Captain Henry Parker – Battery Commander – Part Eight

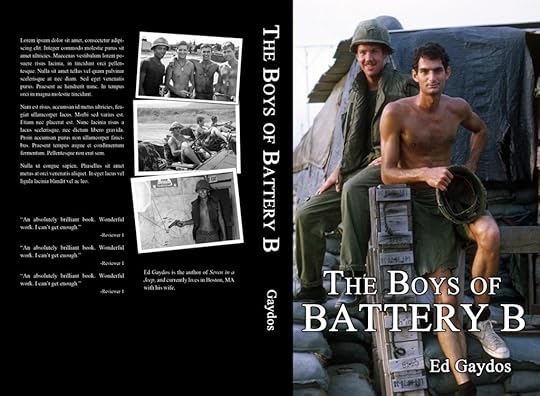

Publisher’s Front and Back Cover Design

Hank Parker

PART EIGHT

Recon By Fire

When infantry companies come in from the field to relax and rest, they always provide perimeter support for whatever firebase they are at. They do guard duty, and they man bunkers and towers, which generally is no big deal at a rear area like LZ Betty. There was no way they want to stand down at Sherry because they see us getting hit with mortar attacks so often. “Hell no,” I’ve heard them say, “it’s too dangerous.”

That’s why Durant and I start doing patrols around the battery. I tell Durant I know how to do this, I been out there on foot a lot. I take six to eight guys out – squad size – and do recon by fire. You shoot into the tree line and see if anybody shoots back. Primarily I’m looking for any locations on the surface from which mortars have been fired or telltale evidence of troop movements.

Andy Kach still talks about this crazy lieutenant taking artillery guys out on patrol.

It is effective because the enemy has to reconsider what they are doing, because we’d been out there, which forces them to do a reconnaissance to see if we put any mines there. For awhile it slows down the attacks. One time along the creek bed that runs on the west side of our perimeter we find where a mortar baseplate had been set. I get my grease pencil out and the map from when I was with the infantry and mark that spot. I come back in and I give the coordinates to Fire Direction Control with orders to shoot on that spot during the night. I think we damaged a few enemy crews that way because the mortars begin falling outside the wire, as if there are inexperienced guys out there.

Outpost Nora

We’ve got two guns on an airmobile operation at a miserable little outpost named Nora north of Titty Mountain. (Also known as Whiskey Mountain and home to a variety of observation posts, radio relay stations, search lights, and units of both infantry and engineers.) We are quite a ways out from Sherry. Nora is a rock pile, you can’t dig a hole there. The Vietnamese are all around us, food and everything else out on the ground making the sanitary conditions deplorable. The rats are the size of little dogs. We sleep under steel culverts. Tommy Mulvihill and some of the guys have air mattresses. I don’t know where in the hell they got them, but I know I don’t have one. I am on rocks. When we get a fire mission I pop up and hit my head on that metal culvert ceiling, knock myself silly.

Deluxe accommodations but still smiling

We get our SP packs (toiletries, cigarettes and candy given to soldiers in the field), and we hand out candy to all the kids. Whole families come.

Monahan and Parker handing out candy at Nora

I am there to replace Monahan, and when he goes back to the battery it becomes scary because all of a sudden I’m in charge of two guns. Scary because I cannot go to somebody else and say, “What do you think?” That proves not to be the case, because I can go to Sgt. Jimmy Johnson who is a veteran sergeant and in command of the two gun crews. A great guy. And I’ve got Tommy Mulvihill as crew chief on the gun outside my culvert, so I figure I’m in good shape after all.

On this particular night the maneuver elements are working and we’re shooting fire missions in support of the infantry, the 3/506 Currahees again and the 44th South Vietnamese Regiment. They are in quite a bit of contact with the enemy. There is a B 52 strike and, oh man, it shakes the ground and I would not want to be under that.

We are firing artillery for Lieutenant Alex Taubinger, who replaced me in the field as forward observer. He is on Titty Mountain calling in the mission. The fire is under a BATTERY 3 command (both guns firing three rounds in rapid succession without intervening commands). The first volley does not sound right and I come charging out of my hooch yelling, “CHECK FIRE, CHECK FIRE.” (the command to cease firing immediately) It is too late. The lanyard is already half pulled when Tommy and I have eye contact and BOOM, the round explodes right out of the barrel. It blows me off my feet as I watch the gun crew go down. Everybody is flattened on the ground. Then I get myself up and see, oh my God, the other gun is hit too. The tires are flat and the breech is locked with a round in it. I say not to open it because the round might go off. I see that Sergeant Johnson and Lloyd Handshumaker have been killed. Tony Bongi is wounded. Tommy is severely wounded. Leggett, a nice quiet guy, is wounded.

Bongi, Mulvihill, Leggett at Nora

Immediately I’m posting guys on the perimeter to make sure we’ve got security for the guns. We’re getting the wounded together along with the dead. A Vietnamese father comes with his little girl and he’s got an M16 pointed at me like he’s going to shoot me and he’s screaming in Vietnamese and I don’t understand him. I’m thinking, Can’t you see I’ve lost men here? I look him in the eyes and use the Vietnamese phrase I am so good at, “Dung lai, di di.” Stop, go away fast.

Half an hour earlier we had gotten mail. Jimmy Johnson gets a letter from home which he reads to me. His wife is pregnant. And she had received notification – he’s learning this for the first time – that he’s going to get an early out from Vietnam to go to Officer Candidate School. Thirty minutes later he’s dead.

After we get the dead and wounded Medevac’d out, it’s necessary to keep the men there who can function. If they can still pull a trigger and fight a battle, I keep them. I always feel bad keeping wounded with me, and I always ask, “Can you fight?” If he says yes he stays. Tony Bongi is one of those, and his wound isn’t a scratch. He has shrapnel in him.

The cruelty of war is you’re going to take casualties, people are going to die and get hurt. As the man in charge I bear the responsibility for that. I’m thinking, what in the hell did I do wrong here?

The following morning they send out an investigation team. I take the opportunity to send Tony and another fellow back on the helicopter that brought in the inspection team. The investigating officer walks out to the gun, looks at it, checks the elevation (vertical angle at which the tube is set), bore sights it and says, “Well this is obvious. You didn’t lay the guns right. It didn’t clear the sandbags.”

I say, “Jesus Christ, the tires are flat. What are you talking about?”

Then I am told it was faulty powder because of the way the rounds had been stored. I say, “No, the powder is in bags and they are not stored in the canister.” He doesn’t even know that there are seven powder bags per round, that’s how little he knows.

They are concerned with who are we going to blame. They’re going to pin it on me, when they should be thinking here’s an officer who has just been through a traumatic event with men killed and wounded. They open a formal Article 32 investigation on me (investigation prior to court martial). I know there was nothing wrong with that gun. It’s Tommy Mulvihill’s gun and that gun was laid right. The tube was at the right elevation and all other settings were right. We’d had some movement on the wire earlier and fired it without any problems.

It is devastating to know I am being investigated, but the war goes on and we’ve got to support the infantry. At that juncture the only weapon I have now is a Vietnamese 42 mm mortar, which we use even though it won’t reach over 2,000 yards (compared to the 7 mile range of the 105 mm howitzer).

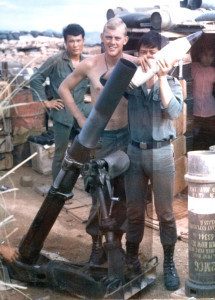

Vietnamese 42 mm mortar at Nora

The only remaining weapon

After the investigation we learn the cause of the mishap was a faulty fuse (the tip of the projectile controlling detonation), which Corps had known about. Instead of radioing the information to all affected units they were sending out paperwork via helicopter. The information had not yet reached us. I am cleared and happy to learn it was beyond my control. When the crews rotated I also rotated back to Sherry. The howitzers were repaired and stayed there at Nora.

………………………………..

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC has a web page where friends and loved ones can post messages and pictures. In 2009 I discovered a picture there of Sergeant Jimmy Johnson which his wife Linda had posted. I wrote her and told her that Sergeant Johnson was a hero in my eyes and that he routinely read her letters to me, including the one he received just minutes before he died. She called me, and we’ve been in touch ever since. His daughter’s name is Lisa and I periodically get an email from her as well.

Staff Sergeant James Johnson