Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 95

July 8, 2016

Democracy 3: Electioneering is a misguided publicity stunt

In his 1989 essay “The End of History?,” the political scientist Francis Fukuyama, engorged by the collapse of the Soviet Union, claimed that human civilization had reached the conclusion of its sociopolitical development. “What we may be witnessing,” he writes in summary,“is the endpoint of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” When later pressed for examples of what post-historical governance might look like, Fukuyama generally pointed to the example of the European Union, a supranational entity inspired (in his view) by an attempt to transcend national sovereignty, a defining characteristic of his post-historical world.

The ‘inevitable,’ though, has a way of unravelling in spectacular ways. Fukuyama’s post-Cold War optimism has been looking rather jejune lately, as liberal democracies across the West have found themselves strangled by a resurgent nativism that has helped spawn, among other iniquities, Trumpism, Norbert “Put Austria First” Hofer, the Brexit, France’s far-right National Front, and… need I go on? Arrange those embarrassments alongside the failures of the nominally pro-democracy Arab Spring and Orange Revolution, to say nothing of the abuses committed by the democratically-elected governments of Thailand and Turkey and, well, Fukuyama’s democratically-centered vision of the ‘end of history’ is looking tenuous indeed.

what does it even mean to represent democracy in/as a videogame?

So when I receive an email inviting me to review British studio Positech Games’ Democracy 3: Electioneering that opens with the question, “With all the political madness currently engulfing us, isn’t it time for some clear direction?,” I am almost at a loss for words. Isn’t the problem not that we’re lacking a clear direction, but that the direction towards which liberal democracies are tilting is all too clear? And, more importantly, that this all-too-clear direction is a fucking nightmare? A game designed to simulate the operations of a functioning (or not) democracy is going to be politically charged even under the most copacetic of historical circumstances. But at a moment when many on the left, myself included, have never felt more hopeless about the future 2016 augurs, what does it even mean to represent democracy in/as a videogame?

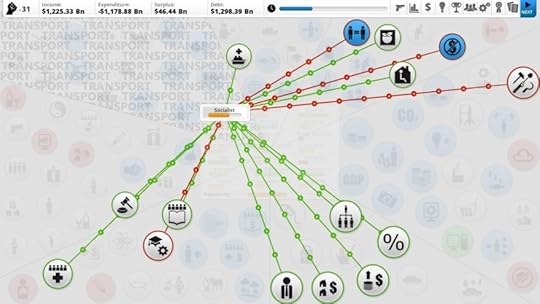

The original Democracy 3 (2013) was an impassioned procedural argument for incrementalism, the belief that political change is best enacted through an ongoing series of small adjustments. Success in the game—defined as the ability to realize your political ambitions, whatever their ideological bent, by raising and expending political capital in favorable ratios—was entirely the province of compromise. Democracy 3’s iconic, elegant interface is an array of bubbles representing particular policies connected by pulsating red and green arrows, which indicate the force policies exert on popular opinion. This interface forced players to acknowledge that this was no opportunity for moral certitude. Once, when faced with a scientifically illiterate and globally uncompetitive workforce, the only practicable way for me to ban mind-dulling creationism from schools without losing reelection (or worse) was to restrict access to abortion.

Unnerving though it is, there is a begrudging kind of truth to this argument: democratically elected politicians can rarely afford to be the face of anything but the most moderate changes without risking the very platform that enables them to enact change in the first place. Democracy 3, in this sense, suggested 1) that the continual recalibrations politicians make is not a weakness of liberal democracies, but a condition of their existence, and 2) that compromise, in both its moral and practical dimensions, is part of the price we pay for the ability to elect our leaders (see Kill Screen’s David Rudin for more on the game design of democracy). To be sure, this view represents a particular way of thinking about democracy, but it is also very hard to discount without ceding any claim to an actionable platform.

Electioneering is Democracy 3’s fourth expansion, but with the notable exception of Drones and Clones (2015), a surprisingly thoughtful speculative fiction on the fate of policy in an age of automated economies and bioinformatic surveillance, Positech has largely turned its attention to the complicated (and complicating) minutiae of liberal democracies. Social Engineering (2014) focused on micro-policies—think widened bicycle lanes rather than rent-controlled housing—while Extremism (2014) enabled policies beyond what a congressperson may mention in public (from Extremism’s press release: “For when fiddling with tax rates isn’t enough!”).

“politics is theater; it doesn’t matter if you win”

The purview of Electioneering is the public ritual of the election and the forms of rhetoric that it constitutes and is constituted by. There are no new policies upon which to ruminate, but there are publicity stunts and speeches and manifestos and focus groups and grassroots organization and donors galore! Above all, Electioneering is attuned (and committed to) the artificiality of political communication as a continually calculated performance. When Harvey Milk said “politics is theater; it doesn’t matter if you win,” he wasn’t wrong. Neither, for that matter, was Paul Ryan when he dismissed congressional Democrats’ recent sit-in for gun control as “political theater.” Of course it was theater. What protest isn’t? Electioneering, though, exaggerates these practices into the political theater of the absurd; why pose on an aircraft carrier when you can land a goddamn fighter jet yourself for a 20 percent boost in public perception at the low cost of six units of political capital?

And, look, there’s still something to this. When we mock political communication for its blatant lack of “authenticity” (whatever that is), we’re diverting attention away from why it’s “inauthentic”—which is that it’s the rhetorical appeal to which people have responded most. And it’s a whole lot easier to scapegoat the public performance of politics, a performance whose purpose is always known in advance, than it is to admit the collective failures that set the conditions and causes of that performance. Electioneering, in its way, reminds us that it makes little sense to solely blame politicians for their mode of speech when it is a carefully constructed mirror of the electorate’s imaginaire. And perhaps, in that sense, the ritual of election is working exactly as intended (one of The Onion’s best headlines once made this very point: “Petty, Shortsighted Americans Outraged by Legislature that Represents them Perfectly”). But is this a problem inherent to democracy? Or is it a problem with people? And is it really so wise to separate the two?

I don’t have answers to those questions—I really don’t—but what I do know is that somewhere between the release of Democracy 3 and Electioneering, Positech got a lot more sardonic about the whole endeavor of government by the people, for the people. Regrettably, the veneer of irony that covers Electioneering isn’t always flattering; Democracy 3 was never a game for idealists, but it did appear to celebrate, however tentatively and naïvely, the liberal democracy in spite of—and maybe even because of—its faults. Democracy 3 assumed, I think, that there is still some distance between cynicism and pragmatism, and that there is value in learning to live with the contradictions of democracy as we practice it today.

But Electioneering imagines democracy as if cynicism and pragmatism were the same thing. What’s at stake when we don’t think that distinction matters? I keep coming back to that request for a review and its maddening opening line: “With all the political madness currently engulfing us, isn’t it time for some clear direction?” Democracy 3 makes no claims about what “direction” is best; it is a game of effects, not of judgements. To wit, the game offers achievements for bringing into being societies as dissimilar and objectionable as technolibertarian dystopias to conservative theocracies. But, as far as I can see, the only “clear direction” Democracy 3 praises, the only feasible principle upon which to build a society, is the prime directive of incrementalism.

incrementalism is not a virtue; it’s a tactic, and not an especially virtuous one at that

Fine. So be it. But incrementalism is not a virtue; it’s a tactic, and not an especially virtuous one at that. When we lose the ability to distinguish the two, incrementalism quickly becomes something praised only for its own sake. And here’s the problem with that: not everyone can wait for change in increments—such a belief belongs solely to the privileged, those whom the status quo already serves. And so, in its tautological form, incrementalism ends up perpetuating the very inequalities it once sought to remedy. Is this the ideological statement Democracy 3 has been trying to make all along? Or are we simply witness to the failure of its designers’ political imaginations?

The latter, I think. Democracy 3 and its expansions offer very few ways of thinking about political change beyond familiar democratic avenues. Even the most radical ideas in Extremism are still firmly couched in the language of policy. What’s more, I think we should be very skeptical of any game that equates a punitive wealth tax with extremism. If that’s Democracy 3’s idea of “radical policy,” what would it make of the forceful seizure of the means of production? Or, for that matter, any form of political action outside of a narrow band of policies that, if not necessarily neoliberal-friendly, exist only in relationship to neoliberalism?

That’s not to say that Democracy 3 is devoid of direct political action; it’s just that direct action is something exclusively done to, not by, the player. One of the most-discussed aspects of the game is its fail states: the game ends either when you lose an election, or you get assassinated (!). And because it’s not particularly difficult to be reelected in perpetuity, the only real threat to the player is getting murdered by ideological zealots, and the only way to rouse the ire of ideological zealots is to enact widespread social change too quickly. Example: buoyed by the example of Switzerland, I attempted to implement something approaching a universal basic income for my citizens, a policy, mind you, that’s often praised as a compromise between the left and the right’s respective beliefs on how to grapple with poverty. But despite several pandering speeches intended to soothe the egos of free market fanatics, my plan resulted only in my ignominious assassination at the hands of some “well-funded capitalists.”

There’s a frustratingly low ceiling to the expressiveness of Democracy 3’s ruleset that’s particularly limiting when it comes to imagining alternative forms of political engagement. And that’s a major problem because the fundamental questions a game like Democracy 3 provokes— eternal questions about the balance of pragmatism and idealism, or the inability of democracies to ensure the same quality of freedom for all their citizens, etc.—are not questions whose answers can simply be found, but must literally be worked out. Because it may well be that, after a long debate, we collectively—or, if you prefer, democratically—come to the conclusion that a commitment to incremental change, despite its many limitations and risks and inequalities, is the only reliable tactic we have to move toward a more perfect union. Or maybe not! The point is that it’s a conclusion to be arrived at only through a consideration of every other possibility, the very possibilities Democracy 3’s mechanics are incapable of exploring, limiting us only to whatever exists within the event horizon of incrementalism.

There’s a frustratingly low ceiling to the expressiveness of Democracy 3’s ruleset

But there’s something even more sinister in Democracy 3’s dogmatic praise for the increment. No matter if you wish to do “good” or “ill” in Democracy 3, and regardless of what you think those terms signify, you can only do it slowly. And that, I think, is where the game falls short the most, in its belief that democracy can manage the “good” and “ill” in equal measure, that incrementalism is somehow symmetrical. But just as words are imbued with a greater power to harm than heal, liberal democracies, by design—game design—have recently shown themselves to be a lot more capable of damaging themselves than finding ways of repairing that damage. Democracy gave us the Brexit, but it’s hard to see how it can now save us from its consequences. In the United States, only 13 million people—about four percent of the population—have so far voted for Trump, but the visibility of the candidate will ensure Trumpism persists long after November, just as the student riots of May ‘68 helped depose Charles du Gaulle, but renewed Gaullism’s lease on French society.

None of this is to say, of course, that democracy isn’t a net positive; all things considered, I genuinely believe the ability to elect our leaders should be counted among human civilization’s better achievements. But Democracy 3 is an object lesson in the dangers of taking the liberal democracy as an incontestable ontology; this uncritical view prevents us from seeing and doing something about the faults that have, in time, emerged from its noble design. This was, after all, what an optimistic Fukuyama didn’t perceive when he wrote “The End of History?,” as the Berlin Wall came down and Turkey began petitioning to join the European Union. I’m sure the triumph of Western liberal democracy did have a certain air of inevitability in those halcyon days. But Fukuyama’s imagined threats to democracy, past and present, were all exterior (even today, Fukuyama believes the only credible threat to liberal democracy is Islamic extremism). It’s that kind assuredness that prevents us from seeing how our chosen form of political organization contains within it the means of its dissolution. And so, Democracy 3, like Fukuyama’s boldest claim, ends up withering in the harsh light given off of whatever histories are being made.

The post Democracy 3: Electioneering is a misguided publicity stunt appeared first on Kill Screen.

Inside dares you to escape

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

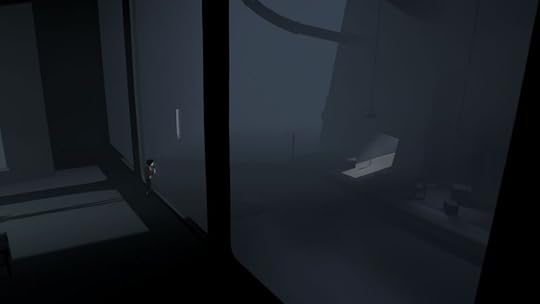

Inside (PC, Xbox One)

BY PLAYDEAD

Playdead appears to have taken some lessons from Limbo and the many emulators that came after it. Focusing on atmosphere and a mounting sense of dread, Inside is a journey into the grayness of the human condition under surveillance. You are a boy, you are hunted, you are observed, you are sacrificed, again and again. While more mechanically forgiving than its predecessor, Inside is cruel to its players in a way few other games have ever dared to be. The abuse, however, is less about puzzles and more about the player’s mental state. You will find no spiders or spikes here. But you will feel the tension constricting your chest as you tiptoe past the world with bated breath—awaiting capture.

Perfect for: Limbo fans, Narrative puzzlers, George Orwell

Playtime: 4 hours

The post Inside dares you to escape appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 7, 2016

An awkward game about touching a woman’s body explores sensuality

Just Feel is a project created by a team of seven students whose aim was to “mention sensuality and the pleasure in a poetic and subtle way.” Although I wouldn’t use the word subtle to describe the game, the goal was to “show sensuality without taboo and vulgarity.”

The experience is meant to be a virtual embodiment of caressing a body—more specifically, a female form. Delving into the concept of sensuality from an artistic angle, it appears the game is not concerned with any sort of social commentary. However, it’s hard to play this title and not feel conflicted.

an attempt to reduce the body to basic shapes

In the game, a bright neon handprint glides slowly across the length of a faceless woman’s stomach, creating colorful splotches across her skin that look like brush strokes. Once the pattern is completed, the paint lights up a few times before the camera pans to a different section of the body, instructing you to begin your journey over what you later find out is her breast. In an attempt to reduce the body to basic shapes, or perhaps in service of their goal to approach pleasure without vulgarity, there is no nipple.

You follow swirled dots that mark where your hand is supposed to travel, and are offered various shades of blues and purples. Soft music plays while you explore. It’s almost reminiscent of tagging a wall with graffiti before moving on to other parts of the concrete canvas, except your hand print is the graffiti and her body is the canvas. It’s hard to tell where exactly on the body you are at some points during navigation. The game ends suddenly: you may be sliding your virtual hands in between the faceless woman’s legs, and the game slowly fades to black without warning.

The experience is meant to be a virtual embodiment of caressing a body

The whole experience takes roughly 10 minutes. Although it is artistic and the color palette is visually appealing, the subject matter leaves behind some thoughts to be considered. Just Feel chose a beautiful female form as opposed to a male, yet society has conditioned us to view these bodies sexually, and so that design choice ends up seeming counter-intuitive. The mechanic of using a hand to facilitate the study of a woman’s body also doesn’t serve as a perspective that communicates the subject as a person, but rather a shape that is a vessel for exploitation. While you may feel awkward exploring this body, the one thing that might really pull you out of the experience is seeing the Barbie version of her crotch.

You can download Just Feel over on itch.io.

The post An awkward game about touching a woman’s body explores sensuality appeared first on Kill Screen.

Deep Space is a soundtrack to a videogame that doesn’t exist

Bad news: Deep Space is a game you will never play. It doesn’t exist except as an implication. It’s the invented backstory for a new record by Joel Williams (also of Wavves-affiliated acts Sweet Valley and Spirit Club).

Under the name Kynan, Williams wrote the soundtrack to an imaginary game, which he describes as a “surreal shoot-em-up” in the vein of 1986’s Fantasy Zone. In the end—presumably around track 17, “Self Inflicted Wound Game Over”—you end up destroying the planet in your efforts to eradicate “mutated demon aliens.” The lead track, “Deep Impact,” throbs with huge clanging beats and plaintive synth arpeggios. “Contamination” has grainy washes of sound that nod to Italian prog outfit Goblin’s early-80s soundtracks, including their score for the 1980 Alien ripoff … Contamination.

captures the propulsive, one-more-quarter vibe

The record becomes more cavernous as it goes along, detuned, distorted basslines, and stuttering drums roaring into an abyssal din. It doesn’t sound like music from 1986, pulling as it does from the modern aesthetics of Arca and the like, but it captures the propulsive, one-more-quarter vibe of its inspirations nicely.

Deep Space is instrumental, but you can glean a rough narrative from the track titles, the PS1 Greatest Hits-style cover art, and the brief teaser that Ghost Ramp label manager Patrick McDermott and Williams put together. “I wrote it all on a train ride after I had badly injured my hand,” said Williams of the project’s genesis. “It sounded like mood music for something in space.” See for yourself by streaming the album on SoundCloud.

You can purchase Deep Space in CD-ROM form for $10 right here.

The post Deep Space is a soundtrack to a videogame that doesn’t exist appeared first on Kill Screen.

Videogames and the Art of Deception

The visual arts have a rich history of deception. Every painting that attempts to condense the world into two dimensions exploits flaws in the way our eyes work, fooling us into perceiving depth and distance through the use of vanishing points and skewed proportions. Optical illusions trick us into seeing differences in color that don’t exist, while portraits painted to look straight ahead seem to follow us as we walk past.

The advent of film and TV pushed the art of deception even further. Green screens convince us that the hero truly is dangling from the lip of a 60-storey skyscraper. Wire-fu, or the use of invisible wires to suspend actors in the air, allows punches and kicks to seemingly pack superhuman strength. And many of cinema’s greatest chase sequences only seem so frenetic because they were filmed slow then sped up in editing.

For as crafty as these techniques are, they simply laid the groundwork for the master of illusive media: videogames. In addition to packing the same tricks as movies and paintings, games are capable of entirely unique forms of deception that not only make their worlds feel more real, but highlight a level of ingenuity that rarely receives the praise it deserves.

games are capable of entirely unique forms of deception

Foremost among these deceptions is the illusion of virtual geography. Videogame worlds are typically too large to be loaded into a computer or console’s memory all at once. Instead, they are split into smaller chunks and streamed in on demand. This technique was especially common during the early days of 3D technology, when developers had to fight the hardware for every last polygon.

The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998) provides a great example. Scattered across the world of Hyrule are numerous holes Link can jump into, each of which leads to a small cave with various treasures to collect. Since the Nintendo 64 suffered from significant memory constraints, these caves could not be loaded into memory at the same time as the rest of Hyrule, and were instead lumped together on a separate map. When Link enters one of the caves, Hyrule is unloaded from memory and the cave map is swapped in.

While this allowed the humble N64 to support one of the largest virtual worlds of the time, it also paved the way for dedicated players to turn the deception back on the game. With a deft hand, Link can glitch through a cave’s walls and into the space beyond. There, the other caves stretch out like islands in a sea of black emptiness. By walking across the void to one of those caves, the player can trick the game into teleporting them back into Hyrule at a different spot to where they left it. Known as the Wrong Warp Glitch, speedrunners have used this technique to beat the game in mere minutes.

Despite the many advances of modern technology, today’s games still rely on deception to build their worlds. Fallout 3 (2008), for instance, pulls a fast one when shuttling players around its Metro rail system. Introduced in the game’s Broken Steel DLC, the game’s creators faced a big problem: Fallout 3‘s game engine had not been designed to support moving vehicles. Rather than completely rewrite the engine, then, the developers decided to get crafty. When the player flips the switch to start the train, the game briefly fades to white and equips the player character with what is effectively a train wristband. What ensues is a Flinstones-esque facade where the player character physically runs along the tracks beneath the train, dragging it with them, while the camera remains fixed inside the carriage. The whole sham is executed so perfectly, the player never suspects a thing.

Perhaps the most vital trick games pull on us is asset reuse. Where cartoons often loop background art and recycle animations to save time and money, games have the additional concern of minimizing the space they take up in memory and on disc. The original Super Mario Bros. (1985), for example, had to contend with the measly 2 KB of RAM available on the NES—for reference, the text of this article alone takes up over double that on today’s computers. To get around this limitation, Nintendo reduced the game’s art into small tiles that could be copied and combined on-the-fly to create entire levels.

Deception continues to course through the veins of videogames

This facilitated some clever sleight of hand: see those bushes Mario is running past? They’re just clouds colored green. Take a look at Luigi. He’s just Mario with a green top and white overalls. And the good ol’ Goomba? Not only was it the last enemy to be added to the game, there were so few bytes left that the developers could only afford two frames of animation. Goombas flip between these two mirror images to give the illusion of waddling. For a last-minute hack, the Goomba has done a bang-up job of introducing millions of players to the world of Mario.

Deception continues to course through the veins of videogames to this day. The recent global phenomenon that is Overwatch hides its trickiness right in plain sight. To emphasize the speed and power of its heroes, character animations do not stick to the laws of physics: when Pharah jumps, her head moves slower than the rest of her body, giving the illusion that her body is made of elastic; and when McRee reaches for his revolver, his arm turns temporarily boneless and whips across his chest with the swiftness of a cobra strike.

These animations look horrifying when slowed down, but in regular play, they occur too fast for our conscious minds to register. They don’t need to be noticed to have the desired effect, though. As part of Blizzard’s ‘squash and stretch’ approach to animation, the rubbery limbs lend a springiness to the characters that makes their actions feel smoother and more powerful. It’s a sly way of capturing the heroes’ superhuman nature without coming off as too cartoony or unrealistic. A talking gorilla we can accept, but a DJ with foot-long fingers might be a bit much.

The art of deception is a vital component of videogames. It lets us suspend our regular lives and escape into worlds that feel just as real and dynamic, even when they’re just crude simulacrums at their core. We want games to lie to us because the lie is more entertaining than the truth. Like fad diets and billion-dollar lotteries, we want to believe the fantasy can be real.

Header image via Gabriel Rojas Hruska

The post Videogames and the Art of Deception appeared first on Kill Screen.

Get ready for more gay sci-fi adventures in your videogames

The creator of the incredibly named My Ex-Boyfriend the Space Tyrant is currently funding a follow-up: Escape From Pleasure Planet.

Escape from Pleasure Planet follows the story of Captain Tycho Minogue as he battles the devilish (and dangerously handsome) criminal Brutus, who he must track down. For Luke Miller, the creator of these gay-themed science-fiction adventure games, there was an easy connection to be made between the nature of both narratives.

wants to touch on issues relating to the gay community

“I was looking for gay and science fiction themes that were complementary to each other,” Miller says. “In the gay community there’s often hedonism combined with repression. The kid from the small country town often goes most wild when he moves to the city. In sci-fi there’s often a utopian world with its own terrible secret. Combining the two was an ‘aha!’ moment and I think the twin threads provide a fresh take on each other.”

Aside from the classic science fiction pulp that informs Escape from Pleasure Planet, there’s also a clear thread from adventure games like Day of the Tentacle (1993). Players will interact with 30 worlds and many different characters throughout the grander universe. The game promises to have a diverse cast of characters—it is gay-themed and wants to touch on issues relating to the gay community after all. Escape from Pleasure Planet is just hitting the topic through the lens of Venus flytrap-like planets and attractive space criminals.

You can find out more about the crowdfunding for Escape From Pleasure Planet at its Kickstarter page.

The post Get ready for more gay sci-fi adventures in your videogames appeared first on Kill Screen.

Uncover the secrets of household objects in a new puzzle game

In a previous life, There You Go would’ve been a sleeper hit on a flash portal website, where lots of different creators submitted games and animations to test out new ideas, or to show off what they could do. It feels like it has a lot in common with puzzles that were popular back then, halfway between something like the GROW series of games and an escape-the-room puzzle. Now, it’s on itch.io, and it’s the first game from Octogear, the studio name of solo developer Evyatar Amitay.

the spaces are as simple and sparse as they can be

For the most part, There You Go is a cute little game about exploring a set of cube-shaped rooms—about 10—and puzzling your way through them. The solutions require a bit of lateral thinking, but not a ton. It’s only about 10 or 15 minutes of clicking on objects, but definitely more than that if you enjoy, as I did, spinning the rooms with their shifting walls, and the very satisfying clicking sound when you interact with the household appliances.

Even though the spaces are as simple and sparse as they can be, made mostly with voxels, the soft lighting gives the place a homey feeling, and those clicks when you make something important happen feel just right. The game is so tightly put together that almost everything you can click is important, although Amitay points out that there are a few easter eggs—my favorite is the painting that tells you, “I should probably do something.”

There You Go also has an interesting design quirk in the form of randomly generated puzzle solutions, which I only know because I’ve played through more than once. They’re the same key-code puzzles, but the codes are switched up every time, meaning your time with the game is going to be just that little bit different from someone else’s.

You can download There You Go over on itch.io.

The post Uncover the secrets of household objects in a new puzzle game appeared first on Kill Screen.

Death’s Gambit enters the contest for the biggest videogame bosses

In 2014, game studio White Rabbit revealed what was perhaps the defining image of its upcoming fantasy action game Death’s Gambit: your mounted hero scaling the body of a gargantuan being, so massive that it loomed over the surrounding mountain range.

It was clear then that while the sword-and-shield combat and gloomy fantasy world was influenced by titles such as Dark Souls (2011) and the Castlevania series, the legacy of Shadow of the Colossus (2005) also—and perhaps most prominently—lived on in Death Gambit’s towering bosses. That point is only nailed home with the release of the game’s most recent trailer, 90 seconds of pixel-art combat and exploration that shines a spotlight on its colossal bosses and fearsome foes.

While Death’s Gambit may be confined to a 2D plane, the scale of its action and landscapes are striking. From the stone dragon monument arching over sunlit peaks at the start of the footage to the sword-wielding behemoth so large that its head extends beyond the screen, Death’s Gambit pits the player against overwhelming odds, enforcing the tense stakes of your encounters. It very much fulfills that heroic fantasy that special effects crews are forced to return to with every summer blockbuster—the latest iteration of the ancient Bible story, David and Goliath, in which the underdog overcomes their impossible foe with wit and determination.

monstrous abominations lurk, feeding on dead flesh

Death’s Gambit contrasts this huge scale through action on the opposite end of the spectrum. As the player traverses the grisly confines of blood-drenched sewers and shadow-cloaked ruins, monstrous abominations lurk, feeding on dead flesh. They, too, appear to dwarf your protagonist, but this time it’s more through sheer fright rather than huge scale.

Death’s Gambit will be releasing on PC and PS4 in 2017. For more details, visit White Rabbit’s Tumblr blog and Twitter page .

[image error]

The post Death’s Gambit enters the contest for the biggest videogame bosses appeared first on Kill Screen.

Brigador and the joy of total war

In late 1864, the American Civil War had come to a decisive point. The Confederacy’s efforts to bring the war to the North had been effectively routed in the previous year, and the South was forced to take the defensive on its home ground. Ulysses E. Grant, General of the Union Army, sought a way to break the South with minimal loss of life. He found his earth-scorching muse in William Tecumseh Sherman, who proposed a simple strategy that proved to be devastatingly effective. Sherman would have his forces march south through Georgia, and where commanders met with anything less than full cooperation, their orders were to “enforce a devastation more or less relentless according to the measure of such hostility.”

Although the Union Army didn’t target civilians, everything else was fair game: “mills, houses, cotton-gins, &c.” Sherman’s “March to the Sea,” as it has come to be known, accomplished just what he promised: it demoralized the South, and left their infrastructure in tatters for years to come. But Sherman took no joy from his victory. In a speech to soldiers high on the fumes of destruction, he cautioned them against confusing military necessity with moral triumph: “There is many a boy here today who looks on war as all glory, but, boys, it is all hell.”

Brigador has little use for such hand-wringing. It plunges you into the middle of a different civil war, and gives you only one objective: blow shit up. Each of the 21 campaign missions—all of which have their own maps and distinctive, throbbing EDM scores—gives you a specified list of targets to destroy, but as the game likes to remind you, nothing is out of bounds. From the vantage point of your mech or tank or modified shortbus, you are free to “enforce a devastation more or less relentless” as the mood takes you. Need to get to the other side of that apartment complex? Steer right through it. Don’t like the way that statue is looking at you? Blast it with your double lasers, and call it a day. The more damage you incur, the more money you accrue; it’s a futuristic mercenary’s dream come true.

That the game gives almost no thought at all to the human cost of this destruction could be troubling. But Brigador doesn’t buy into the perfidious morality of this year’s The Division or Homefront: The Revolution, whose mistake is to present their violence as justice; this game is quite clear about its amorality from the beginning. You, the citizen of futuristic space colony Solo Nobre, are a contract soldier working for the Solo Nobre Concern (SNC). You earn money by destroying things, and your in-game reward is to buy more stuff to destroy more things. There’s no question of motivation or allegiance, except to the extent your contract requires it. It may be unethical—but at least it’s honest.

Meanwhile, there is a whole constellation of political intrigue surrounding you. The game’s plot deals with the death of Solo Nobre’s Mao-ish “Great Leader” and various factional efforts to usurp his power. But although the differences between these factions are strategically clear —sometimes you fight the loyalists, sometimes the separatists—the game seems uninterested in vilifying or vindicating any of the parties involved. To the extent it considers the populace at all, it is with an almost comic indifference: “Nobreans are proving more resistant to the present SNC restructuring than expected,” you are told in one mission briefing. The solution, in this case, is to destroy four statues of the Great Leader to demoralize his supporters. And elsewhere: “Though the SNC disagrees with the late Leader’s plans for the future of Solo Nobre, his blacklist is remarkably close to our own.” War can be convenient, if everyone wants the same people dead.

It may be unethical—but at least it’s honest

The delightful irony of Brigador is that for all the focus on conflict, actually succeeding in these missions usually requires you to forsake your appetite for destruction. You can destroy everything, but some of those things have a nasty habit of blowing up in your face, terminating what might have been a grueling half-hour crawl across the map. Since there is no saving within a mission, and ammo is limited, you quickly learn that it is safer to only destroy what you need to. And even that can be quite a challenge. Brigador isn’t a particularly complex game, but it is an exacting one, and it forces you to have an almost flawless command of each of the three different control schemes (which apply to three different types of vehicles) to get through the campaign.

If the game’s backstory feels somewhat undercooked, it is distinguished by this precise attention to the details of combat. Not only are there different control schemes and vehicle types, but there are numerous shapes and sizes within each type, all with distinctive sets of weaponry. Since different maps require different kinds of approaches—some are closer to stealth missions, while others are inevitably full-screen shootouts—much of the game’s considerable challenge lies in figuring out which of the four available vehicles are the best for a given mission. And bigger isn’t always better. The game’s most memorable hurdle comes in a level appropriately called “Joy Bus / Hell Ride,” which requires you to guide the speediest available mech from one end of the level to the other and back without ammo as waves of kamikaze attackers fly at you from all sides. In moments like this, the game completely transcends its native mentality—blow shit up—to become an almost balletic negotiation of speed and place.

At a basic aesthetic level, the game is also a treat. Each of the 42 maps were hand-drawn by the small team at Stellar Jockeys, and the work shows. Nightclubs and business hubs pulse with light and flavor, while the sprawling neighborhoods of suburbia feel appropriately placid and ripe for upheaval; there’s no better way to work out suburban ennui than to drive a minibus through a goalpost. And the game’s soundtrack, by Makeup and Vanity Set, provides an immaculately glossy accompaniment to this colorful world. In a different kind of game, Solo Nobre’s atmosphere might have been a rewarding one to live in and explore for its own sake. One yearns to dip into the nightclubs, and peek in the windows of those loyalist townhouses. But such is Brigador’s bent that all this beauty is there to be demolished. If the game has any message, it’s that the only thing more rewarding than admiring a lovely cathedral is watching it explode. War may, as Sherman said, be hell—but it is also a hell of a spectacle.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Brigador and the joy of total war appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 6, 2016

IT Simulator aims to bring absurdity to a boring job

Rebecca Cordingley is a 28-year-old English expat who recently quit her job as art director for Schell Games to pursue her own projects. Her upcoming solo debut, IT Simulator, promises a simulation brimming with “frenzied physical humor” and minigames involving IT tasks like defragmenting hard drives, ridding browsers of pop-up infestations, and buying office upgrades in the role of manager.

“I’ve always loved playing videogames, but I didn’t always know that I wanted to make them,” says Cordingley. “I dabbled in a lot of interactive projects when I worked at a design agency, and that slowly turned into a focus on game development. Despite being on the visual side of the games industry, I’ve been learning how to program for quite a few years now.”

“I love the colorful whimsy and aesthetics of games”

Even though she worked on marketing materials, mobile ports, and localization for games like Enemy Mind (2014) and Orion Trail (2015), Cordingley’s formal education background is in graphic design. “I love the colorful whimsy and aesthetics of games like The Wind Waker (2002), Jet Set Radio (2000), and Viewtiful Joe (2003). But I’m influenced a lot by what sort of systems I like to code,” she says. “I’ve had a lot of fun writing the AI for the characters in IT Simulator.”

She also cites this year’s Stardew Valley as a key inspiration—a very recent example of how a single developer could make something interesting and polished, yet also personal, and go on to earn a wide audience. “[That] gave me a lot of courage to go off on my own.”

Cordingley says she’s never worked in the IT industry herself, but hopes that’ll allow for a more absurdly imaginative take on what is, in reality, probably a fairly mundane job. “In terms of games with serious themes that deal with aspects of society or life, IT Simulator isn’t really in the running,” she admits. “It’s probably as much a reflection on contemporary work culture as Goat Simulator (2014) is a reflection on goat culture.”

The game is still in the early stages, but Cordingley hopes to launch on both Kickstarter and Steam Greenlight simultaneously once there’s enough community interest in the project. She has already been approached by a couple publishers, but she’s keeping her options open in the meantime.

Follow Rebecca Cordingley and IT Simulator on Twitter for regular progress updates and screenshots.

The post IT Simulator aims to bring absurdity to a boring job appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers