Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 97

July 2, 2016

Weekend Reading: Clash or Credit

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

Clash Rules Everything Around Me, Tony Tulathimutte, Real Life

There’s no question that the politics of many mobile games are a cynic’s. Money can be exchanged for nearly every minutia in their game world, making actually playing a null strategy. But as Tony Tulathimutte writes, the more interesting thing about games like Clash of Clans (2012) isn’t just its drain on player’s wallets, but how it values their time.

The Reluctant Memoirist, Suki Kim, The New Republic

Suki Kim risked her world for over a decade, going undercover as a teacher in North Korea to research the country unknown to the rest of the world, and gaining insight to some of the country’s top brass through their kids. When she returned, she encountered a whole new kind of adversary: the publishers who couldn’t envision selling an Asian woman as an investigative reporter, hoping to instead transform Kim into an Elizabeth Gilbert type of lifestyle writer.

Photo by Richard Lam, via The Globe and Mail

Chop Suey Nation, Ann Hui, The Globe and Mail

From the densest parts of British Columbia to the sparsest Southern Ontario towns, there always seems to be Chinese food in Canada. In an extensive piece, Ann Hui road trips the country to discover the hidden map of Chinese Canadians, the families and people behind the restaurants that let you build ziggurats out of thickly-caked fried chicken balls.

Angola’s Greatest Escape, Stephie Grob Plante, Racked

Louisiana’s Angola prison at times sounds like the dystopia from Death Race (the 2008 remake, not the Roger Corman original with Stallone), certainly whenever the penitentiary throws one of their surreal rodeos. Stephie Grob Plante, however, believes the rodeo overshadows a more interesting event: Angola’s craft fair, a rare opportunity for its inmates to interact with the public in a normal way.

///

Header image: Entry of Henry IV into Paris, by Rubens, 1628–30

The post Weekend Reading: Clash or Credit appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 1, 2016

Two game artists share the Japanese yōkai that inspire them

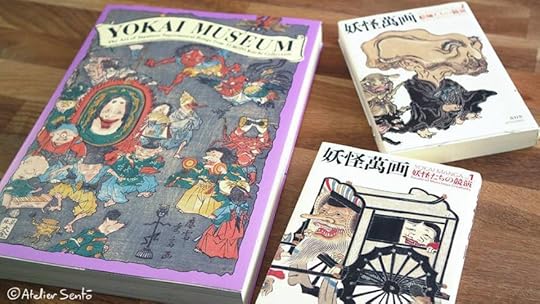

After living in Japan’s seaside city of Niigata for a year, French artists Cécile Brun and Olivier Pichard learned, among many other things, an appreciation for the island nation’s mythology and art. They’ve told us about their visits to Buddhist spiritual sites on Japanese mountains, and as we’ve written before, the pair have a particular fondness for Japanese photographer Kotori Kawashima and his photobook Mirai-chan, which depicts a young girl living in Niigata’s Sato Island.

“What interests us here is this juxtaposition of a very young girl from today and an ancient mysterious world,” they said. Since returning home to France, it has served as inspiration for their works at their comics and games studio Atelier Sentō, much of which also deals with Japanese youth and their experiences with the spiritual history of their home country. Take The Coral Cave, their upcoming watercolor adventure game about a young girl traveling around her seaside hometown and meeting the spirits that live there.

It reminds me of how I spent much of my own youth enjoying my favorite show at the time—Inuyasha. It’s a much-maligned story about a modern girl in ancient Japan with her “demon” dog. My only regret is watching the English dub, which called all the supernatural characters “demons,” when in fact the Japanese original dug deeper into the country’s culture by differentiating these creatures with terms such as yōkai.

In Japanese mythology, yōkai is a general catch-all term for most kinds of spirits or supernatural beings. It excludes kami (literally translated to god), which are typically spirits belonging to natural forces, revered ancestors, or even the creators of the world themselves. However, kami does not include famous creatures like kappa (turtle monsters that inspired the Koopa Troopas in Super Mario Bros) or tengu. Though often translated in the West as demons, as was the case in Inuyasha, they are actually more like classic European fairies, in that they run the range from malicious to mischievous to even beneficial, and come in a variety of shapes and sizes. They’re also more like animals than agents of hell. The point being that it’s misleading to call all of Japan’s supernatural creatures “demon,” as in the West it refers mostly to evil monsters out to steal souls. Yōkai, as I have seen, are closer to acting more like people than anything else, giving them a dynamism that I wasn’t getting from the usual Western stories.

more like caricatures of humans than as supernatural beings

Which brings us back to Atelier Sentō and The Coral Cave. Set in Okinawa, the game has the girl traveling around the industrial and natural hotspots of her own time, and being surprised by the myths and history she uncovers there. For example, in the trailer for the game, she meets a woman in a white kimono who calls herself the guardian of the Coral Cave and who is likely either a kami or a yōkai. The guardian is the most detailed spirit we’ve seen yet in the game’s already released screenshots and footage, but thanks to a recent post on Atelier Sentō’s site, it seems they’re hard at work making more.

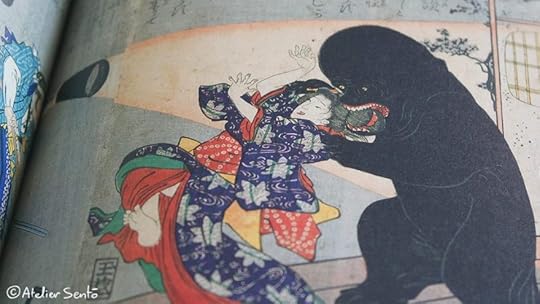

“Yôkai!!!” they write. “They are both funny and frightening.” What follows is a collection of photos from the reference material the studio is using to build the game, showing off the various yōkai they are looking towards as inspiration for creating The Coral Cave‘s own spirits. Funny and frightening is a fitting description. Again, these are not demons (at least in the Western sense), and while some may be monstrous, they all carry a good deal of individualism and personality.

Take the old man with a giant face driving a cart with another giant-faced person in the back. They almost come across more like caricatures of humans than as supernatural beings, and I’d say they fall more in the funny camp than the frightening one.

Then there’s the picture of a big jet black bear-thing trying very hard to eat a woman’s hair. This one is a bit more frightening, and certainly more malicious, but oh bother if he just does not look kind of like Pooh Bear trying to steal his honey from bees.

There’s a woman with a severed head, and another with a sullen face that is more sympathetic than scary. I think my favorite, though, might be the shirtless pig guy running around carrying a flag and looking at the reader with wide, guilty eyes as if he’s been caught stealing from the cookie jar.

If the yōkai in The Coral Cave are anything like this, then we are in good hands. If there’s anything I can give Inuyasha credit for looking back on it now, it would be for creating a believable world populated by fantastic beings, each with their own striking visual designs, involved backstories, personal goals, and methods for achieving them. These weren’t just monsters living under the bed, but a whole other society of creatures that could be either aggressive, dimwitted, clever, self-interested or kind. That’s what’s present in these photos, and that’s what Atelier Sentō seems to be aiming for in their game. Consider my interest piqued.

To learn more about The Crystal Cave, visit its official website.

Photos used with permission from Atelier Sentō.

The post Two game artists share the Japanese yōkai that inspire them appeared first on Kill Screen.

The problem with videogames that don’t trust their players

Imagine that you’ve started a new level in a game that sets the scene for endless opportunities. A new environment riddled with context clues that allow the player to consider their options on how to proceed—until an uninvited UI prompt coddles their decision-making and shatters the illusion of choice. This is the problem that Luis Antonio, creator of the upcoming Twelve Minutes, presents through his examination of the recently-released Hitman.

His game is about creating a dynamic environment that responds to the player. The game is about a man who is trapped in a time loop of 12 minute intervals, where the player must use their knowledge of what’s going to happen to change the outcome. Early footage shows dialogue but little else. The player is given no hints, no indication of what path to choose next. This hands-off approach is something that Antonio is a stalwart believer in, as he proves in his critique, which begins by him introducing good and bad examples of storytelling through cinematography, before addressing his disdain for movies “plastered with in-your-face explanations.” Then he moves on to videogames.

Most story driven games nowadays are too straightforward

Antonio describes his experience playing the second level of Hitman by analyzing the surrounding environment in detail. “As the episode starts, you have that unique moment of not knowing what lies ahead, and for a few seconds, you think your possibilities are endless. I couldn’t wait to start analyzing the environment to try and figure out, by myself, how I could get inside.” The scene is set and carefully crafted to tell a story. But as Antonio finds out, the work is ruined, at least for him, by unnecessary prompts the game uses that point out the obvious.

He adds: “subconsciously, these design choices set the tone and change my relationship with the game. It sets the standard for a ‘This is a dumb game, and I’m not expect to connect any dots.'” He explains that there is no need to pay attention to his surroundings. He won’t experience being a hitman in the way he plays the game, but it will happen when the game tells him so. “Most story driven games nowadays are too straightforward and clearly marked as ‘Leave your brain at the door’ experiences, so when someone delivers something more complex, they have to fight back expectations and explain clearly why it’s different.”

To read more of Antonio’s thoughts on why trusting your player is important, click here.

The post The problem with videogames that don’t trust their players appeared first on Kill Screen.

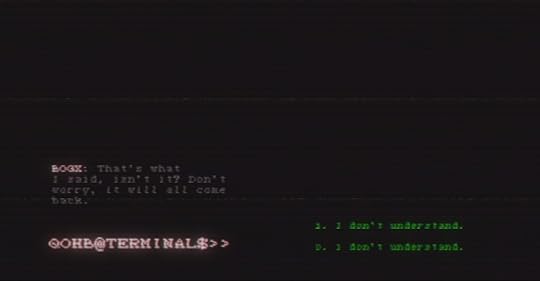

A cyberpunk text adventure explores life outside of the gender binary

“Well, here we are again,” NUGK tell me. The last time I was here, TODN was saying the exact same thing. Usernames here, including my own, are made up of a mixture of four letters, shifting each time. The post-apocalyptic world is dark, fashioned only with unnerving sounds and dimly lit text. This is the world of _transfer. Selected as part of IndieCade 2016, _transfer, developed by Hyacinth Nil and written by Reed Lewis, of the newly-formed Abyssal Studio, tackles uncomfortable issues of identity and memory.

_transfer’s post-apocalyptic theme is more than just a stylistic choice

Using a DOS-like interface, the player interacts with a number of strangers, in order to try make sense of the end of the world. _transfer‘s lack of graphic visuals, and its post-apocalyptic theme are more than just stylistic choices however. These elements more specifically reflect the difficulty of trying to make sense of one’s identity, particularly when it doesn’t conform to normative expectations and understandings. Both Lewis and Nil are queer nonbinary story tellers, and as they say in their artistic statement to IndieCade:

“_transfer was conceived as a game tackling the experience of having no words to describe yourself. Many nonbinary people go through long periods of having no outside reference for their own identities, instead having to construct one based on the assumptions of others. Science fiction, the genre of the alien and the artificial, seemed a natural lens to deal with these topics.”

In _transfer, the player lacks a frame of reference and occupies a world, which rules and mechanics are unclear and unnerving. The lo-fi grumbling audio is a backdrop for continued speech options of uncertainty and questioning in high-stakes decision making about your’s and other’s identities. It’s exciting to see a game exploring these issues from a nonbinary perspective, with nonbinary trans people so often erased from LGBTQ+ visibility.

The game doesn’t operate as a linear, one-time playthrough, but rather though multiple re-engagements. Each engagement with _transfer leads to new speech options, different encounters, and unexplored fragments, which may or may not help the player piece it all together. This part of the game gives a puzzler/detective type element to the experience, and as the creators say, “the player must construct an identity from the fragments of information given to them by others—and eventually discover their role in what happened to lead to their situation.”

_transfer leaves room for you to fill in the gaps with your own readings of what is happening, and each time you revisit the game it takes on new dimensions and meanings. The game is still in development, but the current version definitely stands well as it is. It’s on sale until the 24th of July so be sure to check it out on itch.io. You can also keep up to date with Nil and Lewis’s work on Abyssal Studio’s website.

The post A cyberpunk text adventure explores life outside of the gender binary appeared first on Kill Screen.

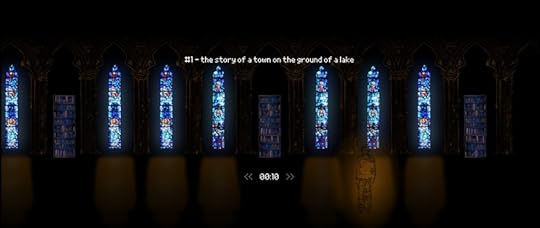

oOku, an interactive music album about navigating dreams

Dreams aren’t particularly easy to capture in any medium. Sometimes I’ll wake up convinced I just had a dream that I’ve actually had several times but never remembered before, and at the same time, I couldn’t tell you what happened in it. Given the complicated way memories of dreams work, and the uniqueness of those emotions, it’s not surprising that a lot of work tries to negotiate that uncanny space.

the line between inside and outside of the game gets blurred

Set in a sequence of your friend’s dreams, oOku doesn’t end up replicating the feeling you knew something but forgot it, but it does give you the sense that you’re building something out of inscrutable logic. And this is a feat: plenty of well-known and well-loved adventure games have puzzles that rely on obscure logic, but in the sparse landscapes of oOku, it feels like everything is there to help—to add one more piece. The game is ready to let you fail, but you can just as easily “fall back asleep” and try again, or rewind before you wake up. The looping of the dream familiarizes you with its rules, and the dream logic starts to fit together.

Playing with time—rewinding and fast-forwarding—also brings the musical themes into the forefront. Certain parts of the soundtrack help solve certain puzzle fragments, and sometimes you’ll hear lyrics sync up with what you’re doing on screen. Ordered like a kind of oneiric playlist, each dream has a different backing track, and these songs turn into something like collectibles. Solving secondary puzzles lets you separate from the dream world, achieving lucidity and “control.” From here, you can send out tweets about the game, or download its MP3s—the line between inside and outside of the game gets blurred, just like in the dreams it represents.

When I finished the last puzzle, I was pleased and surprised to learn that oOku, in its current state, describes itself as a demo, meaning that there’s more of this haunting dream-wandering to come.

You can play the oOku demo on itch.io, find out more on its website, and follow its development on Twitter.

The post oOku, an interactive music album about navigating dreams appeared first on Kill Screen.

Thumper is set to blow your damn face off this October

Thumper may not be the first rhythm game to feature a craft accelerating down winding paths in sync with the beat, but its aggressive assault of color and sound and speed promises to perhaps be the most hypnotic. The intense and otherworldly “rhythm violence” of the game has been gestating since developer Drool formed in 2009, and now, like its titular chrome beetle, is finally set to emerge on October 13th for PlayStation 4, PlayStation VR, and Steam.

“an overwhelming sense of speed and monumental dread”

In a recent PlayStation blog post, co-founder Marc Flury discussed what you should expect when the beetle lands and begins grinding its way into your life. Aside from the game itself, the pounding soundtrack that your beetle shreds along through the game’s vivid soundscapes will be released on a collector’s edition vinyl album designed by artist Robert Beatty.

The relentless speed and looming metal leviathans have only grown faster and more imposing since we last saw Thumper in March—Flury touts how the game’s improved movement, grander scale, and more polished effects have now coalesced to “create an overwhelming sense of speed and monumental dread.” One can only imagine the intensity of these refined tracks when experienced through VR, especially as Thumper has already proven to be a game of near-unmatched frenetic speed and bombastic style.

This is why it is somewhat surprising when Flury promises there’s more of Thumper‘s grind-and-slam approach to rhythm matching and its hellish worlds—that twist and roar to the music—to be revealed in the coming months leading up to the game’s arrvial.

Prepare your eyes and ears for Thumper on PS4, PSVR, and Steam. More details on the game and Drool can be found on their website .

The post Thumper is set to blow your damn face off this October appeared first on Kill Screen.

Let’s obsess over what Inside is all about

This article contains lots of spoilers for Inside.

///

When I got to the furnace I thought that was the end of Inside. Immediately my heart stopped. “Oh my god they didn’t,” I thought. But the momentum of the moment and all the crashing glass and shrill screams that had come before urged me on. The King of Limbs (as some are now referring to it) slunk closer to the wall, both of us transfixed by the flames. The blob of mangled flesh and synaptic impulses is a tragic abomination, but did the game’s creators really want it to die? I have it try to grip the furnace grate and pull it open, try to stuff itself inside, but nothing happens. Just some smoldering burns and pained yelps. This is not the end.

Where exactly the game does end remains unclear. The obvious point is a few screens later when you finally guide the King of Limbs crashing through the side of the facility down a mountain path to a sunny little beach. The monstrosity relaxes (or does it die?) and the game pauses to let you take in the scenery before bringing up the end credits. From there the player can restart the game, not just to experience every residual detail with fresh eyes and a clearer idea of the whole, but also to collect spheres littered throughout different environments that help unlock a special underground hatch.

Down there, the boy finds a machine that appears to be hooked up to a mind-control device. If you have him destroy it, his legs crumple and his body goes limp, just like so many of the lifeless husks you’ve manipulated previously. Whether you treat this scene as the culmination of everything you played through before, or as an alternate ending that effectively heads off all the events that would come after, will drastically change how you interpret everything.

And then there’s that point in the middle third of the game where the boy is snatched by one of the mutant mermaids and dragged deep underwater. She attaches what looks to be a mind-control device to him and, although he appears to drown, he’s eventually reborn somehow, now able to breathe underwater, or perhaps not needing to breathe at all.

The more I’ve racked my brain trying to piece together a theory that can account for all of Inside’s disparate elements, the more it all seems to slip away. The boy starts in the woods and eventually travels through farmland to factories to a sprawling facility that’s part abandoned city underground, part giant office complex. Sometimes people are hunting after him, other times they seem content to observe him like some sort of test subject. Once he is flushed into the tank and assimilated by the King of Limbs, you’re able to control the latter and try to escape the facility for good.

each solution feels like an uncanny turn of events

Or is that escape just another test to be observed by the people in lab coats? Was the boy trying to find his way back to the King of Limbs the whole time? And by the end of the game is the boy truly the one controlling the creature? Am I even still controlling the boy?

This is where the dream within a dream logic starts to take over and suggest a complex, overlapping web of mind control and supplanted free will. One of Inside’s more brilliant moments comes when you realize that the boy is able to chain control of different bodies by having each subsequent one hop into its own mind-control device. It’s a great evolution to the puzzle at hand, but it also gestures toward a more sinister relationship between all of the parties involved—you, the boy, the creators, and the other characters.

The way the boy is able to control other bodies in the game is analogous to how the player is controlling the boy, but also to how Playdead is able to predict and guide player behavior through often imperceptible design choices. We all know this to be true in a general sense, but one of Inside’s more extraordinary qualities is how it seems to know precisely what thoughts will pass through your mind in any given section. It’s as if the game originally had a maze in place, with only one narrow solution, but then the creators slowly started breaking down all the explicit walls and barriers, replacing them with more subtle visual cues and pacing. As a result, you feel free to approach each new room and environment however you please, and each solution feels like an uncanny turn of events, despite how thoroughly pre-constructed all of it is.

It’s this theme that I keep coming back to as I try to sort out what Inside is about—what it means, at least to me. References to coercion and authoritarian governments are littered throughout the game. The facelessness of its people and the instruments of surveillance they’re subjected to are proudly Orwellian. Even the grandiose warehouses and sprawling industrial-scapes felt reminiscent of Soviet totalitarianism, as if maintaining the very social structures required to produce such great works requires using them to oppress the populations they were intended to benefit.

the sense of a post-world order

That so many of Inside‘s buildings and underground enclosures are destroyed or abandoned gives its world the sense of a post-world order. Whether by nuclear holocaust or conventional war, its civilizations have collapsed and what remain have turned to scientists to re-engineer them. So much of Inside‘s focus is on the boy and your relationship to him that it’s easy to overlook how many ways it’s already been replicated within the game itself. How many other beings in it are hooked up to mind-control devices and probably controlling the ones who aren’t. How many other rooms and test chambers look exactly like the ones the King of Limbs broke out of.

Does it imply a program of biological and telepathic experiments aimed at recreating a society? Perhaps those who control what’s left of humanity are intent on making sure the horrors they’ve witnessed are never recreated, deciding that chaotic free will and independent thought are too dangerous not to be stamped out. In this way, they’ll settle for the sort of half-life of those shadows languishing at the bottom of Inside‘s darkest waters. But as the Cronenbergian horrors taking place above demonstrate: at what expense…?

The post Let’s obsess over what Inside is all about appeared first on Kill Screen.

June 30, 2016

Undungeon’s pixel art makes the fantasy genre fresh again

A point of honesty: I still have yet to play more than the first hour of The Witcher 3 (2015). Not because the game is bad—in fact, I’ve enjoyed what I’ve seen so far—but because at this point, I’m just too exhausted with fantasy to have much interest in delving any further. How many hours have I spent playing as men in armor swinging their swords at lumbering dragons? Or, in the case of science-fiction, playing as a space ranger swinging his light sword at insectoid queens? Granted, there are fantasy stories that work to subvert these tropes, as we’ve noted before with Bloodborne (2015), but the problem is so pervasive in the genre that sometimes I’m way too discouraged to even know where to begin. What if I keep playing and all the potential of this new world just turns out to be yet more paperback imagery?

Enter Undungeon, an RPG project from a team lead by three childhood friends who grew up with genre-style storytelling, and have gradually become more dissatisfied with it as they’ve gotten older. Undungeon seeks to buck typical fantasy trends by creating a world that is an amalgam of many, and thus home to a wide variety of unique monsters and characters that stand apart from typical fantasy character design.

The hook here is that various wildly different versions of Earth in this world have suddenly been brought together into one planet, pushing beings from different universes who were never meant to live together into proximity and forcing them to coexist. These aren’t just other versions of humans either—the beings from the other Earths run the full gamut of bizarre, from Ralph McQuarrie to H.R. Giger. Looking at the game’s website, there’s a zen monk alien, a living sarcophagus, a tubby bird man wrapped in a red cloak, and some sort of skeletal deer/tree hybrid, just to name a few. All of this is expressed through detailed, highly-animated pixel art that plays homage to classic ’90s RPGs like Shadowrun, and is set alongside rust-colored post-apocalyptic deserts that call back to Mad Max. It is a world tailor made to facilitate the artists’ imaginations.

storytelling through weird character design

The player takes on the role of a herald, sort of an emissary for their people, and must travel among these disparate communities to try to bring them together. Along the way, they’ll meet various new faces, and because the game is a roguelike and each run is different, dying just presents an opportunity to meet even more. Essentially, it’s storytelling through weird character design, and I am all about that. It’s also encouraging to see the devlog namedrop Hyper Light Drifter and Nuclear Throne (2015) as inspirations, both of which are also known for their pixel art and bizarre characters.

As of now, the game doesn’t have a set release date (though the site ominously hints “the end is near”), but that doesn’t mean it isn’t too early to appreciate it. I highly suggest following its Instagram, so you can be updated on more of its pixel art goodness as soon as it’s uploaded. There’s quite a lot to parse already, and even more on the main site, which also allows you to sign up for email updates. It’s not something I normally do, but here, I’m willing to make an exception. I haven’t been this interested in a fantasy game for a while.

For more on Undungeon, check out its official website, and follow it on Instagram and Twitter.

The post Undungeon’s pixel art makes the fantasy genre fresh again appeared first on Kill Screen.

See the speedrunning glitch that shows Mario the code that makes him

Games on cartridges in particular have pretty strict limitations on space. This means that there’s often a weirdness to the way their data files are organized, and speedrunners like the folks at the Awesome Games Done Quick event love to discover and exploit these in any way they can.

In a video posted on Tuesday, Chris Grant showed off one of these glitchy exploits to IGN’s Jose Otero. As it turns out, in the 1992 Game Boy game Super Mario Land 2: 6 Golden Coins, the data that determines how levels are shaped is right next to the data that does the rest of the stuff—memory, save games, and what have you—and both are printed on the screen in sprites.

he moves gingerly through the game’s RAM to avoid crashing it

This probably means that the creators of the game trusted that the ground and walls would keep players interacting only with the level they designed. In most games, this is the case, but every so often there appears one of those glitches that lets you fall through the world. Here, that glitch looks relatively easy to reproduce: if you drop through a specific pipe and quit the game as Mario moves from one area to the next, then when you reload the level, Mario’s position between areas will be preserved, but there’s nothing below him except code. Falling through the world means falling onto the sprites that represent the memory.

Often, a glitch like this that involves manipulating the memory of the game is too precise for people to pull off, and a Tool-Assisted Speedrun is used. In January this year, a team used a bot to inject code for a level editor into Super Mario All Stars (1993), and then fed Twitch chat into that, so viewers could design a level in this glitched-out nonsense world. As almost to be expected, the people in chat promptly broke the game.

But under the level in Super Mario Land 2, Grant can see right through the code, and knows all the precise, tiny movements and spots he needs to touch or jump through in order to fiddle with the game’s code. First, he moves gingerly through the game’s RAM to avoid crashing it or maybe even bricking the cartridge, and then he relaxes as he finds just the right blocks to break way down at the bottom of everything. After that, he can load up any level, and the game will show the end screen, which for speedrunners, counts as beating the game.

The Summer Games Done Quick event starts this weekend, and I’m sure we’ll see all sorts of weird and fascinating glitches exhibited and records broken, just like this one. For more information on that go here.

The post See the speedrunning glitch that shows Mario the code that makes him appeared first on Kill Screen.

Forza 6 glitch turns it into a much more beautiful racing game

Seizure warning: The video linked below can be a problem for photosensitive epileptics.

///

There comes a time in nearly every game’s life cycle where a series of really awesome glitches are captured. Whether it is the papery surreality of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain (2015) or the deep weirdness of the Jackdaw rising from the ocean in Assassins’ Creed Black Flag (2013), these glitches break through the manufactured reality of the games—the attempt at photorealistic textures—and show us an underlying failure in the architecture of their titles. They’re also pretty freaking sweet to look at.

Take this week’s example in triple-A glitch-dom, a break in the static textures of Forza Motorsport 6 Apex:

Uncovered by Twitter user slowb1rd, this glitch occurred when using the wrong driver on their integrated graphics card. The effect is an astonishing combination of Hotline Miami-esque rave and the gold foil paintings of Gustav Klimt. You can get a proper look at it in this video.

a drivable dance floor

It’s a synth-wave album cover you can drive through. What really makes this glitch interesting is that it appears to only affect the static textures—the cars, their interiors, and peopled audiences are all just fine… they’re just standing on a drivable dance floor.

While the glitched-out level is technically playable (and without severe frame rate drop) it does appear that updating the graphics driver to the newest version has cleared out the issue. Still, these images preserve the game in its previously glorious state. This is the kind of racing game we need.

The post Forza 6 glitch turns it into a much more beautiful racing game appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers