Ed Gaydos's Blog, page 13

October 29, 2014

Captain Hank Parker – Battery Commander – Part Seven

Hank Parker

PART SEVEN

Richard Durant – First Sergeant

(highest ranking sergeant in the battery)

Pretty soon a new first sergeant comes in, Richard Durant. He’s an older guy, maybe 35, who came into the Army from the Air Force. Early on he says to me, “Lieutenant, come on over to my hooch.” He’s got a six pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon, so already I know I like him. And he’s got ice! Where in the world did he get ice?

He says “Let’s have a talk.” He’s asking me all kinds of questions about the strengths of the battery, the weaknesses, what do you need, how things work at Sherry, what can I do for you as First Sergeant, what’s going on with personnel. He says, “It seems like the guys are kind of down.”

I say, “Yeah, it’s been tough out here.”

“Let’s have a couple beers and we’re going to discuss it. We pop two beers and he pulls out this field manual on land mine detecting. He has a mine detector there in his hooch and we fool around with it a little. When the six pack is dead he says, “Let’s go bury these cans.”

I say, “We don’t have to bury the cans, Top, we can just throw them in the trash.”

“No, no. We’re going to bury these cans.” Then it dawns on me what he’s up to. So we bury the cans and go back to his hooch for a few more beers. Then he says, “OK, let’s go find those cans.” In that way we learned how to operate the mine detector, reading the manual for proper procedure and practicing with it.

The next morning bright and early he grabs me and says, “Hey, XO, let’s go.”

I say, “Go where?”

“We’re gonna clear the road.”

“What? I’m not clearing no road.”

He says, “Hey, we learned how to operate this mine detector. Let’s show the men we know how to use it.”

“Are you nuts?”

He says, “Lieutenant, you got to lead. You don’t tell men what to do, you show ‘em. You teach ‘em.”

“OK, Top.”

Typically South Vietnamese soldiers clear the road, and then we clear it again because we do not trust them. I have to be honest, before that evening I knew nothing about mine sweeping equipment or how it worked. Now I do. So we get out there and I do not expect to find a mine or a booby trap, but we do. It is a 105 mm howitzer shell in the road. I cannot believe it. We have another lieutenant with us, a new guy. He immediately gets a knife and he’s going to probe. Durant pushes him back and says, “No lieutenant, let’s do it this way.”

Durant acts like he’s done this a million times. It’s his first time but you wouldn’t know it. Durant takes the knife and probes around and checks for any wires to make sure it’s not command detonated. I had just gotten a new Yashica 35 mm camera and I snap a picture of him digging around the land mine. He looks up at me and says, “Lieutenant, what in the hell are you doing?”

I say, “I’m taking pictures, Top. This is cool.”

He gets the mine exposed, wraps detonation cord around it, inserts a blasting cap, and then blows it. I’ve got pictures of the whole process. We immediately contact the battery, because when you see a puff of smoke you think, Oh no, we just lost another couple guys.

Gulley and Sherlock died on the road right before Durant got to Sherry. He is going to make damn certain that does not happen again. That’s why he straight off gets onto straightening out our mine sweeping.

When we get back to the battery he says, “Well it’s time to go on convoy.”

I say, “What do you mean time to go on convoy? I’m not going on convoy.”

He says, “XO, XO, come on. Didn’t I tell you we’ve got to lead these guys?”

“OK, but I’m not going out in a jeep. If you want me to lead the convoy I’m getting the biggest truck we got in the battery and we’re sandbagging it and I’ll go.” I get a five-ton truck. We put the windshield down and I pile up sandbags on the seat so that I’m sitting on a mountain of sandbags. And we go to Betty for our supplies.

Parker high In the saddle on convoy

From that time on I am always in the lead vehicle on convoys, usually with Durant beside me. I’m in a jeep now, confident that the road is safe because I’ve swept the road myself. The second vehicle is one of our Quad-50s right behind me (four 50 caliber machine guns mounted on the back of a five ton truck). When you’ve got the Quads with you on convoy the Viet Cong are not going to mess with you.

Parker and Durant leading convoy

Followed by Whispering Death

In every little thing Durant brings a new approach. He stresses the importance of keeping food out of our hooches and keeping the grass down on the perimeter, because of hygiene and rats. He doesn’t just rely on his sergeants to know the guns or do the aiming circle (a survey instrument used to orient the howitzers. At Sherry it is mounted on a small tower). He gets up on the aiming circle himself. He sees to it that assignments are fair, that the rotation is uniform. It’s not that he lacks discipline. We still search hooches, and if orders come down to do something we do it, but he does not make it offensive. He tells the men why we are doing something, the purpose and the reason, and explains why it’s a good reason. He does not do things just to be doing them. At night when we do guard duty, he takes his own guard rotation, and so do all of his senior sergeants. When we go into Betty to get ammo, he helps load ammo and unload ammo. That’s unusual for a first sergeant, and he expects his other sergeants to do the same.

The air around the battery changes almost instantaneously. The guys know that here are people who are interested in us. They are not just telling us what to do, they’re showing us.

We get a call from battalion in Phan Rang telling us a kid had thrown a grenade at one of the

First Sergeants and they are sending him out to Sherry. Apparently we are considered the unit that knows how to deal with the tough guys. Durant gets me and Chief of Smoke Cerda (senior sergeant in charge of the howitzers) and says, “We got a new guy coming to the battery and he’s got some difficulties.”

I say, “What do you mean, difficulties?”

“Well, he threw a fragmentation grenade at a First Sergeant. It didn’t go off and they decided they better send him out here to us.”

I say, “What? That’s more than a difficulty.”

He says, “No, we can deal with it. When he comes out here I‘ll have him brought here to the hooch and we’ll introduce him to you and myself and to Cerda.” So they bring him in from the helicopter pad to the command hooch. Andy Kach, our ammo section chief, brings him in and says, “Here’s Frag.”

We don’t even know his real name, and he says right off, “I’m not going to do that here.”

Durant says, “You got that right, boy!”

Frag says, “I didn’t like all the grief in the rear, painting rocks and stuff.”

Durant says, “Here’s how it works. If you have any problems or disagreements you just come and tell one of us. You don’t throw grenades; that’s not an appropriate way to settle a dispute. However, if you feel like you need to throw a grenade, you better make sure we’re all three together and you get all three of us, because otherwise you’re going to die.”

He turns out to be a really good trooper. And he never loses the nickname Frag.

Mama-San Medevac

Mama-san is giving birth, and she’s just huge. This is a Caucasian baby and the baby is too big. There’s blood everywhere. The doc thinks she not gonna make it; she’s gonna die.

He says, “What are we gonna go?”

I say, “We’ve got to get her to a hospital. I’ll call a Medevac.”

I do and they say, “What’s the situation?” I tell them and they say they’re not going to come.

I say, “You get out here.” I have an inkling of who the father is and say, “We’re responsible for this woman and this baby. She’s gonna die if I don’t get her to a hospital.”

I get the Medevac and we get her to the hospital. The next day I go to Phan Thiet to see her. By then she is in a Vietnamese facility and it is deplorable. There are pallets on the floor in a building that is almost collapsing, with sewer water and flies. But she’s happy with a bouncing healthy baby.

Of course Mama-san comes back out to the battery. We have no idea what happened to the baby, but the assumption is that family in Phan Thiet is taking care of the baby.

From that point on she knows that I will take care of her and her girls. And they take care of me. The little girl Cindy would get me coffee in the morning, clean my hooch. Of course everybody thinks Cindy is my squeeze, but no way.

You see my picture of Mama-san and the other Vietnamese. You don’t just take pictures. They run and get into their best clothing, because this is special for them. The one color picture they’re going to have for the rest of their lives.

Part of our role in Vietnam is to win hearts and minds. If you let someone die on your firebase you’re not going to win many hearts and minds. When you get down to the brass tacks of what we were doing, if a person in combat can say, I did the right thing, even if the consequences are negative, you can live with yourself. I know it’s the right thing to do, and that if I didn’t do it, make an attempt to do it, I would have difficulty living with myself.

Mama-San back row center

Cindy front row center

October 22, 2014

Captain Hank Parker – Battery Commander – Part Six

Captain Hank Parker

PART SIX

On April 2, 1969 two boys of B Battery are killed by a landmine while minesweeping the road.

Shortly after Sherlock and Gulley are killed I leave the 3/506 infantry and go to LZ Sherry permanently. I consider it a promotion because I finally get my ass out of the field. I’m thinking Sherry is going to be safer than being out with the infantry. Far from the truth. When I went from patrolling with the South Vietnamese forces to deploying with Captain Wrazen and the 3/506 I went from the frying pan to the fire. Now at Sherry I am in the center of the fire. I’m in the bull’s eye. We are a forward unit in a fixed position along a major infiltration route: sitting ducks.

B Battery at LZ Sherry

The Ghost

The battery commander is constantly gone. Anytime he can find an occasion not to be at Sherry he takes off and goes to the rear to battalion. Even when he is at Sherry he is rarely out of his hooch. During attacks he is never to be seen. People call him The Ghost.

Understand that this captain is a nice guy. I like him. I like playing basketball with him, but that is the only time I see him out of his bunker other than to take a shower. Once I see him on top of our outdoor shower with its 55 gallon drum and Bunsen heater, dark smoke pouring out of the stack. I say to him, “Are you nuts standing up there? And with all that smoke flying you’re telling Charlie where to send the mortars.” After that I never see him up there again.

The captain knows what he was doing in terms of paperwork and things like that, seeing that the battery is resupplied. But he is never on a convoy, and never out when the mortars are falling. You need to have that presence for the men. That pretty much leaves it to me and First Lieutenant Chuck Monahan to run the battery. On paper Chuck is the XO (Executive Officer and second in command), but in reality he functions as the battery commander and I as his XO.

1st Lieutenant Chuck Monahan

Courtesy Rik Groves

Shrapnel-In-Your-Ass Policy

The first sergeant (the senior ranking sergeant generally called Top) has his favorites, carries grudges, creates make-work for the men, is overly punitive, and generally disappears during mortar attacks. Don’t get on his wrong side or he’ll try to get you. With all that I like him and I have good times with Top. I go over to his hooch and we drink Pabst Blue Ribbon, my favorite beer. We arm wrestle and oh my God I don’t stand a chance I’m such a skinny little runt. I laugh watching him sing Oh Danny Boy to Mulvihill – two Irishmen.

More than anything I feel this first sergeant is lax about perimeter defense and I have conflicts with him over making sure our wire is in place, not cut, the claymore mines are there and checked regularly. There are a lot of enemy units out there right near us. I know how close they are from my time with the 3/506 and how quick they can maneuver. Another lieutenant and Top disagreed over adding additional coils of concertina wire to the perimeter, an argument Top lost. When the lieutenant is out Top goes through his hooch checking for contraband to try to get something on him. The lieutenant confronts him and says he doesn’t ever want to see him in his hooch again. That’s the kind of guy my first sergeant is.

When he wants to give an Article 15 (non-judicial punishment), Monahan and I never sign off on it, not once. We tell him discipline has to be uniform. If you want to ding somebody because you think they are smoking pot, then you got to ding the same guys who are drinking alcohol and obviously impaired. You can’t choose one over the other. I say, “Once we do our inspection and find their stash and take it, that’s punishment enough. That costs them because we took their stuff. Give them a couple of extra details. Give them some extra duty to let them know that we are not going to tolerate this. You violated the rules and you are getting punished.” I do not see the necessity of, number one taking away money, and secondly taking away a stripe. I think that is too severe, particularly in light of what the men face day in and day out. Top does not appreciate the amount of work these guys do. They are working around the clock every day of the week. Life is miserable for them, and they are sleep deprived all the time. There is no need for petty or useless details.

I observe Top keeping a very low profile during rocket and mortar attacks. His great ambition is to get a Purple Heart, but without getting hurt too bad. After a mortar attack he comes to me with a gash on his forehead and claims he came charging out of the bunker and hit his head. He says he should get a Purple Heart for that because we were under enemy fire. I say, “Top, I don’t know that you got that cut on your head coming out of the bunker; I think maybe you got it going into the bunker. Here is the policy that I follow for Purple Hearts out here and that you will follow. You’ll never get a Purple Heart until Doc Townley takes a piece of shrapnel out of your ass.”

Top and I also clash over who gets medals. These are medals from the Vietnamese government – the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry (for deeds of valor or heroic conduct while in combat with the enemy) and the Civil Actions Medal (for outstanding achievements in the field of civil affairs). A list would come down with how many we had to distribute in the battery. Top would get his senior sergeants together to determine who were going to get medals. This practice Lieutenant Monahan and I change. No, you get your gun chiefs and you bring them into the meeting. You let them determine who on their guns should get one of these medals.

Top objects, saying these guys are just draftees. It has no meaning for them because they are not going to be career soldiers. At that time I do not understand what he means, but later learn that for career soldiers medals earn points for promotion. However, and this surprises me, the only medal that does not earn points is a Purple Heart. So I never knew why he wanted a Purple Heart, other than to say, “I was wounded.”

Scorpion Fights

When I came to Sherry there was me and three other lieutenants and we’re all in the same hooch. One of them liked to bring food back from the mess hall and eat in the hooch. I said I didn’t want any food in the hooch because it brings in the rats. And the rats bring in the snakes. So I decide I’ll build my own hooch. This is when I first meet Andy Kach, a PFC at the time. I think his name is Johnny Cash, because somebody gave him gave him the nickname. He comes up in these big dark glasses and says, “Hey lieutenant, can I help you with that?”

I say, “Sure.”

In the process of digging down to start the hooch foundation we find a bunch of scorpions and everything stops. Huge black scorpions. Guys from the guns come over because they want to see them. So we catch a bunch of scorpions, make a little ring, and instead of building a hooch we’re going to have scorpion fights. We’re placing bets on these scorpions. That memory is so vivid I don’t remember ever finishing the hooch.

Sergeant Cerda – Chief of Smoke

(senior sergeant in charge of the howitzers, usually called just Smoke or Chief)

Courtesy Rik Groves

Chief Cerda says to me, “Lieutenant, come with me to the First Sergeant, we’ve got something.” We go out to the wire to where a unit of the South Vietnamese infantry is located. Top and Cerda have a LAW (light anti-tank weapon), a portable rocket fired from the shoulder and with plenty of punch. They are playing with this thing, neither one of them knowing how to operate it. I had seen the infantry with them so I showed them how to shoot it. They say, “You shoot it.” So I flip up the sight and fire it. The projectile just goes PLOOP and drops out of the tube and lands at my feet. They both run! And if I had any sense I would have too.

When mortars land we do crater analysis on them. You run out and shoot a back azimuth from the fin sticking out of the ground, and that gives you the direction from which the mortar had come. In order to do that you have a compass, which you read by the light of the flares in the air and a flashlight. You send the direction and distance to Fire Direction and quick as you can a gun blasts the hell out of that area. You’ve got to do it fast, while the mortars are still coming in.

Chief Cerda is there with me holding the flashlight. I don’t know his nationality but he has a heavy Hispanic accent and he gets really excited. I say, “Slow down, Chief, I can’t understand you. And quit moving the light.” I think he’s saying, Hurry up, let’s get the hell out of here.

I’ll say this about Chief Cerda, he knows the guns. He knows howitzers, how to fire them, how to keep them clean, and how to train the guys on them. He is really good. That is important to me because I don’t think the first sergeant knows guns all that well. If he does he does not display it to me. And you never see the first sergeant and The Ghost out during a mortar attack doing crater analysis like they’re supposed to be. It’s just me and Chief Cerda.

The guys like Smoke. He relates to the men on the guns and to the officers. When the officers go to the captain’s hooch for beer Cerda always comes in with us. Tommy Mulvihill comes in too. (Picture of Mulvihill sitting on Cerda’s lap and me petting my little dog.) Cerda is pretty good at crossing between officers and enlisted, going back and forth, but not as good as Tommy.

One night after too much imbibing, Chief Cerda and I get my AK-47. Cerda puts on black pajamas like a Viet Cong and we’re going to go out to the road, and we’re going to catch VC planting mines. We start to crawl out through the wire past Tower 1 by the main gate. Cerda gets his butt caught in the wire and sets off a flare. He’s brown, and he’s short and he’s got black pajamas on, and he’s in the wire. He yells at the guy in the tower, “Don’t shoot, it’s me.” The guy in the tower can see me too, and I’m white as a ghost anyway. The guy in the tower has to think, What the hell is going on here?

We did not think this operation through very well.

October 15, 2014

Captain Hank Parker – Battery Commander – Part Five

Captain Hank Parker

PART FIVE

After being wounded at Betty I go back to Sherry to recuperate and I’m an immediate celebrity. I’m wounded, I got war stories, and I got trophies: my captured AK-47 rifle and North Vietnamese Army web gear. The AK-47 makes its way around the battery because I also have several banana clips of ammo and everybody wants to shoot it. They want to hear and feel the difference from an M-16.

Parker With His Captured AK-47

At Sherry I walk the guns and visit the guard towers and have the same kinds of conversations I had with Captain Wrazen. You get close. Relationships you never forget. On this trip I’m telling the guys, “You have bailed us out more than once. You’re appreciated.” They like to hear that.

Rik Groves (Crew Chief on Gun 2) in one of his journal entries talks about the frustration of not knowing the consequences of their artillery fire. When I’m out as a Forward Observer I call back to the Fire Direction Center after every mission and give the body count, the weapons count, and any blood trails we saw. I let them know that they had bailed us out, saved our asses. It is important to me to let the gunners know that their fire was accurate, it was timely. I puff up my chest with the 3/506 Infantry and brag about Sherry, “My guys can knock the nuts off a gnat.” And they can! You know I am not going to call in first round high explosive if my guys are not expert artilleryman.

At the same time I tell the Sherry guys we’re in a dangerous area here. I’d seen the extensive bunker and tunnel complexes just north of Sherry. I’d fought through them so I know the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong are camped on our doorstep. To make matters worse this is Ho Chi Minh country. When I was in Hawaii before Vietnam I went to the library and read as much as I could about Vietnam. Phan Thiet came up in my reading because Ho Chi Minh was a school teacher in Phan Thiet. I try to impress on the guys that this is hometown for Ho Chi Minh. These people revere him and are loyal to him. We have to keep that in perspective all the time. Anything that comes into the battery or goes on around the battery you might as well consider to be unfriendly.

The Poor Elephant

After a couple days of recuperation I’m out with Delta company of the 3/506 again and a new company commander, Captain Roy Kimoto. This is a large operation with the entire battalion, all three line companies, in tandem with Regional and Popular Forces. There are close to 1500 soldiers on the ground.

We are the last unit to combat assault into the mountainous region north of Sherry. The fighting is heavy, at a higher level even than the action at Betty just a week earlier. With artillery support from Sherry we kill and wound a lot of enemy soldiers, and we destroy a large number of base camps and bunker complexes. We are extremely effective and put a big dent in the North Vietnamese regulars and the Viet Cong in the entire Binh Tuan Province (where Phan Thiet is located).

Captain Kimoto is a competent infantry commander, but once I get real annoyed him. He has me out bushwhacking, well out of the range of our 105s. I do not like that; I want to be within range of Sherry.

But I am still within the maximum range of the 175s at Sandy (Firebase northeast of Sherry. The 175 mm howitzers there were the largest land artillery pieces in Vietnam, with a maximum range of 25 miles. They had a considerable range error, meaning they shot both long and short of the target, and making it imperative to be well away from the target and certainly off the target line.) I fire the 175 once at night. We are ON THE TARGET LINE – not safe! – not safe! – and we kill an elephant. The elephant cries all night before dying. Oh my God it’s horrible. That shakes me to the core it is so sad. I get mad at Capt. Kimoto and say, “You can’t get us outside of our support range of my 105s.”

In the meantime I get on various radio frequencies and manage to get in touch with some U.S. Air Force. These are guys running missions up north and on their way back. I say, “Have you got any ordnance?” They tell me what they have and I give them coordinates and they fire it for me. So at least the enemy thinks we have air support, which I figure scares them off.

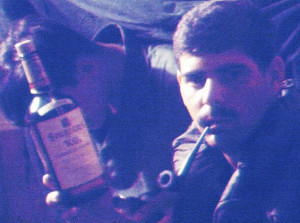

POW

We are now further south, and close into Sherry. Regional and Popular Forces encounter a company size unit of Viet Cong well dug in. We send a recon element in support, together route them, and capture four prisoners. One of the prisoners is a high value POW. From documents he is carrying and what our interpreters get from him, he was on the attacks at Sherry and Betty. We bring him back to Sherry for an initial interrogation, where there is a picture of him in a jeep. The others go to Betty, and he also eventually goes to Betty for full interrogation.

POW Blindfolded

The result of the interrogation is that our artillery had really hurt their main North Vietnamese force. He acknowledges to the interrogators the damage we did to them at Sara, Sherry and Betty, all within a period of just six weeks and due largely to the artillery. Sherry is an ongoing thorn in their side that they want to remove.

From that time LZ Sherry becomes an even higher priority objective for the enemy.

Sherry is a forward-placed artillery unit right smack dap in the middle of their infiltration route. They have to come by us. Add to that the radar installation that goes in at Sherry, which is anti-personnel and allows us to see movement around the area. This does two things. It makes us more dangerous to them, but the radar tower also gives them a nice tall aiming post. You’d think we’d be easy to take out, but they find out very quickly that we’re not, that we pack a punch.

I’ve got a lot of pride in the artillerymen at Sherry because, try as they may and try as they might, the enemy does not get us. They do their damage, but they never get our battery. All the way up to Field Force and Corps levels people come down to see what is different about LZ Sherry. They want to be able to say, I was at Sherry. Even General Corcoran comes to LZ Sherry.

Lieutenant General Charles Corcoran commanded the First Field Force, comprising all military units and operations for approximately half of South Vietnam. He later played a role in getting Andy Kach his Bronze Star. He passed away the next year on September 24, 2013 at the age of 99.

Combat R&R

(Rest & Recreation)

I was only out with Kimoto a few weeks when I get notice I am going on R&R. Alex Taubinger, another lieutenant out of B Battery at LZ Sherry, comes to the 3/506 Infantry to replace me. They send a helicopter out to get me, but the terrain is too dense for the chopper to get in. I have the guys blow some trees down for me with det cord (flexible plastic tube filled with explosive) so I can get to the helicopter. Climbing up one of the trees we had blown in half I gash my leg pretty bad. So I end up going on R&R with a wound I gave myself.

I go to Hawaii and stay at Ft. DeRussy on Waikiki Beach, where I had been stationed with Captain Schlottman before going to Vietnam. I’m driving through the Marine base, and as I pass the ammo bunkers there I see attack planes coming over the mountains and dive-bombing. I scramble out of the jeep as fast as my leg will let me and take cover. I’m thinking, This isn’t how Rest & Recreation is supposed to work. I learn later, to the delight of my companions, that it was a scene being shot for the movie Tora! Tora! Tora!

October 8, 2014

Captain Hank Parker – Battery Commander – Part Four

Captain Hank Parker

PART FOUR

The Battle for LZ Betty

February 22, 1969

I am airlifted with Delta Company back into LZ Betty (eight miles south of Sherry – a sprawling complex of unit headquarters, ammo bunkers, oil storage tanks, and an airfield). They move us off into a separate compound for the 101st Airborne to rest, where we get steaks and can wind down. When you’re in the field it’s intense. You’re sleep-deprived all the time and on alert 24 hours a day. You come in and have a chance to decompress, have a few beers. The officers get hard liquor, the senior sergeants get hard liquor and beer, all known as juicers, and the enlisted men below them are the heads with their joints. You have to be careful about the marijuana because it’s still a court martial offense.

Capt. Wrazen says to me, “Hank, you can take off your helmet and flak jacket now.”

I say, “Captain, I’m just not comfortable. Something is not right here and I’m gonna keep my gear with me and on.” I instructed my RTO to do the same thing. My unease comes from that earlier engagement in the field when we were outgunned. A much larger enemy unit could have easily stopped us and they chose not to, and that means they have something else in mind.

At Betty they have a policy of taking away weapons from the infantry and anyone else coming in from the field. All the weapons are locked up in a CONNEX building. I am puzzled by that because in the field these guys are terrific. In the field they are crisp, coordinated, never fire on one another. But back at base camp they can’t be trusted; I cannot not understand it. The battalion commanders here are good, so it has to be their higher ups.

I keep my M16, as does my RTO. So that morning at 2:00 AM, when the rockets and mortars and small arms fire start, my RTO and I are the only ones with weapons. We’re in the stand-down area for the 101st on the sea side of the compound where deep gullies run down to the beach. That is where the enemy is coming in, up those deep gullies overgrown with brush.

We give our weapons to Wrazen so he can go out to the bunker to secure that part of the perimeter that was breeched. I see Sergeant Beasley trying to get into the CONNEX building with the arms that were locked up. Here you’ve got the most experienced fighters that could have ended this in short order and they don’t have access to their weapons. You basically have REMFs doing the fighting.

Wrazen tells me to take up a position at the gullies. I rip an M60 machine gun off a jeep and Wrazen tells me where he wants me to go, just down from a bunker he is occupying. I am close to him, maybe ten feet away. He is in the open on the top of a French bunker, a concrete bunker with ports. I see tracers coming in our direction. I look over and see his body jerk and then go down. I run over to him and arrive at the same time as First Sergeant Horn and another lieutenant. He is already dead I think. They get a jeep and take him to the battalion surgeon. I continue on doing what he told me to do securing that part of the perimeter that was in front of the tower with the steep incline in front of it. You got enemy fire and mortars coming in and tracers both green and red flying in all directions. I know I have to get the infantry positioned like Captain Wrazen ordered before dying.

I drive stakes into the ground by the bunker and off to its right, so that when the infantry comes I tell them you can’t go beyond those stakes because the enemy is inside the wire and you don’t want people shooting at one another. I show them where to fire and where not, because you have battalion headquarters over there.

Another infantry lieutenant and I go up into the tower at that end, because whoever was supposed to be there had abandoned their M60 machine gun. You low crawl when you can, but I remember we stand up and run for the tower. We get up there and fire the M60 to the extent that we almost melt the barrel down and have to replace it.

I come down from the tower to get some support, either artillery or gunships. I also get a jeep mounted search light and position it where I know we have an enemy squad pinned down. I have a handheld flare and a radio on my back when the gunships show up. Where my RTO is I don’t have a clue. I’ll see him again in the morning it occurs to me.

The gunships arrive pretty quick. I turn on the spotlight, train it on the enemy position and pop a flare in that direction. When BOOM I’m blown off the jeep. I don’t know what it is, maybe a B40 rocket, but it shatters the light, peppers me with glass, and sends shrapnel through the radio, through the flack jacket and into my shoulder. The jeep turns over with me on it and knocks me unconscious for what feels like just a few minutes. I come to, get up and continue to fight. Me keeping my flak jack, helmet and M16 – I didn’t have to go looking for them – saved my life.

Now a sapper gets into an ammo bunker loaded with 42 mm mortar ammo. He blows the bunker with a satchel charge and a B40 rocket. It’s just blowin’ and goin’ everywhere all night.

We fight throughout the night, and when the sun comes up we evacuate the wounded and killed.

There is Captain Wrazen, PFC Tweedle and Sergeant Allen – all killed. We have over 20 wounded, including me. I get treated for my head and back, but I won’t take any sedation because I want to go with the infantry on a sweep to pull in the bodies of the enemy we had killed or wounded. Of course my RTO is now there.

We start the sweep. Betty has sharp and deep ravines of red clay running down to the beach covered with heavy, dense scrub brush.

Tower and Brush Covered Ravines

We’re going through the ravine probing looking for bodies or whatever we can find. In the process of doing that I have a bandage on my head. I put my steel pot helmet on and as we move forward it keeps falling off and I just put it back on again.

I have the sling of my M16 over my shoulder and my finger on the trigger guard. On this occasion my steel pot falls off. I reach down to get it with my left hand and my barrel hits something. I look and its an NVA soldier. My barrel is right on his head and his AK47 is right in my belly.

My RTO, a black man says, “Lieutenant Parker, you’re turning white.”

I say, “Shut up, Godamit.”

I look at the NVA and we lock eyes. Instinctively I say, “Dung lai, ong. Chieu hoi.” Give up, Sir. Surrender for clemency.

He looks at me and says, “Chieu hoi?”

For that reason I don’t shoot him. The other reason is he’s got web gear on. I’m thinking if I shoot this guy he’s going to blow up. I don’t know what he’s got. So I back off, he drops his weapon, he drops his web gear, and we get him.

Now I’ve got to protect him from the infantry. They want to kill this guy. Their captain’s dead and they want to kill him. I say, “No, I’ve offered this guy clemency, we’ve got to take him in.” I emphasize what Captain Wrazen said: A prisoner’s worth more than a hundred dead people. “This guy’s a prisoner, we’re going to interrogate him and get important information.” We turn him over to the MPs and continue our sweep. We find a whole bunch of bodies and weapons.

I go over to Graves and Registration where bodies are prepared for shipment home. I see Captain Wrazen’s body after the autopsy and I talk to the surgeon. The bullet hit him in the upper chest as he was laying prone and exploded his lungs. There is speculation that Captain Wrazen had been shot from the rear, that it was friendly fire. I can speak authoritatively that he was hit from the front.

A territorial thing, the infantry battalion commander is really pissed that an artillery FO captured an NVA. He feels his infantry should have done it.

GIs Hurl

Reds Back

At Camp

Saigon – Communists tried but failed to overrun an American landing zone near the South China Sea early Saturday.

The band of Reds laid down a 30 round mortar barrage, then charged the landing zone near Phan Thiet, 95 miles east of Saigon.

The Reds opened up on the camp at 2 AM. GIs of the 101st Airborne Division (3/506 Curahees) called for spooky and helicopter gunships and fought back.

The Americans, station more than 200 miles south of the bulk of their division, hurled back the Reds but not before a handful used Bangalore torpedoes to break briefly through their lines. They were repelled.

Two Americans were killed and 29 wounded in the night battle. The Communists left 12 bodies behind, as well as eight weapons and 11 grenades.

Pacific Stars and Stripes

Monday, Feb. 24, 1969

The newspaper article got it wrong. There were three GIs killed.

It was a sad moment loosing Captain Wrazen. He tried to convince me to go infantry. I was really close to him. In our night positions we would talk. I knew he was married and had a couple boys. We’d talk about his family and his plans. It was a special time. It’s that kind of relationship you establish in combat.

Captain Wrazen always wanted to come out to see the guns and meet the crews at Sherry, but unfortunately he died before that could happen. When an infantry commander says he wants to come and see the fire support base you cannot ask for higher praise.

October 1, 2014

Captain Hank Parker – Battery Commander – Part Three

Captain Hank Parker

Part Three

A Long Day

Three days after the Zippo incident I go out on an amphibious landing to rescue American POWs. The operation is out of LZ Betty with the 3/506 Currahees. The guys running the operation have tight crew cuts, khaki shirts, no name tags, and aviator glasses – intel types. They give us the maps and the coordinates and other information, and away we go … but without the crew cut types. In the early morning dark we depart on LARCs (boats on wheels used to shuffle cargo from ship to shore, today used for Boston Duck Tours). A guy by the name of Grimaldo took 8 mm film of us getting ready to deploy. I see me from the back and I see Captain Maupin standing there. We go north toward Song Mao. When we arrive at the designated location the first LARC hits the shore, drops its grate and everybody charges out. When my LARC arrives it stops well short of the shore. I come charging out and immediately sink. It’s still dark and I think I’m going to drown. Nobody had told me that on a rucksack there is an emergency release. Somebody grabs me and pulls me out. I’ll tell you salt water in short order makes your M-16 useless. It rusts almost immediately and is inoperable. We force march for most of the day, and we find a campfire that is still smoldering, and it’s got a set of shackles. We continue on and set up our night NDP and an in-place ambush on the trail. In the course of the night there’s this large explosion. Again I smell the blood mixed with cordite and I know we killed somebody. A new guy, who I guess was nervous, blew the ambush too soon. The guy he killed is an interrogator and interpreter. He is in a brand-new uniform. On his waist he has a Soviet pistol with the red star on the handle. He has a spiral-bound notebook with signed confessions from POWs. The notebook has profiles of US soldiers from private to four-star general and newspaper articles of the Detroit riots to be used for propaganda. He has currencies from four different countries and some stamps. This guy is not a fighter. His pistol still has cosmoline in the barrel (a rust inhibitor used to store and ship weapons). It’s a shame we didn’t capture him. We could have gotten the information on the POWs probably without much trouble. In fact I think he may have been coming in to do that, the way he was walking down the trail. What ensues after that is an argument on who gets the weapon. I have to mediate and I say it should be the guy who killed him. Even if it’s a blown ambush he gets the gun. At 1725 hours we are extracted. By the end of the mission I am exhausted. In later years I had a heck of a time finding just a few sketchy facts about this mission in daily logs. My guess is this was a top-secret operation that is still classified.

Alive is Better Than Dead

One of the things Captain Wrazen does, and it scares the crap out of me, after a fire fight he asks me to call in illumination. I say, “What do you want illumination for?” “We’re gonna crawl out and drag the bodies in.” “Why? Let’s wait until daylight.” “No, for the intel. Some of them might be alive. We can interrogate them and get intel.” So I call in illumination and I go out with him and we pull bodies back in. He says, “Hank, let me tell you what. Anytime you can capture somebody, that’s worth more than a hundred kills because of the intelligence you can get off them. If you can take somebody alive, you do it. You don’t risk your life, but if you can capture somebody, do it.” Further he doesn’t count a body until he has the body and the weapon. He doesn’t doctor his count. And I take all that to heart.

Captain Gerald Wrazen

A Voice of Reason

I’ve never told anyone this story. It occurs during the really heavy engagements between January 9 and Feb 22, when we’ve got three infantry companies out in the bush fighting several battalions of NVA. I’m out with just a squad of guys on a clover leaf and separated from our main platoon. We walk into a well planned L-shaped ambush which we manage to pull out of without taking any casualties. I know at this point that we are in the middle of a heavy concentration of NVA who are packed into tunnel complexes. As we are pulling back to our platoon I occasion upon an NVA soldier. He’s maybe 100 yards from me. I see him and he sees me. He is a high ranking officer and unarmed. We establish eye contact. I put my M16 on him and am getting ready to shoot him. A voice stops me, Henry you don’t have to kill this guy. He’s not a rabbit; he’s not a squirrel; there’s no purpose in killing him right now. The impression of a voice is so strong I turn my head to see who said this to me, thinking it’s my RTO, and there’s nobody there. Of course I’ve still got my rifle on the NVA officer and he’s looking at me with a puzzled look as if he’s wondering, What are you going to do? I put my rifle down, turn around and walk away. And he disappears into the tunnel complex. It’s always puzzled me what happened there. It was an outside voice; I heard it. As I reflect on it now had I killed him, his troops probably would have finished us off, because we were definitely outnumbered, even with the good support that we had. It would have been difficult to bring in a precise artillery strike because of the closeness of our support elements. We were basically at the tail end of the operation and we had other elements of our battalion being extracted. I think it was a logical and almost instantaneous thought process for me, that there’s nothing to be gained here. He is not a threat to me, not a threat to the platoon. So maybe the voice was mine, putting thoughts into words. As I’m walking away I have this tremendous feeling of relief, because it had been a pretty heavy battle and we’re walking away without casualties. By this time I’ve seen a lot of action and I’ve got instincts, in this case the right one.

Reason Wins Again … Eventually

On the same operation we’re going through the jungle. We find supply paths, and when we find another tunnel complex I get interested. I’ve never been in a tunnel and figure I’ll take a peek. I start down into this tunnel and I see this wire and I think, This isn’t my job. I back out and tell the platoon sergeant there’s a tripwire in that tunnel, let’s not mess with it. Another time on that operation we find unexploded ordnance, a 150 pound bomb. This thing was eventually going to be used against us if we didn’t destroy it. Probably end up as a road mine. I wrap C4 plastic explosive around the nose of this thing, set blasting caps and get back. We blow the C4 and FUMP – the bomb moves two feet. That’s it. Then I think about it. Hell, if we’d exploded that shell it might have taken us all out. I have seen the craters these things make and by God we would have been in the crater if it blew. This isn’t my job either. But at that time you couldn’t get EOD to come out (Explosive Ordnance Disposal). We flag it and eventually get somebody to come and get it out of there. We should never have tried blowing it on our own.

September 24, 2014

Captain Hank Parker – Battery Commander – Part Two

Captain Hank Parker

PART TWO

ARVN – South Vietnamese Soldiers

Kluk Kluk Kool-Aid

I had been a month without mail when somehow a package comes in for me while I’m on another operation with the ARVNs. I open the package and it’s got Kool-Aid in it. The ARVNs never had Kool-Aid, so when we’re stopped by a beautiful, clear mountain stream I take the opportunity to make Kool-Aid for them. You couldn’t ask for cleaner water. We all go down to the stream and they fill their helmets with water. I mix the Kool-Aid in and they drink it right out of their helmets.

After the Kool-Aid the water looks mighty inviting so we decide to take a dip in the stream and wash up. I been out there so long my fatigues are beginning to walk by themselves. Jeez, talk about smelling bad. I strip down and get ready to hop in the river and bathe. The thing about the Vietnamese when they get in the water they never strip, they got their shorts on. They’re very modest. Well I strip down and I hop in and we’re all swimming around and bathing and having a merry old time.

All of a sudden the Vietnamese start making this sound, “Kluk …Kluk.” The Vietnamese are pointing and all yelling “Kluk … Kluk … Kluk.” I’m looking for a duck and they’re getting out of the water and running all over the place. But I don’t pay it any mind. I’m buck naked, backstrokin’ and spitting water into the air in a nice little fountain. All of a sudden I see these eyes looking at me in the water. Holy crap! I walk on water getting out of there. I never moved so fast in my life. I don’t know how I did it, but I am up and out of the water in a blink. The Vietnamese are standing around laughing and thinking this is hilarious. Kluk … Kluk stands for something like an alligator. It’s the sound the animal makes.

I never knew what this beast was until after Vietnam on one of our family trips to Asia. In a small rural town we’re looking at the egrets coming into roost in the evening. They are a pure white all landing in the trees, and there’s hundreds of them. I’m watching the birds and I hear “Kluk Kluk” and BAM! there goes one of the birds. It was like a huge Komodo Dragon. I got up on top of a dam and saw one that was at least nine feet long. I leaned then that Kluk Kluk meant to get out of the water … fast.

Stripping for Kluk Kluk

That Special Smell

I get word that I’m going back to LZ Sherry as Assistant XO (third in command). But right away I’m going out on a heliborne operation. I get to Sherry the day before the operation and I see the helipad it’s loaded with howitzer ammunition, ready to go, a small mountain of explosives. I say to the battery commander, “What’s the ammo doing on the helipad? It’s not secure.”

He says, “It’s for the heliborne tomorrow.”

I say, “I don’t think that’s wise.”

He says, “Just lump it.”

“OK. You’re the boss.”

I look for a place to hooch for the night in one of the hooches reserved for lieutenants and dump my stuff. Then I walk around talking to the various gun crews. I go to the FDC (Fire Direction Center) to get more information on the heliborne, but they do not have much. So I go back out and I begin to familiarize myself with the battery area: where the perimeter defenses are, where the ARVNs are, where the towers are, things like that.

The day is coming to a close and soon it’s night. You know how Sherry was; when it was dark it was pitch black. In the early morning hours the battery is shooting a fire mission for the infantry and I go back to the FDC to observe. That’s when I hear a call come in from a tanker stationed on our perimeter, “I’ve got movement in the wire.” He says in the wire! Whoever is on the radio is stunned, like a deer in the headlights. I literally take the handset and say, “Jesus Christ, Fire!” Because I know. And BOOM. When a tank fires it’s an entirely different sound. It fires only one round, a canister round (like an enormous shotgun shell loaded with ball bearings).

Things go into slow motion and maybe because I had been in more combat I got a familiar smell. When you have casualties the blood and the cordite from the powder mix and send out a special odor. Almost instantly I smell it and know we killed somebody. Remember at this point we’re in a fire mission, the guns are shooting in support of the infantry. At that point the guns switch to their sector fire on our own perimeter. Now it’s organized chaos. The guns are firing, there’s illumination in the air, the towers are firing machine guns.

I know we wounded a lot people just from the smell, but find out in the morning that we had killed 23 soldiers, a lot in the wire from the tank round, and more in a cluster of bushes probably from the howitzer sector fire. Those guys had Bangalore torpedoes and satchel charges. If they had gotten past the wire the howitzers would have been useless, and had they set off the ammo on the helipad that would have neutralized the battery. We would have been hard pressed to even have fired direct fire with Bee Hive rounds.

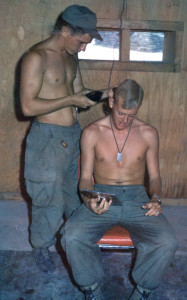

At that juncture everybody who’s anybody in our field force area has to come down and see this and take pictures. The bottom line if you look at the soldiers and the weaponry, you have a combination of NVA, sappers and VC. And of course there among the bodies is our one-armed barber. After that Judson becomes the barber. I have a picture of me sitting with Judson cutting my hair. That’s significant because this is a safe barber.

Parker Getting a Safe Haircut

The Battle for Outpost Sara

That morning, instead on going on the heliborne operation, I go back to Betty and then out as an FO on as assault with Delta company of the 3rd Battalion of 506th Infantry.

The 506 is a regiment of the 101st Airborne Division. It’s known as The Currahees – Cherokee for ‘Stand Alone.’ Formed in 1942, it played a major role in WWII engagements on D Day and in the Battle of the Bulge.

All of the operations I go on with the 3/506 are to the north of Sherry between the battery and the village of Thien Giao. I am shocked when I see the tunnel complexes and weapons caches, and here is our firing battery sitting in the center of all this. We’re talking battalions of NVA (more than 2000 enemy soldiers). These aren’t VC or regional forces. It’s like swarming bees out there less than a mile from our perimeter.

The whole objective of the NVA is to control the area around Sherry by overrunning outpost Sara a short distance to the northeast, with the ultimate goal of taking LZ Betty (an administrative, military and logistics center south of Sherry on the coast).

You know we have superior airpower, but the 3/506 infantry is outnumbered three to one on the ground. And the maneuvering by their battalion commanders is spectacular. It’s the heaviest fighting the Currahees will encounter all year. Still we clean their clocks, and that has a lot to do with B Battery at LZ Sherry. It fires almost continuously during that period, sometimes all day and all night long. It shows the importance of what a 105 mm howitzer can do.

Danger Close

The commander of Delta Company is Captain Gerald Wrazen. He is a great company commander. He is on his second tour in Vietnam, and was an enlisted man for his first tour. Early on I tell Captain Wrazen I want to try something I learned in Hawaii.

Captain Jim Schlottman, who had fought at the battle of Ia Drang, shared with me a technique he learned from the NVA. He used the term belting. They belt you. The enemy gets as close as they can to you knowing that when they are close it neutralizes your ability to call in artillery because you’ll injure your own men.

I said to Captain Schlottman, “What do you do in those situations?”

He said, “That’s when you set up a false perimeter. You set up, you make a lot of noise, you leave trash laying around, and as soon as the sun sets you back up 50 or 60 yards. You wait until they come and when they hit your false perimeter you call the artillery in on top of them – HE (High Explosive) first round.

Now in Vietnam I’m still a new FO and Wrazen is pretty skeptical. He says, “We’ll see.”

When we set up our NDP (night defensive position) Wrazen wants me to register four targets on the cardinal directions. I say, “Captain Wrazen, that’s silly to do. Don’t you appreciate that if I fire four rounds north, south, east and west, you don’t think Charlie or the NVA’s gonna know we’re in the middle?”

He says, “You know Hank, I never thought of that before.”

I say, “Let me show you this.” I call B battery FDC at Sherry and give them four targets away from our position. I tell them I just want to show the company commander something. So they fire the four targets and no more than ten minutes later BA-ROOM, BA-ROOM, BA-ROOM. They mortar right in the center of those four rounds. So now Captain Wrazen gives some credence to what I’m saying.

That night as we’re setting up our position I call FDC back at Sherry with the coordinates for them to set a gun up for us. I say, “I want the base piece howitzer ready, one round, HE, and I want it fast when I call for it.” They say they’re not going to give me an HE on the first round. I say, “It’s a false perimeter, we’ll be away and off the target line.” They say as long as I call it in DANGER CLOSE they’ll do it. At this point I know the guns and I know the guys at B Battery, they know me, and I know they’ll fire for me. I was there the night of the ground attack and that means lot.

Then we set up the false perimeter. We make a lot of noise, leave a few cans laying around and then pull back about 100 yards. Early in the morning, around 2:00 AM, Charlie hits that perimeter and they open up with small arms fire. I call up FDC and right now I get one round of HE. BOOM. End of attack. Nails ‘em right there. All over. It is a total surprise to the enemy. They expect smoke, or illumination or white phosphorous. They don’t expect a first round HE.

So from that point on with our FDC and Captain Wrazen, if I want first round HE I get it. All I have to do is say DANGER CLOSE.

You see that one shot was fired off three digit grid coordinates, that was it – three digits east and three digits north from the grid coordinate. Again the importance of map reading and knowing where you are. What I do with Captain Wrazen when we’re on operations, I always make sure that the pilot takes us to where we were supposed to be. I learned my lesson at Green Valley. Then when we get on the ground and start maneuvering, my radio operator and I always count our paces off a known feature. I ask the infantry point man to do the same thing, and with Captain Wrazen we all have to agree on where we are within a couple yards.

Playing At Infantry

During this time two guys from the meteorological section up at Sandy are a little bored. So they go out to the trash dump to play infantry. They take their weapons and they want to kill some Charlie. They go out and they don’t return and are reported as missing. The infantry goes out to search and they find their three quarter ton truck but no sign of the met guys. They call for a search team with dogs and the dogs still don’t find them. Later their bodies are found decapitated.

“Who Won the World Series?”

We’re out on an operation, this time platoon sized (about 30 soldiers). We are on an air assault coming into a hot landing zone (taking fire from the ground). That is interesting because I’d already prepped the site with artillery and gunships. We’re going in and typically Captain Wrazen and I are in the lead helicopter. He’s out on the right skid and I’m on the left. You get on the skid when you’re on the final run into the LZ, so you can just hop off.

We’re over tall elephant grass and I’m on the skid. I don’t have an RTO (radio telephone operator who carries and operates the radio equipment). Wrazen won’t get me an RTO so I have to carry the thing myself. I’ve got the PRC 25 and two battery packs strapped on my back, and my weapon. For me that is a lot of weight.

When we start taking fire the helicopter banks left and up, which throws me off into the elephant grass. I hit with a thud that knocks the wind out of me, my steel pot goes flying, but I hold onto my M16, that’s another lesson I learned. My ears are ringing, I’m in a panic, and all I know is they’re gone and I’m the only one in this tall elephant grass. So I just start shooting, not on automatic – I learned this from the ARVNs – not to open up and empty a magazine. They had good fire discipline, knowing they only had so much ammo. I start shooting 360 degrees, a couple rounds each burst. Unknown to me the infantry had landed a few hundred yards off to my right, and they’re coming to get me. I’m still firing away and I hear this racket coming toward me. From the grass someone says, “Hank, stop shooting”

I say without even thinking, I guess from my basic training, “Who goes there?”

He say, “It’s me, Captain Wrazen.”

I say, “Who won the World Series?”

He says, “Hank, the World Series hasn’t been played yet. Stop shootin’ so we can get on with our mission.”

I am embarrassed. I grew up watching John Wayne and war movies. I’d watched enough movies that’s what I came out with. I was a Yankee fan and loved the World Series. But to be honest, I worked with some Vietnamese who spoke pretty good English. I knew Captain Wrazen but in a crisis situation like that, you’re in a panic, you revert back to your training.

The benefit of my getting thrown off the helicopter is that Captain Wrazen now realizes I need an RTO. So shortly I get my RTO and don’t have to carry the radio.

Still during this period I never know if my RTO is going to be with me or not, whether he’s going to drop the radio or have the SOI with him (Signal of Operating Instructions). Each day you go to your SOI and that gives you your radio call sign for that day (your handle). With all this going on I simply keep the call sign Joyful Orphan until I leave Vietnam. I don’t bother with the SOI because everybody knows me and knows my voice.

Combat Cross-Dressing

The next morning we do another combat assault. We are platoon size again and tromping through rice paddies. There are mama-sans planting rice. Out of nowhere I say to Captain Wrazen, “Those are not mama-sans planting rice.” Again this is something I had learned through observation in my time with the Vietnamese. I know what a mama-san planting rice looks like. These are not women squatting and planting rice. These are somebody else. We position, we engage and open fire. Now they come up men with AKs and we wipe them out. We do a search and we find their backpacks, where we find their uniforms and more women’s clothing. It was instinctive. I knew those were not women.

Napalm Up Close and Personal

In that area the enemy has tunnels and sophisticated bunker systems. We are pinned down by small arms fire, and artillery is not denting them. Captain Wrazen wants air support, so I call in the Air Force and we drop napalm. I had never dropped napalm before. These canisters come tumbling down, hitting the trees and bouncing all over the place bursting into flame. When they burst you immediately smell it and it sucks the air right out of the area. We were a little bit close, and when the platoon pulls back we don’t have hair on our arms or eyebrows.

When we get to the bunker complex we find the enemy burned to a crisp – in place and weapons in hand.

A Zippo To The Rescue

We are out on a clover leaf operation with a squad (about 10 soldiers). Typically an FO did not go out with a small unit, but I wanted to observe and learn from their tactics. We get out there and we spot a couple of VC. I think they are NVA. We follow them for about half a mile and we come under mortar, rocket and heavy weapons fire. To me that’s not a platoon of VC. The weaponry itself tells you you’ve encountered something much larger.

At that point I call in artillery from Sherry, I call in big guns from LZ Sandy, I then get the searchlights on Whiskey Mountain, and I call in gunships. They’ve got me pinned behind a rice paddy dike. My RTO falls and drops the radio, so the radio’s between him and me and there’s no way in hell he can get out to it because he’s pinned by the fire. I at least got the rice paddy dike, so I crawl back to get the radio and come back to the dike. I see the green tracers above me (every fifth round), and the fire is chewing down the dike, so I’m getting lower and lower. The gunships are overhead but they can’t tell who’s who. So I pull my Zippo lighter from my pocket, I light it and throw it over the dike and say to the pilot, “Can you see that?”

He says, “I see a flame.”

I say, “That’s it. They’re north of that flame.” It was just enough light to show the gunships where to fire. They fired and gave us enough cover to get back to our platoon in a safe area. I’ll always admire Zippo lighters because that sucker just burned and burned.

The next day I go out looking for that lighter and cannot find it. It had Snoopy on the lid, and engraved on the side was,

Yeah though I walk through the valley of death

I will fear no evil,

for I am the meanest son of a bitch in the valley.

I would have given anything to have found that lighter.

I say to Captain Wrazen, ”We were outnumbered and we were outgunned, yet they disappeared without a fight. That means something. I don’t know what it means, but something just isn’t right.”

We were just a squad against two battalions. They could have taken us on and chose not to. The reason they could disappear were the tunnel complexes. I mean this is 400 yards out from Sherry. There has to be something else going on.

Later I figure out the reason they did not want to engage us was that they were getting ready to hit Betty. If they took us on they were going to take on casualties and not be able to go after the larger target. In reality I don’t think they wanted Outpost Sara. It was a diversion so the main NVA force could position for an attack on Betty, which proved to be the case eleven days later.

September 17, 2014

Captain Hank Parker – Battery Commander – Part One

Captain Hank Parker

PART ONE

Captain Hank Parker served two tours in Vietnam. These stories in all their parts cover his first tour from November, 1968 to November, 1969. It was during this first four that he served with B Battery. Among the many awards and medals he earned on this tour are:

The Silver Star

Three Bronze Stars – two with “V” Device for Valor

The Air Medal

The Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Bronze Star

The Purple Heart

On his second tour he earned another Purple Heart and the Combat Infantry Badge.

When I got to Vietnam I served a long apprenticeship with the infantry before becoming XO and then battery commander of B Battery. I was an artillery forward observer (FO) on search-and-destroy missions with the Special Forces; and I went on airmobile operations with two South Vietnamese infantry battalions (ARVNs); and then accompanied the 3/506 airborne infantry as it took on two battalions of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). On one of my efficiency reports the battalion commander said that I’d become a seasoned combat officer. I think that is how I ultimately got to be battery commander at LZ Sherry as a first lieutenant.

Preparation in Hawaii

Before Vietnam it was significant that I did a tour in Hawaii with an artillery battalion attached to the 6th Infantry Division. The battery commanders were all seasoned Vietnam vets. My commanding officer was Captain James Schlottman, who had been a forward observer in the bitter fighting in the Ia Drang valley, portrayed in the book We Were Soldiers Once … and Young. He did not talk about Vietnam a lot, but when he did I listened. I used one of his lessons in Vietnam when I was out with the infantry – Delta Company of the 3/506 – and my guess it saved some lives. I was on a special artillery test team, where I practiced aerial observation for mobile artillery positions. By the time I got to Vietnam, what most guys had to learn in country, I already had.

First Things First

The brave person that I am, the first thing I do when I got to Vietnam is find a chapel and go to a service. I ask the priest if he has a rosary and he gives me one. It is in a plastic bag and I carry that rosary with me day in and day out. It never gets wet. I keep it in my breast pocket and it is with me the whole time. To me that is very important, because I had gone to a Catholic seminary for three years and religion is important to me. When I get into situations of life or death, what am I going to do? I want to make sure I am in an OK place with my faith and with my God. That’s the first thing I do when I got to Vietnam – make sure I am in an OK place.

I keep it in my breast pocket where I can touch it. The times when I am particularly scared I touch it for solace and to be reassured. It is a good way to ground myself. To make sure I stay in the here and now and make sure things are OK.

I am concerned mostly with the safety of everyone around me, that the decisions I make be logical, at the same time that I keep in mind my humanness and my compassion, and that I not go against my principles, my own beliefs. The rosary provides me that. It is my combat rosary.

I brought the rosary home and my daughter has it now.

I also carry a piece of paper in my wallet, which I still have and carry.

Hank leaves the room to retrieve his wallet.

Every morning I take this out and read it. It’s been with me all these years. It reminds me that whatever happens, he’ll see me through.

God does not promise skies always blue … but …

he does promise to see us through.

Special Forces

I’m assigned to B Battery out at LZ Sherry and I figure this is going to be my permanent assignment. I fly there from Phan Thiet where Captain Gilliam greets me. I dump my gear in a hooch, and then the XO introduces me around the battery. The place is busy, very hot, dusty, miserable, and nobody’s particularly interested in meeting a green first lieutenant. I go back to unpack my gear when they tell me not so fast. You’re going back to Phan Thiet to deploy with a Special Forces unit. And better yourself a rucksack because you’ll be living in the field. Beyond that nobody told me what I was supposed to be doing.

These SF guys are strac, everything in order, know their mission to a T. They do not seem to need me and I feel like dead weight. I fire a couple artillery missions with them, but go out mostly on pacification operations to the villages. I don’t think I’m learning a lot, but I am just by watching and hanging around these guys. That experience proves irreplaceable in terms of how I will later function in crisis situations in real combat.

I go to LZ Judy for about a week (firebase west of Sherry) as Assistant XO (executive officer) and Fire Direction Officer.

Then I convoy in APCs (armored personnel carriers) loaded with ammo to LZ Sandy (northeast of Sherry.) They’ve got the big guns, the 8” and 175 mm howitzers. I am put in charge of a single 105 mm howitzer on loan from Sherry to shoot illumination at night. I think, Okay, at least this is getting me closer to home, to my 105s that I know.

It begins to dawn on me I am also learning a little about the 8” and the 175 mm. I have the opportunity to learn all of the resources that are available to me when I am out in the field. The Army did not plan it that way, but that is how it is working out. When I start calling in fire the folks at Sandy are gonna know who Lt. Parker is, and I will also have confidence in them.

Out With the ARVNs

The missions I fired with the Special Forces impressed a major enough that he now wants me back. He sends me up to Song Mao with the 23rd ARVN division.

Lt. Parker Near Song Mao

When I get there I am shocked when I see my FO is one of my classmates: Rich DeSoto. This proves to be very fortuitous for me because there is not a better map reader than Rich. We are in dense triple canopy jungle, sometimes the sun cannot penetrate, and Rich always knows where he is. I watch how he does it and he teaches me. Whenever we take a break and whenever we stop, Rich has his compass and his map and he’s figuring, where am I? In that type of environment you don’t have the reference points we had in training. You can’t see a nearby mountain. We are maneuvering with battalion size elements (about 500 – 600 soldiers). When you have three companies clover-leafing you got to know where they are if you’re going to call in artillery. Because if you don’t, you’re going to hit them. Being an FO is 90% map reading.

On a maneuver with Rich the ARVNs have these chieu hoi, POWs and deserters who are now working for us. They wear the crappiest uniforms the ARVNs can give them They carry equipment, make fires, and cook for the troops. On one of our stops the chieu hoi are off in their own area. A unit of VC comes through and sees our chieu hoi and think they are ARVN deserters because of their lousy uniforms. So the VC sit down to have supper with them. Shortly into the meal they realize, oh my god, these are actually ARVNs, they are not deserters. Then the gunfire breaks out and we hear it and join in the action. It’s like keystone cops with people screaming and diving everywhere. In those close quarters, with the foliage and the density of the undergrowth, somehow nobody gets hurt.

Chieu Hoi

Years later I am in DC with Rich and another vet friend. We’re having dinner and drinks when Rich goes into the story about when he was out with the ARVNs. He says that all of a sudden he hears loud voices in Vietnamese arguing back and forth and he doesn’t know what’s going on but knows somebody’s not happy. Next thing, he says, there’s gunfire.

I break into his story and say, “Yea, we were duckin’ and takin’ cover, jeez there’s AK47 and M16 fire going back and forth.”

He says, “You weren’t there, you don’t know anything about that.”

I say, “Rich, I was there with you. I took your picture!”

“You were not.”

So I get my picture and show him doing his map reading in the jungle.

He says, “I remember that now. You were there.”

So he writes a book, Never a Hero, puts this escapade in, and puts the picture on the back cover.

Lt. DeSoto Studying His Map

Trung Úi Boom-Boom

I go out on another operation, not with Rich this time, and again I’m with a battalion size force. We load up in Chinook helicopters and away we go. I’ve got my map and compass and I know where we’re going. I have it already plotted and I have the radio frequencies for calling in fire. Everything’s great.

We’re in the air awhile and I know enough of where we are going to realize that we’re in the air too long. I get real uncomfortable. I say to the infantry officer on my chopper, “This cannot be where we’re going, we been in the air too long.”

We land and I can’t believe it. We’re in a beautiful, lush green valley. I bet there had not been people in that valley for hundreds of years. Beautiful. The companies form up and start to cloverleaf in the cardinal directions on search-and-destroy type missions. I’m the FO so I stay at the command post with the battalion officers.

The day before I had some Vietnamese food and it really didn’t settle well with me. Because of that I have a really bad case of the scoots. The old belly gurgles and I know I’m going to have a bout, so I charge out into the woods and find a relatively private spot. I drop my jungle fatigues and am in such a hurry not to ruin my pants that I put my M16 up against a tree. The diarrhea is painful and I break out into a sweat, but I don’t mess my pants and I’m feeling good about that.

I hear something and I look up and I see two North Vietnamese coming down the trail. And then it dawns on me this is a well traveled trail. These guys are smoking and laughing and chatting. They got their AK47s. Then I realize, oh my goodness I don’t have my rifle. It’s against the tree. As they proceed down the trail I think they may not see me but they’re definitely going to smell me. Sad to say, but that’s absolutely the case. It isn’t going to be that much longer and I have to decide what I am going to do. When they are directly in front of me I jump up and yell and at the same time grab my rifle and start firing, my pants still around my ankles. The funny part is they scream back and run up the trail as I’m shooting at them, probably spooked by a crazy man with no pants.

I immediately pull my pants up, fasten my belt, and I get back to the battalion CP. I say we need to get the hell out of here because we are not in the right area.

The Vietnamese battalion commander says, “Trung úi, pháo binh.”

I know trung úi means lieutenant, but I do not know what pháo binh means. I take a guess and say, “Boom-boom?” which is the closest sound I could make to suggest a howitzer firing. I don’t realize what boom-boom really means. It does not mean artillery.

He says, “Pháo binh.”

I come again with, “Boom-boom? Boom-boom?”

“Pháo binh! Pháo binh!”

When I figure out we both mean the same thing I call in a smoke round on where we’re supposed to be. Not only do I not see the smoke, I do not hear the report of the howitzer. Immediately I call for two more rounds of smoke. I neither see it, nor do I hear it. I say, “We need to get helicopters out of here, because we’re in a well traveled area by the NVA and don’t have any artillery support.” The ARVN battalion commander sets up a perimeter, calls the infantry back in and orders helicopters.

By the time the Chinooks land to pick us up the NVA have massed and are coming at us. We are just about loaded and as the ramps are coming up on the back of the Chinooks the NVA are trying to get on with us. We’re pushing them out and throwing them off as fast as they try to get on. It’s mayhem, a real cluster. Amazingly there’s no shooting, and at the end of it all nobody gets hurt.

There is a lot for me to think about on the way back. The two NVA coming down the trail were obviously raw recruits in spanking new uniforms and shiny new AK47s. A scream and a couple M16 bursts from a half-naked soldier shooed them away. Had we hit a seasoned NVA element, they would have brought us down with rockets, B40 Bangalores. We’d be gone. We were lucky we were battalion sized. With that many men maybe we had them outnumbered. Still why didn’t anyone fire his weapon when they came at us, including me? I conclude that basically soldiers do not want to die.

I also figure out how the helicopter pilots misread their maps. In that part of the mountains there are multiple parallel valleys and they just went down the wrong valley. That’s another lesson. Pilots don’t always know where they’re going. As the FO I should have known at all times. And when you touch the ground – another lesson from DeSoto – you always fire a marking smoke round to verify you’re where you’re supposed to be. I probably would have done that, but nature called and I had to go into the woods first.

In the ARVN forces there are tiers of soldiers. I am with a higher tier. These are not regional forces, or popular forces. These are trained soldiers, guys who want to be in the Army. They are good soldiers. Typically the officers speak pretty good English, and all have a good sense of humor. After that operation they give me the nickname Trung Úi Boom-Boom. I picture the battalion commander screaming in Vietnamese for artillery and me yelling back, “Sex? Sex?”

Alone on the Mountain

After we bring the battalion back from Green Valley I am out with another ARVN battalion whose commander does not want any contact. It’s what I call a search-and-avoid mission. We go out on patrol, do everything we can to stay away from the enemy, and at the end of the day go to the highest point we can find. On this night the highest point is the top of a mountain.

I had a nylon hammock, because the ARVNs slept in hammocks. I could not convince them the safest way to sleep in a hammock is to dig a hole, tie the hammock to two trees and let your body weight take you beneath ground level. The ARVNs lost a lot of men because of that. You get into a fire fight – it’s either Charlie or NVA that comes on you first – and they’d be sleeping above the ground and would take high casualties because of that. Instead the Vietnamese camp in stream beds, which is their way of getting below ground level.

During the night a typhoon hits. The rains are torrential, the wind is howling, and it’s miserably cold, jeez it’s cold. I lash myself to a tree with my hammock to keep from getting blown or washed off the mountain. I wrap the hammock around me and the tree. I’m sitting upright at the base of the tree. That way I’m secure while everyone else is sliding down the mountain, equipment and all. When the sun comes up I’m the only one left on the top of the mountain.

The entire battalion had slid down the mountain, all four sides of it. It takes us three days to reform, and then we go back to Song Mao to dry out. I think two to three ARVNs drowned.

Feet Flavored Rice

I eat at least four to five bowls of rice, while the average Vietnamese soldier has one. My strategy is if they cook it too long they burn the bottom. The Vietnamese will not eat burned rice but I will, I like it. Still they think I eat too much as a matter of cost. I have to start getting and carrying my own rice, which I pick up in Song Mao and carry in two boot socks around my neck.

September 10, 2014

The AWOL Bronze Star – Part Two

The AWOL Bronze Star

PART TWO

March 17, 2014

The VFW hall in Brighton, Michigan was packed. Andy’s wife Marsha, his sons Jeffrey and Justin, daughter Rachel and her husband Antinie, extended family, a seven-member honor guard, members of his church, friends, and eight B Battery veterans. Two of them – Tommy Mulvihill and Tony Bongi – were there the night of August 28.

The following is an excerpt from The Livingston County Daily Press & Argus

Vietnam vet recognized for

‘Michigan toughness’

U.S. Army Pfc. Andrew Kach, a Brighton Township resident, on Monday received the Bronze Star Medal with a “V” device for valor in a ceremony at the American Spirit Centre in Brighton Township.

U.S. Rep. Mike Rogers, R-Howell, presented Kach with his medal.

“The men I served with, every one of them bears the scars of serving their country at LZ Sherry,” Kach said after receiving his medal.

“Most people run from danger. They ran to it,” he added.

Kach served with the B-Battery Fifth of the 27th Artillery.

He explained that his unit, nicknamed both “The Professionals” and “The Bulls,” was under constant enemy attack during the war.

Eight members of Kach’s unit traveled from all over the country to see their comrade recognized for his service.