Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 99

June 28, 2016

The greatest Famicom-based game jam returns this week

What do you get when you combine the world of fake Famicom case cover art and game jams? The “A Game By Its Cover” jam, actually, which is making its triumphant return on June 30th.

Being the Japanese precursor to the NES, the distinctive red-and-white Famicom has a great deal of nostalgic power over people who grew up in the early 80s—even if it doesn’t closely resemble the American, VCR-looking version of the console. The A Game By Its Cover Jam sorta banks on that. It encourages game makers to spend a month creating games based on faux Famicom cover fan art.

a Famicase for every gaming persuasion

The premise brings these Famicase games to life, as if from an alternative dimension to the NES. From the bold-flavored, Guy Fieri-themed “Cooking Daddy” to the brewery-themed adventure game “Hoppy Hops,” there are plenty of possibilities. With over 10 years of potential fan cases to use, there seems to be a Famicase for every gaming persuasion. This ranges from the comedic (again, see “Cooking Daddy”), to earnest 16-bit riffs like last year’s entries Morning Star Girls and Every Sport Ever in Pong Form. In 2012, the jam was a competition and helped inspire such works as Tales of Unspoken World, which later went on to become the first-person runner Fotonica.

In the spirit of creation, the only rule is that there are no rules. Participation in the month-long jam can start before the jam begins, participants can work on teams or on their own, and the games don’t even need to be based on the awesome cover art of Famicase. But with the years of Famicom-inspired-goodness, it’s a bit difficult to resist.

The jam, which starts June 30th and runs through August 1st, is already live on itch.io, so anyone interested can explore the community and potential Famicase covers.

The post The greatest Famicom-based game jam returns this week appeared first on Kill Screen.

Learn how to rotoscope with Paint of Persia, a new animation tool

Before motion capture was a thing, there was rotoscoping. Sure, it’s wasn’t quite as entertaining as strapping middle-aged actors into black bodysuits studded with various balls and gizmos, but it was a versatile technique that’s been used in everything from Disney movies to the music video for “Yellow Submarine.”

Invented by Max Fleischer and put to use largely in his 1940s Superman serials, the technique involves filming live-action footage and then tracing over it to create animated characters with realistic movement. It was originally a bit of a painstaking process, with artists having to project live-action scenes onto a frozen glass panel through a device called a rotoscope—hence the name—and then redraw them, from scratch, by hand. But modern tools have made the technique easier and more available to the general public.

Eventually, this allowed it to catch on in videogames as well, as titles like Prince of Persia (1989) and Another World (1991) sought to use it to have players move about their worlds with the same weight and detail as an actual human being. Now, there’s Paint of Persia, a tool that allows everyone and anyone to experiment with rotoscoping in a way that’s as easy as using Microsoft Paint.

Developed by game developer dunin, Paint of Persia works by allowing users to upload still images or video footage, and then overlay animation panels on top of it, upon which they can trace pixel art. Users can then adjust scale, transparency, background color, animation footage, frame rates, and more—similar to professional animation programs like Adobe Flash or ToonBoom.

Additionally, they can also use the program to make still pixel art images. Dunin has even used the program himself to create a game called Anthropomorphic Subject, a match-3 game about trying to find the correct suspect in a police line-up. In the game, the player must follow the instructions of an unreliable old woman to combine various animal body parts to try to match her recollection of a thief. There’s an almost Papers, Please (2013) sensibility of mundane work and unreliable authoritarian control to it, all of which is possible through how the rotoscoping has allowed dunin to bring realistic animal body parts into a surreal anthropomorphized environment.

it allows one to bring real footage into the surreal

This points to the strengths of rotoscoping as a whole. While some have criticized it for skirting the uncanny valley—a term for the point in between the abstract and realistic that tends to frighten viewers—as well as for limiting the many possibilities of animation to the physics of the real world, when used effectively, the technique does not drag down animation so much as it allows one to bring real footage into the surreal.

Like how films such as Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988) or Cool World (1992) combine animation with live-action footage—which is also possible with Paint of Persia—rotoscoping allows one to transfer live-action movement into a world populated by whatever the animator’s mind can think of. Sure, they might be limited to the movements of an actor, but those movements can than be put into, say, a candy cane world, or a sci-fi drama, or a Dali -esque dreamscape. In the 1940s, when Fleischer was working, this was an especially cost-effective way to create impressive special effects without worrying about the practical necessities of live-action filming.

Paint of Persia is available for free over on dunin’s itch.io, where he has gone through the courtesy of using the program to recreate scenes from the original Prince of Persia on top of a live-action background. He has also rotoscoped scenes from 1913 French crime serial Fantômasto to demonstrate how the pixel art blends with live action. The program also makes for a strong introduction to the basics of animation, allowing new animators to learn using live-action footage rather than having to work from scratch. As someone who’s been interested in animation for a while, but who cannot draw with more sensibility than a 5th grader creating Sonic fan art, I know that I appreciate the ease with which it allows me to toy with, and maybe begin using, the art form.

You can learn more about Paint of Persia over on its itch.io page, and can follow dunin on Twitter.

The post Learn how to rotoscope with Paint of Persia, a new animation tool appeared first on Kill Screen.

The story is in the details: A chat with Fullbright’s Nina Freeman and Karla Zimonja

This article is part of Issue 8.5, a digital zine available to Kill Screen’s print subscribers. Read more about it here and get a copy yourself by subscribing to our soon-to-be-relaunched print magazine.

///

Fullbright are best known for 2013’s iconic Gone Home. Their particular niche, now being refined with their upcoming Tacoma, is the narrative videogame: an intimate, carefully designed space left for the player to explore and unravel. Nina Freeman, creator of 2015’s Cibele, joined Fullbright last year as a level designer. Karla Zimonja co-founded the studio with Steve Gaynor. We sat down with them in their Portland office and talked about the benefits of working with a small team, trusting the player, and that pesky “woman in games” question.

KS: Nina, what was it about Fullbright that you felt drawn to?

N: I showed Steve Cibele really early on and he gave me a lot of feedback before I even had any idea that I would be working here. We kept in contact because of that and he invited me up here [to Portland] and I interviewed with them. It was basically like, what’s the equivalent of love at first sight but for a job? It was refreshing to meet a bunch of people that are excited about the things I was and to be at a company that’s a lot smaller, because I was feeling burnt out on larger companies. I always love working on smaller teams and feeling like I have agency over what I’m working on and like I can see my impact on the projects. Here I have a lot of ownership over my work while also being really collaborative.

KS: Karla, what were your initial conversations with Steve when you were looking to form Fullbright?

K: Initially we worked together at 2K Marin and that was a luck of the draw thing in a lot of ways. We were both people who wanted to continue working on [the Minerva’s Den] DLC on BioShock 2 (2010) instead of moving on to the next project. We started working together in the way we do now which is collaborating on story stuff, Steve doing the writing and then a back and forth with editing passes and stuff like that. Like Nina was saying, it was an example of a small team within a larger structure, and it was a tight-knit little group where you got to make a lot of difference to the project yourself. Then Steve went off to work on BioShock: Infinite (2013) and when he was finished with his part of that he called me up and was like do you want to move back to Portland with us and make something? I said sure; it was a time in my life where I could pick up and leave.

We all moved into a house together. It was us and we had a programmer and after a few months got Kate our environment artist. We didn’t plan very well to begin with. We didn’t understand the extent. There’s something about embarking on a project that’s super shoestring in the basement of a house in Northeast Portland that doesn’t lend itself to official thought to what you’re doing. It’s easier when there’s only a few people to fight for what you want. It’s not like we sat down and thought out a motto or anything.

KS: Do you think that level of organically being on the same page has remained as you’ve grown?

K: We’ve tried to make it so. Since we have not grown super large I think if we were to get much bigger it would start becoming much more difficult to maintain the dynamic because you start to have more management. The overhead gets larger and that’s less great. So we try to stay little so we can not have so much time spent on infrastructure.

KS: Cibele and Gone Home are very personal, almost poetic, and blend mechanics and narrative in a way that is very specific to games as an art form. How did this come into your work and is this an important element for you?

N: It’s funny because coming from having done poetry for a long time writing about ordinary life and my experiences is the norm. I think stories about ordinary life are the most interesting because naturally as people you go to the bar and want to gossip with your friends about something, you gravitate towards telling ordinary stories when you talk to other people.

K: Like Nina was saying, it’s more native to our thinking to comprehend human-scale things. Not only that but you can’t make a story in which all the things in it are generic and applicable to everyone. Paradoxically, we have found the more specific you get the more people relate to it, and that’s because we’re very good at generalizing, good at hearing someone else’s story and being like that makes me think of when I felt something like this.

N: The human stories are the best parts of those large-scale games, too.

KS: What do you find people connect to most in your games?

N: People like to see themselves in things and I can’t tell you how many emails I’ve gotten from people who are like “I was in an online relationship too!” or “My friend dated someone just like this.” People, like Karla said earlier, like to find that, relatable is a word I hate using, but relatable stuff that reminds them of something they’ve actually experienced. It’s meaningful to be able to ground a story within the context of your own life and also to be aware that it’s not entirely about you, that it’s about this character you can relate to and the game is showing you another kind of experience. I think people have been drawn to Cibele for a variety of reasons, but validation is one.

It’s hard to make something cross audience boundaries if you don’t have set dressing

K: With Gone Home, it’s a relatively small personal story. It’s not hard to relate to your parents not getting you or thinking you’re not in control of yourself. I feel like both of us lucked out in that we make games that are relatively accessible and visually polished and distinct whereas obviously there have been a lot of personal games made before and maybe those people didn’t have as many resources as we did and were not able to make it look as fancy. In some ways I think we got in early enough and put a fancy layer on it. It’s hard to make something cross audience boundaries if you don’t have set dressing and not everybody has those resources.

KS: Do you feel it was lucky it crossed audience boundaries?

N: I think it was timing, because nobody had seen anything like Gone Home when it came out that had a BioShock level of polish but without the gamey stuff. It presented itself in a different way at the right time because there wasn’t something like that that had gotten that visibility.

K: I feel like The Stanley Parable (2013) was the only vaguely comparable thing because it was around the same time and used the trappings of another game. But yeah, honestly timing, you start making a game when you can and finish it when you can. I’m sure a lot of people plan a release but we didn’t do it, we weren’t together enough, we hadn’t done market research and thought things would align.

KS: Do you think that these specific games paving the way for everyone else is sort of the natural evolution of games?

N: I feel like, yes. Influences trickle down and become dispersed. So obviously Gone Home had a lot of influences from games that were kind of doing similar things and I was influenced by Gone Home in Cibele, and these trends pick up speed because I think people like playing games that don’t just tell them the story but they put the pieces together themselves.

K: It’s an ecosystem, you make a new niche or path available and everyone goes oh, we can use that?! It’s nice to be able to share ways of doing things that’s interesting. It’s nice when people have more tools to get stuff made they want to make. There’s something to be said for the idea of the player pulling the knowledge that they want rather than it being pushed to them. I think that helps both of us in a lot of ways because it allows for people to set their own pace.

KS: So understanding is a priority in development?

K: For me, yes. And it’s not just understanding but allowing the player to do the understanding. You can say look, I can play you voiceover that tells you what you need to understand, or I can let you put the pieces together yourself and you can connect the dots and that will be more fun. Learning is fun and figuring things out is fun. I love using that tactic to help people understand the world and characters, it’s really satisfying to give them the tools to understand things.

N: I think the commonality is telling the story through the details and the way those details fit together almost like a puzzle. In Gone Home and Cibele it is about specific people and you’re learning about the specific lives of these people. There’s embodiment in both in that you’re playing a player character who is not you and you’re coming to understand both the story of the world and the story of the player character.

K: You have to be curious enough to dig around in it. The player’s curiosity is the thing that draws them from object to object and moment to moment.

I don’t want to be known as a female game developer but I want my games to be known

N: The other day someone tweeted they wanted to see if they could play the game without looking at all the desktops, which you can, and I was like yes someone noticed! It’s player-driven narrative, they choose to make the connections themselves and which parts of the game they want to see. Everything is here for them to engage with it. That mechanic is totally drawn from what Gone Home did. In Cibele, it’s basically Gone Home but on a little computer.

K: I think it’s not just show rather than tell, it is pull the showing rather than push the showing. I’m not serving you this cutscene, you’re taking this information to yourself.

KS: Generally as a creator what are things you have in the back of your mind or things you see coming up again and again?

N: Cibele was heavily influenced by a lot of things. Obviously Gone Home mechanically influenced it a lot. The story is based on my own life so there’s that, but Lost in Translation (2003) is basically the structure of the game. Cibele has the same basic plot where it’s about two people who meet and have this brief romance and the end is them just leaving each other and there’s not much closure. There are shots from the short films in Cibele that are taken from that movie, so that was a pretty heavy influence. Also The Virgin Suicides (1999). I like [Sofia] Coppola’s character stuff especially because she does a lot of shots where characters don’t say anything in a way that I think is cool. So I looked into those films.

Also Grimes’s music video, that really cool one that she made where they were all dressed up as warriors. That was the music video that the artist and I sat down and watched when she was like “what aesthetic do you want, what color palette do you want?” And all the poetry influences I have, obviously. I learned how to write from a poet so I can’t ever escape those influences now, forever my writing is influenced by it, specifically by the New York School era of poets. John Ashbery, Charles North who was my professor and mentor, these are all the New York-based poets who were writing in the 70s and 80s and wrote very concrete poetry about ordinary life. Ted Berrigan would write poems about getting high and what he would be eating, very based in mundane everyday stuff. Those were my primary influences for Cibele and also things I think about a lot as a storyteller.

K: I feel like I don’t get asked influences or stuff like that often.

N: I rarely get asked it either.

K: It’s not a common videogame question at all.

KS: I’m sure you get asked about this, so do you think it’s bullshit that as female game developers you’re asked to be arbiters and representatives of not only our gender but all female game developers?

N: In the aftermath of Cibele I was doing a lot of interviews and this came up in every single one. “What’s it like to be a female game developer? It must suck a lot.” I was like, I’m the wrong person to ask, because I’ve always worked on tiny teams with friends and then I came here and I knew that I was coming into an environment that would be a positive space. I’ve always been in a position where I haven’t had to work with anybody that I’m uncomfortable around, so I’m always the wrong person to ask because I’ve never had a bad experience.

When I first started making games my boyfriend also made games so sometimes I felt like people would look at me and be like oh she’s just doing this because of him, but that stopped happening pretty fast when I actually started making stuff. It’s annoying but it’s also fine because I get to give my answer which I’ve developed over time. I always say that my goal is to change the conversation around my work at least, I don’t want to be known as a female game developer but I want my games to be known.

KS: It’s still a way of pigeonholing women.

N: Exactly. For me changing the conversation about how I work on games is more important because there are plenty of women making games, but usually they’re only talked to in terms of this issue when they should be asked about –

K: Anything else!

N: – right, so I take that question and I’m like, it’s fine that you’re asking me but I’m going to tell you to ask about their work instead because that’s going to be more helpful. The biggest issue is none of us can talk about our work, we can only talk about our gender. I obviously have gained enough visibility that I don’t have to talk about that as much anymore because I’ve worked really hard to change the conversation around the stuff that I work on, so it comes up a lot less often than I used to. But it takes a fuckton of interviews to get to that point. It sucks but you just have to work hard to make sure the focus is on your work and not you as a person, because it’s still about the games. It’s not about me, it’s about the games that I make.

I learned to shout over people in conversations because dudes do that a lot

K: Firstly, it’s meaningless to ask someone what it’s like being them. I only have my own perspective. How can I tell you what it’s like to be me? It doesn’t mean anything. And also Fullbright is very white. We are not the frontier here. We have more work to do in that regard. I am lucky enough to be co-owner of a studio that is more than 50 percent women but that is because we did that on purpose. Back on Gone Home I was like we’re half and half, we should keep this ratio if we can and I was actually kind of worried about it, when we started hiring people I was like how are we going to keep this ratio? Because women tend to leave the game industry. We were lucky enough to find a lot of really good people. But we did actually have to do that on purpose.

KS: What are the benefits that have come from maintaining that ratio?

K: It’s always good to have more perspectives present because then you don’t end up your own ass as much. If you think something is a default, maybe someone else doesn’t, and that is a chance for you to not make the same choice that everyone would make and make something different. There’s a lot of people that don’t get to have a say when they’re making things and we’re lucky enough to be able to allow our people to actually influence the stuff that we’re making. That makes everybody’s work better. It’s simple.

N: I was in the startup scene in New York and I was on a team that was almost all dudes but they were working hard to hire more women. When I was at Kickstarter the conversation was “How do we get more women?” and thinking about that all the time is stressful. If you’re on a team of all men and they want to do that, it’s good, but it’s stressful to be the only woman in the room in this situation.

K: Because everyone looks at you and goes how do we do it, how do we get a woman?!

N: You’re the one point person on that sort of thing. I’m not that anymore which is really relieving. I can actually think about things other than activism and stuff, and I used to be way more involved but I’ve have moved away from it because I noticed that being involved in it made my work be about that. Since I’ve moved here and since working on Cibele my main focus is just making stuff. I feel like I’m at a point in my career where I want to focus on becoming a better game designer and that’s more important to me than anything else. And there’s people who do [activism] really well, who make that their job, and I’m like thank you. I can go do my thing and that’s totally okay.

K: I remember when I was in Triple-A I could see myself learning bad habits because dudes would do things and you’d have to react to work in that system. I learned to shout over people in conversations because dudes do that a lot, and you have to learn to interrupt right back or you don’t get to speak. So for the past five years I’ve been trying to unlearn that because it’s not cool, but I had to do that at work. And just thinking how we don’t have that environment now because we’re shaping it more intentionally and that’s not our company culture. It’s so good and gratifying, I’m sure we’re falling down in some other way but it’s really nice to be able to talk to each other and not have bad conversations.

N: Everybody gets their word in even if they’re not directly working on it which is cool, so like you were saying it’s nice to get everybody’s perspective on something to have a lot of different ideas flying around. I feel like when we have group conversations that happens.

K: We do try to make our games accessible so it’s nice to hear from everyone so we have a range of gaming hardcoreness and things that people value. Everyone has good ideas.

N: And I don’t think anyone is ever too intimidated to share their opinion. I’ve always felt that way in work and school. I’m a quiet person, and an introvert generally, but even I feel like I can share my stuff here. Everyone is at a different range of how we’re comfortable communicating and everyone here shares despite how different we all are.

KS: Would you agree that your games are feminist?

K: Yeah, yes. We are, I am pretty sure we are all feminists around here. Yes, we have feminist viewpoints, therefore the works we make are feminist.

N: I agree, that’s how I think about it. Some writers are like I am explicitly making a feminist piece of fiction, but I have never done that, it ends up being feminist because that’s my ideology. For me, and probably all of us, it’s more like that. Because it’s not like we’re sitting here thinking about “How can we make this more feminist?”

K: We are like what is this character going through, is this a cliché, what does this say about this character, what can we avoid?

N: And the cast of Tacoma is variously men and women of different races, which is intentional.

K: And it’s more women than men, and that’s how it is, and it’s awesome.

To read more of Issue 8.5, be sure to sign up to become a subscriber to our redesigned print magazine.

The post The story is in the details: A chat with Fullbright’s Nina Freeman and Karla Zimonja appeared first on Kill Screen.

June 27, 2016

The horror of living under martial law in 1960s Taiwan, now coming to videogames

Like a lot of the clashes between capitalist and communist factions in the early days of the Cold War, the Chinese Civil War was complex and multi-faceted. Even today, Taiwan calls itself the Republic of China, and China calls itself the People’s Republic of China. When they attend the same international events, Taiwan goes by the deliberately ambiguous title of “Chinese Taipei.”

The Civil War led to a violent ideological divide, and not long after it started, Taiwan was placed under martial law mandated by the “Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion,” which lasted from 1947 until 1987—the fighting ended in 1950, but no peace treaty was ever signed. During the period of martial law, only sanctioned political parties could exist, and the rights of free speech and free assembly were curtailed, and many people were imprisoned or executed.

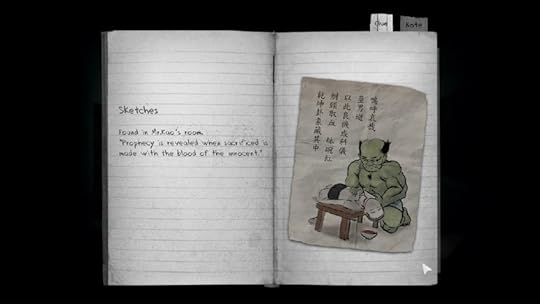

the lead designer couldn’t find any games that he felt represented his culture

Detention is an upcoming project from Taipei-based developer Red Candle Games. Set in the 1960s in a high-school in Taiwan, the horror game was conceived because the lead designer couldn’t find any games that he felt represented his culture, or that accurately showed the world the place he grew up in. To describe the political context or the statistics is one thing, but the everyday horrors of living under Taiwanese martial law are relatively inaccessible to modern English-speakers. Only a couple of popular films have taken the topic on, and one of the most well-regarded, the four-hour 1991 film A Brighter Summer Day, was only released in the US last year.

Red Candle launched their Steam Greenlight campaign (which has already been successful) and released a demo last month. The short demo blends the unease of living in a country where teachers encourage students to “rat out” communist behavior with ghostly folklore. Red Candle says their game is “full of Taiwanese flavor,” and it draws from traditions that are not common in the horror games I’ve played lately, full of zombies or werewolves. On one classroom wall, a portion of the Buddhist Diamond Sutra is written out, describing the importance of detaching from the mental constructs of the world. After the school is abandoned, you find dozens of Taoist talismans of protection pinned to a door.

In addition, Detention has a visual style that distinguishes it from many other games—it looks a lot like an old photograph. It’s worn around the edges, there are (mostly dingy yellow) colors here and there, and the characters especially have a distinct gelatin silver look to them. The translation in the demo is a bit rocky in spots, but it seems like Red Candle are going to be presenting a unique lens to a time and place that often ends up overlooked in games.

Detention is set for an August release, and you can find the trailer and the demo here.

The post The horror of living under martial law in 1960s Taiwan, now coming to videogames appeared first on Kill Screen.

Get a load of the fluid, feminine power of Gris

As of right now, there’s not a lot of information about Gris. We know it’s a 2D game. We know it has “zones.” We know it stars a woman clad in a flowing cloak reminiscent of the main character in Journey (2012). We know it takes place in a surreal environment largely dominated by a Mars-like red, and we know it’s being worked on by a team from both Barcelona and Tokyo. More than anything, though, we know it’s beautiful as all get out.

We know this because what has been revealed about the game, mostly through its social media accounts on Twitter and Instagram, has largely oriented around its detailed artwork from Barcelona-based illustrator Conrad Roset. Among it are mountains made of hands, butterflies made of triangles, trees made of squares, and temples that combine various other geometric shapes to make uncanny ruins. All of this works together to convey a type of whimsy one might find in fairy tale films like The Secret of Kells (2009) or The Last Unicorn (1982), but perhaps more impressive is the game’s main character.

A woman with a confident bob and an elegant stroll, she is the dominant presence in the short snippets of footage that have been released from the game so far. Her fluidity of animation rivals that seen in the upcoming Cuphead, and her poses and self-assured expressions evoke the type of feminine power found in the best fashion drawings. It’s no surprise, either: Conrad got his start in the professional art world working for fashion megahouse Zara. “I search the beauty the body exudes,” he writes on his site. “I like drawing the female figure.”

evoke the type of feminine power found in the best fashion drawings

Looking through the work on his site, it largely consists of a series of what he calls “muses,” paintings of women who are similarly arresting to Gris‘s lead. Avoiding the pitfalls of other art in the same style, especially that which attempts to highlight “the female form,” Conrad’s muses represent a variety of body types, emotional states, methods of expression, and fashion senses, and carry themselves with a certainty that does not seek to titillate as much as communicate. In other words, we are there for them, and not the other way around.

Most recently, Gris released its most extensive bit of footage yet, with a swelling piano score and a desolate environment. It’s still not much to go on, but when viewed alongside an earlier preview of the developers playing the game, wherein they glide in the air and follow a trail of leaves to their destination, the Journey comparisons appear to become stronger. However, while Journey‘s lead was always hidden under a hood, Gris‘s protagonist is not afraid to let her visage be seen.

This all makes for an impressive take that not only brings the bold design of Journey to players who never had a PS3, but also furthers the style by adding its own geometric and haute couture flourishes. While a release date for the game is not yet available, its worth it to follow its Instagram, which even when separated from the context of the game, stands on its own as just a stellar collection of artwork. Now if you’ll excuse me, I have some desktop wallpapers to change.

For more on Gris, visit its Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, and official site.

The post Get a load of the fluid, feminine power of Gris appeared first on Kill Screen.

How Tumblr is shaping the next generation of teenagers

It feels inappropriate to talk about a post-Brexit “fallout,” but the results of June 23rd’s referendum in the UK—in which 52 percent of the voting population urged for us to leave the EU—have pushed the term into usage. The fallout isn’t nuclear, as most writers adopting the term mean to imply, but generational—as the voting statistics prove (and, as always with Britain, it’s also entrenched in class divide). The Saturday morning after the day the results were counted, I went for my weekly shopping trip accompanied by my parents, who inevitably asked what I had voted. Upon saying the word “Remain” I witnessed it for the first time. My mother couldn’t control the childish glee of a loud “HA, HA!” that escaped her throat in that moment. She immediately mocked my loss. I had to bite my tongue and was surprised I didn’t taste blood.

Later that day, as I sat with a friend of my age and watched the news on TV, a woman of clearly very late age said that she voted to “Leave” because she “remembers the old days.” You have to understand that this is annoying to us because the old days are gone and aren’t coming back, and the referendum was to determine our future—which should comprise many more years than what this elderly woman had left in her. And so the sentiment we both blurted out without hesitation as she said her line was “but you’re gonna be dead soon.” It was a horrid and vicious retort, and yet it couldn’t be controlled, not unlike my mother’s more childlike tease earlier in the day. It’s these two snaps of the mouth that showed to me what these two generations truly feel and what we will attempt to bury within ourselves at every family meal from now on.

our homeland is online

I’ve been thinking what might have caused such huge generational divide as this. It has clearly always been there but has now surfaced its vile head off the back of this Brexit referendum. And I suspect, America, that when it comes to the sharp end of your presidential election in November this year, you will see and feel the same enormous chasm strike between your own people (Trump’s motto of “Make America Great Again” smacks of the same backwards-looking rhetoric after all). Gaps in generations are routine, of course, as we’ve witnessed with the emergence of the counterculture in the 1960s especially, when teenagers rebelled against the suburbia their parents had created for them after World War II, and dived into the Civil Rights movement and later protesting the Vietnam War. What played a large part in informing this rebellious youth culture was the rise of television, which “contributed to a heightened recognition of the disconnect between ideals and realities,” as Theresa Richardson writes in her paper “The Rise of Youth Counter Culture after World War II and the Popularization of Historical Knowledge: Then and Now.”

Photo from the Bernie Boston Collection, RIT Archive Collections, via Walker Art Center

If we can point to the spread of television as the piece of technology that affected the baby boomers and accelerated their views towards the counterculture (for it showed them the world in truer, more naked images than before), then we can say that the internet has served the same purpose for the youth of today. In both cases, children and teenagers have become much more aware of global concerns and are able to make friends with people in other countries more easily due to the latest technology (commercial aviation became common in the 1950s and ’60s). Millennials, as we are referred to, and the generation after my own, Generation Z (so-called “screenagers”), have been raised with the internet and social networks. Sometimes we are called “digital natives,” which is a term that makes the point I’m getting to: we may not feel as tied to a country and feel the same national pride as the generations before us because our homeland is online.

We are generations who are able to travel and work around the world and always return to the internet; a place where we can connect with others and educate ourselves no matter where we are in the world. Having this in our lives seems to have made us less nationalistic and more globally thinking on average than our parents. It’s why I have friends in Europe (and many other foreign countries) and do not wish to sever ties with them while my parents do not have that and can only argue for their “Leave” vote through what, in my eyes, seems to be unjustified and misinformed xenophobia—their main argument is that there are too many immigrants in Britain and they’re ruining our job market. They, of course, also believed the lies that the money Britain sends to the EU as part of the membership deal could be taken back and directly invested in our national services should we leave.

A few weeks ago, I was able to interview Danielle Strle, former director of community and content at Tumblr, after she spoke at the Kill Screen Festival. Looking back at it now, Strle’s answers provide a refreshing point-of-view from the emerging antagonism between parents and children I’ve seen around me and been part of myself recently. Speaking to Strle, it was immediately obvious to me why she had held her position at Tumblr for so many years. She has an unrelenting enthusiasm for what teenagers are doing with the internet and how it is pulling their attitudes and actions towards connecting with each other, exploring their identities, and tackling the greater turmoil of the world at large. It is this that many parents don’t see; they instead see a generation staring blankly at screens, thinking them isolated in a bubble when in fact it is the opposite.

Left to right: Nina Freeman, Danielle Strle, Jamin Warren, on stage at Kill Screen Festival, via @Jrnicus

Strle spoke with Nina Freeman, creator of Cibele (2015) and how do you Do It (2014), while on the stage, and as she did her eyes were lit with the passion a lover shows towards their life partner. “I really love that this is what videogames have evolved into,” Strle said to me immediately after she stepped off the stage. She told me that she grew up playing Mario and Sonic the Hedgehog as many people of our age did. “I just love that now there’s stories of meeting online and losing your virginity,” Strle said. I could tell that she really meant it. She’s a champion of the teenager and seems to live vicariously through them as they discover themselves through tools and communities like those offered by Tumblr. For the past five-and-a-half years, Strle has been at the forefront of supporting the new cultures that have originated online and made themselves physical through the kids and teenagers of today. It is, I would argue, what has set them apart from their parents more than anything else.

As you read my interview with Strle below, try to absorb her passion for the youth, and take it with you as you grow older yourself. The ancient Greek proverb goes: “A society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in.” In this post-Brexit “fallout,” the evidence we’re seeing is that many of the older generations of our present have forgotten that. Popular opinion among the youth is that we must now suffer for it as they slowly die out. We must try to do better.

KS: When did you first get into the internet and what were the websites you frequented? You mentioned AOL, but did you get into GeoCities where you could actually create your own website, for instance?

I got into AOL, I actually did get into GeoCities, but I was really into message boards as an exchange student in Japan in high school. Interestingly, this is 1995, 1996, Japan didn’t really have much dial-up internet, people weren’t connecting yet. But having a place to a) share my own stuff—I mean this was also pre-digital cameras—but like just share updates, not even photos really, but just like a “what’s up with Danielle” newsletter, from Japan.

KS: Did you have an audience in mind for those kind of things?

My family, you know, other exchange students, because I had connected with a bunch of people who either were currently exchange students or who were gonna be exchange students at the same time on this message board. So it was like a really scary thing, you know? I didn’t speak Japanese, I was going for a year, and it’s not a thing a lot of people do right? So it was an early experience of being able to find my crew online and learn from them and share with them, you know? So I remember the first time I saw Friendster, oh Friendster…

KS: Tell me about Friendster, I’m not really familiar with that one.

So, Friendster, I think it came out about nine months before MySpace, and it was pretty much the first social network, and you go on, you connect with all your friends, and you post status updates. It kinda looked a lot like Facebook, and it was amazing. It was the first time wide-scale internet stalking was really possible, because you could see your friends’ friends, which was like “oh, who’s that?” you know? But it was so slow, it got so popular so fast, and it just chugged, the site was impossible to use, and then MySpace came along and it was very zippy and everyone was like sharing music and stuff.

I remember I got an email, or a MySpace message, because I had listed a band I liked on the section for bands that you like. So I get a note from the guy from the band who’s like “Hey, I saw that you listed our band as a thing you like. We’re thinking about using MySpace to market our band, if you write me back and tell me if you’d be cool with that as a fan I’ll send you a CD.” And I was like “um, yes, also of course your fans want to hear from you, they put your band on their MySpace page they’ll be elated, as I am.” So then, of course, MySpace became this music marketing juggernaut, right? It was cool and special to be there and to watch all these mediums unfold and evolve into the communities that they are. MySpace got crazy man.

KS: It was crazy, I remember MySpace. At what point did you start to see differences between the different social networks and how you could tweak them to encourage different types of interactions with people?

Do you mean personally or at the platform level?

KS: Both.

Totally. I mean, I think Friendster was pretty simple, and also so freaking slow, it was like a tragedy. Like at the beginning it was mostly just seeing who your friends are friends with and having friends online. And MySpace was much more expressive, right? You can do all kinds of stuff with your MySpace page. People started learning HTML to add pictures to their MySpace page. It was just like a fun, kinda hacky time, and you have your [top 8]. But I think very quickly, especially at the beginning of all these things, behaviors evolve with the platform and with the group of friends you accumulate there, it’s easy to become… you become self conscious of the stuff you’re putting out online. That’s a thing that started at that time.

no matter what you’re into there are people getting really into it on Tumblr

When Facebook came along it was just so clean. MySpace looked insane, most pages, and also if you weren’t the type of person who was really thirsty for friends and then you land on the page of a person who was like that, it was like “ugh, this is weird, I don’t know you, why do you want to be my friend?” It started to get this seedy vibe to it at the end of MySpace times, and then Facebook was so clean and fresh. But my first true online community love was Flickr, I think, and the thing that really appealed to me so much about that is like, it was the beginning of web 2.0, everybody’s tagging stuff, metadata is a thing, by tagging your photos you’re contributing to this larger, searchable database of stuff, about whatever you’re taking pictures of, kinda adding that content layer to the stuff you’re publishing, and participating in a community that was ordered around content for the first time, as opposed to personal connections.

KS: Exactly, it’s a culture that forms.

Yeah. So I really really loved Flickr, and then Tumblr came along and it was the first thing… it just brought everything together. You could make a website for yourself super easy, you could mess with HTML if you wanted to, but you didn’t have to. That was super empowering. Then they added the dashboard feed where you could have all the blogs coming straight to you after you follow them, and that was a revolution for me, because previously I was going on a daily tour of my personal internet, “oh, what’s on Gawker.com, what’s on Gothamist.com, what’s on nymag.com?” And doing those in rotation, probably eight times a day, in my cubicle desk. So having all the blogs come to me, it was just like “woah this thing is amazing,” and it’s just been so magical to have watched the various communities grow and evolve there, like truly no matter what you’re into there are people getting really into it on Tumblr, which is cool.

KS: I think you touched on the one thing that Tumblr really embodies there. With MySpace, you could customize your page a lot if you knew what you were doing, so there was a lack of accessibility. Facebook was and still is impersonal. While Tumblr gave you a way to cultivate your own interests and also express yourself with the website design of your own blog. I haven’t done that, but I think if I was like 14 when I was first discovering Tumblr I would have been really excited about doing that.

The teenagers are like… I love them so much.

KS: What is it about teenagers?

They’re just so cool, they’re really smart, really funny, really encouraging to each other, at least most of the ones I run into online, they’re curious, they want to connect with other people. There’s a real desire to connect with other humanity about interests and they have the power to do that in a way teenagers have not had before. Young people tend to be the most politically progressive, their minds are open, their hearts are open, they’re being thoughtful about things.

This young generation of feminists who are like high-school age, they are driving feminism to the top of people’s lips. Yes, it’s celebrities, but mostly young female celebrities talking about stuff like the wage gap, but all of these young women online are talking to each other and empowering each other and encouraging each other to be woke, and demand equality. I don’t think that my generation of teenage women was thinking about it at all, and we weren’t really talking about it nearly as much, because you’d have to do that out loud, and you’d have to have a ringleader, but on the internet…

(Source)

KS: You’ve got that safety of the screen.

You’ve got the safety of the screen, and you can go find each other and, if you want to be a ring leader, you can ring lead a global army that you don’t have to meet. It gives me goosebumps, it’s so cool. How quickly transgender rights and transgender issues have come to the top of discussion is amazing.

KS: It is phenomenal.

It hasn’t been that many years, that people started talking about that at all, in the mainstream media, but now the president is issuing decrees about bathrooms. I don’t think that happens without young people organizing online and talking to each and waking everyone up.

KS: I feel like a lot of social issues, especially feminism and trans issues, is located on Tumblr. Do you think there’s a reason, perhaps something about the format of Tumblr, which encourages people towards that?

I mean the Reblog is incredibly powerful. You can take something from someone else’s blog to all of your followers and onto your blog with one click. It allows information to spread in a way that no other platform quite does. Yes, you can Retweet, but it’s different on Tumblr, because the media chunks tend to be bigger and more powerful and more visual. So I think it’s really architected for content and ideas to spread, and for people to bump into new ideas they might not otherwise, because they’re following a bunch of people who are Reblogging a bunch of stuff from all kinds of different places, and it comes into your media stream and it’s just this magical river of internet awesome, of new ideas.

I think that we live in an age when so many algorithms and so many platforms are just trying to serve up more of what the computer thinks we might want, based on what we’ve clicked on in the past, but because of the human element of Tumblr, your dashboard is just full of things people have Reblogged that you might not have bumped into on your own. You’re following this blog because you’re really into retrofuturist aesthetic and they post a lot of that good stuff, but then they also Reblog some politics thing because they care and are passionate about it and you’re bumped into that idea.

There’s this screen mediated internet friendship that I think is really special

I think that just in terms of even outside of social issue stuff, how much you can see people’s aesthetic evolve from exposure to Tumblr. I always enjoy doing this thing if I find a cool teen, like a really cool teen, I go on their archive and just scroll back over the years, and you can see these kid’s aesthetic evolving right before your very eyes, and it’s true of my own too. I have an animated gif blog, it’s just all Reblogs, it’s called Teen Girl Enthusiast, and I can see the evolution of my own aesthetic over time from exposure to the Tumblrsphere, it’s cool.

And I think the closest thing to that that I’ve experienced before, again, is on Flickr. I got really into this plant called coleus from randomly going down a rabbit hole and I feel like I’m kinda internet friends with this guy Joey’s planting, who I learnt so much about coleus from. We’ve just followed each other on all social media since we became friends on Flickr, we’ve never met. I mostly know how much he loves plants, and how good he is at doing plant stuff, but when his dog died I really cared, I sent him a note. There’s this screen mediated internet friendship that I think is really special.

KS: I presume you have met quite a few people you know online due to your former job. Do you feel more connected to them because you’ve met them online?

You know it’s funny, I always considered my role, and my team’s roles at Tumblr… we were not particularly well-known as individuals, right? We kinda stayed behind the curtain. Part of that was an early decision I made about my own safety because I know other people who have had high-profile community roles who have had terrible things happen, you know, like weird stalking stuff, creepy things, and you know it’s not really about us, it’s about the platform and the people doing stuff, we’re just there to show the world what great things people are doing.

So yeah, I never really considered that people might know me out and about in industry things, but I realize now that they do. And it’s been pretty cool to know that those people who know me, or those people I know because I’ve been following their career and I think that they’re cool and their work seems awesome, that some of those people also think that about me, which is great and then we meet and then we’re like “we already kinda know each other, this is cool.”

But there’s also that thing of a friend whose just online, you only see them on Facebook, you only see them on Instagram or whatever, and then you run into them and it’s like “oh my gosh it’s great to see you… but I know everything you’ve been doing,” you know? “Those pictures of Antarctica are amazing!” That person doesn’t get to be like “I just got back from Antarctica it was amazing.” You can go deeper, you know?

KS: Yeah. You mentioned there how you tried to keep out of the spotlight, but how much did you let yourselves get involved with things like harassment? Because you don’t hear about any of that at Tumblr. But you do hear about it when it happens on Twitter…

Tumblr is a nice place, people who hang out on Tumblr tend to be nice. Our like button has always been a heart.

KS: Do you think those little decisions make big impacts like that?

Definitely. You can reply now because the internet is a different place, and comments and replies are I think different now than they were in Tumblr’s foundational time, but in the beginning you couldn’t have comments. If you wanted to say something about someone’s post you had to take it to your own blog and own whatever it is you’re going to say, and I think that did a really good job of discouraging trollish behavior because you’re revealing yourself to be a troll on your own thing, and not being a troll under someone else’s work. Also Tumblr has an incredible trust and safety team that deals with any less nice issues that come with running a global platform that’ll allow you to post whatever you want on the internet. But yeah, there’s a whole team.

KS: Doing the invisible work of monitoring a huge platform?

I mean just answering, looking through any complaints that we get, that kind of thing. But I really do feel that Tumblr has been a very responsible actor when it comes to stuff like that. And just like the people are nice, you know?

KS: That’s good to hear. I’ve always wanted to know how Tumblr policed the porn that it hosts. But by the sounds of it you kind of just let it flow and people police it themselves.

Yeah, Tumblr’s a place for free speech, there is stuff that Tumblr will take down, content that’s harmful to minors, gore kind of stuff, but otherwise Tumblr is happy to have you post what you want. Not all countries are as cool with that as America, which… we’re lucky to be in America. But yeah, it’s a place of great freedom of expression and largely people abide by good behaviors.

KS: It’s great that you can give people that freedom on Tumblr and they seem to cherish it enough not to take it too far. It seems if you put barriers up people will try to break them deliberately and you see that on other platforms quite a lot I think.

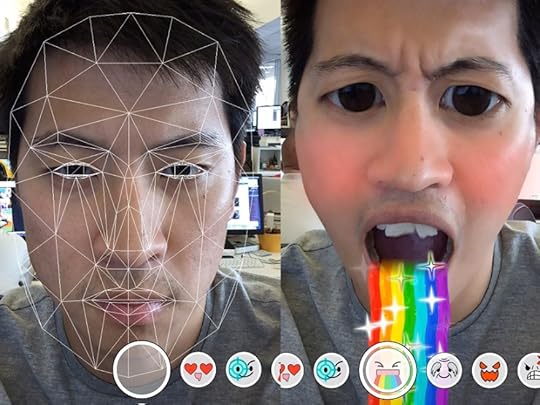

It was really interesting to watch the ups and downs of Reddit over the past few years around all of this stuff, and to see other people come up and try and make new platforms that either don’t have to deal with those issues or establish new norms that don’t allow for it. It’ll be interesting to see. I really love, love, love Snapchat, but you know who even knows what’s going on inside there, because it’s all disappearing and it’s all mostly private to your group of your people that you’re following. So I imagine they have some crazy algorithm that I can’t even imagine.

via Tech Insider

KS: It’s pretty wild, I wouldn’t want to see it, I don’t think.

Oh Snapchat, so cool, so fun. Do you Snapchat?

KS: I don’t actually, no. I feel like I should.

It’s a really fun creative medium. There’s some people, I always want to watch their stories, usually friends who are far away. I feel like I’ve stayed better connected to friends who live in Austin or friends who live in Iceland, or friends who live in New Zealand, because we can communicate through Snapchat and it’s just a little bit more rich and a little bit more personal and connected than following on Instagram, you know? I know what’s going on with them.

KS: It’s personal, isn’t it?

Yeah, and you can do really fun stuff with it, the face filters…

KS: Oh yeah, I’ve seen those. Just to wrap this up, now that you’ve left Tumblr, what are you up to next?

I’m hoping to do an incubator in the fall. I’m investing in some stuff and advising on some things.

KS: You mentioned on stage you’re interested in how Tumblr and these communities help kids learn certain skills they can use in life an in jobs, is that something you’re interested in pursuing, it seemed like it might be?

I’m definitely not done with the online community space, it’s very near and dear to my heart.

///

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Header image: Malala Yousafzai, the youngest-ever Nobel Prize laureate, via PopSugar

The post How Tumblr is shaping the next generation of teenagers appeared first on Kill Screen.

Doom mod lets you hangout with the cast of Seinfeld

Here’s something you probably know: Doom II (1994) and Seinfeld (1989-1998) are both pieces of popular culture released in the 1990s. They both had huge audiences and now two decades later, they are still as well known as they were when Bill Clinton was in office. In fact, this year’s Doom was released to great reviews. And you can probably turn TBS on right now and catch an episode of Seinfeld.

But here’s something you probably don’t know: Doom and Seinfeld have now been coupled. Yes, thanks to the work of Doug Keener, it is now possible to explore Jerry’s famous apartment in Doom II (you can download his level here). It took over 100 hours of work to create this love letter to Seinfeld and the results are both impressive and a bit scary. (Fun fact: While Keener spent over 100 hours working on this level, the the total number of Seinfeld hours that exists is about 90).

I’ve been a huge fan of Seinfeld for most of my life, and the amount of detail put into the level shows that Keener either really loves Seinfeld or has hate-watched the show enough that every detail has been burned into his brain. Either way, the apartment is a near perfect recreation of the original. Which is made even more impressive by the fact he recreated it using Doom II.

This is not the first time that Seinfeld has made appearances in videogames. In fact, many people over the years have created mods that inject your favorite game with some classic Seinfeld. Like the mod that fully recreates the apartment and all of the characters in The Sims 4 (2014). Or the mod which adds paintings of George Costanza into Dark Souls (2011). Of course, if you want something more subtle, you could download the mod that adds a picture of Jerry Seinfeld to the side of a gun found in Team Fortress 2 (2007).

How much Seinfeld do you want to experience?

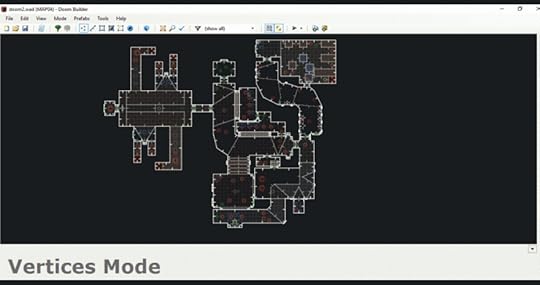

But Keener’s creation seems more complicated than any of these creations. It’s why I was curious as to how complex this .wad was (.wad is a file format used in Doom to generate the levels, textures, and sounds). So I opened Doom Builder and loaded the Seinfeld .wad up. What I found was mesmerizing. A strange and dense mess of lines and dots. Compare this to a map that shipped with Doom II, in this case E1M4, and you can see how surprisingly advanced this Seinfeld map is. The Seinfeld .wad won’t even run in classic Doom. You have to run the map in zdoom, a source port that allows levels to be bigger and more complex that the original Doom II could handle.

A gif that compares the Seinfeld .wad to a typical Doom II .wad

Of course, this is still Doom II, which means that you still have a shotgun. So if you feel like brutally killing the cast of Seinfeld off you can do that. They each have their own death animation and audio. But you can also just sit back and chill with the beloved characters of the show. And, as they do on the show, they’ll get up to some shenanigans as you watch. For example, Kramer walked on top of Jerry’s couch when I was playing. He just walked up onto the couch and started hanging out up there. What a zany character he is.

If you go looking for secrets you’ll find one. You can find Newman hanging out at Kramer’s apartment across the hall from Seinfeld’s place. Appropriately, Newman can be found in a monster closet. Which makes a lot of sense. Newman is a monster.

There isn’t much more to the Seinfeld .wad. There is no exit or door to unlock. You decide when to leave. You could, of course, decide to never leave. It’s up to you. How much Seinfeld do you want to experience? For me it was about seven minutes. And for those out there who have a desire to live in this Seinfeld meets Doom paradise, you can always load up the VR mod for Doom. Then pop on a VR headset and experience Seinfeld in virtual reality.

Download the Seinfeld .wad for Doom II right here.

The post Doom mod lets you hangout with the cast of Seinfeld appeared first on Kill Screen.

Everyone and everything is awful: Notes on the Brexit and the game design of referendum

We have reached the recriminations stage of the United Kingdom’s referendum on continued European Union membership. One might reasonably argue that the whole campaign has taken place in this stage from the start—recrimination is Brexit’s natural state of being.

But, in short: everyone’s mad; everyone’s an idiot; everything’s fucked up.

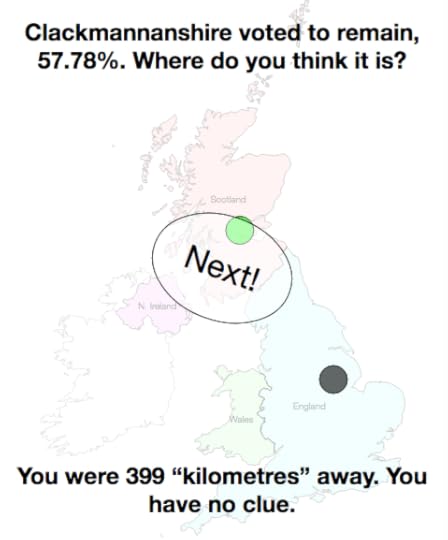

Here, then, is Toph Tucker’s The Brexit Game, which is not very good but captures the zeitgeist reasonably well. It is basically an excuse to call other people idiots. The game was coded at a bar and gives you the name of a place in the United Kingdom and the percentage of its voters who favored Remain or Leave, then challenges you to place it on a map. If you’re too far off the mark, it says “you have no clue” in a large typeface.

Most of us don’t have a clue, but where do we go from there? You’ll hear plenty about ignoring referendum results or letting younger people vote. Someone you know will talk about a knowledge test for voting, as if that would fix a broken polity. None of these are a brilliant idea—some of them are outright bad—but it’s not like there’s a good idea kicking around. The least godawful idea will soon look very good. “The trouble with committing political suicide,” as Winston Churchill once noted, “is that you live to regret it.”

the United Kingdom is more of a suggestion than a political or geographic reality going forward

How did we get here? In part, it’s a product of bad game design. A referendum in which a significant portion of voters believes its votes are not binding is fundamentally flawed. (Then again, this sort of problem is not unprecedented. The European Union’s Maastricht Treaty, for instance, was only passed after a number of failed referenda. You can’t entirely blame voters for expecting history to repeat itself, as it may well yet depending on the willingness of future prime ministers to invoke Article 50.) But try to imagine a game where an action is supposed to have a concrete consequence but a plurality of players believe it doesn’t, and then… maybe it doesn’t? This is not a workable system, but it is where we now find ourselves.

This is, to be clear, not solely a design problem: xenophobic and violent incidents have risen in recent days; an MP is dead; economic losses are mounting; the United Kingdom is more of a suggestion than a political or geographic reality going forward. Those are all tangible realities. But the design problems still haunt. The idea of “ever closer union” is not just a motto for European Integration but also a structural content; it’s supposed to get harder to reverse the Union’s ‘progress’ with time. There will probably be more referenda now—if not in the United Kingdom then elsewhere. The rules of the game are a bit clearer now—a referendum isn’t just an empty expression of anger—but not so much so that it’s clear where we go next. What could possibly go wrong?

You can play The Brexit Game in your browser.

The post Everyone and everything is awful: Notes on the Brexit and the game design of referendum appeared first on Kill Screen.

NEST is a cute game poem about best bird buds

Crows, it turns out, are probably smarter than you think. They seem to be able to recognize human faces and craft tools to solve problems they run up against—the problem pretty much always being a lack of food, but still. You learn this as you play Cullen Dwyer’s new game NEST, which he gives a kind of epigraph for on its itch.io page: “Explore the forest as a crow/ and try to make friends/ with whom to find treasure and secrets.”

NEST is a short game, and more than anything else it resembles Knytt or the small and atmosphere-heavy platformers of the early 2000s built in Game Maker. Part of that connection comes from the tiled visuals and the smooth movement, but there are similarities in the design sensibilities, too. When you first launch into the air, four little red bubbles spin around you, immediately making it clear that you have four more flaps before you have to coast to the ground. You can chirp back and forth with other birds to convince them to follow you or make them do stuff (carry things, mostly) to further the goals of your growing bird-cult.

NEST feels precise in the way that a verse might

Visuals with sprites this sparse can be difficult to read, but NEST solves that problem in a number of ways: by extending its sense of minimalism to its color palette, it keeps you from ever losing your bright red crow in the dark greens of the forest. And by building its obstacles in the simplest identifiable shapes, it makes your goals very clear from the outset without textual help.

It’s fitting that the itch.io page describes the game with a poem, because NEST feels precise in the way that a verse might. The repetition and rhythm that can be found in a lot of games are presented here with so little embellishment that those forms are significant parts of the experience, from the flaps to the chirps to your three bird-friends and the three diamonds in the altar.

You can download NEST for Windows here.

The post NEST is a cute game poem about best bird buds appeared first on Kill Screen.

Throwing money at the screen

It is well known and well documented by now that many videogames released within the last decade are fantasies of accumulation: of experience points, of wealth, of abilities, of guns, of power. That is to say, the power fantasy that these games peddle is built on the idea of upward mobility, that someone can start with nothing, and through hard work and the sheer force of will, gain money and influence. “It is a power fantasy that reflects our time,” writes game critic Austin Walker, “We want to be reassured that our effort will pay off in the end, that progress is guaranteed, and that our achievements are fully our own.” Walker has helpfully dubbed this dynamic the “new power fantasy.”

Other writers have elaborated on the new power fantasy, albeit without referring to it by name. Ed Smith has noted how the systems by which games go about rewarding players is often based on a utopian distortion of “real-life wage/labour systems, whereby hours worked are equivalent to money earned,” wherein games “appeal not to a player’s altruism or morality, but to their desire for material.” In his explication of the colonialist tendencies of open-world games, Brendan Keogh notes how gameworlds are “reduced to resource and commodity for the Western subject” through the basic structures of open-world games: “how various hidden objects and power-ups can be found,” how “side missions and quests can be completed for bonus rewards.” Though Smith and Keogh don’t identify Walker’s new power fantasy, the mechanisms they describe are endemic to it. From these writer’s observations, we can ascertain that the new power fantasy is based in particularly destructive Western ideals, particularly the notion of meritocracy.

Digital art critic Lana Polansky explicitly tied Walker’s new power fantasy to meritocracy in the last days of 2014. In her essay, Polansky relates the new power fantasy “the shifting positions of the owner and the buyer,” diagnosing and challenging the tendency of retail videogames to centralize the ego of the player while simultaneously “asking the player to expend more time, skill and energy to keep proving their worth.” To this end, Polansky cites the art critic John Berger’s book (and the precedent BBC Television series) Ways of Seeing (1972). In her brief explication of his book, Polansky cites Berger’s observations on the European Art tradition of oil painting, specifically his idea that oil paint is “the perfect medium through which to propagandize capitalist excess.”

images are made to appeal to the player’s “desire for material”

Polansky’s invocation of Berger is illuminating, not only because of the purpose it serves within Polansky’s original argument, but because the specific way in which oil painting is able to represent capitalist excess can be examined to reveal a different sort of supposed meritocracy that has emerged within games: one that is perhaps more sinister than the new power fantasy, if only because it has been allowed to persist, unidentified and unquestioned. It is not based on the systems that players engage with, but the way players experience the images of games. Players’ experiences of images have been warped by the values at the heart of the new power fantasy: images are made to appeal not to the player’s aesthetic sensibilities, but to her “desire for material.” Images have been reduced to commodity. It is a phenomenon that finds its parallel in the medium of oil paint.

In Ways of Seeing, John Berger writes that what differentiates the tradition of European oil painting (a tradition that lasted from around 1500-1900) from other forms of painting is “its special ability to render the tangibility, the texture, the lustre, the solidity of what it depicts.” Berger uses Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533) as a prototypical example of the tradition, and upon examining it, you can see the way in which the surfaces of luxurious objects (the clothes, the jewelry, the curtains, the navigation tools) were reproduced by the painter to emphasize the extent to which those objects had been intricately worked over “by weavers, embroiderers, carpet-makers, goldsmiths, leather workers, mosaic-makers, furriers, tailors, [and] jewelers.” That is to say, the realism of oil painting emphasizes the craft behind the objects depicted, in order to create the illusion within the spectator that what she is seeing is a real object. It is this illusory realism that allows the oil painting to appeal to the sense of touch through strictly visual means. What the eye perceives is translated “within the painting itself,” writes Berger, “into the language of tactile sensation.” To see an oil portrait is to feel the materials depicted within it, to be confronted with those materials’ quality in such a way as to confirm their authenticity. For the oil painting, the real is “that which you can put your hands on.”

Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors via Wikimedia

It isn’t difficult to identify a similar fixation on texture within videogames. Digital games are, after all, images and text that players can manipulate via mediating devices like controllers, mice, and touchscreens. The duality of the oil painting finds some measure of continuity in the modern videogame, insofar as both are images that are simultaneously seen and, in some sense, felt. In videogames, this notion of “texture” manifests itself primarily in two ways: through the art assets that are placed atop digital objects to present the illusion of materiality (which are actually referred to as “textures”), and through the physical sense of touch that is allowed by those aforementioned mediating devices. The former sort of texture is experienced in a manner similar to that of oil painting, as these visual art assets are usually integrated in such a way as to suggest that a digital object is actually constructed from real materials like wood or metal. Processes like bump mapping, in which the appearance of bumps and scratches are simulated on digital objects without changing the object’s geometry, are even employed in tandem with textures to further the illusion that digital objects possess a true materiality. However, as effective as that illusion can be, the second variety of texture, that which is directly experienced through the sense of touch, is more immediate.

Visual art and bump maps may appeal to our sense of touch through the visual, but that metaphorical sensation is overwritten by the literal, overpowered by the actual sensation of physical contact. The nature of this contact, this physically-felt texture, can be elucidated by interrogating what we actually “touch” when we come into contact with digital objects within the space of a videogame. When an avatar bumps up against a wall within a gameworld, the feeling of the substance (i.e. wood or metal) that is referred to by the art covering the wall does not translate literally to our sense of touch; nor do the imperfections and dents that are simulated through normal mapping. The wall’s visual appearance may appeal to the sense of touch, but when it is ‘felt’ it is little more than a flat plane. The player’s ability to approach digital objects in this way—to break this visual illusion of material-ness—is what allows the physical texture to supersede the visual. However, what is perhaps more revealing than the property digital objects lose is what they retain: while videogame objects lose their surfaces when they are touched, they retain their solidity. This solidity is preserved because solidity of an object is its only aspect that is in conversation with movement.

Movement is the physical texture of the videogame medium. When the player “feels” a videogame, she is feeling the sensation of motion. Objects retain their solidity for the sake of halting that motion: for example, when Faith runs up to a wall and extends her hands in Mirror’s Edge (2008), the player herself feels no difference in the touch of a cement wall or a glass window, as their purpose within the physical texture of the movement is identical. Most often, when a videogame can be said to have a certain tactile sensation, that sensation is tied to an entity’s movement through a space: whether that entity is a body, a vehicle, or the “camera” is irrelevant, so long as the entity’s movement through space corresponds to some kind of button press, trigger pull, or mouse swipe. The texture of a videogame is that of a turning head, or the heft of a swung sword, the immediate thrust of a quick jump.

when a videogame can be said to have a certain tactile sensation that sensation is tied to movement

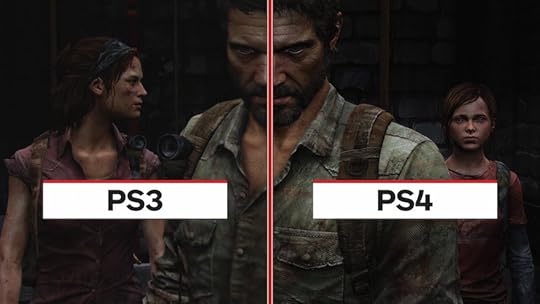

In a sense, the primary texture of the videogame is the antithesis of the texture of the oil painting. Whereas the tactile sensation of oil painting lies in the perceived feeling of materials, the primary tactile sensation of videogames lies in the absence of materials, in unhindered motion through airless space. However, despite this apparently significant difference, the texture of oil painting and the dominant texture of the videogame are crucially similar in one way: both are expressions of wealth. We see this in videogames, especially, through the fixation on frame rates and the high-performance machines that can achieve the faster ones. The fascination makes sense if you understand videogames’ most luxurious texture to be motion—the higher the frame rate, the smoother and more precise a game can feel. This resultantly sleek, fluid movement has led many to consider a higher frame rate to be an objective good: if a player has the means to play a game with a higher frame rate, then she should play a game with a higher frame rate.

Before addressing how this erroneous assumption harms the discussion and development of videogame aesthetics, it’s worth remembering that most people who play videogames do not have the means to experience most games at a frame rate of 60 plus. Most retail videogames will run at a perfectly serviceable 30 frames per second on more affordable consoles and computers, but this more easily achievable and affordable frame rate is rarely standardized across platforms, meaning that the frame rate will often vary wildly across different devices. This inconsistency goes largely unquestioned by developers, publishers, and hardware manufacturers, leaving the onus of running a game at a high frame rate on the player. And so, she who has been pressured into playing the latest retail release at a frame rate, which the general discourse (wrongfully) insists is optimal, must submit to the following dynamic: the higher the desired frame rate, the more powerful a device she must use; and the more powerful a device is, the more expensive it will be. This dynamic lends to the images of videogames a hierarchy, a class divide wherein images from the same game can be said to have different worths based on the machine that rendered them. A blockbuster videogame running at a high resolution with a high frame rate is impressive not because those aspects of the image carry any insights as to the game’s themes, or elevate its style: they are impressive because they have a high market value, because the machine that produced those images was expensive.

How does this dynamic—the linking of the dollar value of an image to the texture of motion—affect our experience of a videogame’s images? To begin to interrogate this question, take a minute to watch this video (in the highest possible settings your internet connection can manage, and preferably with the annotations off):

What, exactly, is this video doing?

Firstly, it is, like all videos of its genre, a form of advertising. Its primary concern is exposing the spectator to an incomplete experience of a videogame: an experience wherein the audience can see, but not touch. In its removal of the controller, of the literal tactile sensation, the video is meant to seduce the spectator-buyer, suggesting an alternate reality in which the spectator is also a player (another modern rendition of the spectator-owner) and has been granted access to the full breadth of sensations that are implied by the video. But what, exactly, is the video trying to sell?

The ‘incompleteness’ of the video—its removal of the physical sensation of play—lends it a profound correspondence with the tradition of oil painting that illuminates the video’s true purpose. Although the dimension of physical touch has been removed, the video, like oil painting, still appeals to the language of tactile sensation strictly through its visuals. The smoothness and precision of motion remain tangible, and so the video appears to be demonstrating how the game will, as Berger puts it, “reward the touch, the hand, of the owner.”