discretion:

This Week’s Cool Green Science News Roundup

Here’s this weeks roundup of interesting stories on wildlife and the environment, from TNC’s Cool Green Science Blog:

Wildlife

When sharks use twitter. (New Yorker)

Big predators in big trouble & the cascading effects. (Conservation Bytes)

A spinner dolphin megapod – a congregation of 3000 – 5000 animals — is captured on film for the first time. (Focusing on Wildlife)

Having friends for dinner. Literally. Nat Geo features five animal cannibals. (Nat Geo)

Darren Naish — who else?– has everything you always wanted to know about North America’s freaky vole species. (Tet Zoo)

Conservation Research

When sharks come back from the dead: Shark species thought to be extinct shows up in fish market. (Scientific American)

EZ Pass for fish: technology + collaboration = better data? (EcoRI/MA)

Old trees pack on the pounds: Meta-study in Nature, reported on NPR.

Nature or nurture? Parenting behavior of the white-throated sparrow has been linked to a variation in genome. (eScience Commons – article in PNAS)

How can the open-data movement up its game? Try better standardization of data formats & improved reliability. (SciDevNet)

Climate Change

Underestimating global warming: gaps in Arctic temperature data lead scientists and public astray. (Mongabay)

One Palau reef system seems to thrive in acid conditions. Is it the corals or the location? (American Geophysical Union)

Science Communication

Scott Klein says journalists who don’t know how to code are going to get scooped. Science communicators, you’re next. (Nieman Journalism Lab)

Unleash the scientist/narrator hybrids! A great walk through the state-of-play on what we know works in science communications. (The Science Shill)

Is simplicity in science communcations really better? Really? (Science Unicorn)

Ten tips for tweeting that scientific conference. (ProfHacker)

The Human Dimension

FAO offering gender and climate-smart agriculture webinars. (FAO)

Extreme weather, biodiversity loss, and water crises rank among the top environmental risks; food crises and pandemics top social category. (World Economic Forum Report & press conference)

What’s up with That?

Farmbots? Government officials in the UK say robot farmers are the future of agriculture. (The Guardian)

80-year old snake venom can still kill, but that’s a good thing for scientists researching medicine. (Not Exactly Rocket Science)

Why drones might be bad for outdoors/conservation ethics. (Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel)

- See more at: http://blog.nature.org/science/2014/01/17/the-cooler-tweeting-sharks-animal-cannibals-farmbots-more/#sthash.NvyWsQqx.dpuf

January 17, 2014

Shark Cull: Australian Politicians Pledge to Round up Usual Suspects

(Photo: Julian Cohen/Getty Images)

On a Saturday morning six weeks ago, Chris Boyd, a 35-year-old father of two, was surfing the break off Gracetown in Western Australia. A shark, presumed to be a great white, bounced off the board of a nearby surfer first, before tearing into Boyd. “The shark bit him and held him for about a minute,” said another surfer, who witnessed the attack from the beach. “He was dead before the shark let go.”

It was the third fatal shark attack on a surfer at Gracetown in the past decade, and the seventh fatality from a shark attack in just three years in Western Australia. Predictably, local politicians reacted by pushing for immediate action on a shark mitigation scheme first proposed in September 2012.

Their plan, due to go into effect this month, calls for placing drumlines—buoys rigged with large baited hooks—a little more than a half mile off popular beaches, at an immediate cost of about U.S. $900,000. The same amount would go to fishermen hired to track and kill sharks more than three meters, about 10 feet, in length.

Critics immediately labeled it a and said it would take a heavy bycatch toll on dolphins and other marine species drawn to the hooks. Four thousand people attended a beachfront protest, and twice as many signed a petition addressed to Colin Barnett, premier of the state of Western Australia and chief instigator of the proposal.

The mother of a 21-year-old shark attack victim has called for others to mount a legal challenge to Barnett’s plan, which she called “bait and kill.” Paul de Gelder, a former Army diver who lost one arm and one leg in a 2009 shark attack in Sydney Harbor, also objected and delivered a precise account of what happens when top predators vanish: Studies and history, he wrote, have shown “that removing an apex predator from an eco system will systematically affect the whole balance, disrupting the food chains below them.” He noted that humans are among the ultimate victims of “this disrupting ripple effect.” De Gelder concluded that “the ocean is not our back yard swimming pool and we shouldn’t expect it to be one. It’s a wondrous, beautiful, dangerous place that provides our planet with all life.”

In late December, Western Australia deployed one sensible measure to help swimmers feel safe: It placed transmitters in 326 larger sharks, mostly tigers and great whites, which automatically announce their presence via Twitter whenever they pass receivers placed strategically along beaches.

“Fisheries advise 4m White shark sighted 4 nautical miles north of the west end of Rottnest Island at: 1240 pm today,” said one such tweet, earlier this week. More practically, the same Twitter feed alerts swimmers to the common hazards they are far more likely to encounter, for instance: “Two people have already left the beach in ambulances with possible spinal injuries. Please take extra care body surfing today.”

So, will Barnett’s drumline plan actually make swimmers any safer? At the business news site Quartz, journalist Gwynn Guilford put together a detailed analysis of shark attack prevention programs in New Zealand, South Africa and other Australian states. Nets don’t work because they tend to have gaps at top and bottom, with the result, she writes, that “around 40 percent of sharks ensnared in safety nets turn up on the beach side of the net.”

But “there are problems with drumlines too,” she writes. Sharks that have recently eaten may swim right past, or there may not be any bait left to attract them. “One Queensland study found dolphins stealing the bait within 90 seconds of its being placed in the water, on average. For reasons unclear, drumlines also seem lousy at catching bull sharks, a highly aggressive, pack-traveling species known to attack in water as shallow as 1 meter,” she adds. Some critics worry that baited hooks might actually attract more sharks to beach areas.

Guilford concludes that “giant, terrifying sharks are clearly swimming past all of these traps set for them and cruising beneath humans all the time, with the shark control programs none the wiser.” The swimmers are unaware of it, too, she suggests, perhaps “because sharks simply don’t attack people very often.”

So far, Barnett remains publicly committed to his drumline plan. In a 2012 radio interview that angered some critics, he declared, “We will always put the lives and safety of beachgoers ahead of the shark. This is, after all, a fish—let’s keep it in perspective.” More recently, he posed for the cameras with a big hook in hand. It made him look a bit like a button-down wannabe Captain Quint, the shark-obsessed charter skipper in Jaws.

Somebody may need to remind him: That film’s vendetta against sharks also played to the emotions, but did not ultimately end well for anyone—including Quint.

January 16, 2014

And God Said, “Let There Be Squirrel”

(Photo: Stanislav Duben)

Back in 2012, The (UK) Telegraph published the photo above, of a red squirrel being hand-fed in a park in the Czech Republic.

This morning @LouWoodley ripped it, flipped it, and put out the clever mashup below. Very decently, she also tweeted: “Because I feel bad about ripping that squirrel photo, here’s the original by Stanislav Duben“

January 15, 2014

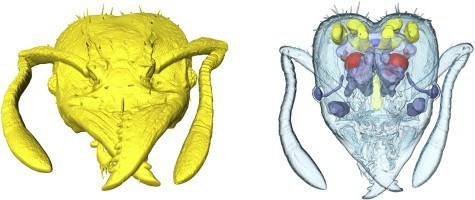

Visualizing the Insides of an Ant’s Head

I’m pretty sure I don’t understand the science here. I just like the image.

This is from a new study in some massively obscure scientific journal. If I am reading it right, it describes a technique for using hydrogen peroxide and a clearing agent to make an ant’s skin transparent. With the help of a confocal laser scanning microscope and fluorescent markers, the result is that you can then see the tiny internal organs in place.

To which I say: Wow.

If you are familiar with the macro photography images of ants heads, like the one I published just the other day, this is like suddenly getting behind the mask, or being invited in to walk around Darth Vader’s brain.

Next thing, we will find ourselves engaging in Socratic dialogues with ants.

Here’s another one, of a leafcutter ant, front view left, side view right:

January 14, 2014

On The Brink of a World Minus the Tooth & Claw

(Photo:Christian Sperka/Panthera)

Everybody knows the haunting tune and those words: “In the jungle, the mighty jungle, the lion sleeps tonight.” The song is a reminder of the power of wilderness and of the awe it can make us feel even across oceans and at the other end of the earth. What West Africa’s lions are facing today, though, is the Big Sleep—that is, extinction.

Researchers who spent six years scouring protected areas in the 11 West African nations where lions were once at home found evidence of fewer than 250 surviving adult lions. Think of it this way: That’s smaller than the high school student body in my small town in New England, distributed across an area longer than the distance from Portland, Maine, to Jacksonville, Fla.

It’s not just West Africa: Lion populations are in dramatic decline across the continent. In Kenya, where they are the symbol of national strength and an essential factor in the tourist economy, biologists have predicted that lions will disappear from the wild within just 15 years. Continent-wide, the rapidly dwindling population is down to about 35,000 lions in 67 isolated pockets.

Until the new study, published in the journal PLOS One, scientists had paid hardly any attention to West Africa’s distinctly different lions, which are more closely related to a remnant subspecies in India than to lions in eastern and southern Africa. They began the research for the new study in 2006, following pug marks through the forest, monitoring camera traps, and occasionally broadcasting a lion’s roaring and listening for a response, almost always in vain. If it was a jungle out there, it was a largely empty one.

The study concludes that West Africa’s lions are in a “catastrophic collapse,” hanging on in just five nations. The news is even worse than that sounds: Almost 90 percent of the lions live in a single trans-frontier population on the shared borders of Benin, Niger, and Burkina Faso, making them highly vulnerable to political upheaval, poaching, or an outbreak of disease. The other surviving lions are in Nigeria and Senegal. In some of these countries, parks exist on paper only, without staff or budget.

The discouraging news about lions came in the same week as another study showing a dramatic decline in almost all of the largest carnivore species worldwide. The authors of that paper, published in Science, looked at 31 predator species and found three-quarters of them are in decline, including leopards, cheetahs, polar bears, tigers, giant otters, and multiple wolf species. The usual killer is loss of habitat from rapidly expanding human populations, combined with persecution by humans.

“Globally, we are losing our large carnivores,” said lead author William Ripple, an ecologist at Oregon State University. “Many of these animals are at risk of extinction, either locally or globally. And, ironically, they are vanishing just as we are learning about their important ecological effects.”

Over the past few decades, scientists have turned up increasing evidence that losing top predators can cause entire ecosystems to collapse, with humans among the potential victims. The 1926 eradication of wolves from Yellowstone National Park, for instance, caused the elks on which they preyed to proliferate, turning the park into a glorified ranch, nibbled down to dirt in many places. The loss of wolves changed not just the look of the land but the quality of streams and the ability of other species to survive there. Biologists refer to those knock-on effects as “a trophic cascade.”

But since reintroduction of the wolves in 1995, Ripple’s research has shown that elk numbers and behavior have changed, aspen and willow have grown back on the banks of creeks, birds and amphibians have returned, and even fish have benefited from the ponds created by beavers.

Trophic cascades are now taking place worldwide, according to the new study. Though people in West Africa kill lions to protect their livestock, for instance, that has allowed olive baboons, a prey species, to expand—causing the strategy to backfire. “Among large mammals,” the new study reports, “baboons pose the greatest threat to livestock and crops and they use many of the same sources of animal protein and plant foods as humans in sub-Saharan Africa. In some areas, baboon raids in agricultural fields require families to keep children out of school so they can help guard planted crops.” That is, they would have been better off with the lions.

Some studies also suggest that loss of predators, and the resulting increase in rodents and other prey species, can put humans at risk of disease. About 60 percent of all human diseases originally came from animals—as do 75 percent of emerging diseases such as Lyme disease and Ebola. The scientific evidence is mixed so far, but in ridding ourselves of the nuisance of predators, humans may turn out to have made a deadly mistake.

The new study sees hope, surprisingly, from Europe, one of the first places on Earth where humans hounded big predators into oblivion. A recent paper by the Zoological Society of London found that lynx, golden jackals, brown bears, and wolverines are all on the rebound there. That success has largely depended on the abandonment of marginal lands by small farmers and herders in Europe. In much of the developing world, the opposite is still happening: Marginal lands and deep forest continue to be overrun by people. A key step to change that is to reduce human population growth, which the study describes as “one of the most insidious threats to carnivores.”

The authors of the new study conclude, “It will probably take a change in both human attitudes and actions to avoid imminent large-carnivore extinctions. A future for these carnivore species and their continued effects on planet Earth’s ecosystems may depend upon it.”

Our survival may hang in the balance.

##

Post Script: Want to do something to help? Learn more about Panthera’s efforts to protect and grow Africa’s remaining lion populations through Project Leonardo.