Ed Gaydos's Blog, page 6

April 20, 2016

Mike Jordan – Duster Platoon Leader – Part Four

Early Warning System

At Betty it was routine for me every evening to take a shower and put on a clean uniform and go to supper. After supper I would go to the TOC (Tactical Operations Center) and sit in on the 3/506 Infantry briefing where they outlined the plans for the next day. They also covered in that briefing the free fire areas, and that was most important to me, so that I could let the Dusters know what azimuth sectors they had free fire in. Whatever unit we were with we would fire H&I, harassing and interdiction fire, randomly throughout the night.

The final part of my routine for the night on my way back to the platoon I ‘d drive along the top of the bluff overlooking the Phan Thiet bay. Usually the bay was black, with just a few scatterings of lights out over the water, a late fisherman maybe or somebody running contraband. But sometimes it would look like Times Square, there would be so many lights on the water. Everybody who had a boat or sampan was on the water and away from town because word had gotten around that there would likely be an attack that night against the city or LZ Betty. And that was our first indication we were going to get hit that night. Those were the nights you went back and kept a flack jacket next to your bunk. It was right seventy-five percent of the time.

Not Feelin’ The Love

With the battalion headquarters for the 4/60 four hundred and fifty miles away up at An Khe, I became the battalion senior officer for the Phan Thiet area, and I operated very independently of my battalion headquarters. In the six months I was at Phan Thiet I got just a single visit from two different battalion commanders who stopped in just to say hi, to look and see how we were doing. I’ll never forget one of those visits.

I had just attended the evening 3/506 briefing and gotten our free fire zones for the night. There was this infantry captain who was in a slot they called the Assistant S3 Air, the guy who was responsible for all of the 3/506 airborne assault operations. This guy came up to me after the briefing and said, “You’re the Duster guy, huh?”

“Yeah.”

“Well your goddamn Dusters – his words – they give away our position every night. The VC know exactly where our perimeter is because all they got to do is look at where you’re firing from.”

I said, “Hey, sir, (I was a first lieutenant) I’ve got my mission.”

He said, “Well, you don’t tonight. I’m not going to give you any clearance to fire.”

“Okay, if that’s the way you want it.”

I knew my battalion commander was coming in the next morning. I had the two Duster tracks at Betty pack up everything, load their trailers, hook the trailers up to the back of the Dusters, and waiting at the chopper pad when the battalion commander arrived. He said, “Jordan, what the hell’s going on?”

“I was told by the infantry last night they don’t want us here. You and I both know there’s a great demand for Dusters all over South Vietnam. I’m just waiting for orders for someplace to move to.”

“Stand pat. Don’t go anywhere.”

Come to find out that my battalion commander and the battalion commander of the 3/506 went to the Command and General Staff College together. He borrowed my jeep, went straight over to the 3/506 battalion headquarters, walked straight through their S1 section with not so much as a “Hey captain, I’m here to see your battalion commander,” and walked in there and said to his old classmate, “What the hell are you doing telling my officers they’re not wanted down here?”

The infantry colonel was just in shock. “Of course we want your Dusters here.”

“Well apparently your staff doesn’t see it that way.”

I had it on good report later that day that my captain was on his way out to one of the line companies in the field, no longer at his cushy TOC job (Tactical Operations Center).

Only three battalions of Dusters went to Vietnam, for a total of no more than two hundred Dusters in the entire country, and that’s counting the ones down for maintenance. Having the protection of a Duster on an operation was a luxury.

It’s A Good Deal When Everybody’s Happy

The only person I worked with on fire missions was a Marine Corps gunnery liaison lieutenant at the LZ Betty TOC. He found out I could shoot indirect fire with the Dusters (lobbing rounds vs. shooting directly at a target), and I found out he could talk to the battleship New Jersey and any other ships on station near Phan Thiet. So we exchanged fire missions. There were some places he called me to put fire in, and I routinely called him and asked for help, but of a different nature.

The 40 mm guns that we had on the tracks were also the Navy anti aircraft guns they had on the ships from WWII – like you’d see on Victory At Sea. These were 40 mm BOFORS guns (Swedish manufacture and first used by the U.S. in WWII). The Navy still had the full stock of repair parts for those guns. Whenever I came up with a part that was hard to get I’d call up my Marine Corp buddy and I’d say, “Hey, who you got on station?”

He’d tell me and I’d ask, “Do they still have the 40s mounted?”

He’d say, “Yeah.”

And I’d say, “Can you call out there and see if they have such-and-such a part?”

He’d say, “Sure.”

But the Navy would always come back with, “What have you got to trade?”

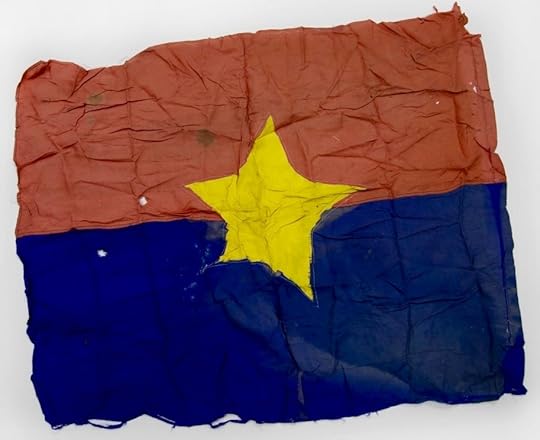

The guys out on the firebases loved to make phony VC flags and stain them with ketchup to make them look like blood. So my Marine pal would tell the Navy, “How about a genuine, authentic VC battle flag?”

“Oh Yeah,” they’d say, “Yeah!”

Then on chopper trips out to these ships to coordinate with the gunnery officer my Marine would bring back a box of gun parts for me. For sure those flags are hanging all over the Navy.

During the war there was a white-hot market for VC battle flags, most of them fakes produced by U.S. soldiers, South Vietnamese military and enterprising civilians – anyone with a needle and thread and a jar of pig’s blood, or in Jordan’s experience, a bottle of ketchup. The demand for VC flags intensified after the war and continues today. According to one expert there are a miniscule number of genuine VC battle flags in existence, and for every genuine one there are ten thousand fakes.

VC battle flag complete with bullet holes and blood

VC battle flag complete with bullet holes and blood

Is it genuine or fake?

April 13, 2016

Mike Jordan – Duster Platoon Leader – Part Three

Duster Details

I had eight Dusters under my command. Four of them were at LZ Betty, two down on the airfield and two at the 105 battery up on the hill that we called the OP (outpost). And I had my platoon command post and support units at Betty.

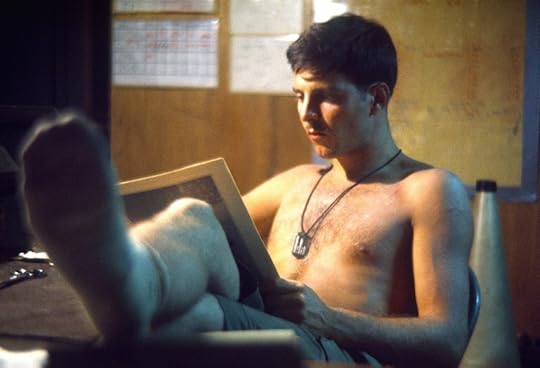

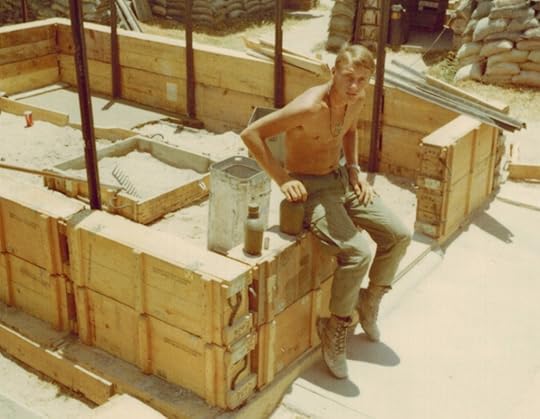

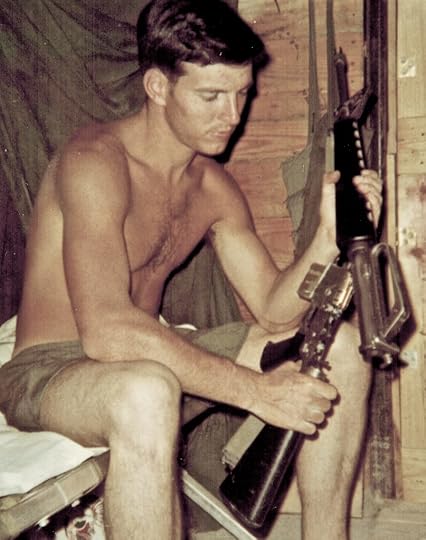

1st Lieutenant Mike Jordan

1st Lieutenant Mike Jordan

Sporting an M-79 grenade launcher in front of twin 40 mm Duster canons

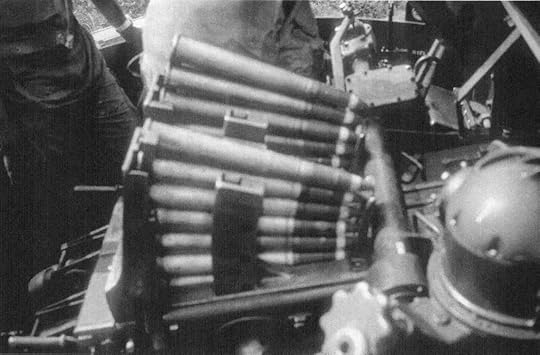

I had my other four Dusters up at LZ Sandy, the 8 inch and 175 mm battery. At Sandy I had an E-7 platoon sergeant, Tanker Smith, in charge as my primary second in command. He was an armor guy from Europe so he had the nickname Tanker. We covered all four sides of the firebase perimeter. When someone tried to get into the place it was up to the Dusters to saturate all four sides of the perimeter with the 40 mm and keep them out. I had an arrangement with the various artillery battery commanders at Sandy that as soon as we started taking any kind of incoming my four guns would open up and saturate the perimeter. And since the crews on the howitzers couldn’t do anything, because they didn’t have beehive rounds, they ran to the nearest Duster and started breaking open ammo cans to feed ammo into the track. The ammo came in four-round clips, four clips in a can. The cans were safety wired shut and it took a hammer to unlock the lid, and then they tossed the clips up to the guys on the back of the track.

Sergeant Joe Belardo with 40 mm ammo clip

Sergeant Joe Belardo with 40 mm ammo clip

From his book Dusterman: Vietnam

I always laugh, you pick up any kind of history and you read specs on the Duster and it says 240 rounds a minute when firing full automatic with both guns. Well I never did encounter a crew that could do that. The Duster had two automatic loaders, one for each gun.

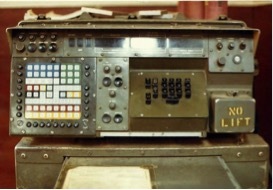

Twin automatic loaders

Twin automatic loaders

From Dusterman: Vietnam

A cannoneer would take a clip of those rounds and push it down into that loader, and once the first round got picked up in the loader it sucked up the other three automatically. Very few PFCs and Spec 4s that were slotted as cannoneers that could keep up with the gun.

The Daily Mundane

The roads around my battery headquarters up at Tuy Hoa were such that they were rarely able to use a piece of equipment called the M-578 Vehicle, Tracked Recovery (VTR). It was a light crane mounted on the same chassis and track as the 8 inch howitzer. The old man asked me, “You got a use for it down there?”

“Hell Yeah.”

I did depot level maintenance at the platoon level, which was unique. We would pull the Dusters in with the VRT, or haul them in on lowboys.

M-578 Vehicle, Tracked Recovery (VTR)

M-578 Vehicle, Tracked Recovery (VTR)

Duster on a lowboy

Duster on a lowboy

When we had to put in a new engine, which we did frequently, I’d go up to the maintenance company with the paperwork. The company commander or maintenance officer would sign the requisition which I had already filled out. I was not authorized to make the requisition, but they were. When the engines came in they were in these big sealed steel boxes, and they’d call me and say, “Hey Mike, we got your Duster engine in.” I’d send my deuce and a half truck, alone with the VTR with the crane on it, and they’d pick it up, put it in the truck, bring it back. Then we’d use the VTR crane to lift the old engine out and put the new one in. We did all that ourselves.

The other thing we did, our ammo was so unique and not used by anybody else that I got the ammo supply point there at Betty to requisition it and stock it for us, and whenever they needed it out at Sandy I had this one old deuce and a half that had no canvas on it, no windshield, it was just a flat bed. We’d load up those pallets of ammo in air sling cargo nets, drive that truck out into the middle of the helipad and the Chinooks would come in and hover and we’d hook up the sling and they’d fly it out to Sandy.

So I got to know the Chinook guys pretty well. Whenever I needed to go up to the battery headquarters at Tuy Hoa, I’d call the guys from the Chinook company up at Cam Ranh to find out what they had coming down to Betty. At the end of the day before they left to go back to Cam Ranh I’d meet them at the chopper pad and we’d drive my jeep up the loading ramp into the Chinook and they’d fly me as far as Cam Ranh. I’d spend the night in the transient BOQ there (Bachelor Officer Quarters) and then drive into Tuy Hoa the next day.

April 6, 2016

Mike Jordan – Duster Platoon Leader – Part Two

The Wives Always Know

I graduated from Officer Candidate School at Ft. Sill and got my commission in January of 1968. Just before Christmas – we hadn’t gotten our assignment orders yet – our training battery commander said to us, “Wherever you are when I get your assignment orders I will come and tell you.” So we’re sitting in class one day with this major up front trying to teach us about engineering tactics, how to build bridges and clear mine fields and that kind of stuff, when our battery commander came into the back of the room. The room started to buzz and the major said, “Captain, obviously you have something these candidates are more interested in than what I am trying to teach them about engineering tactics, so why don’t you take over.”

They had told us all along, You will not go directly to Vietnam, you will get an assignment here in Ft. Sill, or Europe, or CONUS (Continental United States), but you will not go directly to Vietnam. Well the wives had a wives club in conjunction with the officers’ wives. Mary Beth came home after one of their luncheons and said, “Your class is going to send guys directly to Vietnam.”

I said, “No, no, no, no. That ain’t gonna happen.”

Well our battery commander gets up there in the front of the class and the first thing he says is, “There are seventeen of you going directly to Vietnam.” The wives knew more than we did. He read those seventeen names first, and then he started reading the rest of them. There was one other guy and me went to St. Louis to the Nike Hercules battalion.

Safe In Grafton

The Nike Hercules missile site was above Grafton, Illinois at Pere Marquette State Park (across the Mississippi River from St. Louis). At that time there were four Nike Hercules missile sites protecting the city of St. Louis. Throughout the nation at that time we built these missile sites around all the big cities as a carryover from the tactics of WWII assuming that the Russians were going to do the same things to us that we did in Germany. We sat there waiting for huge flights of Russian bombers to come over the North Pole to shoot them down, which needless to say they never came. Thank goodness.

When I first got there it was funny. The captain and all the lieutenants and warrant officers said, Oh man, you’re lucky being here in the Nike system, it’s the best thing that ever happened because we don’t have any Nikes in Vietnam. We got some HAWKS, but no Nikes, so you’re safe. Ten months later in the Fall of 1968 I got orders to go to Nam because they were closing the Nike site. There were two other cities that deactivated their sites in ’68: Kansas City and Dallas/Ft. Worth. These sites were the deepest into the interior of the U.S. and they felt that if we ever had to shoot at Russian bombers coming over, by the time they got to these cities it was too damn late. Over the next several years they proceeded to close all of the Nike Hercules sites down.

Vietnam

But before Vietnam I went to Ft. Bliss in Texas for six weeks of Duster school, after which I picked up a new MOS of 1174 (Light Air Defense Artillery Unit Commander).

The First Kind of Promotion

In those days you could go from 2nd lieutenant to 1st lieutenant in one year, and then to captain in another year. I made 1st lieutenant two days after I arrived in Long Binh, Vietnam. I did not yet have my promotion orders, but they told me to go ahead and just sew the 1st lieutenant bars on my uniforms. It was three or four months later that I finally got my orders, along with a pretty significant chunk of back pay.

The Second Kind – A Blood Promotion

I arrived at LZ Betty in January of 1969 assigned to the 1st Duster platoon, Alpha Battery, 4/60 Air Defense Artillery battalion. I was initially the assistant platoon leader under another 1st lieutenant, Frank Hewitt, who had won a Silver Star and was on a six-month extension in Vietnam. One day he left for Nha Trang to see one of our troops who was in the hospital, and that was the last I saw of him. He was loading his jeep into a Chinook helicopter in Nha Trang, and instead of using an enlisted driver, as called for by policy, he drove it himself and proceeded to roll it over. Frank was injured severely with a major head injury. He was driving with the windshield down, and even if it had been up I don’t know that it would have done much to protect him. They evacuated him to Japan, and subsequently to the Army hospital in Denver next to Stapleton Airport. He was from Colorado Springs, so that’s where they took him to be close to his family. I never saw or heard from him again.

It was February when he had the accident, and I got a letter late in the Spring from his parents wanting to know why we had not sent his property back home to him. “Dear Mr. Hewitt,” I wrote, “I’m sorry Frank’s property has not arrived, but they left here.” There were guys who sorted through packages and certainly if there was any kind of war trophy in there, that stuff would always disappear.

TET 69

I took over as platoon leader from Frank, and assumed the unofficial commander’s radio call sign of “Duster 6.” Shortly after I took over the platoon the Second TET hit. The last night of the declared truce LZ Betty came under mortar and sapper attacks – the morning of February 22, 1969. We were sitting right next to the infantry’s four-deuce (4.2 inch diameter) mortar company. A sapper crawled through the wire and threw a satchel charge into the ammo bunker at the four-deuce mortar position. It started a fire and then caused a massive explosion. I don’t know how many hundreds of those four-deuce mortar rounds cooked off simultaneously. The blast wave and the shock wave just leveled everything in my platoon area.

At the time of the initial attack, before the ammo bunker explosion, I evacuated my platoon area and was doing a retrograde movement back toward the airfield one building, one structure, and one anything-to-hide-behind at a time. I was on my hands and knees behind the latrine when the blast went off. The back wall of the latrine blew out and landed on top of me. Thankfully I was not injured. I now have a shadowbox that I made upon retirement for all my awards and decorations, and I am very proud of the fact that there is no Purple Heart up there.

Engineers had just built for us four or five SEA huts (South East Asia huts), corrugated roofs, screened-in windows in the upper half, and solid walls behind sandbags on the lower half, all on a slab of concrete. They were prominent throughout Vietnam at base camp type places. The concussion from the secondary explosion was so bad that it just leveled those SEA huts.

Dave Fitchpatrick, Gun 5 section chief at Sherry, said he could feel the heat flashes five miles away.

Betty the morning after

Betty the morning after

Picture courtesy Dave Fitchpatrick

My primary means of communication with my battery headquarters up in Tuy Hoa (two hundred miles north) was an AN/GRC-106 radio. It worked off of a doublet antenna, a long wire strung between two poles. You had to put it up 90 degrees to the direction you wanted to transmit to. Well, the two poles that held my antenna got blown down that night. So first thing in the morning I can’t even call the battery commander to tell him that we were hit, that we suffered damages, that we had a couple injuries, but not bad enough to be Medevac’d. I didn’t have any communications. So I am wandering around all over Betty that morning trying to find anybody that’s got a 106 AM radio. I ended up at the MARS station and a guy over there said, “Why I can make you an antenna. Just give me some WD-1 wire.

While I was at the MARS station I put in a call to my wife.

The Military Affiliate Radio Service used phone-patch connections over shortwave radios to place personal calls to the States.

I said, “You’re probably going to hear about this, that we were attacked last night, but I’m Okay.” Of course she had not yet heard about it. Here she gets this MARS call where you had to do the OVER nonsense and me telling her that I’m Okay.

She said, “Well I really didn’t have any reason to think you weren’t Okay, till you called.”

We finally strung up an antenna and late in the afternoon I called Tuy Hoa. “Guess what, guys. We kind of got blown away last night.”

March 30, 2016

Mike Jordan – Duster Platoon Leader – Part One

Into The Army

I was going to school majoring in Engineering at what is now the Missouri Science and Technology University in Rolla; it was the University of Missouri at Rolla in those days (and a highly respected engineering program). I was in the ROTC program, but not by choice. In those days, in 1964 when I started at Rolla, if you were an able bodied male student you had to take ROTC. It was mandatory for your freshman and sophomore years. It stems back to the Land Grant College Act from World War One. (The original Land-Grant legislation passed in 1862, with various extensions over the years until its final expansion in 1914.) The federal government said, Hey states, here’s property. You can go out and build a college, agricultural or technology, and oh by the way in payback it’s mandatory that all of your freshmen and sophomore able bodied male students take ROTC. If their grades are good enough at the end of their sophomore year, and they want to apply for the advanced ROTC, that’s a separate personnel action and we’ll consider it.

My first summer home my uncle had a surveying company in Creve Coeur and I went to work for him. I was not able to save up enough money to go back to Rolla in the Fall so I kept working and went to the University of Missouri in St. Louis, and then went back to Rolla in January. That Fall I went on probation because I was having too much fun playing pinochle every night instead of studying. When I went on scholastic probation the draft reclassified me to 1-A (top of the list). To keep from getting drafted I decided to enlist, because that gave you some choices.

Enlisting to avoid the draft was a familiar story during Vietnam, weakening the statistic that only 25% of those who served in Vietnam were drafted, and giving the lie to the idea that most of the guys in Vietnam wanted to be there.

When you enlisted you got three choices for which branch of the Army you wanted, one of which had to be a combat arm. For their other two choices guys would usually pick things like Intelligence or Supply or Personnel, places where you didn’t get shot at. Still everybody at that time all around me were getting infantry, and that was the last thing I wanted. So when it came down to making my choices I put down three combat arms instead of just one. Corp of Engineers at Ft. Belvoir was my first choice. Armor at Ft. Knox was my second because a couple college buddies went there, and Artillery at Ft. Sill was my third. So now the Army could always come back and say we gave you what you asked for.

When I was home for Thanksgiving I went down to the Mart building in downtown St. Louis and took my induction physical the day after Thanksgiving. Classes back at the university didn’t start until the Monday afternoon following a holiday weekend, so I went by my draft board Monday morning and said, “I took my physical last Friday and I’m 1-A, when are you going to call me?”

They said, “Probably in February,” and they were good to their word.

Advice To Last a Lifetime

I married Mary Beth, my high school sweetheart on February 4th and two weeks later left for basic training at Fort Leonard Wood. My dad dropped me off for my induction, which happened to be his birthday, the 20th of February. We’re sitting out in the car and it’s six o’clock in the morning in downtown St. Louis and it’s colder than hell. My dad was in the Navy in WWII and he says, “Let me give you some advice before you go in there from an old Navy guy. I know you want to be an officer. So let me tell you this. We used to call them chiefs, in the Army you call ‘em sergeants, and let me tell you right now, even if you’re a lieutenant, do what the sergeant tells you to do. Second, don’t ever volunteer for anything. Third, there’s a war going on right now and you’re probably going to end up over there. So let me warn you now, keep your ass down so you don’t get it shot off.”

In ’94 when my dad died, my brother-in-law who was a minister was going to conduct the memorial service. He called me up a couple days beforehand and said, “Tell me some things your dad told you that had a long lasting impact on your life.” I told him this story word for word and when we got to that third piece of advice he said, “Well, we probably ought to change that last one to ‘keep your head down.’” To this day I cite those three things he said to me as the most sage advice my father ever gave me, especially given that I ended up staying in the Army for twenty years.

A Winding Road To Artillery

When I got to Ft. Leonard Wood for basic training I applied for Officer Candidate School. I had been majoring in engineering at Rolla, so I asked for Combat Engineering again. After I finished basic at Leonard Wood I went to Ft. Lewis, Washington Advanced Individual Training in mortars. If all went well I’d go to Ft. Belvoir right out of AIT.

Our AIT company at Lewis was different. We only had sixty-three guys in the company, instead of the two hundred that you normally had. Half of us were wanting to go to OCS, and the other half were National Guard and Enlisted Reserve from Alaska, and they were mostly Eskimos. So we ended up with one platoon of guys who were OCS oriented, and the other platoon was the Guard and Reserve guys. Every morning the drill sergeants would flip coins to see who would take us to training and who would stay behind and shoot pool in the dayroom.

The funniest thing, when we would go to the rifle range the squatting position was one of the hardest firing positions to maintain. Well these Eskimos used to go out on the ice flows and wait all day for a shot at a polar bear. These guys could go out there and squat forever. When the firing range instructor announced the next firing position would be the squatting position, for them is was, Okay, bang, bang, bang.

I should have gone straight to OCS after Ft. Lewis, but my OCS application got lost and I had to apply all over again. And I had to take an OCS physical. When I graduated from AIT I still didn’t have my OCS assignment, so I talked the First Sergeant into letting me take a two week leave back in St. Louis. I told him I had been married only two weeks before leaving for basic, and I think that helped. I got back to Lewis on a Friday afternoon. The First Sergeant called me into the orderly room and said, “You got your OCS orders. You’re going to Ft. Sill for artillery OCS and you’re leaving Tuesday.” So much for getting my first choice.

I cleared post the next morning: running around for paperwork to finance, personnel, shot records, etc. Those were the days of Westmoreland when everybody had to work five and a half days, making Saturday morning a duty day. Later on when I got to be a captain and battery commander of a HAWK battery (Homing All the Way Killer) in Germany, guys would come in and say, “Hey captain, I need two weeks to clear post.”

“Bullshit. I know how to clear post in half a day, but I’ll be a good guy though and give you a whole day.”

Mike Jordan – Duster Platoon Leader

Into The Army

I was going to school majoring in Engineering at what is now the Missouri Science and Technology University in Rolla; it was the University of Missouri at Rolla in those days (and a highly respected engineering program). I was in the ROTC program, but not by choice. In those days, in 1964 when I started at Rolla, if you were an able bodied male student you had to take ROTC. It was mandatory for your freshman and sophomore years. It stems back to the Land Grant College Act from World War One. (The original Land-Grant legislation passed in 1862, with various extensions over the years until its final expansion in 1914.) The federal government said, Hey states, here’s property. You can go out and build a college, agricultural or technology, and oh by the way in payback it’s mandatory that all of your freshmen and sophomore able bodied male students take ROTC. If their grades are good enough at the end of their sophomore year, and they want to apply for the advanced ROTC, that’s a separate personnel action and we’ll consider it.

My first summer home my uncle had a surveying company in Creve Coeur and I went to work for him. I was not able to save up enough money to go back to Rolla in the Fall so I kept working and went to the University of Missouri in St. Louis, and then went back to Rolla in January. That Fall I went on probation because I was having too much fun playing pinochle every night instead of studying. When I went on scholastic probation the draft reclassified me to 1-A (top of the list). To keep from getting drafted I decided to enlist, because that gave you some choices.

Enlisting to avoid the draft was a familiar story during Vietnam, weakening the statistic that only 25% of those who served in Vietnam were drafted, and giving the lie to the idea that most of the guys in Vietnam wanted to be there.

When you enlisted you got three choices for which branch of the Army you wanted, one of which had to be a combat arm. For their other two choices guys would usually pick things like Intelligence or Supply or Personnel, places where you didn’t get shot at. Still everybody at that time all around me were getting infantry, and that was the last thing I wanted. So when it came down to making my choices I put down three combat arms instead of just one. Corp of Engineers at Ft. Belvoir was my first choice. Armor at Ft. Knox was my second because a couple college buddies went there, and Artillery at Ft. Sill was my third. So now the Army could always come back and say we gave you what you asked for.

When I was home for Thanksgiving I went down to the Mart building in downtown St. Louis and took my induction physical the day after Thanksgiving. Classes back at the university didn’t start until the Monday afternoon following a holiday weekend, so I went by my draft board Monday morning and said, “I took my physical last Friday and I’m 1-A, when are you going to call me?”

They said, “Probably in February,” and they were good to their word.

Advice To Last a Lifetime

I married Mary Beth, my high school sweetheart on February 4th and two weeks later left for basic training at Fort Leonard Wood. My dad dropped me off for my induction, which happened to be his birthday, the 20th of February. We’re sitting out in the car and it’s six o’clock in the morning in downtown St. Louis and it’s colder than hell. My dad was in the Navy in WWII and he says, “Let me give you some advice before you go in there from an old Navy guy. I know you want to be an officer. So let me tell you this. We used to call them chiefs, in the Army you call ‘em sergeants, and let me tell you right now, even if you’re a lieutenant, do what the sergeant tells you to do. Second, don’t ever volunteer for anything. Third, there’s a war going on right now and you’re probably going to end up over there. So let me warn you now, keep your ass down so you don’t get it shot off.”

In ’94 when my dad died, my brother-in-law who was a minister was going to conduct the memorial service. He called me up a couple days beforehand and said, “Tell me some things your dad told you that had a long lasting impact on your life.” I told him this story word for word and when we got to that third piece of advice he said, “Well, we probably ought to change that last one to ‘keep your head down.’” To this day I cite those three things he said to me as the most sage advice my father ever gave me, especially given that I ended up staying in the Army for twenty years.

A Winding Road To Artillery

When I got to Ft. Leonard Wood for basic training I applied for Officer Candidate School. I had been majoring in engineering at Rolla, so I asked for Combat Engineering again. After I finished basic at Leonard Wood I went to Ft. Lewis, Washington Advanced Individual Training in mortars. If all went well I’d go to Ft. Belvoir right out of AIT.

Our AIT company at Lewis was different. We only had sixty-three guys in the company, instead of the two hundred that you normally had. Half of us were wanting to go to OCS, and the other half were National Guard and Enlisted Reserve from Alaska, and they were mostly Eskimos. So we ended up with one platoon of guys who were OCS oriented, and the other platoon was the Guard and Reserve guys. Every morning the drill sergeants would flip coins to see who would take us to training and who would stay behind and shoot pool in the dayroom.

The funniest thing, when we would go to the rifle range the squatting position was one of the hardest firing positions to maintain. Well these Eskimos used to go out on the ice flows and wait all day for a shot at a polar bear. These guys could go out there and squat forever. When the firing range instructor announced the next firing position would be the squatting position, for them is was, Okay, bang, bang, bang.

I should have gone straight to OCS after Ft. Lewis, but my OCS application got lost and I had to apply all over again. And I had to take an OCS physical. When I graduated from AIT I still didn’t have my OCS assignment, so I talked the First Sergeant into letting me take a two week leave back in St. Louis. I told him I had been married only two weeks before leaving for basic, and I think that helped. I got back to Lewis on a Friday afternoon. The First Sergeant called me into the orderly room and said, “You got your OCS orders. You’re going to Ft. Sill for artillery OCS and you’re leaving Tuesday.” So much for getting my first choice.

I cleared post the next morning: running around for paperwork to finance, personnel, shot records, etc. Those were the days of Westmoreland when everybody had to work five and a half days, making Saturday morning a duty day. Later on when I got to be a captain and battery commander of a HAWK battery (Homing All the Way Killer) in Germany, guys would come in and say, “Hey captain, I need two weeks to clear post.”

“Bullshit. I know how to clear post in half a day, but I’ll be a good guy though and give you a whole day.”

March 16, 2016

Kim Martin – Fire Direction Control – Part Three

Waiting for the Next One To Land

When we got mortared there were usually three, one after another, then it would be over.

Sherry was so quick to return fire on mortar sites that the enemy just had time to pop off a quick round of mortars, and then had to clear out. Usually.

We got mortared one night and they all hit near a radar installation right across from FDC. After the third one hit and things got quiet, I went to go check to see if they were Okay. Everybody was fine, no damage, so I started heading back to FDC and another volley started coming in. The first one hit in front of me maybe sixty feet away. Then the second one hit closer. I hit the ground thinking the third one is going to hit right on top of me. I figured, okay, this is it. When it hits what’s it going to do to me, am I going to survive? Maimed, injured? All those things go quickly through your mind. I don’t remember being particularly scared. Just when’s it going to hit? I’m lying there listening and nothing happened. The third one never came.

Last Fatality at LZ Sherry

Jeffrey Lynn Davis was killed in a mortar attack on April 16, 1970 while manning Gun 2 next to the FDC bunker.

I was on duty in FDC at the time. The mortar just missed the FDC shack and went into the top of the ammo bunker. The explosion was really loud, and I remember sand falling onto the roof of the FDC bunker. It came really close to blowing up everything. It lodged between the inner frame of the bunker and the sandbags, so it didn’t get to the ammo inside. However the shrapnel from it caught him.

The mortar round that killed Jeffrey Davis

The mortar round that killed Jeffrey Davis

Picture courtesy Lt. Bob Christenson

Bob Christenson took this picture to send home. On the back he wrote, “This is the outside of Gun 2’s ammo bunker. In the middle is a mortar fin which hit and stuck during a mortar attack. One guy in the bunker was killed and the other one hurt badly. The section decided to leave the mortar fin there.”

I remember Lieutenant Christenson, more of a down to earth, affable guy that was really easy to talk to. He’d come into our hooch to visit, almost like he had little regard for rank. He was a good guy and well respected.

The Last Scare

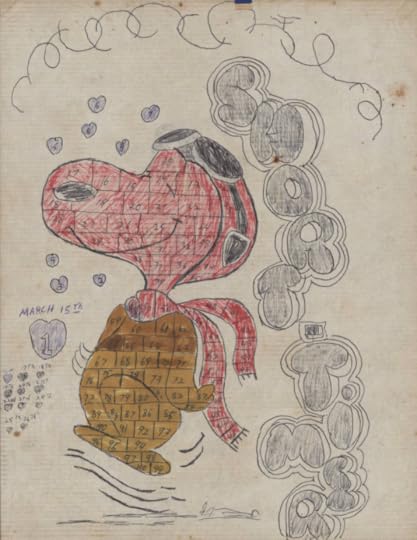

Due to the reduction of troops I got an early out of 30 days. So my tour lasted eleven months rather than the full year as I had expected. I had my Snoopy puzzle calendar almost completely filled in, feeling good about my world, and definitely very short.

Typical Snoopy short-timer calendar

Typical Snoopy short-timer calendar

(Arkansas Vietnam War Project)

One week before my tour ended this happened. It was after dark, probably about 10:00 in the evening, when the battery was abruptly alerted to a potential charge through its perimeter near one of the guard towers. A red star cluster flare had been fired from the tower signaling that a Viet Cong sneak attack was under way.

I was off duty, being on the twelve hour day shift in FDC, and so was abruptly awakened by the battery siren alerting everyone to their protective battle positions preparing for an attack. I immediately grabbed my M-16 and flack jacket and proceeded to our assigned bunker just outside the FDC bunker with a fellow FDC buddy who was also on my shift. I think he was Lynn (Curley) Holzer, but it has been so long ago that I cannot be sure. As I settled into the bunker, illumination rounds were being fired all over, lighting the night sky like a Fourth of July celebration. Men were running everywhere to take their positions. As we settled in with our M-16s pointed to shoot anything that moved, my thoughts momentarily reflected on the sudden feeling of the futility of it all for me. Here I am with only one week to go until finally getting back to the world of friends, girls and hot showers. Instead, we are going to be overrun and killed or taken captives for who knows how long under unimaginable conditions.

Suddenly the melee stopped and all was incredibly quiet. I was puzzled and prepared for the worst when soon we were all told by the battery commander to stand down and to go back to our regular assignments. It had all been a false alarm.

As it turned out, a new officer had arrived in the battery that week and was checking the flare guns at each of the guard towers. This process involved firing an illumination flare to insure the flare gun would work properly in the event of a need for its use. Unfortunately, the officer had inadvertently taken a cartridge from the red star cluster box rather than the white round. In so doing, he had signaled an attack, consequently sending the entire battery into an emergency battle mode and scaring the hell out of most of us.

I went back to my hootch very exhausted, but extremely relieved. In just one week, I would be “Back Home Again in Indiana.”

The song Back Home Again In Indiana was published in 1917, and while it is not the official state song, it may as well be. Since 1946 it has been a pre-race tradition at the Indianapolis 500.

Lieutenant Bill Cooper maintained that he picked up the wrong flare by mistake that night. Today he explains that he purposely shot off the flare signaling a ground attack to test the readiness of the battery. He had not told anyone of this exercise, and on reflection did not want to get court-martialed.

Going Home

When I processed out of the Army at Ft. Lewis, Washington they gave us counseling sessions, and in one of them this fellow told us the best states to live in because they paid the highest state benefits like unemployment. I thought that was interesting. I remember getting a new uniform and an overcoat. You’d never wear them again unless you were in the reserves. I wore the uniform home to Indianapolis, and never put it on again. I still have it, although I’d never get into it.

I got all the way back to Chicago without a hitch. I called my father to meet me at the Indianapolis airport. It was an evening flight, around 9:30. I had about an hour and went into this bar for a drink. I had just one drink and got to talking to this guy, and oh my gosh I got to get to my plane. I got to my gate and they had just closed it, so I missed the flight. I just sat in a chair until the next flight left in the morning. The irony of it all, I’m almost home after a year in a combat zone and I miss my last connecting flight.

March 9, 2016

Kim Martin – Fire Direction Control – Part Two

Just Out of Curiosity

Then we got a new battery commander. He was what they call a ring-knocker, a West Point graduate. He was one of those people, my impression was he definitely knew he was the battery commander and in a superior situation, but the way he over reacted to it made me think he wasn’t all that sure of himself. He was one of those people that wanted to be “with it.” He played his guitar to try to fit in, but he did not know how to communicate with people in general. He was not generally liked as I recall.

He was all about impressing important people. Some brass were coming into the battery and he wanted to make sure they were impressed with is administrative and military and disciplinary skill sets. He made sure everything was super cleaned up. We had to get used to not being so slovenly. We had to have much more spit and polish, and that kind of irritated everybody. He also had us make all these charts of ammunition usage, missions, and that kind of stuff. We had all these useless charts plastered all over the walls in FDC.

But the funny thing was, he was going to put on a tour for the brass. So for two days he would drive around in that jeep pointing to things. He was going through his presentation, but in the process he was driving around talking to himself. It was really a strange watching this guy. That’s how driven he was. He wanted to make sure he was down to the gnat’s ass.

I’m a pretty easygoing guy and try to get along with everyone, but for some reason I got a case of the ass about this guy. I decided I was going to push him a little bit. Looking back I realize it was both immature and not professional. But anyway, I knew how he was really big on military discipline, courtesy, formalities and all that. I heard him coming and I was operating the radio. I intentionally loosened my shirt up and turned around and put my feet up on the desk when he walked in. I was presenting an attitude of total casualness, and probably borderline disrespect.

Martin In his total casualness attitude

Martin In his total casualness attitude

In comes the captain, sees me sitting there and just blows up. He says, “Martin, sit up. You’re a disgrace to the military and to this battery.” He goes on and on reading into me. Then he storms out. We had a new Fire Direction Officer, a mild mannered nice guy, who was standing there along with two other people. Everyone was just jaws hanging down, they couldn’t believe it. It was so bad the new FDO said to me, “Look, I’m really sorry that took place. None of us feel that way. You do a good job.” Of course I put the captain up to it by doing what I did, just because I wanted to see what he would do. He was entertaining to me. You needed something to keep your mind entertained, and he was what you’d call a real trip.

I will say this for him, my last week at Sherry we all had to get a talk to encourage us to re-enlist and make a career of the Army. When I got called to the captain’s hooch I thought I was in trouble again, but he just wanted to give me the “re-up talk.” He was very professional about it and did a very nice job of it, even though I suspected he did not care for me.

Metro Marty

Here is how Kim picked up the nickname Metro Marty.

From Seven In A Jeep, A Memoir of the Vietnam War, by Ed Gaydos:

A computer the size of a baby rhino was another piece of advanced technology from the Pentagon. It was a Field Artillery Digital Automated Computer, or Freddie FADAC as we called it. In theory Freddie would compute firing data more quickly and accurately than our manual slide rulers, protractors and charts. But it needed a lot of attention, beginning with its own dedicated generator. With the flip of the power toggle it wheezed as it turned itself on, and when fully awake it let out a low, steady groan. If a computer could be constipated, that is how it would sound. The thing breathed out heat and made the FDC hooch even more oppressive.

Freddie doubled our work, because everyday we had to type in weather data, along with six-digit map coordinates for friendly nighttime positions and over a hundred fixed targets. For all the information in its circuitry, Freddie sometimes gave out crazy results. And it was slow, particularly when we had to run out to fire up the generator and wait for its blinking lights and digital readouts to come to life. We came to calling it that “Fucking Freddie FADAC” and wanted to haul it to the trash dump.

That’s when Charlie Snider in FDC stepped in saying, “We got orders to use it and somebody’s going to notice if it’s in the trash dump. We at least have to turn it on during fire missions. Top comes in here during a mission, it better be on. And as long as it’s on, we may as well try to make it work.” So Charlie spent half his career feeding numbers into Freddie. He had help from Kim Martin, a quiet guy who acquired the name Metro Marty for his patience with putting in the mountain of meteorological numbers of wind, temperature and humidity for every 50 yards of elevation up to the moon.

In the end we shot computer numbers when they were close to our manual calculations, and ignored them when Freddie gave out wild data or when the infantry was screaming for rounds in the air and Freddie sat blinking at us.

We took data from meterorloical reports and we just entered the data in the right fields in the computer. I don’t remember it being particularly anguishing. I think I did it to give me something to do in a way that contributed.

Corporal Patterson

This story involves a rather resourceful young corporal who as I recall was from Detroit, Michigan by the name of Patterson. I can’t remember his first name. We just called him Patterson. He was a very friendly guy who was one of those people that seemed to get along with everyone and befriended many. He also seemed to always be wearing sun glasses.

Patterson just managed to build his hootch next to the bunker where the battery flatbed truck was parked (a large five ton vehicle). They shared a common wall. The truck as I remember played an important role to transport supplies from our army supply post near Phan Thiet out to our battery. Now Corporal Patterson was very much into music, or jams as he called them, and managed to secure a phonograph. Every night he would mellow out listening to his music for many enjoyable hours. There is one very important item that needs to be known at this particular point in my story. There was no electricity available to our hootches. This came later. Only the FDC bunker and the mess hall had electricity then, and that was provided by two large diesel engine generators positioned behind the mess hall.

This however did not hinder the inventive Patterson. He was the only person at the time I recall who could play records, and that was a pretty big deal. So how did he do it? Actually the scheme was very basic. He simply ran wires from inside his hooch through the common wall, into the adjacent truck bunker, going up the front of the truck, and feeding into the truck battery. The system worked great. In the morning after getting up, he would just remove the wires.

Patterson continued this escapade for quite some time without being found out. The mechanic that took care of the truck could not figure out why the truck’s electrical system kept draining the truck battery every night. Funny thing is that when Patterson left to go back to the World, the problem disappeared.

I often wonder whatever happened to Corporal Patterson. He was one of those colorful characters that helped to make a very long year entertaining and endurable. I am glad he had been assigned to our battery.

Wrinkles

We called this little dog in the battery Wrinkles because every time she would look up at you she got this expression on her face that would cause her forehead to wrinkle up. Mike Leino is the one who named her Wrinkles. She would spend the night in different hooches, and every now and then she would spend the night in our hooch with Mike and me. Many nights Wrinkles would come in and curl up next to Mike’s bed. He really liked that dog and tried to take her home with him, but was not able to get that done. He had to leave her there and I guess it really tore him up because he was so attached to her.

Mike Leino and Wrinkles

Mike Leino and Wrinkles

March 2, 2016

Kim Martin – Fire Direction Control – Part One

Sixty Words A Minute

I graduated from Purdue in the summer of 1968. Knowing I was going to get drafted I had signed up for artillery Officer Candidate School at Ft. Sill. But first I had to go to basic training at Ft. Leonard Wood in Missouri, or as they called it: Fort Lost In The Woods. It was winter and that was something else. I remember on overnight bivouacs they told us to put our clothes inside our sleeping bags. The first night out I forgot and in the morning had to put on these cold, wet, icy clothes. Then we had to put cold water in our helmets and use that to shave.

I remember our drill sergeant as being a frequent smoker. When he stopped us for a break, he would put us at ease and announce, “Smoke if you have too, and if you have two, give one to me.” Immediately a volley of cigarettes would fly through the air at him from our formation. I don’t think he ever bought a pack of cigarettes during our time in basic.

After Leonard Wood I went to Ft. Sill for Advanced Individual Training in fire direction control, with the plan to stay there for artillery officer school. But there were a handful of us who got sent to Ft. Belvoir in Virginia for Combat Engineering. I don’t know why that was, maybe had to do with the fact that I graduated from Purdue, although I was not an engineering graduate. So the summer of ’69 I went to Ft. Belvoir, Virginia for Combat Engineering OCS.

Combat engineers built roads, bridges and air strips – often in remote, exposed locations.

There were three stages to the training, eight weeks to the first stage, and then eight weeks intermediate, and eight weeks of being a senior candidate. During that first eight weeks – here again I was a kid without a lot of sense I guess – I realized I’ve got to serve an extra year, and I’m gonna be out in the boonies in Vietnam without a whole lot of protection. The impression I got from people was you got sent out on these missions to build things with very little support. That didn’t make a whole lot of sense to me. I thought, I don’t think I want to do this. If I drop out of OCS I go back to my primary specialty of Fire Direction Control, which seemed like a better deal and I get out earlier. Plus the war was so unpopular it was hard to get my mind in the right set to serve as an officer. And I was not looking at the long term. During that first eight weeks you could choose to leave. Funny thing was that during those first eight weeks people were getting kicked out, and when I decided I wanted to leave they tried to talk me into staying. I did what they called “wimped out” when I left OCS.

Going to Vietnam we were in the air a long time and when we finally reached the coast I looked out the window and I was scared to death, not knowing what to expect. I’m looking down and thinking, Is this thing going to be shot out of the sky? I am looking for any antiaircraft activity or weaponry. Of course there wasn’t any. It was very tropical looking and I did see little artillery layouts in the clearings, you could see the guns. My initial reaction was one of concern for my personal safety and the safety of the plane. When we landed at Cam Ranh I was surprised at how big the airbase was. How sprawled out it was.

When I processed through Cam Ranh Bay, it felt like I was there forever, but it was probably for only a week or so waiting to be assigned. If you scored well on a typing test you could get a job as a Rear Rank Rootie and I could type sixty words a minute. When I was in junior high school, they had this award for typing sixty words a minute. All these girls were getting the award except for this one guy, and that was me. It didn’t do a bit of good however. Everybody who was a college graduate was trying to do that. They had more clerks than they knew what to do with.

Deluxe Accommodations

We flew into LZ Sherry on one of those helicopters they called a Slick (Huey helicopter – the workhorse of Vietnam), and the one thing I remember they kept the doors open. You’re sitting there with your foot about an inch from the door and you look straight down on the whole country side. Lot of jungle. A clear space every once in awhile with a military installation of some sort. I remember seeing a shrine, very old looking. I see LZ Sherry coming into view, and it looked like just a large slum. I thought, My god, I’m going to be here for a whole year?

When I first got there everybody was already situated, except for Lynn Holzer who arrived about the same time I did. We were the new guys. They assigned us to the FDC section chief, Harlan Hansen. He said, “This hooch right here is the one that belonged to the guy you are replacing.” I looked in, this hooch was half sunk into the ground, there had been a lot of rain and it looked like a swimming pool.

I said, “You got to be kidding me, I got to sleep in this thing?”

He said, “Well, that’s what’s left.”

I think I ended up moving in with someone temporarily. That was my first day at LZ Sherry – not the greatest welcome I’ve ever had. You’re on your own!

I ended up building a new hooch with Mike Leino, which turned out really great with nice paneling. After we got the shell built we stripped down some ammo boxes and made paneling for the walls. Then I got a blow torch and scorched the walls just enough to bring out the grain. It was really nice.

Mike Leino on a construction break

Mike Leino on a construction break

Kim in their new hooch

Kim in their new hooch

Note elegant paneling

No Trump

The battery commander was Captain Kevitt and I really liked him. He had been an enlisted man and then gone through OCS. He was career military. He had a good rapport and understanding of the people he was responsible for. He was a disciplinarian, but reasonable and not arrogant. He was a good officer. The men really respected him.

There were two guys in FDC that had been there awhile and had become really good buddies. One was Bill from Atlanta. He had been accepted into law school at Emory University while he was in Vietnam. The other guy, Fred, was the son of a career military officer. They were both pretty bright guys, well educated, and kind of knew it. Nobody wanted to be on their shift, so of course that’s where I ended up.

The captain liked to play bridge. The first day I was there he asked me if I played. I said, “I know how to play, but I’ve hardly played at all. But I know the rules, I know how it works.” So we decide to play bridge – the captain, Bill, Fred and I. I hadn’t realized it, but these two guys Bill and Fred were hugely competitive. They were bright, they were driven, and they had no use for idiots. Anyway, we’re playing bridge and I just screw up right and left. These two guys were both disgusted with me and from then on I was looked down upon as not on their level. Well, that was the last time I played bridge with them. They were nice guys, they weren’t rude or anything, but they sort of shunned me. That was the atmosphere. I was really glad when I got off their shift, but until then I kept to myself and read a lot of books when nothing was going on.

February 24, 2016

Dick Graham – PLL Clerk – Part Six

The Second Enemy

One night, with just a few days left on my tour, I was on guard duty in that tower near the main gate facing toward Titty Mountain. It was really dark that night. I think you remember when there was no moon in Vietnam, it was really dark, so dark the starlight scope in the tower was useless. We knew there was a possibility that the enemy might use CS gas on us because a Chinook carrying CS gas barrels due to engine problems had to drop its load. It was never recovered, and we were told to keep our gas masks handy.

CS is military grade tear gas. It burns the eyes and skin, causing its victims to shut their eyes involuntarily, vomit and fall prostrate to the ground with violent coughing, mucus discharge from the nose, disorientation, dizziness and trouble breathing.

That night, I thought I saw movement by the main gate. I called it in and was told that I couldn’t shoot because there was an ARVN unit on patrol in that direction. I kind of kept an eye on that area until I got off guard duty. I was back in my hooch when the thing went off. Someone yelled GAS when at the same time mortars started coming in.

Many thought the gas explosion and mortars were the beginning of a ground attack, picked up from stories about other firebase attacks. This night however, with illumination rounds now in the air and perimeter weapons lighting up the area with tracer rounds, that’s all the enemy had to offer, more of a tease and a harassment than a serious attack.

Captain Chuck Heindrichs, then battery commander, says of the incident, “The barrel to my recollection was set off outside the last row of concertina which would have been in the 100 yard range. The biggest impact was on the northwest of Sherry as we had a great concern for the old grandmother and the two kids in that area north of the FDC and without gas masks. Of course, after floundering around by almost everyone trying to find or dig out the gas masks, the gas had dispersed and only a few actually found and ‘donned’ their mask.”

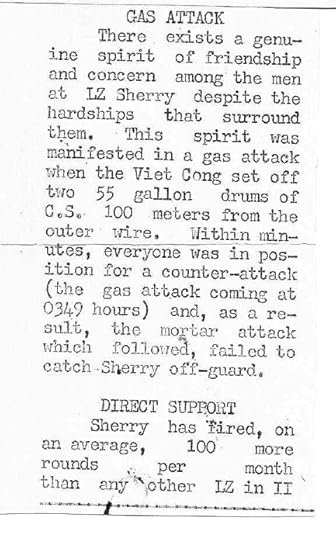

By LZ Sherry standards this was a minor incident, but enough for a flattering mention in The Artillery Review, a newsletter published by First Field Force out of Nha Trang, dated April 17, 1970. The article also gave a nice nod to the amount of artillery fire coming from Sherry compared to the rest of II Corps (Central Highlands).

Clipping courtesy Chuck Heindrichs

Clipping courtesy Chuck Heindrichs

The VC had rolled the CS gas barrels up near the main gate under the nose of an M-60 machine gun, a testament to their ingenuity, and proof of how dark Vietnam got that they remained invisible in front of an alert guard tower. On nights like that the dark was the second enemy.

Short Timer Crazy

Leaving Vietnam I had to turn in most of my equipment at Phan Rang. I remember when we got down to Tan Son Nhut Airbase outside Saigon how vulnerable I felt because I did not have a steel pot helmet, or flack vest, or M-16, and did not have sandbags over my head like I was used to at Sherry. I felt out of control, scared shitless, and absolutely paranoid. I did not sleep. Instead I sat up outside the barracks because it gave me more options in case of an attack. At Sherry when we got hit you could judge the pattern of the mortars as they walked across the battery one after another. When the first one would hit and then the second one, you got an idea of where the next one would be. I was used to that.

Little Things Take You Back

When I came home I struggled with fireworks. It was not the sound of the fireworks exploding, it was the thud when they went up that sounded just like a mortar round being fired from its tube. Most of the time when we got mortared we heard the thud when they were heading in our direction and well before they landed. You’d yell INCOMING and then if it was after dark you’d start shooting up the illumination rounds. That noise just told me I might get killed. I struggled with that for many years, and for years I never went to the fireworks display in our town. Now fortunately I don’t have an issue and I go with my grandchildren, but I think about it every time.

The same thing with helicopters. When I hear a helicopter flying by I equate that with a Medevac. I live in a small town and the hospital’s not that far from where I live, and most of the helicopters I hear are Medevacs. The sound has not changed over the years.

And certain songs, especially the one that starts with “Give me a ticket for an aeroplane.”

The Letter – released in 1967 by The Box Tops

#1 on The Billboard Rankings

Lead singer Alex Chilton was just 16 years old

Lyrics

Gimme a ticket for an aeroplane

Ain’t got time to take a fast train

Lonely days are gone, I’m a-goin’ home

My baby just-a wrote me a letter

The reason that stands out for me is I just wanted to get on that airplane and get back home. I’m not sure how high a quality a soldier I was because of my motivation. I did my Army job through a sense of duty to the guys with whom I served. I hated the Army; I hated every minute of it. In a letter to my parents after I made the rank of sergeant I said I couldn’t wait for my next promotion – to that of Civilian.

February 17, 2016

Dick Graham – PLL Clerk – Part Five

Mine Sweeping with Paul Dunne

Early on Paul Dunne and I got close because of our shared love for the ocean. (Paul was from Boston and Dick spent summers at the Jersey shore). The two of us volunteered for convoys into Phan Thiet because we could go swimming in the South China Sea. But to get there we had to mine sweep the gravel access road that ran from the battery out to the paved road that went into Phan Thiet. It took quite a while to mine sweep the access road. It was about two and a half miles long and there was a lot of shrapnel in the road mostly from fire missions that we had shot. When we got to the end of the road, to the bridge where Paul was killed, the bridge was made out of reinforced concrete so the medal detectors were of no use. We would visually inspect it. Then shortly after that bridge was the paved road going south into Phan Thiet, which we called 8-Bravo. You got on that and you just whipped right into Phan Thiet.

Period map showing LZ Sherry, access road running east to paved 8-Bravo, and bridge symbol

Period map showing LZ Sherry, access road running east to paved 8-Bravo, and bridge symbol

Three times I went on a mine sweep of that road. We just had a basic medal detector. My last time I went mine sweeping, I was using the detector and the First Sergeant, I think it was Ferrell, was behind me. He saw something that he said looked suspicious. We started probing with our bayonets and we found a mine. For the detonator they used bamboo sticks wrapped in tinfoil on the ends. They buried it deep enough so that if you walked on it you would not set it off, but if a truck went over it would go off. They used a six volt battery (the old square lantern battery) for the power source off to the side of the road wrapped in plastic. It was really ingenious! The amount of time it must have taken them to dig that hole, put that 8 inch round down there, and put the detonation mechanism together must have been many hours. The only thing that the metal detector could pick up would have been a few small wires buried several inches below the road surface. We blew up the mine with some C4. The hole it left was large enough that when you jumped down, you couldn’t be seen from the surface. That was the last time I volunteered to mine sweep the road.

After that we did not run convoys for a long time. I remember we had the First Cav for awhile working around Sherry. Their way of sweeping for mines was to run three tanks down the road, with the tracks of the outside tanks in the ditch. They guy I really felt sorry for were the ones riding around in those armored personnel carriers, which was like riding in a pop can. Those guys really took a lot of casualties.

When Paul died, that ripped me apart. It was almost like a part of me had died. It was like there was an emptiness in my soul! I just remember seeing the jeep they brought back and all this sadness.

Picture courtesy Andy Kach

Picture courtesy Andy Kach

And then you get mad and think, Fuck it. It don’t mean nothin’. And you move forward. When Rik got wounded, I was right there with him. And then when Paul got killed, I think I did it unconsciously, I tried not to get close to anybody else, so I would not have to experience that hurt again. As a means of survival. After Paul died I don’t remember being close to anyone else there.

Paul Dunne

Paul DunneI wrote a letter to Paul’s mother after he was killed, because I suspected she did not know what had happened because the Army never told the specifics. I wanted let her know what had happened, and my relationship with him. She sent me a thank you note with a holy card from his funeral with his picture that I still have.

The R&R That Wasn’t

While I was at Sherry we built an EM (Enlisted Men’s) club. They had a contest to name it, and I won the contest. I presented a lot of names. The winning one was The End of Mission Club. For winning the contest I got an in-country R&R to Vong Tau. Hardly anybody got in-country R&Rs.

I took a helicopter from Sherry to LZ Betty at Phan Thiet. From there I flew north to Phan Rang, from there I flew south all the way down to Saigon, and from there out to the coast to Vong Tau. The in-country R&R place right on the South China Sea was supposed to be pretty nice. But nobody told me I needed orders to get in. Once I got there they wouldn’t let me stay, because I did not have orders, so I had to go back to battalion headquarters in Phan Rang. I was pretty pissed off!

In Phan Rang I met another guy who was in some trouble with one or two Article 15s against him, and we decided to go into the city, which was definitely off-limits to GI’s. I don’t remember how we got past the MP’s, but we went to a bar, drank some Tiger Piss beer and met some girls. So much for my in-country R&R.

Americans called the local beer, Ba Muoi Ba 33, Tiger Piss, and suspected it contained formaldehyde. Dick’s End of Mission club, located behind Gun 2, later became the Fire Direction Center.

The R&R That Was

I went to Sydney, Australia for my real R&R and checked into one of the hotels on the list the Army said we were supposed to stay at. The first thing I did was take a bath. It was nice to have hot water and I sat there for an hour or two. I was amazed at now dirty the water was when I got out. I did not think I was that dirty.

Sydney was a beautiful city, about four million people. I couldn’t believe how clean it was, very unlike New York City. They were just starting to build the opera house that is now so famous. I had a wonderful time there, oh my gosh, I was ready to move there.

I rented clubs at the R&R center and went out on the golf course. It was just beautiful. You could see the ocean. On the golf course I met a couple guys who were in the construction business there. They were very gracious. They spent a lot of time showing me around and taking me to clubs. They told me I was in the wrong hotel. They told me to move to this other hotel which I did and which was right on Bondi Beach. It was gorgeous as was the beach. Most of the other guys who went to Australia spent all their time at bars where all the GIs hung out. I got to experience a lot of the culture there. And I finally got to talk to my parents over the telephone. It was great!

Coming back to Sherry, I had 77 days left. I was a short timer.