Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 96

July 6, 2016

What Survivor can teach us about emergent game design

If you were inclined to pare down the reality TV show Survivor (2000-present) to three key terms, they would likely be “tribal council,” “immunity,” and “alliances.” The first two are part of the core Survivor game template. Every three days, there will be a challenge—early on between two tribes and later, after merging, as individuals. The winner is safe at tribal council, where a person must be voted out of the game. “Alliance,” meanwhile, did not come from Survivor’s creators, but the revolutionary machinations of its first winner, Richard Hatch. “Richard Hatch was so far ahead of us in the first season,” said host Jeff Probst to Ben Blacker on the Writers Panel podcast. “He started the first alliance, and I remember him doing it in front of me… I think it was Sue Hawk he looked to, ‘You know we should vote out so and so.’ We had never considered people would work together. It seems so basic now.”

Executive producer Mark Burnett imagined the show as a survivalist adventure, where voting was meant to knock out weak links and negative personalities for the good of camp life. It was a fantasy about Americans being shipwrecked and cultivating an effective civilization in harsh conditions. But with a million dollars on the line, Survivor quickly turned into Ayn Rand’s wet dream; the story of a bracingly naked man using people like toilet paper on a quest for (monetary) glory. It seems so quaint now, but at the time, creating an alliance was looked down upon as bad sportsmanship. Because of Richard Hatch—a snake according to Sue Hawk, his first alliance member—Survivor went from Gilligan’s Island (1964-1967) to Lord of the Flies (1954). Building a camp, starting a fire, gathering food: now all a backdrop to the scheming and conniving of Hatch’s children.

I can think of no better modern definition of emergent gameplay than Survivor. A nebulous and ineffable design concept, emergent gameplay refers to a style of play not necessarily intended by the creator. The ubiquity of board games like chess, and sports like soccer, can succinctly be explained by emergent gameplay; these are systems rich with possible strategies for success. They offer a problem to players who can intuit multiple solutions. The book Moneyball (2003) could have very well gone with the far more clunky title Emergent Gameplay in Baseball, as it finds General Manager of the Oakland Athletics, Billy Beane, devise a new way to scout and analyze players in order to compete on a pitiful budget.

Esports like League of Legends (2009) similarly stick around due to player innovation. An essential lesson for any League of Legends player is learning the allocation of roles and their place on the map. Tanks go top, mages go mid, rangers go bot with a support, and a mixed stat champ roams around in the jungle. This was not always the case, though. The meta was pioneered by European players like those of Team Fnatic, who won the Season 1 World Championship employing the strategy. The question of whether the recently released shooter Overwatch can translate into an esport comes down to whether the game has enough room for emergent plays or not. Survivor can thank its players for its staggering evolution as a competitive game over 16 successful years of broadcast.

I can think of no better modern definition of emergent gameplay than Survivor.

“I don’t think there’s any sort of guidance from production even now, to say, alright, make alliances,” said former Survivor player Rob Cesternino. “People coming into the game know right off the bat what they need to do, and there doesn’t need to be any sort of help from production to sort of tell them to either get their camp life into order or to get their strategic games in order.” Cesternino, who played two seasons of the game—Amazon and All Stars—and now hosts his own podcast about Survivor and other reality television shows, patented his own self-interested tactic informally known as alliance-switching. An inflexible caste system inherently exists within any alliance. As Kanye said, there are leaders and followers, and many players are under the false illusion that they can work their way to a level of prominence in their little society. Everybody’s always the hero of their own narrative in their head,” Cesternino said.

Nobody figures themselves a bottom feeder simply dragged along for votes. Seasoned leaders like “Boston” Rob Mariano make sure of that, buffing up the self-worth of these lowly tadpoles before systematically cannibalizing them near the end of the game. Basically, Boston Rob became Survivor’s own incarnation of Vito Corleone. Cesternino took this known element of the game and innovated a new way to play. “I was one of the first people that was able to identify, well, if I can show people that they’re in the bottom of this group, then it’s not in their best interests to keep voting with that group, come vote with me,” Cesternino said. “I was able to flip the groups I was in a couple times, and then I think that’s sort of something that really helped to change the way people were playing, especially in the second part of the game where people were more self-interested as opposed to what is for the good of my group. So I think that’s something that really has stayed within Survivor, and I think that the point in which people are playing that way has gotten earlier and earlier.”

The strategy goes hand-in-hand with a known quantifier for supposedly winning the game. Soon after the initial two tribes merge, the people voted out return as a jury who decide the winner of the game, usually between the final two or three players. To convince a jury they deserve the title of sole survivor, one must make a demonstrably big move. Thus, players self-aware enough to realize they sit at the bottom of an alliance will look to join up with others to backstab the big timers in the game. Simple enough, except another little evolution occurred last year during the phenomenal Second Chance season. Fans voted in a cast of past players who came up short during their seasons. These vets unknowingly crafted a new form of play: voting blocs. Instead of two alliances, a majority and minority, there was a proliferation of many small alliances who temporarily worked together every three days to vote out common enemies. The majority did not slowly eliminate the minority, nor did the majority cannibalize itself. Survivor become less of a Cold War, more of a UN conference.

When emergent gameplay works, it feels almost as if the player is conversing with the unseen creator, and in the case of Survivor, the producers play off the players to help introduce interesting new twists; some more successful than others. “I think people like the little bit of a wrinkle as opposed to a wholesale redesign of the game structure,” Cesternino said. Case in point: the much maligned Redemption Island. Instead of leaving the game after being voted out, players would instead head to Redemption Island, where they competed with other ousted players for a chance to re-enter towards the end. “They have a difficult chore on their hands,” Cesternino said. “They want to change it up just enough so that it is fresh to the viewer but not change it too much so that it’s foreign to the viewer… I think that people just felt like it was too foreign from Survivor where somebody gets voted off but they’re not actually gone, they’re going to this Redemption Island.”

One of the enduring additions to the game by the producers is the hidden immunity idol. Whereas previously the only way to stay safe at tribal council was to come up victorious at challenges—tough to do if one lacks physical strength, endurance, or puzzle-solving skills—players could now find clues to immunity idols tucked away in the wilderness. Even better: they could play the idols after the votes had been cast. Their surprise use at tribal councils have led to some of the most memorable moments in Survivor history. Russell Hantz—a diabolical, cocksure mastermind—figured he didn’t need a clue. Naturally, the idols would be hidden around landmarks. How else would people find them? So as the rest of his tribe laid in wait at camp hoping to win a clue, Russell simply sauntered off into the jungle and found an unprecedented number of idols without clues. As an underdog, he used them to blindside members of the majority tribe. He also told them to kiss his ass as they left, which cost him the jury votes needed to win.

When emergent gameplay works it feels almost as if the player is conversing with the unseen creator

In subsequent seasons, players follow Russell’s lead in simply scrounging for the idols. But as a response, the producers recently “patched” the hidden immunity idols, something they tend to do when players find a dominant strategy. The show used to always do a “Survivor Auction,” where players were given a small budget to bid on food items. After a few iterations, Probst began offering a clue or some other advantage at the end of the auctions. Players caught on and stopped bidding for food, making for a rather boring sequence. Thus, the Survivor Auctions ended. “It may be broken at this point and time,” Cesternino said of the Survivor Auction, sounding a lot like a pro League of Legends player discussing an overpowered champion or item in need of a good nerf. On Second Chance, idols were instead hidden at challenges, and players who found clues at camp would be told where to look; an amazing wrinkle that forced people into do-or-die moments in the heat of battle. However, the most recent season included a controversial final reward challenge: the winner could vote out a jury member. “It’s a bit of a cat and mouse between production and the people playing the game, because once the people catch on to that, then production needs to figure things out,” Cesternino said.

All of this comes back to how the players use these little additions, and the truest testament to the depth of Survivor is in the breadth of playstyles employed by the winners, who consequently come in all shapes and sizes, races and genders, sexualities and creeds. Some players win challenge after challenge, remaining perpetually safe at tribal council. Others backstab their way to the top. Some lead a strong coalition to the end. Others coast along under the radar before making a big play at the very end. Then there are the few who simply socialize and make real connections with future jury members. “There is no sort of, this is exactly what you do to win the game,” Cesternino said. “It really is so dependent on the circumstances and the other players that are in the game… Every single person has different things that motivate them in terms of the game, and I think that’s one of the reasons also that it makes it such a fun, human experiment to watch.”

Survivor changed the landscape of television and remains popular nearly two decades after its inception on the strength of its players, who continue to innovate season after season. Many games come and go, plenty with merit, but often the experiences that linger trust players to solve a problem by their own volition. In the online multiplayer browser game, Town of Salem (2014), I thought I hated being a Jester; a rather insignificant member of a society trying to suss out a murderous mafia ring and psychopathic serial killer. While those devious few kill at night, the good townsfolk must determine their identities during the day, sending suspicious players to a trial for execution. Jesters do no such thing as their motive is to hang by the neck at the gallows. If you succeed, you may haunt and kill someone who casted a guilty vote—like the vindictive high plains drifter riding in on a pale horse. It seemed shallow. You either accuse yourself of being a murderer or you act nuttier than squirrel shit. In either case, the townsfolk will assume your identity as a Jester and disregard your every word from then on. They may be fearful of your true intentions, but they’re certainly not stupid. No one believes a loudmouth.

Every single person has different things that motivate them in terms of the game

But for some reason, they fear whispers. During the day, a player may speak privately with another, but everyone can see when the whispering occurs. Suffice it to say, no one in their right mind would discuss murder among the populace. If you’re part of the mafia, you may speak to your people in secret at night. No need to bring it up while the sun’s in the sky. Nevertheless, paranoia permeates the air whenever a hushed conversation ensues. No one believes a loudmouth, but someone who wants to keep their business to themselves? To most, that’s an honest, albeit stupid, person. So when I “accidentally” failed to whisper by using the incorrect slash code (“w/” instead of the proper “/w”), people took notice. They believed me. It confirmed their suspicions. If everyone who whispers is an absent-minded suspect, then the moron who publicly states in chat, “w/ Thomas Danforth I think you should kill Samuel tonight,” is undoubtedly a member of the mafia. Imagine the town’s horror when I revealed myself as the Jester while choking to death. The chat blew up with shocked awe, and I sat laughing to myself for managing such treachery. I felt like a mastermind. An innovator. A pioneer.

I felt like Richard Hatch.

The post What Survivor can teach us about emergent game design appeared first on Kill Screen.

Bum Rush, a racing game tribute to the pursuit of sex in college

Have you ever been sexiled from a shared apartment? I haven’t, but I recall an instance of a friend in college being sexiled while he was away in the bathroom—his roommate had come in during his absence, along with his girlfriend, and left a sock on the door. My friend sat for the next 30 minutes, towel clad, in the lobby of the dorm waiting for them to finish up.

Bum Rush, the newest game by Nina Freeman, Emmett Butler, Diego Garcia, and Maxo, is about the experience of sexiling your roommates. The game does this through a combination of combat and car racing, and is designed as a party game. It’s all about kicking your roommates out of the apartment so you can participate in the horizontal tango.

take as many dates home as possible

“The origin of Bum Rush was a conversation between my collaborator Emmett Butler and I. We were talking about our experiences being sexiled during college—all the times when our roommates locked us out while they were having sex, or the times where we actually just walked in on them and then promptly left. I thought that these stories were really funny,” Freeman says. Emmett Butler, a frequent collaborator on games like Cibele (2015) and How Do You Do It (2014), contributed programming to the game which was originally created for arcade event No Quarter.

With its arcade roots, Bum Rush was designed for about four players—eight if you can get them all together for a night of controller-based fun. The game combines a dating simulator and a racing game, allowing you to race home ahead of your roommates so you can get there first. You can also delay your fellow booty-call-adventures and steal their dates, allowing you to take as many dates home as possible. Just make sure you’re in the door first, and you’re in for a successful night.

The 8-player car combat game is available on itch.io. You can find out more about the Bum Rush through the official website.

The post Bum Rush, a racing game tribute to the pursuit of sex in college appeared first on Kill Screen.

Today in GIFs: Get a look at Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor’s strange world

It’s been too long since we last checked in on Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor, the game about exploring a grand sci-fi universe through the viewpoint of a lowly municipal worker rather than a more standard space marine hero figure. Since my original post covering the game, the team has been hard at work bringing the backwater trash-planet it takes place on to life, and recently, that work has paid off as a series of new GIFs and screenshots posted to the game’s official Tumblr. Since they give me an excuse to write about this adorable blue collar spin on space adventure again, let’s take a look at them, shall we?

The first thing that comes to mind with these new gifs is the sense of depth. Not narrative depth, although that certainly seems to be present as well, but visual depth. While the previous screenshots from the game did include some light CGI elements, you would be forgiven for looking at its pixelated spritework and assuming the game was in 2D. Here, however, the game’s true low-poly nature shines through. Look, dear readers, at our heroine picking up trash, and marvel at all three of its glorious, albeit stinky, dimensions.

We also get a glimpse of the type of ships coming in and out of the game’s titular spaceport. In one particular GIF, there appears to be two of them, as well as a shadow of what could be a third. Notably, they all look like sea creatures, with the two visible ships resembling manta rays and the shadow resembling a shark. Another GIF shows the spaceport on a busy day, along with a surprisingly speedy ship resembling a whale.

Shortly after, we see a few GIFs of our heroine at market, ogling goods she could never afford. Like the description says, “You may never make enough money to buy these items, but window shopping can still be a lot of fun.” It’s a nice subversion of a typical videogame shop system, and helps drive home our character’s place at the bottom of her interplanetary society. She may live among these shops, she may even pass some of them during her normal daily commute, but they are distinctly not for her.

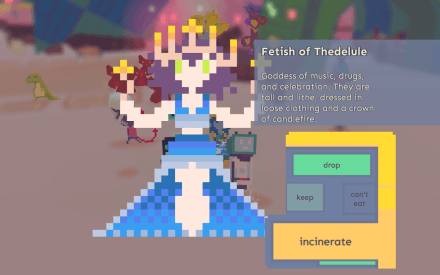

Another set of images highlights a weekly festival celebrated by the local populace. Held on “Theday,” it involves lighting prayer candles, listening to live music, and of course, throwing lots of garbage on the ground. Guess who’s gonna have to clean it up?

However, not all discarded items are garbage. Some items are special, if only just, as the site’s description states, “because of how they make you feel.” When all you can do is window shop, I suppose you take what you can get, even if it’s just a crumpled up star chart of places you’d much rather be.

Finally, the most recently posted set of GIFs show off the “Sewerdungeon,” an area that is said to hold “many terrible secrets.” Additionally, they also give a glimpse of the mysterious floating skull that, as the result of a curse, follows you around throughout the game as a whole. Both make you “feel very strange,” and my guess? You weren’t even supposed to come in today.

All of this paints a promising picture of a game about working a job you hate, because, even though you’d rather be anywhere else, you just need the cash. Worse for the protagonist is that, because she lives in a Spaceport, escape is always taunting her. She’s not kept at the bottom of her society by distance or lack of ability, but by economic inequality, which is a much harder hole to crawl out from. So hard, in fact, that enduring taunts from a floating skull and digging through garbage in the sewers starts to look like a preferable alternative- no matter how strange it makes her feel.

For more on Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor, visit their Tumblr, and follow them on Twitter.

The post Today in GIFs: Get a look at Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor’s strange world appeared first on Kill Screen.

You should play the new poetic game from the Kentucky Route Zero designers

Have you downloaded the iOS/Android Triennale Game Collection yet? We wrote about it a few weeks ago; the gist is that Milan’s La Triennale di Milano, an exhibition held by the Triennale Design Museum, is back after 20 years, and they seem to like videogames. Santa Ragione’s Pietro Righi Riva has commissioned new games from five designers, including Kentucky Route Zero designers and Kill Screen sweethearts Cardboard Computer.

Their entry, Neighbor, is a meditative little vignette along the lines of Mountain (2014) or Animal Crossing. It’s done in Cardboard Computer’s house style: tasteful low-poly art, poetic, spare writing, and a synthesizer score that straddles melodic and ambient vibes. You direct a little person around a sun-bleached, sand-swept crater where they’ve set up a workbench, drawing desk, and cauldron (as you do).

It feels like anything could happen

You can make sketches of things you find, or throw coins in a reflecting pool. You can meditate, or sweep the sand from your modernist living structure. There’s always more sand. You can make clay sculptures, or write poetry. You can bury crystals and watch as they bloom into gleaming plants. You can offer objects before a worn monolith. You can think about your life, and where it’s headed, and what you might do when it gets there.

Occasionally, an honest-to-God cowboy stops by to check on you. According to the game’s pause screen, his name is Sam. He lent you a shovel. Try writing Sam a nature poem and see what he says. He might also like that magazine about trucks that you found. You know Sam’s arrived when you hear him whistling, but there’s no rush. He’s the patient type.

There’s a lingering cosmic vibe below Neighbor‘s surface. The phrase sic itur ad astra, or “thus one journeys to the stars,” from the Latin epic poem Aeneid, pops up a few times. And using Sam’s shovel you can dig up meteorite shards. Nothing is made explicit, though, or if it is I’ve yet to find it. There’s a magnetic pull to this game. It feels like anything could happen in its small, quiet space. Whether or not it does is immaterial in the face of its immaculate, engrossing mood. It’s not really fair how good Cardboard Computer are at this, but I suspect no one is complaining.

You can download the Triennale Game Collection for free on the App Store and Google Play.

The post You should play the new poetic game from the Kentucky Route Zero designers appeared first on Kill Screen.

The making of No Man’s Sky soundtrack

Post-rock has long been intertwined with film and television. That’s why there’s a big chance you’ve heard it before, possibly without even knowing it. Explosions In The Sky (one of the genre’s most well-known acts) blew up into mainstream consciousness after scoring the American football drama Friday Night Lights (2006-2011). Their fellow Austin residents This Will Destroy You have been heard in popular movies as well, including Moneyball (2011), World War Z (2013), and at least one ad campaign without their permission. Long-running Scottish act Mogwai (named after the furry creatures from Gremlins) most recently scored the 2015 BBC 4 documentary Storyville Atomic: Living In Dread And Promise.

So what is post-rock? It’s a genre tag that describes primarily instrumental music played within the context of a typical rock band configuration. This generally means guitars, bass, and drums, in addition to occasional electronic elements and orchestral arrangements. More defining, though, is that most post-rock bands eschew typical verse-chorus song structures, instead opting for nonlinear songwriting that often traverses subtle quiet to thunderous volume in the space of several minutes.

This structure has caused it to often be associated with classical music. In fact, genre staples Mono are renowned for their work with full orchestras. This connection to classical and orchestral music, which have long been used in film and television soundtracks, means it makes sense that post-rock is often used to provide a compelling alternative.

Videogames are no stranger to the world of classical music, either. Modern blockbusters such as Destiny (2014) effectively capture the epic scale of their worlds with classically-influenced arrangements that complement the onscreen action—an aural tradition that Bungie has carried on since releasing the original Halo (2001). The Evil Within (2014) borrowed snippets of Claude DeBussy’s “Claire de Lune” to indicate impending save points, evoking a sense of safety in an otherwise brutal environment. There’s even a growing trend of orchestras performing videogame music in an attempt to draw in new listeners. Given all this, it’s worth questioning why so few post-rock bands been asked to write full videogame soundtracks.

filling infinite space with sound

One reason for this could be due to the genre’s reliance on carefully timed tension and release—the moment of peak volume is often the listener’s payoff for their patience. Since movie and television scenes don’t change on repeated viewings, crafting soundscapes that reach their apex at just the right moments is a relatively straight-forward process. Games, on the other hand, aren’t always played in exactly the same manner twice. This presents two challenges: writing a score that accurately anticipates a player’s actions, and one that invokes an appropriate emotional response that suits the onscreen drama.

This is also partially why Guildford, UK-based independent studio Hello Games (previously known for its Joe Danger series of games) turned heads when announcing Sheffield-based experimental post-rock outfit 65daysofstatic would be crafting the soundtrack for the upcoming No Man’s Sky. The highly anticipated space game promises near-endless exploration across an effectively limitless procedurally-generated universe that will theoretically take billions of years to fully traverse. That means no set pieces, no cutscenes, and no predictable beginning, middle, or end. Building a game with such a sense of scale is unprecedented in itself. Writing a standalone soundtrack that could do it justice, filling infinite space with sound, would seem a downright monumental feat.

However, if an epic game requires an epic soundscape, then 65daysofstatic may just be the perfect fit for the job. Just as no two planets in No Man’s Sky are the same, nor are any two records in the band’s catalog, ranging from the industrial-tinged soundscapes on 2004’s The Fall Of Math, to the noisier guitar-oriented leanings of 2013’s Wild Light. They are no strangers to writing soundtracks either, having written and released an alternate score to the 1972 science fiction film Silent Running.

While 65daysofstatic’s sound falls somewhere along the post-rock spectrum, it doesn’t stick within any of the stylistic boundaries the label demands. The band is known for seamlessly blending organic and electronic instruments in a way few other acts can manage, as demonstrated by the dramatic synths and hyperkinetic rhythm section that underpin layered guitars on “Debutante” (a track from the 2010 studio album We Were Exploding Anyway chosen for the game’s official trailer). Endlessly inventive and never predictable, here’s what guitarist and co-founder Paul Wolinski had to say about what could be their most ambitious project yet: scoring a game that never truly ends.

Kill Screen: When Hello Games approached you about working with them on No Man’s Sky, what specifically hooked your interest in writing the soundtrack for the game?

They didn’t initially approach us about writing the soundtrack. They just wanted to use one of our older songs for their launch trailer. But when we saw what it was they were making, it was immediately clear to us that we wanted to get involved further. We are not active gamers, but that’s not to say we have no interest in the form or never play games, and had been paying close enough attention to that world to appreciate that there were interesting possibilities for music in that area.

KS: Was there much discussion between Hello Games and yourselves about the specific direction the music needed to take?

We’ve been given pretty much free reign, which has been flattering and intimidating in equal measure. When we first started discussing it with Hello Games, they told us that they had been using our back catalogue as inspiration and mood music during the early development phase, and that all we needed to do was write “65daysofstatic music” and it would be fine. This was easier said than done, because we never really know exactly what we are doing when we write, other than trying to sound different each time.

So perhaps the most difficult thing was to work out how to consciously look at our back catalogue, and figure out how to write something that was deliberately ‘65’ without feeling like we were wallowing in nostalgia, or relying too heavily on old tricks. From the beginning, we wanted to make sure that whatever we wrote, it worked as a standalone album we could be proud of as well as be the soundtrack to No Man’s Sky. Hopefully we’ve pulled that off.

KS: How much reference material did Hello Games provide in terms of design documents, concept art, or pre-release builds and demos you could play through?

Very little, but this was fine. One of the first exchanges we had with them about this project, they told us a little story about the launch trailer they were making. “We start underwater. It’s dark but you can make out shoals of fish swimming before you. They look strange. Alien…” They weren’t pitching us the technology of the game, the scale or ambition of the game. Not even the look of the game, as beautiful as it is.

meaning in music is contextual

What was important for them was creating that immediate, immersive experience for the player. This way of thinking was much more useful to us than spending hours playing unfinished versions of the game, or soundtracking captured gameplay footage, or whatever. We got to use our imaginations more.

KS: How did you approach writing music for scenarios that can’t necessarily be anticipated?

A lot of soundtrack work is deliberately minimal. It’s almost designed not to be consciously heard at all, to not intrude on the action. And furthermore, so much meaning in music is contextual. So, our aim was to pull out soundscape ingredients from the more fully-formed, linear songs that we wrote, and then curate and combine them to try and project a certain amount of emotion, for want of a better word, into a music bed. But at the same time, didn’t want to weigh them down with something so obvious that they’d be anchored down with an undeniable, unavoidable meaning.

This way, the context the music appears in hopefully allows the meaning to be created as a kind of collaboration between us, the game algorithms that chose these particular audio stems, and the player who is bringing their agency and own emotions to the moment that is being soundtracked. It’s tricky though, isn’t it? Because music is entirely subjective, and leaning too heavily on genre or cliché to get the desired effect can so easily have the opposite one. Sometimes sad music can make you really happy, and happy music can make you want to rip off your ears.

This explanation is about 95 percent hindsight though. At the time, it felt more like we were making-it-up-as-we-went-along.

KS: Are there any particular themes or intended emotional responses you kept in mind while writing in order to sync with what a player might encounter?

I think the main thing for us was to add a kind of grit to the experience. To accentuate the vulnerability and isolation of the player, and the hostility and brutality of space. We were less interested in soundtracking the colossal scale of a vast, infinite universe from a grand, outside perspective; we instead tried to soundtrack the visceral, immediate, but personal experience of being lost and alone somewhere inside a vast, infinite universe. If that makes sense.

KS: How much music did you have to write for this game, and is everything used in-game included on the retail release of the soundtrack?

We wrote a lot of music. It’s hard to say how much. Not everything that is in-game is included on the retail release—that would be impossible due to the nature of how the in-game soundtrack will work. But we tried our best to tailor the music to the various forms it would be heard, rather than attempt a one-size-fits-all approach.

So there’s an album of songs that are arranged in a more obvious, linear fashion. It’s about 45 or 50 minutes long. It hopefully works as a listening experience regardless of whether you have even heard of No Man’s Sky or not. Then there’s another album of more soundscape-like material. This isn’t quite like how the music will appear in the game, it’s more of a representation of how we envisaged what the soundscapes might be like, before we actually started working with Paul Weir, the audio director, to feed elements into the game. And then finally there’s the game, where the music is always happening ‘live’ and reacting to the gameplay. This music is built from the same ingredients as both the records, but probably won’t ever sound exactly like it.

KS: Can you describe the studio setup and gear used for recording?

At 65HQ (where we wrote): drum kit, more drums, a couple of good guitars, quite a lot of not-very-good-guitars, bass guitars, half a dozen amplifiers of varying quality and tone, some quite expensive analog synthesisers, some cheaper analogue synthesisers, some home-made analog synthesisers and fx modules, more guitar pedals than the number of planets in No Man’s Sky, laptops, various pieces of commercial audio software, much more interesting open source audio software, game engine software, sound design software, weird hacked-together, bug-heavy combinations of the above software we built ourselves to replicate the music logic brain of No Man’s Sky. (Our procedural music brain was a bit noisier, angrier and more inclined to techno than theirs ended up being).

the music is always happening ‘live’ and reacting to the gameplay

At Chapel Studios (where we recorded): all the above, plus a grand piano, even more amplifiers, isolation, no phone signal, wine, fancy microphones, tape machines, a pervasive existential dread, a weird organ, old school Neve mixing desk and a bunch of vintage outboard gear to add various shades of noise to everything we captured.

KS: What was the one piece of studio gear you absolutely could not have lived without in order to bring this project to life?

Coffee maker.

KS: Were there any particular types of tones or textures you aimed to capture in the studio?

I think the trajectory 65 had been on before we started work on the No Man’s Sky project was to kind of give up and form and structure and just make big slabs of noise. But that wasn’t appropriate here. So I think our intention became figuring out how noisy we could make things before it stopped feeling right as a soundtrack to No Man’s Sky. As it turned out, that still meant pretty noisy.

KS: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Just that Hello Games are some of the friendliest people we have ever had the chance to work with, and 65 find it kind of amazing that such a tight little indie team has found a way to navigate the capitalist realism of what it means to release a game on this scale, through Sony, and yet retain complete creative control over their vision. Nice one, Hello Games!

No Man’s Sky will be released August 9, 2016 in North America and August 10, 2016 in the UK and Europe. Its soundtrack, No Man’s Sky: Music For An Infinite Universe, is available for pre-order on vinyl, CD, and digital formats here .

The post The making of No Man’s Sky soundtrack appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 5, 2016

Psychedelia isn’t dead, just ask videogames

Though it hit peak popularity in the 1960s, psychedelia has endured as a genre of art, film, and particularly music that occasionally goes through periods of resurgence. Some of the best current examples of psychedelic culture, however, come from a medium that barely existed in the 1960s: videogames.

You can find dozens of lists of the best “psychedelic” videogames, but many of these lists focus on the superficial aspects of psychedelia. They use “psychedelic” as a synonym for “weird,” ignoring the original meaning of the word. Influenced both by early 20th-century abstract art and by experiments with hallucinogenic drugs, the first psychedelic artists wanted above all to explore and expand minds (with “psychedelic” being derived from the Greek words for “mind” and “to reveal”). While tie-dye colors and druggy imagery are the most visible hallmarks of psychedelia, the goals of most psychedelic artists extended beyond simply recreating the experience of being on drugs. LSD and other hallucinogens played a key role in psychedelia, but rather than being the end goal, they were a tool to reach states of transcendence and interconnectedness that weren’t possible to reach with the unaltered mind. Some artists saw the mind exploration of psychedelia as a spiritual quest and took inspiration from religion—particularly the religions of India, where concepts like prajñā (the wisdom to see the world as it really is) were repurposed to fit with a psychedelic lifestyle.

They were a tool to reach states of transcendence and interconnectedness

The most popular form of psychedelic art, psychedelic music, peaked in the mid-1960s and began to taper off shortly after LSD was made illegal in 1968. But while psychedelic music’s reign in the mainstream was short, its influence remains. Original psychedelic bands like the Grateful Dead and Pink Floyd have maintained cult followings into the present. More recent musicians like The Flaming Lips, Primal Scream, Tame Impala, Animal Collective, and Ariel Pink draw influence from the first psychedelic bands while also expanding the genre with synthesized instruments and digital recording techniques that didn’t exist in the 1960s. All of these bands have defined not only the sound of psychedelia but also the look of it, by including psychedelic imagery in their album covers, live shows, and music videos. LSD users often report feelings of synesthesia—when the body’s senses run together so you can, for example, “see music” or “smell color”—and psychedelic musicians frequently aim to recreate this experience with a sensory overload of sound and visuals.

New technology like video streaming and Pro Tools has helped modern psychedelic bands make even more immersive synesthetic experiences. Some artists, however, have gone a step further and incorporated a new element into their psychedelic journeys—interactivity. Browse the psychedelic tag on an online videogame store like Steam or itch.io, and you’ll find dozens of neon-colored banners for games that promise all sorts of mind-bending journeys and general trippiness. Some of these games simply use the visual style of psychedelia as window dressing, but others could be direct descendents of the original psychedelic art, sharing the same quasi-spiritual goal to free the mind by exploring it. Consider Sluggish Morss, a glitchy, sci-fi claymation series of games that could easily provide the imagery for a Flaming Lips music video. Or there’s Trip (2015), a peaceful game about exploring abstract art that, like the Grateful Dead, encompasses every possible meaning of the word “trip.” These games do more than just adopt the visual style of psychedelic music—they use its aesthetic as the basis for an introspective journey that simulates the experience of having an altered mind.

Many of these titles come from the more obscure fringes of game design. Some of the creators even avoid the word “game” in their descriptions—Sluggish Morss: Ad Infinitum (2014) bills itself as a “game/interactive music clip/album about space” while Trip’s tagline calls it an “experience.” But psychedelia has also begun to influence more traditional games—especially the types of independent titles that regularly reach the top of online bestseller lists.

psychedelia has also begun to influence more traditional games

Undertale (2015), whose central hook is that you can peacefully resolve conflicts with monsters instead of fighting them, clearly echoes the pacifistic hippie dreams of the 60s, but it also embodies other aspects of psychedelia. While Undertale might appear at first to be a game with a linear story, players who reach the end learn that the story is cyclic: choices you make during your first time playing will affect what happens when you replay the game. In many ways, the game’s structure embodies the ideas of birth, death, and rebirth that are central to Indian religions—and by extension to psychedelic music, which is full of songs like “Tomorrow Never Knows” by the Beatles and “The End” by The Doors that draw influence from Eastern spirituality. By dramatizing the effects of your choices from past “lives” and by trapping the player in a loop of death and rebirth, the game creates a state of samsara—the cycle of life from which spiritual-minded LSD users sought to escape. And whether or not it’s intentional, it’s fitting that the only way to escape samsara and achieve “nirvana” in Undertale is to totally let go—to stop playing the game.

Another feature of both psychedelic music and many recent independent games are surreal experiences with animals. Syd Barrett sang, “That cat’s something I can’t explain” on “Lucifer Sam,” and inexplicable animals have been a staple of psychedelic music from Jefferson Airplane (“White Rabbit”) to Tame Impala (“Elephant”). Weird animals have also long been featured in videogames—just look at Sonic the Hedgehog or Crash Bandicoot—but recent games have given this weirdness a psychedelic spin. After all, if there’s a logical modern-day successor to the Beatles’ “Octopus’s Garden,” surely it’s Octodad: Dadliest Catch (2014), a game about a loving father who performs household chores and is also secretly an octopus. Attempting to control the eponymous Octodad, who moves around his house like Hunter S. Thompson on ether, is a trip in itself.

Photo credit: Dr. Dennis Bogdan

Photo credit: Dr. Dennis BogdanPsychedelic animal games with intentionally dodgy controls have become something of a microgenre, with Catlateral Damage (2013)—a game about a kitten bent on destruction—and Goat Simulator (2014), being two other popular recent examples. These games follow a sort of dream logic where players are rewarded for, say, bouncing a bicycling goat off a trampoline. It makes no sense, but then again, neither did “Goo goo ga joob.” Psychedelic music’s obsession with animals came partly from Lewis Carroll, who loved hiding mathematical jokes in his work, and you could argue that the physics engines in these games, which are designed to produce maximum chaos, are equally elaborate mathematical jokes. These games force players to follow their own internal logic—which differs considerably from real-world logic—leading to a surreal experience that’s similar to the sensory confusion of synesthesia.

The focus on animals is a natural counterpart to one of the other major themes of psychedelia: the longing for a pastoral lifestyle. Psychedelic albums like the Kinks’ Village Green Preservation Society or Lindisfarne’s Fog on the Tyne depicted idyllic natural scenes as an antidote for urban, industrialized life, and a crop of recent independent games have done something similar. Firewatch, for example, is something of a paradox: a videogame that wants you to go outside and explore. It’s the story of a man who tries to escape his daily life by taking a job as a fire warden at a remote forest outpost. The game juxtaposes scenes of emotional turmoil with beautiful, hyperrealistic images of nature. In that respect, Firewatch is the videogame equivalent to a song like “Waterloo Sunset” or “Fog on the Tyne.” Flower (2009), a relaxing game about flower petals blowing in the wind, was arguably the first idyllic nature videogame to gain widespread acclaim, although the subgenre has roots in farming simulators like Harvest Moon (1997) and its modern counterpart, Stardew Valley. These games lack the mind-bending imagery of most psychedelia, but they share psychedelia’s yearning to withdraw from society and become more introspective.

Many of these games might seem weird for the sake of being weird, but psychedelic games often share a similar, purposeful goal. Timothy Leary, the famous LSD evangelist, wrote about “ego death”—a way to transcend the self. Few, if any, of the creators of these games are advocates for psychedelic drugs, but these games do aim for something similar to Timothy Leary’s ego death. They all force the player to consider things outside of their own experience. Psychedelia doesn’t have to be deep: sometimes it’s silly (“Dude, what if my arms were tentacles?”), and sometimes it’s nothing more than idle stoner philosophizing. But the best psychedelic games use their weirdness as a tool to promote empathy, encouraging players to think selflessly when it comes to other people, animals, and nature. The medium has changed, but the desire to explore the mind remains same.

The post Psychedelia isn’t dead, just ask videogames appeared first on Kill Screen.

The follow-up to Stasis is a mother’s worst nightmare

It seems only right that 2015’s grim industrial sci-fi adventure Stasis should get a spin-off chapter, called Cayne, and the same can be said for the fact that it is to explore the story of an expectant mother.

Stasis was an isometric love letter to the dimly-lit isolated vessels, claustrophobic corridors, and weathered lived-in interiors of movies such as Alien (1979), Pandorum (2009), and Sunshine (2007), those derelict places where otherworldly horrors and inhumane activities exist far from prying eyes. Cayne takes place in the same world as that game’s protagonist and his struggles on the mining ship Groomlake, but plans to tell its own story, to explore another facet of the dark unsettling world of Stasis. Creator Chris Bischoff describes how Cayne emerged from a number of ideas he wanted to explore, from the story of an engineer uncovering the secrets behind the infamous Project SEED, to a pregnant woman awakening alone in some isolated ship.

“You’re at the mercy of a surgeon and the nurses”

“That last story struck a chord with me,” Bischoff explained in a recent Kickstarter update. “I’ve been in hospital before, and the ‘missing time’ aspect of it all has terrified me. Off you are into theatre, count back from 10, and then wake up a few hours later in a different room… You’re at the mercy of a surgeon and the nurses. Deeply disturbing. Isn’t that what horror is made of?!”

Exploring that terrifying scenario, Cayne will follow a woman, Hadley, as she regains consciousness within the confines of a horrific medical facility. The insidious forces that have taken her want her baby, and now Hadley must escape with her life and her child. It’s a story that should very much be at home among its sci-fi brethren, which have long explored themes of motherhood and family. Think of Vincenzo Natali’s 2009 film Splice, which explored the relationship between two researchers and their “child,” a genetic hybrid of human and alien DNA—a relationship that devolves in disturbing and gruesome ways.

In Ridley Scott’s Alien and Prometheus (2012), we witness gross aberrations of pregnancy, as fleshy wiggling masses erupt from chests and stomachs. In Aliens (1986), we see two mothers concerned for their wards, one being Ripley and surrogate daughter Newt, the other being the towering skeletal Queen and her xenomorph brood. Fox’s TV series Fringe hinged on the cross-dimensional relationship of father and son, while The Terminator (1984), its sequel Judgement Day (1991), and the spin-off TV series revolved around the mother of humanity’s savior and all the struggles that go along with that destiny.

Not much is known about Cayne‘s story beside its basic outline, but under the hood, it promises to expand and evolve on the aspects where Stasis excelled. Dynamic lighting to better capture the deep shadows and subtle glow of emergency lights and fading fluorescents, animations shifting to 3D characters that allow for smoother and more complex movements, directional sound effects, and an updated engine that gives the team freedom to blend “technical expertise with the artistic vision” of Cayne. Bischoff describes Cayne as not merely an improved continuation of Stasis, but also “a perfect example of what we intend on producing” with the next game.

You can find more information about Cayne on the game’s website. It’s expected to release later this year as a free download for PC and Mac.

The post The follow-up to Stasis is a mother’s worst nightmare appeared first on Kill Screen.

In Kaasua, the wobbly racing track is your biggest enemy

Some racing games want hyperrealism, providing rumbled feedback to let the player know when to switch gears, recreating skidmarks on real race tracks, and giving a view from the inside where you can see all the gauges twitch. Robber Docks’s new game, Kaasua, is not one of those games, which is exactly what makes it so delightful.

In Kaasua there is only one button: the go button. You can assign any button on your keyboard to fill this role, allowing the player to easily accommodate the controls for just themselves, or up to seven others playing on the same keyboard. You don’t need to steer, the car does that for you. Instead of steering, you must carefully and constantly calculate your speed to deal with a track that is constantly wiggling and wobbling under and away from you.

every slight increase in speed is exponentially more dangerous

The wobbly track allows the game to strip down racing to its simplest motivation, “get around fast,” without being boring. The single button controls are similar to the racing mini game “Slot Car Derby” featured in both Mario Party (1998) and Mario Party 2 (1999). However, in Mario Party, if you went too fast you’d spin out, allowing others to get ahead of you. The game could be mastered by determining how fast you could go without losing control. With an ever-squirming track, Kaasua prevents this quick expertise.

Even if you understand the controls, the track may still quickly worm it’s way out from right under your car. The goal, of course, is still to go the fastest around the track. But the random twitches and wobbles of the track make your speed an even greater matter of risk and reward than is usual in racing games. With a constantly changing track, and no option to slam on the brakes, every slight increase in speed is exponentially more dangerous.

The unpredictable movements of the track also make Kaasua a unique take on competitive racing. The players aren’t just trying to beat each other, but also the track. When all the players can similarly be thwarted by one swift shift of the road, they have a common enemy in the game. Like the bright visuals and the upbeat music, this reinforces that the competition is meant to be more friendly than aggressive. While the first few plays may be mechanically surprising, Kaasua is easy to pick up, and delightful in it’s simplicity.

The post In Kaasua, the wobbly racing track is your biggest enemy appeared first on Kill Screen.

Black Gold lets you meditate on the mundanity of small-town America

I’ve lived my entire life in Texas. I graduated high school in a small town on the south edge of Fort Worth, Dallas’s dull little brother. There’s a suffocation, growing up in a place like that, a smallness; most people you know have had families who have been here for generations. They’ll reminisce about the farmlands turned into strip malls, spending an hour or two talking about the storied and sleepy history of some decrepit farm road crawling out into the boonies. No one really leaves a place like this. The edges curve into themselves, creating an invisible gravity as oppressive as the Texas heat.

The particular boundaries of that sort of life aren’t often captured by videogames. It’s too mundane, too provincial, too tied to a particular type of lifestyle. The Mystic Western Game Jam, put on by the Austin-based indie collective Juegos Rancheros, which counts Brandon Boyer and Rachel Weil among its leadership, might do a little to change that. If nothing else, one of its entries, Black Gold, certainly does.

The wistful loneliness of being at the edge of a small town

Lean back in the bed of a pickup truck, look at the stars, and sip on something cold. A Lonestar, in all likelihood. Study the way the sky never seems to end out here, the white on black of stars and the occasional motion of a low-flying military helicopter from some nearby base. Talk about nothing in particular.

Black Gold, created by Conor Mccann with audio engineering by Devin O’Brien and music by Chris Schlarb, is the sort of simulation that devotes itself to capturing a feeling. The wistful loneliness of being at the edge of a small town like mine, looking up, wondering where to go next. It’s a game that knows what it’s like to feel the pull of familiar places—the corner store across the street from the high school where you got sodas before Driver’s Ed, the dingy Southern Baptist church with no steeple where you snuck your first kiss—and it knows what it feels like to want to rage against them, to escape.

There are hints of plot, a dead father, a potential move, a rebirth. A machine pistons behind the two men who are Black Gold’s stars, pumping something precious out of the ground. Along the freeways in Texas, you can see towers of wireframe machines, natural gas lines and oil refineries scattered among the scarred plains. At night, they’re covered in flood lights, blinding like a vision of God.

There are even surprises, here, a notable amount of depth for a game that takes no more than five minutes each playthrough. See if you can find the drug trip. But above all it is a simple game about a conversation that says nothing much, spoken in half-intoxicated ellipses, full of wonder and sorrow and summer sweat.

I left my hometown as soon as I could. I had this profound fear: if I stayed, I would never leave, and I would be the smaller for it. I went South, to San Antonio, near the epicenter of the wet and hot of Texas Hill Country. I remember spending a lot of time drinking with friends, leaning out the balconies of college dorm rooms, talking the philosophical nonsense that’s best left for after the fourth beer.

Black Gold manages to capture a bit of that, too. I remember the abstract spirituality of it. Looking at the sky and wondering at how damned big it is. The sunsets down there fill every inch of it with color. We would watch as they faded into the leafless trees, our tired eyes following as the blackening sky reached down to the horizon line and devoured it whole.

You can download Black Gold over on itch.io.

The post Black Gold lets you meditate on the mundanity of small-town America appeared first on Kill Screen.

Mirror’s Edge: Catalyst, a radical city in a failed system

I’ve always been fascinated by the coherence and incoherence of cities. The system and interface of their streets. The network logic of their rooms. In my fifth year in London, buried in basements fashioned to appear as French cafés or Italian bistros, I obsessively traced the shapes of silver ducts and pipes, interwoven along the ceilings as if they were circuit boards. Among the fake leather seating and off-white walls, the large canvas prints of Parisian street scenes and the art-deco light fixtures they stood out as uniquely functional objects, unornamented, hidden in plain sight. I followed them down flights of stairs, into low corridors, slanted and uneven, where rows of doors were marked with pristine private signs, leading to unknown destinations at unknown angles along unknown vectors. I began to see the city differently, not as a territory of demarcations, but as a single branching corridor of various volumes, a set of rooms that might be traveled in a single path, one to the other, never stopping, like the current in the wire—the signal in the system.

There is no dirt, no decay, only pristine progress

The city of Mirror’s Edge: Catalyst is nothing like London. Instead of crumbling brick and rain-stained concrete there are only glistening volumes and flaring screens. There is no dirt, no decay, only pristine progress occasionally sullied by the scuff marks of black-soled running shoes. This virtual city lacks the complexity of the glacially growing oil slick that is London. As it stretches towards the horizon it reaches towards simplicity, devolving into white cubes as if reaching back into its own history of white-boxed levels and untextured 3D spaces. It is almost nonsensical, built from collections of interiors and exteriors that don’t seem to point towards any kind of civic function. It has no history—it could have been built in a day. It has no citizens, and no life, apart from the idling shapes of ever distant figures and the constant drone of unmanned vehicles. Yet I can’t help but feel the two cities are somehow connected, as if one was the dream of the other. Not a dream of minds but of machines.

///

The original Mirror’s Edge (2008) had a kind of purity to its narrative. A nameless city, simple characters, an obvious conspiracy, it allowed the art direction and movement systems of the game to step into the frame. Speak to a Mirror’s Edge fan and they’ll barely remember the ins-and-outs of the plot, the clean lines and smooth movements wiping them from their memory. Developer DICE’s response to their apparent failure is to flood Mirror’s Edge: Catalyst with unavoidable narrative, with “lore” and exposition. It has been suggested that Catalyst is a remake of Mirror’s Edge, or a reboot, but it is in reality a re-alignment of the first game with the recognizable features of a mainstream videogame, a reparation between the most original of its ideas and the most generic features of its medium.

Most of this is done inelegantly: The nameless city is relabeled as “Glass” (as in “city of Glass,” sadly not a Paul Auster reference). This city is populated with seemingly endless terminology; “Grid,” “Beat,” “Omnistat,” “Employ,” “Scrip,” which is further muddied by being fed into awkward camel-case terms like “offGrids,” “outCaste,” “gridLink.” And finally a thin sheen of cyberpunk plot is laid over the whole thing, built around a skeleton of subterranean rebels and an ignorant, hooked-up populace pulled from the body of The Matrix (1999) and clad in ideas so broad that they fail to register as anything other than well-worn tropes. With the inelegance of a cyberpunk-themed Tumblr, it all feels clumsy, especially when the big bad software program you are trying to stop is called “Reflection” in a city called “Glass” in a game called “Mirror’s Edge.”

Alongside the game’s contrived fictions, the structures of Mirror’s Edge: Catalyst have been aligned with the most standardized features of the its videogame peers. This is due, in part, to the transformation of the linear level-based structure of the original game, to the open-world layout of Catalyst. Though this new open, explorable city invigorates the game (for reasons I will come to later) the long trail of standardized game design that comes with it almost drowns the cities unique characteristics. Climbing puzzles to unlock fast travel, floating collectables in out-of-reach places, allies under attack by guards, safe houses, control towers, delivery missions. The bloat is evident on the game’s minimalistic map, which slowly fills with an impregnable swarm of icons that might make you forget this isn’t an Ubisoft game. It’s as depressing as it is predictable, and shows DICE failing to understand the strengths of its own creation. What’s worse is the reward for these activities is a levelling system that epitomizes the lack of imagination on display. Locking basic abilities behind an XP wall is inexplicable enough but once those are used up, the game turns to unlocking the usual slew of “more health” and “increased damage.” Deafened by this droning mediocrity, the average player might miss the ability to create and share their time trials, a simple but elegant idea, that in reality is strong enough to replace the dross that conceals it.

It is a study par excellence of light and space, interior and exterior

Yet, beneath the labored terminology and painfully uncool dialogue (“That’s why I can smell my own,” says one Morpheus knock-off early on), and beneath the boilerplate game design and its familiar drudgery, lies the City—not as a fiction or an “open world,” but as a series of volumes. In its broad-but-shallow chosen genre of “open world action adventure,” Catalyst is unremarkable, but in the field of virtual architecture it is radical. It is a study par excellence of light and space, interior and exterior. At its weakest, its collection of rooftops are a free-flowing set of pathways, disguised between air-conditioning units and billboards. But at its best the game presents a near abstract set of interiors and exteriors that run together in complex lines, like a Piet Mondrian expanded into three dimensions, plated in composite materials of minerals and metals.

Shimmering Heights, the game’s strongest area, feels less like a literal fictional city, and more like an exploration of how architecture might trap, manipulate, and configure light. It is filled with scattered cubes, demarcated into half -open lobbies and reveals, from each angle, a constantly changing dreamscape, a diagram of architectural possibility. That such things might be hidden within generic game design structures might be a surprise to some, but then the strength of games has never been their narratives, but the character and complexity of their spaces. There are more literal, atmospheric spaces here too, areas that evoke the fizzing night of Tokyo or Shanghai, but they are fragmentary, elusive, forming from one angle and collapsing from the next. This is a city of pure ideas, ideologies and atmospheres, and it glows with intelligence.

Equally, while the game’s cyberpunk fiction is weak and unoriginal, its vision of a cyberpunk city has a powerful integrity. The art direction’s focus on surface is something that feels like a cohesive development of the William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s fragmented descriptive styles. Using physically-based rendering to give a photoreal sheen to unreal architecture, the game’s surfaces choreograph a complex set of light flares, reflections, and shadows. Geometric anthracite faces are revealed to be delicately honeycombed in the dawn light, while the palette of whites and off-whites the game delicately arranges shift from minimalist solidity in the heat of the day to porous reflectivity in the neon night. The day and night cycle that drives these shifts is one of the few truly transformative examples in games, it’s evenings going way beyond the dull swampy darkness of its peers and emerging as a multi-faceted digital dream space. However, the true drive behind this vision is the way it rewards movement, as huge screens drench thin walkways in corrosive yellow, or the neon glow measures out a steady pace through slatted rotating blinds. It brings to mind the fractured tenacity of Gibson’s prose in Neuromancer (1984) and others: “Afterimage of a single hair-fine line of red light. Seared concrete beneath the thin soles of his shoes. Her white sneakers flashing, close to the curving wall now, and again the ghost line of the laser branded across his eye, bobbing in his vision as he ran.”

And beneath these dynamic surfaces we find Catalyst’s most powerful contribution to the idea of a cyberpunk city. It is no coincidence that the city’s towers resemble PC towers, high-end graphics cards and server racks: beneath their skin hums the workings of vast processors looped in endless cabling. This city is not just a place, it is a system, a huge single computer working to manifest the augmented reality of its citizens. Once inside these spaces, accessed by huge cooling fans, the player finds themselves crawling up server racks, jumping between network architecture, sliding down data conduits. Rather than evoke the neon-gridded unreality of cyberspace, Catalyst focuses on the pure material industry required to generate neural networks and complex computation. In short, it transplants the distant server farms that drive our lives into the very skyscrapers that gaze down on us everyday. This is a radical and compelling cyberpunk idea, one that turns the city into a vast machine dreamer, and its inhabitants trapped in augmented reality into the subjects of the city’s dream. Sadly, the game’s narrative and lore wanders past this powerful metaphor, unable to recognize it in its rush to ascribe to the bullet-point features of its genre.

This city is not just a place, it is a system

///

I used to run in the city. I lived where there were no parks to speak of, no jogging paths. But on weekends the City of London, that vast glass hub of finance and business, would empty out, its shops closed and its restaurants dark. I would run down avenues of skyscrapers lining wide deserted streets and not see another soul for minutes; the occasional lost tourist or bored security guard my only company. I would always wonder what was inside the vast towers that surrounded me, their mirrored surfaces obscuring their interiors, reflecting a clear sky as if they were trying to conceal something. Later, I got a job that involved me entering one of those towers, with a backpack full of hard drives and a security pass in hand, through multiple layers of guarded doors and surveilled corridors. Once inside I would walk through thousands of server racks to load those hard drives into the network, carefully removing them from their armored cases as if they were primed warheads. As I walked to and from the server rack, buried deep in those white-tiled pristine corridors, I always wondered what might lie within the thousands of terabytes of data that I passed through. The furiously blinking LEDs and coloured wires gave no indication of what they trafficked, and I was careful not to stop too long, aware of the cameras trained on my back. But as I walked I was reminded of my runs in the city, of those inscrutable towers containing whole worlds, dreaming there in the clear summer skies, dreaming machine dreams of you and me.

Mirror’s Edge: Catalyst contains something of this memory, hidden deep below its crude exterior. It has in its cyberpunk city and its radical architecture a vision worth more than the forgettable narrative it has been fashioned in service of. For now this seems to be the fate of many games, to waste powerful worlds on weak stories, but it doesn’t make it any less depressing that such a vision might be shackled to the onset of standardization, the all-conquering emptiness of the “open world.”

In this way, Catalyst also reminds me of those basement cafés, and their weak willed attempts to convince their customers that the concrete box they inhabit is somehow a continental fantasy, a piece of a pretty and benign golden age. This approach forgets that this concrete box, buried in the heart of the city, has qualities of its own, atmospheres more powerful than the soft light bulbs on fake brass candelabra might suggest. But follow the pipes, follow the wires, and they will lead you behind this facade, to that corridor of doors filled with potential, but marked with golden private signs. The next step is to reject the fiction, to kick those doors down, and run in and through the city, towards something new. In Mirror’s Edge: Catalyst that means turning off the unthinking guidance of your runner vision, embracing the elegance of the game’s free-running, and trying to outpace its cloying fictions, in search of the system and interface of the city beneath.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Mirror’s Edge: Catalyst, a radical city in a failed system appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers