Ed Gaydos's Blog, page 5

July 6, 2016

Joseph DeFrancisco – Battery Commander – Part One

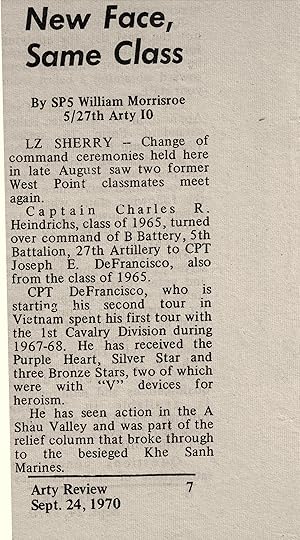

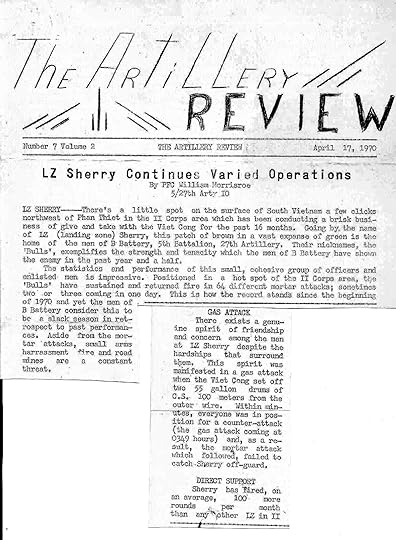

Captain Joseph DeFrancisco took command of B Battery from Captain Chuck Heindrichs, a West Point classmate, in August of 1970 . The next month this article appeared in the Artillery Review.

West Point

I grew up in an era in which most of the adult male members of my family had been in World War II. That was a defining moment for those folks and they talked about it. I wouldn’t say they dwelt on it, but there was ample conversation about their experiences in World War II. And then growing up, born in ’42, I started going to movies in the early ‘50s and there was just a plethora or World War II movies. To serve your country, at least in my community and in my mind, was a very noble thing. I grew up surrounded by those sorts of ideals and those sorts of influences. None of my relatives had ever gone to West Point. In fact very few of them had gone to college, so West Point was the epitome if you were going into the military.

I was living in Albany, New York, which is only two hours north of West Point, when the opportunity became available. I decided to try for it, and went to West Point. And that began my career. I went into the Academy in 1961 and I left active duty in 1998. My whole adult life was devoted to service to the country.

I entered West Point in the middle of the cold war and only six years away from the Korean experience. I did not know anything about the Army, and of course during my four years at West Point I did not learn a great deal about the Army either because I only saw one little piece of it. When I graduated I selected the field artillery branch because the instructors I admired most were field artillerymen. And most of the experiences I had in visiting other installations – and we visited a lot, to include the homes of all the branches – I was most impressed with artillery. That’s how I selected field artillery: not very scientific, but that’s the way it all began.

Cadet Joseph E. DeFranciso

Cadet Joseph E. DeFranciso

Remember Field Artillery was not a separate branch back then. The branch was Artillery, made up of Field Artillery and Air Defense Artillery (ADA encompassed the Dusters with their twin 40mm cannons, Quad-50 machine guns, and searchlights). An officer was expected to be able to go to field artillery or ADA. My preference was always for the howitzers of field artillery.

Germany

Out of West Point it was mandatory that we attend Ranger school. Vietnam was starting, so the powers said, OK, we’re going to have all you Regular Army commissioned officers go to Ranger school. Unfortunately we were not authorized to go to the officer basic course in artillery. The idea was you’d pick up what you needed to know about artillery when you got to your unit.

After Ranger school I also went to airborne school, got married, and went off to my first assignment in Germany, to a field artillery battalion.

I got to Germany New Years Eve of 1965. I was astounded at the low level of the quality of training and the character of the leadership. It was far below what I expected. It may have been a function of the unit I was in, I did not know. It was a Corps artillery battalion, not assigned to a Division, that also might have made a difference. There were very few high quality officers or NCOs.

There were a lot of officers in that battalion who were reservists, called to active duty for the most recent Berlin crisis and then decided to stay. In those days – I don’t want to say bad things about the reserves because now Army Reserves and National Guard are an integral part of the Army’s operational force – but in those days there was a huge quality difference between the reserves and active duty.

When I arrived the battalion was full; they did not even have a slot for me, so they made me a commo officer. Three months later I was acting battery commander, because the battalion had been denuded of officers due to the dramatic ramp up in Vietnam.

At that point we were down to five officers. You can imagine the level and quality of leadership, and everything that goes with that. Two of my senior NCOs and one of my superior commanders were alcoholics. Sergeants went around sucking those candies filled with liquor. It was awful.

This assignment was supposed to be for three years, but luckily I was there for a brief period, only four months. Because of Vietnam the Army decided to pull two thousand artillery lieutenants out of Germany to populate the basic training centers opening across the United States.

I went to Ft. Bragg and became a basic training officer, teaching subjects such as marksmanship, customs and courtesy of the service, military law, the basic implications of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, drill and ceremony: all those things that are necessary for discipline and cohesion in the unit. I did that for nine months.

First Vietnam Tour – A Heavy Year

I went to Vietnam a field artillery first lieutenant in June of 1967, well before my time at LZ Sherry (August 1970). I spent my entire tour, a full year, with the First Cavalry Division. I joined the 1st battalion of the 21st Artillery at An Khe and went immediately up around the Kontum/ Pleiku area, which is in the highlands in the far western part of South Vietnam. After spending about five months in the battalion headquarters I was reassigned as the Artillery Liaison Officer to 2nd/7th Cavalry. It was during that time that I saw some pretty serious fighting and I got into some pretty heavy stuff with the First Cav, all a part of the TET Counter Offensive. There was the Battle of Hue. Then there was the relief of Khe Sanh, and then shortly thereafter was the incursion into the A Shau Valley. During those times I lived, worked, slept, ate, and fought with the infantry all the time. I rarely saw my artillery battalion commander, I never saw my battalion headquarters. I was with the infantry all the time.

My first job brand new in country was headquarters battery commander, a tough and thankless job. You’re basically the housekeeper. I remember my First Sergeant, a wonderful man. He helped me a great deal to keep things in perspective, and was a great help on the convoys we had to run. Our longest convoy I lead was from the Pleiku area in the western part of the Central Highlands to the Bong Son Plain on the coast of the South China Sea. I had just read Street Without Joy before going over to Vietnam. The book includes the story of a very famous ambush on Highway 19, the east-west highway across the central highlands through the Yang Mang Pass, where the Viet Minh wiped out an entire French column. My convoy went right through there.

See George Buck’s stories – who was a Duster platoon leader in that area about the same time and also ended up at Sherry, but before Joe’s time.

I went over there to fight, very young and idealistic, and all of a sudden I’m at a headquarters battery. This was not what I want to do so I volunteered to be an aerial observer and a forward observer, every now and then going out with South Vietnamese units. I spent a great deal of time learning how to adjust artillery and call in fire commands. Remember there was no artillery basic course so this was my first time learning all this. As an aerial observer I literally learned artillery on the fly.

Then I became the fire support officer, then called Artillery LNO, for the 2nd/7th Cav and that’s where I learned fire support coordination. I was responsible for all the fire planning, preparations for troops coming into LZs, and maintenance of defensive targets for various LZs and base camps.

During what was called the TET ’68 Counter Offensive we moved up to Camp Evans in the central highlands in the center of Vietnam. Evans was the 1st Cav’s Division headquarters fifteen miles north west of Hue. We flew out of there to go into the area just outside of Hue, then to relieve the Marines under siege at Khe Sanh to our west at the northern end of the A Shau Valley, and eventually to support the A Shau Valley incursion.

Hue

At the beginning of the TET Offensive in the early morning hours of January 31, 1968, a division-sized force of North Vietnamese and Vietcong soldiers launched a coordinated attack on the city of Hue. It would be one of the longest and bloodiest battles of the Vietnam War lasting almost a month. The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong lost 13,246 killed. South Vietnamese killed: 452. U.S. killed: 216.

Did some fighting around Hue after TET of ’68. I was never in Hue City itself. Instead the 2nd/7th Cav and other elements of the 1st Cav’s 3rd Brigade conducted operations around the periphery of the city. We did get into some heavy contact. At one point the fighting became so intense that some of our direct support units ran out of 105mm ammunition. At least one FO had to use naval gun fire from the battleship New Jersey, which was off-shore near Hue, to support ground operations. As any FO will tell you, this not an ideal situation given the range dispersion of naval guns.

June 22, 2016

Chuck Heindrichs – Battery Commander – Part Eight

Pants Optional

We had this ten round rule. When a mortar attack came you stayed under cover, but after ten mortar hits you had to come out on the guns because it could well be a ground attack disguised as a mortar attack, and then you’ve got Bangalore torpedoes and hand grenades coming at you.

This rule to stay under cover during the first wave of mortars came about from the heavy casualties suffered at Sherry during the previous summer of 1969, when crewmen manned their guns at the first mortar.

I remember the mortar attack starting. I threw my flack vest on, I threw my belt on with my .45, I put on my helmet and my boots, which were not laced, and I came running out of my hooch. I look over and see Sergeant Kelly, a big guy E-6 gun chief. He’s coming out of a hooch with two young soldiers by the back of the neck in each hand dragging these guys onto the gun and he’s yelling, “That’s the tenth round, we’re out of here.” He looks over at me and laughs. I must have been a sight in my untied books, my belt and .45 pistol, my flack vest, my helmet, and ready to fight … in my underwear. He tells me later I looked like the funniest thing in the world.

NAAPTBA

A crazy colonel at First Field Force Artillery in Nha Trang imposed a motto on us: Not All Are Privileged To Be Artillerymen, I guess to send a message to the infantry. My battalion commander, Colonel Carl Beal, said this guy is coming down in a couple weeks and we’ve got to get that up on signs. So we make all these signs with NAAPTBA on them.

The signs were scattered around the firebase where the colonel was likely to see them, including one outside the wire facing the chopper pad.

Not surprising the motto did not catch on. The signs persisted but in short order most of the people on the firebase couldn’t tell you what the letters meant.

Singing In The Rain

Our showers were from fifty-five gallon drums filled with water on top of a rickety frame. The water never lasted very long, especially when it had heated up a bit from the sun and was nice and warm. During monsoon season, when heavy rains came every day at almost exactly four o’clock PM, there was a daily bathing ritual with unlimited water.

Gun crews would fashion the canvas covering on their hootches to channel water into a small waterfall. We discovered that by taking Styrofoam and pouring gasoline on it, it would become a liquid for a few minutes and would then harden. It was normally used to repair leaks, and in this case to make a rigid water channel.

It was strange to the untrained eye to see soldiers standing around in the late afternoon under a hot sun with a towel, washcloth and a bar of soap in hand. Sure enough, the rains would come right on schedule, and the battery was replete with folks singing in the rain while taking a shower.

Sherry Hospitality

An American armored infantry platoon was patrolling through our area. They came into the firebase; we fed them and told them they were more than welcome to spend the night. Their lieutenant said, “No thanks. You guys get hit too much. We’re going out and set up five hundred yards away.”

We said to him, “Whatever you do, and however you operate, please do not put up a red flare.” A red flare meant a ground attack to us and triggered an automatic mad minute, firing everything we had and saturating the entire area around the firebase. Well that night someone in that infantry platoon did something that put up a red flare, and of course we cut loose.

The lieutenant came into the firebase the next morning. They had fortunately been inside their armored tracks. But they were right in front of one of our Quad-50s, which shot their vehicles up pretty good, including destroying their radio antennas. I was surprised we didn’t kill anyone.

The Gibson Jumbo

Before leaving Nha Trang to take command of Sherry, I stopped at Special Services and signed out a Gibson Jumbo 200 guitar. I wanted to bring the guitar because as a commander you always want troops to kind of like you, that you’re not just another officer coming in. You want to have some endearing attributes. I thought they might enjoy that the old man can play a couple of chords.

At the end of my tour when I got ready to turn it back in, the Special Services offices in Nha Trang had already been closed. So I left the guitar behind at Sherry for the next person. Part of me regrets leaving such a beautiful guitar behind; today it would be worth something. But I did not have the heart to take something that did not belong to me.

An Ear Inside The Fire Direction Center

Chuck ends his stories with something special, a recording taken inside the Fire Direction Center probably sometime the first half of 1970. It captures the chatter associated with a routine fire mission. Mid mission the battery comes under a mortar attack and a siren sounds bringing everyone to battle stations. The distinctive sound of the siren alone, not heard these many years, will bring a fresh chill to any guy who was at Sherry.

A cassette recorder was somehow on in FDC during a mortar attack. Unfortunately I don’t know who gave it to me or when exactly it was made. You can hear the normal talking going on for a routine fire mission, with FDC figuring up the firing data and sending it to the guns, and all of a sudden you can hear someone yell, “INCOMING.” And then you can hear the siren go off and increased activity. I am not sure anybody would understand what was going on who had not been through it; you wouldn’t know what the various sounds mean.

Below is a sound file of the recording. The recording requires that you listen carefully. Remember it was made almost half a century ago on a primitive cassette recorder, one no doubt plagued with dust and mildew. Before clicking on the sound file it would be helpful to have some hints of what to listen for:

FDC personnel computing, checking and sending firing data for a one-gun fire mission (Gun 1)

Someone announcing INCOMING in the background

The siren going off alerting the entire battery to an attack

The Dusters and Quad-50s in the background saturating the perimeter, in the event of a ground attack

FDC personnel figuring up counter-mortar firing data involving the entire battery of six guns, two rounds each

Eight rapid bangs which sound like a Duster. It may have honed in on the mortar site from the commands to the guns

BATTERY FIRE command, followed by the almost simultaneous sounds of all the howitzers firing. The recording ends before the second volley.

Note the calm, efficient atmosphere even in the course of the mortar attack

To Listen Right Click on the external link below, and select Open Link .

Let me know if this does not work for you. I will send you the link within an email.

June 15, 2016

Chuck Heindrichs – Battery Commander – Part Seven

Hi Ho Silver, Away!

In the middle of the day we heard this huge explosion to our east probably two hundred yards beyond the creek that crossed the access road. It was obvious somebody was putting a mine into the road, which happened a lot, and it went off. So we called Phan Thiet and immediately they sent out one of these cowboys in a little Loach observation helicopter.

Loach OH-6

Loach OH-6

The Loach was often part of a high-low team. A heavily armed Huey helicopter would be high, and the little Loach would fly low to draw fire and in would come the Huey. So here comes this guy in a Loch, but all by himself with no other helicopter. He drops onto the pad and says, “Where in the hell are the bastards?”

I get into the Loach and we fly in the direction of the explosion, and we could see this hole where mine went off and three bodies laying there. We also saw two or three other guys run toward that creek line. The pilot pulls out his .45, I pull out my .45, and he flies the Loach right up to the wood line and cruises along it ten feet above the ground. We flew up and down the wood line, and up and down the creek bed, and the whole time I’m thinking, We’re sitting in a glass bubble with a blade on top. If there’s a guy below us with a machine gun our .45s aren’t going to help much, we’re gone. What is wrong with this picture?

Navy Duds

Sometime in June 1970 a U.S. Navy destroyer off the coast of Phan Thiet invited us to come out to the ship and observe what they were doing. Unfortunately on the scheduled day there was a terrible storm and fog and the visit never happened.

In any case, they were doing experimental firing with a JATO round (Jet Assisted Take Off ) and wanted LZ Sherry to observe the impact of the rounds. JATO was a round that had a sort of rocket assisted take off mechanism. It was supposed extend the shell’s range by some five miles or so. We mutually picked a time, about two o’clock in the morning, and established a communications protocol between us and the ship. The concept was that they would tell us when a round was fired and we would listen for the explosion and perhaps even see the impact burst and be able to confirm some level of accuracy. The rounds were targeted some one to three miles from LZ Sherry.

On the first round we heard a thud when the thing hit the ground, indicating it had not exploded. The same thing on the next two rounds; all we heard were thuds. We suggested to the Navy that we would probably see these rounds on our roadway in the form of land mines. Experiment over.

Over one hundred and thirty Navy destroyers saw action in Vietnam, many of them equipped with guided missiles, and no doubt experimental weaponry of all kinds.

A Minor Mistake

At two o’clock in the morning an eight inch howitzer round from LZ Sandy exploded in an airburst right over the firebase. I came out of my bunker with my flashlight and saw the most eerie looking thing. From the ground up there was a three foot dust cloud everywhere I looked. It was like you walked out into a fog rising from the ground. I remember getting on the command net and yelling CEASE FIRE for anybody and everybody to hear, because I had no idea where the round came from.

Nobody got hurt, and no one realized until maybe midday when they looked at their trucks that something had happened. My jeep had a huge hole where a piece of shrapnel went through the passenger seat and right on through the bed of the vehicle. All of our vehicles were in sandbag revetments so there was not a great deal of damage.

I never learned what happened because I never made anything of it. I did not want to see a guy get fired. Sandy was probably firing Harassment and Interdiction and somebody fired out. If I had made something of it there would have been a full bore investigation, and I did not want to see somebody’s career destroyed because somebody on a gun or in FDC may have made an error.

Bones

There was one incident that gave me some little insight into the Buddhist religion. The engineers at Whiskey Mountain had agreed to fly in a little bulldozer to reconfigure the berm because we had some water pooling during the rainy season. The bulldozer was pushing sand around and all of a sudden it turns up a skull and some bones. Mama-san and the two young boys were out working in front of the mess hall and saw what happened. The kids got frightened and ran back to their hooch they shared with Mama-san. I learned from our interpreter that in the Buddhist religion once you bury someone if you open the grave up the spirit is released and makes trouble for the living. We ended up flying Mama-san and the kids off base for four days until we finished pushing dirt around.

In May of 1968 the battery built LZ Sherry on top of a cemetery due to its slight elevation over the surrounding rice paddies. The above ground devotional structures typical of Vietnamese cemeteries were eventually cleared away for security reasons. By the time Chuck arrived at Sherry all vestiges of the cemetery had passed away, along with the knowledge it ever existed.

Vietnamese cemetery outside Phan Thiet

Photographed from a low flying helicopter

Every month we sent money to a monk for the boys’ education. Of all the questions I have about Vietnam, Were those kids in the aftermath of the war ever able to use that money, did they ever become successful?

Following the defeat of South Vietnamese forces civilian casualties were horrific, so extensive that the best estimates are rounded to the nearest ten thousand.

100,000 died fleeing he advancing North Vietnamese Army

170,000 died in re-education camps

150,000 perished in forced labor camps

200,000 were simply executed as collaborators

From R.J. Rommel, Vietnamese Democide: Estimates, Sources, and Calculations, 1997

In the wake of these numbers the odds for Mama-san, the two boys Slick and Wan, and the several other Vietnamese civilians who worked at the firebase … were not good.

June 8, 2016

Chuck Heindrichs – Battery Commander – Part Six

Hi-Tech

We got visiting delegations regularly because of the general prominence of LZ Sherry. We were a model firebase and the brass liked to show us off. As a result we also got lots of experimental hi-tech gear for its time.

Early in 1970 the war was winding down. The last armor units were drawing down and other deactivations were proceeding. But LZ Sherry still was quite active, by the number of mortar attacks we received and intelligence that VC units were still active in the area. North of us was an infiltration route that ran north of a railroad line that was part of the national railroad running the length of the country. The railroad was elevated somewhat, allowing foot traffic behind the track without being detected. Our TPS-25 radar (ground surveillance radar) would scan this area all the time because at some point the VC would cross south and set up mortar launch sites.

It was decided at some high level that we would install a motion sensor field in the area north of the base. The installation was done with an 81 mm mortar along with a number of special rounds and firing tables. These rounds consisted of the normal fins and propellant bags. But when dropped into the mortar tube, its nose was only two inches below the top of the tube. When it fired off our Q4 counter mortar radar tracked its trajectory in order to confirm its exact ground location.

As the round impacted its performance was somewhat complicated. The head of the shell would go into the ground and immediately detach from the tail, but remain connected via an umbilical cord that provided battery power to the tail assembly. Then the tail section would deploy a set of large fins called a terra break, which would cause the tail section to stay even with the ground. At the same time a gas driven antenna would rise, looking like another weed or piece of grass.

Back in the Fire Direction Center there were monitoring devices that would receive a signal from a sensor that it had deployed successfully. Each sensor had its own number that appeared on the FDC monitor. I believe in all we had six units spread out in linear fashion for several hundred yards.

When it all worked, the scenario that played out was straightforward. When a sensor detected motion its monitor would light in FDC. If the next sensor lit up, that would indicate something moving in a particular direction. After more sensors lit up, we suspected that a group was moving through the area. And when the series of sensors stayed lit we could make conclusions as to the number of people moving through the field.

We gave each sensor a code: BLACK WIDOW ONE, BLACK WIDOW TWO, and so forth, then figured up firing data for each of the device locations. When one of the devices detected movement FDC had only to send a simple BLACK WIDOW command to the guns for them to fire immediately. The advantage was speed, because the VC were not stupid. When they were out there they could hear settings and firing commands shouted to the gun crew, they could hear the crews loading the breech. With Black Widow there were no drawn out commands – just one quiet instruction to the gun and BOOM the round went out. Of course we never knew what we were shooting at or got confirmation of any enemy kills. And we never knew how many water buffalo we killed.

Sometime following the placement of the Black Widow sensors, we were also given sets of PSIDs or Personal Sensor Intrusion Devices. These devices measured ground vibration and were placed by hand around the fire base at a distance of about three hundred yards, or as far as we cared to venture out. I believe our battery XO, who loved playing infantry and got excited about this kind of stuff, took charge of the job. Like Black Widow these devices also transmitted a signal to monitors in the FDC. We may have had an occasional hit with one of them, but attributed that to mice and other critters out there. Of course during heavy monsoon rains and heavy winds they were going off all the time. Most of the time we did not waste the ammo.

Lo-Tech Is Sometimes Better

We were used to being mortared from the north and used to the road heading east being mined. With all the air traffic between Phan Thiet and Sherry, someone noticed people digging a possible mortar emplacement in a different direction south of us. That area was a free-fire zone at night, which allowed us to blanket the area without any special fire mission approvals.

We later learned that we had destroyed a mortar unit and had killed a number of enemy troops, and that the mortars and ammo had been abandoned on the site. It may have been the first time we got feedback on destroying a mortar site. Between the intel and our howitzer fire, we nailed it.

Life and Death On One Stage

Here’s one of my favorite stories. A couple of helicopter pilots who flew for a general would sometimes stop by our base for lunch. One of them pulls me aside and says, “How would you like it if we brought a show to your firebase, some girls and a band? It’ll cost you six hundred bucks.” I go to the First Sergeant, because I did not handle the slush funds, and he gives the pilots the six hundred bucks. We schedule the show five weeks out on a Sunday afternoon at two o’clock, to be held on a specially built stage next to that half basketball court outside FDC.

Stage under construction – supervised by small dog

Picture Courtesy Kim Martin

After I agreed to have the band come in, a command-wide ban came down forbidding assemblies to watch movies or entertainment of any kind. Apparently there had been an incident, either a mortar attack or a fragging on people waiting to get into a mess hall. So they came out with this directive. I’m kind of nervous but I am still going through with the show despite the directive.

A week before the show an infantry unit has a kid get killed in a firefight up north of us, in an area we got mortared from all the time. So our battalion commander calls me up and says, “They are going to have a memorial service for this kid that was killed, and it’s going to be at your firebase on Sunday at four o’clock.”

I thought, Oh shit.

So that Sunday at one thirty here come two helicopters with the band and two French Vietnamese girls. The band sets up on the stage, and the little back room in the Fire Direction Center becomes a changing room for the girls to get into their costumes. All the troops set up on boxes and chairs by the stage, and a lot are standing. The infantry troops, about forty guys, had already come in and were there too. The show went on with the music and the girls going through the crowd topless and sitting on laps. It was a hilarious afternoon.

But I am not personally enjoying the show. I’m standing out by my hooch with the chief of firing battery looking at the sky hoping nobody of any rank decides to drop in to see I am violating the rules of assembly. And I am looking at the clock. It gets to be three fifteen and I walk out and indicate the show has to stop, and you need to get the band and girls on their two helicopters and get them out of here.

We load them up and get their helicopters off, and from that point everybody is sworn to secrecy. Sure enough ten minutes later here comes the infantry battalion commander and his entourage of three helicopters. The chaplain sets up a memorial ceremony right at the same location we had been watching these girls put on a show. I thought, If this isn’t crazy. At two o’clock you’re watching a rock and roll show and girls doing a strip act and fooling around with the guys, hugging and kissing them and taking their hats to rub on their boobs, and an hour later on the same spot we have this very somber memorial service for a young man who had been killed. That was one of my most nervous days in all of Vietnam.

June 1, 2016

Chuck Heindrichs – Battery Commander – Part Five

How Things Got Done In Vietnam:

The Generator Story

One of the more interesting stories, we used to have this Air Force sergeant in charge of our supply logistics at Phan Rang. He wanted so bad to come out to the firebase to experience a mortar attack in combat. This guy was a nut. So the battalion commander brought him out. “This guy does us a lot of favors and just wants to come out and be with you guys.” So he stayed about four days and we had one mortar attack during that period. He thought that was the most exciting thing.

About two weeks later we get this call from Phan Thiet that they are going to bring in a supply run and they had some special boxes for us. The supply chopper arrives and they drop all this stuff off at the pad, and here’s these M60 tank Xenon searchlights, one of which we mounted on the back of a jeep.We’d drive the Xenon on the jeep around the perimeter at night. Plus it had infrared capability. If you had enemy sneaking up on you, you could see their infrared signatures.

Xenon Searchlight

Xenon Searchlight

The Air Force sergeant gives me this long lesson about the eye of a deer and a human being. If you run the Xenon light and you see a bright white pinhole off in the woods and it does not disappear, that’s an animal. It has to do with how the eye of an animal is designed and how the light reflects off the back of its eye. A water buffalo or any other animal is going to stand there and stare at the light and freeze. If it’s red and it disappears it’s probably a human being, on account of how the human eye is built. A human upon being spotted, on account if how the human eye is built, is going to show up red and then disappear.

Then this Air Force sergeant comes out a month later and says, “I have a mini-gun for you.”

The very gun mounted in the AC-130 gunships, and also mounted in attack helicopters and larger ground vehicles.

In love with his mini-gun

In love with his mini-gun

I said, “No, that’s not gonna happen. We may have problems out here but I don’t want somebody sitting up in a tower or bunker with a mini-gun.

Then he comes back with, “I know in your Fire Direction Center you have two little 10 kw generators. What would you say if I sent you out a 30 kw generator?” And he sent the damn thing out!

30 kw generator – the size of a water buffalo

30 kw generator – the size of a water buffalo

And he sent us more lighting and wiring. This was the only time I used my electrical knowledge. The 30 kw was a three-phase generator, and I actually sat down and diagrammed all the wiring on the base so that we would balance out the three phases.

Initially the generator just sat there because I couldn’t get the First Sergeant to get the wiring trenches dug to the hooches around the firebase. Finally one night I said to him, “Top, I am really concerned about the 10 kw generators in our Fire Direction Center, because you know those things only have so many hours of life and then they’re dead. We’ll probably have to arrange for some periods during the day when we just don’t have the generators on.”

I knew that the refrigerator in his hooch where he kept his cold beer was hooked to one of those 10 kw generators. I said that to him on a Wednesday, and on Thursday morning at six o’clock this young kid is beating on my door yelling, “Sir, where do you want your wiring run?” I look outside and there’s like eighty beavers digging trenches all over the base.

The Demo

We’ve got this delegation from the Pentagon and from Ft. Sill coming out to see live fire demonstrations of defending a firebase, and they especially wanted to see a demonstration of the Firecracker round.

An airburst round that ejects bomblets high in the air, which then open fins and float spinning to earth. The fluttering fall has the appearance of a butterfly in flight. Upon impact a spring on the bottom of the bomblet throws it back into the air where it explodes at about six feet. The bomblets detonate with the energy of hand grenades. At a distance the quick succession of explosions sounds like a string of firecrackers. The 105 mm howitzer version carried eighteen bomblets. The Firecracker was effective against enemy in the open, or in positions without overhead protection.

Unfortunately the bomblets sometimes did not explode when they landed in rice paddies. They would explode later when kicked by someone wading through the flooded field.

Twenty minutes before the delegation arrived we also shot up some test Firecracker rounds to make sure in the live demo the ordnance would come down where we thought it would.

We also had a howitzer wheeled up on the berm to fire a Beehive round, because we intended to show the delegation everything we had.

The Beehive round contained eight thousand fleshettes, and was fired like a shotgun directly at enemy during a ground attack.

Fleshettes recovered from a Beehive round fired in 1970

Fleshettes recovered from a Beehive round fired in 1970

And we planned to show them a High Explosive airburst just over the berm, where you bore site the tube and fire the round with just 3/10 of a second on it. We picked the gun that was going to do it and made damn sure it was bore sighted the way it should be.

Here comes the delegation of ten or twelve people: Pentagon desk jockeys, female officers from Ft. Sill and a handful of neophytes. I was surprise and pleased to see that one of them was my old commanding officer in my old Honest John rocket unit in Europe. He was a full bird colonel and the most unpleasant guy you could possibly imagine. Everybody hated him, but at the same time everybody loved him because at least he was predictable. His last name was Hackaday and everybody called him The Hawk. I was his HQ battery commander for five months, the most unfulfilling job I ever had. (Headquarters battery jobs involve administrative housekeeping.) Now The Hawk and I could share some laughs.

We start with a little show of bravado giving them all steel pot helmets, like going on a construction site. We walk around the firebase briefing them as to our role, where the Viet Cong are in our area, and all that phoo phoo.

Then we start the live fire demonstration with the Firecracker. We take them to the east end of the firebase near where the road leaves the base. Just over the berm and near that access road is where the Firecracker round will detonate. We explain the use of Firecracker in the self-defense of an artillery firebase, and draw their attention to the guns behind them, at the west end of the firebase, pointed in what appear to be straight up into the sky ready to fire. I move them all over to the berm close to where the Firecracker round will drop its load and instruct them all to look out. I give the XO the signal, and he fires. We’re watching the little bomblets floating and spinning down close to us, and you could hear this one guy go, “Oh my god.” I tell them all you might want to duck down a little bit in case one of them doesn’t quite go where it’s supposed to. Of course we had just fired a practice round before they arrived. They were astounded with the explosions just on the other side of the berm, basically a bunch of grenades going off.

Then we walked back to the other side of the firebase where the guns were located to demonstrate the timed airburst just over the wire. We’re on the inside of the berm looking back at the gun. It’s a little scary because that round is going over the berm not much more than two or three feet. We fired that thing and it went off about 50 feet past the berm. None of them had ever been that close to an artillery round going off. They may have seen fire demonstrations at Ft. Sill, but it would have been from the bleachers. I had told them that when an artillery shell goes off in an airburst most of the shrapnel goes straight up or forward, but some of it is going to come back so you may experience a little of that, and sure enough when the round exploded small pieces of shrapnel were raining down on them.

Then we fired the Beehive from the gun on top of the berm. I think they got what they came for. It was glorious!

Scaring visitors was one of the delights of serving at LZ Sherry.

May 25, 2016

Chuck Heindrichs – Battery Commander – Part Four

The Sniper Who Couldn’t Shoot Straight

We had a sniper out to the west. A new battalion commander, it might have been Colonel Beal, flew in, landed on the pad. The helicopter shut down and we’re just standing there talking. I said, “This is not a good place to stand because over there in that wood line is a sniper. He doesn’t hit anything, but he bothers us a lot.” All of a sudden you heard this little whisp into the ground about six feet in front of us. I said, “Yeah, there he is again.” We walked away calmly, because the guy never hit anything.

The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight

This is one of the all time funny stories, involving all the military firepower at Sherry. The gun sections had to go out to this well south of us about a hundred yards to get their shower water for the day. I was having lunch with Colonel Beal in the mess hall, and one of the gun sections was out there pulling water, and all of a sudden there was an explosion. The kids had gone out to get water, and backing up the truck drove over a mine. The truck was destroyed but thankfully nobody was hurt

About a month later early in the morning when it was just beginning to turn light, according to the old military term begin morning nautical twilight: BMNT.

Nautical twilight is when the rising sun is still below the horizon, officially six to twelve degrees below. The term dates to the time sailors used the stars to navigate the seas; during nautical twilight most stars are visible to the naked eye. The United States military uses nautical twilight, called ‘begin morning nautical twilight’ (BMNT) and ‘end of evening nautical twilight’ (EENT), to plan tactical operations.

The definition of BMNT and EENT I heard in Ranger school was when you could see an enemy soldier in the dark and shoot him, and that distance was about the practical range of an M14 rifle, which in those days was three hundred feet. During that time in the morning twilight someone saw a Vietnamese running from that well. The guy had about two hundred yards to get to the creek bed that ran southwest of our perimeter. Everybody opened up on this guy: the Quad-50s cut loose, the Dusters opened up with their two 40 mm canons, the guys in the towers shot at him with M-60 machine guns, guys went up on the berm and emptied M-16 clips. Of course nobody hit him.

Two Tense Moments

I suspect if I were asked about tense moments during my tour at LZ Sherry when the adrenaline really flowed, it would be these two instances.

Tense Moment #1

From time to time we would get intelligence about an attack that was planned against LZ Sherry. This intelligence always had a rating, which consisted of a letter and a number. To the best of my memory the letter stood for the quality of the source and the number stood for its feasibility.

One afternoon we got a message that an A-1 report that a VC force of over three hundred was poised to attack the fire base. As would be the case, every soldier on the base sometime that day went to the berm and test fired his weapon. Every gun section rechecked direct fire lanes and reviewed their Firecracker loads. We redoubled our reviews of everything we had in our defensive plans. For example, we had C Battery at LZ Sandy north of us re-register all our TRPs around the firebase.

TRP stands for Target Registration Point: targets that are pre-determined using live fire to establish settings for the guns. Once confirmed TRPs could be fired immediately upon command without adjustment or use of a forward observer. Their value was in both speed and accuracy, however they had to be re-fired periodically to maintain their currency. The FDC at Sherry maintained close to a hundred of these TRPs for defending its sister batteries at Betty and Sandy, and for friendly units in the area. Sandy likewise maintained a set of TRPs around Sherry.

This was to make sure we were ready, and perhaps show any forward VC troops that we would be a formidable fight.

As late evening began to come on, the Air Force flew bombing sorties over free fire zones around the base to flush out any enemy formations that might have been out there. This was my first experience of being close to strafing runs by jet aircraft. As darkness came over us I imagined the pilots back at their air field in an air conditioned club having a beer.

By ten o’clock the tension across the firebase was very high and nerves frazzled. Sometime about one o’clock an AC-130 gunship arrived in the area.

The AC-130 carried as many as three Gatling mini-guns, each with six rotating barrels capable of a hundred rounds per second. It had two nicknames: “Spooky” and “Puff The Magic Dragon.” Often it went by just “Puff,” a gentle name not at all fitting its true nature.

We were instructed to start fires at prominent points on our exterior berm, which I suspect looked like a trapezoid from the air. We could hear the aircraft overhead but could not see it. We were aware that a six second burst from this airplane would put a bullet in every square yard of ground in an area the size of a football field. With fires lit, the plane went to work. The unmistakable sound of a mini-gun with its trail of tracer rounds left one in awe and rattled the nerves even more because you could see this “flying dragon peeing down on the earth.” That’s a description from a book I later read about the AC 130 gunship.

Puff The Magic Dragon … peeing

Puff The Magic Dragon … peeing

It was a long, tense night. Sleepless for almost everyone. In the end it was quiet all night, no trace at all of an enemy force, and just another page in the history of LZ Sherry.

Tense Moment #2

We received a number of ‘suspended lot’ notices concerning small arms ammunition as well as 105 mm howitzer rounds. This meant that the lot could not be used. In addition we had dirty M-79 grenades, unusable belts of M-60 machine gun ammo, and heavens knows what else that we determined on our own had to be destroyed. We decided to gather it all up, haul it to a spot some five hundred yards north of the base, and blow the whole mess up. The XO was so excited, he salivated at the thought of going out there and blowing all this up.

We notified all the right folks of our plan, and put the information on a special artillery warning network that all pilots were supposed to monitor. Come the day we trucked all the ammo to the site and set the blast time for ten o’clock. All hands were up on the berm to see the giant explosion. The XO and his crew proceed to the site, set the explosives and timer, and returned to the base. There was now just about ten minutes to the blast.

Off in the distance we saw a Chinook helicopter coming towards us from the north. Damn! The charge has been set and could not be stopped. We called Phan Thiet frantic, and they called every network these guys might be on. But to no avail. Obviously they were not monitoring the artillery warning network and on they came. The Chinook passed directly over blast site and was probably about two minutes past when the blast erupted. To this day I wonder if those guys ever knew how close they were to a serious issue.

May 18, 2016

Chuck Heindrichs – Battery Commander – Part Three

Reefer Madness

As the convoy returned late that afternoon from Phan Thiet, the wiry old First Sergeant pulled me aside and made this recommendation: Halt the convoy just outside the east gate and have an inspection of the returning vehicles and look for marijuana. So, that’s what I did. The troops got off the trucks, flung their flack vests back on the trucks, and they waited. I was absolutely amazed at how much marijuana we collected – I mean grocery bags of the stuff. Lots of it was in the flack vests, but because the vests were piled in the trucks you couldn’t associate any of it with a particular soldier.

Now here’s where a young and naïve Captain comes into play. We collected all the stuff and placed it into a really impressive pile, maybe three feet high. I had the battery formed up and indicated that I would not tolerate drugs on the base. With the entire battery watching I poured diesel fuel on the pile and burned it all. Little did I realize how hated this made me, by not only confiscating the drugs, but then rubbing it in publically in front of everyone.

Then one day I discovered another avenue for drugs coming into the battery, at least to the Quad-50 crews. When a soldier left the firebase I often sent one of our better sergeants to escort him all the way to Cam Ranh Bay. The rationale was that some of these kids would tell you how the drugs were coming onto the firebase. The sergeant would stay with the kid until he had his boarding pass and was walking through the gate toward the airplane. All this to reassure the kid he was safe from retribution, and to keep him from telling his secrets to any incoming new guys. From one of these trips we learned that the marijuana was arriving in specially marked 50 caliber ammo boxes.

I used to complement the Quad-50 crews all the time that when their ammunition came in they were johnnie-on-the-spot getting it from the landing pad. Within ten minutes of the Chinook dropping their ammo they were there; you never had to prod those guys to get their ammo off the landing pad. The next time a load of 50 caliber ammo came in I went with the First Sergeant out to the landing pad and here comes the crew to get their ammo. I said, “Guys wait a minute. We got a telex that there is a suspended lot of ammunition and we need to pull that lot and not let it get into the system.” That was not uncommon to get a telex suspending a particular ammunition lot. I saw a few marked ammo cans, but took all eight of them.

Well the word spread that I had figured it out, when I didn’t figure anything out – one of their own had squealed on the way home. Four days after I confiscated the ammo boxes with the marijuana I woke up in a cloud of smoke. Someone had rolled a smoke grenade under my bed. I remember the next day bringing in the commander of the 4/60th and I think he replaced all of the crews, because it would have become a dangerous situation. At that time in Vietnam fragging of officers was not uncommon.

I was also dumbfounded to learn that a popular way to get drugs on base from Phan Thiet was to remove the return spring from the M-16 and come back with the stuff in the vacated chamber. Not a good idea if you had to use your weapon.

I found these few avenues of what must have been a hundred ways marijuana came onto the firebase. It was a loosing battle, but as battery commander I did what I could.

Vietnamese Platoon

Before I even arrived at Sherry the battalion commander said to me, “When you get out there you are going to see that you also have a Vietnamese infantry platoon. Your job is to get them out of there.” They were in their own sandbag bunkers between the outer and inner wires at the north end of the battery. I knew there were problems between the Vietnamese and the Americans having to do with sex. The Vietnamese had their wives and families with them. There was a little bit of hanky-panky going on, as one would suspect. They were more of a problem than if they were not there. Without them we were well capable of defending ourselves.

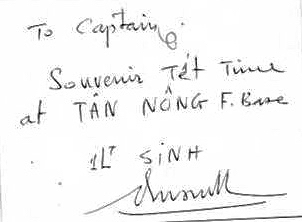

I remember I wasn’t there but a couple of weeks that the Dai Wi, the Vietnamese platoon leader, invited me to a TET celebration with his family (TET 70 was on Feb 5). I remember going over there for the celebration, being polite, and his wife bringing out all this food. I had no idea what I was eating, but I had this huge bottle of Coke to wash it all down. That may have been a mistake, because they thought I loved it and kept bringing it out. The Dai Wi was very gracious and gave me a souvenir picture with a nice message on the back.

Capt. Heindrichs at the TET banquet

Capt. Heindrichs at the TET banquet

I have a vague memory I told them they had to leave, but I don’t remember how I did it. We had been working with the sector commander, and it was out of my hands other than my mission to do everything I could to make sure that we did not have incidents of American GIs having sexual relations with the Vietnamese women coming on and off the base, and that I wasn’t to be the most helpful guy in the world.

A Rule With A Reason

Just a couple weeks after my TET celebration dinner we lost a Quad-50 crewman in a mortar attack. The Duster and Quad-50 guys used to sit on top of their tracks in the evening and at night. We had a rule that after 6:30 PM you wore a flack vest and you wore a helmet. This kid was not wearing his flack jacket or helmet and a piece of shrapnel went into his head just behind his ear, and it killed him.

E-4 Charles Cordle was killed on February 17, 1970, one month after Captain Heindrichs arrived at Sherry.

Two nights later I am walking by this same Quad-50 and I look up and there’s a new guy and he’s not wearing his helmet. I’m thinking, this is not just a harp-on, you’re sitting right where a guy was killed two nights ago. I pull this kid down and try to get him to understand that this is not a rule put in for no reason.

Problem Solved, Or Just Delayed?

On a convoy going into Phan Thiet the supply sergeant said to me, “Hey, you see those grey barrels over there with that orange ring around them? That would solve all of our grass problems.” We were always getting chewed out by our superiors for having too much grass growing in the wire during the rainy season. We took that stuff in the grey barrels and put it into a large tank with a spray spigot, then drove it around the perimeter spraying the vegetation. In a little while we had a desert around the firebase.

The Brown Band Around Sherry

The Brown Band Around Sherry

We used to have generals come from miles around and bring their commands to the base for lunch. Six out of my seven months at Sherry we had the award for the best mess in that part of Vietnam. The generals would walk out on the berm and say to their staff, “This is how I want our bases to look.” Of course it was Agent Orange that did it. None of us knew what it was at the time, just that it was good for killing weeds. Guys on the back of the truck would be standing in that stuff, and I’ve always wondered if anyone ever suffered because of that.

The military sprayed twenty million gallons of Agent Orange during the Vietnam war, covering twelve percent of South Vietnam, and in concentrations averaging thirteen times the recommended application rate for use in the U.S. A number of B Battery soldiers would suffer a variety of illnesses in later life from exposure to Agent Orange.

May 10, 2016

Chuck Heindrichs – Battery Commander – Part Two

Like A Photograph

Coming out of my first Vietnam tour in May of 1967 I went to Europe for two years with my new bride. I was first in an Honest John rocket unit, then commanding officer of the 210th Artillery Group headquarters battery (generally a thankless job), and finally special staff to the US Army Europe Headquarters for six or seven months.

The most poignant story of my entire military career, including my two tours in Vietnam, happened while I was in Germany. The experience has left an image I cannot get out of my mind.

There was a massive training area in Germany called Grafenwoehr. Units from all over Europe went there to train. I was a mess hall officer with two mess units reporting to me. As such I had to attend a mandatory one-week mess officers course in Grafenwoehr.

The week before the course started there was a fire in one of the mess halls there and a young man had died. In the middle of the course they took us on a tour of that mess hall, and how they think the fire started. It had not yet been cleaned up because the investigation was still underway. I remember, like a photograph in my mind, the exit door of that kitchen. I saw handprints from this young soldier caught in the smoke feeling his way around the wall trying to find that door. The handprints ended just four feet from the door. He died of smoke inhalation. That image haunts me even today, that but for four feet he would be somewhere else today.

The Road To Sherry

After two years in Germany it was right back to Vietnam in September of 1969 for my second tour. I remember flying into Nha Trang to the airbase there. Once on the ground we were supposed to call to First Field Force Headquarters and they would send somebody to get you. I’m on the tarmac looking around and I see a truck with IFF on the bumper and with some young kid driving it. I say to him, “Are you going to First Field Force Headquarters?”

He says, “Yeah I am.”

I say, “Well, take me over there.” There were also two Armor officers trying to get to IFF HQ for reassignment, but I hop into the truck by myself.

I get to First Field Force Artillery and this guy says, “Oh yeah, here you are. We’ve got you sorted to be an advisor to a Vietnamese battalion.”

I remember looking at this major and saying, “No, that’s not going to happen.” I gave him all kinds of reasons why that was not a good idea. Then I said, “You’ve got two Armor officers sitting back at the airbase trying to figure out how to get here for reassignment. I came over here to command an artillery battery and that is what I am going to do.”

He looked at me and said, “You say there’s two captains there from Armor? They’re not supposed to be here for a week, but if they are, Okay.” And he assigned me to First Field Force Artillery. I thought, Jeez that was close.

Over at First Field Force Artillery they tell me, “We’ll try to find you a battery, but right now there are no command slots available. But our S1 (Personnel) officer, a lieutenant colonel, was injured in a helicopter crash on his way to this assignment and has been sent back to the US. We don’t have an S1, and we don’t have a colonel available, so you’re it.”

I used to be so humble because on Saturdays I would go as a representative of IFF Artillery to the weekly IFF Headquarters briefings where there were a couple brigadier generals and high ranking civilians. I walked in as this beautiful little captain with my notepad, and they’d look at me like I was the secretary. I did that for about four months. Finally they called me in and said a command slot had opened up at B Btry 5/27 and I would be leaving for Phan Thiet within the next two weeks.

Phan Thiet was the Nuc Mom capital of Vietnam. I am very fond of Asian food, especially Vietnamese, and always order the fish sauce Nuc Mom, which is the mark of a good Vietnamese restaurant. This sauce is typically made by building a flat frame some three feet square and covering it with lattice and palm tree branches. These are stacked until you get to some eight feet high. This structure is filled with raw fish on the various layers and placed in the hot sun. The fish oils drip down through each layer to a catchment container at the bottom. This oily residue is then refined into a delightful sauce, really great with rice paper rolls filled with vegetables and meat. To make this long story short, when I flew into Phan Thiet I could smell that stuff for miles on my way in.

The Road Out of Sherry

I have a lot of memories of that base. As a young second lieutenant on my first Vietnam tour it always amazed me when I talked to the old sergeants, that some of these guys could remember their World War Two experiences, they could remember Captain Brown, his wife’s name, that Captain Brown had three kids, the kids names. They couldn’t remember the names of their grandkids, but they could remember old Captain Brown from World War Two. I have that same feeling now, that I can almost close my eyes on a daily basis and picture every gun at Sherry; I can picture that marvelous mess sergeant that we had, and our Chief of Smoke who was named Duke.

I was young and naïve when I first came to the firebase. I was there about two days when the First Sergeant (Richard Durant) said to me, “We don’t go very often but we have a scheduled convoy into Phan Thiet, and let me tell you how this works. We line up the trucks and then we get these mine detectors and we do a mine sweep along the access road.” That was a dirt road leading east out of the battery to the main highway about two miles away.

Road east out of Sherry

Road east out of Sherry

I, being rather naïve, said, “I would never expect any soldier to do anything I couldn’t do. So I’ll join the mine sweeping operation.” I remember leaving the base at that southeast corner.

At zero-dark-thirty of the day (between midnight and sunrise) two teams with mine detectors started down the east road. The teams were three or four people. There needed to be a rotation about every 10 minutes or so because the high pitched whine of the detector would dull your ear such that you might not hear a serious change in pitch. The other team members walking along had a bayonet and a strong sharp wooden stick. When the detector sounded you froze, placed the detector over the spot, and one of the others would begin probing for the mine. Usually you used the stick because the bayonet might just go in between the contacts and complete the circuit. Ninety-nine percent of the time the item was a piece of shrapnel or metal.

In any case, I worked from the east gate to the creek, just to somehow prove that I would not expect a soldier to do something I would not do. I remember we had about a hundred yards to go before we hit the creek, and I’ll be damned if we didn’t find one. Most of all I remember being scared shitless.

May 4, 2016

Chuck Heindrichs – Battery Commander – Part One

Captain Chuck Heindrichs

Captain Chuck Heindrichs

West Point ’65

Battery Commander, January – August 1970

Captain Chuck Heindrichs came to LZ Sherry in January 1970 on his second tour in Vietnam. His first Vietnam tour was in 1966: leading a platoon of 155 mm self-propelled artillery attached to an Australian battalion, and then participating in Operation Junction City, one of the largest operations of the Vietnam war. Like many officers returning to Vietnam on a second tour he insisted on a combat command over a desk job. His was not a quiet time at Sherry, best described in the First Field Force newspaper three months into his command.

To appreciate Chuck’s command at Sherry we begin with his early career and first tour in Vietnam … in his own words.

The Road to Vietnam

The scenario for my class out of West Point was you went to airborne school and Ranger school, and then you went to the officers basic course for your branch training, which in my case would have been artillery at Ft. Sill. Our class, and we may have been the first, skipped the basic course and learned artillery on the fly. My first assignment out of Ranger school was to Ft. Carson, Colorado assigned to the 1st/19th Artillery, whose mission was to conduct basic training for six hundred young kids in how to shoot a rifle, wear a uniform, etc. I did that for a couple months, and did not learn much artillery in the process.

All of a sudden I learn about a 155 mm self-propelled howitzer unit on post that has alert orders for Vietnam (2nd/35th). Thinking it’s only a matter of time before I’m going to Vietnam anyway, I’ll just volunteer for that unit and maybe get my pick of assignments. But you’re a 2nd lieutenant, you’re probably going to be a forward observer no matter what.

This was going to be the first self-propelled artillery unit going into Vietnam, and we spent maybe three months putting the unit together. At that point the Army had gotten over its shyness about using armor and tracked vehicles in general. They had sent an armored unit or two over there and found out that tanks, armored personnel carriers and other tracked vehicles could get around just fine.

The Army at that time did not have jungle equipment, jungle boots, jungle fatigues or even OD olive drab underwear. There were about five hundred guys going over. They and their wives hit the local Laundromats to dye their white Army-issue underwear green. They overwhelmed the Laundromats dying t-shirts, drawers, socks and handkerchiefs. All this green dye left a residue for the next unsuspecting civilian coming in to do their regular laundry, surprised to see it coming out a light green.

We left Ft. Carson in June 1966. All the equipment went on trains headed for port, while the unit itself went up to Spokane and boarded a troop ship. I did not leave with the unit because I had gotten strep throat and had a three day delay. Rather than trying to catch me up with the troop ship they just threw me on a plane with the advance party, which left a week and a half later.

We flew on a C-130 for what felt like a week, island hopping all the way over. It was the most uncomfortable thing, because it didn’t have regular seats. It just had the flop down canvas seats on the side. Twice leaving Guam the plane was in the air for an hour, sprung an oil leak, and had to fly back and sit on the runway for repairs. Long story short, we get there and we are assigned to Second Field Force, which at that time was at Ben Hoa. They tell our battalion commander that they are going to detach one of his batteries and assign it to the Australians. I was assigned to A Battery, and as luck would have it, they sat me down and said it’s your battery that’s going to work through with the Australians. Learn all you can about their operation, figure out how to talk to them and so forth.

Chuck learned almost no artillery pushing troops through basic training at Ft. Carson . It was with the Australians that he would become a true artillery officer.

Little Toys To Big Toys

The Australians had come over with this little L5 pack howitzer, shooting the snot out of this thing and wrecking them because they were not very big. They looked like little toys. All of a sudden they’ve got these big 155 mm self-propelled coming in. They’d never used them, never even seen them, and it took a while for them to get used to the fact that these guns were used in a direct support mode. They were still leery of shooting that big a round that close to troops. It took time for them to get used to us, and we to them, and how to communicate over the radios. They also had a New Zealand contingent there, a battalion of infantry and an artillery battery.

Gordon Steinbrook, a forward observer attached to the First Australian, wrote a book based largely on correspondence with his wife. In it he says,

“Our battery fire direction officer was Lt. Chuck Heindrichs, a West Point Graduate. Chuck was loud, obnoxious, and at times overbearing. Though he had no formal artillery gunnery schooling, Chuck taught himself, and with the help of the FDC section chief he molded the Fire Direction Center into a capable organization. At handling troops, Chuck was a wizard. He could be loud and harsh one moment and the next minute put his arm around a soldier and say, ‘OK, now let’s sort this problem out.’ Chuck had a gift for keeping morale high. Chuck played the guitar, a talent all of us were to appreciate in the coming months.”

Allies and Mates: An American Soldier with the Australians and New Zealanders in Vietnam, 1966 – 1967, by Gordon L. Steinbrook

All pictures below were taken by Chuck and appear in Allies and Mates

Lt. Heindrichs at far left, next to “Gordy”

Lt. Heindrichs at far left, next to “Gordy”

Aussie L5 Howitzer

Aussie L5 Howitzer

A Battery 155 mm howitzer

A Battery 155 mm howitzer

There was a rule in those days that if you had a hundred and twenty days or more of service left you went to Vietnam, even if it meant in four months you would be going home. Our battery XO (Executive Officer) had 138 days left when he left Ft. Carson with the main body. By the time the unit shipped by rail to port, spent thirty-two days on the ocean, and finally got to the First Australian Taskforce, he only had about sixty days of service left.

Since I went with the advance party I got to the First Australian well before him, and as a result I had gotten integrated into their tactical operations center. I learned their radio call sign system, I introduced them to the 155 mm self-propelled howitzer, I worked with their infantry guys to let them know what was coming. So I became the designated replacement for him when he left Vietnam. I went out with the infantry showing these guys what the 155 guns could do, and helped them experience calling for fire, let them get used to the size and magnitude of rounds going off relatively close to them. To be honest, it was as much a learning experience for me as for them, a learn-on-the-fly for a young officer in Vietnam.

The Wrong Red Reflector

We pulled out of the Australian unit to participate in Operation Junction City, an awfully big operation involving something like forty battalions up into Tay Ninh province and War Zone Charlie (near the Cambodian border).

Operation Junction City was an 82-day airborne operation conducted by United States and South Vietnam forces beginning on 22 February 1967. It was the largest U.S. airborne operation since WWII and the only major airborne operation of the Vietnam War. It was one of the largest U.S. operations of the war, involving the equivalent of nearly three U.S. divisions totaling around twenty thousand troops. The aim of the engagement was to locate the elusive ‘headquarters’ of the Communist uprising in South Vietnam. According to U.S. analysts such a headquarters was almost a “mini-Pentagon,” complete with typists, file cabinets and staff workers. The actual headquarters, revealed after the war by VC archives, was a small and mobile group of people sheltering in ad hoc facilities.

It always terrified me as the battery XO that somebody somehow would make a mistake. I used to walk around all night just checking and talking to the crews. I remember one night seeing the guns silhouetted against the sky and noticing one of them absolutely did not look right. I walked up to the gun sergeant and said, “Let’s look at re-laying this gun because it just does not look right to me.” And sure enough when we checked the gun was aimed in the wrong direction. And here’s how that happened. When a gun is laid using an aiming circle there are two stakes placed at 50 feet and 100 feet away – one with a green reflector and one with a red reflector. Looking through the site of the gun, when the green and red reflectors line up, along what is called the Near Far Line, you know the gun is aligned correctly and parallel to all the other guns. You then put out your permanent aiming stakes used in adjusting the direction of the gun for fire missions.

When the sergeant looked through the sight along the Near Far Line he said, “You’re right.” Then I looked through the site and said, “Wait a minute.” We walked out in front of the gun and discovered he had lined up the gun according to correct procedure, but instead of using the red reflector stake on the Near Far Line, he had used a reflector on the back of a truck.

April 27, 2016

Mike Jordan – Duster Platoon Leader – Part Five

Sherry

I had two Duster positions at Sherry (on the East and West perimeters) that we occupied on and off. I was also responsible for looking after the two Quad-50s at Sherry, even though they were not under my direct command. The Quad-50s belonged to Echo battery of the 41st and were attached to my Duster battalion, the 4/60th. The Quads did not have a lieutenant in that area, and because I was the senior officer from the 4/60th battalion, as such I was a kind of liaison to them. It was nothing formal, but I looked after them, mostly to make sure they were supplied with parts.

Quad-50 parts would come in by chopper to us at the command post at Betty and I would take them out to Sherry, usually parts for the 50 cal machine guns, which were very hard for them to get, especially the parts for the turrets. After I left they replaced me with a captain and gave him full command authority over the eight Dusters, the Quads and the searchlights up on Titty Mountain. He was kind of a glorified super-platoon leader. It gave all of them more horsepower when it came to getting support.

There was one unique event at Sherry that I remember. There was one troop out there from one of the Quad crews. The night he was scheduled to DEROS, or leave Sherry, they were having a going away party for him in the Quad-50 hooch. They started taking mortar fire at roughly two o’clock in the morning. Everybody at the party who was from the Quads left and ran out to be on the gun to return fire. Even though he was scheduled to leave the next morning, he went with his crew and was running across an open area, and a 82 mm mortar round landed right at his feet. After things settled down and the firing stopped they called me for a dust-off (evacuation by Medevac helicopter). I met the dust-off at the chopper pad when they rushed him in, and then they had to turn around and evac him to Cam Ranh. I do not remember either his name or the exact date, I want to say April or May of 1969. They ended up having to amputate both his legs.

Duster Sunrise

LZ Betty was on a bluff overlooking the South China Sea. The chaplain decided to have the Easter Sunrise ceremony on the bluff and asked each of us to bring down a significant piece of equipment from our organizations. So I took a Duster and caught a picture with the sun rising behind it.

Easter April 6, 1969

Easter April 6, 1969

Up North

After I left the 1st platoon and went back up north to the 2nd (early summer June or July of 1969) platoon at Tuy Hoa. I had a section of two tracks at Ninh Hoa just north of Nha Trang. We commonly called it Tuy Hoa, but in reality Tuy Hoa was an Air Force base. We were about half a mile outside the perimeter of the Air Force base at an Army airfield called Phu Hiep.

We were sitting again with an 8 inch / 175 mm battery belonging to the 6/36th and that was their battalion headquarter. My battery headquarters was co-located with them. We ate in their mess hall, we partied with them on Friday nights, we escorted their convoys wherever they need to go. In reality we were almost part of that 8 inch / 175 mm battalion.

We were on one hilltop, and there was an NVA company or battalion across the valley on the next hilltop. They would lob mortar rounds at us and we’d fire back long streams of those 40 mm tracers at them. You’d sit there and watch them go Boom, Boom, Boom – a solid stream.

Spent ammo casings after one minute of firing at the NVA

Spent ammo casings after one minute of firing at the NVA

Courtesy Joe Belardo, from Dusterman: Vietnam

No Thank You

I left Vietnam in January of 1970, a year after I arrived. But not before I had the occasion to remember my old platoon leader, 1st Lieutenant Frank Hewitt. He had suffered the head injury that put him in the hospital while on a six month extension. My battalion commander tried to do that to me too, “You come back, you’ll make captain, I’ll give you command of Alpha battery.”

I said, “That all sounds good sir, but if I come back I’ll come as a divorced man.” I went home and went on to Ft. Bliss.

Mike went on to a twenty-year career in the Army, including teaching in the ROTC program at Seattle University. He passed up an assignment to the Pentagon, and a sure promotion to lieutenant colonel, choosing instead to retire. He then worked for a succession of large defense contractors and became a civil service employee. Along the way he returned to college for his bachelors degree, and then proceeded to earn three masters degrees. He said, “My basic philosophy was if someone else will pay for it, I’ll go to school,” a good piece of advice for anyone.

Mike is still married to Mary Beth Jordan after 49 years and still lives in Albuquerque, NM.