Captain Hank Parker – Battery Commander – Part One

Captain Hank Parker

PART ONE

Captain Hank Parker served two tours in Vietnam. These stories in all their parts cover his first tour from November, 1968 to November, 1969. It was during this first four that he served with B Battery. Among the many awards and medals he earned on this tour are:

The Silver Star

Three Bronze Stars – two with “V” Device for Valor

The Air Medal

The Vietnam Gallantry Cross with Bronze Star

The Purple Heart

On his second tour he earned another Purple Heart and the Combat Infantry Badge.

When I got to Vietnam I served a long apprenticeship with the infantry before becoming XO and then battery commander of B Battery. I was an artillery forward observer (FO) on search-and-destroy missions with the Special Forces; and I went on airmobile operations with two South Vietnamese infantry battalions (ARVNs); and then accompanied the 3/506 airborne infantry as it took on two battalions of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). On one of my efficiency reports the battalion commander said that I’d become a seasoned combat officer. I think that is how I ultimately got to be battery commander at LZ Sherry as a first lieutenant.

Preparation in Hawaii

Before Vietnam it was significant that I did a tour in Hawaii with an artillery battalion attached to the 6th Infantry Division. The battery commanders were all seasoned Vietnam vets. My commanding officer was Captain James Schlottman, who had been a forward observer in the bitter fighting in the Ia Drang valley, portrayed in the book We Were Soldiers Once … and Young. He did not talk about Vietnam a lot, but when he did I listened. I used one of his lessons in Vietnam when I was out with the infantry – Delta Company of the 3/506 – and my guess it saved some lives. I was on a special artillery test team, where I practiced aerial observation for mobile artillery positions. By the time I got to Vietnam, what most guys had to learn in country, I already had.

First Things First

The brave person that I am, the first thing I do when I got to Vietnam is find a chapel and go to a service. I ask the priest if he has a rosary and he gives me one. It is in a plastic bag and I carry that rosary with me day in and day out. It never gets wet. I keep it in my breast pocket and it is with me the whole time. To me that is very important, because I had gone to a Catholic seminary for three years and religion is important to me. When I get into situations of life or death, what am I going to do? I want to make sure I am in an OK place with my faith and with my God. That’s the first thing I do when I got to Vietnam – make sure I am in an OK place.

I keep it in my breast pocket where I can touch it. The times when I am particularly scared I touch it for solace and to be reassured. It is a good way to ground myself. To make sure I stay in the here and now and make sure things are OK.

I am concerned mostly with the safety of everyone around me, that the decisions I make be logical, at the same time that I keep in mind my humanness and my compassion, and that I not go against my principles, my own beliefs. The rosary provides me that. It is my combat rosary.

I brought the rosary home and my daughter has it now.

I also carry a piece of paper in my wallet, which I still have and carry.

Hank leaves the room to retrieve his wallet.

Every morning I take this out and read it. It’s been with me all these years. It reminds me that whatever happens, he’ll see me through.

God does not promise skies always blue … but …

he does promise to see us through.

Special Forces

I’m assigned to B Battery out at LZ Sherry and I figure this is going to be my permanent assignment. I fly there from Phan Thiet where Captain Gilliam greets me. I dump my gear in a hooch, and then the XO introduces me around the battery. The place is busy, very hot, dusty, miserable, and nobody’s particularly interested in meeting a green first lieutenant. I go back to unpack my gear when they tell me not so fast. You’re going back to Phan Thiet to deploy with a Special Forces unit. And better yourself a rucksack because you’ll be living in the field. Beyond that nobody told me what I was supposed to be doing.

These SF guys are strac, everything in order, know their mission to a T. They do not seem to need me and I feel like dead weight. I fire a couple artillery missions with them, but go out mostly on pacification operations to the villages. I don’t think I’m learning a lot, but I am just by watching and hanging around these guys. That experience proves irreplaceable in terms of how I will later function in crisis situations in real combat.

I go to LZ Judy for about a week (firebase west of Sherry) as Assistant XO (executive officer) and Fire Direction Officer.

Then I convoy in APCs (armored personnel carriers) loaded with ammo to LZ Sandy (northeast of Sherry.) They’ve got the big guns, the 8” and 175 mm howitzers. I am put in charge of a single 105 mm howitzer on loan from Sherry to shoot illumination at night. I think, Okay, at least this is getting me closer to home, to my 105s that I know.

It begins to dawn on me I am also learning a little about the 8” and the 175 mm. I have the opportunity to learn all of the resources that are available to me when I am out in the field. The Army did not plan it that way, but that is how it is working out. When I start calling in fire the folks at Sandy are gonna know who Lt. Parker is, and I will also have confidence in them.

Out With the ARVNs

The missions I fired with the Special Forces impressed a major enough that he now wants me back. He sends me up to Song Mao with the 23rd ARVN division.

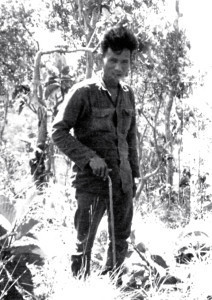

Lt. Parker Near Song Mao

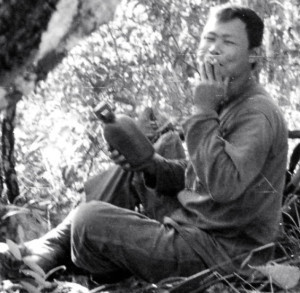

When I get there I am shocked when I see my FO is one of my classmates: Rich DeSoto. This proves to be very fortuitous for me because there is not a better map reader than Rich. We are in dense triple canopy jungle, sometimes the sun cannot penetrate, and Rich always knows where he is. I watch how he does it and he teaches me. Whenever we take a break and whenever we stop, Rich has his compass and his map and he’s figuring, where am I? In that type of environment you don’t have the reference points we had in training. You can’t see a nearby mountain. We are maneuvering with battalion size elements (about 500 – 600 soldiers). When you have three companies clover-leafing you got to know where they are if you’re going to call in artillery. Because if you don’t, you’re going to hit them. Being an FO is 90% map reading.

On a maneuver with Rich the ARVNs have these chieu hoi, POWs and deserters who are now working for us. They wear the crappiest uniforms the ARVNs can give them They carry equipment, make fires, and cook for the troops. On one of our stops the chieu hoi are off in their own area. A unit of VC comes through and sees our chieu hoi and think they are ARVN deserters because of their lousy uniforms. So the VC sit down to have supper with them. Shortly into the meal they realize, oh my god, these are actually ARVNs, they are not deserters. Then the gunfire breaks out and we hear it and join in the action. It’s like keystone cops with people screaming and diving everywhere. In those close quarters, with the foliage and the density of the undergrowth, somehow nobody gets hurt.

Chieu Hoi

Years later I am in DC with Rich and another vet friend. We’re having dinner and drinks when Rich goes into the story about when he was out with the ARVNs. He says that all of a sudden he hears loud voices in Vietnamese arguing back and forth and he doesn’t know what’s going on but knows somebody’s not happy. Next thing, he says, there’s gunfire.

I break into his story and say, “Yea, we were duckin’ and takin’ cover, jeez there’s AK47 and M16 fire going back and forth.”

He says, “You weren’t there, you don’t know anything about that.”

I say, “Rich, I was there with you. I took your picture!”

“You were not.”

So I get my picture and show him doing his map reading in the jungle.

He says, “I remember that now. You were there.”

So he writes a book, Never a Hero, puts this escapade in, and puts the picture on the back cover.

Lt. DeSoto Studying His Map

Trung Úi Boom-Boom

I go out on another operation, not with Rich this time, and again I’m with a battalion size force. We load up in Chinook helicopters and away we go. I’ve got my map and compass and I know where we’re going. I have it already plotted and I have the radio frequencies for calling in fire. Everything’s great.

We’re in the air awhile and I know enough of where we are going to realize that we’re in the air too long. I get real uncomfortable. I say to the infantry officer on my chopper, “This cannot be where we’re going, we been in the air too long.”

We land and I can’t believe it. We’re in a beautiful, lush green valley. I bet there had not been people in that valley for hundreds of years. Beautiful. The companies form up and start to cloverleaf in the cardinal directions on search-and-destroy type missions. I’m the FO so I stay at the command post with the battalion officers.

The day before I had some Vietnamese food and it really didn’t settle well with me. Because of that I have a really bad case of the scoots. The old belly gurgles and I know I’m going to have a bout, so I charge out into the woods and find a relatively private spot. I drop my jungle fatigues and am in such a hurry not to ruin my pants that I put my M16 up against a tree. The diarrhea is painful and I break out into a sweat, but I don’t mess my pants and I’m feeling good about that.

I hear something and I look up and I see two North Vietnamese coming down the trail. And then it dawns on me this is a well traveled trail. These guys are smoking and laughing and chatting. They got their AK47s. Then I realize, oh my goodness I don’t have my rifle. It’s against the tree. As they proceed down the trail I think they may not see me but they’re definitely going to smell me. Sad to say, but that’s absolutely the case. It isn’t going to be that much longer and I have to decide what I am going to do. When they are directly in front of me I jump up and yell and at the same time grab my rifle and start firing, my pants still around my ankles. The funny part is they scream back and run up the trail as I’m shooting at them, probably spooked by a crazy man with no pants.

I immediately pull my pants up, fasten my belt, and I get back to the battalion CP. I say we need to get the hell out of here because we are not in the right area.

The Vietnamese battalion commander says, “Trung úi, pháo binh.”

I know trung úi means lieutenant, but I do not know what pháo binh means. I take a guess and say, “Boom-boom?” which is the closest sound I could make to suggest a howitzer firing. I don’t realize what boom-boom really means. It does not mean artillery.

He says, “Pháo binh.”

I come again with, “Boom-boom? Boom-boom?”

“Pháo binh! Pháo binh!”

When I figure out we both mean the same thing I call in a smoke round on where we’re supposed to be. Not only do I not see the smoke, I do not hear the report of the howitzer. Immediately I call for two more rounds of smoke. I neither see it, nor do I hear it. I say, “We need to get helicopters out of here, because we’re in a well traveled area by the NVA and don’t have any artillery support.” The ARVN battalion commander sets up a perimeter, calls the infantry back in and orders helicopters.

By the time the Chinooks land to pick us up the NVA have massed and are coming at us. We are just about loaded and as the ramps are coming up on the back of the Chinooks the NVA are trying to get on with us. We’re pushing them out and throwing them off as fast as they try to get on. It’s mayhem, a real cluster. Amazingly there’s no shooting, and at the end of it all nobody gets hurt.

There is a lot for me to think about on the way back. The two NVA coming down the trail were obviously raw recruits in spanking new uniforms and shiny new AK47s. A scream and a couple M16 bursts from a half-naked soldier shooed them away. Had we hit a seasoned NVA element, they would have brought us down with rockets, B40 Bangalores. We’d be gone. We were lucky we were battalion sized. With that many men maybe we had them outnumbered. Still why didn’t anyone fire his weapon when they came at us, including me? I conclude that basically soldiers do not want to die.

I also figure out how the helicopter pilots misread their maps. In that part of the mountains there are multiple parallel valleys and they just went down the wrong valley. That’s another lesson. Pilots don’t always know where they’re going. As the FO I should have known at all times. And when you touch the ground – another lesson from DeSoto – you always fire a marking smoke round to verify you’re where you’re supposed to be. I probably would have done that, but nature called and I had to go into the woods first.

In the ARVN forces there are tiers of soldiers. I am with a higher tier. These are not regional forces, or popular forces. These are trained soldiers, guys who want to be in the Army. They are good soldiers. Typically the officers speak pretty good English, and all have a good sense of humor. After that operation they give me the nickname Trung Úi Boom-Boom. I picture the battalion commander screaming in Vietnamese for artillery and me yelling back, “Sex? Sex?”

Alone on the Mountain

After we bring the battalion back from Green Valley I am out with another ARVN battalion whose commander does not want any contact. It’s what I call a search-and-avoid mission. We go out on patrol, do everything we can to stay away from the enemy, and at the end of the day go to the highest point we can find. On this night the highest point is the top of a mountain.

I had a nylon hammock, because the ARVNs slept in hammocks. I could not convince them the safest way to sleep in a hammock is to dig a hole, tie the hammock to two trees and let your body weight take you beneath ground level. The ARVNs lost a lot of men because of that. You get into a fire fight – it’s either Charlie or NVA that comes on you first – and they’d be sleeping above the ground and would take high casualties because of that. Instead the Vietnamese camp in stream beds, which is their way of getting below ground level.

During the night a typhoon hits. The rains are torrential, the wind is howling, and it’s miserably cold, jeez it’s cold. I lash myself to a tree with my hammock to keep from getting blown or washed off the mountain. I wrap the hammock around me and the tree. I’m sitting upright at the base of the tree. That way I’m secure while everyone else is sliding down the mountain, equipment and all. When the sun comes up I’m the only one left on the top of the mountain.

The entire battalion had slid down the mountain, all four sides of it. It takes us three days to reform, and then we go back to Song Mao to dry out. I think two to three ARVNs drowned.

Feet Flavored Rice

I eat at least four to five bowls of rice, while the average Vietnamese soldier has one. My strategy is if they cook it too long they burn the bottom. The Vietnamese will not eat burned rice but I will, I like it. Still they think I eat too much as a matter of cost. I have to start getting and carrying my own rice, which I pick up in Song Mao and carry in two boot socks around my neck.