Lorin Hochstein's Blog, page 6

November 18, 2024

Reading the Generalized Isolation Level Definitions paper with Alloy

My last few blog posts have been about how I used TLA+ to gain a better understanding of database transaction consistency models. This post will be in the same spirit, but I’ll be using a different modeling tool: Alloy.

Like TLA+, Alloy is a modeling language based on first-order logic. However, Alloy’s syntax is quite different: defining entities in Alloy feels like defining classes in an object-oriented language, including the ability to define subtypes. It has first class support for relations, which makes it very easy to do database-style joins. It also has a very nifty visualization tool, which can help when incrementally defining a model.

I’m going to demonstrate here how to use it to model and visualize database transaction execution histories, based on the paper Generalized Isolation Level Definitions by Atul Adya, Barbara Liskov and Patrick O’Neil. This is a shorter version of Adya’s dissertation work, which is referenced frequently on the Jepsen consistency models pages.

There’s too much detail in the models to cover in this blog post, so I’m just going to touch on some topics. If you’re interested in more details, all of my models are in my https://github.com/lorin/transactions-alloy repository.

Modeling entities in Alloy

Let’s start with a model with the following entiteis:

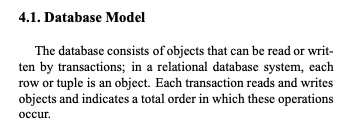

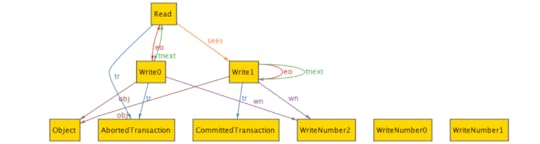

objectstransactions (which can commit or abort)events (read, write, commit, abort)The diagram below shows some of the different entities in our Alloy model of the paper.

You can think of the above like a class diagram, with the arrows indicating parent classes.

Objects and transactionsObjects and transactions are very simple in our model.

sig Object {}abstract sig Transaction {}sig AbortedTransaction, CommittedTransaction extends Transaction {}The word sig is a keyword in Alloy that means signature. Above I’ve defined transactions as abstract, which means that they can only be concretely instantiated by subtypes.

I have two subtypes, one for aborted transactions, one for committed transactions.

Events

Here are the signatures for the different events:

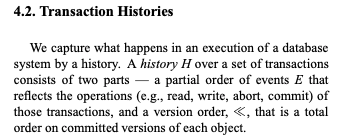

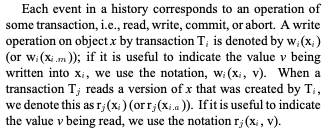

abstract sig Event { tr: Transaction, eo: set Event, // event order (partial ordering of events) tnext: lone Event // next event in the transaction}// Last event in a transactionabstract sig FinalEvent extends Event {}sig Commit extends FinalEvent {}sig Abort extends FinalEvent {}sig Write extends Event { obj: Object, wn : WriteNumber}sig Read extends Event { sees: Write // operation that did the write}The Event signature has three fields:

tr – the transaction associated with the eventeo – an event ordering relationship on eventstnext – the next event in the transactionReads and writes each have additional fielsd.

ReadsA read has one custom field, sees. In our model, a read operation “sees” a specific write operation. We can follow that relationship to identify the object and the value being written.

Writes and write numbers

The Write event signature has two additional fields:

obj – the object being writtenwn – the write numberFollowing Adya, we model the value of a write by a (transaction, write number) pair. Every time we write an object, we increment the write number. For example, if there are multiple writes to object X, the first write has write number 1, the second has write number 2, and so on.

We could model WriteNumber entities as numbers, but we don’t need full-fledged numbers for this behavior. We just need an entity that has an order defined (e.g., it has to have a “first” element, and each element has to have a “next” element). We can use the ordering module to specify an ordering on WriteNumber:

open util/ordering[WriteNumber] as wosig WriteNumber {}VisualizingWe can use the Alloy visualizer to generate a visualization of our model. To do that, we just need to use the run command. Here’s the simplest way to invoke that command:

run {}Here’s what the generated output looks like:

Visualization of a history with the default theme

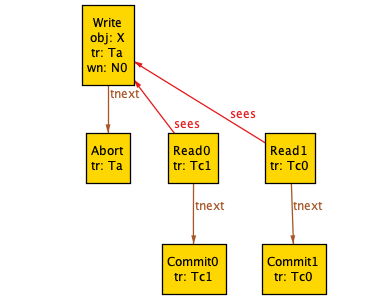

Visualization of a history with the default themeYipe, that’s messy! We can clean this up a lot by configuring the theme in the visualizer. Here’s the same graph, with different theme settings. I renamed several things (e.g., “Ta” instead of “AbortedTransaction”), I had some relationships I didn’t care about (eo), and I showed some relationships as attributes instead of arcs (e.g., tr).

Visualization after customizing the theme

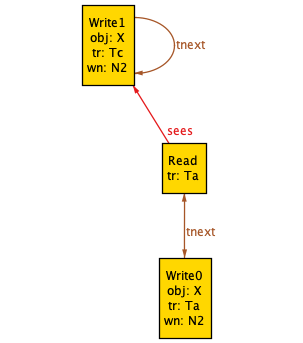

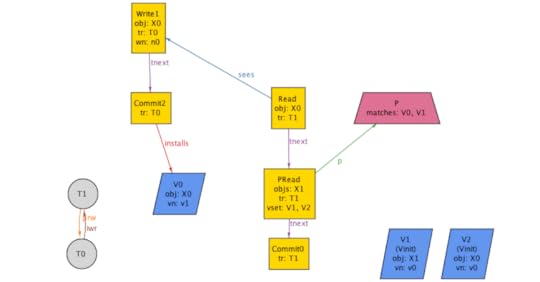

Visualization after customizing the themeThe diagram above shows two transactions (Ta, Tc). Transaction Ta has a read operation (Read) and a write operation (Write0). Transaction Tc has a write operation. (Write1).

Constraining the model with factsThe history above doesn’t make much sense:

tnext is supposed to represent “next event in the transaction”, but in each transaction, tnext has loops in itTa belongs to the set of aborted transactions, but it doesn’t have an abort eventTc belongs to the set of committed transactions, but it doesn’t have a commit eventWe need to add constraints to our model so that it doesn’t generate nonsensical histories. We do this in Alloy by adding facts.

For example, here are some facts:

// helper function that returns set of events associated with a transactionfun events[t : Transaction] : set Event { tr.t}fact "all transactions contain exactly one final event" { all t : Transaction | one events[t] & FinalEvent}fact "nothing comes after a final event" { no FinalEvent.tnext}fact "committed transactions contain a commit" { all t : CommittedTransaction | some Commit & events[t]}fact "aborted transactions contain an abort" { all t : AbortedTransaction | some Abort & events[t]}Now our committed transactions will always have a commit! However, the facts above aren’t sufficient, as this visualization shows:

I won’t repeat all of the facts here, you can see them in the transactions.als file.

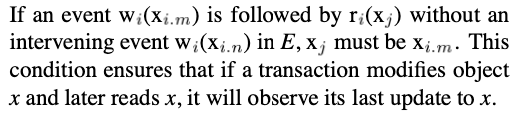

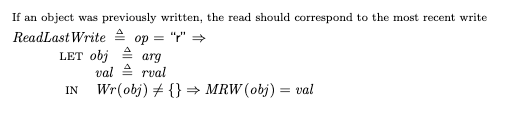

Here’s one last example of a fact, encoded from the Adya paper:

The corresponding fact in my model is:

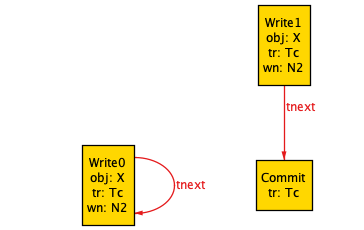

/** * If an event wi (xi:m) is followed by ri (xj) without an intervening event wi (xi:n) in E, xj must be xi:m */fact "transaction must read its own writes" { all T : Transaction, w : T.events & Write, r : T.events & Read | ({ w.obj = r.sees.obj w->r in eo no v : T.events & Write | v.obj = r.sees.obj and (w->v + v->r) in eo } => r.sees = w)}With the facts specified, our generated histories no longer look absurd. Here’s an example:

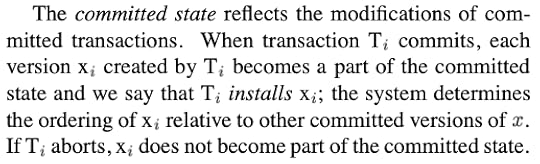

Mind you, this still looks like an incorrect history: we have two transactions (Tc1, Tc0) that commit after reading a write from an aborted transaction (Ta).

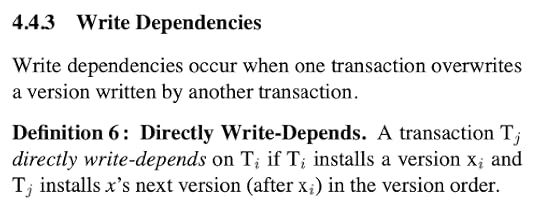

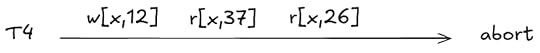

Installed versions

The paper introduces the concept of a version of an object. A version is installed by a committed transaction that contains a write.

I modeled versions like this.

open util/ordering[VersionNumber] as vosig VersionNumber {}// installed (committed) versionssig Version { obj: Object, tr: one CommittedTransaction, vn: VersionNumber}DependenciesOnce we have versions defined, we can model the dependencies that Adya defines in his paper. For example, here’s how I defined the directly write-depends relationship, which Adya calls ww in his diagrams.

fun ww[] : CommittedTransaction -> CommittedTransaction { { disj Ti, Tj : CommittedTransaction | some v1 : installs[Ti], v2 : installs[Tj] | { same_object[v1, v2] v1.tr = Ti v2.tr = Tj next_version[v1] = v2 } }}Visualizing counterexamples

fun ww[] : CommittedTransaction -> CommittedTransaction { { disj Ti, Tj : CommittedTransaction | some v1 : installs[Ti], v2 : installs[Tj] | { same_object[v1, v2] v1.tr = Ti v2.tr = Tj next_version[v1] = v2 } }}Visualizing counterexamplesHere’s a final visualizing example of visualizations. The paper A Critique of ANSI SQL Isolation Levels by Berenson et al. provides some formal definition of different interpretations of the ANSI SQL specification. One of them they call “anomaly serializable (strict interpretation)”.

We can build a model this interpretation in Alloy. Here’s part of it just to give you a sense of what it looks like, see my bbg.als file for the complete model:

pred AnomalySerializableStrict { not A1 not A2 not A3}/** * A1: w1[x]...r2[x]...(a1 and c2 in any order) */pred A1 { some T1 : AbortedTransaction, T2 : CommittedTransaction, w1: Write & events[T1], r2 : Read & events[T2], a1 : Abort & events[T1] | { w1->r2 in teo r2.sees = w1 // r2 has to happen before T1 aborts r2->a1 in teo }}...And then we can ask Alloy to check whether AnomalySerializableStrict implies Adya’s definition of serializability (which he calls isolation level PL-3).

Here’s how I asked Alloy to check this:

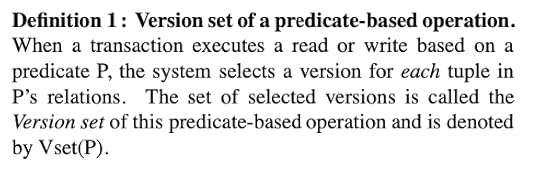

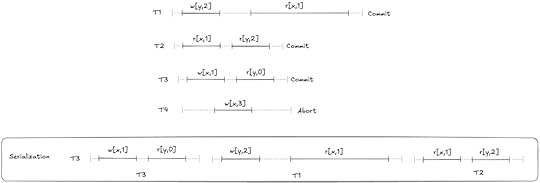

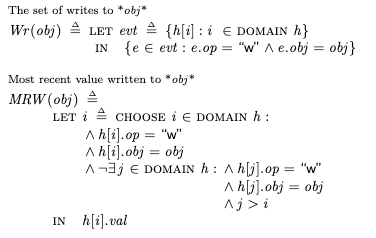

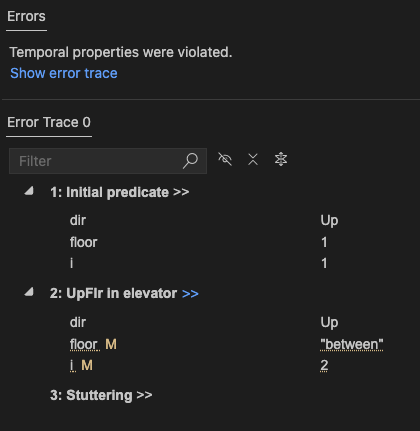

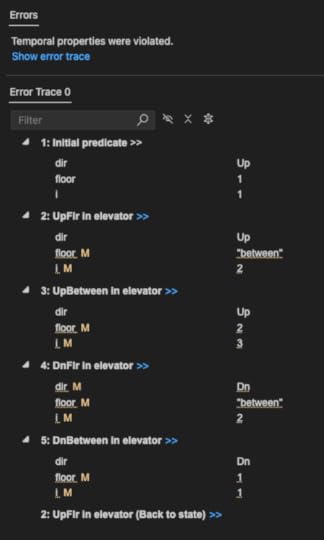

assert anomaly_serializable_strict_implies_PL3 { always_read_most_recent_write => (b/AnomalySerializableStrict => PL3)}check anomaly_serializable_strict_implies_PL3for 8 but exactly 3 Transaction, exactly 2 Object, exactly 1 PredicateRead, exactly 1 PredicateAlloy tells me that the assertion is invalid, and shows the following counterexample:

This shows a history that satisfies the anomaly serializable (strict) specificaiton, but not Adya’s PL-3. Note that the Alloy visualizer has generated a direct serialization graph (DSG) in the bottom left-hand corner, which contains a cycle.

Predicate readsThis counterexample involves predicate reads, which I hadn’t shown modeled before, but they look like this:

// transactions.alsabstract sig Predicate {}abstract sig PredicateRead extends Event { p : Predicate, objs : set Object}// adya.alssig VsetPredicateRead extends PredicateRead { vset : set Version}sig VsetPredicate extends Predicate { matches : set Version}A predicate read is a read that returns a set of objects.

In Adya’s model, a predicate read takes as input a version set (a version for each object) and then determines which objects should be included in the read based on whether or not the versions match the predicate:

fact "objects in predicate read are the objects that match in the version set" { all pread : VsetPredicateRead | pread.objs = (pread.vset & pread.p.matches).obj}One more counterexampleWe can also use Alloy to show us when a transaction would be permitted by Adya’s PL-3, but forbidden by the broad interpretation of anomaly serializability:

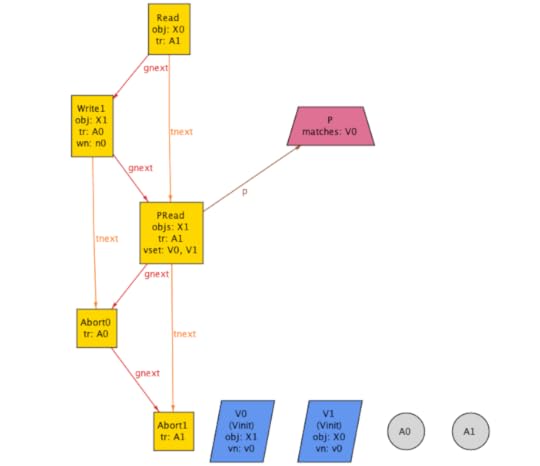

check PL3_implies_anomaly_serializable_broadfor 8 but exactly 3 Transaction, exactly 2 Object, exactly 1 PredicateRead, exactly 1 Predicateassert PL3_implies_anomaly_serializable_broad { always_read_most_recent_write => (PL3 => b/AnomalySerializableBroad)}

The example above shows the “gnext” relation, which yields a total order across events.

The resulting counterexample is two aborted transactions! Those are trivially serializable, but it is ruled out by the broad definition, specifically, P3:

Playing with Alloy

Playing with AlloyI encourage you to try Alloy out. There’s a great that will let you execute your Alloy models from VS Code, that’s what I’ve been using. It’s very easy to get started with Alloy, because you can get it to generate visualizations for you out of the simplest models.

For more resources, Hillel Wayne has written a set of Alloy docs that I often turn to. There’s even an entire book on Alloy written by its creator. (Confusingly, though, the book does not have the word Alloy in the name).

November 3, 2024

Extending MVCC to be serializable, in TLA+

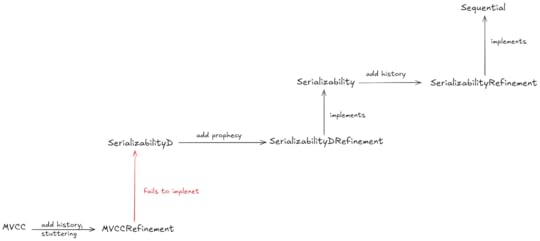

In the previous blog post, we saw how a transaction isolation strategy built on multi-version concurrency control (MVCC) does not implement the serializable isolation level. Instead, it implements a weaker isolation level called snapshot isolation. In this post, I’ll discuss how that MVCC model can be extended in order to achieve serializability, based on work published by Michael Cahill, Uwe Röhm, and Alan Fekete.

You can find the model I wrote in the https://github.com/lorin/snapshot-isolation-tla repo, in the SSI module (source, pdf).

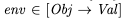

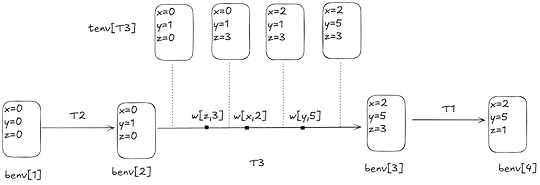

A quick note on conventionsIn this post, I denote read of x=1 as r[x,1]. This means a transaction read the object x which returned a value of 1. As I mentioned in the previous post, you can imagine a read as being the following SQL statement:

SELECT v FROM obj WHERE k='x';Similarly, I denote a write of y←2 as w[y,2]. This means a transaction wrote the object y with a value of 2. You can imagine this as:

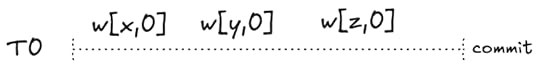

UPDATE obj SET v=2 WHERE k='y';Finally, I’ll assume that there’s an initial transaction (T0) which sets the values of all of the objects to 0, and has committed before any other transaction starts.

We assume this transaction always precedes all other transactionsBackgroundThe SQL isolation levels and phenomena

We assume this transaction always precedes all other transactionsBackgroundThe SQL isolation levels and phenomenaThe ANSI/ISO SQL standard defines four transaction isolation levels: read uncommitted, read committed, repeatable read, and serializable. The standard defines the isolation levels in terms of the phenomena they prevent. For example, the dirty read phenomenon is when one transaction reads a write done by a concurrent transaction that has not yet committed. Phenomena are dangerous because they may violate a software developer’s assumptions about how the database will behave, leading to software that behaves incorrectly.

Problems with the standard and a new isolation levelBerenson et al. noted that the standard’s wording is ambiguous, and of the two possible interpretations of the definitions, one was incorrect (permitting invalid execution histories) and the other was overly strict (proscribing valid execution histories).

The overly strict definition implicitly assumed that concurrency control would be implemented using locking, and this ruled out valid implementations based on alternate schemes, in particular, multi-version concurrency control. They also proposed a new isolation level: snapshot isolation.

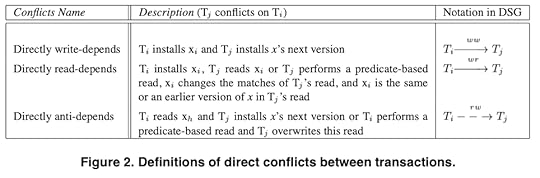

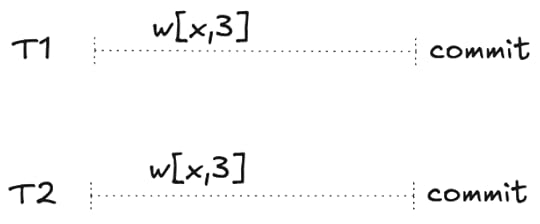

Formalizing phenomena and anti-dependenciesIn his PhD dissertation work, Adya introduced a new formalization for reasoning about transaction isolation. The formalism is based on a graph of direct dependencies between transactions.

One type of dependency Adya introduced is called an anti-dependency, which is critical to the difference between snapshot isolation and serializable.

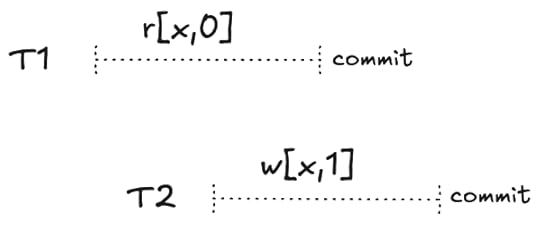

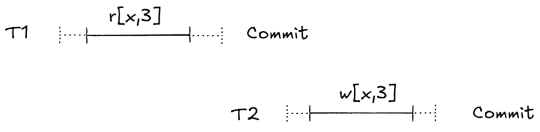

An anti-dependency between two concurrent transactions is when one read an object and the other writes the object with a different value, for example:

T1 is said to have an anti-dependency on T2: T1 must come before T2 in a serialization:

If T2 is sequenced before T1, then the read will not match the most recent write. Therefore, T1 must come before T2.

If T2 is sequenced before T1, then the read will not match the most recent write. Therefore, T1 must come before T2.In dependency graphs, anti-dependencies are labeled with rw because the transaction which does the read must be sequenced before the transaction that does the write, as shown above.

Adya demonstrated that for an implementation that supports snapshot isolation to generate execution histories that are not serializable, there must be a cycle in the dependency graph that includes an anti-dependency.

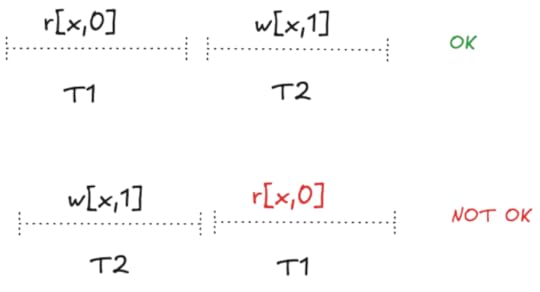

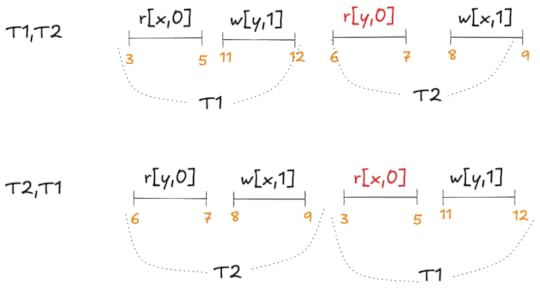

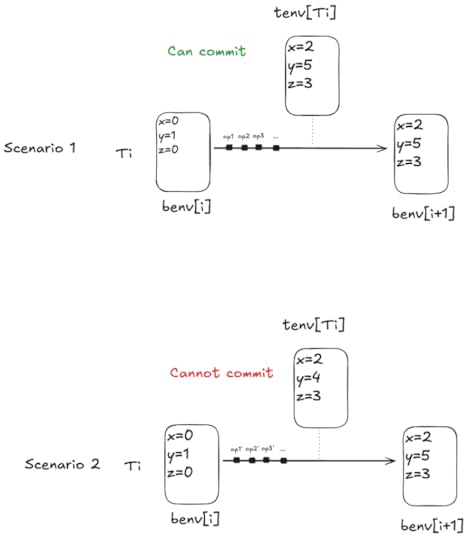

Non-serializable execution histories in snapshot isolationIn the paper Making Snapshot Isolation Serializable, Fekete et al. further narrowed the conditions under which snapshot isolation could lead to a non-serializable execution history, by proving the following theorem:

THEOREM 2.1. Suppose H is a multiversion history produced under Snapshot Isolation that is not serializable. Then there is at least one cycle in the serialization graph DSG(H), and we claim that in every cycle there are three consecutive transactions Ti.1, Ti.2, Ti.3 (where it is possible that Ti.1 and Ti.3 are the same transaction) such that Ti.1 and Ti.2 are concurrent, with an edge Ti.1 → Ti.2, and Ti.2 and Ti.3 are concurrent with an edge Ti.2 → Ti.3.

They also note:

By Lemma 2.3, both concurrent edges whose existence is asserted must be anti-dependencies:Ti.1→ Ti.2 and Ti.2→ Ti.3.

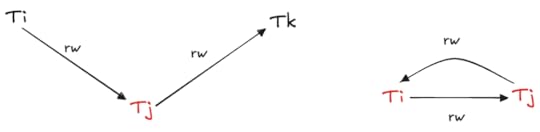

This means that one of the following two patterns must always be present in a snapshot isolation history that is not serializable:

Non-serializable snapshot isolation histories must contain one of these as subgraphs in the dependency graphModifying MVCC to avoid non-serializable histories

Non-serializable snapshot isolation histories must contain one of these as subgraphs in the dependency graphModifying MVCC to avoid non-serializable historiesCahill et al. proposed a modification to MVCC that can dynamically identify potential problematic transactions that could lead to non-serializable histories, and abort them. By aborting these transactions, the resulting algorithm guarantees serializability.

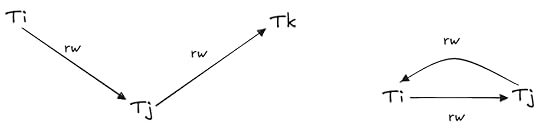

As Fekete et al. proved, under snapshot isolation, cycles can only occur if there exists a transaction which contains an incoming anti-dependency edge and an outgoing anti-dependency edge, which they call pivot transactions.

Pivot transactions shown in red

Pivot transactions shown in redTheir approach is to identify and abort pivot transactions: if an active transaction contains both an outgoing and an incoming anti-dependency, the transaction is aborted. Note that this is a conservative algorithm: some of the transactions that it aborts may have still resulted in serializable execution histories. But it does guarantee serializability.

Their modification to MVCC involves some additional bookkeeping:

Reads performed by each transactionWhich transactions have outgoing anti-dependenciesWhich transactions have incoming anti-dependenciesThe tracking of reads is necessary to identify the presence of anti-dependencies, since an anti-dependency always involve a read (outgoing dependency edge) and a write (incoming dependency edge).

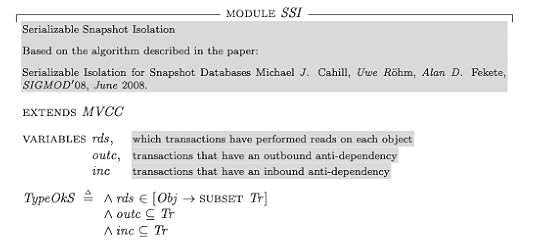

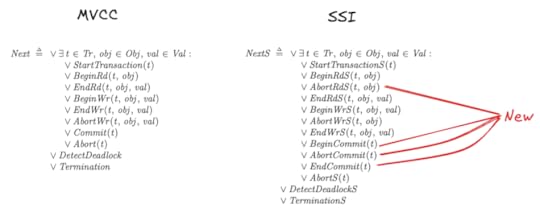

Extending our MVCC TLA+ model for serializabilityAdding variablesI created a new module called SSI, which stands for Serializable Snapshot Isolation. I extended the MVCC model to add three variables to implement the additional bookkeeping required by the Cahill et al. algorithm. MVCC already tracks which objects are written by each transaction, but we need to now also track reads.

rds – which objects are read by which transactionsoutc – set of transactions that have outbound anti-dependenciesinc – set of transactions that have inbound anti-dependencies

TLA+ is untyped (unless you’re using Apalache), but we can represent type information by defining a type invariant (above, called TypeOkS). Defining this is useful both for the reader, and because we can check that this holds with the TLC model checker.

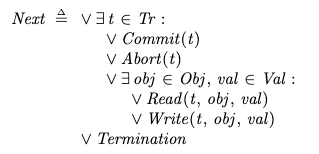

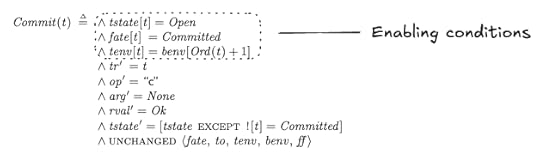

Changes in behavior: new abort opportunitiesHere’s how the Next action in MVCC compares to the equivalent in SSI.

Note: Because extending the MVCC module brings all of the MVCC names into scope, I had to create new names for each of the equivalent actions in SSI, I did this by appending an S (e.g., StartTransactionS, DeadlockDetectionS).

In our original MVCC implementation, reads and commits always succeeded. Now, it’s possible for an attempted read or an attempted to commit to result in aborts as well, so we needed an action for this, which I called AbortRdS.

Commits can now also fail, so instead of having a single-step Commit action, we now have a BeginCommit action, which will complete successfully by an EndCommit action, or fail with an abort by the AbortCommit action. Writes can also now abort due to the potential for introducing pivot transactions.

Finding aborts with the model checkerHere’s how I used the TLC model checker to generate witnesses of the new abort behaviors:

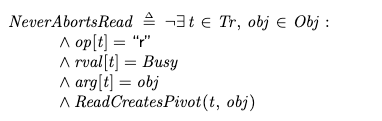

Aborted readsTo get the model checker to generate a trace for an aborted read, I defined the following invariant in the MCSSI.tla file:

Then I specified it as an invariant to check in the model checker in the MCSSI.cfg file:

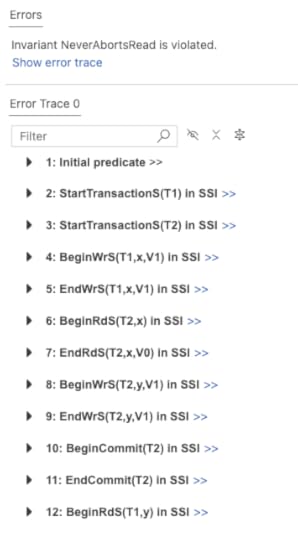

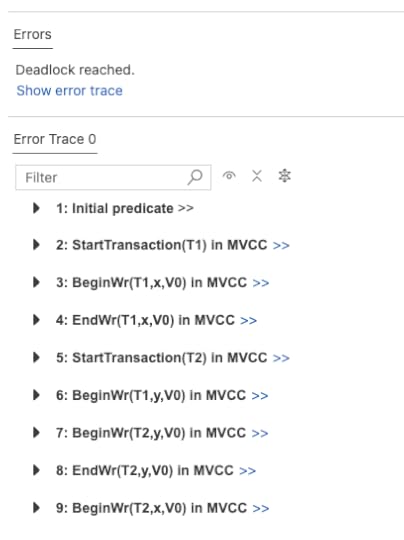

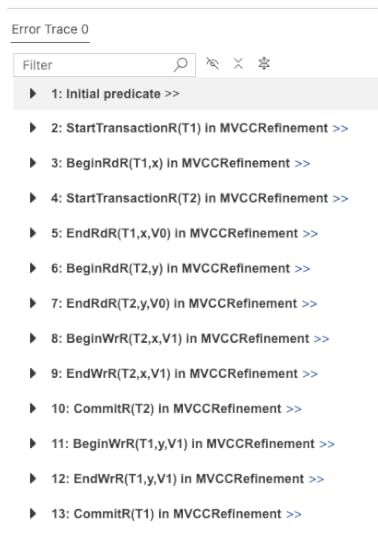

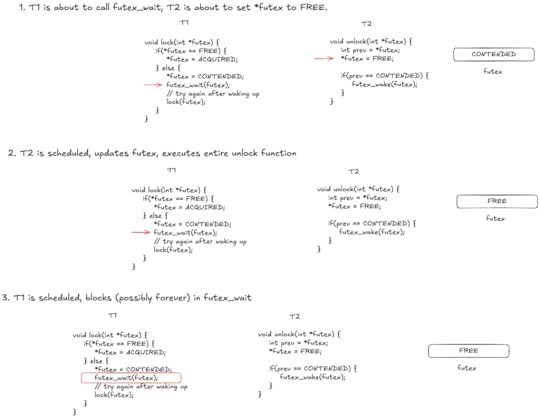

INVARIANT NeverAbortsReadBecause aborted reads can, indeed, happen, the model checker returned an error, with the following error trace:

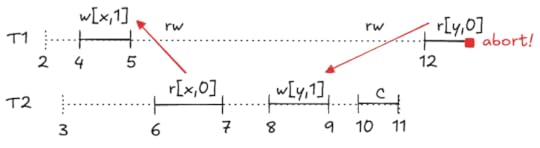

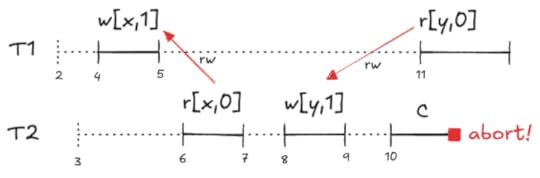

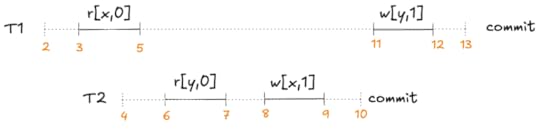

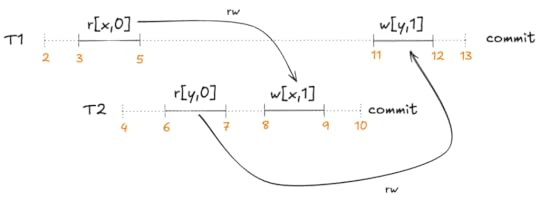

The resulting trace looks like this, with the red arrows indicating the anti-dependencies.

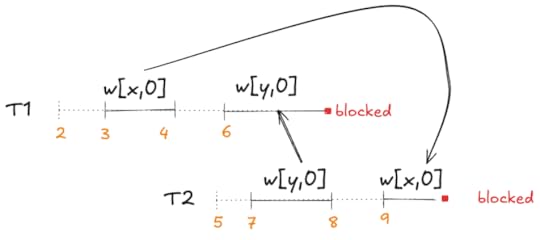

Aborted commit

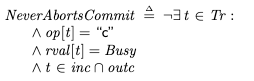

Aborted commitSimilarly, we can use the model checker to identify scenarios where it a commit would fail, by specifying the following invariant:

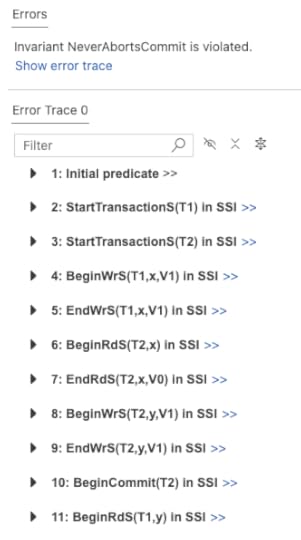

The checker finds the following violation of that invariant:

While T2 is in the process of committing, T1 performs a read which turns T2 into a pivot transaction. This results in T2 aborting.

Checking serializability using refinement mapping

Checking serializability using refinement mappingJust like we did previously with MVCC, we can define a refinement mapping from our SSI spec to our Serializability spec. You can find it in the SSIRefinement module (source, pdf). It’s almost identical to the MVCCRefinement module (source, pdf), with some minor modifications to handle the new abort scenarios.

The main difference is that now the refinement mapping should actually hold, because SSI ensures serializability! I wasn’t able to find a counterexample when I ran the model checker against the refinement mapping, so that gave me some confidence in my model. Of course, that doesn’t prove that my implementation is correct. But it’s good enough for a learning exercise.

Coda: on extending TLA+ specificationsSerializable Snapshot Isolation provides us with a nice example of when we can extend an existing specification rather than create a new one from scratch.

Even so, it’s still a fair amount of work to extend an existing specification. I suspect it would have been less work to take a copy-paste-and-modify approach rather than extending it. Still, I found it a useful exercise in learning how to modify a specification by extending it.

October 31, 2024

Multi-version concurrency control in TLA+

In a previous blog post, I talked about how we can use TLA+ to specify the serializability isolation level. In this post, we’ll see how we can use TLA+ to describe multi-version concurrency control (MVCC), which is a strategy for implementing transaction isolation. Postgres and MySQL both use MVCC to implement their repeatable read isolation levels, as well as a host of other databases.

MVCC is described as an optimistic strategy because it doesn’t require the use of locks, which reduces overhead. However, as we’ll see, MVCC implementations aren’t capable of achieving serializability.

All my specifications are in https://github.com/lorin/snapshot-isolation-tla.

Modeling MVCC in TLA+Externally visible variablesWe use a similar scheme as we did previously for modeling the externally visible variables. The only difference now is that we are also going to model the “start transaction” operation:

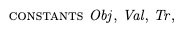

Variable nameDescriptionopthe operation (start transaction, read, write, commit, abort), modeled as a single letter: {“s”, “r”, “w”, “c”, “a”} )argthe argument(s) to the operationrvalthe return value of the operationtrthe transaction executing the operationThe constant setsThere are three constant sets in our model:

Obj – the set of objects (x, y,…)Val – the set of values that the objects can take on (e.g., 0,1,2,…)Tr – the set of transactions (T0, T1, T2, …)

Obj – the set of objects (x, y,…)Val – the set of values that the objects can take on (e.g., 0,1,2,…)Tr – the set of transactions (T0, T1, T2, …)

I associate the initial state of the database with a previously committed transaction T0 so that I don’t have to treat the initial values of the database as a special case.

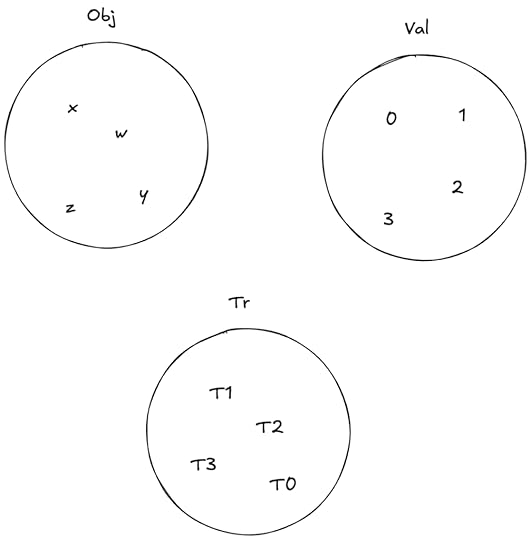

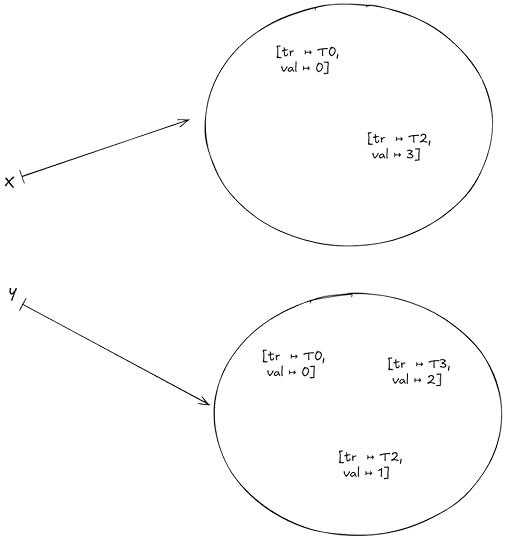

The multiversion databaseIn MVCC, there can be multiple versions of each object, meaning that it stores multiple values associated with each object. Each of these versions is also has information on which transaction created it.

I modeled the database in TLA+ as a variable named db, here is an invariant that shows the values that db can take on:

It’s a function that maps objects to a set of version records. Each version record is associated with a value and a transaction. Here’s an example of a valid value for db:

Example db where Obj={x,y}Playing the home game with Postgres

Example db where Obj={x,y}Playing the home game with PostgresPostgres’s behavior when you specify repeatable read isolation level appears to be consistent with the MVCC TLA+ model I wrote so I’ll use it to illustrate some how these implementation details play out. As Peter Alvaro and Kyle Kingsbury note in their Jepsen analysis of MySQL 8.0.34, Postgres’s repeatable read isolation level actually implements snapshot isolation, while MySQL’s repeatable read isolation level actually implements …. um … well, I suggest you read the analysis.

I created a Postgres database named tla. Because Postgres defaults to read committed, I changed the default to repeatable read on my database so that it would behave more like my model.

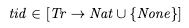

ALTER DATABASE tla SET default_transaction_isolation TO 'repeatable read';create table obj ( k char(1) primary key, v int);insert into obj (k,v) values ('x', 0), ('y', 0);Starting a transaction: id and visibilityIn MVCC, each transaction gets assigned a unique id, and ids increase monotonically.

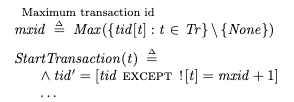

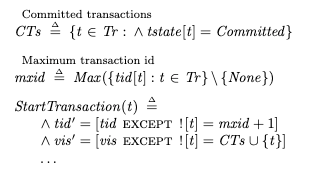

Transaction id: tidI modeled this with a function tid that maps transactions to natural numbers. I use a special value called None for the transaction id for transactions who have not started yet.

When a transaction starts, I assign it an id by finding the largest transaction id assigned so far (mxid), and then adding 1. This isn’t efficient, but for a TLA+ spec it works quite nicely:

In Postgres, you can get the ID of the current transaction by using the pg_current_xact_id function. For examplle:

$ psql tlapsql (17.0 (Homebrew))Type "help" for help.tla=# begin;BEGINtla=*# select pg_current_xact_id(); pg_current_xact_id-------------------- 822(1 row)Visible transactions: visWe want each transaction to behave as if it is acting against a snapshot of the database from when the transaction started.

We can implement this in MVCC by identifying the set of transactions that have previously committed, and ensuring that our queries only read from writes done by these transactions.

I modeled this with a function called vis which maps each transaction to a set of other transactions. We also want our own writes to be visible, so we include the transaction being started in the set of visible transactions:

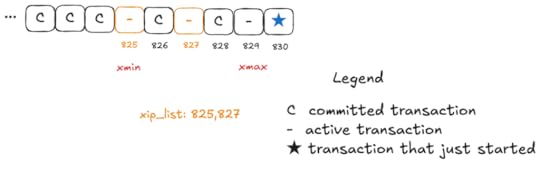

For each snapshot, Postgres tracks the set of committed transactions using three variables:

xmin – the lowest transaction id associated with an active transactionxmax – (the highest transaction id associated with a committed transaction) + 1xip_list – the list of active transactions whose ids are less than xmaxIn Postgres, you can use the pg_current_snapshot function, which returns xmin:xmax:xip_list:

tla=# SELECT pg_current_snapshot(); pg_current_snapshot--------------------- 825:829:825,827Here’s a visualization of this scenario:

These three variables are sufficient to determine whether a particular version is visible. For more on the output of pg_current_snapshot, check out the Postgres operations cheat sheet wiki.

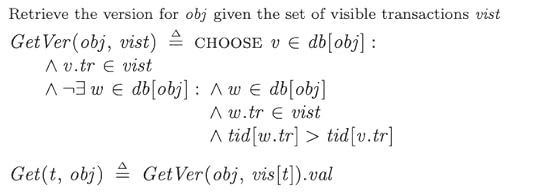

Performing readsA transaction does a read using the Get(t, obj) operator. This operator retrieves the visible version with the largest transaction id:

Performing writes

Performing writesWrites are straightforward, they simply add new versions to db. However, if a transaction did a previous write, that previous write has to be removed. Here’s part of the action that writes obj with value val for transaction t:

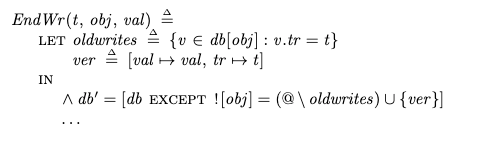

The lost update problem and how MVCC prevents it

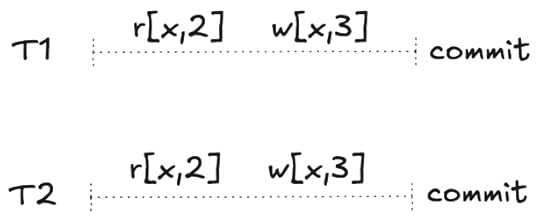

The lost update problem and how MVCC prevents itConsider the following pair of transactions. They each write the same value and then commit.

A serializable execution history

A serializable execution historyThis is a serializable history. It actually has two possible serializations: T1,T2 or T2,T1

Now let’s consider another history where each transaction does a read first.

A non-serializable execution history

A non-serializable execution historyThis execution history isn’t serializable anymore. If you try to sequence these, the second read will read 2 where it should read 3 due to the previous write.

Serializability is violated: the read returns 2 instead of 3

Serializability is violated: the read returns 2 instead of 3This is referred to as the lost update problem.

Here’s a concrete example of the lost update problem. Imagine you’re using a record as a counter: you read the value, increment the result by one, and then write it back.

SELECT v FROM obj WHERE k='x';-- returns 3UPDATE obj set v=4 WHERE k='x';Now imagine these two transactions run concurrently. If neither sees the other’s write, then one of these increments will be lost: you will have missed a count!

MVCC can guard against this by preventing two concurrent transactions from writing to the same object. If transaction T1 has written to a record in an active transaction, and T2 tries to write to the same record, then the database will block T2 until T1 either commits or aborts. If the first transaction commits, the database will abort the second transaction.

You can confirm this behavior in Postgres, where you’ll get an error if you try to write to a record that has previously been written to by a transaction that was active and then committed:

$ psql tlapsql (17.0 (Homebrew))Type "help" for help.tla=# begin;BEGINtla=*# update obj set v=1 where k='x';ERROR: could not serialize access due to concurrent updatetla=!#Interestingly, MySQL’s MVCC implementation does not prevent lost updates(!!!). You can confirm this yourself.

Implementing this in our modelIn our model, a write is implemented by two actions:

BeginWr(t, obj, val) – the initial write requestEndWr(t, obj, val) – the successful completion of the writeWe do not allow the EndWr action to fire if:

There is an active transaction that has written to the same object (here we want to wait until the other transaction commits or aborts)There is a commit to the same object by a concurrent transaction (here we want to abort)

We also have an action named AbortWr that aborts if a write conflict occurs.

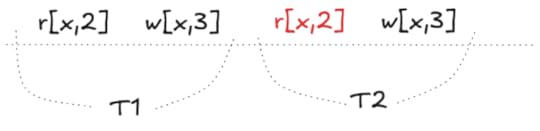

Deadlock!There’s one problem with the approach above where we block on a concurrent write: the risk of deadlock. Here’s what happens when we run our model with the TLC model checker:

Here’s a diagram of this execution history:

The problem is that T1 wrote x first and T2 wrote y first, and then T1 got blocked trying to write y and T2 got blocked trying to write x. (Note that even though T1 started to write y before T2, T2 completed the write first).

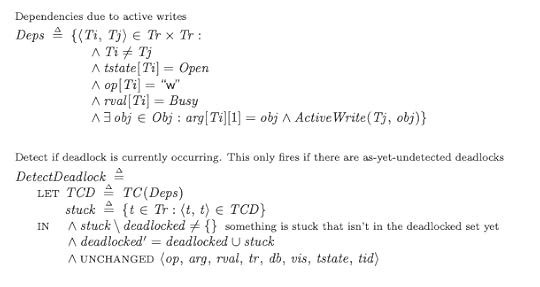

We can deal with this problem by detecting deadlocks and aborting the affected transactions when they happen. We can detect deadlock by creating a graph of dependencies between transactions (just like in the diagram above!) and then look for cycles:

Here TC stands for transitive closure, which is a useful relation when you want to find cycles. I used one of the transitive closure implementations in the TLA+ examples repo.

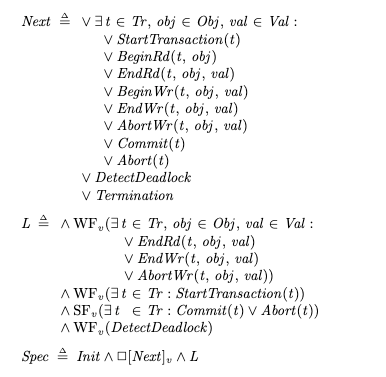

Top-level of the specificationHere’s a top-level view of the specification, you can find the full MVCC specification in the repo (source, pdf):

Note how reads and writes have begin/end pairs. In addition, a BeginWr can end in an AbortWr if there’s a conflict or deadlock as discussed earlier.

For liveness, we can use weak fairness to ensure that read/write operations complete, transactions start, and that deadlock is detected. But for commit and abort, we need strong fairness, because we can have infinite sequences of BeginRd/EndRd pairs or BeginWr/EndWr pairs and Commit and Abort are not enabled in the middle of reads or writes.

My MVCC spec isn’t serializableNow that we have an MVCC spec, we can check to see if implements our Serializable spec. In order to do that check, we’ll need to do a refinement mapping from MVCC to Serializable.

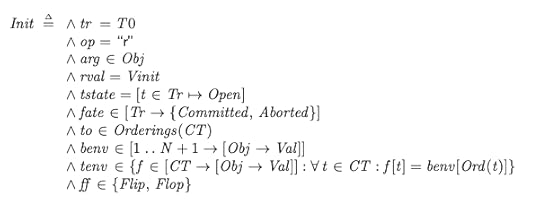

One challenge is that the initial state of the Serializable specification establishes the fate of all of the transactions and what their environments are going to be in the future:

The Init state for the Serializable specAdding a delay to the Serializability spec

The Init state for the Serializable specAdding a delay to the Serializability specIn our MVCC spec, we don’t know in advance if a transaction will commit or abort. We could use prophecy variables in our refinement mapping to predict these values, but I didn’t want to do that.

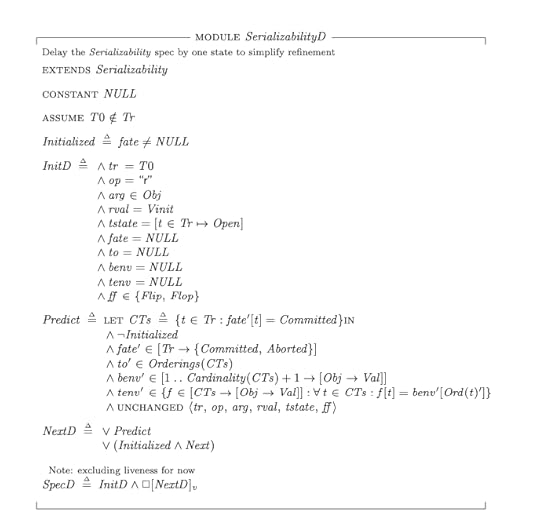

What I did instead was to create a new specification, SerializabilityD (source, pdf), that delays these predictions until the second step of the behavior:

I could then do a refinement mapping MVCC ⇒ SerializabilityD without having to use prophecy variables.

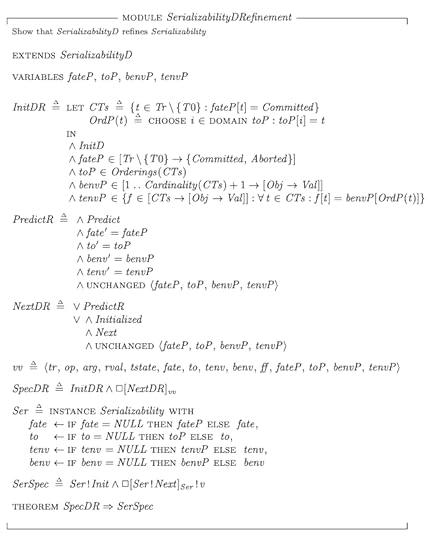

Verifying that SerializabilityD actually implements SerializabilityNote that it’s straightforward to do the SerializabilityD ⇒ Serializability refinement mapping with prophecy variables. You can find it in SerializabilityDRefinement (source, pdf):

The MVCC ⇒ SerializabilityD mapping

The MVCC ⇒ SerializabilityD mappingThe MVCC ⇒ SerializabilityD refinement mapping is in the MVCCRefinement spec (source, pdf).

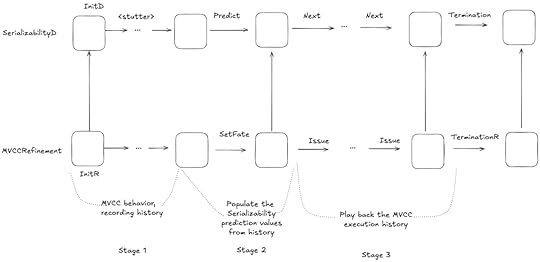

The general strategy here is:

Execute MVCC until all of the transactions complete, keeping an execution history. Use the results of the MVCC execution to populate the SerializabilityD variablesStep through the recorded MVCC execution history one operation at a timeThe tricky part is step 2, because we need to find a serialization.

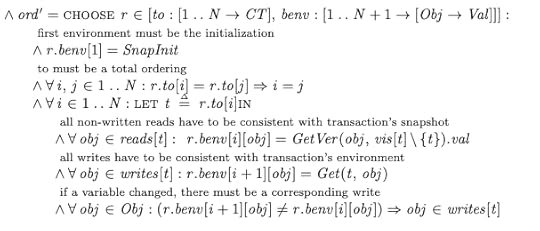

Attempting to find a serializationOnce we have an MVCC execution history, we can try to find a serialization. Here’s the relevant part of the SetFate action that attempts to select the to and benv variables from Serializability that will satisfy serializability:

Checking the refinement mapping

Checking the refinement mappingThe problem with the refinement mapping is that we cannot always find a serialization. If we try to model check the refinement mapping, TLC will error because it is trying to CHOOSE from an empty set.

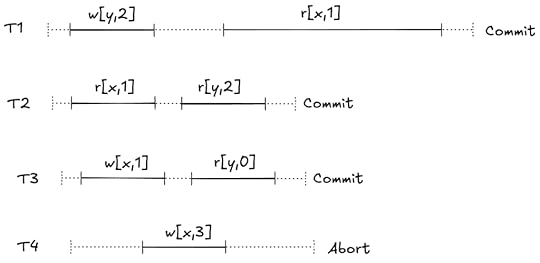

This MVCC execution history is a classic example of what’s called write skew. Here’s a visual depiction of this behavior:

A non-serializable execution history that is permitted by MVCC

A non-serializable execution history that is permitted by MVCCNeither T1,T2 nor T2,t1 is a valid serialization of this execution history:

If we sequence T1 first, then the r[y,0] read violates the serialization. If we sequence T2 first, then the r[x,0] read violates it.

If we sequence T1 first, then the r[y,0] read violates the serialization. If we sequence T2 first, then the r[x,0] read violates it.These constraints are what Adya calls anti-dependencies. He uses the abbreviation rw for short, because the dependency is created by a write from one transaction clobbering a read done by the other transaction, so the write has to be sequenced after the read.

Because snapshot isolation does not enforce anti-dependencies, it generates histories that are not serializable, which means that MVCC does not implement the Serializability spec.

CodaI found this exercise very useful in learning more about how MVCC works. I had a hard time finding a good source to explain the concepts in enough detail for me to implement it, without having to read through actual implementations like Postgres, which has way too much detail. One useful resource I found was these slides on MVCC by Joy Arulraj at Georgia Tech. But even here, they didn’t have quite enough detail, and my model isn’t quite identical. But it was enough to help me get started.

I also enjoyed using refinement mapping to do validation. In the end, these were the refinement mappings I defined:

I’d encourage you to try out TLA+, but it really helps if you have some explicit system in mind you want to model. I’ve found it very useful for deepening my understanding of consistency models.

October 29, 2024

The carefulness knob

Dramatis personae

EM, an engineering managerTL, the tech lead for the teamX, an engineering manager from a different team

EM, an engineering managerTL, the tech lead for the teamX, an engineering manager from a different teamScene 1: A meeting room in an office. The walls are adorned with whiteboards with boxes and arrows.

EM: So, do you think the team will be able to finish all of these features by end of the Q2?

TL: Well, it might be a bit tight, but I think it should be possible, depending on where we set the carefulness knob.

EM: What’s the carefulness knob?

TL: You know, the carefulness knob! This thing.

TL leans over and picks a small box off of the floor and places it on the table. The box has a knob on it with numerical markings.

EM: I’ve never seen that before. I have no idea what it is.

TL: As the team does development, we have to make decisions about how much effort to spend on testing, how closely to hew to explicitly documented processes, that sort of thing.

EM: Wait, aren’t you, like, careful all of the time? You’re responsible professionals, aren’t you?

TL: Well, we try our best to allocate our effort based on what we estimate the risk to be. I mean, we’re a lot more careful when we do a database migration than we do when we fix a typo in the readme file!

EM: So… um… how good are you at actually estimating risk? Wasn’t that incident that happened a few weeks ago related to a change that was considered a low risk at the time?

TL: I mean, we’re pretty good. But we’re definitely not perfect. It certainly happens that we misjudge the risk sometimes. I mean, in some sense, isn’t every incident in some sense a misjudgment of risk? How many times do we really say, “Hoo boy, this thing I’m doing is really risky, we’re probably going to have an incident!” Not many.

EM: OK, so let’s turn that carefulness knob up to the max, to make sure that the team is careful as possible. I don’t want any incidents!

LM: Sounds good to me! Of course, this means that we almost certainly won’t have these features done by the end of Q2, but I’m sure that the team will be happy to hear…

EM: What, why???

TL picks up a marker off of the table and walks up to the whiteboard. She draws an x axis and y-axis. She labels the x-axis “carefulness” and the y-axis “estimated completion time”.

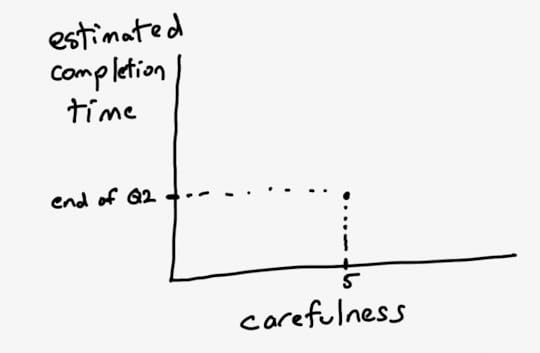

TL: Here’s our starting point: the carefulness knob is currently set at 5, and we can properly hit end of Q2 if we keep it at this setting.

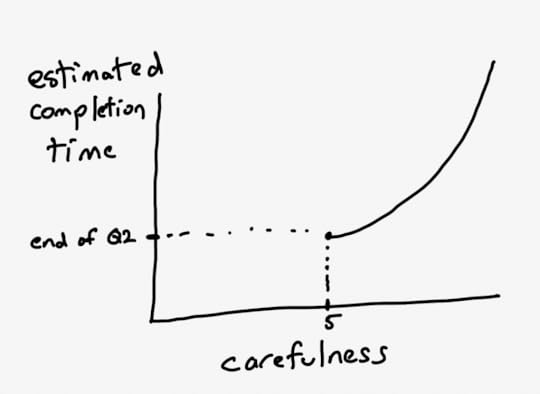

EM: What happens if we turn up the knob?

TL draws an exponential curve.

EM: Woah! That’s no good. Wait, if we turn the carefulness knob down, does that mean that we can go even faster?

TL: If we did that, we’d just be YOLO’ing our changes, not doing validation. Which means we’d increase the probability of incidents significantly, which end up taking a lot of time to deal with. I don’t think we’d actually end up delivering any faster if we chose to be less careful than we normally are.

EM: But won’t we also have more incidents at a carefulness setting of 5 than at higher carefulness settings?

TL: Yes, there’s definitely more of a risk that a change that we incorrectly assess as low risk ends up biting us at our default carefulness level. It’s a tradeoff we have to make.

EM: OK, let’s just leave the carefulness knob at the default setting.

Scene 2: An incident review meeting, two and a half months later.

X: We need to be more careful when we make these sorts of changes in the future!

Fin

CodaIt’s easy to forget that there is a fundamental tradeoff between how careful we can be and how much time it will take us to perform a task. This is known as the efficiency-thoroughness trade-off, or ETTO principle.

You’ve probably hit a situation where it’s particularly difficult to automate the test for something, and doing the manual testing is time-intensive, and you developed the feature and tested it, but then there was a small issue that you needed to resolve, and then do you go through all of the manual testing again? We make these sort of time tradeoffs in the small, they’re individual decisions, but they add up, and we’re always under schedule pressure to deliver.

As a result, we try our best to adapt to the perceived level of risk in our work. The Human and Organizational Performance folks are fond of the visual image of the black line versus the blue line to depict the difference between how the work is supposed to be done with how workers adapt to get their work done.

But sometimes these adaptations fail. And when this happens, inevitably someone says “we need to be more careful”. But imagine if you explicitly asked that person at the beginning of a project about where they wanted to set that carefulness knob, and they had to accept that increasing the setting would increase the schedule significantly. If an incident happened, you could then say to them, “well, clearly you set the carefulness knob too low at the beginning of this project”. Nobody wants to explicitly make the tradeoff between less careful and having an time estimate that’s seen as excessive. And so the tradeoff gets made implicitly. We adapt as best we can to the risk. And we do a pretty good job at that… most of the time.

October 28, 2024

Specifying serializability in TLA+

Concurrency is really, really difficult for humans to reason about. TLA+ itself was borne out of Leslie Lamport’s frustration with the difficulty of write error-free concurrent algorithms:

When I first learned about the mutual exclusion problem, it seemed easy and the published algorithms seemed needlessly complicated. So, I dashed off a simple algorithm and submitted it to CACM. I soon received a referee’s report pointing out the error. This had two effects. First, it made me mad enough at myself to sit down and come up with a real solution. The result was the bakery algorithm described in [12]. The second effect was to arouse my interest in verifying concurrent algorithms.

Modeling concurrency control in database systems is a great use case for TLA+, so I decided to learn use TLA+ to learn more about database isolation. This post is about modeling serializability.

You can find all of the the TLA+ models referenced in this post in my snapshot-isolation-tla repo. This post isn’t about snapshot isolation at all, so think of the name as a bit of foreshadowing of a future blog post, which we’ll discuss at the end.

Modeling a database for reasoning about transaction isolationIn relational databases, data is modeled as rows in different tables, where each table has a defined set of named columns, and there are foreign key relationships between the tables.

However, when modeling transaction isolation, we don’t need to worry about those details. For the purpose of a transaction, all we care about is if any of the columns of a particular row are read or modified. This means we can ignore details about tables, columns, and relations. All we care about are the rows.

The transaction isolation literature talks about objects instead of rows, and that’s the convention I’m going to use. Think of an object like a variable that is assigned a value, and that assignment can change over time. A SQL select statement is a read, and a SQL update statement is a write.

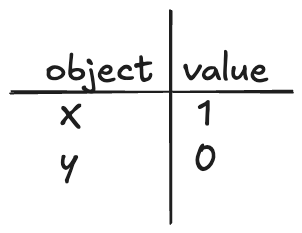

An example of how we’re modeling the database

An example of how we’re modeling the databaseNote that the set of objects is fixed during the lifetime of the model, it’s only the values that change over time. I’m only going to model reads and writes, but it’s simple enough to extend this model to support creation and deletion by writing a tombstone value to model deletion, and having a not-yet-created-stone value to model an object that has not yet been created in the database.

I’ll use the notation r[obj, val] to refer to a read operation where we read the object obj and get the value val and w[obj, val] to mean where we write the value val to obj. So, for example, setting x=1 would be: w[x, 1], and reading the value of x as 1 would be r[x, 1].

I’m going to use Obj to model the set of objects, and Val to model the set of possible values that objects can take on.

Obj is the set of objects, Val is the set of values that can be assigned to objects

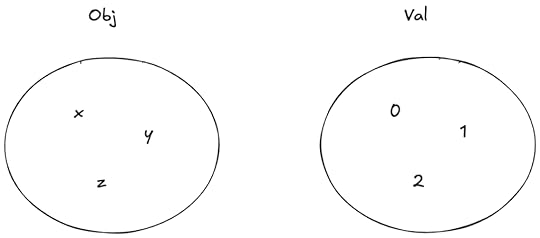

Obj is the set of objects, Val is the set of values that can be assigned to objectsWe can model the values of the objects at any point in time as a function that maps objects to values. I’ll call these sorts of functions environments (env for short) since that’s what people who write interpreters call them.

Example of an environment

Example of an environmentAs an example of syntax, here’s how we would assert in TLA+ that the variable env is a function that maps element of the set Obj to elements of the set Val:

What is serializability?

What is serializability?Here’s how the SQL:1999 standard describes serializability (via the Jepsen serializability page):

The execution of concurrent SQL-transactions at isolation level SERIALIZABLE is guaranteed to be serializable. A serializable execution is defined to be an execution of the operations of concurrently executing SQL-transactions that produces the same effect as some serial execution of those same SQL-transactions. A serial execution is one in which each SQL-transaction executes to completion before the next SQL-transaction begins.

An execution history of reads and writes is serializable if it is equivalent to some other execution history where the committed transactions are scheduled serially (i.e., they don’t overlap in time). Here’s an example of a serializable execution history.

Atul Adya famously came up with a formalism for database isolation levels (including serializability) in his PhD dissertation work, and published this in a paper co-authored by Barbara Liskov (his PhD advisor) and Patrick O’Neil (an author of the original log-structured merge-tree paper and one of the co-authors of the paper A Critique of ANSI SQL Isolation Levels, which pointed out problems in the SQL specification’s definitions of the isolation levels ).

Specifying serializabilityAdya formalized database isolation levels by specifying dependencies between transactions. However, I’m not going to use Adya’s approach for my specification. Instead, I’m going to use a state-based approach, like the one used by Natacha Crooks, Youer Pu, Lorenzo Alvisi and Allen Clement in their paper Seeing is Believing: A Client-Centric Specification of Database Isolation.

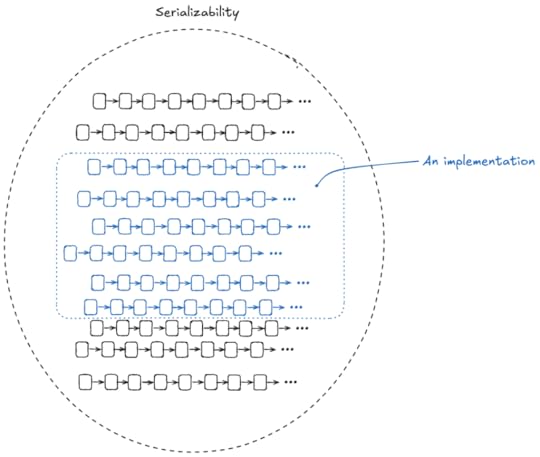

It’s important to remember that a specification is just a set of behaviors (series of state transitions). We’re going to use TLA+ to define the set of all of the behaviors that we consider valid for serializability. Another way to put that is that our specification is the set of all serializable executions.

We want to make sure that if we build an implementation, all of the behaviors permitted by the implementation are a subset of our serializability specification.

Note: Causality is not required

Note: Causality is not requiredHere’s an example of an execution history that is serializable according to the definition:

This looks weird to us because the write happens after the read: T1 is reading data from the future!

But the definition of serializability places no constraints on the ordering of the transaction, for that you need a different isolation level: strict serializability. But we’re modeling serializability, not strict serializability, so we allow histories like the one above in our specification.

(I’d say “good luck actually implementing a system that can read events from the future”, but in distributed databases when you’re receiving updates from different nodes at different times, some pretty weird stuff can happen…)

If you’d like to follow along as we go, my Serializable TLA+ model is in the github repo (source, pdf).

Externally visible variablesMy specification will generate operations (e.g., reads, writes, commits, aborts). The four externally visible variables in the specification are:

Variable nameDescriptionopthe operation (read, write, commit, abort), modeled as a single letter: {“r”, “w”, “c”, “a”} )argthe argument(s) to the operationrvalthe return value of the operationtrthe transaction executing the operationHere’s the serializable example from earlier:

The execution history shown above can be modeled as a TLA+ behavior like this:

Initial state of the specification

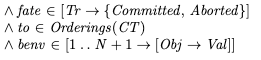

Initial state of the specificationWe need to specify the set of valid initial states. In the initial state of our spec, before any operations are issued, we determine:

which transactions will commit and which will abortthe order in which the transactions will occurthe value of the environment for each committed transaction at the beginning and at the end of its lifetimeThis is determined by using three internal variables whose values are set in the initial state:

VariableDescriptionfatefunction which encodes which transactions commit and which aborttotransaction orderbenvthe value of the environments at the beginning/end of each transactionWe couldn’t actually implement a system that could predict in advance whether a transaction will commit or abort, but it’s perfectly fine to use these for defining our specification.

The values of these variables are specified like this:

In our initial state, our specification chooses a fate, ordering, and begin/end environments for each transaction. Where Orderings is a helper operator:

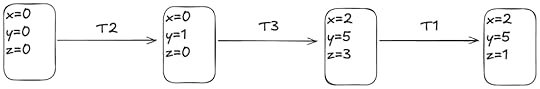

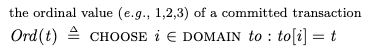

As an example, consider a behavior with three transactions fated to commit, where the fated transaction order is:

T2T3T1Furthermore, assume the following starting environments for each transaction:

T1: [x=2, y=5, z=3]

T2: [x=0, y=0, z=0]

T3: [x=0, y=1, z=0]

Finally, assume that the final environment state (once T1 completes) is [x=2,y=5,z=1].

We can visually depict the committed transactions like like this:

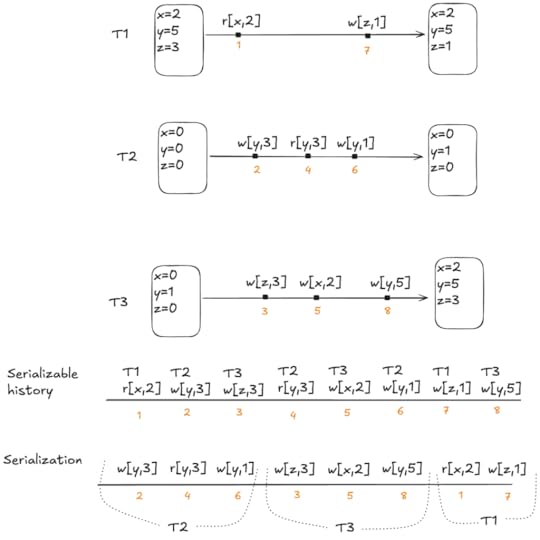

Reads and writes

Reads and writesYou can imagine each transaction running in parallel. As long as each transaction’s behavior is consistent with its initial environment, and it ends up with its final environment the resulting behavior will be serializable. Here’s an example.

Each transaction has a local environment, tenv. If the transaction is fated to commit, its tenv is initialized to its benv at the beginning:

where:

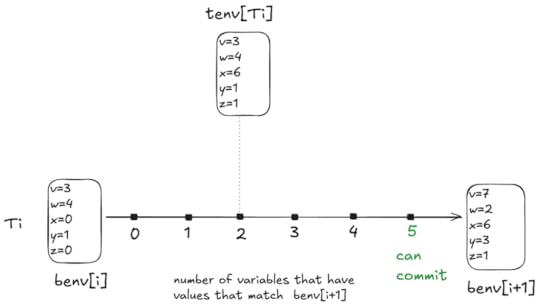

Here’s an example that shows how tenv for transaction T3 varies over time:

benv is fixed, but tenv for each transaction varies over time based on the writes

benv is fixed, but tenv for each transaction varies over time based on the writesIf the transaction is fated to abort, then we don’t track its environment in tenv, since any read or write is valid.

A valid behavior, as the definition of serializability places no constraints on the reads of an aborted transactionActions permitted by the specification

A valid behavior, as the definition of serializability places no constraints on the reads of an aborted transactionActions permitted by the specificationThe specification permits the following actions:

commit transactionabort transactionread a valuewrite a valueI’m not modeling the start of a transaction, because it’s not relevant to the definition of serializability. We just assume that all of the transactions have already started.

In TLA+, we specify it like this:

Note that there are no restrictions here on the order in which operations happen. Even if the transaction order is [T2, T3, T1], that doesn’t require that the operations from T2 have to be issued before the other two transactions.

Rather, the only constraints for each transaction that will commit is that:

Its reads must be consistent with its initial environment, as specified by benv.Its local environment must match the benv of the next transaction in the order when it finally commits.We enforce (1) in our specification by using a transaction-level environment, tenv, for the reads. This environment gets initialized to benv for each transaction, and is updated if the transaction does any writes. This enables each transaction to see its own writes.

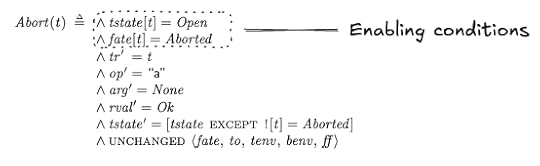

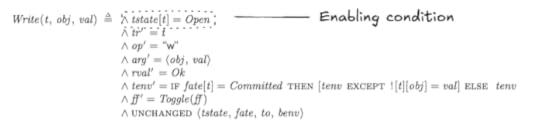

We enforce (2) by setting a precondition on the Commit action that it can only fire when tenv for that transaction is equal to benv of the next transaction:

Termination

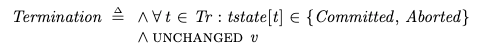

TerminationIf all of the transactions have committed or aborted, then the behavior is complete, which is modeled by the Termination sub-action, which just keeps firing and doesn’t change any of the variables:

Liveness

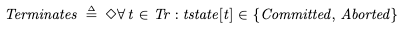

LivenessIn our specification, we want to ensure that every behavior eventually satisfies the Termination action. This means that all transactions either eventually commit or abort in every valid behavior of the spec. In TLA+, we can describe this desired property like this:

The diamond is a temporal operator that means “eventually”.

To achieve this property, we need to specify a liveness condition in our specification. This is a condition of the type “something we want to happen eventually happens”.

We don’t want our transactions to stay open forever.

For transactions that are fated to abort, they must eventually abortFor transactions that are fated to commit, they must eventually commitWe’re going to use weak and strong fairness to specify our liveness conditions; for more details on liveness and fairness, see my post a liveness example in TLA+.

Liveness for abortsWe want to specify that everyone transaction that is fated to abort eventually aborts. To do this, we can use weak fairness.

This says that “the Abort action cannot be forever enabled without the Abort action happening”.

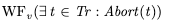

Here’s the Abort action.

The abort action is enabled for a transaction t if the transaction is in the open state, and its fate is Aborted.

Liveness for commitsThe liveness condition for commit is more subtle. A transaction can only commit if its local environment (tenv) matches the starting environment of the transaction that follows it in transaction order (benv).

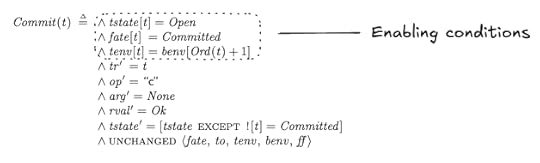

Consider two scenarios: one where tenv matches the next benv, and one where it doesn’t:

We want to use fairness to specify that every transaction fated to commit eventually reaches the state of scenario 1 above. Note that scenario 2 is a valid state in a behavior, it’s just not a state from which a commit can happen.

Consider the following diagram:

For every value of tenv[Ti], the number of variables that match the values in benv[i+1] is somewhere between 0 and 5. In the example above, there are two variables that match, x and z.

Note that the Commit action is always enabled when a transaction is open, so with every step of the specification, tenv can move left or right in the diagram above, with a min of 0 and a max of 5.

We need to specify “tenv always eventually moves to the right”. When tenv is at zero, we can use weak fairness to specify that it eventually moves from 0 to 1.

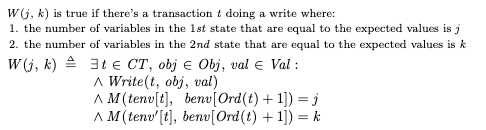

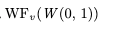

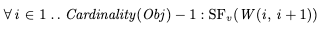

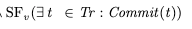

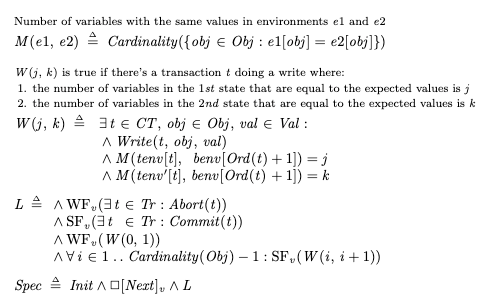

To specify this, I defined a function W(0, 1) which is true when tenv moves from 0 to 1:

Where M(env1, env2) is a count of the number of variables that have the same value:

This means we can specify “tenv cannot forever stay at 0” using weak fairness, like this:

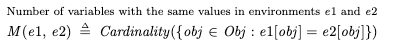

We also want to specify that tenv eventually moves from 1 matches to 2, and then from 2 to 3, and so on, all of the way from 4 to all 5. And then we also want to say that it eventually goes from all matches to commit.

We can’t use weak fairness for this, because if tenv is at 1, it can also change to 0. However, the weak fairness of W(0,1) ensures that it if it goes from 1 down to 0, it will always eventually go back to 1.

Instead, we need to use strong fairness, which says that “if the action is enabled infinitely often, then the action must be taken”. We can specify strong fairness for each of the steps like this:

Recall that Obj is the set of objects {x, y, z, …}, and Cardinality refres to the size of the set. We also need to specify strong fairness on the commit action, to ensure that we eventually commit if all variables matching is enabled infinitely often:

Now putting it all together, here’s one way to specify the liveness condition, which is conventionally called L.

Once again, the complete model is in the github repo (source, pdf).

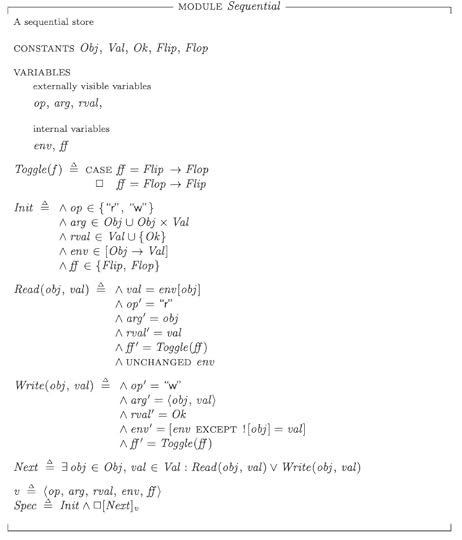

How do we know our spec is correct?We can validate our serializable specification by creating a refinement mapping to a sequential specification. Here’s a simple sequential specification for a key-value store, Sequential.tla:

I’m not going to get into the details of the refinement mapping in this post, but you can find it at in the SerializabilityRefinement model (source, pdf).

OK, but how do you know that this spec is correct?It’s turtles all of the way down! This is really the bottom in terms of refinement, I can’t think of an even simpler spec that we can use to validate this one.

However, one thing we can do is specify invariants that we can use to validate the specification, either with the model checker or by proof.

For example, here’s an invariant that checks whether each write has an associated read that happened before:

where:

But what happens if there’s no initial write? In that case, we don’t know what the read should be. But we do know that we don’t want to allow two successive reads to read different values, for example:

r[x,3], r[x,4]

So we can also specify this check as an invariant. I called that SuccessiveReads, you can find it in the MCSequential model (source, pdf).

The value of formalizing the specificationNow that we have a specification for Serializability, we can use it to check if a potential concurrency control implementation actually satisfies this specification.

That was my original plan for this blog post, but it got so long that I’m going to save that for a future blog post. In that future post, I’m going to model multi-version concurrency control (MVCC) and show how it fails to satisfy our serializability spec by having the model checker find a counterexample.

However, in my opinion, the advantage of formalizing a specification is that it forces you to think deeply about what it is that you’re specifying. Finding counter-examples with the model checker is neat, but the real value is the deeper understanding you’ll get.

October 17, 2024

If you don’t examine what worked, how will you know what works?

This is one of my favorite bits from fellow anglophone Québécois Norm McDonald:

Norm: not a lung expertOne of the goals I believe that we all share for post-incident work is to improve the system. For example, when I wrote the post Why I don’t like discussing action items during incident reviews, I understood why people would want to focus on action items: precisely because they share this goal of wanting to improve the system (As a side note, Chris Evans of incident.io wrote a response: Why I like discussing actions items in incident reviews). However, what I want to write about here is not the discussion of action items, but focusing on what went wrong versus what went right.

“How did things go right?”How did things go right is a question originally posed by the safety researcher Erik Hollnagel, in his the safety paradigm that he calls Safety-II. The central idea is that things actually go right most of the time, and if you want to actually improve the system, you need to get a better understanding of how the system functions, which means you need to broaden your focus beyond the things that broke.

You can find an approachable introduction to Safety-II concepts in the EUROCONTROL white paper From Safety-I to Safety-II. Hollnagel’s ideas have been very influential in the resilience engineering community. As an example, check out my my former colleague Ryan Kitchens’s talk at SREcon Americas 2019: How Did Things Go Right? Learning More from Incidents.

It’s with this how did things go right lens that I want to talk a little bit about incident review.

Beyond “what went well”Now, in most incident writeups that I’ve read, there is a “what went well” section. However, it’s typically the smallest section in the writeup, with maybe a few bullet points: there’s never any real detail there.

Personally, I’m looking for details like how an experienced engineer recognized the symptoms enough to get a hunch about where to look next, reducing the diagnostic time by hours. Or how engineers leveraged an operational knob that was originally designed for a different purpose. I want to understand how experts are able to do the work of effectively diagnosing problems, mitigating impact, and remediating the problem.

Narrowly, I want to learn this because I want to get this sort of working knowledge into other people’s heads. More broadly, I want to bring to light the actual work that gets done.

We don’t know how the system worksHumans adapt to the constraints they face in order to get their work done. Look for these adaptations if you want to understand the work better.

— @norootcause@hachyderm.io on mastodon (@norootcause) October 13, 2024

Safety researchers make a distinction between work-as-imagined and work-as-done. We think we understand how the day-to-day work gets done, but we actually don’t. Not really. To take an example from software, we don’t actually know how people really use the tooling to get their work done, and I can confirm this by being on-call for internal support for development tools in previous jobs. (“You’re using our tool to do what?” is not an uncommon reaction from the on-call person). People do things we never imagined, in both wonderful and horrifying ways (sometimes at the same time!).

We also don’t see all of the ways that people coordinate to get their work done. There are the meetings, the slack messages, the comments on the pull requests, but there’s also the shared understanding, the common knowledge, the stuff that everybody knows that everybody else knows, that enables people to get this work done, while reducing the amount of explicit communication that has to happen.

What’s remarkable is that these work patterns, well, they work. These people in your org are able to get their stuff done, almost all of the time. Some of them may exhibit mastery of the tooling, and others may use the tooling in ways even it was never intended that are fundamentally unsafe. But we’re never going to actually know unless we actually look at how they’re doing their work.

Because how people do their work is how the system works. And if we’re going to propose and implement interventions, it’s very likely that the outcomes of the interventions will surprise us, because these changes might disrupt effective ways of doing work, and people will adapt to those interventions in ways we never anticipated, and in ways we may never even know if we don’t take a look.

Then why use incidents to look at things that go right?At first glance, it does seem odd to use incidents as the place to examine where work goes well: given that incidents are times where something unquestionably went wrong. It would be wonderful if we could study how work happens when things are going well. Heck, I’d love to see companies have sociologists or anthropologists on staff to study how the work happens at the company. Regrettably, though, incidents are one of the only times when the organization is actually willing to devote resources (specifically, time) on examining work in fine-grained detail.

We can use incidents to study how things go well, but we have to keep a couple of things in mind. One, we need to recognize that adaptations that fail led to an incident are usually successful, which is why people developed those adaptations. Note that because an adaptation usually works, doesn’t mean that it’s a good thing to keep doing: an adaptation could be a dangerous workaround to a constraint like a third-party system that can’t be changed directly and so must be awkwardly worked around.

Second, we need to look in more detail, to remark, at incident response that is remarkable. When incident response goes well, there is impressive diagnostic, coordination, and improvisation work to get the system back to healthy. These are the kinds of skills you want to foster across your organization. If you want to build tools to make this work even better, you should take the time to understand just how this work is done today. Keep this in mind when you’re proposing new interventions. After all, if you don’t examine what worked, how will you know what works?

October 16, 2024

A liveness example in TLA+

If you’ve ever sat at a stop light that was just stuck on red, where there was clearly a problem with the light where it wasn’t ever switching green, you’ve encountered a liveness problem with a system.

Is the turning light just taking a long time? Or is it broken?

Is the turning light just taking a long time? Or is it broken?A liveness property of a specification is an assertion that some good thing eventually happens. In the case above, the something good is the light changing from red to green. If the light never turns green, then the system’s behavior violates the liveness property.

On the other hand, a safety property is an assertion that some bad thing never happens. To continue with the stop light example, you never want both the north-south and east-west traffic lights to be green at the same time. If those lights are both ever green simultaneously, then the system’s behavior violates the safety property. But this post is about liveness, not safety. I

I’m going to walk through a simple TLA example that demonstrates why and how to specify liveness properties. Instead of using stop lights as my example, I’m going to use elevators.

A simple elevator specificationI’m going to build a minimalist TLA model of an elevator system. I’m going to model a building with N floors, and a single elevator, where the elevator is always either:

at a floorbetween two floorsTo keep things very simple, I’m not going to model things like passengers, doors, or call buttons. I’m just going to assume the elevator moves up and down in the building on its own.

To start with, the only constraint I’m going to put on the way the elevator moves is that it can’t change directions when it’s between two floors. For example, if the elevator is on floor 2, and then starts moving up, and is between floors 2 and 3, it can’t change direction and go back to floor 2: it has to continue on to floor 3. Once it’s on floor 3, it can go up or down. (Note: this is an example of a safety property).

My model is going to have two variables:

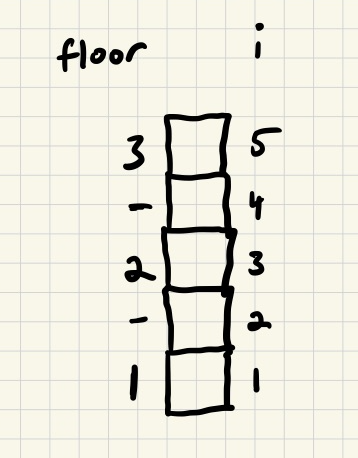

i – a natural number between 1 and 2*(# of floors) – 1dir – the direction that the elevator is moving in (Up or Dn)Assume we are modeling a building with 3 floors, then i would range from 1 to 5, and here’s how we would determine the floor that the elevator was on based on i.

ifloor112between 1 and 2324between 2 and 353Note that when i is odd, the elevator is at a floor, and when even, the elevator is between floors. I use a hyphen (-) to indicate when the elevator is between floors.

Here’s a TLA specification that describes how this elevator moves. There are four actions:

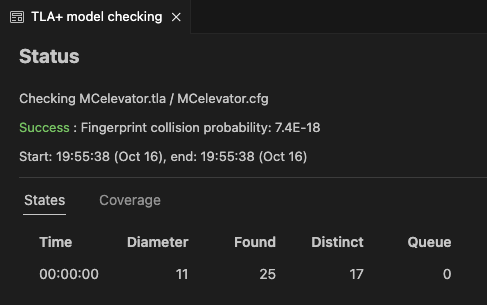

UpFlr – move up when at a floorUpBetween – move up when between floorsDnFlr – move down when at a floorDnBetween – move down when between floors---- MODULE elevator ----EXTENDS NaturalsCONSTANTS N, Up, DnASSUME N \in NatVARIABLES i, dir(* True when elevator is at floor f *)At(f) == i 1 = 2*f(* True when elevator is between floors *)IsBetween == i % 2 = 0Init == /\ i = 1 /\ dir \in {Up, Dn}(* move up when at a floor *)UpFlr == /\ \E f \in 1..N-1 : At(f) /\ i' = i 1 /\ dir' = Up(* move up when between floors *)UpBetween == /\ IsBetween /\ dir = Up /\ i' = i 1 /\ UNCHANGED dir(* move down when at a floor *)DnFlr == /\ \E f \in 2..N : At(f) /\ i' = i-1 /\ dir' = Dn(* move down when between floors *)DnBetween == /\ IsBetween /\ dir = Dn /\ i' = i - 1 /\ UNCHANGED dirNext == \/ UpFlr \/ UpBetween \/ DnFlr \/ DnBetweenv == <>Spec == Init /\ [][Next]_v====Avoiding getting stuckOne thing we don’t want to happen is for the elevator to get stuck forever between two floors.

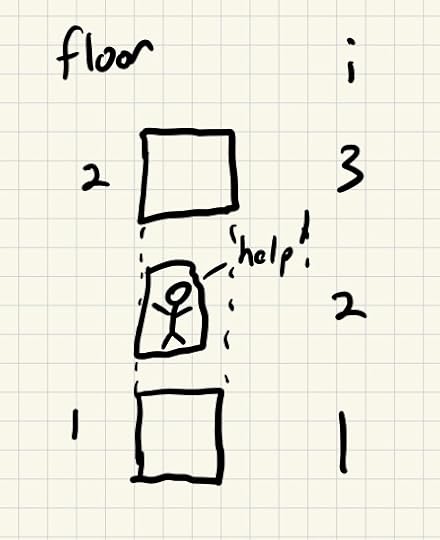

We’re trying to avoid this happening forever

We’re trying to avoid this happening foreverGetting stuck is an example of a liveness condition. It’s fine for the elevator to sometimes be in the state i=2. we just want to ensure that it never stays in that state forever.

We can express this desired property using temporal logic. I’m going to use the diamond <> operator, which means “eventually”, and the box [] operator, which means “always”. Here’s how I expressed the desired property that the elevator doesn’t get stuck:

GetsStuckBetweenFloors == <>[]IsBetweenDoesntGetsStuckBetweenFloors == ~GetsStuckBetweenFloorsIn English, GetsStuckBetweenFloors states: eventually, the elevator is always between floors. And then we define DoesntGetsStuckBetweenFloors as the negation of that.

We can check this property in the TLC model checker, by specifying it as a property in the config file:

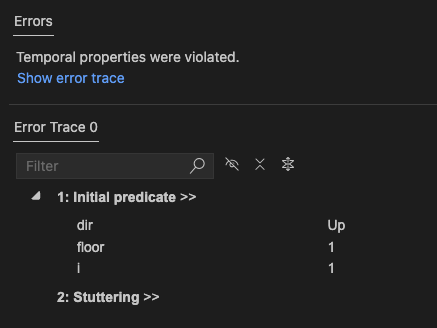

PROPERTY DoesntGetsStuckBetweenFloorsIf we check this with the spec from above, the model checker will find a behavior that is permitted by our specification, but that violates this property.

The behavior looks like this, floor: [1, -, -, -, …]. The elevator moves up between floors and then gets stuck there, exactly what we don’t want to happen.

Our specification as initially written does not prevent this kind of behavior. We need to add additional constraints to our specification to prevent the elevator from getting stuck.

Specifying liveness with fairness propertiesOne thing we could do is simply conjoin the DoesntGetsStuckBetweenFloors property to our specification.

Spec == Init /\ [][Next]_v /\ ~<>[]IsBetweenThis would achieve the desired effect, our spec would know longer permit behaviors where the elevator gets stuck between floors.

The problem with adding liveness constraints by adding an arbitrary temporal property to your spec is that you can end up unintentionally adding additional safety constraints to your spec. That makes your spec harder to reason about. Lamport provides a detailed example of how this can happen in chapter 4 of his book A Science of Concurrent Programs.

Conjoining arbitrary temporal logic expressions to your specification to specify liveness properties makes Leslie Lamport sad

Conjoining arbitrary temporal logic expressions to your specification to specify liveness properties makes Leslie Lamport sadIn order to make it easier for a human to reason about a specification, we always want to keep our safety properties and our liveness properties separate. This means that when we add liveness properties to our spec, we want to guarantee that we don’t do it in such a way that we end up adding new safety properties as well.

We can ensure that we don’t accidentally sneak in any new safety properties by using what are called fairness properties to achieves our desired liveness property.

Using weak fairness to avoid getting stuckWeak fairness of an action says that if the action A is forever enabled, then eventually there is an A step. That’s not a very intuitive concept, so I find the contrapositive more useful. If WF_i(A) is true, then it cannot be that the system gets “stuck” forever in a state where it could take an A step, but doesn’t. We write it as:

WF_v(A)This means that it can’t happen that A eventually becomes forever enabled without eventually taking an A step that changes the variable expression v.

We have two actions that fire when the elevator is between floors: UpBetween (when it’s between floors, going up), and DnBetween (when it’s between floors going down).

We can define our liveness condition like this:

L == WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween)Spec == Init /\ [][Next]_v /\ LThis says that if the model cannot be in a state forever where UpBetween is enabled but the UpBetween action never happens, and similarly for DnBetween.

And now the model checker returns success!

Visiting every floor

Visiting every floorIn our specification, we’d also like to guarantee that the elevator always eventually visits every floor, so that nobody is ever eternally stranded waiting for an elevator to arrive.

Here’s how I wrote this property: it’s always that true that, for every floor, the elevator eventually visits that floor:

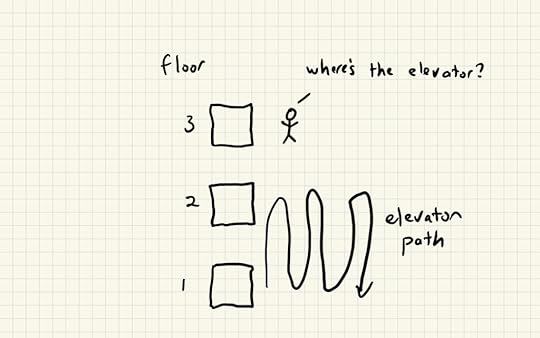

VisitsEveryFloor == [] \A f \in 1..N : <>At(f)If we check this property against our spec with TLC, it quickly finds a counterexample, the scenario where the elevator just sits on the ground floor forever! It looks like this: floor [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, ….]

We previously added weak fairness constraints for when the elevator is between floors. We can add additional fairness constraints so that the elevator can’t get stuck on any floors, that if it can move up or down, it has to eventually do so. Our liveness condition would look like this:

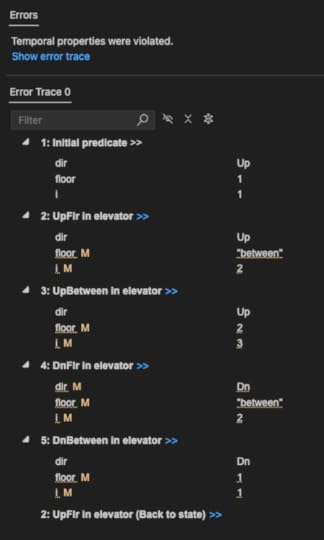

L == /\ WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween) /\ WF_v(UpFlr) /\ WF_v(DnFlr)But adding these fairness conditions don’t satisfy the VisitsEveryFloor property either! Here’s the counterexample:

In this counter-example, the behavior looks like this: floor [1, -, 2, -, 1, -, 2, -, …]. The elevator is cycling back and forth between floor 1 and floor 2. In particular, it never goes up past floor 2. We need to specify fairness conditions to prohibit a behavior like this.

Weak fairness doesn’t work here because the problem isn’t that the elevator is getting stuck forever on floor 2. Instead, it’s forever going back and forth between floors 1 and 2.

The elevator isn’t getting stuck, but it also is never going to floor 3

The elevator isn’t getting stuck, but it also is never going to floor 3There’s a different fairness property, called strong fairness, which is similar to weak fairness, except that it also applies not just if the system gets stuck forever in a state, but also if a system goes in and out of that state, as long as it enters that state “infinitely often”. Basically, if it toggles forever in and out of that state, then you can use strong fairness to enforce an action in that state.

Which is exactly what the case is with our elevator, we want to assert that if the elevator reaches floor 2 infinitely often, it should eventually keep going up. We could express that using strong fairness like this:

SF_v(UpFlr /\ At(2))Except that we don’t want this fairness condition to only apply at floor 2: we want it to apply for every floor (except the top floor). We can write it like this:

\A f \in 1..N-1: SF_v(UpFlr /\ At(f))If we run the model checker again (where N=3), it still finds a counter-example(!):

Now the elevator does this: [1, -, 2, -, 3, 3, 3, 3, …]. It goes to the top floor and just stays there. It hits every floor once, but that’s not good enough for us: we want it to always eventually hit every floor.

We need to add some additional fairness conditions so that it the elevator also always eventually goes back down. Our liveness condition now looks like this:

L == /\ WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween) /\ \A f \in 1..N-1: SF_v(UpFlr /\ At(f)) /\ \A f \in 2..N: SF_v(DnFlr /\ At(f))And this works!

Weak fairness on UpFlr and DnFlr is actually sufficient to prevent the elevators from getting stuck at the bottom or top floor, but we need strong fairness in the middle floors to ensure that the elevators always eventually visit every single floor.

The final liveness condition I used was this:

L == /\ WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween) /\ WF_v(UpFlr /\ At(1)) /\ WF_v(DnFlr /\ At(N)) /\ \A f \in 2..N-1 : /\ SF_v(UpFlr /\ At(f)) /\ SF_v(DnFlr /\ At(f))You can find my elevator-tla repo on GitHub, including the config files for checking the model using TLC.

Why we need to specify fairness for each floorYou might be wondering why we need to specify the (strong) fairness condition for every floor. Instead of doing:

L == /\ WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween) /\ WF_v(UpFlr) /\ WF_v(DnFlr) /\ \A f \in 2..N-1 : /\ SF_i(UpFlr /\ At(f)) /\ SF_i(DnFlr /\ At(f))Why can’t we just specify strong fairness of the UpFlr and DnFlr actions?

L == /\ WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween) /\ SF_v(UpFlr) /\ SF_v(DnFlr)The model checker can provide us with a counterexample to help explain why this liveness property doesn’t guarantee that the elevator always eventually visits all floors:

Here’s the pattern: [1,-,2,-,1,-,2,-,1,…]. We saw this behavior earlier, where the elevator just moves back and forth between floor 1 and floor 2.

The problem is that both SF_v(UpFlr) and SF_v(DnFlr) are satisfied by this behavior, because the elevator always eventually goes up (from floor 1) and always eventually goes down (from floor 2).

If we want the elevator to eventually visit every floor, then we need to specify the fairness conditions separately for each floor.

Further readingHillel Wayne’s blog posts are always a great introduction to TLA concepts:

Safety and liveness propertiesWeak and strong fairnessFor more details on implementing liveness properties in TLA , I recommend Leslie Lamport’s book A Science of Concurrent Programs.

Finally, if you are interested in what a more realistic elevator model looks like in TLA , check out Andrew Helwer’s MultiCarElevator example.

October 5, 2024

Futexes in TLA+

Justine Tunney recently wrote a blog post titled The Fastest Mutexes where she describes how she implemented mutexes in Cosmopolitan Libc. The post discusses how her implementation uses futexes by way of Mike Burrows’s nsync library. From her post

nsync enlists the help of the operating system by using futexes. This is a great abstraction invented by Linux some years ago, that quickly found its way into other OSes. On MacOS, futexes are called ulock. On Windows, futexes are called WaitOnAddress(). The only OS Cosmo supports that doesn’t have futexes is NetBSD, which implements POSIX semaphores in kernelspace, and each semaphore sadly requires creating a new file descriptor. But the important thing about futexes and semaphores is they allow the OS to put a thread to sleep. That’s what lets nsync avoid consuming CPU time when there’s nothing to do.

Before I read this post, I had no idea what futexes were or how they worked. I figured a good way to learn would be to model them in TLA+.

Note: I’m going to give a simplified account of how futexes work. In addition, I’m not an expert on this topic. In particular, I’m not a kernel programmer, so there may be important details I get wrong here.