John Santini – An Original – Part One

The Boys of Battery B

John Santini

An Original Member of B Battery

Part One

PFC John Santini

Ft. Lewis, Washington

Nobody worked harder than John Santini to get to Vietnam with B battery. He was assigned to the battery when it was formed at Ft. Lewis, Washington on November 23, 1964 under the 5th Battalion. However his path to Vietnam was complicated.

John trained with B battery for almost a year and grew close to the other guys in the unit. “The original B battery was like a melting pot of all different people,” John says. “We had our stragglers, but B battery was a strac unit (strategic, tough and ready around the clock). We could do any mission the Army wanted of us.”

When orders came down for Vietnam, John was on a temporary assignment to the National Trophy and Pistol Matches being held at Ft. Perry, Ohio. He was told he could not deploy with his unit because it was already at full strength, and furthermore he was not to return to Ft. Lewis. But John was determined to join his buddies and showed up at Ft. Lewis anyway. There he was assigned to a new unit with the 30th Artillery. Again disobeying orders he refused to report for duty, saying he would only serve with B battery. The authorities warned he would be arrested, but in time relented and assigned him back to his beloved B battery.

Records at the National Archives indicate that when the battalion deployed to Vietnam on October 23, 1965 it was four enlisted men short of full strength. Perhaps the Army found a spot for this young hothead rather than throw him in the brig.

Today John talks of B battery with a passion the years have not cooled.

From the Heart

Legally I volunteered for Vietnam because I was not ordered to go. That’s how I got back into the unit, by volunteering. I said to the commanding officer, “Sir, wherever my troops are going, my boys are going, I’m going. We stick together, we sleep together, we shower together, we do everything together. They’re going over there, then I’m going over there.”

At that time I had orders for a hardship discharge because my dad was dying in the hospital. He had suffered a major heart attack and they believed he wouldn’t survive. The hardship would be on the family, and I would have to go back home and go back to work. I went to see him and said, “Dad, these are my boys. If they go to Nam, I’m going to Nam.” I told my father, “Dad, I love you, but I gotta do what I gotta do.” The words came out of my heart. He cried like I’m crying right now. He never did understand, he worried so much. I would never abandon my troops … never.

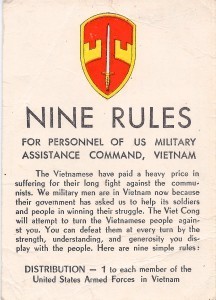

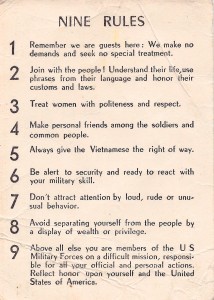

The Nine Rules for Vietnam

From Ft. Lewis we got on busses for Sea-Tac airport in Seattle. Walking through the terminal we were in full combat gear, with our helmets and M14 rifles. People stopped and looked at us, some of them applauded. We boarded a plane and went to Oakland, California. As we were getting off the plane, every man on the airplane was given a kiss, whether he was black, white, Hispanic, or whatever he was. Every one of those stewardesses lined up at the door and gave each one a kiss, and they were crying their eyes out. It was heartbreaking.

From there we went directly to the ship, the J.C. Breckenridge. Everything was on the ship, our gear, the guns, trucks, everything. I think we stayed in port for a couple days. Then we were off. We went underneath the Golden Gate Bridge, looked up and it was the most beautiful bridge in the world. We went out on the ocean, and the official record says it took 19 days. The ship broke down outside Hawaii, and it took two days for the swabbies to get it fixed. We never went into port there, you could see the island in the distance. Then we went on to Okinawa, where we stayed just one day. We were able to get off the ship and tour the city. From there we went to Vietnam.

On board the ship we had to exercise on the deck of the ship until it got too hot. We did target practice with our M14s out into the ocean, to stay familiar with our weapons. And on the ship you had to work, you were given details. But I brown-nosed my way out of them. I would walk around and watch the Navy guys chipping away at the grey paint – chip it, paint it, chip it, paint it. That’s all they did: chip it and paint it.

I remember the good Navy food.

We used to go up on deck at nighttime and watch the waves. It was the scariest thing you’d ever want to see. Here you are a little ship in a gigantic ocean. You wouldn’t see a ship, nothing for days. There was nothing out there. If that ship would have sank, you’d have died.

We had classes from Captain Johnson. He had been to Vietnam before and that’s why he was our captain. He was telling us how to stay alive over there, he was telling us about what to expect. We had classes about respecting the Vietnamese. Don’t go out there and fuck everything that walks, their mothers and daughters, don’t do stuff like that. They’re human beings, not sluts and trash. They want you to respect the culture. They want you to go in there and do your job and obey your commands and treat people right. They gave everybody a little card that I kept.

The Early Days

We arrived at Cam Ranh Bay and stayed outside port for two days. We were on the deck in our combat gear with live ammunition, still maybe 200 yards from the port. Some of us had the clips locked into our rifles, and they told us to remove them. They said, “As soon as you get on the ground, put the clip in your gun.” We left the boat on ramps, loaded the ammunition and equipment on five-ton trucks, and then hooked the guns behind the trucks. On our first day we joined the 101st Airborne Infantry at a rubber plantation off Highway 1 on our way up to Nha Trang. There we set the battery up and stayed for a little while.

Here’s how we used to do it. We’d go into a position and first thing the guns would go up, get ready for a mission. Then we’d set up a perimeter with concertina wire, set the Claymore mines, and then go clean the brush, get the area opened up. Then you’d dig your fox holes and then you’d dig the equipment in. You’d dig the trucks in, their noses stuck down in the ditch. That’s a hard job.

The 101st would send out a patrol and if we had the manpower we’d send a couple guys with them. The patrol was to find out how far away the enemy was from you. You’d go out and see if you could draw fire. You’d drop down and return fire and hope someone was behind covering you. We’d send guys out with the patrol to teach them how to run the patrol. But they weren’t going to send a gunner out, in case we got a fire mission. They’d send FDC, a cook, an ammo guy like me, or anybody. Remember we didn’t know anything about Vietnam. We were all green horns.

Stateside I was an artillery man, but to join the unit I became ammo. In Vietnam I did something different every day. Some days I went on the guns, especially if someone was sleeping, so I wasn’t just ammo. I volunteered for every patrol that came down. I was a weapon in the states and a go-getter in Vietnam. People would say to me, “You’re trying to get yourself killed out there.”

I’d say, “I’m not trying to get myself killed. Somebody’s got to go, so let me go.”

I have a picture of my ammo bunker. The live ammo rounds, with their detonation fuses attached, are all stacked up under a tent.

If Colonel Munnelly would have seen this he would have died, because there are no sandbags around that ammo.

When Lieutenant Colonel Munnelly took command some months later he made sandbagging a top priority for all units of the battalion. Korea had taught him it wasn’t optional.

Manning the Observation Post

The OP was a hole in the ground for three men with maybe a couple sandbags in front.

Observation Post Under Construction

We stuck them out far enough to protect the perimeter, and close enough to get back to the compound. We manned the OPs all night, usually with two guys and an M60 machine gun. At night is when we usually got hit, and 90 percent of the time we got hit. You didn’t sit around your foxhole and talk and drink coffee and smoke cigarettes. That didn’t happen. They’d fire at you and keep you awake all night. Or we had fire missions all night long.

We never had enough ammunition at the OPs. I’d have to race out there with ammo and sometimes stay to support them. You’d put on two bandoliers of M14 ammo, grab two boxes of M60 machine gun ammo, and you’d go out. And don’t forget you got to carry your own personal weapon. Sometimes we’d have to abandon the OP because we didn’t have enough firepower to force back the enemy. When you run out of bullets you’re retreating. Later you’d have to go back out and get your guns back. Can’t leave that M60 machine gun out there.

When that sun came up you survived another night. The next day all you’re guaranteed is four hours of sleep … if you could get it.

Trying To Get His Four Hours

First Fire Mission

We’re in Vietnam about a month and it’s Thanksgiving day. We had just joined up with the Korean marines outside Nha Trang airport. We had our perimeter set up, we’re in combat mode, and we’re waiting around for orders.

Now everyone is bitching, because here it is Thanksgiving and we’re eating C-rations out of cans. Soon choppers landed and brought us a real Thanksgiving meal. We hardly started when a fire mission came in. A Special Forces unit was in trouble on a nearby mountain, they were pinned down. We started the mission before the sun went down with only a few rounds, but it went on for most of the night. That was our first combat mission, to support the 5th Special Forces on Thanksgiving of 1965.