Richard Conniff's Blog, page 22

May 6, 2016

I’m Really Hoping That’s Not a Bullet Ant on Justin’s Nose

Justin Schmidt being foolish.

I wrote about Justin Schmidt and the “Justin Schmidt Sting Pain Index” in my “intensely pleasurable” book Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time: My Life Doing Dumb Stuff with Animals. Here’s the opening to that chapter:

One morning not long ago, an American entomologist named Justin Schmidt was making his way up the winding road to the Monteverde cloud forest in Costa Rica when he spotted Parachartergus fraternus, social wasps known both for the sculpted architecture of their hive and for the ferocity with which they defend it. This hive was ten feet up a tree, and the tree angled out from an eroded bank over a gorge. Schmidt, who specializes in the study of stinging insects, got out a plastic garbage bag and promptly shinnied up to bag the hive.

He had taken the precaution of putting on his beekeeper’s veil. Undeterred, the angry wasps charged at his face, scootched their hind ends under in midair, and,

from a range of four inches, squirted venom through the veil straight into his eyes. “So there I was ten feet up a tree, holding a bag of live wasps in one hand, basically blinded with pain.” Schmidt slid down the tree like Wile E. Coyote after a tête-à-tête with Road Runner.

And yes, you can buy the book to find out all the gruesome details.

Now Schmidt has come out with a book of his own, The Sting of the Wild, and Newsweek has featured him in an author interview. Here’s an excerpt:

What insect has the most painful sting?

Bullet ants. They are great big black ants that live in South America. They live in colonies [of] about 3,000 adults and are actually very secretive, taking pains not to lead predators back to their nest.

How did you first get stung by one?

It was down in Brazil, and I of course knew about them from very colorful reports of others through the years. They can cause absolute agony for days sometimes. Of course, hearing these reports, I thought, These are obviously something I’ve got to work on.

In Brazil, we happened upon them. My helpers were kind of standing back, and I was trying to collect them. I had half-gallon jars and rubbed talcum powder on the inside so they couldn’t climb out. One of my helpers hacked at the roots [near their nest] so I could collect more. But then they started boiling out. I was picking them up with a long forceps and putting them in jars, but one managed to get a piece of my index finger.

Man, that got my attention.

How much did it hurt?

It was immediate, excruciating pain—it felt like somebody had driven a branding iron into my finger. And when I held up my arm, it was trembling. I couldn’t make it still. The pain came on in these waves. And there’s a crescendo where you’re screaming. Then it would back off, and you can breathe.

But it’s disappointing in the sense that all this pain leaves almost no mark. It does create a hole in your skin because it’s a big stinger—but [not much] swelling, none of the usual markings. For me, the pain went on for about 12 hours, but I got it off quickly, before it could deliver a lot of venom. Somebody who doesn’t know could get hit much harder and be in pain for days.

The good news is that I don’t recall ever seeing a record of somebody dying from it.

So I am really hoping that Justin Schmidt has enough sense of self-preservation not to pose for a photograph with a bullet ant on his nose. But I am not counting on it.

Good News in Dark Times for Russian Leopards & Tigers

Amur leopard (Photo: Julie Larsen Maher/WCS)

By Richard Conniff, for Takepart.com:

Maybe it’s a little perverse of me, but today I’m going to celebrate a piece of good news about leopards and tigers: Russia has just opened its first roadway improvement designed to protect big cats, on its Siberian border with China.

The Narvinskii Pass tunnel runs for about a third of a mile underneath a major migratory route for Amur leopards and tigers. They’re two of the most endangered big cats in the world, and just to give you a sense of the hazard they face from increased highway traffic in the region, check out this dash-cam video (skip to about 30 seconds in).

Until recently, there wasn’t all that much traffic from Vladivostok down to the border, and there was just a gravel road across the Narvinskii Pass. But over the past 15 years, according to Dale Miquelle, a tiger specialist in the region for the Wildlife Conservation Society, a major city has sprung up on the Chinese side of the border, and a busy four-lane highway now crosses through critical leopard and tiger habitat, with the usual highway barriers on the sides. Miquelle credited Sergey Ivanov, chief of staff to Russian President Vladimir Putin, with taking the initiative to protect the leopards.

So what’s so perverse about celebrating that? Well, pretty much all the recent news for tigers and leopards alike has looked grim. A few weeks ago, I reported that

recent claims of a sharp increase in tiger numbers were just wishful thinking—and that tigers have lost 93 percent of their historic range, with a 40 percent decline just since 2010. This week Panthera, the cat conservation group, piled on with a study demonstrating that leopards have lost 75 percent of their historic range. Make that 95 percent in West Africa and up to 87 percent in Asia, where several leopard subspecies totter on the brink of extinction. The study recommends uplisting those subspecies to critically endangered and endangered status and also reclassifying the entire species as vulnerable—meaning in urgent need of conservation—on the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Amur leopard (Photo: Sebastien Bozon/AFP/Getty Images)

The Amur leopard is already considered critically endangered, and while estimates of the total population of the subspecies have more than doubled from just 30 or so individuals earlier in this decade, that’s misleading. As with those wishful tiger estimates, the increase doesn’t mean there are more big cats out there. Instead, it’s mainly a product of better methods of counting highly elusive animals. Back then, said Miquelle, researchers tried to estimate population based on tracks the leopards left in the snow. Camera traps dramatically improved those estimates, but only in the past couple of years have these cameras become available with the battery life and price to make them practical across the Amur leopard’s entire habitat.

Now Russian researchers believe about 50 of these leopards live on their side of the border, and their Chinese counterparts report somewhere between 33 and 42 leopards on their side. But the leopards go back and forth across the border, so researchers on both sides have recently agreed to share their data to produce a combined population estimate. For now, the best guess is that the total population is around 80 leopards.

The importance of the Narvinskii Pass to these travels came to light more than a decade ago. The Wildlife Conservation Society was funding research then by Linda Kerley and the late Mikhail Borisenko of the Zoological Society of London. They were “actually out trying to track and collect scat for DNA analysis and noticed animals moving repeatedly across this ridge,” said Miquelle. “It’s a really good example of how basic scientific research can help define necessary conservation actions. The work was being done for other purposes, but the tunnel was by far the most valuable outcome of that research.”

(Photo: Phoenix Fund)

According to Miquelle, Ivanov heard about the pass and the threat from the proposed highway. He started to focus on the plight of Amur leopards at about the same time that Putin was adopting the Amur tiger as a favorite cause. Plenty of politicians talk, but Ivanov made things happen, designating Land of the Leopard National Park to protect 1,100 square miles of leopard and tiger habitat in the region in 2011. At the time, the possibility of a tunnel running under the park to separate the big cats from highway traffic was just a topic of discussion. Today it’s an accomplished fact, the price tag (not made public so far) be damned.

That’s an example Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi could take to heart—for instance, in the Western Ghats, prime tiger and leopard habitat where bumper-to-bumper car and truck traffic on winding mountain-pass roads interferes with animal movements around the clock. Or in Mumbai, where traffic accidents have killed

May 5, 2016

House of Lost Worlds a “Masterful and Engaging” book

Triceratops by O.C. Marsh.

Great article by Bruce Fellman about visiting the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, and, o.k., also about my “masterful and engaging” book about the Peabody, “House of Lost Worlds”:

Almost 150 years ago—October 22, 1866, to be exact—the fabulously wealthy Massachusetts-born financier and philanthropist George Peabody announced that, because he’d become convinced “of the importance of the natural sciences,” he was committed to giving Yale University $150,000 for “the foundation and maintenance of a MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY.” No doubt his favorite nephew, the up-and-coming vertebrate paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, had more than a little to do with fostering his uncle’s munificence—Peabody, after all, had already bankrolled O.C.’s Yale education and start as a scientist—and no sooner had the gift been announced than Marsh began spearheading an effort to assemble a collection that would “be as extensive,” he said, as those in Berlin and any of the science capitals of the world. A building to house the stuff would come later.

Uncle George, who died in 1869, never got to see the museum that his generosity, “wholely without parallel,” according to Queen Victoria, would eventually make possible, but last week

, on a rainy, chilly Thursday, the Naturalist, his wife Pam, and his granddaughter Stasia, made the trip west to New Haven to introduce our six-year-old mini-naturalist to a place “of life and enjoyment and gaiety and fun,” according to an especially apt description coined by the Peabody’s one-time director, S. Dillon Ripley, in 1984.

In House of Lost Worlds: Dinosaurs, Dynasties, and the Story of Life on Earth (Yale University Press, 2016), veteran science writer Richard Conniff offers …

Go here to read the full article.

Yes, You Can Restore Rivers with Wildlife in Mind

Ran across this brief video in the course of some research. It’s short, and worth a look. I’ll be back with more on this topic soon.

May 3, 2016

Look Who’s Nibbling Away at the World’s “Protected” Habitat

A Toronto uranium company will displace many Selous Game Reserve residents.

My latest for Yale Environment 360:

It’s the saddest truism in wildlife conservation: When politicians announce that they are setting aside precious habitat “in perpetuity,” what they really mean is until somebody else wants the land.

Protected areas now get reopened so often under the pressure of population and economic growth that the trend has spawned an acronym, PADDD, for “protected area downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement.” There’s also a web site, PADDDtracker.org, jointly maintained by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Conservation International.

Abandoned uranium pit, Queensland, Australia

Michael Mascia, a social scientist who recently moved from WWF to Conservation International, developed the PADDD concept in 2011 “to define the problem” worldwide, he said, “and to try to mobilize” attention to it among scientists and ultimately the public.

The effort has begun to pay off, with Julia Marton-Lefèvre, the former director general of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, raising the issue in the journal Science. Noting the 52-percent decline in worldwide bird, mammal, and other wildlife populations since 1970, she warned that downgrading and delisting protected land “threaten the ability of societies to address climate change, food and energy security needs, and sustainability.”

The issue is timely now in part because of the goal, under the 168-nation Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), to extend protection to 17 percent of the earth’s terrestrial and inland water areas by 2020. That means governments need to set aside an additional area more than three times the size of Texas, and do it in the right habitats and on a short timeline. But progress has stalled in recent years at about 15.4 percent, and PADDDs are one reason.

Over the past century, by Mascia’s calculation, downgrading and delisting events have affected an estimated 194,400 square miles of habitat in 57 countries. That’s an area larger than the state of California. According to a 2014 study, four countries that would otherwise already have met their CBD goals — Namibia, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda — have failed to do so only because of PADDD events.

One episode in Kenya suggests just how badly wrong these events can go. The Mau Forest Reserve was until recently an intact montane forest at the heart of the Great Rift Valley, and a sort of “natural water tower” for the spectacular lakes there and for the entire nation. But since the 1990s, the government has presided over the destruction of large portions of the forest, with land titles and logging concessions often handed out to relatives of president Daniel Arap Moi, who left office in 2002. The continuing controversy has resulted in forced evictions, and it has imperiled the water supply to downstream communities and to eight wildlife areas, including the Masai Mara and the Serengeti.

The push to monitor PADDD has also revealed unexpected instances of backsliding. Brazil, for instance, was until recently a leader in designating protected areas. In the first decade of this century, it set aside 74 percent of all land protected worldwide, according to a new study in the journal Biological Conservation, and that expansion cut deforestation in Amazonian rainforests by 37 percent over a single two-year period.

But when lead author Shalynn Pack, at the University of Maryland, looked more closely, she found 67 enacted and 60 proposed PADDD events, the vast majority of them since 2005 and in the Amazon. Hydropower projects and human settlement were the usual causes. In addition, the study had to omit another 76 probable PADDDS for mining, because of inadequate data.

Tracking such events has also made it clear that development doesn’t just target remote and relatively minor corners of protected habitat, though that would be bad enough. Commercial interests at times go after some of the most celebrated monuments on the planet and in some of the most prosperous nations. “One of the things we can say from our work is that this is not a developing country problem,” said Mascia, “it’s not a poor country problem. It’s a global problem.”

In New Zealand, for instance, Mount Aspiring National Park is a World Heritage Site and one of the country’s main tourist attractions. But in 2009, a confidential document surfaced in which government officials recommended opening up roughly 20 percent of the park for mining of rare earth minerals to supply the electronics industry. Prime Minister John Key argued that any mining would be surgical. (Only, replied conservationists, if your idea of surgery includes open-pit mining.) The plan, which would also have downgraded more than 40 other New Zealand protected areas, appears now to be dead. But that may last only until the next spike in commodity prices.

The price of uranium is also the only thing holding up a mining project in Tanzania’s Selous Game Reserve, another World Heritage Site. UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee actually approved a government move to modify the reserve so the 77 square-mile project site, formerly part of the tourist circuit, will now be officially outside the protected area. Bizarrely, the same UNESCO committee later added the Selous to its list of endangered World Heritage sites. In addition to uranium ore, the mine is scheduled to produce at least 60 million tons of radioactive and poisonous wastes, with no practical means of containment.

A plan for Uranium One, a multinational mining company headquartered in Toronto, to commit $800,000 to anti-poaching work in the Selous, a notorious elephant killing ground, has stalled, and the government has made no attempt to mitigate the loss of habitat by adding to protected areas elsewhere. Nor would it mitigate another proposed project that would run a commercial highway through the Serengeti.

Officials in the Democratic Republic of the Congo likewise opened up their best known World Heritage Site, Virunga National Park, to oil exploration. Soco, a British company, faced global protest and returned its permit to the government last year — but only after completing seismic testing and filing a report, secret so far, on whether exploratory drilling would be practical in the park. The project heightened tensions with park officials in a region already ravaged by private armies, according to a conservation scientist working in the region, who added, “The eastern DRC is a powder keg, with so many factions, and this was literally throwing oil on the fire.”

Cataloguing PADDD events won’t necessarily stop the destructive encroachments, where commercial interests are powerful enough, or willing to pay to get their way, and where government officials are weak. But because each site is different, with its own nuances, and because “people have such strong emotions around protected areas,” Mascia said, he has focused PADDDtracker and related efforts simply on collecting data for other researchers, government agencies, and citizens groups to work with.

“Protected area downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement is not necessarily a bad thing,” he added. “We see changes in protected areas in response to market forces and industrial-scale resource extraction, but also for local land claims, to redress past injustices, and in response to local needs.” Park managers themselves sometimes want to adjust their borders to benefit wildlife. “The science has evolved and become more sophisticated over time. Where we put parks on the map 50 or 100 years ago may not be the best place today,” Mascia said.

The experience in Namibia suggests the complicated nature of tracking and making sense of these developments: According to PADDDtracker, it downsized a 1,300-square mile game reserve in 1947. But it did so in response to land claims by the indigenous community. Moreover, since winning independence from South Africa in 1990, Namibia has extended community-management with an emphasis on wildlife to almost 20 percent of its land area, in addition to another 17 percent in national parks. That approach has helped make it one of the few countries in sub-Saharan Africa where wildlife populations are actually increasing.

Though the combined effect may fall short of E.O. Wilson’s recent proposal to set aside half the earth for nature, Mascia noted that some other nations also undertake significant conservation efforts that aren’t in official “protected areas” and yet cover a large portion of the landscape — for instance, with community forestry in Nepal, or with payment for ecosystem services programs in Ecuador, and indigenous territories in Ecuador, Bolivia, and Brazil. “So we may be closer to 50 percent than we would realize” if we focus only on protected areas, he said.

But PADDD accounting needs to become standard practice in any case, according to a 2015 study co-authored by Mascia, if only to make sense of changes in habitat and avoid perverse outcomes at a time when huge payouts under conservation initiatives like the United Nations’ REDD+ program can depend on whether a country successfully maintains forests, reduces carbon emissions, and protects biodiversity. That is, no one wants to be paying for forest preservation in one part of the country if PADDD events are leading to logging of forests in another part. That study urged public and private sector banks, extractive industries, and other groups to develop standards that address these events.

The ultimate purpose of tracking events like the ones in her Brazilian study, added Pack of the University of Maryland, is “not to be antagonists. We want to be working with governments rather than against them.” That can mean simply alerting them to the extent of changes that might otherwise pass unnoticed.

It could also mean pushing for laws governing the downgrading or delisting of protected areas, just as there are laws governing their creation. The requirements before any such event, she said, should include environmental and social impact studies, compensatory measures, and public consultation, with maps and other visual representations, and plain-language explanation of the proposed changes.

The other goal, said Pack, “is to raise public awareness that parks are not permanent, that they need public and political support to survive.” Without that, the natural areas we expect to pass down intact to future generations may instead end up “vulnerable to legal changes that leave them smaller, weaker, or non-existent,” she said.

May 2, 2016

The Scientific Daredevils Who Created a National Treasure at Yale

O.C. Marsh (center) with Yale College Scientific Expedition of 1872

By Beth Py-Lieberman

Smithsonianmag.com

For the past few decades, Richard Conniff has turned his story-telling talents into a kind of one-man industry with copious magazine articles published not only in Smithsonian, but National Geographic, the New York Times, The Atlantic and other prestigious publications. And from his nine books, including Swimming with Piranhas at Feeding Time, The Ape in Corner Office and The Natural History of the Rich, he’s earned his credentials as a passionate observer of the peculiar behaviors of animals, and humans.

For his tenth book, Conniff was asked by Yale University Press to tell the story of the Peabody Museum of Natural History in honor of its 150th anniversary.

Naturally, such a corporate undertaking was met with a degree of journalistic skepticism: “I was a little hesitant at first because I didn’t think I could find a great story or a great narrative arc in one museum.” But then the prize-winning science writer starting digging into the backstory of the New Haven, Connecticut, establishment and what tumbled forth included scandals, adventure, ferocious feuds and some of the wildest, or deranged, derring-do of the scientific world.

On the occasion of the publication of Conniff’s new book House of Lost Worlds: Dinosaurs, Dynasties and the Story of Life on Earth, we sat down to discuss the Peabody Museum—the wellspring of some the most distinguished scholarship of our times.

What was the spark that really got you going on this entire project?

I began with John Ostrom and his discovery of the active, agile, fast dinosaurs in the 1960s and the beginning of the dinosaur revolution. His life sort of runs right up through the discovery that modern birds are just

living dinosaurs. That was really exciting stuff because he was the guy that really sparked all the things that are in the film, Jurassic Park. So that caused me to think, yeah, there might be a book in this after all. Then I went back and I started to dig.

John Ostrom (center) and his Wyoming field crew in 1962. (Courtesy of Karen Ostrom )

Recently, for the New York Times, you wrote about a declining appreciation for the natural history museum and its collections: “These museums play a critical role in protecting what’s left of the natural world, in part because they often combine biological and botanical knowledge with broad anthropological experience.” What would you recommend to improve the standing of natural history museums in our country and to improve the political will to embrace them?

I would say that the public does appreciate them on some level. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History gets 7.3 million visitors a year. The American Museum of Natural History in New York gets five million. Everybody goes to these places when they’re kids and the visits form sort of a critical stage in their realization of their place in the world and in cultures. But the people who make decisions about where to spend their government money, for instance, government support like the NSF, the National Science Foundation, which recently suspended its support, and people who are doing philanthropic giving, they don’t see the natural history museums as places where exciting things are happening. I think that the museums themselves have to step forward and make that case and they have to demonstrate how critical their collections are to our thinking about climate change, about mass extinctions, about species invasions and about our own modern great age of discovery. There’s really good stuff to be found there, good stories to be told and people need to hear them.

Yes, the Natural Museum in any town or community is really the wellspring of American scientific research. It’s a tool for showing rather than telling. Give me an example of how well that can work?

There was a kid growing up in New Haven. His name was Paul MacCready. And he got obsessed, the way kids do, with winged insects. So he learned all of their scientific names. He collected them. He pinned out butterflies. He did all that stuff. And he went to the Peabody Museum. Later in life, he became less interested in the natural world and more interested in flight. And he developed the first successful human-powered aircraft capable of controlled and sustained flight—the Gossamer Condor. Then a few years later he developed the first human-powered aircraft to successfully cross the English Channel—the Gossamer Albatross. He was a great hero. This was in the late 1970s. Now, when he came back to visit the Peabody Museum, the one thing he mentioned—he mentioned it casually—was this diorama that he vividly remembered from his youth. It was an image of a dragonfly…a big dragonfly, on the wing over this green body of water. The weird thing is that the Peabody had removed that diorama. But when the archivist there, Barbara Narendra heard about this she went and saved that dragonfly. So they have this chunk of stone basically with that image on it. And it’s just this kind of a stark reminder that the most trivial of things in a museum like this can have profound effects on people’s lives.

Scientists have a tendency sometimes towards petty squabbles. But out of conflict, knowledge is sometimes increased. How is knowledge enhanced by these scientific battles?

Well yes, the one that took place at the Peabody Museum between O. C. Marsh, the paleontologist in the 19th century and his friend—who became his arch rival—Edward Drinker Cope, at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. These two started out hunting for fossils together in the rain in southern New Jersey. It’s not clear how the feud began. They were friends in the 1860s. But by 1872, there were articles in the press referring to this ferocious conflict between them. So competing with each other, they were both driven to collect as much as they could as fast as they could. And that was both good and bad for science because they collected some of the most famous dinosaurs in the world. Take O. C. Marsh at the Peabody Museum, he discovered Brontosaurus, he discovered Stegosaurus, Triceratops, all kinds of dinosaurs that every school kid knows about now. And Edward Drinker Cope was making similar discoveries. Now, the downside was that they raced to discover things and define new species at such a rate that they often described things that later scientists had to spend much of their lives untangling; because there were a lot of species that were given multiple names and that sort of thing, so good and bad sides.

O.S. Marsh, 1860 (Division of Vertebrate Paleontology Archives, Yale Peabody Museum )

The skull of a Torosaurus, c. 1914, collected by O.C. Marsh (Division of Vertebrate Paleontology, Yale Peabody Museum)

Women who have wished to pursue the natural sciences have had a hard row to hoe, but a handful prevailed. Who among them do you most admire and why?

This is one of things that was on my mind regularly while I was doing both my previous book, The Species Seekers, and this book—how ruthlessly women were excluded from scientific discovery. So there was this woman—this is 20th century. But there was this woman—named Grace Pickford and she got a job at Yale and affiliated with the Peabody Museum basically because her husband in the 1920s was G. Evelyn Hutchinson, the “Father of Modern Ecology.” And she was a marine biologist. But she was never made a full staff member. Rather, she was never made a faculty member. She was never promoted in proper order until 1968 when she was on the brink of retirement and they finally made her a professor. But all this time, she had been doing great discoveries of the endocrinology of obscure fish and invertebrates and discovering new species—and the NSF funded her. She had a grant every year. And the other thing about her was that she and her husband eventually divorced and she was not…she did not present herself in a conventional female way. So, in fact, she wore a jacket and tie and sometimes a fedora. By the end of her life she was under pressure to leave and she was given tenure but on the condition that she had to teach the introductory science class. And here was this highly gifted woman, older and not conventional, in her appearance, and in the back of the room these prep school kind of Yalies would be snickering at her, and ridiculing her.

A museum artist’s original drawing of the skull of Triceratops prorsus, discovered by John Bell Hatcher and named by O.C. Marsh. (Department of Paleobiology, NMNH/SI)

Is there a champion that you came across in your work on this book that somehow missed honor and fame that you would like to see recognized?

You bet. His name was John Bell Hatcher. Nobody has heard of him, but he was this fiercely independent guy who he started out in college paying for his college—I forget exactly where, but he was paying for his college—by mining coal. And, doing that, he discovered paleontological specimens. He transferred as a freshman to Yale, showed his specimens to O. C. Marsh, who saw genius and quickly put him to work. And then after Hatcher graduated from Yale he became an assistant and a field researcher for O. C. Marsh. He traveled all over the West, often alone, and discovered and moved massive blocks containing fossils and somehow extricated them. He removed one that weighed a ton—by himself. And fossils are fragile. He got them back pretty much intact. So he was a bit of a miracle worker that way.

I’ll give you an instance. He noticed that—I mean, it wasn’t just about big fossils, he also wanted the small mammal fossils, microfossils like the jaws and teeth of little rodents. And he noticed that—harvester ants collected them and used them as building material for their nests. He started bringing harvester ants with him. Harvester ants, by the way, are really bad stingers. He took the harvester ants with him to promising sites and he would seed these sites with the ants, and then come back in a year or two and see what they’d done, then collect their work. But in any case, from one nest he collected 300 of these fossils. He was a genius.

He’s the one who actually found Triceratops and Torosaurus and many, many, many other creatures. And he was worked to the bone. He was underpaid by O. C. Marsh and always paid late. He actually paid for his science much of the time by gambling. He was a really good poker player. He was poker faced as they come. He looked like Dudley Do-Right in his 10 gallon hat. And he also…he carried a gun, and knew how to use it in the American west.

I’ll tell you one other story. Hatcher was in Patagonia doing work in the middle of winter. He had to travel 125 miles in the worst weather on horseback alone. At one point he was about to get on his horse and he had to bend down and fix something and the horse jerked its head up and ripped his scalp half off his skull. And he’s alone in the middle of nowhere in wind and cold. He pasted his scalp back across his skull, wrapped kerchiefs around it, pulled his 10-gallon hat tight to hold everything together, got back on his horse, rode 25 miles, slept on the ground that night, rode again the next day and the next day until he finally completed this 125 mile trip. And the only reason he was doing it was to make sure that his fossils were being packed right on a ship to New York.

John Bell Hatcher, 1885 (Yale Peabody Museum Archives)

I keep thinking that 19th-century men are just stronger, or at least more stoic, than we moderns are.

Yes, I have to say that his wife, who spent much of her time alone and was the mother of four children, wasn’t so bad off either in terms of strength and stoicism.

New Haven’s Peabody Museum has been called the “Sistine Chapel of Evolution.” Of all these scientists that have haunted these halls, who among them best walks in the footsteps of Charles Darwin and why?

Well, John Ostrom. I mean, John Ostrom, he found this Deinonychus in Montana. And the Deinonychus had this five-inch-long curved claw. From that and from excavating entire fossil skeletons, Ostrom deduced that dinosaurs could be fast, they could be agile, they could be smart; that they weren’t the plodding, swamp bound monsters of 1950s myth. And that began a dinosaur renaissance. That’s why every kid today is obsessed with dinosaurs, dreams about dinosaurs, plays with dinosaurs, reads about dinosaurs. And then his Deinonychus became the model for Velociraptors in Jurassic Park, basically because Michael Crichton, the novelist, thought Velociraptor sounded sexier than Deinonychus. But he did his interviewing research with John Ostrom.

And the other story that I like about Ostrom—in fact, this is really the story that sold me on the book—he was in a museum in the Netherlands in 1970 looking at a specimen that was supposed to be a Pterosaur, like a Pterodactyl. And he looked at it after awhile and he noticed feathers in the stone and he realized it wasn’t a Pterosaur at all; it was an Archaeopteryx, the sort of primal bird from 160 million years ago. In fact it was only the fourth of those known in the world. So he had a crisis of conscience because if he told—he needed to take the specimen home to New Haven to study, and if he told the director, the director of the Netherlands museum might say: “Well, that’s suddenly precious so I can’t let you have it.”

Yet he was, as one of his students described him to me, a squeaking honest man. And so he blurted it out that this was, in fact, Archaeopteryx. And the director snatched the specimen away from him and ran out of the room. John Ostrom was left in despair. But a few moments later the director came back with a shoebox wrapped in string and handed this precious thing to him. With great pride he said: “You have made our museum famous.” So Ostrom left that day full of excitement and anticipation. But he had to stop in the bathroom on the way home; and afterwards he was walking along and thinking about all these things he could discover because of his fossil and suddenly he realized he was empty-handed. He had to race back and collect this thing from a sink in a public toilet. He clutched it to his breast, carried it back to his hotel and all the way back to New Haven and thus saved the dinosaurs’ future…the future for dinosaurs.

So the thing that was important about that fossil was—that Archaeopteryx was—that he saw these distinct similarities between Archaeopteryx and his Deinonychus that is between a bird and dinosaurs. And that link that started in 1970 led to our present day awareness that birds are really just living dinosaurs. So John Ostrom is a very modest guy. You wouldn’t look at him twice if you saw him in the hallways. He’s also one of my heroes.

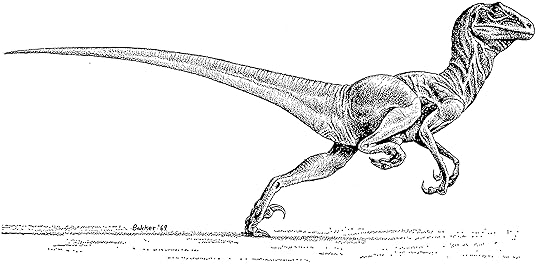

John Ostrom deduced that dinosaurs could be fast, agile and smart and ended the notion that they were plodding, swamp bound monsters, as this 1969 illustration suggests. (Illustration by Robert Bakker, Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History)

A Google search of the name of the great American philanthropist and businessman George Peabody turns up more than 11 million results, including citations for “The Simpsons.” He established the Yale Peabody Museum and numerous other institutions in the U.S. and in London. What is his story?

George Peabody was an interesting character because he had to start supporting his family from when he was, I think, the age of 16, maybe a little younger, because his father died. So at first he was just a shopkeeper in Massachusetts. He improved the shop business, obviously. And then he moved on to Baltimore to a much larger importing business. He eventually became a merchant banker based in London. And he did this thing that was newly possible in the 19th century, really for the first time, which was to build up a massive fortune in a single lifetime. And then he did this thing that was even more radical which was to give it all away.

Feathered Deinonychus(Nobumichi Tamura, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History)

No one had done that before?

Not to this extent. George Peabody was really the father of modern philanthropy. So what motivated him, what drove him, kind of what tormented him, was that he had had no education. And he really felt painfully this lack of an education, especially in London in the 19th century. Being an American and traveling in the upper echelon of society, you come in for a fair amount of ridicule or faintly disguised disdain. So, anyway, he gave his money to education. He gave it to the places where he had lived, to Baltimore, to a couple of towns in Massachusetts, one of them is now named Peabody. He gave his money also to housing for the working poor who had come into London during the Industrial Revolution. He gave his money to good causes. And then in the 1860s he was so ecstatic that his nephews—not so much his nieces, but his nephews—were getting an education. So he funded the Yale Peabody Museum in 1866. And he also funded a Peabody Museum of Anthropology at Harvard. And those two institutions are a pretty good legacy on their own but he also has these other legacies distributed all over this country and the UK. And the people that you think of as the great philanthropists, like Andrew Carnegie, well, they were all following in his footsteps.

May 1, 2016

Animal Music Monday: Chopin’s “Minute Waltz”

This lively little tune by the Polish composer Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) is widely known as “The Minute Waltz” (meaning small waltz, though commonly pronounced to suggest that Chopin meant it to be played that fast). Chopin himself named it Valse du Petit Chien, “Waltz of the little dog.”

Here’s the story. He was living in the 1840s with the French author and feminist George Sand (Amandine Aurore Lucille Dupin). They were supposedly sitting around one time when her dog, Marquis, began to run in circles, chasing his tail. Sand then challenged Chopin to write a musical piece capturing that crazed energy and Chopin did so on the spot.

The story may well be apocryphal.

But here’s another tune Chopin wrote about Marquis, the 40-second “Galop Marquis.”

April 30, 2016

The Secret to Helping Conservatives Care About Climate Change

(Photo: George Rose/Getty Images)

My latest for Takepart.com:

Environmentalists are, by and large, idiots when it comes to talking with the people who disagree with us. We go on (and on) about fairness, about injustice, about caring. We are outraged. We are gloomy. Everything is going extinct, and it’s because of that company you work for, that pickup truck you drive, or that hamburger you’re eating. And, sure, everything does seem to be going extinct, and there is plenty of blame to go around. But people just tune us out.

Is there a better way? A way that might persuade ranchers to think differently about wolves, for instance? Or that might persuade conservatives to acknowledge the reality of climate change? Is there a way that might intrigue our political counterparts instead of just antagonizing them?

The good news, according to a new study in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, is that conservatives might not at heart have any real issue with protecting the environment. The bad news? What they are rejecting is us, our tone and tenor, and our self-righteous way of always framing environmental questions “in ideological and moral terms that hold greater appeal for liberals and egalitarians.” That may help affirm our in-group status as environmentalists. But it almost obliges our counterparts

to reject our ideas as a way of asserting their in-group credentials as conservatives.

Lead author Christopher Wolsko, a social psychologist at Oregon State University–Cascades, set out to test what happens when you frame the same issues in conservative terms instead. First Wolsko and his coauthors characterized the political perspective of test subjects based on their responses to a few questions about capital punishment, abortion, gun control, socialized health care, and same-sex marriage.

Then they tested their response to an issue presented with two distinctly different kinds of “moral framing.” A conservative version might talk about “love of country,” “joining the fight,” “taking pride,” “performing one’s civic duty,” and “honoring all of Creation.” The liberal counterpart might instead emphasize “love for all of humanity,” “fair access to a sustainable environment,” and “preventing the suffering of all life forms.”

And, duh, the conservatives liked the first version better. More important, it also made them more likely to be concerned about climate change and even to donate a portion of the compensation they received for participating in the study to a randomly selected environmental group.

After reading the study, one temptation might be to sprinkle your pitch with conservative buzzwords when talking with conservatives. The study notes that “moral judgments are strongly driven by automatic processes” and that “as little as two sentences pronouncing the patriotic significance of being pro-environmental can have substantial attitudinal and behavioral effects.” Even adding a peripheral cue, such as an American flag in the foreground of a scenic landscape, can help induce that change.

But that kind of cynical spin is what has gotten us into our present polarized political standoff, said Wolsko, with everybody “narrow-casting” their message “and people all hearing what they want to hear from whom they want to hear it.” A better approach, he said, is to make a sincere effort to look at an issue from your adversary’s perspective. “It’s about inclusivity, broadening our values, not just persuading conservatives that they need to be more like liberals in terms of the things they value,” he said.

Just as an experiment, I asked an environmentalist I know how he might feel about presenting an issue in terms of obeying authority, defending the purity of nature, and demonstrating patriotism. Sounds like the Nazis, he said. But honestly, is it that much of a stretch to think about environmental issues in terms of respect for good leadership or the sacredness of nature or love of country? Are the things conservatives and liberals want always so different?

The whole discussion put me in mind of a phone call an environmentalist lawyer named Fred Krupp made in the fall of 1988 to a conservative multimillionaire named Boyden Gray, who was about to become White House counsel to the then president-elect, George H.W. Bush. Bush had pledged to become the “environmental president,” to general ridicule from environmentalists. Krupp, president of the Environmental Defense Fund, not only took him at his word but also laid out a conservative way to do it.

The pressing issue then was acid rain, mainly produced by power plant emissions. It was causing massive damage to forests and lakes and human health. But the standard remedy—government regulators ordering utilities to install scrubbers—was likely to cost $100 million per plant, and it was certain to provoke lawsuits. Instead, said Krupp, why not have the government just put a steadily decreasing cap on the total emissions allowed each year? Then let the utilities figure out on their own how to meet that cap, with the help of free-market “emissions trading.” That is, some companies might choose to install scrubbers immediately and then sell their annual emissions allowance on the open market. Other companies might want to delay the capital expenditure for a few years and meanwhile purchase allowances to cover their excess emissions—but they couldn’t delay indefinitely, because the allowances would just get more expensive as the overall cap decreased.

Many environmentalists were predictably horrified. They accused EDF of proposing “a right to pollute.” But the Bush administration latched on to this capitalist approach, and over the next two decades what became known as cap-and-trade cut acid rain emissions in half, producing huge benefits for the environment and for human health, at a fraction of the predicted cost. Krupp and EDF had committed the environmental heresy of talking to a Republican White House, and in conservative Republican terms, and it worked.

That’s a model the rest of us should keep in mind as we address the many persistent environmental problems that, whether or not we like to admit it, affect all of us, liberals and conservatives alike, as one people.

April 20, 2016

Smarter Farming (and Eating) to Save the World

(Photo: Chris Winsor/Getty Images)

My latest for Takepart.com:

You probably don’t think agricultural intensification could ever be a good thing. And you certainly wouldn’t expect an argument for more of it in a column about wildlife. But here’s the deal: If we don’t figure out how to grow more food on less land, we’re going to have to plow under what little remains of the natural world and turn it into farmland.

And we have to figure it out fast, because there are going to be 10 billion people to feed by mid-century. The way we grow food now, that won’t leave enough room at all for creatures from ants to elephants—or for the plants with which they have coevolved over the history of the Earth.

The answer, according to a lot of agricultural experts, is sustainable intensification. Basically it means growing more food on less land, but doing so with minimal environmental damage. And it’s arguably even more important than the usual conservation strategy of creating national parks and other protected natural areas.

“If we want to save biodiversity in the world,” said G. David Tilman, an ecologist at the University of Minnesota, “the most important thing is not to buy a piece of land and put a fence around it but to help farmers feed their families—and feed other families.” He’s talking mostly about farmers in the developing world, where population growth is highest, the clearing of land most problematic for biodiversity, and the productivity of farmland often dismally low. “If we can’t get higher yields, these people will and should clear more land,” Tilman added. “It is their moral obligation to feed their families.”

So what does sustainable intensification involve? Given that “sustainable” is one of the least meaningful, most overused words in the English language, it’s predictably a controversial issue. For instance, some experts argue that feeding a larger population requires judicious use of genetically modified crops because they yield more food on less land, with fewer environmentally destructive inputs such as pesticides and herbicides. Others protest that GMO crops are almost by definition controlled by large agribusiness at the expense of small farmers. Fields of GMO crops also tend to result in agricultural monocultures with no room for monarch butterflies and other species dependent on the weeds that inevitably occur in conventionally farmed fields.

That, in turn, leads to the debate about whether land sharing (encouraging wildlife on the farm) is the best way forward, or whether we should concentrate instead on land sparing (getting maximum yield from existing farmland so farmers don’t have to expand into natural areas).

One thing that is not debated: Sustainable intensification certainly means that farmers in the developed world need to reduce their catastrophic overuse of fertilizers. The current practice of dumping nitrogen fertilizer on fields and allowing it to run off into nearby rivers and streams kills those water bodies and creates vast “dead zones” where fish and other marine wildlife cannot live.

It should be relatively easy to fix: Farmers in industrial nations like the U.S. now typically add fertilizer before they even plant a crop. “Half of it leaches away, because the plants don’t even have full root systems till two months later,” said Tilman. If they waited instead to fertilize when the plants are a foot tall, they could get the same yield with half the fertilizer. That happened in a 2009 study in China, where overuse of fertilizer is also a problem.

What would it take to get farmers to change fertilizing tactics? In this country, 30 years of hand-wringing about the Gulf Coast “dead zone” has changed nothing. In fact, levels of nitrogen and phosphorous runoff in the Mississippi River have actually increased. U.S. farmers continue to pile on fertilizer basically because they don’t have to pay for the damage they cause downstream—and because we let them. Meanwhile, a regulatory mandate in the European Union has produced a 30 percent reduction in nitrogen use with an equivalent increase in yield. But don’t look to Congress or the U.S. Department of Agriculture for help. Instead, it may take a lawsuit to force a change. The city of Des Moines, Iowa, is now suing to get upstream farmers to pay for polluting city water and imposing major filtration costs.

The sustainable intensification debate has all kinds of implications for the future of life on Earth. You can find out more here and here. Getting more fertilizer to farmers in developing nations is one priority that a casual reader might not expect. You can look into that side of story here. Food waste is another.

I don’t have room here to get into all the changes needed to achieve sustainable intensification. But let’s just leave it with one issue where we can all make a difference. I have to start with a full disclosure: I ate a hamburger for dinner last night. I love hamburgers. But limiting that to, say, one hamburger a month and cutting back on meat consumption in general is the simplest way to free up existing land for food crops. That’s because, under our current system, an incredible 75 percent of all arable land worldwide is now reserved for pastures or crops used in the production of meat. Change that, and we’d never have to plow under another acre of natural habitat anywhere in the world ever again.

April 15, 2016

That Big Rise in Tiger Numbers? It Was a WWF Fantasy.

(Photo: Jim Cook/Getty Images)

My latest for Takepart.com:

Lately, media worldwide have been frothy with happy talk about an unexpected increase in populations of the endangered tiger, with the global count suddenly up from 3,200 to 3,890. The World Wildlife Fund and the Global Tiger Forum reported the result based on a tally of recent counts by government agencies and conservation groups.

The announcement predictably produced headlines everywhere that tiger populations were on the rise for the first time in 100 years. Even National Geographic and the BBC sang along, in tune: “Tiger Numbers Rise for First Time in a Century.”

There was only one problem: The news was a publicity-friendly confection of nonsense and wishful thinking, unsupported by any published science.

Instead, the timing of the announcement had everything to do with politics: It came the day before the scheduled opening of the Asia Ministerial Conference on Tiger Conservation in New Delhi, bringing together scientists and political leaders from 13 nations.

That group has committed its member nations to the daunting (and arguably unrealistic) goal of doubling the population of tigers between 2010 and 2022. With half that time elapsed, WWF Senior Vice President Ginette Hemley apparently meant to kick things off with some good news and a key takeaway message for the conference attendees. “When you have high-level political commitments, it can make all the difference,” she said. “When you have well-protected habitat and you control the poaching, tigers will recover. That’s a pretty simple formula. We know it works.”

At various points, Hemley carefully attributed the results to better counting methods, not to an actual increase in tiger numbers. “The tools we are using now are more precise than they were six years ago,” she told The New York Times. But that nuance got lost along the way, as it was perhaps intended to do. The Times headline: “Number of Tigers in the Wild Is Rising, Wildlife Groups Say.”

WWF did not respond to a request to interview Hemley—a policy person who spends most of her time in Washington, D.C. So for a reality check, I phoned a tiger biologist: John Goodrich

, senior tiger program director for Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization.

Two conservation groups released the tiger population report, he said, but “there aren’t really any scientists connected with it, and we don’t know the sources of the data that they’re basing it on—not yet, and I doubt we will.”

Goodrich called the announcement “misleading,” and he isn’t alone in the sentiment. In a joint statement, Wildlife Conservation Society directors K. Ullas Karanth and Dale Miquelle and University of Oxford zoologist Arjun Gopalaswamy said the surveys are leading to “an illusion of success.”

“Glossing over serious methodological flaws, or weak and incomplete data to generate feel-good ‘news’ is a disservice to conservation,” they stated, “because tigers now occupy only 7 percent of their historic range.”

Tiger numbers suffer from “a lot of hype,” Goodrich said. That’s partly because tigers often live in some of the most remote and difficult terrain in the world. An expedition I participated in found tiger pugmarks at 10,000 feet in the Himalayas of Bhutan, at a time when outside biologists refused to believe Bhutanese reports of high-country tigers.

The Bhutanese later proved it with camera-trap images from 13,450 feet.

Goodrich said the 1999 estimate of a worldwide population of 5,000 to 7,000 tigers was “a guesstimate,” and the 2010 count of 3,200 was also just a guess.

“Now our data are much better,” he said, mainly due to improvements in tiger monitoring, camera trapping, and the complex algorithms for inferring total populations from the reliable data. “But there are still only two countries that have comprehensive surveys of tiger habitat: Nepal and Bhutan,” Goodrich said.

Despite his concerns with the WWF report, Goodrich acknowledged some good news, including increases in tiger populations in the Western Ghats mountain range in India, around Chitwan National Park in Nepal, and at the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Thailand.

There is one statistic Goodrich said really should have dominated the headlines: Since 2010, tiger range—as estimated by scientists—has decreased 40 percent. That is, when they went out and looked carefully at designated tiger habitat, they found almost half the time that no tigers lived there. That’s largely because poaching has simply eliminated tigers from some habitats. (A study early this month found that there’s enough empty habitat left to meet the goal of doubling tiger populations by 2022, if governments could get serious about stopping poaching.)

Vietnam is down from a reported 100 tigers at the turn of the century to just five today, and the Ho Chi Minh City–based Thanh Nien News responded to the WWF announcement by noting with alarm that “some traffickers have taken advantage of the Internet, blatantly advertising tiger parts on Facebook.”

Habitat destruction also continues unabated. The host of the New Delhi conference that wrapped up Thursday was Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the most pro-development, anti-nature prime minister in India’s recent history. He gives lip service to tiger conservation—but with his strong backing, India appears to be going ahead with a road-widening project between the Pench and Kanha Tiger Reserves in central India—the setting for Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book. That decision goes against the conclusion by a Supreme Court–appointed advisory committee that the project would cause “irreparable damage to a critical wildlife habitat.” Modi’s administration is making such choices everywhere.

So much for happy talk and good publicity. What politicians and conservation activists need to be hearing from the entire world is a loud reminder that continuing on our current course will cause tigers to disappear forever from the wild.