Ed Gaydos's Blog, page 3

December 7, 2016

Jim Kustes – Gun Crew – Part Two

Kustes center loading a round on Gun 5

Kustes center loading a round on Gun 5

Living Large

I spent thirty years not giving Vietnam a thought. So there are big gaps in my memory. Early on a very close friend, Steve Sherlock, died on a mine sweep. Eight months later at the end of my tour I’m wounded bad when the jeep I am sitting on hits a mine and Paul Dunne is killed. I remember both of those, but not a whole lot in between

I do remember it was not all doom and gloom at Sherry. I had a good time there, one of the best times I ever had. I don’t remember a lot of details, but I remember the big urn of coffee the cooks put out at night outside FDC. That’s where I learned how to drink black coffee without cream. The little cartons of milk were a lot of times soured and you’d hunt for one that was good. In the mess hall I liked to watch the officers who flew in for a day go into the officer’s section with a carton of milk. They’d take a big swig of that milk and spew it out. I’d get a kick out of watching them.

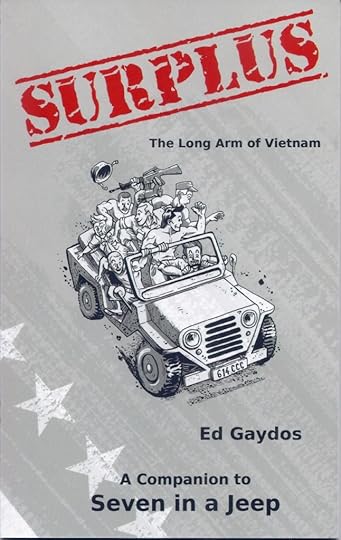

I was friends with the guy who worked in the mess hall, Mike Bessler from Doylestown PA, and I would go down to the chopper pad when they brought the ice in and help unload. I always dropped one and got to keep a chunk. In my hooch I had a cooler and I always had ice cold beer. My hooch mate, Leroy Leggett, had a reel-to-reel tape recorder. We ran a secret wire from the battery generator into my hooch, so we could play music. And we had lights strung up in there. I could get ten people into my hooch with the music and lights and cold beer. The guy in the mess hall would give me ham, and we’d have ham sandwiches too. One day the First Sergeant, it had to be Durant, walked in because he heard the music and the partying. He just stood at the door and said, “Jeez, you guys got it better than I got it.” He just shook his head and turned away and walked out.

Party time in Jim’s hooch – Leggett with pipe, Jim with beer

Party time in Jim’s hooch – Leggett with pipe, Jim with beer

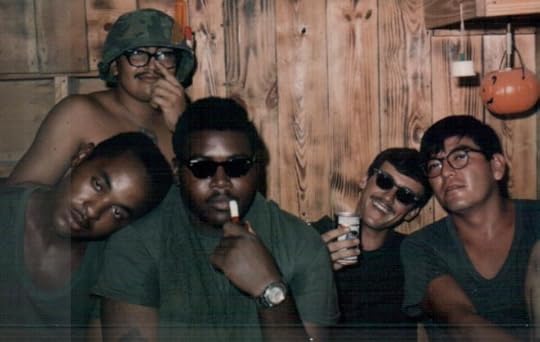

I made sure I had as many amenities as possible. Our showers were made out of ammo boxes with a 55 gallon drum on top and a ladder going up to fill it. The officer’s shower had a portable water heater in the barrel, and I thought if they had hot water why not us? So I worked on my shower to make sure we had hot water. I can’t remember exactly how I did it. I may have gotten a water heater and heated the water on the ground and then carried it up. Or I may have put the heater in the barrel on top of the shower. I don’t remember. I do know we had hot shower water on my gun.

The M67 Immersion Water Heater ran on diesel, and heated water to clean mess kits, trays, utensils and canteens. The officers shower had one installed in the water barrel perched on top of its rickety frame. The enterprising Kustes somehow secured an M67, no doubt through his special relationship with Mike Bessler.

Cindy, mess hall worker, with M67 water heaters

Cindy, mess hall worker, with M67 water heaters

Two Showers

Two Showers

Original picture by Dave Fitchpatrick

Ants, Scorpions and Snakes

We were being mortared so much in July and August of 1969, every day, that it didn’t bother me anymore. We couldn’t get anyone to patrol the mortar sites for us, so Lt. Parker got all the guys to go out and look for ourselves. There were probably twenty or thirty of us. Parker told us when we hit this mound out in the rice paddies for everyone to open up on the tree line with suppressive fire in case anyone was out there. When we get there we all hit the ground and open up. I had this piece of crap M16 that jammed on me. I am laying on the ground trying to clear my rifle. I am laying on the ground trying to clear my rifle. Red ants start biting the hell out of me, and I realize I am laying on top of their nest. I jump up brushing them off, and I look around and everyone is laying on the ground shooting and here I am standing up jumping around in the middle of it all. I was lucky we were not getting any return fire.

After that day, I thought if I ever have to go anywhere I am taking an M14. One of the medics had an M14 and I borrowed it from him whenever I had to go anywhere. I never used my M16 again. Guys would carry the cleaning rod on the butt of the M16 to poke out the spent shell when it jammed and wouldn’t eject. You had to keep the M16 really clean, but the oil you had to use on it, because things were so sandy, made it worse.

……………………..

I remember when I first got in country, people had these scorpions and they’d take a pencil to make them strike it. One day I was taking a sandbag out of the gun parapet and reached in and got stung in the finger by a scorpion. It kind of scared me because being naïve you hear all these stories about you better get aid right away. I went to the medic and he said, “Yeah, you’ll be alright.”

……………………

We also had a cobra in our parapet. It would rear up with its hood. I had a bad fear of snakes at the time. But one of the guys shot it. Later I was working out on the perimeter and this black thing sprung up on me. I almost crapped my pants I thought it was a cobra. It turned out to be a piece of black metal banding that popped up when I stepped on it.

November 30, 2016

Jim Kustes – Gun Crew – Part One

Jim at Sherry on Gun 5

Jim at Sherry on Gun 5

Into the Army

I got my acceptance letter to college and my draft notice on the same day. I was nineteen years old. I thought: There’s no way I can afford college anyway, so I’m just going to go in and let the Army pay for college when I get out.

I went to Buffalo for induction. You’re in a big classroom and somebody comes into the room and says, “You … you … you … Follow me.” They take five or six people, all going to the Marines. They left the room and we never saw them again.

I went to Ft. Dix in New Jersey for basic training in April of 1968 – nothing eventful there.

At the end of basic I got sent to artillery at Ft. Sill for AIT. It was pouring rain when I got there. In the day room the sergeant said, “Who’s got a poncho?” I happen to have mine and I gave it to him and he said to me, “You are now the platoon sergeant,” which meant I had to sit at this desk all night and answer the phone if it rang. I broke the cardinal rule of all draftees to stay in the background and not become known. Now every time the sergeant wanted something he’d call my name, because it was the only name he knew. I was nineteen years old; I didn’t know nothin’.

It Ain’t Fair

I ended up second in my class in artillery. The bad part was, and this is crazy, at the end when you get your orders for your next station they bring out a list of everyone who had made the next rank of E3 (private first class). Here I was the platoon sergeant and second in my class, and I didn’t make it. Out of seventy-five or so guys only half a dozen didn’t make the next rank. I couldn’t believe it! I would think I’d be at the top of the list.

I went in to see the lieutenant to ask him what happened. He said, “I’ll put a note in your file so you’ll make it when you reach your next assignment.” I found out that one of the clerks in the office was selling spots on the promotions list for twenty-five bucks. He’d take one name off and put another one on, and that’s how my name got taken off.

Germany

The sergeant who I gave my poncho to when I first arrived for AIT asked me if I wanted to go to the NCO school there at Ft. Sill (an advanced program comparable to the artillery training officers received, and which gave an automatic promotion to E4 upon entry, and to E5 upon graduation). Here I was thinking about going to the this school, the shake and bake program, but thought: No way, they are just screwing me all along and they’ll screw me there. And the thing is, you got sent to Vietnam right out of that program.

Instead I get sent to Germany. I spent five months in Germany, and I hated every minute of it. I was sent to Supply at headquarters battery because of my typing skills. I loved Germany itself, but my job was extremely boring. It was a nine-to-five job and all I did was sit. Just sit and not do anything. At five o’clock I’d go down to the bar and drink. I was making something like a hundred and thirty-eight dollars a month and I was broke all the time. The German mark then equaled twenty-five cents, and I think a beer was about one mark (the price of a beer on post at the enlisted club). And it was delicious beer too, which is where all my money went.

No money, doing a boring job; I actually volunteered to go to Vietnam. I had two friends I grew up with who were both in Vietnam. I’d get letters from them. I wanted a different experience.

A Different Experience On The Road To Sherry

I go to Ft. Lewis for a few weeks of Vietnam training. When I got to Vietnam I remember being at Phan Rang to get my assignment and the supply sergeant read my file and he was standing talking to the lieutenant and said he wanted me to stay there, because I had experience with the new supply forms that just came out. I said, “Yeah, I worked on them every day.” The supply sergeant was supposed to implement the new forms and didn’t know anything about them. When they looked at my record they also saw that I was second in my artillery class and the lieutenant said, No we need him in the field. And that’s when I went out to Sherry.

I remember how scared I was going out there. Most guys went on a helicopter. I went out on one of the convoys riding on top of an ammo truck with a couple of ARVN soldiers. In my Vietnam training at Ft. Lewis they told us about local customs, about men holding hands. Well one of those ARVN soldiers put his arm around me and I thought: What the hell is going on here? All the way out to the base he has his arm around me and I didn’t budge the whole time. If I pushed him away the last thing I needed was an argument, so I just sucked it up.

November 16, 2016

Ed Gaydos – Fire Direction Control – Part Six

Freedom

The plane for home left from Cam Ranh airbase, just as filthy as I remembered it from a year earlier when I’d spent a couple days there in transit to Sherry. Back then I couldn’t get out fast enough, and the same held now.

As the plane rolled down the runway the cabin filled with happy chatter. When the plane left the ground a cheer went up and seemed to give the plane an extra little lift. Vietnam was only a few feet below us, but it felt like a thousand miles. I’d never felt that free. Maybe that is why every plane out of Vietnam was called The Freedom Bird. A very good name.

In civilian life the plane was a Pan American charter, with real civilian stewardesses. To my starved eyes they were goddesses. When the plane got to altitude, they deployed down the aisles. One stopped at my seat and said, “Can I get you anything?” Having not heard an American female voice for so long, it stunned me. The last time was when a Red Cross girl came into FDC, a significant enough event for me to write home about it.

September 16, 1970

I talked to a girl last week. An American! It’s only been five months. A couple of Red Cross chics came into our fire direction bunker, and I was in there all alone. I said something real intelligent, like, “Hi.”

Now six months later I was paralyzed again by the magic of a female voice. When I didn’t answer she said, “Well honey, when you decide you just push my button and I’ll come.” She smiled in a wicked way and went to the next row of seats. I followed her voice down the aisle. “Something to eat? Would you like a blanket?” I could have listened to it forever.

Halfway home over the dark Pacific I turned in my seat and looked to the back of the plane. I saw by the cabin’s half-light a boy asleep next to a stewardess, his head resting on her shoulder, like a Madonna and child, and I wished with all my heart to be on that shoulder.

Higher Education

A few weeks back from Vietnam, my skin fungus almost cured, I rushed into graduate school at the University of Missouri just in time for summer school. Like a long vomit, I just wanted the Army to be over so I could move on with my life. Gone were plans to bum around the country or take a boat to Bimini. I needed to get on with my life in a serious way. The main campus was in Columbia, a small town in the middle of the state. Downtown was right outside the campus gates and had one decent restaurant. The farms began a mile from downtown and did not stop until reaching Kansas City to the west and St. Louis to the east, 125 miles in either direction.

I had been dreaming for some time of living away from people and regaining my sense of personal privacy, and now I had the chance. For two years in the Army I ate, slept, showered, worked, played and sat on the latrine in public. Before that there were seven similar years in the seminary. In Vietnam I longed for the time when I could be alone.

August 15, 1970

I will need a few months by myself when I get home to work the regimented life out of my system. I think I am simply tired of people telling me what to do 24 hours a day. The desire for isolation is fairly common in the Army. Almost everyone I ask about their plans after the Army say they are going to live by themselves in the woods.

I rented a little place five miles east of town on a small lake and surrounded by pasture. The cows were perfect neighbors, they never gave orders and did not carry guns. I had no telephone, figuring that if someone wanted to see me they could catch me outside class or drive out and knock on my door. It was heaven.

Life on campus was far from heavenly. I had hardly gotten the sand from between my teeth when I found myself in the charged environment of the college campus of 1971. Students were in a white lather over the war, with more passion than understanding. Loud and mindless, they reminded me of the cows bellowing outside my bedroom window.

“An unjust and unwinnable war.”

“Post colonial imperialism,” whatever that meant.

“Baby killers.”

And my personal favorite, “Make love not war.”

When a few of my fellow graduate students found out I was just back from Vietnam they used me as their bayonet dummy. Young people who had never lived outside the covers of a book told me how I needed to think about Vietnam. They were passionate in their convictions, unencumbered by any real knowledge of Vietnam, and without life experiences to soften the hard edges of their opinions.

I always asked them one question, hoping to find someone willing to be quiet for a second and listen, “Would you like to know what it was really like over there?” No one did, because the principles involved were more important than the people. Had they taken the time to listen, they would have learned that I was not so much in favor of the war in theory, but very keen on fighting it in reality. My feelings were clear in a letter home after just two weeks at LZ Sherry.

May 16, 1970

The violent clashes on our college campuses over the expansion of the war into Cambodia is sad but understandable. I too would rather see an end to the mess. However, we have allowed the enemy virtually unrestricted use of a “neutral” country for almost six years, while refusing our own troops the opportunity to cross the border. It’s been a badly one sided game. Infiltration routes run from Cambodia … right through our backyard. And we pay for it. When the mortars and rockets are coming in, and you know where they’re getting them and you can’t do a thing about it and a medevac flies out a wounded 19 year old – well you look at it differently than the well fed, scrubbed, secure college student.

The soldier in combat was simply not a topic of conversation on campus. His experiences did not have the sweep of ideology and produced no grand proclamation. The principles were more important than the people. That was the raw nub of it. The individual soldier was insignificant, and he was the only one to notice.

Fortunately I was still in the emotional dead zone guys who had spent any time in the field brought back from Vietnam. I said to myself, It don’t mean nothin, which in Vietnam was a way not to care. About anything. The anger and disappointment I came to feel about those early days on campus came later, the emotions waiting for their time.

The Hero’s Welcome

Bob was a fellow graduate student, older and focused on his studies. I liked him because he spoke in a soft and measured manner. We talked about classes and professors, neither one of us volunteering much personal information.

Bob walked with a limp and one day I asked him about it. He said, “I’ve got a prosthesis and I’m still adjusting to it.”

I said, “I never would have guessed. What happened if you don’t mind my asking?”

“Stepped on a mine.”

“Wow. You loose it above or below the knee?”

“Above. That’s why I’m having some problems.”

We both went quiet for a little while. I said, “I was in Vietnam too and just got back a couple months ago.”

“Where were you?”

“Two Corps, outside Phan Thiet, at a 105 firebase.”

He said, “Cushy artillery job, huh? I was up by the DMZ, around Quang Tri a lot. Nasty stuff up there.”

“Yeah, anything near the borders. I had a buddy at Kontum. Same thing.”

He said, “I been back over a year, in and out of VA hospitals. Pretty depressing, all those guys with parts missing. Soon as I could get around on my own I got myself out. Now some days are good. A lot of them suck. So you couldn’t tell, right?”

“No, all I noticed was the limp.”

He said, “Listen, I’d appreciate it if you wouldn’t mention the Vietnam thing to anybody. They just don’t understand.”

That’s how this hero was welcomed home. He was shouted down and bullied into silence, a finger poked in the chest that held a Purple Heart.

My Madonna

I had met Kathleen on a blind date nine months before Vietnam while on leave in St. Louis. I did not know why she agreed to go out with me. I had no hair, no money and no prospects. What was this good Catholic girl from south St. Louis thinking?

Her parents welcomed me into the living room and invited me to relax on the sofa, saying she’d be out in a minute. Soon a petite Irish beauty walked into the room wearing a pair of low hip huggers in brown plaid. I was instantly in love. But she had forgotten something. She turned her back, wiggling those hip huggers out of the room, and oh my, now I was in lust.

Whenever I got a weekend pass I’d make the nine hour drive from Ft. Sill to St. Louis. Sunday night I’d leave for Sill with just enough time to get into uniform and report for morning duty, unshaven and looking a mess. Then in Vietnam we wrote regularly to one another.

In Columbia Kathleen came to visit my country hideaway on weekends. She was working on a master’s degree in earth science, and turned our walks in the woods into rock hunting expeditions. My job was to carry the rocks and load them into my VW bug, which groaned under their weight. She called the rocks her 100 million year old antiques. When the weather was nice we took rides on my motorcycle, a little 175 Honda. I thought it a romantic gift when I got her a helmet. She still carries a burn scar on her leg from brushing against the muffler. Or we sat behind my little cottage contemplating the lake and watching the cows. Such was my welcome. I didn’t get thanks from a grateful nation or free drinks in bars. Instead I got what I needed: a dark Irish madonna upon whose shoulder I could rest my screwed up head.

I don’t know why she went out with me in the first place, or more a mystery why she gathered me up after Vietnam. I did not return a charming fellow. In Vietnam I had counted the days to being a civilian again, had marked off every day with a red X, but now at home I felt out of place. I had come back different somehow. I had lost the emotions that seemed to come so easily to others. I could only comment when others had tears in their eyes. When they laughed from the belly, I had to work to get up a smile. Most of all I could not feel compassion for the suffering of others; nothing surprised or disgusted me. I was a mere observer, standing on the edge of life and looking in.

Kathleen said, “Give it time.” And she was right. Over the months I traded my Vietnam neuroses for all my old ones, and probably a few extra. I returned to getting angry over stuff that did not matter and worrying about things that never came to pass. One day I asked Kathleen about the plaid hip huggers that had enflamed my imagination when we first met. She said, “Oh, I threw those old things out a long time ago.” I knew I had gotten over Vietnam because, upon hearing this, I cried like a baby.

November 9, 2016

Ed Gaydos – Fire Direction Control – Part Five

On Second Thought

The First Sergeant stopped me as I walked across the battery. “I remembered you wanted to be an FO, and were pissed when the captain said no. So I talked to the new battery commander. He says it’s OK if you still want to go.” He paused and looked me full in the face. “But I would consider it a personal favor if you didn’t.”

Top had never before talked to me as an equal. I said, “Top, let me think about it.”

By then I was starting to look forward to going home and had an early start on a short-timer’s attitude about staying behind sandbags as much as possible. I still wanted to tromp around with the infantry and call in the big stuff, but sitting in the dark in my hooch there were two questions I could not answer. Why? And how crazy was I to volunteer in the first place?

The next morning I said to Top, “I’m not going, but thanks for checking, Top.”

He said, “Good decision.”

The Warrior Departs

Top left LZ Sherry shortly before me, meaning we had spent almost our entire tours together. I wrote home about his leaving:

February 5, 1971

I will be glad to see him go. I’ve been under him for ten months now and he is a raving irrational Tazmanian. I have never liked being yelled at and on occasion it took all my composure to ignore him. He knows I ignore him and does not bother me too much.

Top was retiring from the Army after this tour. Earlier he had stopped me after morning formation and said he noticed all the mail I was getting from colleges. Could he look at the forestry stuff? I had been trying to decide between forestry and psychology as my life’s work, not exactly a tight career focus. The two piles of brochures had been growing for some time. Top said he was thinking about what to do when he got out and forestry seemed interesting. I scooped up the whole pile and walked over to his hooch.

I found him sitting down. He raised his eyes with a look I had never seen from this veteran of two wars. It was a look of uncertainty. He was about to enter a world more threatening than any Viet Cong sapper or North Korean rifleman. There was something else he could not hide: envy of my youth and its easy optimism about the future.

We sat and went through the material, talking about the best schools, the ones that gave scholarship money, and the nature of the coursework. As we talked I imagined Top going into civilian society with his ham-handed approach to life, a face made old by the sun and the few remaining strands of hair clinging to his skull. Retiring from an unpopular war, he would find few people to value his experience, his skill or his judgment. He would be a holdover from a bygone age, struggling to find a place in a world that had moved on while he was busy fighting its wars.

Top returned the forestry brochures even though I said to keep them. He was not built for the classroom and I believe he knew it. He stood in front of the Huey that would take him away and waved. He held a big smile on his face and pretended to enjoy the moment, a showman to the end.

The closest I got to Top were the games of cribbage we played on night shift and the one conversation we had about his life after the military. I was too much of a twenty-five-year-old snob to let myself know him better. Top had been to hell and back in his military career and he cared passionately about his men. Those were rare qualities in a leader in Vietnam.

Andy Kach took this picture of Top as I like to remember him.

It is an irony of my military career that the person I was most happy to be rid of, I would give anything to see today.

My Own Departure

A lot of guys had fancy short-timer calendars in their hooches to mark off the days. I adopted the calendar hanging in FDC, because at midnight it was the sacred duty of the night crew to take up a special red marker and cross off the day. The formal reason for this was to get the date right on the endless forms that came out of FDC. The real reason came when the the guy with the marker announced: “One less day in Vietnam,” only using more colorful language.

Gaydos and his calendar

Gaydos and his calendar

When the red X landed on the day before your scheduled departure from Sherry, you packed your duffle bag and the next morning got on a Huey for the trip to Phan Thiet. There were no big going away parties. No ceremonies. No announcements even. One day a guy was there, the next he was gone. Some like Top got a wave from the troops, but most just got on the helicopter and left, as if on another routine errand to the rear. In a letter home my last night was not much different than any other night.

March 16, 1971

It is my last night at LZ Sherry. I would like to retire early tonight, but we are having a practice session for a coming inspection. Being the old experienced hand I will have to be there. I start at 6:30 in the morning and usually walk away from FDC around 11:00 at night.

The next morning I packed a duffle bag, exchanged home addresses with a few guys and stepped on the chopper. As we pulled into the air and turned south toward Phan Thiet, I looked on LZ Sherry for the last time. The ground was the same dry-season brown I saw when I arrived. The rice paddies around the firebase showed craters from howitzer and mortar fire, scars I knew would someday heal. I was less sure of the marks on me.

Craters (white dots) in rice paddies around Sherry

Craters (white dots) in rice paddies around Sherry

November 2, 2016

Ed Gaydos – Fire Direction Control – Part Four

Tube Ring

We were blessed with a succession of great lieutenants during my ten months at Sherry. They were smart, and to a person tried to do a good job. Most important they listened to people who knew more than they did, because they knew that’s how you made good decisions. Pretty simple. This story is about the one exception, a second lieutenant who wandered into LZ Sherry as a lamb among wolves.

His first assignment was as officer in charge of the howitzer crews. The lieutenant seemed to have learned nothing in artillery training and was slow to learn the ways of Vietnam. Yet he issued directives on such details as gun maintenance and crew rotation, and the veterans soon viewed him as a fool. Were this his only flaw, this young man would have grown into the job like most new officers, but with a few more bumps and scrapes than the average. However he suffered from another defect that would be his undoing. He was gullible.

Late one night during a quiet period, a call came into FDC over the landline. “FDC…Gun 2.” It was Swede.

For the moment Swede was a corporal. Over a twelve-year career he had been up and down the enlisted ranks, working his way up to sergeant and in a single act getting busted down to private. Just before deployment to Vietnam he slugged a staff sergeant, whom Swede insisted had it coming. Now he was on the rise again, having worked his way back up to corporal.

He was a huge guy with a shock of blonde hair. Two large front teeth came out when he smiled, the dental work of a rabbit in the head of a water buffalo. He was a simple guy who laughed with his whole body and was quick with his fists. Swede spent his evenings drinking and playing poker. He told me the reason getting busted never bothered him was that he made more money at cards than he ever earned in military pay. I liked Swede but was careful never to make him mad, and never to play poker with him.

“Yeah,” I said.

Swede said, “We have to take Gun 2 down.”

“OK. What’s going on?”

“Tube ring.”

“Say again?”

“The lieutenant’s here and we thought we ought to bring it to his attention. The tube ring doesn’t sound right.” There were a lot of things to worry about regarding the howitzer barrel, but tube ring was not one of them.

“Put the lieutenant on.” I was never sure what Swede was up to.

I said to the lieutenant, “Sir, I understand there is a problem on Gun 2.”

“The tube ring, it doesn’t sound exactly right to me.”

“Yes, sir.”

“The gun corporal called me over, well anyway he had me listen as he tested the tube and I agree the ring is off.”

“Sir, which test did he do?”

“He did the one where you hit the tube and listen.”

“I see, sir.”

“… and it was off.”

“I understand, sir. What would you like to do?”

“It’s bad enough I think we should take the gun down for the night. Check it out in the morning.”

“To be clear, sir, at your direction I am taking Gun 2 out of service for the night.” I did not want any doubts about who made the decision.

“Good, I think it’s best.” He sounded relieved.

At first light I hunted up Swede. “Tube ring?”

“Sure,” he said, producing from his pocket a small brass hammer used in making adjustments to the howitzer aiming and control mechanisms. He walked over to the tube, placed his ear to the surface, and gave it a ping. He held the hammer delicately between his thumb and forefinger. In his enormous fingers it looked like a toy.

I said, “And last night?”

“The lieutenant had his ear up against the tube for five minutes while I tapped away. I took him over to Gun 4 to listen, and then on over to Gun 5 so he could compare. I kept asking him: Can you hear it now, sir?”

“What was he supposed to hear beside you banging on the gun?”

“I don’t know, but before long he could hear it.”

“You know, Swede, I really took your gun out of service. Had to. You’re lucky we didn’t get a fire mission last night. Christenson thinks it’s hilarious but we have to clear the paperwork. I’m calling it maintenance.”

The word spread and with it an outbreak of tube ring disease. Two nights later it was Gun 4, and the next night Gun 5 fell victim to the epidemic. At morning formation First Sergeant Stollberg said, “Leave the lieutenant alone.” Everyone knew what he meant.

Once the lieutenant learned he had been made a fool, he came down hard on the gun crews. He called for useless maintenance. He made detailed inspections of equipment he did not understand. The crews grumbled but took it. The lieutenant then took his vengeance one step too far. He made every crewman wear hats and shirts during the day, an insult to their dignity and a public embarrassment, when cutoffs and tennis shoes were the accepted fashion statement.

Night had just fallen when inside the FDC bunker we heard an explosion, too small for an incoming mortar or outgoing howitzer fire.

Curly got on the landline connecting FDC to the guns and guard towers., “You guys know what that pop was?”

Curly had been the FDC section chief when I arrived. Despite having built a competent operation he had one less stripe than the new guy and got pushed down. He didn’t take it well at first and I handled him badly, but eventually we got to be friends.

The landline was on speaker. “Tower 2 here. It wasn’t incoming.”

“Gun 5. Don’t know, but someone saw a flash over by Gun 4.”

Curly raised his voice into the handset. “Gun 4. What are you guys doing over there?” There was silence and Curly yelled, “Gun 4, answer.”

An anonymous voice came over the landline, “Maybe Gun 4 is on R&R.”

“This is Gun 4. Top just got here.” The voice lowered. “And he is hoppin’ mad. It was a grenade. Somebody fragged the lieutenant’s hooch.”

Curly said, “Anybody hurt? We need a dust-off?”

“No.”

“Who did it?”

“Don’t know. Gotta go.”

At formation the next morning the First Sergeant was the angriest I had ever seen him. Top did not have the habit of using profanity, like some guys who couldn’t open their mouths without a dirty word. Top swore selectively, and this was one of those occasions. He delivered an old fashioned Army dress down. “Come to attention.” Normally we stood at-ease at formation. “You’re going to hear what I got to say. In case you don’t know, some piece of shit threw a grenade last night. It’s lucky nobody got hurt. Whoever did this could have hurt a lot of innocent people. Some poor fuck walking by all of a sudden’s got a face full of shrapnel. Whoever did this, I know I’m looking at you right now out there. I’ll tell you to your face, you are a fuckin’ coward. In the middle of the night popping a fragmentation in the middle of my firebase, my gun crews. I am going to find you, and I will have your balls, your dick and your ass in a meat grinder. Any of you get the idea this is cute or it’ll make you a hero—I will shoot you myself I catch the next guy that pulls this.” Top walked away leaving the formation at attention. He hadn’t said a word about the lieutenant.

The lieutenant was shaken but unharmed. The perpetrator was never found, and frankly nobody looked that hard, including Top. An uneasy quiet settled on the battery. The battery commander took the lieutenant off the guns, leaving him minimal responsibilities. The lieutenant spent his days drifting from place to place with a manufactured smile on his face, and avoiding the gun crews. He came into the FDC bunker every day and attached himself to Lt. Christenson. The two of them came to our little hooch parties at night, where Christenson was the comic center of attention and the lieutenant was happy to sit and be one of the guys. He turned out to be a decent fellow when he wasn’t in charge of anything. When he left the battery he departed a lonely and sad figure.

October 26, 2016

Ed Gaydos – Fire Direction Control – Part Three

The Dogs

In the beginning there were three. They had wandered into the firebase one by one looking for food and decided to stay: the way I imagine prehistoric wolves hung around human campfires and eventually turned themselves into dogs. Soon every howitzer platoon and section crew had its own dog, sometimes more than one. Wrinkles, matron of the FDC, did her part by having five puppies beneath Bob Christenson’s bunk in his back room. We kept one puppy and adopted the others out around the battery. Like dogs always do they went about with their masters and became voting members of the gang.

But dogs will be dogs. They started running in small packs. They established territories and fought over things that only made sense to a dog. One day I watched Wrinkles and her sister playing in the center of the compound. They belonged to different packs but were usually friendly with one another. Wrinkles found a crooked little stick, carried it near her sister and started tossing it in the air, as if to say, “Look what I got and you don’t.” Her sister now wanted that stick in the worst way and was willing to fight for it. The battle ended when Wrinkles got on top. With her fangs bared she forced her sister to a belly- up surrender. Afterwards both dogs wandered off, leaving the stick behind.

The dogs belonging to one of the guns, probably Gun 1, had a simmering feud going with the Maintenance dogs. The great showdown came when the two packs met outside the FDC bunker and became a tangle of bodies and snapping jaws. The guys from the gun and Maintenance came on the scene and took up sides. More people showed up and joined sides. The men and dogs made a single mob, filling the air with screams, growls and squeals of pain.

First Sergeant Stollberg had been unhappy with the dog situation for some time and this fight ripped it for him. At formation he said, “There’s too many dogs in the battery. It’s getting to the point where it’s not sanitary, with the shit piled everywhere and God knows what they’re pissing on. So here it is. Each unit gets one dog. That’s it. Guns, you get one dog for all of you, not five. Maintenance, FDC, Mess, Radar, Dusters and quad-50s each get one, that’s one for both quads and one for both Dusters. Pick the dogs you want to keep. The rest go tomorrow.”

There was no Humane Society in Vietnam, no doggie adoption agencies. Every unit did its own job. The dogs were coaxed into sandbags and carried squirming to holes outside the compound. M16 bursts went into the bags, making them jump and give off a squeal. When the bags went quiet the dirt went in over them.

Mike Leino somehow saved Wrinkles.

Best pals Mike Leino and Wrinkles

Best pals Mike Leino and Wrinkles

Love Him Or Hate Him

I mentioned in the beginning that Top and I did not get along. He was a screamer, at times almost out of control. I remember especially the time he came striding into FDC looking for me and very mad. Red faced and his eyes rimmed in red, he screamed a foot from my face because I had failed to send in a grocery order for the mess sergeant. There’s a whole story behind why, but not important. He dressed me down in front of my crew, made me say “Yes, First Sergeant” a few times, and stomped out. The embarrassment was one thing; worse was I never knew which Top was going to show up. Because his moods were so unpredictable I worked at staying out of his way.

Even in his crazy periods Top never made a bad decision the whole time we were together. And he always looked out for his guys, never himself. As much as I disliked the man, there were moments I loved the guy. One such time came quite by surprise during monsoon season.

God’s Shower Room

July brought the monsoon season in earnest to the Central Highlands. Most evenings at four o’clock sharp, thick clouds rolled down from the mountains and brought with them torrential rains. Walls of water turned the ground to soup, and when the sun set a dark descended so profound that a hand held out disappeared, dissolved by the night. The veterans went about with their eyes open but blind, navigating by the picture in their heads. New guys relied on flashlights, good for only a few feet in the downpour. With the rising sun the clouds moved back to the mountains, leaving the daylight hours clear and sunny. They hung purple and sullen on the mountain tops, and always seemed to me like they were waiting to attack.

The countryside erupted in lush, violent greenery. The warm daytime air sucked up moisture and made our valley into a great, sweltering sauna. The well filled high with clear water. Puddles the size of small lakes filled the compound. Guys floated in them on air mattresses and wrestled shin deep in the water. Everywhere wet clothing dried on the concertina wire, looking like a great outdoor laundry. A new trash pit we had just dug, but had not started to use, filled to the top with muddy water. It became a readymade swimming pool, and a jeep backed to the edge became a diving platform.

The Trash Pit Flip – Difficulty 6

The Trash Pit Flip – Difficulty 6

In the evening when the sun had almost set the clouds would roll down from the mountains and dump another flood on us. One evening while things were still barely visible I saw the First Sergeant strolling naked in the rain. His medicine ball stomach was leading the way, a bar of soap hung on a rope around his neck, and he was singing.

Words For Posterity

There was an incident that revealed Top’s true character, which I could admit only years later when I grew into some perspective on the man. It’s one of my favorite memories.

I was in the mess hall and the First Sergeant was at the next table. Outside two boys started wailing on each other in the center of the battery. They were crewmen on different guns, now settling an argument that had been festering for weeks. Their scrawny arms flew at one another like windmills, and a crowd was forming.

Top exploded from his chair and charged out the door, me right behind him. He marched with long, determined strides. His face was already scarlet, which meant trouble for anyone in its kill zone. He parted the spectators with a single breaststroke, and grabbed each combatant by an arm; they looked like chicken wings in his meaty fists.

Top pulled the kids apart. He paused for the crowd to quiet. Loud enough for everybody to hear First Sergeant Stollberg, career warrior, proclaimed in the middle of a combat zone, “Don’t you boys know that violence never solves anything?”

October 19, 2016

Ed Gaydos – Fire Direction Control – Part Two

The Demo

It seemed like some guys, a lot of guys come to think of it, made a kind of hobby out of gonorrhea. It wasn’t that hard to do. On a trip to Phan Thiet I was walking down a side street with a guy from Sherry. Vendors waved us over and mama-sans pulled at our sleeves, “Come see top notch girl.” My companion followed the mama-san, but first took off his wedding ring and said, “I always take the ring off. Then it don’t mean nothin’.”

Five days after convoys to Phan Thiet—I could count them—soldiers lined up outside First Sergeant Stollberg’s hooch begging for a medical pass. They held their crotches while Top yelled at them. Then at formation the next morning he yelled at everybody. His tirades were aimed squarely at an audience of teenagers away from home for the first time, full of empty threats and crude references to male anatomy, which always got their attention. “You come back with the clap, you’ll never see the rear again the rest of your goddamn tour. Tell you what, I’m going to start giving Article 15s for damaging Army property. Your dick belongs to Uncle Sam, you hear me? You can play with it all you want, but you bring it back dripping, I’ll have your ass.”

Top invited the battalion surgeon out to give us a talk on the ravages of venereal disease in Vietnam. The doctor said that one strain had no cure. Top interrupted him with, “In other words, you go to Japan and wait for your dick to rot off.” But the gonorrhea kept on, taking heavy casualties after every convoy.

Formation on this day was next to Gun 2. We fell in at ease while Top stood with his hands behind his back. We knew something important was coming when Top skipped the section chief reports. He got straight to the point. “Every time one of you goes to Phan Thiet you come back with a sore dick. So I give you a pass to get a shot in your ass. In a month you come back holding it in your hand again and crying for another pass. Well I’m sick of it. Goddamn fucking sick of it. So I’m going to help you out.”

Top reached into his pocket with his left hand and pulled out something small and square. “A lot of you have never seen one of these. It’s called a condom. When I was a kid we called ‘em rubbers.” He smiled, but in a wicked sort of way. “And for you momma’s boys who don’t know how to use one, I’m gonna show you right now. Pay attention.”

Top pulled his right hand from behind his back and held up a broom. He held it in the middle of the handle. “This is you.” Guys elbowed each other and pointed to the broom handle. Top thought a moment, “Well maybe this ain’t exactly you.” He slid his hand up to near the end. “Is that more like it?” Everyone looked at somebody else. More elbowing, some laughing, a dangerous thing to do in one of Top’s formations, but he let it go.

Top slipped the broom under his armpit, and went to open the condom. He struggled with it, ignoring the free advice coming from the formation. Finally he bit the corner and got the slippery thing out in the open. He then sent it into battle. He showed the tactical positioning on the tip of the broom handle. He demonstrated the maneuver of unrolling it. When he came to the last step he said, “You can’t pull this thing on like a sock. You got to leave some room at the end.” He snapped the little empty hat at the end of the condom. Everybody laughed and guys started punching each other on the shoulder.

Top ended the formation with a promise. “I got a whole case of these in my hooch. You come in and get a handful before going to the rear. They’re free. No excuses. You come back with the clap, I’m not shittin’ I’ll cut the goddamn thing off.”

…………………………

Not long after this I was at the latrine and could hardly stand for the burning. Oh boy, I thought. I was one of the old men in the battery, twenty-six years old, a section chief, overly serious about everything, and thinking back probably a little pompous. I dreaded what I had to do next.

I went to Top’s hooch and told him I needed to get to the hospital. “I don’t know how this happened, Top. Honest to God I never put my toe in the water.”

He looked at me, “It’s not your toe we’re talking about,” and held out a handful of the little square packets.

I went to the regimental hospital in Phan Rang. The medics took a culture, which in itself was a minor adventure, gave me a bag of pills, and told me to come back in two days. When I returned the technician gave me a thin smile, “You got a whole zoo growing in there.” He said it was nonspecific urethritis from highly unsanitary conditions. I thought: VD without the fun. Vietnam always had new ways to screw you.

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:12.0pt;

font-family:”Times New Roman”;

mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”;

mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;

mso-fareast-language:JA;}

I never tried to tell the First Sergeant about how I really got the clap. It would have felt like trying to explain how a virgin gets pregnant. But I made sure it never happened again. I started washing my hands before going to the latrine.

October 12, 2016

Ed Gaydos – Fire Direction Control – Part One

Introduction

These stories come from my two books on Vietnam: Seven in a Jeep: A Memoir of the Vietnam War and its sequel Surplus: The Long Arm of Vietnam.

How to pick the few incidents to include here? Reading through Seven in a Jeep three years after publication I was struck by how many times First Sergeant Stollberg comes on the scene. Top and I arrived at LZ Sherry at about the same time and left within a few weeks of each other, spanning ten months together on that little patch of sand.

Most of my contribution to this history of B Battery will be stories about Top, and in this way I will tell some of my story too. Top and I didn’t get along all that well. He was Old Army to the core, a veteran of three wars; while I was a kid with a thin skin a couple years out of the Catholic seminary, and recently pulled out of graduate school. Eventually we came to a distant respect for one another, and by the time we were ready to leave LZ Sherry I came to appreciate the man behind the bluster.

I wrote home most often to my mom, to my future wife Kathleen, and to my two younger sisters Jayne and Mary Kay. God bless them these beautiful women saved every letter. These stories sometimes include quotes from those letters, in-the-moment comments from my younger self. The dialog in these stories isn’t word-for-word perfect, but comes close, because some conversations you never forget.

Top

First Sergeant Stollberg

First Sergeant Stollberg

Picture courtesy Joe DeFrancisco

Make no mistake, First Sergeant Stollberg ran LZ Sherry. The officers played their parts, but the first sergeant pulled the strings. He had spent his adult life engaged in warfare: WWII, Korea and now a second tour in Vietnam. Top was old school artillery, and half deaf because earplugs were for pussies. He knew more about artillery than the rest of the battery combined, and had seen battles we only read about in school. Top’s combat career showed in his face. Up close it looked like tire tread. And he did not take guff from anybody.

Every morning Top called a formation. He held it at different locations around the battery, to keep the VC guessing. Placing soldiers in the same spot at the same time every day was asking for trouble. Top’s formations were quick and all business. He was keen on haircuts, upcoming inspections, work details, and the sorry state of the sad sacks under his command. Sometimes he pulled out a sheet of paper with a new policy from the Pentagon or battalion headquarters and read it word-for-word, not hiding his contempt for directives that had little to do with fighting the war.

Then there was keeping track of his boys, mostly teenagers, confined to a one-acre firebase like caged monkeys with guns. At the daily formation Top went down the rows for a report from each section chief. When he heard “All present” he looked up the rank and they had better be there.

Sometimes a section chief added, “…or accounted for.” Top would turn a red face in his direction, “So where the fuck are they? What are they doing that is so God-awful more important than my formation?”

Worst of all was, “One absent, First Sergeant.” This was shorthand for, I am missing a man and I have no idea where he is. Top’s eyes would turn to blue marbles, “You go find him right now.”

The more I got to know Top the less I liked him. He had a temper, charming one minute and shouting the next. I never knew what would set him off. From halfway across the battery I could tell what kind of a mood he was in by the shade of his face.

FO Fever

I wrote my first letter home under a flashlight three days after getting to Sherry.

May 5, 1970

I know you are all anxious to hear about LZ Sherry, the firing battery that will be my home for the next few months. Well, the food is good; much better than anything the Army ever served up in the states. But most of all I suppose you want to know how safe it is here. I’m not going to tell you it’s like being in my mother’s arms. It isn’t. We take sniper fire and of course mortar rounds every so often, just like every other firebase in Vietnam. And there is always the danger of the gooks getting thru our perimeter.

I work an “8 on – 8 off” shift around the clock, which means I spend most of my time working or sleeping. I’m still very skittery, especially at night when the VC does all its work. During our first mortar attack I just about wet my pants.

That was the night LZ Betty to our south was overrun and LZ Sherry was hit with two separate mortar attacks. The action at Sherry stopped a little after 3:00 a.m. We had no casualties that night, but LZ Betty was not so fortunate. In the morning we learned that she had taken heavy casualties, and that our forward observers there were badly hurt. An NVA infantry battalion of five companies in consort with five companies of VC, a force of about 350, had attacked LZ Betty. They killed seven U.S. soldiers and wounded thirty-five, leaving behind fourteen bodies of their own they could not carry off. That night 130 attacks occurred against firebases and installations in the region. LZ Betty was the only one to suffer a ground attack.

A forward observer team from LZ Sherry attached to 1st of the 50th Mechanized Infantry, Sergeant Pierce and radio operator Bill Wright, were at Betty when the attack occurred. Pierce took a round in the upper leg that made him fall over backwards onto Wright. The two sat back-to-back firing their weapons when Wright took two rounds, one in the back and the other in the upper leg. The last thing Wright remembers is being pulled out by a squad of the 1st/50th. When Wright woke up he was in Phan Rang and Pierce was in the next bed. (Taken from Bill Wright’s account of that night posted on the 1st Bn (Mech) 50th Infantry website: www.ichiban1.org/html/stories/story_3...)

We shot fire missions for the 1st/50th and they often bivouacked at Sherry for a day or two. I hung out with the forward observers because I loved the FO training at Ft. Sill and liked listening to stories from the field.

After only a few weeks at Sherry l had lost my jitters, grown bored and had forgotten that the FO team from Sherry had just been chewed up at LZ Betty. I wanted action and in a letter home I laid out my plan.

June 2, 1970

This FDC job is sure boring. I am thinking seriously of becoming a forward observer. Sitting between four walls for 12 hours a day and getting very little exercise is getting to me. I’d rather be out and about. We’ve got a FO here now from the field. Think I’ll talk to him in the morning. We have endless inspections, formations and “busy” projects. I’d rather have the war – seriously.

The drop in action did not last long. Fighting intensified with the beginning of monsoon season. Thick cloud cover and heavy rains reduced visibility at night to near zero and curtailed air operations, making monsoon a good time of year for the NVA and VC. They could pretty much waltz around at will. Despite a sharp increase in fighting, I still lusted for action.

July 2, 1970

Enemy activity has significantly increased with the beginning of July. This is their busy season you know. A couple VC battalions have been roaming around the area. We fired on one of them just 1000 meters off our perimeter last Sunday morning. Gunships also worked over the area. That went on all morning. Sunday morning is a favorite time with the VC. The Sunday before last I started my breakfast three times. I’d get two bites down when the siren would go off for another fire mission.

Many of the fire missions that come over our radios sound like clips from a television serial. Infantrymen taking AK-47 fire and mortars, or a chopper pilot adjusting artillery fire. Often it’s hard to believe that it’s all for real. You know I don’t even have normal dreams anymore. All I dream about are machine guns and sandbags and helicopters.

Last week we were alerted for a heli-borne operation. We were told we would be going to Bu Prang, which is on the tip of the Parrot’s Beak on the Cambodian border. But they have decided to send two guns from A Battery. I was looking forward to it; this place is so bloody boring.

Bored and stupidly dreaming of action

Bored and stupidly dreaming of action

I applied for FO school in early August, three months after arriving in Vietnam. Every forward observer, even graduates of Ft. Sill gunnery school, needed more training in Vietnam. After my first few minutes inside FDC and after listening to the FOs on the radio call in artillery with strange protocols and even stranger terminology, I understood why. This was not something you should learn on the job. I was approved to attend FO school in October and replace a guy leaving the next month. My heart beat a little faster at the thought of getting into the action.

Just before my departure Top pulled me aside. “The captain cancelled your FO school. He thinks you’re too valuable because you have formal FDC training. And there’d be a shortage if you left.”

I was crushed, thinking only of the endless tedium before me in this little firebase. “Top, what if I talked to him?”

“Won’t do any good. He made up his mind. That’s it.”

The POW

He was a child committing an act of war. We nabbed him in our concertina wire putting rubber bands around the trip flares. The VC and NVA often sent children to disable the flares before a ground attack. This made it easier for sappers to penetrate and blow holes in the wire, leading the way for NVA and VC regulars to come pouring through. We were already on edge from a special alert that had come down a few days before, and we were taking more than the usual amount of mortar fire. Days earlier a crew servicing the trip flares in the outer wire had discovered an anti-personnel mine. It was a homemade device: explosive material and four batteries in a plastic bag, with two bamboo sticks and wires for a detonator. It did not matter to a lot of guys that the enemy disabling our flares was a kid.

The soldier who caught the boy hauled him into the compound at rifle point. He looked to be around eight years old, just a whisper of a boy. His shoulder joints stuck up from his body in two knobs. He was dressed in a pair of shorts and Ho Chi Minh sandals, made with tire treads and strips of inner tube. He was crying. A crowd gathered and soon a heated discussion boiled up.

“He’s just a little kid, let him go.”

“Bullshit, these kids are soldiers. He’s a fuckin’ prisoner as far as I’m concerned.”

“He’s faking those tears, they train ‘em to do that, and I’ll bet he’s a lot older than he looks.”

“They don’t train these kids. They threaten their families or they pay them to do this shit.”

“He did this in broad daylight, right in front of us. He’s too stupid to be a soldier.”

“He’s a soldier if he’s working for the gooks.”

Voices rose to shouting. The boy knew no English, and we could manage only a few words of Vietnamese, none of them useful. We must have seemed like white giants to him, some with yellow hair that many Vietnamese had never seen and loved to touch when given the chance. The prisoner stood surrounded by these strangely colored behemoths as they bellowed at each other in their flat, guttural language.

In came Top; he was never far away. He listened without saying a word. With no explanation Top pulled his .45 and said, “I’m gonna shoot the little fucker right here and now.” He leveled the pistol at the boy’s chest.

The crowd fell silent. The boy stopped crying. There was a moment of stillness when the unthinkable was about to occur.

“NO,” we shouted together. One soldier stepped between Top and the boy. Then all was chaos and shouting again.

Top put away his pistol, and turning to leave said, “OK, girls, but get that little shit out of my battery.”

The boy stared with wide, unseeing eyes. His entire body began to shake. The soldiers who wanted him in a POW camp now petted his shoulder, rubbed his arms, crouched to look into his eyes saying soothing words to him. The kid started to cry again. Someone brought out a Hershey bar, maybe the greatest weapon of goodwill ever deployed by the U.S. military. The boy stopped crying and looked around. He took the candy bar and gave a smile that would melt the paint off a howitzer. That was all the encouragement we needed. Guys scurried off in search of more stuff. They piled the boy high with cartons of cigarettes, candy, C rations and a magazine or two. He staggered out the main gate hardly able to carry it all, but carrying a message from Top that needed no translation.

September 28, 2016

Bob Christenson – The Last Battery Commander – Part Five

The Last Battle: Getting Home

We had a saying:

I was back in Phan Rang in the Air Force BOQ (bachelor officers quarters), because they had air conditioning and real beds. The Army BOQ had cots and old mosquito netting. It was the day I was supposed to fly to Cam Rahn to get my plane to get out of there. Of course all of us from Sherry had bad thoughts about that flight to Cam Rahn Bay. (Seven month before George Beedy’s plane ran into a mountain on that flight.) I’m up at 6:00 in the morning, it’s just getting light. I go outside my BOQ room, which is like a cinderblock motel, and there’s a guy out there with a mama-san smoking a joint. He’s an Air Force guy. I say, “How are you?” And I say, “I’m leaving today.”

He says, “That’s great. That’s really cool.”

I say, “I’m going to Cam Rahn Bay.”

He says, “Wow! Great! I’m flying that plane.” And he’s out there smoking dope.

I say, “You’re flying that plane?”

He says, “Yeah, we’re taking off in a couple hours.”

I thought: OK, there’s your sign. When Beedy’s plane ran into the mountain on his way to Cam Ranh it really shook everybody up. I convoyed from Phan Rang all the way up to Cam Rahn. My adventures were over. I was not going to fly in that plane.

Six months prior on November 29, 1970, Sp4 George Beedy died on his way home, when his plane out of Phan Rang hit a mountain in heavy cloud cover. There were no survivors.

So I got to Cam Rahn and hung around there for a couple days. We were in big barracks. They would come in and read off a list of names and you’d get on the plane. After two days or so, Bammo, there we go. I was the second plane of the day. The first plane went up and ours was four hours later. We get on the plane. I took a bunch of sleeping pills someone had given me and I was so wired to get out of there they didn’t do anything at all.

The pilot came on and said, “Look, normally we would make a stop along the way, but we got plenty of fuel, a tail wind that is kicking butt, and we can go straight on through. What do you guys want to do?”

Well you can imagine. Everyone said, “GO, GO, GO.”

So we did a non-stop, which was great. We landed at Ft. Lewis and started taxiing to the gate when the pilot came on and said, “We got a little problem. The plane that left four hours before us stopped along the way and got here just before us. We’re gonna be here on the tarmac for ten or fifteen minutes while they process those guys.”

Everybody’s fine with that. This is a whole plane full of lieutenants and captains. Everybody’s cool. Some guys could see their wives and their kids out at the gate waving to them. Fifteen or twenty minutes go by and nothing happens. Half an hour goes by and nothing happens. There’s no air conditioning on the plane. Finally somebody says to the pilot, “What’s going on here?”

The pilot says, “Well they got to search these guys and their baggage and they don’t have the facilities to search you guys at the same time. So they have to do the other plane before we can go in there. But we’ll be out of here shortly.”

Two hours later we are still on the plane. It’s hotter ‘n hell of course. The people are starting to get restless. I think the pilots had left at that point, sensing trouble. There was a major who was the ranking guy on the plane. He said, “Let me see if I can at least open up the doors.” They opened up the doors, but we’re all still sitting there.

Remember, most of us on the plane were getting out of the friggin’ Army in one or two more days, and whatever happened they couldn’t send us back to Vietnam. People could see their wives, kids and parents just a few hundred feet away. Some of them hadn’t seen their families for a year. The mood on the plane got ugly.

We’re now sitting on the tarmac for three hours or more. They send people out to the airplane and tell us it’s going to be ten or fifteen more minutes. The place went into open rebellion. People started tearing seats out and throwing them out the door. The door was fifteen feet off the ground and people were wondering: Can we just jump? They can’t stop us. It was crazy.

That did it. Someone came up and said they would take us off the plane now. They ran us through and didn’t bother to check us carefully. In another half an hour that plane would have been toast. I never saw anything like it in my life. It was the last insult.

When I got to the commercial airport it was six or seven at night. I got a plane back to Chicago, which left maybe six hours later. It was a Boeing 747, and I had never been on a 747 before. It was like the coolest thing in the world. I’ll tell you what the pilot did. I’ll never forget this. He came down and met me as I got on the plane. He shook my hand and walked me up to the front of the plane. He said, “You’re flying first class.” I was the only person in first class. I sat down and went to sleep before we took off and woke up when we were landing in Chicago.

But Am I Really Home?

Captain DeFrancisco used to point out a snaggletooth tree you could see from our firebase on top of a distant ridgeline that we used as an aiming reference. He said, “When I was here before I used that same tree as an aiming point.” When I got back to the states that was my nightmare: being at Sherry for a year and coming home safe, and then one day being sent back and waking up back in the same hell-hole, looking up at that same tree. I would wake up at night and be mixed up about where I was. Am I here or am I there? I thought maybe I was still in Vietnam and my life since leaving there had been a dream.

Going to Vietnam you’re in the United States and after a twenty-four hour plane ride you’re in Vietnam. I remember that flight coming down the coast at night into Vietnam, looking down and seeing the illumination rounds in the air below us and the tracers and all the shit going on and thinking: What in the hell am I getting into? Then they literally dive the plane into the airport to avoid being shot at. That whole jarring reality change in just a few hours.

It was even worse going back, because now you are settled into the reality of Vietnam, but you’re suddenly back in the States with people walking around like nothing is happening, another sudden new reality. I would wake up in the middle of the night not sure if this was a dream or that was a dream, or where I was. You lose your sense of reality. Am I in Vietnam dreaming about home, or am I at home dreaming about Vietnam? The realities were so different and the edges so blurred that I just didn’t know. That lasted for a few years.

It’s not like we had the worst experience in the world. I can only imagine what the infantry guys went through. These days I think a lot about the guys who are sent on multiple combat tours to the Middle East. How can you keep your head on straight after going through that?

Fired In Anger

Like many veterans Bob was conflicted about his time in the Army, and at the same time is proud of his service. He has close at hand an ashtray made from a brass artillery canister, presented to him when he left Vietnam. The inscription reads:

To 1st Lieutenant Robert Christenson

12 July 1970 to 3 June 1971

From the Officers of the 5th Battalion 27th Field Artillery.

It originally had a 50 caliber bullet in the center, but they confiscated the slug at Ft. Lewis, so now it is just an empty casing. It’s a wonderful thing to have. All the officers got one of those. It was made out of a canister from a white phosphorous round. If you look on the bottom it says “1944.” We had all that ammunition, just like our C-rations, from WWII. We used a white phosphorous round because its canister was brass. All the other canisters were heavy cardboard or steel. We’d put a minimum time fuse on them and shoot them straight up for a nice airburst or just over the wire. There were few uses for WP rounds in Vietnam, except maybe to start fires. On the bottom of the ashtray it says Fired In Anger, but really it was fired in order to get an ashtray.

Two ashtrays in the making

Two ashtrays in the making

Picture by Steve Bell

Out of Vietnam Bob applied to Loyola Law School in Chicago, encouraged by a fellow officer at LZ Sherry. He had less than remarkable grades as an undergraduate, but gained affirmative action admission as a veteran. In class he sat with an intimidating group of other Vietnam vets. The professors and students gave them a lot of room, not knowing how crazy they might be and not wishing to find out. In a blind grading system, whereby the professors did not know the identities of the students they were grading, Bob graduated fifth in the class. He is now a successful labor attorney in Atlanta. He and his wife Kim have five kids and nine grandkids. Bob still flashes that mischievous smile he wore in Vietnam.

September 21, 2016

Bob Christenson – The Last Battery Commander – Part Four

The Chill Continues

After Captain DeFrancisco left I became the battery commander as a 1st lieutenant for a few months when they ran short of captains they trusted with command. Right away I had another run-in with the First Sergeant when I countermanded his order that the guys had to wear uniform tops in the mess hall. People complained about wearing shirts in the mess hall. I said to forget it, you don’t have to do that anymore, it’s crazy. Top got pissed and thought I was messing with his discipline, which I probably was. But I gained a little credibility with the men by doing that.

In general I let Top run the place and didn’t cross him. I said to him, “Look, it’s your firebase.” It was always his firebase anyway. “I know it. You know it.” That was my whole MO. I didn’t mess with anybody unless they needed messing with.

The Hardest Thing

There was a kid from Detroit whose name I can’t remember. He had been sent home on some kind of emergency leave because something awful had happened, his mother and father had been killed in a car wreck. It was pretty bad, but he came back and had been in the battery for a couple weeks. I was in FDC at the time with Barry Eckert on the radio, when another call came in telling us that this kid’s grandmother, sister and her baby had been killed in a house fire. I had them verify the information because it was so inconceivable that something else could happen like this. That afternoon I had to call the kid into my hooch and tell him what had happened. It was awful. They sent him home for good this time. Hardest thing I have ever had to do.

Not This Time

Just like at LZ Betty the year before, an order came down from Phan Rang to chain and lock up our M16s. They were concerned that there was going to be a rebellion at the firebase, that some officers would be shot. That was just insane. There wasn’t going to be a revolt at the firebase, and locking up our weapons in the middle of a war was the stupidest thing I ever heard, worse than the orders to keep the FADAC computer running. What idiots. We never implemented that order, which was one thing Top and I absolutely agreed upon. I told the rear that they could court martial me or throw me in jail, but I was not locking up our weapons, and they dropped it. They obviously had not learned from Betty.

In early May 1970, with all of its weapons locked away, including those of Delta Company of the 1/50th Infantry that had just returned from the field, LZ Betty had been overrun by a combined force of NVA and Viet Cong.

In firm possession of his M16

In firm possession of his M16

Lousy Shots – Thank Goodness

One day some papa-san was out gathering wood west of the battery in the off-limits zone. Maybe he was VC, but who knows? All the locals knew better than to hang out there, and the guy was around the creek wash that the VC used to sneak around in. So maybe he was up to no good. We fired a couple warning shots over his head but he didn’t pay any attention. Everybody wanted to shoot at the guy, and kept after me to let them go. I checked about five times with the ARVN clearance people because I really didn’t want to start blasting away at some farmer, but all they would say was: Go ahead and shoot. So I reluctantly let the Dusters on that side of the battery start shooting at the guy. There were about twenty people gathered around the duster. I think some of them were there to see this guy get blown away, and others because they couldn’t believe what was going to happen.

The Duster popped a few rounds out there that missed the guy pretty badly. Once he realized they were shooting at him he started to run, and the Duster guys opened up in earnest. There were rounds going off all around the guy. After about ten seconds of this, which seemed forever to me, I couldn’t take it anymore and jumped up on the Duster and told them to stop the hell shooting. The guy got away and in the end I think everyone was pretty relieved that they didn’t hit him. I know I was. The whole thing freaked me out. It would have been one thing if he had a gun or was obviously VC. But this wasn’t the case. Thank God the Duster guys were such bad shots.

No Medal For Mike

Mike Leino

Mike LeinoSomewhere along the line I put Mike Leino in for a medal for saving a guy’s life. Mike was a laid back guy, and probably could have cared less about a medal, but he deserved one. They were burning trash and whoever it was poured gasoline on the trash to ignite it, and when he lit it, the guy managed to turn himself into a human torch. Leino was the only guy out there and tackled him and put the fire out. The guy had third degree burns and was sent home. Mike saved his life.

I thought Mike’s effort was pretty outstanding, so I filled out the paperwork and went through headquarters back in Phan Rang to get something for him. A few weeks went by without any response, so I started sniffing around. Finally someone told me that the battalion commander had nixed it because burning trash with gas was against regulations, and if he had submitted my recommendation it would have been evidence that someone in his command wasn’t following protocol. So no medal recommendation ever got past headquarters.

I was pretty pissed about that, and after I got home to the states I sent a long letter to the editor of the Detroit Free Press, Mike’s home town newspaper, explaining that they had a real hero in their midst and why, and explaining why he had never been recognized. I never heard anything back, and a few months later found out that the paper was on strike and not publishing. I guess my letter got nowhere. The whole thing left a really bad taste in my mouth about the Army.

On Further Reflection

We all did some dumb things, and I certainly did my share. But my all-time dumbest move took place when a few of us took a LOACH (a light reconnaissance helicopter) out to reconnoiter a coordinate that intelligence told us was being used as an NVA staging area for an assault on Sherry. Huge mistake and I knew better and am very lucky to be alive after that one.

I was a couple weeks from going home at the time. We got word that the NVA was going to have our asses one night, much like the warning we had a few months before. The intelligence gave us a general staging area so the battalion LOACH came down and we took off to have a look. I think there were three or four of us, I don’t think the LOACH could carry more than that. The area was about three miles or so out to the northwest of the firebase.

We got there and didn’t see much of anything, until someone spotted what looked like a shirt hung up on a tree branch and flapping around. Somehow, incredibly, I got talked into allowing the helicopter to land to check it out. I’m still shaking my head over that decision, but we were young and invincible, right? We had a couple M16s and I had my .45 pistol. So we put down in a grassy area with pretty good visibility and had a look around. The pilot stayed in the LOACH and kept the rotors going. I had my .45 out and we walked around a little bit. We didn’t see anything suspicious. About a minute later I walked onto the top of a bunker that had been dug into the ground. It was built with concrete railroad ties and completely covered by grass that had been cut and laid over the top to hide the bunker. The grass was so fresh it was still green and not yet wilted in the heat. One of my boots went between the railroad ties and I started to fall into the bunker, and everything kind of flashed in front of my eyes. I thought how stupid I was seeing the fresh grass and knowing the NVA was in the area, and maybe this was the end for me. It sounds dramatic but I wasn’t really scared. I just thought: I’m going to take as many of the bastards with me as I can. Anyway, no shots from the bunker, and I caught myself on one of the ties before I dropped completely through. I yelled to the others to get the hell out of there.

We hit the chopper on the run and took off. On the way back to Sherry we took a reading on the direction of the bunker, and once back plotted on our grid chart where we had been. Later that night after it got dark and I felt like it was the right time, we shot a THREE ROUND BATTERY ZONE AND SWEEP on the target. At least I think that’s what we used to call it. Each of our six guns shot three rounds at three different but close deflections and three different but close quadrants, for a total of twenty-seven rounds per gun, or a hundred and sixty-two rounds in all. That way we covered a lot of ground quickly around the target. I think we probably shot VT (radar fuses resulting in fifty meter air bursts). We got what sounded like a couple secondary explosions.

A few days later the ARVNs swept the area. They reported back lots of body parts and some ridiculous estimate of twenty-five or more dead. The idea was that we had dropped our rounds on the VC/NVA by surprise while they were all out there exposed. Of course we never got out there to take a look ourselves, so who knows? Body counts were notoriously unreliable. It may be that nothing was there but craters, and the ARVNs just told the higher-ups what they wanted to hear. Or more likely, the ARVNs never went out at all and just reported as if they had. The NVA attack never came, but maybe it was never coming, like the other time we had been warned. But who knew? Clearly something was going on out there.

Anyway, I got religion when I was falling into that bunker. Someone had been there very shortly before we arrived. There were no more adventures or take-chances left in me. On my way home a few weeks later when I saw the pilot of my plane to Cam Rahn smoking dope with his momma-san, I convoyed.

The Last BC

Lt. Christenson left LZ Sherry in June of 1971, just days before the battery and its equipment transferred to the Army of the Republic of South Vietnam. On August 31, 1971 B Battery and the rest of the 5th Battalion were deactivated.

When I left Sherry there were rumors that we would be standing down, but that was about it. I had no idea that it would happen so fast. I never thought about being the last battery commander. I would rather that legacy be left to Captain DeFrancisco, who deserved a spot in the history books.