Specifying serializability in TLA+

Concurrency is really, really difficult for humans to reason about. TLA+ itself was borne out of Leslie Lamport’s frustration with the difficulty of write error-free concurrent algorithms:

When I first learned about the mutual exclusion problem, it seemed easy and the published algorithms seemed needlessly complicated. So, I dashed off a simple algorithm and submitted it to CACM. I soon received a referee’s report pointing out the error. This had two effects. First, it made me mad enough at myself to sit down and come up with a real solution. The result was the bakery algorithm described in [12]. The second effect was to arouse my interest in verifying concurrent algorithms.

Modeling concurrency control in database systems is a great use case for TLA+, so I decided to learn use TLA+ to learn more about database isolation. This post is about modeling serializability.

You can find all of the the TLA+ models referenced in this post in my snapshot-isolation-tla repo. This post isn’t about snapshot isolation at all, so think of the name as a bit of foreshadowing of a future blog post, which we’ll discuss at the end.

Modeling a database for reasoning about transaction isolationIn relational databases, data is modeled as rows in different tables, where each table has a defined set of named columns, and there are foreign key relationships between the tables.

However, when modeling transaction isolation, we don’t need to worry about those details. For the purpose of a transaction, all we care about is if any of the columns of a particular row are read or modified. This means we can ignore details about tables, columns, and relations. All we care about are the rows.

The transaction isolation literature talks about objects instead of rows, and that’s the convention I’m going to use. Think of an object like a variable that is assigned a value, and that assignment can change over time. A SQL select statement is a read, and a SQL update statement is a write.

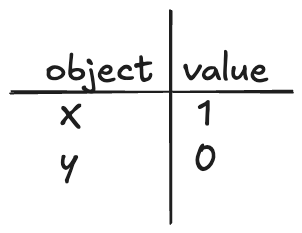

An example of how we’re modeling the database

An example of how we’re modeling the databaseNote that the set of objects is fixed during the lifetime of the model, it’s only the values that change over time. I’m only going to model reads and writes, but it’s simple enough to extend this model to support creation and deletion by writing a tombstone value to model deletion, and having a not-yet-created-stone value to model an object that has not yet been created in the database.

I’ll use the notation r[obj, val] to refer to a read operation where we read the object obj and get the value val and w[obj, val] to mean where we write the value val to obj. So, for example, setting x=1 would be: w[x, 1], and reading the value of x as 1 would be r[x, 1].

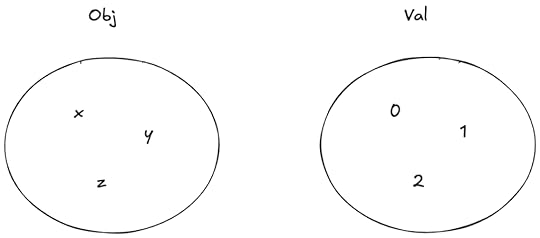

I’m going to use Obj to model the set of objects, and Val to model the set of possible values that objects can take on.

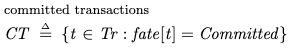

Obj is the set of objects, Val is the set of values that can be assigned to objects

Obj is the set of objects, Val is the set of values that can be assigned to objectsWe can model the values of the objects at any point in time as a function that maps objects to values. I’ll call these sorts of functions environments (env for short) since that’s what people who write interpreters call them.

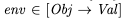

Example of an environment

Example of an environmentAs an example of syntax, here’s how we would assert in TLA+ that the variable env is a function that maps element of the set Obj to elements of the set Val:

What is serializability?

What is serializability?Here’s how the SQL:1999 standard describes serializability (via the Jepsen serializability page):

The execution of concurrent SQL-transactions at isolation level SERIALIZABLE is guaranteed to be serializable. A serializable execution is defined to be an execution of the operations of concurrently executing SQL-transactions that produces the same effect as some serial execution of those same SQL-transactions. A serial execution is one in which each SQL-transaction executes to completion before the next SQL-transaction begins.

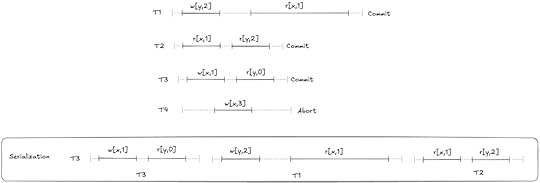

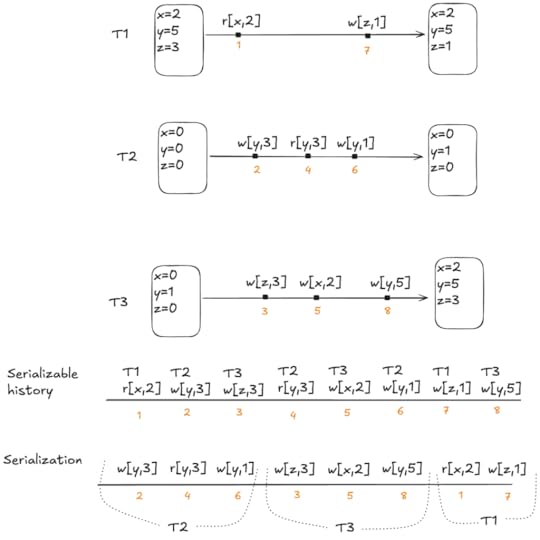

An execution history of reads and writes is serializable if it is equivalent to some other execution history where the committed transactions are scheduled serially (i.e., they don’t overlap in time). Here’s an example of a serializable execution history.

Atul Adya famously came up with a formalism for database isolation levels (including serializability) in his PhD dissertation work, and published this in a paper co-authored by Barbara Liskov (his PhD advisor) and Patrick O’Neil (an author of the original log-structured merge-tree paper and one of the co-authors of the paper A Critique of ANSI SQL Isolation Levels, which pointed out problems in the SQL specification’s definitions of the isolation levels ).

Specifying serializabilityAdya formalized database isolation levels by specifying dependencies between transactions. However, I’m not going to use Adya’s approach for my specification. Instead, I’m going to use a state-based approach, like the one used by Natacha Crooks, Youer Pu, Lorenzo Alvisi and Allen Clement in their paper Seeing is Believing: A Client-Centric Specification of Database Isolation.

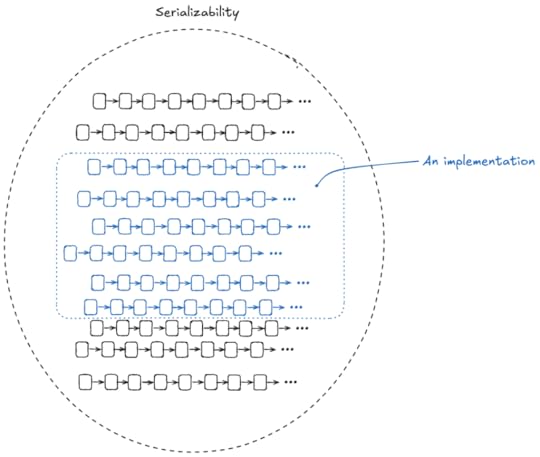

It’s important to remember that a specification is just a set of behaviors (series of state transitions). We’re going to use TLA+ to define the set of all of the behaviors that we consider valid for serializability. Another way to put that is that our specification is the set of all serializable executions.

We want to make sure that if we build an implementation, all of the behaviors permitted by the implementation are a subset of our serializability specification.

Note: Causality is not required

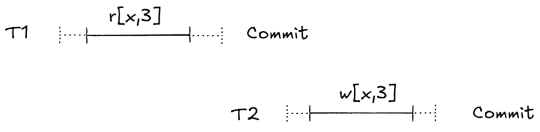

Note: Causality is not requiredHere’s an example of an execution history that is serializable according to the definition:

This looks weird to us because the write happens after the read: T1 is reading data from the future!

But the definition of serializability places no constraints on the ordering of the transaction, for that you need a different isolation level: strict serializability. But we’re modeling serializability, not strict serializability, so we allow histories like the one above in our specification.

(I’d say “good luck actually implementing a system that can read events from the future”, but in distributed databases when you’re receiving updates from different nodes at different times, some pretty weird stuff can happen…)

If you’d like to follow along as we go, my Serializable TLA+ model is in the github repo (source, pdf).

Externally visible variablesMy specification will generate operations (e.g., reads, writes, commits, aborts). The four externally visible variables in the specification are:

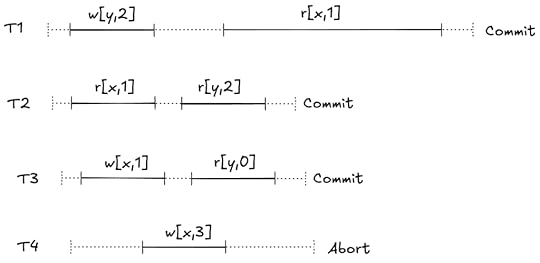

Variable nameDescriptionopthe operation (read, write, commit, abort), modeled as a single letter: {“r”, “w”, “c”, “a”} )argthe argument(s) to the operationrvalthe return value of the operationtrthe transaction executing the operationHere’s the serializable example from earlier:

The execution history shown above can be modeled as a TLA+ behavior like this:

Initial state of the specification

Initial state of the specificationWe need to specify the set of valid initial states. In the initial state of our spec, before any operations are issued, we determine:

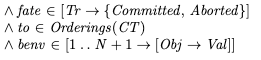

which transactions will commit and which will abortthe order in which the transactions will occurthe value of the environment for each committed transaction at the beginning and at the end of its lifetimeThis is determined by using three internal variables whose values are set in the initial state:

VariableDescriptionfatefunction which encodes which transactions commit and which aborttotransaction orderbenvthe value of the environments at the beginning/end of each transactionWe couldn’t actually implement a system that could predict in advance whether a transaction will commit or abort, but it’s perfectly fine to use these for defining our specification.

The values of these variables are specified like this:

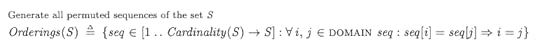

In our initial state, our specification chooses a fate, ordering, and begin/end environments for each transaction. Where Orderings is a helper operator:

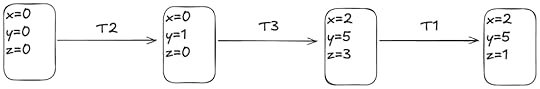

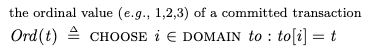

As an example, consider a behavior with three transactions fated to commit, where the fated transaction order is:

T2T3T1Furthermore, assume the following starting environments for each transaction:

T1: [x=2, y=5, z=3]

T2: [x=0, y=0, z=0]

T3: [x=0, y=1, z=0]

Finally, assume that the final environment state (once T1 completes) is [x=2,y=5,z=1].

We can visually depict the committed transactions like like this:

Reads and writes

Reads and writesYou can imagine each transaction running in parallel. As long as each transaction’s behavior is consistent with its initial environment, and it ends up with its final environment the resulting behavior will be serializable. Here’s an example.

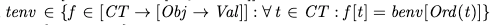

Each transaction has a local environment, tenv. If the transaction is fated to commit, its tenv is initialized to its benv at the beginning:

where:

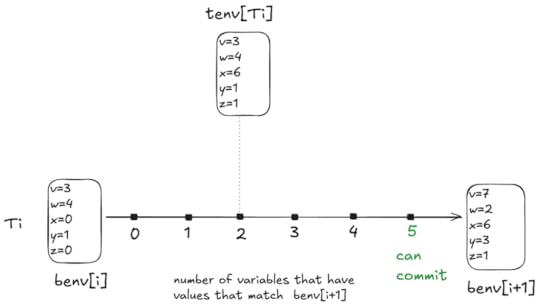

Here’s an example that shows how tenv for transaction T3 varies over time:

benv is fixed, but tenv for each transaction varies over time based on the writes

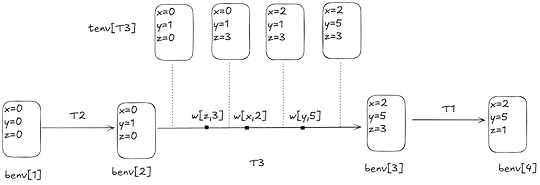

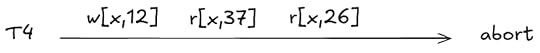

benv is fixed, but tenv for each transaction varies over time based on the writesIf the transaction is fated to abort, then we don’t track its environment in tenv, since any read or write is valid.

A valid behavior, as the definition of serializability places no constraints on the reads of an aborted transactionActions permitted by the specification

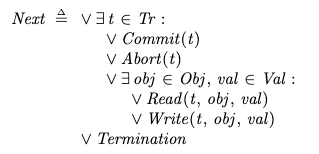

A valid behavior, as the definition of serializability places no constraints on the reads of an aborted transactionActions permitted by the specificationThe specification permits the following actions:

commit transactionabort transactionread a valuewrite a valueI’m not modeling the start of a transaction, because it’s not relevant to the definition of serializability. We just assume that all of the transactions have already started.

In TLA+, we specify it like this:

Note that there are no restrictions here on the order in which operations happen. Even if the transaction order is [T2, T3, T1], that doesn’t require that the operations from T2 have to be issued before the other two transactions.

Rather, the only constraints for each transaction that will commit is that:

Its reads must be consistent with its initial environment, as specified by benv.Its local environment must match the benv of the next transaction in the order when it finally commits.We enforce (1) in our specification by using a transaction-level environment, tenv, for the reads. This environment gets initialized to benv for each transaction, and is updated if the transaction does any writes. This enables each transaction to see its own writes.

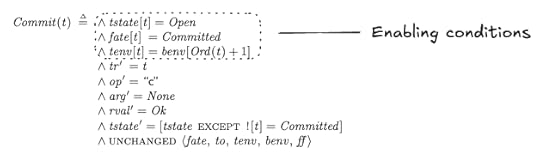

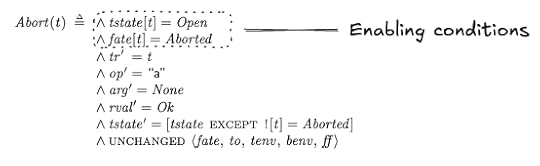

We enforce (2) by setting a precondition on the Commit action that it can only fire when tenv for that transaction is equal to benv of the next transaction:

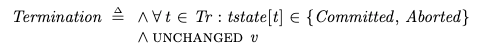

Termination

TerminationIf all of the transactions have committed or aborted, then the behavior is complete, which is modeled by the Termination sub-action, which just keeps firing and doesn’t change any of the variables:

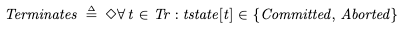

Liveness

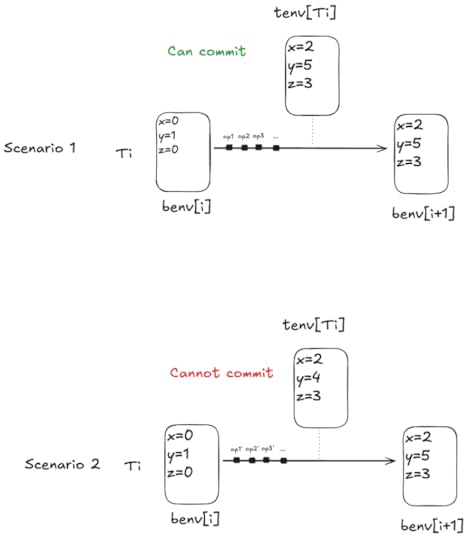

LivenessIn our specification, we want to ensure that every behavior eventually satisfies the Termination action. This means that all transactions either eventually commit or abort in every valid behavior of the spec. In TLA+, we can describe this desired property like this:

The diamond is a temporal operator that means “eventually”.

To achieve this property, we need to specify a liveness condition in our specification. This is a condition of the type “something we want to happen eventually happens”.

We don’t want our transactions to stay open forever.

For transactions that are fated to abort, they must eventually abortFor transactions that are fated to commit, they must eventually commitWe’re going to use weak and strong fairness to specify our liveness conditions; for more details on liveness and fairness, see my post a liveness example in TLA+.

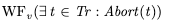

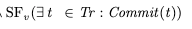

Liveness for abortsWe want to specify that everyone transaction that is fated to abort eventually aborts. To do this, we can use weak fairness.

This says that “the Abort action cannot be forever enabled without the Abort action happening”.

Here’s the Abort action.

The abort action is enabled for a transaction t if the transaction is in the open state, and its fate is Aborted.

Liveness for commitsThe liveness condition for commit is more subtle. A transaction can only commit if its local environment (tenv) matches the starting environment of the transaction that follows it in transaction order (benv).

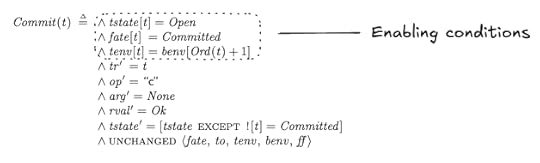

Consider two scenarios: one where tenv matches the next benv, and one where it doesn’t:

We want to use fairness to specify that every transaction fated to commit eventually reaches the state of scenario 1 above. Note that scenario 2 is a valid state in a behavior, it’s just not a state from which a commit can happen.

Consider the following diagram:

For every value of tenv[Ti], the number of variables that match the values in benv[i+1] is somewhere between 0 and 5. In the example above, there are two variables that match, x and z.

Note that the Commit action is always enabled when a transaction is open, so with every step of the specification, tenv can move left or right in the diagram above, with a min of 0 and a max of 5.

We need to specify “tenv always eventually moves to the right”. When tenv is at zero, we can use weak fairness to specify that it eventually moves from 0 to 1.

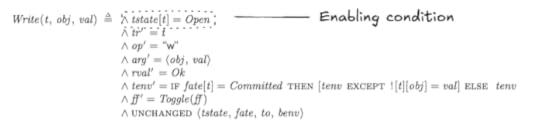

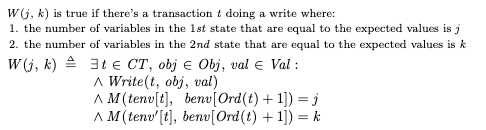

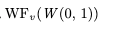

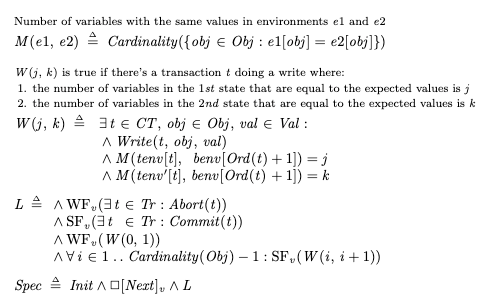

To specify this, I defined a function W(0, 1) which is true when tenv moves from 0 to 1:

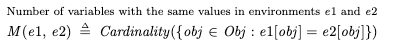

Where M(env1, env2) is a count of the number of variables that have the same value:

This means we can specify “tenv cannot forever stay at 0” using weak fairness, like this:

We also want to specify that tenv eventually moves from 1 matches to 2, and then from 2 to 3, and so on, all of the way from 4 to all 5. And then we also want to say that it eventually goes from all matches to commit.

We can’t use weak fairness for this, because if tenv is at 1, it can also change to 0. However, the weak fairness of W(0,1) ensures that it if it goes from 1 down to 0, it will always eventually go back to 1.

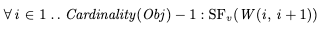

Instead, we need to use strong fairness, which says that “if the action is enabled infinitely often, then the action must be taken”. We can specify strong fairness for each of the steps like this:

Recall that Obj is the set of objects {x, y, z, …}, and Cardinality refres to the size of the set. We also need to specify strong fairness on the commit action, to ensure that we eventually commit if all variables matching is enabled infinitely often:

Now putting it all together, here’s one way to specify the liveness condition, which is conventionally called L.

Once again, the complete model is in the github repo (source, pdf).

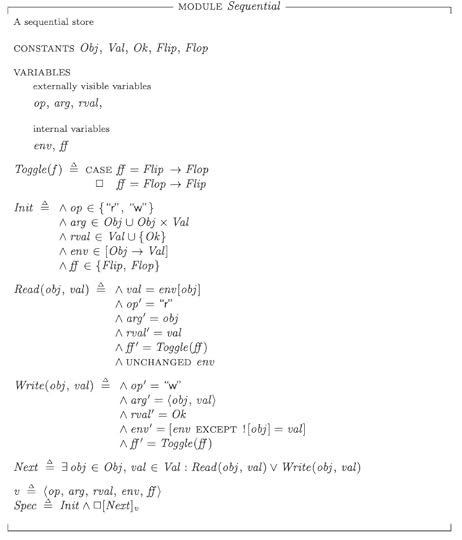

How do we know our spec is correct?We can validate our serializable specification by creating a refinement mapping to a sequential specification. Here’s a simple sequential specification for a key-value store, Sequential.tla:

I’m not going to get into the details of the refinement mapping in this post, but you can find it at in the SerializabilityRefinement model (source, pdf).

OK, but how do you know that this spec is correct?It’s turtles all of the way down! This is really the bottom in terms of refinement, I can’t think of an even simpler spec that we can use to validate this one.

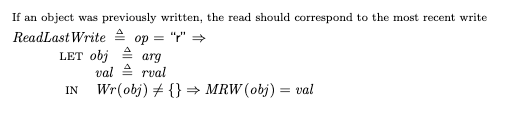

However, one thing we can do is specify invariants that we can use to validate the specification, either with the model checker or by proof.

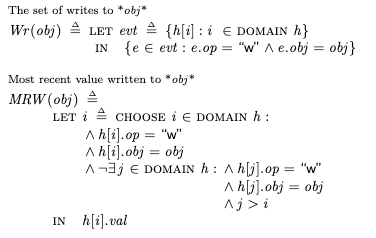

For example, here’s an invariant that checks whether each write has an associated read that happened before:

where:

But what happens if there’s no initial write? In that case, we don’t know what the read should be. But we do know that we don’t want to allow two successive reads to read different values, for example:

r[x,3], r[x,4]

So we can also specify this check as an invariant. I called that SuccessiveReads, you can find it in the MCSequential model (source, pdf).

The value of formalizing the specificationNow that we have a specification for Serializability, we can use it to check if a potential concurrency control implementation actually satisfies this specification.

That was my original plan for this blog post, but it got so long that I’m going to save that for a future blog post. In that future post, I’m going to model multi-version concurrency control (MVCC) and show how it fails to satisfy our serializability spec by having the model checker find a counterexample.

However, in my opinion, the advantage of formalizing a specification is that it forces you to think deeply about what it is that you’re specifying. Finding counter-examples with the model checker is neat, but the real value is the deeper understanding you’ll get.