Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 93

July 12, 2016

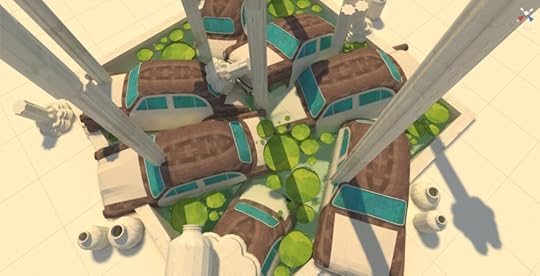

Get ready to jack in to Quadrilateral Cowboy later this month

Quadrilateral Cowboy, the next game from prolific game maker Brendon Chung, is coming out for Windows PCs on July 25th. That is very soon. Unfortunately, if you’re running Linux or OSX you’ll have to wait until September this year to get the game. Still, that isn’t too long… right?

Chung is probably best known for the two-game bundle made up of Gravity Bone (2008) and Thirty Flights of Loving (2012). Gravity Bone has a full-fledged set of opening credits, and refers to films like Wong Kar Wai’s Days of Being Wild (1990). Thirty Flights is an ambitious game that explores the limits of environmental storytelling and adapts the filmic language of the jump-cut to a first-person perspective.

gradually teaches players to understand a language of commands and timers

While Quadrilateral Cowboy is also about international crime and is set in the same 1980s retrofuture, it is “considerably larger in scope.” It will hand players a hacking rig, coach them to use a fictional programming language, and assign them two teammates with whom to choreograph the most intricate of heists. Chung has said the game takes influence from The Lost Vikings (1992) and Super Time Force (2014) in that it allows the player to switch between these characters on the fly, so she can be taking down doors or lasers at a distance with one hacker, and running another through obstacles at the same time. It’s a system that gradually teaches players to understand a language of commands and timers that encourage speed and mastery.

Quadrilateral Cowboy has been in development since early 2012, and as one of the early adopters of a growing trend in independent development, Chung has been streaming his design and development processes since at least 2013 because he believes it keeps him on task and can provide useful strategies for viewers interested in the game but also in game design.

Quadrilateral Cowboy will be coming to Windows on July 25th and to Linux and OSX in September of this year. You can find more information on the game’s website and Steam.

The post Get ready to jack in to Quadrilateral Cowboy later this month appeared first on Kill Screen.

The importance of frame-rate to a Counter-Strike pro

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

Improving skills led “n0thing” into competitive esports, but fine-tuning his PC helps him outplay others.

Jordan “n0thing” Gilbert was 16 when he gave up ice hockey to focus on conquering a new, uncharted frontier: the competitive esports world of Counter-Strike. After putting down his hockey stick for a PC, he climbed up the amateur circuit until he hit a wall. His vastly improved gameplay skills pushed his computer to its limit, and that held him back from reaching the coveted invite-level competitions. “That’s when my parents knew,” said Gilbert. “If I was going to get anything for Christmas, it was going to be a computer that could run Counter-Strike as well as possible.”

This has become a real phenomenon ever since gamers began making a good living playing games, said Travis Jank, a custom PC builder who owner of NexGen Computing who was recently in the PC modder competition “Expert Mode.” “I get parents coming to me because they’re convinced their kid has a talent for gaming, so they want to get a PC that can kickstart their career in competitive gaming,” said Jank. It’s like a musician getting a high-quality instrument that helps them develop the skills to play at higher levels.

Two years later in 2008, after getting his first gaming PC for Christmas, Gilbert upgraded to an Intel Core 2 Duo E8600 processor. That paved the way to signing with Counter-Strike team Evil Geniuses. That fall the team placed 3rd in the Intel Extreme Masters III Global Challenge Los Angeles.

Since then, Gilbert has competed at the highest level, evolving his hardware to adapt to the increasingly competitive world of professional esports. After Evil Geniuses, he joined Complexity then signed with top-tier team Cloud9. Gilbert’s PC needs to keep up with the incredible speed of his second-to-second strategic decision-making. “If things aren’t smooth, it affects your entire reality,” he explained. “Having a sub-par performance would be like a football player playing in the mud versus on grass.”

top-level players require a frame-rate well over 200 fps

In addition to practicing eight to 10 hours per day at the team house in California, Gilbert relies on his rig to give him that razor’s edge advantage during the heat of competition. His slightly overclocked Intel Core i7 5930K processor enables him to run the game at fast frame rates. While standard rigs usually strive for 60 frames per second (fps), Gilbert asserts that top-level players require a frame-rate well over 200 fps.

Players love debating the number of fps needed to run Counter-Strike competitively, but there’s no controversy in pro-circles. If a monitor has more frames to choose from, there’s less of a delay between player input and what the screen grabs when it refreshes. Otherwise, Gilbert said, “you’re definitely going to play worse.”

As Intel gaming strategist Mark Chang explained, smoothness matters most when it’s down to the wire in a match. “Let’s say you’re in a Counter-Strike match, wandering around, looking for an enemy,” he explained. “Your frame-rate shoots up because there’s not much going on.” But the minute you turn a corner to face an enemy, a whole host of new tasks need to be processed by the central processing unit (CPU), including physics and player input, according to Chang. He said frame rates can drop, bringing an inconsistent experience that can negatively impact competitiveness.

Without the necessary power, frame-rate plummets, leaving players exposed in more ways than one, making a powerful rig increasingly important, Gilbert explained. “With Counter-Strike back in the day, you could get away with [less power],” he said. “People would always joke, ‘Oh, I’m playing this game on a Game Boy.’” But by now, the joke has lost its punch.

Streaming, however, can take its toll on a player’s PC

With tournament setups becoming more standardized as esports grows more professional, teams have few (if any) qualms about dropping out if certain events fail to offer top gear. Gilbert likened PC performance in Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (2012) to a car in Formula 1 racing. A driver won’t win a competition with a sputtering car or vehicle technology that can’t deftly respond to the driver’s deftly trained maneuvers. In part, the issue stems from the constantly evolving nature of the game and gear. Esports titles receive constant updates and tweaks, requiring top players to upgrade and overclock their gear to accommodate various gameplay conditions.

Gilbert’s rig also allows him to express his personality. He’s known to let loose with freestyle raps, which can be seen on his well-followed Twitch channel. It also helps him develop relationships with his fans. He admires the rise of streaming culture, and he respects the moxy of players who, regardless of technical skill, can still acquire “massive followings because people like how they play games or like their sense of humor.” Streaming, however, can take its toll on a player’s PC. Dependent on the mega-tasking capabilities of a high-frequency CPU, quality streaming requires a PC not only run Counter-Strike beautifully, but also simultaneously and seamlessly run Twitch, audio programs, DVRs and more.

Much like the ice hockey Gilbert gave up, esports often requires players to purchase the right equipment to excel. While a gaming rig is only as strong as the player behind the wheel and a lux CPU won’t transform players into world champions, Gilbert recommends using what works best for the player’s skill level, budget and goals. “You just want gear that you like and are comfortable with,” said Gilbert. “You can’t short-change yourself if you truly want to get there.”

///

Header image via Internetum

The post The importance of frame-rate to a Counter-Strike pro appeared first on Kill Screen.

RE.CO.N takes sci-fi tropes back to the PS1 era

When you open up RE.CO.N, the second place entry in the Indie Vault Game Jam, the first thing you see is blocky grass and butterflies. Your player character is wearing a cute little hat. You have to throw things at a pig to get him to move out of your way, and then tread carefully through a yard to avoid stepping on flowers, and then the character that’s been accompanying you through these silent moments hands you a torch, gestures toward little birdhouses, and you burn them.

It’s a bizarre introduction to an otherwise sensible game. The first crackling flames give way to a short cutscene of your character watching a rocket take off, up into the dark sky. The premise, as narrated to you in those first few moments, is that the Earth has run out of resources and you’re on an expedition to Pluto to save the human race from extinction. But the premise as shown to you in-game is that you’re on a spaceship and it’s on fire.

you’re on a spaceship, and it’s on fire

RE.CO.N is very earnest in its concept, if a bit clunky, like jam games tend to be. Your little wide-eyed avatar runs around the ship, picking up objects and accidentally throwing them at the wall when you confuse the key bindings. The graphics look halfway between pixel art and those native to the first PlayStation, and fires burn conveniently in corners, cutting you off from hallways that might otherwise represent salvation.

At one point a fellow space traveler comes crawling out of one of these corridors. Slithering, like a snake, or an NPC without unique animation—and you choose to help him or kill him. In choosing to help him, I misinterpreted how to select dialog options and instead triggered shocking colors and a low-poly boot through his face. A few brief seconds of horror passed before I left to look for the next hidden coworker, leaving his burnt, twisted corpse on the ground as one does on most videogame spaceships.

Though it’s short and unpolished, RE.CO.N is an interesting jaunt through a sci-fi trope, with a twist at the end that’s predictable but appreciated. The key mechanics—activate and throw—could be used for a variety of puzzles, although there were only hints of the possibility in these 10 minutes. Like most other jam games, the potential is more important than the output, and it might be hidden behind the smoke, but it’s there.

You can play RE.CO.N in your browser on GameJolt .

The post RE.CO.N takes sci-fi tropes back to the PS1 era appeared first on Kill Screen.

Fear not, Pokémon will save the planet

Pokémon has a complex relationship with nature. It’s among the most explicit and enthusiastic depictions of natural history in kid-oriented pop culture, but environmental educators begrudge its popularity. The series gains species while our planet loses them, and that somehow feels like a bad trade—it leaves a sour taste, though it’s far from obvious that it’s a trade at all. In a sense, Pokémon’s value as an environmentalist work is something we can only see now. Climate change has touched every part of the planet, and economic development in some of the most biodiverse regions of the world is inevitable. We need ways to think about the future that acknowledge those realities, charting cultural and economic outcomes that are pragmatic but optimistic. And while it has gone largely unnoticed by its creators and its audience, Pokémon provides exactly that.

Pokémon’s origin story invokes a pastoral fantasy of preindustrial nostalgia. Creator Satoshi Tajiri spent his youth collecting insects in the rice paddies, rivers, and forests of the then-rural Machida suburb of Tokyo. Post-war economic development brought prosperity and a tech industry that would eventually provide Tajiri a successful career in game development. With that career came a chance to transmute his creek-stomping, bug-catching experiences into mass entertainment. But economic development also meant that the forests, rivers, and rice paddies themselves were logged, drained, and paved over. Tajiri’s digital simulacrum, with its 151 carefully cataloged Pokémon, replaced the uncounted thousands of real insect species dwelling in Machida for hundreds of millions of years.

Pokémon’s value as an environmentalist work is something we can only see now

This is an iteration of the most familiar trope of 20th century environmentalism: greedy, short-sighted corporations permanently destroying ecosystems with no regard for their intangible worth. It’s Fern Gully (1992), it’s Avatar (2009), it’s most particularly the neglected Studio Ghibli classic Pom Poko (1994). But while its origin myth places Pokémon in a familiar discourse about nature, that narrative is oddly absent from the games themselves. Rather than having Ash fight developers to protect Pokémon habitats, conflict comes from defanged terrorism espousing marginalized ideologies. The environment is entirely static and unthreatened, as if it has reached an equilibrium and come to terms with the economy.

For a landscape full of wild nature to feel safe alongside a technologically-advanced, ostensibly capitalist society is a somewhat unfamiliar juxtaposition for us. It feels like a fantasy, a wish fulfillment in which Tajiri keeps the prosperity and technological tools of his adult life while returning to the unspoiled countryside of his childhood. As if the games were pretending that technological capitalism wasn’t inherently at odds with wild nature, shielding their young audience from the disenchanting truth. While Pokémon’s writing is often charming, its approach to its themes is generally shallow, so this have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too fantasy of nature and technology in harmony is generally written off as a necessary premise that would fall apart under closer questioning. That’s unfortunate, because questioning that premise reveals that Pokémon offers a compelling and progressive vision of the future of nature in post-industrial economies.

Pokémon’s worldbuilding is opportunistic, rarely passing up the chance to reference a real-world animal trope or make a bad pun, even when doing so undermines the coherence of the culture and ecology of Kanto, Johto, and their successors. The rhetoric of the terrorist Teams often hinges on environmentalist philosophy, but inevitably feels like a poorly understood misapplication of real-world ideologies. The Pokémon Yellow manga arc poses the Elite Four as proponents of Intentional Human Extinction who want to give the world back to the Pokémon. Pokémon Black/White’s (2010) Team Plasma has comparable ideas, aspiring to release Pokémon from their servitude to trainers. Both seem to make reference to radical environmental groups like the Animal Liberation Front, but in the context of Pokémon they come off as utterly foreign ideas. The narratives of systemic violence and oppression they refer to just don’t apply within the Pokéverse.

Yellow Chapter, Pokémon Adventures Manga

Yellow Chapter, Pokémon Adventures Manga

Aside from its often-incoherent stories, however, everything about the Pokémon world reflects a coherent environmental philosophy. It acknowledges that humans—even industrial humans—are part of nature. In the tradition of environmental historian Bill Cronon’s work on the Wilderness Myth, it understands that emphasizing “virgin” wilderness is a counterproductive and misleading fixation, erasing histories rich in positive human interactions with nature. The Wilderness Myth is largely a Western concept, a product of colonial interactions with landscapes depopulated by disease and genocide. Landscapes in Japan have been densely inhabited and thoroughly exploited for many centuries. Tajiri’s Machida stomping grounds were carefully managed rice paddies and forest borders exploited for wood, fertilizer, and fuel. This border landscape, called Satoyama, is a touchstone of the magic of nature in Japan, embodied by Studio Ghibli’s forest spirit, Totoro. It also provides crucial habitat for animals and insects, many of which benefit rice farmers by controlling pests, pollinating crops, and mitigating pollution. Satoyama is an example of a pattern of ecological coexistence called reconciliation ecology. The ecologist who developed the concept, Michael Rosenzweig, defines it as “the science of inventing, establishing, and maintaining new habitats to conserve species diversity in places where people live, work, or play.”

Rosenzweig points out that even after they are paved and developed, suburbs like Machida aren’t ecologically barren. With some thought and attention, those resources can be shaped to support greater biodiversity. In practice, Rosenzweig’s examples are found largely in agricultural systems like Satoyama and in historical happenstance, like peregrine falcons nesting on concrete skyscrapers in place of limestone cliff faces. But dozens of intentional techniques exist, from green roofs and native plant landscaping to nest boxes for birds and bats. And with thousands of species already endangered and human land use expanding exponentially, it is increasingly clear that conservation biology can no longer turn down these modest opportunities to improve habitat. The entire world is reaching densities of land use that Japan hit long ago, and it must adapt strategies like Satoyama to achieve a comparable sort of sustainability.

Satoyama in My Neighbor Totoro

Satoyama in My Neighbor Totoro

Alongside preserving existing habitat and incorporating reconciliation techniques within human land uses, enacting a regional-scale conservation plan usually requires converting some agricultural and industrial land back to native habitat. This process, known as ecological restoration, involves planting seeds of plants native to the site before it was developed, as well as reestablishing populations of animals no longer found there. Unfortunately, restoration is currently only possible for surviving species, though some ambitious—and perhaps radical—conservationists point to developments in cloning technology and suggest that extinct species will be eligible for biotechnological resuscitation within a few decades.

At the moment, restoration and reconciliation practices are scattered and poorly supported, limited to places where conservation-minded people live and vote. They are constrained by cultural resistance and economic marginalization. Both factors are resolved completely by Pokémon’s premise, and the consequences are written on the landscape.

The culture and economy of the Pokéverse are oriented almost entirely around Pokémon, providing a near-universal investment in conservation. It’s the realization of the dream of ecotourism—a sustainable market based on the appreciation of nature rather than its exploitation. The economy is affluent and post-industrial. Nearly every character either works a Pokémon-related service job or spends their free time battling and practicing a hobby—often related to outdoor recreation, like roller-skating, swimming, or hiking. In Pokémon X/Y (2013), the only land uses that aren’t inhabited by Pokémon are the Poké Ball factory and the solar power plant, both pillars of the Pokémon economy seen in action everywhere else. Even in the most “natural” areas, every space is thoroughly netted with signs and paths. Infrastructure is provided to cross rough terrain. You’re never far from a Pokécenter, and there are usually dozens of tourists around. It’s not an untouched wilderness, but a working landscape.

It’s the realization of the dream of ecotourism

The whole environment, including roads, towns, and natural areas, appears integrated into a publicly managed regional plan. Each region includes distinct habitat types—beach, cave, forest, ice cave, haunted house, abandoned power plant—suggesting an intentional effort to support a high diversity of Pokémon types, attracting tourists and supplying the Pokémon whose capture drives the economy. And while a few legendary Pokémon seem to need large, undisturbed areas, the rest of them appear habituated to constant human presence and relatively small patches.

The historical trajectory of this landscape mosaic is never discussed. Whatever extinction, evolution, and adjustment took place to reach the present distribution of Pokémon has apparently already taken place. It is possible, though perhaps unlikely, that all of the natural areas we see have never been substantially altered by humans. On the other hand, with fossil revivification, the technology is there to achieve the Jurassic Park dreams of the most enthusiastic and reckless rewilding advocates. And captive breeding of Pokémon is a reliable and commercialized technology, so small endangered populations could easily have been reared back to target abundance. Ecological restoration would be comparatively cheap and easy in the Pokéverse, and the demand for places to catch wild Pokémon clearly make it worthwhile. That said, without any sense of the history or management of these areas, it’s unclear whether their current distributions reflect historical ecology. It’s possible that natural areas are stocked with economically-desired Pokémon the way many local governments regularly introduce non-native sports fish into lakes and rivers.

The mosaic of roads and habitat patches in the games matches the distribution of Pokémon neatly, but this artificial stability belies the tendency of real wildlife to wander between patches. Roads are lushly supplied with grassy, no-mow zones, supporting more common and agrarian Pokémon. In theory, this should allow roads to act as corridors, safe routes that allow Pokémon to move between other habitat types. Such movement is an important technique to protect species from extinction, allowing patches with depleted populations to be recolonized by migrants from more robust populations. In practice, Pokémon never move beyond the boundaries set for them by the developers. But at least on paper, regions are designed to accommodate dynamic, interconnected ecosystems based on modern landscape ecology.

Yellow Chapter, Pokémon Adventures Manga

Yellow Chapter, Pokémon Adventures Manga

Cities are the weak link in Pokémon’s reconciliation ecology credentials. With a few cordoned-off exceptions like sewers, the games use cities as safe hubzones, completely free of wild Pokémon encounters. This sort of missed opportunity suggests that Pokémon’s ecological philosophy may be inadvertent. On the other hand, Pokédex lore and some scenarios from the manga and anime show that many wild Pokémon exist in cities as well—particularly, those Pokémon that seem to exist only through the creative tension between humans and nature. The Pokéverse’s post-industrial history is written into the bodies of these Pokémon. Some electric types, like Pikachu, might invite comparisons to evolved creatures like electric eels, but many of their designs are explicitly industrial, and they often consume grid-generated electricity. Koffing, Grimer, and Trubbish are living accretions of pollution and trash. Like pigeons, rats, and cockroaches, all of these Pokémon have evidently been transformed by close relationships with urban economies, even if their progenitors may have existed before industrialization.

Pokémon GO has thoroughly rectified that urban oversight. The game attempts a rough habitat mapping, urban Pokémon in cities, bug types in parks and forests, and water types near lakes and rivers. As a result, most players have been flooded with uber-common synanthropic Pokémon like Rattata and Pidgey, devaluing them as “trash” just as familiarity has bred contempt for real urban animals. On the other hand, as players seek out Pokémon in urban environments, their encounters with squirrels, pigeons, and rats will perhaps make Pokémon’s parallels with biodiversity coexistence easier to frame. Pokémon GO lacks the utopian world building of the games, but it will certainly color how players experience the upcoming Pokémon Sun/Moon.

Pokémon GO has thoroughly rectified that urban oversight

While natural areas are thoroughly enmeshed in the human economy, they aren’t necessarily safe. Wild areas are designed to be places where trainers interact with wild Pokémon in battles with strict norms of fair sportsmanship. Trainers rely on domesticated Pokémon to protect them from wild creatures, which apparently attack humans passing through their territory. This relationship acts out in microcosm a tenet of human history often neglected by simplistic “man versus wild” stories (regardless of whether man is depicted as conqueror or desolator): humans have survived and thrived in a hostile world only by cultivating positive relationships with animals, plants, and microbes. Pokémon trainers, with their diverse, mutually reliant teams, are among the few figures in the fantasy genre that give proper credit to those relationships.

Pokémon’s capturing mechanic references our boundary between wild and domestic animals, but it shifts that line from the species to the individual level. Domesticating a Pokémon involves the instant formation of a psychological bond, not a gradual genetic change. By making every Pokémon eligible for partnership with humans, every other category we apply to animals is blurred as well. A few Pokémon, like Machop, are used as beasts of burden, but they are also fighters and companions for the laborers that use them. Pikachu appears as a restaurant pest in the manga—they are mice, after all—but also a source of backup electricity in the anime. Misty has a phobia of bug-type Pokémon in particular, but she doesn’t think it’s appropriate to kill them. No one ever mocks someone for catching and fighting with a particular Pokémon. Pest, vermin, predator—categories that still keep people from embracing rats, possums, or wolves as part of our ethical responsibility—have been transcended.

A Machoke construction worker, Diamond & Pearl Episode 57

A Machoke construction worker, Diamond & Pearl Episode 57

Every few years when a new Pokémon title is released, Game Freak’s artists give the kawaii-culture treatment to another hundred animals, plants, and abstract ideas. That’s the logic of capitalism at work, but it resonates with an increasingly ecumenical relationship with nature. Pokémon makes no distinction between cute pets like puppies and kittens and wild animals. Everything is available for consumption and capable of productive relationships with people, given the right approach from the trainer. This is the nature fantasy of an urbanized population, people who interact with nature primarily by watching baby animal videos. Many such videos are from animal rescue shelters that support themselves by marketing the cuteness of their unique and exotic wildlife—see Vice’s The Cute Show, much of Animal Planet’s programming, or the incredible number of possum rescue pages on Facebook. Our consumptive horizon has widened, and our ethical and economic horizons are gradually following. After all, the slogan is “Gotta catch ‘em all”—no outs are provided for gross, standoffish, or dangerous Pokémon.

Pokémon is a strange beast. In a sense, it seems to have deliberately ignored the negative implications of economic development in a way that feels almost disloyal to its origins. On the other hand, its rhetoric frequently invokes a dramatically exploitative history between humans and nature, even though that relationship otherwise feels anachronistic in Pokémon’s idealistic future.

The series is unapologetically utopian, erasing or belittling many of the most consternating philosophical and material issues standing between us and its endpoint. But its philosophy completely shatters the Wilderness Myth, presenting a culture that manages to be ecologically inclusive and ethically egalitarian despite retaining the responsibilities of a technologically-bestowed power dynamic between humans and nature.

Rosenzweig sees “reconciliation ecology as the great environmental educator. The environments it creates will teach us once again how to take pleasure from Nature. The species we live with will resensitize us to her delights and addict us to her bounty.”

Environmental educators treat digital nature as a cheap substitute, claiming that we need to “get kids outside” to experience “real” nature instead of playing videogames. That’s an important effort. But it might also be true that Pokémon’s vision of a post-industrial culture intimate with a wealth of wild creatures could serve Rosenzweig’s purpose as well. The series provides a plausible blueprint for a world that addresses many of the environmental catastrophes we have to deal with in the next century. Pokémon deserves credit for advancing that vision, however inconsistently and accidentally, introducing intentional coexistence with all wildlife to millions of people not as a nostalgic fantasy, but as a compelling vision of the future.

The post Fear not, Pokémon will save the planet appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 11, 2016

Arms of Telos is all about the thrill of moving at blistering speed

There’s an almost innately satisfying thrill in going fast, in moving beyond the limits of our biology. You see it in the one-upmanship of supercar speed specs, touting how rapidly the newest model can roar from 0 to 60 and push past the 200mph mark. In the excitement of plummeting towards the earth while skydiving or speeding through open air on a zipline, or just the joy of driving with the convertible top down and the wind whipping through your hair. In the rise of acrobatic activities like parkour and free-running, how they allowed one to ignore the typical walkways and move through the urban landscape with fluidity and celerity. Or in the elegant flight of a wingsuited individual as they caress cliff faces and rocket through narrow mountain passes.

rocketing through space at incredible speed and snagging structures with your hook

We like speed, breaking the barriers of movement, and in the virtual world, games have only followed suit. Descent (1995) let you freely fly through its claustrophobic corridors. Quake (1996) broke the mold with moves like rocket-jumping—no longer were you bound to the confines of game physics and movement, but could subvert and escape those limits through skill. Mirror’s Edge (2008) injected the first-person perspective with the skillful traversal of parkour, while Assassin’s Creed (2007) turned the environment itself into an extension of your movement as you scaled historic architecture.

The upcoming competitive shooter Arms of Telos continues that trend, by combining myriad movement types into a dynamic traversal system that can shift from swinging through sci-fi landscapes like a certain arachnid hero to barreling through space with the agility of Descent’s crafts.

“The biggest thing that sets it apart is the movement,” explains one-man team Justin Pierce. “You pilot a very agile spidermech in zero gravity with pockets of gravity in indoor areas and special magnetic surfaces, but you can also get going really fast to where it’s almost a racing hybrid.” Arms of Telos isn’t confined to a single plane of movement, but rather changes it depending on the player’s location. Within a structure found on one of the game’s vibrantly-colored low-poly arenas, gravity plants your feet on a surface, be it a wall or floor or ceiling thanks to magnetized tiles. But in the zero-g space outside, thrusters and a grappling tether guide your movements, divided between rocketing through space at incredible speed and snagging structures with your hook to turn your momentum into deft swings.

Within the framework of such movement-focused gameplay, Pierce plans to create a skillful strategic arena shooter that actually takes more inspirations from racing games than perhaps its first-person shooter brethren. In a blog post explaining the challenges of refining aiming and shooting in a game with extremely fast movement, he states how “it’s similar to tuning your gear ratios in a racing game. Some gear ratios may be better suited for different tracks, but it also comes down to personal preference.

Allowing players to tune them to their own preferences will hopefully give them a better sense of ownership over their experience.” Those preferences revolve around an exotic array of weapons and items that would allow players to design their own fast-paced tactics, ranging from a teleporting blade for the melee-inclined to deployable speed gates and shields.

Arms of Telos is expected to release on PC, Mac, and Linux. Visit the game’s website and TIGSource devlog for more details and GIFs.

The post Arms of Telos is all about the thrill of moving at blistering speed appeared first on Kill Screen.

Somewhere is back, and it has new, surreal images to show you

The two-person Studio Oleomingus has resumed work on Somewhere, their first person exploration game set in an alternative Colonial India. To demonstrate, they’ve given us a new peek at an environment in their surreal polygonal world.

The first screenshot shows off a car, maybe from the early ’60s, but made of wood paneling and with giant antlers poking out the top. The following slides feature several of the vehicles, clustered together like deer at a watering hole, but surrounded on four sides by walls, left without wheels and suspended in a floor that’s swamp-like but also vibrantly-patterned.

the archaeological process of memory

Oleomingus also uses a clever trick to pull aside the curtain behind their scene design somewhat—successive screenshots includes more visible technical details. The first screenshot is a purely presented scene, but the next several images contain wireframes and different lighting effects, and a wider view introduces an icon for an invisible sound source in the Unity development engine as well as the wireframe for the game camera through which other shots were taken.

Another set of screenshots shows the same cars (without antlers this time) crowded into a fountain-like structure, overlapping with one another and with columns coming up out of the water. Here, amid the broken columns topped with over-turned jars, the cars look less animal and more like natural refuse, like so much mud, gumming up the water works.

Accompanying these screenshots is a short bit of text that describes “the periscope city,” and a populace that is always looking—as through a periscope—one level above them. But, more than a description of the fantastical architecture of a city, the parable touches on the danger in this sort of neighborly anxiety: by always looking just above, the people of the periscope city doom themselves to digging ever downward. The post continues, “even in the periscope city, people do need to visit the basement. Where they might have stored that old collection of newspapers or those spare switches. And since they cannot see into this bottom-most chamber they are required to dig a room right below it… so the city continues ever downwards.”

The text sits alongside these images that present the points of view of other images in the same set, and Studio Oleomingus uses that juxtaposition to pose questions about how we create and present specific perspectives, and about the archaeological process of memory.

You can follow the development of Somewhere here. You can also play one of their demos—Rituals, Timruk, or Menagerie—on itch.io.

The post Somewhere is back, and it has new, surreal images to show you appeared first on Kill Screen.

Calling all Buffy fans: A videogame made in the style of a vampire TV show

For most of the last decade it was zombies that seemed to take over videogames. Almost every game from forklift simulators to open-world cowboy experiences have had zombies show up in them. These non-living monsters are everywhere and their popularity doesn’t seem to be dying. But there is another undead enemy who deserves better representation in modern games—the vampire. There have been a handful of vampire-focused games in the last decade, but most of them haven’t been very good. And none of them have tried to recreate the feel of the fantastic Buffy The Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) television show. Slayer Shock is doing just that.

Slayer Shock is being developed by David Pittman, who previously created Eldritch and Neon Struct. Slayer Shock seems to be taking elements and ideas from those previous games and mixing them into one vampire-themed game. It has the stealth of Neon Struct and the procedural levels of Eldritch. But where Eldritch’s levels were strange and chaotic, Slayer Shock’s levels resemble something closer to the real world. The game is set in Nebraska, after all, and Pittman has been working hard on making sure the levels get that across.

In his development blog, Pittman has explained how Slayer Shock is being designed to feel like a TV show—oh yes, the Buffy reference wasn’t for nothing. Each mission you go on in the game is considered an episode. These episodes make up a larger season. Each season will have a “big bad” that you and your team will need to defeat. As you continue to fight back against the big bad they will make their presence felt, even appearing in episodes during the season to taunt you or disrupt your mission.

Pittman is also including a system of “twists” which can happen during an episode. One example given is an episode in which you have to complete the mission in pitch black while using a flashlight to make your way through the world. Other twists could include spawning harder enemies or more monsters, etc. Other tools and weapons available to you during these missions will be familiar to anyone who has seen vampire films or TV shows. Stakes, crossbows, holy water, and more are available for all your slaying needs. You’ll be able to buy and upgrade new tools and weapons between missions too.

familiar to anyone who has seen vampire films or TV shows

Your team in Slayer Shock is a group of your friends and your base of operations is a college coffee shop. Your team is young and busy with their own lives, so sometimes they might be too preoccupied to help in the quest to kill vampires. For example, a character who is supposed to research something for you is might be dealing with exams and therefore won’t be able to help that night. No matter who does end up coming along, if you fail your mission, you and your team will have to regroup and replan for next time, and the season will change depending on how well you do during each episode.

In this way, Slayer Shock blends procedural generation with an episodic-style narrative. Pittman explains on his blog that one of his main goals for the game is to provide lots of opportunity to generate player stories. To allow players to each have their own series of episodes and moments that should feel unique to them. Something that will be memorable and totally unexpected.

Slayer Shock is coming out later this year. You can read more about the game on its website and dev blog. You can also check out Slayer Shock on Steam Greenlight.

The post Calling all Buffy fans: A videogame made in the style of a vampire TV show appeared first on Kill Screen.

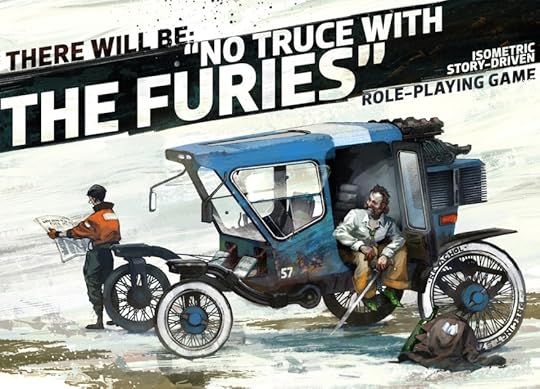

No Truce With The Furies is the isometric RPG to look out for

A revolution-wrecked port city. An enthusiastic policeman out of his depth. “Neither fantasy, history, nor any kind of -punk.” Helmed by a “chronically success-impaired” science-fiction writer and describing itself as a combination of Planescape: Torment (1999), Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare, and Kentucky Route Zero (2013), it’s a game about “being a total failure.” The first question on the developer’s FAQ is, “Is this a joke?”

“No, it’s not,” says Estonian developer Fortress Occident. “It’s a real game. We’re making it.” And for the debut project of a studio that’s only been around since October, No Truce With The Furies is looking good.

The isometric RPG has been going through a passionate, if quiet, revival in the past few years. Obsidian Entertainment, final resting place of most of the Black Isle developers that worked on the original Fallout (1997), created Pillars of Eternity (2015), a nostalgic callback to their Infinity Engine-powered past—at the time it was the most successful Kickstarted game ever. Tyranny, their next game, looks to the same inspirations. Even the long-dead Fallout predecessor Wasteland (1988) was resurrected in 2014 to a lot of noise and then radio silence. No Truce With The Furies comes from the same stock—I did a double-take at the first screenshot because, wow, I didn’t think Fallout ever looked that good—but it has no desire to confine itself to fantasy or the post-apocalypse. Fortress Occident are doing something all their own.

Fortress Occident are doing something all their own

The setting has taken 15 years to develop, or so their website says, and it’s been dubbed “fantastic realism” by a novel set in the same universe. The world building so far is intense: it takes place in the city of Revachol, which seems to be a run-down coastal melting pot of cultures that could be analogues to any number of modern countries. They describe “Semenine” immigrants that bring their own architecture and (techno!) music to the city, a “Mesque” district with gangbangers that wear mesh wifebeaters, and lingering structures described as “Havana-esque” being demolished to make way for an ever-expanding commercial port. They specify that Martinaise, the neighborhood where No Truce With The Furies is set, is still recovering from war. It’s scarred into the houses and the landscape, locals constructing humbler buildings on top of the ruins to start all over again. Having gone through their share of uprisings, wars, and rebuildings, it’s no wonder such foundational commentary is coming out of Estonia. It couldn’t be more different from Fallout’s nuclear Americana.

That being said, No Truce With The Furies looks like the opposite of a dark game. You play a bumbling, incompetent police officer sent from a wealthier district into Martinaise, thinking of yourself more like a rock star than a law enforcement officer and waiting, for some reason, for an event called the “Tequila Sunrise.” Fortress Occident wants to focus on narrative instead of combat, which they elaborated on in a recent blog post, being far past the point where the words come easily. They describe the endless press of games writing as “the damn landing of Normandy; taking it by force.” But they don’t seem concerned; delays will happen as they happen, and since they’ve steered clear of Kickstarter or other crowdfunding, they’re not stuck to a release date. Right now, it should be out by the end of 2016.

No Truce With The Furies is Fortress Occidental’s mainstage debut, short-form preparation for something bigger and better coming up in the future. Compared to their eventual ambitions, it’s small-scale. But you wouldn’t know that from looking at it.

Check out No Truce With The Furies on their website and on Facebook .

The post No Truce With The Furies is the isometric RPG to look out for appeared first on Kill Screen.

The mixed reality mods that are changing Minecraft

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

More than 20 million people use their imaginations to create endless virtual worlds in Minecraft (2009). Unlike most games, however, players (rather than developers) push the boundaries of Minecraft’s expansiveness. They build everything from virtual voxel versions of the Taj Mahal to the entire country of Denmark, replicas of things that exist in the real world but can be shared and modified in world of Minecraft. “The Minecraft community brings together coders, artists, musicians and content creators from all over,” said Razz, a modder best known for her decorative block models. Razz said many players are using Minecraft mods to transform the game beyond its original intent. These Minecrafters aren’t just playing a game, they’re shaping the future of virtual and augmented reality entertainment.

Minecraft Goes Virtual

Years ago, the Minecraft modding community caught the attention of John Carmack, CTO of Oculus who is virtual reality (VR) evangelist and famed game developer of the original Doom (1993). At the Oculus developer conference earlier this year, Carmack called Minecraft “the single most important application we can do for VR.” He said Minecraft has the potential to create a “metaverse,” or 3D virtual space that invites people to congregate and be physically present with one another. With its infinite worlds, and links between servers and user-generated content, he sees Minecraft bridging virtual creation with physical space. Microsoft has been working to bring Minecraft to life with the augmented reality headset Hololens. At the recent E3 event, they showed off a demo that set both Minecrafters and tech journalists abuzz with new possibilities.

Augmented reality can allow for more intuitive user-generated content

Though still in the prototyping phase, Microsoft’s corporate vice-president Kudo Tsunoda told The Guardian the Hololens is an incredible tools for digital world modders and creators. “Most people don’t have an inherent understanding of how to create in 3D — it can be very complicated on 2D screens,” he said. Augmented reality can allow for more intuitive user-generated content. “I think we’re going to see more communities adding to and customizing the games they play, and that will be very cool,” he said.

Mixed-Media Modding

The mixed-reality approach suits Minecrafters so perfectly that real-life electronic building blocks known as littleBits are now being used in the game to blend hardware modding with software modding. With bitCraft, modders can use littleBits’ hardware in conjunction with Minecraft’s “redstone” (a building block that acts as something of an electrical current) to invent objects that seamlessly jump from one reality to another. “It’s a way to give a real-world presence to the things they make,” said Stan Okrasinski, the developer of bitCraft. “In connecting to the real world, you think about Minecraft in a different way. On the base level, it feels like magic.” Liza Stark, a bitCraft modder and educator, explained how this mixed reality can expand the horizon for Minecraft as a teaching tool.

“It offers a completely new play experience that requires a different set of problem-solving and critical thinking skills,” she said. “Since you are building in real life and in a digital space, you must negotiate how they interact.” Modders have used bitCraft to create trap door intruder alerts that trigger an actual alarm, dimmable light switch for setting the mood for a reenactment of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and an entire Minecraft smart home. Block Maker from VoidAlpha, yet another piece of new tech, uses Intel’s RealSense camera to 3D scan real world objects and render them in Minecraft’s virtual world.

By turning object by hand or on a turntable in front of the camera, a digital version of the object is created and ready for the voxel world of Minecraft. Mark Day, chief executive at VoidAlpha, sees Block Maker as a new spin on the toy-to-life trend, where physical figurines and objects can be used to “teleport” the player into the game world. “Something you’re intimately familiar with in the real world can suddenly become part of your virtual world,” said Day. “It’s an inverse of the toy-to-life. It’s life-to-toy.” Unlike the existing toy-to-life games like Activision’s Skylanders, Disney Infinity and Nintendo’s Amiibos, Block Maker allows kids to bring any item, like a beloved teddy bear or even a pet hamster, into the virtual space. “People spend hours and hours creating amazing worlds, but they can only build what they have at their disposal,” said Eric Mansion, RealSense Evangelist at Intel. “The idea of being able to bring real-world items into their amazing Minecraft creations is understandably very attractive.”

They’re shaping the future of virtual and augmented reality entertainment

Though yet to be released, many modders anticipate Block Maker as a way to significantly cut down on the hours upon hours it takes to create objects for Minecraft. Razz said its capabilities could save “modelers and modders quite a few hours of work.” Just how Minecraft Hololens makes creating in 3D space easier, Block Maker was also designed to lower the barrier to entry for potential Minecraft creators, regardless of their modding skills. “I wanted somebody’s nine-year-old kid to be able to use it,” said Day. “It’s a way for them to add objects that are personalized to their Minecraft adventures.”

Others, like bitCraft modder Brendon Trombley, believe Block Maker could blur the line between reality and virtuality in user-generated content even further. “Imagine scanning an object into Minecraft using Block Maker, linking that to a 3D printer, then printing that object in real life, except now it’s Minecraft-ified!” he said. In the end, however, Minecraft needs little help when it comes to immersing and grounding its players in a seemingly real virtual world. “Ask any player and they’ll tell you their in-game experiences feel real in ways that a non-player might not understand,” said Trombley.

All Minecraft images display modder Razz’s work.

The post The mixed reality mods that are changing Minecraft appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Lion’s Song takes you back in time to tackle creative block

There are a lot of adventure games that can leave you feeling stumped. Scanning the environments, trying to wedge objects together like a baby mashing toys, clicking up and down the page like the moving parts of a fax machine before giving up, perhaps indefinitely. Maybe this frustration is where the point-and-click format clicks with another damning mental slog, namely in Mipumi Games’s The Lion’s Song, a serene and novel story about creative block.

When the pain and the ecstasy blend, you find clarity

Expanding on a game from Ludum Dare 30, the first chapter of The Lion’s Song focuses on Wilma, a composer and performer who is abruptly asked to create a piece to perform for pre-war Vienna’s esteemed artistic circles. A professor, who Wilma harbors feelings for, sends her into the Alps to stay at his cabin, isolated from distractions so she can complete her piece. The solace doesn’t prove productive, at first, until a Czech man, Leos, happens to ring the cabin’s telephone with a wrong number.

The game has you searching on two fronts. The first to combat distractions, rogue horrible noises that screech like screws on a chalkboard, amplified by dreads emanating from other places in Wilma’s life. Then to seek inspirations, through your cosy surroundings and intimate conversation with the faraway Leos. When the pain and the ecstasy blend, you find clarity, and make music flow.

The first chapter, Silence, follows the original jam game fairly closely. The upcoming chapter will shadow a new artist, a painter, who appears even more skittish than the timid Wilma. The first chapter is available is available on Steam for free, so you too can see if you can subdue creative insecurity. Well, creative insecurity with guaranteed answers on the horizon, at least.

You can download The Lion’s Song over on Steam.

The post The Lion’s Song takes you back in time to tackle creative block appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers