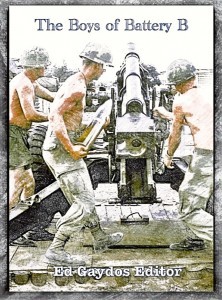

Ed Gaydos's Blog, page 9

August 26, 2015

George Buck – B Battery XO (Executive Officer) – Part One

George Buck held more jobs during his Vietnam tour than perhaps anyone who did time at LZ Sherry.

Fresh into Vietnam, his first assignment took him to the 4th/60th Duster battalion as a platoon leader. After four months of action up and down the Central Highlands he went to the 5th/27th artillery battalion as a forward observer for Charlie Battery. Three months later he became executive officer of B Battery at LZ Sherry, but spent most of his time on air mobile operations. The last six weeks of his tour were relatively quiet. Lt. Colonel Crosby brought him to battalion headquarters in Phan Rang as his intelligence officer, where again he spent a considerable time in the air on recon missions.

If there is a single theme running through these many assignments it is isolation, a bloodless wound suffered by many young men who were forward observers or in small mobile units away from their comrades. Here is how George described it in an email to Hank Parker:

“I recall little from my four months as a Duster platoon leader and then my stints as an FO for C Battery, XO for B Battery and then the S2 job which included doing daily aerial recon around Phan Rang air base. I think one reason I recall so little is that I never had any chance of bonding with anyone. I came to Vietnam on individual orders, went to Dusters, which is a completely different MOS (military specialty different from field artillery), was isolated totally as a platoon leader with no other officers within fifty miles of me, then as an FO with a different non-U.S. unit every ten days for months, rarely shooting for my own battery, and then as XO for only a few months at Sherry, which was, at the time, a new fire base. At the battalion I think I was the only lieutenant, so I was isolated there too. The captain that flew the L19 (recon fixed wing airplane) and I became good friends, but only for about two months and then I was home again and out of the Army. It was a rather lonely existence and to top it off my jeep trailer was raided on multiple occasions and I lost my cameras and film, so I have very few pictures. I wish I had kept a diary.”

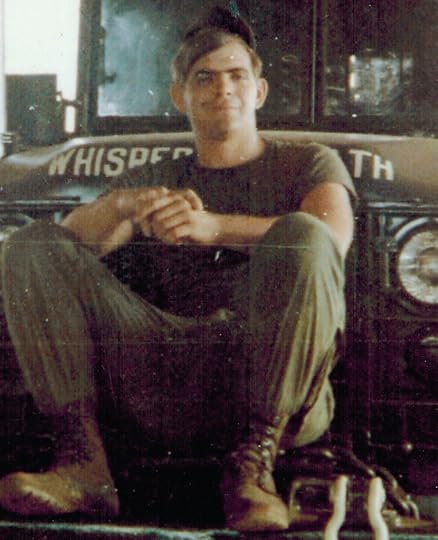

Lt. George Buck at LZ Sherry

Lt. George Buck at LZ Sherry

The start of my military experiences go back to my freshman year at Penn State when I was in Army ROTC. Due to an antiquated law going back to the days of land grant colleges, ROTC was mandatory for all incoming male students. If a college was given land to build its school, in return it had to have mandatory ROTC for the first two years for all male students, with an optional advanced program for the final two years. I chose the Army ROTC program, and at the end of my sophomore year opted for the advanced ROTC program. Then after I graduated on December 17, 1966 I was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in the Army Reserves.

After a few months off I reported to Fort Sill for Field Artillery Officer Basic, which lasted about ten weeks. From there I went to Fort Knox, Kentucky to the U.S. Armor Training Center. Initially I was made Executive Officer of an artillery battery (B Battery, 3rd Howitzer Battalion, 3rd Artillery Regiment), which was interesting since there were other lieutenants already in the battery. I am not sure how that happened but within a month I got bumped by a 1st lieutenant who had been in graduate school, and I spent the rest of the year as the Assistant XO.

Vietnam

The Army put you where they needed you, and not always where you had the training.

In December, 1967 I was on leave for the holidays when I got orders for Vietnam, telling me to report to Oakland, California on January 1. From there I flew to the Philippines and then to Saigon where I was under the control of USARPAC (US Army Pacific Command) RVN. I was a single assignee, not travelling with any unit, so I was not sure where I would end up. Eventually I was assigned to the First Field Forces and spent a week waiting for my unit orders. When they finally came I was surprised that I was assigned as an assistant platoon leader to B Battery, 4th/60th Air Defense battalion, which was a Duster unit and not field artillery. This was an entirely different MOS (military occupational specialty): 1174 MOS and not the 1193 MOS I was trained in as a field artillery officer.

For a newly minted 2nd lieutenant newly arrived in Vietnam, taking his first command job outside his area of training would have been tough. You felt as if you knew nothing, knew no one, and would be forever an outsider – another wrinkle in the curtain of isolation that shrouded George’s year in Vietnam.

I had no clue what a Duster was all about. My only idea of a Duster configuration was the Naval guns on Destroyers and the other big ships that had exposed tubs on their sides with twin 40 mm guns mounted in them for air defense. If you were a fan of the old Victory at Sea shows, these “Duster” tubs were the final defense against Japanese suicide planes.

A Duster was an Army Air Defense weapon that became obsolete once the era of jet fighters became the norm. But it still was effective as a ground defense weapon for strong point security, convoy escorts, and perimeter defense requiring heavy direct fire support. The gun tub was mounted on an old model tank, so it basically was a tank with a tub on top and two 40 mm guns that could fire either automatically or in semi-automatic mode (one shot at a time). We also had attached Quad-50 machine gun units, so combined these platoons of Dusters and Quads were extremely effective in providing fire power superiority and eliminating large enemy assaults and concentrations in a very short time.

So one of the unique aspects of my year in Vietnam is that I was a combat commander in two different MOS categories with three entirely different weapons systems (Dusters, Quad-50s and howitzers). Fortunately the crews on these assignments knew precisely what their duties and missions were, and could function independent of any kind of direct supervision. It is why for the Duster and Quad-50 crews it was a “Sergeants’ War”.

My platoon was located along Highway 19 about in the middle between Pleiku (Battery B headquarters, 4/60th) and the Mang Yang Pass near An Khe. We were at a bridge site with defensive positions on all four corners, a Military Policy shack, and an ARVN (South Vietnamese) Regional Force unit. There was also one tank from the 4th Division commanded by 2nd lieutenant John Abrams, the son of General Creighton Abrams, who had taken over for General Westmoreland, and ran everything in Vietnam. Lieutenant Abrams’ tank was my main defense against a frontal attack on my Duster, and I reciprocated with my Duster providing cover for his tank and defensive position. On the day Lieutenant Abrams became a 1st lieutenant his father flew in and pinned his silver bars on him.

Acosta and Donovan

Our Platoon Leader was a 1st lieutenant from the west coast who was really laid back and a nice guy, what you would describe today as a “surfer dude”. We got along, but I had some very definitive security issues that concerned me, though I was careful not to rock the boat too much. I didn’t believe that we had enough wire out on our perimeter, and I didn’t like the Montagnards (mountain tribe people) coming into our garbage pit rummaging around for scraps. Too much could be salvaged for land mines and other things.

A major issue was that every morning we were the first on the highway, because we had to go up to a 4th Division base camp to get our hot food for the day, which was put in mermite cans (insulated food containers) to keep it warm. Highway 19 had been paved at one point but now it was full of pot holes, so the convoys rode on the side of the highway which was all dirt and easy to lay mines in by the enemy. I wanted our tracks and vehicles to stay on the paved portion since it could not be mined easily, but unfortunately I was not making much of an impact being only the assistant platoon leader.

Two weeks into my tour my first major tragedy and setback occurred. Two of our men driving my jeep up to the base camp for our daily chow were riding along the side of the road and ran over a mine, killing both instantly. It is something that I will never forget. Names and people from my tour escape me, but I remember Acosta and Donovan. It was such a sobering event, the loss of two men, the failure of leadership on my part, something I would live with for the rest of my life, and I was only 22 years old.

George Buck – B Battery XO ( Executive Officer) – Part One

George Buck held more jobs during his Vietnam tour than perhaps anyone who did time at LZ Sherry.

Fresh into Vietnam, his first assignment took him to the 4th/60th Duster battalion as a platoon leader. After four months of action up and down the Central Highlands he went to the 5th/27th artillery battalion as a forward observer for Charlie Battery. Three months later he became executive officer of B Battery at LZ Sherry, but spent most of his time on air mobile operations. The last six weeks of his tour were relatively quiet. Lt. Colonel Crosby brought him to battalion headquarters in Phan Rang as his intelligence officer, where again he spent a considerable time in the air on recon missions.

If there is a single theme running through these many assignments it is isolation, a bloodless wound suffered by many young men who were forward observers or in small mobile units away from their comrades. Here is how George described it in an email to Hank Parker:

“I recall little from my four months as a Duster platoon leader and then my stints as an FO for C Battery, XO for B Battery and then the S2 job which included doing daily aerial recon around Phan Rang air base. I think one reason I recall so little is that I never had any chance of bonding with anyone. I came to Vietnam on individual orders, went to Dusters, which is a completely different MOS (military specialty different from field artillery), was isolated totally as a platoon leader with no other officers within fifty miles of me, then as an FO with a different non-U.S. unit every ten days for months, rarely shooting for my own battery, and then as XO for only a few months at Sherry, which was, at the time, a new fire base. At the battalion I think I was the only lieutenant, so I was isolated there too. The captain that flew the L19 (recon fixed wing airplane) and I became good friends, but only for about two months and then I was home again and out of the Army. It was a rather lonely existence and to top it off my jeep trailer was raided on multiple occasions and I lost my cameras and film, so I have very few pictures. I wish I had kept a diary.”

Lt. George Buck at LZ Sherry

Lt. George Buck at LZ Sherry

The start of my military experiences go back to my freshman year at Penn State when I was in Army ROTC. Due to an antiquated law going back to the days of land grant colleges, ROTC was mandatory for all incoming male students. If a college was given land to build its school, in return it had to have mandatory ROTC for the first two years for all male students, with an optional advanced program for the final two years. I chose the Army ROTC program, and at the end of my sophomore year opted for the advanced ROTC program. Then after I graduated on December 17, 1966 I was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant in the Army Reserves.

After a few months off I reported to Fort Sill for Field Artillery Officer Basic, which lasted about ten weeks. From there I went to Fort Knox, Kentucky to the U.S. Armor Training Center. Initially I was made Executive Officer of an artillery battery (B Battery, 3rd Howitzer Battalion, 3rd Artillery Regiment), which was interesting since there were other lieutenants already in the battery. I am not sure how that happened but within a month I got bumped by a 1st lieutenant who had been in graduate school, and I spent the rest of the year as the Assistant XO.

Vietnam

The Army put you where they needed you, and not always where you had the training.

In December, 1967 I was on leave for the holidays when I got orders for Vietnam, telling me to report to Oakland, California on January 1. From there I flew to the Philippines and then to Saigon where I was under the control of USARPAC (US Army Pacific Command) RVN. I was a single assignee, not travelling with any unit, so I was not sure where I would end up. Eventually I was assigned to the First Field Forces and spent a week waiting for my unit orders. When they finally came I was surprised that I was assigned as an assistant platoon leader to B Battery, 4th/60th Air Defense battalion, which was a Duster unit and not field artillery. This was an entirely different MOS (military occupational specialty): 1174 MOS and not the 1193 MOS I was trained in as a field artillery officer.

For a newly minted 2nd lieutenant newly arrived in Vietnam, taking his first command job outside his area of training would have been tough. You felt as if you knew nothing, knew no one, and would be forever an outsider – another wrinkle in the curtain of isolation that shrouded George’s year in Vietnam.

I had no clue what a Duster was all about. My only idea of a Duster configuration was the Naval guns on Destroyers and the other big ships that had exposed tubs on their sides with twin 40 mm guns mounted in them for air defense. If you were a fan of the old Victory at Sea shows, these “Duster” tubs were the final defense against Japanese suicide planes.

A Duster was an Army Air Defense weapon that became obsolete once the era of jet fighters became the norm. But it still was effective as a ground defense weapon for strong point security, convoy escorts, and perimeter defense requiring heavy direct fire support. The gun tub was mounted on an old model tank, so it basically was a tank with a tub on top and two 40 mm guns that could fire either automatically or in semi-automatic mode (one shot at a time). We also had attached Quad-50 machine gun units, so combined these platoons of Dusters and Quads were extremely effective in providing fire power superiority and eliminating large enemy assaults and concentrations in a very short time.

So one of the unique aspects of my year in Vietnam is that I was a combat commander in two different MOS categories with three entirely different weapons systems (Dusters, Quad-50s and howitzers). Fortunately the crews on these assignments knew precisely what their duties and missions were, and could function independent of any kind of direct supervision. It is why for the Duster and Quad-50 crews it was a “Sergeants’ War”.

My platoon was located along Highway 19 about in the middle between Pleiku (Battery B headquarters, 4/60th) and the Mang Yang Pass near An Khe. We were at a bridge site with defensive positions on all four corners, a Military Policy shack, and an ARVN (South Vietnamese) Regional Force unit. There was also one tank from the 4th Division commanded by 2nd lieutenant John Abrams, the son of General Creighton Abrams, who had taken over for General Westmoreland, and ran everything in Vietnam. Lieutenant Abrams’ tank was my main defense against a frontal attack on my Duster, and I reciprocated with my Duster providing cover for his tank and defensive position. On the day Lieutenant Abrams became a 1st lieutenant his father flew in and pinned his silver bars on him.

Acosta and Donovan

Our Platoon Leader was a 1st lieutenant from the west coast who was really laid back and a nice guy, what you would describe today as a “surfer dude”. We got along, but I had some very definitive security issues that concerned me, though I was careful not to rock the boat too much. I didn’t believe that we had enough wire out on our perimeter, and I didn’t like the Montagnards (mountain tribe people) coming into our garbage pit rummaging around for scraps. Too much could be salvaged for land mines and other things.

A major issue was that every morning we were the first on the highway, because we had to go up to a 4th Division base camp to get our hot food for the day, which was put in mermite cans (insulated food containers) to keep it warm. Highway 19 had been paved at one point but now it was full of pot holes, so the convoys rode on the side of the highway which was all dirt and easy to lay mines in by the enemy. I wanted our tracks and vehicles to stay on the paved portion since it could not be mined easily, but unfortunately I was not making much of an impact being only the assistant platoon leader.

Three weeks into my tour my first major tragedy and setback occurred. Two of our men driving my jeep up to the base camp for our daily chow were riding along the side of the road and ran over a mine, killing both instantly. It is something that I will never forget. Names and people from my tour escape me, but I remember Acosta and Donovan. It was such a sobering event, the loss of two men, the failure of leadership on my part, something I would live with for the rest of my life, and I was only 22 years old.

August 18, 2015

Mike Lindquist – Duster Section Chief

Mike and Jim Logan were in Non-Commissioned Officer school together and together deployed to Vietnam, ending up in the same 4/60th battalion, Jim on Quad-50s and Mike on Dusters.

Five of us made staff sergeant out of NCO school. It was amazing. I was only in the Army at that time eleven months. (It typically took five years to become an E6 staff sergeant.)

My first duty assignment in Vietnam was at LZ Sherry. I went there to fill in for the section chief, Staff Sergeant Twyman, who had re-upped for another tour in Vietnam and was going on a month leave to the states. I flew into LZ Sherry on a chopper in the middle of January, 1970 and my first reaction was how dusty the place was. And hot. I couldn’t believe it.

I remember landing at Sherry and seeing the sign made of mortar tail fins. Sergeant Twyman met me at the chopper pad and showed me where a round had landed. It was no more than twenty-five feet away from our ammo bunker, which was right next to the track. I thought, “Oh boy, what am I getting into?”

4/60th Yearbook Photo – 1970

4/60th Yearbook Photo – 1970

I was at Sherry for six weeks. During my stay we were frequently mortared and we pumped out a lot of firepower many nights. When a mortar round went off, the guy who was on watch would holler INCOMING. Our job was to respond with Duster fire immediately. We’d all race to the Duster, jump into the tub and if we had a sense of where the initial mortar came from, and that was usually from the person who heard the round come out of the tube, we would just start opening up on that point. We would fire ten to twenty rounds, then stop and sit there for another hour. If there was no more activity we would stand down.

You never knew when this was going to happen. My sense was that Charlie was just trying to keep us awake and trying to wear us down. I became a very light sleeper, with one ear awake. Fortunately no one was hurt on our tracks, however several in the gun battery were wounded.

On Reflection …

The craziest and maybe the stupidest thing that I did, one day the XO (executive officer) of the battery came over and said, “We’re getting reports that there’s activity outside the fence, and we want you to go take a look with your Dusters.”

Being new in country and trying to please an officer I said, “We can do that but I got to get permission from my lieutenant,” who was at LZ Betty. I called him on the radio and told him the situation and got the XO from the gun battery on. My lieutenant said to take the recon out and look around, so I followed orders.

I got the two Dusters going and put the XO on the M-60 machine gun mounted on top. Normally I would be on the machine gun, but I said to the XO, “You man the M-60, and I’m going to be on the other side of the tub.” I had fairly quick hands, so I could load the shells fast, and I could direct fire from that position as well.

We went out five or six hundred yards and spent about an hour riding around. Nothing happened, but I thought about it later: Boy, that was really, really dangerous. We were out there all by ourselves. We did not have any support from the standpoint of ground troops or choppers, nothing. If Charlie had been around with a rocket propelled grenade, we would’ve been in trouble.

The identity of the battery XO is unknown, but it fits 1st Lieutenant Rudewiec. He was always looking for a fight, and when there wasn’t action at hand he manufactured something. It would have been very much in character for him to go out to a Duster and say, “Boys, we got activity. Saddle up.” And no place would have suited him better than behind the M-60 machine gun.

Things Could Only Get Better

I was glad when Twyman came back from the states. Beyond the barbecues I don’t remember any fun times at Sherry. I just remember being dirty all the time and dusty. We provided convoy escort to LZ Betty once, and it was hot and dusty all the way there and all the way back. I was very glad to get the hell out of that hot and dusty hellhole!

On the positive side it made me appreciate my next assignments. From Sherry I went up west of Cam Rahn Bay to Firebase Freedom. Once again I took over for the section chief who had re-upped and gone home for a month. Firebase Freedom was much quieter than Sherry. I enjoyed it tremendously, because I’m a hands on guy and we had to build hooches. Us ten or eleven guys were busy filling sandbags and building hooches day in and day out, and we didn’t have to worry about mortars too much. I was there five or six weeks, similar to Sherry, and I certainly enjoyed it there. You could go to the PX for booze or to shop, then jump in the South China Sea. It was almost like a vacation of sorts. But I did wish I could get my own section instead of replacing guys on leave.

From Firebase Freedom I went northwest to Buon Ma Thuot, to a pretty large firebase with two Duster sections. We were on one side of the firebase, and on the other side was another Duster section headed by Duane Skidmore. He was also in NCO school with me and Jim Logan, so we were close and had a lot in common. Duane went to Cambodia for the May 1970 invasion, but I stayed back. Later I went toward Cambodia, but not into it. Again at Buon Ma Thuot things were fairly quiet. I think we received incoming once.

I remember only one piece of excitement. We had to get more fuel and took the Dusters to a fuel dump several miles away guarded by the Vietnamese. We had backed into place and I had gotten off the track and was talking to another fellow when I noticed a fire had started up on the other side of my Duster. The Duster tub was loaded with live ammunition, five hundred rounds of Duster shells along with M-60 machine gun ammo. I hollered to MOVE THE TRACK, but they didn’t hear me. I ran toward the track and somehow or other I landed on top of the back deck. It’s high and I somehow landed flat footed on the deck. The guys on the track looked at me like I was Superman. I grabbed the fire extinguisher and said, “Get this track the hell out of here.” I jumped off toward the fire and was able to get it out. I don’t know how I made the leap but I was able to launch myself. I was a pretty good athlete in high school and I guess being 22 at the time also helped.

Mike still in good shape,

Mike still in good shape,

showing where he landed flatfooted 45 years earlier

August 12, 2015

Mitch Reynolds – Quad-50 Mechanic

I was in the Army for a three year tour. I was drafted for two years and extended a year to get surface-to-air missile school, because they did not have missiles in Vietnam and I did not want to go to Vietnam. About half way through the school they said your math is not good enough to stay in surface-to-air missiles. They said your choices are either automatic weapons or cook school. I said, “I ain’t cooking eggs at four o’clock in the morning. Give me this automatic weapons thing. By the way, what is it?”

Then I said, “What about my extra year?”

They said, “We guaranteed you the school, nobody guaranteed you to pass it. You’re committed to the three years.”

There were twenty-six of us in my mechanics class at Ft. Bliss. Twenty-four went to Korea and two of us went to Vietnam. By then I thought, Thank god I don’t have to go to Korea – too cold and a lot of playing Army.

Junk Yard Mechanic

In Vietnam I was the only guy certified to work on the Quad-50 for the whole battalion. From the headquarters at An Khe they would send me to every place that had Quads in order to do maintenance work. I was on a lot of firebases where it was quite hairy: the Quads were down and people were trying to kill you. Then I would fly back to An Khe, report in and see what else is broke, or they would send me on gun trucks (Quad-50 mounted on the bed of a five-ton truck) running convoy support. I was never anywhere very long.

Mitch on the front bumper of Whispering Death

Mitch on the front bumper of Whispering DeathWorking on those old pieces of WWII equipment was an experience most 19 or 20-year-old people don’t get. I did constant preventive maintenance: tearing them down, putting in new solenoid switches, cleaning them, putting them back together, and trying to get the “Little Joe” Briggs & Stratton engine that moved the guns to work. The drive belts would wear out and the little motors under them would burn out, so you took them to the electrical shop to be rebuilt. Then you’d have to readjust the entire weapon. It was all quite a chore.

The Quad-50 was not being made anymore, so I always had trouble getting parts. Some I had to fabricate myself. The drive motor under the seat that turned the turret, up and down and 360 were plated with cheap Chinese metal. Due to stress and tension they would break off and the bolts would break off. You could not weld them because they would not take the heat. So I built plates out of scrap medal and welded them on underneath the gun turret.

I had a hard time getting barrels for the Browning machine guns. They glowed red when they were fired for a sustained period, which would warp them and burn the rifling out. With the rifling gone and the rounds coming through a smooth barrel, you never new where they would go (like a knuckleball). You could be shooting straight, but the rounds could be going to the left, or right, or up or down

When I couldn’t order a part or make it, I robbed Peter to pay Paul. I would take an old gun mount, take it off the road, take it off the truck, set it up on three 55-gallon barrels and strip it for parts – meaning we only had nine or ten working Quad-50s for the battalion instead of the twelve we should have had.

Memory Slots

My memory is like a roulette wheel. You spin the wheel and the ball drops into a slot. That is what my brain is like trying to remember 40 years ago. I did not get into all of the blood and guts, the gory stuff that other guys did. Fortunately I was always one step ahead of it. For example, we got rocketed last night but I had already left.

I do remember a close call from a sniper. They put me on a helicopter to LZ English near Pleiku, a little firebase of two mortar tubes, a squad of infantry and two Quad-50s sitting on a low hilltop that looked down over the Ho Chi Minh Trail. I had to work on a Quad just north of there at a place I can’t remember the name of. I do remember the Quad would not rotate 360 or traverse up and down because of a broken cotter pin.

I had the front cover off and was leaning over the turret when sniper rounds started pinging off the bat wings (medal shields to protect the gunner). One was an inch and a half to the left of my head. I di-di-mau’d off the truck saying, “I got to go.” (di di mau: Vietnamese for “leave quickly” and borrowed into English by US soldiers)

LZ Sherry

The closest I ever got to getting killed was at LZ Sherry. Naval guns were shooting over the top of us and you could hear the rounds whistle. But one round made a WUMP WUMP WUMP sound. When I heard that funny sound I dove under the Quad-50 truck, just before the round exploded overhead and sent a big chunk of medal the size of a license plate down right beside the truck. They told us afterword a medal band had come off in flight.

I have two other little memory slots of Sherry.

I was working on Logan’s gun. I remember the stick control cotter pin had come out. I was looking out toward the trash dump which was off the southern perimeter in front of Logan’s Quad. I noticed five or six girls we called Coke Girls. They were local prostitutes who also would come out to sell Coca-Cola. This time they were scavenging at the dump when Viet Cong popped up and shot all of them in broad daylight.

……………….

At a place like Sherry you tended to get a little jumpy. One night I called for an illumination round because I saw something in the wire. They wouldn’t give it to me and I was scared to death. After the sun came up I saw it was a trash can laying out there.

The Back Door To SAM

Clerical errors and oversights plagued almost every Vietnam vet. Sometimes Purple Hearts, Bronze Stars and other medals for valor went un-awarded. Or entire foot lockers of personal effects disappeared. Or parents learned their son was missing in action, when he was safely recuperating at an aid station. In Mitch’s case a clerical error had a happy ending.

When I had to leave the surface-to-air missile school because of my math skills they should have given me a different specialty code for Quad mechanic. But when I left Vietnam my records still had the original 16 Foxtrot (16 F) specialty code, on paper making me a graduate of the SAM training. I told them it was a mistake but they said they didn’t care and sent me to Germany to track Russian MIGs. So I ended up in surface-to-air anyway.

August 5, 2015

Jim Logan – Quad-50 Squad Leader

Sergeant Jim Logan –

Picture courtesy Bob Christenson

Sergeant Jim Logan –

Picture courtesy Bob Christenson

Jim went to Vietnam in December 1969 as a Quad-50 squad leader after completing non-commissioned officer training at Ft. Bliss, Texas.

The first part of my tour in Vietnam I was stationed out of Artillery Hill near Pleiku (300 miles north of LZ Sherry). We were on the road six days a week: Kontum, Dak To, Ben Het, LZ Hard Times, LZ Blackhawk and Pump Station Eight. We escorted a bunch of infantry guys over to the Cambodian border in May, and right after that I went to LZ Sherry.

On May 1, 1970 U.S. forces joined South Vietnam units which days earlier had crossed into Cambodia to attack approximately 40,000 Viet Cong in safe haven just over the Cambodian border.

The first thing I saw getting off the helicopter at Sherry was that sign that said WELCOME TO LZ SHERRY. It was spelled out with mortar tailfins, and they were not our tailfins. I always liked that sign.

Picture courtesy Andy Kach

Picture courtesy Andy Kach

It reminded me that a few weeks before I got there one of our guys was killed on the other Quad-50. (There were two Quad-50s at Sherry. Jim’s was on the south perimeter. The other was on the west perimeter where Charles Cordle was killed.) He was hit with a mortar round. I think it was the first mortar round that hit. It landed damn near on top of him.

“Fire power for hire” is what we were. We were supposed to have rounds in the air before anybody else. That’s the way we were trained: first to fire and last to leave. When it started getting dark it was flack jackets and steel pot helmets. We had better flack jackets than the other guys in the battery, with those big ceramic tiles. We were exposed, so we had those great big heavy-ass flack jackets.

At Pleiku I was always on the road and I lived in some pretty primitive conditions, so to get to Sherry and have a permanent bunker was kind of nice. I liked a lot of things about Sherry, most of all the free fire at night (firing at will within a given sector). Everywhere else I had been, the hardest thing to get was clearance to fire. If we could get clearance to fire the enemy didn’t want to mess with us. But if we didn’t get clearance, we’d get messed with. At them other places it took an act of Congress to get permission to fire. At Sherry we were encouraged to fire.

And Sherry was the first LZ I was ever on where they had a great setup of Claymores mines (command detonated anti-personnel mines scattered throughout the perimeter wire). They were already set up when I got there.

Claymores at LZ Sherry containing 700 steel balls, and with the helpful instruction: FRONT TOWARD ENEMY

Claymores at LZ Sherry containing 700 steel balls, and with the helpful instruction: FRONT TOWARD ENEMY

We pulled the blasting caps out of them every morning. I always took the last guard duty at night so that I could reserve that job for myself and make sure the wires were still good on the blasting caps. Then I’d go to breakfast. In the evenings after dinner I would go back out and hook the mines back up myself. There was a wooden box at our guard station with a strip that had all the wires coming from the Claymores. You had another wire with a battery connection that let you fire one Claymore at a time, or just run it across and blow the whole perimeter in case the world was coming to an end.

Want Eggs With Those Shells?

One night a radar guy pulled guard duty with me because their equipment was down and the radar guys were on loan to us. He was – and I don’t mean this in a negative fashion – he was kind of a computer geek and didn’t carry a weapon. He was a technical guy and a nice guy, super nice. After unhooking the Claymore mines in the morning we went into the mess hall. We were the very first ones there.

The mess daddy was a Spec 5 or 6 named Chaves. He never got along with anybody. Chaves always cleaned the grills in the mornings. He would just throw some eggs on there, shells and all, beat ‘em up and wipe the grill up with that, and then start cooking.

My radar guy had never been there early in the morning before. We walk in and Chaves takes one look at this guy and says, “How you want ‘em? How you want your eggs?”

The guy says, “How about scrambled.”

Chaves says, “You got ‘em.” He grabs two eggs, throws ‘them down on the grill shells and all, takes his little beater, wipes them around two or three times till they’re done, puts them on the spatula and pokes them out to the guy. The guy didn’t know what to do. He finally puts his plate out like he’s gonna take them, and Chaves just dies laughing. You had to be there to appreciate it, because Chaves was not a real friendly guy and he fit the part good. That was probably my favorite experience at Sherry, just to be a bystander.

Saved By Kool-Aid

Memories of Vietnam are often a slurry of half-facts and twisted timelines. The incidents veterans remember – in fine detail – are the trivial decisions that saved them from a tragedy, but laid it on another.

We have veteran reunions and when we get together it takes three of us to remember a story, and four of us to remember a name. But I’ll always remember this.

Sherry was the smallest fire base I was ever on, so small the chopper pad and the dump were both outside the wire. And we had to get our water for showers from a well outside the wire. We were supposed to go get water one day and Lem Cox off the Dusters and I were settin’ in the mess hall together drinking orange Kool-Aid. Two of Lem’s crew, Jackson and a guy nicknamed Fluffy, came in and said, “Y’all want to go with us?”

We kidded them and said, “Na. We’re gonna sit here and drink a few more pitchers of beer.” On that water run these guys hit a mine. They medevac’d both of them out and they never came back.

A Permanent Scar

The water at Sherry was so dang nasty it was hard to drink, so when you could you drank beer. Each gun was allowed a case of beer a day. It was Black Label or Falstaff typically. So during the day if we were not on duty, we’d have a hot Black Label or a hot Falstaff, and it would spew out when you popped the tab. Ever since I put ice in everything. A year without ice left a permanent scar on me.

Nights Of Death And Beauty

When it was quiet at night I’d sit up on the gun watching whippoorwills and owls land on the wire looking for rodents. I’d take my M-16 and I’d pick them off. Then in the morning when I unhooked the mines I’d gather them up and take pictures of me with the owl or whippoorwill. (None of these big game photos survive.)

My Quad shot south. I could see LZ Betty’s lights at night (sister firebase five miles to the south outside Phan Thiet). I could look the other way over the Duster behind me on the far perimeter and see LZ Sandy (the other sister battery to the north). I had a good friend on a Duster there, we were in school together at Ft. Bliss. We’d talk on the radio and he would tell me when they were going to practice fire. Every round was a tracer and they would fire high in the air.

Or sometimes fire direction control would call me at night and tell me when they were going to shoot a Willie Peter (white phosphorous: an incendiary howitzer round that could ignite cloth, fuel, ammunition and other combustibles, and sometimes shot as an airburst over enemy soldiers). We would close our eyes when we heard the howitzer go off, so when the round popped it was not like someone jumped up and took a flash photo in your face. They would pop right in front of me. You closed your eyes, then when you heard it bust you could open and enjoy the beauty of it.

White phosphorous impact at Sherry

White phosphorous impact at Sherry

Skilled, Tough, Ready Around the Clock

Mitch Reynolds was the lone Quad-50 mechanic for the battalion, traveling across its 25,000 square mile area of operations to repair aging equipment. He remembers Jim Logan fondly.

What do I remember about LZ Sherry? The dust, the sand, the road that ran to Phan Thiet being heavily mined and you had to sweep it all the time. Lots of mortar fire, a lot of incoming and lot of outgoing. Illumination flares all night long.

I liked going to Sherry because I liked Jim Logan. He was a nice guy. A gentleman with a great sense of humor. More than anything he was a strict military person; he wanted everything the military way because our lives depended on the guns being right and things being correct.

After working on the Quads I would stay for a couple days to make sure they worked right, and I’d pull guard duty at night with the crews. The other Quad-50 crew at Sherry was kind of loose. They had a better guard tower, but they were a little loosey-goosey. Jim and his guys were STRAC.

Later in life Mitch renewed the friendship with Jim and was able to talk with him before he died.

July 29, 2015

First To Fire – Last To Leave

First To Fire – Last To Leave

Motto of the Air Defense Artillery in Vietnam

An Unwelcome New Neighbor

When B Battery took up permanent residence at LZ Sherry in May of 1968 it became a stationary dot in a vast expanse of rice paddies and surrounding jungle, and an irresistible target for the enemy. The battery now lived in a constant state of worry. Foremost was protecting its own perimeter from ground attacks, which fell largely to the battery itself. Its original defenses were three guard towers with machine guns, a handful of small fighting bunkers scattered around the perimeter, and multiple rows of barbed wire festooned with trip flares, Claymore mines, barrels of phu gas, and tin cans containing rocks hung from the barbed wire so as to rattle at the slightest quiver. Soon these light defenses were reinforced by two tanks, temporarily at Sherry for maintenance in exchange for providing added perimeter security at night, and three heavy automatic weapons. The tanks took up their positions on the southern perimeter, while the heavy automatic weapons – a Quad-50 machine gun and two 40 mm cannon units – guarded the rest of the perimeter.

Despite these measures on January 12, 1969 a force of fourteen Viet Cong sappers made it to the final strand of wire and were seconds away from opening an avenue into the firebase for more sappers waiting behind them. They had approached the firebase directly in front of the tank closest to the heart of the compound. The VC perhaps figured in a calculated gamble, Take out the tank and the rest will be easy. An alert tank commander saw the lead sapper raise a rocket propelled grenade launcher to his shoulder, and before the sapper could pull the trigger the tanker fired a canister round directly into him, atomizing his lower body and killing everyone behind him.

Following the January 12 ground attack the two tanks took up permanent residence at Sherry, often leaving during the day in support of ground operations, but always returning at night. There were no more ground attacks, but the VC, and perhaps elements of the North Vietnamese Army concentrated just north of Sherry, took up a relentless campaign of deadly mortar attacks. LZ Sherry guarded the northern access routes into Phan Thiet, an important fuel and supply port. The VC did not like it there and they did not like the newly installed radar installations that gave the firebase a long look into the surrounding country. They wanted it gone.

By August, toward the end of the rainy season, the attacks had taken a devastating toll. Captain Hank Parker, executive officer and then battery commander, recalls, “Out of a full strength battery of six guns and 120 guys, we were down to three guns and 67 guys, and many of them were walking wounded. A full gun crew was eight guys, and we were struggling to find four for a gun.”

Mortar craters filled with monsoon rain

Mortar craters filled with monsoon rain

Picture courtesy Dave Fitchpatrick

Out of Retirement

After more than six months of guarding Sherry the tanks pulled out and another Quad-50 machine gun took their place. Heavy weapons defense for the rest of B Battery’s time in Vietnam now fell to the Quad-50s and the 40 mm cannons, two antiquated but fearsome weapons belonging to the 4/60th Air Defense Artillery. Both were obsolete anti-aircraft weapons from WWII and Korea that had been given to National Guard units when jets had rendered them useless for air defense. They came out of retirement for Vietnam in the belief that the North Vietnamese would have an air assault capability using slow moving helicopters and fixed wing aircraft. When that did not occur, these anti-aircraft relics took on anti-personnel missions, guarding fire bases and supporting infantry operations. The equipment was old and in constant need of maintenance. However both were mechanically simple and at the receiving end capable of frightful carnage.

Duster

The Duster was a Korean War weapon with twin cannons mounted on a tank track and firing a 40 mm round that detonated on impact. Imagine a weapon that fires 240 grenades per minute and accurate at two miles. Now imagine its twin barrels laying down fire 50 yards off a perimeter and raising a blanket of dirt into the air. Now you’ve got a pretty good idea of a Duster.

The Army quit making them in 1959. By Vietnam there were only enough Dusters left to make up three battalions, each with 16 Dusters. The 4/60th was the third and final Duster battalion to go to Vietnam in March 1967.

Duster at LZ Sherry

Duster at LZ Sherry

Whispering Death

The Quad-50 was four 50 caliber machine guns mounted on the back of a five-ton truck. It fired a cartridge as long as your hand and could put out 1500 rounds per minute. When a 50 caliber round hit an object the shrapnel and flying debris could kill a man ten yards away. The Quad-50 first came into use during WWII, most notably in the Battle of the Bulge and at the Ludendorff Bridge when American troops crossed into Germany. In Korea it picked up the nickname Whispering Death. Like the Duster, the Quad-50 became obsolete as an anti-aircraft weapon with the advent of jets. Only four Quad-50 companies made it to Vietnam, three of them attached to the three Duster battalions.

The 4/60th Duster battalion deployed across a 25,000 square mile area of operations encompassing all of II Corp and parts of I and III Corp, an extraordinary mission with just 16 Dusters, 12 Quad 50s, and less than a thousand men. Yet little two-acre Sherry merited two Dusters (First Platoon Alpha Battery) and two Quads (E Company, 41st Artillery).

In the history of B Battery at LZ Sherry the Dusters and Quads became the core of its perimeter security. Their presence bolstered the confidence of its troops and helped to establish Sherry’s reputation within the battalion. Word went around that LZ Sherry got mortared a lot but there was no way it could be overrun. The swagger arose largely from the four killing machines on its perimeter.

First To Fire – Last to Leave

The Quad-50s and Dusters were a quick reaction force, the first to return sustained automatic weapons fire when the battery came under attack. When the alert of INCOMING sounded their crews were out on their weapons and laying fire into their sectors, always under the assumption a ground attack was underway. Every Duster round and every fifth Quad-50 round was a tracer, making for quite a nighttime fireworks display.

Whispering Death at night

Whispering Death at night

Like the howitzer crews, during attacks the Duster and Quad-50 crews were in the open exposed to the rain of falling mortars. They took pride that they were the last to leave the field of battle. As a result they and the gun crews suffered most of the casualties at LZ Sherry.

The 4/60th battalion operations report covering the period when the Dusters and Quad-50s went to Sherry contains sobering casualty statics. During the months of May, June and July of 1969 the battalion had a total strength of 995 men. During that three month period nine were killed in action or died of battle wounds. Another 72 were wounded. None of the nine fatalities during that period were at Sherry. However it is likely that many of the 72 wounded earned their Purple Hearts at LZ Sherry given the overall level of casualties at the firebase during that period.

Over the course of their time in Vietnam the three Duster battalions earned over a thousand Purple Hearts and suffered 201 deaths. Just one died at LZ Sherry. Quad-50 crewman Charles Cordle was killed on February 17, 1970 in a typical mortar/rocket attack. He was a 27 year old Specialist 4, an age and rank that suggest he was a victim of the “oldest first” draft before the lottery. He had been in Vietnam for 13 months, further suggesting he had extended his tour for an early out, common for two year draftees.

Staff Sergeant Jim Scavio, Radar Section Chief, remembers Charles.

Charles Cordle was on the Quad-50 behind my bunker. I believe his nickname was Chicken Man (don’t know why). It is my recollection that he was suppose to go home in just a few days or weeks when he died. Those guys on the quad were my best alarm that we would be hit, always shooting before the mortars hit the ground. If I was on my cot in the bunker, the noise and vibrations from the firing would make you think they were in there with you.

A Sergeant’s War

The Quads and Duster crews were an independent lot, due in part to their wide dispersion. Battalion headquarters of the 4/60th was 300 miles north at An Khe, and their fighting units were dispersed in platoons across half the land mass of Vietnam.

As a result, the war fought by the Quad-50 and Duster gunners in Vietnam was overwhelmingly a sergeant’s war, as detached platoons and firing sections found themselves under the operations control of other types of units. (Charles E. Kirkpatrick, “Arsenal,” Vietnam Magazine, Spring 1989)

At LZ Sherry the Duster and Quad-50 crews exempted themselves from the daily routines of the battery. They did not appear at morning formations, they flaunted haircut and dress standards, and of course were never caught near the standard work details that kept a firebase functioning and in good repair. The first sergeant’s favorite word for them was worthless, but no one at Sherry, including the first sergeant, was not glad to have them there.

Captain Parker sums up the prevailing feeling about the Dusters and Quad-50s.

I honestly believe that when LZ Sherry became a permanent fire support base the higher ups knew we would be an irresistible target, “like a cherry on top of an ice cream sundae,” and they were right. We fended off probes, snipers, landmines, boobie traps and outright ground assaults. We were more than a pest because we were killing NVA regulars and blocking their infiltration route. Vital to our mission was the perimeter support provided by our Duster and Quad brothers. The Quads also provided convoy support and I always felt more secure when I had “Whispering Death” behind my lead jeep. I never forgot that to get to my guns the enemy had to get by the Dusters and Quads first. These guys earned their pay and B Battery boys knew this and respected them.

Historical Footnote

The Air Defense Artillery in Vietnam did not have a single air engagement, not one. Early in Vietnam a HAWK missile unit was fired upon by a helicopter, which the crew thought belong to the North Vietnamese Army. They readied their missiles and waited eagerly for the chopper to return, which it never did. Turns out it was a U.S. helicopter that had simply mistaken them for the enemy. And that’s all there was to the anticipated air war in Vietnam.

*Special thanks to Mitch Reynolds for the box of material relating to the history of Air Defense Artillery in Vietnam.

July 8, 2015

Bill Cooper – B Battery XO (Executive Officer) – Part Five

The Real Story

At the time I told people I picked up a white star cluster flare by accident. But it wasn’t a mistake. I did it on purpose. In fact I planned the whole thing, and no one knew it was coming but me.

In late 1970 troop levels were drawing down in Vietnam, and we were getting soldiers from deactivated units who did not have enough time in country to rotate back to the states. These were guys who were not open to change. First they were pissed off they were not going home, and second they already thought they knew it all. The gun chiefs from other units were as much a problem as the crew members. It seemed to me we were getting loose and sloppy. I wanted to see exactly what kind of shape we were in and how we would respond to a perceived ground attack. The white star cluster was my little test.

I planned all along to take it on myself as a dumb second lieutenant who screwed up. Otherwise I’d be opening myself to disciplinary action, maybe even a court martial.

I went out to the tower by the Duster, the same one at which my friend got his belly scratch, and told the guard to had me a popper. He wanted to give me an ordinary illumination flare, but I said no, give me the white star cluster. I popped it and right away everything broke loose. I was impressed with the reaction time of the guard towers, the quad-50 machine guns, the Dusters and even the howitzers. Then a red star cluster came right over the Duster, meaning the howitzer was about to shoot a beehive round directly into the wire in our direction (a shell with 8000 metal fleshettes fired shotgun style). When I saw the red star cluster I thought, Aw shit. I dove down next to the Duster busting my shoulder up against the track, and WHOOOSE all those fleshettes came flying overhead. I called a CHECK FIRE into FDC and everything calmed down.

I went over to the gun that fired the beehive. The gun chief told me the SOP of the unit he came from was to lower the tube and fire a beehive if a white cluster went up – automatically – and he he had no idea he was supposed to signal with a red star cluster first. Fortunately one of the older guys in his unit did, or I would have been standing on the berm like an idiot and made into hamburger.

Then battalion called thinking Sherry was getting a ground attack. I told battalion I screwed up because a guy handed me the wrong popper. I got chewed out a little, mostly because of all the ammo we shot up.

The true story is I wanted to pop a white star cluster just to see how the battery would react. I didn’t discuss it with anybody, not the battery commander or the first sergeant. In retrospect it probably wasn’t a real smart thing to do.

The next morning in the mess hall several guys from the guns and some of the old timers walked by and gave me a thumbs-up. The Chief of Smoke (senior sergeant in charge of all the howitzers) came up and said, “What happened, lieutenant?”

I said, “I screwed up, Smoke. Just grabbed the wrong popper.”

He smiled and said, “Yeah, right.”

Leaving Vietnam

It was strange when someone would leave to go home. They were just gone one day. No shouting, no yelling, just a quiet ride out. When I left Sherry I felt a little guilty, that these guys were still there and I was leaving.

When I was in Officer Candidate School, shortly after I got word I was going to Vietnam, I was laying in my bed and I asked God if I would be coming back. I heard, or felt – I was not quite sure which – an answer. It was a clear NO. I had never before heard so clear a voice

With just a few days left at Sherry I had a dream about leaving. The Huey supply helicopter that was to take me out was down for scheduled maintenance. However FDC informed me the battalion XO was in the area and I could catch ride out with him. As we are lifting off from the helipad in my dream another Huey helicopter appears and crashes into us. As we are going down I say over and over, “I knew it. I knew it.”

When the great day came for me to leave, true to my dream I got word that my helicopter was down for maintenance. But not to worry because the battalion XO was in the air and would give me a ride. I told my assistant XO about my dream and instructed him to let everyone know I knew my helicopter would go down in a crash.

I boarded the battalion XO’s Huey, put a headset on and held tight to the thumb key that would let me talk to the pilot. As we lifted off you better believe I scanned the sky in all directions for the killer helicopter, which never materialized.

At the officers club in Cam Rahn, waiting for a flight home, I grabbed an empty seat and struck up a conversation with a first lieutenant sitting next to me. They had lost my suitcase so I did not have a dress uniform to go home in. I mentioned to him that I was headed to the PX to buy a khaki uniform for the trip, which was the best I could manage. That’s when he said to me he had gotten a letter from his parents asking him not to wear his uniform home. He said to me, “Can you believe it? My own parents!” He was was almost in tears telling me this.

I said, “Maybe it’s because they don’t want you to be insulted or spit on. Maybe they don’t want you to go through that.”

He said, “Hell no, they just don’t want to see me in my uniform. But you know what? I’m wearing my uniform.”

I flew home out of Cam Rahn on a civilian aircraft. As we lifted off a cheer went up. One person yelled, “Fuck you, Vietnam,” which brought another cheer.

At Ft. Lewis, Washington I processed out and went immediately to the small post exchange for civilian cloths. There was not a big selection because everybody wanted new civvies and you had to take what they had. You saw big guys in pants over their ankles and shirts they couldn’t button. I found a close fitting shirt and trousers, and headed into the restroom to change. There the floor was covered with muddy jungle fatigues, kicked off and just laying there. I remember as a kid seeing snake skins laying in the woods where they had been shed. It seemed to me these guys had shed their Vietnam skins.

My first assignment out of Vietnam was Ft. Riley, Kansas – my third tour there. The family and I were attending church one Sunday in Junction City and as we were walking out someone took my arm. I turned to see Colonel Meis. He said, “You made it alright!” He thanked me for helping his son in Vietnam, who was now, he said proudly, a student at Kansas State University.

Bill would serve a full twenty years in the Army and achieve the rank of captain, not an easy task in the years after Vietnam when the military was shrinking. Through difficulties and setbacks, few of which are recounted in these stories, he never stopped loving the Army with the same fervor of the 17 year old kid who had found a home there.

A proud moment came in 2009 at Ft. Benning, Georgia when Captain Cooper (Retired) and Honey attended the graduation of their grandson Brandon from basic training.

Sergeant Brandon Bridge served in the Army for five years, four and a half of them across five tours of duty in Afghanistan as an airborne ranger.

July 1, 2015

Bill Cooper – B Battery XO (Executive Officer) – Part Four

LZ Sherry

I went to Sherry as the battery XO (executive officer, second in command after the battery commander). There was a first lieutenant there already running Fire Direction Control who should have moved up to the XO job, but he said he wanted to stay where he was. I knew him from my visits to the base and knew we would work well together. At a firebase the battery commander was the guy over everything, while the XO had the running of the firing battery – the howitzers, the perimeter machine guns and Dusters (twin 40 mm cannons) and even the radar units. Bravo battery was one of the best defended bases in the battalion.

I pulled duty from six in the morning until midnight. I would visit each howitzer, guard tower and outpost. In this way I got to know the men and they got to know me.

Lt. Cooper (second from left with shoulder tattoo) hanging with the enlisted guys

Lt. Cooper (second from left with shoulder tattoo) hanging with the enlisted guys

Where Were You Shot?

The battery commander was off somewhere leaving me as acting BC. We got a “red flag” message concerning an inquiry from a congressman about the warrant officer (officer in a technical specialty) who was running our radar section. The red flag designation meant it was urgent, could be answered over the radio in the clear, and had to be answered within 24 hours. Right away I got on the radio to the duty officer at battalion headquarters. It seemed our warrant officer had told his wife he had been wounded. She contacted her congressman and wanted to know why the Army did not notify her that her husband was wounded and she had to find out in a letter from him.

I said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

He said, “You mean one of your guys got wounded and you don’t know about it?”

“Nobody got wounded!”

“Well I need an answer on my colonel’s desk in the morning.”

I walked over to the warrant officer’s hooch and the guy’s laying on his bunk reading a book. He was young, in his early twenties. I sat down on the cot next to him and said, “We have a big problem, chief.”

He said, “What’s that?”

“I just got notification from battalion about some big shot congressman looking into what you told your wife about being shot. And she is really pissed the Army never told her.”

He turned pale and said, “Aw shit.” Then he told me everything, that he told his wife the firebase was hit and he was wounded in the leg.

“Don’t you know the first thing your wife will want to see is your wound?” I pulled out my .45 pistol, chambered a round and said, “Where did you say you were shot?”

He went even paler. I told him he had a choice. If he wanted to go home without a wound he would write his wife admitting he had lied to her. He was to bring the letter with an envelope to me. I would send it to headquarters for copying and mailing on to his wife. A copy would go to the congressman and one into his file.

This was not my first exposure to guys inventing a war record. Right after I agreed to become the motor officer back in Phan Rang, the deal that would get me to B Battery, I was taking a little siesta after lunch. A new warrant officer had a room right next to mine. The walls were flimsy half inch plywood, so you could hear everything next door. I hear this guy come stomping in. He gets on his tape recorder and starts making a tape for his wife back home. He’s telling her, We got hit last night and our compound was overrun. I ran out and got into a bunker to return fire. I’m sure I hit a few, I don’t know how many, but don’t worry, I’m Okay. Finally I’ve heard enough. I get out of my bunk, stomp around and slam the door. I want him to know I heard everything. That evening I was in the officers club having a drink. I saw him come in, and when our eyes met he made an about face and left.

There were two types of soldiers in Vietnam. The ones who inflated their combat experiences for folks back home, or simply invented them. And the ones who asked that family not be told of their injuries; these were the real heroes.

Location, Location, Location

In the field in Vietnam a key survival skill was letting folks know where you were at all times, especially nearby artillery batteries, and especially at night.

I got an early lesson in how dangerous mix-ups can be. A heavy artillery battery to our north at LZ Sandy had closed, and the Tactical Operations Center (TOC) had given us a free fire zone for that area, which meant we could fire at will. Every night we plotted the location of friendlies on our maps and had no reports of anyone there. That night our radar picked up activity right at that location. Figuring it was Viet Cong we called up two howitzers and unloaded five rounds apiece on top of it, at which all movement stopped.

The next morning we got a visit from a TOC investigating officer with clipboard in hand. It seems a ROK unit (Republic of Korea) had sent a few people to the old firebase to see what they could scrounge. They were most probably looking for PSP, metal runway material used to build hoochs. They had failed to tell the folks at the TOC what they were doing and as a result walked right into our free fire zone. Fortunately I don’t think we killed anyone. I liked the ROKs; they were tough soldiers generally feared by both the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army. But sometimes they were a little too independent for their own good.

Duck

A second important survival skill was knowing when to duck.

When I was the night duty officer I would sometimes fire “killer junior” rounds out over the wire. These were high explosive rounds with a time fuse set at .5 seconds that would explode in the air just outside the wire. I called FDC to tell everyone it was coming and to take cover. I no sooner fired the round in the direction of the Duster than I hear CHECK FIRE, CHECK FIRE and MEDIC, MEDIC. I rushed over and saw Doc with a guy holding his gut and there’s blood all over the place. I thought, Shit man, I done hit one of our own.

Doc walked the guy to the medic station and pretty soon had the bleeding stopped and him cleaned up. The wound turned out to be just a surface scratch that bled a lot. And it was a wound he had coming. He was an E-5 sergeant sitting at the outpost next to the Duster drinking a beer with his gut hanging out of his flak jacket when word came down from FDC about the killer junior round. The guard on duty at the Duster told him to get down and he came back with something like, Go screw yourself. Shortly after that the round went off.

The next morning I was sitting in the mess hall with the first sergeant and this guy comes in with his stomach all bandaged up like a mummy. He said, “Who initiates the paperwork for my Purple Heart? Do I do that, or do you guys?”

I dropped my fork, turned to the first sergeant and said, “Get this guy out of here before I get ahold of him.”

June 24, 2015

Bill Cooper – B Battery XO (Executive Officer) – Part Three

Vietnam

I reported to the 512th Artillery Group in Dalat, and the next day flew south to Phan Rang to join the 5th Battalion of the 27th Artillery Regiment. I had a long talk with the battalion XO (executive officer and second in command: usually a major at the battalion level) and told him I wanted to be at a firing battery, I wanted to be on the guns. Then I made the mistake of mentioning my supply background, and his eyes lit up. His supply officer had been sent home after going down in a helicopter. He said if I helped him out he would see to it that I got to a battery.

At Phran Rang

At Phran Rang

Adventures In Supply

I inventoried the entire battalion and discovered there were some strange things that needed to be straightened out. Four helicopters sitting at battalion were not accounted for anywhere on the books; that is, nobody owned them. Everyone I asked, including the pilots, said, “There were here when I got here.” I would hear that excuse a lot. The Army has a special category for such equipment called Found On Post. So I declared them FOP and added them to the battalion inventory.

After dealing with the four extra helicopters, I discovered we were missing a lot of equipment, one of which was a ¾ ton truck. The battery commander had signed it out, but now had no idea where it was. In the course of looking for missing items I made a visit to the air base at Phan Rang to verify the existence of air conditioner units that were on our books and supposedly being repaired by the Air Force. I took along some strip steaks from the mess hall as my calling card and introduced myself as the new supply officer. They showed me the units in the repair shop which were waiting on parts. Then someone pops up and says, “By the way, can we keep the truck?”

“You’ve got one of our trucks?”

“Yeah, they gave it to us for personal use, to run into town and to the beach.”

And there it was parked in back, the battery commander’s missing ¾ ton with all the right bumper markings. The Air Force was fixing our air conditioners as a favor, not as something they had to do, and the jeep was a return favor. I did not want to blow this situation and said, “Of course the Air Force can keep the truck for now. I’ll have you sign a hand receipt and all will be fine.”

I went back to the battery commander who had signed for it and said, “I found your missing truck.”

He perked up and said, “Wow, great, where is it?”

“You’ve loaned it to the Air Force and here’s the hand receipt to reconcile your books.” He was thrilled there would be no report he had lost a truck.

Then there’s a funny story about an Air Force jeep. I inventoried the equipment at all the battalion firebases, and when I was doing Charlie battery near Dalat I went to enter the numbers from one of their jeeps into my inventory log and saw that I had already accounted for it. It seems that I had two of the same jeep. The battery commander had no idea what was going on. So I went back to battalion to talk to the supply sergeant in charge of the rear operations for the batteries. “A jeep you have here, that same jeep is out at the firebase.”

He got a weird look on his face that said, “Oh crap.” We went out to the vehicle yard and found the jeep. The USA numbers on the hood, the bumper markings and everything matched the jeep out at Charlie. I took my Zippo lighter and scraped a little on the bumper number and under the olive drab paint it was blue. I scraped a little bit more and found a different bumper number.

So here’s a jeep that obviously belonged to the Air Force. The supply sergeant pleaded ignorance, “I don’t know. It was here when I got here.”

I took the jeep back to the Air Force, to the AP station. I got the runaround from a sergeant there. He said, “What’s up, lieutenant?”

“I got a jeep out here that belongs to you and I want to return it.”

He said, “I’m not missing a jeep.”

“Well the Air Force is missing a jeep and I’ve got it outside.” He started fiddling around and finally I said, “I am getting in my vehicle outside and leaving. You do whatever you want with the jeep.”

Lots of shenanigans went on at that Air Force base.

Then there was always the combat loss option for firebases. I’m not sure what battery it was, but they got an incoming mortar or two and afterward reported that a 1 ½ ton trailer and all its contents were destroyed. They wrote up the combat loss with enough stuff that it took three trucks to deliver it all. Even a generator – oh yeah, a generator was on that trailer. Whatever they needed at the time was on that trailer. Cracked me up.

Another fun situation started with that supply officer who was medevac’d and I replaced. My first duty was to gather up all of his stuff and send it home to his wife, except for his Playboy magazines. Under his bunk I found a box with three M-16 rifles wrapped in cosmoline (a brown waxy rust preventative). I checked and they were not on the books. I kept the rifles and glad I did.

A lieutenant came in one day with one of his men who was in trouble. He was riding on a helicopter with his M-16 sitting on the deck, and when the chopper banked the rifle slid out the door. Losing your weapon was a big deal. He would have had to pay for it and probably would have received some kind of disciplinary action. I told them to come back after lunch and we’ll see what we can do. I went and got one of those M-16s and did what’s called an inventory adjustment report. I dropped the serial number of the weapon that was lost and substituted the number from the un-inventoried M-16. The lieutenant and his E-4 came back after lunch all worried about what they were going to do. I reached down behind my desk and handed the M-16 to the E-4 and said, “All you got to do is not lose this one. Now get out of here.”

The Smell of Junction City

In addition to all my supply duties they made me the battalion paymaster, a job nobody wanted. At the end of every month I would go to Cam Rahn Bay and pick up $150,000 in military pay certificates, the paper script the military issued in lieu of greenbacks. It took me three days traveling by helicopter to pay everybody in the battalion because we had people spread out over a large area.

I was paying the people at B Battery out at LZ Sherry, sitting at a folding table outside the first sergeant’s hooch under a canopy with my paperwork and suitcase of money and soldiers in a line coming up one by one. A young man came up to the table, saluted and said, “Specialist Meis reporting for pay, sir.”

I looked up and said, “I smell Junction City, Kansas on you, soldier.

He said, “How do you know I’m from Junction City?”

“And your father says Hello.” Then I told him how Lieutenant Colonel Meis had helped my family find housing on short notice and that he had given me the card with his son’s unit on the back. “I promised your dad if I ran across you I’d do whatever I could to help you, and I will. Don’t forget that.”

Running into the colonel’s son was the highlight of my paymaster job. I asked the battalion executive officer how much longer I had to put up with this pay officer crap. He said until another dumb ass 2nd lieutenant shows up.

The Traveler

I loved being away from battalion out with the troops. I especially enjoyed visiting the firebases. I never asked them why they needed things, just how much and when. I would stay overnight a lot, which shocked them. They said other rear area officers would never think of staying overnight at a firebase.

Lt. Cooper on the road

Lt. Cooper on the road

On one of my overnight visits the battery commander said I could use the extra bunk in his hooch. The motor sergeant overheard him and later said to me, “Don’t do it. You can sleep in the motor pool area.” I thought this was strange but took him up on his offer. That night someone threw a hand grenade into the battery commander’s hooch. The dumb ass who threw it had pulled the pin but not the shipping safety wire, so all it did was scare the crap out of the captain. Seems he was not well liked.

I made a lot of jeep trips to Cam Rahn Bay, because that’s where everything came into Vietnam. I made friends with the people there and got access to every type of chopper and fixed wing I needed. On one of those trips my driver and I were fired on from the roadside brush. The driver slowed down and I had to yell at him to get moving. Later I said, “Don’t ever slow down to see who is shooting at you.” We had a hole in the front of the jeep just below the windshield on my side. I don’t know the caliber but I could stick my finger through it.

The battalion XO did not like my being on the road so much. When he got wind of this incident he told me to curb my trips off base. His exact words were, “Cut that shit out.”

A Favor Returned

One day Specialist Meis came into my office saying he needed help. He was going home and the rear area supply sergeant was giving him grief about missing gear. I took him into the back and loaded him up with what he needed. I then had my driver take him by jeep to Cam Rahn and stay with him until he was loaded onto a plane for home. He was very grateful and promised to give his dad my best.

“At” Did Not Count

I had been in Vietnam for three months now and it was time to pressure the XO about his promise to get me to a firing battery. The supply job was great, but I was an artillery officer, not a supply officer, and it looked bad on my record not to be shooting. Being shot at did not count.

The XO and I used the Air Force officers club every chance we got. After more than a few drinks I pushed him about getting to a firebase and he finally said to see him in the morning. I was in his office first thing. He had a hangover but fortunately remembered our conversation. He said he had a great deal for me.

The motor officer was going home right before a big inspection in a few weeks. If I would take the motor officer job through the inspection he would be very grateful and would make good on his promise. What could I say? The motor officer slot called for a captain, which would look good on my record to hold this job as a second lieutenant.

I took the job, but ignored the order to stay out of the field. I still visited the firebases; the draw of firebase action is what kept me interested. That’s how I got the idea to create a mobile maintenance rig. It involved a trailer and mechanic that could be airlifted to the firebases for fast on-site vehicle repairs. The battalion commander and XO ate it up, especially since we passed the inspection with flying colors and the inspecting colonel was impressed with our flying maintenance team.

Now I got the XO up to the Air Force officers club again. He was soon to go home, and after the required number of drinks he cried, and I did too. God bless him he said I could have any firebase I wanted. I picked Bravo Battery at LZ Sherry because it was the firebase with the most action and was in a remote location. I was glad to finally be part of the real action and on my way to shoot. Before leaving I was given the Army Commendation Medal for my work as supply and motor officer. It was nice to be appreciated.

June 17, 2015

Bill Cooper – B Battery XO (Executive Officer) – Part Two

Bill has been in the Army for ten years with the rank of E-6 staff sergeant. He is married to Honey, who he met on his first tour in Germany, and they have two children. On a second tour in Germany he becomes the battalion supply sergeant, normally an E-7 slot. When his 24th Division returns to Ft. Riley, Kansas he goes with it under the promise of promotion to E-7 and a permanent assignment as battalion supply sergeant.

I am now twenty-six, a husband and father. I have almost ten years in the service and had gone far on the Germany assignment. We had two children in Germany and I had made E-5 and E-6, not a bad two years as things go in the Army. I am no longer just a truck driver. I have grown. I have been responsible for millions of dollars worth of equipment and shouldered some very high responsibility. I am feeling pretty good about my life so far.

E-6 Cooper with wife Honey and daughter Janet

E-6 Cooper with wife Honey and daughter Janet

Then as always something came up to set me on another path. On a nice sunny day an E-7 walked into the office and announced he was taking over as the new battalion supply sergeant. I was pissed! I ran to the battery commander and said, “What the hell?” He said he knew nothing about it. I then went up the ladder to the battalion XO and he said the E-7 had been assigned by the Department of the Army and there was nothing he could do. I told him I was promised the E-7 position and this was a rotten deal after all my work in Germany. He was very quiet, a major probably not used to being shouted at by a sergeant. Oh well. I knew there was no way I was going back to being a battery supply position. Just as I was thinking how to handle the situation the answer walked in the door. It was a turning point in my life and career.

Three sergeants from firing batteries walked in and said, “Coop, we’re going to OCS (Officer Candidate School). Why don’t you come along?”

I thought for a moment and said, “Hell yes.”

We all filled out paperwork requesting OCS and that’s when I found out you needed two years of college, and me a high school dropout. I was lucky I had gotten my GED equivalency on my first tour in Germany, and now I took a walk over to the education center. I took some tests and gave them information on schooling and positions I had held, and walked out with two years of college equivalency and then some.

Out of the three sergeants who applied to OCS with me, one was turned down. Seems he had hit a 2nd lieutenant somewhere in his career and they did not think him officer material. Another failed the OCS test and dropped off. That left two of us waiting for a class date. I asked for artillery OCS at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma.

I found a nice apartment for Honey and the kids in town near Ft. Riley. I would go to Ft. Sill alone. I felt that if I had them near me I would not study as hard. I would be almost twenty-eight years old while the average guy in OCS was a lot younger with all the advantages of college and good study habits. It would be hell not having my family near but it would be for the best. I was ready to give it a shot.

OCS