Ed Gaydos's Blog, page 11

April 1, 2015

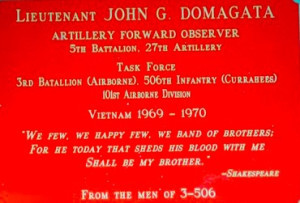

Bud Domagata – Forward Observer – Part Five

From the Frying Pan Into The Air

When I came to Vietnam I was told I would be a forward observer for about four months, then four months work in a battery, and then four months working in liaison. After nine months of being an FO, it was obvious that none of this was going to happen. If I stayed in the field as an FO I was sure my number was going to come up. So I extended my tour in Vietnam to become an air observer, still calling in artillery fire but now from the air.

I had experience with air observers bailing me out several times. I’m in the jungle getting shot at, we’re in too thick a jungle and I can’t see, I know the direction we were getting shot at from, but I didn’t know from how far, and this AO all of a sudden brings clarity to my life and saves our bacon. And I knew that every night he went home and slept in a bed, had someone fix him a meal, had a hot shower at some airstrip. I did not ever want to sleep in the jungle again. I did not want to have to pull off blood suckers again, I did not want to have to be low on ammo, low on food. I didn’t want to get shot at on the ground any more. If you want to shoot at me in the air, fine, I’ll take that, but I want a bed at night, a meal. I don’t care how bad the mess hall fixes the meal, it’s going to be better than any meal I ever had in my canteen cup. The AO had a little excitement in his day, and then he went home. He went to a bed. And he still got respect. I did not want to go back to a motor pool, or have to inventory canteens, or some pain in the butt thing like that.

I was an air observer for the next ten months, from October 1969 to August 1970 when I went home. I flew almost every day supporting fire missions when somebody on the ground was in trouble. When I wasn’t doing that I was registering the guns for the batteries around Phan Thiet, Sherry, Sandy and Betty, for Charlie battery up near Dalat, and for guns out on mobile operations. I was attached to Task Force South (covering the southern end of the Central Highlands of Vietnam) and therefore worked with all of its infantry, cavalry and artillery units in that area.

Registering artillery pieces was similar to adjusting a rifle sight. It involved adjusting rounds to hit a known coordinate (similar to a target bull’s eye) in order to adjust the settings on the howitzer for maximum accuracy. Howitzers had to be registered whenever they were moved, and periodically when they remained in place or received a new lot of ammo. It was a never ending and important task.

Bud’s view from the back seat of his Seahorse aircraft

Walter “Hoot” Gibson

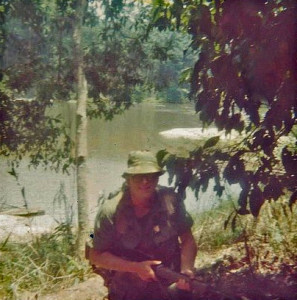

It’s October and I am a brand new air observer supporting a fire mission for the 3/506 infantry, the guys I was with for five months and just left. I’m in the air and my guys are under attack. Okay, let’s take a leap back three months to when I was their forward observer and accepted as a guy who knows what he’s doing. We lose a platoon leader. I don’t recall how we lost him, but now we are a platoon leader short. The commanding officer says to me, “Bud, I need you to run the platoon until we get a platoon leader.” The platoon sergeant has been there a long time and the squad leaders are good, so no big deal.

When the new platoon leader comes in he is he is a second lieutenant just out of cavalry ROTC, not infantry and not airborne. The CO says, “Bud, you stay with him for about a week and make sure he doesn’t get into trouble. Between you, me and the platoon sergeant we’ll get him seasoned. He’ll do well.” He is from Georgia, and he has this cowboy sort of southern accent, a little bit of a slow drawl, an Atlanta drawl. His name is Walter Gibson, but we call him Hoot Gibson.

I connect with Hoot more than anybody, because I have to be with him, and I have to make sure he knows things, that he knows how to take care of the guys. It’s all about the guys. I am not officially responsible, but I could probably run a platoon as good as most because I have been in the field eight months by now. The CO was right, Hoot is sharp and does well and I feel good about him. I recall that he could read a map, or at least he led me to believe that he could.

Now flash forward. I am in the air supporting the operation where Hoot’s company is under attack. He charges the ambush and is killed and his squad leader is shot up read bad. I stay flying above them while a jungle penetrator helicopter pulls up the wounded squad leader. Out of all the guys I was with in Vietnam, of all the 3/506 airborne guys, he is the only name I remember. I remember Hoot Gibson.

I learned later that Hoot, his platoon sergeant and his squad leader did not want to go charging into that ambush. But his hard charging battalion commander, flying safely in his chopper two thousand feet in the air, pushed Gibson into the charge.

So now go 30 years later. I am at the 3/506 reunion where they gave me the Screaming Eagle statue and plaque. Do you know who is there? Hoot Gibson’s dad. Oh my gosh. The dad’s old as dirt, he is in his 80′s. It is a great thing. Also at this reunion is Hoot’s squad leader who got wounded in that same attack. I remember him. I do not remember his name but he is there with his wife, and Hoot’s dad is there. I am awestruck.

Walter “Hoot” Gibson

Died October 28, 1969 three months into his tour

Picture courtesy Mike Rogers

LZ Sherry

I never set foot on Sherry, but what I remember most are the guys on the radio, guys like yourself and the fire direction officers. I had an affinity with the fire direction officers because most of them had been forward observers, and that was their motivation to get rounds out fast. That was the sequence. When you are a forward observer you know it’s important to get rounds out fast. Then when you get to be a fire direction officer and you make sure those rounds get out fast. You’re the jockey on this horse. We would BS on the radio about the units and where you’re at, or we would talk about R&R’s, here and there, where did you go and what did you buy, who got the biggest camera and the best stereo or the best reel-to-reel TEAC. That was my radio conversation with these guys. To avoid the official radio freak (frequency) we would go up or down a couple of clicks on the dial to have these non-official gab sessions. I remember “meet you up a nickel” meant we’d tune five megahertz up on the freak dial.

I remember a couple of times dropping a red mailbag down to Sherry guys. The traditional way was you would send your convoy in. But sometimes flying over Sherry we’d put the flaps down, and if it was a windy day and we were flying into the wind we could be flying 30 miles an hour ground speed, almost be like a helicopter, and drop the red bag out. The mailbags were always red.

Looking Back

The things I remember most. Coming home. (Laughs) Being done. Just surviving so many crazy times. Friendly fire by another American unit. I went through that without anybody getting killed.

I just remember the intensity of fear of making a mistake. If I read this map wrong, if I transpose these numbers. We had this thing called the SOI (Signal Operating Instructions: codes for radio communications) that little white book with encrypted numbers that was always changing. How many times can I do this and call it in and make sure there is no mistake? The fear of calling in a round on the wrong place. I talked to the gun bunnies and to some of the fire direction guys, and I was never really worried about the guns. I was afraid of myself, of making a mistake. If you’re getting attacked you’ve got to be fast. These guys are pinned down, and BOOM, BOOM mortars coming in. It was like, “Oh man, do it fast, do it fast.” The fear of making a mistake was there every minute.

Bud called in artillery fire from the field and from the air for an unrelieved 19 months during a period of heavy conflict. Not once did he call in bad data, not once did he misread a map, and never did he fail to protect his men. He doesn’t remember most of it, but the men he saved will never forget.

March 25, 2015

Bud Domagata – Forward Observer – Part Four

Starting Over

After four months with the ARVNs (South Vietnamese Forces) I got assigned as a forward observer to the 3/506 Infantry of the 101st Airborne. Because I am not infantry and I am not airborne. I’m an outsider again and I gotta start from scratch. Also, I still look like I’m 17.

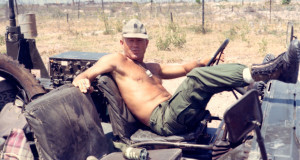

Bud early in his time with the 3/506

I go out on operations, I don’t screw up and I get to know the team I’m working with. Then a different company rotates to the field, which means I start from scratch – again. Those initial operations with the 101st were bad, I mean I was an outcast.

To make it worse there was a shortage of forward observers. When the infantry company would rotate to a firebase or the rear for a stand down, I would rotate to another company headed for the field. I had more field time than anybody in the infantry. That’s one reason I burned through radio operators. They’d see all these guys going in and we never got to go in.

It took a month before word got around that hey this guy is actually good and does things right, fast, and knows what he’s doing. Early on I got to call in naval gunfire from the battleship New Jersey. Phan Thiet was the New Jersey’s final run before she left for home. (The battleship New Jersey departed the Phan Thiet area for Japan on April 1, 1969.) That went a long way to showing what I could do. Remember I’m not a green forward observer. I’ve been out with ARVN troops for four months calling in long range artillery, because we were hardly ever near a 105 battery.

Now I’m all over the place, in the Lee Hong Fong forest, up in the mountain jungles, and down around Titty Mountain – firing out of Sherry, Sandy or a platoon of guns on a hip shoot. We’d even go way up north along the coast around Song Mau with a couple guns from Charlie Battery. I was on and off in the field with the 3/506 all the way through September, five months straight.

Search and Garden

Now one war story, the only one I remember. We’re out in the mountains following a band of Viet Cong through thick jungle, and every once in awhile boom there’s a big open area the size of four football fields plowed in neat furrows growing corn and all kinds of squash. We’re on our third day following the VC and this is our third garden. Instead of “search and destroy” we started calling this operation “search and garden.” Well this garden has watermelon and it’s hot and the watermelons are cold and the guys are carrying them on their shoulders. It’s crazy.

It turns into an ambush. Our point guys are under fire from the jungle and you can’t see where it’s coming from. I am a little behind them with the platoon leader and company commander. We’re in the worst possible situation to bring in artillery because we’re in the mountains, meaning you’ve got altitude to worry about, and we’re on the target line (between the target and the howitzers and therefore exposed to range dispersion). I call in a first round smoke and it’s pretty close. I adjust the second smoke round away from us and it pops right behind the enemy, which is perfect. The guys are yelling “It’s right where we want it. It’s right behind them. We’ve got them pinned down. Yaa.” I call for all the guns to fire high explosive on that setting – BATTERY REPEAT HE. Instead of landing on the VC the rounds come down right on top of us. I see one of our guys get blown twenty feet in the air. I’m seeing this guy and thinking, Holy shit. Right away I call a CHECK FIRE.

We were lucky. When the VC saw artillery coming in they took off. The round that blew our guy in the air hit soft, plowed soil from the garden and buried itself before detonating. It gave him a ride but nothing serious. And nobody took shrapnel from the other rounds. He was the only one hurt and medevac’d out. If we were in a treed area, or on regular hard ground, there would have been a lot of shrapnel injury, but because we were in this this big freaking garden area, the round penetrated into the ground before it went off.

Then of course the investigation begins, interviews like crazy. We had a colonel who was the commanding officer of Task Force South come flying in, another colonel from Phan Rang and all kinds of other people. With them was the artillery commander of the battery that fired the rounds (Delta Battery of the 2/320th Artillery at LZ Betty attached to the 101st). They are interviewing everyone right on the spot. Everyone is validating that what I did, and the way I did it, verifying that I did not do anything wrong. The first round was here, the second round was there, and I called high explosive in on the back side of the second smoke round. I just said REPEAT HE, right on top of the last smoke around, no adjustment.

We spend the night and the morning, and another group comes to do more interviews. Everybody who is important – the commanding officer, the company commander, my radio operator and the commanding officer’s radio guy – know that I did this right. But the troops only know rounds landed on top of them and blew one of their guys up. I’m the artillery guy, and I’m not airborne. When I see our injured guy with his neck brace on I cannot look him in the eye. Nobody would look me in the eye either, and for awhile I think they were going to turn on me.

The mission carries on and I don’t hear anything more about it. But do you ask what happened or do you let it go? What do you do? I’m 21 years old; I let it go. Until I got home and then it comes back, and comes back, and won’t leave me alone. It took me twenty years to resolve. I went to the National Archives and got the after-action reports for the artillery and 3/506. I found out that a batch of smoke rounds was bad and was shooting long. This was not the first incident, it happened in another place before me. As a result they pulled all those rounds. But who’s gonna tell the young second lieutenant who’s out as a forward observer that he might want to know so he can sleep better.

They should have pulled those smoke round after the first incident. The second time with me should never have happened. You cannot believe the pucker factor when those big 105 rounds are landing all around you. Mortars are one thing, and I have survived some mortar attacks and those are frightening enough, but this was (laughs) crazy. Rule number one is don’t be on the gun target line. But we did not have any choice, that’s where we were at. There was no secondary battery to call. It was like, We need rounds now, let’s get them in. They did get us the rounds quick, first round smoke, second round smoke, then BANG. I can sti

ll hear those rounds coming in over our heads and down on us. That’s something you never forget.

I lost my radio guy because of this. He said, “I cannot be out here anymore.” The artillery radio operator was an artillery guy, and he had to be a volunteer. He said, “I ain’t volunteering anymore.” I went through a lot of radio operators because they’d get freaked out.

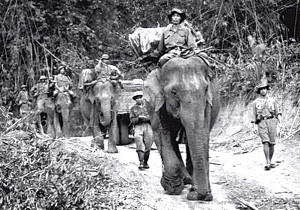

Viet Cong Elephants

Another crazy story. I can remember crazy things, but not warrior stuff, except for those bad smoke rounds. We are in the highest mountains and the thickest jungle you can imagine trying to catch up with a unit of Viet Cong. Typically when you are following a trail you have your guys out to the left and the right, and maybe some guys in the middle. But this trail was along a cliff edge two feet wide, straight up a couple hundred feet and straight down 1000 feet. All of a sudden we see these things that look like cannonballs on the trail. What in the hell is this? It was nothing you would ever guess – elephant shit. So elephants had been walking down this narrow trail that I am scared to walk on: you can’t go one way because it’s a wall and the other way is a sheer cliff to your death. Viet Cong elephants loaded with stuff had just gone down this trail, like Hannibal going through the Alps, and you think, How on earth? No, we never caught up with them. They were fast, those Viet Cong elephants.

VC Elephant Convoy

March 18, 2015

Bud Domagata – Forward Observer – Part Three

Doings In Dalat

Dalat was a French colonial city that looked like it had been transferred from the French Alps to Vietnam. I mean it was gorgeous with paved roads, French buildings, Jaguars driving around, and even a few convertibles. It had three universities; their equivalent to West Point was one of them. ARVNs (South Vietnamese Regulars) loved this city; it was their Mecca. And it was a safe area. They really did not want Americans in there at all. There were some American units around it, but the only guys that could legitimately get in there were the MACV guys assigned to the ARVN units as advisors.

MACV – Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – commanded all military units in Vietnam. Those connected to it enjoyed special travel and access privileges, including ones they granted to themselves.

My ARVN regiment would rotate a company in for three or four days to pull security around the city. Squads and platoons would spread out around the city to keep out the enemy, who were never going to attack because they loved this city too. The Viet Cong took R&R in Dalat right along side the ARVNs.

I don’t know how this happened but I was assigned to the unit protecting Dalat. Wait till you hear this. By now I am really close to the ARVNs, we are buddies, we tell stories about our sisters and the girls we date and things like that. The CO (commanding officer) looks at me and says, “We have Dalat.” Then he winks a couple times. We get right on the edge of the city on the road, and the CO calls in all the platoon leaders and says, “Okay. We will meet back here in three days,” and he releases the men. Then he gets me, my radio operator, one platoon leader, and maybe a senior sergeant – and we all go into town and we check into a hotel.

Maybe three miles away on a hill Charlie battery has a permanent firebase (one of the artillery batteries organic to the 5th Battalion). Its job is to keep the whole city covered for artillery support. Charlie battery and the ARVN headquarters think we’re set up in defensive positions around the city. Instead we’re in town staying in a hotel and having a grand time.

We go up on the roof of the hotel where there is a bar with a balcony, and there’s Saigon girls serving tea. We set up our radios, and we call into Charlie battery with a bunch of fake nighttime defensive positions around the city. Of course there’s nobody at the coordinates we’ve called in. Then we give them a bunch of H&I (harassment and interdiction) targets to fire on. We say at 10 o’clock shoot these defensive H&I rounds, at 11 o’clock fire these H&I rounds, at noon fire these, and midnight these – then no more after that.

Then we tell them we are not going to move these fictitious defensive positions during the night, and therefore won’t be calling in new locations. With the ARVNs we’d usually set up nighttime positions, call in locations, and then we’d move. The Viet Cong had watchers to find out where we were set up, so we would have a 10:00 move. Moving into position we would not worry about making noise, but after it got dark we’d move as stealth and quietly as known to mankind.

We’d move maybe only 20 or 25 yards, but we were not exactly where we had set up. So if the Viet Cong attacked there’s nobody there. We tell Charlie battery we are not going to move during the night because it’s so quiet, we’ll call you in the morning, you can forget about us. And they say, “Yeah, we do this all the time.” So for three days we are checked into the hotel, we are eating like kings, we’re going to restaurants, and from the rooftop of the hotel we’re drinking tea from Saigon girls and shooting fake targets to make it look like we’re doing something.

It gets better. Dalat has a French jazz scene, berets and all. It wasn’t the Beach boys or the England sound. Jazz was a big part of the music in Vietnam from the French influence. The ARVN commanding officer says, “You’re going to love this.” He takes me and my radio operator down by one of the universities, we go down some steps literally underground into a little place with jazz band playing. There are guys with goatees and berets, all of them Vietnamese. He says, “No matter what you see, just relax and enjoy yourself.” It was a dark, smoke filled room with candles on the tables and a very mellow jazz band.

We put our M-16s up against the wall by us, and down the wall we see AK-47s. I don’t know who the AK-47s belong to because the VC could be in jeans dressed like college students. All I know is I did not want to make eye contact with any freaking body. I don’t know if we had coffee or something to drink, I was never a big drinker, but we had an evening just listening to the coolest jazz you can ever imagine with VC somewhere in the room. This I think is cool, so unreal I’m shaking my head and my radio guy is shaking his head. We say to each other, “We cannot tell anybody about this, because we’re not really here.”

The Beast

One of my most vivid memories when I deployed with the ARVNs did not involve them at all.

I was officially assigned to Alpha battery of the 5/27 even though I hardly ever saw those suckers. One time I showed up at Alpha when it was on a mobile operation down south near Titty Mountain. Maybe I went there to pick up my mail and briefly get out of the field, like I usually did. The guns were towed to this location, as opposed to lifted by helicopter, so there were deuce-and-a-half trucks, jeeps, ammo trucks and all that.

And they had a Quad-50 with them.

Quad-50 mounted on a deuce and a half (2 ½ ton truck)

The Quad-50 was four 50 caliber machine guns arrayed on a single rack that allowed all four guns to fire at once. The weapon was aimed and fired by way of electric motors fed from two batteries. The motto of Quad-50 units was “First To Fire” because of their almost instantaneous response to enemy attacks. At artillery firebases they were mounted on a truck bed and placed on the perimeter to thwart ground attacks.

I wasn’t close to anybody at Alpha, but for some reason on this trip I buddied up with the Quad-50 guys. They said, “Do you want to fire it?” It surprised me that they would offer, but sure. First they wanted me to get used to the controls, aiming the thing up and down and all around without firing it. So I did and thought, This is fun. Then they said, “Okay, now we are going to load it up.”

We were located at a former French site with hard bunkers that the French had built and were still used as firing positions. So I didn’t kill anybody they told me exactly where to aim. As soon as I pulled the trigger the thing went wild on me, jerking straight up and out and I am shooting live rounds all over the place. The tracers are going everywhere, 50 calibers are all over the sky, and everybody is screaming and running. Finally somebody just turned it off. I think I crapped my pants. I was more scared than during a fire fight with the Viet Cong. I heard after me they never let anybody else touch it.

March 11, 2015

Bud Domagata – Forward Observer – Part Two

Vietnam #1

I went to college for a year and a half, and I hated it, mostly because I was not mature enough to be in college. “I’m out of here.” Well you know what is coming. You and me and everybody else were facing the draft.

I had an uncle who was a Command Sergeant Major E-9, and a Korean War hero with all the medals. He and my mom said, “You go to Vietnam, you are going to get killed.” And I had just had one of my best buddies who went in earlier got killed and I was his pallbearer.

My uncle said, “What do you want to do with yourself? Sign up for something, get schooling.” I said I wanted to be in the transportation business someday. When somebody moves stuff, I’ll be involved. That is what my degree was going to be in if I finished college.

He and my mom found this army transportation school that was really phenomenal, and when my draft number came up I signed up for the extra year and got this class.

In basic we took a lot of tests and they said to three of us we could go to OCS (Officer Candidate School). All of us said, cool, let’s do it. We’re 19 years old and stupid. They said what do you want to be? I said I wanted transportation. But you also had to pick three and one had to be a combat arms for OCS, and I picked artillery. Infantry would be nuts, in a tank I’d be a big target, and I can’t swing a hammer so Combat Engineer was out. Artillery was the only thing left. But I never heard from them and they sent me to the transportation AIT instead. (Advanced Individual Training)

The transportation school was really cool, it was my dream job. When I graduated I asked, now what about Officer Candidate School? And they said, not now, you’re going to Vietnam, something I did not want to do. I said to my uncle, “Old man, I’m getting killed.”

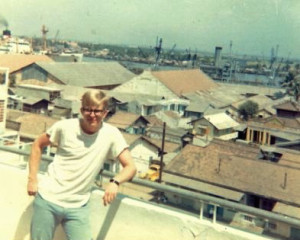

Well low and behold I was stationed in downtown Saigon and living in a hotel. I took a cab to work most days on the Saigon docks, a huge international harbor. I worked with the civilian ships, cargo ships that came into Vietnam every day. I controlled a lot of cargo. I had a job that was just phenomenal. That’s the good news.

The bad news was when the TET offensive of 1968 hit in late January there was no defense of the city. I got caught down in the harbor area with no weapon. It was locked up in some armory in the basement of the hotel.

The only people defending the city were the MPs, and they were worried about police stations, radio stations, the embassy and things like that. There were two sets of docks, the military docks and the civilian docks. All the military support went to the military docks which were across the canal and down the way. I was about six blocks from the embassy, and nobody cared that there were half a dozen of us down at the docks with snipers firing at us and pinning us down. (North Vietnamese Army regulars were able to breach the outer walls of the U.S. embassy.) I hid under a truck for two days.

The MPs finally rescued us, got us our weapons and put us on the roof of our hotel with orders to guard the hotel. That went on for two weeks and was my war experience as an enlisted guy.

February, 1968 following TET offensive -

Bud on the roof of his Saigon hotel overlooking Saigon River and docks

Then about five months into that tour I’m working the night shift, and during the afternoon while I was asleep, someone tapped me on the shoulder and said, “The CO wants to see you, you’ve got orders to go home.”

I went to the CO’s office and he said, “You’ve got orders for OCS. You can either accept or decline them, but you’ve got to be out of here in 24 hours. You have to decide right now.” At that point I had survived TET, but taxis were still getting blown up, restaurants were still getting blown up, stuff was happening all the time that was kind of frightening. I figured, here’s a chance to go home.

I had no idea what being an officer meant, except that every officer I knew stayed in a better hotel than I did. I figured I’d come back a transportation officer and stay in a better hotel. It was not until my second week of OCS at Ft. Sill that I learned we were going to be forward observers. Remember I did not go to an artillery AIT. I went from being a clerk in Saigon straight into OCS. I did not know one end of a howitzer from another. I didn’t know a 105 from an 8 inch from a 175. They may have been Polish words for all they meant to me.

How To Sneak Up On A Chicken

When I graduated from OCS they gave me three sets of orders:

1. You are a second lieutenant

2. You’re going to Vietnam again, and

3. Oh by the way, you’re first going to school in Panama to be a jungle expert.

So I went through some crazy, nasty school down in Panama to learn how to make the jungle my friend. This was a very famous jungle school but a weird place. The course was a little over two weeks. They taught me how to eat rat meat, bugs and snakes, and how to sneak up on a chicken. If you grew up rural you know that is not an easy thing to do. You move like a snake, slowly slithering along the ground on your stomach. It was the neatest thing, and we practiced on real chickens.

Vietnam #2

From Panama I went straight to Vietnam in early January 1969, attended forward observer school up in An Khe, and then got assigned to Alpha Battery, 5/27 Artillery as an FO. I did not see much of Alpha Battery because I was always out with the infantry. I went in to get my mail and left as soon as I could. Every time I passed through Alpha something was screwed up. The rumor was they tried to kill their First Sergeant. During a night fire mission he wouldn’t come out of his bunker so someone drove an ammo truck into it and caved it in. It did not kill him, just broke his leg good. Another time the battery commander got relieved, I don’t know for what. The place was a nightmare.

My first deployment was with the 53rd ARVN Regiment (South Vietnamese regulars) around Di Linh up in the Highlands (a fifty mile chopper ride straight north from Phan Thiet). But first I stop at our Charlie Battery, which is at a permanent firebase outside Dalat (another forty mile ride northeast of Di Linh). Dalat is a beautiful old French city. Our battalion forward is there, in a two story colonial building, and also has a basketball court. So I’m there playing basketball and all of a sudden I hear WUMP WUMP – and I look around and I am the only one on the basketball court. I’m standing there by myself with a basketball in my hand. I did not know those were incoming mortars until guys started yelling at me. I could have been killed my first week in country.

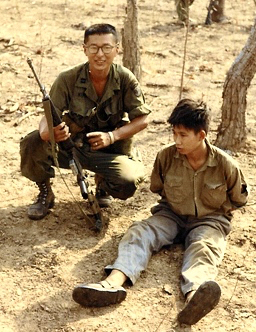

I was with the 53rd ARVNs for four months. It took a while to adapt to being one of only two guys – me and my radio operator – who’s American with all these Vietnamese guys. You start by being afraid to go to sleep, because you don’t know these guys, are they going to abandon you? Or maybe they’re Viet Cong in disguise? Are you going to get killed by them? It goes from that to you get in a contact or two and you do some brilliant artillery adjustment and all of the sudden it’s like you walk on water.

I could not speak the language. But my first tour had been working with the Vietnamese civilians. So I picked up some there and now I’m quickly learning more. Often I knew what they were saying, but they didn’t know I knew. There usually was a person who spoke enough English to get through what we had to do. It went from, Who is this white man? to being an integral part of the team, and I’m loving it.

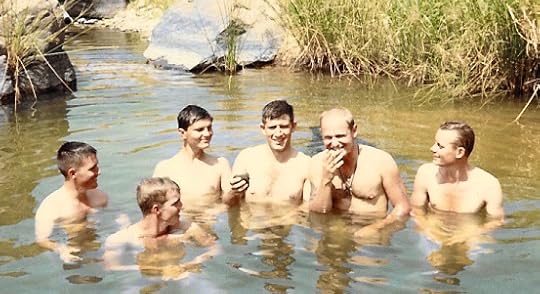

Out with the 53rd ARVN forces

All of a sudden they offer me a batman, like an English type servant who would carry my rucksack, fix my meals and clean my boots. So now I’m a good guy and they’re watching over me. I did not accept the batman as a servant, however he acted as my personal bodyguard.

It wasn’t easy with the ARVNs. I would say that 30% of the time we were out of 105 howitzer range. When you’re under attack a 105 howitzer could get a first round out to you almost instantly. The fastest artillery round we could get from the big 175 mm or 8 inch howitzers took five, six, seven or even ten minutes. And then adjusting fire was a big deal, on top of that the 175 did not shoot straight. Being out of range of the 105′s was crazy, but just part of the ARVN deal.

Now the American units always brought a couple of 105s with them if they were out of range of one of the permanent bases at Dalat, or LZ Sherry or the howitzers at the end of LZ Betty. They would take two guns out and bring them along and drop them someplace close.

The ARVNs were second-class citizens as far as the Americans were concerned. But my ARVNs were phenomenal. In many cases they were better warriors than the 101st Infantry that I served with later in my tour. I would go to battle with my ARVNs in a minute. My guys did stuff right, they were stealth, they were fearless. And we were one. However, not for one minute am I besmirching my 101st guys, don’t misunderstand.

March 4, 2015

Bud Domagata – Forward Observer – Part One

The Whole Story

Bud saw three successive TET offensives: 1968, 69 and 70. On his first tour as an enlisted soldier, the infamous 68 TET had him pinned down without a weapon for two days under a truck on the docks of Saigon. This tour lasted just five months. Bud’s second tour as an officer lasted over a year and a half. He marched as a forward observer calling in artillery fire with the 53rd South Vietnamese Army Regiment for four months, and then five months with the 3/506 Airborne Infantry. Nine months was a long time for an officer to be in the field as a forward observer. Ordinarily he would have been pulled out of the field back to a job in a battery or the rear. Seeing no end in sight to his field assignment and tired of sleeping in the jungle with rats, blood sucking creatures and marauding Viet Cong, Bud extended his tour in Vietnam in order rotate to become an air observer. He still called in artillery fire for ground forces, but now from a little two-seat airplane. Of all places to be in Vietnam, in the air was one of the worst, but Bud’s feeling was, “They can shoot at me in the air now instead of on the ground, but at least I’ll have a clean bed to sleep in at night.”

Lt. Domagata beside his Cessna O-1 Birddog

Called a Seahorse for its radio handle

Bud faced multiple dangers in Vietnam, yet he remembers only a handful of incidents. He relies instead on the testimony of others whom he does not remember either. It’s not that Bud has a poor memory. He retains an iron grasp of places, equipment, dates, military units and a host of logistical detail. It’s the fighting he’s forgotten.

I don’t remember any battle. I do not remember a specific time shooting at anybody. I do not remember a single bullet fired in anger. Never. None. Zero. Not one. With one exception I don’t remember calling in artillery on an enemy. The same thing while flying with the Seahorse pilots. One of the pilots contacted me and said you got to come to our reunion. So this past year I went to the Seahorse reunion. Two pilots are talking about us flying into heavy machine-gun fire and getting the plane all shot up. They were very specific about times and places. One was up at Song Mao, flying into machine gun fire. Another one was right outside of LZ Betty, another situation where we are getting fired at by multiple guns back and forth. The pilots knew exactly how, when and where. I had no recollection. They said, “You were the artillery guy in the back seat. We know what you were doing, you were calling in the artillery, and we were screaming over the radio.”

The stories Bud does remember are like nuggets catching a spark in the dark. But you can’t help wondering, what’s in the shadows that could tell us more of this soldier? There’s a hint of an answer in a story set well after Vietnam. So let’s begin at the end.

Found and Unforgotten

Hank Parker and a couple guys found me on the Internet. I start getting bombarded with, “You’ve got to go to the reunion, there’s no way you are going to miss this. (Reunion of the 3/506 Infantry) We are going to kidnap you.”

“First of all, I don’t know who you are and why are you saying this stuff to me?”

Then this guy named Hank Parker starts telling me stories about all the things that we did together, and I say, “I do not know you, Hank.”

Hank says to me, “No, we did all that stuff. And you had a dog that was always with you.”

“You are out of your mind. I never had a dog.”

So he sends me pictures of me with the dog.

Lt. Domagata with his puppy

It’s not just one picture, he sends several. Okay, he’s got pictures of me and I am believing he is a real guy and I should know him. But I don’t know him; I don’t remember him.

My wife says, “You have never been to one of these things, so go, get it out of your system.”

I go to the reunion in Reno, I fly out, and there’s this group of guys telling all these war stories. They got more booze in the hospitality room than three taverns. These guys are hammering it down, laughing, maps out, pictures, books, and I am not connecting with anybody. I look at the books, and at the pictures, and I remember the places but I have not connected with anybody.

For two days I am still not connecting with anybody, so Saturday I plan to catch a plane out of there. But they tell me, “You have been here this long, you are not going home, you are staying another day. There’s a big banquet tonight where all the ladies are dressing up and there’s going to be dancing along with the best meal you can imagine. You gotta stay, because we won’t let you leave.”

That evening right after the dinner there were some thank-you’s, awards and recognitions. They read a document about the extraordinary actions of a medic who I had met earlier in the day. He was just the humblest guy, a postal carrier, quiet guy, nice guy. They read off two pages of names, maybe 30 guys that he had saved. And for each guy that he saved there was a little story. Everybody is crying, and they call him up, and they give him an eagle and a plaque with his name engraved on it and a saying from the Band of Brothers, that Shakespeare quote, with his dates in Vietnam. I got chills.

Then they said, “We got one more.” And I saw another eagle up there. They started reading this document about a former forward observer and then called my name. My mind is racing. I am red. I am sweating. They said, “Lieutenant Bud Domagata, come up here and get this eagle.” I went up there and I said, “You know, this is the greatest honor of my life. But I do not remember all this stuff that you just said about me, and I don’t remember any of you guys.”

They were all standing up and said, “We remember you, Bud.”

I thought to myself, this sucks, because I don’t remember any of them. Not a one of them. Not one!

I take the eagle home and put it on the TV stand with the greatest pride.

Our daughter is back from college and is sitting there watching TV. She looks up and says, “Dad, that chicken is staring at me.”

Notes:

The 3/506 Airborne Infantry shoulder patch features an eagle’s head, leading to the nickname “Screaming Eagles.”

The book “Band of Brothers” and subsequent TV series were about the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

The infantry placed a high value on a good forward observer, often claiming he saved as many lives as a medic. It’s not a surprise the 3/506 honored Bud beside one of their medics.

February 25, 2015

Alex Taubinger – Forward Observer – Part Eight

B Battery

Lt. Taubinger makes only the occasional visit to LZ Sherry, even though he is formally assigned to B Battery. What few memories he has are vivid.

Of all the batteries I had fire for me, B Battery at LZ Sherry was more responsive than any of the other batteries. Farrell was the first sergeant at the time.

First Sergeant Farrell

Not On The Ceremony Agenda

I was up in a tower taking pictures of a change of command ceremony (probably early May 1969 when the new battery commander arrived who could come to be known as The Ghost),when an F-4 jet comes on a bombing mission off our perimeter. He makes multiple drops on a single target and when he comes in for another run he goes into a nosedive and never pulls out of it. I turn my camera in that direction and take a picture of the black plume of smoke that comes up when he hit. I felt sorry for the pilots, and I felt really bad that we could not go out there, because we were not geared for that kind of thing.

F-4 crash

Safe Place During a Mortar Attack

One night at Sherry they had me bunk with the battery commander, I don’t remember his name. I woke up to incoming mortar rounds and said to him, “That’s incoming.”

He said, “No, that’s out going.”

Then the whole battery woke up – the incoming siren going off, the machine guns in the towers opening up, illumination popping in the air and lighting up the battery – I got my helmet and flack vest on and started out the door. I turned around and saw him going underneath his bunk. Outside Farrell came around the corner and asked me where the captain was, and I told him, “Under his bunk.”

No Table Manners

Another incident with this chickenshit captain – I was there a of couple days – we had a monkey there at the base (Sergeant Farrell’s monkey). Susie was her name and the captain did not like her one bit. He told me how the monkey once ran up his back, sat on his shoulder, and began looking for lice in his hair. I also heard the story of how Susie went into his hooch while he was in his cot, got up on the T-bar supporting the mosquito net, and peed on him.

I was with the captain in the mess hall, both of us eating pie when Susie came and sat at the table. The captain said, “Get that monkey out of here.” At which the monkey grabbed food from the table and threw it in his face.

Welcome Back

My radio operator and I went out with the South Vietnamese and worked along the border with Cambodia for quite a while. We were both real grubby when we came back and we stopped in at Sherry. This captain told us to get haircuts, so out of spite we got buzz cuts and showed up nearly bald, which made him even madder.

Party Time

With only a couple months left in Vietnam I go to the Tactical Operations Center at Betty. At the TOC I am responsible for ammo getting out to the firebases, the helicopter resupply runs, and making sure our guys get everything they need.

Hank Parker is still at the TOC, about to go home like me. I say to him, “I hear there’s a party up at the morgue.” Four of us go up there in a jeep. I’m driving, there’s a little short pudgy master sergeant riding shotgun next to me, with Hank and another guy in the back. After I round a sharp corner the guy in the back says, “Where did Top go?” I look over and see he’s gone. I stop and right away back up and I hear someone yell, “Oww.” I had run over his shoulder. It was in the sand so he isn’t hurt too badly. The pins securing the seat were not in and when I went around a corner he had slipped right out.

We get up to the morgue and we see an older Marine lieutenant outside scratching his head. He says, “I was backing up and my jeep fell into this big hole here.” We look and see a large sinkhole with his jeep in it upside down. He is all worried about getting into trouble, so we tell him we’ll call a wrecker when we get inside.

We go inside and they tell us all the food is stored in a big refrigerator room with a sign saying HUMAN REMAINS ONLY. I walk in and see beer, steaks, chicken and lots of other food, but no bodies at the moment. I grab beers for all of us, but the guy who was in the back with Hank says he’s not about to eat anything that came out of that refrigerator. To me it looked cleaner than grocery stores you see today.

Worth More Than A Man

At the TOC I got called out for whatever they might need me for. B Battery was shooting H&I one night (random short range shelling to protect a perimeter) and two rounds landed in a village, killing an old man and a water buffalo. I had to go out to the village to investigate the incident and do a crater analysis. I had thousands of piaster with me to make reparation pay offs. But before I went to the village I went to the battery Fire Direction Control center to look at their charts and any coordinates they may have plotted. I told the battery commander not to say anything until after I got back, because it might have been a VC rocket they were claiming was U.S. artillery.

When I got to the village there were Vietnamese military and province officials there as well. The villagers were running in and out of the craters obliterating the spray, so you could not tell where the rounds came from. They handed me 105 mm fuses they claimed they had dug up from the craters.

I called the battery commander back and said my official determination was we didn’t know what it was. It could have been VC rockets. They could have given me fuses from anywhere. But the battery commander had already found the error and reported it. It was a mistake with the powder charge. Thank god he did not get relieved over the incident. The old man cost us 500 piasters and the water buffalo 1,000 (about $2 and $4 respectively in 1969).

Gentle Persuasion

I got a call to meet a convoy from Sherry at the ammo dump, saying they might have a problem picking up their ammo because of the ASR (ammunition supply rate). They were already over their allotted rounds for the month and might not be able to get their ammo.

The supply sergeant in charge of the ammo dump was a fat E-6 staff sergeant. Had to weigh 400 pounds. He was wearing a Combat Infantry Badge and I asked him how he got it. He said, “I was on guard duty at Cam Ranh Bay. A sniper shot at the base and everybody got a CIB that day.” Then he said he wasn’t going to give us our ammo. He got sarcastic that we were out there at Sherry just shooting away wasting ammo.

I put my hand on my .45 pistol and told him we’re going to get the ammo one way or another. One of the guys from Sherry, a big blonde E-5 buck sergeant in charge of the convoy (Sgt. Rock), shifted his M-16 to a very aggressive position. We got our ammo.

Sergeant Rock

A couple days later I was called to the 1st Logistics Command at Cam Ranh because they wanted to talk to me. They were going to charge me with something, and ordered me to meet with the general. I hitchhiked chopper rides up there and when I get there I see the Playboy Playmates walking around his office building, a real nice building. The general could not see me because he was busy with the Playmates. He was giving them a tour when I was supposed to see him. And these weren’t your average donut dollies. I told his aide you drag me all the way up here to see the general and I see him walking around with a bunch of girls. You guys sit up here in these plush offices, but I’ve got work to do. I said it wasn’t right and I demanded to see the general.

The general, a one star, finally saw me and straight out asked me what happened. I told him about the high casualty rate at the battery and said, “Sir, we need our ammo. If we don’t get it I’ll write every single newspaper in the country.” I got a little insubordinate with him. “If you arrest me every newspaper in the country will hear about it. A stupid thing that you can’t shoot at the enemy because you don’t have ammo.” I also hinted that Senator Howard Baker (of Tennessee) was a family friend. He was actually just an acquaintance. Baker was a real hawk. I said I’d send the senator a letter or call him from jail.

The general was real nice about it. He said, “OK, I just wanted the whole story. The ammo sergeant got upset, told his colonel at Betty, and that colonel called it up the line to me.”

The general was never belligerent with me, which I did not expect. But I wasn’t the typical young officer either. I already had seven years experience. I knew how far I could push the conversation without going too far. I also knew General Camp who was the Corp artillery commander. Camp was a guy who would back up his officers. This was late in 1969 when I was getting ready to go home in a few weeks anyway; I had a real short timer’s attitude.

Wanted Alive

One of my proudest moments was when I heard about VC propaganda leaflets that put a bounty on me and Hank Parker for a couple thousand dollars – each. I know one of the platoon leaders in the 506 also had a bounty out on him. They did not want me and Parker dead, they wanted us turned over alive, and then the whole family would get the money.

The highest bounty placed on a U.S. soldier was for the death of legendary sniper Carlos “White Feather” Hathcock. By his own estimate he killed over 300 enemy soldiers. The NVA gave Hathcock the nickname for the white feather he wore in his bush cap. They placed a $30,000 bounty on him, worth almost a quarter of a million today and a fortune in Vietnam at the time. The typical bounty on a U.S. soldier was $8 – $2,000, putting Lieutenants Taubinger and Parker proudly at the upper range.

Alex was promoted to captain immediately after leaving Vietnam on his way to his next assignment in Augsburg, Germany. He spent a total of ten years in the Army.

February 18, 2015

Alex Taubinger – Forward Observer – Part Seven

Born Again The Hard Way

On an operation just south of Song Mao we find a huge abandoned base camp and tunnel area. it’s a big find. Abrams is with us that day and when the word gets out about the complex a bunch of dignitaries come down: the squadron intelligence officer, a full colonel and a one star general. Abrams has me meet them at the chopper and bring them to the complex. Walking down the same trail we had just walked up I am leading the way and all of a sudden I step into a hole and I see a trip wire just touching my ankle. I say, “Oh shit.”

I freeze. We do not know if this things is live or dead. We call in a guy in who knows how to undo booby traps, a guy I know and the only one I trust, but he is nowhere near us. They bring me a five gallon fuel can to sit on while we wait. My leg is in the ground and I’m trying not to move and drinking one beer after another. It takes him an hour and a half for him to show up and now I’m about 20 sheets gone. He looks and roots around a little and says, “This fuse is all rotted. Pull your foot out.”

I say, “Are you sure?”

He laughs and says, “Yeah, pull your foot out unless you want to sit there the rest of your life.”

After my foot is out I dig around and find the explosive beside the fuse, a 105 mm howitzer shell. I put some C4 on it and blow it in place. I tell Abrams I think I’ve used up my three strikes.

Taubinger exposing land mine, fuse trap on right

It takes us about an hour and a half to get back to our base camp at the base of Titty Mountain, which contained an abandoned Buddhist temple. The chaplain is there setting up for a service. I walk up to him, “Chaplain, can I get a couple of those crosses?” He also gives me a rosary even though I am not Catholic. I tell him, “I’ve just become a born again Christian. I’m gonna start sitting in the front row whenever you show up.”

Turkey Shoot

We got intel one night that there was a North Vietnamese unit coming down through the Lee Hong Fong Forest about four miles south of Song Mao. That morning my platoon headed north with three tanks and four APCs. Each tank had a 50-caliber machine gun mounted on it and an M-240 coaxial machine gun at the turret. (comparable to the M-60 machine gun, but more reliable and also more expensive to manufacture) The APC’s had a 50-caliber and two M-60 machine guns. The whole floor of the APCs were covered two deep in ammo boxes. The tanks had beehive rounds and 90 mm high explosive rounds, plus again the floor was covered with ammo. That was a lot of fire power. You can imagine we didn’t run out of ammo.

When we got near where the NVA were spotted we got off the road and went into the woods for a sweep. When you did a sweep like that you had a tank on each flank. Usually the platoon leader’s tank was in the middle and you had an APC between the tanks on each flank. I told the platoon sergeant, Why don’t you take your tank in the middle, because he had more combat experience with armor than I did, and I’ll take my tank down the right flank up the tree line. He told me to stay in the middle.

Next thing I know we’re getting hit with a ground attack, B-40 rockets and everything else. We let loose with everything we’ve got, and right away I see my platoon sergeant’s tank on the right flank blow up. A B-40 rocket hit it perfectly between the turret and the body of the tank. The driver jumpe out, the tank is in flames, and we cover him to where he can make it to one of the other vehicles. He is the only one to make it out. The gunner, the loader and the platoon sergeant didn’t make it.

We backed off a little bit while I called in the 8 inch guns from LZ Sandy. I had them start the rounds 500 yards out from us and then walk the rounds towards us, all airbursts. I was trying to steer the enemy towards us. We were buttoned up in tanks and APCs, so we were safe from airburst shrapnel, unless a fuse malfunctioned and a round hit one of our vehicles. When the enemy came out of the trees it was almost like a turkey shoot. One guy stood up in front of a tank, he thought he could hurt us by shooting his AK-47. He had to be hopped up on something. The tank gunner said, “Should I smack him with the tube, or open the breech and yell at him?” Instead he just ran over him.

Then they all retreated back into the trees dragging bodies with them. And that was it. The whole engagement lasted a good 20 minutes.

The guy the tank ran over was still alive. While the medics were working on his leg he was sitting up and tried to pull a pistol from his pack. A soldier behind told the medic to move, then put two M-16 rounds in the back of the prisoner’s head, which blew the whole front of his face off. Like I say, he had to be hopped up on something.

My platoon sergeant’s tank burned for days. We had to just let it burn, there was no way to retrieve the bodies. They carried those people as missing in action for a long, long time until it was confirmed. We could not confirm them because we couldn’t see the bodies, so we had to call it in as three MIA. We wanted to pronounce them killed in action, but we were not allowed to.

Night Owl

The whole troop got the Combat Infantry Badge even though we were not infantry. Someone gave the troop a temporary infantry designation for 30 days so they could get the badges. All except me. Abrams wanted to do the same for me because I was part of the unit, to the point of acting as a platoon leader. I even went on nighttime ambushes because Abrams wanted a forward observer with them, so much they gave me the nickname Night Owl. But it was not in his jurisdiction.

4th of July

Fourth of July Abrams’ whole troop is parked a little north of Titty Mountain on the sand dunes. He brings up the subject: Be nice if we saw some fireworks. I look for a reason for a fire mission, and maybe I see lights moving on the side of Titty Mountain. I call into Sherry for illumination rounds, white flairs bursting high in the air and drifting down on little parachutes. And now maybe I see Viet Cong running for cover, so I bring LZ Sandy into the mission with airbursts of high explosive, and have Sherry shoot airburst white phosphorous along with continuing illumination. Now we’ve got our fireworks! Abrams says, “This is nice. It’s not like back home, but it’ll do.”

John Abrams retired a four star general, no small feat given his lack of a West Point pedigree. His older brother, Creighton Abrams III, retired a one star brigadier general. The youngest brother, Robert Abrams, is a three-star lieutenant general now serving in the Office of the Secretary of Defense. He is the only one of the four Abrams generals, including the famous father, to have attended West Point.

February 11, 2015

Alex Taubinger – Forward Observer – Part Six

The day I exchanged my bullet ridden helmet for a new one, that afternoon I went to an armored cavalry unit, Charlie Troop, 2nd Squadron of the 1st Cavalry. (A troop was made up of nine tanks, over 20 APC armored personnel carriers, and a total of about 100 soldiers – broken into three platoons.)

Charlie Troop M-48 medium tank

Armored Personnel Carrier (APC) of Charlie Troop

My troop commander was Captain John Abrams, whose father was General Creighton Abrams, then commander of all US forces in Vietnam. I had daily contact with Captain Abrams for the three months I was with the 1st Cav. He was a real nice guy; we were on a first name basis, even though he was a captain and I was a lowly lieutenant.

He was a hands-on guy and in the middle of everything. The first time I met him he was just coming in from the field and his right hand was all bandaged up. I saluted him and he said, “I can’t salute you back or shake your hand. This is what happens when you try to change your 50 caliber machine gun barrel without the glove.” He did not hesitate to get behind that 50 and start shooting things up.

The 50 caliber machine gun barrel could get hot enough to glow in the dark, sometimes hot enough to melt itself crooked. “The glove” was an essential piece of 50 cal crew gear.

Abrams knew everything about his troops. Let me put it this way. If you got a letter from your wife saying one of your kids was really sick, you could talk to him about it. He was a good one. I never felt like I was in any danger when I was with his unit. He knew his tactics and was the type of guy who told you to dismount your tank and charge with your bayonet, I’d say 90% of the guys would do it. I think a lot of that came from his father’s guidance over the years.

He told me once he applied to West Point but was not accepted. For the admission interview he had his hair cut short, wore a suit and tie. McNamara’s son and another VIP’s son interviewed at the same time, and both of them came in looking like hippies with long hair. They were accepted for West Point and he wasn’t. He said it didn’t bother him that much, except it was hard to make general without going to West Point. But he did alright. He retired a four-star general with nothing but praise from the people who worked with him throughout the years. He still keeps in contact with the people from Charlie Troop.

Everybody loved him. He was always out front with the troops. Sometimes he pushed the Abrams thing a bit. My first night there firing harassment and interdiction (H&I), he had me plot a bunch of targets along with def-cons (defensive concentrations) and friendly forces. I called them in for clearance and somebody called back and said because of the low ASR (ammunition supply rate.) allowed to us we couldn’t fire H&I. When I told the captain he went out to the commo van, got the guy on the line and said, “Listen. My name is Abrams: Alpha … Bravo … Romeo … Alpha … Mike … Sierra. My father is in Saigon with four stars. When my FO here calls in for anything, I don’t want anyone to tell him that he can’t do it.” After that if I wanted toilet paper delivered to the field they’d ask me how many helicopter loads did I want.

About two weeks later Abrams sent a platoon leader up to Cam Ranh Bay to be the liaison for supplies. Somehow word got to him that I’d spent some time with the 69th Armor down at Ft. Bragg, so he had me replace that platoon leader and put me in the platoon leader’s tank.

We are going through a wooden area and I am standing up through the copula, the hatch on the top of the tank where the platoon leader stands to look around outside the tank as its moving. I turn my head to the side and then look to the front just in time to see the tube catch a branch and the branch coming back at me. It has short spikes all over it, like its smaller branches had all been broken off. I raise my arms and it catches me on the inside of both arms, scraping off the skin and leaving spikes in my flak vest. Not a very dignified thing for a new acting platoon leader.

This is hilarious. We get a call one day from the liaison sergeant in Cam Ranh whose platoon I took saying the PX was throwing away pallets and pallets of Ballantine beer because nobody was buying it. (Ballantine was an acquired taste.) He said they were going to dump it into the harbor, or would sell it very, very cheap. Abrams called a meeting and said, “Officers ten bucks, sergeants five bucks, enlisted men zero. We’re gonna buy all the beer.” I don’t know how he did it but we had a convoy of lo-boys with tank protection all the way from Cam Ranh Bay down to us close to Titty Mountain. We’re brushing our teeth in beer. The water canisters hanging on the tank turrets are filled with beer.

Ho Chi Minh Footprints

Every day we did mine sweeps to clear the roads. We would look for a certain footprint from a Ho Chi Minh sandal (made from tire treads) we knew belonged to one guy. As soon as you saw it you knew there was a mine somewhere in the area. Then we looked around for loose dirt. His detonator was made from a split piece of bamboo with wires wrapped around each half and a spacer to keep the two contact points apart. The wire ran to a flashlight battery and the whole thing was buried about an inch in the ground. Anyone stepping on or driving over that spot would collapse the spacer and complete the circuit. The explosive was usually an unexploded 105 mm howitzer round or a mortar round. Except for the bamboo everything was US made.

No Good Deed Goes Uncriticized

We got a call that there was a booby trap on QL-1, the main highway into Phan Thiet, and that buses were refusing to move. We went up with our three Kit Carson Scouts (North Vietnamese Regulars who defected and acted as scouts for US troops). All three were ex-North Vietnamese officers. One of them even had his own separate NVA company. After they had defected they went back to North Vietnam and got their families and came back to work for Abrams. All three spoke English well enough that we did not need interpreters.

We found a 500 pound bomb laying in the culvert off the highway. Everybody looked at me, “Take care of it, will ya.” I packed it with C-4 plastic explosive and ran hundreds of feet of wire away from it. When we got all the people away from it, which was hard because they were curious, I set down behind Abrams’ APC thinking we’re plenty far away. I hit the clanker (hand detonating device) and when the bomb blew we had chunks of asphalt road dropping behind us.

Our scouts later told us, These people are really pissed at you guys. They want to know why couldn’t you have pulled it out with one of your tanks.

We Like You … But

I loved to drive the vehicles, but only got to drive two. Every time I drove something, the next day that vehicle would hit a mine.

Kit Carson Scout with APC Taubinger had jinxed

In background one he had never driven

February 4, 2015

Alex Taubinger – Forward Observer – Part Five

Part Five

Sometimes You Shouldn’t Advertise

We were working a mission with the RFPFs (Regional Forces and Popular Forces, sometimes called Ruff-Puffs) and just doing a grid sweep. We came to this village and somebody says, “Look at all those rockets hanging on top of that house.” Apparently the owner was proud he had a weapons cache in his basement. It looked like he was advertising.

House with rockets on roof

There were only women and children around. One of the Vietnamese, the guy with the baseball hat in the middle of the picture, pulled out a pistol and put it against a little kid’s head and started talking to him. He then fired a round next to the kid’s head that could easily have broke his eardrum. Now you could not shut the kid up.

Under the house we found hundreds and hundreds of rockets, grenades, you name it. It was a Viet Cong weapons cache, all brand new U.S. ammo and other stuff from North Vietnam. On one of the boxes you can see in the picture says 15 ROCKETS ANTITANK.

Stolen U.S. ammo

We started taking sniper fire so I called in artillery from LZ Betty. During the mission I did something I wasn’t supposed to do, I moved around while adjusting fire instead of staying put at a fixed point. In the middle of the firing I got a call from Outpost Nora, where B Battery had two guns on a mobile operation. They said they had been following the mission and wanted in on the action. I said, OK but first I want a smoke round. The smoke round came in 100 yards long and instead of bursting in the air landed between me and a Vietnamese lieutenant standing 20 yards away. It bounced off a rice paddy dyke and then burst. That’s a good example of why you always shot a smoke round first if you could. I instructed Nora to “DROP 100” and called for high explosive with an airburst. The first volley was on target, and before the second volley could come in I got a call saying they’d had a misfire and were canceling the mission. I think that was the day the gun blew up at Nora.

The mishap at Nora that day, killing Sgt. Johnson and PFC Handshumaker, was due to a faulty batch of time fuses used to create airbursts.

How a Helmet Works

Another Captain K incident, one that proved his undoing. We were in a village right at the base of Titty Mountain. We were working with the South Vietnamese again and our joint mission was to pacify and secure the village.

Note: A year earlier General Creighton Abrams succeeded Westmoreland as commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam. Westmoreland ran the war using search-and-destroy tactics with an emphasis on enemy attrition. Abrams pursued a very different clear-and-hold strategy, focused on winning the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese. He separated American forces into small units that lived with and trained civilians to defend their villages. Abrams also devoted vastly more time than his predecessor to expanding, training and equipping the South Vietnamese Army.

We had a MACV major with us and were all invited to lunch with the village chief. The major told me to get drunk first. I asked why and all he would say was, “If you don’t eat it’ll piss them off, and you do not want to piss off a village chief. To eat whatever’s put in front of you you’re gonna want to be drunk.”

I see them preparing ducks and I think we’re getting duck a l’orange or something. They bring out our plates with duck heads and duck feet on them. You were supposed to suck on them. Fortunately we got the rest of the duck a little later.

We spend the night there in one of his orchards. The next day around mid-morning we get a call from Titty Mountain saying there’s a whole group of VC coming toward the mountain. We have a jeep with us, so Captain K says, “Taubinger get your radio man. Let’s go. We’re going to attack.” It is all sand duns in that area. We jump in the jeep with a mounted machine gun and take off. The radio operators up on Titty Mountain are telling us which way to go. I get on the radio and talk to our guys up there, guys I know and usually talk to. I say, “You see me in the back of the jeep?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Keep an eye on me, because if I get killed I want you to write me up really good.”

They say, “What are you guys doing? There’s at least 30 of them out there.”

When I tell Captain K he says, “If it’s a platoon or less we’re going to dismount and charge them. If it’s more than a platoon we’re gonna drive through them.”

All of a sudden the jeep stops, stuck in the sand, and we have a flat tire. We’re up on top of a hill, and the guy I’m talking to up on Titty tells me the VC are only about 100 yards away in the scrub brush, but they’re not coming at us. My radio guy, Eddie Sandoval, and I start digging a hole. We pull the sand bags out of the jeep, pile them up, straighten the pins on our hand grenades, and dismount the machine gun. Captain K is yelling at his driver to fix the tire. The spare is flat, plus there is no way to jack up the jeep in the sand. Captain K gets on the radio to the rear for a resupply helicopter to bring out a tire. This is June 5, 1969.

Blackhawk hears this, the battalion commander. Apparently the VC don’t think we’re worth it and they go off. About an hour later Blackhawk lands. He calls Captain K over and says, “Here’s your tire.” Then he looks at me and says, “You’re in charge until I get a new company commander. I’ll have one by tomorrow if not tonight.” Our job was to pacify the village, not go out with a handful of guys in a jeep after an unknown number of VC. I suspect the word about Captain K had gotten up through the ranks to Blackhawk, and this incident of poor judgment was the last straw.

We somehow get the tire onto the jeep and go back to the village. Right away I send out a couple of clover leaf patrols (reconnaissance pattern in multiple directions around a central point, thus mimicking a clover leaf). One of the patrols observes the enemy setting up rockets aimed in our direction. They are setting up the big boys, the 120 mm mortars aimed right down in our direction, along with 210 mm rockets (over eight inches in diameter). The coordinates are at a crossroads with four buildings showing on the map, but I know they are not there anymore. I call in for an artillery strike and am told we could not shoot because of the buildings. I call back with a map correction that there are no buildings there anymore, but they won’t buy it. I’m almost in tears because I know what’s going to happen.

I start calling all over the place. The province chief is the only one who can give us permission. A Vietnamese officer tells me he is with some whore and not to be disturbed. So I say, “Fine, OK, but if we get hit I’m gonna kill somebody.” At midnight we get hit … hard … I see tracers going through the poncho which we were using for a makeshift roof over our fox hole. They hit you first with mortars, then rockets, and finally a ground attack. There is a beer sitting on the hood of the jeep. I grab it, guzzle it down, throw on my helmet and run over to a nearby rock wall. The nighttime listening posts I have out call in saying they are being surrounded. We need artillery support but nobody will shoot for us because we are in a village; all I can get is illumination. A mortar company of the 3/506 is right down the street from us. They say they’ll shoot for us, and start lobbing four-deuces (4.2 inch mortars).

While I am directing fire I get hit, I think in the back. It gives me a kind of whiplash and knocks my helmet off. I pick up my helmet and go back to pat my back where it hurts a little bit and my hand comes away all bloody. Doc Williams the company medic is right behind me and I say, “Doc, did I get hit?”

He says, “Get down or else you will.” I guess I am standing a little too high while adjusting the mortar fire.

The whole sky is lit up like daylight. We see only VC running around out there, and we’re starting to cut them down with the mortars. A Vietnamese lieutenant tells me they’ve got artillery right down the road and I say, “Why the hell aren’t you firing it for us?” The Vietnamese can do things we can’t and I know they have no problem firing into a village. He calls in the fire mission and after about half an hour we are able to silence the mortars and small arms.

Around 9:00 that night Hank Parker calls me. “Alex, where are you?” I tell him where I am and he says, “Yeah, you’re right up the road from me. By the way, if you hear some shooting, come down here and get me.” He is not too far away, two villages maybe.

I say, “What do you mean?”

“I’m in a bar with a bunch of Vietnamese, and the VC who kicked our ass today just came in for a victory party.”

The next morning I look at my helmet and see two bullet holes on one side and two more 180 degrees on the other side. The rounds had gone in one side, traveled around the helmet between the steel pot and the helmet liner, and out the other side. The helmet did what it was supposed to do. The blood I saw on my hand the night before must have been from a jagged piece of medal when I reached around to feel my back.

Taubinger helmet with bullet holes

A machine gunner also got hit in the helmet. The bullet hit right in the front of his helmet, went through everything and straight out the back, leaving a nice red streak across the top of his head.

We found out we had been up against over 200 Viet Cong, maybe as many as 300. We found well over 20 blood trails from them dragging off bodies. The nighttime listening posts had been surrounded all night, scared shitless the whole time. There are no U.S. casualties, but one Vietnamese soldier was killed and a couple wounded early in the attack. They were sleeping in hammocks, while the Americans were dug in underground. (South Vietnamese soldiers often slept in hammocks instead of foxholes.)

That morning a first lieutenant comes down with Blackhawk as the new company commander. He gets his captain’s bars a couple days later. The machine gun operator, my radio man and I go back that day to base camp at Betty. While I’m waiting for my extraction helicopter I call Hank. “You never called me for help.”

He says, “I bought a round and we’re all friends now.”

On the helicopter the machine gunner and I have our helmets on our laps. We look at each other and we’ve both got tears in our eyes. We were that close to dying.

I go into Betty, get a new helmet, and that is it. I wish I would have kept the old helmet, but I didn’t want it then.

That afternoon I go out to an armored cavalry troop to be their FO. The troop commander is Captain John Abrams, son of General Creighton Abrams.

January 28, 2015

Alex Taubinger – Forward Observer – Part Four

Part Four

Captain K

I replaced Hank Parker as the FO with D Company of the 3/506 Infantry right after Captain Wrazen was killed (Battle of LZ Betty, February 22). The new company commander who replaced Wrazen I’ll call “Captain K.”

Captain K liked to walk trails. Everybody tried to tell him when walking a train you walk about ten yards off the trail. He’d say, “No, no. When I was with the 1st Cavalry we always walked on the trails – to get their quicker.” As a result he was the only one who walked down the middle of the trail. The rest of us walked off the trail.

Battleship New Jersey

Just south of LZ Betty we had a free strike area, which meant you could fire on anything you saw moving. The Battleship New Jersey had fired into that area, and we went down there to do damage assessment and crater analysis. On the way we saw this big mound, a VC burial pile. Captain K had people dig it up and count the bodies. We did not dig it all up, just enough to guestimate the bodies. He called in a body count of 20 VC KIA.

As we approached the impact area we encountered burned trees, which got shorter and shorter as we progressed. In the center of a completely scorched area we find two craters. You could have parked a couple deuce and a halves (two-and a half ton trucks) in there and stacked them on top of each other.

That night we set up just south of the craters. A guy on guard duty who should have known better, because this was his second tour, the first with the Marine Corps, lit a cigarette in the middle of the night. A sniper bullet went in one side of his chest, came out the other side, and hit a guy sleeping on the ground in the thigh. A Medevac comes in and takes them both to Betty.

About an hour after that we start getting ground fire and mortar fire from Buddha Mountain, a mountain about four miles from the coastline, one of those high hills that just pops up in the middle of nowhere. You could see the flashes coming from there and the mortars landing all around us.

We are so far south of Betty that we are out of their artillery range. So I call up the Jersey for fire support. The target coordinates I give them is too far for their five inch guns. Their 16 inch monsters will reach, but because we are on the target line and the high dispersion factor they say, We’d rather not.

There were incontrollable inaccuracies in every fired artillery round. The largest dispersion was always in the distance it traveled, especially at longer ranges, as opposed to its left/right flight. Anyone sitting close to the target directly between it and the howitzer (on the target line) might find the round landing uncomfortably close.

While I am on the radio with the Jersey we begin to fire into the perimeter and throw hand grenades. I take advantage of the situation and tell the Jersey, We’re under a ground attack and we need help. We aren’t, but I want them to fire that 16 incher. They agree to fire one round, and when they do the whole ocean lights up. We hear the round going over our heads like a freight train.

Battleship New Jersey firing at night

When that one New Jersey round hits near Buddha Mountain everything quiets down for the rest of the night.

The next morning we start walking back up to Betty and come across the same burial mound we had dug up on the way in, which by now is stinking because we had disturbed it the day before. And Captain K calls in the body count again, saying we just found another 20 bodies. That’s the kind of guy he was. He wanted credit for a body count. Nuts! There was a body-count push then. They thought that would win the war. Each platoon had a polaroid camera at that time, to take pictures of every body to verify the body count.

Back at Betty we hear the poor guy hit in the thigh died, because a bone fragment got into his bloodstream. The guy who lit the cigarette lived. He was real chubby and the bullet missed his heart and his lungs and went clear through the fat. They ran a cleaning rod with a sulfur pad through him and sent him back out a couple days later.

The New Jersey patrolled the waters off Phan Thiet shelling targets of opportunity March 20 – 28, 1969. On April 1 she departed for Japan, having fired 5,688 rounds of 16 inch shells during her tour along the coast line in Vietnam. The one fired on Buddha Mountain was perhaps her last.

The Blue Lines

Captain K’s real claim to fame, completely in his own mind, was: “I used to teach map reading in ranger school. I know how to read a map.” Every sergeant, every platoon leader and all the Vietnamese we worked with knew he couldn’t read a map. Hank remembers him climbing trees all the time to figure out where he was, although I never saw him do that. I do know he usually had us in the wrong place. Thank goodness he never had to call in artillery, or any kind of fire.

We are looking for some POWs somewhere along the coast line about 20 miles south of Phan Rang. The helicopters bring us in on top of a low plateau along with a South Vietnamese unit commanded by the same battalion commander who earlier rescued us and who had walked that area since the 50’s.

On this plateau it reminds me of Tarzan movies. We’re walking along toward higher ground on the side of a cliff and all of a sudden rocks start flying down on us. We are being bombarded by a bunch of baboons. Then that first night we set up two baboons trip a flare on the trail and the machine gunner just wastes them. Captain K calls it in as enemy contact and reports we killed two NVA.