Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 101

June 23, 2016

The beautiful Eastern European folktales behind Forest of Sleep

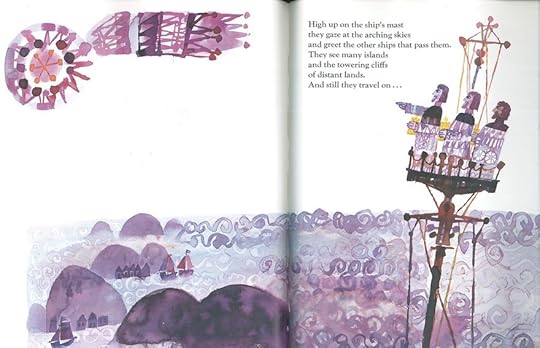

Forest of Sleep, the procedural adventure inspired by oral storytelling and the latest brainchild from the creator of Proteus (2013), looks more like a children’s book than a videogame. Early screenshots unapologetically resemble artwork, illustrated with bold borders and thick lines and no UI in sight. In an interview with the Forest of Sleep team, producer Hannah Nicklin talks to artist and animator Nicolai Troshinsky about his illustration background, and connection to the Eastern European folklore that permeates their game.

a slower style, filled with tiny gestures

Troshinsky discusses how he and Ed Key, the co-creator of Forest of Sleep, tossed around ideas after meeting at IGF in 2011 and settled on the idea of Russian folktales: they wanted to overcome the “self-referential” nature of many videogames and draw from sources other than gaming’s common inspirations. Animation and film’s influence led to the current look of the game, which lacks speech or text. Troshinsky instead creates a visual language that guides the player through their own story, a fairy tale dreamed up in the minds of three children that fell asleep around a campfire.

Štěpán Zavřel via The Illustrated Book Image Collective

While discussing his graphic inspirations, Troshinsky references Czech illustrator Štěpán Zavřel, as well as Polish artists Janusz Stanny and Józef Wilkoń. He compares Eastern European animation to the style more common in the West, pointing out that Eastern animation is “fascinated by the ordinary” and tends to be less flashy. His inspirations prefer a slower style, filled with tiny gestures, that doesn’t try to be thrilling or grand. Luckily, this ties in well with Forest of Sleep’s wish to go entirely without words. Troshinsky is tasked with figuring out how to communicate these stories visually, and bridging the “imaginative leap” between the game and the player.

Forest of Sleep is due to tell its story in late 2016, but Twisted Tree promises many more posts exploring behind the scenes before then. With such a beautiful game, it’s a small wonder that the team has so much to say.

Read the full interview with Nicolai on Forest of Sleep’s blog .

The post The beautiful Eastern European folktales behind Forest of Sleep appeared first on Kill Screen.

Game developer Barbie reattempts to open doors for young girls

Mattel’s Barbie is a woman of many jobs thanks to her careers line. Teacher, babysitter, pilot, lifeguard, nurse, chef… the list goes on. The latest addition to Barbie’s resume is game developer, and she’s been very well received, selling out on Mattel’s site in a matter of days. Whether these were sales from adults for themselves or for children we don’t know, but it’s clear people are excited.

Many may remember the impressively tone-deaf Barbie: I Can Be A Computer Engineer, which featured such infamous exchanges as:

“‘I’m only creating the design ideas,’ Barbie says, laughing. ‘I’ll need Steven’s and Brian’s help to turn it into a real game!’”

Barbie then proceeds to infect both her and her sisters computers with viruses, which she is only able to have removed by her male friends. This understandably sparked quite a bit of backlash, including the delightful Feminist Hacker Barbie. Mattel quickly apologized.

Game Developer Barbie is everything that Computer Engineer Barbie could have been. Of course, it’s totally fine if, in real life, a game developing team consists of some people who only design and other members who only program. But the problem with Computer Engineer Barbie was the insinuation that the female computer engineer needed men to do the whole computer engineering part for them. But Game Developer Barbie approaches this much more realistically, saying on the back of the box, “Because there are so many aspects to creating a game, team work is important.”

highlighting a career that is uniquely modern

With real code on her laptop screen, a tablet displaying the game she’s creating, and criticism about her outfit, Game Developer Barbie is just about as real as a Barbie can get. If Mattel is really as invested in inspiring girls as they claim, this is the step to take. By highlighting a career that is uniquely modern, they are inviting girls to imagine themselves shaping the play of the future.

Game Developer Barbie is available (when restocked) from Mattel here.

The post Game developer Barbie reattempts to open doors for young girls appeared first on Kill Screen.

Absolver is the low-poly, God Hand-inspired brawler of your dreams

It’s tempting to describe Absolver with an endless stream of references to other games—big ones, the type for which you see cardboard cutouts at GameStop. It’s an online multiplayer game riffing on the model of Destiny (2014) or Dark Souls (2011)—not, they clarify, an MMO—with players both friendly and unfriendly roaming a semi-open world. The elegantly low-poly world has the feel of a somber The Witness, and its tight, frame-specific combat recalls the brawlers of Platinum Games.

But that laundry list sells it short. Tucked back in an Airstream trailer, far enough from the Los Angeles Convention Center to allow me to breathe easy, Absolver was easily the most interesting game I saw at E3: vividly art directed, mechanically robust, and thrillingly unformed. Its world was designed in broken, arcing pathways, the natural world crawling out of the ruins and blending into the greater landscape. Its interactions play like a more ambiguous Journey (2012). You might kick down a door into dappled sunlight, look out across a veranda, and see a few other masked warriors engaging in balletic combat. They could be friends or enemies, possible teachers or unremarkable passersby—there are no cues aside from the nature in which they approach you.

vividly art directed, mechanically robust, and thrillingly unformed

Its combat starts simple—two buttons, plus dodging. But even in the short demo I played, it scaled up into a dizzying complexity, employing skillful misdirection, weapons, and a byzantine, interlocking set of stances and attributes with which players develop a bespoke fighting style. It’s notably slow, “giving you time to see what’s happening and to react,” according to programmer Olivier Gaertner. That generous reaction time did not stop Gaertner from kicking the shit out of me, such that he eventually just put the controller down so I could get some hits in, but the nature of the combat was still shockingly intimate, full of feints and volleys, more like a drag-out argument between friends than the endless power-fantasy and cuckoldry of other competitive games.

Absolver’s designer, Jordan Layani, cited as inspiration 2006’s God Hand—a wildly misunderstood brawler developed in the golden years of the PlayStation 2. “Some reviewers seemed to like it, others said, ‘What is this shit?’” he laughed. Absolver looks to make that game’s core mechanical conceit relevant through polish and sheer post-apocalyptic sheen.

Beyond those two elements, though, all is in flux. Gaertner and Layani were refreshingly candid about this. The two met at Ubisoft, before leaving to form Sloclap along with two other coworkers. (The team now numbers 20 people.) It’s perhaps this big-studio background that lends the game its incredible refinement. This was no passion project: the four designers initially went out looking for a solid mechanical experience, and when they found it—the one-on-one fisticuffs, which scaled easily into double-digit brawls—they built all of the game’s systems on top of it.

They could chart a story outline for me and some rough plans for the modes they intended to implement, including procedurally generated labyrinths and other back-of-the-box bulletpoints, but what they were there to show was a form of interaction and a lovely, ruined world in which to do it. It’s enough. The little bit they have glitters with possibility, at once more stolidly old-school and daringly unconventional than any of the brighter names just a few blocks away.

You can find out more about Absolver over on its website. It’s coming to PC and consoles in 2017.

The post Absolver is the low-poly, God Hand-inspired brawler of your dreams appeared first on Kill Screen.

Play a day in the life of a dystopian bartender

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

VA-11 Hall-A (Windows, Mac, Linux)

BY SUKEBAN GAMES

If you want to get to know the character of a city quickly, check out its bar scene. There, you’ll find all the community’s hopes and issues under the same roof, sharing a stiff drink. That’s the idea behind VA-11 Hall-A, a dystopian “drink-em-up” where players serve the bar regulars and listen to their personal stories. By developing relationships with your patrons, you learn about the everyday struggles of a consumerist surveillance state. While light on mechanics, VA-11 Hall-A allows you to subtly affect the story through your actions and dialogue. By mastering the bartending mini-game, you can pump some of the city’s most interesting characters for more information—just be sure to keep them good and sauced.

Perfect for: Blade Runner wannabes, alcoholics, dystopian junkies

Playtime: 10-15 hours

The post Play a day in the life of a dystopian bartender appeared first on Kill Screen.

Bravely Second: End Layer turns play into labor

Bravely Second is as unfortunate a title for a sequel as Bravely Default was for its predecessor. Where the phrase “Bravely Default” seemed to suggest that it would somehow be valiant for you to keep doing whatever you would have ordinarily done anyway, “Bravely Second” is poised to become a snowclone to tag onto any sequel that boldly exists in spite of the fact that no one especially wanted it. Horrible Bosses 2: Bravely Second. Or, a slight tweak on the form, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child: Bravely Eighth.

Of course, the title isn’t as bad as it seems once you’ve played the game—though it is worth pointing out that that’s not usually the way titles work. For those who aren’t familiar with the first game, Bravely Default referred to the series’s innovations in what was otherwise—Phoenix Downs and all—a traditional Final Fantasy-like role playing game. The series’s combat system adds “Brave” and “Default” to the usual menu of RPG options for spending your turn: Attack, Item, Run, etc. Braving allows you to take multiple turns this turn at the expense of future turns, while Defaulting puts you on the defensive this turn with the benefit of allowing you to take more turns next time.

the brave/default system emphasizes empty grinding

It might be a solid way to gamify teaching you to save for retirement if Defaulting rewarded you half as often as Braving does. Instead, the mechanic adds a bit of gambling logic to the usual RPG my-numbers-versus-your-numbers confrontation—mirroring, to my mind, the false choice around whether to stay or hit in blackjack. If you brave against an enemy you don’t think you can kill this turn—the equivalent of hitting on 17—you could bust, or you could score a dramatic win. Which, as in blackjack, is thrilling if you win, but, if you’re playing pot odds … well, then you wouldn’t be playing blackjack anyway.

Clever as it is, the brave/default system has the unfortunate side effect of emphasizing what is surely the worst part of this type of RPG: the empty grinding that defines so much of the time you spend with the game. Grinding is a bit like living, only without any occasion or obligation to remember what you’ve done. It offers so little in return for our time that we feel excited when we’re paid out a pittance like a dropped item or a level-up in return for hours of crushing recursion. Victory against a strong enemy immediately feels good because it seems to be the natural conclusion of all that came before it, the pains you took to reach the requisite level. But interrogate that feeling of fiero even for a second and you recognize that all the grinding was a sufficient, but in no way necessary, condition for you to feel like you won something consequential.

Part of me has always felt that grinding is a perverse form of job training, a way of building those lauded 21st-century workplace values like grit or working off the clock. The brave mechanic attempts to (and here too I find myself falling into the language of business) streamline some of the genre’s conventional repetitiousness by allowing you to enter multiple commands at once, doing away with weak enemies without having to play through several turns making the same choice regardless of what happens during combat. But in planning four moves ahead, you recognize the emptiness of most encounters, realizing that you were always already going to make the same four choices over and over. This is further amplified by an “auto-battle” system, whose logical extension would seem to be a game that plays itself, merely encouraging you to check on it once in a while to see how well “you” are doing. To return to the cubicle simile, the Bravely series’s innovations feel more like a new version of Excel than a fulfilling job. Its improvements aren’t so much ways of bettering your life as they are freedoms from what arbitrarily held you back before.

Look closer and the connections between “the daily grind” and this form of “play” multiply, spiral out, form fractals. In order to use the game’s titular Bravely Second system—which allows you to stop time and do massive damage to, usually, a boss, a form of sanctioned corporate revolt—you have to spend Sleep Points, which accrue at a rate of 1 for every 8 hours of gameplay—or, to drive home the obvious point, 1 for the typical amount of time you’d work for a day’s wages. Time thus becomes a minigame chugging away quietly in the background, staying your fatigue from yet another (auto?) battle with the promise that, soon, you will have earned your sleep. Rather perfectly, you can also buy your way out of this time paradox if you’re sufficiently wealthy/impatient by plunking down stray dollars for Sleep Points.

connections between “daily grind” and this form of “play” multiply

I don’t doubt fans of this type of RPG will recognize my criticisms, even if they don’t countenance them. Perhaps they know something that I don’t, that play is more fun with/as labor. Or else they have long since accepted that play and labor need not be separate, or can be separated in context even while unified in action. I rather coldly put myself at a distance from “fans of this type of RPG” at the top of this paragraph, but the truth is that before playing Bravely Second, I would have counted myself a part of that group. I played a more or less unconscionable amount of Pokémon and Final Fantasy growing up. By trying to optimize it, the brave/default system inadvertently lays bare the arbitrariness structuring the player’s relation to the game, the role one ostensibly plays becoming repeatable and, indeed, automatable in yet another striking parallel to the looming “new economy.” In fact, I wonder if an optimistic reading of Bravely Second isn’t as a critique of the RPG tropes it relies upon. After all, the main character, much too punningly, is called “Yew,” after the opening cutscene addresses “you” the player separately, just in case you didn’t pick up on the homophone. But, to give credit where credit is due is to withhold it where it isn’t; and that idea seems to leave open a possibility that just is not there.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Bravely Second: End Layer turns play into labor appeared first on Kill Screen.

June 22, 2016

Luc Belaire Launches #BelaireBacked Program to Help Kickstarter Campaigners Skip to the Celebration

French wine brand Luc Belaire is proud to announce the start of its #BelaireBacked program aimed at helping innovative Kickstarter campaigners reach their funding goals and skip ahead to the celebration.

The #BelaireBacked campaign will support self-made startups by offering funding to select Kickstarter projects, along with promotion of each backed project on Luc Belaire’s digital properties, ensuring continued momentum into 2016. The program allows #BelaireBacked companies to accelerate product development and to celebrate with a massive 15-Liter “Nebuchadnezzar” bottle of Luc Belaire sparkling wine, which they will receive upon being funded.

As an independent, family-owned-and-operated company in an industry of corporate giants, Luc Belaire understands the challenges of being an entrepreneur and the importance of innovation. “We believe in the power of a great idea,” says Brett Berish, President & CEO of Luc Belaire. “We’re excited to support creative projects and the people behind them who are determined to make their dreams a reality. We’ve been there too!”

To date, Luc Belaire has backed six Kickstarter campaigns with $25,000 in funding, including Haize, a minimalist bike navigation device, Atlas C57, a water-submersible carbon flashlight, “NWHL: History Begins,” an illuminating documentary on women’s hockey, The Unsplash Book, an open book featuring photos, essays and art with contributors receiving a percentage of all profits, Pixel Vision, a handmade portable game system, and Blackout, a virtual reality film. Luc Belaire is actively searching for additional Kickstarter campaigns to fund into 2016.

You can read more about #BelaireBacked here.

The post Luc Belaire Launches #BelaireBacked Program to Help Kickstarter Campaigners Skip to the Celebration appeared first on Kill Screen.

How Jane Ng turned the real world into Firewatch

This article is part of Issue 8.5, a digital zine available to Kill Screen’s print subscribers. Read more about it here and get a copy yourself by subscribing to our soon-to-be-relaunched print magazine.

///

When an architect drafts a design, they dream big. And where there’s an architect, there’s a craftsman—the person who sits down to bring the concept to life. At San Francisco-based independent game studio Campo Santo, that craftsman is 13-year industry veteran Jane Ng. But instead of fully-realizing buildings, she realizes game art, most recently that of the impeccably stylized Firewatch. “I’m like the builder that comes in and says, ‘I can actually build your building,’” Ng told me over mint-infused coffee in the warehouse-filled SOMA district in San Francisco. “And I really enjoy figuring out how to make that kind of thing.”

Humor and spirit whisk our conversation through Ng’s deep history (she even jokes at one point that she’s probably the “oldest” person working at Campo Santo, citing the high burnout rate in the industry). She dresses professionally—certainly not abiding to the lazy hoodie-clad tech culture of San Francisco startups—but not in a stuffy manner. Ng exudes an air of a deserved calm that comes from the finality of releasing Firewatch after nearly three years in development.

“I don’t feel as much of an ‘artist’ as people say what the word artist means”

While she is an artist, Ng doesn’t discern herself as one in the traditional sense. Instead of collecting paintings and a litany of favorite artists, she chases life experiences, or more specifically, non-videogame related hobbies. Her job is to bring other artists’ art to life, like a true craftsman. “I think it’s something that people don’t really recognize in a lot of production art stuff is that I [may] call myself an artist, but really I don’t feel as much of an ‘artist’ as people say what the word artist means,” she explained.

Ng says her initial leap into videogames was “kind of like an accidental thing.” She grew up in Hong Kong before moving to the United States and studying engineering. As a self-described “inbetween person” interested in both art and engineering, Ng decided to explore the field of visual effects. “I always played games as a kid,” said Ng. “But it was just not one of those things you never thought about as a career.” In her visual effects studies, Ng landed an internship at her mentor’s “garage”-like game company, Ronin Entertainment. After graduating, Ng stayed at Ronin, until it eventually “went away” and she moved to EA.

At EA, Ng worked as an environment artist on Return of the King (2003) and a senior artist on Spore (2007). “I think when you stay at a big company, they do have a lot more specializations,” said Ng of her experiences at the large company. “The system makes you go, ‘Oh you’re very good at this,’ so there’s always a need for people who are very specialized, and you end up feeling very specialized. [It’s] very narrowing.” In late 2007, Ng left EA to join Double Fine Productions. During her six year stint at Double Fine, Ng worked on numerous games, from environment art on the delightful Russian-doll-inspired Stacking (2011) to lead artist on Ron Gilbert’s The Cave (2013). Ng recalls her time at Double Fine fondly, even when she was hit with the most categorically mundane of tasks, like optimizing The Cave for mobile. “For a lot of people, that would be like the most boring thing,” said Ng. “But I actually really enjoyed it on a technical level.”

Ng’s moved from big, to medium, to small studios throughout her career. “I’m glad I’ve sort of had the whole range,” she said. “For me at least, I have the luxury of not so much choosing the company, but more I know that this company or this group is doing this project that I’m very interested in. And it just so happens to be smaller.” After her time at Double Fine, Ng changed studios again, this time to the 10-person Campo Santo, where she worked as the solo 3D environment artist on Firewatch. “Being in a small company is almost harder, because more of it is on you,” she said. “I think the thing is that after 13 or 15 years, depending on when you start counting, after that long, I finally feel like I’m only now, or two years ago, even capable of thinking that I can do something like Firewatch.”

On Campo Santo’s Firewatch, Ng worked as an artist alongside prolific graphic designer Olly Moss, his first venture into game development, a stark contrast to Ng’s decade-plus of experience in games. “I think people who have done videogames a lot tend to be very aware. Like I’m very aware of production challenges, and my natural tendency is to [avoid] that kind of thing,” explained Ng. “Olly has that sort of outsider, fresh look on things since [game development is] very recent with him. There [are] some people who when you work with them in visual development, they want a hundred percent of what they propose to be in the game. But Olly’s not like that, he proposes a sensibility, we try to push as close to it as possible.” The end result is the distinct painterly look of Firewatch, and its perfectly hued, wondrous recreations of the Wyoming wilderness. “It’s nice that [our] inspiration comes up from [a] non-videogame-y canon thing.”

She’s the realistic, practical side of the dreamer

During a panel at the Game Developer’s Conference this past March, Ng led a discussion entitled “Making the Art of Firewatch,” about building the hyper-stylized forests of the game within development tool Unity. Ng’s technical acumen was on display in a talk full of “scenefiles” and other Unity jargon. I found myself enamored by Ng’s process, and the behind-the-scenes aspects of environmental design. Like how foliage only flows when the wind blows its way; the way the game’s lush trees act as barriers until the eventual fire in the woods slowly eats away at them as the game progresses, thus unlocking new areas. As Ng noted in the panel, a game world itself must facilitate story progression, and Firewatch’s does.

Despite having “artist” in her job description, Ng shies away from identifying herself as such—at least in the classic ‘artist that loves art’ sense. “I’m really terrible with names, like I don’t know who designed what, or who’s my favorite painter or whatever,” said Ng. “I actually am very much not that kind of person, which I think may be surprising for some people. For me personally, I really like working with people with a very strong sense of personal direction and I just like to implement the thing that they do.” Like a craftsman to an architect, Ng realizes the art of others. She’s the realistic, practical side of the dreamer.

However, Ng’s technical art isn’t entirely reliant on her colleagues’ artistic visions. Her inspirations, instead of coming from other art, blossom from the most grounded of experiences: having an interesting life. “I like cooking. I like travelling, I wanna make sure I do other things [besides videogames],” explained Ng. “It’s hard to quantify, like how does hiking really inform your art, but really, well obviously, you never know if you have to make a forest. That kind of stuff, just gathering a lot of interesting experiences I think is more personally important to me, [rather] than going out to museums.”

In spite of her busy career, Ng recalls no low points in terms of projects she’s worked on. “I’ve never had to go, ‘Oh this is just a job job,’ so I have to like, suffer through or anything,” said Ng. “Maybe that’s just a survival mechanism. But I’ve really enjoyed most, if not all, the projects I’ve had to do.” In the coming year, Ng anticipates a well-deserved ‘break’ of sorts—“my next project,” she said of her upcoming parental leave, “is to ship this baby.”

To read more of Issue 8.5, be sure to sign up to become a subscriber to our redesigned print magazine.

The post How Jane Ng turned the real world into Firewatch appeared first on Kill Screen.

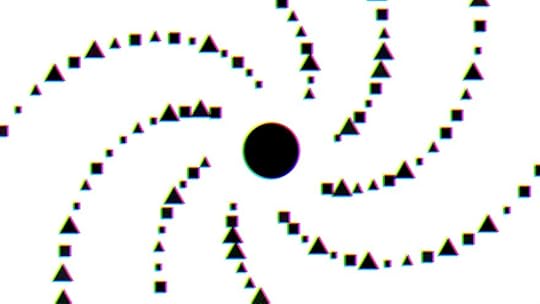

Lone Light teases out the complex symbiosis of light and shadow

Hessamoddin Sharifpour’s upcoming game Lone Light draws its puzzles from the timeless dance between light and shadow, telling the story of a lone light finding its way through the cosmos. Sharifpour is an Iranian programmer living in Toronto; come September, he’ll be attending the University of Toronto to study computer science. At 19, he is already the recipient of two awards—Best Idea and Jury’s Special Choice—from the 2014 Iranian Indie Game Developers Festival, as well as nominations for Best Indie Game of the Year and Best Design.

there will also be hints of evolving cosmologies

This early recognition for his hastily made 2013 prototype encouraged Sharifpour to pursue the idea further, though he decided to gain more experience by first working on a handful of smaller games over the last couple years. “I actually came up with the initial concept when I was 16,” says Sharifpour. “I was playing around with the Construct Classic engine, and came up with the idea when trying out the program’s light tools.” He finished the prototype in just two weeks and then uploaded it to Game Jolt. His original build of the game was “poorly designed” and “really difficult,” however—the result of an experiment that merely gestured toward the essence of the project.

A month ago, Sharifpour submitted a more purposeful, more sophisticated version of the game to Steam Greenlight, where it was greenlit within the first 12 days. At the moment, he’s raising funds on Indiegogo to help pay for audio design and publishing costs, with the aim of releasing Lone Light on Steam and Xbox One in late summer.

The game’s shadow-play focus, Sharifpour says, was inspired by some mixture of world philosophy and the kinds of intricate, puzzle-driven games that drove him to learn programming and game design in the first place: titles like World of Goo (2008), Machinarium (2009), and Braid (2008). Compared with his initial prototype, he intends to provide a more accessible experience by gradually teaching the player to find the light source using the surrounding shadows. But, in the course of the game’s level progression, he says, there will also be hints of evolving cosmologies, and various notions about light and dark from throughout the history of astronomy.

With a month to reach its funding goal on Indiegogo, Lone Light is slated for release on Steam and Xbox later this year.

The post Lone Light teases out the complex symbiosis of light and shadow appeared first on Kill Screen.

Dota 2 might be nearing its Moneyball moment

In one of the most famous single season performances in Major League Baseball history, the 2002 Oakland Athletics won a league-topping 105 games on a paltry $33 million budget. Their secret? Sabermetrics—that is, the use of statistical analysis, rather than subjective judgement, to evaluate players’ relative strengths and weaknesses. The value of this kind of analysis is rather self-evident now, but, in 2002, the notion that the right statistics were more reliable than the best scouts was heresy. Even today, some remain wary of teams that use sabermetrics. As the old timers say, they’re not playing baseball; they’re playing moneyball.

Moneyball (2003), of course, is the name of Michael Lewis’ famous account of that fated season. One of the book’s major, if often implicit, themes is figuring out just how much of the human body’s performance can be neatly quantified and calculated in advance of being fed into a statistical model (what would Foucault have said about biopower and Moneyball?). In esports, though, this question seems rather beside the point: competitive videogames do not need to be made quantifiable because they are always already rooted in quantification. For obvious reasons, sabermetrics (or something like it) in esports don’t have the same kind of narrative, revenge-of-the-nerds-type schtick that gave Moneyball its zing, but it’s worth revisiting the book’s central premise in the context of esports: just how much can statistical analysis improve a team’s performance?

the analyst offers a deliberately narrow point of view

On this point, the current state of the analyst in Dota 2 (2013) is an object lesson. Two weekends ago, 16 teams gathered in Manila, Philippines for the Manila Major, one of the largest professional Dota 2 tournaments of the year. Roughly half of the teams competing brought a dedicated analyst with them, a significant increase from even a year ago. Distinct from a team’s coach, who often is or was a professional player and is tasked with making high-level strategic decisions, the analyst offers a deliberately narrow point of view. As Murielle “Kipspul” Huisman, first-time analyst for the Malaysian Dota 2 team, Fnatic, notes, “a coach is basically the team’s sixth player… an analyst’s task, on the other hand, is to equip the players with the information they need to do battle.”

That’s theory, at least. Here, in her words, is Huisman’s craft in practice:

“Let’s take Fnatic’s upper bracket win against LGD Gaming! During my research, I noticed a ward that LGD never managed to find and deward. [That ward] worked for us too. I also knew one of LGD’s signature smoke [of deceit, which confers temporary invisibility on the user] timings and showed the players [on Fnatic]. Lo and behold, LGD smoked during that exact window and we dodged their attack.”

These are modest strategic advantages, but, over time and in the aggregate, they can convert a close game into a win. In the early days of professional Dota 2 competition, this kind of research was by default the responsibility of players, and especially a team’s captain. But as professional Dota 2 has grown and teams have become better-funded and the competition more intense, the means and need for a dedicated analyst have slowly brought the position into being. As another prominent analyst, Trent “MotPax” MacKenzie, who works with the Euro-American compLexity Gaming, recalls, “My first talk with [team captain] Swindelz came down to: ‘we need to get better at the game still, mechanically etc. We don’t have time to research all these other teams.’”

Though Huisman thinks that every team will eventually employ an analyst, at the moment, not every team is convinced that an analyst is worth the expense (there’s no one formula for compensation, but Huisman notes that she gets a flat fee plus a performance-based bonus, while MacKenzie is paid by the hour). In some ways, their skepticism might be well-founded: at the Manila Major, you’d be hard pressed to find any real correlation between a team’s placement and whether or not they brought an analyst with them. Huisman’s Fnatic took a respectable fifth place, while compLexity, despite the guidance of MacKenzie, who is widely considered to be one of the best in the business, was among the first teams eliminated. At the same time, neither of the teams who made it to the grand finals, OG and Team Liquid, used a dedicated analyst.

There’s a significant dissonance, then, between the plainly beneficial information an analyst can offer and the ability of teams to transmute that information into victory. The origin of this incongruity isn’t hard to identify: Dota 2 is an immensely complex game and over the course of a typical match, players will make thousands of in-game decisions in an extremely fluid environment. So, by necessity, there’s only so much analyst can provide useful information about (Huisman notes that it’s “very easy to overload a team with information and make them less effective instead of empowering them.”) What’s more, the massive number of decisions made by players in an extremely dynamic game often make it hard to know which decisions were, in fact, the most significant. Superior information is never a bad thing, of course, but neither is superior execution, preparation, or brute individual skill. Would Fnatic have actually lost to LGD if Huisman hadn’t identified that smoke timing? Or did this slight advantage combine with many others to eventually yield a victory? Perhaps it was utterly inconsequential? And maybe it was, in fact, a singular, game-winning play—those sometimes happen too.

the information they provide helps produce the conditions of opportunity

But here’s the thing: in different versions of this same match, it could have been any of these, which is part of what makes Dota 2 so thrilling to watch and challenging to analyze. What this speaks to, in other words, is the importance of thinking not just about causality in Dota 2, but also conditionality. Consider this: it’s relatively uncontroversial to say that, under the right circumstances, Fnatic’s received knowledge of LGD’s smoke timing could have been a game-changing moment. Under certain circumstances, Fnatic might not have dodged the attack, but confronted it directly, setting up a (potentially) game-winning fight. Yet the circumstances under which this would have been the “right” decision are based on a huge array of factors, from the gold and experience differential, both teams’ item timings, the status of their cooldowns, the relative strength of their heroes at that moment in the game, lane equilibrium, and… well, you get the idea. My point regarding the analyst is that the information they provide helps produce the conditions of opportunity; determining the best response to those conditions is a much trickier question, better asked (and answered) in the moment by the team itself.

One reason sabermetrics has caught on in baseball much more so than any other professional sport is the length of its professional regular season—162 games, compared to 16 in the NFL. Baseball is notoriously stable—a good team might only win 60 percent of its games—and so necessitates a very long season to determine what teams are, in fact, better (compare this to Cam Newton’s 2015/16 Carolina Panthers, who, at 15-1, won over 90 percent of their games, a percentage that’s simply unthinkable in baseball). One might make the argument that stats, for better or worse, are more useful in baseball because it’s substantially less dynamic than, say, the systematic chaos of football—simply put, there are fewer variables in play at a given moment, and, as a result, each data point can matter for more. But, on a somewhat more subtle level, the length of the baseball season means there are more chances for each data point to matter.

So, too, in Dota 2. There’s little doubt that the right piece of information can tip the balance of a game, even if in most games it’s impossible to know for sure. Let’s say that, in one out of 25 games, Huisman’s sneaky ward really does determine victory or defeat; perhaps in 10 of those games, it has no tangible effect, and in the remaining 14, it’s impossible to know for sure. Those aren’t great odds, but, eventually, the presence of a competent analyst will make possible victories that wouldn’t otherwise be. The question is whether or not this happens often enough to make a difference, especially because it’s possible to be eliminated from a Dota 2 Major tournament in as few as five games (the fate compLexity suffered at Manila). The strongest possible argument against the analyst is simply that bits of game-changing information are simply too infrequent to be of much practical use. Maybe there is really no such thing as Moneyball in Dota 2.

But by that logic, we should also be wary of the “the teams with analysts didn’t do any better at the Manila Major” for a familiar statistical reason: there simply aren’t enough data points to make that judgement well. A more telling evaluation of the analyst’s efficacy would track a team over many, many games through multiple patches and metagames. And, in fact, last weekend, both Huisman and MacKenzie reprised their analytic roles in Fnatic and compLexity at ESL Frankfurt 2016, notching another half-dozen or so games (though neither team did especially well).

So can statistical analysis improve a team’s performance? The most frustrating answer is also the most truthful: maybe, sometimes, it depends. Occasionally, the stars align and a single ward can make all the difference.

The post Dota 2 might be nearing its Moneyball moment appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kologeon, the new roguelike-like-like for you to marvel at

The term “roguelike” was originally derived from the game Rogue (1980), a dungeon crawler that popularized procedurally generated levels and permadeath. Rogue spawned an entire genre of likeminded games. In the 2000s, game makers lifted inspiration from old roguelikes to craft wholly new generated experiences. If Derek Yu’s cult classic Spelunky (2008) was one of the first roguelike-like games to fiddle with the rules of procedurally generated levels and the notion of permadeath, then perhaps ChillCrow’s impending Kologeon is a fitting step forward, a roguelike-like-like.

Resurrection retains a sense of progression within the game’s world

On the campaign page for the recently launched Kickstarter, the developers of Kologeon insist that the game is not a roguelike, but something entirely different (yeah, right). In the in-development action-adventure game, the player is an “immortal soul” where death is still a setback, but only a minor one. Rather than starting from the top of a new level and losing all progress upon defeat, death in Kologeon is necessitated as resurrection within a new dimension. Upon respawn the player is still setback, but retains a sense of progression within the game’s world, wherein other roguelike-likes that might be absent.

Stylistically, the game resembles other beautifully pixelated action adventures, like Hyper Light Drifter, the recently released action-RPG from Heart Machine. But where Hyper Light Drifter coasted on its colorful yet often desolate environments, Kologeon’s aesthetic is far more grim. Demons and spirits haunt all the dark environments the player battles across, the color scheme notably brown, black, with hints of blue shimmering through.

“We always wanted to create something dark, abstruse, fast paced and mysterious where your path is unknown as you journey into a creation formed by dreams and nightmares,” writes the team at ChillCrow in their Kickstarter pitch. “Where the whole game is like a one big journey with no hubs to return to.” In Kologeon, everything is permanent. Progress and action are a mainstay, and don’t regenerate, as the levels do. Progress can’t be lost because as an immortal soul, the player’s just continuing their journey, just on a different path from the one before it.

You have until July 8th to back Kologeon on Kickstarter to make all your roguelike-like-like dreams a reality. It plans to be released for PC, Mac, and Linux in November 2017.

The post Kologeon, the new roguelike-like-like for you to marvel at appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers