Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 90

July 15, 2016

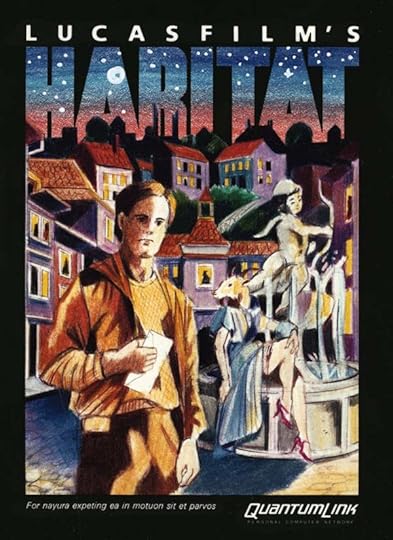

The steady process of restoring a long lost MMO

If you want to grow up to be a conservator—someone whose job it is to ensure a museum’s art is protected against the ravages of time—it involves a huge amount of schooling and preparation. Aside from art history, conservators learn chemistry to manage the precise makeup of clays or pigments used in paintings, they use x-rays and other imaging technologies to see works great artists painted over in order to save canvas. There are a relatively small number of academic programs that prepare an individual for that career, and a lot of the work has to do with passing traditions down. Without the proper training and expertise, you can end up with that one restoration of Ecce Homo that delights the internet and horrifies historians.

Their next step in the project is to get a server running

Perhaps unsurprisingly, preserving games also ends up requiring a lot of care and time. The team at the Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment has been working on bringing back LucasArts’ Habitat (1987)—one of the first and largest graphical massively-multiplayer online games—since 2013. They started out with the source code, which as Alex Handy points out, is only part of a game—where paint and its arrangement on a textile might be the whole of a painting, a game is defined by its interaction. Allowing people to comb through Habitat’s source code would be a kind of preservation, but more like an unraveled canvas and a small mound of yellow cadmium than Starry Night (1889). Enlisting the help of former LucasArts assembly coders Chip Morningstar and Randy Farmer, the MADE was able to make sense of the code and get it up on GitHub. Their next step in the project is to get a server running.

Re-creating Habitat entirely as it was would really require the same user-base and cultural context, and the internet has changed a lot since then. Farmer and Morningstar presented a paper, “The Lessons of Lucasfilms’ Habitat” during the “First International Conference on Cyberspace” in 1990. They were able to use the game to explore patterns in user interactions online—players were given every possible freedom to define the space, and quickly two dominant groups emerged: “anarchists and statists.”

Beyond that observation, the 26-year-old paper posits a few central understandings of how the internet worked—or should have worked—in 1986. First, that “A multi-user environment is central to the idea of cyberspace,” which, based on the direction games and social media have taken, rings true today. They also come to the conclusion that, “You can’t trust anyone,” which is as accurate as ever. So if these lessons from the early days of the internet have been learned through Habitat, what can we get out of it going forward? Maybe it’s more like visiting a historical landmark than a sculpture: the internet we have today exists in part because of what happened in Habitat.

You can find out more about MADE’s work on Habitat on its website.

The post The steady process of restoring a long lost MMO appeared first on Kill Screen.

EVO 2016 might be the most competitive smash tournament ever

The Trojan War was a great story, but I’ve always thought the parts with Achilles were lame. I never liked the way the nigh-invincible demigod was ankle-cheesed out of contention by a camper with a bow and arrow. Also, Hector was my favorite character, and we all know how that turned out. Even though Achilles ultimately gave him the business, Hector still defeated tens of thousands of Greek soldiers without the crutch of River Styx-granted immortality. In other words, it was Hector’s very fragility—the fact that he could be defeated at any time—that made him more interesting than Achilles.

In Super Smash Bros. Melee scenes of the past few years, we have suffered below the steel-toed-sandal-thing of one Achilles after another. The most recent despot, Adam “Armada” Lindgren, won the vast majority of 2015’s tournaments with steel-jawed Swedish precision. But now, midway through a tumultuous 2016, he is no longer unanimously the best player. Going into EVO 2016, the Melee scene does not have an Achilles. What it has instead is a heaping helping of short-hopping Hectors.

The Melee scene does not have an Achilles

Armada might still win, of course; he’s too mechanically skilled and mentally impregnable to finish outside the top five. But he lacks the momentum of Joseph “Mango” Marquez, an energetic American who enters EVO hot off a 1st place finish at WTFox 2, where he defeated Armada 3-0. Another challenger is the enigmatic Juan “Hungrybox” Debiedma, the only top-tier Jigglypuff player, who rivals Armada’s consistency and mental fortitude and has snagged multiple first-place finishes over Mango in 2016.

The competition doesn’t end there, of course. There’s a very real possibility that EVO 2016 might be the triumphant return of Jason “Mew2King” Zimmerman, a Melee legend who has shown significant improvement in 2016. Mew2King’s downfall is more often mental than mechanical; when he gets discouraged, or drops to the loser’s bracket, the quality of his play takes a vertiginous dip. In 2016 tournaments, Mew2King has been eliminated by such players as Wobbles, Nintendude, Swedish Delight, and Axe; all of those guys kick ass, but none of them are championship contenders. The most promising sign for Mew2King fans was the taciturn New Jersey native’s lower bracket match against Hungrybox at WTFox 2. Hungrybox, whose methodical playstyle is probably the closest out of all the top Melee competitors to full-on psychological warfare, tends to obliterate Mew2King, but at WTFox 2, the King won 3-0.

a close tournament is a fun tournament

Conventional wisdom states that a close tournament is a fun tournament. Even the most committed Armada fans probably got tired, at the peak of his reign, of watching him sashay to victory without emitting a single droplet of sweat. Whatever happens at EVO, this is certain: the person who wins is going to sweat like a fountain, because with the scene as close as it is right now, victory will only come to the person who plays the hardest.

The post appeared first on Kill Screen.

Clocker brings a storybook look to time-travelling puzzles

Clocker, recently Greenlit by the Steam community, is a quiet journey through time-shaping mechanics. In fact, it combines two elements of time manipulation—the ability to stop and to start the resource. But this is no SUPERHOT.

The story follows two characters, a watchmaker named John and his daughter, Alice. After gaining possession of a seemingly broken pocket watch, John finds he is able to freeze time and then selectively unfreeze participants at will for a few seconds at a time. Puzzles are situational, determined by the characters and the locations, and how their stilted movements can affect them.

Clocker looks to focus in on very specific moments

But you don’t always play as John. As Alice, you can unfreeze time by walking across scenes to see the effects of her father’s manipulations. It’s a bit of a sweeter, more melancholic version of the 2002 film Clockstoppers. Less rad, to be sure, but far more subtle and nuanced.

Since H.G. Wells Time Machine (1895) and onwards, to such modern works as Braid (2008), time travel has focused on consequences. Change in the past results in potentially skewed results in the future, and even a little meddling has a butterfly effect. With its precision time altering elements, Clocker looks to focus in on very specific moments—moving a girl out of the way of a falling piano, pushing a car into place so that you can use it to climb to higher places—rather than larger set pieces.

But the time stopping and starting is only part of the appeal here. Clocker also boasts a certain storybook quality to its tale with its softly saturated images and gentle music. Ultimately, it is the story of a little girl wanting to be reunited with her time-traveling father. It looks like a sweet game overall, but one that’s tinged frosty by a fog-paned glass and razor-sharpened to that jolt of childhood panic when you turn around in a store to find your parent suddenly gone.

You can find out more about Clocker through its Steam Greenlight page.

The post Clocker brings a storybook look to time-travelling puzzles appeared first on Kill Screen.

The perverse beauty of streaming the democratic national convention on twitch

Sometime around the moment Barack Obama won Iowa, a little cartoon light bulb lit up above the heads of some 10,000 or so campaign managers and associated staff nationwide. The light bulb was duly followed by a thought bubble containing the words “young people also vote, sometimes.” Since then, every political campaign, Super PAC, and fair & balanced cable news network has been racking its lumbering, collective brain in search of ways to mobilize young voters in support of one candidate or another. So far the only surefire technique is “have your candidate be Barack Obama or Bernie Sanders,” but that hasn’t stopped the graying establishment from experimenting, which is how we wind up with headlines like “Democratic National Convention Streaming Options Include Twitch.tv.”

can we take a moment to appreciate how amazing this is?

God, this is amazing. Can we just take a moment to appreciate how amazing this is? We are talking about a really historic event here, a Democratic convention that might be the last one ever before a certain bulbous businessman turns the country into the world’s most gaudy autocracy, and will definitely be the first event of its kind to feature a coordinated “fart-in,” and the whole thing is going to be streamed on Twitch.tv, a platform whose previous most-culturally-impactful event was Twitch Plays Pokemon, a powerful argument against blindly obeying the will of the masses if I’ve ever seen one.

The Republican National Convention has yet to confirm that Twitch will be among its own streaming platforms [Update: Twitch announced that they will also stream the Republican National Convention], but considering the GOP’s abysmal performance among young adults in recent years, it is unsurprising that they would once again lag behind their agile—dareisay spry—Democratic counterparts in this, the bleeding cutting spear-point razor-edge of gutsy campaign gambits.

imagine the memes.

Of course, what’s most exciting about this development is not the content itself, which will probably be excruciatingly boring (ResidentSleeper), but the fast-scrolling chat that will accompany it. Imagine the memes! How many times will we see “Delete Your Account” posted? How many crude-yet-hilarious Monica Lewinsky copypastas will be unleashed when Bill steps on stage? Will there be even a single moment during Bernie Sanders’s raspy re-endorsement speech when the chat is not simply overflowing with “Kappa” emotes?

And afterwards, long after the stream has gone offline, will there be any artifact from this era that will engender more interest from archaeologists of the year 3016 than the permanently-saved Twitch chat log that will accompany the recording of this convention?

Kappa.

The post The perverse beauty of streaming the democratic national convention on twitch appeared first on Kill Screen.

A videogame for #blacklivesmatter

Yvvy, the designer of the upcoming Easy Level Life, knows you can’t “win” against police brutality. “The closest thing to a win condition where police brutality is concerned, is simply not being the wrong skin color,” they told me. “The game is the same way.”

Easy Level Life popped up on Twitter on Monday, the 11th, just after a week that saw two black men killed by police a day apart. Yvvy said that every time this happens, “I see the same questions: Why did they do wrong that the cops shot them? Were they listening to the cop? Why were they afraid if they didn’t do anything wrong? If the cop was afraid, didn’t they do something wrong?”

[image error]

A software engineer by trade, yvvy took a few days off reSyNCh, their larger project, to turn out Easy Level Life. It’s an issue that’s not suited to traditional games, which in basic terms demand understanding of, if not victory over, their systems. Tensions between police and people of color are systemic, entrenched, and impossible to “beat.” But yvvy’s not deterred.

a list of options to get yourself out of the situation alive

The game explicitly seeks to tackle those persistent questions about personal responsibility in the face of law enforcement. Yvvy says they’re “often asked by people who have never had a reason to fear the police before.” Working with an artist, @nebelstern, yvvy wants to provide some perspective. An early build of the game lets you play as a middle schooler who comes across a man being beaten by three cops with nightsticks. You’re faced with a list of options to get yourself out of the situation alive, but no matter how innocuous your choice it ends in a sharp, abrupt gunshot. Once you’re dead, the newspapers do their work to make you seem like a threat: whether opening a candy bar or standing stock-still, there’s no way out.

“It’s close to my heart as someone who has to face this violence,” yvvy said.

You can follow yvvy and their bigger game project, reSyNCh on Twitter.

The post A videogame for #blacklivesmatter appeared first on Kill Screen.

How to make a good Republican convention drinking game

This American presidential election is deadly serious. Even if one party’s candidate appears to have emerged from a Ronco countertop rotisserie, and his ideas might as well have come from there too, the whole thing is too ugly and scary to really be a joke. The Republican National Convention, however, is a whole other story. When the first item listed on a host committee’s “find a supplier” page is called “The Cool Bus,” at least a few jokes are in order.

Before the jokes: Yes, this whole thing is going to be a disaster and hopefully nobody gets hurts in the process. There, we have the bigotry of low expectations to go with the plain old bigotry on stage.

On the subject of surviving: You’ll probably need a drinking game. Seeing as this is a videogame publication, this is the rare situation in which we can offer you some life advice.

Reward anticipation

Drinking games are about drinking, sure, but they are also games. That last little bit tends to get forgotten. Games don’t simply give you what you want—release from the frustration of politics, in this case—they make you wait enough that you’ll enjoy your reward more when it comes along. In other words, if a drinking game is the equivalent of hooking up an IV tube filled with beer, something has gone wrong. That’s just called drinking. In other words, you’re looking for prompts that are likely enough to come (in past Republican conventions, “job creators” fit this bill) but that are sufficiently spaced out to build anticipation (ie. Don’t choose the article “the” as the prompt for taking a shot). This doesn’t mean that you have to spend your entire night in anticipation, but much as Pokémon Go would be boring if you never had to leave your house to play, so to is a drinking game in which there is no anticipation.

Games are about choices

This shouldn’t be news. Sid Meier’s defined a game as “a series of interesting choices” decades ago, and that remains true to this day. Drinking games, however, struggle with the choice mechanic, because you are fundamentally dependent on the actions of another person. In traditional drinking games, your chances of imbibing would depend on—to pick an example at random—a Dorito-dust-crusted husk of a presidential candidate blurting out a racist dog-whistle. No choice involved. But choices make a game more interesting. Having to choose between quality and quantity—shots and pints, for instance—whenever a prompt comes up creates a more interesting dynamic.

Escalating level design

Level design gives a game its structure. You don’t want to front-load all the challenges. This is one of the few areas where the Republican National Convention has good game design: four (four!) Trump children will speak before the paterfamilias. Your drinking game should follow this structure: start easy before working up to the heavy stuff.

Embrace the Futility

No matter how good your drinking game is, this will be awful. Embrace it. Have a drink.

The post How to make a good Republican convention drinking game appeared first on Kill Screen.

Dots & Co brings even more friends to the dot-popping series

During the spring of 2014, a cloud-bearded pappy and his blushing daughter went on a quest to connect dots in dangerous places. A puzzle game with pleasant, sojourn aesthetics, TwoDots took players to volcanic peaks and icy depths, battling lava and thawing matching dabs of color. Some good stuff to keep idle thumbs busy, but at its lowest points felt like it had succumb to the atypical mobile dilemmas—a sinking feeling that the game was more than hard but rigged. Levels only guaranteed to be beaten with payable power-ups, and with attempts tied to a clock, later levels shifted from a game about wit to a game about patience.

With its new sequel, Dots & Co—due to come out for smartphones on July 21st—the dots have a chance to go on another mobile adventure. This time they are bringing along friends. Powerful friends.

Dots & Co can be your travel buddy

Beginning in a rec room, mounted with memorabilia from the last great voyage, the adventure around the pale blue dot we call Earth starts from familiar places. Connect dots of the same color to pop them. Create a matching loop of dots to wipe the entire color from the screen. Obstacles and stubborn layouts will test you, but the new cohorts are here to help.

Many of the stages are paired with new partners, each with a unique dot-related superpower. A penguin that can wipe off a color of its own accord. A polar local who can throw down paint grenades that will splatter fields of color. A bison that spits. Their abilities are activated with triangles scattered among the dots, and as the game goes on these skills elevate from boosters to necessities.

Power-ups are no stranger to Dots. In TwoDots you could previously throw dynamite and raindrops at each level. In Dots & Co they’re added elements to spruce up the game and, when you’re linking certain chains of colors and triangles together, enablers to godly moments.

It isn’t entirely free from the feeling that some levels come down to more luck than skill (though, the version I played is still being tweaked), and some of the new effects, such as a flower that will grow into neighboring dots and blow them up, makes Dots feel more like Bejeweled than ever. But this is the summertime, and many of us will be in cars, trains, and parks with a moment to kill and worse ways to do it. If you feel like taking a meta-vacation, a game about a vacation during your vacation, then sure, Dots & Co can be your travel buddy. Having a friend that’s luckier than they are bright can be pretty handy on the road.

Dots & Co is due to arrive for smartphones on July 21st.

The post Dots & Co brings even more friends to the dot-popping series appeared first on Kill Screen.

Videogames and the end of sleep

In 2005, following the public outrage over the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, the research group Gallup organized a survey to gauge Americans’ attitudes towards the “enhanced interrogation techniques” employed by intelligence services in the War on Terror. When presented with descriptions of such methods, including waterboarding, mock executions, religious violation, and the threat of attack dogs, the overwhelming majority of those polled rejected them as morally impermissible torture. But a single practice, sleep deprivation, was deemed acceptable by half of all respondents on the basis that it doesn’t constitute torture, per se, but “psychological persuasion.”

Bullshit. Though accounts of sleep deprivation for purposes of coercion can be found as far back as Antiquity, its systematic use coincides with the invention of high-intensity electric lights and sustained sound amplification in the mid-20th century. Interrogators at Guantanamo Bay are known to have subjected prisoners to Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” at ear-splitting volumes (James Hetfield, the band’s lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist, initially boasted that he was proud of this particular application of their music). Sleep deprivation, in other words, is a distinctly modern practice. Above all, it is designed to obliterate a prisoner’s sense of self and generate a state of utter helplessness and absolute pliability—the ideal subject(tivity) for interrogation. Writing in his recent book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (2013), Jonathan Crary censures the practice as not simply a biological affront, but a psychological one as well: “The denial of sleep,” he concludes, “is the violent dispossession of the self by external force, the calculated shattering of an individual.”

Sleep deprivation is a distinctly modern practice

Crary’s book is deliberately provocative—“a polemic as finely concentrated as a line of pure cocaine,” zings one back-cover review—and so should probably read more as a manifesto than a work of serious scholarship. But his central claim, that the modern world and its economies have conspired to annihilate the need and desire for sleep, helps illuminate at least some of America’s apparent (and shameful) reticence to classify sleep deprivation as torture. If the denial of sleep somehow seems more palatable than mock executions or waterboarding, perhaps it’s because we’re tempted to see ourselves as sleep deprived—which, in fact, is true, if only in a relative sense. In 2016, the average citizen of a post-industrial society sleeps for 6.5 hours a night, down from about eight hours a generation ago, and 10 in 1900. The spectacle of modern life, Guy Debord once quipped, “expresses nothing more than society’s wish for sleep.” And maybe he’s not wrong—at no point in history have so many humans slept so little.

Still, that we’d even dare to equate our daily grogginess with the indignities of systematic sleep deprivation doesn’t speak well of our capacity for empathy, or, for that matter, our sense of morality. But it does expose the curious, contradictory relationship we now have with sleep in the age of “always-on” global capitalism. The historiography of sleep is thread-bare, but what books do exist are largely premised on a pair of axioms. The first, however predictably, is that sleep is both a social practice and a cultural discourse contingent upon its historical circumstance. Just one example: as political modernity began to take shape and private property became an increasingly important component of nascent industrial economies, it became a sign of civility to sleep out of sight of others—that is, sequestered in your private home. In bourgeois life in the West, as argues the historian Norbert Elias in The Civilizing Process, sleep-practices became one more way in which the monied could signify their class belonging.

Bedroom in a Country Dacha, artist unknown, 1839

Bedroom in a Country Dacha, artist unknown, 1839

The second truism of critical sleep studies is a general sense that sleep is, and has been for some time, under assault by the forces of modernity, mustered above all by the relentless churning of industrial and postindustrial capitalism. In Das Kapital, Karl Marx conceded that even the most ruthless of managers would acknowledge, however begrudgingly, their laborers’ need for sleep as a “natural” part of life. We are, after all, more-or-less forced to construct our society and its temporalities around those precious hours in which we must sever ourselves from the world of conscious experience.

Or are we?

Crary, at least, doesn’t think so. He claims that our 24/7 economy no longer recognizes any barriers to the cycle of production and consumption that animates capitalism. “The planet,” he writes, “is imagined as a non-stop work site or an always-open shopping mall of infinite choices, tasks, selections, and digressions.” The result is the besieging of sleep in order to obliterate any meaningful distinction between productive and non-productive time. Ask yourself: can you truthfully say that you haven’t semi-consciously whisked off a work-related email in the smallest hours of the night? Or purchased some wholly unnecessary trinket during a delirious somnolent intermission? I know I have. In fact, these two conditions often enable each other. Once, while living on the east coast and working overnight to cover a professional gaming tournament in Shanghai, I impulsively ordered an oscillating fan to counteract the heat from my desktop computer, a purchase I did not remember making when the device appeared at my door two days later.

Digital media, in Crary’s view, is now among the most powerful weapons available to advanced capitalism in its persecution of slumber. And he’s not alone in suggesting as much: one recent study in Applied Ergonomics claims that exposure to computer screens in the evening could be correlated with less-fulfilling sleep in three quarters of test subjects (exposure to blue electric light is thought to inhibit the pineal gland’s secretion of melatonin; such is the logic behind apps like Flux and Night Shift, which shift the color of laptop and iPhone screens, respectively, from blue to yellow after sunset). Unsurprisingly, videogames are high on Crary’s list of villains. And why not? Few who enjoy videogames with any regularity lack a vignette about an obsessive late-night play session undertaken against their better judgement and to the detriment of the next day’s tasks. Endorsing Crary’s point (if only anecdotally), I live under a self-imposed ban on playing videogames after 11 PM, which, without exception leads, at best, to fitful sleep, and, at worst, lurid nightmares.

sleep is, and has been for some time, under assault by the forces of modernity

But the problem, if you deign to call it that, isn’t just how we sometimes play videogames. It’s also the affordances of the medium itself. Like most forms of digital media, and unlike radio and television, videogames do not depend—or, for that matter, prey—upon any schedule but that of the user. In fact, initially at least, neither television nor radio stations would broadcast content after midnight out of respect for the sleep of both listeners and their own staff. Videogames, though, have no loyalty to the circadian rhythm that evolution has cultivated over billions of sunsets and sunrises. 1 AM is exactly as good a time as 6PM to boot up a videogame; there is no moment in which you can’t be playing videogames. The same might be said of books, of course, but, here, another telling distinction emerges. Whereas books require an external light source to be read, videogames, like all self-illuminating screen-based media, pollute the darkness with their own harsh, electric light. From this perspective, videogames enact a particular kind of violence on the night that is, in many ways, unprecedented in the history of media.

Mobile games, first on handhelds (Game Boy, etc.) and now on smartphones and tablets, are especially contemptful of our sleep. For those of us who grew up at the turn of the millennium, I’d wager that it’s a close to universal experience to have furtively played a Nintendo Game Boy well after the parentally-mandated “lights out,” stuffing the device beneath the sheets whenever a suspicious elder might wander by. Always-on smartphones have only emboldened the encroachment of videogames into our beds. Last summer, I reviewed Bethesda Softworks’ pithy iOS game Fallout Shelter, in which you manage in real time an underground vault after an unseen nuclear war. One night, Fallout Shelter executed my best scavenger after I had the temerity to sleep through a 4AM push notification warning me of her impending death.

What’s even stranger, though, are the various ways in which videogames themselves draw upon sleep as a mechanical rule. Why should those digital marionettes whose strings we yank to transmute time into fun need to sleep at all? It’s hard to imagine irrepressible action heroes like Uncharted’s Nathan Drake or Tomb Raider’s Lara Croft ever having any purpose, let alone need, for sleep. Our nightly descent into obliviousness, languor, and non-productivity seems so at odds with the fantasies of power that so many videogames are designed to enable. Why bother with the demands of our mortal coil in a medium that can liberate us from the inconveniences of being in a body?

Elder Titan’s Echo Stomp ability in Dota 2

Elder Titan’s Echo Stomp ability in Dota 2

When sleep is integrated into videogames, it usually functions in one of three ways: as an offensive weapon, as a self-enhancing buff, or as a means of saving the game. Consider: Valve Software’s Dota 2 (2014) contains a pair of quintessential examples of sleep as a targeted disability. Two characters, Bane and Elder Titan, each possess abilities (Nightmare and Echo Stomp, respectively) that allow them to put an opponent to sleep, a condition the game’s unofficial Wiki describes as a “status effect that completely disables those affected for the entire duration.” In practice, both skills are often used to immobilize a target while Bane or Elder Titan’s teammates coordinate a more lethal strike. What’s “bad” about sleep, as it’s constructed in the rules of Dota 2, is not simply that it makes your character unproductive, but also hugely vulnerable. And this view has a history: in his Leviathan (1651), for example, Thomas Hobbes claims that one of the most basic functions of government is to protect the sleeper from threats both real and perceived. Dota 2 is not, of course, making a statement about the state’s mediation of security and sleep, but it nevertheless is respondent to a tradition of thought that imagines sleep as a perilous state of unproductivity.

The Pokémon series contains a more vivid example of this view: a disobedient, undisciplined Pokémon will occasionally nap instead of carrying out the player’s orders—sleeping on the job, as it were. This characterization of sleep—as distracting, ineffectual, and undesirable—neatly fits into the general mold of Crary’s point about the hostility of contemporary capitalism and its media to sleep. The Pokémon series’ solutions are also familiar; players can turn to over-the-counter pharmaceuticals to awaken their dozing Poké-laborers. Sleep, in this respect, is cast as a deficiency of industry, in need of corrective management to re-enable maximum productivity.

Videogames have no loyalty to the circadian rhythm

In games dedicated to a self-contained activity—fighting, racing, etc.—in other words, sleep is almost universally seen as bad, as it prohibits the performance of that activity. In open-world games, however, game designers draw upon sleep for number of reasons. Generally, the purpose of these games—The Elder Scrolls, Fallout, Grand Theft Auto, etc.—is not so much to convey a specific story or activity to the player, but to set up a horizon of possibility in which a huge range of stories may occur. In most cases, this involves simulating a society, and, as Crary et al. have argued, sleep is part of the social and cultural organization of a society. Sleep, in this sense, is not just a matter of constructing a familiar, or at least believable, society to inhabit, but also a way of saying something about that society and its politics.

In Bethesda Softworks’ Elder Scrolls, for example, the Khajiit, a bipedal cat people who constitute much of the game-world’s underclass, are more active at night and have superhuman vision in low light. The lore of the series strongly implies that some of the “racism”-as-speciesism the Khajiit face derives from the fact that the normative human populace is mistrustful of the Khajiits’ nocturnality. Simply put, the way sleep practices are or aren’t socially validated are just one way in which the Elder Scrolls plays out the racial politics of its world. Because humans are the most empowered “race” in Tamriel, their culture is dominant and privileges their diurnal, anthro-centric circadian rhythm as the cultural norm. The biopolitics of sleep, in other words, are no less relevant in virtual worlds, and they can help us understand how sleep means so much more than “rest” in our own.

Khajiit warrior from The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim

Khajiit warrior from The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim

Often, game designers also use sleep as a way of forcing the player to integrate more seamlessly with their built worlds. In March of this year, Bethesda released an update for the post-nuclear role-playing game, Fallout 4 (2015), enabling an overhaul that the developers labeled “survival mode.” Aimed at giving players a more “realistic” challenge, the mode increases damage taken, removes the ability to fast-travel, and adds diseases, among many other changes. The mode also requires that you sleep regularly. Failure to do so results first in a fatigue penalty, lowered resistance to disease, and eventually deals damage to your character. Describing the changes in a lengthy blogpost about survival mode, Bethesda wrote that one of the mod’s major principles of design was “resource management.” Alongside health, stamina, food, and water, players must contend with the acquisition and judicious dispensation of the “energy” sleep produces, imagined here as part of the amalgamation of raw materials that gives rise to conscious experience.

Fallout 4 was not, however, the first game to imagine sleep as a resource to be produced and consumed like any other. The most famous to do so is Maxis’ iconic series The Sims, in which players must manage their Sims’ energy alongside their need for social interaction, food, hygiene, etc. When their energy bar runs low, Sims are more likely to injure themselves and will perform poorly in school and at work. Instinctively, this makes sense— insofar as The Sims is a simulacrum of contemporary life, why wouldn’t these digital beings need to rest for a third of their simulated lives? Still, as Miguel Sicart has famously argued, The Sims should be understood not simply as a social sandbox, but an extension of the ideology of modern capitalist societies (the fastest way to make your Sims happier, of course, is to acquire more shit). The Sims reduces—or at least reconfigures—one of humanity’s most universal and indescribable experiences into a commodity, just one more transaction in an endless blur of buying and selling.

The biopolitics of sleep are no less relevant in virtual worlds

Even if they don’t explicitly cast sleep as a resource to be expended, many other games use sleep (or “good” sleep at least) to offer tangible, in-game benefits to the player. From its inception, World of Warcraft (2004) has encouraged players to log out while in one of the world’s many inns by offering a “well-rested” bonus that temporary increases the player’s experience gain upon their next login. Beyond a vague sense of “realism,” the mechanic serves the more practical function of letting less-frequent players catch up with their more dedicated friends: the longer the player spends in the inn, the longer the bonus lasts. Later, the game’s fifth expansion, Warlords of Draenor (2014), introduced the ability for players to pitch a tent while exploring the game’s massive world. Sleeping in the tent for 10 seconds or more granted the player a 10 percent bonus to all their stats for one hour. To play to the best of your character’s ability, in other words, requires making time for a quick nap under the skies of Azeroth.

Given all this sleep positivity, it might be said that The Sims, World of Warcraft, and any other games (and there are many) that cast sleep as a tangibly beneficial activity resist Crary’s vision of our hypnophobic dystopia. And, to an extent, this is true: these systems of play privilege the act of sleeping as something that’s not simply necessary, but valuable. At the same time, there’s something more sinister at work here. In 24/7, Crary writes that despite decades of financially-motivated research into sleep, it “frustrates and confounds any strategies to exploit or reshape it. The stunning, inconceivable reality is that nothing of value can be extracted from it.” Yet The Sims suggests in rather unambiguous terms that something valuable can be wrung from sleep in the form of “energy,” one more form of human currency.

Character sleeping in The Sims 3

Character sleeping in The Sims 3

And, to be sure, there is something inescapably transactional about sleep. We trade those hours in which we shut ourselves away for the mental clarity we need to pursue our interests, productive or not, when we are awake. But The Sims goes one step further by making sleep and its boons a quantified entity. In fact, whatever benefits sleep may provide are benefits only insofar as they are quantifiable, capable of being measured and integrated into the game’s particular model of contemporary life. This practice belongs in the long history of scientific management and biometrics, which are both premised upon the sublimation of corporeal and subjective experience into data that can be analyzed and acted upon to “optimize” the individual. So far, sleep has largely resisted the best efforts of researchers to frame it in any liquidable way; when we say we’re “low on energy,” we remain firmly in the realm of metaphor. But games like The Sims embody a vision of a Taylorist dystopia in which this isn’t so, a cybernetic society inhabited by beings of pure information operating in known and knowable algorithms.

Maxis did not, of course, intend for The Sims to offer any serious commentary on sleep and its discontents. But that does not mean that its representation of sleep is devoid of politics, for this representation is based on certain assumptions about what sleep is, why we need it, and how we do it. It’s telling, I think, that The Sims makes no distinction between different kinds of sleep: mechanically speaking, sleep during the day is treated as identical to sleep after dark. And the only difference between a harsh mattress and a plush bed—besides, of course, the price—is the rate at which it restores energy, meaning wealthier Sims spend fewer hours sleeping (and, by extension, more hours being productive). These rules might seem arbitrary, but they are, at heart, socially contingent, and therefore are always already political. They normalize the notion that sleep is simply sleep, a claim that would puzzle historians of sleep, for whom sleep is never simply sleep. It’s a revealing social practice that’s deeply intertwined with class, technology, and labor.

sleep is a social practice that’s deeply intertwined with class, technology, and labor

The interplay between biology and culture is endlessly complex, but the flattening of sleep into a single, transparent, numerical experience is especially fraught in the sleepless modernity we now inhabit (and inhabits us). Just one example: The Sims’ suggestion that there’s no difference between sleeping at night or sleeping at day obscures the dark side (so to speak) of “flexploitative” labor practices. In the United States, 20 percent of workers—a disproportionate number of whom are black and latino—now work non-circadian hours, even though extended periods of non-circadian sleep have been correlated with serious, adverse health effects. And while we’re kidding ourselves indeed if we’re expecting The Sims to use a historically nuanced, intersectional model of sleep, it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t think about the model it does have. For whatever else it may be, The Sims, at heart, is a game about how we see ourselves, for better…

…or worse. In 2004, a LiveJournal blogger named EverGrey set up an sadistic experiment in The Sims. As she explains, “I guess people actually play this game to make their little Sims happy. I’ll admit that I did that for a while, but, to be honest, it just got boring. So, of course, I reverted to my typical gaming pattern of torturing innocents to death.” The Sims does not give the player any ways to directly harm their Sims, so EverGrey embarked upon a program of malicious neglect, imprisoning two Sims in a barren 4×4 room that denies them access to food, light, a shower, and, most of all, the ability to sleep. As the unfortunate Sims enter their second day without rest, they frantically begin to cry out for a shower, a meal, and a bed. Eventually, once the pair of Sims are exhausted, starving, soaked in their own urine, and quite literally unable to be any more miserable (the numbers confirm it), EverGrey burns the box to the ground.

EverGrey’s Death Box in The Sims

EverGrey’s Death Box in The Sims

Extreme? Sure. But The Sims doesn’t incentivize the player to deprive their Sims of sleep, nor does it devote significant resources to exploring what happens to sleep-deprived Sims. Though the failure to sleep can be fatal in later versions of The Sims, in Maxis’ original The Sims (2000), the only tangible effect of sleep deprivation is that Sims abandon their higher-order goals in favor of their pressing bodily needs. Writing about EverGrey’s performative torture, the scholar Mark Sample suggests that she has superseded the relationship between law and violence, producing instead what the philosopher Giorgio Agamben called a “state of exception,” a model of internment meant to reduce human beings to a life of mere survival, limiting their subjective horizon to immediate biological concerns. It’s not so much that the “state of exception”—of which sleep deprivation is just one technique for domination—strips its victims of their lives, but that it strips them of their selves.

Agamben had concentration camps in mind when he conceived of the “state of exception,” but the term has more recently been used to describe the purgatory of CIA black sites prisons, where “illegal enemy combatants” are detained without trial, denied information about whatever awaits them, and, frequently, denied the right to sleep—a practice nevertheless deemed acceptable by half of all Americans. But to deny sleep—as would interrogators, late capitalism, and everything else that is an affront to what is good and decent in humanity—is much more than physical violence. It is not simply inhumane, but ahumane—at its rotten heart, it constitutes a refusal to believe in the right of another human to possess a self. And though its politics of sleep elsewhere may be muddled, perhaps The Sims can remind what has always been true: that sleep deprivation is not “psychological persuasion.” It is torture.

But if sleep deprivation is torture because it shatters the self, than we must also accept that sleep is what allows the self to cohere. Sleep, in this sense, matters for so much more than the flushing of intracranial debris, promotion of cortical ontogenesis, and whatever other operations neuroscience will, in time, reveal to us. Sleep, simply put, is the precondition of making, and remaking the self. Every day, we touch and are touched by the world-as-other in more ways than we can hope to comprehend. Sleep, in its own way, manages these memories. Some are shed like dead skin; others are fastened to our lives, like pieces in a jigsaw with two sides. If only until we wake, sleep resolves the chasm between subject and object, self and other, bound up in an endless process of mutual self-recognition. How strange that we both are who we have been and all the things we may become in a moment that we are incapable of knowing, veiled behind a span of experience as unavailable to us as being born or dying.

Sleep is the precondition of making, and remaking the self

And so, if life shares anything with a game, then sleep is how we save. And, in fact, sleep often functions in exactly that way. In many open-world games, from Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto IV (2008) to Chucklefish Games’ Stardew Valley, the only way to save your progress is to find a bed and sleep. On the one hand, the inclusion of sleep lends these virtual societies a certain sense of social realism. On the other, sleeping-to-save affords these games a particular cyclical, almost circadian, rhythm. Anyone who has played Grand Theft Auto IV knows this pattern of play: rampage, explore, mission, explore, rampage, sleep. Repeat. Sleep, in this sense, is redemptive, but not in a way that can be exchanged for virtual goods. This closure is not quantifiable, but psychological. And it resists, in its way, the commodification of sleep under the conditions of late capitalism: we sleep to stay, and save, ourselves. In The Tempest, Prospero famously surmises that “we are such stuff as dreams are made on; and our little life is rounded with a sleep.” Every day, he means, we wake into a truer dream.

///

And how…

In Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (2006), like every other game in the series, you enter the nation of Cyrodiil as a prisoner with no past, no memories, and, consequently, no self. When you are released from bondage and step into a numinous morning, the game gives you a self—your self—to build in any way you desire. You begin to explore the world, gingerly at first, never losing sight of the glimmering Imperial City around which the country is oriented. In time, your adventures take you from rebarbative mountains to the chthonic plains of hell; as you wander, you receive occasional notifications about your character’s development: your athletics skill has increased, your alchemy skill has increased, etc. Even the simplest activities—running, conversing, gathering seeds of flax—feed into these titivations; often, you’ll become more proficient at something without ever intending to.

Eventually, after you’ve been notified for the 10th time about an increase in skill, you receive a new message: “Rest to level up.” Perhaps you ignore it, perhaps you don’t. Either way, you quickly realize what Oblivion is telling you: keep learning all you want, but you’ll have to sleep to grow. And so, sooner or later, you pull out your bed roll and spread it upon the moon-soaked tablelands of Cyrodiil. There, you turn your eyes up to a night sky hung low, buckled in upon itself as if it cannot support the weight of its stars, and you sleep. You sleep. You sleep.

And when you wake, you are more yourself than ever before.

Header image: “A Different Kind of Dreamer” by Jim & Lynn Lemyre

The post Videogames and the end of sleep appeared first on Kill Screen.

July 14, 2016

The days of betting counterstrike skins are numbered

After recent disclosures about potential Federal Trade Commission (FTC) violations within the Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO) community, Valve has come out with a statement about the matter, dismissing their involvement in the gambling sites as well as putting those sites on notice that their usage of the Steam API is against terms and conditions.

Since then, a number of gambling sites started leveraging the Steam trading system, and there’s been some false assumptions about our involvement with these sites. We’d liek to clarify that we have no business relationship wtih any of these sites. We have never recieved any revenue from them.

In the Counter-Strike community in general there exists an underbelly of these sites that toe the fine line of gambling—promoting themselves as “sweepstakes” where users can bet their skins like poker chips in coin tosses or on actual matches.

the fine line of gambling.

These sites have been operating for years, and exist for other games aside from CS:GO, including Valve’s own DotA 2. In recent weeks they’ve come under notice due to a class-action lawsuit from a Connecticut resident alleging that the gamemaker and platform holder is knowingly complicit in these gambling sites and a YouTube scandal.

Following an investigation from YouTuber HonorTheCall, several big YouTube CS:GO personalities (notably Tmartn & ProSyndicate) were called out for both owning and promoting the gaming site CSGO Lotto, pumping out videos with spammy titles (WINNING BIG $$$$!!! (CS:GO Betting)) to shill for their own company without disclosing their involvement. This latest spurt in bad publicity has brought attention to a growing, unregulated economy within the CS:GO skins marketplace, which some users viewed as existing with the presumed support of Valve since they could hook up their Steam accounts directly to the sites.

a growing, unregulated economy within CS:GO.

While Valve continues to protest both their presumed involvement with these sites and the potential profit that they have made over the years, Bloomberg estimates that this is a $2.3 billion dollar industry, with Valve taking in about 10% of every skin sold.

The post The days of betting counterstrike skins are numbered appeared first on Kill Screen.

Monument Valley designer’s next project starts by putting people first

Ken Wong, lead designer and illusory art wizard of Monument Valley (2014), is creating a brand new world: not fantastic architecture this time, but three desks in Melbourne, Australia. He’s starting an independent studio called Mountains along with producer Kamina Vincent and programmer Sam Crisp, and he wants to put people first.

Wong stated on the studio’s website that Mountains is born out of his desire to create a “more creative and healthier” type of games company. Wong’s worked at studios as varied as ustwo, who produced Monument Valley as well as the surreal VR adventure Land’s End (2015); under American McGee in China as the art director of Alice: Madness Returns (2011); and as an independent developer on 2013’s self-explanatory Hackycat (cat + hacky sack = Hackycat. You get it). With that much experience in the industry, it was clear to him what kind of environment he wanted to create with Mountains.

starting a studio in 2016 means putting people first

“I think starting a studio in 2016 means putting people first,” he told me. “We’ve been working hard together to create a company culture where we’re challenged to do our best work, while knowing when to take time off or ask for help.” In an industry notorious for crunch and plagued with toxic work environments, large developers often flake on one or both of these. But, unfortunately, these elements can be vital to any company that wants to put out good work consistently. “My goal is to find a balance between boundless creativity, disciplined process, and a healthy support system,” Wong said. Easier said than done, but he’s confident in his efforts.

A large part of this confidence stems from the company’s location in Melbourne, Australia, in a collaborative workspace called The Arcade. Wong is openly excited about the possibilities that the space presents and the community that it cultivates. “To a person, everyone here has been friendly, helpful and enthusiastic about growing the local industry,” he said, lauding the openness with which people spoke about diversity and self-care to “[make] games in a better way.” Melbourne itself has helped with that; the independent games scene has flourished with crowdfunding and assistance from the government, something Wong immediately saw when he visited for PaxAus in 2014. Mountains’s goal of making “small, beautiful games” is matched by each of the 30 companies that they share The Arcade with, and they look forward to both experiencing and contributing to that atmosphere.

Mountains is beginning work on a premium mobile title, to be released in 2017, that aims to explore what can be done with a touchscreen, and Wong is keen to see them bridge the gap between an experience made for traditional “gamers” and an experience made for everyone. Monument Valley’s simple smartphone puzzles are just the tip of the iceberg.

After such a rich journey with so many different experiences, what’s the most important thing to bring to this new studio? “Pride,” Wong said. “I want my team to leave work each day proud of what they’ve done.”

Keep up with Mountains at their new website .

The post Monument Valley designer’s next project starts by putting people first appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers