Reading the Generalized Isolation Level Definitions paper with Alloy

My last few blog posts have been about how I used TLA+ to gain a better understanding of database transaction consistency models. This post will be in the same spirit, but I’ll be using a different modeling tool: Alloy.

Like TLA+, Alloy is a modeling language based on first-order logic. However, Alloy’s syntax is quite different: defining entities in Alloy feels like defining classes in an object-oriented language, including the ability to define subtypes. It has first class support for relations, which makes it very easy to do database-style joins. It also has a very nifty visualization tool, which can help when incrementally defining a model.

I’m going to demonstrate here how to use it to model and visualize database transaction execution histories, based on the paper Generalized Isolation Level Definitions by Atul Adya, Barbara Liskov and Patrick O’Neil. This is a shorter version of Adya’s dissertation work, which is referenced frequently on the Jepsen consistency models pages.

There’s too much detail in the models to cover in this blog post, so I’m just going to touch on some topics. If you’re interested in more details, all of my models are in my https://github.com/lorin/transactions-alloy repository.

Modeling entities in Alloy

Let’s start with a model with the following entiteis:

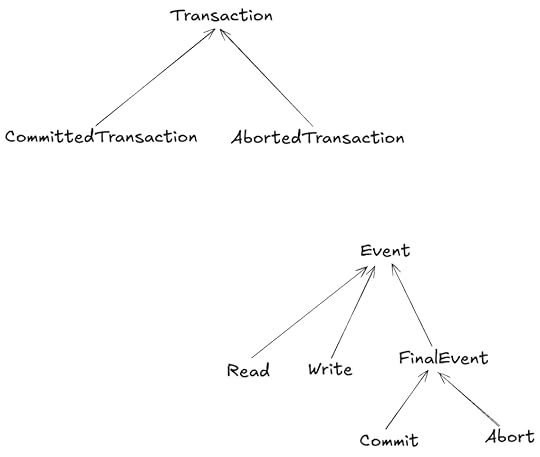

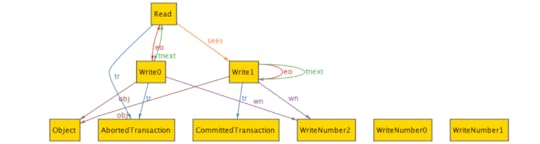

objectstransactions (which can commit or abort)events (read, write, commit, abort)The diagram below shows some of the different entities in our Alloy model of the paper.

You can think of the above like a class diagram, with the arrows indicating parent classes.

Objects and transactionsObjects and transactions are very simple in our model.

sig Object {}abstract sig Transaction {}sig AbortedTransaction, CommittedTransaction extends Transaction {}The word sig is a keyword in Alloy that means signature. Above I’ve defined transactions as abstract, which means that they can only be concretely instantiated by subtypes.

I have two subtypes, one for aborted transactions, one for committed transactions.

Events

Here are the signatures for the different events:

abstract sig Event { tr: Transaction, eo: set Event, // event order (partial ordering of events) tnext: lone Event // next event in the transaction}// Last event in a transactionabstract sig FinalEvent extends Event {}sig Commit extends FinalEvent {}sig Abort extends FinalEvent {}sig Write extends Event { obj: Object, wn : WriteNumber}sig Read extends Event { sees: Write // operation that did the write}The Event signature has three fields:

tr – the transaction associated with the eventeo – an event ordering relationship on eventstnext – the next event in the transactionReads and writes each have additional fielsd.

ReadsA read has one custom field, sees. In our model, a read operation “sees” a specific write operation. We can follow that relationship to identify the object and the value being written.

Writes and write numbers

The Write event signature has two additional fields:

obj – the object being writtenwn – the write numberFollowing Adya, we model the value of a write by a (transaction, write number) pair. Every time we write an object, we increment the write number. For example, if there are multiple writes to object X, the first write has write number 1, the second has write number 2, and so on.

We could model WriteNumber entities as numbers, but we don’t need full-fledged numbers for this behavior. We just need an entity that has an order defined (e.g., it has to have a “first” element, and each element has to have a “next” element). We can use the ordering module to specify an ordering on WriteNumber:

open util/ordering[WriteNumber] as wosig WriteNumber {}VisualizingWe can use the Alloy visualizer to generate a visualization of our model. To do that, we just need to use the run command. Here’s the simplest way to invoke that command:

run {}Here’s what the generated output looks like:

Visualization of a history with the default theme

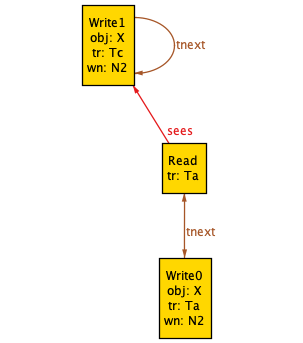

Visualization of a history with the default themeYipe, that’s messy! We can clean this up a lot by configuring the theme in the visualizer. Here’s the same graph, with different theme settings. I renamed several things (e.g., “Ta” instead of “AbortedTransaction”), I had some relationships I didn’t care about (eo), and I showed some relationships as attributes instead of arcs (e.g., tr).

Visualization after customizing the theme

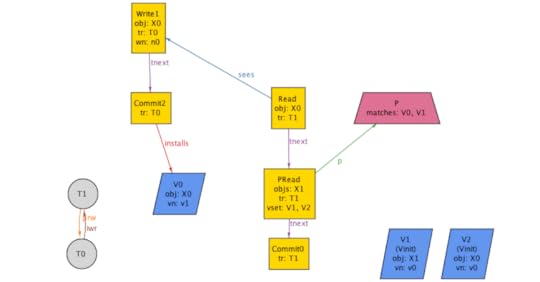

Visualization after customizing the themeThe diagram above shows two transactions (Ta, Tc). Transaction Ta has a read operation (Read) and a write operation (Write0). Transaction Tc has a write operation. (Write1).

Constraining the model with factsThe history above doesn’t make much sense:

tnext is supposed to represent “next event in the transaction”, but in each transaction, tnext has loops in itTa belongs to the set of aborted transactions, but it doesn’t have an abort eventTc belongs to the set of committed transactions, but it doesn’t have a commit eventWe need to add constraints to our model so that it doesn’t generate nonsensical histories. We do this in Alloy by adding facts.

For example, here are some facts:

// helper function that returns set of events associated with a transactionfun events[t : Transaction] : set Event { tr.t}fact "all transactions contain exactly one final event" { all t : Transaction | one events[t] & FinalEvent}fact "nothing comes after a final event" { no FinalEvent.tnext}fact "committed transactions contain a commit" { all t : CommittedTransaction | some Commit & events[t]}fact "aborted transactions contain an abort" { all t : AbortedTransaction | some Abort & events[t]}Now our committed transactions will always have a commit! However, the facts above aren’t sufficient, as this visualization shows:

I won’t repeat all of the facts here, you can see them in the transactions.als file.

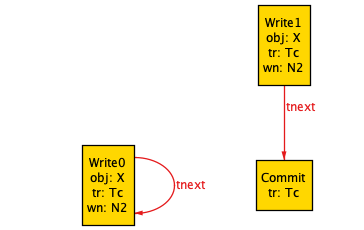

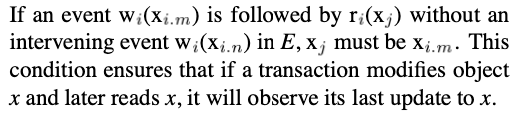

Here’s one last example of a fact, encoded from the Adya paper:

The corresponding fact in my model is:

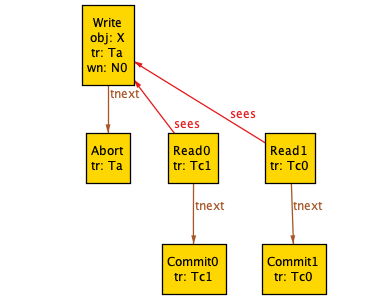

/** * If an event wi (xi:m) is followed by ri (xj) without an intervening event wi (xi:n) in E, xj must be xi:m */fact "transaction must read its own writes" { all T : Transaction, w : T.events & Write, r : T.events & Read | ({ w.obj = r.sees.obj w->r in eo no v : T.events & Write | v.obj = r.sees.obj and (w->v + v->r) in eo } => r.sees = w)}With the facts specified, our generated histories no longer look absurd. Here’s an example:

Mind you, this still looks like an incorrect history: we have two transactions (Tc1, Tc0) that commit after reading a write from an aborted transaction (Ta).

Installed versions

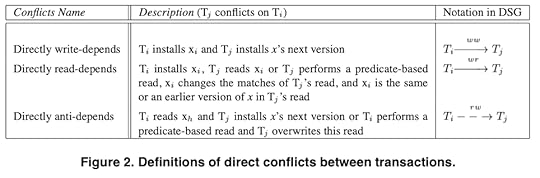

The paper introduces the concept of a version of an object. A version is installed by a committed transaction that contains a write.

I modeled versions like this.

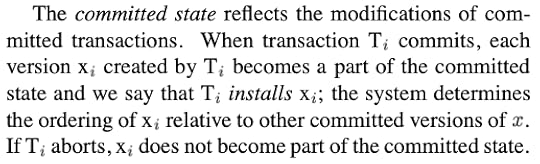

open util/ordering[VersionNumber] as vosig VersionNumber {}// installed (committed) versionssig Version { obj: Object, tr: one CommittedTransaction, vn: VersionNumber}DependenciesOnce we have versions defined, we can model the dependencies that Adya defines in his paper. For example, here’s how I defined the directly write-depends relationship, which Adya calls ww in his diagrams.

fun ww[] : CommittedTransaction -> CommittedTransaction { { disj Ti, Tj : CommittedTransaction | some v1 : installs[Ti], v2 : installs[Tj] | { same_object[v1, v2] v1.tr = Ti v2.tr = Tj next_version[v1] = v2 } }}Visualizing counterexamples

fun ww[] : CommittedTransaction -> CommittedTransaction { { disj Ti, Tj : CommittedTransaction | some v1 : installs[Ti], v2 : installs[Tj] | { same_object[v1, v2] v1.tr = Ti v2.tr = Tj next_version[v1] = v2 } }}Visualizing counterexamplesHere’s a final visualizing example of visualizations. The paper A Critique of ANSI SQL Isolation Levels by Berenson et al. provides some formal definition of different interpretations of the ANSI SQL specification. One of them they call “anomaly serializable (strict interpretation)”.

We can build a model this interpretation in Alloy. Here’s part of it just to give you a sense of what it looks like, see my bbg.als file for the complete model:

pred AnomalySerializableStrict { not A1 not A2 not A3}/** * A1: w1[x]...r2[x]...(a1 and c2 in any order) */pred A1 { some T1 : AbortedTransaction, T2 : CommittedTransaction, w1: Write & events[T1], r2 : Read & events[T2], a1 : Abort & events[T1] | { w1->r2 in teo r2.sees = w1 // r2 has to happen before T1 aborts r2->a1 in teo }}...And then we can ask Alloy to check whether AnomalySerializableStrict implies Adya’s definition of serializability (which he calls isolation level PL-3).

Here’s how I asked Alloy to check this:

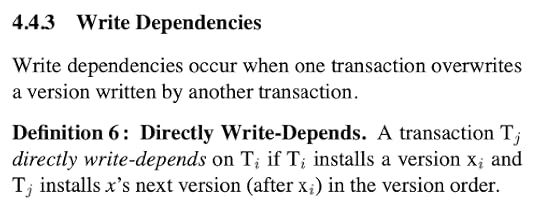

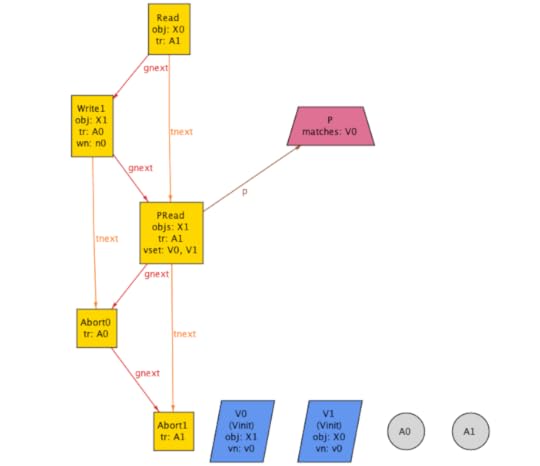

assert anomaly_serializable_strict_implies_PL3 { always_read_most_recent_write => (b/AnomalySerializableStrict => PL3)}check anomaly_serializable_strict_implies_PL3for 8 but exactly 3 Transaction, exactly 2 Object, exactly 1 PredicateRead, exactly 1 PredicateAlloy tells me that the assertion is invalid, and shows the following counterexample:

This shows a history that satisfies the anomaly serializable (strict) specificaiton, but not Adya’s PL-3. Note that the Alloy visualizer has generated a direct serialization graph (DSG) in the bottom left-hand corner, which contains a cycle.

Predicate readsThis counterexample involves predicate reads, which I hadn’t shown modeled before, but they look like this:

// transactions.alsabstract sig Predicate {}abstract sig PredicateRead extends Event { p : Predicate, objs : set Object}// adya.alssig VsetPredicateRead extends PredicateRead { vset : set Version}sig VsetPredicate extends Predicate { matches : set Version}A predicate read is a read that returns a set of objects.

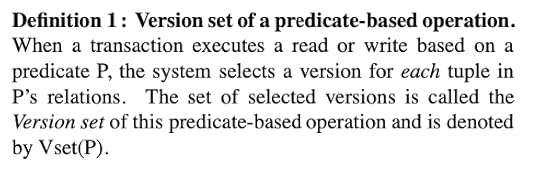

In Adya’s model, a predicate read takes as input a version set (a version for each object) and then determines which objects should be included in the read based on whether or not the versions match the predicate:

fact "objects in predicate read are the objects that match in the version set" { all pread : VsetPredicateRead | pread.objs = (pread.vset & pread.p.matches).obj}One more counterexampleWe can also use Alloy to show us when a transaction would be permitted by Adya’s PL-3, but forbidden by the broad interpretation of anomaly serializability:

check PL3_implies_anomaly_serializable_broadfor 8 but exactly 3 Transaction, exactly 2 Object, exactly 1 PredicateRead, exactly 1 Predicateassert PL3_implies_anomaly_serializable_broad { always_read_most_recent_write => (PL3 => b/AnomalySerializableBroad)}

The example above shows the “gnext” relation, which yields a total order across events.

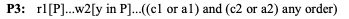

The resulting counterexample is two aborted transactions! Those are trivially serializable, but it is ruled out by the broad definition, specifically, P3:

Playing with Alloy

Playing with AlloyI encourage you to try Alloy out. There’s a great that will let you execute your Alloy models from VS Code, that’s what I’ve been using. It’s very easy to get started with Alloy, because you can get it to generate visualizations for you out of the simplest models.

For more resources, Hillel Wayne has written a set of Alloy docs that I often turn to. There’s even an entire book on Alloy written by its creator. (Confusingly, though, the book does not have the word Alloy in the name).