Ed Gaydos's Blog, page 17

February 2, 2014

George Moses – Battery Commander – Part Two

THE BOYS OF BATTERY B

GEORGE MOSES

BATTERY COMMANDER

PART TWO

Captain Moses spent the early months of his command tightening up battery procedures and overhauling the howitzers. The payoff for this hard work begins in December, 1967 with an operation in support of the Sky Soldiers of the 173rd Airborne.

“Oh How We Love You”

On December 5 we began the toughest operation of my tour in Vietnam. Ordinarily I would be leaving the battery at this time. The routine was six months in command and six months in a staff position. But there had been a change in policy that came out of the infantry accidentally firing on themselves with their own mortars and some of our artillery commanders firing accidentally on friendly troops. If you had a commander who had not had an incident, there was the option to keep him in command for a full year. Just before this operation Lieutenant Colonel House, who had replaced Lieutenant Colonel Munnelly as battalion commander, decided to leave me in command of B Battery. I was fine with that because I would have gone to a desk job somewhere.

We road marched the entire battery 80 miles south to Tuy Hoa and the next morning airlifted out to Landing Zone Clara where we settled in with a battalion of the 173rd separate infantry brigade, four companies of airborne infantry totaling about 500 men. On Christmas Eve, or maybe Christmas, Lieutenant Colonel House came out to have lunch with us and see how we were doing.

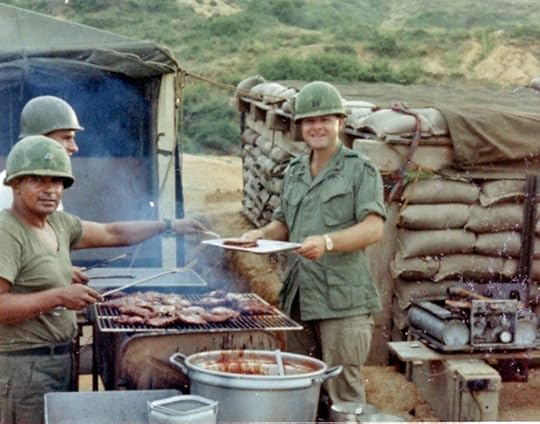

Captain Moses (left) and Lt. Colonel House Dining in High Style Christmas, 1967

I cannot resist interrupting Captain Moses to comment on this picture. “There’s a lot going on here. It shows the many uses of artillery ammo boxes, including the fancy table, and I see in the background your howitzer has its muzzle cover.”

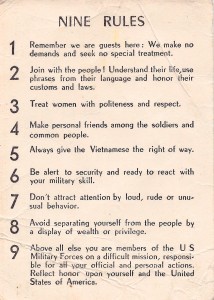

Oh my lord, we couldn’t have survived without the ammo boxes. We built everything. We built shower stalls, latrines; we put down flooring with the wood; troops would make small homes from them around their howitzers.

Shower at LZ Clara

The operation began on the 27th at 7:00 in the morning. Our orders were to airlift the entire battery, all six guns, to a landing zone 15 miles north near a Special Forces camp at Dong Tre. We were to lay the battery and immediately register on seven potential locations where the infantry might land. Three of the locations would be decoys, the other four would be actual landing sites and were known only to the infantry battalion commander. Our orders were to be prepared to fire preps on the actual landing sites, three to four minutes of continues artillery fire immediately prior to the landing of troops by helicopter.

Three days after the operation, on New Year’s Eve, Captain Moses wrote a letter from the field to his wife and daughter describing the action.

We had about 700 rounds pre-spotted at the new position and brought about 800 rounds with us. We fired two preps and everything went normal. We fired the third prep about 0905 hours and the company that went in (Alpha company) got hit hard. We continued firing and by eleven o’clock we were down to 820 rounds. By 1:00 we were down to 300 rounds and yelling and calling for more ammunition. A tactical emergency was declared and all Chinooks were made available to haul ammunition for us. By 2:00 we were down to 125 rounds and still going strong. By 3:00 we started getting more ammunition and the firing fell off. By nightfall we had 2600 rounds. By morning we were back (down) to 2000 rounds (bringing the total to well over 2,000 rounds in 22 hours of around the clock firing).

Alpha Company was pinned down for about three hours while we fired in and around their perimeter. That evening at dusk they found a total of 104 bodies around their position, and saw evidence that many more had been dragged away in the night. The men of A Company would have kissed every man in our battery because they knew we had saved their lives.

The operational tempo got very fast because we figured out a way to get rounds out more quickly in response to a correction from the forward observer. That was one of the criticisms we in the artillery got, that it took too long to get rounds out after corrections. I was listening to the corrections coming from the forward observer to the Fire Direction Center, I was tuned in on that frequency. I was able to give the 1st sergeant a heads-up on which way in general the corrections were going to come out – left, right, up, or down. So the guns could begin moving in those directions while the FDC calculated the precise firing information. By anticipating we were shorting the time to get the rounds back out there. That was a departure from FM 6-40, but I could see that it was making us more responsive and it worked quite well for us. That was the payoff for being a well trained artillery unit.

We had a mountain of ammunition boxes from that operation. If we had stayed in that position we could have built a castle.

We burned the paint off some of those tubes. That’s where all the maintenance that we did at Qui Nhon paid off. Not one of those howitzers hiccupped at all. It was the damnedest thing. Ever since then I’ve been in love with the 105 howitzer.

1st Sergeant Roy and Captain Moses – Picture taken mid-mission around noon

Lieutenant Kerchoff was my forward observer. He and the radio operator were inserted with Alpha company. Kerchoff did one hell of a job directing fire for that infantry company. He received a Bronze Star With V-Device for Valor for his actions in that operation. Boy he was a fine young man. Here’s a case where you certainly didn’t want to judge the book by the cover. When you looked at Kerchoff you’d say he would never do what he did on that Dong Tre operation. He did it in spades. He performed like he was trained to do, and with courage.

When he came to the battery, I have to admit he didn’t look like much and I was a little skeptical of him . Because of what he did on that operation, I have never again judged a man by the way he looked. He showed the kind of courage you would love to have in every soldier. He came back from that operation a bigger person and a tougher person because of that experience.

Captain Moses and Lieutenant Kerchoff

As I recall there were not any U.S. casualties. The brigadier general in charge of the brigade and the captain in charge of A company came down to the battery and went around and shook the hand of every soldier they could find, and thanked them for saving their ass that day.

Late the next night we were listening to Saigon radio, and the disc jockey said that the men of Alpha Company dedicate the following record to B Battery of the 5/27 artillery. The song was Oh How We Love You. I thought that was priceless. It was what field artillery is all about – the close trusting relationship between infantry and field artillery.

Good Shooters

In early January we were directed to an operation back up at Qui Nhon Bay for Major Wright, who was the liaison to the Vietnam Regional Forces. These were like their national guard and reserves, not ARVN regular army. It was a strange operation. The entrance to Qui Nhon Bay was formed by the tip of a peninsula that formed the harbor entrance. The Viet Cong had set up on a reverse slope of the peninsula, on the ocean side, a protected position that controlled the entrance to the bay. There had been a lot of activity there and the operation was to clean out the VC.

We set up our howitzers on a causeway on the inland side of the bay. We had to fire high angle over the crest of that peninsula onto the reverse slope. It was particularly stressful on the gun crews because they had to lower that tube to load a round, and then crank the tube back up to fire. Those cannons weighed 5,000 pounds and totally controlled with hand wheels. You had to turn that hand wheel lots and fast. By the time the day was over my boys were just shot. They were worn out.

I say, “Firing high angle onto a downslope is also tricky business.”

The battery was technically qualified to do that, and they did it very well. Fire direction center handled it well, the forward observers handled it well, and the crews did a marvelous job. I was very proud of them for their gunnery and their firing battery operation that day.

During the mission a colonel came down from Qui Nhon city and was just standing there. I saw him and walked over and reported to him and asked if I could do anything for him. He said, “No captain, I just came down here to smell the cordite.” I guess he was a staff guy and he missed being around the guns.

After that we continued to support Major Wright on more missions. He would go out with the Regional Forces platoons and call for what he called it reconnaissance fire. He would use the artillery to fire in front of him as he was moving. He was training his platoon to flush out anything in front of them that looked suspicious. If he was moving cross country and he came across a hedge row or clump of trees or something that looked suspicious, and he was concerned about getting ambushed, he would stop and call for fire on that point to see if it would flush out anything.

Wright came by the battery area after one of those operations and had some coffee with me. He said, “George, I’m not going to tell you how close we’re bringing that stuff in.”

I said, “As long as you tell me its danger close, that’s all I need to know.”

He kind of laughed. “Well, it’s that, and sometimes a little more.”

“Well, as long as you call it in danger close, that’s what our procedures call for.”

“We’ll do that. But your accuracy is so good that we are confident.”

I did not go into deeper conversation, but I trusted he knew what he was doing and what the risks were. I felt really good about that. Of course I passed that onto the battery, and that just motivated them more to be better at their gunnery. When he gave me danger close we went into the danger close procedures in the FDC, and we made damn sure that the guns were moving the hand wheels in the right direction and taking out slack. Major Wright was in love with the battery.

We were real good shooters, and stayed good until we had one incident. I’ll talk about that later.

January 28, 2014

George Moses – Battery Commander – Part One

THE BOYS OF BATTERY B

GEORGE MOSES

BATTERY COMMANDER

PART ONE

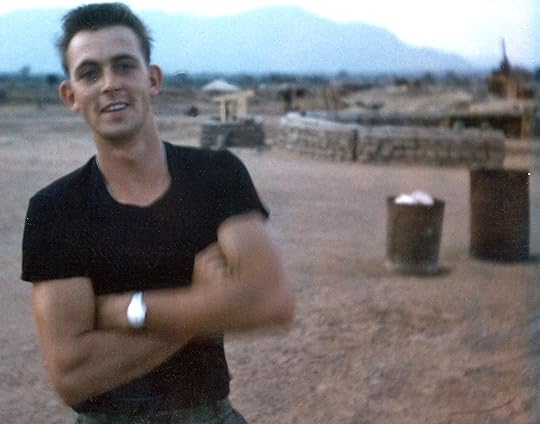

Captain Moses

Enjoying a Rare Treat With His Men in the Field

George Moses spent 20 years in the Army, retiring with the rank of full colonel. The path he took took to becoming commander of Battery B is a story in itself.

I was 29 when I went to Vietnam, a little older than the average bear. I graduated from high school three years behind, only one of which was my own fault. I was an October baby, so my mother held me back one year to let me mature socially. Then I contracted polio as a kid and was treated during the school year, and had to repeat the year. I put myself even further behind during junior high in Germany, where my father was stationed. I would get five dollars to buy breakfast, lunch and dinner at the school cafeteria. I discovered that for a dollar I could buy four marks twenty from the cab drivers, which would buy a lot of wiener schnitzel and beer. My buddies and I would go to the mountains, to the guest houses and have a ball. We got a different kind of education, but also skipped a lot of school. Then when the jig was up I had to repeat that year too.

After that failed year in Germany I got smart and really hunkered down and made very good grades. I came from a lower middle class family in Lawton, Oklahoma and I knew my parents were not going to be able to send me to college. In the motion pictures I had seen clips of cadets throwing their hats in the air. I said why don’t I look into that. I realized all you got to do is apply, there’s nothing to lose. My sweetheart’s father was an attorney in town, and I had a lot of people writing letters for me. Senator Robert Kerr ended giving me his primary appointment to West Point.

I will always be grateful. That was a blessing to me and I did all I could to live up to his expectations of me while I was there. I was 21 when I entered West Point, as old as you could possibly be. You could not be over 25 to graduate, so you had to get in within four years of that limit. I came out in the upper third of the class. Worked my ass off. I found out while I was up there that we’re not all built the same between the ears. Some were built differently than I am. But by working hard you can make up that difference.

I immediately went to Ft. Sill for the basic course in artillery and became a beady-eyed forward observer, but the Army sent me to Germany to a missile unit. So I started taking correspondence courses to keep up with the field artillery because I didn’t want to leave that branch, and I hoped eventually to command a battery somewhere. After Germany I went to Ft. Benning GA – I thought I would be going to Vietnam, – and worked for an infantry lieutenant colonel, Bertam J. Bishop, who turned out to be an old war horse. I had the privilege of working for Lt. Col. Bishop for one year and then rotated out to Vietnam. The lessons I learned from Bishop helped me in Vietnam, in my whole 20 year military career, and I know now throughout life.

Bishop tried to recruit me into the infantry. I told him I was a trained artilleryman and wanted to command a battery. But no, I got assigned to headquarters at Nha Trang in an administrative job, a housekeeping job, and eight to five job, and I was really sick over it.

The night before I was to report for duty I was at the officer’s club setting at the bar having a beer. There was another captain there, a bright guy, with a Ph.D. He had served down at Ft. Bliss at one of those highly technical outfits at the Air Defense school where they studied strategy and weapon systems design. He had been there his whole career. He was assigned to the 5/27th artillery, which was exactly where I wanted to go. He was scared to death about going to a cannon battalion. He was not afraid of the danger so much as he just did not know anything about artillery.

I was full of piss and vinegar and said, “Listen man, I know all anybody needs to know about a cannon battery, but I detest being a headquarters company commander. Would you like that job?”

He said, “I’d love that job.”

I said, “Listen friend, we’re gonna make a deal. Let’s go see the Personnel Officer together tomorrow.” The next morning we pleaded our case, and he said, “Guys, I’m in agreement with you, but to make it happen for sure I need to check with some people.”

Well it worked out and we made the switch and I was so relieved. I was blessed to have that situation develop. I went to join Lieutenant Colonel Munnelly at the 5th/ 27th in Tuy Hoa. When Lt. Col. Munnelly asked me what I wanted to do I said, “Sir, I want to command one of your firing batteries.”

He said, “You think you can handle that?”

I said, “Sir, I know I can handle that.”

He said, “Well, right now I’m going to make you battalion motor officer.”

(Laughs) I didn’t say anything other than, “I’ll be the best one you ever had.”

I went to work and shortly Lt. Col. Munnelly came to me and said, “George, I’m going to put you in B Battery to take Captain Marchesseault’s place. I want you to take command on the 1st of July.” That made my day. I discovered through my career in the Army that if you want to command, if you want to progress, you got to seek it. You got to do all you can to make it happen. It just doesn’t happen. Everyone is seeking those command jobs. After you go to the basic course and they teach you that stuff, you want to go do it.

Muzzle Covers

When I took command B Battery was outside Qui Nhon, about 80 miles north of Tuy Hoa, and it had been there a long time. The mess tent even had wooden floors. The battery had a daily routine going and I could tell there was a lot of spirit there. Everyone gladly did their work. There were details to be done every day, and they got it done. Setting that aside, after I was there awhile I noticed that in the FDC the fire commands were given rather loosely and the gunnery was sloppy. Some of the elements of the fire mission were out of order. Procedures were fraught with confusion, a real problem if we really got into a tough operation. During the change of command with Captain Marchesseault I asked him, “Paul, what do I need to know about?” He expressed to me exactly what I was seeing, that things were getting rusty.

When I served with Lieutenant Colonel Bishop, my commanding officer at Ft. Benning, I learned it was easier to be a hard ass and let up, than it was to be an easy commander and then become a hard ass. The latter way engenders a lot of resentment. One of the first things I did, after about two weeks, I went into the battery Fire Direction Center and I took out the FM 6-40, the artillery field gunnery manual, and I said, “Gentlemen, I want everything in this FDC to be done in accordance with this manual with regard to calls for fire, interactions with the forward observers and the manner in which commands are given to the guns. This manual is the evolution of decades and decades of artillery procedure, and this has been proven to be the best way of doing it. If you think you’ve got a better way you come talk to me, but until then this is what you operate by.” I did the same thing with the howitzer sections, I told them everything was to be done according to the book.

None of the howitzers had muzzle covers when I got there. A couple of them had a coffee can over the end of the muzzle. I said, “The reason you don’t have muzzle covers is you shoot ‘em off. The reason you shoot ‘em off is you don’t have the discipline that makes sure the first step in a fire mission is to take your muzzle cover off. That tells me there’s a lot of other things you may not be doing. I expect your service of the piece to be by the book.” I said to the section sergeants, “We don’t have a chief of firing battery, but we do have a battery exec, and I expect him to hold you accountable to execute service of the piece in accordance with the book. There may come a time when things are so hasty and so wild that you can’t quite do it in order to get the job done, but until then I expect to see you do it by the book.”

And they did. It wasn’t long before there were muzzle covers on every one of those howitzers. One morning I remember going out after a night of H&I and one of the howitzers did not have a muzzle cover on it. I went down and asked the section chief, I said, “Chief, where’s your muzzle cover?’

He just looked at me and said, “Sir, we don’t have one.”

I said, “You shot it off last night.”

He looked at me and he said, “Yes sir.”

I said, “Get another one, and don’t shoot it off.”

I watched everyone closely for about six weeks and corrected everything I could find, and boy they responded. The FDC got very sharp, and similarly with the service of the pieces. I was really proud of them. By the way, you’ll see in a lot of my pictures when those howitzers weren’t firing there were muzzle covers on the ends of those tubes.

The howitzers at that time had seen a lot of action and required maintenance that we could not do. For example the hand wheels had a lot of play in them, a repair that required a maintenance depot. There was a large quartermaster base inland from where we were and I sent the motor sergeant down there to see if we couldn’t talk them into taking our howitzers in one at a time and overhaul them. I didn’t like to tell everybody this, but I used to go into Qui Nhon to the PX and buy a couple bottles of bourbon. The motor sergeant would take them when he went over to the depot. I think that was the ticket to getting the howitzers overhauled. We rotated them all through there. It was a good thing we did, because getting the howitzers in first class condition and putting all our procedures in place later paid off in spades during an operation down south with the 173rd Airborne Infantry, the biggest and most demanding of my tour in Vietnam.

Personal Feud

It was toward the end of July, just a few weeks into my command, about 10 at night. We heard a lot of small arms fire going on. The Korean mortar section started firing illumination rounds, and they couldn’t see anything, couldn’t find any targets. That small arms fire went on for about two hours that night. It was a great mystery. Finally the next morning I got ahold of Major Wright, the district advisor. It turned out that about 700 meters off to the right of the battery, looking to the north, there were two Vietnamese Army platoons. The officers of which were mad at each other and were shooting at each other. The platoon leader who started it was prosecuted and put in jail. That was an eye-opener for me. Their army was not as unified as we thought it was. I could not imagine that going on, but I’m sure it was not the only case where that happened. It turned out to be a personal thing. I guess their senior commander let it get out of hand, and that’s the way it was resolved. They were located in villages. And these two villages started shooting at each other.

The Pills

It was around the middle of August that we got the word to start taking these pills. One was primaquine and another one called dapsone that you were supposed to take daily. They gave me stomach cramps like hell. I asked the medic what in the hell they were for, and he said one’s for malaria and the other one’s for leprosy. I said, “Make damn sure we don’t run out of that one for leprosy.”

Don’t Mess With The Koreans

The battery’s mission at Qui Nhon was general support of the South Korean Tiger Division. We were set up on the side of a hill, and there was a Korean mortar platoon on the hill top behind us to act as our security. And I had a radio relay station up there. The Koreans would fire illumination rounds randomly at night, and if they saw anything moving outside our wire, they just mortared the hell out of it.

One morning my mess sergeant came to me and said that one of the Korean illumination canisters had dropped into the mess tent. (When an illumination round bursts in the air its canister keeps going, so you’ve got to worry about where it lands.) It was laying on the ground there in the mess tent. When I called the Korean platoon leader down, he just looked at it and didn’t say anything. I kept saying, “Mortar crew made mistake.”

He finally said, “No mistake … no mistake.” He would not admit that they were responsible.

Our relay section the next morning called me on the land line and said, “Sir, something is going on up here.” Every morning these Koreans would fall out and do these Tae Kwon Do exercises in mass formation. You could hear them up there yelling. My relay section said, “They didn’t exercise this morning. Their lieutenant chewed a couple soldiers out and then took a rubber hose and beat them into the ground.”

I said, “You stay away from it, and don’t say a word to anybody, shut your mouth, and don’t even look.” I thought to myself, he may not have admitted there was a mistake but he certainly disciplined somebody for it. The commanding generals of those divisions had summary execution authority for their soldiers.

Sergeant Joe Mullins, a gun crew chief, and Captain Marchesseault relate an earlier incident involving the Koreans on the hill.

PAUL MARCHESSEAULT:

I sent a detail east over to the coast to fill sandbags. It was the nearest available beach. They were coming back with a deuce and a half full of sandbags. And Laster, my jeep driver, was in the back of one of the trucks. They saw a guy up on a hill who was a Korean aiming at them. He fired a shot that hit Laster’s canteen. They turned a corner out of this guy’s line of sight and came back to the battery all excited.

JOE MULLINS:

We’re on our way back from filling sandbags, I’m settin between Captain Marchesseault’s driver and another guy. We heard a rifle fire. We didn’t hear anything else, no bang or ping or anything. It think it was when we got to our location that he picked his web gear up and his canteen was leaking and it had a hole in it.

PAUL MARCHESSEAULT:

I remember looking at the canteen. It was one of those green plastic ones. The hole wasn’t very big and I said, “What was this?” The guys thought that he had a carbine. I said, “Wait a minute.” We threw the canteen down on the ground and I fired my M16 through it, and it made a much smaller hole. So it had to be a larger caliber weapon. It went right through the canteen, which was on his hip, and missed him.

I sent Malone and Laster over to the Korean compound to complain to the commander. The Korean commander called a bunch of guys in who were on guard duty and had them standing at attention in front of him and was questioning them. He finally got the one guy who fired the shot and he hauls off and slugs him in the face. The guy fell down on the ground. The guy sat up and he hit him again. Then they took him off like they were going to take him to jail. I guess the guy didn’t like Americans.

JOE MULLINS:

I remember that Korean compound. It was a pretty good size. We was basically mixed in with them, about as close as you can get. They were just a little higher on the hill from us, and we was down at the base. Them guys knew the Tae Kwon Do and did it every day. They had the wood poles that they flipped around. I set there and watched them do that stuff a bunch of times. If I could understand what they were saying I’d a got down there and joined em. They trained tough, I can tell you that.

I know one thing, their officers didn’t put up with no bull. The officers of the South Korean Army didn’t play no games with their soldiers. I seen em have one in the pushup position, and that lieutenant took his swagger stick and he beat the doggone tar out of him. I was afraid to look.

I felt good when we was around them Koreans. I know one thing about them, the North Vietnamese was scared to death of em. I think that’s what kept us not getting mortared or trying to get overrun so much when we was up there north of Qui Nhon, because of the South Koreans.

South Koreans at Early Morning Drill

Courtesy Joe Mullins

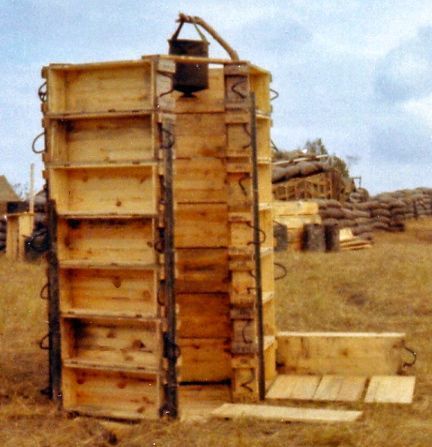

An Enduring Memory

As a battery commander I took my job seriously and was always looking after the welfare of the troops. One of the things you had to do was make sure you got rid of all the human waste. You couldn’t be digging slit trenches everywhere, otherwise you’d had the whole damn battery littered with open and closed trench latrines. The procedure that was used to get rid of the waste was to cut a 55 gallon drum in half, pour in diesel fuel, and build an outhouse over it with ammo boxes. You were lucky if you had a two-holer, and really lucky if you had a four-holer. We’d give the battery medic a detail every morning to pull out those half barrels, pour in more diesel fuel, then set them on fire and burn the waste.

Our battery medic was a fine young man. I can’t remember his name. I remember when he was leaving I talked to him at some length. He was going to school back east to get a degree. He said, “You know captain, this has been a great experience for me.”

I said, “What do you remember most about it?”

“What I remember most – I’m going to tell all my friends when I get home when they ask me what I did in Vietnam, I’m going to tell them, ‘I saw more shit.’”

“You going to let them take that figuratively or literally?”

“I’m not going to say anything after that.”

A Kick in the Ass

I noticed a gun section one night at dusk lined up in rigid military attention in front of their howitzer. On a command from the section chief they all kicked their right foot into the air vigorously and emitted a loud, EEEAAAH. I went to the section chief and said, “What’s going on there, chief?”

He said, “Sir, we have just kicked another Vietnam day in the ass.”

January 22, 2014

Leo Ward – Gun Crew

The Boys of Battery B

Leo Ward

Gun Crew

Leo served in Vietnam for 18 months, two tours with B Battery. Forty years after returning home, Vietnam reached out and touched him again.

I was a gunner on gun pit 5. We were just a bunch of ol’ crazy country boys.

When we were at Qui Nhon, they dispatched me to the water truck one day, me and another guy riding the shotgun. We had to go into the city to get water, and on the way back to the battery area I had a wreck with one of those three-wheeled Lambrettas. You know how they loaded them things up with ARVNs and civilians and what have you. He cut right into me and my front wheels caught the lip on the fender on the front of it and just sent it rolling and flying through the air. Stuff was flying everywhere – people, bodies and stuff. Captain Moses, the battery commander, gave me an Article 15 punishment. I guess he had to do it on account of the village officials.

Loaded Lambretta

Five years ago I contacted Captain Moses to write me a letter for my VA benefits. He’s a full bird colonel now at Ft. Sill. He wrote me a letter about it, and told me I had killed a little four year old boy. It really broke my heart. I mean I just set and cried. That was one of the worse things that happened to me over there.

“You were 21 years old at the time. Maybe it’s a good thing you didn’t know.”

Probably so.

Returning home after over a year and a half in the field, Leo looked forward to a luxurious trip on the Freedom Bird, attended by comely stewardesses. It was not to be.

There was no commercial flight out of Cam Ranh so I had to take a military flight, one of them cargo jets with the old sling seats along the wall. I ‘bout froze to death.

Leo describes his life today in a few sentences.

I’m 66. I work for CSX railroad. Been there 37 years. I’m drawing Social Security, a VA pension, working every day. People say, man when you gonna quit? I say why would I want to quit? I make good money and I’m in tip-top shape. Strong as a bull.

January 21, 2014

Win a Self-Publishing Package

Are you a writer? Ever thought about self-publishing your book?

Here’s your chance to win a complete self-publishing package (valued at $1,749) from Columbus Publishing Lab for free! The package includes editing, design and distribution of your book! Learn more about the giveaway here.

Here’s your chance to win a complete self-publishing package (valued at $1,749) from Columbus Publishing Lab for free! The package includes editing, design and distribution of your book! Learn more about the giveaway here.

Columbus Publishing Lab is a new service that combines the professional editors, designers and consultants of Columbus Press (the publisher of Seven in a Jeep) and Columbus Creative Cooperative, and provides the same professional publishing services to authors.

If you’ve seen a copy of Seven in a Jeep, print or e-book, you know that it’s great work. From editing to design, it’s done right. Now the same professionals who put this great book together are also available to you.

The giveaway ends on Friday, January 24, 2014. So get over there and check it out. Details.

January 15, 2014

Bob Selig – Part Three

The Boys of Battery B

Bob Selig

Commo Sergeant

PART THREE

The Throne

I can remember at B battery the officers and NCOs being awarded medals, but never any of the enlisted guys. When I was back in Vietnam in ’69 – ’70 with the infantry, you went above and beyond you got a medal. They watched out and made sure that if you were on a career track, you got your medal. We were on a first name basis with the captains and commanding officers. We were family. I cared about them just as much as they cared about me. After Nam I was invited to one of my CO’s homes, Captain Franz, for dinner with his family at Fort Benning.

B battery was a totally, totally different environment. The officers had their clique, the NCOs had their clique, and the enlisted guys were left to themselves. At the time I did not know who the battery commander was, we reported to the Commo Chief and did not get past him. There was a distance, as far as meeting any of the company officers or talking with them, never!

Officers even had their own latrine, which we enlisted guys built for them. Normally we built them an ordinary latrine. We’d put the piss tubes out and then build a seat out of ammo boxes and slide the bottom part of a 55 gallon drum underneath. On one occasion we decided that we would build the officers something special. Before anyone knew what was going on, we had built a commode that was five feet high and had steps to get up to it. It was a throne! They had to go up four or five steps to sit on it. And it was out in the open in a position that we were being sniped at. The brass was good about it and used it, doing their duty high up and in the open looking down on the troops. A couple officers would only use it at night, guess they wanted privacy.

Ka-Boom

In the field we would burn the latrine drums out with diesel fuel and powder bags left over from fire missions. We were near the Laotian border, or maybe over it. One day a soldier was sitting on the latrine smoking a cigarette, and he threw the lit butt into the can. Apparently there was a left over powder bag down below and it went off. I never knew the soldier but I watched as they carted him off on the stretcher face down to a medevac helicopter. God knows I think of that poor guy to this day and hope he recovered, as he never came back to the battery.

Lucky

Of the ten boys of battery B who died, three were killed by mines while on truck convoy.

I remember going into headquarters at Tuy Hoa for supplies. It’s eight o’clock in the morning. We get out on the dirt road and we’re in a deuce-and-a-half truck. I’m standing just behind the two exhaust pipes sticking up behind the cab. We’re riding along this road about two miles from B battery and for some strange reason the road was deserted. That should have been a big tipoff. Typically this road was busy with farmers hauling their rice and walking their buffalo. All of a sudden there was an explosion with black smoke and I saw a rear tire go flying. The truck must have bounced in the air about four feet, because it threw me from the back end up towards the front and I burned my forearm on the exhaust pipe. We had hit a mine. We took cover and called for help. About 30 minutes later a minesweeping team made their way to us and took us back to the battery.

I think that we were extremely lucky. When we laid commo line or to get supplies we went out in jeeps all the time. Later on they started doing mine sweeping, but in the beginning we just didn’t think about it.

Mojo

B battery was my first experience of racism. Growing up in Arlington, Ohio you didn’t experience racism. This incident was toward the end of my tour with B battery, within the last three months. Up until then I had not experienced any racism in the battery. We didn’t have it. We had three different black guys in Commo. This one guy – a wonderful guy – we called him Mojo. Everybody had a nickname. They called me Tree, for tree-so-sin, Vietnamese for baby-san, because I was the youngest in the group.

It occurred in the mess hall. A particular gun sergeant was an alcoholic and he had been drinking. When Mojo came into the mess tent he went to sit down at the same table and this sergeant called him the N word. And of course a person is going to get upset. Oh boy, Mojo was big and was going to kill him. The sergeant was bigger than Mojo, but he was drunk. We manhandled Mojo out of the tent, got him back to our Commo section to cool him off, and got it under control. I went to First Sergeant Shepherd, and I let loose and told him, “You need to fuckin’ control your NCOs. This is bullshit.” I was pretty pissed off about that. That was my first experience of racism and it kind of shocked me.

[image error]

Washington “Mojo” Lewis

Courtesy Leonard Laster

The second time I went to Vietnam in 69-70, my god was there a problem with racism, not in the field, but in headquarters. A black guy came out at lunch with his M16 and he was going to wipe out everyone in the mess tent. I was over at a nearby tent looking at all the chaos going on at the mess tent. A major was standing there and said to me, “Go down there and take that gun away from him.” I didn’t want to, but I was a staff sergeant at the time. I had to go down and talk this guy out of his gun …with the gun pointing at me. I thought, Son of a bitch, I don’t need this.

War Is Hell

Another time we were in the field – a silly statement, we were always in the field – medics along with Captain Greene, the battalion doctor, came to administer GG (gam globulin) shots. At that time we got them every six months, one in each cheek, with a needle that had to be unusually thick for some reason. We would line up, drop ’em, and medics on each side would deliver simultaneous shots. Well, poor PFC Danus was afraid of needles and tried to talk his way out of it. The medics finally coaxed him to drop his drawers, and quick hit both cheeks. Danus takes off like a rocket running with his pants down and the needles still sticking in his buttocks like two darts. They were bouncing up and down like in a cartoon. The medics took out after him to get their needles back and tackled him before he got to Hanoi.

Sneak Attack

One day we were on recon choosing a site for the battery. There was this area the commanding officer found, but there were a couple straw huts that would be close to our perimeter. They’re made out of grass or straw. Everybody is gone. I remember going in to this one larger than normal hooch to clear it and in one corner there was a ladder going up to a makeshift open attic. Whenever I look up my tendency is to drop my lower jaw. As I gazed up the ladder to the attic a lizard jumped down from the attic and into my open mouth. You can imagine the spectacle that took place next, spitting, heart pounding, screaming, cursing, blood pressure through the roof, and probably a stain in the shorts.

“Maybe it was a Viet Cong lizard.”

The story ends well. I was fortunate to find a crossbow and quiver in the attic that I was allowed to bring home as a souvenir.

Booster Engines

On a mission to either Bong Son or Song Cau we were stopped on a road while convoying to our position. Everybody is sitting on the top of the gear and ammo on the vehicles, like a bunch of gypsies. We are chatting away as usual and all of a sudden a jet fighter without any warning flew overhead the length of our convoy – some swore it was only ten feet above us. As it reached the front of the convoy it darted up and threw on its after burners. It was the loudest, most awe-inspiring sound I had ever experienced. The guys shot up from where they were sitting and cheered and waved. Now that was a morale booster.

A Brief Crossroad

Many of us talked about our aspirations after Vietnam: going to school, buying muscle cars or sports cars, getting married, or just getting home safely. I fulfilled my dream with a 1967 Austin-Healey 3000 MKIII. PFC Torres from Los Angles was going to have many babies so they could work and support him when he decided to retire. But we had one big thing in common. We were all brothers and stood by each other through thick and thin. Even though you knew you would probably never see them again after leaving, you loved, respected, and supported them during this brief crossroad in life.

After the military Bob earned a place in modern history when he helped to develop centralized ad serving technology that displays advertising banners that pop-up on computer screens. He says in his own defense with a small laugh, “If I hadn’t, someone else would have.”

January 8, 2014

Bob Selig – Part Two

The Boys of Battery B

Robert Selig

Commo Sergeant

PART TWO

Ten boys of battery B would die in Vietnam. The first was 19 year-old Bobby Joe Marsh, in Vietnam less than a month. I ask Bob if he knew Marsh.

Yes I did. He wasn’t with the battery long. I had talked to him and welcomed him to the battery. There was not enough time to really get to know the guy.

I remember the night we got hit. The way the battery was set up, everybody was in tents. Except for the Commo section. We had a very good section leader, because we were set up in little two-man hooches with sandbag walls. The sandbags were four or five high and came up to where your bunk was, and then you stretched your poncho liner over the top. And you could still roll off your bunk and have minimal cover.

It was just after midnight. I was in a hooch with Larry Orson, a cook. I’m sleeping and I’m hearing explosions. Well, the guns fired at various times during the night, they had fire missions, or they’d be shooting H&I. So you’re laying there and you hear an explosion go off, and you think OK, another fire mission or whatever. But it wasn’t the whole battery firing. It was like one explosion at a time. But you’re not awake enough to realize that.

All of a sudden an explosion went off right outside our little hooch, and Orson and I were thrown on the ground between our cots. I hear this sprinkling in the trees, like it’s raining. Orson yelled “I’m hit, we’re being mortared.” The Viet Cong were walking the mortars over us.

At that point I was deafened. The two of us kind of grabbed each other and made it out to a fox hole that we had dug earlier. As my hearing came back I’m hearing screams, I’m hearing moaning, not from one person but from several people. I’m thinking we’re fucked, we’re gonna be overrun. We’re sitting in this foxhole and trying to get as low to the ground as we possibly can. The fox hole was probably four feet deep, so we were able to sit down in it. But you don’t know when the next one’s going to hit, because they are still going off. I’m just sitting there. Jesus Christ, when’s one going to come right in this hole and kill us? Yet we kept our cool and watched for VC to jump up from nowhere to attack us. We heard several more explosions from the incoming. Soldiers were yelling, we heard more screaming and moaning from the wounded.

I don’t know how many mortars came in. Because of gun noise and being half asleep, it was a terrifying situation. I helped get Larry to a medevac helicopter. They took out 12 wounded guys that night. I don’t believe they evacuated Bobby Marsh’s body that night. I vaguely remember it was the next day before they got his body out.

After I had gotten Larry onto the chopper I went back to one of the gun sections and – I’m still dazed, and I knew nothing about guns – I believe it was at gun 2 - they were firing and I just started helping them. They’re calling out different rounds and different charges. I’m a Commo guy, I don’t know one round from another and I’m trying to help them. Then they saw I didn’t know what I’m doing and said, “Whoa, wait, you can’t do that.”

Of course we were sweating from all the excitement, but my head felt wetter than normal. I touched it and it hurt. It was dark and I didn’t see anything. I asked the gunnery sergeant to look at my head. He turned his flashlight on me and the first thing out of his mouth was, “Medic!” I had blood all over. They got me over to the medic and Doc pulled a small piece of shrapnel from my head.

The next day they evacuated me by jeep back to headquarters at Tuy Hoa. The medical officer there was a captain, Afro-American; his name was Captain Greene. Nice fellow, gave me a tetanus shot, butterflied the wound, and bandaged the entire top of my head. Man, did I ever get stares from all the HQ folks. They let me spend two days at Tuy Hoa, and sent me back to the unit. I found out later that the guys that got medevaced out went to Nha Trang, and because the hospital there was full of casualties everyone got shipped off to Japan for a minimum of 30 days. Only about six came back to the unit. Because I didn’t know I was wounded, I missed out on a free 30 day R&R.

Later we were in the field and General Westmoreland flew out. He started pinning the Purple Hearts on everybody. I’ll never forget, he came up, he pinned it on, he shook my hand and he said, “Congratulations.” I walked away after the ceremony thinking what the fuck was that all about? Congratulations for what? Being alive? What the hell’s he talking about? Congratulations. I just could not understand that. Now I know what he meant, but as a kid I had to think about it. I’ve never forgotten that moment.

And I think back to people sleeping in tents, and people walking around in white tee shirts. What the hell was the brass thinking? West Pointers – they were there looking out for their careers, not looking out for the troops. We all learned from mistakes; no one really knew how to engage an enemy in the jungles of Vietnam. Too bad we didn’t learn sooner that we would not liberate the South Vietnamese.

Picture Taken Shortly Before March 6, 1966 Attack

Courtesy John Santini

I had worse experiences on my second tour. What happened that night in battery B got me set up for the future. The main thing I remember from that night is sitting in that fox hole, listening to all the agony, the choppers that were coming in and picking up wounded soldiers. I’ll tell you, the agony, the pain that you heard in the air, it was blood curdling. It made the hair on your head stand up. Terrible, terrible experience. That screwed me up … that screwed me up. After that I became numb to it. It got easier, unfortunately it got easier, But it really helped me in ’69 and ’70 on my second tour.

Fifteen months after Bobby Joe Marsh died, the base camp at Tuy Hoa was named Camp Marsh in his memory, Lt. Col. John Munnelly presiding.

Just Nod

I always enjoyed the chaplain coming to the field. I attended parochial school for eight years, and like my ancestors before me, once the eight years were up I no longer practiced. After I was wounded I visited the chaplain. Of course he twisted my arm and coerced me into going to confession. Well right after saying, “Bless me father it has been several years since my last confession”, he said, “Hold it right their, son, and let me help you”. He said “I’m going to say the Ten Commandments one at a time and you tell me if you have broken it. Just nod your head” I nodded my head a helluva lot more times than I’d like to admit. This guy was great. He let me off light with three Hail Mary’s, and he always looked me up before service when he visited the battery. Guess his blessings helped, I’m here to tell you about it today.

January 6, 2014

A Tremendous 2013 – Thank You!

On behalf of Columbus Press, thank you to all of the readers who supported Seven in a Jeep in 2013. You’re a fantastic bunch of people!

Seven in a Jeep was the first title produced by Columbus Press. Independent publishing is no cake walk, and your readership is a tremendous encouragement.

Thank you for supporting independent publishing and great authors like Ed Gaydos in 2013. With your help, we’re looking forward to another fantastic year!

December 18, 2013

Bob Selig – Part One

The Boys of Battery B

Robert Selig

Commo Sergeant

PART ONE

Staff Sergeant Selig

Second Vietnam Tour

Bob spent over eight years in the Army, including two tours in Vietnam. The first was with B battery for over a year and a half. He arrived in December of 1965, when the battery had been in Vietnam for less than two months and when it was still learning how to fight … and keep guys alive. Bob returned to Vietnam in 1969 with the 11th Light Infantry Brigade, where he says he “experienced much death and devastation.” For years he tried to forget Vietnam. Then on May 8, 2007 he wrote a letter to his old battery commander, Captain Paul Marchesseault, and that began a cascade of memories.

I blocked my memories for so many years. My wife still wakes me out of nightmares. It has only been recently that I can face the demons and put it all in perspective. I think what helped was about eight years ago my wife and daughter dragged me to the traveling wall where I wept profusely. I returned to the wall two weeks ago and it has allowed me to finally take control and attempt to bring the memories back. I feel really good about it.

I Remember

After arriving in country in ‘65 I was shipped to Phan Rang, issued a very rusty M-14 rifle, and then choppered to B battery in the field. I remember scrambling to clean my rifle on the chopper, as I had no idea where or what I was getting into.

Some of the best times in B battery were sitting around chit chatting with the guys and learning about them.

Baby Cakes, an African American, used to talk about riding around the roads back home in his red convertible feeling the wind flow through his kinky hair. He was in love with it. He was a gentle and kind human being that I will never forget.

I remember First Sergeant Shepherd, had a lot of respect for him. He was always there when I needed him.

There was Hedron, our company clerk, from Canada that lived on a ranch.

I remember Smokey; he was quite a character, definitely a take-charge soldier.

Wasn’t Grumpy Craig in charge of the motor pool?

I remember Lt. Colonel John Munnelly, but never had any face to face with him.

Michael Bell from Columbus, OH would keep us entertained with his imitations of James Brown.

Specialist 4 Young talked of nothing but his beautiful wife waiting for him in Tacoma.

Sergeant Wing from Arizona, had it not been for him being at HQ for the day, would have won the battery mustache contest with his bright red handlebar.

Scottie was from Bonegap, Il. We would entertain him with a little ditty we made up about “Go’n back to Bonegap”.

There was Sacko from a farm in Ohio. He was proud of his ‘64 purple T-bird that he had performed some kind of chemical process to all the chrome and made it gold. My god, it was atrocious!

Archie Clark from Brooklyn was always the clown with that strong NY accent.

Straus and Fause enlisted together and I believe were related by a marriage to a sister. The two were inseparable.

Dave Eves was the original commanding officer’s jeep driver, and later a member of the FO team.

Lieutenant Jim Walker from my home town turned into a banker. I visited him at my parent’s bank when I returned home and made him change a twenty for me. He looked so different sitting behind a desk and wearing a dark blue suit. He was a good guy.

Then of course there was Stretch. We were bathing in a stream one day and someone yelled, “Oh hell, this place is full of leeches.” We had leeches all over our legs, and one fellow had one about four inches long on his scrotum. He got part of the leech loose and was pulling on it trying to get it off. Leeches are like rubber bands, they stretch beyond belief. And a man’s scrotum can be stretched just as far! Swear to god, each stretched a foot. We called him Stretch after that.

I remember supporting the Korean Tiger Division. Couldn’t get supplied and ate Spam for two weeks, three times a day. Can’t look at Spam in a grocery store to this day.

I remember how the Koreans would parade thru villages after an encounter with the Viet Cong and display body parts they had severed to show villagers what they would do to VC or their sympathizers. The Vietnamese believed it was unlucky to have parts removed in death.

I remember taking vehicles to assist locals with rice harvest. They would bag and we would haul.

I remember getting our daily ration of two hot cans of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer. Sure was good once ya got used to it.

I remember eating tons of C-rations from 1947/48. Ate many C-rations in the early days, especially when we were on the move. I know many vets are probably dying off because of those nasty things. Then at the mess tent it was water buffalo and rice, or rice and water buffalo. The powdered eggs were a real challenge too. When I soak my food today in Tabasco sauce, my friends ask how and why I do that to my food. I just say, “Hey, I was in the field in Nam.”

My favorite water came from a well in a village where coconuts were basking in the water. They had fallen off of a tree above the well and the villagers left them floating. The water was sweet and refreshing. The other places we used to get water from, heaven help us. There were the rivers, and we purified the water with chlorine or nasty iodine tablets. Many times we drank from running springs and sadly we didn’t purify it. What were we thinking? I’m still waiting for more effects from Agent Orange.

The All Important Combat Patch

The first place you looked on a guy’s uniform, after figuring out his rank, was the right sleeve. That’s where he wore his unit combat patch, which was a source of pride for most soldiers.

Many of the battery personnel looked at B Battery as a bastard unit. That is, we shot artillery for what seemed like everyone. We supported the Tiger division and the White Horse division of the Republic of Korea. For awhile we supported the 5th Special Forces, but to many disappointed soldiers, Special Forces would not allow us to wear their combat patch, the bastards. Hell, all I wanted was a beret. Then we were assigned to the 101st Airborne, and we all wore their patch.

101st Airborne Patch

When the 101st left in January of 1970 their patch went with them. Today B battery veterans of those years display the 101st eagle on caps, vests, jackets, and anywhere someone is likely to look.

Too Many Graveyards

In the days that I was with the B battery Bulls we were constantly on the move. We set the battery up in wet rice paddies, dry rice paddies, hill tops, mountain tops, beaches, deserted villages, inhabited villages, and many, many, many cemeteries. I hated the cemeteries as I always seemed to get stuck placing my sleeping accommodations on top of a “ripe” plot. We always dug in a foot or two. I still have night mares about it and I can still close my eyes and smell the stench associated with it.

I remember moving the guns to a graveyard outside Tuy Hoa. No markers, just mounds, and the graveyard was surrounded by rice paddies. We set up the guns and established communications. I remember running miles of wire along the road to Tuy Hoa and hooking up a switchboard. I think our call sign was “Scrappy White”. We then proceeded to dig in and fill sandbags with the dirt. The dead weren’t buried too deep, and they weren’t in coffins. I remember uncovering a half decomposed skull. I never will forget the smell. I think it was three days before I could fall asleep.

At the same graveyard, we received sniper fire for about a week. No one got hit, but we had to be careful during the day. We joked about hearing the bullets go by, cause if you could hear it, you knew you were safe. It was the one you couldn’t hear that would send you home.

Talk about a lasting impression, I avoid cemeteries to this day.

The Montagnards

On one of our missions with the 5th Special Forces we flew to the top of a mountain where there was a Montagnard village (mountain tribes friendly to U.S. forces). We flew in with all our equipment on C-123 cargo planes. I was on the first plane in, which headed for a spot where there was no airstrip. I remember taking a quick plunge out of the sky; the wheels touched down and immediately the pilot braked so hard I thought his feet had to be digging into the ground to stop the plane. We unloaded and waited for the next plane to come in. Holy cow, when the plane touched down it immediately started braking and pitched forward so far the nose section was actually scraping the ground – it was one with the grass. I did not realize a plane could stop in that short of a distance. Talk about scary, yes it was!

Army Special Forces were training the Montagnards to fight for us. I was amazed at the age of these soldiers being trained. Many were as young as 13 or 14, kids with guns. How ironic.

The Montagnards were friendly and welcoming to us. One afternoon they held a celebration and provided the meat for the evening meal. A large group of us gathered around as they ceremoniously took a knife to the cow’s throat and bled him out into a bucket. While the blood was still warm they drank the blood and offered it to us. I can’t remember any of us trying it, because I eased my way back behind the crowd of my fellow soldiers. Being from the Midwest I preferred my animals well-done.

December 11, 2013

John Santini – An Original – Part Two

The Boys of Battery B

John Santini

An Original Member of B Battery

Part Two

John traveled up and down the coast with B battery from Tuy Hoa south to Phan Rang, a span of 180 miles. His stories tell how the boys of B battery did more than fire howitzers. They manned patrols, they sat in pot bunkers at night under enemy fire, and sometimes they endured the wrath of the high seas.

Back on the Ocean

I remember going on LSTs twice from the Nha Trang beach.

Landing Ship – Tank

Under Threatening Skies

The first time we were on a special mission and had the whole battery loaded on board, howitzers, trucks, troops, everything. We got out on the ocean and a typhoon came in. We were bouncing around so much we lost a couple of trucks over the side. We almost lost a howitzer. The gun was hooked up to a truck and both were going over, so we released the truck to save the gun. One of the trucks that went over had all our personal gear. Then the mission was called off because of the bad weather. After that we only had what was on our backs.

From Nha Trang we worked our way up to Tuy Hoa. Every 50 miles or so we’d set up for a fire mission. In that area we supported the 101st Airborne, the 5th Special Forces and the Korean infantry, whoever needed artillery. After we lost all our gear off the LST we only had what was on our backs. Out in the jungle we washed our underwear and socks as best we could. For 30 days we were out there and we stunk. The enemy only had to wait for the smell and they knew we were there.

The Hesitation

This was later in my tour when we were further south around Phan Rang with the 101st. One of our observation posts was under attack. I made an ammunition run out to it and on this occasion I stayed with the OP. Most of the night we were under attack. Daylight was coming in when I saw the brush move, the jungle coming alive, somebody coming. At that point you’re ready to shoot anything that’s coming at you. You don’t even hesitate. I was locked and loaded ready to take out whatever it was. For some reason my brain made me hesitate, and I saw a brown face, not a while male or a Vietnamese. He kept on coming and when he got close I said that old bullshit, “Halt, who goes?” And he didn’t know nothin’ and just kept coming. He was drunk. So I got up from the foxhole and went out to him and discovered he was an American. He didn’t know the password because he was out all night. We talked for a moment and I let him by and did not see him again.

I mean I had a loaded weapon ready to go. If I thought he was VC he’d been gone. Could of been a child, any Vietnamese would have been gone. I was scared to death. I was going to shoot anything that moved, but something made me hesitate. I saw he was an American in military fatigues.

When I saw the jungle move I could have took him out right there. I was a distance shooter. They needed something shot at a distance, they’d call me. I could put a bullet where they wanted it. I had qualified for long distance shooting. If we had a target out there, they’d say see what you can do, hit that target. They’d look out with binoculars and tell me to raise or lower it, and I’d put the shot where they wanted it. We’d shoot at an area because maybe they saw something and didn’t want to open up with the howitzers.

Some years later I was working for Shaker Rapid Transport in Cleveland. I was sitting in the bull pen where we hung around and waited for assignments. You sit around, drunk coffee, talk and wait till the dispatcher needs someone to move a train. Here comes a new guy and at first we didn’t talk, we just stared at each other. Then when we were driving a train together, at the end of the line we had a conversation and he said. “I know you from somewhere.”

I said, “I know you too, you look familiar.”

He said, “You were in Nam with B battery, 5th of the 27th.”

I said, “Yeah” and pretty soon we figured out that he was the guy I almost shot coming out of the jungle. He remembers when I was going to shoot him. We laughed and said “crazy son-of-a-bitch” a lot.

Leaving Vietnam

John’s departure from Vietnam was almost as complicated as his getting there.

We were at Tuy Hoa. It was late at night, between midnight and three in the morning, and our OP was overrun by the enemy and abandoned. We had to get the OP back, and I was part of the support team to go get it. In the process one of the soldiers got bitten by a snake, I can’t remember where. He was screaming his head off out there. We’re trying to cover his mouth and shut him up. He kept screamin’, “I’m gonna die … I’m gonna die.” There was no medic, so I took a flashlight and saw that where he was bit was red and swollen. I cut it open and let it bleed, and he’s screamin’ and screamin’. Then I did the John Wayne thing and sucked on the spot and spit it out of my mouth. And that’s all I did.

After we secured the OP and got back to base, the medic said the guy’s got to go to the hospital. We called a Medivac helicopter that night. I was already scheduled to go to the hospital the next day for dental work, so they told me not to go back to the OP but to go with him.

I’m at the 8th Army Field Hospital in Nha Trang. I was a bleeder and I had a high fever. They told me all my teeth had to come out. I was already scheduled to have my teeth taken out. I don’t know if the snake was poisonous or if it had anything to do with my teeth. All I know is I stayed in the hospital for a long time. After my teeth came out and I stopped bleeding, they would come in and take my temperature and say I had to stay. Two weeks later you’re still in the Army hospital, every day you still got a thermometer in your mouth, and they’re still saying you ain’t going back to your outfit.

While I’m in this Army hospital I wrote a letter to my mother telling her where I was at. Meanwhile my mother got a telegram from the Army saying PFC Herman John Santini is missing in action, or he’s AWOL (away without leave). My mom knew I was in the 8th Army Field Hospital. So she called the number in the telegram and tells them. Then she gets another telegram to CONFIRM her son is missing in action or AWOL. Now my mother goes to a congresswoman named Frances Boatman and tells her the story, and that brought some pressure.

In the hospital they made an arrangement for me to talk to my mother. I was ordered to go to go to a certain area so I could call home. I talked to my mother and said I was all right and “Don’t be writing no more letters.”

I rotated out of the country from the hospital. It was my last duty assignment. I was only in Vietnam three months, but my two year commitment was almost up.

Still they couldn’t send me home because I did not have a shot record; it went overboard in the typhoon with everything else. So they gave me a jeep driver and we went back to the 101st Airborne in Phan Rang. I couldn’t get the shots again because you couldn’t get them all at the same time. The lieutenant told me to find someone who was close to my dates of rotating in and rotating out, and we’d copy his record. So that’s how my shot record became my shot record. Then we drove back to the hospital.

One of the hardest things coming home from Vietnam …I never told my family, my wife, my daughter, or anybody that knows me personally how long I was in Vietnam. Whenever I got the question I said I couldn’t hear you, and worked around the issue, and never answered the question. I have lied. One time I did say I was there for a year. But I was not there for a year. I was very embarrassed to say I was not in Vietnam for a year. I suffered for years over that. It got to me. I busted my ass to go with my unit to Vietnam. Almost got court martialed for everything I did, and those are my boys. I was one of the earliest to come home. It was heartbreaking to leave. You socialized with these guys, you slept with them, you went downtown together, you did everything with them. You didn’t get along with everybody every day of the week. They used to beat me up, tie me up at night, they used to put shaving cream in my pants. In the end we were all one family. We’d do anything for each other.

Dad

My father survived his heart attack. When I came home he was the proudest man in the world. I’m thinking of it right now, coming into the kitchen and seeing him sitting there, an old Italian with his coffee cup. He greeted me at the door and hugged me.

December 4, 2013

John Santini – An Original – Part One

The Boys of Battery B

John Santini

An Original Member of B Battery

Part One

PFC John Santini

Ft. Lewis, Washington

Nobody worked harder than John Santini to get to Vietnam with B battery. He was assigned to the battery when it was formed at Ft. Lewis, Washington on November 23, 1964 under the 5th Battalion. However his path to Vietnam was complicated.

John trained with B battery for almost a year and grew close to the other guys in the unit. “The original B battery was like a melting pot of all different people,” John says. “We had our stragglers, but B battery was a strac unit (strategic, tough and ready around the clock). We could do any mission the Army wanted of us.”

When orders came down for Vietnam, John was on a temporary assignment to the National Trophy and Pistol Matches being held at Ft. Perry, Ohio. He was told he could not deploy with his unit because it was already at full strength, and furthermore he was not to return to Ft. Lewis. But John was determined to join his buddies and showed up at Ft. Lewis anyway. There he was assigned to a new unit with the 30th Artillery. Again disobeying orders he refused to report for duty, saying he would only serve with B battery. The authorities warned he would be arrested, but in time relented and assigned him back to his beloved B battery.

Records at the National Archives indicate that when the battalion deployed to Vietnam on October 23, 1965 it was four enlisted men short of full strength. Perhaps the Army found a spot for this young hothead rather than throw him in the brig.

Today John talks of B battery with a passion the years have not cooled.

From the Heart

Legally I volunteered for Vietnam because I was not ordered to go. That’s how I got back into the unit, by volunteering. I said to the commanding officer, “Sir, wherever my troops are going, my boys are going, I’m going. We stick together, we sleep together, we shower together, we do everything together. They’re going over there, then I’m going over there.”

At that time I had orders for a hardship discharge because my dad was dying in the hospital. He had suffered a major heart attack and they believed he wouldn’t survive. The hardship would be on the family, and I would have to go back home and go back to work. I went to see him and said, “Dad, these are my boys. If they go to Nam, I’m going to Nam.” I told my father, “Dad, I love you, but I gotta do what I gotta do.” The words came out of my heart. He cried like I’m crying right now. He never did understand, he worried so much. I would never abandon my troops … never.

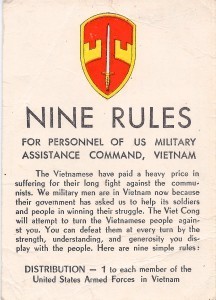

The Nine Rules for Vietnam

From Ft. Lewis we got on busses for Sea-Tac airport in Seattle. Walking through the terminal we were in full combat gear, with our helmets and M14 rifles. People stopped and looked at us, some of them applauded. We boarded a plane and went to Oakland, California. As we were getting off the plane, every man on the airplane was given a kiss, whether he was black, white, Hispanic, or whatever he was. Every one of those stewardesses lined up at the door and gave each one a kiss, and they were crying their eyes out. It was heartbreaking.

From there we went directly to the ship, the J.C. Breckenridge. Everything was on the ship, our gear, the guns, trucks, everything. I think we stayed in port for a couple days. Then we were off. We went underneath the Golden Gate Bridge, looked up and it was the most beautiful bridge in the world. We went out on the ocean, and the official record says it took 19 days. The ship broke down outside Hawaii, and it took two days for the swabbies to get it fixed. We never went into port there, you could see the island in the distance. Then we went on to Okinawa, where we stayed just one day. We were able to get off the ship and tour the city. From there we went to Vietnam.

On board the ship we had to exercise on the deck of the ship until it got too hot. We did target practice with our M14s out into the ocean, to stay familiar with our weapons. And on the ship you had to work, you were given details. But I brown-nosed my way out of them. I would walk around and watch the Navy guys chipping away at the grey paint – chip it, paint it, chip it, paint it. That’s all they did: chip it and paint it.

I remember the good Navy food.

We used to go up on deck at nighttime and watch the waves. It was the scariest thing you’d ever want to see. Here you are a little ship in a gigantic ocean. You wouldn’t see a ship, nothing for days. There was nothing out there. If that ship would have sank, you’d have died.

We had classes from Captain Johnson. He had been to Vietnam before and that’s why he was our captain. He was telling us how to stay alive over there, he was telling us about what to expect. We had classes about respecting the Vietnamese. Don’t go out there and fuck everything that walks, their mothers and daughters, don’t do stuff like that. They’re human beings, not sluts and trash. They want you to respect the culture. They want you to go in there and do your job and obey your commands and treat people right. They gave everybody a little card that I kept.

The Early Days

We arrived at Cam Ranh Bay and stayed outside port for two days. We were on the deck in our combat gear with live ammunition, still maybe 200 yards from the port. Some of us had the clips locked into our rifles, and they told us to remove them. They said, “As soon as you get on the ground, put the clip in your gun.” We left the boat on ramps, loaded the ammunition and equipment on five-ton trucks, and then hooked the guns behind the trucks. On our first day we joined the 101st Airborne Infantry at a rubber plantation off Highway 1 on our way up to Nha Trang. There we set the battery up and stayed for a little while.

Here’s how we used to do it. We’d go into a position and first thing the guns would go up, get ready for a mission. Then we’d set up a perimeter with concertina wire, set the Claymore mines, and then go clean the brush, get the area opened up. Then you’d dig your fox holes and then you’d dig the equipment in. You’d dig the trucks in, their noses stuck down in the ditch. That’s a hard job.

The 101st would send out a patrol and if we had the manpower we’d send a couple guys with them. The patrol was to find out how far away the enemy was from you. You’d go out and see if you could draw fire. You’d drop down and return fire and hope someone was behind covering you. We’d send guys out with the patrol to teach them how to run the patrol. But they weren’t going to send a gunner out, in case we got a fire mission. They’d send FDC, a cook, an ammo guy like me, or anybody. Remember we didn’t know anything about Vietnam. We were all green horns.

Stateside I was an artillery man, but to join the unit I became ammo. In Vietnam I did something different every day. Some days I went on the guns, especially if someone was sleeping, so I wasn’t just ammo. I volunteered for every patrol that came down. I was a weapon in the states and a go-getter in Vietnam. People would say to me, “You’re trying to get yourself killed out there.”

I’d say, “I’m not trying to get myself killed. Somebody’s got to go, so let me go.”

I have a picture of my ammo bunker. The live ammo rounds, with their detonation fuses attached, are all stacked up under a tent.

If Colonel Munnelly would have seen this he would have died, because there are no sandbags around that ammo.

When Lieutenant Colonel Munnelly took command some months later he made sandbagging a top priority for all units of the battalion. Korea had taught him it wasn’t optional.

Manning the Observation Post

The OP was a hole in the ground for three men with maybe a couple sandbags in front.

Observation Post Under Construction

We stuck them out far enough to protect the perimeter, and close enough to get back to the compound. We manned the OPs all night, usually with two guys and an M60 machine gun. At night is when we usually got hit, and 90 percent of the time we got hit. You didn’t sit around your foxhole and talk and drink coffee and smoke cigarettes. That didn’t happen. They’d fire at you and keep you awake all night. Or we had fire missions all night long.

We never had enough ammunition at the OPs. I’d have to race out there with ammo and sometimes stay to support them. You’d put on two bandoliers of M14 ammo, grab two boxes of M60 machine gun ammo, and you’d go out. And don’t forget you got to carry your own personal weapon. Sometimes we’d have to abandon the OP because we didn’t have enough firepower to force back the enemy. When you run out of bullets you’re retreating. Later you’d have to go back out and get your guns back. Can’t leave that M60 machine gun out there.

When that sun came up you survived another night. The next day all you’re guaranteed is four hours of sleep … if you could get it.

Trying To Get His Four Hours

First Fire Mission

We’re in Vietnam about a month and it’s Thanksgiving day. We had just joined up with the Korean marines outside Nha Trang airport. We had our perimeter set up, we’re in combat mode, and we’re waiting around for orders.

Now everyone is bitching, because here it is Thanksgiving and we’re eating C-rations out of cans. Soon choppers landed and brought us a real Thanksgiving meal. We hardly started when a fire mission came in. A Special Forces unit was in trouble on a nearby mountain, they were pinned down. We started the mission before the sun went down with only a few rounds, but it went on for most of the night. That was our first combat mission, to support the 5th Special Forces on Thanksgiving of 1965.