Ed Gaydos's Blog, page 12

January 21, 2015

Alex Taubinger – Forward Observer – Part Three

PART THREE

Congratulations

I went out with the 3/506 infantry and bounced around with different units. I was with C Company when the VC and NVA hit that Special Forces camp on February 12. That was the same operation north of Sherry when Hank Parker and Captain Wrazen of D Company ran into all that trouble (three infantry companies of the 3/506 up against a heavy concentration of NVA).

Three months into my tour I was out with the 3/506 infantry setting up an ambush on a trail coming out from The Toilet Bowl.

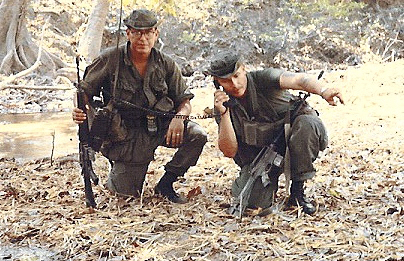

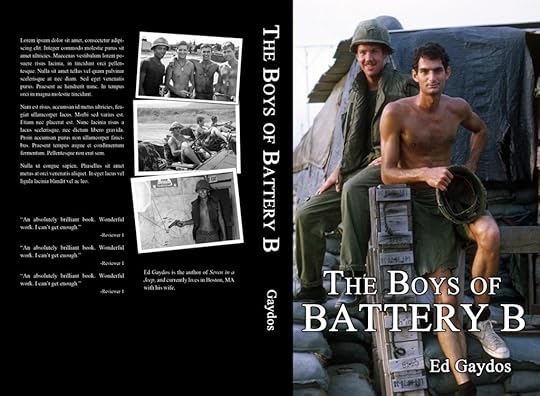

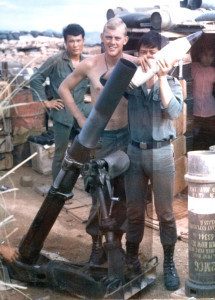

Lt. Taubinger (right) on ambush operation with radio operator Eddie Sandoval

Just after this picture was taken, Blackhawk (radio handle of the battalion commander) flew over in his helicopter and dropped a box of cigars for me. Inside was a note from the Red Cross saying my son Victor had just been born on March 16.

Just a Simple Little Two-Grid Sweep

We were told we’d just go out to sweep two grid squares (an area approximately one mile long and half a mile wide) at the base of Titty Mountain northeast of LZ Sherry, and then come back in. I go out there with no food, a couple canteens, a basic load of ammo and my radio operator, who was a volunteer from the 320th and who just happened to be hanging around the Operations Center at the time and who was supposed to go home within the week. We hop on these Slicks (The UH-1 Huey helicopter – the workhorse of the infantry. Called a Slick when it carried no armament of its own except a door gun on each side).

Slick transporting troops of the 3/506

It’s my first combat assault. We can see all these Cobra gunships shooting up the area. I say to the commanding officer sitting next to me, “Wow, there’s something happening out there.”

He says, “Yeah, that’s where we’re going.”

All together there are three Slicks with 28 people. I am on the lead Slick with the company commander, the platoon leader, a machine gunner, three radio operators, and maybe a couple other guys. Coming in we encounter heavy ground fire. My radio guy takes three rounds in the radio he is holding between his legs and he starts shaking. I am the first one off the lead Slick; bullets are flying at us. We get on the ground in the middle of this rice paddy and we’re getting hit with everything they got – mortars, rockets, AK-47’s. We land right on top of their regimental headquarters and they must have a battalion with them judging by the fire we are taking. These are the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), the real McCoy, the guys with pith helmets with the red star on them.

Our company commander is talking on the radio to Blackhawk (radio handle of the battalion commander) who is flying around up in the DEROS zone, which is 5,000 feet or higher because the VC and NVA could not shoot down the aircraft at that height. They are having an argument about where we are on the map. Blackhawk thinks we are two miles north of Titty. I get the artillery to fire a smoke round to what we believed are our coordinates, and sure enough we are where we think we are, right next to the west ofTitty Mountain.

DEROS stands for Date of Estimated Return from Overseas, a date emblazoned in every soldier’s mind as the day he would go home. Few could say what the letters stood for, but everybody knew what they meant. Flying in the DEROS zone meant the occupants of the aircraft were more likely to see that date.

When a second set of Slicks tries to come in with the rest of the company the lead helicopter is hit, forcing all of them to turn around. That leaves just the 28 of us on the ground. We are surrounded and outnumbered about ten to one.

On the ground we are pinned down. Every time I move I take automatic fire. The only thing that comes into my head is to try an old John Wayne thing, stick a hat up. My radio guy crawls ten yards away from me while I get my M-16 ready, and using his rifle barrel lifts his helmet up just a little over the rice paddy dyke. I see tracers coming at it from behind a banana tree and I empty my whole magazine into that tree. Well, the shooting stops.

Then we crawl into a rice paddy irrigation ditch with a couple infantry guys. We’re still pinned down by fire. I want to call in artillery fire, but we can’t because there are by now too many helicopters in the air and fighter jets are on their way in.

I’m there with a platoon leader, Magouyrk, who I knew from FSB Zewart up at The Toilet Bowl. We pinpoint the location of one of the machine gun bunkers and Magouyrk says, “I’m going to get my Medal of Honor today.”

All I can think to say is, “Okay.”

I am staying hunkered down in that ditch. I reach for my canteen and see a snake crawling across my leg. I turned to an infantry guy next to me and say, “What should I do? If I stay here I might get bit. If I stand up I might get shot?”

He says, “Fuck you, sir. I’m outta here.” He takes off, and the snake goes on his way too.

I turn to look down the ditch and see Magouyrk. He says, “Come on Alex, let’s go.”

I say, “I’m not getting up.”

He stands up, runs in the direction of the machine gun bunker, and lobs a hand grenade inside, which quiets the machine gun. Magouyrk makes it back to our ditch, but on the way takes a bullet in the arm.

Then another machine gun and a mortar open up on us from a different direction. All afternoon we are under mortar and rocket attack. Three of our guys are killed and quite a few wounded. Just about everyone of us is out of ammo. This was supposed to be just a two-grid sweep, not a major firefight. The Dust-offs (Medevac helicopters) coming in for the dead and wounded also bring fresh ammo.

We decide to call in an air strike. I manage to contact the Air Force FAC (Forward Air Controller in the air in a light aircraft). I have never done this before, and I ask him if he has anything on station. He says yeah, he’s got a couple of F-4s and some 104s (both jet fighters). He tells us to mark our perimeter, which we do with smoke flares.

Soon we see the FAC plane coming in at tree top level and dropping smoke flares to mark targets for the jets. They are DANGER CLOSE, about 50 yards in front of us. The FAC says, “We’re gonna be coming in pretty close to you. Tell that idiot that’s standing up to sit down.” That idiot is me standing up taking pictures. (Alex made it out, but the pictures did not.) All of a sudden I hear this god-awful noise, an F-4 coming in straight down shooting his cannons. This thing screams, scares the heck out of me. The Air Force also comes in with napalm and 250 and 500 pound bombs.

At the same time helicopters are taking care of our flanks and rear. Of course all the enemy did was get back in their holes and smile up at the jets and helicopters. Even Hank’s unit, which was southwest of us, made an attempt to come in and get us.

Then the 69th Armor tried to come in with tanks. Someone told them the only ones alive are the gooks, and the tanks open up on us with beehive rounds. They hit five people. Our medic panics, “What do I do? These guys have got holes in the backs of their heads.” Someone tells him not to say that because the guys are still conscious.

All of a sudden the tanks back out. A recon guy from the 3/506 LRRPs (long range reconnaissance patrols) who was with the tanks told me afterward that they started getting hit from the side with B-40 rockets, so they pulled out. He told me he too got the word there were no more Americans left in that rice paddy.

Dust-offs come in to get the wounded; nobody died in the tank attack. Every time they drop down ammo for us.

We spend the whole night there. No food but plenty of ammo. First thing the next morning a South Vietnamese unit is able to break through. An older gentleman with medals up his chest and over his shoulder is the battalion commander, although he is just a captain in rank. He is a good fighter and the real deal. He jumped at Dien Bien Phu with the French.

A sweep of the contact area at daylight reveals that the enemy had fled under the cover of darkness. Two prisoners-of-war carrying important documents were captured during the sweep—one from the 240th NVA Battalion and the other from one of the Main Force Viet Cong Battalions.

I go looking for the NVA soldier behind the banana tree. He is there all right, laying on his stomach. I use my boot to turn him over and his entire mid-section is like Jello. My boot goes four inches into his body before I pull it out. He has a bag with him that I open and find full of medical supplies, even plasma IV bags. This is first class stuff. Inside the bag is a piece of paper stating, “These medical supplies were donated by the Students of Berkeley and Joan Baez.” Boy. I, my RTO and a couple of other soldiers are really pissed when we see that. We give the bag to the company commander to be turned into battalion intelligence and never hear anything more about it.

The total body count is 94 enemy and three soldiers from the 3/506th Infantry KIA. We are pulled out around 10:00 that morning.

A few months later Magouyrk gets the Distinguished Service Cross, the company commander gets a Silver Star, and there are tons of Purple Hearts given out. The company commander put me in for a Silver Star, but I did not receive it that day. Everybody keeps asking me if I got it yet even four months later. I learn later it was approved all the way up through the 101st Airborne Division level, but got killed somewhere back down at Artillery. I don’t know why.

I go out later with the Vietnamese battalion commander who helped rescue us. He wants me to walk point with him. He tells me one day, “This is the safest place because they usually let the point man through an ambush. I want you up here with me.” He has his little map folded up, and he knows exactly where he is all the time. For about a week I walk with him through the Le Hong Phong mountains northwest of Sherry. (Major stretches of the Ho Chi Minh Trail ran through this heavily forested area.)

Notes:

* Hank Parker says the tank that fired on the U.S. forces was ironically the one that had saved Sherry from the ground attack on January 12.

* The Berkeley campus was a hotbed of anti-war protest, with Joan Baez and other notables fanning the flames. However there is no evidence of direct support of the VC or NVA. Baez did join a peace delegation in 1972, under Amnesty International, to bring mail to US POWs in Hanoi. At the same time she was highly critical of the Hanoi communist regime and later of the Chinese communists. She sponsored a number of organizations dedicated to non-violence, and seems to have spread her criticism around equally. If the supplies did originate from Berkeley and Baez, they were most likely meant for humanitarian relief: civilian clinics, POWs, etc. The Viet Cong secured U.S. weapons of all kinds, including Huey helicopters. Filching civilian medical supplies or buying them on the black market was relatively easy. It was perhaps naive to believe they would not find a way into unfriendly hands, but probably not intentional.

January 14, 2015

Alex Taubinger – Forward Observer – Part Two

PART TWO

Nobody Parties Going Over

I deploy out of Ft. Lewis, Washington and the first place I hit is the officer’s club, and who do I run into but a lot of my classmates from Officer Candidate School from different parts of the country. One of the guys refused to get on his flight to Nam because his bags had not shown up. Duh. What do you mean your bags didn’t show up? We were not supposed to bring anything with us but underwear, socks and a toothbrush. Now another guy, who was in my unit in the 6th Infantry Division, had a reason for extra luggage. He had orders to become a general’s aid. The letter from his sponsor in Saigon said, If you don’t know how to play tennis, be sure you learn. Bring your golf clubs, and if you don’t know how to play make sure you learn. And bring a lot of short sleeve civilian shirts and shorts.

We’re all sitting in the officer’s club. The general’s aid and two or three warrant officers were already drinking when I got there. On the plane we all five of us end up in the same row. After we take off somebody pulls out a bottle of Scotch. We land in Alaska and one of the warrant officers asks if anybody’s been here before and I say, Yeah I was here on the way to Korea and there’s a bar at the end of this walkway. We went and talked the barman into selling us more Scotch. On the plane we kind of tied one on. Everybody’s quiet on the plane except our row. We’re having a good old time. We asked the stewardesses for soda water and they said they couldn’t have anything carbonated on the plane. It might blow up and we’d get hurt. So they brought us plain water and ice, and as a matter of fact a couple of them wanted to join us. One of them said, “Everybody parties on the way back; nobody parties on the way over.”

Then this Air Force full colonel comes back from about six rows in front of us. He wanted to know our names. We got silly with him and asked each other what our names were. “What is my name anyway?” He turned us all in when we landed in Saigon. This Army captain calls us out of formation and wanted to know what happened on the plane and we told him we partied on the way over because next weekend we could be dead. He said, “The Air Force guys are clearing out in about a half hour. I’m supposed to be punishing you guys, so just don’t show your faces.”

Forward Observer School

Right off the plane I was assigned to the 5/27 Artillery headquartered in Phan Rang, which is part of the larger 1st Field Forces covering all of central Vietnam. The first thing they did was send me to FO school up in Pleiku run .with mostly Armored 1st Cavalry guys in it.

Artillery officers entered Vietnam with formal forward observer training from Officer Candidate School. The in-country FO school was a one week refresher on the protocol for calling in fire and basic map reading. It also covered conditions unique to Vietnam – such as the rules of engagement, how to call in Air Force support, and the details of calling for Naval gun fire, which used a different sequence and worked in yards whereas the Army did everything in metric.

It was a humbling experience for an artilleryman trained at one of the Army’s excellent schools to discover on entering Vietnam 1.) How much he had forgotten over the months between graduation and finally landing in Vietnam, and 2.) How little his formal training resembled the way things were done in Vietnam: protocol, slang like another language, and shortcuts both approved and invented – all this while under mortar, rocket and sniper attack.

I first met Hank Parker during my departure to FO school. Hank had already been in country a couple months. Me and Mr. Parker – they will never forget us. Because we were not part of the 1st Cav we got to go to town a lot. One day we went to this bar. It’s after 5 o’clock curfew and the MPs come in. We show them our 1st Field Force patches, meaning they had no authority over us because they were 1st Cav. Hank told them we were attached to MACV (Military Assistance Command Vietnam – the umbrella organization for all forces), so they let us go.

That night while we’re still in the bar Pleiku came under attack. Here we were with no weapons. What are we going to do? I hid underneath the couch in the bar. I don’t know what Hank did. In the morning we got a ride from the 1st Cav back to base.

Our last night in Pleiku there was a party. We’re in a hooch drinking away and all of a sudden we get hit with mortars and rockets. Our side of the base was 25 yards or so from the perimeter. We run out with our weapons, and I see the silhouette of one of our guys standing on top of a bunker with arms spread out and telling people to stop shooting because he is God. All these different colored tracers, green and red, were flying around him. He had to be high on drugs.

Five or six of us tried to cram into a little one-man bunker because we were getting hit with rockets and mortars. Then everything just stopped all of a sudden.

The next day we caught a flight to the Phan Rang Air Force base on a C-123. As we were getting on the plane the pilot recognized Hank. He was Hank’s next door neighbor in Idaho. You know, Hank’s father was in the Air Force (Senior Master Sergeant, Load Master), so we got first class treatment, meaning we got to wear helmets hooked into cockpit communications and sat forward looking through glass partitions on the belly of the plane. We went out over the water on our way down the coast and all of a sudden the pilot asked Hank if he should try to dip his propellers. He flies right down over the top of the water and I swear to God the props were going to hit. It dawned on me if the props hit we’re going to go flying like a cartwheel. (No doubt a routine pilots pulled on new guys. The propellers on a C-123 sat well above the belly of the plane.) Then we buzzed a san-pan and as we approached you could see these guys standing up with their rifles shooting at us. We also buzzed a freighter as we flew over Cam Ranh Bay. The pilot came over the radio and said, “I hope they couldn’t read our tail number.”

We get to the air base to a little building, which was the passenger terminal. We saw a poster for an Australian all-girls band at the officer’s club – tonight. So we went up there and we were about as scruffy as you could get. We’re watching the show, which wasn’t worth much, drinking booze. I bought drinks for the jet jockeys with century patches, guys with 100 hours. This one major came up to Hank and called us filthy grunts. “Why don’t you oink like a pig?” Hank got into a fight with the guy, which led to them tossing both of us out.

As Hank Parker relates the incident …

Alex and I were pretty scruffy and hadn’t changed fatigues for over a week. We resisted turning our rifles in, which was the protocol at Cam Ranh at the time, but we did, however we continued to wear our .45 pistols. The major was a real jerk and finally I had had enough and said, Well let’s go outside and settle this. I was not going to strike a major and figured would come out and just order Alex and me to leave and that would be the end of it. Well holy shit he knocked the crap out of me, knocking me down. He was a big son-of-a-bitch. So I got up and charged and tackled him, swinging as he hit the ground and ripping off a shoulder patch that said, “Kill a Cong for Christ.”

It was over pretty quick. The Air Police pulled me off him and told Alex to get me to the hospital to fix my little finger, which he had nearly bitten off. At the hospital the medic said for a little guy I had really beat up the major: gave him a broken nose, two black eyes, front teeth knocked out and a broken rib. The Air Policeman butted in and said the major was a real pain in the ass, “Just list it as closing his finger in a door and hitting his head. Now hurry up, we need to get these guys out of Dodge.”

We get out to LZ Sherry and I’ve got a black eye and splinted finger. The battery commander says to Alex and me, “FO school looks like it was pretty rough.” Even though the official medical record was on my side, the battery commander did ding me on my evaluation for having poor tact. Of course Alex laughed his butt off at me.

I still have that damn patch.

The Toilet Bowl

Out of FO school I was assigned to B Battery at LZ Sherry. The day I got there – I didn’t even get to situate myself – a helicopter picked me up and took me to a fire support base called FSB Zewart with three guns from D Battery, 2/320th Artillery (a howitzer battery under the operational control of the 5th Battalion). I was their safety officer and I also FO’d off of that hill. We were on the top of a mountain in an area called The Toilet Bowl. It looked like an old collapsed volcano and took its name from the shape of the rim. We also had a platoon from the 3/506 Infantry. I was there just three or four days.

FSB Zewart on the rim of The Toilet Bowl

Zewart was in the middle of an active Viet Cong Training area. We were there because there was a lot of VC activity on the trail leading into the Toilet Bowl. Just prior to coming out there the 3/506 had set up a series of ambushes and that’s how they found out it was a heavy area. They were able to capture a few prisoners.

When they shut Zewart down I was told to get on the first helicopter picking up a howitzer and head back to Betty with it, because I was scheduled to go out with the 3/506 infantry. I am on this Skycrane helicopter, the only passenger. We can’t pull the gun up because of something going wrong with the cable mechanism.

Sky crane lifting a howitzer the right way

We took off with quite a length of cable hanging under the chopper. The faster we went the more the cable started swinging, and it got pretty close to the tail boom. The loadmaster told the pilot to slow down because the cable was swinging so wildly. All of a sudden we heard a BOOM, and had to auto rotate down (an emergency landing procedure). The cable had hit something on the helicopter, probably the tail rotor.

Talk about protection, I mean we had jets out there and gun ships. They shot up the whole area around us. On the ground waiting to be extracted were a major, a warrant officer, a Spec 5 and me. Fortunately we were close to Betty.

January 7, 2015

Alex Taubinger – Forward Observer – Part One

ALEX TAUBINGER

Forward Observer

Part One

Lt. Taubinger

Early Career

Right out of high school my best friend and I took our girlfriends to a drive-in where the only movie showing was about Army jump school, and from that we both decided we wanted to be paratroopers. The next day we went down to the recruiting station and walked in and said we wanted to be paratroopers. We had walked into the Air Force recruiting office, and the recruiter just stared at us. Then this guy down at the other end of the hall waved and yelled at us, “Down here.”

Before we could move the Air Force recruiter said, “Hold it, we need typewriter repairmen.”

Our reaction was, “What?”

We went to see the Army recruiter and he said if we made it through jump school (paratrooper training) he’d buy us a steak. I got in but my buddy did not pass any of his written exams. He was dyslexic we found out. It was good they rejected him because he became a rock musician and got to be pretty famous out on the west coast where he made a lot of money.

I did basic training at Fort Ord, California, from there to Ft. Sill in Oklahoma for cannon-cocker school, and from there to jump school at Ft. Benning, Georgia. My first assignment was at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina with the 82nd Airborne Division.

The next year I came up on orders for Korea and went to Camp St. Barbara. (An artillery camp built at the end of the Korean War just south if the demilitarized zone, and named after the patron saint of artillery.) My most vivid memory of Korea is that our dress uniform was a heavy khaki wool that we wore in the winter, which made us stand out whenever we went to headquarters. They called us the boonie rats. The only other thing I remember is there was snow on the ground when I got there, and snow on the ground a year later when I left.

I went back to Ft. Bragg where I made E-6.

Military levels are denoted by rank, such as sergeant or captain, and a corresponding pay grade. Pay grades for enlisted personnel begin with an E, while pay grades for officers begin with an O. For example, E-6 denotes a staff sergeant, while O-3 is the pay grade of a captain.

From Bragg I went to drill sergeant school at Ft. Jackson, S. Carolina in one of the first classes the Army had. I was a drill sergeant for almost two years at Ft. Gordon, Georgia and during that time I pushed about 450 kids through basic training. It was the only job I had in the Army where I felt satisfied. You could see what you’d accomplished. You get all kinds of people, some are real losers and some are pretty sharp. Then after eight weeks of basic training they went from a kid to an adult. They were self-confident.

Three Drill Sergeant Stories

One of my training platoons included part of “McNamara’s 10,000.” (Initiated in 1966 by Robert McNamara to recruit soldiers below mental or medical standards in order to meet escalating manpower requirements. Over 320,000 came through the program.) They went into the prisons and got the petty criminals and drafted them into the Army. A lot of them could not read or write.

The company first sergeant (E-8 top dog) liked to fool the new troops as they came in. He had all the drill sergeants hide. In come the buses and all the kids get off. The first sergeant told these people, “We were not expecting you today. You are lucky all the drill sergeants are in town. If they knew we’ve got a new batch of recruits they would be might pissed off because we just graduated some a couple days ago and they expected a couple weeks of rest.” Right about then we started jumping out of the barracks screaming and hollering.

I got on a guy in the back row who stood there and wet his pants. I kept on him, “Get your feet together. Get you hands to your side, you’re at attention,” yelling the whole time. He ended up in my platoon as the trainee platoon leader. (Trainees were named to leadership roles that mimicked the formal chain of command.) I came into the barracks the next morning and every single bunk was as tight as could be. As I inspected he walked around with me bouncing quarters off each one of those beds.

I said, “Where’d you learn this?”

“Prison. My buddy and I here have been in and out of the system as long as we can remember.”

This guy who pee’d in his pants graduated number one in the class. He was the best marksman, the best everything. There was only one problem. We got a call a couple of days after he graduated from basic training that he and his friend were arrested on their way home to Philadelphia. They were robbing liquor stores and gas stations on the way home.

………………….

Then there was Sclafani. I can’t remember names very well, but I’ll never forget that one. He was a male secretary to a banker in New York. This guy was so weak he could not do a single pushup. We’d walk more than a block and he’d fall apart. He was not strong enough to pick up his M-1 rifle. I grabbed his arm one day and all I felt was bone. Of course we just kept pushing him and pushing him. That was our job. But he was hopeless.

One day I’m sitting on the commode, and you remember in the old barracks they were all out in the open. Sclafani runs in and kneels down in front of me and puts his head between my knees. A sergeant is right behind him and I ask what’s going on. He says, “I yelled at him and he broke down and ran off.”

Sclafani with his head down kept saying, “I can’t take it anymore.”

So we got the paperwork together and recommended that he be discharged. A psychiatrist decided that he had to be under 24 hour watch because he had suicidal tendencies. Guess who had to be his 24-hour-a-day companion? I was told by the company commander that Sclafani would move into my room with me in the barracks and that I had to watch him at all times. I did not vary my routine, and just had him follow me everywhere. That lasted for about a week. He was one of those people just not suited for the military, not the Army anyway.

…………………

One time I almost got shot in the face. We were out on the rifle range with the trainees in holes up to their chests behind sandbag walls. I notice one kid waving his rifle around. I went over and stood over him and yelled, “Soldier!” With that he snapped to attention, jammed the butt of the rifle down next to his feet, and as he did the gun discharged inches in front of my face. The bullet barely missed my helmet. That one shook me up.

Return to Ft. Campbell

I first went to Ft. Campbell, Kentucky to help set up a new basic training center there. I brought all of the Ft. Gordon lesson plans with me, rewrote them and put my name on them. I was there for just one training cycle, about two months.

I went up for promotion to E-7, but I did not have enough time in service. I’d been in only about six years, plus I did not have enough time in grade as an E-6. The battalion commander on the promotion board recommended I go to OCS (Officer Candidate School). My comment to him was, “I don’t think my leadership capabilities are there yet. I need to spend more time as a sergeant.” That did not go over too good with him. I think I also make a comment about a lot of officers lacking leadership ability.

Later my first sergeant convinced me that I should go. He said, “Look, it’s going to take you three or four years to make E-7 even if you’re number one on the list. You’d be a captain by then.” So I got out a copy of the pay scales and looked up the pay for an E-7 versus an O-3 with ten years in the Army. There was about a $300 dollar a month difference, big money in those days. That copy of the pay scale was my motivator while at OCS. I kept it in my helmet liner.

The precise difference was $667.20 per month for an O-3 versus $381.30 for an E-7, or 75% more.

I wanted infantry OCS at Ft. Benning, Georgia because you had to be infantry to go into Military Intelligence, which was my ultimate goal. Instead they sent me into artillery at Ft. Sill, because of my math test scores.

I kind of breezed through OCS. Based on my military experience they made me the trainee battalion XO (executive officer) which gave me separate quarters from the rest of the trainees. And a lot of the topics they taught I already knew, such as military justice and map reading, and all of which I taught for two years as a drill sergeant in basic training. The only exception was fire direction control and calling in artillery fire.

Out of OCS I went to the 6th Infantry Division back at Ft. Campbell. The only highlight in that assignment was that I had to brief top ranking personnel when Martin Luther King was assassinated. They were afraid of riots in Nashville, about 60 miles away. The majority of Ft. Campbell is located in Tennessee and we were the only military unit active in the state. We got the job of putting together a plan to “keep the peace” in Nashville, and because I had spent a little time in the Nashville area I got added to the team.

There was a big tactical review scheduled for two generals, the division commander and the post commander, along with their entire staffs. A major that was in charge of giving the presentation got laryngitis during the night. At about 5 in the morning he told me I had to give the presentation. We had a big map there and talked about such things as putting the headquarters at the Parthenon in the middle of the city. I did not know much about Nashville – I’d only been in the area a few months – but I was considered an expert because I knew more than anybody else.

When the 6th was de-activated they made me a company training officer in the same basic training battalion that I helped set up back when I was a drill sergeant. The company commander was brand new and the outfit was having problems. My colonel said to go down there and make sure things were being done right.

On my first or second day I was walking around – it was close to 100 degrees – and I saw the drill sergeants sitting under a tree sipping cold drinks while the troops were marching themselves on the tarmac – or trying to march themselves.

I go up to one of the sergeants and say, “What’s happening out here?”

He says, “Well sir, today is the trainees-train-themselves day.”

“Really?

He says, “Yes sir!”

I say, “Tell me, what lesson is this?” And he gives me the name and number of the lesson. I can’t today remember which lesson it was, but they were all ones I wrote and none of them involved trainees off by themselves with the drill sergeants lounging in the shade.

I get back to the office with the first sergeant and I am steamed. The first sergeant remembered me. He says, “Well you know what, you still got some of your old fatigue shirts?”

“Yeah.”

“You take the stripes off?”

I say, “Yeah, but they got these shadows where the stripes used to be.”

“Good! And you still got your Smokey the Bear hat?”

“Yeah.”

He says, “Wear that old fatigue shirt with the sergeant stripes shadow, and pin your drill sergeant badge back on along with your lieutenant bars. Hang your Smokey behind your desk or even wear it. We’re gonna have a meeting with those guys first thing in the morning before we wake up the troops.”

They all came into my office, the whole contingency, and their eyes snapped wide when they saw me. Usually officers sent to the basic training centers were either green out of OCS or ROTC graduates we called 90-day-wonders. But these guys knew right away I was a sergeant at one time … and a drill sergeant.

Straight off I said, “ I do not appreciate being lied to.”

One sergeant said, “What do you mean, being lied to?”

I said, “Here’s a copy of the lesson you were training yesterday. Look whose name is on the first page. Where does the plan say the trainees train themselves?”

Then I said, “You guys can either leave or we’re going to bring disciplinary action against you.

We got rid of four of them that very day.

Toward the end of that year after only a couple training cycles, I got orders for Vietnam. I’m married, I’ve got one kid and one on the way. Because I was an officer they would not defer me for the birth.

December 17, 2014

Richard Durant – First Sergeant

Cover 5 – Courtesy Dave Fitchpatrick

RICHARD DURANT

First Sergeant

The highest ranking sergeant in the battery

With few exceptions the people who served with First Sergeant Durant, officers and enlisted, insist he was the best First Sergeant in the history of B Battery. I talk to him by phone and from the start his warmth and instinctive feel for people comes through.

During his time as the ranking sergeant at LZ Sherry he lost seven boys killed in mortar attacks, mine explosions and a tragic firing mishap. He was there for the bloody summer of 1969, when the mortars fell almost constantly and wounded most of the boys there. He asks me if anymore were killed after he left, and I tell him of two more who died.

He talks less about the fighting, and more about personalities and the funny stuff. One story pulls forward another he thought he had forgotten. Throughout he calls the boys under his command “kids.”

First Sergeant Durant

Checking out a tank on Sherry’s perimeter

I put things out of my mind years ago and don’t talk about it. But about three years ago my daughter came into the room and said, “Captain Parker wants to talk to you.”

I said, “I don’t know any Captain Parker.”

“Well he knows you and would like to talk to you.”

So I got on the phone with him. He said, “This is Captain Parker.”

And I said, “I don’t know any Captain Parker.”

He said, “Damn it, I was your battery commander!”

I said, “Are you talking about Lieutenant Parker?”

He was a lieutenant when he was my battery commander and I couldn’t associate him as a captain.” He was my commanding officer until we could get a replacement after we lost the other commander.

I was 35 in Vietnam; I was grandpa. I’m what you call the old soldier.

I was first in the Air Force for ten years, as a bomb navigation mechanic on the B-47 and then on a Titan One missile launch crew. I was in four years and made staff sergeant, which in the Air Force that’s pretty good. So I reenlisted, and then spent another six years and never got promoted. I thought there’s got to be something else. So I got out of the Air Force and went to work for the Martin Company in Denver on the Titan One missile. After awhile the Air Force came back and got me. I was on the Titan One when Castro tried to go across our blockade. I was sitting there at that console. That was the highest state of readiness we were in since WWII.

So I went into the Army, I had two months of electronics and of all things they put me back in missiles, the Pershing missile system as a surveyor. Then I got promoted to first sergeant in artillery. If you can imagine that, being in survey and getting promoted in artillery. Then I ended up in Vietnam and I couldn’t tell you which end of a howitzer a bullet came out of. And here I am an artillery first sergeant. I thought, Boy oh boy.

Listening Skills

I ask how he adjusted to the job not knowing anything about artillery.

So I learned a lot at Sherry … tell me about it!

I asked questions. When I got there we got mortared all the time, every third night, and you were out there every night with the guns firing perimeter defense. You just sit there and you talk to the guys. This is how you cut powder charges: charge 7 you leave all seven bags in the canister. Shooting a charge five, you cut two off. And you sit and you listen. This is fuse quick, this is air burst. You listen and pretty soon you got a pretty good damn idea of what’s going on. What type rounds they’re shooting and how they’re doing it and all that.

I was fortunate, I never had any young officers come in and start giving orders. I’m glad for their sake. Nobody ever did that. You know, we were there to protect one another. If you didn’t work together at Sherry, you weren’t there too damn long.

They always sent the duds and shit and the trouble makers to Sherry. If they were doing drugs and that, they sent them to Sherry. I just happened to be in the rear area at Phan Rang and one son of a bitch lobbed a fuckin’ M79 grenade in our hooch, into the senior hooch. (It did not go off.) We chased the bastard down, and two days later I’m back at the firebase, and guess who comes in? The same kid, and he already had the name Frag. (Andy Kach had given him the name minutes before on the chopper pad.)

We had a little talk and I said, “Let me tell you something, little man. You can frag my ass, but if you do, (points around) this guy’s gonna kill ya, and this guy’s gonna kill ya, and this guy’s gonna kill ya, because we all look out for one another. You got your fuckin’ choice. You can straighten out and be a soldier, and do what you are supposed to do, and cooperate and graduate, and you’ll be all right. You fuck up and you’re gonna get shot.” That’s all there was to it. That was ol’ Frag. And you know, he turned out to be a good soldier.

Then we had another kid come out from the rear who was dealing drugs. He was one that didn’t listen. He lasted one day. During a mortar attack, he’s running around outside with nothing on, no helmet, no flack jacket, lookin’ at all the explosions. He looked too long, because one of them got him. It just about blew his brains out. Took the top of his head off. We Medevac’d him. He’ll never be anything but a vegetable.

Mess Sergeant

His name was John J. Cunnane, a single guy from Germany. When he got to Sherry, I don’t think John had ever been in the sun, he was as white as the fallen snow. And then you put him in them camouflage shorts, and them combat boots, and that helmet and flack jacket. We’re under attack, and you see John running around with that pistol hanging half way down to his ankles. It was the funniest sight in the world. He looked like a snow man in camouflage.

When I got to Sherry we had a lot of ham, to where you got sick of it. I asked him why that was and he said because it didn’t spoil. Because we didn’t gave any refrigeration we had to eat perishables right away and ham was the only meat that kept. “You get me a reefer,” he said, “and we’ll eat a lot better.” I still had a lot of contacts in the Air Force back in Phan Rang who I did a lot of transferring back and forth with, if you know what I mean. I’ll give you this if you give me that. So we got a reefer for the mess sergeant and pretty soon we had steaks and burgers, and we even had ice cream for the kids. I’m proud of that.

We got hit one night, and I ran to the mess sergeant’s hooch to see where he was – everybody checked on everybody else at Sherry – I opened the door and see blood all over everything and he wasn’t there. It panicked the hell out of me. So I’m out looking for him, and I hear him screaming down at the end of the mess hall. He’s got the KPs chewing gum to plug holes in his water cans from shrapnel.

What I thought was blood in his hooch was ketchup. Ketchup was hard to get and he was storing it in his hooch lined it up along the wall. A mortar round landed right beside his hooch, the blast went through the little window and busted up all the ketchup. Then I come in thinking it’s blood. Of course afterward I laughed.

Mine Sweeping

When I got there Commo section was in charge of sweeping for mines. When we lost the two kids, (Percy Gulley and Steve Sherlock) I was still back in the rear. But shortly thereafter I was sent to Sherry. The commo section was a little leery, which you could understand. So I said, I don’t think that’s fair, we’re all going to learn how to sweep for fuckin’ mines. I had a class, and I taught all the section chiefs how to sweep for mines. The battery commander would go sweep for mines; I would sweep for mines; The XO would sweep for mines; and we switched off. We all would go out and sweep for mines, which I thought was a lot better deal. When you had your XO sweeping for mines, and the company commander sweeping, it boosted morale. It gave the commo section a break. And the guys accepted it, that was the main thing.

For The Kids

First Sergeant Durant was always looking to make things a little better for his kids.

When anybody came from the rear you were supposed to be in your jacket with your helmet, with your flack jacket laying there with your weapon and gas mask. When I got there I thought, this is ridiculous. Out there in that hot sun with them jackets and fatigues. I said, “You don’t have to wear that, you can go in your tee shirt, you don’t need to wear your helmet in the daytime, but it should be laying there with your flack jacket. But let me tell you something. Anytime anybody sees a chopper coming in here, they better be in proper uniform.” I tell you, it worked great. Whenever anybody come in, we all had our shirts and helmets on. Then when they left everybody took everything off.

I also made Sunday a stand down. Breakfast was late, from eight o’clock to 11. The only people who had to do anything on Sunday, the ammo section would resupply the guns, the gun crews would be on standby, and Lt. Clark would lay the battery in the morning (set the precise orientation of the howitzers). In the afternoon the mess sergeant would barbeque hot dogs and hamburgers. If we were lucky enough to scrounge steaks from the Air Force or Navy, we’d had steaks and beer, and the kids played volleyball. We got away from the war for a day anyway.

Gas Attack

It came in at night. The tower out by the dump sighted something and they started shooting in that direction. After that there was a big explosion maybe 80 yards off that tower. Now everybody’s up. Next thing we heard from the tower was, “GAS.” At night everybody wore (carried) their gas masks on their hip. When you heard “GAS” you put your mask on, and you laid down and you watched to see if somebody was going to try to come in behind that. You waited for a star cluster. If a white one went off, that meant dicks in the wire. If a green went off, that meant they were insider our perimeter. Everybody was supposed to drop down, nobody was supposed to move and anybody that was moving, you shot them. The red star meant we were shooting a beehive. The direction the red star was going meant the direction the beehive was going. It’s coming our way, so get down and watch your ass.

We waited for someone to come in behind the gas, but they never did. We had mortars that night, couple rounds but nothing great, and no ground attack. But you just never knew.

The next morning we went to find out where they had blown the CS gas (military grade tear gas). They had also planted a mine out there and we’re tromping around the area. Luckily the fire from the gas explosion had burnt the trip wire to the mine, and we just blew it in place.

I’m trying to remember the funny stuff. I guess the gas attack was funny because nothing happened afterward.

Chickenman

Every night we would wait for Chickenman to come on the radio. All the guys would have their radios on and then you’d hear, “And now, the exciting adventures of CHICKENMAN.”

Double click below and see if these don’t bring back memories.

How Chickenman Came To Be:

http://seveninajeep.com/oped/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/How-Chickenman-Came-To-Be1.mp3

The Chicken Missile, something we could have used at Sherry.

http://seveninajeep.com/oped/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Chicken-Missile1.mp3

For all the Chickenman episodes go to: http://www.radioechoes.com/chicken-man#.VGjxXodStih

Shopping Trips

You know, we never got a lot of things at Sherry. If we needed a generator, we could never get one. But when we’d run a convoy, we always went in with trucks to get ammo and water. Everybody would say, “Look, get me this, or get me that, and bring it back.” On one trip one of our guys stole a 50 caliber machine gun. (It was not on the shopping list. Tommy Mulvihill saw it unattended and simply loaded it on his truck, thinking you can always use another 50 cal.)

Guess who was out to see us the next day? CID (Criminal Investigation Command).

“They said, “Did you guys take a 50 caliber machine gun?”

We said, “Oh no, we would never do anything like that.”

“Right. Where’s it at?”

“Well, it’s over here. You can have it back. Don’t know how it got here. It dropped in I guess.”

But that’s how we got a lot of our supplies.

The Well That Wasn’t

I remember when we dug a well there, or tried to dig a well. That was a big joke, funnier’n hell. We got a drill right there beside the old mess sergeant’s hooch. We drilled down and hit some water, and I got me a pump from the Air Force, put that pump down in the ground there and that son of a bitch pumped up about two minutes worth of water.

Two minute pump

Paul Dunne

I went out every night and sat with each gun crew and bullshit with them, or reassure them, or whatever you had to do. You might fire some perimeter fire with them. Then you’d move onto the next gun, and bullshit with them. But I did not want to get too close. What I mean is, those were all my kids. I did not want to know that you’re married and are going to see your wife next month. Because if you weren’t there tomorrow, that really bothered me.

I had a kid do that. I never got tight with any of them except my driver. Paul Dunne. I’d go out at night, and he’d be in a tower and we’d sit and he’d talk. He’d say, In December I’m going in to see my girl in Hawaii and we’re gonna get married. And my dad’s a preacher.

We were due to run a convoy, and I was running it. Paul had the jeep all fixed up and ready to go: radios, weapons and everything. Commo section came over and said, “Hey look, can we run the convoy. Guys want to go in and get this and do that. Rather than you run it, let us run the convoy.”

I said, “OK. I guess you can go ahead and run it.” So I told Paul I said, “Go take all that shit back off the jeep because Commo’s running the convoy.”

He said, “Look First Sergeant, I’m all loaded up, I’ve got everything set. Why don’t I just run with them today.”

I said, “Well, if you want to.”

He got killed that day. They hit that mine and it killed him and wounded some other guys. And that really, really bothered me. So I knew the guys, but I didn’t want to know your personal life. It’s harder when you do that.

Snipes

When I went to Washington with Hank Parker and Andy Kach and Jim Kustes, and we’re talking and Parker said, “You know what I remember about you?”

“No, I sure don’t.”

He said, “You remember when you used to come around and talk to us at night??

“Yeah, I remember. I used to talk to all the gun crews.”

“Remember when you told me about the snipes? When you were a kid you used to go snipe hunting. That’s what I remember. But I still don’t understand them snipes.”

December 10, 2014

Willie J. Ridgeway – Battery Commander – Part Two

Cover 4

WILLIE J. RIDGEWAY

Battery Commander

Part Two

Flight School

Immediately after Vietnam Willie took a giant step closer to his beloved helicopters when he entered the first phase of flight school at Ft. Stewart in Georgia. The second phase of flight school took him to Ft. Rucker in Alabama, where he continued his training and earned his wings.

His flight school classmates remember a cool headed and seasoned Vietnam veteran.

Dan Oates flew O-1 Bird Dogs in Vietnam, a single engine reconnaissance plane with pilot and passenger seats front and back. Today he works at a Christian ministry focused on combat veterans with post traumatic stress.

Willy was older than most of us and therefore, assumed a little bit of an older brother role. I remember Inga and their daughters and how much he seemed to enjoy the parties that we had in flight school. It was a carefree time and we all knew what was in front of us. Since Willie and a couple of the other guys were combat veterans, their insight was helpful in preparing us for combat.

We did ground school together and we attended social gatherings. He was always under control. As I sit here I can see him with that confident look and his gray flight suit and red hat (We were the Red Hats). Each class had its own color hat to represent the class.

Captain Ridgeway center with Red Hat class

Jerry DiGrezio flew O-1 Bird Dogs in Vietnam and over the course of his career qualified in six aircraft. After seven years on active duty and 23 in the active reserves he retired a full colonel.

We were all pretty close in flight school. I remember Willie as a very good guy, a little older than the rest of us. He was 29 years old, while most of the guys going through flight school were 23/24. He was an old man.

He was a very cool character. When we were getting ready to graduate we were flying the Birddogs without instructors. I was flying the aircraft and he was in the back seat. I was landing at Cairns Field at Ft. Rucker. The Bird Dog had very springy landing gear, if you landed too hard it would spring you back up into the air. And when I came in I made a horrible, horrible landing and it bounced back up into the air. Willie never said a word. I would have freaked out if someone had done that to me.

Ed Cattron graduated from West Point and like Willie had a tour in Vietnam before flight school. On that tour he earned a Silver Star for his actions defending a tiny firebase of less than 100 troops, LZ Peanuts up near Khe Sahn, against a 14 hour onslaught of over 500 North Vietnamese regulars.

Willie met his wife Inga in Germany, and by the time we were in flight school they had the two girls. Peggy and Debbie. Willie and I shared a love of flying and both had a tour in Vietnam before flight school. We trained in a single engine aircraft called the T-41.

Willie was so quiet, and very intense. He told me a lot of stories about the supply depot in Vietnam (having been a supply sergeant in Germany) and about “combat losses.” There was a policy about flight sunglasses. You could only get them replaced if the lens was broken. Someone came in looking for a new pair due to a chip on the edge. The supply personnel told him he could not get a new pair unless the lens was broken – chipped did not qualify. So the guy broke the lens on the corner of the counter and said, “OK, now it’s broken.” Stories like that.

Back To Vietnam

Willie got his wings at Ft. Rucker in September of 1969. The Army’s helicopter school was also at Ft. Rucker. Instead of taking an assignment Willie was able to remain there and finally, finally transition to helicopters. Three months later on December 31 he reported for duty in Vietnam to the 219th Aviation Reconnaissance Company known as The Headhunters. There he was assigned to fly not helicopters but the O-1 Bird Dog reconnaissance airplane. Any veteran will tell you the Army put you where they needed you, not where you wanted to go.

O-1 Bird Dog on duty

The unit history of the 219th tells the rest of Willie’s story.

In March (1970) Captain Slimowitz was called to company headquarters in Pleiku to assume the duties of operations officer. Captain Slimowitz’s replacement as platoon leader was Captain Willie J. Ridgeway, a second tour aviator who was newly arrived in Vietnam.

The serene winter experienced by the aviators of the second platoon in Kontum erupted violently in the spring when on 1 April, the infamous battle of Dak Seang erupted. The first aircraft on the scene that morning was a birddog piloted by HEADHUNTER Gary P. Lowery, and during the ensuing days while the battle for the besieged strategic border camp raged, there were few moments of the daylight hours when a HEADHUNTER of the 2nd platoon was not nearby overhead directing airstrikes, and giving valuable visual reconnaissance information to the ground troops in the area. Before this fierce enemy attack was repulsed, there were many casualties taken by the allied defenders of the camp, and unfortunately the HEADHUNTERS were not spared. On 3 April, Captain Ridgeway was killed in an accident as he was returning to Dak Seang from Kontum to continue aviation support.

There is only speculation around the cause of the crash. The only known fact is that the crash occurred on takeoff after multiple runs to support the troops still under siege.

Ed Cattron

My wife discovered he had died through a Red Hat newsletter. She kept in touch with Inga for a while. I was back in Vietnam for my second tour when the accident happened. I heard about it from my wife when she got the letter from Inga.

I found out details of it years later when my Red Hat class got together for a reunion. Some units had been in contact and there was pretty intense fighting on the day he died. He flew several missions during that day. Towards the end of the day he had come back, refueled and decided to go out once again to do artillery spotting. On take off the aircraft just went straight up in the air and straight down. There was speculation that the seat had slipped back – there were occasional reports of seats that would slip – and if you were holding onto the controls you’d pull back on the elevator and the plane would go straight up in the air. Either that or he was exhausted and passed out. There was no direct enemy action. I saw pilots over there flying well in excess of anything the FAA would allow today.

There is no explanation for why he transitioned to helicopters and then in Vietnam ended up in a fixed wing Bird Dog. Either he did not make it through helicopter training (a very different type of flying with different physical demands), or the Army simply had an opening in the Bird Dog and put him there.

Willard Long

The way I found out he had gotten killed, about four years ago, my daughter was working in Washington, DC. She said, “Dad go with me,” and we rode the train up there. While she was working I wandered over to the Vietnam Memorial. There was a gentleman there and I asked him could he possibly see if there was a Willie Ridgeway there. He just flipped open the directory and said, “We got a Captain Willie Ridgeway.” I went home and found the unit history report of the accident and an obituary picture and I knew then that it was him.

Peggy Ridgeway Musgrove – Willie and Inga’s oldest daughter

My mother always told he loved life and mom said she was glad that he lived it to the fullest. He was always doing stuff like surfing, scuba diving when we lived in Hawaii (we were there for 3 years). And she said he loved to fly and play baseball.

I was born in Germany. He chose my name and he was there for my birth and my first year, then he was sent to flight school where he was when my sister was born, he could not come home for her birth because he was taking a test (which Mom said he failed). He did not get to see my sister for the first time until she was three months old.

I was five when he died but I still remember the day they came to the door to tell us he had died.

I remember my Mom telling me the only way she could identity my father’s body was because he had smashed his finger the last time he was on leave. On that leave before he left he had my mother promise that if anything had happened to him that my sister and I would get an American education.

The last known photo of Willie was taken just weeks before he died. It captures the man everyone describes as resolute and unflappable.

March 1970 at headquarters compound in Kontum

Courtesy Scott Boyd

This is the look Jim Gacek must have seen two years earlier the night LZ Sherry prepared for a North Vietnamese Army ground attack.

It was during the monsoon season and pouring rain every evening. Intel came down that up to a battalion of NVA were headed our way and an attack may be imminent, as we were in the line of defense for LZ Betty and Phan Thiet. Captain Ridgeway came to my FDC bunker and along with the other officers and sergeants laid out the defensive plan for the night. It was tense.

I could see it written all over his face … this was serious shit. After everyone got their orders, he turned to me, looked me dead in the eye and said, “Gacek, you’ve got the telephone lines to the perimeter. When they (the NVA) hit the wire I want you to fire this white star cluster …. and if and when they break it, you fire the red one.” (Red meant beehive round on the way, take cover and shoot whatever moves.) My shit went weak.

We never did get hit, but I’ll never forget that look on his face. He was all business that night .

Willie J. Ridgeway fell a whisper short of his dream of piloting helicopters, yet in the end gave all he had to give. B Battery 5/27th Field Artillery is proud to place him among its fallen heroes.

December 3, 2014

Willie J. Ridgeway – Battery Commander – Part One

Cover 3

Joe Mullins on left, Newhouse on right

Picture courtesy Joe Mullins

WILLIE J. RIDGEWAY

Battery Commander

Part One

First Lieutenant Ridgeway, two months after his arrival in Vietnam in September of 1967, served as the Executive Officer of B Battery, second in command under Captain George Moses. He proved to be bright and hardworking; and at 27 years of age was an unusually mature lieutenant. These qualities soon earned him a nomination to interview for a position on the staff of General Blanchard, which did not materialize, but did take him to several assignments at battalion headquarters. Ridgeway was promoted to captain and returned to B Battery to succeed Captain Moses as battery commander when it moved to LZ Sherry in May of 1968. Those early months at Sherry were tense but relatively calm as the battery built up its position. Ridgeway earned the reputation as “a good guy and a good battery commander.

Even tempered men like Captain Ridgeway, who do their jobs with little fanfare and even less drama, leave behind few stories and are simply remembered as one of the good ones. It is the curse of quiet competence.

If that were all there was to Willie J. Ridgeway this would be the end of the story. However there is a great deal more to this man. Here is … in the tradition of Paul Harvey … the rest of the story.

The Young Willie

Willie was 16 years old when he enlisted in the Army, so young his parents had to give their permission. He was an enlisted man for nine years before going to Officer Candidate School. During that time he did tours in Korea and Germany as a supply specialist and eventually worked his way to staff sergeant.

Following an early tour in Korea, Willie returned to Ft. Campbell, Kentucky where he fell into a close friendship with Willard Long. Willard has vivid memories of their time together.

I had a real good friend in Willie Ridgeway. When I first met Willie he was a Spec 4 and he had just come back from Korea. We were 18/19 years old. We was together about ten months.

Early photo of Willie

We were attached to the 101st Airborne Division and Westmoreland was our post commander. He worked in supply in the 21st ordnance company at Ft. Campbell. I was in small arms so I did a lot with supply, and that’s how we met.

I was kind of a standoffish type person. I didn’t quickly make friends with no one. Me and him just kind of hit it off. After you find out that he’s clean living and be around him for a couple weeks, we just kind of migrated together. He was an exceptional person in that he was clean living and he was nice to everyone. I never saw him smoke a cigarette, drink a beer or say a cuss word. He carried a camera with him just about everywhere he went.

When he come out of Korea he bought him a brand new red ‘60 model Ford one weekend back home in Mobile and drove it to Ft. Campbell. Me and Willie had a lot of fun together. We went a lot of places – Nashville to the Grand Ol’ Opry and we went to Kentucky Lake a lot about 30 miles from Ft. Campbell. We would go there on weekends and swim and chase the girls. When you went off with him you never did have to worry about alcohol and he was always a gentleman.

He would go home, back and forth to Mobile a lot. On one trip he picked up a paratrooper in Alabama right outside of Mobile. The man had on his uniform of the 101st and he had a cast on his foot. Willie knew where he was going and could take him right to his door, right to his barracks. But the man had done figured out he was going to steal Willie’s camera and didn’t want Willie to take him to his barracks. Willie didn’t think anything about it and let him out somewheres on post.

At the time I was doing inspections on the 101st rifles. Our ordnance team was going through the whole 101st airborne division. Two days after Willie’s camera got stolen I got to talking to someone and asked him if a man from Mobile with a cast on his foot was in their unit. He said, “Yeah.”

I said, “Just check to see if he signed out on liberty this weekend, when he signed out, and when he signed back in.” I told him I got a good friend that could have possibly picked him up and this guy stole his camera.

The guy had signed out, so they got him and opened his wall locker and there was Willie’s camera. Out of 120,000 paratroopers on that post the Lord led me right to Willie’s camera.

We went back over to their morning formation the next day and that man had to give Willie his camera back in front of his whole company. They called him out of formation. The First Sergeant had the camera and he give it to the soldier that stole it. Willie walked up in his military way, cut his corners, went right up there and the boy handed him his camera back. Willie about-faced and was out of there.

Willie loved the Army. I never could understand it, why he loved the Army so much. He went in so young he had to get his parents permission, and I did too. I went in at 17. I went into the Army to get a pair of shoes and something to eat. It was a good opportunity. It changed me tremendously. I went to bed at 17 and got up in the morning at 25. It gave me a second chance at education.

Willie always wanted to fly. He went a whole winter and he got him a book somewheres on helicopters. He just laid in his bunk and studied all winter on how to fly a helicopter. His ETS (estimated termination of service) was coming up, but he knew he was going to re-enlist and he wanted to go to Ft. Rucker Alabama and go to helicopter school.

B Battery Commander

Willie would eventually make it to helicopter school, but not for another 11 years. After seven years as an enlisted man he went to Officer Candidate School at Ft. Sill Oklahoma. Two years later he went to Vietnam as an artillery 1st lieutenant, serving in succession as Executive Officer of B Battery, battalion staff officer, and then B Battery commander when it moved to LZ Sherry in May of 1968.

Captain George Moses remembers a green but bright 1st lieutenant.

When Lieutenant Ridgeway came out to B Battery as my XO I commented in a letter home that he didn’t know much about 105 mm howitzers. But he was a quick study and became an extraordinarily capable XO. He had to be for us to perform as we did in the Christmas action supporting the 173rd Infantry near Dong Tre, the largest of my tour in Vietnam, the tricky shooting mission at Qui Nhon Bay, our march down to Phan Thiet and defense of that location during Tet of ’68. We were up and down the coast during that period, often splitting the battery into multiple operations.

Ridgeway was nominated to be aid decamp to General Blanchard at First Field Forces, and I encouraged him to consider the job. He remained with us, but I remember him being gone from the battery on battalion business and even taking an assignment there before replacing me as battery commander. He came back to the battery as a captain, promoted well before the usual timetable for captain.

One soldier remembers Ridgeway as a by-the-book officer, who loved to take pictures and carried his camera everywhere.

I remember when LZ Betty got hit one night all we could do was watch the orange and red flames shoot up in the night sky. He was out taking pictures of LZ Betty blowing up. He had a more sophisticated camera than mine and I said, “Are you going to get anything on that.”

He said, “Oh, yeah. I’ve got capability to capture this on film.”

I remember a B-52 strike taking place up the hill from us. He knew they were coming and told us about it. We were out there waiting, and all of a sudden it looked like a power company right-of-way being mowed up the side of the hill. It was amazing. I did not have my camera but Ridgeway got it all I think.

Another, James Gacek, says,

I served with Captain Ridgeway at LZ Judy, and when we moved east to LZ Sherry. I was in charge of FDC (Fire Direction Control – controlled radio communications, travel in and out of the battery and fire missions). I can offer that Captain Ridgeway had a sense of humor and played a mean game of Pinochle. It’s the little things I remember… his gregarious smile … his love for photography … our conversations about the war and what we would do after.

Four things stand out in my memory.

I made the mistake of leaving my dog tags in Qui Nhon. The captain one day gave an order that everybody had to “present dog tags at the evening meal or you wouldn’t eat.” I had been drinking beer all day and from my hooch yelled across to the mess tent that I guess I was going starve. When he heard that he said, ”Sounds like he’s drunk. Go get him and make sure he gets something to eat.”

The battery was split with half the guns at Sherry and half on a mobile operation just west of our base camp at Phan Thiet. My R&R was coming up, just three days away, hence I was chomping at the bit to get to get out to Phan Thiet where I’d catch a plane to Cam Ranh Airbase and then on to Hong Kong. Since my FDC unit had all the communications I knew I couldn’t get a chopper out of Sherry. After much cajoling Captain Ridgeway agreed to allow me take his jeep to Phan Thiet, but only if I took a load of food for our mobile operation near there.

Before this he had afforded me a real privilege. He had expedited my promotion to Specialist 4 (equal in pay grade to a corporal) at the earliest eligibility, and coinciding with my going on R&R.

Then there was the ultimate privilege. When I was due to leave Sherry for home he allowed me to call my own chopper to pick me up, along with Chuck Burly, to fly us to Phan Rang, the first leg of the trip back to the States.

Captain Ridgeway was a fine officer … and man.

November 19, 2014

Hank Parker – Battery Commander – Part Ten

Cover 2

HANK PARKER

Part Ten

Skeleton Crew

After the departure of our captain the night of the August 12 attacks, I take over as battery commander. I am still a first lieutenant, but four weeks later move up to captain. During that period the battalion commander comes out to Sherry to give me a Purple Heart for wounds I got at LZ Betty seven months earlier.

Now we are dangerously shorthanded at LZ Sherry. Two guns and their crews are still out at Outpost Nora. We lost another gun and ten men on August 12. That on top of the losses from the pounding we’d taken during July and early August. So out of a full strength battery of six guns and 120 guys, we’re down to three guns and 67 guys at Sherry. A full gun crew is eight guys, and we are struggling to find four for a gun. We have to suspend R&Rs, and I can’t send guys back to Betty who are not badly injured. Can you imagine when you’ve got that few men and you have to run a convoy? That’s leaving the battery really vulnerable. Fortunate for us the enemy never wanted to make a daytime attack.

Replacements are coming in, but they know nothing about artillery. That’s when I start to train cooks, motor pool technicians, fire direction people, and even the radar guys on how to handle a howitzer, especially direct fire with beehive (tube lowered to level and loaded with a fleshette round). I fully expect we were going to have to use them against a ground attack. I move a howitzer to the perimeter where we can practice. We have contests sighting directly through the bore of the tube to hit a target, and on one occasion a cook wins.

I am nervous and wound tight. When the sun sets I start moving the Duster 40 mm cannons and Quad 50 machine guns because I know that gives the enemy pause. They’re not going to come in under a Quad 50, or even a Duster. The crews get ticked at me over moving every night because they like to settle down in their little hooches. I say, “Hey, this is for your protection too.”

In the middle of the day I see a group of Vietnamese men and women out in the rice paddies digging like it is a burial. I suspect it’s not, so I lower a howitzer, bore site it, put a round in and I fired right over their heads. The shell explodes maybe a hundred yards behind them. The message was you can’t do that in the daytime, and if you do it at night I’m going to put the round on top of you. The province chief raises hell with my superiors at Betty because we are under orders not to fire at anyone unless first fired at. I get a call, “You don’t do that.”

I say, “I will do that. My job is to protect my battery.” Had shrapnel hit them I probably would have gone to jail.

Always, always I stress with the guys how vulnerable we are. A little example, we take our laundry into Phan Thiet to Liz, a beautiful French-Vietnamese woman in a purple dress. I know she takes note of the names on the uniforms and that information is passed on. Only a few guys don’t want to pay the extra few bucks and do their own laundry. I tell the guys the enemy knows exactly how many people we have and they know us by name. Remember the Viet Cong own this area. We got to be sharp.

August 28

Again an accurate mortar attack. The first round hits the trail of Gun 5, knocking out the gun and causing casualties. Andy Kach is with PFC Rodriquez in the guard tower returning fire when a mortar hits on the sandbags in the tower and blows both of them to the ground, maybe 20 feet below. Rodriguez is blinded by the sand, which is not unusual. Guys would be peppered when the mortar exploded in the ground, and that can be a serious injury. I know for Rodriquez it is. He takes it full in the face and now is buried under a pile of sandbags. Andy brings Rodriquez to the medic and then returns to the tower. He digs out the M60 machine gun and continues to lay down a base of fire. That is an individual act of valor because now if the enemy are going to get in they have to deal with his machine gun.

That is when I say to Doc, “Can he still manage a gun?”

Doc says, “I think so.”

I ask Andy, “Can you go back to duty?”

He says, “Yes sir, I can do it.”

I do not realize the significance of his injuries because they are not visible. They are in his jaw and teeth. In a day or two his jaw is swollen and he can’t eat, so I send him back to Phan Thiet, and then to Phan Rang for treatment.

Andy and the guy hurt on Gun 5 eventually come back to the battery, but Rodriguez goes to the states for treatment and never returns. For now we’re down another three guys. Soon after we have another attack that wounds Judson, our barber, and we send him to the rear. We’re down to half strength and under constant attack, but I love this little firebase. I am a captain now and assume I can continue as battery commander. Let me keep the battery, I am feeling. But that’s not the Army’s way.

USS Boston

Two weeks after I am made captain they send me to the battalion Tactical Operations Center at Betty. I clear grids and coordinate the fire of seven artillery batteries, standard fare for that job. But I am also put on orders as an aerial observer (AO – does reconnaissance and calls in artillery fire – a dangerous job). I have survived the war so far; I’ve been a forward observer out with two infantry battalions, I’ve been a battery commander, I’ve done my duty. Normally you don’t need official orders to be an AO, you just go out and do it. But this is for a specific mission to fire the USS Boston, a heavy Naval cruiser. The mission is going to take place in a week and I’ve only got 30 days to do, I’m short. I say, “No I am not going to be an AO. Let Lieutenant Bud Domagata do it. He’s our AO. Hell, I’m a captain now!” They want me because I had walked the target area as an forward observer and they want the AO to be someone who knows the area and can adjust fire.

They fly me out to the USS Boston in a little helicopter.

USS Boston taken on my ride out

Titty Mountain in the background off her stern

I’m in my jungle fatigues and I’ve got my maps and compass and grease pencil. As I set foot on deck they salute me and say, “Good morning, lieutenant.” I think, can’t these guys see I’ve got captain’s bars? (In the Navy a lieutenant is of equal rank to an Army and Air Force captain.) They take me to the mess hall where I have breakfast with the commander. There is crystal and china, and you have Filipino waiters in little white jackets serving coffee. I’m thinking, What is this?

After breakfast we go to the war room, and I’ve never seen so much rank in my life, so many stars on uniforms. I get out my grease pencil and my map covered in plastic. The commander says, “No lieutenant, here.” An enormous map drops down from the ceiling, the biggest I’ve ever seen, and he hands me a pointer. I show him the target grids and what we’re going to do. He says, “You’re going to be the spotter, right?”

“Apparently I am, sir.” I did not tell him that I did a little aerial reconnaissance in Hawaii, but I had never called in live fire from the air in Vietnam, much less from a naval cruiser. In fact I had never even been up in an airplane in Vietnam, always helicopters.

We fly over the area and I cannot believe it. This is a major NVA staging area. It looks like ants swarming around trucks and ammo dumps. Trail heads are fortified with heavy weapons and probably mined. I call in the first salvo and when it fires I think the ship has blown up. I mean it’s her six eight-inch guns all firing at the same time, making a ball of fire so big you can’t see the ship. The pilot says, “Holy shit.” This is his first time too doing this kind of thing. I think I feel the plane move as the rounds go by us. It scares the beejeesus out of me. I say over the headset to the pilot, “We better go higher.” Which we do, while I reach for my rosary.

The rounds are on target. I see secondary explosions, ammo blowing, petrol burning. We blow the shit out of all of it. I have never been directly over my target like that. The term awesome is used too often, but to see this is indeed AWESOME. Her call sign is Mauler, and now I know why.

Back on ship I say to the skipper, “Sir, is there anything else I can do for you?”

He says, “Yes lieutenant, there is. Can you possibly get me an AK-47?”

“Yes sir, I can get you an AK.” I go back to Betty and arrange for my AK-47 to get sent to the Boston.

Later I am back on the ship and the skipper says, “Now can I do anything for you?”

“Yes sir, you can. Have you got any steaks?”

He says, “We got a lot of steaks, lieutenant. How many you need?”

I say, “How many have you got?”

He says, “This is our last mission and we’re going back to the States. I can empty my meat lockers for you.” I bring enough steaks back to feed the guys at Betty, Sherry, I think even Sandy.

In Conclusion

Medals

I leave Vietnam with a Purple Heart, the only medal from my tour. I know Colonel Crosby (battalion commander) told me he was putting me in for a Silver Star, and Captain Wrazen said he was putting me in for a Bronze Star. But when it doesn’t happen, it doesn’t happen. I’m OK; they did their best.

I go to Ft. Sill where I am an artillery instructor. I come in in from a field maneuver and they say, “There’s an awards ceremony at noon. Come to it.” The person getting the medal ends up being me. I get a Bronze Star with V Device for Valor. Then more medals dribble in. I get another Bronze Star with V Device, but I cannot wear it on my uniform or the first one either, because the Army has to issue another medal with an oak leaf cluster on the ribbon indicating two medals. Then I get another Bronze Star, and have to do it all over again, but this time get a medal with two oak leaf clusters on the ribbon. So I’ve got five Bronze Star Medals laying around, but the only one that counts and the only one I can wear is the one with the V Device for Valor and two oak leaf clusters. Personnel is in a tizzy straightening out the flurry of new orders this entails (paperwork accompanying the medal and authorizing the medal).

I get two Army Commendation Medals. Same drill: can’t wear either medal, have to get a third with the oak leaf cluster and Correction DD 215s. I get another Purple Heart medal because the one I got at LZ Sherry was given to me without the orders, and now they have to give it to me again, this time with the paperwork. By now Personnel hates me, and it’s getting a little embarrassing for me too.