Multi-version concurrency control in TLA+

In a previous blog post, I talked about how we can use TLA+ to specify the serializability isolation level. In this post, we’ll see how we can use TLA+ to describe multi-version concurrency control (MVCC), which is a strategy for implementing transaction isolation. Postgres and MySQL both use MVCC to implement their repeatable read isolation levels, as well as a host of other databases.

MVCC is described as an optimistic strategy because it doesn’t require the use of locks, which reduces overhead. However, as we’ll see, MVCC implementations aren’t capable of achieving serializability.

All my specifications are in https://github.com/lorin/snapshot-isolation-tla.

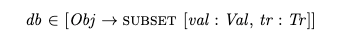

Modeling MVCC in TLA+Externally visible variablesWe use a similar scheme as we did previously for modeling the externally visible variables. The only difference now is that we are also going to model the “start transaction” operation:

Variable nameDescriptionopthe operation (start transaction, read, write, commit, abort), modeled as a single letter: {“s”, “r”, “w”, “c”, “a”} )argthe argument(s) to the operationrvalthe return value of the operationtrthe transaction executing the operationThe constant setsThere are three constant sets in our model:

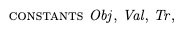

Obj – the set of objects (x, y,…)Val – the set of values that the objects can take on (e.g., 0,1,2,…)Tr – the set of transactions (T0, T1, T2, …)

Obj – the set of objects (x, y,…)Val – the set of values that the objects can take on (e.g., 0,1,2,…)Tr – the set of transactions (T0, T1, T2, …)

I associate the initial state of the database with a previously committed transaction T0 so that I don’t have to treat the initial values of the database as a special case.

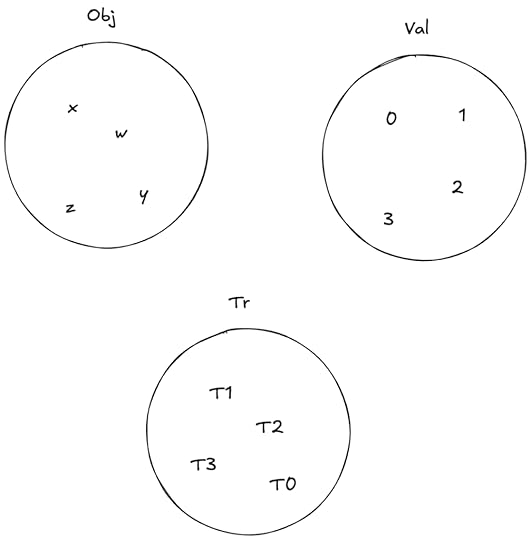

The multiversion databaseIn MVCC, there can be multiple versions of each object, meaning that it stores multiple values associated with each object. Each of these versions is also has information on which transaction created it.

I modeled the database in TLA+ as a variable named db, here is an invariant that shows the values that db can take on:

It’s a function that maps objects to a set of version records. Each version record is associated with a value and a transaction. Here’s an example of a valid value for db:

Example db where Obj={x,y}Playing the home game with Postgres

Example db where Obj={x,y}Playing the home game with PostgresPostgres’s behavior when you specify repeatable read isolation level appears to be consistent with the MVCC TLA+ model I wrote so I’ll use it to illustrate some how these implementation details play out. As Peter Alvaro and Kyle Kingsbury note in their Jepsen analysis of MySQL 8.0.34, Postgres’s repeatable read isolation level actually implements snapshot isolation, while MySQL’s repeatable read isolation level actually implements …. um … well, I suggest you read the analysis.

I created a Postgres database named tla. Because Postgres defaults to read committed, I changed the default to repeatable read on my database so that it would behave more like my model.

ALTER DATABASE tla SET default_transaction_isolation TO 'repeatable read';create table obj ( k char(1) primary key, v int);insert into obj (k,v) values ('x', 0), ('y', 0);Starting a transaction: id and visibilityIn MVCC, each transaction gets assigned a unique id, and ids increase monotonically.

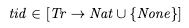

Transaction id: tidI modeled this with a function tid that maps transactions to natural numbers. I use a special value called None for the transaction id for transactions who have not started yet.

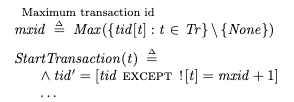

When a transaction starts, I assign it an id by finding the largest transaction id assigned so far (mxid), and then adding 1. This isn’t efficient, but for a TLA+ spec it works quite nicely:

In Postgres, you can get the ID of the current transaction by using the pg_current_xact_id function. For examplle:

$ psql tlapsql (17.0 (Homebrew))Type "help" for help.tla=# begin;BEGINtla=*# select pg_current_xact_id(); pg_current_xact_id-------------------- 822(1 row)Visible transactions: visWe want each transaction to behave as if it is acting against a snapshot of the database from when the transaction started.

We can implement this in MVCC by identifying the set of transactions that have previously committed, and ensuring that our queries only read from writes done by these transactions.

I modeled this with a function called vis which maps each transaction to a set of other transactions. We also want our own writes to be visible, so we include the transaction being started in the set of visible transactions:

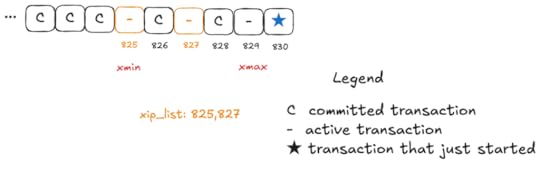

For each snapshot, Postgres tracks the set of committed transactions using three variables:

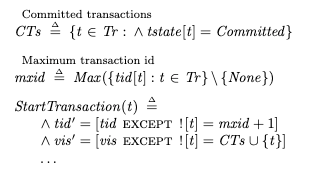

xmin – the lowest transaction id associated with an active transactionxmax – (the highest transaction id associated with a committed transaction) + 1xip_list – the list of active transactions whose ids are less than xmaxIn Postgres, you can use the pg_current_snapshot function, which returns xmin:xmax:xip_list:

tla=# SELECT pg_current_snapshot(); pg_current_snapshot--------------------- 825:829:825,827Here’s a visualization of this scenario:

These three variables are sufficient to determine whether a particular version is visible. For more on the output of pg_current_snapshot, check out the Postgres operations cheat sheet wiki.

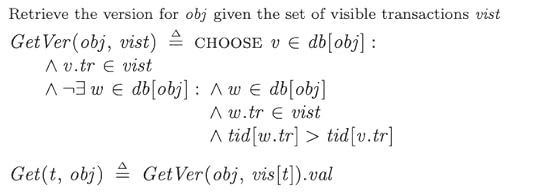

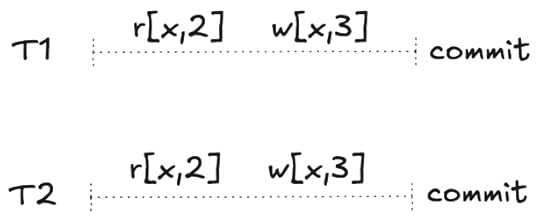

Performing readsA transaction does a read using the Get(t, obj) operator. This operator retrieves the visible version with the largest transaction id:

Performing writes

Performing writesWrites are straightforward, they simply add new versions to db. However, if a transaction did a previous write, that previous write has to be removed. Here’s part of the action that writes obj with value val for transaction t:

The lost update problem and how MVCC prevents it

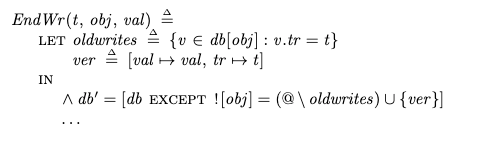

The lost update problem and how MVCC prevents itConsider the following pair of transactions. They each write the same value and then commit.

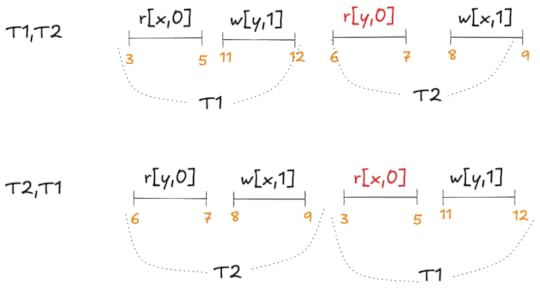

A serializable execution history

A serializable execution historyThis is a serializable history. It actually has two possible serializations: T1,T2 or T2,T1

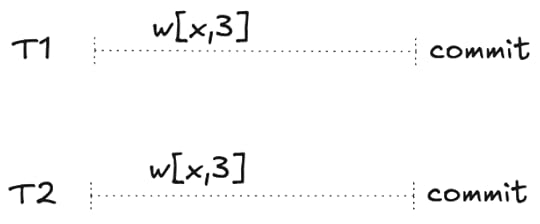

Now let’s consider another history where each transaction does a read first.

A non-serializable execution history

A non-serializable execution historyThis execution history isn’t serializable anymore. If you try to sequence these, the second read will read 2 where it should read 3 due to the previous write.

Serializability is violated: the read returns 2 instead of 3

Serializability is violated: the read returns 2 instead of 3This is referred to as the lost update problem.

Here’s a concrete example of the lost update problem. Imagine you’re using a record as a counter: you read the value, increment the result by one, and then write it back.

SELECT v FROM obj WHERE k='x';-- returns 3UPDATE obj set v=4 WHERE k='x';Now imagine these two transactions run concurrently. If neither sees the other’s write, then one of these increments will be lost: you will have missed a count!

MVCC can guard against this by preventing two concurrent transactions from writing to the same object. If transaction T1 has written to a record in an active transaction, and T2 tries to write to the same record, then the database will block T2 until T1 either commits or aborts. If the first transaction commits, the database will abort the second transaction.

You can confirm this behavior in Postgres, where you’ll get an error if you try to write to a record that has previously been written to by a transaction that was active and then committed:

$ psql tlapsql (17.0 (Homebrew))Type "help" for help.tla=# begin;BEGINtla=*# update obj set v=1 where k='x';ERROR: could not serialize access due to concurrent updatetla=!#Interestingly, MySQL’s MVCC implementation does not prevent lost updates(!!!). You can confirm this yourself.

Implementing this in our modelIn our model, a write is implemented by two actions:

BeginWr(t, obj, val) – the initial write requestEndWr(t, obj, val) – the successful completion of the writeWe do not allow the EndWr action to fire if:

There is an active transaction that has written to the same object (here we want to wait until the other transaction commits or aborts)There is a commit to the same object by a concurrent transaction (here we want to abort)

We also have an action named AbortWr that aborts if a write conflict occurs.

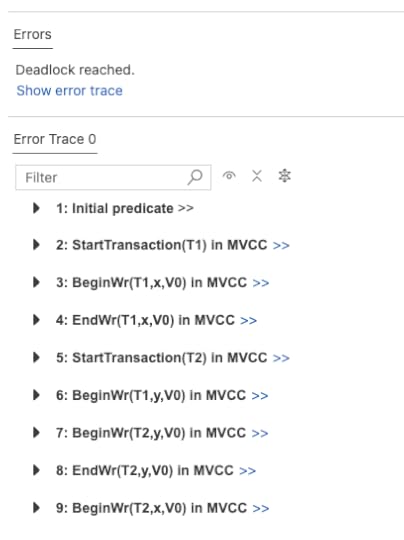

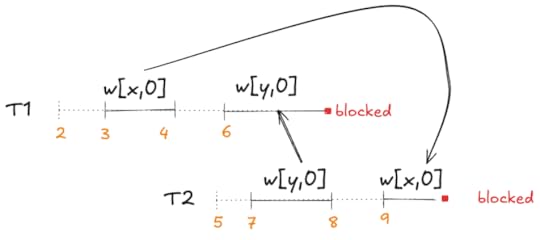

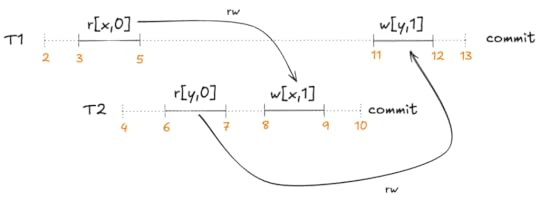

Deadlock!There’s one problem with the approach above where we block on a concurrent write: the risk of deadlock. Here’s what happens when we run our model with the TLC model checker:

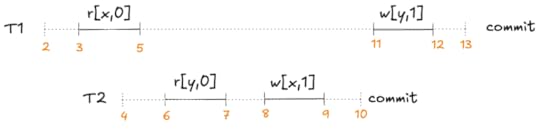

Here’s a diagram of this execution history:

The problem is that T1 wrote x first and T2 wrote y first, and then T1 got blocked trying to write y and T2 got blocked trying to write x. (Note that even though T1 started to write y before T2, T2 completed the write first).

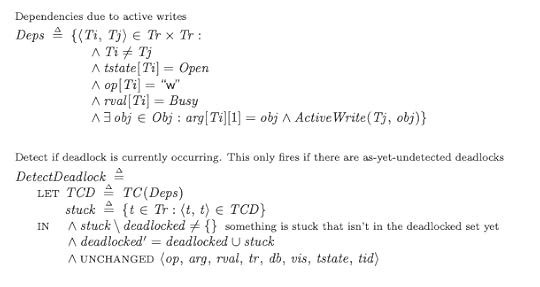

We can deal with this problem by detecting deadlocks and aborting the affected transactions when they happen. We can detect deadlock by creating a graph of dependencies between transactions (just like in the diagram above!) and then look for cycles:

Here TC stands for transitive closure, which is a useful relation when you want to find cycles. I used one of the transitive closure implementations in the TLA+ examples repo.

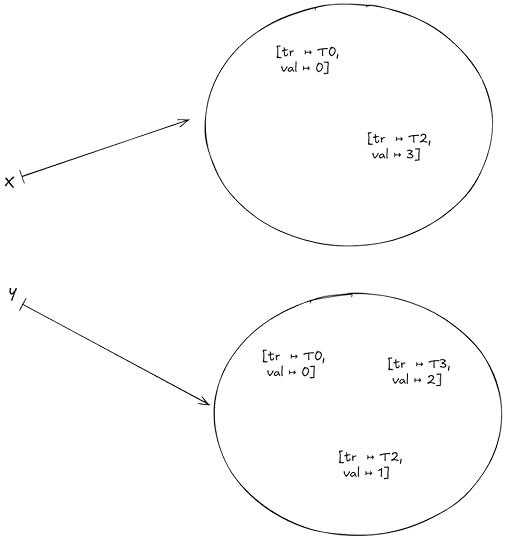

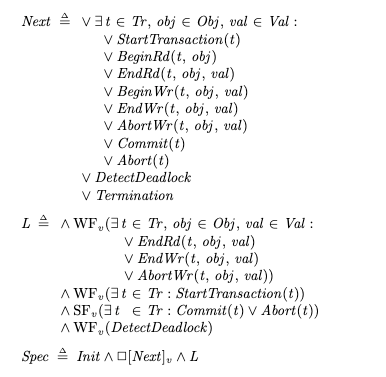

Top-level of the specificationHere’s a top-level view of the specification, you can find the full MVCC specification in the repo (source, pdf):

Note how reads and writes have begin/end pairs. In addition, a BeginWr can end in an AbortWr if there’s a conflict or deadlock as discussed earlier.

For liveness, we can use weak fairness to ensure that read/write operations complete, transactions start, and that deadlock is detected. But for commit and abort, we need strong fairness, because we can have infinite sequences of BeginRd/EndRd pairs or BeginWr/EndWr pairs and Commit and Abort are not enabled in the middle of reads or writes.

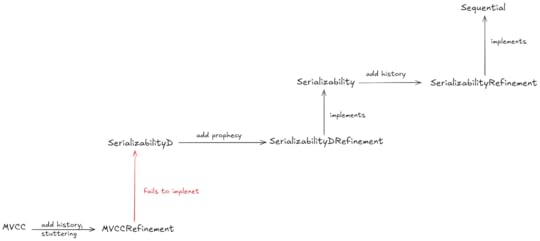

My MVCC spec isn’t serializableNow that we have an MVCC spec, we can check to see if implements our Serializable spec. In order to do that check, we’ll need to do a refinement mapping from MVCC to Serializable.

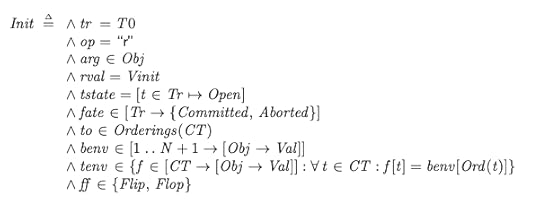

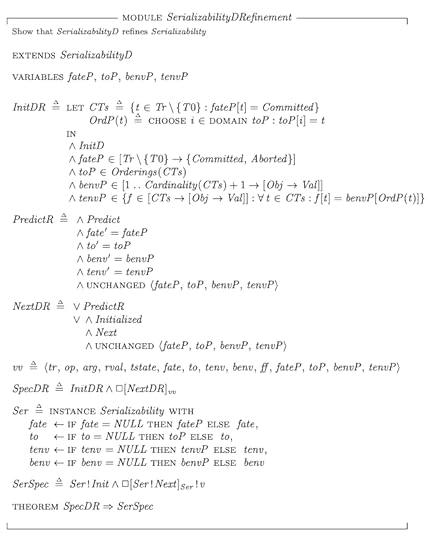

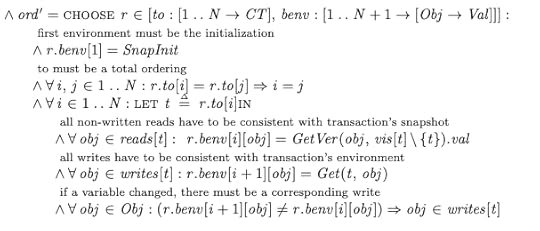

One challenge is that the initial state of the Serializable specification establishes the fate of all of the transactions and what their environments are going to be in the future:

The Init state for the Serializable specAdding a delay to the Serializability spec

The Init state for the Serializable specAdding a delay to the Serializability specIn our MVCC spec, we don’t know in advance if a transaction will commit or abort. We could use prophecy variables in our refinement mapping to predict these values, but I didn’t want to do that.

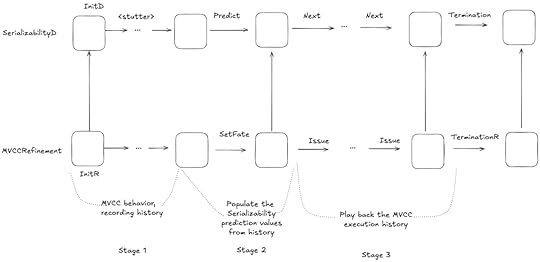

What I did instead was to create a new specification, SerializabilityD (source, pdf), that delays these predictions until the second step of the behavior:

I could then do a refinement mapping MVCC ⇒ SerializabilityD without having to use prophecy variables.

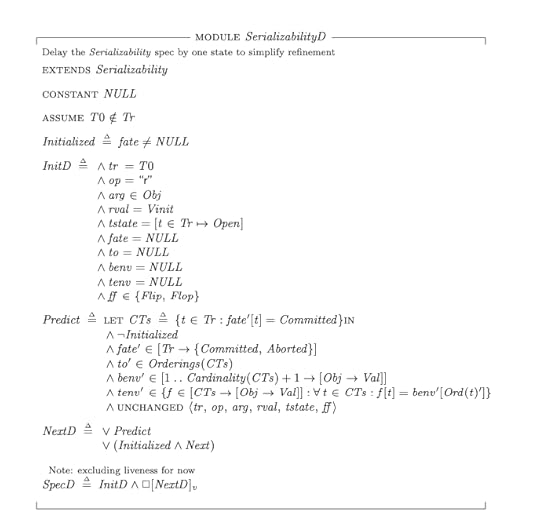

Verifying that SerializabilityD actually implements SerializabilityNote that it’s straightforward to do the SerializabilityD ⇒ Serializability refinement mapping with prophecy variables. You can find it in SerializabilityDRefinement (source, pdf):

The MVCC ⇒ SerializabilityD mapping

The MVCC ⇒ SerializabilityD mappingThe MVCC ⇒ SerializabilityD refinement mapping is in the MVCCRefinement spec (source, pdf).

The general strategy here is:

Execute MVCC until all of the transactions complete, keeping an execution history. Use the results of the MVCC execution to populate the SerializabilityD variablesStep through the recorded MVCC execution history one operation at a timeThe tricky part is step 2, because we need to find a serialization.

Attempting to find a serializationOnce we have an MVCC execution history, we can try to find a serialization. Here’s the relevant part of the SetFate action that attempts to select the to and benv variables from Serializability that will satisfy serializability:

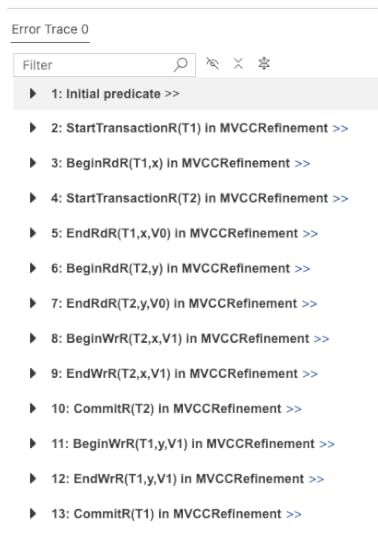

Checking the refinement mapping

Checking the refinement mappingThe problem with the refinement mapping is that we cannot always find a serialization. If we try to model check the refinement mapping, TLC will error because it is trying to CHOOSE from an empty set.

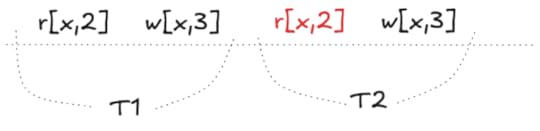

This MVCC execution history is a classic example of what’s called write skew. Here’s a visual depiction of this behavior:

A non-serializable execution history that is permitted by MVCC

A non-serializable execution history that is permitted by MVCCNeither T1,T2 nor T2,t1 is a valid serialization of this execution history:

If we sequence T1 first, then the r[y,0] read violates the serialization. If we sequence T2 first, then the r[x,0] read violates it.

If we sequence T1 first, then the r[y,0] read violates the serialization. If we sequence T2 first, then the r[x,0] read violates it.These constraints are what Adya calls anti-dependencies. He uses the abbreviation rw for short, because the dependency is created by a write from one transaction clobbering a read done by the other transaction, so the write has to be sequenced after the read.

Because snapshot isolation does not enforce anti-dependencies, it generates histories that are not serializable, which means that MVCC does not implement the Serializability spec.

CodaI found this exercise very useful in learning more about how MVCC works. I had a hard time finding a good source to explain the concepts in enough detail for me to implement it, without having to read through actual implementations like Postgres, which has way too much detail. One useful resource I found was these slides on MVCC by Joy Arulraj at Georgia Tech. But even here, they didn’t have quite enough detail, and my model isn’t quite identical. But it was enough to help me get started.

I also enjoyed using refinement mapping to do validation. In the end, these were the refinement mappings I defined:

I’d encourage you to try out TLA+, but it really helps if you have some explicit system in mind you want to model. I’ve found it very useful for deepening my understanding of consistency models.