Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 94

July 11, 2016

Civilization is coming to classrooms, and that’s a bad idea

If you wanted to find a small, distilled encapsulation of the Civilization series of grand-scale strategy games, you need go no farther than the musical trailer for Civilization IV’s (2005) original game and its theme song, “Baba Yetu.” The trailer depicts—as only Civilization can—the vast scope of human history, from the construction of the pyramids to the eventual exploration of Alpha Centauri. The song itself was the first piece of videogame music to win a Grammy. But even as the video portrays Civilization’s ambitions, it also demonstrates the series’ handicaps—namely, a kind of Western parochialism through which the series understands and presents various… well, civilizations.

The trailer echoes 19th-century philosopher Georg Hegel’s comment about how “World History travels from East to West” as it bounces from Rhodes to Rome to North America. For it is the Western narrative—specifically, the American one—that apparently represents the arc of world history. The trailer’s initial moments are set in the Eastern Mediterranean, while the penultimate beat of the narrative focuses on the American Revolution and the Emancipation Proclamation as emblematic of the history of the world. The lyrics of “Baba Yetu” function similarly: it is simply the Our Father prayer in Swahili, an example of the kind of ecumenicism that sees Christianity as the best representative of the sublime.

Civilization has always been marked by a well-meaning humanism

Hence the difficulty with CivilizationEDU, a version of Civilization V (2010) that will be used in classrooms to teach high-school students about history and the way in which geography, economics, and technological development affect that history. It’s impossible to critique the actual piece of edutainment as little beyond a general outline of its purpose has been revealed. But Civilization itself is a well-known formula, with the sixth iteration set for release in October, and its familiarity can only lead to concern over how the game’s systems will actually present history.

On the one hand, Civilization has always been marked by a well-meaning humanism. Every iteration of the base game and its expansions have tried to incorporate a wider and wider swathe of various cultures and civilizations. Civilization V is a good example of this aspiration: the base game had series stalwarts like the Aztecs or America, but also included Siam for the first time; the expansion Gods and Kings brought with it the ability to found a religion, or to have spies named for the various cultures they represent (James is a possible English spy, while Ur-zigurumaš is a possible Babylonian spy); Brave New World introduced the possibility of various works of visual art, writing, and music, meaning your Mayan museum could have Breughel’s “Tower of Babel” (circa 1563) and Zhang Zeduan’s “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” (circa 11th/12th century) in the same building—though the list of possible works neatly cuts off when we leave the public domain.

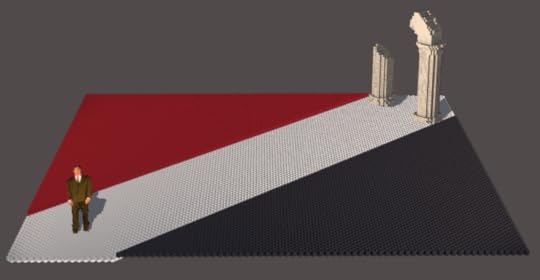

Ramkhamhaeng of Siam, Civilization V

Ramkhamhaeng of Siam, Civilization V

This interest has led to an education of some sorts by introducing audiences to parts of world history that they likely would never have encountered otherwise. If you Google Image search Mansa Musa—an emperor of the Mali Empire during the first half of the 14th century, and perhaps the wealthiest man in human history—among the first few images that pop up is his leader portrait in Civilization IV. Other civilizations include the West African Songhai, or the Inca, or Native American tribes like the Shoshone. In short, Civilization has always tried to show and tell of the sheer variety of human experience through various representations of human polities, across the globe and down the millennia. Added to this base presentation are the variety of civilizations available as mods to the base game—which include Canada, Afghanistan, the Maori, and others—and Civilization can present itself as a broad, open-ended celebration of human diversity.

On the other hand, this openness is belied by the way in which these various civilizations are presented as essentially Western in form and function. Take, for example, the technology tree, which presents scientific development as a linear process: chemistry leads to fertilizer leads to dynamite, and so on. But this structure misrepresents the actual history of science in favor of a modern, idealized form that has existed only relatively recently. First off, it’s far too neat, treating different discoveries like Lego blocks that build on top of each other. The reality was much more messy. When was chemistry actually ‘invented’? It certainly wasn’t during the Renaissance Era—the word chemistry comes from alchemy, which in turn comes from the Arabic al-kimiya, which in turn came from the Greek khemeioa, which may have come from the Ancient Egyptian name for their land: Khemet, “the land of black earth.”

The reality was much more messy

It would be fair to say that chemistry, as we moderns understand it, found its beginnings in the work of 17th-century moralist-turned-scientist Sir Robert Boyle, but for the fact that we cannot say the medieval alchemists who discovered how to distil pure alcohol or how to make aqua regia in order to dissolve pure gold were not doing chemistry. Civilization V’s built-in encyclopaedia states that it is 18th-century chemist Antoine Lavoisier who may be properly called the father of chemistry, but this is to ignore that Lavoisier relied upon the work that Boyle did, which in turn relied upon the work that contemporary alchemists like George Starkey (alias Philalethes) did. Indeed, scholars of the early modern era—such as William Newman and Lawrence Principe—use the term “chymistry” to name this messy moment when what we would recognize as chemistry began its slow evolution from alchemy. In short, the history of chemistry is a messy, complicated, and confusing narrative utterly unrepresented by its place in the Civilization tech tree.

In the same vein, the tech tree presents a kind of vision of science that is just as historically untrue. We are used to the idea that science is working, purposively, towards a kind of absolute truth—the grand, unified theory of everything that describes material reality perfectly. Concomitant with this conception is a process of continual correction and improvement: Isaac Newton’s theories of gravitations were correct, but superseded by Albert Einstein’s more correct model. Put another way, every step in the scientific ladder is succeeded by a more perfect one. Nevertheless, the history of science is littered with dead ends. The caloric theory of heat—wherein heat was an actual physical substance—is one example. Phrenology was another. Female Hysteria is a good example of a relatively recent medical theory that was often just a diagnosis for women who could not (or would not) fit within the conventional models of 19th-century femininity. Against the Civilization model of science—where every development is true, perfect, and a step onwards towards the end of the tech tree—stand these fundamentally mistaken theories. Even to describe them as dead ends is to presume a maze where there is a “correct” path that leads to an exit or an end, when all we actually have is the maze itself. One wonders what ‘dead ends’ we unknowingly find ourselves in now.

The same kind of criticisms can be applied to the way Civilization presents warfare or the development of cities. The image of armies butting heads with individual units being wiped out by volleys of arrows or musket fire works as an abstraction of the kind of warfare used by Westerners—Cannae or Agincourt is neatly represented by Carthaginian elephants or English longbowman. But the more ritualized forms of combat present in other world cultures are absent. There are no Aztec flower wars, where the purpose of combat was the acquisition of captives for sacrifice. There are no analogues for the kind of ritualized battles described in Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958). Similarly, the development of cities proceeds along a European vision: Early on, libraries and granaries are built. More complex buildings (opera houses, armouries) soon follow. This system makes intuitive sense for, say, England, but cultures that did not have cities as we understand them, like the Iroquois, are lumped into the same model.

Civilization is no less an abstraction than chess, and should not be criticized for that. But chess is abstract enough to permit few misconceptions about the actual, matter-of-fact nature of battle. Civilization, with its well-meaning sense of inclusion and its desire to present as wide a view of human… well, civilization as possible, is in a similar situation. Its purpose, as a game, is not to recreate history—how else can you explain the Babylonian capture of the city of Washington?—but to delight in it. Nods are given to the game’s models—the Iroquois receive a special longhouse building while the Aztecs’ special ability directly references their flower wars in that they receive culture for every unit they slay—in order to keep with the game’s good-natured interest in specific cultural diversity.

Its purpose, as a game, is not to recreate history

But Civilization as a game is distinct from Civilization as a teaching tool—even if the line between the two is blurred for CivilizationEDU. An educational tool bears a weight that a game does not: in the classroom, accuracy is required for any kind of real usefulness. Thanks to elementary school lessons, we are already stuck with the popular myths that Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue to prove that the world was round, or that the trade in spices with China was to disguise the flavor of bad meat. But when we learn the truth of things—that no educated person in the medieval era thought the world was flat, that the spice trade was lucrative because trade in luxury items has always been lucrative—it causes us to reflect on our past and ourselves, and on the essential similarities and on the profound differences. CivilizationEDU bears the risk of similarly warping students’ understanding of history if the basic mode of presentation is left to stand as is. In essence, it risks teaching students that science has always been a monolithic, linear project; that battles are like chess, where pieces are cleanly wiped out by others; that everything is fundamentally reducible to a Western experience.

Header image by manginwu

The post Civilization is coming to classrooms, and that’s a bad idea appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 9, 2016

Weekend Reading: Question-Phrased-Headlines of the Sphinx

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

Sure, you think Tetris is old? Think growing up with Tetris makes someone a real geezer? Guess what, Senet might predate hieroglyphics AND Tetris. So if you grew up with Senet you might be a literal fossil. Eurogamer’s Christian Donlan explores game design the ancient Egypt way.

Artificial Intelligence’s White Guy Problem, Kate Crawford, The New York Times

Artificial intelligence is one of those exciting-also-spooky frontiers that could change civilization as we know it, but as much as the basic pitch is a self-learned machine, it would still remain an echo of its creator. Kate Crawford explains how AI’s already biased towards their largely white male creators, and the dangers of those limited algorithms.

Agent 8: Intro, by Katie Skelly

Kill Screen Festival speaker and artist-we-really-dig Katie Skelly sat down for a chat with Kristen Korvette to discuss one of the most important topics: far-out space sex.

Why Flash Drives Are Still Everywhere, Paul Dourish, The Atlantic

We’re at least three medium shifts since vinyl records but people are still dropping dollars to collect the most analogue storage of music. The ongoing ubiquity of flash drives in an era of streaming and sharing may have more going for it than nostalgia, as Paul Dourish explains why they haven’t evaporated into the cloud.

///

Header image: Dr Irving Finkel and Dr Timothy Kendall, by Kirsty Saunders, via Eurogamer

The post Weekend Reading: Question-Phrased-Headlines of the Sphinx appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 8, 2016

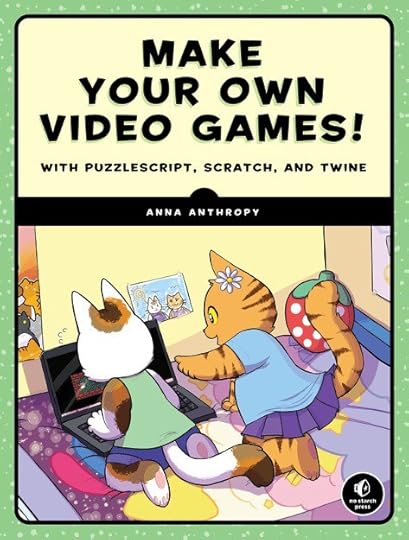

Anna Anthropy’s new book aims to teach game design to kids

Game maker Anna Anthropy is no stranger to book publishing. She’s contributed to multiple anthologies in the past, including Merritt Kopas’s Videogames for Humans (2015) and Seven Stories Press’s The State of Play (2015). She’s also written multiple works of her own, including 2012’s Rise of the Videogame Zinesters and Boss Fight Books’s 2014 critical overview ZZT. This November, Anthropy has another book planned for release. But her demographic is a little different: she’s writing videogame guides aimed at young kids.

Published by No Starch Press, Make Your Own Video Game!: With PuzzleScript, Scratch, and Twine is an all-ages approach to game design. Featuring cover art from Cassie Freire and technical advising from Kyle Reimergarten, Anthropy’s upcoming book will provide tutorials and resources for young developers to take their first steps towards building their own games. The work will include tutorials on storytelling in level design, developing puzzle games in Puzzlescript, and programming for Twine in CSS.

the resources they need to speak freely through their games

“I feel like my entire literary career has just been attempts to create the kinds of books I would have wanted when I was a kid,” Anthropy told me in an interview. “In fact, the dedication in my first book, Rise of the Videogame Zinesters, was based off the dedication in an Ed Emberley book I had as a child: ‘For the child I was, the book no one could write for me.’”

Anthropy’s work comes at a time when game design is more accessible than ever. Platforms such as Twine, Ren’Py, Fungus, and Scratch allow newcomers to create complicated games with minimal prior programming experience. By drawing on design tools that are free to access and easily distributable on the internet, Anthropy hopes to give young developers the resources they need to speak freely through their games. After all, she feels young developers are particularly intuitive when it comes to learning game design.

“Is teaching games to a young audience different than teaching to an older one? Not as much as you’d think,” she explained. “If anything, I think kids get it much faster because kids are much smarter than we are, especially when it comes to any kind of technology.”

There’s an interesting phenomenon already happening across videogames, where teens and young adults that grew up with game development tools are starting to come into their own. As someone who grew up with shareware development programs, Anthropy saw this first-hand. By giving today’s aspiring game makers the tools they need to design games at an early age, Anthropy is building the foundation for a future of game creation.

“they’re so less filtered than we are, it’s always amazing”

“I’m always excited to see the kinds of things child game-makers will produce—they’re so less filtered than we are, it’s always amazing—but I’m even more excited to see the kinds of things that kids who grew up making games are going to be capable of when they’re adults,” she said. “If you have a computer and an internet connection, you can do anything the book teaches.”

As game-making becomes more and more accessible, who knows what games today’s young kids will be developing over the next few years? Anthropy strives to give these developers the resources to start learning today.

Make Your Own Games! can be pre-ordered now on No Starch Press’s official website. Early birds can use the coupon code PREORDER to purchase the book for 30 percent off. Oh, and if you’re interested in Kill Screen’s involvement with supporting young game developers, you can check out our ongoing scholars program, sponsored by Intel.

The post Anna Anthropy’s new book aims to teach game design to kids appeared first on Kill Screen.

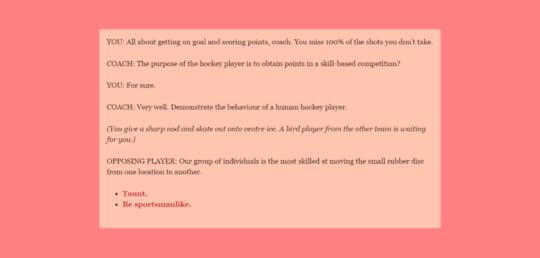

New female detective game seeks to right L.A. Noire’s wrongs

Ben Wander, a game developer with experience at BioWare and Visceral Games, has wanted to make a game about the 1920s for a while. After years of ogling independent game makers from afar, he finally dove in with a short demo of his upcoming detective game. The premise is that you have to interrogate the butler of a rich man, found dead in his home after an overdose. The newspaper you read that morning speculates suicide. The butler swears to find his killer. You click around his beautiful silhouetted living room and try to put two and two together to push your witness into a lie, though the clumsy truth/doubt/lie spectrum from earlier period detective simulator L.A. Noire (2011) is luckily absent.

heavily stylized artwork and no “doubt” button anywhere

Indeed, a brief look at the demo’s description makes comparisons to L.A. Noire inevitable. Solving crimes? Check. California? Check. Intriguing but not inaccessible period setting? Check. Inspired by Chinatown (1974)? Obviously check. But Ben Wander has no desire to repeat the mistakes that made L.A. Noire stutter. Gone is the realistic motion capture that promised to make interrogations believable, and then made them unbearable. Gone are the randomized holdovers from Grand Theft Auto IV (2008), shootouts that made protagonist Cole Phelps even more of a public menace than he already was. Gone is Cole himself, who I understood and mourned but never particularly liked. Instead we have a measured and competent private investigator—a woman, Wander reminds us!—with heavily stylized artwork and no “doubt” button anywhere.

The Ben Wander Murder Collection (a working title, though personally I hope he keeps it) looks instead to the Phoenix Wright series and recent smash hit 80 Days (2014) for nuance and personality. The colorblock art is as far away from Team Bondi’s work as possible: Wander lists Saul Bass and Olly Moss as inspirations, among others. Agatha Christie and the rest of the Golden Age mystery writers leak into each individual case, though they have been transplanted into the classic noir setting: seedy individuals, dark bars, jazz playing in the background. And lest you forget what America looked like in the ’20s, a newspaper clipping of an arrest reminds us about alcohol smuggling at the height of Prohibition; another muses about the fracturing Bolshevik party, a peripheral sentence in the demo that could be its own case within the full game.

The demo is only a few clicks long, but it’s more than enough to warrant interest. Wander’s devlogs promise much more in the works, with a travel system inspired by the board game Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective (1981), as well as a much larger plot that delves into the protagonist’s personal life. A release date is never mentioned, but Wander promises to post updates regularly, so I expect this murder collection is going to grow much larger in the future.

Check out The Ben Wander Murder Collection on itch.io .

The post New female detective game seeks to right L.A. Noire’s wrongs appeared first on Kill Screen.

There’s a game about exploring sexuality while fighting bird people you need to play

You know those moments between wakefulness and sleeping, where the edges of dreams get soft, and bits of them kinda seep into the real world? Now imagine that happening in the middle of the day, while you’re wide awake. And you’re at summer camp. This is more or less the premise of BIRDLAND (2015), An interactive fiction game, written by Brendan Patrick Hennessy and illustrated by Izzy Marbella, where all the anxieties and identity making moments of teenage-hood are complicated by robot-like anthropomorphic birds.

it’s the human aspects that are the backbone

Made for the 2015 Interactive Fiction Competition and created in Twine, BIRDLAND won six XYZZY Awards for Interactive Fiction, including Best Game, Best Writing, and Best Story. As much as anthropomorphic birds are a standout, and lend this story a whole bunch of intrigue, it’s the human aspects of it that are the backbone. This shows not only in the narrative, but also in how the choice and stat elements of the game work. There are six traits that can be boosted or reduced, depending on your dream-time shenanigans: serenity, alacrity, vigilance, melancholy, tenacity, and guile. When any of these traits are heightened, new paths can be chosen to respond to situations in your waking life in different ways. As Emily Short says about the game:

On the narrative level, the stats focus the player on the idea of developing personality rather than developing either skills or specific relationships…And one could easily imagine this same game done with stat checks on skills like canoeing and pottery, to reflect the player’s summer camp activities. Instead, this particular choice of stats redirects our attention to the protagonist’s developing personality as a top concern.

The game also, in the midst of its oddball humor and teenage self discovery, tackles issues of figuring out one’s sexuality. The game’s protagonist, Bridget, spends a lot of the game trying to figure out her feelings for one of the other girls in the camp, Bell, and awkwardly dodges questions about what boy she has a crush on. This moment of dodging is a deeply relatable moment for anyone whose experienced the possibility of being unintentionally outed in casual conversation. This being said, Bridget’s sexuality is not a major conflict of the writing, but rather treated as part and parcel of figuring herself out generally.

For a game that features a dream world and a waking world in nearly equal measure, and then goes on to mix the two, BIRDLAND maintains a cohesion, and believablity throughout, precisely because it takes time to take its characters and their teenage lives seriously. Even the smallest choices between “uh…” and “err…” feel like they matter here. One of the best lines from the game, shared by Bridget and her love interest, is likely the best way to explain it, “Trust me. It all makes total sense when you’re in the middle of it.”

Be sure to keep up to date with Brendan’s work through Twitter, and check out BIRDLAND. The game also has “a kinda sorta prequel” you can check out called, Bell Park, Youth Detective.

The post There’s a game about exploring sexuality while fighting bird people you need to play appeared first on Kill Screen.

Thank god the new God of War isn’t set in Ancient Egypt

When Sony kicked off their E3 press conference this year by announcing a new God of War game, it confirmed rumors that Kratos would be taking his God-slaying talents North to Scandinavia. It was later revealed that developer Santa Monica Studio had also considered Ancient Egypt as a possible setting for the next act in Kratos’s story. The game’s creative director, Cory Barlog, said in a roundtable interview with Eurogamer that, “for me, as I looked at both [Egyptian and Norse mythology], Egyptian mythology is about the pharaohs as embodiments of the gods on Earth and there’s a lot more about civilization—it’s less isolated, less barren. I think at this time, we really wanted to focus on Kratos. Having too much around distracts from that central theme of a stranger in a strange land.”

There is a lot of subtext to unpack in Barlog’s statement. Taking his assessment of “pharaohs as embodiments of the gods” it would seem that a God of War set in Egypt would task players with assassinating human Gods. This inherent connection to the actual people of Egypt, not just their pantheon, could present a bit of a problem. Firstly, the idea of a white Kratos essentially invading a land that belongs to people of color, where he proceeds to slaughter them and their entire belief system is, to say the least, uncomfortable. In fact, it would likely raise the same concerns as Resident Evil 5 (2009) did, in which a white man trudges around a fictional African country shooting the natives—who are infected by a vicious parasite. You could argue that the same applies to God of War’s treatment of the Norse, but the racial undertones are not as prevalent in such a case, and Barlog has made clear that the game takes place before Norse civilization has properly begun to form, thereby eliminating potential bystanders.

Game studios are right to be wary of Egypt

This is a convenient workaround for Barlog and his team to adopt and it’s one that wouldn’t have been as available with the initially proposed Egyptian setting. Game studios are right to be wary of Egypt even if it is a shame that it’s overlooked. You only need to glance sideways to see the stigma that Egypt has picked up as a setting for fiction as of late due to the wildly inappropriate and offensive Hollywood films Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014) and this year’s Gods of Egypt, in which white actors were cast to play Egyptians. That’s nothing too unusual for Hollywood, but it has come under increased racial scrutiny due to Exodus director Ridley Scott’s crass remarks on the subject: “I can’t mount a film of this budget, where I have to rely on tax rebates in Spain, and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such.” In addition to the aforementioned movies set in Egypt, recent examples of whitewashing in movies include Emma Stone being cast as a character of Chinese and Hawaiian descent in 2015’s Aloha. 2010 saw Jake Gyllenhaal infamously cast as the protagonist in the Prince of Persia movie, while this year’s reveal that Scarlett Johansson would be playing the Japanese protagonist in the upcoming Ghost in the Shell movie caused quite the internet uproar.

Whitewashing doesn’t only exist when white actors are cast to play people of color, but also when movies about people of color are centered around a white actor. The Last Samurai (2003), Dances With Wolves (1990), and The Help (2011) are all examples of movies about white people entering and integrating themselves into communities of color. This type of whitewashing can easily affect videogames as well. The aforementioned Resident Evil 5 (2009) was guilty of it, so too was Far Cry 2 (2008) and Far Cry 3 (2012) to name but a few. But here’s the big difference: Hollywood can argue that it looks to cast the most popular actors in its movies, nearly all of which are white, while videogames are complete fabrications built from the ground up that need not worry about the ethnicity of real life actors nor a pitching process like the one Scott references. While making a game about a white protagonist in a land belonging to people of color is ill-advised, making a game about a white protagonist slaughtering people of color on their own land is best avoided altogether. And it can quite easily be avoided.

To flip the argument for a second, while there are certainly reasons to avoid Ancient Egypt, there are also myriad reasons to embrace Norse mythology, as Sony Santa Monica has done. Thanks in large part to the Marvel Thor movies, large audiences are innately familiar with Norse pagan myth. Characters like Thor, Loki, and Odin are at least, if not more, recognizable than Zeus, Poseidon, and Ares. Not to mention the high number of fantasy videogames set in locations derived from Scandinavia and embedded in Norse culture—The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011), the Neverwinter Nights series, and World of Warcraft (2004) to name some of the most popular. The pop culture zeitgeist has embraced Norse mythology so there’s already an existing appeal to bank on. Egyptian myth, while probably the third most widely-known pagan pantheon, still remains somewhat esoteric, at least when you speak in terms of mass audiences. However, the biggest reason to embrace Norse mythology is probably the natural environment the region of Scandinavia presents.

a place designed for small details to show and intimacy to unfold naturally

Consider that the original God of War games relied heavily on massive architectural monuments as settings. These provided linear paths that were filled with grandiose spectacle. The setting of these games matched their overall tone and brutish action—everything was over the top. While environments were completely fictional, Greek civilization is old enough and iconic enough that the opulent classical Greek iconography fell within the realm of plausibility. What’s more, the urban environments often gave Kratos ample opportunity to assert his status as an anti-hero by slaughtering dozens of innocent people—they helped to feed the narrative.

A God of War game set in Egypt would also likely have to rely heavily on civilization and urban environments. Egypt, after all, is one of the oldest civilizations on earth and was responsible for some of the grandest architectural structures of the ancient world. While the Giza Pyramids are by far the most iconic monuments of Ancient Egypt, the Egyptians were proficient in other forms of religious and civic architecture as well. Before the Greeks had perfected their Doric columns, Egyptians had Papyrus capitals. Before Greeks built basilica temples, Egyptians constructed massive hypostyle halls like the one at the Karnak Temple Complex. Outside of the Nile Valley and Delta, the Egyptian desert landscape leaves much to be desired in terms of topography and environmental diversity and almost necessitates a focus on cities. The desire to leave the city behind in hopes of differentiating the new God of War from the old ones calls into question the nature of the Egyptian city versus the pastoral landscape of Norse myth.

If you need more evidence for the change in tone and setting, look no further than the changes to the game’s camera. Gone is the fixed cinematic camera of old God of War games, to be replaced by a more traditional, player-controlled third-person camera. The perspective has shifted so that the player’s view is positioned much closer to Kratos, from where they can frame him against the surrounding environment as they please. Another big difference, as shown in in the E3 trailer, was the noticeable texture of bark on a tree. While the original God of War games have always been graphical powerhouses on their respective machines, they rarely focused on such detailed environmental depictions, and seldom positioned the camera close enough so that this lack of detail was obvious. The forest setting of this new God of War game brings, in every sense, Kratos and his world closer to us—it’s a place designed for small details to show and intimacy to unfold naturally. It seems primed, at least on a visual level, to evoke the relationship between hunter and prey, teacher and student, father and son. The change of setting was necessary, then, as it is difficult to hit the emotions this God of War aims to when screaming on the back of a massive titan. It seems no coincidence that three of the first four games Sony showed at its press conference (God of War, Days Gone, and Horizon Zero Dawn) all isolate their protagonists in very similar forested environments.

While the setting of an over the top and grandiose Ancient Greece fit the tone and style of the original games, it is clear that this God of War is aiming for something altogether different. It’s a quieter, more subdued God of War, one that has room for compassion and intimacy. Such a focus could easily be overrided by the whitewashing that an Ancient Egypt setting for the God of War series would require. Still, it does seem a shame that the option was sensibly rejected. Perhaps one day we’ll have a modern blockbuster game brave enough to take on the Egyptian setting and do it with a native of the land, and with rumors that the next Assassin’s Creed title will take place in Ancient Egypt, perhaps we won’t have to wait long.

The post Thank god the new God of War isn’t set in Ancient Egypt appeared first on Kill Screen.

It might be impossible to stop grinning at Burrito Galaxy

When someone talks about nostalgia in videogames, there’s a solid chance they’ll also be talking about Metroidvanias or slick indie platformers. Super Meat Boy (2010) ends up being notable for its tight air control and precise jumps—the weird setting and throwback cutscenes are kind of a bonus.

But from what I can tell, the upcoming Burrito Galaxy has nostalgia mostly for the weird worlds games let us inhabit. When the vaguely dissonant squeaks of the soundtrack from the new video started to play, I couldn’t help but grin: it sounds like someone made the Wii Shop Channel soundtrack play a game of Dizzy Bat. As the charming old lady twists left and right, her speech is communicated through the cheeriest gargling noises you can imagine. She lives in a tree that is also her husband, named Trunko.

a “first person platformer/adventure/ski/story…?”

From the wobbly text effects to the big goofy slap the protagonist (named Guac) dishes out when they want to talk to another character, Burrito Galaxy looks a lot like something that would have appeared on the GameCube, capturing a weird charm I remember from Nintendo games of my youth not because it parrots them, but because its cuteness has its own brand of imaginative weirdness to it. It’s charming and nearly inscrutable all at the same time.

This video gives a little bit of insight into something that looks like a quest—the player is tasked with finding Plepa and Trunko’s son, perhaps up to no good or in danger caused by the “strange happenings” in the forest. Either way, Guac gets a couple USB drives with a map and a letter, which do seem like the traditional trappings of adventure games or side quests. Either way, I’m still not clear on what the game’s going to be when someday it pops into the world fully formed—in their own post on Reddit, one of the creators called it a “first person platformer/adventure/ski/story…?”—but I am looking forward to being able to find out at some point.

You can find out more about Burrito Galaxy on its website and also sign up for its newsletter over there too (which it totally worth it).

The post It might be impossible to stop grinning at Burrito Galaxy appeared first on Kill Screen.

Paradise Lost reimagined as a SNES game

The SNES JRPG aesthetic has always had a certain charm. From chiptune album covers to horror stories about haunted game cartridges, many artists seem to gravitate towards the pixel art found throughout Nintendo’s RPG releases of yesteryear. What appears as a simple solution to the console’s limited system RAM actually presents a design style capable of extremely complex and fascinating artwork. Just take a look at the gorgeous backgrounds seen in Tales of Phantasia (1995) or the character design behind Square’s Chrono Trigger (1995).

London-based electronic music duo Delta Heavy is the latest artist to adopt that classic aesthetic, with their new music video for White Flag, which remixes John Milton’s iconic blank verse poem Paradise Lost (1667). Created three months after its original Paradise Lost album release, Delta Heavy’s music video features a fallen Satan returning to Heaven in order to apologize to God. Things don’t go quite as planned, as Jesus strikes down the Devil, and plummets below to Earth.

Perhaps most beautiful of all is Satan’s descent

“‘White Flag’ is about letting your guard down in love,” said director Najeeb Tarazi, who previously worked as a technical director on such movies as Toy Story 3 (2010) and Monsters University (2013). “I wanted to try turning the myth of Paradise Lost on its head and tell a story where Satan apologizes after his defeat and seeks a path of love. In reply to Satan’s apology, God brutally punishes Satan again.”

The SNES twist on Paradise Lost oddly mirrors many of the religious themes found in JRPGs during the ‘90s. Shin Megami Tensei II (1994) has the character YHVH, a metaphorical creator figure (and villain) who seemingly represents fundamentalist Christian interpretations of an authoritarian God. Whereas Nintendo’s Earthbound (1994) features a classic ending sequence where the entire world prays for the strength to defeat the evil alien invader, Giygas.

Nonetheless, Tarazi’s take on Paradise Lost is absolutely gorgeous. Characters such as Beelzebub are represented in striking palettes of bright red and grey, whereas God is portrayed as an all-powerful—yet oddly majestic—mother figure hovering in the distance. Perhaps most beautiful of all is Satan’s descent, as he falls from a light shaft in space and trickles down to Earth amidst bustling clouds parting between the stars.

Check out the music video first-hand over on YouTube and head over to Tarazi’s website for more of his work.

The post Paradise Lost reimagined as a SNES game appeared first on Kill Screen.

New videogame asks: do we really need academics to study videogames?

When I was born late into 1990, the Super Nintendo had already been released in its home country of Japan. Over here in the States, Super Mario Bros. (1985) had already been entertaining my parents for years. Pong (1972) had entertained my pastor, and Tron (1982) had already hit theaters to the collective “meh” of audiences worldwide. As such, I have only ever known a world with videogames. But it’s worth pointing out that, relative to text or music or even film, videogames are still a fairly new medium. And as with any new medium, its invention has lead critics and academics to develop new language for discussing it.

Take terms like “ludonarrative dissonance,” which describes the disconnect players feel when their actions in a game don’t match up with the story being presented to them. The term was only first proposed in a 2007 blog post on the then newly-released BioShock, and even taking into account prior discussions on the topic that did not directly use it, most only date back to the early 2000s at the oldest. This does not necessarily make the term incorrect or a poor representation of the topic it’s discussing, but it does mean that there is still time before it is taken as general knowledge for others to present alternative terms that might be able to better represent the idea, or to discuss if the issue raised by ludonarrative dissonance is even much of a problem in the first place.

In their new game Game Studies, Pippin Barr of games like last year’s Best Chess and Jostle Parent, and Jonathan Lessard of games like 2014’s A Tough Sell and this year’s Rogue Solitaire, call some of of gaming academia’s most prominent truisms into question. A series of five short levels, the game is simple: get the man to the goal by clicking on the ground until he walks there. Along the course of each level, the game will lampoon one of five different theories, whether by having the player dive into a pool to demonstrate “immersion,” having them walk into a circle to demonstrate “the magic circle,” having them play baseball while listening to Snow White to demonstrate the conflict between “ludology and narratology,” and the like.

the game will lampoon one of five different theories

Notable among all these levels seems to be a general insistence that perhaps gaming academia is being a touch obtuse and generous in their discussion of these topics. For instance, while popular flow theory advocate Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi might argue that “flow” in a game is a special state of hyper awareness and enjoyment, Game Studies presents it as more of a tool of manipulation, just a simple method for getting the player to stay on a prescribed path rather than challenging the developer’s intentions. The same applies to Game Studies‘ depiction of the “magic circle,” or the thought that virtual worlds should provide an escape for the player and insulate them from reality. While this could perhaps be compared to the theatrical tradition of suspending one’s disbelief while watching a show, Game Studies presents it as more of a shallow constraint that anything else—step from a larger outside space into the more constrained circle and you get fireworks. Yay you! Not much else to do when you get there, though.

“While the academics sit in their ivory towers thinking about postmodernism,” writes Barr in the game’s factsheet, “Game Studies will be out there in the trenches, educating the public on the theory of games through the most painfully obvious physical metaphors for game studies concepts we could come up with.” He then goes on to discuss that, jokes aside, the idea behind Game Studies was to interrogate the question of whether games can be used as educational tools at all, or if trying to take difficult, abstract concepts and teach them using aesthetically-pleasing, fun systems of play dilutes the ideas a bit. Like the rest of the game, this questions another popular topic in game studies—gamification.

For instance, if a game is tailor-made to please the player, then can they learn the material, or does the lack of academic challenge mean that they are simply repeating the steps intended by the designer without considering what is being taught? For an extra bit of meta, Barr and Lessard then decided that the best way to pose this question would be to try to use a game to teach players about game studies itself, and seeing if they leave understanding it better or, rather, if they feel like they’ve been patronized to.

The game is available to play for free over on Barr’s site, and the end credits contains a full list of the references Barr and Lessard used while making it. While the game can be breezed through in roughly 10 minutes, reading through the sources will obviously take longer. But doing both raises the question: can a game teach someone about an extrinsic topic like academic theory—and can it succeed in making that learning process fun—or are you better off just sticking to the original text?

To play Game Studies for yourself, visit its website. To keep up with the rest of Barr’s work, follow his Twitter.

The post New videogame asks: do we really need academics to study videogames? appeared first on Kill Screen.

To West explores the inherent slowness of vast landscapes

The power of the engine doesn’t matter—it is the landscape which dictates the speed of a train. Some journeys are staccato and breathless, clusters of urban interest barely spaced, laying down a beat over which the melodies of weather and light might play. Others are long drawn-out sighs, exhales as long as a country, made even slower by the occasional point of basic interest; a tree or ruin. Most waver between the two, playing out the time away from work, life, routine and rote in an almost mischievous way. Once you board a train, you leave your life behind, you will have to pick it back up at your destination.

The dust, the amber light, the metal shell of the train

It is these qualities that To West seems to play with. Pol Clarissou, creator of the meditative Orchids to Dusk (2015), designed it as an entry to itch.io’s “Mystic Western” game jam, a competition that produced a rich set of experiments, including Conor McCann’s heat-locked conversation Black Gold, and the lo-fi wanderings of Kyle Reimergartin’s Ded Zome. To West marks itself out by being barely interactive, its lone input being the almost unnoticeable movement of the camera, bound to the mouse. This is an experience that wants you to be taken away from the controls for a few minutes, to step onto its simple, silhouette train, and ride it through two days of blistering sun and two nights of wandering visions.

For me, the vast desert and warm tones of To West bring to mind the longest train journey I have ever undertaken, the 24 hours from the golden city of Jaisalmer, in the midst of India’s great Thar Desert, to the ancient heartland of New Delhi. The dust, the amber light, the metal shell of the train all stay with me, as does the profound slowness of the landscape. Sitting on the edge of an open door, watching the disc of the sun, muted to a simple graphic object by the layers of sand and dust in the warm air, I found myself slipping beneath the rhythms of crossing a desert, the featureless landscape refusing to recognize my presence, or the hyperactivity of my life—only the inhumanly slow processes of erosion, decay, displacement.

In reality, To West is not as slow as this. It cannot even begin to invoke the vastness of time that can be opened up by such a journey. Yet, in its forcible arrest of our attention, especially when placed within the hundred-clicks-per-minute context of our computers and devices, it gestures at such experiences. There is no narrative to be found in To West, no true pattern, no real meaning. All of these elements would provide some relief from the stillness which dominates this constantly scrolling canvas.

Instead, To West’s only thread is the haunting music of Hibou Blaster, filling the empty space with rich tonal shapes that shift almost imperceptibly. Placed alongside the occasional abstract visuals, which have all the over-saturated beauty of a memory-to-be, To West manages to be, even in its short and simple form, something of a journey. Like a train, it picks us up in one place and leaves us in another, and as passengers our only task is to try, impossibly, to understand what might have changed while we were away.

You can download To West over on itch.io.

The post To West explores the inherent slowness of vast landscapes appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers