Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 91

July 14, 2016

What would a trump presidency mean for esports?

Unless you have been living under a stack of StarCraft II: Wings of Liberty Collector’s Edition boxes for the past year and a half, you’ve probably heard that a six-foot-tall, pasty, third-grade-vocabularied sack of racist bile and vitriol, ensconced in an expensive suit and a greasy toupee, has a small but non-negligible chance of becoming the next president of the United States of America. Approximately six billion trillion words, across every publication this side of the asteroid belt, have been written on the potentially disastrous ramifications of this misanthropic cheese golem getting his hands on America’s Supreme Court, nuclear arsenal, and wall-building capabilities. This article explores the potential effects of a Trumpocalypse on perhaps the sole arena nobody has thought to write such an article about: the vibrant, burgeoning, and fundamentally international phenomenon known as D I G I T A L S P O R T S.

It’s not just that Donald Trump hates videogames. (“Video game violence & glorification must be stopped—it is creating monsters,” he tweeted after the Sandy Hook massacre in 2012). The problem is that Donald Trump bases his entire platform on xenophobia and keeping people out of America, making him a natural enemy of esports, which is all about people from around the world coming together to compete, often in venues that happen to be located in—you guessed it—America. Esports athletes already have plenty of trouble getting visas; just ask Super Smash Bros. Melee player William “Leffen” Hjelte, for whom not even 118,000 signatures and a White House response on a petition back in May were enough to secure passage into the States by this weekend’s EVO.

Trump is the natural enemy of esports

Getting a U.S. P-1 athletic visa, as all serious international esports competitors are eventually forced to do, is already hard. The visa process is an arduous journey across a landscape of paperwork mountains and red-tape jungles. It’s a ritual so complex and arcane that it practically necessitates an entourage of lawyers, and even when every precaution is taken, the fate of the application ultimately comes down to factors like how cranky and bloated the relevant customs official feels on the morning in question. All day long, in the bowels of whichever crumbling Washington mausoleum the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) occupies, men and women squint through bifocals at imposing sheafs of paper output by the multibillion-dollar immigration law industry, and try to answer questions like: does this Chinese/Swedish/South American/etc. person who claims to play videogames for a living actually count as an athlete?

Donald Trump doesn’t have to do much to make things worse. His mere election would send a signal that it is okay to hate and fear foreigners. Were such a message to trickle down through the USCIS organization, say because Trump put one of his foamy-mouthed cronies in charge, the all-important ground-level customs officials might become more suspicious, and thereby less inclined to deem fringe cases like esports valid justification for an “Approved” stamp.

Visas are a concrete example, but the more insidious threat of a Trump presidency is less tangible. Take the case of Syed Sumail “Sumail” Hassan, one of the youngest and most recognizable faces in the Dota 2 scene, whose family recently immigrated to America from Pakistan. Would Sumail have made it into America and become a central pillar of Evil Geniuses, the most successful North American Dota 2 team, in Trump’s world? Not if the blustering bankruptcy tycoon’s proposed ban on immigrants from areas of the world with a history of terrorism had been in effect. Children of immigrants fill the ranks of America’s esports teams; harsher laws might deny the Greatest Country on Earth™ its next generation of players.

Children of immigrants fill the ranks of America’s esports teams

Then there’s the rest of the world to think about. Xenophobic American policies might provoke other countries into erecting similar restrictions. In a post-Brexit, closed-border era, esports might be segmented into regional pockets, the way it was before an infusion of money and viewership made it possible for tournaments to fly players halfway around the world every other month. Small, fragmented esports scenes have a tendency to stagnate; the modern competitive landscape is interesting precisely because it involves such diversity of players, mindsets, and strategies.

Of course, there’s also the chance that President Dumpster Fire might drown the world in a nuclear conflagration, which would definitely be bad for esports. Or at least bad for the Melee scene: I have trouble envisioning even the most disciplined team of mutated cockroaches executing waveshines and L-cancels.

The post What would a trump presidency mean for esports? appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Silver Case HD completes the 17 year localization of an iconic videogame trilogy

Goichi Suda, or Suda 51 as he is often known, can be a hard person to pin down. His work, especially in recent years, has been accepted into videogame culture as “crazy” or “weird,” identified as flippant stories filled with self-referential non-sequiturs and mulched manga plotlines. “Oh it’s just crazy old Suda,” seems to be the standard response to his work, and you can drown in articles that introduce him as “the Tarantino of games.”

This is a side effect of his breakthrough game perhaps, the otaku assassin simulator No More Heroes (2007), which cemented him as a master of the perverse and the throwaway, its breathless pop-culture mutations driving home the idea of a Suda as a colorful clownish persona. It’s a persona that Suda has himself propagated in recent years, seeming to respond to the popularity of No More Heroes by trying to bring the same barrage of colorful, perverse, brash ugliness to games like Lollipop Chainsaw (2012) and Shadows of the Damned (2011). For those who were introduced to Suda with No More Heroes and the sneering Travis Touchdown, this progression might seem logical, but for those of us who caught him earlier in his career, things look altogether different.

“an environment that let me create everything I wanted to create”

“Kill the past.” It’s a phrase that, to fans of Suda’s work before No More Heroes, will be intimately familiar. The loose title for the trilogy of works he produced after founding his studio Grasshopper Manufacture, namely The Silver Case (1999), Flower Sun Rain (2001) and Killer7 (2005)—it suggests violence, regret, and the pervading presence of memory. The first of these, The Silver Case, has never been released outside of Japan, that is, until this year. Quietly announced back in May, Suda himself is directing a remaster and English translation for release this fall. Recently appearing at Bitsummit in Kyoto, Suda demonstrated the game in video form, showing it for the first time with English dialogue. This makes it the final chapter in a process of localization that has taken almost two decades.

The Suda 51 of “Kill the Past” is a different Suda than that of his late, Western-oriented games. It’s perhaps important to note that No More Heroes was, in fact, the last game Suda directed, choosing instead to take on overseeing roles such as creative or executive director since then. In a recent interview he even told Kill Screen that currently he “has a lot of input” but “doesn’t really see [himself] as a lead or artistic kind of director,” preferring to set up the scenario for a game and its team, rather than painstakingly manage every detail. The Suda of the “Kill the Past” era was a very different beast. In 2015’s The Art of Grasshopper Manufacture, he talks about how, encouraged and guided by Shinji Mikami, he made Killer7 “practically with my own hands.” He adds that Mikami “provided an environment that let me create everything I wanted to create. That kind of development is rather rare. I haven’t had an experience like that since.” This approach is what marks out those games from the rest of his body of work.

As said, The Silver Case is the last remaining game of that era to make it to the West. And with Suda now no longer closely directing his games, and the Western market dictating a change in his approach, it represents what might be the last great Suda 51 game. Speaking again in The Art of Grasshopper Manufacture he explains how it was inspired by Jean Luc Goddard’s experimental cinema: “Godard challenged the use of visual and audio multi-expression techniques. I wanted to make a game that did the same: something that can’t be deciphered in just a single glance.” For Suda this was a struggle, especially in the late 90s. This was, in Suda’s words, “a time that many people decided ‘video games are justs for kid after all.’” He wanted “No rules on the breadth of expression” integrating illustration, 3D models, live video, photography, and typography. But this brought him up against filmmakers and technicians that didn’t share his vision. “People made fun of the game. They felt ‘you can’t take pictures that don’t connect from beginning to end,’ and they wouldn’t start the camera.” It was “a battle,” but the result was something that, despite everything, Suda ranks among his best work. “I really wanted to go down the path of making a game in a way that no one had ever achieved before. The Silver Case is like the history of that battle.”

Suda seems to have delighted in frustrating the player

What is The Silver Case then? I suppose we might call it a visual novel, but like the games that would follow it—the looping adventure puzzler Flower Sun Rain, and the hard-boiled surrealist shooter Killer7—genre feels like a reductive way to describe it. It is, in the simplest sense, a piece of twisting, ornate interactive fiction, one that changes its presentation style at an alarming rate, and shifts between geopolitical machinations and oddball dialogue without warning. The same might be said of those other two entries in the “Kill the Past” trilogy, a trilogy that perhaps is better thought of not as a series, but as an analog to Park Chan Wook’s Vengeance trilogy, or Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy, as being an exploration of themes, a process of experimentation, and a method by which each director might hone their craft.

Like those, and other great artistic series, “Kill the Past” is powerful because it represents an exploration of an artist’s own identity, and, like many do, culminates in their greatest work: in this case, Killer7. But while Killer7 might be Suda’s own “proudest moment” it lies incomplete without the games that birthed it. Flower Sun Rain received its English localization in an unlikely DS port (subtitled Murder and Mystery in Paradise) in 2008. One which is still well worth searching out for it’s Groundhog Day (1993) structure and entirely numerical puzzle design. The Silver Case was supposed to follow, but it disappeared, perhaps after low sales and the poor critical reception of Flower Sun Rain. Eight years later and The Silver Case is finally getting the same treatment, though whether its reception will be equally frosty is hard to judge. These are difficult games, conceptually ornate, and unfriendly towards those looking for answers. Suda seems to have delighted in frustrating the player, perhaps in the same way as his favorite writer, Franz Kafka, who in The Castle (1926) entwined the reader in a plot that goes nowhere, on a mission of decreasing importance, within a cast of characters prone to distraction.

This frustration, obscurity, challenge and otherness is also what makes the “Kill the Past” games so enticing. Unlike Suda’s easy-to-please late work, that seemed desperate to break the Western market at any cost, here were a set of works that dared to be overtly serious, impregnable and unfriendly. Perhaps it is appropriate that their process of localization has been as ornate and bizarre as their narratives, it suggests that, even after two decades, these masterpieces might still have some secrets left to offer.

The Silver Case HD is due to arrive for PC this fall.

The post The Silver Case HD completes the 17 year localization of an iconic videogame trilogy appeared first on Kill Screen.

Long Gone Days imagines the world of war that’s coming for us

If a dystopian novel was written about the world that we live in right now, what would it look like? Chilean game maker Camila Gormaz wants to explore that in her upcoming game Long Gone Days. Unlike dead-Earth dystopias, where human society has overreached to such an extent that what remains of our planet is barely recognizable as the remains of what we see today, Long Gone Days takes place… soon. Say, the next 10 years. Rourke, the protagonist, abandons his post as a military sniper and ventures out into the world. He’s in an isolated area and the war proves inescapable, so what that means for the ruins of 2016 to 2026 remains to be seen. Rourke, whose story is described as “looking at mundane things […] through the eyes of a child” will discover it right along with us.

Long Gone Days will have a significant number of battles, though, they’re not the focus of the story. Two different kinds of battles—turn-based combat and a “sniper mode”—are augmented by a body-targeting system familiar to anyone who’s ever played Fallout 3 (2008), both of which are on display in the trailer, while Morale is a tracked factor that can be affected by your interactions with your party members. Each NPC is different; it’ll require more than just a pep talk to get your characters through every battle alive.

However, another mechanic may prove more interesting. Long Gone Days won’t follow the convenient practice of a universal language that makes other “international” games so dull. Instead of giving characters clumsy accents to signify their country of origin, Long Gone Days has them speak in their native language and requires you to recruit interpreters to interact with them: this includes buying items, accepting quests, etc. A small role, maybe, but an important one.

it’s not only the soldiers shooting guns that are crucial to a war

Translation is a notoriously overlooked skill. True, the best translators should be invisible, but society can’t function without them. How much of our modern, globalized world would be accessible without translation? More specifically, if you were thrown into a foreign country where you didn’t speak the language and had to buy bullets for your little pixelated gun, how much use would you be?

That’s where Long Gone Days’ interpreters come in handy. Not only do they add realism to a game that deals with international military, but they bring into the spotlight something that people often forget: it’s not only the soldiers shooting guns that are crucial to a war. Translators, like countless other unarmed roles, play a role that bigger and better guns can never fill, not in any science-fiction future—Uhura is a translator, y’all—and not today on Earth. Long Gone Days will make sure the importance of this role isn’t being forgotten.

Check out Long Gone Days’ demo on GameJolt and itch.io , and back it on Indiegogo .

The post Long Gone Days imagines the world of war that’s coming for us appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Hex, a new mystery from one of videogames’ greatest tricksters

At its core, one could shave down a detective story to three basic questions: who, why, and how. Who was the victim, who was the perpetrator? Why and how they did commit the crime? From Sam Barlow’s FMV mystery in Her Story (2015) and Cole Phelps’ investigations across the seedy streets of 1940s Los Angeles in LA Noire (2011), to the forensics of CSI and the mental deductions of Sherlock, those questions drive players and fictional sleuths alike. Often the answers to the “how?” and “why?” are easy to fathom—jealousy, revenge, greed, and so on—but what happens when victim and perpetrator aren’t bound by the logic and conventions of reality? What if they were videogame characters? The Hex hopes to answer that question.

Daniel Mullins’s debut was the odd and subversive Pony Island, a game that was definitely only about ponies and not about tortured souls in hell… His follow-up may leave the ponies behind, but the aspects that made Pony Island memorable—“games within games, inverted expectations, and a heavy helping of secrets”, according to Daniel himself—remain, filtered through a new lens of hidden motives and gaming archetypes in The Hex.

Six characters, with secrets of their own, waiting out inclement weather in an isolated tavern. Each one modeled after a classic videogame protagonist: the Space Marine, the Platformer, the Apocalypse Survivor, among others. And then a garbled call in the night, that someone will be murdered before morning. Who and why are questions for you to answer, and you do so by switching between the characters to explore the tavern and interact with the others.

the mystery won’t unfold so simply

Of course, like many of these stories involving people trapped together with dark secrets and motives simmering under the surface, the mystery won’t unfold so simply. In fact, the characters aren’t even that concerned about the looming threat of bloodshed. “However, it seems that despite your efforts, none of the characters are interested in discovering the would-be killer,” Mullins explains. “They are all preoccupied with hidden motivations that are uncovered over the course of the game.”

As those hidden motivations are uncovered, The Hex evolves into something more than a clever gaming-themed mystery. Each character’s backstory is playable, presented in the form of each protagonist’s respective genre. The Space Marine annihilates alien threats in top-down shooter fashion, the Platformer runs and leaps through vibrant side-scrolling levels, while the Survivor engages in turn-based tactics. Given Mullins’s tendency to twist expectations in Pony Island, one can only imagine that those roles won’t remain so rigid.

The Hex will be available on PC, Mac, and Linux in early 2017. You can learn more about the game here.

The post The Hex, a new mystery from one of videogames’ greatest tricksters appeared first on Kill Screen.

Zero Time Dilemma cuts like a knife

Zero Time Dilemma wants to know how it feels to kill someone. To take someone’s life, whether it’s to ensure your own survival, or someone else’s. What it’s like to be driven mad when you end up in a situation like its protagonists—trapped in an underground shelter, where initiating six acquaintances’ deaths is the only hope for freedom. Zero Time Dilemma wants to answer these questions. But the truth of the matter is that it depends on who you are, where you are, and the context of the situation. And, of course, this being the Zero Escape universe, it also depends on what timeline you’re in, and what kind of person you are within that specific history.

True to its topsy-turvy namesake, Zero Time Dilemma is the third game in the series but actually falls somewhere in between the first two games: 999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors (2009) and Virtue’s Last Reward (2012). This peculiar chronological placement isn’t too surprising for a series that is known for its unconventional storytelling with as many branches as an ancient, gnarled tree. And Zero Time Dilemma is keen to follow suit, its splintering story overloaded and fractured to a thrilling effect. The story can go any way imaginable—from everyone coming away completely unscathed to literally causing the apocalypse—more so than maybe anything else I’ve ever played.

Sometimes one person dies, sometimes no one dies, sometimes everyone dies

It starts in a similar way to the seminal “torture porn” horror Saw (2004). Jigsaw, the recurring serial killer mastermind of the Saw series, kidnaps and traps his victims within mortal puzzles. “I want to play a game,” says Jigsaw ominously. The game is, obviously, a deadly game—one of murder, deceit, and possibly triumph against the odds (even if that does require losing a limb or two). But that’s where the similarities to Saw come to rest. In Zero Time Dilemma’s aptly named Decision Game, you are given the choice to make nail-biting—yes, you guessed it—decisions. A lot of them, in fact. Sometimes one person dies, sometimes no one dies, sometimes everyone dies. Sometimes it asks you to remember a birthday that belongs to an alternate timeline, or you’re shit out of luck, and it’s back to the fragments menu. No matter what, it’s up to you to dictate how these choices are directed. And it’s up to the characters to blame the mysterious game master Zero—or each other—for being put through such a dastardly situation.

Hence, Zero Time Dilemma narrows its focus on human nature and morality in the face of survival. Its themes ring similar to another notable shock horror, Hostel (2005). In Hostel, an American tourist finds himself trapped in a pay-per-kill torture chamber for the wealthy. He eventually escapes, but not before exacting revenge on his captors. Hostel is an exercise on the human will to survive, and so is Zero Time Dilemma. But it manages to up the perils of these torture porn flicks by virtue of turning you, the viewer, into one of the participants.

That’s nothing new for videogames, and Zero Time Dilemma knows this, hence it attempts to compromise your perceived safety behind the screen by playing your own gains against the sacrifice of your fellow victims. If killing the other two teams by pressing a button ensures your freedom, would you press it? If taking a 50/50 chance of firing a gun (with the minor chance of a blank) into a close friend’s head to ensure the safety of another who’s about to be incinerated, would you still shoot? It’s not just the choices you make in accordance with the characters either—but how the ones surrounding you react. It turns into a game of predictions: how will my teammates react if I do this terrible thing? Even a seemingly well-meaning decision can go awry. Like trying to save yourself and the other team, but someone on your own team goes mad with anger, and bashes your head in a dozen times. Saving lives can turn into madness. Suicide. Murder. Time jumping. Anything that can go wrong as a result of your decisions, will go wrong.

Of course, the effectiveness of these cruel games Zero Time Dilemma plays against you relies a lot on you giving a shit about its characters. It’s in this that the game excels. If you’ve played the previous games in the series, then you’re instantly going to be drawn to the four familiar faces—Sigma, Phi, Akane, and Junpei. But there are also five fresh names vying for your heart. The nine of them are divided into three teams: C-Team (Carlos, Akane, Junpei), Q-Team (Q, Mira, Eric), and D-Team (Diana, Sigma, Phi). Of the new acquaintances to join the series, Carlos and Diana feel most at home. Diana’s sweet and caring—almost to a fault. Carlos is quick-witted and big brotherly to his teammates. The weak point, however, rests in two of Q-Team’s newcomers: the sociopathic Mira and puppy-dog-eyed Eric. Neither are particularly endearing, and the twists that befall the team don’t hit as hard as they should because of their yawn-worthy characterization. It’s a shame, especially in a series with so many multi-faceted, smartly written characters in the past.

Anything that can go wrong as a result of your decisions, will go wrong

This ‘who will survive’ mentality, pulling your affections apart like zombies at a feast of guts, is at times comparable to last year’s teen slasher thriller Until Dawn. But where Until Dawn’s choices lie simply in “who dies” and nuanced character interactions, Zero Time Dilemma wants you to think harder about your decisions. One life could be at stake, or six billion lives at stake. Betray, or don’t betray. It asks you again and again at what expense you think survival from the hellish, Nevada-bound bunker is worth. But while Zero Time Dilemma pressures you to make hard choices on the spot, it also encourages you to go back quickly—from the fragments menu—to see precisely what you narrowly avoided. Until Dawn doesn’t give you that luxury. You are trapped with any mistakes for the entirety of the game. But Until Dawn wants to be reminiscent of a movie, whereas Zero Time Dilemma wants to craft a narrative full of endless twists and turns that is wholly its own. The ease of going back to make different decisions makes sense for the game, because that string of story still exists. It isn’t overwritten by making a separate choice (as would be the case in Until Dawn).

Seemingly in an effort to impress upon you the gravity of each deadly scenario, Zero Time Dilemma swaps out its predecessors’ mostly stagnant, visual novel style of storytelling for full-length cinematics (sometimes lasting nearly a half-hour at a time with no player input). When something intense is happening, the camera zooms in close to zero in on the horror dawning on the characters’ faces, then it hangs at a low angle, staring up at our heroes. This is called a “Dutch angle,” shot on a tilted axis to evoke uneasiness and tension. Coupled with the foreboding soundtrack that kicks in during such scenes, it’s overall effective in inhibiting the player with the same amount of heightened fear as the characters. Zero Time Dilemma is, after all, a game of drama at the extremes—overexaggerated, shocking, inherently bloody—and Dutch angles hammer that point home. That is, until it happens over and over and over again, detracting from its initial power. Eventually, the overwrought cinematic style just grows tired, especially over the course of the game’s 20 hours. There’s a reason torture porn flicks don’t step over the two hour mark.

As the cinematic style grows old, as does Zero Time Dilemma’s puzzles. For every smart, intuitively designed puzzle, there are three arduous or just plain boring ones. Where the only drive I had to go on was to see more of the story unravel, when a puzzle grew tedious—and not in a rewarding “a-ha!” way when I figured it out—it dampened the game’s spirit, as well as my own as I clicked through the slog. The problem that Zero Time Dilemma perhaps suffers most is its own doing. In most instances, an escape-the-room puzzle would lead to another gruesome ultimatum. It’s these that keep you playing. But sometimes it wouldn’t. It’s a game that’s so high-strung, so superb at tension, that when it doesn’t provide it, the lull feels inexcusably slow. The most memorable and worthwhile puzzle is held in the incinerator room, wherein you try to help a teammate escape what they noted as potentially “the worst sunburn of [their] life.” For once, in the game’s many escape-the-room puzzles, there’s a sense of fear and urgency. In most of the other puzzles it’s disappointingly absent.

Luckily, Zero Time Dilemma’s story hardly ever wanes, except for a few outlier, minor subplots. Every fragment’s flow goes fulfilled. Despite having dozens of questions early on, by the end of the long twisted journey, I found everything to be resolved—or even left unresolved—in an extremely satisfying way. And that’s just how it is in Zero Escape. Not every history is perfect. Not everyone always survives. Because sometimes, as Zero would say, life is simply unfair, don’t you think?

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Zero Time Dilemma cuts like a knife appeared first on Kill Screen.

The new, silliest sport is Giraffe Volleyball

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

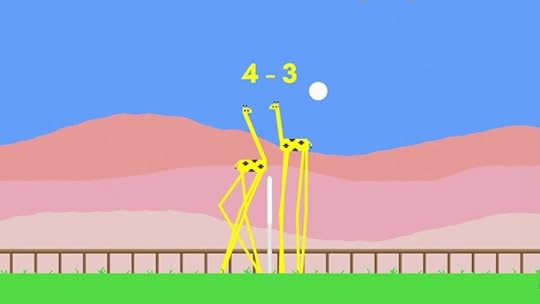

GIRAFFES VOLLEYBALL CHAMPIONSHIP 2016 (Windows, Mac)

BY SANDWICH PUISSANT

The problem with many sports is that they’re taken too seriously. Competition is king in the land of sports. It drives violent rivalries, absurdly detailed post-match breakdowns, discussions of people as integers as if they were made in a factory to dispense sporting performance. For a long time this stern-faced attitude dominated sports videogames, but more recently, the genre has found its silly side. Giraffes Volleyball Championship 2016 is the latest sports game to favor laughter over skill. You can see it immediately: you and your opponent are cast as lolloping giraffes, legs like spiders and necks that extend and contract at will. Normal volleyball rules apply as you bounce the ball with your heads and bodies, but it’s the visual comedy that keeps you playing, each of you giggling at the spaghetti-legged plight of your giraffes as they scuttle across the screen. It’s the rare kind of sports game that brings you closer to other people rather than pushes you apart.

Perfect for: Animal Olympians, siblings, competitive friends

Playtime: A few minutes a match

The post The new, silliest sport is Giraffe Volleyball appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 13, 2016

A videogame satire of police culture gives you something to think about

As far as violent crime rates go, South Korea is relatively tame when compared to most of its contemporaries. As detailed in a crime and safety report conducted by the U.S. Department of State Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC) last year, with the majority of crimes amounting to persistent low-level street crime such as pickpocketing and disorderly conduct. Reports and subsequent prosecution of sexual assault have risen, though this is in part owed to the Korean National Police’s concentrated campaign to root out and raise awareness of this problem since 2013. The country’s overall crime statistics have remained relatively static since 2010, so why the hell would someone set a game like Verdict Guilty, a ‘Cops and Robbers’ themed 2D fighter, in South Korea?

“It’s an idea I’ve had since I was 12 years old, although it was originally set in New York,” says Paul Davis of Retro Army Limited. “I chose South Korea as there’s no games set there, even though it has a very interesting history and a unique culture. Japan and South Korea have very low crime rates, [which is] partially due to their culture being based around serving the society, whereas in the West our cultures are based around the individual. I thought weaving some of the ‘service to society’ messages into Verdict Guilty would be of interest to Western customers, as in an exchange of ideas.”

Citing his intentions to create a game that serves as a necessary counter-move to what Davis describes as a growing anti-police sentiment in the West, the game attempts to inject a measure of nuance through portrayal of its characters—most noticeable in the duplicitous machinations of the seemingly-lawful politician Sabu and the repentant tender-hearted uncertainty of Yakuza enforcer Jae. Whether intentional or not, Verdict Guilty also shines an unsavory if momentary light on South Korea’s much-maligned reputation for overt racism and prejudicial treatment of foreigners in the case of Secret Agent Reese, who, while trying to ask a traffic cop named Minso for directions to a park, is outright profiled as a drug dealer. Aside from these exceptions, the game’s moral dichotomy between the apparent purveyors of social mores and the convicts and terrorists who seek to tear apart society remains firmly defined.

handcuff their opponent while ruthlessly beating them into submission

Verdict Guilty attempts to portray a police force that, though imperfect and at times incompetent, remains nonetheless resolute in its intention to uphold the law and strike at corruption wherever it may lie. Though, this message is uncomfortably muddled when one recognizes that the defining defensive move of the law enforcers in this game is to handcuff their opponent while ruthlessly beating them into submission. It’s no secret that the United States is currently caught in grips of a moral crisis when it comes to policing, and this comes to mind when considering Verdict Guilty.

Outrage among minorities directed at what is seen as the near-total lack of accountability and consequence for misconduct in the case of police-related homicides sits at the forefront of the US cultural consciousness right now. Ensuring this discourse is highly visible right now is the social advocacy movement Black Lives Matter—which is seemingly “pitted” against the institution of policing in America—and the sympathetic sentiment that law enforcers must be allowed to perform their duties and preserve their own lives by any means necessary. A videogame has scant chance of mending the generational rifts of resentment for the police caused by decades of prejudicial policies and institutional indifference, but it can bring to light the salient fallibility inherent of any one person when positioned in a role of public service defined through the execution of authority.

You can find out more about Verdict Guilty over on its website and purchase it over on Steam.

The post A videogame satire of police culture gives you something to think about appeared first on Kill Screen.

Let a low-rez world of flesh and metal overwhelm you

You should probably take a seat before you watch Mattis Dovier‘s Inside. Just get your head straight, y’know, couple of deep breaths, because Dovier’s animated short is a hugely discomfiting, bleak take on the relationship between people and technology. It spreads like a plague: our monotone narrator guides us through a future where, just beneath a pliable film of flesh, lies a gleaming mechanical skeleton.

He dreams of cables sluicing below his skin and bursting from his mouth; a burn on his hand dries and cracks wide to reveal cold metal within. His doctor diagnoses him with “severe hypochondria,” but he knows there’s something else going on. Or he thinks so, at least.

You ready?

Self-taught, Dovier works in an unmistakable style, one he described to me as “stripped of unnecessary details.” First Dovier draws each frame by hand in low resolution. Then he fills in shadows with pixel grids converted in Photoshop’s bitmap mode. The end result is somewhere between “numeric and classic aesthetics like engravings,” he said, as well as the screentone process characteristic of manga.

it bores into a dreamlike, unreal place

But black-and-white bitmap art also allows Dovier to move fast while still hand-drawing his work. It’s an interesting hack, one that relies on the very union of human and machine that Inside obsesses over. Dovier took Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986) and Videodrome (1983) as inspiration for the short, naturally, but also Charles Burns’s surrealist teenage body-horror comic series Black Hole (1995-2005). Somehow, Dovier hasn’t seen Shinya Tsukamoto’s seminal Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989), but people have been nagging him to take a look. There’s more than a bit of guro in Dovier’s ecstatic mutilations.

And, similarly: “During my research, I came across a Japanese dance called “Butô” that expresses a really deep inner pain.” The first shots of Inside directly pull from Butô: the narrator comes across a twisted, pained figure “screaming and struggling against thin air like one possessed.” Somewhere between performance art and dance, Butô is an amorphous discipline; philosophically transgressive and physically demanding.

Its earthy, visceral qualities are right in line with Dovier’s depiction of technology. His work isn’t didactic; it bores into a dreamlike, unreal place where we’re shown abstract and strange things. “We are in a society that wants to be more and more functional, like a tool, and tools are nothing except inanimate objects without someone behind them,” Dovier told me. “Does it make any sense if we lose the pleasure?”

The pleasure is there in Dovier’s work, in every bold composition and strobing bitmapped cloud of noise. Sink into this stuff, let it gnaw at the places where you quietly fear the inevitable and constant decay of your flesh and the unmapped, unimagined places we hurtle toward as a species.

Then, I dunno. You’ll probably need a laugh.

You can see more of Dovier’s work over on his website.

Interview lightly edited for clarity.

The post Let a low-rez world of flesh and metal overwhelm you appeared first on Kill Screen.

Competitive overwatch is about to get a lot more balanced

Yesterday, Blizzard published patch notes for a major Overwatch update they’ve been rolling out across their public test servers. The developer reveals a host of significant changes coming to the game’s competitive mode, not least of which involves limiting character selection to no more than one of each hero per team. If you’ve ever gone up against half a battalion of Bastions, a full crew of Junkrats, or an all-Torbjörn team on defense, you know how quickly things can go sour.

I once saw a Twitch broadcaster lead a team of six D.Vas to an almost effortless victory in a game of Control at Lijiang Tower. “We did it! We solved Overwatch,” the streamer joked. Because of the sheer number of hit points between them on the objective, the opposing team’s efforts at getting through proved utterly futile—even if one D.Va lost her mecha, the others could stagger their defense-matrix uses to protect her while her ultimate recharged, and so on. In a competitive environment, whether in matchmade online play or within the esports arena, this clearly poses a problem to the game’s central emphasis on diverse team composition.

a problem to the game’s emphasis on diverse team composition

One likely side effect of the new rule will be a more pronounced divide between the casual and competitive segments of the player population, as those who prefer to play as their favorite character all the time and those who prefer a higher win percentage more or less part ways. That’s not to say there won’t be those who enjoy dabbling in both experiences, but I certainly haven’t felt inclined to return to Quick Play since the launch of Competitive. Granted, that might change the moment a group of friends and I decide we want to try out a certain wild combination of heroes.

For good or ill, I foresee Competitive Play becoming home to the majority of regular Overwatch players (most folks I play multiplayer shooters with love to win), and that means issues related to character balance are crucial; nobody wants an unfair meta ruining the game’s dominant playlist.

“We’ve been discussing the idea of hero limits for almost as long as Overwatch has been in development,” says game director Jeff Kaplan. “In Competitive Play, we feel that hero stacking is becoming detrimental and leading to some not-so-great player experiences. For example, we’ve seen organized teams on Assault and Hybrid maps use hero stacking to overtake the first point before the defense has a chance to counter. We’ve also seen players use specific stacked compositions just to frustrate their opponents or cause indefinite delays in overtime.” Kaplan’s statement encapsulates my own experience with things like those six unstoppable D.Vas.

“While this kind of thing is certainly possible in any mode,” Kaplan adds, “the higher stakes of Competitive Play means these kinds of tactics were popping up more often than anyone would like.” A healthy, enjoyable multiplayer experience demands this kind of attention to player behavior—and that goes tenfold for the world of esports, where actual money is at stake.

a healthy multiplayer experience demands attention to player behavior

There’s a happy medium that exists when it comes to hotfixes in the FPS space: Some shooters, like Call of Duty: Black Ops III (2015) and Halo 5 (2015), seem to take their time and ensure that updates are going to address more problems than they create. Bungie’s Destiny (2014), by contrast, has a reputation for bending too easily to player demands, thereby making the Crucible meta feel like a constant and confusing uphill battle. Others still are so subtle with their patches as to seem static, which feels refreshing in 2016, even if it doesn’t necessarily facilitate an esports-ready competitive culture.

With major adjustments coming to characters like D.Va, Mercy, and Zenyatta, in addition to an entirely new support character named Ana, the new hero limit will ultimately be for the better. One aspect of the game that separates Overwatch devotees from casual players is the advantage that comes with mastering as many characters as possible. This new rule encourages that.

The post Competitive overwatch is about to get a lot more balanced appeared first on Kill Screen.

Europia, a videogame that aims to demystify the refugee experience

As the news coverage of Brexit rolls along the focus has inevitably, and somewhat depressingly, shifted to the fallout of the main parties involved. The Conservative party faced a swift and anti-climactic leadership battle following David Cameron’s resignation, and the Labour party is still in turmoil following an MP vote of no confidence against Jeremy Corbyn. Meanwhile, Nigel Farage was last seen sipping champagne with Rupert Murdoch following his own resignation as leader of the UK Independence Party.

While the press and political players scramble around these developments the immediate legacy, aside from political uncertainty and an economic plummet, is an atmosphere of palpable intolerance and racial tension. Lest we forget, Nigel Farage is a man who gifted the world with the ‘breaking point’ poster, a work that appeared to systematically demonize those seeking asylum from the Middle East. It’s precisely these views and rhetoric that Europia, a videogame designed by Maurice Andresen, attempts to challenge, giving us a little more insight into the refugee experience.

“I want people to question the way in which we handle these situations”

You play as an illegal immigrant. You’re confronted with a road, a single route into Europia, the fictional state found in the game. Other migrants ask you questions. “Have you seen my family?” asks one. “Have you seen my wife?” asks another. You pick up some money. It’s a five Euro coin. Everyone is walking in single file, not on the road, but to the side of it. And as you walk further down you begin to see the EU stars emblazoned on the border control. There’s a crowd milling about around it. You jump ahead of the queue and meet the border control officer. Like the building he is emblazoned with the EU stars, too. “Unfortunately we cannot process your application at this moment in time. Please understand we are very busy.” You look for another route in.

Andresen’s Europia is initially serene. You’re travelling at dawn and you hit a village first. Travel some more and you come across the city proper. The buildings tower above you, their perspective is distorted. “It’s meant to seem unmanageable in a way, and overwhelm you through the scale,” Andresen told me. “Things feel not quite right but you’re not in any danger—this sense of uncertainty but also you feel weirdly safe.” It’s indicative of Andresen’s attempts to demystify the refugee experience, to move past the binary representations we’re presented with in the media and by our politicians.

That demystification is also part of Andresen’s representation of the refugees themselves. Europia skewers the derogatory and inflammatory comments of anti-immigration discourse—the comparisons to rats, disease, and snakes—through its depiction of refugees as non-threatening, cloud-like entities. That approach was borne from Andersen’s own experiences: “I’m from a very small town in south Germany, and they’ve taken on so many refugees from Syria. Basically, we have these old French barracks and they put everyone in there—give them homes and stuff—it’s a welcoming place.”

But if the refugees themselves are non-threatening, almost cute, then the maze of tangled, broken, urban sprawl you find yourself in is anything but. It’s disorienting and frustrating, designed to reflect not only the physical disjuncture at entering a new city, but also the barriers inherent to the bureaucratic process of achieving asylum. Andresen reflected on his own attempts as a German national in trying to secure a UK passport: “It’s a very long-winded process—it’s almost as they want to put you off.”

Andresen also spoke of his hopes for the project. “I guess I want people to question the way in which we handle these situations and the way that the world shouldn’t be as restricted physically any more.” With the UK’s exit from the EU set to curb free movement of people, these physical restrictions look set to rise even further. Borders, at least for now, will become even more important. Europia, though, also questions the myth of Europe. It’s a timely reminder that those who do make it, far from being welcomed wholesale, still face significant barriers in the pursuit of a life free of persecution, danger, and oppression.

To play Europia contact Maurice Andresen. Details can be found over on his website.

The post Europia, a videogame that aims to demystify the refugee experience appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers