Ed Gaydos's Blog, page 16

April 9, 2014

Rik Groves – Gun Chief – Part Five

THE BOYS OF BATTERY B

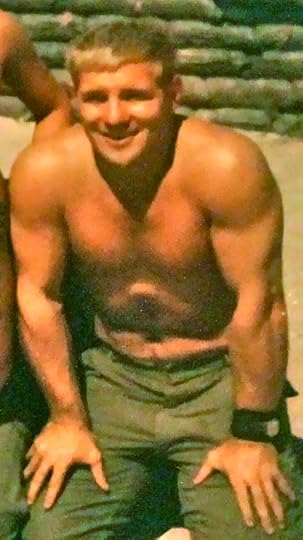

STAFF SGT. RIK GROVES

GUN CREW CHIEF

PART FIVE

To the Vietnam vet there is no such thing as a little thing. The powder blue wraparound from Aunt Beverly hanging blood soaked in the shower is not a little thing in Rik ’s memory. That image carries the entire weight of the early morning hours of August 12, 1969 when wounded himself he held the dying Stanley in his arms.

Neither is a mustache a little thing.

Mustache Madness

When I got wounded I had 32 days left in Vietnam. Now I’m really a short timer, full of sass such as, “I’m so short I can’t see over the curb.” The doctor comes to me after about ten days or so in the hospital at Cam Ranh and says, “Sergeant Groves, I see you’re to ETS (get out of the Army) when you leave Vietnam.”

“Yes sir.”

“You know, normally when we have guys that are that close to getting out of the service we automatically Medevac them to Camp Zama in Japan.”

I say, “Sounds great.”

“You need to understand if you go there and you are about to leave the service, they will make sure everything is looked at. They’ll do your dental and all that stuff. So you could end up spending a little more time in the Army.”

By now I’m down to maybe 20 days. I say, “Then I don’t want to go to Camp Zama.”

“OK. When you’re done here you’re probably going over to 6th CC. That’s a convalescent center here in Cam Ranh. Then you’ll go back to your unit, but I don’t want you going out in the field anymore. You’re not healed enough.”

So that was on my orders, not to go back out to the field. But I want to pop out to Sherry for a few hours to say good bye to everybody, and that’s when I have the run-in about the mustache.

For ten months I had a mustache. It’s what guys did who went to Vietnam, they grew mustaches. It had been that way since WWII. You grow mustaches. So we grew them, and I had mine for nine or ten months. But they couldn’t control the people back in Phan Rang, the mustaches got too raggedy. So they made the rule that if you don’t have a mustache on your ID card you can’t have a mustache, knowing full well that the vast majority of guys in the battalion are going to have ID cards from their doggone basic training picture, when they had no hair on their head let alone facial hair. So that eliminated 99% of everybody, if not everybody. So we all had to shave them off.

I am in the hospital 16 days, and during that time I grow my mustache back, with the idea that I’d get a new ID back in Phan Rang. And I did get a new ID. I’ll be damned if I was going home from Vietnam after all that time and not have a mustache.

Now I’m down to 12 days left in Vietnam and trying to catch a ride out to Sherry to say good bye. I cannot get a chopper until 4:00 in the afternoon, which I am not happy about because I know in my heart I’m gonna get stuck there overnight. And you don’t think I’m a little jumpy? Holy shit, I don’t know how people function very well after getting wounded and having to go back into the field. Tommy Mulvihill was hit five times and he kept going back. I don’t know how he did it.

I get off the chopper at Sherry and Captain Marquette is there. That day I write in my journal:

Captain Marquette was really nice. First thing he said on seeing my mustache was, “You grew it back didn’t you, you rascal?” I replied, “Yes sir, and I’ve got a new ID card too.” We both had a good laugh. September 2, 1969

I do have to spend the night at Sherry, I don’t even remember where I slept that night. Of course nothing happens. It is at the 1:00 formation the next day that the trouble begins. The first sergeant and the XO tell everyone to take out their ID cards, they are checking for mustaches. If you had a mustache and it was not on your ID, they were going to make you dry-shave it off in front of the formation. First of all it hurt like hell, and it was humiliating.

I am at the front of the formation, without a section of course, so they come to me first. They say they cannot see the mustache on my ID. It is real light, because the quality of the picture is crap, but it is there. Still they claim they can’t see it and I have to shave it off, and I refuse. After the formation they haul me off to their hooch and say some things to me that really hurt. I was a sensitive kid . . . too sensitive.

Finally they say let’s go see the battery commander. I say that would be great. I go up to the BC’s hooch, first on my own. I sit down facing him and tell him what had happened. He had not seen the ID before, because on the chopper pad the day before I had just told him about it. He looks at the ID – I remember this so well – he looks up at me, looks down at the ID, up at me again and says, “You know it is kind of hard to see, Sergeant.”

I say, “Yes sir, but it’s there.”

He says, “Yeah, it’s there.”

And just then the XO sticks his head in, starts to rail on me, and Marquette tells him to beat it. That’s when I break down in tears. “I can’t believe they’re doing this over such a stupid thing. I just came back to say good bye to friends I’m never gonna see again, I been through so much, just got wounded, Stanley died in my arms, and they’re doing this crap over friggin’ mustaches?” I was broken hearted is what I was. I remember it so well like it was yesterday. I couldn’t believe it was happening.

I felt that pain and anger for 38 years. But today that XO, Hank Parker, is a great and forever friend. We were all so young then, including the officers. Hank and I laugh about it now. I have the last word, and he may agree, that they were misguided in their approach to mustaches

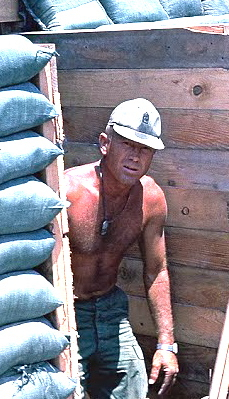

Rik WITH His Mustache

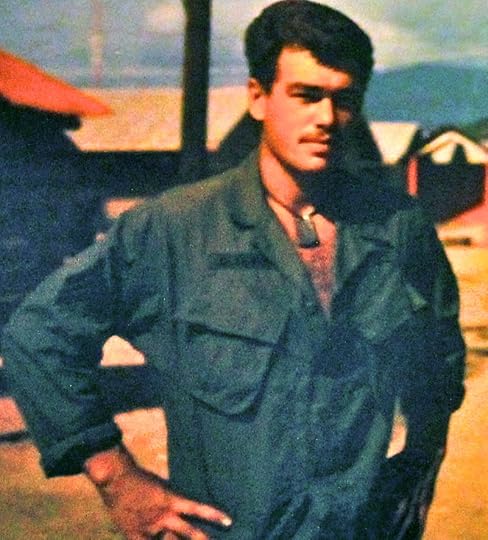

Paul Dunne

My two best friends over there were Dick Graham and Paul Dunne. Paul being a Boston guy he called everybody pal, always saying, “Hey pal.” When the last guard would wake us at 6:00 in the morning I’d get up and go around to all the hooches and make sure everybody was awake. That was my routine. The hooch Paul was in had beads across the door, and I’d pull the beads apart and in a heavy Boston accent say, “Gud mawnin’ pal.”

He’d sit up in his cot and say back, “Aawh, gud mawnin’ pal.” It was an unwritten traditional thing we did.

We became very good friends, him an Irish Catholic from South Boston. His family had a house out on Cape Cod. He’d say, “When we get home we’ll have you out to the Cape. We got serfin’, you think California’s the only place that serfs? We serf all the time off the Cape.”

I was home two months when I got a letter right around Thanksgiving from Dick Graham that Paul had been killed. It was just devastating for me. I never heard the story of what happened until I met Jim Kustes in Washington in 2007. Paul was killed when his jeep hit a road mine. Jim Kustes was sitting on the fender of the jeep, literally right over the blast. He is so lucky to be alive, but it messed him up. The pictures of his jeep I only saw within the last two or three years.

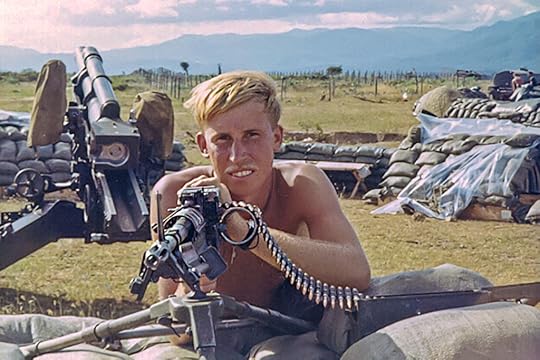

Paul Dunne On Laundry Day

After Paul died I wrote his family, sometime in the early 70s. His mother Edna worked for Massachusetts Bell, and his dad Paul Sr. was a painter. I wrote them expressing my sympathy and grief. I said, “I don’t know how you feel about the Vietnam War, but I just want you to know your son died serving his country. I miss him greatly.”

One day Edna called, and then we corresponded. Every Christmas she would send my baby daughter a present. And then one day in the Spring of 1974 she called – she had kind of a high pitched Boston accent – “I’d like to invite you and your wife and Heather (my daughter) out heah to the Cape house. I nevah got to see ya with Paul.” I went out and visited them, saw Paul’s grave, and stayed a few days. Since then Paul Sr. has died, but I continued to call Edna. Now no one answers her number. The number is still good but nobody ever answers.

It’s the same thing with Stanley’s family. I found his older sister maybe ten years ago. I felt guilty about never contacting his family. I found her through a columnist at the Akron newspaper. Her name is Eula, but she went by ‘Fay’. She called me and I had some long conversations with her. This columnist wrote a story about it in the Akron paper. I sent her cards every Christmas and letters during the year, and she’d send letters back. And then one day my letter got returned. I don’t know what happened to her. And it’s the same thing, I’d call there and the phone’s not disconnected, but there’s no answering machine and no one answers. There’s a void there I feel really bad about.

Every Sunday in church, and I’ve been doing it for many years, toward the end of the service we have outreach prayers: for peace in the world, wisdom for our leaders, people who are ill, and whatever. While this is going on I’m half listening, but in my mind I list all seven guys – Sherlock, Gulley, Handschumaker, Johnson, Stanley, Pyle, and Paul Dunne – and ask the Lord to be with that family today and let them feel your peace today. In the past few weeks I’ve added the other three men from B Battery that were killed . . . Bobby Joe Marsh, Jeff Davis and George Beedy. I honor their memory this way. It’s a way for me to remember and pay my respects.

April 2, 2014

Rik Groves – Gun Chief – Part Four

THE BOYS OF BATTERY B

STAFF SGT. RIK GROVES

GUN CREW CHIEF

PART FOUR

A relentless rain of mortars and rockets fall on LZ Sherry the summer of 1969. W hile Medevac helicopters travel in and out of LZ Sherry like commuter trains, S taff Sergeant Groves is counting off his remaining days in Vietnam.

Cry of the Short Timer

I considered myself short at 60 days left in country. In the morning I’d come out of my hooch and yell at the top of my lungs across the battery, “SHOOOOOOOOORRT.”

And then I’d hear, “FUUUUUUUUUCK YOOOOU.”

It became a daily ritual and I loved doing it.

So far Rik has escaped injury, suffering only a frightening but harmless slap on the jaw from the smooth side of a piece of shrapnel. Then comes the early pre-dawn of a fateful day in August.

August 12, 1969

Guys would normally go around in a towel after a shower. My aunt Beverly, my godmother, sent me a terrycloth shower wraparound for Christmas as a joke. It was powder blue with white trim around the waist, and it had little snaps to hold it on. There was a little pocket with white trim, and on that trim “Rik” was embroidered in blue. Whenever I’d go to the shower I’d wear it as kind of an on-going joke. It drew catcalls from the guys, “Oh Sergeant Groves, you look beautiful.”

My gun was the one assigned to shoot illumination rounds. We kept a separate mini ammo bunker of illumination rounds already pre-cut and ready to go, so we could get a lot of them up in the air right away if we got mortared. We’d often get six or eight rounds up in the air at the same time. The way I ran my gun section, I would be on the gun with my assistant gunner Gonzales, and I would load and he would pull the lanyard and traverse the tube so the next round would go to a different place. There would just be two of us on the gun, and I kept everybody else in the ammo bunker cutting more rounds and leaning them against the parapet, and hopefully more out of the way if mortar rounds hit close. That way a mortar round would not take out the whole gun crew. It would just take me and Gonzales out. That was my rationale.

We were on 50% guard rotation, meaning we started the first guard about 9:00 at night and it went to 1:30 in the morning, and second guard went to 6:00 AM. I just came off first guard and was sleeping in my hooch right beside the gun. In Vietnam you know when you’re sleeping you’re still listening, and you can tell what your own H&I and illumination sounds like. It went on all night. If our gun shot a round and I’m laying in bed I would not wake up. But if somebody shouted INCOMING, or if a mortar round came in and hit, it would wake me up. That’s when I first learned that your brain can sort things out even when you’re sleeping.

That particular morning I was asleep after my guard duty and I heard someone shout INCOMING. It woke me up but there was nothing landing yet. I laid there and I heard INCOMING again. There were some flares up, but no explosions. That was because the guys on the guns could hear a mortar leaving the tube, and by the time it landed we always had one or two illumination rounds in the air. So I jumped up and I grabbed my steel pot and flak jacket – and for some reason that morning I put Aunt Beverly’s wraparound on and ran out. Why in the world I took time to put that thing on I will never know.

As I come out of my hooch a mortar round hits close by and showers my hooch with shrapnel and sand and rocks. I jump about a foot and dive over the parapet wall. I grab a round out of the ammo bunker and bring it out to the parapet wall and lean it up against the wall. As I do that Theodus Stanley is on my left. We called him Stan, or Yodo sometimes, because his brother couldn’t pronounce Theodus and called him Yodo. I liked Stanley a lot. He is doing the same thing, leaning a round against the wall to have it ready

I am turning to my left and Stanley is turning toward his right, we’re turning toward each other, when a mortar explodes right in front of my hooch close to us. If I had been coming out of my hooch I would have been five feet from it. I feel this tremendous blow on the right side of my neck, like someone had hit me as hard as they could with their fist, or I had been hit in the neck with a bat. The blast blows us both down to the ground. The next thing I know I’m facing the other direction and I’m on my hands and knees, and my helmet is bouncing away in slow motion. Everything is in slow motion. As it’s bouncing away the edges of the helmet are kicking up little sprits of sand and dirt. In my mind’s eye my right arm comes into view as I’m reaching for it, still in slow motion. Just as I almost reach it, I’m back into full speed again, and the helmet is out of reach.

I get up onto my knees. I hear the sound of like when you turn on your water faucet in the back yard but you don’t have a hose attached to it and the water is splashing on the grass, a slapping sound. I turn around still on my knees and see Stanley on the ground cross ways to me. The only thing off the ground is his chest, as if he had done a bunch of pushups and can’t keep his whole body off the ground anymore. The only thing elevated are his shoulders and upper chest. His head is up. The splashing sound is a torrent of blood coming out of a hole in his upper chest or his neck.

I turn him over. I cannot hear any sound like a sucking chest wound. I had enough training to know it could be the top edge of the lung. I’m back on my haunches with the weight on my heels and I pull him across my legs. I hold him to me and push on that wound as hard as I can to seal it.

He never says a word. There is not a sound out of him. Now there are more mortar rounds coming in. Then Doc is there, our medic, I think his name was Gilyard, a very religious guy. He had dashed through the landing rounds and now drops down next to me on the other side of Stanley and starts working on him, trying to patch him up as best he can. He starts giving him mouth to mouth, because Stanley isn’t doing anything. I’m still half cradling him and he’s just laying there with his arms to his side. And then his arms start to raise up from the elbow. As he’s doing that I’m yelling, “Come on Doc, hurry, hurry, he’s going, he’s going.” Stanley’s lower arms are rising up perpendicular to the ground, and then they stop, and there is an exhaling from him, and he is gone. But Doc keeps at him.

Gonzales who is on the gun sees it and he goes to pieces, falling to the ground yelling, “No, no, no.”

I say to Gonzales, “Get back on the gun,” and he does it immediately.

Somebody else starts loading and he goes back to pulling the lanyard. He’s screaming profanities, “Those son-of-a-bitches, fuckin’ bastards,” but stays on the gun.

Dick Graham, who a few weeks before had been moved off my gun to Motor Pool as a clerk, had been over talking to the guys when the rounds started coming in. Graham was on my gun crew when they discovered he had a college degree and could type. So they sent him off to school and brought him back as a clerk. That’s how I lost him. The Maintenance and Commo guys, unless they had duty on the towers, they could stay in their hooches. But Graham stays with the crew and helps hump ammo, the son of a gun, he stays there in harm’s way.

All of a sudden Graham’s standing in front of me and I turn to him, I’m still on my knees, and for the first time I start hurting. Doc is still bent over Stanley, his arms still perpendicular in the air and not a sound out of him. I turn to Gonzales and say, “I think I’m hit, can you check me over.”

We’ve got all these illumination flares in the air and it’s like daylight. He bends over me – I’ll never forget this – he looks down at me and with fear in his eyes and voice says, “Oh my god!”

I look down and I’m solid red, blood all over me, my arms, my hands, my legs, my chest, blood everywhere. For the first time I get a little scared. I’m not differentiating whether it’s my blood or Yodo’s. I say, “Can you see where I’m hit?”

This is another image I’ll never forget. He bends over and points and his whole hand is shaking. That image of his shaking, pointing hand has stuck with me all these years. He says, “I see one in your neck.”

I say, “Yeah, I can feel that one. It hurts like hell.”

Then he points to one in my chest up by my collarbone. “You got one there. And there might be one in your arm.”

Gonzales (left) and Dick Graham

By then Doc says, “Let’s look at you Sergeant Groves.”

The mortars have stopped now. Doc is walking me over to his hooch so he can check me out. He says, “Can you walk?”

I say, “Yeah.” It’s really starting to hurt now quite a bit, and I remember saying to the Doc as I’m walking, “Doc, you got any morphine?”

He says in a light tone of voice, I know now he was trying to be comforting, “Sergeant, we don’t do morphine much anymore.” Meaning that’s a WWII kind of thing, that’s not the first thing they give you anymore. He says, “We got some other stuff.”

We get to his hooch and he sits me down in a chair and he’s working on my neck. He’s off to my right out of my sight. At that moment Captain Marquette sticks his head in and says something like, “How you doing, Sergeant?” And then he looks at the medic and says, “Doc?”

Doc doesn’t say anything. Now I get scared a little more. Did Doc shake his head, like no he’s not going to make it? I don’t know.

Doc patches me up as best he can, but he can’t stop the bleeding out of my neck. They carry me on a litter to that open area in front of Maintenance. I’m waiting there for the Medevac when I find out that Paul Dunne also had been hit. He got a nasty gash on his bicep. Dunne, me and Stanley’s body all get Medevac’d together back to the aid station at LZ Betty.

We’re nervous about going in there because we wonder how competent they are. Guys had gone in, not our guys, and had died that were not hurt that bad. I’m laying there right next to Stanley’s body on another table five feet away. Doc back at Sherry had covered his face.

They work on me, and here’s the weird thing, they wrap an Ace bandage around my neck. I’m thinking, I understand an Ace bandage to apply pressure on an arm or a leg, but around my neck? It didn’t feel right to me. Then they tell me to go in and take a shower and wash the blood off. Here I’m wounded and still bleeding and they have me go into a shower and wash off. I remember hanging that blood soaked wraparound from Aunt Beverly on a hook in the shower. I’m thinking, Wait a minute, I’m a wounded guy standing in the shower washing the blood off myself, and it’s hurting like hell. Shouldn’t I be laying down and you guys doing this for me?

What pushed me totally over the edge, I’m later laying in bed at night and Paul Dunne, God bless him, is sitting up with me. I can’t sleep and I’m hot and sweaty. I ask him to go get me a towel. He gets me a towel, I sit up and he says, “Oh shit.” I wasn’t sweating, I’d bled through the bandage and I’m bleeding like mad and the pillow is soaked in blood. I’m still bleeding with an Ace bandage around my neck. Why they can’t put a stitch in to stop the bleeding I don’t know. I proceed to raise holy hell, because I’m going to bleed to death here. I’m screaming, “Get me out of here!”

After dawn they bring in a chopper and Medevac me out of Betty. The chopper has racks where you could put one litter over another. They slide me into a rack, put a wounded ARVN above me, and take me to Cam Ranh Bay to the Air Force Hospital. We land and the doors barely slide open and there’s guys right there. They slide my litter out, put me on a gurney, push me down a sidewalk, turn a corner, bang through swinging doors, I remember seeing the word Hospital over it, take a right turn into the first bay, and immediately there are four or five guys working on me.

One of them says, “Where you from?” They say things like that to relax you.

“Minnesota.”

He says, “Oh, I’m from St. James.” It’s a small town in Minnesota. There’s more small talk as they’re putting IVs in me and probing around. They have the blood stopped in maybe a minute.

I have an Air Force doctor, a captain, who’s very attentive. He comes around several times to see me, cleaning me up, probing around some more, and pulling the pieces of metal out of my face. The third or fourth day he tells me he did not take out the bigger pieces because he doesn’t think they’re going to bother me. He says to get at them he’d have to make much bigger scars.

That night while Staff Sergeant Groves is recovering at Cam Ranh, mortars are again falling back at LZ Sherry. An incoming mortar explodes directly on Gun 3, killing Howie Pyle and wounding the entire crew.

Of course I don’t have my journal with me. I write on hospital paper, and then transpose it over into my journal when the guys bring it to me from Sherry. I did not realize until last year, when I was reading my journal again, how I had already stuffed, had internalized all that trauma so completely the very next day. I put it deep down inside me.

Here’s what I write on August 13, maybe 30 hours after I was hit and Stanley died in my arms. You’d think I was in there for a tonsillectomy.

August 13, 1969

The next day I learn of Howie Pyle’s death.

August 14, 1969

I had a couple of visitors today: Chuck Labarbera and Sgt. Cotton came up from Phan Rang. I had phoned Chuck this morning and they brought some of my things up. They told me some bad news too. We were mortared Wednesday morning and Pyle was killed. That was a blow. I guess a round landed inside their parapet and also wounded most of third section. Enge is hurt pretty bad they think. I felt so bad to hear that. God be with them.

They actually told me wrong. It was really Tuesday night that Gun 3 was hit, the evening of the same day my gun was hit in the early morning. Howie died instantly, we called him Gomer you know, and the entire rest of the crew was wounded.

After a few days there were little bitty small pieces of shrapnel still in my face. I’ll always remember this, the first time I shaved I caught one of these little pieces and dragged my razor over it. It hurt like hell.

I spend 16 days in the hospital. There’s a bunch of us in this long ward, we’re laying there and all of a sudden the doors bang open and here comes a guy who says, “Miss America and her court are here and would like to say hello to the guys if they could.”

Everybody sits up and guys are saying, “You got a comb?” Everybody wants to look their best for Miss America and her court.

On the 16th I write five lines and mention I watched some TV, a show I liked watching at home was on. Amazing. I understand now how deep I’d buried everything.

August 12 is a date sacred to the boys of Battery B, and an anniversary each in his own way has commemorated since 1969. Paul Dunne, the crewman who was wounded with Rik that morning, and sat up with him at the aid station, would die three months later from a road mine.

(left to right) Theodus Stanley – killed August 12, 1969

Tommy Mulvihill – wounded five times

Howie Pyle – killed August 12, 1969

Paul Dunne – killed November 19, 1969

March 26, 2014

Rik Groves – Gun Chief – Part Three

THE BOYS OF BATTERY B

STAFF SGT. RIK GROVES

GUN CREW CHIEF

PART THREE

At this point in the drama of B Battery, First Sergeant Farrell climbs on stage. He is one of those characters the troops either loved … or did not love. No one was neutral on the subject.

First Sergeant Farrell

First Sergeant Farrell, I liked him a lot. He was very fair. He had a temper and his voice had an edge to it, but he was always fair. That was the bottom line. If he ever went off on me, I deserved it.

One night I was on guard and he came out and said, “Sgt. Groves, I want you to come with me for a minute.” We went down to Gun 4 and there was a guy asleep on guard. Sgt. Farrell wanted a witness. He shined his flashlight in the guy’s face and said, “You see that?”

I said, “Yeah.”

He said, “OK, I just wanted a witness.”

I had to write a statement. Farrell did it the right way with a witness. The guy didn’t get busted, just a reprimand of some sort, which was pretty light punishment for sleeping on guard.

Early in my journal I was reminded I got hit by a piece of shrapnel during a mortar attack. A mortar exploded right out in front of our gun. A piece of shrapnel hit me right below the right corner of my mouth and knocked my head back. It hurt like hell. I was scared to touch it because I knew enough about shock to know that my jaw might be gone without my feeling it. I could be dying. Finally I got the nerve to touch it. My face was still there and it was warm to the touch but the shrapnel didn’t break the skin – nothing. Either the flat side of the metal shrapnel hit me, or it was a stone. If the shrapnel was from the outside of the round, it’s gonna be flat.

Farrell comes by after the firing stops and asks if everybody’s all right. I say, “I took some shrapnel in the jaw but it didn’t break the skin.’”

He pulls out his pocketknife and says, “Here, let me give you a little nick, draw a little blood, and we’ll get you a Purple Heart.”

I wasn’t looking for a Purple Heart, just telling him the story. I ended up getting a Purple Heart, but not for that.

April 2, 1969 …

… marks the date when the boys of Battery B begin to die.

I was coming back from Vung Tao on in-country R&R when I got the news.

Of course I remembered sitting next to Sherlock back in Phan Rang when we were both new in country and coming out to Sherry together. I would see Steve around the battery. He was assigned to a different gun, but I remember him well. I never knew Percy, he was only in the battery a couple weeks.

Tom Townley was the medic at LZ Sherry when the mine exploded. The following is from Doc Townley ’s earlier account posted August 22, 2013.

I was burning shit at the time, when I heard an explosion and looked up and could see the smoke over the tree line. And I knew something had happened but I didn’t know what. And then all of a sudden I saw a Jeep come flying towards the firebase screaming and yelling, “Doc, Doc, get over here.” Well I ran and grabbed my bag and jumped on the jeep, and they took me out there.

I got out of the jeep and was walking along the side of the road. Farrell probably saved my life. He said, “Doc! Stop! Watch where you’re walking.”

And I stopped.

He said, “You can’t walk over there. Walk on the hardpan.”

I came close to stepping on one of those bombs that when you step on it all the little bombs pop up in the air. I almost stepped on it. The Viet Cong picked up artillery rounds and bombs that never exploded and buried them as mines. There was enough explosives in this one it would have blown my leg off.

But I had to take care of Gulley. He was blown away from here down.

Tom places his hand at his rib cage.

There was nothing there. Nothing. It was gone. His one arm was gone. And he was still alive. Well I wrapped his arm for him, because he saw it. Told him he was going to be all right, that was all I could tell him, you know. I still have dreams about that. But there was nothing I could do, absolutely nothing I could do. There was nothing there to do anything with. You know what I mean? But he hung in there for a good 20 minutes. It took that much time, and he was still alive.

He is silent for a long moment.

The way …. the way … he was blown, it must have constricted the blood flow, enough to keep him alive. He had enough blood in him to keep him alive apparently. Sherlock was already dead. He was gone. There was nothing we could do for him.

They were not the only ones I saw when I was there. I saw a couple of Vietnamese that they brought in and wanted me to fix up. They were already dead.

Judson and another guy they took right down to the helipad at Sherry because they had a helicopter coming in. I did not treat either one of them. I didn’t talk to them or anything. They just sent them right on through because they were mostly superficial wounds.

“Were you the only medic there? ”

I was the only medic, but when they say you’re the only medic it means the only one trained to be a medic. But you had people like First Sergeant Farrell and there was an E7 sergeant there. They had enough experience that they were just as good a medic as I was. So I really wasn’t alone. You were never alone over there. Everybody had your back. Farrell was a little different, but I’ll tell you what, he was all business when he was business. He was 100% business. He was a good first sergeant.

May 17, 1969

Six weeks later two more soldiers die on an airmobile operation at LZ Nora, ten miles north of Sherry. It is a lonely outpost at the top of a barren hill.

Landing Zone Nora

There were just two guns there, my Gun 2, BAD NEWS in the foreground, and another gun. No one can remember the name of that gun. Nora was a small area at the top of a hill. It was such a small area the choppers had to set our stuff down at the bottom of the hill and we had to haul everything up the hill to set up the guns. It was really a bitch. They would bring in our ammo and water blivets and dump everything at the bottom of the hill. You could see how little protection we had if we ever had a ground attack. That’s the same way it was back in January.

Journal entry of May 17, 1969

I am very sorry to write that at 2 AM this morning we had two more men killed. Staff Sergeant Johnson and his loader Lloyd Handschumaker died. It happened out at Nora. Both guns were shooting together in a sort of ‘mad minute’. My gun shot a round that suddenly detonated right over the hooches. It killed Jim instantly. ‘Hand Job’, as we called him, died while waiting for the Dust Off. Mulvihill, Leggett and Bongi were wounded using my gun, and Williams was wounded on the other gun. They said it was a malfunction of a PD (point detonating) fuse.

My gun was involved, but not my crew. On May 7 Captain Marquette, our new battery commander, decided to switch the crews out. So Tommy Mulvihill’s crew from Gun 4 came out and took over my gun, and we rotated back to Sherry and worked Tommy’s gun. The crew from gun 1 came out and took over the other gun.

When the accident happened the guns were shooting nighttime H&I to keep the VC off the perimeter. You can see from the picture there wasn’t much between us and them. The guns were turned roughly 45 degrees to the right from where the picture shows them pointed. So BAD NEWS was aiming just to the left of the other gun. A round left my gun and detonated practically right out of the tube. It killed Jim Johnson and Lloyd Handschumaker on that other gun and wounded Williams. It also wounded Tommy Mulvihill, Leroy Leggett and Tony Bongi working my gun.

At LZ Nora Tommy Mulvihill earned the first of three Purple Hearts. He would be wounded five times over the course of his tour in Vietnam. For Tony this was the first of two Purple Hearts.

Almost Killed a Kid

This is an important story, because I came within a whisker of killing a little Vietnamese kid. We are coming back from town on a convoy. I am in the first truck, which is the second vehicle in the convoy behind the lead jeep. I have ammo in the back of my truck, and there are two or three trucks behind me, and then there is the Dusters’ truck. It is the only truck in the convoy that has nothing in its bed, because they were unable to get their ammo.

All of a sudden there is a huge explosion. I turn around and look back and there’s this huge black ball of smoke drifting into the sky. SOP was you never stop if you get hit, you hightail it out of there. They’d try to take the front truck out, and then the back truck, and then they finish you off. I am the ranking NCO, and I immediately grab my M16 and yell at my driver to take off. I jump out and run around behind the truck to the other side of the road and start heading down there. I’m waving everybody by me yelling GO, GO, GO.

I see a Vietnamese kid running along the rice paddy dyke and there’s an ARVN soldier chasing him. I know that kid set off the mine, a command detonated mine, and I know he killed some of my friends, I know he killed those guys in that truck. I pull up my M16 – I get chills when I tell this story – I pull my M16 up and I flip it on AUTOMATIC and I aim it right at his ankles, and I’m going to let it naturally crawl right up him. I’m gonna kill that little shit. I yell, “DUNG LAI,”, which means STOP. I yell again, “DUNG LAI, DUNG LAI,” and he keeps running. The ARVN is chasing the kid and he is running away. I start to squeeze the trigger, and all I can say is the good Lord had to do it, because I didn’t do it voluntarily. I pull my rifle up and shoot a couple short bursts in the air. The kid stops dead in his tracks. He turns around crying and screaming. The ARVN grabs him and shakes him and I know what he was saying to the kid – If you run away they’re going to shoot you. It turns out the kid didn’t do anything. He was just out there to get candy. I see the chain of events in my head – when the explosion goes off he gets scared and starts running, I assume he had set it off, he killed my friends, now I’m gonna shoot him.

I go back to the blown up truck. The front set of dual tires on each side are blown into the rice paddy, maybe 30 feet away. The explosion opened the back bed of the truck up like putting a cherry bomb in a tin can. There’s diesel and oil running all over. Luckily it was the only truck that didn’t have anything in it. The lead jeep, and my truck that had a load of ammo, and two or three other trucks rolled over that same spot and somehow missed the detonator. The only truck that hits it, not only did it not have any ammo, but my two buddies didn’t have a scratch on them. Their eyes are big as saucers and they can’t hear for awhile, but they didn’t have a scratch.

I almost killed a kid for nothing. I was within an eyelash of killing that kid. I get emotional just saying it.

March 18, 2014

Rik Groves – Gun Chief – Part Two

THE BOYS OF BATTERY B

STAFF SGT. RIK GROVES

GUN CREW CHIEF

PART TWO

In the early morning hours of January 12, 1969 a heavily armed force of Viet Cong launched a ground attack through the southern perimeter of LZ Sherry and immediately in front of a tank providing security for the firebase. Their first objective was to take out the tank with a rocket propelled grenade, then breach the wire and wreck havoc across the compound with more RPGs, AK 47s and grenades. The attack came from the south while the battery was engaged in a fire mission to the north, perhaps manufactured to draw attention away from the initial attack.

We were all on the guns shooting a fire mission facing almost due North. We were in a CHECK FIRE situation while the forward observer was ascertaining whether he needed more rounds on target. We were not actually firing at the moment, but standing around the guns. All of a sudden there was a BOOM, one report. Normally when a tank or howitzer fires there is the BOOM when it fires, and another when the shell hits. To us the single report meant that tank had got hit, or something next to it, and a ground attack could be coming.

We immediately scrambled out of the fire mission and went to our sectors of fire. I was on Gun 2. We spun our gun around almost 180 degrees and started pumping rounds out just over the perimeter, time fuses set for a 50 meter air burst. Our sector of fire was just to the right of that tank and traversing around just a little past the tower out by the road. We had a separate cache of rounds, Charge 1 with the fuses already set very short, because you wanted an air burst and you wanted it close, so close we would get shrapnel back in on us. You could hear it hitting like rocks around us. Once in awhile you’d feel it hit your leg. We had to elevate the tube a little bit because we are shooting over FDC and other hooches. You load, you traverse the tube, and as soon as a new round is loaded you yank the lanyard, and keep on as fast as you can load. Everybody is doing the same thing to their sector of fire, and base piece is putting up illumination.

Air Burst Over Perimeter

Courtesy Bob Christenson

We do that for a few minutes, and we get the command CHECK FIRE, CHECK FIRE. It turned out the tank had not gotten hit. What we heard was a canister round being fired from the tank.

I later talked to the tanker who fired the round. He was sitting up in the turret that morning on guard duty and looking through his starlight scope. He said he saw a VC at the closest row of concertina wire right in front of the tank maybe 20 feet away, and more behind him. Remember we had three rows of concertina wire, and each row had three coils – two next to each other and one on top. Between the rows of concertina we had rows of tangle-foot wire. We had empty C-ration cans with stones in them for noise, we had trip flares, we had a few phu gas barrels. Well they came up to right in front of that tank and the tanker did not see them until the last minute.

At night they always kept a canister round loaded, a gigantic 90 mm shotgun shell loaded with steel balls. He told me he just lowered the tube and fired. One second later and the VC would have fired point blank into the tank. The canister round blew nine or ten VC literally to pieces. The individual holding the RPG would be known as “Head and Shoulders”, because that’s all that was left of him tangled in the wire. I don’t know who made up the name, but it stuck.

These guys would have come in, taken out the tank, but most importantly, they’re coming in and in another 30 meters is Fire Direction Control. They take out the FDC radios and now we can’t call for help, can’t call in Spooky or gunships. Then you’re fighting for your life. That tanker being alert on guard duty saved a lot of lives, no question.

I went out early the next morning to take pictures. I took six pictures, that was it. When you see people in pieces, even if it’s the enemy, that’ll do something to you. I didn’t feel it then, they’re the enemy, they’re the bad guys. I look at my picture of Head and Shoulders, with shards of flesh hanging from the concertina, an absolutely grisly picture. At the same time when it happened I thought, Thank God for that guy in that tank turret. Thank God we got those bastards. In combat it’s a different mindset.

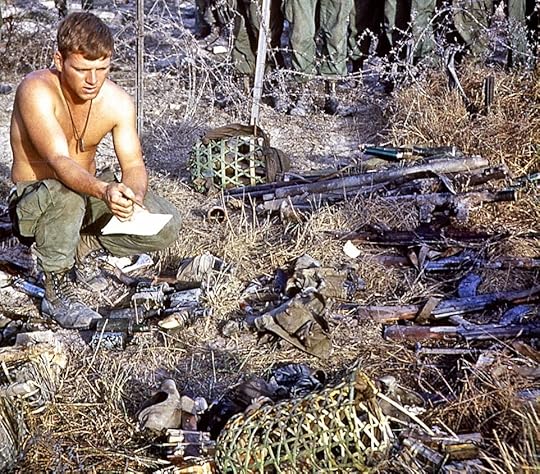

What the VC Carried

Later they found seven or eight more bodies farther back and a little more to the left, evidently killed by my gun. They were massing out there. I never saw any bodies that my gun killed, it’s just what I was told. I also heard that they found a body or two out near the chopper pad.

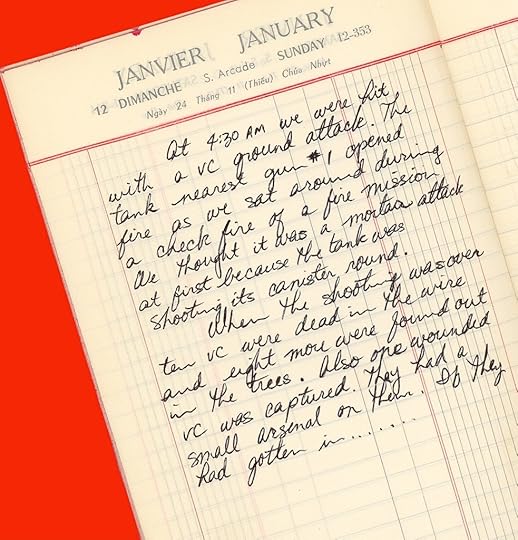

On March 6, the day I began my journal, I went back to the January 12 page and wrote about what I remembered and what I was told about that morning, because it was a significant event.

Added to Journal on March 6, 1969

Later that morning we left to go on an air mobile operation, so I was not there when the battalion commander came. I was not there when they brought a bulldozer in to dig a trench and push the bodies in . . . or whatever they did with the bodies. I didn’t see any of that. Our guns had already left on the mobile operation. It’s really significant that we had two or three sling loads of 105 ammo out on the chopper pad ready to go in the morning. It could have been real ugly.

The last thing that goes on top of this is we got airlifted out and set down in the middle of someplace with far less security than we had at the firebase. We landed and I remember there was cactus and being surprised to see it in tropical Vietnam. You think we were jumpy … Holy Cow. Hard on the heels of killing a bunch of VC in the wire we’re out on an operation.

The only thing you have out there is an incomplete parapet around your guns because your hooches form the parapet around the gun, and there’s gaps between the hooches. On top of a makeshift ammo bunker there’s an M60 machine gun and it’s pointing out to nothing. There’s just a coil of concertina wire about 20 feet out from the guns. There’s no added perimeter security . . . we are it.

On Operations Later That Morning

I remember being on guard a couple nights after the attack on Sherry. I’m on the M60 and looking out into dead black dark. Everything that moves is a bad guy. Sgt. Calvin Smith walked up behind me and said something and I must have jumped six feet. I said, “Damn it, don’t ever do that again.”

He laughed.

After the attack Rik drew a map of LZ Sherry for himself and to send home to his family. It shows the guns oriented north while the attack comes from the south directly in front of a tank, the three strands of concertina wire, the proximity of the hooches in easy reach, and the chopper pad where the ammo sat ready for the airmobile operation and where another body was found.

Map of Firebase and Attack of January 12, 1969

March 12, 2014

Rik Groves – Gun Chief – Part One

THE BOYS OF BATTERY B

STAFF SGT. RIK GROVES

GUN CREW CHIEF

PART ONE

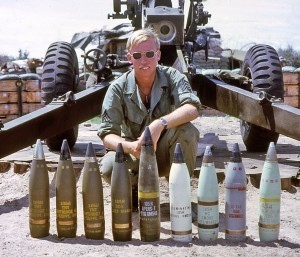

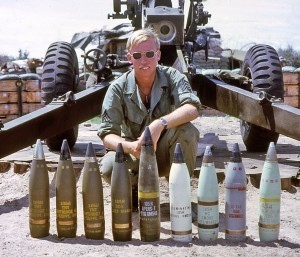

Staff Sgt. Groves with the many shells and fuses used in Vietnam

Rik ’s time in Vietnam begins a bloody period for B Battery. A Viet Cong ground attack begins the year in January of 1969, followed that summer and fall by the deaths of seven boys, and the wounding of over half the firebase. Rik still carries shrapnel in his neck, chest and arm, souvenirs he wished he ’d left behind. He did bring back something that grows more precious with the years, a daily journal covering the last six months of this tour.

PART ONE

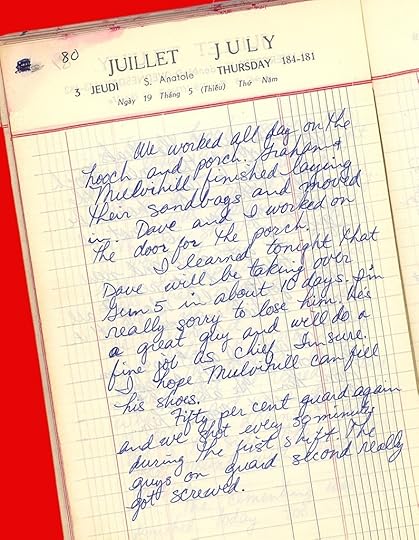

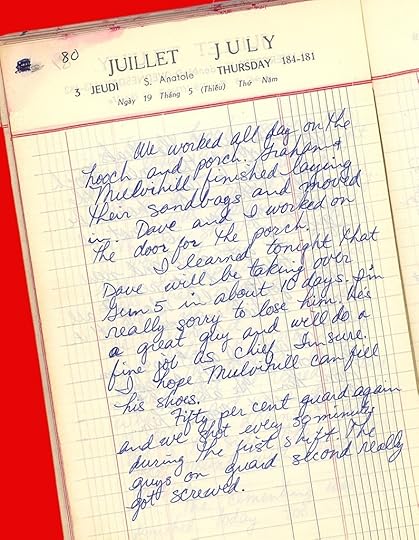

The Journal

I got to LZ Sherry in mid September 1968, and began my journal on March 6, 1969. The last entry was on September 14 on my way home. The book I wrote in was one I had someone bring back from a convoy to LZ Betty. I just said get me a journal or something to write on. They brought me back this thing that said AGENDA 1969 on the front. It’s not a journal, it’s more like an accountant’s book. But it had the date on each page, and that’s all I needed. The pages had columns on them, which I just wrote over. I wrote in it every day. It got interrupted when I got wounded and was in the hospital. I did not have my journal, so I wrote on hospital paper and then transcribed it back into the journal after one of the guys brought it to the hospital.

On many of the pages of my journal I am waxing sad about missing my wife and so on. I don’t regret that, except that I wish I had spent more time writing about the details of what was going on. By the same token it is an unimpeachable source of things that happened on certain dates. Nobody can argue about something that happened, because I’ve got it written down. I wrote down when we got hit and I’d write “10 to 12 rounds.” Or I’d write when somebody came into my section, or when somebody got promoted. Like Fitchpatrick, he was my gunner for a long time. We became good friends, and then he went to Gun 5 and took over as the gun chief. I can tell you the date that happened because it’s in the book.

July 3, 1969

Starting on the 40th anniversary of when I began the journal, March 6, 2009, I published each day’s entry in an email for the guys I had met up with on Veteran’s Day Weekend in 2007: James Sprout, Tommy Mulvihill, Hank Parker, Jim Kustes and Howie Pyle’s brother, Gregg. Gregg has become like a brother to all of us. Dave Fitchpatrick couldn’t make it to Washington that year but had been with the guys the year before so he was on the mailing list, too. I called the emails ’40 Years On . . .’

The Road To Vietnam

I was married in September, 1967; I was drafted and went into the Army on Thanksgiving week 1967, so we were together only about 2 ½ months as a married couple before I went into the service. I wasn’t quite 21.

I had gone to the University of Minnesota for a year, and then to radio broadcasting school. I was immediately 1A when I graduated and right away got drafted. I hoped to get stateside duty or Germany. I said to myself, I don’t want to go to war, but if I’m called it’s my duty and I’ll go. I had a couple of friends who said if they got drafted they were going to Canada. Our friendship was never the same after that.

I went to Basic at Ft. Leonard Wood and artillery training at Ft. Sill. They called a bunch of us in and told us that we qualified for NCO school. They said, “Gentlemen, once you graduate to NCO school you will go to Vietnam. That’s what we’re training you for, we need NCOs.” I went to Vietnam as a sergeant E5, and had been married just over a year. I was 21 when I went to Vietnam, older than most.

I went over with a guy I had become very good friends with, Barry Holland, who was from Sacramento California. He had gotten married while we were in NCO school, and our wives stayed together in Minnesota. Barry and I went over together hoping we’d get assigned to the same unit. That didn’t happen.

I’ll always remember flying into Vietnam. I went by Flying Tiger Airlines, which was primarily a transport airline, but it also flew troops over. We couldn’t land at first. We circled Bien Hoa Airbase and I see these flashes on the ground, and I think they’re firing H&I down there. We finally land and one of the most vivid memories is when they opened that door there was this blast of damp, stinky air of Vietnam. We go down the stairway, it’s the middle of the night. They put us on these long benches underneath a tin roof, open on the sides. The guy up at the front says, “Sorry to keep ya’ll waitin’, we were gettin’ mortar and rocket fire while you were getting ready to land so we had to hold you up for awhile.” I thought, Oh God, great! That was my initiation into Vietnam.

Barry got assigned to the 25th Infantry Division and I went to First Field Force. The first place I went to was Nha Trang, and the first guy I met and hung with for a day and a half was Steve Sherlock. Steve and I walked around Nha Trang, you could go into town at that time, and it was a beautiful city. We ended up both getting assigned to the 5/27 and we both went to Phan Rang. And this is one of my strong memories. We go into a room in Phan Rang – I’ll always remember this as one of the things that will stick with me forever – we sit down on benches and Steve Sherlock is next to me. An officer is up front telling us a little history of the battalion. He proceeds to tell us that we had only lost one person in the battalion since it had been in Vietnam (since late 1965). When he says that – when I remember this I still get chills – when he says that I get this chill up my back and I say to myself, I’m going to get hit over here. I don’t have the sense I am going to die, necessarily but I have the very strong feeling that I am going to get hit. My feeling does not differentiate whether I am going to die or get wounded, but I have the sense I’m going to get hit over here. Little do I know that the guy sitting right next to me on my right, rubbing elbows, would be the next guy to die.

Prayer of the Gun Chief

At B Battery I was assigned to Gun 3 at first, base piece, under Sergeant Lawler. He was leaving shortly, and then I took over as chief when he left. Before long they moved me over to Gun 2 as chief, where I stayed for the rest of my time in Vietnam. I was so concerned that I would make a mistake and do something to get one of my men killed or wounded. I was really worried. It was the responsibility of leadership. I took it real seriously. Every day I said to myself, “God, help me not make any mistakes that get guys hurt.” That was my biggest worry. It took my mind off myself.

Rik Groves – Gun Chief

THE BOYS OF BATTERY B

STAFF SGT. RIK GROVES

GUN CREW CHIEF

Staff Sgt. Groves with the many shells and fuses used in Vietnam

Rik ’s time in Vietnam begins a bloody period for B Battery. A Viet Cong ground attack begins the year in January of 1969, followed that summer and fall by the deaths of seven boys, and the wounding of over half the firebase. Rik still carries shrapnel in his neck, chest and arm, souvenirs he wished he ’d left behind. He did bring back something that grows more precious with the years, a daily journal covering the last six months of this tour.

PART ONE

The Journal

I got to LZ Sherry in mid September 1968, and began my journal on March 6, 1969. The last entry was on September 14 on my way home. The book I wrote in was one I had someone bring back from a convoy to LZ Betty. I just said get me a journal or something to write on. They brought me back this thing that said AGENDA 1969 on the front. It’s not a journal, it’s more like an accountant’s book. But it had the date on each page, and that’s all I needed. The pages had columns on them, which I just wrote over. I wrote in it every day. It got interrupted when I got wounded and was in the hospital. I did not have my journal, so I wrote on hospital paper and then transcribed it back into the journal after one of the guys brought it to the hospital.

On many of the pages of my journal I am waxing sad about missing my wife and so on. I don’t regret that, except that I wish I had spent more time writing about the details of what was going on. By the same token it is an unimpeachable source of things that happened on certain dates. Nobody can argue about something that happened, because I’ve got it written down. I wrote down when we got hit and I’d write “10 to 12 rounds.” Or I’d write when somebody came into my section, or when somebody got promoted. Like Fitchpatrick, he was my gunner for a long time. We became good friends, and then he went to Gun 5 and took over as the gun chief. I can tell you the date that happened because it’s in the book.

July 3, 1969

Starting on the 40th anniversary of when I began the journal, March 6, 2009, I published each day’s entry in an email for the guys I had met up with on Veteran’s Day Weekend in 2007: James Sprout, Tommy Mulvihill, Hank Parker, Jim Kustes and Howie Pyle’s brother, Gregg. Gregg has become like a brother to all of us. Dave Fitchpatrick couldn’t make it to Washington that year but had been with the guys the year before so he was on the mailing list, too. I called the emails ’40 Years On . . .’

The Road To Vietnam

I was married in September, 1967; I was drafted and went into the Army on Thanksgiving week 1967, so we were together only about 2 ½ months as a married couple before I went into the service. I wasn’t quite 21.

I had gone to the University of Minnesota for a year, and then to radio broadcasting school. I was immediately 1A when I graduated and right away got drafted. I hoped to get stateside duty or Germany. I said to myself, I don’t want to go to war, but if I’m called it’s my duty and I’ll go. I had a couple of friends who said if they got drafted they were going to Canada. Our friendship was never the same after that.

I went to Basic at Ft. Leonard Wood and artillery training at Ft. Sill. They called a bunch of us in and told us that we qualified for NCO school. They said, “Gentlemen, once you graduate to NCO school you will go to Vietnam. That’s what we’re training you for, we need NCOs.” I went to Vietnam as a sergeant E5, and had been married just over a year. I was 21 when I went to Vietnam, older than most.

I went over with a guy I had become very good friends with, Barry Holland, who was from Sacramento California. He had gotten married while we were in NCO school, and our wives stayed together in Minnesota. Barry and I went over together hoping we’d get assigned to the same unit. That didn’t happen.

I’ll always remember flying into Vietnam. I went by Flying Tiger Airlines, which was primarily a transport airline, but it also flew troops over. We couldn’t land at first. We circled Bien Hoa Airbase and I see these flashes on the ground, and I think they’re firing H&I down there. We finally land and one of the most vivid memories is when they opened that door there was this blast of damp, stinky air of Vietnam. We go down the stairway, it’s the middle of the night. They put us on these long benches underneath a tin roof, open on the sides. The guy up at the front says, “Sorry to keep ya’ll waitin’, we were gettin’ mortar and rocket fire while you were getting ready to land so we had to hold you up for awhile.” I thought, Oh God, great! That was my initiation into Vietnam.

Barry got assigned to the 25th Infantry Division and I went to First Field Force. The first place I went to was Nha Trang, and the first guy I met and hung with for a day and a half was Steve Sherlock. Steve and I walked around Nha Trang, you could go into town at that time, and it was a beautiful city. We ended up both getting assigned to the 5/27 and we both went to Phan Rang. And this is one of my strong memories. We go into a room in Phan Rang – I’ll always remember this as one of the things that will stick with me forever – we sit down on benches and Steve Sherlock is next to me. An officer is up front telling us a little history of the battalion. He proceeds to tell us that we had only lost one person in the battalion since it had been in Vietnam (since late 1965). When he says that – when I remember this I still get chills – when he says that I get this chill up my back and I say to myself, I’m going to get hit over here. I don’t have the sense I am going to die, necessarily but I have the very strong feeling that I am going to get hit. My feeling does not differentiate whether I am going to die or get wounded, but I have the sense I’m going to get hit over here. Little do I know that the guy sitting right next to me on my right, rubbing elbows, would be the next guy to die.

Prayer of the Gun Chief

At B Battery I was assigned to Gun 3 at first, base piece, under Sergeant Lawler. He was leaving shortly, and then I took over as chief when he left. Before long they moved me over to Gun 2 as chief, where I stayed for the rest of my time in Vietnam. I was so concerned that I would make a mistake and do something to get one of my men killed or wounded. I was really worried. It was the responsibility of leadership. I took it real seriously. Every day I said to myself, “God, help me not make any mistakes that get guys hurt.” That was my biggest worry. It took my mind off myself.

March 5, 2014

Ronnie Thomas – Forward Observer, Gun Chief

THE BOYS OF BATTERY B

SGT. RONNIE THOMAS

FORWARD OBSERVER & GUN CREW CHIEF

Sgt. Ronnie Thomas

Wounded twice and exposed to hostile action for most of his tour, Sergeant Ronnie Thomas describes his life today.

When I got back, when I landed at Seattle, Washington, I got off that plane and I made myself a promise. That place was gonna stay back there. Just the happy memories are coming with me. And that’s what happened. It hasn’t bothered me. I haven’t had any problems whatsoever in my mind over it.

When I got back my wife and I got married. She graduated from William and Mary, she’s a school teacher, retired. Been married for 44 years. There you go, I don’t know how I put up with her that long. She is in the room listening and he laughs. Likely it’s the other way around.

I live in Yorktown, Virginia. I been living around Yorktown and Newport News all my life. I was born in Emporia, but my dad moved up here and started working in the shipyard. I have two farms about 80 miles from here. I go out and deer hunt on weekends. It’s relaxing for me to get out in the woods. Take my tractor and bush hog and take care of my roads. That’s just things I enjoy doing. I walk five miles every day, been doing that the last 15 years, my dog and me. I got a dog as old as me almost. Life is good.

The Cigarettes Didn’t Help

I went over January 10th, 1968 and the TET offensive started January 30th. So I got baptized. Then we road marched from Qui Nhon in trucks and went all the way to 90 miles outside of Saigon to LZ Judy, near a place called Phan Thiet. We had the shit shot out of us the whole way down. But we made it fine.

I was not at the battery all the time. I was also a forward observer with the 101st Airborne Infantry. I would call in artillery for them. We were very accurate. We could hit a gnat in the ass at seven miles (maximum range of the 105 howitzers of B Battery). I’d go out sometimes in the field, and then sometimes I’d go up in a helicopter, I was all over that place. We’d go out for two, three days. I carried the radio for the captain. He and I became real good friends, and we’re good friends today. We had a lot of the same interests. I was all-state in football as a freshman, and he was a big football player. Neither one of us were married at the time. The captain gave me his patch. He took the patch right off his shirt and put it on mine.

To surrender one’s combat patch to someone from another unit was a mark of deep friendship and respect.

When I carried the radio and kept getting shot at I said, well you know it’s this radio. The Viet Cong figured no radio, no artillery. I didn’t smoke, and you know we got two cartons of cigarettes a month in our rations. We had an ARVN soldier with us, so I gave that ARVN my cigarettes and he carried the radio.

But I still got wounded. I got shrapnel pretty bad in the leg, it was a nasty wound to my thigh. I went to Cam Ranh Bay for about a month and a half. I didn’t want to go home so I came back to B Battery and finished up my tour as a section chief on a gun.

Unhealthy To Mess with Thomas

I used to be a rambler, I’ll tell you. I was five foot seven, weighted 215 and had a 30 inch waist – a tough dude. There was this one black guy, he was buffed up and about six foot three. He always wanted a piece of me, because I always had the reputation of the toughest guy in the whole battery. I don’t know if I was or not, but everybody liked me, and he never would take the step. I didn’t dislike anybody, until they made me dislike em.

There was a guy who was my best friend, Pop Hesson from Carthage, Tennessee. He’s just an ol’ country boy that lived in the mountains. I became real good friends with him. I went into town one time and came back, and there were two black guys just punchin’ him in the chest. The black guys, I was their boss, they were in my unit. I said, “What the hell is goin’ on here?”

Pop Hesson said, “These guys are nuts. They been drinking.”

So I stepped in between ‘em and said, “Ya’ll get your ass out of here, and Pop you go on.”

And then one of ‘em hit me. And when he hit me, I went on him and broke his ribs. And the other one pulled the antenna off a jeep and hit me across the back with that antenna. I went off on him too. They medevac’d both of them out of there, and neither one of them ever came back. I didn’t do this stuff until somebody did it to me.

The next day things had calmed down, and I can tell you a story that will really make you smile …

German Practicality

The First Sergeant came by and said we’re having an IG inspection. Some general or colonel or somebody is coming out here tomorrow in a helicopter to look around. I was a sergeant and told the guys in my platoon, “Look, I want you all to put on some good clothes. You walk around in rags. Put on good clothes, you don’t have to be the best in the world, but git your boots a little bit better and just see what you can do.”

There was a German that was in my platoon. His name was Altenberg. He was huge, about six foot three and just all man. He was about the only one in the whole battery that could handle me.

So I was walking around and checking parapets and checking guards, and everybody had done what they were supposed to do, except Altenberg. His boots looked like shit and they were tore all to pieces. So I took his boots over to my hooch and I shined them up so they looked good. And this is the truth, I carried them back and put them under his bunk.

The next day the IG inspector landed – he was a general. They fell us all out in front of our hooches, and this general started walking by. I hadn’t paid any attention until then, but I saw Altenberg was standing there barefooted. I thought, Jeeesuz. That’s the kind of guy he was. He really didn’t give a damn. He was standing there barefooted, and I said to myself, Oh shit.

The general stopped in front of Altenberg, looked down and said, “Son, where’s your boots?”

Altenberg said, “I throwed ‘em out in that damn rice paddy right there.”

The general said, “Why?”

Altenberg stepped out of line and pointed at me and said, “You see that sergeant down there?”

The general turned his head in my direction and said, “Yeah.”

“That son of a bitch polished my damn boots last night. The VC can smell that shit so I throwed ‘em in the rice paddy.”

The general said, “Good job, son.”

Then the general come by me and I thought, Jesus Christ I’m gonna get my ass eat out. He shook my hand and said, “Good job, buddy.”

After that the general came by and talked to people one-on-one. He was the nicest guy in the world.

Altenberg

Hazards of Air Mobile

One time they took us out in the mountains, and the Montagnards and indigenous forces cleared out a big landing zone for us. We put two guns there, and we stayed there four days, firing all four days. We got mortared during the day and every night. And then they came to pick us up with a Chinook to take us back to LZ Judy. The whole gun crew was in there, with the howitzer and a sling of ammo hanging below it. At about a thousand feet in the air that thing started vibratin’ and jumpin’ and jimpin’. It was droppin’ and vibratin’, and I thought my time was up then. They had to cut the whole load loose, and the gun and ammunition and everything hit the ground, and we got out of there. Then they called an airstrike in on it, so the VC couldn’t get it. Between the gun and the ammo and the whole crew in there, I guess it was overloaded. That all happened about four miles outside of Phan Thiet.

Chinook With Howitzer and Ammo Load

Courtesy Rik Groves

Vietnamese Cuisine

This was funny. When we were on that operation in the mountains we had South Vietnamese troops on the perimeter, and they came back in one day after killing a Viet Cong, but you know what tickled them to death? They had two big ol’ bags full of bullfrogs. Man, they thought they had done something. They all got together and cooked them bullfrogs up, it smelled like shit. I mean they were nasty bastards.

Then we’re on convoy going through a village one time. I got out of the truck and was walking and ol’ mama-san’s got a big ol’ pot boiling, big iron pot like we’d cook a stew in. Mama-san reached in there with a pair of tongs and pulled up this big ass duck egg. She said, “You want, GI?”

I said, “Noooo.”

She cracked the top of that thing out and sucked that duck out of there and chewed it feathers, head, guts and all. Geemaneechristmas, it almost made me sick.

Helping A New Lieutenant

We had a lieutenant that came in that acted like he just came out of charm school. He was giving orders and doing all the wrong things the wrong way. He was hounding people, not talking to them like men. He was just a shave tail, all dressed up and looking pretty. And here we were in a combat zone, all nasty, hadn’t taken a bath or a shower. The first two weeks we put up with it, we thought he would straighten up.

He had gotten onto one of my people for some little crap that didn’t mean anything, and I finally had to talk to him. I was kind of rough and tough, I said to him, “Look buddy, you need to chill out, and you and I need to sit down and talk.”

“What do we need to talk about?”

I said, “Your ass more than anything else.”

He said, “I’m your lieutenant.”

I said, “Yeah, that’s what we need to talk about. You’re going to lose your ass if you keep being an asshole.”

We sat down and talked and I told him, “If you got a problem with my people I’d appreciate it if you’d come to me.” After that he came around.

A Nano-Second Away

Here’s another good story for you. We took two guns and went up to Tuy Hoa and we set up in this school yard. We fired illumination. It was a hot area, so I had people on guard duty with M60 machine guns on the perimeter. A guy in my platoon, his name was Scott, big, dumb, he really wasn’t all there. I don’t know how he got into the military. He smoked a pipe. I went out on night checking and Scott was sitting there and I said, “You need to go take a break or anything, I’ll sit here.”

He said, “Yeah, I gonna take a piss.”

He was dumb as a rock, he really was, but I really thought a lot of him and I took care of him. He goes out, and you know what he did? I didn’t see it, but we had concertina wire out there and he somehow without me seeing him walked right in front of that gun outside the barbed wire to take a leak. I looked and I saw a shadow moving out in front of me. I didn’t know who was there. So I took the machine gun and I said, “Who’s there?” I yelled several times for him to halt. I was a nano-second from pulling that trigger on him.

Finally he said, “It’s me, motherfucker.”

I was a nano-second from cutting him in half, he wasn’t twenty yards from me. That’s the scardest I ever been – almost killed one of my own men. If I’d a killed him I would never have forgiven myself. I thought a lot of him. It scared me so bad when he came back I smacked him around for twenty minutes.

PFC Scott and Sgt. Thomas

February 26, 2014

George Moses – Battery Commander – Part Five

THE BOYS OF BATTERY B

GEORGE MOSES

BATTERY COMMANDER

PART FIVE

Captain Moses stayed in the Army after Vietnam and retired a full bird colonel in 1983. He has a lot to say about leadership. He seems to have learned from every commander he served under and from every tight spot in his career.

The Magic Hold of Leadership

When we moved into LZ Judy in January of 1968, just before Tet, we didn’t put anything underground, we just built our hooches up on top. The ground was hard pack alluvial plain material, like concrete for the first foot or more, and the monsoon rains would flood any hole you had in the ground. We’d been at Judy for a couple months when Lieutenant Colonel Elliott, the new taskforce commander, came out to inspect. He wanted everything underground, saying to me, “Look George, it’s better to have wet feet than to be shot. Let’s get everything down to no higher than waist level.”

That meant we had to dig in everything. One of my pictures shows me digging a hole for my own hooch. That damn ground was so hard you just had to beat the hell out of it to get below that crust. Once you got below the crust you could dig in it. I couldn’t ask these guys to dig me a hole. The hell with it I’d dig my own hole.

Captain Moses Digging His Hooch Hole

We had a lot to dig in. Every one of those hooches had to be taken down to the level of that one in the picture way off on the left. Of course we got it done.

“You may be the first and only West Point graduate to dig his own hooch hole.”

It just seemed like the right thing to do. I couldn’t ask the guys to dig my hole for me. I’d ordered them to dig their own; to dig mine too would have been a shitty deal.

That’s not to say Captain Moses believed in equality.

At Qui Nhon I had a separate officers mess built and insisted they eat separate from the NCOs and the rest of the men. I did that because officers need to talk about officer things; and NCOs need to talk about NCO things. That doesn’t mean we don’t talk during the day. But at meal time that’s the time to share things, and you may want to share things you don’t want the other group to know about. In today’s Army that probably would not fly very well. At the time for me it made sense.

I remember my old battalion commander at Ft. Benning, Colonel Bishop, telling me, “There are officer things and there are NCO things, and there are times when they shouldn’t mix.” He was an old WWII warrior and I wasn’t about to argue with that.

Bishop had three rules. Never give an order you couldn’t enforce. Never give an order you wouldn’t do yourself. And an officer never fools around with an enlisted man’s wife. He looked at all of us on his staff and said, “And I want all you young bucks to stay away from my mama.” He was a good man and a good leader.

There was another incident that I have not talked a lot about. It grew out of my respect for Bishop and what I learned from him. Bishop was a big advocate that a commander of an outfit had a magic hold on soldiers. He said it’s the thing that happens when you go to a change of command. Before the colors are passed every eye is on the old commander, not the new one. Then once the colors pass every eye is on the new commander, not on the old one. So when you’ve got a bad thing going on, the only way to get ahold of it as a commander is to get in the middle of it yourself.

We had an incident one night at LZ Judy. One of my young troops was on guard duty in a bunker that had a 15 foot walkway down into the bunker, so that you were down on field of fire level through the barbed wire. It was late at night. The first sergeant came to me and said, “Sir, we got a problem with a guard post. He’s threatening to kill himself, and he’s gonna kill anybody that comes down there to mess with him. They tried talking him out of it, but he’s not having any of it.” How in the hell was I going to handle this? What would Bishop do? There was only one damn way this was gonna resolve. The kid would shoot himself, or he’d come out on his own. But while this was going on we had a jeopardized guard post out here, and that put all of us at risk.

I said, “OK.” I got up, got dressed and went down to the bunker entrance and I called the young man’s name out and I said, “This is Captain Moses, I’m here and I understand you’re having a rough night.” He told me he had gotten a letter from his girlfriend that caused him a lot of anxiety. I said, “Look, I’m gonna come down and talk to you. We need to talk this out. I’m not armed and I’m not going to hurt you or anything. I just want to sit down and talk this over.”

He didn’t say anything. I’m thinking to myself, Well, if I’m going down I better do it. And about that time you know how fear gets ahold of you. The hair on the back of my head went up. My cheeks went flush. My spine was trembling. But I walked down that damn ramp and I said to myself, Goddamn, the last thing I see might be the flash out of an M16 for all I know. I walked in and fortunately he was sitting down. There was just enough light to make him out sitting in the back of the bunker with the M16 butt on the ground between his legs. I think he was just resting. I said, “Why don’t we just sit here and talk awhile.”

He said, “Sure, sir, have a seat.”

We just started talking about his problem. His girlfriend had written him a letter telling him she was leaving him and he was pretty distraught. By this time too the entire battery was getting a little worn out. I was even in my own letters beginning to see things a little negatively. I remember commenting recently after reading my old letters that I could see my energy level dropping.

Anyway, we talk for 15 maybe 20 minutes, a long time. I finally said, “You know, look, you’re gonna be just fine. We’re gonna forget about this little problem tonight. You go back to your section and nobody’s going to say anything to you about this. You just go on with your duty and do it the way you know how, and when you get back home you’re going to find somebody that’s worthy of you.” That seemed to calm him down. I came walking out with him.

The first sergeant had a replacement for him, the replacement went on duty. I told the section chief to take him back to his section and let him get some rest. Then I told the first sergeant, “I don’t want anybody in this battery to say a damn thing to him or anyone else about this incident.” And they didn’t and the man worked out just fine. But I’ll tell you what, it scared the shit out of me. That’s where my time with Bishop paid off.

There were other incidents. We were going to be inspected one day by the First Field Force commander. The night before we had a fire mission, and somehow the powder pit caught on fire. Everybody was un-assing from the ammunition bunker and running and yelling, “Fire, get away.” I looked at the powder pit and I could see that the fire was burning almost straight up. It wasn’t throwing stuff into the ammo bunker, but it was searing the bunker beam and sandbag walls. I thought, We can control this. I jumped up and ran over with a shovel and started throwing dirt around it and started tamping out the fire that was on the sandbags. When others saw me they all began coming back and we got it under control. We had some black wood and sandbags for the inspection the next morning, but it all worked out.

Now that came from when I was a cadet and had gone to Germany as a third lieutenant in the 3rd medium tank battalion up in Friedberg. We went to Grafenwoehr for 30 days and I had a tank platoon. During the bivouac out in the field we had the old M-48 tanks that had gas drums on the back mounted on steel racks. They would leak gasoline down into the engine well. Every now and then one of these damn things would catch fire. This particular company commander had burned up two of those tanks on other exercises.

In the company mess area late one night the mechanics were working on this tank, and the damn thing caught on fire. Everybody ran … except the company commander. He looked at that and started yelling, “No. No.” He ran over and he got into the driver’s seat with the thing flaming in the engine well. He started the engine and moved that tank out of the bivouac area. When everybody saw that they all came back, got fire extinguishers and got the fire under control. Damn, that took courage. But maybe that’s why officers were there. Maybe that’s why our NCOs were there. To be able to get those kinds of things under control.

The powder pit incident in Vietnam caused me to do the same thing under different circumstances. That flashed through my mind. I could see that company commander grabbing that burning tank and driving it out of the company area. That made me believe that the way you conduct yourself day to day is affecting others in the battery in ways you can’t predict. It creates a mindset to make good things happen if you provide a good example.

I sit down and think about those things. Those leadership incidents I saw as a young cadet and the ones I experienced with Bishop. They stuck with me, and I don’t think it was always conscious. I don’t talk a lot about these incidents, but I think it makes a point about how you affect the future of people you are leading.

At one of the reunions we had at Ft. Sill, I was a colonel by then, a young soldier came up to me and said, “Colonel, when you were on the firebase you would walk around talking to people. That always made us feel safer.”

I told him I was glad to hear that because I didn’t do a lot of socializing with soldiers. Occasionally we’d go to a movie and there would be some banter, but I didn’t do a lot of socializing, beer drinking with them and that kind of thing. I would take care of them and I would talk to them and deal with their problems. That also came from Bishop. There were times when we were in a rear area when we had a good time together. But when we were on a firebase conducting missions it wasn’t a social thing. They expected you to help them through this thing alive.

February 19, 2014

George Moses – Battery Commander – Part Four

THE BOYS OF BATTERY B

GEORGE MOSES

BATTERY COMMANDER

PART FOUR

Fast on the heals of earning the Valorous Unit Award for its performance during the Tet offensive, B Battery experienced a tragic incident that could have been catastrophic had it not been for Captain Moses.

The Incident

I said I’d tell you about the one incident we had in March, after Tet. There was a small village next to us at LZ Judy. The population of that village was Catholic and Buddhist. The Catholics had moved south out of North Vietnam when they established the demarcation line separating North and South Vietnam after the battle of Dien Bien Phu. The negotiated settlement allowed people to move one way or the other. There was a Catholic priest that moved his parish from North Vietnam down to this little village. So half the village was Catholic, and half was Buddhist.

The Catholics were gathered on the west side of the village, and the Buddhists were on the east side. There was no formal demarcation, but it was clear there were two types of people there. In the village there was a regional forces infantry platoon led by a lieutenant, a former Viet Minh major who came south with the Catholics. Over time the Catholic parish had been winnowed down by snipers operating out of the tree lines around their rice fields. They were about half of their original members that came south.