Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 102

June 22, 2016

7 Independent Games Best Played on Big Screens

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

Advances in technology lead to bigger, shinier games each year, but outside the mainstream flows a river of creative and entertaining independent games that play well across a variety of devices and screen sizes.

Many small studios use innovative design techniques to create incredible adventures that rival games from bigger studios. They commonly deliver gorgeous pixel and 2D art without requiring a high-end computer processor and graphic chips. That means these games work across different devices, including hardware like the Intel Compute Stick, a tiny PC that plugs into TVs and monitors using HDMI.

A feast for the eyes enjoyed best on the big screen

It’s quick and easy to grab a smartphone, tablet or laptop and dive into bejeweled remixes like Beglitched or terrifying, soundtrack-driven zombie titles like Noct, but playing these games on a large living room TV screen intensifies and socializes the experience.

Car racing in Drift Stage, exploring fictional worlds in Night in the Woods or masterminding strategies in Overland becomes gripping entertainment for a group or friends or family. The indie games have a light-weight design, making them the ticket for easily turning game night into a house party almost anywhere.

Rain World

In the visually striking platformer Rain World, players dive into the mysterious ruins of a fallen civilization. They must evade the bizarre predators of its broken ecosystem while inhabiting an adorable creature known only as “slugcat.”

An indie darling with a cult following online, composer James Primate called the process of creating Rain World a “constant collaboration with the Internet.” The developers often incorporate community feedback, so fans should keep an eye out for their own ideas and suggestions.

The dynamic approach to pixel art and enemy AI brings the game world to life. A feast for the eyes enjoyed best on the big screen, friends can help each other outsmart the intelligent predators who react differently in every playthrough. Primate even teased a robust couch co-operative mode, where up to four players can “explore the huge game world together!”

Beglitched

The “cyberpink” game Beglitched blends witchcraft with the world of computing into one hilarious experience. Breathing new life into the classic Bejeweled format, it sends players on a mission to “debug” mysterious coding errors by solving tile-matching puzzles.

In the game’s fiction, programming abilities are seen as magical powers. Players embark on a hacking journey as an apprentice to the craft, and they must piece together a larger secret through subtle hints.

“The narrative has an emphasis on personal insecurity and identity”

“The narrative has an emphasis on personal insecurity and identity, and there’s sort of a feeling of exploring a lonely person’s internal life,” said programmer Alec Thomson.

A crowd-pleaser for groups that appreciate tech humor, actually playing the game is anything but lonely.

Noct

Rendered in black and white, this multiplayer horror game draws players in with stark visuals and a haunting soundtrack created with help from Nine Inch Nails guitarist Robin Finck.

Creator Chris Eskins wondered what a zombie game would look like if it only used thermal imaging. The result: an atmosphere that rides the tension between claustrophobia and isolation.

The horror of Noct derives less from jump-scares and more from a sense of shared dread amped up by group play. The eerie soundtrack begs to be blasted through the surround sound of a home theater, ensuring friends will have to dare each other to play.

Night in the Woods

Contrary to its spooky name, Night in the Woods offers a whimsical tale about a casually dressed cat trying to get home. The world resembles an eccentric children’s book, filled with smiling animals and minimalist shapes.

A narrative-driven game ideal for fans of Telltale, players impact the story through dialogue choices. The subtle changes give Night in the Woods good replay value, rewarding players who watch each other’s tales unfold in a variety of different ways.

a whimsical tale about a casually dressed cat trying to get home

“Night in the Woods is very intimate, but at game conventions, we see lots of people sitting close to each other, reading along and laughing at the jokes together,” said Adam Saltsman of Finji, the small publisher helping to finish the game.

Overland

Another title produced by Finji, the survival game Overland leans more toward strategy and tactics than story. Players use scarce resources and time management to traverse a desolate landscape filled with minimalist art and innumerable threats.

Playing together and putting several minds to the task can only increase the chances of survival. Saltsman equates the experience of playing Overland together to “a board game, with a lot of arguing over what to do next and why, and who to abandon and who to save, and what risk to take next.”

Gang Beasts

Double Fine’s clay-inspired fighting game Gang Beasts is less a tactical battle of wills than a wrestling match between oversized toddlers. Perfect as a party game, it turns living rooms into the virtual version of a mud-wrestling match.

Playing as multi-colored humanoid blobs that knock each other around in factories or off skyscrapers exemplifies why this competitive title encourages silliness above all else.

less a tactical battle of wills than a wrestling match between oversized toddlers

The game is set in the fictional metropolis of Beef City, and it rewards ridiculous antics while not punishing players who flout the rules.

Perfect for a game night with those friends who miss the days of Twister!, Gang Beasts promises to make everyone feel stupid enough to enjoy themselves.

Drift Stage

Classic racing games like Pole Position have been haunting arcades, bargain bins and retro compilation videos for years. Drift Stage modernizes that ‘80s classic, making virtual racing feel more glorious than ever.

The game’s chic pastels and flashy drift physics encourage flashier and flashier moves.

“Modern games don’t really lend themselves to the sort of multiplayer atmosphere I grew up with,” said Charles Blanchard, the designer behind Drift Stage’s art.

“You can’t have a good arcade racing game without split screen multiplayer. Being able to race your friends, on your couch—with no lag or any possible excuse beyond having a crappy 3rd party controller—results in the best kind of competitive play.”

Editor’s note: Since these games have yet to be released, the writer could not test them all on the Intel Compute Stick. An additional USB hub will be needed to play local multiplayer.

The post 7 Independent Games Best Played on Big Screens appeared first on Kill Screen.

Taxis are now being guided by the same tech used in city-building games

A city-building game, no matter how wild it looks, is an economic model. Everything can be mapped. Everything is built on a substrate designed to facilitate bean counting. Everything is fundamentally knowable. There are surprises for the eye, but nothing is truly surprising.

The city-building game, in other words, is every business’s dream. A centrally controlled, fully quantifiable universe would grant considerable powers to a large corporation. That is why it’s no big surprise that the British startup Immense Simulations is using a simulation technology called Improbable to solve taxi dispatch problems. These are, in effect, two sides of the same coin.

Using Improbable, the company created a complex recreation of Manchester, England, with its tangle of roads. “Improbable’s technology allows us to run city-scale scenario simulations with a level of detail not previously possible,” says Immense Simulations CEO Robin North told MIT Technology Review. “We can represent individual travelers and vehicle operations and their interactions within a living city.”

To understand why this matters, it’s worth thinking about what traditional maps are good for and what they can and cannot do. A map—the kind you unfold on a table or over a steering wheel and then fail at folding back up—is good for big picture thinking. It can show you the way from point A to point B if you draw that line in pen. The ends of that line, mind you are somewhat rounded from being drawn in pen. They have too much ink from where your hand paused. The map will get you close enough to your real destination, but it will not solve the smaller questions about what to do in the final dozen feet of your journey—at least not unless you stick your nose right up against the map.

In most cases, that is good enough. You bumble about for the last few feet trying to figure out where your destination is, and then come up with an elegant solution. But what if you’re the head of a taxi company, say, and every second counts—for you, your drivers, and your passengers. All of a sudden, traditional approaches to mapping don’t really cut it. Small routing questions, like ensuring that a driver approaches on the correct side of the street or is quickly facing in the correct direction for their next fare, matter. In a world where everyone can draw a line in sharpie from point A to point B (or do the equivalent with cheap, dash-mounted GPS), competitive advantage can only stem from a deeper knowledge of space.

We don’t yet map space like driverless cars, but this is the transitional phase

New approaches to transit (read: Uber et al) require a different understanding of the city. They are less about the bulk of routes than systemic knowledge of urban events and microscopic details at both ends of a trip. These, incidentally, are the points where traditional forms of mapping fail and where simulations excel. As ride-share companies transform—for better and for worse—taxi dispatch into a ruthlessly efficient economic system, they need a model of the city that maps onto this outlook. Sim City is admittedly more fun than Travis Kalanick’s plans for the future, but in both cases the city is treated as a data-rich system atop which interesting infrastructure can be built.

Eventually, mapping can come to reinvent a city. Earlier this week, the GPS manufacturer Waze announced that it would cut down on left turns in LA for safety reasons. In a way, this represents a mainstream adaption of UPS dispatch’s approach of ordering three right turns instead of a left. But Waze may go further. Per CBS: “The company is now working on what could be a controversial next step, a new feature in that country to alert drivers about routes through high-crime areas.” Maps can look like destiny or they can create confirmation bias; when a map tells you to avoid a neighborhood what are the chances it will make it off the blacklist? This is all the more the case when thinking about taxi dispatching, which, at present, is really a stopgap for driverless cars. Mapping and simulating every last inch of the city turns the driver into an aspiring robot.

We don’t yet map space like driverless cars, but this is the transitional phase. It is only fitting, then, that Immense Simulations is bridging different forms of urban understanding. The city-builder isn’t quite real, but it is an urban environment. The dispatcher’s simulated city, likewise, isn’t reality as we tend to experience but it is nonetheless an urban environment. These are all realities in a sense, but it is not yet clear exactly which one we are living in.

The post Taxis are now being guided by the same tech used in city-building games appeared first on Kill Screen.

The videogame that dared to question the War on Terror

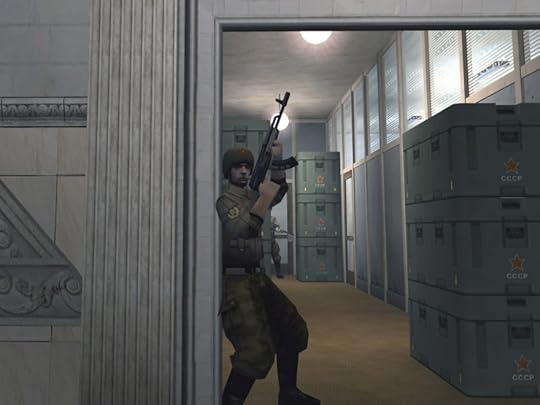

If we can associate genres and aesthetics with film-makers (John Woo and action movies; Stanley Kubrick and deep focus) IO Interactive, especially in its prime between 2002 and 2007, was a game-maker defined by concerns about player agency. By constantly placing her in restrictive and alien environments, the Hitman series challenged the player’s typical experience of casual and unbridled progression. Kane and Lynch: Dead Men (2007), starring two legitimately unpleasant characters, undercut the prototypical videogame hero narrative—rather than saving the world, cast as a selfish villain, the player committed selfish acts and with selfish purpose.

“My name’s John Ford and I make Westerns,” once stated the director whose movies Stagecoach (1939) and The Searchers (1956) helped define a genre. It would have been less eloquent, and much less concise, but at the end of the 2000s, IO could have made a similar affirmation: “We’re IO Interactive and we want players to doubt themselves.” Of that intent, there is no better statement than Freedom Fighters (2003).

Rather than subvert the typical experiences of progression and control wholesale, Freedom Fighters hones in on videogames’ favorite tool, the one with which players most commonly exercise their agency: the gun. In a shooting game, the act of aiming and firing a weapon, usually, is made as simple and as clean as possible. One button to aim. One button to fire. One button to reload. If game-makers are concerned that violence in games has become, or always has been, blasé, they could do worse than re-evaluating their representation of firearms. That weapons can be operated and discharged so thoughtlessly in videogames is a root cause of their casual, indifferent treatment of violence.

In Freedom Fighters, however, at least in its console form, aiming is perennially difficult. Rather than one of the controller’s shoulder buttons—L1 or L2, for example—the aim function is mapped to the right analogue stick, the same stick used to move the character. On paper, it sounds like a minor, perhaps undetectable difference. In practice, aiming in Freedom Fighters is always inconvenient. When the aim function is attached to the same stick used to move the character, aiming and moving at the same time, something which players are accustomed to doing almost unconsciously, becomes slow and arduous. The aiming reticule itself is unreliable. One may place it on an enemy soldier’s head, and fire, only to see the bullets hit the wall behind him. Put simply, guns in Freedom Fighters do not fire straight—a string of clean, successful kills is almost impossible to perform, and enemies don’t die from well-placed shots but a rain of abortive, inaccurate fire.

The Player’s own tools are not totally at her command.

It’s a tiny conceit, making the player aim with this button rather than that one, but with shooting in videogames so uniformly refined, even the slightest change can create a sense of unease. In Freedom Fighters, for once, the player is not a master of her weapon. It does not always do what she expects. She cannot kill with it, efficiently, 100 percent of the time. And suitably, she is playing not as a professional soldier but the freedom fighter. Christopher Stone, the lead character, is a plumber from New York City—his experience with AK-47s, one can presume, is limited, and so the weapon, for both him and the player, is unwieldy. This is still a game where generic enemies are killed, en masse, but where shooters typically permit players to feel wholly capable, and as if they are controlling similarly capable characters, Freedom Fighters subtly implies that even the player’s own tools are not totally at her command. Shooting is less predictable. As a result, it is performed less apathetically. Without any blood effects or hamstrung moralizing, a la Spec Ops: The Line (2012), Freedom Fighters encourages players to feel ill at ease during gunfights. Mapping aim to R3 is a simple flourish, deftly undercutting the player’s expected sense of absolute power.

As for Stone, he’s very much the stereotypical videogame hero. In its tackiest moments, Freedom Fighters sends Stone on a one-man mission to avenge his dead brother, and channels Mel Gibson’s Braveheart (1995) to lend him babyfaced charisma. But in other moments, he’s damaged—or at least physically affected—in a way that’s rare for videogame men. As Freedom Fighters progresses (the game is set in three acts: summer, autumn, and winter) Stone’s appearance grows more ragged. At the game’s beginning, he has short, cropped hair and tidy clean clothes. By the end, he’s unshaven, long-haired, and dressed in rags.

I’ve written before about the importance of depicting physical wounds on videogame characters—again, if violence in games is passé, it’s because games neglect to depict the consequences, be they big or small, of violence. Game heroes, regardless of their ordeals, tend to emerge unscathed. Nathan Drake’s hair remains perfect. Evie Frye’s dress stays unruffled. Master Chief remains safely encased inside his armor. Dirt and blood effects have changed this a little—I enjoy how Max bleeds and sweats in Max Payne 3 (2012)—but largely, today, and especially in 2003 when Freedom Fighters launched, the game hero was an impervious, implacable statue, an idol, in the pejorative sense. Where Kane and Lynch undermined the player’s sense of being a videogame hero by casting her as overtly unpleasant characters, Freedom Fighters does it by implying Stone’s vulnerability. As his battle against the Russian occupying forces becomes more brutal, his appearance grows more tired, more worn. Like switching the aim button to R3, it’s a minor device, but when compared to the men and women we’re used to playing in games, any suggestion of physical deterioration—any implication that fighting and killing is changing a character somehow—is a stark contrast. Stone is a hero, but unlike his videogame contemporaries, he inhabits that role at a personal cost.

But unlike his videogame contemporaries, he inhabits that role at a personal cost

Freedom Fighters doesn’t stop at challenging players’ sense of agency in videogames—it asks them to question their opinions on, what was at the time and in a broader sense remains today, an urgent real-world issue. It was released in September, 2003, six months after the bombing of al-Dora, which signaled the beginning of America’s ground invasion of Iraq. The day after the bombing, on March 20th, 2003, Gallup reported that 76 percent of interviewed Americans were in favor of the war in Iraq. Eight years later, as the final US troops left Iraq—and after more than 120,000 people had been killed—CNN reported that 68 percent of Americans opposed the war. 78 percent agreed that all troops should be removed, and the same amount believed that the US, if it remained in Iraq any longer, would not be able to achieve any more of its objectives. 22 percent believed America had succeeded at “most” of its goals.

Freedom Fighters didn’t predict a drop off of public support for the invasion of Iraq, but it certainly invited its players to doubt the war’s legitimacy—to empathize, perhaps more than the political rhetoric of the time would have encouraged, with Iraq’s people. Essentially, the game flipped reality on its head. In Freedom Fighters, it is Russia not America that is the world’s dominant superpower; America, not Iraq, that is under occupation. In the game’s opening level, Stone is forced to flee a cosy apartment by an attacking helicopter—he is literally driven from his home, and then forced to fight. The destroyed architecture you explore does not belong to the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty, or any of New York’s most famous landmarks. The levels are called “school,” “movie theater,” “hotel.” The destruction, rather than played for spectacle or cheap, sentimental appeal, is focused on more intimate locations, places familiar to people’s’ daily lives. As the US occupation hit full stride, Freedom Fighters asked its players “how would you feel is this were happening to you?” Its undermining of player agency in regards to mechanics and its player character is tied to this question.

Letting videogame players constantly be in control—to always hold the power—helps them to feel safe, comfortable, validated. Similarly, when George Bush asserted that “you can’t distinguish between Al Qaeda and Saddam [Hussein] when you talk about the war on terror,” it assured the public that their suspicions were correct, their support for war justifiable. Videogames, typically, convince the player of her own agency, her own rightness. The arguments for the war on Iraq, as presented in 2003, had the same effect on America. Freedom Fighters challenges both of these compacts, inviting the player to feel vulnerable and uncertain of herself and the American public to doubt its convictions about entering war. Where IO Interactive had previously subverted players’ mechanical agency in Hitman and would go on to overtly question their heroic state in Kane and Lynch, in Freedom Fighters the studio combined both and in doing so questioned a sense of self-assuredness its players would have likely had in real life.

The post The videogame that dared to question the War on Terror appeared first on Kill Screen.

June 21, 2016

The hell of finishing a game and having nothing else to do

My grandmother cannot be seen. She is in the room but hardly visible—consumed by the beige. Her gradual decline into camouflage was incidental; the result of years spent sunk in her yellowed sofa, watching afternoon quiz shows and staining the walls with a million cigarettes. “Nan?!” I call out into the void. “Yes?” comes her throaty reply. I sort of see her: all that’s left is a plume of blue-rinsed hair and a set of white dentures hovering like some demon among the brown. This is what retirement looks like.

As with most things in life that are promised to us when we’re older, I am skeptical of retirement. I don’t trust it. This, it seems, is not true for most people. There’s little else that inebriates the imagination of the working person than the dream of retirement. Oh, to be lounged on a sandy beach! To sip margaritas on a cruise! To sit around and do naff all if you so wish! In short: oh, to be free from the exhausting requirements of labor!

Prometheus immediately breaks free from the ropes that tie him down

But, ah, retirement isn’t always what it’s cracked up to be. Not only might you not have the money to afford the freedom you dreamed about, you could have deeper personal problems, such as feeling detached from society, or being daunted by all the possibilities available that you do none of them and sink, like my grandmother, into a mundane routine of nothingness. That is the terrifying prospect we must face—are you sure you want to spend your latter years doing fuck all? Perhaps it’d be better to work until the day you die.

Pippin Barr tempts our thoughts in this dark direction with his latest game. It’s another iteration of his 2012 game Let’s Play: Ancient Greek Punishment (the other version of it being the Art Edition Edition). Where that first game had us play out the endless, cruel punishments of Greek myth forever, this one—which is cleverly titled Let’s Play: Ancient Greek Punishment: Limited Edition—puts a cap on the activities. Sisyphus manages to push the boulder up the mountain and over the other side on his first try. Tantalus is able to reach the fruit on the tree and drink the water beneath him that usually avoids his touch. Prometheus immediately breaks free from the ropes that tie him down on the rock where the eagle is supposed to eat his liver for eternity. You get the idea.

The point here isn’t entirely about liberation and victory. After you have clicked enough times to complete whatever impossible task the mythical entity was supposed to suffer, the game does not end. In fact, there’s no way of escaping the small 2D scene save for refreshing your browser. You are left to wander the pixel art expanse, moving left and right, standing on the spot, sometimes sitting at the edge of a cliff. There is nothing else to do here. The activity has been done. Now what?

to endure boredom and ennui to no end

Barr’s point is to confront us with another kind of terrifying eternity: one in which there is nothing to do. He took the idea from Albert Camus’ 1942 essay The Myth of Sisyphus, in which he proposes that Sisyphus could have been happy while pushing the rock up the slope over and over, because at least he had something to do. He had a struggle to work against, one that was measured and reliable—”His fate belongs to him,” wrote Camus. Without that, Sisyphus would have to endure boredom and ennui to no end, as we do as players of Barr’s game.

There’s a larger point being made here that connects traditional game design with the comforts of labor, too. Think about how people moan about repetitive side quests and grinding and collectibles in videogames, but also how these menial, mostly pointless tasks that only raise numbers provide busywork for the otherwise unoccupied mind. Sure, the old men of Athens would have us use our free time to study the heavens and indulge in philosophical conversation with our peers. But we do not live in Classical Greek society, we live in one that places our worth in the labor we are able to do. We are treated (most unkindly) as machines and we have accepted this.

The Greek underworld’s punishments include “futile and hopeless labor” (as Camus puts it), but most of us already do that and have found small pleasures in it, and so our vision of hell might be better suited to one in which we are given nothing to do at all. We are a people who work, whether it be to pay off a mortgage and save up for retirement, or for those small bursts of achievement and a sense of feeling appreciated, or maybe to contribute to our inflated sense of importance. Our hell is waiting for hours in an airport lounge with no Wi-Fi, no money, and only a small bag full of clothes in our possession.

You can play Let’s Play: Ancient Greek Punishments: Limited Edition in your browser.

The post The hell of finishing a game and having nothing else to do appeared first on Kill Screen.

Here They Lie might be the horror game VR needs

What happens when you combine nightmares, beards, the claustrophobia of VR, and leaving behind AAA development? Apparently, surreal horror games are born. Here They Lie, announced during E3 last week, is a new title for both PlayStation 4 and PlayStation VR, developed by Tangentlemen Studios. The new studio is made up of other industry veterans, some former Call of Duty and Medal of Honor developers, as well as co-creative directors and lead designers Cory Davis (creative director and lead designer for 2012’s Spec Ops: The Line) and Toby Gard (designer of the original 1996 Tomb Raider and the iconic character of Lara Croft).

In an endearingly odd PlayStation Blog post announcing the game and its teaser trailer, Davis described the “conversation” that sparked the inspiration for the eerie Here They Lie. “As we talked, a dark cloud filled the room,” he writes. “I felt like I was sinking… from there it was just flashes.” Then he describes scenes of chopping and blood, himself as Jack from The Shining (1980) while his colleague Gard played Wendy, Jack’s terrified wife. So, yeah, rather than stoically detailing the game and its teaser, Davis took a more intriguing, dreamlike-approach to describing what inspired him and his team to formulate the project.

Here They Lie just sticks to what makes the player uncomfortable

All that aside, in clearer terms, Here They Lie is a psychological horror game that looks like little else. Gone are the jump scares of Outlast (2013) and its impending sequel. Absent is the “horror” that’s supposed to emit from the haunted house in Resident Evil VII: Biohazard’s lackluster, wannabe-P.T. demo. Here They Lie just sticks to what makes the player uncomfortable, resembling the makeup of actual nightmares.

“Unimaginable horrors lurk around every corner, just out of sight, haunting and infecting your mind,” writes Davis on the aforementioned blog. Here They Lie begs the player to feel a looming sense of dread from the off-kilter game and its world’s malevolent inhabitants, rather than relying on unabashed, cheap scares. It’ll probably be hellish to experience in VR, but if our own nightmares are anything to go by, it’ll be possible to withstand. It’ll just take a helluva a lot of courage to do so.

Experience the surreal horrors of Here They Lie when it’s out for PS4 and PSVR in Fall 2016.

The post Here They Lie might be the horror game VR needs appeared first on Kill Screen.

Let us now consider the menswear at E3—2016 edition

We still live in a glorious time for mediocre fashion. Russell Westbrook notwithstanding, all it takes for a man to be deemed a good dresser is baseline competence: if your clothes vaguely fit, you’re stylish. This, incidentally, is the bigotry of low expectations or, to use a trendier term: male privilege.

So, here we are: another year of unimaginative fashion; another year of officialdom-sanctioned apathy under the aegis of “normcore”; another year of E3. Sigh. You can probably see where this is going.

In true Kill Screen fashion, this review will involve scores. Let’s begin.

Here, for your sartorial pleasure, is one Hideo Kojima:

He’s giving the thumbs up and so are we. Everything fits, which is a good start. It all matches, which is easy enough when everything is black. There are, however, some pops of color that prevent this from being a soporific display of competence. The sunglasses are the obvious pick—reflective and blue and about as inscrutable as a VR headset. Though the glasses grab your attention here, the real difference maker is the green wristband, which adds a pleasingly anarchic touch to an otherwise regimented look. This little touch makes up for the otherwise unimaginative shapes.

Score: 9/10

/////

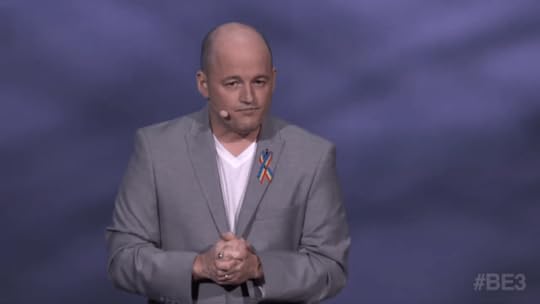

Here, presenting for Bethesda is every dude in every nightclub ever. I’m told his name is Raphael Colantonio, but really there’s no reason to get bogged down in specifics:

You may be sensing a pattern here. Another jacket. Another t-shirt. What, as they ask on Passover, makes this getup different from Kojima’s? For starters, the sleeves are a bit too long. You can see one riding up Colantonio’s hand beyond his wrist even though his arm is bent. The sheen of the jacket also doesn’t work under this lighting; it comes off as grey as opposed to just shiny—an impression not helped by the grey shirt. It’s all just a bit washed out. But the rainbow pin is nice.

Score: 6/10

/////

Moving on:

So many questions present themselves about “We are gamers” as a t-shirt slogan. Was this ever in doubt? Was this ever in doubt at E3, of all places? What is a gamer anyhow? Who is we, in this context? Why did the toasted marshmallow taste like fish?

Score: 2/10

/////

Let’s pick things up a little. Here’s Palmer Luckey of Oculus fame (can you call it fame?):

Ignore the chyron. Palmer Luckey is on the left, though the thought of him in E3’s de rigueur jacket and t-shirt look, instead of an untucked shirt, is the closest any of us have yet to come to virtual reality.

Score: 4/10

/////

Let’s take a break from jackets and re-enter the wonderful world of hoodies with Craig Duncan of Rare:

This is perhaps the most compelling argument yet that one does not simply become Mark Zuckerberg by wearing a hoodie. What fresh hell is this, both short in the arms and wide in the shoulders? Bill Belichick would approve, and that’s never a good sign. Is it zipped? Is it unzipped? Do we really want to see more of that t-shirt anyhow?

Score: 4/10

/////

Back to the jacket/t-shirt category, and back to Bethesda:

That is not a t-shirt; it’s an undershirt.

Score: 3/10

/////

One more for the road:

Note the look of resigned sadness on his face. Note the asymmetrical sweater. It is almost… interesting? Not stunning, but at least a compelling shape, which is shockingly hard to come by at E3. The headphones, well, they’re huge and no matter how many ads Beats bleats, are not fashion. They’re just big. But this is an excellent look for going to the airport. Good enough.

Score: 8/10

/////

BUT WHAT DOES THIS ALL MEAN???

The jacket and t-shirt look never gets old, at least in certain circles. It is unambiguously old, but E3 will never let it die. And fine. Whatever. Wear whatever makes you comfortable. But the striking thing about E3 menswear is that an event that presents all manner of creativity and imagination has so little of it on stage. There is so little dreaming about shapes and textures and color when watching E3 streams—and then there’s the fashion, which has even less. It’s bleak. Competent but bleak. The fashion at E3 doesn’t really happen. It never does. But it’s a metaphor for much of E3, an event of boyish and unimaginative professionalism. At least it’s over until next year?

The post Let us now consider the menswear at E3—2016 edition appeared first on Kill Screen.

Gravity Rush 2’s city turns the player from tourist to traveler

As a word, tourist is often pejorative. Like jogger is to runner, tourist is to traveler. One implies lazy trend-following and a profoundly uncool lack of self-awareness, the other an adventurous outlook and a sense of dynamic movement. You’ll be as hard-pressed to find a self-professed jogger as you will a tourist: we are all travellers now, or at least we like to think so. When it comes to cities, tourism also brings with it a kind of standardization—think of any city guide or map. Tasked with describing those complex organic machines we call cities, they often fall into gross over-simplification, in a method that seems almost like “district as genre.” You can often find “old town,” “downtown,” “entertainment district,” “cultural center” neatly labelled within often disparate and diverse cities, as if each city was simply a variation of a template.

The city of the original Gravity Rush (2012) was crafted from these exact concepts. Built from floating islands of ornate architecture, each district was separated and themed, divided into those recognizable districts with totally different architecture and residents. This felt like an entirely appropriate structure for a game that took its inspiration from the fantastical cities of 1970’s science fiction, casting both the player and protagonist Kat as wide-eyed visitors. Even the game’s beautifully drawn map appeared like a guidebook, marked with sights to see. To fall through its complex structures and climb its towering edifices had all the lightness of being a tourist of the imaginary, gliding across the surface and never going deeper.

However, for Gravity Rush 2, the developers at SIE Japan Studio have begun to take inspiration from more than just the imaginary. Speaking to producer Nick Accordino he explained how the development team was inspired by the cities they visited during a press tour for the original game: “they spent a lot of time in Mexico,” he explained, “they spent a lot of time in South America too.” It was a trip that clearly had some impact, as Accordino points out: “they wanted to incorporate a lot of that culture, a lot of that like South and Central America culture in there. And I think that’s very evident if you see the city.” It’s true that Gravity Rush 2’s city appears to be an entirely more “living” place. A colorful jumble of golden domes and bright parapets, its sun-baked buildings are layered with a litany of signs and adverts. The South and Central American influences don’t feel literal, but more atmospheric, mixed as they are with distinct Asian tones. That influence came from director Keiichiro Toyama, as Accordino explains: “Toyama-san traveled around Asia a lot too, so there’s a lot of like Asian influences on some other parts of the city.” That blend is evident in the cities name, Jirga Para Lhao, a neologism that combines Islamic, Hispanic, and Burmese words.

Gravity Rush 2 aims to invest more believability into its fantastic world

There’s a hint of exoticisim to this combination, but Gravity Rush 2 manages to sidestep such accusations through both its imaginative embellishments of these cultures and a particular new addition to the series: the concept of class. “The first game was kinda split up into four distinct areas of the city, but now we have a city that has lower tiers, higher tiers, and different classes of society in them,” points out Accordino. This change is part of a pursuit for an atmosphere he describes as both “familiar and individual.” It’s a recognizable idea; that cities are as defined by their class divisions as they are by their architectural traits, and suggests that Gravity Rush 2 aims to invest more believability into its fantastic world. “With any society,” points out Accordino, “you have the destitute areas, you have the medium income, and you have the people that are like high society, the aristocrats, right? So, you’re gonna kinda see that reflected a little bit in this game.”

This shift, from guidebook template to a city divided by class, seems to suggest a shift for the player and Kat—from tourist to traveler. While a tourist might be interested only in what they do, focused on their own fulfillment, a traveler might be more interested in how the people of the city live. In Gravity Rush 2 it is particularly interesting this shift might have originated in a similar shift in the developers, their journey transforming them from outsiders looking in, to explorers of unfamiliar streets. However, the idea of a traveler is just as much a performance of identity as that of the tourist, and consequently the difference between the two is thinner than we think. Sure, wander the streets of Paris and you’ll be able to pick the two apart, if only by their lack or possession of selfie-sticks, fanny packs, and sandals over socks. But head to Rajasthan, for example, and you’ll see both tourists and travelers wrapped in local scarves, and sporting ratty kaftans and “blending in.” It was there, among the sand-whipped streets of golden Jaisalmer that a local shop-keeper explained to me how puzzled he was by these “travelers” from rich western countries, “why” he asked me “do they enjoy dressing like poor people?”

Tourism and travelling, then, are explicitly connected to ideas of class. In fact, it is often so-called travelers, for all their superiority, that are the most guilty of exoticisim: the “authenticity” self-proclaimed travelers seek is inextricably tied to poor and working class areas. This is where the “real” city lives, with affluence often considered to be “spoiling” the “character” of a city. This perspective contributes to the “Disneyfication” of cities into theme parks as much as any whistle stop tourist tour. In reality, rudeness, ignorance, and fetishization are universal qualities, we can all possess them; traveler or tourist. As are wonder, openness, and wide-eyed curiosity. Lets hope Gravity Rush 2, in its travels, can find its way to the latter.

Gravity Rush 2 is slated for a 2016 release for PlayStation 4.

This article was based on an interview with Nick Accordino conducted by Clayton Purdom.

The post Gravity Rush 2’s city turns the player from tourist to traveler appeared first on Kill Screen.

Upcoming game asks if isolated dicatorships like North Korea are good or bad

North Korea is upset with Bae. Kenneth Bae, that is.

The American missionary, who was detained in North Korea from 2012 to 2014, has a book out—Not Forgotten: The True Story of My Imprisonment in North Korea—and has been giving interviews about it. This has not pleased his former captors. “As long as Kenneth Bae continues his babbling,” North Korea’s KCNA news agency announced, “we will not proceed with any compromise or negotiations with the United States on the subject of American criminals, and there will certainly not be any such thing as humanitarian action.”

The whole situation is absurd on a number of levels. Perhaps its biggest absurdity is that Bae represents something of a best-case scenario. He got out of North Korea. Suppressed, an upcoming game by Angela He (aka Zephyo), is about the more commonplace struggle to escape a place like North Korea. Whereas Bae at least had the relative advantage of citizenship in another nation, most of the regime’s residents are basically stuck. They can try to escape but they are largely on their own. Those are the stakes of Suppressed, and they are not exactly relaxing.

Heroism is a luxury

The game doesn’t actually take place in North Korea. Per its documentation, it is set in “an isolated, totalitarian nation modelled after North Korea.” But who are we kidding? If it walks like Kim Jong-un and coifs like Kim Jong-un, it’s a game about North Korea. Insofar as the game is about a living nightmare, it is also a dream. The art previewed so far mixes watercolor and crisper influences. Its shadows are sharpest. There are monsters, though it’s easy enough to imagine what they stand for. Suppressed allows enough narrative possibilities for you to be a hero; you can try and help others as you escape. But the game is less about heroism than it is about survival. Heroism is a luxury, and most characters do not have it.

You can find out more about Suppressed on its website. You can also vote for it on Steam Greenlight.

The post Upcoming game asks if isolated dicatorships like North Korea are good or bad appeared first on Kill Screen.

VA-11 Hall-A is how you do modern cyberpunk

“Time to mix drinks and save lives.”

Jill lackadaisically jazzes herself up with this line at the start of every shift, unknowing of just who will waltz through the door. But what I soon find out is that Jill is kinda lost. The 27-year-old bartender resides in a run-down apartment, barely scraping by when it comes to bills, rent, and impulsive buys, like cute posters or a plant. Jill is lost in the same way that her regulars—patrons of the dive bar VA-11 Hall-A (colloquially called “Valhalla”)—are lost. She’s caught within an average life, with the only fulfillment she gets coming from the people she meets through bartending, and in caring for her pet feline Fore.

VA-11 Hall-A takes place in the cyberpunk post-dystopian city, aptly named Glitch City. It’s a city overwrought with crime, grime, hacking, and everything in between. Glitch City, quite simply, isn’t a pleasant place to live. It wouldn’t be outlandish to consider Cowboy Bebop’s (1998) Spike Spiegel resting in a nearby bar, annoyed with bounty hunting and trying to drink a Prairie Oyster in peace. Or the Knight Sabers of Bubblegum Crisis (1991), cruising around town, ready to battle. But for Jill and her two bar-keeping companions—the lovable schmuck Gillian and her ever-chipper boss Dana—Valhalla’s a second home. A departure from the outside abysmal reality. For a lot of its patrons, Valhalla’s an impromptu church, and Jill’s the confession booth.

It is unusual, if fitting, for cyberpunk fiction to focus on someone like Jill. She doesn’t take drugs and she isn’t actively looking to stage a revolt; she’s merely trying to get by. It’s a perspective that allows VA-11 Hall-A to be entirely familiar, yet also in a position to subvert cyberpunk’s typical elbow rests in small but significant ways. Sure, it finds its footing in a bar reminiscent of the hacker-friendly Chatsubo Bar from William Gibson’s famed cyberpunk bible, Neuromancer (1984). And yeah, sometimes the humor in the game doesn’t land—such as in the antics of Jill’s colleagues, or throwing around the jarring modern-day insult “fuckboy”—but it’s nothing too distracting. What defines VA-11 Hall-A more than anything is its negation of a primary hero—the game zeroes in on the folks that would normally fall between the cracks, never to be fleshed out or seen as anything apart from quirky embellishments of Glitch City.

Dorothy’s positive attitude towards sex is also refreshing

VA-11 Hall-A’s city will be familiar to any fan of anime, then, but its flipping of character tropes may be less so (even if they are waifu-prone). For instance, there’s Dorothy, the delightfully cheerful “lilith” (or automaton) who happens to be a sex worker—and has even taken the precaution of installing hidden weaponry to protect herself in the event of being assaulted. Yet, Dorothy’s mostly unfazed by the danger in her work. In fact, she quite enjoys it. Dorothy’s positive attitude towards sex is also refreshing, her sunny demeanor a stark contrast to the “edgy,” distressingly-victimized sex workers seen in other works. She’s got more in common with the sex-crazed Panty from the charming Panty & Stocking with Garterbelt (2010), than with victimized-until-saved-by-brooding-men Alex in Gangsta (2015). In VA-11 Hall-A, sex work is a woman’s choice—not a controlling man’s.

On top of that, the women here aren’t one-note dames to be ogled at—they exist as a rare, mutually-supportive community. Like Alma, the busty, bespectacled hacker who happens to be Jill’s best friend of sorts, always ready to spill the details on new drama in her family. At times, Alma even acts as a confidant for Jill’s own venting when Jill finds herself overwhelmed by her own personal chaos. There’s also the adorably buff White Knight cyborg Sei, and her “Cat Boomer” childhood friend Selma. The two are a nearly inseparable pair, whose love for one another is palpable just in how they banter with one another. The women of VA-11 Hall-A are all on the lookout for one another, whether it’s helping to hide patrons from creepy stalkers or just lending a kind ear when needed.

There’s also time to spend with Jill alone, outside of work hours, when you can get a larger grasp of the city you inhabit. This is when you can skim unhelpful food blogs from The Augmented Eye, a tabloid newspaper, on Jill’s handy-dandy tablet. You can also scroll through the city’s own Reddit-esque feed, to read musings about the existence of a so-called hacker running amuck in the city. There’s also *Kira* Miki’s personal blog, a virtual idol that seems to be Glitch City’s answer to today’s Vocaloid superstar Hatsune Miku. Except that, well, *Kira* exists in some capacity, since she’s an actual robot. (And a rather delightful customer at that, as a random encounter with her proves.) Glitch City’s story is told through the voices of Valhalla’s customers, and the flavorful sidetexts that Jill skims freely. It has the effect of making Glitch City feel lived in, despite the game never letting you take a walk around it.

VA-11 Hall-A flips the atypical ways of cyberpunk

But once that jukebox kicks in and I’m behind that counter, all the overwhelming cyberpunk dazzle fades away. I’m just an outsider, looking in through Jill’s non-judgmental (well, sometimes judgmental) eyes. I can only imagine what the mysterious city outside of Valhalla actually looks like. I can probably draw up a pretty decent picture. But I don’t have to. Glitch City lives through Valhalla’s patrons’ personal stories within it, and with Jill’s own personal relationship to what living in a such a rundown city entails. It’s the type of cyberpunk that is less concerned with the heights of its polluted buildings and the chaos of its flying traffic, instead turning up the volume on the people who are hustling for a living—a medium we can better relate to.

During my time at Valhalla with Jill, I grew used to seeing the familiar faces, day in, day out. Even with the most irregular of regulars. I knew that Dorothy always wanted something overtly saccharine like a Sugar Rush, matching her personality. I knew that the biker Mario, a Kaneda-reminiscent customer who popped in only a couple times, would change his mind from a feminine drink to a bitter, more masculine one, because of being shy about his sexuality. I knew that the asshole Editor-in-Chief of Glitch City’s The Augmented Eye would always demand a beer, and then insult Valhalla and spew sexist bullshit. As a bartender, I’d come to expect such things. Jill’s used to it. It’s her job to get used to it, afterall. But where there’s an incredibly unsavory customer, there were always about two or three more to brighten up her day, or at the very least, even out the negativity.

This isn’t Glitch City’s story. It’s the story of its people, its liliths, its sentient preserved-brains, its talking dogs. It’s the story of Jill and her customers, all being lost, and eventually finding their way. VA-11 Hall-A flips the atypical ways of cyberpunk, and shifts the genre into a new direction: by making it a character study, more relatable than ever before. It’s where other “modern cyberpunk” efforts, such as Watch_Dogs (2014), fail in their lackluster attempts to humanize their characters beyond its hyper-technological society. You don’t get to know people by scanning them with your phone, you do it by serving them a drink during hard times. At its core, VA-11 Hall-A is the rare cyberpunk story that has heart, and even goes so far as to give its female characters agency in their own lives. It’s a story where we, the player, take the backseat, and soak it all in. Just like a good book.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post VA-11 Hall-A is how you do modern cyberpunk appeared first on Kill Screen.

June 20, 2016

Watch a rare, perfect game of Dota 2

Perfection is a rare and beautiful thing in Dota 2 (2013) no less than any other competition. In terms of prestige, a flawless game in Dota 2—by which I mean a game in which the winning team destroys the opposing team’s ancient without suffering a single death—ranks up there with a hole-in-one on a par five or a perfect nine inning outing in baseball. It’s really, really rare. Entire careers will transpire without ever being involved in one. To wit, elder Dota 2 statsman Ben “Noxville” Steenhuisen estimates that perhaps a dozen have occurred in thousands upon thousands of professional matches since 2011.

OG sparkles amid this systematic chaos

When a perfect game does happen, it’s usually because a lower-tier team has the misfortune of getting matched against an elite squad. Among meetings of premier teams, perfect games occur with the periodicity of Earth-threatening asteroids. But hallelujah did we get one a couple weekends ago at the Manila Major! The multinational superteam OG—an unknown acronym, but popular speculation includes everything from Oedipal Gamers to Ocular Ganja—utterly disassembled the South Korean outfit, MVP Phoenix. A serious contender even under the worst of circumstances, MVP nevertheless suffered 25 straight deaths with no rebuttal before throwing in the towel at 25 minutes.

It’s a textbook OG beatdown, built of batshit insane dives, action movie escapes, and a characteristically virtuosic performance from midlaner Amer “Miracle” Al-Barqawi (can anyone seriously claim that this guy is not the best player in the world, possibly ever?). OG sparkles amid this systematic chaos, orchestrating their victory with a degree of precision and speed that suggests telepathy was somehow involved. Take this one vignette for example: the coordination needed to save Franck “Cr1t” Nielsen’s Elder Titan from certain death during the way-behind-enemy-lines skirmish around 11:30 is… well, it’s on some Saving Private Ryan-type level.

Anyway, just watch it for yourself:

OG went on to win the Manila Major, bagging $1.1 million and establishing themselves as the favorites going into The International 6 in August.

The post Watch a rare, perfect game of Dota 2 appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers