Ed Gaydos's Blog, page 7

February 10, 2016

Dick Graham – PLL Clerk – Part Four

Definition of Bad

When you’re in a war situation you can get close to people in a very short period of time. You’re on guard duty together; you work together; you’re in stressful situations together. It seemed like Rik Groves and Paul Dunne and I became really close.

I have very little memory of that summer, but I have some memory of the August 12 attacks. I had just gone over to motor pool and was visiting my old Gun 2 buddies, helping out with a fire mission when the mortars hit. Paul Dunne was wounded in the arm, and Rik got a lot of shrapnel in his back. I remember him asking me how bad he was hurt. I remember saying to him, “It all depends on what your definition of bad is.” It appeared to me he had a massive amount of pock marks.

I then remember going over to Stanley and yelling “Medic.” When Doc came over he pronounced him dead. I’ll never forget Doc and me picking him up to carry him away. He was so heavy! We carried him over to near the medics’ hooch near an open area where the Medevac helicopters came in.

Back on Gun 2 I sat down in the chair the phone operator used. I was light headed and I remembered to stick my head down between my knees so I wouldn’t pass out. It had a significant effect on me! Out loud I said this expression we used to help us cope with the stress. “Fuck it. It don’t mean nothin’.” We used that a lot, even though that kind of language was not part of my vernacular as I was growing up. We used that term for a lot of different situations. Basically it was to help you cope with negative emotions often for things that did mean a lot. If you got into a fight with somebody, of if your commanding officer told you to do something you thought was stupid, you just kind of did it and said it to yourself. It was a way of dealing with your emotions. What it did for me was it stuck things down. It sort of desensitized my emotions. Some guys rationalized the casualties as being “their time to go.”

The next night Gun 3 got hit and Pyle died and the whole crew was taken out. I was ordered to man an M-60 machine gun on top of the main ammo bunker. We had gun ships flying around, and Spooky up in the air with the mini guns flew around for a long time. That night I thought for sure I was going to die.

Gun 2 was hit in the early morning hours of August 12. Gun 3 was hit late the next night, but the same calendar day.

A Twisting Tale

Shortly after Gun 3 got hit, we had some Army Rangers in the area and the First Cav. Their job was to find out who was hitting us with mortars. When they didn’t seem to have any success, these Navy Seals, five of them maybe, they came into the battery. I remember talking to one of the guys. He’d been in Vietnam for seven years. I thought, how’s this guy going to be able to live once he gets back to the United States? They were dressed like VC, in black pajamas and with Ho Chi Minh racing slicks. The first night they were out they found the guys who were hitting us and things got quiet for awhile.

Dick’s memory of these few events triggered in Hank Parker, First Sergeant Durant and Andy Kach a chain of recollections. It’s a great example of how a detail in one guy’s story triggers other people in a kind of chain reaction, resulting in a wandering narrative typical of how things happened in Vietnam. Often small details don’t agree from story to story, but that’s not important, because every guy’s story is true to him.

Hank Parker, Executive Officer:

“I am glad Dick remembered this incident because I had forgotten about it.

“We were kind of numb during that period of heavy casualties (summer of 1969). We had been doing our own patrols in that area because the infantry wasn’t giving us support and we had been raising hell with our command. Hey, we’ve got the Q-4 counter mortar radar, we’re doing crater analysis, we know where these guys are at. Why aren’t you coming out here supporting us? Apparently they did and did not tell us. They may have figured because we had an ARVN (South Vietnamese) unit with us that if they told us the word would get to the ARVNs and then out to the VC. It wasn’t speculation. When I was out with the 3/506 we had an occasion where the battalion commander said the ARVNs need mortar rounds. I remember my platoon lieutenant saying hell no, these guys have enemy within their ranks so why would we give them our mortars? The battalion commander said because I am ordering you to. So we gave them three or four mortar rounds, and that night guess what? We got them back. Only they did not know to pull the safety pins and the mortars landed without exploding. Had they pulled the pins they probably would have killed us. But they did not pull the pins and we knew then that the ARVNs had some VC with them. The lieutenant went in and raised hell with the battalion commander and I thought he was going to get court martialed.

“I talked to the First Sergeant Durant and he remembers. We had movement just in front of the tree line so we did a sector fire, and the next thing we know FDC is calling CHECK FIRE, CHECK FIRE. We’ve got an American unit out there that had not been plotted. I called the tanker on our perimeter and the tank sergeant said, ‘Let’s shine a light on them.’ When the search light went on I remember them standing up waving their arms frantically. ‘Don’t shoot, don’t shoot.’

“When it got light they came into our perimeter with their prisoners and they were wearing black pajamas like their VC prisoners. I am not exactly sure what unit they were. We had the 3/506 Curahees of the 101st Airborne and I think the 2nd/1st Cav at that time too. The 101st had LRRPs (Long-Range Reconnaissance Patrol), so it could have been them. Then again I remember that we had Special Forces in Phan Thiet and I would bet they would have donned black pajamas for this kind of operation as opposed to rangers or LRRPs.

“They brought in something for the guys to look at, and Andy Kach took pictures of all the guys up on the truck crowded around so you can’t tell what it is – and I don’t remember. Then a command helicopter and a Chinook came in and picked them up with their prisoners.”

ARVNs Looking On

ARVNs Looking On

Pictures Courtesy Andy Kach

Andy Kach, Ammo Section:

“A group dressed like Viet Cong walked out of the tree line in front of Tower Two, about three hundred meters out. We had our M-60 machine gun trained on them, and were waiting for clearance to fire. They were not in a free fire zone, so we were waiting for clearance to shoot. By now half the battery was out on the perimeter watching. When they were half way to the wire these guys started waving wildly, and we got word that they were five Special Ops guys bringing in prisoners. I guess it finally dawned on them to let us know who they were. Helicopters were on their way to pick them up, and by the time they got to the chopper pad the helicopters were coming in. It was all pretty quick.

“That’s when Hank took two guns, 5 and 6, out to the perimeter and fired on the riverbed. That’s also when Hank and five other guys got the notion one night to sneak out through the wire by the main gate to test the readiness of the battery for a ground attack.”

Hank Parker:

“After that we were still pissed off that the access road was getting mined. The infantry wasn’t coming out to support us to get them. So Cerda said let’s go get them ourselves. He pulled out his black pajamas and said let’s go out there and have a little ambush on the road.

“I always wondered where Chief Cerda got his black pajamas to put on that night. They were wearing black PJs and that’s probably where Chief Cerda got his black pajamas. One of those guys must have given them to Cerda.

“So First Sergeant Durant, Chief Cerda and myself go out by Tower One at the entrance and we start wiggling our way through the wire, and Cerda got his butt caught on the wire and tripped a flare. The tower guard swings his M-60 around ready to shoot and Cerda starts yelling, “Don’t shoot, don’t shoot. It’s me, Chief Cerda!” All this was after too many beers. First Sergeant says it’s the dumbest goddamn thing we ever did.”

February 3, 2016

Dick Graham – PLL Clerk – Part Three

Shower and a Shave

In the collection of pictures Dick brought back from Vietnam is this sorry field shower. The best commentary for it comes from Dick’s good friend and crew chief, Rik Groves.

“You are looking at a marvel of GI craftsmanship of the highest order and a product of real genius in the American artillerymen of 1968-69! It offered solar heating of shower water . . . way ahead of its time, I might add, and was constructed of the highest quality material that the United States government could provide. In addition, it was eco-friendly . . . consisting of re-purposed materials in keeping with our concern for the environment which would come later. Finally, no animals were harmed in the making of this shower.

“It stood and served us well near the Gun #2 parapet at LZ Sherry. Upon closer inspection I’m surprised I allowed such a sloppy area around the shower, what with all the jerry cans laying about. This photo must have been taken late in my tour when my attention to detail was flagging.” (Rik Groves in an email)

Of almost equal genius was this shaving stand that Dick built from recycled ammo boxes, complete with shaving mirror.

Hilarious

I had five different battery commanders over the fourteen months I was at Sherry. I don’t remember their names or any specifics about their tenure. However, one of them brought in a Korean band and strippers one Sunday, as we were taking a lot of casualties and the morale was pretty low. They also allowed in prostitutes as a morale booster. Starting the next day guys were going to the latrine and just screaming because they all got gonorrhea. It was hilarious for me, not so much for them.

Not so hilarious was the brush growing outside our perimeter, which was getting pretty bad. It was a hazard because it was too easy for VC to sneak up on us. They tried to get people to come in and spray Agent Orange but it could not be arranged. We ended up burning it. Then of course what happened was all those varmints living out there came to the middle, which was where we were living. We had tons of snakes and rats and mice, you name it we had it. We had to deal with them for a couple weeks as I recall. We shot some of them, we set traps for others. The traps would go off all night and I remember having to reload the traps more than once before morning.

Promotion … To the Motor Pool

Sometime in August about half way through my tour, Top asked me to be a PLL clerk assigned to the motor pool. I think that the reason that I was selected was that I was one of the few college graduates at Sherry who wasn’t an officer. I don’t remember what PLL stood for, just that my job was going to be to order parts for the entire battery.

PLL stood for Prescribed Load List, military jargon for the items that each unit should have in its inventory. A PLL clerk ordered and managed repair parts, dispatched parts and equipment, and maintained all relevant records thereof.

I went back to battalion headquarters in Phan Rang for some training, though it wasn’t much. At Sherry I had an office, sort of, in a hooch and it was a mess. I don’t know if anyone did the job of a PLL clerk before I started. The hooch was a disaster. I tried to clean it up, and I’m pretty good at organizing. I suspect I may have been the first one to hold that job.

I had a hooch mate who was a Mormon and drove me nuts. I nicknamed him the preacher. He didn’t drink beer, he wouldn’t swear. Looking back it was a great testament to who he was and his faith, but he drove me nuts with his holier-than-thou attitude: “I don’t do this, and I don’t do that.” But he was a good mechanic and a good electrician, and he did a good job of maintaining the generators.

The maintenance sergeant was my boss and a great guy. He was a career soldier, I think on his third tour in Vietnam. He had been up and down the ranks. He said he got up to E-7 Sergeant First Class and then got busted down. He was an E-6 Staff Sergeant when I knew him.

He was amazing when it came to making due. We always had trouble getting brake master cylinders for our trucks.

When the brake pedal is pushed, the brake master cylinder located inside the wheel assembly uses hydraulic pressure to push a brake pad up against the rotating brake drum.

I would order master cylinders and they would send us handbrakes, even though we always looked carefully to make sure I was ordering the right number part. We did that continuously, but still had a problem getting master cylinders. And it was just as impossible getting brake fluid. A lot of the time the only brake we had driving our trucks was the handbrake. I remember the maintenance sergeant driving the truck, down shifting, and using the handbrake to stop. Without new master cylinders, he would take a tire inner tube and with pocket knife he’d make a brake pad for the old master cylinder, and then he’s use diesel fuel for brake fluid, which over time would eat through that rubber. Whatever worked!

The rear area didn’t have any problem at all getting parts. Their trucks always looked great, ran great. Out in the field we couldn’t get parts of any kind. A good part of the time our guns probably should not have been used, we called it red lining. They should have been redlined because of cracks in the barrels, but you couldn’t get them. During an inspection someone complained to a visiting general about not being able to get gun barrels and other parts. Shortly after that we were able to get them, and pretty much everything we needed.

One of our jobs in motor pool was to set the trip flares down at the main gate every night. One night I was setting the flares and one of the damn things went off in my hand. White phosphorous! My hand got really charred. I think everyone in Sherry unit could hear me swearing. I ran up to the medic and he put a huge amount of salve on my hand and wrapped it. You know that today I do not even have a scar there.

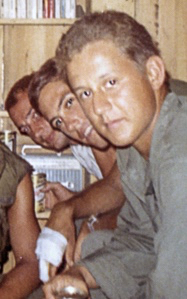

Dick in middle with bandaged hand

Dick in middle with bandaged hand

January 27, 2016

Dick Graham – Gun Crew – Part Two

Vietnam

I left for Vietnam out of Oakland, California. We flew on a super DC 8 and everybody on the plane was either infantry or artillery. Our first stop was Hawaii. They let us off the plane, and I went into the bar there and met a couple friends and had a couple Mai-tai’s. The whole thing was kind of funny because prior to starting basic they had you fill out a questionnaire and you got an opportunity to select three places where you wanted to serve. I put Hawaii number one on my list. So I got my wish for a couple of hours anyway.

After Hawaii we stopped at Wake Island which was nothing. The next stop was the Philippines at Clark Air Force base. When we got off the plane I could see these oriental looking people walking around, and it really hit me where I was going. Up until then I kind of compartmentalized it in the back of my head. It was about a two hour flight from Clark to Vietnam. We landed at night at Ben Hoa outside Saigon, and I remember sticking my head out the door to this overwhelming smell of dead fish. I could see the artillery in the background and I thought, Oh my, what have I gotten myself into now?

We moved to a holding area and as we are doing this there’s a bunch of guys waiting to get on the plane to go home. They are cheering wildly and here we are just getting there. I remember getting on a bus and the windows had bars on them so people couldn’t throw shit in at you, a grenade of something. I remember being very leery of anyone who looked oriental at that point.

We got processed at Long Binh a few miles away, and from there I took a plane north to Nha Trang. I was there for a couple of days and ran into somebody from college and we had the opportunity to go swimming. From there we went to Phan Rang to battalion HQ, and from there I went out to LZ Betty at Phan Thiet. I’ll never forget the chopper ride from Betty out to Sherry. The chopper clipped along ten feet above the trees. They said we were not so much of a target when we were down so low and could not be shot at easily. By the time they saw you, you were past them.

I was on that chopper out to Sherry with a black guy from Mississippi. Three weeks after we got to Sherry he was on a mine sweep and hit a mine and it killed him. (Percy Gully – April 2, 1969 – along with Steve Sherlock.)

Caught In A Compromising Position

Dick arrived at Sherry in March of 1969, and immediately went on Gun 2, BAD NEWS, where Rik Groves was crew chief. Within weeks Guns 2 and its crew went on a mobile operation to Outpost Nora with one other howitzer. On May 17 when the round with a bad fuse from Gun 2 detonated over the other howitzer and killed two of its crew, Dick and his crew had rotated back to Sherry. He therefore helped to build the outpost, but was not present for the mishap.

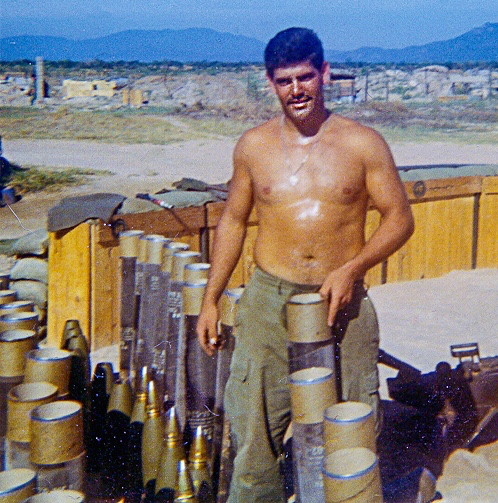

Dick Graham at Outpost Nora

Dick Graham at Outpost NoraI have a funny story from my time at Nora. When we moved there, the first thing we had to do was build the Fire Direction bunker and an ammo bunker, and then we could build our hooches. For quite awhile our latrine was just a hole we had off the side of the berm. I was down there sitting over the hole one day when all of a sudden a sniper started shooting at me. I’m scrambling up the side of the hill with my drawers down around my ankles, and the guys are laughing their asses off at me. They thought it was a riot.

Our perimeter defense at Nora were a bunch of Montagnards. They were there with their families. We would buy ice from them. When we first got there you got a pretty good size piece of ice for the equivalent of a buck. By the time I left you were getting one about a third the size for five bucks. They were good business people. And we had to be able to keep our beer cold after all! I remember we lived mostly on C-rations. They would fly in one hot meal a day. That was one thing about being in the artillery, you almost always got at least one hot meal a day. It was pretty quiet as far as I remember. We went there to support the infantry, but we did not have many fire missions to shoot, and I don’t recall any mortar attacks.

Just a couple months after I got to Sherry, sometime in May, I extended my tour 53 days so that when I got back to the States I’d get out of the Army right away. When you went back to the States if you had five months or less left on active duty they let you out. That was my goal, to get out of the Army ASAP! When I decided to extend my parents were just devastated. But it was pretty quiet when I decided to extend.

The quiet ended soon after Dick extended. The summer of 1969 saw a brutal level of attacks and casualties at LZ Sherry.

Loose One, Win One

I had a girlfriend in college, we had been going together for at least a year, and in basic training at Ft. Jackson I got the dreaded Dear John letter. I took that really hard. It made me angry, and I was already angry. I was hurt, and at that point in my life I expressed it as anger.

When I got to Vietnam I corresponded with a high school buddy who had gone through ROTC and was an officer stationed in Maryland. Rick had met this girl Judy there, and somehow she got to be my pen pal. Judy was wonderful. She wrote me probably five letters a week. These were not just one or two pages, some of them were eight and nine pages long. It was a wonderful outlet for me to express my emotions and frustrations about the war that I did not want to share with my parents. She was a godsend. I lived for mail call. As I recall we had amazing mail service. Letters only took three or four days. As it turned out Rick and Judy got married a week after my wife and I got married.

Convoy Memories

Convoy to Phan Thiet

Convoy to Phan ThietTommy Mulvihill at the wheel

Going on convoys into Phan Thiet you always had to watch out for your wallet. The kids were begging for money and candy, but they also tried to steal your money. They would come along and try to pick your wallet out of your pocket. One trick was to cut a slit with a razor in your back pocket to get to your wallet. I always kept it in my breast pocket, growing up in New York I knew about this kind of stuff. I’m just grateful we did not have to worry about people blowing themselves up around us.

One time on a convoy back to Betty I got an opportunity to call home. They did that through a series of shortwave radio operators.

The Military Affiliate Radio Service, known as MARS, used phone-patch connections over shortwave radios to place personal calls to the States. The lines outside the MARS stations in rear areas were always long, and it often took forever to make a chain of connections to the other side of the globe. The calls were limited to five minutes, assuming all of the radio connections held that long.

When they rang my parents’ house, wouldn’t you know it, the line was busy.

January 18, 2016

Dick Graham – Gun Crew – Part One

Duty

Dick was one of the many college students drafted into Vietnam. They were years older than the typical draftee, and educated to resist the traditional ways of turning boys into men. Thus on every front they clashed with what was still the Old Army. Yet once in Vietnam, beneath their cynicism, resentment and contempt for the military, they did their jobs with dedication and often heroism.

Of the 2.6 million who served in Vietnam, 648,500 were drafted. Many thousands more “volunteered” in order to select a specialty or delay induction by a few months. In the years after Vietnam senior officers who witnessed the transition to the all-volunteer Army say that draftees brought a diversity of skills and creativity that they miss in today’s Army.

My father was a veteran of WWII and his father was a veteran of WWI. When I was in high school we talked a lot around the dinner table about the Vietnam war, whether it was worthwhile or not. In our discussions I was not buying the domino theory.

I went to Ohio University in Athens and when the time got closer to when I was going to get drafted I started looking at my options. Not showing up for the draft and going to jail was not an option for me. I tried to get into the reserves, but you had to know somebody. You had to be sort of privileged, so that was not an option for me either. I had an aunt who lived in New Hampshire who wanted me to go to Canada; she had a place there I could go to. I considered it, but I did not like the idea of not being able to come back to the United States and visit my family.

January of 1968, my senior year in college, the draft board classified me 1-A (available for military service). Then I got a notice to take my written test. My draft board was in Pittsburgh and I was in Ohio, so they had to arrange for me to take the test in Ohio, which I did. I don’t think you had to score very high on it because I met people in the service who were probably intellectually disabled. A guy I bunked with in basic was from Harlem and he just had a terrible time and his hygiene was awful. I kept telling him, Why don’t you go AWOL?, and he finally did. Also, a guy I shared a hooch with when I first got to LZ Sherry I thought was intellectually disabled. He really liked the ladies. He had a collection of women’s panties in our hooch. It was just a rumor, but when he tried to re-up they would not take him.

After I took my written test, I got a letter to take my physical, which I was able to postpone until I could graduate. I got my degree in business but I couldn’t get a job because I was 1-A, nobody wanted to hire me knowing that I would be drafted. I got a job working part time at a department store. Then I took my physical, which I though I had a chance of not passing because I was born with a lazy eye. My left eye is only about 20/400 and cannot be corrected any better than that. I guess they figured you only needed one eye to shoot.

I got my draft notice in September telling me to report to Pittsburgh. A friend of mine from high school and college was supposed to go the same day I was, but he didn’t show up and went to prison instead. He turned out Okay. At one point he was a writer for the Boston Globe.

There were just twelve of us drafted in Pittsburgh that day. I always thought the Marines were all volunteer, but half the people that showed up that day went to the Marines. They had us count off 1 – 2 – 1 – 2, and the 1s went to the Army and the 2s went to the Marines. I was a 1; I caught a break. I truly think the reason I showed up in Pittsburgh that day came down to duty, not only to country but duty to my family.

Attitude Issues

I did basic training at Fort Jackson just outside of Columbia, South Carolina. The physical training part of basic training was always easy for me. I did not struggle with any of that. In fact, despite my lazy eye and the fact I had never handled a weapon before, I had the highest score in my company for rifle marksmanship.

It was the ridiculous stuff I couldn’t take. They had what they called zero week before training started when they gathered the recruits that would make up the company. I was walking down the street not paying any attention and failed to salute the company commander. They made me climb up a tree and say, “Tweet, tweet, I am a shit bird” for an hour. I can laugh about it now, but at the time I was pissed as hell. Looking back on it they needed to get my attention because I wasn’t buying all the stuff they were feeding us.

Our drill sergeant was just an ignorant Redneck as far as I was concerned and I had no respect for him at all. For the first couple of weeks when we ate our meals, we had to sit our asses on the front two inches of the chair, hold our tray in one hand, and eat with the other hand. You couldn’t cut your food. Finally the mess sergeant complained about it because we were not eating.

Every evening after supper for a couple of weeks, our company commander took all the college graduates outside his quarters and put us into the front leaning rest position (the up position of a push up). Then he’d walk back and forth telling us about going to Officer Candidate School. I wasn’t buying it. It was like, I want to be like you? Really?

In AIT artillery training at Ft. Sill we had quite a few college graduates, and a reserve unit from Missoula, Montana. Most of them had attitudes like mine. We never marched in military style, we always just walked along. Because of our general poor attitude we never had an overnight pass the whole time I was there. I didn’t mind, as I thought Lawton, Oklahoma was the arm pit of the world anyway.

Through Basic and AIT training I really struggled with respecting my commanding officers. The Army teaches you that you’re supposed to respect the rank, but the way I was brought up you respect the person and how they conduct themselves. Some of the old time sergeants I could respect, but it was the young officers and drill sergeants I had a problem with who couldn’t speak proper English. So call me an intellectual snob. My outlook did not get any better in Vietnam.

My orders for Vietnam came right after AIT, shipping me out through Oakland, California. I got I think 17 days leave prior to that. During that time I did a lot of soul searching because I was really thinking I was not coming back from this thing alive. I also partied a lot. I went out to SF a couple days early to party on Fisherman’s Warf. And I checked out Height Ashbury. And I went to a Carol Doda review, a famous thing back then.

Carol Ann Doda was one of the first topless dancers of her era, gaining international attention when she danced topless at the Condor Club in 1964. She enhanced her fame when she went from a bust size 34 to a siliconed 44, thereafter known as “Doda’s Twin 44s” and “The New Twin Peaks of San Francisco.” There was hardly a college age male in the country who was not familiar with the name Carol Doda. She passed away in 2015 at the age of 77.

January 13, 2016

Tony Bongi – Gun Crewman – Part Two

Nora

Gun 2, BAD NEWS, and Gun 5, BIG BULLET, were on a mobile operation at Outpost Nora, a barren hilltop north of Sherry. The evening of May 17, 1969, while shooting a fire mission in support of the infantry, a round with a bad fuse leaving the barrel of BAD NEWS exploded over nearby BIG BULLET, killing Lloyd Handshumaker and James Johnson. Three crewmen on BAD NEWS were also wounded: Tony Bongi, Tommy Mulvihill and Leroy Leggett.

At Nora before mishap(From Left) Bongi, Mulvihill, Leggett

Picture courtesy Tommy Mulvihill

At Nora before mishap(From Left) Bongi, Mulvihill, Leggett

Picture courtesy Tommy MulvihillI was in Vietnam just two months. It was a nighttime fire mission and I remember I was just in my shorts and combat boots. There was a big explosion, a huge white flash at the gun barrel. It blew me into a big pile of spent canisters behind the gun. I was fumbling around in those canisters trying to get out, but I couldn’t because they were sliding all over the place, and I finally got down to the ground and got up and went to my hooch for my rifle. I did not know what had happened. I thought maybe a sapper had got through the wire and threw a satchel charge or it was a mortar hit. After we tended to the wounded I heard Doc yelling, “Anybody else hit? Check yourself over.” I checked myself and on my right leg there were all these cuts and I thought, holy crap. I took a cloth and wiped it down and thought it was from when I hit the canisters.

Gun 2 BAD NEWS at Nora with brass canisters behind

Gun 2 BAD NEWS at Nora with brass canisters behind

The guys who were not wounded severely had to go down the hill outside the wire to secure a perimeter for the Medevac coming in. I was behind Mulvihill going down the hill and it was dark. He was wounded at the time I believe. We got down there and made a perimeter up against this tall grass. My rifle was on fully automatic, man, any little thing out there I was so keyed up I would have been blasting away, because we still didn’t know what that explosion was from and our little outpost could be overrun no problem. I’m a Catholic and this was one of those days when I said, Help me, God. The first Medevac came in and took off with the guys who were wounded, then another one came in to pick up the dead, Johnson and Handshumaker

After we got everybody Medevac’d out we went back up the hill, and we’re standing around talking all us guys with our M-16s and our flack jackets on, and you’re still trembling. Somebody said to me, I don’t know who it was, said, “Hey Bong, you’re bleeding, it’s going down your leg.”

I said, “That was from when I hit the canisters.”

He said, “No, it’s from the back of your leg.”

That’s when I pulled my shorts up and felt it. Doc came over to check it out and said, Tomorrow you’re going into Phan Thiet. They came and picked me up the next day to the hospital. I remember them freezing my right hip and then cutting it open. They pulled out a piece of shrapnel, not a big piece, sewed me back up, and said I could go back. They said, “Where are you from?”

I remember this, I said, “I’m from LZ Sherry.”

“LZ Sherry! Holy Christ. That’s a bad ass place.”

I said, “Well, you don’t want to go there.”

A coupe of weeks later I wrote home to my parents. I did not say anything about being wounded, just that I was OK, how many days I had left, stuff like that. A week and a half later I got a letter from my Mom saying that the Army had sent her and Dad a telegram saying that I had gotten wounded in the right hip and left leg. I said to myself, Oh my God, and she did not hear from me for a couple weeks. How the hell would that make you feel? Then I had to write her back and tell her I’m Okay and the Good Lord is taking care of me.

Telegram to Tony’s parents

Telegram to Tony’s parents

Note the telegram incorrectly states their son was wounded in the left leg, versus his right, an official error Tony continually works to correct at his VA hospital.

Thinking about it weeks later, when we set that gun up the metal stakes we put in the ground to build the parapet we had to pound down lower on one side because we were set up on a hill and would be firing down the hill. Thinking about it afterward I though we hit one of those stakes with a point detonating fuse. But the guys when we got together said, No, because you would have seen the blown out parapet. It was years later that Mulvihill told me it was a bad fuse.

That flash! I still see that flash. In my career as a fireman I’ve seen big flashes, like when electric lines come down and hit a car, and that always takes me back to Nam.

August 12

The date sticks in the memory of every guy who was there – the day two mortar attacks, one in the early morning and one late at night, killed two howitzer crewmen. Tony remembers the second attack that killed Howie Pyle on Gun 3.

I was still on Gun 4 with Tommy Mulvihill. When the explosion happened you could tell Gun 3 got hit and we ran over there. Tommy was the first one there along with a couple of us. The mortar must have hit right at the gun because the tires were flat and it was tipped to the side a little. There was a bunch of other guys there, all kinds of moaning and hollering and screaming and Howie was laying there gasping. Crap! One guy had a piece of shrapnel hit him in the left side under his armpit, it took that whole area right out of there, just gone. It was all horrifying to see – you’re 18, 19 years old and you’re seeing this shit. How do you come out of that?

The medic then told us all, “Come on guys we still got a fire mission to shoot, get back to your guns.” We had to go back to our gun to continue the fire mission, shoot illumination rounds, and we shot some beehive rounds out there worried about a ground attack. So we couldn’t really help, we had a limited number of guys. Mounting casualties over the prior two months had severely depleted the battery.

We put up a star on top of the FDC bunker with lights one of the guys got from home. A cease fire came down for Christmas, but somebody forgot to tell the enemy there was a ceasefire. Let me tell you they zeroed in on that lit up star with the mortars that night. They clamped on that sucker. Still it was a merry Christmas because nobody got hurt that night.

The best part was a Christmas package from Andy Kach. Andy and I became pretty good friends. When he left I was a little depressed because he was a good guy. He said, “Tony, when I get home I’m going to send you a bottle.” Well son of a bitch at Christmas time I got this package from Andy and we opened it up and it was a bottle of Seagram’s. We sat around and toasted Andy. He wasn’t even twenty-one, he couldn’t buy the bottle, he had to get his dad to buy it.

Tony on left with pipe and Seagram’s

Tony on left with pipe and Seagram’s

January 6, 2016

Tony Bongi – Gun Crewman – Part One

Into the Army

I got my draft notice at the end of 1967. I did not enlist. Guys from my area, the town of Iron River in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, went to Milwaukee for physicals. A taxi picked me up and took me to a town to the east, Channing, and there was a railroad depot there. They ran passenger service down to Wisconsin. We got on that train to Milwaukee. There they picked us up on buses and took us to a barracks kind of building. The next day we had our physicals and of course the guy said, “Oh no, you’re in good shape.” We came home on the same train and a taxi was there to take us home.

When I got my notice to report for duty I did the same thing, a taxi picked me up from my house. On the way to the train station in Channing we picked up another guy in Crystal Falls and another guy in Sagola. The Channing station was due to be closed, and we were the last train out of there.

The train took me to Ft. Leonard Wood in Missouri for basic. I remember the barracks were these old wood buildings with cracks showing through in the walls, so that a sand storm came through and laid that shit all over the floor, which we had to clean up. In there we had a coal burning stove for heat. We had to stoke the stove with coal so we could stay warm in there, and you had to do a fire watch every night. It was always rainy and there was always moisture in the air. Holy Christ, every frickin’ day.

We would do our calisthenics every day, and when we went for lunch at the door of the chow line there was a chin up bar. When the line went through you had to jump up on it and do I believe twenty pull-ups. I was a little bit chunky when I went into the Army and at first I could barely do it. At first it was tough on everybody, but then we got in pretty good shape after three or four weeks.

You went through the chow line and they had chicken and pork chops and mashed potatoes. I was starving and I’m walking through the line and packing my tray up. I get to the end and there’s a drill sergeant standing there. He looks at me and he looks at my tray and he says, “Hey, fatty, where you goin’ with all that food?”

I say, “I’m gonna eat it.”

“No you’re not,” he says. “Put it down and go back through the line.

Son of a bitch, I have to go back through the line and get half of what I had the first time.

The Advantages of Being a Yooper

After I graduated from basic I went to Ft. Sill for artillery training. Where we were stationed was called Kelly Hill. I don’t know how I got into artillery. Your first week at basic you have all kinds of testing, so I guess that’s what got me into artillery.

They had a baseball team there and they asked if anyone wanted to play on the team. I played at home so I raised my hand. They took me for a tryout and afterwards said, Okay, you’re on the team.

And then one day at formation they said, anybody here know anything about pistols. From living up here in the U.P. you did all that stuff. We were shooting guns when we were six years old. I raised my hand and they said, come with me. There were a few other guys too. We shot the Colt 1911, the big. 45 caliber service pistol, but these were not .45s; they were .22 target pistols built on the same frame that went into combat as a .45. I got on the shooting team with these .22 pistols and we shot in competition around the area.

I was also on a burial detail. We went all over the country to bury old soldiers, from WWI, WWII and Korea. This one time we drove down to Florida and we went into this old cemetery, with vines and moss hanging all over the place. We also shot the seven gun salute.

I also became the Sergeant Major’s jeep driver. They asked us, Can anyone drive a jeep in rough weather? Where I came from everybody had a four wheel drive vehicle. I raised my hand and became his driver.

I still had to go to classes and all the training exercises, but I didn’t have any details like KP because I had these other activities and had to be at Sergeant Major’s beck and call whenever he wanted to go somewhere. One day we were headed out to the shooting range. It had rained the day before. We were in a flat and sandy soil muddy area. He wanted to go out into the field, but I said, “Sarge, it’s pretty muddy out there.”

“You can get out there,” he said, “you got a four wheel drive jeep.”

I went into the field and we got bogged down. I was spinning the back tires and it was throwing mud all over the place. There were two levers in the jeep, a shorter one to engage the four wheel drive, and the taller one would put it in either high gear or low gear. I reached over and pushed the small lever forward and pulled the big lever back, which put me into four wheel drive in low gear. When the front end engaged it threw mud all over the Sergeant Major’s whole right side as we took off. We got out of the field, and got out of the jeep, and he was cleaning off his arm and shoulder and leg. I went over by him and said, “You okay?”

He said, “That was pretty good driving. Where you from, boy?”

I said, “The Upper Peninsula of Michigan.”

He said, “Where the hell is that?” and walked away.

Every Day in Vietnam

I shipped to Vietnam from Ft. Lewis, Washington on a commercial flight that stopped in Anchorage Alaska, then at a big airport in Japan where we flew by Mt. Fuji, then into Cam Rahn Bay, Vietnam – the hell hole.

From Phan Thiet they drove three of us out in a deuce-and-a-half truck. Right inside the main gate of this firebase I saw this big sign with the mortar fins and said to the driver, “What the hell is that?”

He said, “LZ Sherry.”

Picture courtesy Andy Kach

Picture courtesy Andy Kach

I wasn’t there three days when we got mortared. You talk about scared shitless. Every day that I was in Vietnam I was scared shitless. There were only short times when you got it off your mind, like in Mulvihill’s hooch drinking beer. But sometime during every day you were reminded and every day something scared you, either from a mortar attack or a sniper shot. When you got snipered at the bullet would whiz by you and hit something. When you first got there you didn’t know what it was and said, “What the hell was that?” and one of the guys would say, Get down, get down. That’s how new guys got shot, standing around asking, What the hell was that? Or something said in morning formation at the XO’s hooch, like there’s lots of movement to the northwest so be ready for an attack. An then there you go, you were scared. Then they put up that tall radar tower when I was there, and I thought holy Christ that’s attractive to the enemy, they’ll zero in on that right away.

Tony unpacking ammo on Gun 4

Tony unpacking ammo on Gun 4

Then there was the mine sweeping on convoys, which Mulvihill and I usually did together. He would have the mine sweeper out in front with me following. When he picked up a signal he’d go round and round the spot, and at the strongest point he laid the sweeper down lightly on the sand, and when he picked it back up it left a ring. Then the guys would go in with a knife on either side to try to find it. One time Tommy said to me, “Here, Bong, hold my gun, I got to go up there and probe.” He found it, and we all backed off, and they blew it up, but talk about being scared.

December 16, 2015

Chuck Monahan – Executive Officer – Part Three

Outpost Nora

B Battery sent two guns on an airmobile operation to a rocky hilltop called Outpost Nora. Only one thing about Nora has stayed with him.

The only thing I liked about Outpost Nora was a baby girl named Chi (pronounced Chee). She was a favorite of mine. That little girl stole my heart.

Monahan and Chi

Monahan and Chi

Picture courtesy Rik Groves

Acting Battery Commander

In May I was the XO. Hank Parker came back to the battery and they made him assistant XO since we already had a Fire Direction officer. Our new battery commander, who was fairly new to the battery, was either back in Phan Rang for extended periods or invisible in his hooch – the men called him The Ghost. He was gone so much Hank and I basically ran the battery. I wasn’t close to this guy and could never understand why he was given a battery to command. After I left, toward the end of July, Hank Parker became XO.

I heard that the battery commander was relieved of his command shortly after the mortar attacks on August 12 and Hank Parker moved into the battery commander slot.

Leaving Sherry

Just before leaving Sherry for home Lieutenant Monahan experienced a close call which he does not remember, but which others guys remember in detail.

Dave Fitchpatrick, Gun 5 Section Chief:

“I was at the gunner’s sight on Gun 2, and Rik Groves was standing beside me. We were maybe a foot apart, and saw VC running way out there. Could see them running around some bushes. We’re standing there and hear a pfffffft. What the hell was that? We didn’t know what it was. And then we hear another one, and it goes bing, bing, bing, bing – it hit something. Then we realized we were getting shot at, and we no more than turned around and Lieutenant Monahan comes out of his hooch. He was getting ready to go home in a day or two, and like all short timers took a special care not to get killed. Another round hit behind him and you could see it kick the sand up. He leaped I’ll bet 20 feet. I’ll never forget that sound, when a bullet comes that close. If it was any closer one of us wouldn’t be here today, or both of us would be gone – or hurt bad. The First Sergeant told us to shoot back, even though we didn’t see any weapons. We shot back into the brush pile with the howitzer and killed all of them.”

Chuck Monahan the day he left LZ Sherry

Chuck Monahan the day he left LZ Sherry

Picture courtesy Rik Groves

The last thing I remember about LZ Sherry was the chopper coming to get me. I am on the chopper and I asked the pilot to circle the firebase. I looked down and felt bad about leaving. That I do remember. I felt like I was letting the guys down. I cared about the guys. I wanted to get home safely and I wanted them to get home too. Unfortunately, for some of them, that did not happen.

Home

I was home just a few weeks when I got a letter from Rik Groves telling me Howie Pyle had been killed. Howie Pyle was the section chief on Gun 3, our base piece. He was officer material, a good leader, quiet, humble, very efficient, got the job done. He ran a good section, which is why he was on base piece. I was so sorry to hear he had been killed.

About four months later I got a letter ordering me to report for reserve duty. I had to do three years active reserves. I was 29 days short of having three full years of active duty, so I had to do the reserves. I was pissed. They assigned me to a unit in Boston, an artillery unit in Roslindale, so I had to drive from Springfield once a month (about 100 miles) and then go away for two weeks during the summer. Most of the guys who got into the reserves were avoiding the draft. The guys in my unit had no military bearing. They could care less. As much as I hated reserve duty, I still I loved the guns, the smell of the gunpowder.

During the spring of 1969 I wrote a letter to Springfield College asking if I could come back. I got accepted and returned to school in September 1969 on the GI Bill. I finished up in two years, but my senior year I was getting married and I didn’t think I had enough money to stay in school. I worked in the registrar’s office and when I told them I was going to withdraw, they said not so fast and got me a full academic scholarship my senior year.

My Memories

I remember the mortar rounds coming in, the illumination rounds going up, and trying to get a back azimuth from the incoming mortars. Yet there is so much I cannot remember. One thing I will never forget, and that is the dedication of the gun crews and everyone who supported them. No doubt about it. They humped their asses twenty-four hours a day. Some nights they fired all night, and one night we nearly ran out of ammo. So they decided to increase what we could hold and built another ammo bunker. We had close to 4,000 rounds after it was built. Still we fired so much it was tough to get us resupplied, especially at night when most of the fire missions took place. I can remember nights the guns would get so hot that when you threw a round in the chamber the gun would fire by itself. We had to follow a DO NOT LOAD, FIRE ON COMMAND protocol (projectile loaded only when ready to fire). There weren’t many batteries in Vietnam that shot as much as we did.

When there weren’t fire missions at night there was guard duty. Then in the morning there was more work: gun maintenance, ammo resupply, sandbag duty, barbed wire repair, and all the other endless jobs that kept a firebase operating and secure. It was tough work on those guns.

B Battery guys were serious about what they were doing because they knew guys in the infantry were depending on them. Most of our guys were good guys, who cared about what they were doing. If they didn’t the gun crews straightened them out.

Those were the thoughts going through my mind as I circled LZ Sherry for the last time.

Maybe those are the memories that matter the most.

December 9, 2015

Chuck Monahan – Executive Officer – Part Two

LZ Sherry

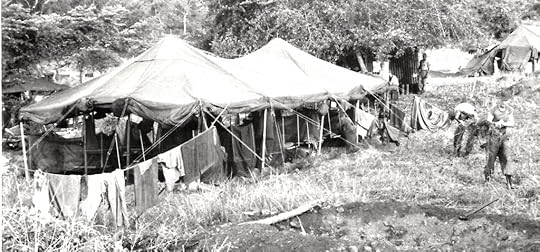

When I got to Sherry in late October of 1968 it was mostly tents. Maybe there were a few hard structures, but it was mostly tents. Willie J. Ridgeway was the battery commander, a pretty easy going guy and a good battery commander. Very soon Captain Gilliam became battery commander, another competent officer I enjoyed working with.

First Sergeant John Farrell was tough, by the book, which I liked. If you didn’t have discipline out there, managing the battery would be difficult. He was forceful, aggressive, and a good First Sergeant.

Sergeant First Class Cerda was Chief of Smoke. He was a seasoned veteran who knew his stuff and was respected by everyone.

During my time at Sherry we had great NCO’s which made life a lot easier for everyone. The gun chiefs and other section chiefs took their responsibility seriously, looked out for and treated their men fairly.

Monahan at LZ Sherry

Monahan at LZ Sherry

January, 1969 Ground Attack

I was the Fire Direction Officer at the time and was in FDC because we were in a fire mission. The tank on our perimeter called in and asked if there were any patrols out. The guy who was on the radio in FDC looked at me and I said, “No, we don’t have anything out there.” So the tank guy came back and said there’s something in the wire. The radio operator said, “Then fuckin’ fire.” It was over as quickly as it started. Saved a lot of lives. I remember walking around seeing all the bodies, especially the body people called Head-and-Shoulders. I remember two guns went out that morning on an operation, and I don’t remember much about the cleanup.

Lieutenant Colonel John Crosby, Battalion Commander, remembers the aftermath:

“I got the report the night of the attack and I went down early the next morning. The Task Force South commander also came down that morning. I took pictures of all the dead VC, their rockets, their AK-47s and other ordnance. We knew that we wiped out the entire sapper unit because the leader had a roster of all the sappers in his loincloth, and so we were able to count the people in his sapper unit, the KIAs and the one guy that was captured. We got ‘em all. We counted them off and every single one of them was laying out in front of us. I think it was 14 KIA.”

Monahan over mortar site

Monahan over mortar site

February Loss

The night that LZ Betty got hit (February 22, 1969), Captain Wrazen was supposed to come out the next day to Sherry. I had invited him out to see and visit the guns because he had never been on a firebase.

I used to stay up a lot at night, so after breakfast I used to crash for an hour or so. The First Sergeant came in and woke me up and said, “Your buddy’s not coming out.”

I said, “What do you mean?”

He said, “He was killed last night.”

Lieutenant Hank Parker, who took Monahan’s place as forward observer with Delta Company, fought beside Captain Wrazen that night.

“Wrazen tells me to take up a position at the gullies. I rip an M60 machine gun off a jeep and Wrazen tells me where he wants me to go, just down from a bunker he is occupying. I am close to him, maybe ten feet away. He is in the open on the top of a French bunker, a concrete bunker with ports. You got enemy fire and mortars coming in and tracers both green and red flying in all directions. I look over and see his body jerk and then go down. I run over to him and arrive at the same time as First Sergeant Horn and another lieutenant. Wrazen is already dead I think. They get a jeep and take him to the battalion surgeon. I continue on doing what he told me to do securing that part of the perimeter that was in front of the tower with the steep incline in front of it.

Snakes Beware

In April, six months after arriving at Sherry, 1st Lieutenant Monahan became the battery executive officer, second in command behind the battery commander. His new title did nothing to warn away the local wildlife.

My hooch was a pretty good size hooch. We had three or four people in there, officers and First Sergeant Farrell. One day there were snakes in my bunk. I hated snakes. I always had my .45 pistol with me and I grabbed it and started shooting. It was stupid to do obviously, it could ricochet. I remember Farrell being in the hooch behind me and he had to stop me.

This incident, told so simply by Monahan, has worked its way into the lore of B Battery.

Tom Townley, battery medic:

“Farrell slept in the same hooch with the XO, 1st Lieutenant Monahan. It was the beginning of the wet season, the rainy season, so it must have been around June or July 1969. I remember because that’s about the time I went to the rear. The rain came at 5 o’clock every day, you could count on it. And it rained so hard you could not see. One night Monahan – a big guy – went in his hooch to crawl in bed. We all had mosquito netting, especially during the wet season. He crawls into bed and pulls the mosquito netting around him and feels this movement. He did not know what it was. He pulls back his sheet and there is a six-foot cobra in bed with him. My hooch was next to his, and all I heard was a .45 pistol going off. Boom. Boom. Boom-boom. Boom. Boom. Boom. Farrell was there and had to stop him. I don’t think Monahan ever did kill the snake. I don’t remember seeing it afterward, so I don’t think he ever did kill the snake. But he sure put a lot of holes in his bunk.”

The snake incident even made it back to battalion headquarters in Phan Rang, to Lieutenant Colonel John Crosby, who has his own version of the story:

“When I took over the battalion a guy by the name of Farrell was the First Sergeant. Captain Ridgeway was the battery commander, a darn good one. Later on the executive officer was a sharp kid from Boston and had a New England accent big time.

A typhoon with heavy rain came through one night and hit right there at Phan Thiet. LZ Sherry had a little bit of elevation to it, not much, but some. The lower surrounding territory got flooded, and a whole bunch of cobras came from the wet area into the battery.

The XO was in his hooch in his bunk and he felt something hitting him on the rear end, a bump-bump-bump kind of thing. He got out his flashlight and looked at the wall, which was made out of ammo boxes, and he saw this snake’s tail between the ammo boxes. So this kid reaches in there, grabs the snake, pulls it out and it was a cobra. Shocked into action he pulls out his .45 pistol and starts shooting. His hooch mate Sergeant Farrell came in and calmed things down, but Farrell was really afraid of snakes. He just had to look at them and he’d get sick on his stomach.

Six or seven cobras were killed in the firing battery area. None of the snakes were real big. It looked like a whole family that was just born to a mother cobra; her nest got flooded and they all came up into the battery area. That was the excitement for the night.

The next day after the typhoon I went out with a supply of anti-venom serum.”

December 2, 2015

Chuck Monahan – Executive Officer – Part One

The Road to Nam

I was in school at Springfield College in Massachusetts in pre-med, but I was a party-hearty student and after two years they asked me to leave. Through the local selective service I found out that I was coming up quickly for the draft and seeing as how I was interested in the medical field I enlisted to be a medic. I went to basic at Ft. Jackson in South Carolina. One of the training officers took a liking to me and asked me if I wanted to go to Officer Candidate School. I thought, what the hell, I’m in the Army I might as well make the best of it. I graduated from Artillery OCS at Ft. Sill, and from there went straight to Germany as a fire direction officer on 155 mm self-propelled howitzers.

Being in Germany was great with the exception of winter maneuvers. After a year in Germany I volunteered for Nam, and then thought about how crazy that was. I went to my colonel who was able to pull it back, but a week later I came down on a levy for Vietnam anyway.

Funny to You Maybe, But Not To Me

When I landed in Nha Trang I got assigned to 27th Field Artillery Regiment and I said, “What the hell’s that? What kind of guns?”

They said, “What kind do you want? The 27th has everything.”

I requested 155 mm Self Propelled because I was familiar with them. They told me that I would like 105’s. So at the 27th headquarters down in Phan Rang they assigned me to 105s at B Battery. But I didn’t go to the firebase right away. The rule was new lieutenants had to spend time as a forward observer, so I went up to Pleiku for forward observer school. Outside of the FO training at Ft. Sill I did not have any experience calling in artillery, and I don’t know how much the school helped to be perfectly honest.

I’m getting ready to deploy with Delta Company of the 3/506 Airborne Infantry out of LZ Betty. I’m 22 years old, green as can be, and in Vietnam for just a couple weeks. They said, “How much ammo do you want?” I must have taken half a dozen bandoliers with me. (An M-16 bandolier held seven ammo clips and was worn across the chest.) When I got on the chopper they laughed at me saying I was weighing down the helicopter.

They choppered me out to Delta Company in the field. I don’t know where I’m going, and they’re hovering over this elephant grass, and I see smoke, and they’re telling me to jump out. I say, “No way.” The Delta company First Sergeant is on the chopper with me and he pushes me out. From the ground I look up at the chopper and give him the finger, and he just laughs. The chopper takes off, I am all by myself, I don’t see anyone, and I am more than a little nervous.

Welcome to Vietnam. Then two guys come out of the brush and get me. What goes through my mind is, Why didn’t I study harder?

A couple of nights later we were set up in our nighttime position. It was September during monsoon season. I had called in rounds on one of the defensive targets I had set up around our perimeter, and it was wet and dark but quiet. Later that night one of our perimeter trip flares goes off right in front of us. I freeze. I look around and nobody’s moving. How come nobody’s moving? Then our Claymore mines go off. Not being familiar with claymore mines, I’m thinking that this is the end of the world for me. I jump into a foxhole and get ready to call in artillery, but it’s over before it started.

Captain Gerry Wrazen was my salvation. He had a great way about him, just exuded leadership. Confident in a mild mannered way. He was a natural. I was a very green and inexperienced FO in a tough infantry unit, and it was Captain Wrazen who helped me get along. He let you know he trusted you and I got close to him quickly.

Captain Gerry Wrazen

Captain Gerry Wrazen

ADD 500

We had little skirmishes and small firefights during my time with Delta, and I had one bad night. It was still September with heavy monsoon rains, and from constantly trudging through the rice paddies everybody’s feet were beginning to rot. You never walked on top of the rice paddy dikes where it was dry, you always walked down in the paddy. It was so bad they brought the whole unit back into LZ Betty for three or four days of recuperation.

When we went back out to the field, October 4, that night around 7:00 we went to the southern end of Betty and were waiting for darkness to fall before heading out. Just as we are about to leave, word comes back from our point telling us that he thought he heard movement out in the rice paddies ahead of us. We looked at the map and it was a no-fire zone; there were a lot of those no-fire zones. If you were not in contact, it took an act of Congress to get permission to fire. We looked at each other and Wrazen said, “To hell with it. let’s just move out. It’s probably nothing.”

We started to move out. But this time because we had just recuperated from our feet being messed up, he said to walk on top of the dikes. We’re walking on the dikes and all hell broke loose. They had us in a cross fire with automatic weapons, and they started mortaring us. It was like nothing I had ever experienced. Everybody dove into the rice paddies. I got separated from my radio operator. I reached for my maps, and even though there was plastic on them, they were covered in mud. I am trying to get my bearings on the map to call in artillery. Meanwhile, Wrazen thought I was hit because he had yelled for me and I didn’t hear him, so he called for gunships. I got my RTO back, called to B Battery, and threw out a grid for them to fire on. I think I called for a white phosphorous round. I was laying on my back in the rice paddy – I remember this like it was yesterday – looking for the WP round to come in and there was nothing. I saw and heard nothing. I told the firebase to ADD 500. Now where did that come from?

Add 500 meters to the last shot. This was a daring adjustment, over five football fields, especially since the first shot was nowhere to be seen.

They fired and now I saw it and it’s close enough, so I started to adjust high explosive rounds on the target. The rounds started to land on the side of a hill close in front of us. I got real cautious since we in danger close range and I was leery of bringing them in any closer. About this time the gunships were coming in, which meant we had to wave off the artillery. The gunships quieted things down, allowing us to get to the side of a hill and dig in for the night.

I remember the next morning I had these huge blisters on the inside of both arms opposite my elbows. They were like large bubble gum bubbles. I called for the medic and then said to Wrazen, “I’m going home, baby; see you later.”

He looked at doc and said, “Bandage him up, he’s coming with me.” Doc poked the blisters, put some type of cream on, wrapped them, and that was it. I know we took casualties that night, but I don’t know how many and don’t remember the Medevacs.

Almost Famous

A photographer from Stars and Stripes embedded with the 101st took this picture of me as we were crossing a rice paddy. I had no idea there was a photographer with us, much less that he had taken a picture of me. One afternoon Captain Wrazen called me in and handed me a large glossy of this picture and said, “You created quite a stir.” He told me they were going to publish it in the paper, that is until the general got wind of it. The general went ballistic because the picture showed I had cut my sleeves off just below the shoulder, which I did because of the heat, but he thought defaced the uniform. Wrazen said, “The general yelled at the colonel, and the colonel yelled at me.” Of course it didn’t bother Gerry Wrazen at all. He shook his head and said, “Don’t ever do that again.”

I was an FO for just a month or two before going to Sherry. Most guys were out there for four or five months, some longer. You either hit it right, or you got screwed, and I hit it right. It was just the luck of the draw.

November 11, 2015

In The Beginning

Fifty years ago on November 3, 1965 the boys of Battery B arrived in Cam Ranh Bay with the 5th Howitzer Battalion/27th Field Artillery.

The 5th Battalion had been activated just two years earlier on June 20, 1963 at Ft. Lewis, Washington. At first it was an empty battalion with just a headquarters staff, and under orders to form three 105 mm howitzer batteries of six guns each. B Battery came into existence sixteen months later on October 29, 1964. John Santini, assigned to the battery as a gun crewman, says of that first crew:

The original B battery was like a melting pot of all different people. We had our stragglers, but B battery was a STRAC unit (Strategic, Tough and Ready Around the Clock). We could do any mission the Army wanted of us.

First B Battery gun crew on a field exercise, Ft. Lewis

First B Battery gun crew on a field exercise, Ft. Lewis

Staff Sergeant Dabney

Staff Sergeant Dabney

First B Battery Chief of Smoke

At Sea

B Battery was barely a year old when the battalion left for Vietnam in early October 1965. The battalion was staffed at 512 personnel (27 officers, 3 warrant officers, and 482 enlisted), four short of an authorized headcount of 516. John Santini describes the departure.

From Ft. Lewis we got on busses for Sea-Tac airport in Seattle. Walking through the terminal we were in full combat gear, with our helmets and M-14 rifles. People stopped and looked at us, some of them applauded. We boarded a plane and went to Oakland, California. As we were getting off the plane every one of those stewardesses lined up at the door and gave each man getting off the airplane a kiss – whether he was black, white, Hispanic, or whatever he was – and they were crying their eyes out. It was heartbreaking.

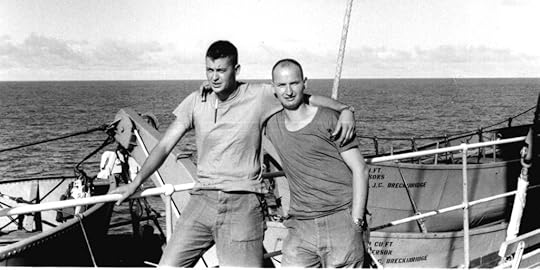

At Oakland men and equipment loaded onto a troop transport ship, the USS J. C. Breckinridge, and departed shore on October 10. John Santini captures the events of the crossing.

Everything was on the ship, our gear, the guns, trucks, everything. I think we stayed in port for a couple days. Then we were off. We went underneath the Golden Gate Bridge, looked up and it was the most beautiful bridge in the world. We went out on the ocean, and the official record says it took 19 days.

On board the ship we had to exercise on the deck until it got too hot. We did target practice with our M-14s out into the ocean to stay familiar with our weapons. And on the ship you had to work, you were given details. But I brown-nosed my way out of them. I would walk around and watch the Navy guys chipping away at the grey paint – chip it … paint it … chip it … paint it. That’s all they did: chip it and paint it.

I remember the good Navy food.

We used to go up on deck at nighttime and watch the waves. It was the scariest thing you’d ever want to see. Here you are a little ship in a gigantic ocean. You wouldn’t see a ship, nothing, for days. There was nothing out there. If that ship would have sank, you’d have died.

Bill Volesky (left) and John Santini aboard the J. C. Breckinridge

Bill Volesky (left) and John Santini aboard the J. C. Breckinridge

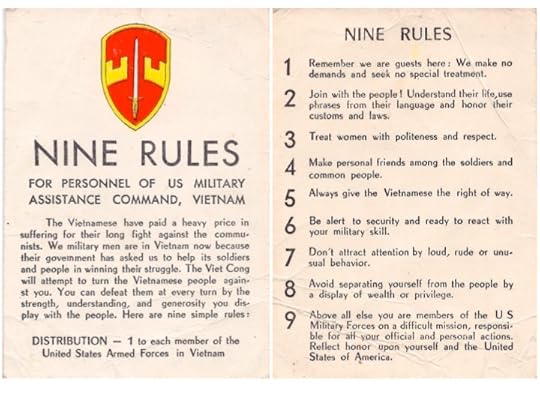

We had classes from Captain Johnson. He had been to Vietnam before and that’s why he was our captain. He was telling us how to stay alive over there, he was telling us about what to expect. We had classes about respecting the Vietnamese. Don’t go out there and fuck everything that walks, their mothers and daughters, don’t do stuff like that. They’re human beings, not sluts and trash. They want you to respect the culture. They want you to go in there and do your job and obey your commands and treat people right. They gave everybody a little card that I kept.

The ship broke down outside Hawaii, and it took two days for the swabbies to get it fixed. We never went into port there, you could see the island in the distance. Then we went on to Okinawa, where we stayed just one day. We were able to get off the ship and tour the city. From there we went to Vietnam.

The J. C. Breckenridge arrived at Cam Ranh Bay on November 3, 1965 but did not immediately touch shore.

We stayed outside port for two days. We were on the deck in our combat gear with live ammunition, still maybe 200 yards from the port. Some of us had the clips locked into our rifles, and they told us to remove them. They said, “As soon as you get on the ground, then put the clip in your gun.”

We left the boat on ramps, loaded the ammunition and equipment on five-ton trucks, and then hooked the guns behind the trucks. On our first day we joined the 101st Airborne Infantry at a rubber plantation off Highway 1 on our way up to Nha Trang. There we set the battery up and stayed for a little while.

First Fire Mission

We’re in Vietnam three weeks and it’s Thanksgiving day. We had our perimeter set up outside Nha Trang airport, we’re in combat mode, and we’re waiting around for orders.

Now everyone is bitching, because here it is Thanksgiving and we’re eating C-rations out of cans. Soon choppers landed and brought us a real Thanksgiving meal. We hardly started when a fire mission came in. A Special Forces unit was in trouble on a nearby mountain, they were pinned down. We started the mission before the sun went down with only a few rounds, but it went on for most of the night. That was our first combat mission, to support the 5th Special Forces on Thanksgiving of 1965.

The 5th Special Forces were the infamous Green Berets. Shortly after the 5th was activated for Vietnam in 1961, President John F. Kennedy personally authorized the distinctive green beret. The 5th SF became known for their unconventional warfare methods and were among the last to leave Vietnam.

The Proud Patch

Straight off the transport ship at Cam Ranh the battalion attached to the 1st Brigade of the 101st Airborne Infantry Division. This meant the battalion acted as a combat arm of the 101st Airborne, and as such its guys wore the Screaming Eagle patch of the 101st.

101st Airborne “Screaming Eagle” Combat Patch

101st Airborne “Screaming Eagle” Combat Patch

During those early months in Vietnam John Santini says there was so much chaos nobody worried about a patch, even if you could find one. Shortly however it became a standard part of the 5th Battalion uniform.

First Gun Crew Accommodations

First Gun Crew Accommodations

In January of 1968 B Battery joined a newly formed taskforce whose nucleus was four rifle companies of the 3/506, a storied 101st airborne infantry battalion known as the Currahees: Cherokee for We Stand Alone. The unit history of Task Force 3-506 calls it “a commander’s dream,” because under its operational control were over two thousand men comprising the full complement of land, sea and air assault forces. TF 3-506 operated out of Phan Thiet with the dual mission to conduct short-notice airmobile deployment into four contiguous provinces, and rapid airborne assault anywhere in Vietnam. Bravo Battery was one of three artillery batteries belonging to TF 3-506. It occupied landing zones north of Phan Thiet, first briefly at LZ Judy during the 1968 TET offensive, and then permanently at LZ Sherry.

For its support of the 3/506 during TET of 1968, under the command of Captain George Moses, B Battery would be awarded the Valorous Unit Award, the second highest decoration that can be given an Army unit and the equivalent of the Silver Star. B Battery was the only unit of the 5th Battalion to win the Valorous Unit Award in Vietnam.

When the 3/506 Currahees departed Phan Thiet in December of 1969 their patch went with them. Today B Battery veterans of those years display the 101st Screaming Eagle on caps, vests, jackets, and anywhere someone is likely to see that proud patch.

* Special thanks to John Santini for his commentary and pictures, and to Jerry Berry for historical background on Task Force 3-506.