A liveness example in TLA+

If you’ve ever sat at a stop light that was just stuck on red, where there was clearly a problem with the light where it wasn’t ever switching green, you’ve encountered a liveness problem with a system.

Is the turning light just taking a long time? Or is it broken?

Is the turning light just taking a long time? Or is it broken?A liveness property of a specification is an assertion that some good thing eventually happens. In the case above, the something good is the light changing from red to green. If the light never turns green, then the system’s behavior violates the liveness property.

On the other hand, a safety property is an assertion that some bad thing never happens. To continue with the stop light example, you never want both the north-south and east-west traffic lights to be green at the same time. If those lights are both ever green simultaneously, then the system’s behavior violates the safety property. But this post is about liveness, not safety. I

I’m going to walk through a simple TLA example that demonstrates why and how to specify liveness properties. Instead of using stop lights as my example, I’m going to use elevators.

A simple elevator specificationI’m going to build a minimalist TLA model of an elevator system. I’m going to model a building with N floors, and a single elevator, where the elevator is always either:

at a floorbetween two floorsTo keep things very simple, I’m not going to model things like passengers, doors, or call buttons. I’m just going to assume the elevator moves up and down in the building on its own.

To start with, the only constraint I’m going to put on the way the elevator moves is that it can’t change directions when it’s between two floors. For example, if the elevator is on floor 2, and then starts moving up, and is between floors 2 and 3, it can’t change direction and go back to floor 2: it has to continue on to floor 3. Once it’s on floor 3, it can go up or down. (Note: this is an example of a safety property).

My model is going to have two variables:

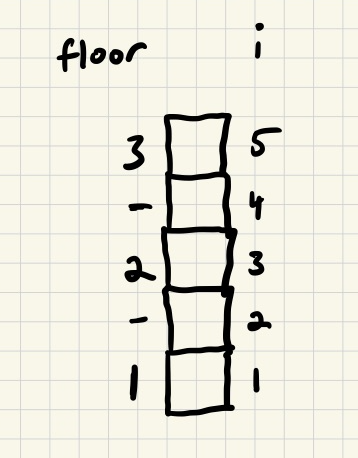

i – a natural number between 1 and 2*(# of floors) – 1dir – the direction that the elevator is moving in (Up or Dn)Assume we are modeling a building with 3 floors, then i would range from 1 to 5, and here’s how we would determine the floor that the elevator was on based on i.

ifloor112between 1 and 2324between 2 and 353Note that when i is odd, the elevator is at a floor, and when even, the elevator is between floors. I use a hyphen (-) to indicate when the elevator is between floors.

Here’s a TLA specification that describes how this elevator moves. There are four actions:

UpFlr – move up when at a floorUpBetween – move up when between floorsDnFlr – move down when at a floorDnBetween – move down when between floors---- MODULE elevator ----EXTENDS NaturalsCONSTANTS N, Up, DnASSUME N \in NatVARIABLES i, dir(* True when elevator is at floor f *)At(f) == i 1 = 2*f(* True when elevator is between floors *)IsBetween == i % 2 = 0Init == /\ i = 1 /\ dir \in {Up, Dn}(* move up when at a floor *)UpFlr == /\ \E f \in 1..N-1 : At(f) /\ i' = i 1 /\ dir' = Up(* move up when between floors *)UpBetween == /\ IsBetween /\ dir = Up /\ i' = i 1 /\ UNCHANGED dir(* move down when at a floor *)DnFlr == /\ \E f \in 2..N : At(f) /\ i' = i-1 /\ dir' = Dn(* move down when between floors *)DnBetween == /\ IsBetween /\ dir = Dn /\ i' = i - 1 /\ UNCHANGED dirNext == \/ UpFlr \/ UpBetween \/ DnFlr \/ DnBetweenv == <>Spec == Init /\ [][Next]_v====Avoiding getting stuckOne thing we don’t want to happen is for the elevator to get stuck forever between two floors.

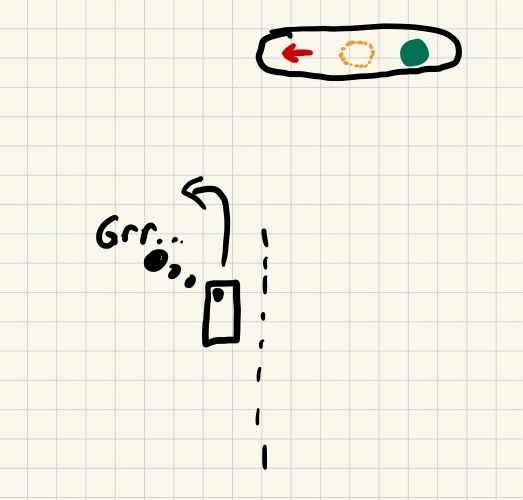

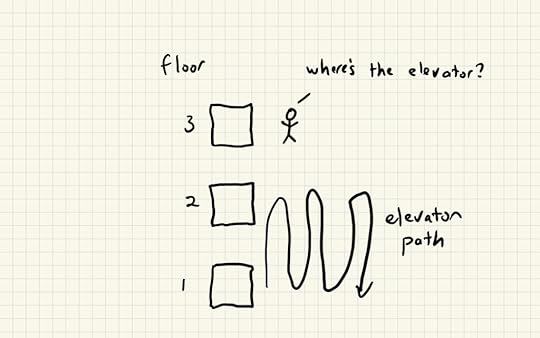

We’re trying to avoid this happening forever

We’re trying to avoid this happening foreverGetting stuck is an example of a liveness condition. It’s fine for the elevator to sometimes be in the state i=2. we just want to ensure that it never stays in that state forever.

We can express this desired property using temporal logic. I’m going to use the diamond <> operator, which means “eventually”, and the box [] operator, which means “always”. Here’s how I expressed the desired property that the elevator doesn’t get stuck:

GetsStuckBetweenFloors == <>[]IsBetweenDoesntGetsStuckBetweenFloors == ~GetsStuckBetweenFloorsIn English, GetsStuckBetweenFloors states: eventually, the elevator is always between floors. And then we define DoesntGetsStuckBetweenFloors as the negation of that.

We can check this property in the TLC model checker, by specifying it as a property in the config file:

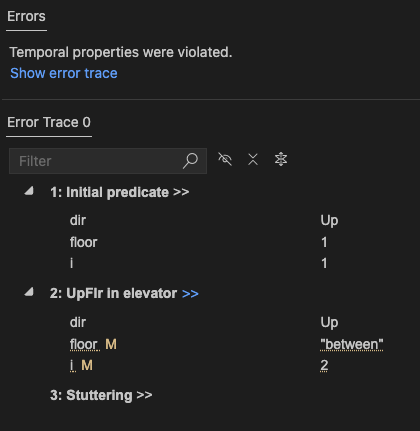

PROPERTY DoesntGetsStuckBetweenFloorsIf we check this with the spec from above, the model checker will find a behavior that is permitted by our specification, but that violates this property.

The behavior looks like this, floor: [1, -, -, -, …]. The elevator moves up between floors and then gets stuck there, exactly what we don’t want to happen.

Our specification as initially written does not prevent this kind of behavior. We need to add additional constraints to our specification to prevent the elevator from getting stuck.

Specifying liveness with fairness propertiesOne thing we could do is simply conjoin the DoesntGetsStuckBetweenFloors property to our specification.

Spec == Init /\ [][Next]_v /\ ~<>[]IsBetweenThis would achieve the desired effect, our spec would know longer permit behaviors where the elevator gets stuck between floors.

The problem with adding liveness constraints by adding an arbitrary temporal property to your spec is that you can end up unintentionally adding additional safety constraints to your spec. That makes your spec harder to reason about. Lamport provides a detailed example of how this can happen in chapter 4 of his book A Science of Concurrent Programs.

Conjoining arbitrary temporal logic expressions to your specification to specify liveness properties makes Leslie Lamport sad

Conjoining arbitrary temporal logic expressions to your specification to specify liveness properties makes Leslie Lamport sadIn order to make it easier for a human to reason about a specification, we always want to keep our safety properties and our liveness properties separate. This means that when we add liveness properties to our spec, we want to guarantee that we don’t do it in such a way that we end up adding new safety properties as well.

We can ensure that we don’t accidentally sneak in any new safety properties by using what are called fairness properties to achieves our desired liveness property.

Using weak fairness to avoid getting stuckWeak fairness of an action says that if the action A is forever enabled, then eventually there is an A step. That’s not a very intuitive concept, so I find the contrapositive more useful. If WF_i(A) is true, then it cannot be that the system gets “stuck” forever in a state where it could take an A step, but doesn’t. We write it as:

WF_v(A)This means that it can’t happen that A eventually becomes forever enabled without eventually taking an A step that changes the variable expression v.

We have two actions that fire when the elevator is between floors: UpBetween (when it’s between floors, going up), and DnBetween (when it’s between floors going down).

We can define our liveness condition like this:

L == WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween)Spec == Init /\ [][Next]_v /\ LThis says that if the model cannot be in a state forever where UpBetween is enabled but the UpBetween action never happens, and similarly for DnBetween.

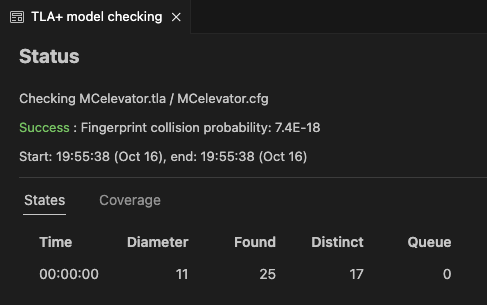

And now the model checker returns success!

Visiting every floor

Visiting every floorIn our specification, we’d also like to guarantee that the elevator always eventually visits every floor, so that nobody is ever eternally stranded waiting for an elevator to arrive.

Here’s how I wrote this property: it’s always that true that, for every floor, the elevator eventually visits that floor:

VisitsEveryFloor == [] \A f \in 1..N : <>At(f)If we check this property against our spec with TLC, it quickly finds a counterexample, the scenario where the elevator just sits on the ground floor forever! It looks like this: floor [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, ….]

We previously added weak fairness constraints for when the elevator is between floors. We can add additional fairness constraints so that the elevator can’t get stuck on any floors, that if it can move up or down, it has to eventually do so. Our liveness condition would look like this:

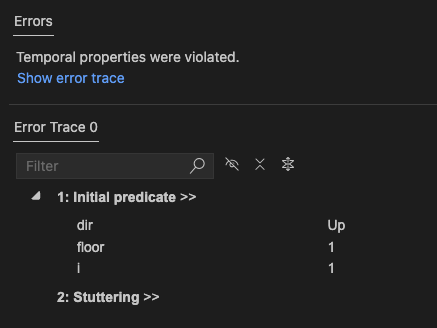

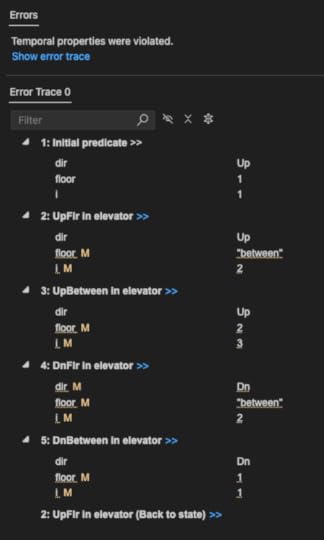

L == /\ WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween) /\ WF_v(UpFlr) /\ WF_v(DnFlr)But adding these fairness conditions don’t satisfy the VisitsEveryFloor property either! Here’s the counterexample:

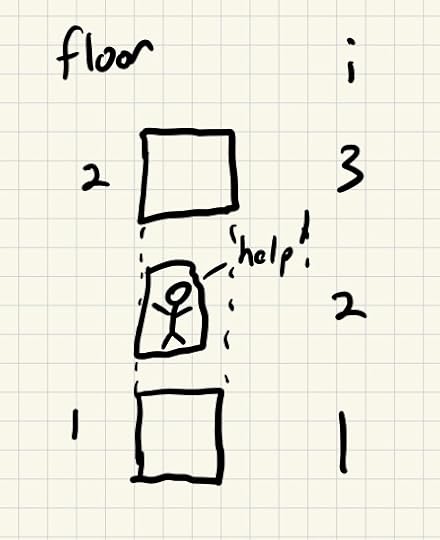

In this counter-example, the behavior looks like this: floor [1, -, 2, -, 1, -, 2, -, …]. The elevator is cycling back and forth between floor 1 and floor 2. In particular, it never goes up past floor 2. We need to specify fairness conditions to prohibit a behavior like this.

Weak fairness doesn’t work here because the problem isn’t that the elevator is getting stuck forever on floor 2. Instead, it’s forever going back and forth between floors 1 and 2.

The elevator isn’t getting stuck, but it also is never going to floor 3

The elevator isn’t getting stuck, but it also is never going to floor 3There’s a different fairness property, called strong fairness, which is similar to weak fairness, except that it also applies not just if the system gets stuck forever in a state, but also if a system goes in and out of that state, as long as it enters that state “infinitely often”. Basically, if it toggles forever in and out of that state, then you can use strong fairness to enforce an action in that state.

Which is exactly what the case is with our elevator, we want to assert that if the elevator reaches floor 2 infinitely often, it should eventually keep going up. We could express that using strong fairness like this:

SF_v(UpFlr /\ At(2))Except that we don’t want this fairness condition to only apply at floor 2: we want it to apply for every floor (except the top floor). We can write it like this:

\A f \in 1..N-1: SF_v(UpFlr /\ At(f))If we run the model checker again (where N=3), it still finds a counter-example(!):

Now the elevator does this: [1, -, 2, -, 3, 3, 3, 3, …]. It goes to the top floor and just stays there. It hits every floor once, but that’s not good enough for us: we want it to always eventually hit every floor.

We need to add some additional fairness conditions so that it the elevator also always eventually goes back down. Our liveness condition now looks like this:

L == /\ WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween) /\ \A f \in 1..N-1: SF_v(UpFlr /\ At(f)) /\ \A f \in 2..N: SF_v(DnFlr /\ At(f))And this works!

Weak fairness on UpFlr and DnFlr is actually sufficient to prevent the elevators from getting stuck at the bottom or top floor, but we need strong fairness in the middle floors to ensure that the elevators always eventually visit every single floor.

The final liveness condition I used was this:

L == /\ WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween) /\ WF_v(UpFlr /\ At(1)) /\ WF_v(DnFlr /\ At(N)) /\ \A f \in 2..N-1 : /\ SF_v(UpFlr /\ At(f)) /\ SF_v(DnFlr /\ At(f))You can find my elevator-tla repo on GitHub, including the config files for checking the model using TLC.

Why we need to specify fairness for each floorYou might be wondering why we need to specify the (strong) fairness condition for every floor. Instead of doing:

L == /\ WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween) /\ WF_v(UpFlr) /\ WF_v(DnFlr) /\ \A f \in 2..N-1 : /\ SF_i(UpFlr /\ At(f)) /\ SF_i(DnFlr /\ At(f))Why can’t we just specify strong fairness of the UpFlr and DnFlr actions?

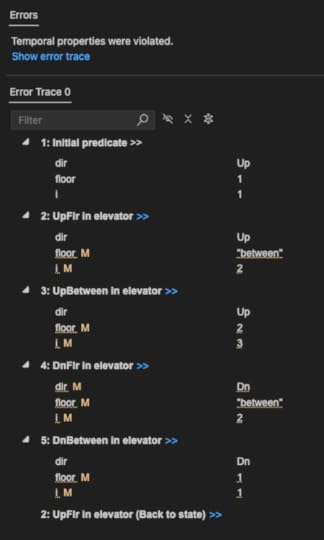

L == /\ WF_v(UpBetween) /\ WF_v(DnBetween) /\ SF_v(UpFlr) /\ SF_v(DnFlr)The model checker can provide us with a counterexample to help explain why this liveness property doesn’t guarantee that the elevator always eventually visits all floors:

Here’s the pattern: [1,-,2,-,1,-,2,-,1,…]. We saw this behavior earlier, where the elevator just moves back and forth between floor 1 and floor 2.

The problem is that both SF_v(UpFlr) and SF_v(DnFlr) are satisfied by this behavior, because the elevator always eventually goes up (from floor 1) and always eventually goes down (from floor 2).

If we want the elevator to eventually visit every floor, then we need to specify the fairness conditions separately for each floor.

Further readingHillel Wayne’s blog posts are always a great introduction to TLA concepts:

Safety and liveness propertiesWeak and strong fairnessFor more details on implementing liveness properties in TLA , I recommend Leslie Lamport’s book A Science of Concurrent Programs.

Finally, if you are interested in what a more realistic elevator model looks like in TLA , check out Andrew Helwer’s MultiCarElevator example.