Ed Gaydos's Blog, page 4

September 14, 2016

Bob Christenson – The Last Battery Commander – Part Three

After four months as Fire Direction Officer 1st Lt. Christenson again became the battery XO – Executive Officer second in command behind the battery commander.

Race Relations

Our unit was a mix of all races, but I don’t remember any racial tension. The black guys had their area and the white guys had theirs. I think I got along with everyone because I stood up for the enlisted guys and cut the crap where I could, so I was OK with them.

What I basically did was leave enlisted guys alone, both white and black. A lot of being a successful officer was asserting your authority only when you had to assert it. Otherwise leave well enough alone. They were doing their jobs and things were functioning well on the firebase. Rightly or wrongly I saw my job there as keeping all of us alive. I didn’t give a damn about shooting Vietnamese. We had to shoot fire missions on time and on target to protect our guys, but the idea was to keep us all alive and get us out of there. To the extent that I had command authority that’s how I always exercised it. That was my mission.

I know the black guys, the same with white guys, had their hooches and you did not go in there unless you were asked, which was fine with me. Nothing sinister about any of that. People want to be by themselves. They didn’t need an officer barging in there and looking around and giving them an inspection in the middle of the friggin’ Central Highlands. I mean, that’s stupid. Just stupid.

The Fragging

It happened in my hooch, while I was gone on R&R, meant for a second lieutenant who didn’t have a clue to the point that some of the enlisted guys decided he was a danger to all of us. He graduated from college ROTC a second lieutenant, and then took the officer’s basic course for six months at Ft. Sill. He took thirty days leave and then they sent him to Vietnam. So he had never been in the Army. He never would have made it through OCS in a million years. He wanted to be liked, but he couldn’t help himself. He thought he was a hot item and marched around giving the gun crews silly orders.

He was outed early on when one of the gun crews asked him to safety some H & I rounds. He checked the sight picture in the pantel scope, but while doing so one of the gun crew guys held his hand over the top of the instrument, so the aiming stakes were invisible. The lieutenant said “Excellent sight picture,” and they knew they had him. After that the crews basically had their way with him.

One night, one of the crews called him over to a gun and told him they were concerned because the tube ring seemed to be off. Howitzer tubes were made of precision steel, and if you hit one with a small hammer or screwdriver it rang like crystal. Of course, tube ring means nothing, but the lieutenant didn’t know that. They had him running from gun to gun comparing the tube rings while everyone watched. That was the final straw, and he became the laughingstock of the battery. When he discovered that they had made a fool out of him, he doubled down on his alleged authority, but that just made things worse.

When I got back from R&R I walked into my hooch and there was a friggin’ hole in the bottom of my hooch where the sandbags had been blasted out. What the hell is this? Somebody told me we had a rocket attack while I was gone. I didn’t think anything of it. And then I started thinking how come there is a hole way down here? That’s not a rocket. Finally somebody told me this lieutenant got fragged. They rolled the grenade inside the hooch while he was there. Then one of the gun bunnies came up to me and said, “But sir, at least we waited until you were gone.” Shortly thereafter I was told that someone had overheard my argument with the outgoing XO just after I got to Sherry, and that it had gotten around the battery that I stood up for the enlisted guys. At that moment, thinking about that hole in my hooch, it was very nice to be appreciated.

From Seven In A Jeep: A Memoir Of The Vietnam War,

by Ed Gaydos, FDC Section Chief

The lieutenant was shaken but unharmed. The perpetrator was never found, and frankly nobody looked that hard, including Top, although at formation the next morning he delivered an old fashioned, old Army tongue lashing, his face growing more crimson and his language more colorful by the minute.

An uneasy quiet settled on the battery. Captain Joe took the lieutenant off the guns, leaving him minimal responsibilities. The lieutenant spent his days drifting from place to place, avoiding the gun crews entirely, a manufactured smile on his face. He came into the FDC bunker every day and attached himself to Lt. Christenson. The two of them came to our little hooch parties at night, where Christenson was the comic center of attention and the lieutenant was happy to sit and be one of the guys. He eventually left the battery, a lonely, sad figure.

Hunting Big Game

The rats were so pervasive around Sherry that we used to set rat traps with gum in them for bait. But that was kind of boring and the rats always eventually figured it out. So someone had the idea to take a pair of pliers and pull the lead part out of a bullet and cram the casing into a piece of soap, making it a soap-round. You’d chamber a soap-round in your M16, turn out all the lights and put something delectable out there. It only took about five minutes, and pretty soon the rats would start coming out of the sand bag walls. You could shoot and kill the rat without a lead round ricocheting around on the inside of the hooch. That really worked. You got two or three a night. I used to take the dead rats and throw them outside the hooch into the weeds. Finally it got smelling so bad that I had to stop doing that. We kept a chart in the XO hooch to see who was the mightiest rat hunter in the place. Obviously entertainment was at a premium.

Trick of the Trade

Funny, but I remember George Peppard coming to Sherry. I got my picture taken with him. He was a little short guy but for pics he put his arm around your shoulder and boosted himself up so in the picture he always looked like the tallest person there. He told me it was one of the tricks of the trade.

Skunky Beer

One of the things I remember most about Sherry was the skunky beer. Don’t get me wrong, it was better than no beer at all. But we were at the end of the supply chain, so everyone from the ports people to the supply types at Phan Rang and then Phan Thiet got first choice before it came out to the field. And once it got to Sherry I think Top (who controlled the beer) might have siphoned off anything remotely decent. I think we got Budweiser in aluminum cans once, and that was probably by mistake. The rest of the time it was Carlings Black Label in rusty, pre pop-top steel cans. The cans were so old that they looked like they were left over from WW II. You needed a church key to open them up, something that had long since disappeared from life back in the states.

Big Doc and Little Doc

We had two medics at Sherry. Big Doc I think was from Pennsylvania.

Big Doc

Big Doc

Over a period of weeks Big Doc mailed an M-16 home in pieces. I told him he’d get caught, but later he said everything arrived, and he probably still has it today. Nice…they skin-searched everyone coming home but you could mail back a fully automatic M-16 without a problem. I think he even sent back a couple of 20-round magazines.

Big Doc also had a battery powered turntable and one record, by Neil Young and Crazy Horse. He’d play it every night while we drank that warm Black Label. Down by the River and Cowgirl in the Sand became the soundtracks of my time at Sherry. They’re still two of my favorites, and bring back memories of Vietnam every time I hear them.

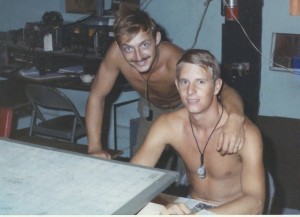

Little Doc Mason was from Ohio.

Christensen (helmeted)

Christensen (helmeted)

and Little Doc Mason in FDC

Because of Little Doc the Ohio state flag flew over the firebase on the Tipsy-25 radar mast, just under the U.S. flag. One afternoon a guy on one of the guns had his leg shattered when he got in the way of the recoil on his howitzer. He was in terrible pain, but Little Doc got him doped up, and we got him out a few hours later on a Medevac “dust off” flight. I think most of Little Doc’s other business was dispensing penicillin to take care of whatever diseases some of the guys caught during their regular trips to Phan Thiet and the whore hootch outside our wire.

Two Close Calls

The first close call happened at night during another Medevac dust off. All our lights were out, including the lights on the radar tower. I was on the radio guiding the pilot in. As he was on final approach I realized I hadn’t told him about the tower and the guywires holding it up. Of course, his lights were also off. He got in anyway, to my incredible relief. Those dust off pilots were fabulous.

Then about midway through my tour I was calling in defensive fire on our position from Betty. These were pre-planned targets we would shoot in case we were overrun. I was walking it in as close as I could. I was in one of the guard towers on the perimeter, and for some reason I think Jim Jenkins was there with me. Normally, we ducked down behind the sandbags when the rounds came in, but on this occasion I was up watching the explosions. I was leaning up against one of the six-by-six posts that held up the roof, and a piece of shrapnel zinged into it right above my head. You remember the zinging noise shrapnel made as it flew through the air? A couple inches lower and it would have been curtains. I never did that again.

Lt. Christenson indicating LZ Sherry on the map with his combat pointer. Note the overlapping firing fans from LZ Betty to the southwest and LZ Sandy to the northeast.

Lt. Christenson indicating LZ Sherry on the map with his combat pointer. Note the overlapping firing fans from LZ Betty to the southwest and LZ Sandy to the northeast. Shrapnel – four inches long and razor sharp

Shrapnel – four inches long and razor sharp

The Long Lanyard

Someone in Phan Rang got the bright idea that they wanted to find out if a time fuse actually had a built in two second delay, so if you set it on zero and shot it, it would still not go off for two seconds. They decided we were going to be the guinea pigs to find out. I think we all thought that this was a pretty hair-brained experiment, but we did it anyway. We made an extra-long lanyard, so whoever was shooting the gun could be behind the parapet in case the thing did go off right out of the tube. We told everyone in the battery to get down and behind something. Unfortunately, I believe I was the one who ended up pancaked behind the parapet and actually pulled the extra-long lanyard. Happily for me, we found that there was in fact a two-second delay, which of course was built in to keep someone like me from blowing himself up if he was ignorant enough or careless enough to shoot a time fuse set to zero. What were we thinking?

September 7, 2016

Bob Christenson – The Last Battery Commander – Part Two

The Artist Within

Memories of 1st. Lt. Christenson by Ed Gaydos, FDC Section Chief

From Seven In A Jeep: A Memoir Of The Vietnam War

From the beginning I liked this new lieutenant with the Tom Sawyer smile. His first order of business was to decorate his room in the FDC bunker where the officer in charge slept. On one wall he drew a caricature of Vice President Spiro Agnew wearing a hard hat with two American flags sticking from it. On another wall he created a perfect rendering of Mr. Zig Zag, the bearded figure on roll-your-own cigarette papers and patron saint of potheads. The lieutenant hung out with the enlisted men, and was often the only officer at our evening hooch parties, a frat brother as much as an officer. He and Captain Joe were the best officers I served under in Vietnam.

Spiro and Mr. Zig Zag

Spiro and Mr. Zig ZagFlanking a short timer chart

Shortly after my initial disagreement with the departing XO over FADAC, I began my career at Sherry as the Fire Direction Officer. In the beginning I really didn’t know what I was doing. I was trying to learn the ropes, and had some time on my hands I guess. I never had any artistic talent in my life at all: zero. Whatever it was, the pressure, the change of scenery, whatever it was, all of a sudden I could draw stuff. I discovered I could do it. It’s like these people who are in traumatic situations and something in them changes. I figured the place needed some decorating so I drew those pictures on the walls. I think I probably found a pack of Zig Zag papers (they were all over the place because some of the country boys liked to roll their own) and did the Zig Zag guy. Spiro Agnew I just drew from memory, which was crazy. I don’t know how I was able to do that.

And I’ve never been able to draw since.

It was the stress. Totally stress. I used to have hallucinations, not drug induced, but I would have out-of-body stuff, floating around seeing myself. Yeah. Three or four times pretty much the whole time I was there, which I never experienced before and never experienced after I got back to the states. I think it was being thrown into that crazy atmosphere. The artistic talent and all the weirdness was all stress related. It had to be. Very strange.

A Crazy Night in Paradise

The First Sergeant and I were never friends, and we hardly ever talked. It was Top’s firebase and everybody knew it. He had no use for lieutenants, especially those who were obviously not lifers. But we never had any real issues. I had very few conversations with him. Probably the longest conversation I had with him was when he chased one of our officers with a flare threatening to shove it up his ass.

It happened one night after this officer went into Top’s hootch when he was off drinking somewhere and took his fan. There was some VIP spending the night, which as you know was a real rarity. No one over the rank of captain EVER spent the night at Sherry. This officer took Top’s fan out of his hooch so the VIP could be comfortable.

Top came back to his hooch drunk as a motor scooter and went to bed not knowing the fan was gone. In the heat of the night he pissed himself, woke up, realized his fan was gone and went nuts. I am not making this up. He somehow found out who had taken his fan and went after him with a hand flare.

It was two or three in the morning. I remember being in FDC and hearing the commotion and running outside and seeing five or six guys standing around watching Top chase this guy around with the flare. Top was circling him with wet skivvies and bulging red eyes, and had one of those popper flares in his hands, growling that he was going to ram that flare up his ass and touch it off. He had taken the top off the flare and put it on the bottom so all he needed to do was smack it to make it go off. At the time, it seemed like a real possibility. The officer was dancing around as Top circled him, making sure that his butt was out of reach.

People were afraid, because Top looked like he meant it. Finally the guy got far enough away and someone, I think it was the Chief of Smoke, grabbed Top and calmed him down and got his fan back. Fans were like gold over there.

Of course this was another thing that never got reported to Phan Rang, and to me it was very uncharacteristic of Top. He was such a soldier that he would never go after an officer. He knew he was wrong, and he backed down. But it wasn’t the sort of thing you could ever remind him of again.

When it happened, I was afraid Top was actually going to do it, but with the passage of time the scene is so funny I get tears from laughing so hard. Just another crazy night in paradise.

Deadly Trash

One night we received an illumination mission, and when we plotted the trash coordinates on our charts it matched up with the location of a small village.

After an illumination round pops in the air the heavy steel canister continues along its trajectory, making it necessary to know where “the trash” is going to land.

We, or at least I, cleared the mission through a US contact, but that contact also cleared through an ARVN source, and in this case the ARVNs said go ahead and fire because the village wasn’t really there. “ARVN” stood for Army of the Republic of South Vietnam, our so-called allies.

As you may recall we, or at least I, had a strong distrust of the ARVNs: it seemed like we always got hit after an ARVN unit went by. I think they dropped off equipment and ammunition for the VC. I know they were dropping off drugs at the firebase. I recall one of our E-7 sergeants coming to me when I was battery commander telling me that he had spotted an ARVN officer outside the wire acting strange. I sent the sergeant out there, and he came back with a cube made up of about seventy small plastic boxes each filled with heroin. The ARVN officer had dropped it in the weeds to be picked up by one of the pushers on the firebase.

Anyway, I cleared the illumination mission several times, telling our US contact that our charts showed we were going to drop the empty canisters on a village. He said to go ahead and fire the mission anyway. I had a very bad feeling about this and got the guy’s initials, along with the initials of his Vietnamese counterpart. We weren’t on a secure radio network, so I could not get full names. I figured it would be me they would be looking for if we shot the mission without absolute protection.

We shot the mission, and sure enough about a week later we got an ominous radio call that we had wrecked a village with our trash and a number of people had been killed. The ARVNs wanted a full investigation, and I think, were trying to shift the blame to us for the mistake. But we had the initials and time of clearance and the whole story. After we explained what had happened and given our information to the US contact, the whole thing went away without another word. I think we dodged a major bullet. If we hadn’t gone the extra mile to verify identification information, a bunch of us, probably me, would have been toast.

The All Important Hats

One night we were playing cards in the FDC – I recall it well because someone, I think it might have been Ed Gaydos, who always had a dry sense of humor, casually tossed off, “Sir, is that a scorpion crawling up your leg?” Damn straight it was. I jumped up, brushed the thing off, and stomped it. We had just dealt again when we heard some distant pops, and a round went entirely over the battery, and then a second and third round hit inside the wire somewhere.

I grabbed my steel pot, ran out the door and saw a round on the way in. It was streaming sparks so you could see the flat trajectory and where it was coming from. I ran back in and yelled that it looked like rockets coming from around 5600 (metric direction corresponding to northwest). As I recall we usually blamed any incoming on that unfortunate direction, and then ran out again and headed to the perimeter where the fire was coming from. We were always concerned about a ground attack coming in while we were taking fire. From the FDC, that meant running across the broad, empty and exposed part of the firebase where we used to play baseball, to get to the guard tower on the berm.

While I was gone a call came into FDC for an officer to safety check the settings on Gun 3 on the northern perimeter near where I had just arrived. They could not find me, but were able to get a new second lieutenant named McDaniel who had been at Sherry for a few months. Just as he arrived at Gun 3 the VC fired another round. I saw it coming so I hit the dirt out there between the perimeter and the gun. The round went right over me and exploded about sixty feet away in the Gun 3 parapet, and I figured a bunch of people must have been hurt or killed. Funny, but I don’t remember much about that night afterward, except McDaniel bleeding in FDC with a few small pieces of shrapnel in his arm. I do recall the brass coming in to pin purple hearts on people a few days later and complaining to me that some of the guys, including me, weren’t wearing hats per protocol. Typical.

Four men were wounded on Gun 3 that night, none fatally. It turned out the attackers had used a recoilless rifle, probably left behind by the ARVNs who had been in the area the day before. Two rounds hit the ammo bunker, one going clear through without detonating and the other hitting outside the door and igniting powder charges in the doorway.

Gun 3 ammo bunker

Gun 3 ammo bunker

Fun With Flares

I remember Bill Cooper, although I never knew him that well. On New Years Eve, after we had a few drinks, Cooper went out and caused all sorts of problems when he got on the berm and blew off a red flare. Red flares meant that someone had spotted VC in the wire, and that gun tubes would be lowered to shoot beehive rounds and direct fire. Beehive rounds were like giant shotgun shells fired from a howitzer, literally flattening everything in front of the gun. Within seconds the whole firebase opened up. One of the guns fired beehive in the direction of the flare, which basically cleared all of the wire in front of it. Then someone fired off a couple claymores, and then the phu gas went off on that side of the firebase (C4 plastic explosive in a fifty-five gallon drum of Napalm, positioned in the ground on an angle toward the enemy). All this was happening with the howitzers firing defensive rounds, the Quad-50s and Dusters banging away, and tracers flying everywhere. The sound was deafening and no one knew what was going on except that the red flare alert had gone up and we were under ground attack.

About thirty seconds later Cooper came running back into FDC saying, “Wait, wait, wait.” He claimed the flare was an accident, but I don’t know how you shoot one of those things by accident. And then everyone realized it was all a big mistake. That was dangerous. Who knows who could have been out in front of those howitzers when they went off with beehive? When something like that happens you shoot first and ask questions later. I mean, Geez.

1st lieutenant Bill Cooper, Executive Officer (XO) at the time, did not make a mistake. He intentionally fired off the flare to test the readiness of the firebase, but without telling anyone of his intention. Realizing immediately the gravity of his action he claimed he had made a mistake in order to avoid disciplinary action. Today he freely admits it was not the wisest decision.

Everyone in Vietnam did things they wish they hadn’t, including Bob Christenson.

I don’t know what we were doing or why we were doing it, but I had a white flare in the middle of the battery and I was going to shoot it off. Remember on the north side of the battery there was a small shed out by itself with explosive ordnance in it. I have this flare and I went to shoot it off, popped it off banging on the bottom, and I dropped it. The thing shoots along the ground right for this goddam shed, right for the door which was open. And I am looking at it and thinking: Holy shit! It’s going to blow everything! How am I going to explain it when this shed goes up? It missed by a few feet and died out in the grass. That’s between you and me. I don’t think I ever told anybody about it till now, it was too embarrassing.

But it wasn’t the worst mistake I made at Sherry. One quiet Sunday afternoon I had to test fire a howitzer which had received a new tube. I cleared the target grid, set the quadrant and deflection, loaded a round of HE high explosive, and fired. A millisecond later I realized I had fired a charge 7 rather than a charge 1, and the tube was pointing directly at Phan Thiet. I’ll never forget that feeling; I could picture a round of HE suddenly landing in the middle of Phan Thiet. I ran back to the FDC and checked the charts. It turned out that the charge and quadrant were just enough to get the round over Phan Thiet and out into the South China sea. A bunch of fishermen probably got the scare of their lives, and so did I.

August 31, 2016

Bob Christenson – The Last Battery Commander – Part One

1st Lieutenant Bob Christenson

1st Lieutenant Bob Christenson

LZ Sherry 7/70 – 6/71

The Highest Lowest

I graduated from Officer Candidate School a 2nd lieutenant in 1969. My first assignment was at Ft. Sill in a Pershing Missile training battery. As a training officer I taught M60 machine gun, M79 grenade launcher, M72 LAW (light anti-tank weapon, shoulder fired) – all that fun stuff.

When I got orders for Vietnam I had no tube artillery experience at all. So I signed up for a gunnery refresher course at Ft. Still. Before I could begin training the battery commander called me in said, “How come the only lieutenant in our whole battalion who is not a member of the AUSA wants to take this course?” (The Association of the United States Army is its professional association.)

I said, “I understand.” So I sent my $25 into the AUSA and got my gunnery course.

I was made a 1st lieutenant on my one year anniversary of graduating from OCS, which would have been in July of 1970, the same month I arrived in Vietnam

When I got to Vietnam I was assigned to First Field Force artillery in Phan Rang, and of course the question then was where you were going from there. At that point I still had not figured out all this artillery stuff. I was terrible at math, my worst subject ever. But they had a gunnery course in Phan Rang, about a week long, for all the new lieutenants plus the fire direction enlisted guys.

A funny story. So I took this course, and I’m a quietly competitive guy, and said to myself: I’m going to get the high grade. You got a Zippo lighter with your name, the battalion crest and High Scorer in Class engraved on it. The night before the test I took all the guys out and got them roaring drunk. And I got roaring drunk too, but I knew that I could function drunk and I didn’t think they could. And I was right. I got the highest score on the test, which I was told was the lowest highest score in the history of the course. I just remember the gunnery instructor shaking his head at all of us during the test – our breaths must have smelt awful. I got my lighter.

They sent me up to Dalat to meet Colonel Richard Tuck, the Prov Group commander, because being the academician that he was, he wanted the guy who had the highest score. I don’t think he knew it was the lowest ever.

I couldn’t believe the place existed…after a Huey ride from the heat in Phan Rang, Dalat was cool, lush and totally un-Vietnamese. It didn’t even smell like a Vietnamese city. It was the Eurasian half French and half Vietnamese girls that caught my eye. Some of them were stunners, dressed to the teeth just walking around. There were great French restaurants. And the first thing I was told when I got there was don’t worry about the VC because this place is off limits for both sides in the war.

Colonel Tuck had been a French professor at West Point, but as an artillery officer he had somehow been sent to Vietnam to get combat experience on his resume. He made Dalat his headquarters because it was so French and had the great restaurants. He was a great guy, very classical almost 19th century in his approach. But he cared deeply about his men. I remember when I first met him he had someone take a black and white polaroid picture of the two of us. I think he did that with all of his officers so he could remember them. He sent me a copy afterwards. He spoke in what sounded to my untrained Midwestern ear as an upper crust, up-Eastern accent. I never met anyone else like him in the Army. He had this strange refined existence in the middle of a war in a beautiful mountain city that seemed totally oblivious to the destruction raging around it. He never married. I exchanged Christmas cards with him for years afterward, until his death in 2002.

Colonel Tuck assigned me to the 5th of the 27th Artillery, and specifically to B Battery at LZ Sherry. At the time I knew nothing of Sherry or its history. I rarely saw Colonel Tuck after he assigned me to Sherry, but after my first six months in the field he called to tell me that he could get me posted to a general’s staff in the Philippines for the rest of my tour. I eventually turned him down because for some weird reason I felt like I had to stay in the field to get my year in Nam behind me. I felt like leaving before my time was up would be a cop-out.

1st Lt. Christenson and Col. Tuck

1st Lt. Christenson and Col. TuckColonel Richard Cabell Tuck, a direct descendent of Patrick Henry and graduate of West Point, was an assistant professor in the French Department at West Point for three years. Colonel Tuck was a graduate of the Armed Forces Staff College and the Ecole Superieure de Guerre, Paris (the French War College). He served in the Korean and Vietnam conflicts, and in command and staff positions in Europe and the Pentagon. He holds the Legion of Merit, the Bronze Star and nine Air Medals.

A Rude Introduction

The trip down to Sherry was a rather eventful day unfortunately. I had just gotten to LZ Betty at Phan Thiet, at Alpha battery, and I was sitting there eating lunch with a bunch of other people when there was a loud shot. Somebody had killed himself in the chow line right outside the door. Some guy took his rifle and put it to his head and pulled the trigger. I thought: Holy shit what in the world is going on here? That was my introduction to the field

Later that night Sherry got hit and I watched, and heard, the whole firebase open up in response. The next morning I was there.

How He Earned His Chops

I came into Sherry as the XO. Within a week or two after I got to the battery I got into a shoving match with the XO I was replacing because I had countermanded an order he had given to run the FADAC artillery computer eight hours a day. This thing was the size of a small car, and was placed inside the confined space of the fire direction center. It sounded like a loud vacuum cleaner with issues, You could go deaf listening to that thing and it was driving everyone in the Fire Direction Center nuts. Headquarters told us to run it to keep it dry in the Vietnam humidity, but we never used it for actual fire missions.

I remember going into the FDC, and it was Charlie and Jenkins and maybe Paul, and these guys were not exactly shy about speaking to officers. I came in and said, “If you guys could change anything what would you change?”

The first thing they said was to get rid of FADAC.

Charlie Snider and Paul Stagg in FDC

Charlie Snider and Paul Stagg in FDC

J

im Jenkins with his perpetual toothpick

J

im Jenkins with his perpetual toothpick

I said, “You’re right. Absolutely.” My feelings about orders from headquarters was: What the hell, they’re not here. I’m here, my ass is here, and I’m going to do what I think is necessary under the circumstances.

So I turned off the FADAC, and that’s when the old XO got on me. He was kind of tight assed. I recall he wanted to be a lifer, or at least acted like it. We had had a few beers and I told him: Fuck you basically, we’re not going to do that. And we bumped a little bit, and that was it.

I didn’t know it, but one of the enlisted guys – it might have been Paul – overheard our conversation when I told the lieutenant to take his FADAC and REMF orders and shove them, and saw the pushing. So I guess I became a champion of the enlisted guys early on, but didn’t know it until someone told me about it later. And that’s how I got my chops with the guys.

August 24, 2016

Joseph DeFrancisco – Battery Commander – Part Eight

The Power of Service

I previously mentioned that I commanded the 7th Infantry Division Artillery at Fort Ord, California. While there, 1988-89, there was a junior enlisted guy down in B Battery, 6th Battalion, 8th Artillery Regiment – there must be something about Bravo Battery – who recently contacted me. He has organized reunions of the people in that battery. Because I was the division artillery commander he includes me as an honorary member. He’s going through all this trouble to organize reunions, based on two years of service twenty-eight years ago.

The letters I get from him to his fellow soldiers! He keeps saying it was one of the most fulfilling periods of his life. But this is not something unique or unusual in the men and women who have served in the military.

My father passed away at the age of ninety-two. He knew he was going to die and my two brothers and I had lots of talks with him. We asked him, “Besides your name what do you want to put on your tombstone?”

He told us:

Mario J. DeFrancisco

Second Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Corp

1944 to 1945

He lived to be ninety-two years old, and what’s the only thing he wants on his tombstone? The two years he spent serving his country.

It’s an amazing thing. Go into any local cemetery and look at what’s engraved on the tombstones of people who served, WWII especially, but also WWI, Korea and Vietnam as well. Just look at what’s engraved on those tombstones. You will see Private First Class, U.S. Army – Petty Officer First Class, U.S. Navy – Seaman, U.S. Coast Guard – Captain, U.S. Army Air Corps. It could have been just a little sliver of their lives, but it was a defining moment for them.

It’s the power of service. You’re serving others, something larger than yourself. It was a feeling that came across strong and clear from the great soldiers of LZ Sherry. They would rather have been at home, but they did their duty, had pride in their unit and themselves and took care of one another. It was a great place to soldier. It is not surprising that so many have responded to Ed’s call to share information and thoughts from so long ago on that small island of America so far from home.

August 17, 2016

Joseph DeFrancisco – Battery Commander – Part Seven

Lt. Gen. Joseph DeFrancisco, USA, Ret.

Army Associations

Army Historical Foundation – Board Member

Association of the United States Army (AUSA) – Senior Executive Associate and former President of the George Washington Chapter

West Point – Served on the transition team for four successive Superintendents, leading the last two transitions

Association of West Point Graduates – Board Member, Chair of several committees

West Point Society of Washington, DC – former President for seven years

Army Distaff Foundation – Board Member

Army Aviation Association of America – Senior Executive Associate

Army-Air Force Mutual Aid Association (now American Armed Forces Mutual Aid Association) – Board Member

National Defense Industrial Association – former Board Member

USO – former Board Member

Civilian Aide to the Secretary of the Army for four Secretaries

Personal

Son Eric graduated from West Point in 1989

Daughter Laura has worked at the Pentagon as civilian employee of the Army since college, and is now a student at the National War College in Washington

Married to Lynne since 1965

In 2013 named a Distinguished Graduate of West Point

Employment

Lockheed Martin

Honeywell

Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) – today Leidos

Private Consultant

The Army Since Vietnam

The Army has changed dramatically over the course of my thirty-four years of active duty and subsequent involvement with Army related organizations.

An Army In Crisis

I’ve already talked about the shock at what I found in Germany on my first assignment out of West Point: low troop morale and preparedness, poor to nonexistent leadership, and denuded officer ranks. It was not until I went to Vietnam with the 1st Cav that I found some really good units and good officers.

Then after my first Vietnam tour I went to Ft. Sill as a training battery commander and encountered many of the same problems I saw in Germany, only this time marked by the larger societal problems of racial tension and drug use.

Then at LZ Sherry it looked like things had turned around again. Sherry was totally different. I think the world of the people there, the quality of their training, the quality of their character.

To this point in my career I experienced the men in the field in Vietnam to be more than just skilled, they were dedicated to their jobs and proud of the work they did, even though a lot of them would have chosen to be somewhere else. The same goes for the young officers and NCOs. Among the older career officers and sergeants the picture was mixed. Many were excellent, and many were not up to the task, because they were poorly selected for their jobs, poorly trained, or poorly led during their early years in uniform.

Right after my second Vietnam tour, which included time at Sherry, I went to graduate school. Understand that during this two year program I am not really “in” the Army. I’m just reading about things and watching TV news. It was not until I got to Command and General Staff College at Ft. Leavenworth in 1973, eight years into my active duty career, that I had a chance to know a large group of other officers and see another side of the Army.

At Leavenworth I came to realize how disastrous the aftermath of Vietnam was for the Army as an institution. There was a real crisis in confidence in the Army itself of itself, and in the American people about the Army. There was the Calley affair and controversy over body counts. There was controversy over careerism and the integrity of senior leaders. Many said officers did not care about anything but their own careers and would do anything to enhance their careers.

It was so much a crisis that the Army Chief of Staff, who was now General Abrams, convened special panels at Leavenworth to talk to us. We were the Army’s up and coming mid-grade officers, senior captains and majors. This group was nearly in revolt over the quality of leadership in the Army. Add in Watergate (1972) around that time, which also eroded confidence in our political leadership. Add in race riots in our major cities. With all this turmoil in the country and in the Army it was a real low point.

The Rebuilding Years

The following year Nixon ended the draft, just before his resignation, so now there is no more forced conscription. General Abrams decides that without a draft we are not going to war again without the reserve component. He believed part of the problem with Vietnam was that the American people were not with us, we did not have the reserve component involved. We had draftees and volunteers, but not the reserve component. He saw this as one of the reasons for the split between the Army and the people we were serving.

So you had a number of things happening at once. The end of the draft and beginning of the all volunteer Army, and you had the Army Chief taking a large portion of combat service support out of the active force and putting it in the Army Reserves and the National Guard. So now it would be impossible to deploy and impossible to fight again without the reserve components, and consequently without the involvement of communities across the nation.

Slowly, very slowly, we start to come out of this low period. It is turned around because of a bunch of lieutenant colonels, colonels and young generals who are determined to make the Army into a professional force again. There was a great emphasis on the all volunteer Army bringing in good people and a re-emphasis on training.

In Vietnam we lost our ability to do anything except fight in Vietnam, and toward the end we lost that ability too. There was a great drive toward enhanced training. It was at this time that the foundation was laid for what is today our network of Combat Training Centers. The National Combat Training Center at Ft. Irwin in California was the first. Today there is a light combat training center at Ft. Polk, LA, a center in Germany and another centered at Ft. Leavenworth designed to train senior staffs and commanders. So now we’ve got four .

The training center at Fort Irwin, California, trains primarily mechanized brigade level combat teams. The Joint Readiness Training Center at Fort Polk, Louisiana, trains infantry brigade level teams. The Joint Multi-National Readiness Center at Hohenfels, Germany trains all brigade combat teams assigned to Europe. The Battle Command Training Program at Fort Leavenworth prepares leaders for corps, division, and brigade command.

All these training centers feature exercises in the field against a skilled opposing force that uses the enemy’s tactics, techniques and procedures.

Then the Army developed training focused on sergeants, called the Non-Commissioned Officer Education System (NCOES). Remember in Vietnam I told you we were making captains in two years. We were making NCOs in a very short period of time as well, Shake and Bakes we used to call them. You’d come out of school an NCO without any of the background and experience you needed. We developed the NCOES program that said, If you want to get promoted you’ve got to meet these certain criteria and go to these certain leadership schools.

These schools teach leadership and technical skills at four levels: primary, basic, advanced and senior.

This system did a great service to the re-professionalization of the NCO corps. We sent officers to senior courses, so we said to our senior sergeants, You have to go too if you want to become a sergeant major.

Sergeant Major holds the rank of E-9.They serve as either staff Sergeants Major or Command Sergeants Major (CSM). A CSM supports commanders from battalion to four star general, including the Army Chief of Staff whose CSM is called the Sergeant Major of the Army. CSM positions are now highly competitive. Regardless of the level at which they serve they all hold the rank of E-9, but prestige and amenities differ according to position.

By the time I became a battalion commander in 1981 senior officers were centrally selected by a board. I think central selection began in about 1977. Up until that time you had to get to yourself into the right position so that an individual senior commander would pick you to be a battalion commander or even higher. The Army said, No more of this stuff. If we want the best we have to have a rigorous selection system. We are going to have a board and we are going to look at the files of all the people eligible and we’re going to centrally pick the best. That process applied to battalion up to brigade commanders. I believe we also select sergeant majors centrally now. I know there is a board for command sergeant major.

The end result of all this is the re-professionalization of the Army – not only in training, but also regarding professional demeanor and character. For example, there was a drive to de-glamorize the drinking of alcohol. When I first came into active service in 1965 all the way up until after Vietnam, you’d have almost mandatory happy hours in the officers clubs. It was a big deal to say you got drunk. I cannot drink enough to get drunk, because I tend to get sick first, which is probably a blessing. But you had people thriving on drinking and bragging about being drunk. I remember the unapologetic alcoholics I served with in Germany, superior officers and sergeants both, and how awful it was. All that ended in the early 80s. We had a parsimonious guy become Army Chief of Staff, General John Wickham who took the show girls out of the clubs and corrected all sorts of unsavory things like that. He did a lot of good for the Army.

So there was this great drive toward professionalism in the 70s and 80s, with very rigorous training, tighter selection of officers and senior sergeants, and an elevation of the professional environment of the Army. I was certainly the beneficiary of this new environment. I went through three Command Training Center rotations as a Battalion Commander, as a Brigade Commander and then as a Division Commander. And without the central selection of senior officers, I may not have been considered at all for the senior positions I was privileged to hold.

During the Reagan years in the 80’s we had a plus-up in military budgets and got all this new equipment, which by and large we still have today because of funding constraints. That plus-up also fueled our new training programs, which we also still have today.

The Payoff

The culmination of this new higher level of professionalism took place during Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

Operation Desert Shield, August of 1990, was the operational name for the buildup of U.S. forces for defense of Saudi Arabia following Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. Desert Storm, January of 1991, was its combat phase.

I had just returned to the Pentagon as executive officer to the Secretary of the Army, Michael Stone. The forces we put into the field were the result of all the great battalion and brigade commanders from Vietnam who had stayed on active duty and who had worked to revitalize the Army over the prior fifteen years. We wiped out the Iraqi army in a hundred hours. We did that because of the high level of training instilled in all those units. We had practiced fighting the Russians to a fare thee well, and unlucky for us the Iraqis they were using Russian tactics and a lot of Russian equipment. They never had a chance.

We continued this training and elevation of the Army after Desert Storm. Twelve years later we got involved in Iraq with a professional, all volunteer force. When we were called upon to do what we were trained for, which was the initial invasion, everything went great. But then … but then … when that conventional war turned into a counter insurgency, we were not ready for it psychologically or training wise.

Today

So where are we now? We have a highly trained Army, a highly disciplined Army with great soldiers. Still I am not one of these guys who says this is the greatest Army we’ve ever fielded. No, I think at their best the troops in Vietnam were as good as anybody we ever had.

In that Army, due in large part to the draft, we had a mixture of talent we do not have any more. Today in the all volunteer Army you don’t have the guys in numbers like we used to have: ambitious guys with the ability to do lots of things, who come with varied backgrounds from around the country, who have lots of talent, are very smart, and who are every bit as dedicated and patriotic as anybody we have today. I may be an outlier in this opinion. Of course by now I’m an old guy; I’m not one of the young guys anymore.

I look back on those troops I was with on my first tour with the 1st Cav, what those troops did in battles like Ia Drang Valley; what troops of the 101st Airborne did at Dak To and Hamburger Hill. I look back on my second tour commanding Bravo Battery at LZ Sherry. Those were among the finest field soldiers I saw during my career. And toward the end of the long war in Viet Nam they suffered the ravages of poor leadership – based on too rapid expansion of the Army, too rapid promotion at the unit levels, and careerism and politically motivated actions at more senior levels – and maybe even worse, the erosion of support from the American people. How did guys in the field maintain a level of commitment when the people back home didn’t believe in what they were doing, calling them murders and worse? Somehow they did until a combination of social conditions (war protests, drug culture and racism) and the loss of national commitment became overwhelming.

The bottom line is yes, we have a great Army now, but I take nothing away from the troops I was with in the 1st Cav and my B Battery troops at Sherry.

Below is a link to a five minute interview with Lt. Gen. Joseph E. De Francisco (Ret.) on Retaining Talent in the Army. Released April 3, 2015. In it he draws lessons from his own career, and most notably to his decision to stay in the Army following his command of LZ Sherry.

Highlight the entire link, right click, choose ‘open link in new window’

August 10, 2016

Joseph DeFrancisco – Battery Commander – Part Six

A Dream Fulfilled

Again the Army was good to its word in sending me to graduate school right out of Vietnam. I went to Rice University in Houston, a very good small school noted for engineering, but I went there for military history. Rice was one of the schools West Point used to train history instructors, all based on the presence of Dr. Frank Vandiver, one of the nation’s top military historians of the day and then Provost of the University. So I went there to study under him. I just had a marvelous time.

It was a two year masters program and I met lifelong friends in the program. There were five of us Army guys, all just out of Vietnam and all with two tours. There were two infantryman, two armor officers and me, a field artilleryman – we were all studying various phases of military history.

Dr. Vandiver was in the process of writing a biography of General John J. Pershing (commanded American forces during WWI). We each wrote a thesis on some aspect of Pershing’s career. My grades at West Point were not all that good except for history, but I won a prize for my masters thesis, which was a great source of pride for me.

From Rice I went to Ft. Leavenworth for the Army Command and General Staff College for a year.

The United States Army Command and General Staff College develops leaders for full spectrum joint, interagency and multinational operations. It serves as the first of the leadership programs leading to senior command.

From there I went directly to West Point to teach military history in 1974. I taught a seventy-five minute course twice a day, six days a week to seniors … and it was a blast. I taught a lot on the Civil War, the two World Wars, some on Korea, a big block on Napoleon, and what we called the “Great Captains” before Napoleon: Alexander the Great, Caesar and Hannibal.

When I said I had to go prepare for class, my wife Lynne would say, “No, you’re just going to read that stuff you love. You’re not working, you’re having fun.”

It was very fulfilling and very rewarding. I taught at West Point for three years and then spent a year in the Office of the Dean. After four years at West Point I was ready to move on.

Rapid Fire Promotions

One of the beauties of the Army is you get to do a lot of different things.

I had been promoted to major the year I went to West Point. In order to progress you had to have “troop duty as a major,” and I was running out of time. I was fortunate that on my next assignment in Germany I had three echelons of command in a three year period. First I was on an artillery brigade staff, and then I went to a battalion as XO (executive officer second in command), and then I served on the VII Corps Artillery staff. (The entire VII Corps deactivated after Desert Storm). As a result, out of Germany I went to Ft. Lewis, Washington where I commanded an artillery battalion, which was another intermediate goal of mine and another great assignment.

From there I went to the Army War College at Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania, which is another one of those important steps you have to take in order to progress.

From there I went to the Pentagon as Chief of Army War Plans, then to another job in the area of strategy and policy, whose title had a string of letters too complicated to describe. These were wonderful jobs and a great two years at the Pentagon. During this time I got promoted to full colonel.

From Teaching History To Making It

Joseph DeFrancisco now becomes a high level participant in the major military events of his time.

Panama

I left the Pentagon in 1988 and went to Ft. Ord, California to take command of the 7th Infantry Division Artillery. At the time the 7th Infantry Division was the Army’s only light infantry division. My division artillery had three direct support battalions, and one general support battalion.

It was during that time that Operation Just Cause occurred just before Christmas of 1989. The U.S. essentially invaded Panama to capture the strongman dictator Noriega and put him in jail.

Noriega did not have a real Army, he had a bunch of thugs. These were not pitched battles. Still the US suffered 23 killed and 325 wounded. As I recall we lost the better part of a Navy Seal unit that was killed trying to capture Noriega. They just landed at the wrong place at the wrong time. As far as artillery is concerned, we used artillery more for intimidation than for indirect fire. We fired on checkpoints; we fired illumination; we also direct-fired into a couple buildings to entice the occupants to surrender, which they did.

It was a wonderful operation that took only a couple of months. Operation Just Cause was the first time in my experience that the U.S. military did a lot of things right: a multi-service, multi-unit operation that included airborne, mechanized and light infantry, Air Force and Army helicopters all brought together from different places in the U.S. to converge on Panama at the same time.

The real value of artillery during that operation was fire support coordination, which was more of an asset than actual firepower. As usual our artillery guys – our forward observers, our recon NCOs and specialists (MOS 13 F) – had a better communications link than the infantry. We called in the vast majority of the Army helicopter air strikes because our artillery guys knew how to do it and had the connectivity. The Panamanians, the bad guys, did have mortars so we had counter mortar radar, upgraded versions of what we had at Sherry and very effective. The outstanding thing was that everything worked when we got in there. We did the job quickly and we got out quickly.

In addition some of my battalion commanders took on non-artillery roles in what we call non-standard missions, such as force protection of installations and running convoys. This was nothing new to artillerymen, who are versatile, smart guys. They did a great job on non-standard missions in addition to the artillery fire support. It was no different in Vietnam, and would be the same in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Return To The Pentagon

Right after Panama I was selected in late 1991 to be XO to the Secretary of the Army, another stepping stone job and highly competitive. As it turns out my commander in the 7th Division had that job when he was a colonel and he recommended me for it. That’s how my name got funneled up. I had to go for an interview, was fortunate to be selected, and subsequently received my first star (promotion to brigadier general).

The Secretary of the Army is the highest ranking person in the Army, the top guy in command, even senior to the Army Chief of Staff (the highest uniformed officer in the Army). He’s a civilian political appointee, who has to be nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

The Army Secretary at that time was Michael Stone, a wonderful person, a successful businessman, and a very wealthy guy. He decided he wanted to give something back to the country that had given so much to him. So he went into government service. He became one of our top officials in Egypt as the representative for the Agency for International Development, a job he held for a number of years. Then he came to the Army where he held a number of Assistant to the Secretary of the Army positions. He was ASA for financial management; then Under Secretary of the Army, and finally became the Secretary under President George H. Busch.

Mr. Stone was Army Secretary for the whole First Bush administration, meaning he was there for Desert Shield and Desert Storm. In fact I went to work for him the day before Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. So I did not participate on the ground, but I participated seven days a week out of the Pentagon. I spent two years as his XO, another wonderful job that was supposed to be for a year, but Secretary Stone asked me to stay another year. I say, “He asked me.” But when the Secretary of the Army asks you to stay another year there is really on one answer.

Half The Battle Is Knowing What You Want

The Other Half Is Sticking To It

After two years as his XO Secretary Stone asked me what I wanted to do next. He said, “I’ll give you wherever job you want.”

I said, “I want to be an assistant division commander.” (This would be an infantry unit command with multiple support units from other branches.)

As an artilleryman I figured that I was best suited for that job because I had a lot of experience in maneuver units. I had been with and around the infantry since Vietnam. My first tour with the 1st Cav put me in combat with the infantry during fighting around Hue, the relief of Khe Sanh and the A Shau Valley Incursion. Then my battalion was with the 9th Infantry Division at Ft Lewis, Washington – so I was with infantry guys again. I did not command them, but lived with them and worked closely with them. Then I commanded the 7th Infantry Division Artillery at Ft Ord, California for the Panama operation, again in close proximity to the infantry. I had been at every level with the infantry, so it was a natural progression to be an assistant commander to an infantry division.

Instead I was offered the Corps artillery assignment at Ft. Sill, but I did not want to do that. I thought it would be too narrow a job, still all artillery and I wanted a broader job. So I said again I wanted to be an assistant infantry division commander.

Fortunately the Army listened. I became one of the two assistant division commanders of the 24th Infantry Division at Ft. Stewart, Georgia. This was the first time I was in the direct chain of command of infantry troops. This was something I wanted to do, because ultimately I wanted to be a Division Commander, and I knew this job would better my chances. I held that job for a year.

South Korea

Then in 1993 I was promoted to two star (major general) and went to Korea as Operations Officer for all forces in South Korea.

The organization was a collection of joint commands, so involved that its new Operations Officer needed an hour and a half briefing just to explain its structure. General DeFrancisco’s comments are here presented in outline form for purposes of clarity.

It was a complex set of four different organizations:

A United Nations Command (UNC) composed mainly of U.S. and Korean forces but included also small contingents from other nations

A Combined Forces Command (CFC) of Korean and U.S. forces

S. Forces Korea (USFK) was a joint command of U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine forces

And the Eighth Army composed solely of U.S. Army forces

UNC, CFC, and USFK were all commanded by the same Army four star while the Eighth Army was commanded by an Army three star.

I was operations officers for all four of those organization, each of which had a deputy commander reporting to me. I had:

A two-star Korean general as my deputy for the UNC and CFC

A Marine colonel for USFK

And an Army colonel for the Eighth Army.

This was another really interesting job. Kim Il-Sung was still in charge in North Korea. We had nuclear crises; we had border incursions; we had the North shelling the disputed islands. We had emergency after emergency. All a lot of excitement, and all due to the great people I worked with.

A Call To Return

While I am in Korea I get a call to return to Ft. Stewart to become the commanding general of the 24th Infantry Division, where I had been an assistant commander. My hope to put myself in line for a division commander position seemed to have worked; I never guessed it would be back with the 24th and that it would happen so quickly. I had been gone less than a year, so there were still a lot of people I knew and had worked with.

Major General De Francisco

Major General De Francisco

Commander, 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized)

Interviewed at Hunter Army Airfield

During my command of the 24th we executed a number of overlapping deployments. I sent troops to Kuwait and Saudi Arabia for about five months, and deployed a battalion plus for the Haitian Incursion.

The Haiti operation was sanctioned by the United Nations to restore the deposed president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. As the invading force was in route the Haitian leadership capitulated. Commanding general Hugh Shelton’s mission changed in an instant from military invader to diplomat, whose task was now to work out a peaceful transition of power.

I sent troops to Guantanamo Bay, which at the time was not the prison it is now. It was primarily a holding area for Cubans and Haitians fleeing their countries for the U.S. I sent mess personnel and Military Police, in another of those non-combat roles we so often were called on to perform.

At one point I had people in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Haiti and Guantanamo Bay, in addition to the deployments in the U.S. It was a very exciting and very enjoyable assignment.

Enough Fun

I’m getting ready to leave the division, then I got selected for a third star (lieutenant general) and assigned as the Deputy Commander in Chief of Pacific Command in Honolulu, Hawaii. This was 1996. The CINC (commander in chief) at the time was a four-star Navy Admiral and I was his deputy. It was a huge command with Army, Air Force, Navy and Marine forces deployed from the west coast of the United States, including Alaska, all the way through Hawaii, Korea, Japan and Thailand. It all came under the command and control of CINCPAC – Commander in Chief, Pacific Command.

Following this assignment it was time to leave active duty. There were only about thirty-five three-star generals in the Army and maybe ten or eleven four-stars. Things either worked out or they don’t at that level. There were no opportunities at the time enticing enough for me to stay, and I had thirty-four years worth of active duty. Lynne and I essentially had had enough fun in uniform. It was time to retire.

August 3, 2016

Joseph DeFrancisco – Battery Commander – Part Five

Settling In

After only a night at Phan Rang they flew me down to Sherry. If we had a Change Of Command ceremony I don’t remember it. I think I just walked in after Captain Heindrichs had already left.

Right away an old friend from my first Vietnam tour greeted me. He was a lone tree on a prominent ridgeline that I had used as a reference point for air missions out of Phan Thiet. At that time I was with the 2nd/7th Cav and we lived just off the Phan Thiet air strip. As the artillery liaison officer one of my principal jobs was to coordinate, execute and adjust fires on landing zones, called LZ preps, prior to inserting our troops. Many of our missions involved inserting troops into the hills and mountains, so I was always looking for reference points to help with my map navigation and LZ prep locations. This lone tree on a prominent ridge line was an ideal guide for many missions, and still there I was happy to see.

My initial impression of Sherry was that it was a well organized firebase. My first priority was to meet everyone and learn about the operation. I went around and met the two radar crews, I met the Quad-50 and Duster guys, I spent time talking to each of the gun crews, talked to the Chief of Smoke and to the maintenance sergeant, both good NCOs. I remember going around at night checking out guard towers and bunkers, even the beer bunker.

Spent a lot of time with the Fire Direction Control crew, learning gunnery from them. Remember I never went to the basic artillery course. I had just come out of the advanced course, where I learned about tactics and deployment of artillery forces, but nothing about firing the howitzers themselves. So I’d go into FDC in the afternoon and say, “OK guys, show me what you are doing here,” and they’d give me an impromptu course in gunnery.

I remember we had to go into Phan Thiet on convoys for our supplies because our air support had largely pulled out (along with the the 1/50th Mechanized, the last of the U.S. infantry). That’s how I got to know the motor sergeant so well. I’d go down there and say, “OK, how are we going to do this convoy, what have we got? We have to make sure we have enough spare parts because we don’t want trucks breaking down out there in the middle of nowhere.” I knew from my first tour with the 1st Cav that convoys could be hazardous, even though we would be in daylight both going and coming.

I spent a lot of time with First Sergeant Stollberg, a big guy and a godsend. We talked about what needed to be improved to keep things on an even keel, to make sure the troops were well cared for, that attitudes stayed positive, and to make sure nobody got hurt.

Capt. DeFrancisco and First Sergeant Stollberg

Capt. DeFrancisco and First Sergeant Stollberg

I was pleasantly surprised at the quality of the troops at Sherry, having just come from Ft. Sill where I had only handful of good guys in the whole battery, or what I encountered in Germany on my first assignment out of West Point where the battalion was lacking in morale, skill and quality of leadership. It was just the opposite at Sherry. Most of the people, although nobody wanted to be there, were very good and proud to have mastered whatever job they had. The gun crews and FDC were especially good. I was very, very happy with what I saw. This was a real tribute to Captain Heindrichs and all those who came before me and built this place. I was lucky to inherit it, and I was determined to make it better than I found it.

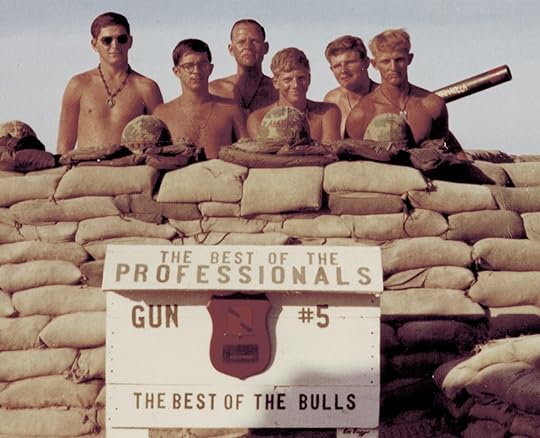

One example: The battery already had gun crew competitions when I arrived, but I spent a lot of time on these competitions in order to keep the crews sharp and to give them meaningful ways to occupy their time. Gradually these competitions grew more complex as the Chief of Smoke and First Sergeant began adding more tasks. Rivalry among the crews for bragging rights became intense. The results included highly trained and disciplined crews with neat, orderly gun pits, and just as important with greater pride and purpose.

Bragging Rights on Barbarella – Gun 5

Bragging Rights on Barbarella – Gun 5

The Argument

Toward the end of Captain DeFrancisco’s time at Sherry his executive officer was First Lieutenant Bob Christenson, a graduate of Officer Candidate School with clear ambitions outside the military. The two had a high opinion of one another, leading DeFrancisco to encourage a promising young officer to remain in the Army, and Christenson to make the argument for his battery commander to leave.

I thought the world of Lt. Christenson. We had this talk probably before or after one of my visits to FDC. I don’t know how it started, with me suggesting he stay in the Army, or him telling me to get out. But I do remember the exchange. He would say, “What are you spending your time in the Army for? This is crazy. There are a lot of other things you could do.”

Of course at the time I had the next couple of years very well laid out for me. I was already accepted into graduate school at Rice University in Houston, and I already had a teaching assignment at West Point when I graduated. I also knew I was in good shape to go to Command and General Staff College, even though it was a board selection. Back then it was a big deal. It still is a big deal, but back then bigger and competitive. So there was no way I was going to get out, especially having convinced my wife I ought to go to Vietnam again. Bob was going to loose that part of the argument.

I also lost my end of the argument with Bob. He was pretty sure what he wanted to do. He had served his time and he thought it was appropriate to leave the Army and get on with life.

Today Bob Christenson says of his battery commander, “Captain DeFrancisco was a great guy. This was his second tour in the same area of Vietnam, and he used to point out a tree that stood out on top of a distant ridgeline that we used as an aiming reference. He said he remembered that tree from his first tour.

“I thought I had Joe talked into getting out of the Army after our tour, but he stayed and I am glad he did. He was a great officer and person, and I’m sure he played an important role in getting the Army back on its feet after the Vietnam debacle.”

…………………………..

Captain DeFrancisco left Sherry in March 1971. He would serve another twenty-seven years in the Army, retiring a three-star general in 1998 with thirty-four years of active duty. Bob Christenson succeeded DeFrancisco as battery commander. Now a captain he left Sherry three months later, earned a law degree, and today is a practicing labor attorney.

July 27, 2016

Joseph DeFrancisco – Battery Commander – Part Four

A Wonderful Place

June of 1970 I am back in Vietnam. I get in country at Tan Son Nhut Airbase outside Saigon, where I am assigned to the First Field Force Provisional Artillery Group headquartered in Dalat.

The (First Field) Force Artillery Headquarters controlled three subordinate Artillery Groups, with a total strength of ten Field Artillery Battalions. These were the 41st Artillery Group, headquartered at Phu Cat, north of Qui Nhon; the 52nd Artillery Group, at Pleiku in the Central Highlands; and the First Field Force Vietnam Provisional Artillery Group, Dalat. Force Artillery Headquarters was in Phan Rang. From: Artillery Review, August 25, 1971

The Prov Group had such a general name because it was among the many temporary units in Vietnam not given a permanent unit name. At the time the 5/27 was one of four or five battalions assigned to this Prov Group.

So my next stop was Dalat. It was a beautiful place high up in the mountains, a university town. It had apparently been hit during TET but by this time all the damage was swept aside and it was a rather peaceful place. I went into Prov Group headquarters with the expectation that I would get some sort of a battalion or group staff job, since I had already commanded two batteries. I knew I was going to graduate school when I finished, so I thought, Well this would be a great place for a staff job, and maybe I could read at night and get ready for graduate school.

I go into Prov Group headquarters and the group commander Colonel Tuck says, “I got just the job for you. I’ve got this wonderful firebase down near Phan Thiet.”

Of course I knew Phan Thiet and said to myself, Man, I been there.

Colonel Tuck said, “It’s a wonderful place; it’s called LZ Sherry and I’d like you to take command of it.”

I said, “But sir, I’ve already commanded two artillery batteries. I’m sure there are others who would like to have a battery command. I’d like to be a G1.” (personnel officer)

He said, “No. LZ Sherry is an isolated base, it’s all by itself. You’re far away from battalion headquarters. You’re far away from everybody. I need a strong, experienced officer to go down there to take command. What do you say?”

I said, “I’d really like to be a staff officer.”

He said, “Let’s do this. You and I are going to fly down to Sherry tomorrow. You take a look at it, meet the outgoing battery commander, and then see what you have to say.”

The flight down to Sherry as I recall was well over an hour. (about 90 air miles south) On the way down I’m thinking to myself, Here I am a captain telling a full colonel I don’t want to take command of what he thinks is the greatest firebase he has. I think I better change my attitude here.

We landed on that little landing pad beside the firebase, and I was astounded at LZ Sherry. I had never seen anything like it compared to the firebases we had when I was with the First Cav. We’d throw them up overnight, string some barbed wire, dig trenches, put up a few sandbags, and that was it. But this place was a sophisticated firebase. The rows of concertina, the guard towers. The killer was the full length concrete basketball court. When I saw that I thought, Oh my god, what is this place?

The basketball court would make the Artillery Review two months later.

Whatever it was, I had already made up my mind I was not going to tell this O-6 commander that I did not want his firebase. I told him, “This is just wonderful. It exceeds anything I expected. I’d be happy … I’d be honored to take this unit.”

The outgoing battery commander, Captain Chuck Heindrichs, was a West Point classmate of mine. Even though we were classmates I did not know him. After that initial two hour visit I never met Captain Heindrichs again, and I never saw the Prov Group commander again the whole time I was at Sherry. He never visited, and I know I never went back to Dalat. The next time I saw Colonel Tuck was at a football game at West Point when I was on the faculty.

I think the colonel let me go back to Dalat to pick up my bags, but that was it. After I got my bags at Dalat now I had to go to Phan Rang to meet my battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Tucker (not to be confused with the Prov Group commander Colonel Tuck). He apparently had no say in the matter, or had looked at my record and said OK.

A Logical Question

This being 1970 the U.S. had already determined to get out of Vietnam. Vietnamization was going on, and we were in the throes of disengaging. In light of this, when I was getting my initial orders, I asked Lt. Col. Tucker what our mission was at Sherry. He told me number one was to stay in contact with the engineers working on Highway 1, and fire in support of them when they needed help. Number two, occasionally support armored operations in the vicinity. But the most important thing to keep foremost in mind was, Don’t get anybody killed. He said, “Make sure you have no casualties because we’re getting out of this war and politically we can’t stand casualties.”

I said to him in my naïve way, a captain talking to a lieutenant colonel, “So basically we have this very sophisticated firebase out in the middle of nowhere, and our primary mission is to take care of ourselves. So what if we were just not there?”

That did not go over well. He dismissed me saying, “We’re there and we’re going to stay there. It’s important that we show presence.”

That preyed on my mind throughout the time I was at Sherry. Here we are in the middle of nowhere, we must have close to 150 people on this firebase who can’t go anywhere or do anything outside the wire. Our mission is to take care of ourselves. Something is wrong with this picture.

The whole time I was at Sherry they would never let me off the firebase, I think because it was the kind of place they always wanted the guy in charge to be there. I left Sherry once or twice to go to a meeting in Phan Rang, but they never let me spend the night. In fact one time it was getting late and I said, “Where am I going to spend the night?” No, no, no, you got to get back, we have to have a commander on the base. I never spent a single night away from Sherry from the time I arrived to the time I left.

During Captain DeFrancisco’s tenure at Sherry the firebase sustained continued mortar attacks and a nasty recoilless rifle attack from an NVA unit. These resulted in on-going casualties, but none of them fatal.

July 20, 2016

Joseph DeFrancisco – Battery Commander – Part three

Divorce Artillery Style

I came home from Vietnam in June of ’68 and went to the advanced artillery course at Ft. Sill, happy that I’m finally going to get to go to artillery school. I get there and that is when I find out the artillery branch had split into two separate branches: Field Artillery (FA) headquartered a Ft. Sill, and Air Defense Artillery (ADA) headquartered at Ft. Bliss, Texas.

Air Defense Artillery encompasses twin 40 mm cannon Dusters, Quad-50 machine guns and searchlights. Field Artillery encompasses all sizes of howitzers. The split between the two became official in 1968 following recommendations dating back to 1963. There had been a longstanding recognition that training officers in the different skillsets for field artillery and air defense served neither well. Attempting to train hybrid FA-ADA officers simply “spawned mediocrity.” The two disciplines already had well developed training centers and a cadre of officers focused on their particular areas, therefore the split largely formalized what had become an operational reality.

Along with the split the brass insignia also changed. The brass insignia I wore in Vietnam, the crossed cannons with the missile in the middle, would become the ADA insignia. And Field Artillery would get its own new insignia, crossed cannons without the missile.

Original Artillery brass retained by ADA

Original Artillery brass retained by ADA

New Field Artillery brass

New Field Artillery brass

So we changed brass. Many of the officers who had to change their branch to ADA did not like that idea. People who had a long military background and had grown up in the military got emotional about it. They wanted to be Field Artillery. To them it was a big deal. To me it was not a big deal because I stayed in FA. If I had been assigned to ADA I might have felt differently.

After being in Vietnam for a year my time in FA school at Ft. Sill was a very enjoyable time. Just living in a house with my family. A lot of the people in the course with me I had met and befriended in Vietnam. It was a pleasant year.

Another Soul Searching Decision

At the end of that year it was time to find out where you were going next. They gave me three choices. I could go back to Germany, I could go to Ft. Knox, or I could stay at Ft. Sill. But Field Artillery brass said that no matter where you go, it’s only going to be for a year, and then you’re back in Vietnam. That was a traumatic thing for me and for my wife Lynne to learn. The only remaining option was to get out of the Army.

After a lot of soul searching we decided to stay in the Army. We stayed because at the end of my second tour in Vietnam the Army promised to send me to graduate school for an advanced degree to teach history at West Point, which was something I wanted to do. With that prospect in mind Lynne very courageously said, OK, we’ll do another year. At the time we had been married about five years. We celebrated our 50th wedding anniversary in November 2015. Over the years she has been an important part of everything I’ve done.

Tough Duty